Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

Transcript of Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

In Nicolae Ceausescu’s ‘Systematisation’ programme,implemented across Romania throughout the 1980s,power was played out in acts of building. The city ofBucharest provided a visible symbol of thecentralisation of authority, manifest in theconstruction of the Boulevard of the Victory ofSocialism and the House of the People. Beginning from this historical context, this paper revisits thework of one group of student architects in Romania,Form-Trans-Inform, who used spatial practices toquestion orthodoxies in architecture around them asprotests against repressions under the monolithicCeausescu regime.

For Form-Trans-Inform, a diverse programme ofevents served to accentuate, critique and resist thespecific confines and symbolic topographies overlaidon particular sites by the actions of the Ceausescuregime. Yet, while they provided an alternative to the‘communist intellectual uniformity’, theseperformative spatial practices also allowed these young architects to invent a form of contemporaryarchitectural sensibility that was specific to theirparticular political condition. The work of this group,the political context and the wider milieu of resistancein which it operated in Romania at this time has beenrecorded elsewhere by the author.1 However, in thelight of a ‘defined need to develop new models ofarchitectural praxis’ and with new digital technologiesallowing a greater extent of the work to be reviewed,this paper revisits selected practices of this group toexplore how they begin to develop a theoreticalargument about alternative practice.2

ContextBucharest: the Ceausescu regimeUntil its collapse in December 1989, the RomanianCommunist system permeated all levels of societalrelations embracing politics, everyday life andarchitectural expression. A multitude of interpersonaland spatial rules combined to produce very realcorporeal effects and subjectifications. In Romania inTurmoil, Martyn Rady explains how the ‘pervasiveinfluence’ of the security apparatus and the rotation inoffice of rivals for power prevented any opposition ingovernment.3 At the same time, everyday Romanians

experienced a ‘profound sense of resignation’, largelyattributed to ‘the constant dissipation of intellectualand physical energy in the mundane task of obtainingsufficient food, warmth and medicines to go onliving’.4Meanwhile, for the middle classes,Government patronage was traditionally regarded asthe ‘key to material prosperity’ and for intellectualsthe only way to be published and achieve notoriety was by acknowledging support for Ceausescu.5 Evenmore than other Eastern European political regimes,Ceausescu’s regime understood the effectiveness ofFoucauldian ‘micro-powers’ as pervasive agents ofcontrol expressed throughout all societal levels.6

Moreover, the potential for acts of architecture to extol admiration, embody authority and maintain‘obstinate force’ was a power Nicolae Ceausescumanipulated to its extreme.7

Ceausescu’s role as self-appointed head architect was produced by and supportive of the performativepotential of urban planning, making it clear that withone sweep of his hand he could destroy or relocateentire districts. The construction of the House of thePeople and its ostentatious Boulevard of the Victory of Socialism generated enormous operations ofdemolition and for those who lived in its shadowrepresented ‘a massive effort to ensure total visualdomination of the city’ [1–3].8 Moreover, throughoutthe 1980s Ceausescu implemented his Systemisationprogramme involving the destruction of numeroushistoric buildings in Romania’s towns, and the razingof vast numbers of villages to be replaced bystandardised apartment blocks promising betterliving standards. In fact, this Systemisation was moreakin to a social engineering exercise with the ultimateideological target being ‘the homogenization of theRomanian socialist society […] and theaccomplishment of a single society of the workingpeople’.9 In this deeply prescribed context, wherepower was played out in performative acts of building,architecture seemed to lose all alternate meaning than that expressed through its exclusive use as aninstrument of power. However, a handful ofindividuals and young architects strove to reclaimsuch an alternate meaning through spatial practicesthat protested against the restrictions of the regime.

theory arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 149

theoryThe contemporary significance for alternative forms of architectural

praxis is explored by revisiting the protests of young Romanian

architects resisting repression under the Ceausescu regime.

Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’resistance in architectureHelen Stratford in conversation with Doina Petrescu and Constantin Petcou

arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 theory150

Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

1

2

1 Ceausescu’s role asself-appointed headarchitect made itclear that with onesweep of his hand hecould destroy orrelocate entiredistricts

2, 3 For those who lived in its shadow,the construction ofthe House of thePeople and theBoulevard of theVictory of Socialismrepresented ‘amassive effort toensure total visualdomination of thecity’

3

Form-Trans-InformBuildings are inexorably allied to those with themeans and power to fund and implement them. InRomania, Ceausescu dominated all structures ofpower, with which many architects were complicit.To resist these structures almost inevitably meantnot building anything at all. Nevertheless, at variousfissures in the landscape of architectural entities,which existed in Romania during its context ofrepressive dictatorship, work was created, byindividuals and small groups of young architects, ofwhich the very presence challenged the restrictionsof the regime. Such work was found within thearchitectural schools of Bucharest and Timisoara,among students and educators, within a few firms ofyoung architects and outside both these traditionalinstitutions of the profession altogether, in the workof small independent groups including theinterdisciplinary group Form-Trans-Inform.

Form-Trans-Inform began in 1980. Its eight coremembers came from the School of Architecture andthe Ion Grigorescu Institute of Arts in Bucharest. Thearchitectural students from the Bucharest School ofArchitecture were Constantin Petcou, ConstantinGorcea, Alexandru Chitul, Neagoe Florin, SorinVatamaniuc, Deacu Doru and Doina Petrescu. LaviniaMirsu studied at the Ion Grigorescu Institute of Artsand was a scenography student. In the generalcontext of a privation of rights and lack of materialeffects – food, fuel, access to technology andinformation – Form-Trans-Inform devised a diverseprogramme of research and experimentationincluding meetings, seminars, papers, projects,exhibitions, performances and events. These were allrecorded by a variety of methods includingphotographs and 8mm film. Recent DVDtransference of these archive films, made within thespecific material conditions of the 1980s in Romania,has enabled the extent of these activities and specificsensibilities in relation to their social and politicalcontext to be re-viewed. At the time they were made itwas strictly forbidden to own a camera, all existingcameras and typewriters were tracked by Statesecurity, and the unavailability of tapes andprocessing materials made processing impossible.Under such repressive circumstances the practices ofForm-Trans-Inform aimed ‘to resist [...] thecommunist intellectual uniformity, to keepourselves in touch with the contemporary sensibility[in architecture], and maybe to invent a specific formof that sensibility through our specific conditioninside the Romanian dictatorial regime’.10

Contemporary architectural practiceArchitecture as a medium for cultural expressionnecessarily reflects prevailing cultural and socialconditions. In ‘Scratching the Surface’, SarahWigglesworth describes how the architecturalprofession in its historical and conventional contextoperates at many levels to control what knowledge islegitimate and what is irrelevant within itsproduction. This knowledge determines concepts ofcreativity and the importance (or not) to architectureof related disciplines. At the same time, whether at

the level of individual buildings or urban design,building projects invariably prevail as expensivecommodities that promote social and spatialsegregation in their bid to perpetuate wealth. In thisway a multitude of assemblages – social, economic,environmental, cultural, linguistic as well as legal –demand of the architect ‘particular kinds ofpersonal behaviour and social relations’.11 ForWigglesworth, a critical practice must acknowledgeand find ways of addressing the means throughwhich architecture is produced and explore theirimplications, ‘ultimately its aims must be to proposealternative identities for the architect, whichbroaden the relevance of architecture and producemore liberating ways of working’.12

While parallels in the work of Form-Trans-Informcan be drawn to arts movements located withintransforming political structures from the 1960s tothe 1980s, the specific conditions of the Ceausescuregime cannot be directly compared to those of otherpolitical contexts.13 However, this paper argues thatthe critical positions of the practices of Form-Trans-Inform combined with an awareness of theimportance of architecture as a social space – taking itout of the narrow disciplinary confines to which theprofession conventionally adheres and situating it inan extended context of spatial practices and processes– is a transferable aspect from which a theoreticalargument about alternative practice can begin to bedeveloped.14 Ultimately, through revisiting this work,this paper argues that notions of practised, performedand interdisciplinary spaces, involving dynamicmodels of place, are relevant and necessary for re-thinking conventional architectural assumptions,finding alternative ways of engaging with the builtenvironment and proposing alternative forms ofarchitectural education within contemporaryconditions of architectural production.

