Fire, People and Pixels: Linking Social Science and Remote Sensing to Understand Underlying Causes...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Fire, People and Pixels: Linking Social Science and Remote Sensing to Understand Underlying Causes...

Human Ecology, Vol. 33, No. 4, August 2005 ( C© 2005)DOI: 10.1007/s10745-005-5156-z

Fire, People and Pixels: Linking Social Scienceand Remote Sensing to Understand UnderlyingCauses and Impacts of Fires in Indonesia

Rona A. Dennis,1,8 Judith Mayer,2 Grahame Applegate,3

Unna Chokkalingam,1 Carol J. Pierce Colfer,1 Iwan Kurniawan,1

Henry Lachowski,4 Paul Maus,4 Rizki Pandu Permana,5 Yayat Ruchiat,1

Fred Stolle,6 Suyanto,5 and Thomas P. Tomich7

This study in the wake of 1990s fire catastrophes identifies and analyzesunderlying causes of vegetation fires in eight locations across Borneo andSumatra. Multidisciplinary and multiscale analysis integrates geospatial tech-nologies with varied social research approaches and participatory mapping.It helps fill a void of site-specific evidence on diverse underlying causes ofthe Indonesian fires, despite emerging consensus on macrolevel causes andimpacts, and policy debates on preventing future fire disasters. Our most im-portant findings include confirmation of multiple direct and underlying firecauses at each of the eight locations, no single dominant fire cause at anysite, and wide differences in fire causes among sites. Conclusions empha-size the importance of location specific studies within a regional analyticalcontext. Our “hybrid” research methods demonstrate the explanatory powerof integrating geospatial and social analysis techniques, and the benefits ofanalyzing fire causes and impacts at multiple scales in varied locations acrossdiverse regions.

KEY WORDS: fires; underlying causes; remote sensing; GIS; participatory mapping;Indonesia.

1Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor, Indonesia.2Independent Researcher.3URS Forestry, Jakarta, Indonesia.4Remote Sensing Applications Center; USDA Forest Service, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.5World Agroforestry Centre, Bogor, Indonesia.6World Resources Institute, Washington, USA.7World Agroforestry Centre, Nairobi, Kenya.8To whom correspondence should be addressed; e-mail: [email protected].

465

0300-7839/05/0800-0465/0 C© 2005 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc.

466 Dennis et al.

INTRODUCTION

Fire has long been a feature of the humid tropical landscape of In-donesia as a tool in farming or land clearing, as a weapon in social conflict,or as a result of accidental or unintended actions (Tomich et al., 1998a).However, since the “Great Fire of Borneo” in 1982–1983, large-scale fireshave become an increasingly significant feature of landscape disturbanceand deforestation in western Indonesia (Malingreau et al., 1985; Siegertet al., 2001b). In addition to climatic factors, evidence from Indonesia andthe Amazon suggests that increased logging and large-scale developmentsin tropical rainforests, and an extension of modified forest in general, haveled to an increased fire vulnerability and incidence by creating a positive-feedback loop whereby fire-affected forest becomes more prone to repeatfire damage (Cochrane et al., 1999; Nepstad et al., 1999; Siegert et al., 2001b).

The worst fires in recent times occurred during the 1997–1998 El Nino-induced drought when at least 11.7 million hectares of forest, farmland andother vegetated land in Indonesia were destroyed or badly damaged (AsianDevelopment Bank, 1999; Tacconi, 2003). The effects of this environmen-tal and humanitarian disaster were felt across the region as smoke and haze,and the fires themselves adversely affected the health, property and liveli-hoods of some 75 million people (Barber & Schweithelm, 2000). The eco-nomic costs exceeded US$ 6 billion with carbon emissions high enough toelevate Indonesia to one of the largest global polluters (Asian DevelopmentBank, 1999; Glover & Jessup, 1999; Page et al., 2002; Tacconi, 2003).

Specific national-level reforms in land-use planning policies to addressrisks of large-scale land clearing and burning have been recommended bya diverse array of Indonesian forestry and environmental officials, non-governmental environmental organizations, international aid and technicalorganizations, and governments of neighboring nations (Murdiyarso et al.,2004). Many of these focus on ways to eliminate all land-clearing fires onpeat land, and call for site-specific assessments of risks of land-clearingor land-use “conversion,” whether or not it involves burning (Applegateet al., 2001; Barber & Schweithelm, 2000; Tacconi, 2003). Under reformsafter 1998 and the regional autonomy regulations since 2001, numerousland allocation processes suddenly devolved to provincial and districtgovernments. Environmental and indigenous rights advocacy groups haveinsisted on land-use decision making processes that directly address theinherent conflicts between commercial land developers and customarycommunities, as well as others managing land for local livelihoods orconservation (Tomich et al., 1998a). However, no simple policy solutionsor technical innovations will address these diverse causes of fire, or preventdisastrous fires from recurring.

