FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN: TERRACOTTA GORGON MASKS IN A PHOENICIAN CONTEXT

Transcript of FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN: TERRACOTTA GORGON MASKS IN A PHOENICIAN CONTEXT

CIPOA 2 p. 289-299 © Maisonneuve, Paris, 2014

FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN: TERRACOTTA GORGON MASKS IN A PHOENICIAN

CONTEXT

S. Rebecca MARTIN1 Boston University, Department of the History of Art & Architecture

Abstract: Three fragmentary terracottas excavated from the southern Phoenician site of Tel Dor, Israel raise key questions about objects produced through cultural contact. Each bears the head of a Greek apotropaic figure, the Gorgon Medusa. These gorgoneia are typologically indebted to Greek roof tiles but did not function as such. Moreover, they cannot be understood to signal formal sanctuaries at Dor. A review of their form and comparanda is followed by a critique of foreign terminology used to describe their deposi-tion (favissa). The discussion considers what is now known about Phoenici-an artistic traditions, generally; cult masks in particular; and how the gorgo-neion type fits both.

Key words: mask, terracotta, antefix, gorgon, gorgoneion, Tel Dor, appro-priation, culture contact, favissa, bothros, cult.

INTRODUCTION

Three fragmentary terrracotas from the site of Tel Dor (nos. 1-3 below) have been interpreted as antefixes showing Greek gorgoneia2. These conclu-sions were drawn from stylistic similarities to gorgoneion antefixes found in

1 It is a pleasure to participate in a volume honoring JOSETTE ELAYI. Thanks are

owed to the volume organizer and editor, ANDRE LEMAIRE; to the director emeritus of the Tel Dor excavations, EPHRAIM STERN (Hebrew University Jerusalem Israel); and to present site directors AYELET GILBOA (University of Haifa) and ILAN SHARON (Hebrew University) for permission to discuss the gorgoneia. What follows is adapted from S.R. MARTIN, “Hellenization” and Southern Phoenicia: Reconsidering the Impact of Greece before Alexander, Ph.D. diss., U.C. Berkeley 2007. Related com-ments appear in J. NITSCHKE, S. REBECCA MARTIN, Y. SHALEV, “Dor: Between the Carmel and the Sea, Part II: Reconsidering the Persian-Roman Periods”, NEA 74, 2011, p.132-154, esp. 134-135, fig. 6a-b. Mask no. 1 was restored by R. ONI. All photographs are the author’s own and appear courtesy of the Tel Dor Project. Strati-graphy in Area D2 was completed by T. GOLDMAN, Y. SHALEV, and I. SHARON.

2 E. STERN, “A Gorgon’s Head and the Building of the First Greek Temples at Dor and along the Coast”, Qadmoniot 34, 2001, p. 44-88 (Hb); idem, “Gorgon Excavated at Dor”, BAR 28, 2002, p. 51-57; idem, Excavations at Dor: Figurines, Cult Objects and Amulets, 1980-2000 Seasons, Jerusalem 2010, p. 27-30, Fig. 32, Pl. 19.

S. REBECCA MARTIN

290

Nancy Winter’s critical study of Greek architectural terracottas. Two of them (nos. 1-2) were found in pits identified as sanctuary deposits (favissae)3. Accordingly the gorgoneia were understood to have decorated a Greek-style temple at the southern Phoenician site4.

The Dor gorgoneia raise key methodological questions about cultural con-tact and exchange in the Persian period. First, there is the matter of their interpretation, whether or not they are, indeed, Greek antefixes found in sanctuary deposits. Second, is the problem of inferring the meaning carried by modern terminology and ancient iconography when they move from one region to another.

THE MASKS

(1) Left brow, eye, cheek and tongue (fig. 1). No. 301375, L30049. Approx. max. dimensions (estimated without restorations): 0.18 x 0.115m. Thickness (estimated without restorations): up to 0.015m. Pale brown clay.

(2) Left eye (fig. 2). No. 170876, L17072. Max. dimensions: 0.09 x 0.08m. Thickness: up to 0.013m. Brown clay.

(3) Eye. No. 300800, Surface. Estimated max. dimensions: 0.090 x 0.070m5.

