Foundation (Awqaf) Universities in Turkey-‐ Past, Present and Future

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Foundation (Awqaf) Universities in Turkey-‐ Past, Present and Future

1

Foundation (Awqaf) Universities in Turkey-‐ Past, Present and Future

Muammer Koç Istanbul ŞEHİR University, Turkey

Presented at the: 3rd International Conference on Islam and Higher Education (ICIHE 2012)

Kuantan, Malaysia; October 1-‐2, 2012

Abstract:

Role of Awqaf (foundations) in the higher education in Turkey has been on the rise,

particularly since 2005 after the re-‐arrangements made in the administration of Higher

Education Council (YOK) of Turkey. Number of universities established by foundations

increased to 60+ from 6+ in about seven years. In the same period, number of public

universities also almost doubled. In the near future, after the long-‐sought liberalization

and structural changes in the higher education laws of Turkey, further increases in role

of foundation universities is expected on the education and preparation of the next

generation of citizens and workforce. In this talk, after presenting the past and present

facts about the foundation universities in Turkey, a comparative analysis of their

establishment, administration and operations will be discussed in the light of awqaf

culture of our civilization. Although plenty in number, the current foundation

universities are not fully functional, hence, exerting their positive impact on the higher

education and preparation of the next generation partly due to heavy regulations and

restrictions imposed on them by law through the higher education council (YOK), but

also partly because of the fact that they are not (or cannot), in deed, designed,

established, endowed, and administered according to the real means and ways of awqaf

culture of the Islamic civilization developed through centuries, but lost in the 19th.

Long-‐sought changes in the higher education laws of Turkey are expected to liberalize

the higher education in general, role of foundations in particular, from the heavy hand

of government and undated restrictions. But, the real question is what will shape the

needed real awqaf understanding into modern, competitive and effective universities in

our lands?

2

1. Introduction

Number, role and impact of foundation (awqaf) universities in the higher education

system in Turkey have been increasing, particularly since 2007, after some limited re-‐

arrangements made in the administration of Higher Education Council (YOK) of Turkey

(YOK, 2012a). In this paper, after presenting the past and present facts about the higher

education and foundation universities in Turkey, a comparative analysis of their

establishment, administration and operations will be discussed in the light of awqaf

culture of our civilization. The current foundation universities are not fully functional,

and hence, do not fully exert their positive impact on the higher education and

preparation of the next generation, partly due to heavy regulations and restrictions

imposed on them by law through the higher education council (YOK), but also partly

because of the fact that they are not, in deed, designed, established, endowed, and

administered according to the real means and ways of awqaf culture of the Islamic

civilization developed through centuries, but degraded in the 19th century.

In the second section of this paper, a summary of education and higher education (HE)

in the past will be presented starting from the Nizamiyah Madrasahs of Seljuks in 10th

century until the establishment of Dar ul Fünun (House of Sciences) in Istanbul in late

1800s along with the role of awqaf. In the third section, changes in the higher education

system will be described during the early decades of the Turkish Republic (1923-‐1950)

in the light of reforms implemented almost in all aspects of life, governance, trade,

finance, military and education. After a brief summary of changes in the higher

education history between 1950 and late 1970s, major reforms made through

establishment of Higher Education Council (YOK) in 1981 will be presented until 2007,

during which some foundation universities were allowed to operate although still under

the regulations of YOK. Developments since 2007 will be analyzed in the final section

followed by a discussion of long-‐sought changes and reforms that are expected liberate

the higher education from tight regulatory controls, and permit establishment of

foundation institutes with more civic, independent, alternative but accountable

administrative approach.

3

2. History of higher education and role of awqaf

2.1. First organized madrasah system under Seljuks and early Ottoman period

(1000-‐1300s):

The first organized higher education institute(s) in the lands of current Turkey was

established in the 10th century by the Grand Vizier (Nizam ul Mulk) of Seljuks. They

have been known as Nizamiyah Madrasahs, and spread around the Seljuk lands

stretching from eastern Iran to middle Anatolia. Nizamiyah Madrasahs were founded in

more than 20 cities of Seljuks, each headed by a famous professor (mudarris) of its time.