The institution – ‘a school within the school’The pervasiveness of the Ceausescu regime extendedthroughout entire societal structures, manifest ineveryday operations including education. Anyresistance to such an omnipresent regime provedextremely difficult, dangerous and fragmented,constituting a ‘plurality of resistances’.15 Groups ofdissident intellectuals and artists, who made up thedisparate avant-garde or pockets of resistance inBucharest, were largely isolated within their separatefields, in itself a symptom of the exercise of powerthrough the regulation of disciplinary boundaries.In the early ’80s the Bucharest School of Architecture(Institutal de Arhitectura Ion Mincu (iaim)) served asan enclave for work created at this micro-level.16

Form-Trans-Inform worked with other students andteachers to organise a ‘school within a school’ bypromoting a parallel teaching programme that wasdiametrically opposed to those teaching methodsand values held by the official ‘abstract andfunctionalist’ school. In place of the core studies,dictated by Ceausescu, which included economic,political theory and socialist idealism,17 this parallelteaching programme attempted to access a differentmodel of knowledge that was at once ‘experimental,

theory arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 151

Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou

analytic and holistic’. By embracing exhibitions,events, actions and happenings; supported byreadings, thematic discussions of prohibited textsand screenings of scientific, art and documentaryfilms borrowed from the Western Embassy libraries,Form-Trans-Inform initiated a critique of theinstitution in which they were enrolled.-Trans-Inform initiated a critique of the institution in which they were enroll18

Within the School of Architecture, Form-Trans-Inform took part in two exhibitions organised byyoung avant-garde artist Wanda Mihuleac. The firstexhibition, Spatiu-Obiet (or Space-Object), took place inautumn 1982. Around twenty people took partincluding artists, architects, and students. All wereinvited by Mihuleac to exhibit both architectural andart installations. A review of the show – grantedpublication in the Union of Romanian Artists’journal Arta because its narrow circulation renderedit politically harmless – commented that it had‘attempted to organize space through different

qualifications in the same way as Joseph Beuys hadproposed to create an integral system byamalgamating social sciences and art’.19 However, thehead of the school refused to grant officialpermission for the opening of the section displayingthe architecture students’ work. Therefore, this partof the Space-Object exhibition was never officiallyopened to the public. The participating students andarchitects had to open it themselves, and then, it was‘tolerated’ [4].20

The second exhibition, Spatiu-Oglinda (or Space-Mirror), was planned as a continuation of the first.The scale of this second event, arranged again byMihuleac and programmed for 1986, was much moreambitious incorporating around seventy people,including many important intellectuals and artists.However, in a clear demonstration of the restrictiveevolution within the political regime, this secondexhibition only managed to open for a few daysbefore it was censored and subsequently terminated,receiving no publicity whatsoever. The officialreasoning behind the closure of the exhibition was,‘It didn’t reflect the social reality’.21

While invariably the subject of authoritariancensorship and exclusion, such actions weresymbolically important for students and teachers inthe school at that time, as they made visiblealternatives to the ‘communist intellectualuniformity’.22 In addition, identified as a group ofresistance, Form-Trans-Inform were invited toparticipate in different collaborative and collectiveactions by dissident individuals and groups. Thesecollaborative actions challenged the isolation of thesedisparate pockets of micro-resistance – adding to themthrough solidarity, mutual recognition and support.

arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 theory152

Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

5

4

4 The Form-Trans-Inform, Space-Objectexhibition at theBucharest School ofArchitecture, autumn1982, was neverofficially permitted.Students andarchitects had toopen it themselves

5 Actions in the city ofBucharest discoveredand invested withpoetic valuearchitecturalelements which weregoing to disappear,responding to theimminent demolitionof the city fabric.Form-Trans-Inform,Traces, Bucharest,February 1981

Actions: the (collective) bodyIn Traces, site specific actions interacted with existingbuildings. Conversely, during March 1982, Structura(or The Structure) was an action staged within theBaneasa forest that concentrated on building newcollaborative structures in response to thesurrounding environment. Various installations anda ‘happening’ contemplated the question ofconstructing a structure within the forest whichbridged subjectivity and nature. Works created inresponse to this theme were entitled The Life Structure,Temporary Structures (marking ways to get out of theforest) and The Sexual Structure (supporting Man andWoman in the forest).

The aims of Form-Trans-Inform in relation to TheStructure were directed towards ‘learningarchitecture in/from the forest’, makingperformative and collaborative architecture that wasat once ‘fragile and vulnerable’.26 Installations andperformances were used to appropriate sitesthrough a combination of built constructions andsocial actions. Still photographs of The Structure gosome way to communicate the intersections ofbodies and place made through these collaborativeconstructions. Yet, the films make clear the extent towhich the performative living aspect of the processesinvolved in all the actions was the key aspect of thework [6, 7].