No. 1 shows a deeply wrinkled brow and bulging eyes; below, the mouth

bares teeth and large fangs that flank a projecting tongue. It is mold-made. The type is close to East Greek or Ionian gorgoneia, which, according to Nancy Winter (following the study of Janer Belson), are characterized particularly by fangs that flank the tongue6. Other features like the heavily wrinkled brow are not unique to the eastern type but are common to it. Petrographic analysis performed on no. 1 shows that its clay came from the Lebanese coast, namely, from the area between Tyre and Sidon, or from north of Tripoli7. So, the gorgoneion was made in the Phoenician mainland.

3 N. WINTER, Greek Architectural Terracottas from the Prehistoric to the End of

the Archaic Period, Oxford 1993. 4 A claim for an early example of a tiled, Greek-style temple was made at Tell

Sukas on similar grounds. See P.J. RIIS, Sukas I: The North-East Sanctuary and the First Settling of Greeks in Syria and Palestine, Copenhagen 1970.

5 No. 1: STERN 2010, op. cit. (n. 2), fig. 32:1, pl. 19. no. 2: idem, fig. 32:2, pl. 19. The author was not able to study no. 3 in person: idem, fig. 32:3, pl. 19.

6 J.D. BELSON, The Gorgoneion in Greek Architecture, Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College 1981.

7 STERN 2002, art. cit. (n. 2), p. 57, n. 7, after A. COHEN-WEINBERGER’s unpublis-hed report, Petrographic Results of Clay from an Architectural Tile from Tel Dor; pers. comm., COHEN-WEINBERGER, December 17, 2005; STERN 2010, op. cit. (n. 2), p. 32, n. 1.

FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN

291

A distinguishing feature of no. 1 is the continuation of the naso-labial fold well beyond the corners of the mouth. It has a nearly-complete parallel from the Heraion at Samos8. The Samian gorgoneion has thick curling hair popu-lated by snakes, the similar deep forehead furrows and long naso-labial fold, and an open mouth with fangs flanking the thick, projecting tongue. It is dated on style to the late sixth century. Its many snakes are characteristic of eastern types, and it is possible that no. 1 would have shared this feature, too. The East Greek type is known on the Greek mainland, also, as seen in two polychrome examples from an unknown building on the Athenian Akropo-lis9. They are dated to c. 520 on solid stylistic grounds: the treatment of their hair is similar to Akropolis Kore no. 673, and they bear a strong resemblance to a gorgoneion shield device on the Siphnian Treasury10. Both parallels place no. 1’s type in the last quarter of the sixth century and suggest that its current restorations should be rethought. The precise date of no. 1 is harder to fix; if the object is, in fact, as early as its parallels in the Greek world, it would be an extremely rare example of a sixth-century object from the site (reoccupation of Persian Dor seems to have begun only after ca. 500)11.

From what is preserved, the isolated left eye no. 2 is the same type. It, too, is mold made. Its well-preserved polychromy creates red skin and a vibrant blue brow; no paint remains on the eye that was probably white with a black iris12. No. 3, which was not available for hands-on study, appears too frag-mentary to assign to the left or right side of the face. Nonetheless, the wrin-kled forehead and prominent brow put it in the same typological neighbor-hood as nos. 1-2. The eye itself appears more round.

While the gorgoneia are derived typologically from antefixes, two facts – the lack of evidence of early tiled roofs at Dor and the form of the fragments themselves – suggest that they did not function as tiles. First, Dor has not produced any cover- or pan-tiles from the Persian period; tiles appear only in the Roman era. Without any plain tiles, we cannot presume the existence of an entirely tiled structure. The second point is that nos. 1-3 do not appear to

8 HS 80-23. A. OHNESORG, “Archaic Roof Tiles from the Heraion on Samos”, Hesperia 59, 1990, p. 181-192, esp. 189, pl. 21:b, e and f; WINTER, op. cit. (n. 3), p. 268, pl. 116; discussed in J. FLOREN, Studien zur Typologie des Gorgoneion, Münster 1977, type 1, p. 100-103.

9 Akropolis K292 78 and K293 79. WINTER, op. cit. (n. 3), “Attic Antefix IX,” p. 227-228, no. 14, pl. 96.

10 See A.F. STEWART, Greek Sculpture: An Exploration, New Haven 1990, fig. 152 (Akropolis Kore no. 673) and 193-194 (Siphnian Treasury).

11 Y. SHALEV - S. REBECCA MARTIN, “Crisis as Opportunity: Phoenician Urban Renewal after the Babylonians”, Trans, 41, 2011, p.81-100.