Some of the known Nizamiyah Madrasahs and their head mudarris include the

followings: Nişapur Nizamiyeh (İmam Juweynî), Bağdad Nizamiyah (1067, Abu İshaq

Shirazi), Belh, Herat, İsfahan, Basra, Merv, Musul, Amul, Harcird, Rey, Buçenj. Although

some argue that these madrasahs cannot be counted as higher education institutes as

they offered education starting at early stages of childhood until late teens, they offered

the highest level of education anybody could get at their time, hence they should be

counted as higher education institutes.

Each Nizamiyah Madrasah was financially supported by one or more awqaf

(foundation), for which several aqar (income generators) was donated by the rich of

city (usually military and civil administrators of the time). Their existence and impact to

train civil and military cadres of the government continued into the early Ottoman era

(1300 – 1450s) (Ergun, 2012). As followed by the Ottomans eventually, each Nizamiyah

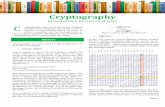

Madrasah was built around a Cami (mosque) in a city center (Figure 1). They had

various other facilities to accommodate practically all needs of students (talebe) and

professors (mudarris) as well as visitors, such as classrooms (dershane), student rooms,

health center (dârüşşifa), bath house (hamam), kitchen (imaret), guesthouse

(misafirhane/balahane), time monitoring and keeping house (muvakkıthane), primary

school (mekteb-‐i şerif), library (kutuphane), etc. Many shops, shopping centers, plazas,

hotels (in today’s terms) and large lands were donated to the waqf (foundation), which

supported the madrasah under a signed and honored thrust document (waqfiyyah) by

the ruler and judge of the time and region. In brief, it can be stated that Nizamiyah

Madrasahs and the madrasahs followed them in the Ottoman era were rearranged

versions of Prophet’s mosque and Suffah system in Madinah, where learning was

4

embedded into real life that facilitated immediate implementation of learnt knowledge

into action.

a)

b)

c)

Figure 1): Examples of madrasahs in today’s Turkey established by Seljuks following the Nizamiyah Madrasah example in various towns and cities: a) Karatay Madrasah in Konya, b) Twin Madrasah in Kayseri, c) Another madrasah in an Anatolian city with a different

layout (FelsefeEkibi, web, 2012)

5

2.2. Fatih kulliyah (Sahn ı Seman): Ottoman period between 1450 – 1600s:

In the early Ottoman era (1300-‐1450), Nizamiyah Madrasah system was continued

under the sponsorship of local leaders and government officials through foundations.

Different madrasahs in almost all towns and cities operated independently, only

interacting through transfers of professors and students among them for several

reasons.

After the conquest of Istanbul in 1453, Sultan Muhammed II (a.k.a. Fatih) established

the largest madrasah of its time in Istanbul (Fatih kulliyah or Sahn ı Seman) between

1462-‐1470 (Figure 2). Sahn ı Seman madrasahs provided the highest level of education

of its times until 1560s. It included sub-‐level madrasahs (Tetimme madrasah) to feed

students into its system. Its education included both Islamic, Social and Science subjects

offered by professors (mudarris) transferred from other regions and countries. Each

student, professor and helper was sponsored the awqaf founded by Sultan.

Figure 2): Fatih (Sahni Seman) Kulliyah as its stand today was founded by Sultan

Muhammad II following the conquest of Istanbul between 1462-‐1470.

6

With the establishment of Sahn Seman Madrasahs, all madrasahs in the country were

reorganized according to the level of education they provided, each madrasah in

different towns and cities fed students to the next level (Ergun, 2012). All education

starting from the early childhood schools (sibyan schools) was pretty much supported

by awqaf in every city and town. Students had to travel to other cities and towns to

obtain a higher level of education in some cases.

Awqaf was quite common and strong because of the administrative and economic

system of Ottomans. Accumulation of excessive wealth was almost impossible: the

largest difference between the wealthiest and poorest was not more than 5-‐7 times in

any line of business. Wealth was mainly in the hands of military and civil servants of

Sultan (administrators), and it could not be inherited. It had to be returned to the

government based on the assumed fact that the wealth was accumulated due to the

given duties and titles (Genc, 2007). Thus, wealth of numerous pashas, viziers, other

administrators and their family was simply transferred into awqaf, which in turn helped

building of the country: mosques, roads, kervansarays (hotels), fountains, schools,

madrasahs, hospitals, even bird houses.