In ‘On the Production of Subjectivity’, the firstchapter of Chaosmosis, Félix Guattari describes how‘machines of subjectification’ combine to producesubjectivities.27 For Guattari, these machines are notdelimited to ‘internal faculties of the soul,interpersonal relations and intra-familial complexes’but are found in ‘non-human machines such associal, cultural, environmental or technologicalassemblages’.28 With notable significance for theCeausescu regime these include ‘the large scale social machines of language and the mass media’.29

For Form-Trans-Inform, active and physical actionsbecame the ultimate site of resistance against thedirect and symbolic violence to which their bodiesand subjectivities were submitted under thetotalitarian regime.30 Yet, for Guattari the notion of‘complexes of subjectification’ also contains thepotential for resingularising practices. Thesecomplexes, including ‘relations with architecturalspace’, ‘actually offer people diverse possibilities for recomposing their existential corporeality, to get out of their repetitive impasses and […] toresingularise themselves’.31 In addition to resistancethen, Guattari’s ‘complexes of subjectification’ alsooffer the possibility of creating new modalities ofsubjectivity; new places to speak and act from.

In the face of alienation and humiliation, theperformances and practices of Form-Trans-Informconfirmed the central role of the body, so resistingthe machines of subjectification that producedspecific models of acting and thinking. However,these physical practices also re-choreographed thehidden and liminal spaces to which they wererestricted. Collaborative actions, involving climbing,jumping and balancing, enabled access to theseoverlooked and disregarded places but also

theory arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 153

Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou

Actions: the cityOnce a month between January 1981 and March 1982,Form-Trans-Inform held a series of meetings entitled ‘actions’, with additional participation from contributors outside the group. These ‘actions’took place in disregarded and dilapidated areas of Bucharest and in forests and countryside outsidethe city. The importance of such practices and theirrelevance as a form of resistance becomes evidentwhen one comprehends that their locations were adirect response to the strict political surveillancepresent in Bucharest.

The actions organised within the ruins of Bucharestconcentrated on disintegration and disappearanceover time, working within and reacting to extremeenvironments where surrounding buildingsgradually vanished. One such action was entitledTraces. Located within the historic Opereta district, itwas programmed during February 1981 in a houseintended for demolition during the five year processwhich razed this entire district for the construction ofCeausescu’s House of the People. Each person in theaction took one room and inaugurated some kind ofintervention which responded to the house, such as aperformance or an installation. Through re-inhabiting the house these interventions discoveredand invested with poetic value architectural elementswhich were going to disappear [5].

In her paper ‘Living Virtually in a Cluttered House’,Eleanor Kaufman describes how the perception ofthe space around us is premised on a set ofassumptions – conventions and rules that have ‘realbearing on the ways lives are lived’.23 Likewise, forfeminist theorist Moira Gatens these conventions,that are dependent on language, time, place andaudience, do not merely describe or represent, butintervene in the world, functioning to organise its‘social character’. They instigate a ‘framework ofintelligibility’ which maintains explicit propositionsabout bodies and places, deciding what types ofutterances may be ‘legitimately’ extracted fromthem.24 In Traces, a house that had become‘legitimately’ abstracted as an obstacle to totalitariancity planning was reinvested with memory andnarrative through an assemblage of bodies, practicesand place. In this way, the performances focused onactions and gestures in processes of inhabitation toproduce a physically registered yet anecdotaltopography or set of haunted sequences rather thana functional urban landscape or city.

The house eventually fell to the demolition squads.In this context the intervention was seen by Form-Trans-Inform as ‘a last and useless gesture of futurearchitects’. However, they also saw it as ‘a first gestureof resistance of future architects’.25 In redefining thisplace identified for destruction, the gestures ofForm-Trans-Inform formed a critique of the brutalityof the orthodox Romanian architectural ideology ofthat time; confronting the social, spatial andtemporal logic of the regime. At the same time theyallowed a momentary reversal andrecontextualisation of this place, complicating theperceptions of this particular house and releasing it,if momentarily, from its specific script.

translated them into a series of personal andcollective territories. This change of focus allowedthese spaces, in the countryside, in the forest and indilapidated buildings, to alter. Further, inappropriating and redefining these spaces throughsocial actions, which confirmed the body’srelationship to the world and other bodies, theactions of Form-Trans-Inform undermined theideological control of architecture as a physical spacefor the representation of power. Instead, buildinghere was performed as an unfolding series ofprocesses and practices that held the possibility tocreate and enact another reality than thatperformed by the actions of the regime.32

arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 theory154

Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

6

7

6 Active and physicalactions became theultimate site ofresistance againstdirect and symbolicviolence to whichbodies andsubjectivities weresubmitted under thetotalitarian regime.Form-Trans-Inform,The Structure,Banasea forest,March 1982