12 For example, a gorgoneion with preserved polychromy from the Athenian Agora (A2296) also dated according to its proximity to the Siphnian Treasury shield device by R. NICHOLIS, “Architectural Sculpture from the Athenian Agora”, Hesperia 39, 1970, p. 115-138.

S. REBECCA MARTIN

292

be antefixes: they are thin (their profiles do not exceed 0.02m in depth), their backs are concave, and, although admittedly fragmentary, none shows any trace of an attached tile (see fig. 1, right). In sum, the Dor gorgoneia are indebted to a gorgon type best known from East Greek architectural terracot-tas but could not have functioned in the same way. They are more closely related in form to the well-known, if understudied and eclectic, terracotta Phoenician masks - a point to which we will return below.

FINDSPOTS, FAVISSAE, AND BOTHROI

Most cultic objects are found in secondary contexts, in fills or pits of am-biguous purpose. Votives that appear in deliberate concentration may, how-ever, have special significance. In the Levant, ritual burial of objects is known from the seventh millennium; this practice precedes the existence of (archaeologically recoverable) sanctuaries. By the Persian period, it is typical for these deposits to be designated by one Latin term, namely, favissae13. No universal standard determines what kinds of deposits should be considered favissae, though they are broadly defined as pits or trenches filled with devotional objects (almost always including figurines) after they have gone out of use14. Though it cannot be discussed at length here, the term is clearly too broadly applied, obscuring the particular meaning of the word and lead-ing to the rushed identification of a variety of finds and deposits as favissae. Concentrations of cult objects alone do not establish the existence of formal, monumental sanctuaries. Nonetheless favissae have become the de facto means of identifying now-lost sanctuaries in southern Phoenicia15.

Occasionally one will see the use of the Greek term bothros, which is more neutral than favissa, meaning generally a hole, trench or pit dug in the ground16. When a bothros has a ritual sense in Greek literature, it is distinctly

13 Readers will occasionally see favissae compared to the Hebrew genizah (geni-

zot). 14 E. STERN, Material Culture of the Land of the Bible in the Persian Period, 538-

332 B.C., Warminster 1982, p. 158. In Latin literature, the term is rare (favisae or favissae; it does not appear in the singular). The majority of ancient references mention the favissae of the Capitolium in Rome. Favissae are mentioned in only a handful of texts, among them Varro (ap. Aulus Gellius 2, 10, where the word is called Etruscan). See TLL, s.v. “favis(s)ae”; Dictionnaire des antiquités grecques et ro-maines d’après les textes et les monuments, Vol. 2:2, Paris 1986, s.v. “favissae.” These sources suggest favissae were underground reservoirs or cellars located near a temple and containing water or re-deposited offerings.

15 E. STERN, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Volume II: The Assyrian, Baby-lonian, and Persian Periods, 732-332 BCE, New York 2001, passim.

16 Bothros appears in 39 texts (28 prose, eleven poetry). The term is used in an expressly ritualistic context in the Odyssey (in Books X and XI it is a trope to describe performing a ritual for the dead) and by Pausanias (where it is used to describe sacrificial pits: Guide to Greece V, 13.2; II, 12.1, 22.3; IX, 39.6). Non-ritualistic

FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN

293

the primary location for offerings, prayer and the performance of rites for chthonic deities. A deposit from Tel Akko’s Area F has been referred to as a bothros17. The Area F deposit offers an excellent example of ritual deposition independent of a sanctuary. It consisted of a stone-lined pit (L46) within a domestic complex18. Altogether, the deposit contained over fifteen “East Greek” and Cypriot vessels and probably at least a dozen Attic pots. Some of these were likely deposited whole into the pit, which is dated to the early fifth century according to its contents. The Area F deposit signals not only con-spicuous consumption but also ritual activity19. The many complete fine dining and serving wares alongside burnt animal bones indicate the vessels used in preparation and eating were deposited alongside the remnants of a special meal. There is no reason to assume, as has been argued, that the concentration of these “western” vessels (Greek, Cypriote, and “East Greek”) signals the ritual participants were Greek. Although not a Greek bothros per se, the deposit offers a rare look at ritual activity in the Persian period and highlights how even clear ritual sites - contrary to what is supposed by the term bothros and, elsewhere, favissa - may be sites of unofficial or unregu-lated activity (in this case, domestic).