In 1559, Sultan Suleyman (a.k.a. Kanuni, the law maker) founded Suleymaniya Mosque

and Kulliyah, which included Suleymaniya Madrasah. It comprised of six madrasahs

focusing on the highest level of education on Medicine, Math, Science, Religion (Dar ul

Hadith), Law and Literature. It also included mektep (elementary and middle school),

library, bathhouse, tabhane (exercise and health center), imaret (kitchen) ve dârüşşifa

(health center) (Ergun, 2012). Suleymaniya Kulliyah was supported by an awqaf

founded by Sultan Suleyman. Sahn Seman continued its service focusing on religious

subjects whereas Suleymaniyah focused on Social, Science, Medicine and Higher level of

religious topics (Dar ul hadith). All madrasahs in the country were rearranged

according to the level of education they offered, highest level was being at the

Suleymaniyah Madrasah.

Although it was the highest and best times of higher education with the establishment

of Suleymaniyah Kulliyah, the very first steps of corruption in the education system

were also noticed in this period. Merit-‐based selection and appointment of professors

7

was disregarded in few cases leading to “inherited” teaching positions and a class of

scholars (ilmiyye) in the society (Hocazadehs (sons of hojas), Fenarizadehs, etc.) (Ergun,

2012). Eventually, such irregularities and non-‐merit-‐based appointments led to

degradation of quality education and human capital in the country in the 17th, 18th, and

19th centuries.

2.3. Ottoman period between 1600 – 1920:

Corruptions and uncompetitive administrative practices resulted in a series of losses in

wars with mainly Russians and Western countries in 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Ottoman’s economical, administrative and military system did not function as expected

due to various compounded reasons, but stemming mainly from unprepared, badly

educated, uncompetitive human capital, (Tekeli, 2010; Hatipoglu, 2000; Genc, 2007).

In late 1700 and early 1800, few Ottoman sultans had the courage and vision of

reforming the administrative, economic, military and education systems. Simply,

however, these were too late, too weak. But, mainly to revamp the military power, few

educational reforms were initiated (all government supported) as follows (Ergun, 2012;

Tekeli, 2010; Hatipoglu, 2000): (a) 1730s-‐ School for Canonry (Humbarahane and

Tophane); (b) 1770s-‐ Engineering Schools for Military (Muhendishane i Bahr i

Humayun, Muhendishane i Berr i Humayun); (c) 1830s-‐ Military Academies (Erkan i

Harbiye ) & Medical School.

The first civil higher education institute was conceived in 1845 (Dar ul Funun), but it

did not live long. Darul Fununu Shahane was formed in 1900 at the time of Sultan

AbdulHamid after a series of trials and fails between 1850-‐1900 (Ergun, 2012; Tekeli,

2010; Hatipoglu, 2000). In fact, it was Sultan AbdulHamid who reformed the education

system and made sure that different levels of education was provided throughout the

empire: (a) Elementary schools (Iptidai Mektebs); (b) Middle Schools (Rushdyiah

Mektebs); (c) High Schools (Sultani); (d) Higher Education (Darul Fununu Shahane,

Vocational Schools, Military Schools, Schools for Girls, etc.)

In the late Ottoman times, there was a conflict between reforms in the education

systems and Awqaf-‐supported education institutes (madrasahs and sibyan

8

(elementary) schools. Madrasahs opposed to the reforms in the education system

mainly because it copied western style, but also because of the defiencies and

degradation in the madrasah system and its human element as mentioned before. The

old madrasah system was closely associated with awqaf, whereas the new education

system and Darulfunun were entirely financed, supported and controlled by the

government (Ergun, 2012; Tekeli, 2010; Hatipoglu, 2000). Although this resulted in

some improvements and help the reforms, eventually (particularly late Ottoman era and

entire Republic era) too much government involvement, hence political control, was not

to the benefit of the education system, universities, thus, to the people.

2.4. Early Republic Era (1920-‐1950):

Even though there was a new regime, new government and reforms in all aspects of life;

people was the same of the late Ottoman times. Hence, reforms were, in a way,

continuation of the recent past (i.e., Ittihad Terakki administration of late Ottoman

period). The Turkish Republic and its administrators were determined to erase

everything Ottoman in a secular revolutionist approach. The entire education system

(including higher education) got its share. The main revolution was the change in the

alphabet from Arabic letters to Latin letters overnight in 1928. The second was the

Tawhid i Tedrisat reform (Unification of Education), which ensured that there would be

a single kind of education, and that would be the one controlled by the government, not

foundations. Off course there had been some exclusions given to minority and western

financed schools. Third, all awqaf and their governing body (Awqaf and Shariyya

Ministry) were abolished. Madrasahs were closed, and property of awqaf was given to

the control of the government. Even today, no close account of how much awqaf

property and wealth was lost, given away, forgotten, demolished, etc. can not be

accomplished.