7 Collaborative andperformativeconstructions wereused to appropriatesites through acombination of builtconstructions andsocial actions. Form-Trans-Inform, TheStructure, Banaseaforest, March 1982

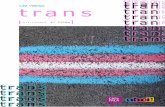

8 Political protest wasexpressed ‘lessideologically, andmore poetically’.Form-Trans-Inform –Radical DesignStudio, Mast to Itaca,Japanese IdeasCompetition, 1986

ConclusionPoetic resistanceUnder the regime places and subjectivities played akey role in preserving hegemonic relations of power.In this context, the ‘actions’ of Form-Trans-Informprovided a site for resistance. Rather than direct actsof political protest that would have elicitedimmediate repression, the group’s practices ofresistance were composed of subtle slippages andsubversions. Against the particular forms ofsubjectification experienced under the regime, theyoperated through incremental moves at the micro-level to resist the local impositions of dominatingpower. As a former member of Form-Trans-Informdescribes:

‘We were not engaged in a direct political critique – asprotest or political demonstrations […] but indirect,embedded in internal codes and hidden meanings shared by those that were able to read them. It was aresistance through alternative discourse, throughalternative ways of thinking and doing, alternative life style.’33

Rather than oppose one ideology to another, thealternative actions of Form-Trans-Inform expressedtheir political protest ‘less ideologically and more

poetically’. Indeed, the poetic was their way ofresisting the subjective violence of the Ceausescudictatorship. For the group the political and thepoetic were not separated, ‘to the power thatinfiltrated our life with ideology, control andrestriction we replied with a poetic form of life,which kept alive our sensorial, intellectual andaffective capacity’.34

Manifestations of resistance are always contextspecific. This context must provide the pretext forunderstanding the work and extent of resistance. Intheir aim to invent a practice that could not bereadily categorised under abstract or functionalistmodes of architectural expression, Form-Trans-Inform implemented a form of resistance thatmoved the political into new discursive areas. Lessideologically charged than affirmative and creative,this poetic resistance enabled a different kind ofdialogue. While direct political influences willalways be difficult to discern, through operatingwith the power of the micro-political, as a preciseform of resistance, the poetic resistance of Form-Trans-Inform provided ‘intellectual and moralsurvival’ that in time created conditions for macro-political change [8].35

Critical practiceFor Form-Trans-Inform, the institution was thestarting point for a parallel programme thatattempted to access different forms of knowledge,teaching and learning approaches than those of theofficial ‘abstract and functionalist school’. Thepresence of the group at alternate exhibitions wassymbolically important in demonstrating thatalternatives to the ‘communist intellectualuniformity’ existed, even if these events were rapidlycensored and terminated with little or no publicity.In addition, this presence created connections withother disciplines and disparate pockets of micro-resistance; challenging disciplinary boundarieswhile offering support and solidarity. In the city, inthe place of the relentless programme of demolition,‘actions’ re-inhabited with memory and narrative anexisting building that had become abstracted as anobstacle to totalitarian city planning; forming acritique of the Romanian architectural ideology. Inthe forest, the collaborative and performativeconstruction of new structures affirmed theimportance of the body; resisting the direct andsymbolic violence to which bodies and subjectivitieswere submitted. Yet, at the same time, these socialactions also worked to shift the symbolictopographies that had become overlaid on sites ofarchitecture under the totalitarian regime.

Under Ceausescu the societal practices of theregime constructed certain kinds of body withparticular kinds of subservient power and capacity.This marking in turn created specific spatialconditions in which these bodies lived and recreatedthemselves. Rather than accept these conditions,Form-Trans-Inform focused on the production ofplace through societal practices in order to proposealternate practices that produced place differently.In the face of passive isolation, alienation and

theory arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 155

Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou

8

humiliation, the group explored the inextricablerelationship between social actions and physicalspace in order to shift existing conceptions regardingspecific subjectivities and alter the places throughwhich they were produced. By reclaimingarchitecture as an affirmative and collaborativepractice, rather than an instrument of power, thepractices of Form-Trans-Inform worked to take it outof a long established and exclusively damagingcontext. Instead, through spatial practices located inthe school, the city and the forest, architecturebecame the site of a collective challenge; reclaimed,opened up and turned in the direction of expandingpolitical processes – creating new subject positionsfrom which the group could speak and act.