Fire, People and Pixels 467

Defining Direct and Underlying Causes of Fires

Many of the debates on appropriate action to prevent future fire dis-asters focus on the contentious problem of fixing blame for these catas-trophic fires. Problematic areas in these heated controversies highlight theimportance of distinguishing direct causes of specific fires from the underly-ing social, as well as meteorological and ecological, causes of fires. For thepurposes of this research, direct causes are human activities or immediateactions at the local level, which originate from intended fire uses, and imme-diate consequences of fire accidents related to intended fire uses, which di-rectly cause fires. They include the specific circumstances of fire ignition forspecific fire events, and immediate contributing factors to decisions aboutwhat, where, when, and how to burn, and about steps (if any) taken to con-trol specific fires. Underlying causes are driving forces, especially funda-mental social and political processes, such as land-use control institutions,investment patterns, and regional development policies, which underpin thedirect causes and either operate at supralocal level or have an indirect im-pact from the national level or broader regions (Geist and Lambin, 2002).While underlying causes unquestionably also include meteorological con-ditions, including the El Nino phenomena, as well as underlying ecologicalconditions, the focus of this study was limited to more immediately human-induced phenomena.

Vayda (1999) showed that direct causes of the fires are many andvaried. The extensive national and regional media coverage of the 1997–1998 fires and the region-wide “haze” they produced prompted increasedattention to addressing broad, underlying causes of fires and smoke. Thegovernment initially blamed the fires on the El Nino drought and small-holders’ shifting cultivation (Anon, 1997) but evidence from satellite im-agery and maps of active fires (hot spots) indicated that the most extensivefires and the greatest amounts of smoke originated from government sanc-tioned corporate plantation development, logging concessions, and large-scale land-clearing/development projects (Hoffmann et al., 1999; Potter andLee, 1998a; Stolle et al., 2003). Yet, as a fuller picture of the diversity of firesand of their wide-ranging impacts has emerged, it is clear that fires occurredat multiple scales and for many reasons, and that varying impacts on localcommunities and forest had a variety of complex underlying causes (Apple-gate et al., 2001; Bowen et al., 2000).

Remote Sensing of Indonesian Fires

Many remote sensing studies calculated the extent of the firesthrough the interpretation of active fires from NOAA AVHRR (National

468 Dennis et al.

Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration Advanced Very-HighResolution Radiometer) imagery and burn scars identified on a range ofsatellite imagery (Legg and Laumonier, 1999; Liew et al., 1998; Malingreauet al., 1985). Some studies also included supporting data on official land useto identify possible reasons for burning (Siegert and Hoffmann, 2000; Stolleet al., 2003). The burnt area estimates1 and findings of these macrolevelstudies are still much cited and there is no doubt that they were extremelyuseful in providing a timely picture and analyses of the extent of the fires.However, critics rightly point out that satellite imagery or “fire hot spots”analyzed in isolation “lack the textured understanding of social landscapesand the role they play in creating fire hazards” (Harwell, 2000), and are ofminimal use on their own in formulating policies for preventing or manag-ing fires (Robbins, 2003).

A wide range of recent research demonstrates the increasing useof remote sensing and geographic information systems (GIS) by socialand environmental scientists as tools in understanding how human deci-sions about land use, and the institutions in which they are embedded,influence rates and characteristics of land-cover change (Brondizio et al.,1994; Dennis et al., 2001; Fairhead and Leach, 1996; Mertens et al., 2000;Turner et al., 2001). Some, however, believe that quantitative methodsof spatial analysis provided by geospatial technologies, representingpositivist science, can offer little to understanding cultural landscapes(Philo et al., 1998). Others assert that those familiar with local contextswho utilize spatial technologies possess a powerful set of analytical toolsto understand culture–landscape relationships (Jiang, 2003; Turner, 2003).The literature has few examples of the integration of social science andremote sensing as applied to the cultural dimension of vegetation fires.One study of savanna burning from Mali highlights the benefits of ahybrid approach that links the results of surveys and interviews with burnscar analysis of Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) imagery (Laris, 2002).This study showed that developing a nuanced understanding of the localdynamics of large-scale phenomena with social and ecological implica-tions of global as well as regional importance demands such a “hybrid”approach.