At Dor cultic deposits have been identified in two main parts of the tell: two from the gates area (B and C), and three from the area overlooking the southern harbor (D2). Two of the Area D2 pits produced the gorgoneia nos. 1-2. They are:

Deposit A: Area D2, Square AK/13, L17072, 1995. Deposit B: Area D2, Square AO/12-13, L30049 (+ L30058 + L30075), 2000.

usage is common in both prose and poetry and can refer to various geologically-formed features (e.g., Strabo, Geography XII, 3.11) and fire-pits (XII, 2.7; cf. Hymnus Homericus ad Mercurium 4.94); man-made trenches for clothes-washing (Odyssey VI, 85) or, commonly, for planting trees (Xenophon, Apologia Socratis XIX, 13; Aristotle, Metaphysica V, 1025a); and is used to refer to graves, often horrible ones (Appian, Punica XIX, 129).

17 Access facilitated by the White-Levy funded publication project initiated by AVNER RABAN and EZRA MARCUS at the Recanati Institute of Maritime Studies, University of Haifa.

18 A. RABAN, “A Group of Imported ‘East Greek’ Pottery from Locus 46 at Area F on Tel Akko”, in M. HELZER - A. SEGAL - D. KAUFMAN (ed.), Studies in the Archaeo-logy and History of Israel in Honour of Moshe Dothan, Haifa 1993, p. 73-98 (Hb); M. DOTHAN, “An Attic Red-Figured Bell-Krater from Tel ‘Akko”, IEJ 29, 1993, p. 148-151.

19 Here I follow the definition set out by N.C. VELLA, “Defining Phoenician Reli-gious Space”, ANES 37, 2000, p. 27-55.

S. REBECCA MARTIN

294

Deposit A is comprised of single locus and is little-studied. It contained some charcoal, bones, flint, and glass and iron slag. Its primary find is the left eye of a painted demonic mask, no. 2. Three joining fragments of a faience amulet showing Thoth were found while cleaning the adjacent baulk. The Thoth type is well-represented among the imported amulets at Persian Dor20. The five main baskets of local pottery are Persian21.

Deposit B is a large pit nearly 0.70m deep found in a domestic area. Strat-igraphic analysis assigns Deposit B early in the Persian sequence in Area D2 (probably phase D2/5b); the phase dates to the first half of the fifth century 22. In addition to the fragments of gorgoneion no. 1, Deposit B contained local-ly-produced and imported Persian and Iron Age pottery; bronze (nails, scraps and slag); iron (nail and slag); a clay waster; and various organic remains (shell, bone, charcoal and flint)23. Preliminary analysis suggests the local pottery in Deposit B is Iron II-Persian with a preponderance of the former. Types include one Persian? kernos, a complete Iron II bowl, and Iron II cooking pots.24

While the Iron Age pottery might be expected from a Persian pit cutting earlier levels, the appearance of a complete Iron II bowl suggests other scenarios, among them the possibility that the pit was left open for an ex-tended period of time or that the bowl was an heirloom (no. 1 may be, too, if it dates to the last quarter of the sixth century, a time when the site appears to have been abandoned). The coincidence of fairly well-preserved mask (no. 1), kernos and complete bowl suggests that the pit was not for trash but for the intentional deposition of important items: the first two are explicitly cultic. The bowl and kernos are vessels used for liquid offerings appropriate for a chthonic deity, which raises the possibility that Deposit B was used for cult activities akin to the ritual bothros in the Greek world. Deposit A, on the other hand, lacks enough evidence to suggest it was a primary site of ritual activity; the highly fragmentary no. 1 and Thoth amulet may be discards.

20 No. 171644. C. HERRMANN, Ägyptische Amulette aus Palästina/Israel, mit ei-

nem Ausblick auf ihre Rezeption durch das Alte Testament, Göttingen 1994, no. 49; idem in STERN 2010, op. cit. (n. 2), p. 229, no. 7, pl. 2.

21 Nos. 170961, 170963, 170835, 170847 and 170837; STERN 2002, art. cit. (n. 2). 22 SHALEV - MARTIN, art. cit. (n. 11). 23 Bronze: nos. 301255, 301406, 301159; iron: nos. 301533 and 301458; clay: no.

301458. 24 From L30049: kernos: no. 301412, bowl: no. 301162; Iron Age lamp: no.