By working at the different levels of teaching, ofbuildings, of the body and subjectivity, Form-Trans-Inform developed a critique of the conditions bywhich the processes involved in the production ofarchitecture operated within the particular confinesof the dictatorial regime. Largely devoid of materialsources and restricted to hidden and liminal spaces,the practices of the group explored building as anunfolding series of processes and practices; at oncepedagogic, political, social and material. This form ofinstitutional critique, that places architecture in abroader context of spatial practices and social action,is an approach that is extremely relevant for findingways of addressing the means through which

architecture is produced and exploring theirimplications in the contemporary context. Ratherthan imposed or abstract representations ofidentities and places, this approach to buildingattempts to rethink places as situations or‘assemblages’ and find ways of working that evolveinstead from exploring the processes and practiceswhich constitute a place and which it constitutes.36

Ultimately, the work of Form-Trans-Informembodies an approach by which a collective criticalpractice might also be creative. It points towards apoetic practice that can envision and express thepossibility of things being otherwise withoutbecoming so enamoured of power that it omits toquestion its own socio-political interventions.37

Poetic here then also embodies the sense of theGreek poïesis – making, and in the case of Form-Trans-Inform: ‘making another world in which itwill be possible to live, to breathe, to dream’, that‘started with the school – with the poetical inventionof another school, and way of teaching in which werestored, first of all, the dignity of ourselves’ [9].38

arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 theory156

Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

9

9 ‘We were neithermarginal, nor heroes,but tried very hard toremain “normal”.’Through a diverseprogramme of eventsForm-Trans-Informaimed to resist the

‘communistintellectualconformity’. Form-Trans-Inform – RadicalDesign Studio,Medium-Media,September 1989

Notes1. For a more extended discussion of

these practices see Helen Stratford,‘Enclaves of Expression’, Journal ofArchitectural Education, 54.4 (May2001), 218–228.

2. Alternative Architectural Practice,research project, School ofArchitecture, University ofSheffield, 30 May 2007,<http://altpraxis.wordpress.com>[accessed 19 March 2008].

3. Martyn Rady, Romania in Turmoil(London: I. B. Tauris & Co., 1992), p. 57.

4. In Ceausescu’s determined attemptto pay off the national debt,imports were minimised andalmost everything that could besold abroad was exported. Foodbecame scarce and fuel wasseverely rationed, households wereallotted only one 40-watt bulb perroom, cooking was often limited tothe middle of the night, andsometimes even the traffic lightsstopped working. R. J. Crampton,Eastern Europe in the TwentiethCentury (London: Routledge, 1994),p. 385.

5. Rady, Romania in Turmoil, p. 59.6. Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge:

Selected Interviews and Other Writings1972–1977, ed. by Colin Gordon(Brighton: The Harvester Press,1986), p. 98.

7. Doina Petrescu, ‘The People’sHouse, or the Voluptuous Violenceof an Architectural Paradox’, inArchitecture and Revolution, ed. byNeil Leach (London: Routledge,1999), pp. 188-195 (p. 192).

8. Constantin Petcou, ‘TotalitarianCity: Bucharest 1980–9, Semio-clinical Files’, in Architecture andRevolution, pp. 177–187 (p. 182).

9. Dinu C. Giurescu, The Razing ofRomania’s Past (Bath: The BathPress, 1990), p. 42. Giurescudescribes how this ideologicaltarget aimed to instigate ‘areduction of the main differencesbetween village and town and theaccomplishment of a single societyof the working people’.

10. Doina Petrescu and ConstantinPetcou, email correspondencewith the author, Paris-Cambridge,7 January 1998.

11. Sarah Wigglesworth, ‘Scratchingthe Surface: The Case for a MaterialArchitecture’, in Transmission:Speaking & Listening, vol. 2, ed. bySharon Kivland and LesleySanderson (Sheffield HallamUniversity/Site Gallery, 2003), pp. 105–113 (p. 107).