Joining Techniques in Fire Research and Policy

Developing effective means to prevent future fire disasters in Indone-sia requires overviews of fire dynamics and landscape impacts based on

1These estimates are not complete in their geographical scope and are not easily comparableas different interpretation techniques and imagery were used in the individual studies.

Fire, People and Pixels 469

analysis of the “big picture” in terms of changing landscape and climate,and of macrolevel social, political, and economic considerations. Combin-ing these with information defining important local parameters of changeand identifying rationales underpinning the human actions that have largelybrought about these changes locally will help develop the insights necessaryto understand complex causal relationships and complex and varied chainsof impacts.

Despite an emerging consensus on the macrolevel causes and impactsof the “fire problem” there is still a lack of published in-depth empiricalevidence on the underlying causes and impacts (Barber and Schweithelm,2000; Harwell, 2000; Potter and Lee, 1998a). The multidisciplinaryapproach we developed for our research and analysis integrates remotesensing and geospatial technology with social research and rural assessmentmethods, including participatory mapping at a landscape scale (usually aregion of between 50,000 ha and 2,50,000 ha) encompassing up to severaldozen settlements and considerable ecological variation. These methodsallowed us to develop relatively detailed histories of fire impacts and oflandscape transformation in several areas, and more general information atthe regional and island scale covering at least the periods before and afterthe 1997–1998 fires in all areas, and periods back to the late 1970s in somelocations. We aimed to answer questions about the varied characteristicsof fires associated with their locations, perpetrators, reasons for burning,and reasons for fire outcomes. This would allow us to identify patternsto classify the diversity of fires in Kalimantan and Sumatra, and wouldsupport practical means and policy development to prevent future firedisasters

STUDY AREA

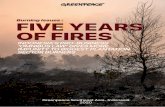

We selected four study sites in Sumatra and four sites in Kalimantan(Indonesian Borneo) with different historical land-use patterns, whichexperienced different types of fires in the late 1990s, and which represent adiverse range of fire impacts on communities, landscapes, and ecosystems.Figure 1 shows study site locations and Table I summarizes the sitecharacteristics. For further details refer to the individual site reports2

(Colfer et al., 2000; Dennis et al., 2000a; Dennis et al., 2000b; Mayer andSuratmoko, 2000; Mayer et al., 2000; Suyanto, 2000; Suyanto et al., 2000a,b;Suyanto and Ruchiat, 2000; Suyanto et al., 2000c,d).

2Site reports are available for download at http://www.cifor.cgiar.org/fire-project/index.htm.

470 Dennis et al.T

able

I.Si

teC

hara

cter

isti

cs

Phy

sica

lSa

telli

teim

age

Rem

ote

sens

ing

Site

Site

(ha)

land

scap

eL

and-

use

tim

ese

ries

anal

ysis

leve

l

Site

1(S

ekin

cau)

51,6

10M

ount

aino

usSm

allh

olde

rco

ffee

:Buk

itB

aris

anSe

lata

nN

atio

nal

Par

k:ill

egal

logg

ing

1985

–199

4–19

97L

ands

atM

SS,T

MSi

te/la

ndsc

ape–

full

imag

esc

ene-

regi

onal

fire

hots

pot

Site

2a(M

engg

ala

pene

plai

ns)

72,5

24P

enep

lain

sE

x-lo

ggin

gco

nces

sion

:co

rpor

ate

tim

ber

plan

tati

ons:

tran

smig

rati

onpr

ojec

t

1984

–199

91L

ands

atM

SS,T

MSi

te/la

ndsc

ape-

regi

onal

fire

hots

pot

Site

2b(M

engg

ala

swam

ps)

79,7

32Sw

amps

Cor

pora

teoi

lpal

mpl

anta

tion

s:tr

ansm

igra

tion

proj

ect:

trad

itio

nals

wam

pri

cefa

rmin

g

1984

–199

9L

ands

atM

SS,T

MSi

te/la

ndsc

ape-

regi

onal

fire

hots

pot

Site

3(M

usiB

anyu

Asi

n)25

3,40

1C

oast

alsw

amps

Log

ging

conc

es-

sion

:tran

smig

rati

onsc

hem

e:ill

egal

logg

ing:

fishi

ng

1986

–199

2–19

98L

ands

atM

SS,T

MSi

te/la

ndsc

ape-

full

imag

esc

ene-

regi

onal

fire

hots

pot

Site

4(T

anah

Tum

buh)