Istanbul University was established in 1933 replacing the Darulfunun. At least two-‐

thirds of the mudarris (professors) were dismissed; and more than 60 new professors

were transferred from Germany and Austria. Such transfers were facilitated indirectly

due to oppressive Nazi period, especially for the Jewish academicians (Ergun, 2012;

Tekeli, 2010; Hatipoglu, 2000; YOK, 2007). Later, a new university in the new capital was

established, Ankara University, mainly by German professors. Until 1950s, the higher

9

education followed the von Humboldt system of Germany, where a university

comprised of various institutes for both teaching and research, and each institute was

headed by a powerful professor appointed by government (Tekeli, 2010).

2.4. Intermittent Democratization Era of Republic (1950-‐1980s):

Few new universities were established by the first democratically elected government

in 1950s under different jurisdictions (e.g., Middle East Technical University-‐ METU).

METU and other new universities adopted the American model due to increasing

influence of the U.S. in the whole World after the World War II (YOK, 2007a). In deed,

many obtained direct U.S. financial and human support (METU, Ataturk University, KTU,

etc.) in later decades, (Tekeli, 2010; YOK, 2007a). Along consecutive decade-‐long cycles

of military coups and coalition governments between 1960 and 1980; higher education

was completely politicized between left and right streams of students, professors and

politicians (Tekeli, 2010). Due to the heavy influence of communism and leftist political

streams of 1968s, anarchy and unrest; universities were far away from educating the

next generation competitive workforce, scientist and administrators. Between 1960-‐

1971, there was a trial of private higher education institutes, which offered education in

few selected areas (Engineering, Architecture, Business, Economics). But, this trial was

ended by a Supreme Court decision in 1971 (YOK, 2007b). Until 1981, several

fragmented higher education models and institutes operated pretty much in chaos; but

none was Awqaf institute: (a) State universities, (b) Academies of engineering and

architecture, (c) Academies of business and economics, (d) One-‐of-‐kind universities that

had their own legislation (such as METU).

2.5. Era under Higher Education Council-‐ YOK (1980s-‐2007):

Following a military coup in 1980, the higher education system was reformed entirely

by a constitutional legislation in 1981. A higher education council (YÖK) was formed to

oversee, control and direct all higher education institutes in the country. All

universities and institutes were reorganized, some renamed, some split into two or

three; new ones were established. A heavy central administration approach was taken

so much that student quotas for all departments in every university or even hiring of

teaching assistants were centrally controlled (Hatipoglu, 2000; Tekeli, 2010).

10

The first head of the higher education council (YÖK) was a quite remarkable,

contraversial, and pragmatic person who left his fingerprints all over the current higher

education system since then. Because of his own ambitions, even under the military

rule, he was able to establish the first foundation university in the Republic era (Bilkent

University) in 1984. Off course, it was his own foundation and university (Bilkent’s

recent rectors were his son-‐in-‐law and his son) (Hatipoglu, 2000; Tekeli, 2010).

YÖK established new universities, appointed rectors, deans, chairs even assistants. It

generated kingdoms (universities) with kings (rectors) who were all loyal to YÖK and

president of the country. In this era, university foundations, rather than foundation

universities, were dominant. Almost every university established foundation(s), and

several companies associated to them, to generate additional income for the university

(Hatipoglu, 2000; Gur, 2011). These times of YÖK until 2008, were marked with

oppression of freedom in the universities. Government and politics were in every

aspect of the higher education life; appointment of faculty, allocation of budgets, etc.

But, most memorably, lack of freedom for students and faculty with hijab was the legacy

of these years. Interestingly, no such cases have taken place in the first foundation

university of the country (Bilkent).

Between 1984 and 2008, around 25 other foundation universities were allowed to open

and operate, particularly after the new government in 2002 (Erdogan-‐AKP government)

(YOK, 2007a; YOK, 2007b; Gur, 2011). Foundation universities offered relatively more

freedom, better academic productive environment; increased research and

publications, etc. mainly since they hired US-‐educated administrators and faculty.

Conflicts between government, YÖK and courts left their marks in this period.