12. Ibid.13. These manifestations of resistance

by Romanian architects, duringthe years of the Ceausescu regime,form part of a larger study by theauthor. The scope of that study

stretches wide geographically andpolitically. It covers work situatedboth within a number oftransforming political structures,including South Africa, Russia andEast Germany, and spanning acrossthem. See Helen Stratford, ‘Micro-movements of Resistance: TheQuestioning of Orthodoxies byYoung Architects in the East andWest in the 1980s and Early 90s’(unpublished dissertation forDiploma in Architecture,University of Cambridge, 1998).

14. In Critical Architecture Jane Rendellunderlines the importance of acritical practice that placesarchitecture in an‘interdisciplinary field of activity’.Jane Rendell, ‘Critical Architecture:Between Criticism and Design’,introduction to Critical Architecture,ed. by Jane Rendell, Jonathan Hill,Murray Fraser and Mark Dorrian(Oxon: Routledge, 2007), pp. 1–8

(p. 5).15. Michel Foucault quoted in Michael

Walzer, ‘The Politics of MichelFoucault’ in Foucault: A CriticalReader, ed. by David Couzens Hoy(Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986), pp. 51–68 (p. 55).

16. In relation to other academicinstitutions in Romania, IAIM wasthe most permissive. Thedemonstration of such tolerancecan be seen in two examples ofevents which took place within theSchool. The first: the existence ofthe ‘Club A’, where undergroundartists, musicians, writers and filmmakers were invited to show theirwork and speak. Political puns andjokes were heard there until1984/1985. The second: theorganisation by the School of twoInternational Seminars ofArchitecture, in 1982 and 1984, towhich some of the mostprominent internationalarchitects of the time were invited.It was evidence of the two-wayeffect of these boundaries that veryfew actually accepted theinvitation. Ideological support forthis activity came from theCommunist Party Secretary of theSchool who used his ‘socialistfriendship’ connection with NicuCeausescu, the son of NicolaeCeausescu, as a way of attainingsome level of freedom for theSchool and its students. DoinaPetrescu and Constantin Petcou,email correspondence with theauthor, Paris-Cambridge, 21

October 1997.17. The core studies, dictated by

Ceausescu, included economic andpolitical theory, and ‘socialist’idealism, forced into all the lectureprogrammes and teachingpractices. Louise Rodgers, ‘Testing

Times’, The Architects’ Journal(23 May 1990), p. 26. Doina Petrescuand Constantin Petcou, ‘Form-Trans-Inform: The “Poetic”Resistance in Architecture’, paperpresented at Alternate CurrentsSymposium, Sheffield UniversityDepartment of Architecture, 26/27

November 2007.18. The first venture in which Form-

Trans-Inform participated was anexhibition entitled Om-Oras-Naturaor Man-City-Nature in 1980. Theexhibition formed part of a largerevent and seminar involvingaround eighty people comprisingphilosophers, artists, scientistsand architects. The event wasorganised by Constantin Petcou incollaboration with WandaMihuleac and Mihai Driscu andwas held in the Botanical Gardenof Isai at the Moldavian edge ofRomania. A review of theexhibition describes how it showeda ‘restrained but relevant slice ofresearch and dreams concerningnew correlations of the terms ofplace, dwelling place and urbanplace concentrating on the tensionbetween “nature” and the urbanfortress of the city’. TheodorRedlow, ‘A Question Always Open.Men-City-Nature’, Arta, 1 (1982),10–12.

19. Mihai Driscu,‘Spatiu-Obiet’, Arta, 4(1983), 10–13. Although the articleitself was well illustrated, it madeno allusions to the underlyingmotives of the show. Mihai Driscusuffered harassment due to his rolein resistance activities. He waskilled under mysteriouscircumstances in a car accident in1985.

20. Doina Petrescu and ConstantinPetcou, email correspondencewith the author, Paris-Cambridge,14 December 1997.

21. Ibid.22. Doina Petrescu and Constantin

Petcou, email correspondencewith the author, Paris-Cambridge,7 January 1998.

23. Eleanor Kaufman, ‘Living Virtuallyin a Cluttered House’, Angelaki, 7.3(December 2002), 159–169 (p. 161).

24. Moira Gatens, ‘Through aSpinozist Lens: Ethology,Difference, Power’, in Deleuze: ACritical Reader, ed. by Paul Patton(Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1996), pp. 162–187 (p. 178).