301160; black-on-red: no. 301559; Attic and “East Greek” pottery: no. 301259 (possibly Hellenistic?), L30058 and no. 301156, L30049.

FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN

295

PHOENICIAN MASKS

There remains the issue of how to address the particular function and meaning of the Dor gorgoneia. Clearly the gorgoneia encapsulate Phoenician artistic eclecticism: their demonic subject stems from Near Eastern traditions, their form is a Hellenic reinterpretation of those same traditions, and their production center was local. They also embody the Phoenicians’ related ability to select, rework and appropriate, which is particularly evident when it comes to Egyptian art (such as faience amulets). Take the case of the sar-cophagi of the Sidonian kings Tabnit and Eshmunazar II. These were appar-ently looted whole-sale from Egypt despite a long tradition of trade in Egyp-tian goods and appropriation of Egyptian iconography. They may be the progenitors of Phoenician anthropoid sarcophagi that hold to the basic Egyptian form, and initially to its iconography, but are made increasingly in a quasi-Greek style that is often, but controversially, assigned to Greek work-shops25. Keeping these tendencies of Phoenician art in mind, it is entirely plausible Greek architectural terracottas were remade into Phoenician cult masks.

Masks are found throughout the Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age onwards26. In the Iron Age-Persian periods they are found in a variety of contexts. In southern Phoenicia, portrait and animal masks from the ninth-sixth centuries are known from graves at Achziv27. To the south, a massive fill at Tell es-Safi produced hundreds of fragments assignable to over forty masks28. Terracotta masks of the coastal plain include a variety of types.

25 For Tabnit, see the summary by M.-L. BUHL, “L’origine des sarcophages an-

thropoïdes phéniciens en pierre”, in Atti de I Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici: Roma, 5-19 Novembre 1979, I, Rome 1983, p. 199-202. On the anthropoid sarcophagi, see the extensive survey by K. LEMBKE, Phönizische anthropoide Sarko-phage, Mainz 2001. Pro-Greek arguments are summarized by A. HERMARY, “Sta-tuettes, sarcophages et stèles décorées”, in V. KARAGEORGHIS - O. PICARD - C. TYTGAT (ed.), La nécropole d’Amathonte. Tombes 113-116, Nicosia 1987, p. 55-75. ELAYI has been a long, outspoken supporter of Phoenician manufacture; see, for example, eadem, Sidon, cité autonome de l’Empire perse, Paris 1989.

26 See the summary in M. DAYAGI-MENDELS, The Akhziv Cemeteries: The Ben-Dor Excavations. Jerusalem 2002, p. 159-160.

27 DAYAGI-MENDELS, op. cit. (n. 27), chapter 3, no. 28, and especially p. 156-160, nos. 2-24, fig. 7.20-23. A close parallel to the bull mask was excavated by E. MAZAR, “Phoenician Ashlar-Built Iron Age Tombs at Achzib”, Qadmoniot 27, 1994, p. 29-33 (Hb), esp. 33. See also eadem, The Achziv Burials: A Test-Case for Phoenician-Punic Burial Customs, Ph.D. diss., Hebrew University Jerusalem Israel 1996.

28 F.J. BLISS’s basic typology was produced well before much systematic analysis had been conducted on these “masks” (though he made several good points). The Safi fill is hopelessly mixed, but many of its finds are clearly from the Persian period: idem, “First Report of the Excavations at Tell-es-Safi”, PEQ 1899, p. 183-199, esp. 197-199; idem, “Second Report on the Excavations at Tell es-Safi”, PEQ 1899, p.

S. REBECCA MARTIN

296

Conventionally they are divided into two classes, the “normal” and the “grotesque”29. The latter group includes demons identified as Humbaba, Bes and similar characters; old males; or zoomorphic hybrids like satyrs. Alt-hough the grotesques draw broadly on Egyptian and Mesopotamian types; for the most part they do not adhere strictly to either iconographic tradition. Many seem to be examples of significant Phoenician reinterpretation of foreign types30. Most females are of the normal class and appear on protomai, which are not masks per se but may belong conceptually to this group.