2.6. Recent changes in YOK and emergence of foundation universities (2007-‐2012):

Due to the partial changes in the constitution in 2007, the president of the country was

elected directly by people (Hn. A Gül was the first such president). Hence, since 2008

presidents of YÖK (higher education council) and hence the rectors of all universities

were appointed by such President reflecting the will of people, at least to some degree.

This made significant changes in the universities and YÖK offering freedom to all

students and faculty; and equal university entrance opportunities for all students (issue

11

of vocational high schools). Number of universities increased remarkably to more than

170 (YOK, 2007a, YOK, 2007b, Gur, 2011; YOK, 2012a):

1. 103 state universities

2. 65 foundation universities

3. 7 foundation institutes for vocational education

4. 5+ others (affiliated universities abroad, military academies, etc.)

Number of higher education students increased to ~3 million (including night-‐shifts

and Open University system). But, century-‐old and accumulated problems continue to

hold including: (a) Lack of academic, administrative and financial autonomy and

responsibility, (b) Lack of accountability and transparency, (c) Lack of flexible

management and financing models, (d) Lack of quality assurance systems, (e) Lack of

well-‐prepared faculty and their preparation, (f) Lack of equipped classrooms and labs,

(g) Lack of access to quality higher education for all (YOK, 2007a, YOK, 2007b, Gur,

2011).

In 2012’s numbers, foundation Universities serve only ~10% of student population.

They hold high rankings in terms of (a) attracting the best students (university entrance

exams), (b) low student/faculty ratios (~16-‐18), (c) respected scholars attracted from

western countries; (d) relatively high external research funding per faculty

(~$50K/faculty); (e) relatively good publication per faculty (~1/faculty/year); (f) high

number of international students and faculty (~5-‐10%), (YOK, 2007a, YOK, 2007b, Gur,

2011). Short list of well known and high ranking foundation universities and their

main sponsors is as follows:

• Bilkent University (Ankara, Bilkent Foundation and its companies, Dogramaci

family)

• Koç Univerity (Istanbul, Koc Holding and family)

• Sabancı University (Istanbul, Sabanci Holding and family)

• Economy and Technology University (Ankara, TOBB-‐ Federation of Chambers

of Commerce)

• Yeditepe University (Istanbul, Istek Foundation, Bedrettin Dalan, former mayor

of Istanbul)

12

• Istanbul Şehir University (Istanbul, BSV-‐ Sciences and Arts Foundation, Ulker

Family)

• Fatih University (Gulen group)

3. Higher Education Today and Future with Expected Changes

Although the history of foundation universities in the republic era is quite new, some of

the important and common issues with their establishment and operations can be listed

as follows:

– Most are managed like “a company” of the main sponsor, not in the spirit

of “foundation (awqaf)”

– Lack of leadership and administrative autonomy (dominant sponsor opts

to work with academics who are good in scholarship, loyalty,

trustworthiness, but weak in leadership);

– Lack of financial autonomy due to low levels of financial support from the

sponsors on an annual-‐base, which could be reduced or cut off any time;

– Most lack the necessary space (land) to grow;

– Most lacks long-‐term and autonomous endowments,

– Most are concentrated in three-‐big cities (Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir);

– Most opt to avoid colleges and departments requiring high investments

(mechanical, materials science and civil engineering);

In Turkey, recent economic progress is expected to continue, but slowly. Hence, there

will be an increasing need for higher education, particularly when the size of student

population in the elementary and secondary education is known to be around 16

million (MEB, 2012). Furthermore, preparation of a new civil constitution is underway,

which is expected to offer a more civilized, free, respectful framework for all aspects of

life in Turkey. It is also expected to lay the way for a more flexible, autonomous but

responsible higher education system. Under these circumstances, the number and

variety of foundation universities is expected to increase to encompass mid-‐size cities in

Turkey. Due to increasing competition among foundation and state universities, and

also due to expected quality assurance inspections and regulations under the new

higher education system, “real” foundation universities are expected in addition to

foundation universities sponsored by large family corporations or strong religious

13

groups. Due to similar reasons, some mergers are also expected to accommodate the

needs for competitive higher education market. Among so many state and foundation

universities, some are expected to focus on graduate education and research and

development while some to focus on quality undergraduate education. Mainly due to its

geographical position, historical and political relations, Turkish universities (state and

foundation) are expected to attract increasing number of international students

particularly from immediate neighboring regions (Balkans, Middle East, Africa, Central

Asia, Ukraine & Russia, Sub-‐continent and Eastern Turkistan). Turkish government has

realized the importance of internationalization, and has implemented “Turkiye

Scholarship program” to attract at least 100,000 international students by 2015. In

addition to the students from other regions and countries, almost all universities, but

especially foundation universities, are expected to attract international faculty in terms

of returning brain-‐drainers as well as western educated Muslim scholars. Turkey was

reported to use the largest funds dedicated to integration grants for returning

researchers by FP 2007 (7th Frame Programme) fo European Union Research Council

(Tubitak, 2012).