25. Doina Petrescu and ConstantinPetcou, email correspondencewith the author, Paris-Cambridge,19 December 1997.

26. Ibid.27. Félix Guattari, Chaosmosis: An

Ethico-aesthetic Paradigm, trans. by Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis(Bloomington & Indianapolis:Indiana University Press, 1995), p. 9.

theory arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 157

Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou

arq . vol 12 . no 2 . 2008 theory158

Stratford, Petrescu and Petcou Form-Trans-Inform: the ‘poetic’ resistance in architecture

28. Phillip Goodchild, Deleuze andGuattari: An Introduction to the Politicsof Desire (London: Sage, 1996), p. 15.

29. Guattari, Chaosmosis, p. 9. In thetime preceding and leading up tothe revolution in 1989, relentlessrestrictions were enforced againstthe media. During the 1980s,television viewing was reduced totwo hours a day, half of which wasdevoted to presidential activities.

30. ‘Everybody was supposed to followthe same model, to look and tothink the same. We didn’t havemany other means to makearchitecture at that time whereeverything was controlled, wherethe architecture we liked wasdemolished, and a horriblearchitecture was constructed in itsplace.’ Petrescu and Petcou, ‘Form-Trans-Inform’.

31. Guattari, Chaosmosis, p. 7.32. ‘We have developed body

techniques (as some activistsmight do today) to prove thecentral role of the body (the bodyof the architect maybe), but also oflife I could say, and itsrelationships with the world. Thismight also resemble some bodypractices today – parkour, skate,etc. We were practising yoga, andbody training to manage to climbon things, to get insideinaccessible places, etc.Resubjectivation, groupresubjectivation – sharing ourdifferences, helping each other tokeep our mind. Throughperformance we created andenacted another reality even ifonly for a while.’ Petrescu andPetcou, ‘Form-Trans-Inform’.

33. Ibid.34. Ibid.35. Ibid.36. Gilles Deleuze describes how ‘one

never desires something […] butrather always desires anaggregate’. Gilles Deleuze,

L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze, withClaire Parnet, trans. by Charles J. Stivale (Wayne State University,Roman Languages and Literatures1989), <http://www.langlab.wayne.edu/C.Stivale/D_G/ABC2.html>[Accessed 19 March 2008].

37. For a greater discussion ofperformance as a critical practicesee Vikki Bell, Culture andPerformance: The Challenge of Ethics,Politics and Feminist Theory (Oxford:Berg, 2007).

38. Petrescu and Petcou, ‘Form-Trans-Inform’.

Illustration creditsarq gratefully acknowledges:Arhitectura, 3Author, 2Form-Trans-Inform, 4–7

Radical Design Studio (Doina Petrescuand Constantin Petcou), 8, 9

Acknowledgements I am grateful to Doina Petrescu andConstantin Petcou for revealing theconditions in Ceausescu’s Romaniathrough ongoing conversations fromParis and in Sheffield. I would also liketo acknowledge the late Dr. CatherineCooke, Cambridge, for advice anddirection on earlier research thatprovided the background to thiscurrent paper.

This paper is a development of anearlier paper presented at theAlternate Currents Symposium,Sheffield University Department ofArchitecture, 26/27 November 2007.The paper took the form of aconversation between the author asresearcher, Doina Petrescu andConstantin Petcou, former andfounding members of Form-Trans-Inform respectively.

BiographiesHelen Stratford is an architect andindependent researcher. Residentarchitectural fellow, Akademie

Solitude, Stuttgart 2004–05, she iscurrently architect at Mole,Cambridgeshire,www.molearchitects.co.uk, member of feminist architecture/art collective ‘taking place’,www.takingplace.org.uk and creativepractitioner, Arts Council England.

Doina Petrescu is an architect andsenior lecturer at the University ofSheffield, and was a member of Form-Trans-Inform between 1983 and 1984.

Constantin Petcou is an architect andresearcher. She was a foundingmember of Form-Trans-Inform.

Constantin Petcou and DoinaPetrescu are founding members ofatelier d’architecture autogérée, anetworked practice initiated in Parisin 2001 which includes architects,artists, urban planners, landscapedesigners, sociologists, students andresidents who conduct research intoparticipatory urban actions.www.urbantactics.org

Author’s addressesHelen Stratford73 Carter StreetFordhamEly, Cambridgeshire cb7 5jt

uk

Doina PetrescuSchool of Architecture Arts TowerUniversity of SheffieldWeston BankSheffield s10 2tn

Constantin Petcou atelier d’architecture autogerée 15 rue Marc Séguin 75018 [email protected]