Support for the importance and eclecticism of demonic types may be seen in the Peloponnese at the sanctuary of Ortheia (Sparta), a site famous for its sixth-century cultic masks and clear connections to the Near East31. The reliance on eastern prototypes for the masks is striking: what excavators call the “Old Woman” and “grotesque” types are just two of many characters that recall the lined face and bared teeth of Humbaba and other eastern demonic figures. Jane B. Carter has argued that the polarized characters represented by the Ortheia masks signaled the protector (grotesques) and consort (idealized male heroes) of the goddess, whom she associated with Asherah or Tanit32. Although the idea cannot be explored here, there remains the intriguing topic of divine pairs and representation in Phoenician religion. Tanit is of particu-lar interest. Perhaps her epithet PN B’L, “Pane Ba’al”33, literally “face of Ba’al”34, will play a role in understanding one function of masks. In any case, 317-333, esp. 327-329; F.J. BLISS - R.A. MACALISTER, Excavations in Palestine during the Years 1898-1900, London 1902.

29 The classic study was conducted at Carthage by P. CINTAS, Amulettes Puniques, Tunis 1946. Major contributions to the conventional approach can be found in W. CULICAN, “Some Phoenician Masks and Other Terracottas”, Berytus 24, 1976, p. 47-88; and E. STERN, “Phoenician Masks and Pendants”, PEQ 108, 1976, p. 109-118; STERN, op. cit. (n. 14).

30 As has been proposed by W. CULICAN, “Phoenician Demons”, JNES 35, 1976, p. 21-24 contra CINTAS, op. cit. (n. 29), who viewed most Carthaginian masks as derivative of Bes or Punic types.

31 R.M. DAWKINS (ed.), The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta: Excavated and Described by Members of the British School at Athens 1906-1910, London 1929. The eighth-century Heraion at Tiryns has produced several masks (including gorgoneia) that parallel those from southern Phoenicia. See A.H. FRICKENHAUS, Die Hera von Tiryns: Die ‘geometrische’ Nekropole, Mainz 1976. On the masks’ debated function, see I. NIELSEN, Cultic Theaters and Ritual Drama: A Study in Regional Development and Religious Interchange between East and West in Antiquity, Aarhus 2002, p. 88-93. Cf. A.D. NAPIER, Foreign Bodies: Performance, Art, and Symbolic Anthropology, Berkeley 1992, especially chapter 2, “Masks and the Beginning of Greek Drama.”

32 J.B. CARTER, “The Masks of Ortheia”, AJA 91, 1987, p. 355-383. 33 See CIS 195 and passim. 34 This epithet is discussed frequently; a convenient summary can be found in M.

DOTHAN, “A Sign of Tanit from Tel ‘Akko”, IEJ 24, 1974, p. 44-49. See also Y. Meshorer, City Coins of Eretz-Israel and the Decapolis in the Roman Period, Jerusa-lem 1985, nos. 47-50. Tanit iconography is discussed in some detail by S. BROWN,

FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN

297

both the conventional approach to Phoenician masks and Carter’s valuable Ortheia study demonstrate an important truism about exchange and develop-ment of types in the eastern Mediterranean. The gorgoneia fit neatly into a long pre-existing tradition of demonic characters. Moreover, their iconogra-phy is derived from Near- and Middle-Eastern predecessors that were famil-iar to Phoenicians. As such, we cannot know how a Phoenician would cultur-ally judge a gorgoneion – particularly when we remember it was made in the Phoenician heartland. It’s plausible that nos. 1-3 were understood as still more Phoenician character types, suggesting Greek iconography could be completely recontextualized in terms of local cult and artistic practices.

Dor has produced over sixty fragments of masks made in a variety of clays, scales and forms, most of which were found in pits or fills. There is only one complete example, which is also the smallest known mask from Dor (0.09 x 0.07m). It shows a smiling face35. Its mold-made, rounded features protrude from a circular frame, depicting a male especially if we see a cap or helmet on the head. The back is concave and has one, off-center hole through its under 0.01m depth. Demonic figures are known here, too. One may show a schematic Humbaba36. The Humbaba is heavier and larger than the small smiling male, with just a portion of its forehead measuring over 0.10 x 0.11m and 0.014m deep. There are two large holes in the wrinkled forehead flank-ing a motif of a branched “tree” that is a stylized version of fairly common motif on the center-forehead of Phoenician demonic figures.37 A set of bared teeth from a third mask suggests another stylized Humbaba type38.

How Phoenician masks and protomai were used and who or what they represented are difficult questions to answer39. Indeed, masks themselves raise many interesting questions (introduced above) about the little-understood particulars of Phoenician ritual practice and the connection between ritual, cult objects and representation of the divine. The one, or more Late Carthaginian Child Sacrifice and Sacrificial Monuments in their Mediterranean Context, Sheffield 1991.