It is widely known that Knowledge Society and Knowledge Economy demands quality

Human Capital, which in turn depends on an Educational system that is:

• Massive, available to the all of a nation’s population (5 million students in

higher education, 20 million in K-‐12 by 2025 in Turkey)

• Relevant to the needs of the society, economy in the next decades,

• Academically expanded to encompass all subjects of relevant the real needs,

• Self-‐Renewing to accommodate the changing needs and trends over years,

• Flexible to accommodate various students types and needs,

• Various university types (Foundation, State and Private) which are

• Entrepreneurship (4th Generation), not only in science for science,

• International, mobile, tech-‐intensive and flexible,

• Specialized (Medicine, Science, Social, Management),

• Self-‐governance (Financial, Admin and Scientific autonomy)

• Accountable

• Relevant and Responsible to society

14

YOK (Higher Education Council of Turkey) recently announced two draft laws asking

changes in the higher education (e.g. 3rd draft of this kind since 2002) in October and

November 2012 (YOK, 2012b). This draft law, which requires certain changes in the

constitution if the constitution itself is not renewed by 2014, offers a variety of reforms

thought to accommodate the needs of the higher education in the coming decades. One

of the major proposed changes is in the types, and hence financing models, of

universities. With the proposed draft, in addition to state and foundation universities,

private universities, which can be for profit and foreign owned, will be allowed to

operate. However, this draft law and associated changes in the constitution heavily

concentrated on the selection of university administration (rector) rather than focusing

on the increasing the quality of higher education by setting competitive and specific

targets and giving necessary autonomy and responsibility to the universities. Thus, if

not discussed widely and freely to make the necessary improvements in this draft law, it

will be another lost opportunity to engineer the next generation higher education

system of the country.

References

Ergun, M, (2012), “Changes in the Ottoman education system-‐ from madrasah to mekteb” (Turkish: Medreseden mektebe Osmanli eğitim sistemindeki değişme ), http://www.egitim.aku.edu.tr/ergun3.htm (last accessed on Sept. 20, 2012)

Genç, M., (2007), ‘’State and economics in the Ottoman Empire’’ (Turkish: Osmanlı imparatorluğunda devlet ve ekonomi), 4th Ed, Ötüken Publications, Istanbul, Turkey; ISBN 9754373388,

Tekeli, I., (2010), “History of higher education and YOK” (Turkish: Tarihsel baglami icinde Turkiye’de yuksekogretim ve YOK’un tarihi), Tarih Vakfi Yurt Publicatons, Istanbul, ISBN 978-‐975-‐333-‐255-‐2

Hatipoğlu, M.T., (2000), ‘’History of Turkish University’’ (Turkish: Türkiye Üniversite Tarihi), 2nd Ed., Selvi Publications, Ankara, ISBN 975-‐7711-‐29-‐2

YOK, (2007a), “Strategy for Higher Education in Turkey”, www.yok.gov.tr, (last accessed on Sept. 20, 2012)

YOK, (2007b), “Report on Foundation Universities”, www.setav.org.tr , (last accessed on Sept. 20, 2012)

Gur, B.S. And Celik, Z., (2011), “SETA Report on 30th year of YOK”, www.setav.org.tr, (last accessed on Sept. 20, 2012)

YOK, (2012a), www.yok.gov.tr, (last accessed on Sept. 20, 2012) YOK, (2012b), www.yeniyasa.yok.gov.tr (last accessed on November 12, 20, 2012) Tubitak, (2012), www.tubitak.gov.tr (last accessed on November 12, 20, 2012) MEB, (2012), www.meb.gov.tr (last accessed on November 12, 20, 2012) Felsefe Ekibi, (2012)

http://www.felsefeekibi.com/sanat/sanatalanlari/sanat_alanlari_anadolu_selcuklu_mimarisi_medreseler.html