129,

200

Low

-lyi

ngpl

ains

and

upla

nds

Ex-

logg

ing

conc

essi

on:

corp

orat

e:sm

allh

olde

rru

bber

agro

fore

stry

and

field

crop

s

No

imag

ean

alys

isN

oim

age

anal

ysis

Site

5(D

anau

Sent

arum

)19

7,00

0P

eats

wam

pfo

rest

san

dup

land

sD

anau

Sent

arum

Nat

iona

lP

ark:

fishi

ng:i

ndig

enou

ssh

ifti

ngcu

ltiv

atio

nan

dag

rofo

rest

ry

1973

–199

0–19

97L

ands

atM

SS,

TM

/SP

OT

XS

Site

/land

scap

e-re

gion

alfir

eho

tspo

t

Site

6(S

angg

au)

211,

808

Upl

ands

:pla

ins

Indi

geno

ussh

ifti

ngcu

ltiv

atio

nan

dag

rofo

rest

ry:c

orpo

rate

oilp

alm

and

tim

ber

plan

tati

ons:

tran

smig

rati

onpr

ojec

ts

1991

–200

0L

ands

atT

MSi

te/la

ndsc

ape-

regi

onal

fire

hots

pot

Fire, People and Pixels 471

Tab

leI.

Con

tinu

ed

Phy

sica

lSa

telli

teim

age

Rem

ote

sens

ing

Site

Site

(ha)

land

scap

eL

and-

use

tim

ese

ries

anal

ysis

leve

l

Site

7(T

umba

ngT

iti)

871,

6162

Upl

ands

:pla

ins:

peat

swam

pfo

rest

sIn

dige

nous

shif

ting

cult

ivat

ion

and

agro

fore

stry

:cor

pora

teoi

lpal

man

dti

mbe

rpl

anta

tion

s

1989

–199

6–19

98L

ands

atT

M,

ER

SSA

R3

Ful

lim

age

scen

e-re

gion

alfir

eho

tspo

t

Site

8(L

ong

Sega

r)21

8,30

5U

plan

ds:r

iver

ine

Ex-

logg

ing

conc

essi

ons:

corp

orat

eoi

lpal

man

dti

mbe

rpl

anta

tion

s:tr

ansm

igra

tion

spr

ojec

t:In

dige

nous

shif

ting

cult

ivat

ion

and

agro

fore

stry

1983

–199

0–19

98–

2000

Lan

dsat

MSS

,TM

4

Site

/land

scap

e-re

gion

alfir

eho

tspo

t

1 Hal

fofS

ite

2a(3

8,91

3ha

)is

cove

red

byti

me

seri

es19

84–1

986–

1994

–199

9.2 Im

age

anal

ysis

carr

ied

outa

tthe

TM

imag

ele

veln

otat

land

scap

e.T

raje

ctor

yof

chan

gean

alys

isno

tcar

ried

outd

ueto

poor

qual

ity

imag

ery.

3 SAR

—Sy

nthe

tic

Ape

ture

Rad

aron

boar

dth

eE

urop

ean

Spac

eA

genc

ySa

telli

te(E

RS-

1)4 O

rigi

nals

ite

stud

y19

90–1

998,

(Col

fer

etal

.,20

00),

exte

nded

wit

hth

eye

ars

1983

and

2000

inan

extg

ensi

onof

the

stud

yD

enni

san

dC

olfe

r(I

npr

ess)

.

472 Dennis et al.

Fig. 1. Location of research sites.

METHODS

We combined fine-scale remote sensing data (Landsat TM and/orSPOT Multispectral (XS)) and hot spots (active fires) data (from NOAAAVHRR) with detailed information from interviews, participatory sketchmapping, and baseline information for a select number of locations, usuallyrepresenting a subset of villages, resource concession areas, or designatedconservation areas within the larger site.

Site Selection Procedure

We delineated study site boundaries based on a combination ofjurisdictional, ecological, and remote sensing factors. The sites were notselected to document causes of the most extensive fires of the late 1990s,or the fires that generated the most smoke, nor were they chosen to heapdetailed blame on “the usual suspects.” Due to the importance to this studyof information drawn from interviews and narratives concerning sensitivetopics related to fire, and on land-use mapping by members of localcommunities, our selection of sites prioritized locales where we believedcredible information would be available from research partners. In manycases, for subareas within the sites, detailed fire-related information was

Fire, People and Pixels 473

Fig. 2. Musi Banyu Asin (MUBA) landscape-scale sketch map. Width of map approximately60 km.

available from official sources, previous research, and local knowledgegained through Nongovernmental Organizations (NGO) activities.