35 Reddish-yellow clay with light inclusions. IAA #: 98-2291, no. 182438, L18225. STERN 2010, op. cit. (n. 2), no. 8, fig. 29, pl. 17.

36 Brown clay with a red core and dark inclusions. IAA #: 98-2292, no. 108681, L10945. STERN 2010, op. cit. (n. 2), no. 4, Fig. 29, Pl. 17.

37 E.g., a blue frit amulet from Achziv where a similar motif indicates horns. See CULICAN, art. cit. (n. 30), fig. 1: g.

38 IAA# 98-2296, no. 129430, L12916. MARTIN, op. cit. (n. 1), MA-5, fig. v.29. 39 See DAWKINS, op. cit. (n. 32), esp. 174-175 (Ortheia); Y. YADIN, “Symbols of

Deities at Zinjirli, Carthage and Hazor”, in J.A. SANDERS (ed.), Essays in Honor of Nelson Glueck: Near Eastern Archaeology in the Twentieth Century, Garden City 1970, p. 199-231 (Tanit); CULICAN, art. cit. (n. 30); E. STERN, art. cit. (n. 30); W. BURKERT, Greek Religion, Cambridge MA 1985, p. 103-105 (Greece); CARTER, art. cit. (n. 33; Ortheia); G.E. MARKOE, “The Emergence of Phoenician Art”, BASOR 279, 1990, p. 13-26; G. LEICK, A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology, London 1991, p. 110 (demonic masks); I. NIELSEN, op. cit. (n. 31).

S. REBECCA MARTIN

298

typically two, holes at the top of many masks indicate they were suspended. Masks could have been hung in private homes or perhaps were used in more specific ritual contexts analogous to representations of Dionysos as a mask on top of a draped pole40.

As god of wine and theater, both of which involve “masks” (satirical, drunken, theatrical), the literal representation of Dionysos through a mask is logical. But, as the Dor masks show, there is great variety to the Phoenician types, suggesting a variety of represented deities (if the masks do, indeed, represent the divine). Only some masks are pierced in the eyes, nose or mouth. Masks like the smiling male are solid and small; they could not have been worn by adults, children, or even infants. These variations cast doubt on the suggestion that masks are meant to represent in durable terracotta those made for wear in more practical and ephemeral materials41. Even masks rendered in human scale and pierced in the eyes and nose could be too heavy and unwieldy for wear. So, although a few Phoenician terracotta masks could have been worn during ritual activity, or could be reinterpreting those worn during rituals, we should not assume these functions explain the whole class. In other words, few (if any) terracotta masks had transformative properties for humans similar to dramatic masks. They must have served other purpos-es, one of which might have been to signify divine presence42.

CONCLUSION

In the mixed cultural milieu of the eastern Mediterranean, we are some-times compelled to make blunt decisions about complex objects. The identi-fication of artistic types places emphasis on source material sometimes at the expense of the specific context where a particular object was used. A fuller understanding of objects produced by culture contact comes from moving beyond classification to the consideration of the “receiving end” of the exchange, however challenging or frustrating the exercise. The gorgon’s Greek origins do not mean that the Dor masks are fundamentally Hellenic. It is even possible that the makers and users of these gorgon masks were indifferent to or ignorant of their sources.

40 As seen on the so-called “Lenaia Vases”: BURKERT, op. cit. (n. 39), p. 166, 237-

242. 41 CARTER, art. cit. (n. 33). 42 Protomai have long been interpreted as divine images rather than portraits. So S.

MOSCATI, The World of the Phoenicians, New York 1968, p. 164.

FROM THE EAST TO GREECE AND BACK AGAIN

299

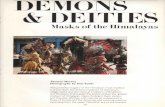

Fig. 1 Mask no. 1 from Deposit B showing a terracotta gorgoneion with extensive modern restorations, front and back, last quarter of the sixth

century BCE. Photo by author appears courtesy of the Tel Dor Project. Image not to scale.

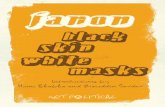

Fig 2 Mask no. 2 from Deposit A showing the polychrome left eye of a terracotta gorgoneion. Photo by author appears courtesy of the Tel Dor

Project. Image not to scale.