Social and Ethnographic Research

We employed social research methods aimed at documenting specificfire events in particular locations, as well as understanding the extent towhich the causes of fires are influenced by land-use policies and practicesfrom the village level through regional authorities and the central govern-ment, from household resource and fire-use decisions through transnationalinvestments. Ethnographic methods intended to construct a picture of re-lationships among land users, land managers, and fire in each of the sitesincluded household surveys, group and individual interviews, participatorysketch mapping and field surveys, and a range of rural appraisal exercises.In Sekincau, Danau Sentarum, Sanggau, Tumbang Titi and Long Segar,researchers undertook village level analysis in addition to landscape levelanalysis. In most of the sites, local NGOs assisted with the social surveys.Representatives of a broad range of stakeholders were interviewed includ-ing various groups within local communities, government officials, and largelandholders or concession holders.

Members of local communities were usually interviewed in theirhomes, at homes of village leaders, or in village meeting halls. In a typicalvillage interview situation, core researchers and regional NGO researchpartners invited formal and informal leaders to attend a number of meet-ings where discussion included explanations of the research purposes,

474 Dennis et al.

consultations on research methods, general information about the village,land and resource uses, and settlement history. Further discussion includedspecific issues related to fires, such as the village’s resource use and firehistory, resource management concerns, and conflicts or controversies withneighbors or within the village with implications for fire causes or impacts.Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) techniques, such as participatory sketchmapping were used (see Fig. 2). In several sites, sketch maps previouslyproduced through collaborations with regional NGOs or other researchefforts were used as a base for discussions. Ensuing discussions referringto these maps elicited detailed information about specific fire events, in-cluding fire locations, dates and duration, specific details about fire ignitionincluding identities of fire starters and reasons for burning, burning or firemanagement practices employed, direction of fire movement, and localnarrators’ hypotheses about fire origins, as well as their assessments of firecauses and results. Drafting and discussions of sketch maps were followedby field surveys with village members to map locations of fire events andresources of particular concern to this study using a hand-held globalpositioning system (GPS). The sketch maps also identified areas of conflict,often where customary land or resource use boundaries overlapped withofficial land-use designations.

Government officials were usually interviewed in their offices aboutlocations of major fires and official assessments of causes, fire preventionactivities by government agencies, and fire suppression capacity. Officialsalso provided researchers with maps of fire-related and resource industry-related information, as well as documents related to fire prevention orfire suppression policies. Because this research was conducted in the earlyphases of reform-era “regional autonomy” experiments, many of theregional officials interviewed were new to their positions, and many keydecision makers of 1997–1998 were unavailable, or unwilling to commenton government positions, capabilities, and activities of that time.

Large landholders or managers of companies holding plantation or log-ging concessions were usually interviewed in site offices or company re-gional headquarters. Researchers had ostensibly free access to most com-pany sites. However, some companies effectively limited researchers’ accessto their working areas.

Spatial Data Analysis

Secondary spatial data and remotely sensed imagery were collectedfor the sites. These data included topographic maps,3 administrative

3Available from the national mapping agency (BAKOSURTANAL) at a scale of 1:50,000 or1:250,000.

Fire, People and Pixels 475

boundaries,4 land/forest cover,5 land/forest use status,6 and official spatialplanning boundaries.7 Multitemporal series of remotely sensed imagerywere also collected and included Landsat TM, Landsat Multi SpectralScanner (MSS), SPOT XS, and in one instance Synthetic Aperture Radarimagery. In general, these image datasets covered two to three dates fromthe mid-1980s to the late 1990s, including one date after the 1997–1998fires (see Table I). We also extracted active fire locations from lowerresolution NOAA AVHRR imagery to provide a general fire history andfire frequency for each site, and for Sumatra and Kalimantan as a whole(Stolle, 2000). For a discussion on the accuracy hotspots refer to Stolle(2000). In addition, processed “hot spots” were also kindly provided by anumber of bilateral forest fire projects.8 Aerial observations were carriedout in 1999 over three of the sites producing high-resolution geo-locateddigital photography.

Remote sensing (image processing) and spatial analysis techniqueswere used to classify and analyze the historic and current patterns of landcover and burn scars for each site (Lachowski and Maus, 1995). We used PCER Mapper for image processing and ESRI PC ArcView and image classifi-cation and spatial analyses. Imagery was geometrically corrected and spec-trally contrast enhanced and various band combinations assessed so thatcolors that appeared on our working satellite prints would make intuitivevisual sense to social scientists working in the field.

We classified the image sets for each site by on-screen digitizing ofdigital imagery (Achard et al., 2002; Boehm and Siegert, 2001; Dennisand Kurniawan, 2000; Siegert et al., 2001a). For each site, the land coveron the oldest image was classified first and then this classification servedas a template to update land cover from the images of subsequent dates.

4We preferred to use the most locally available source, which was usually from the provincialplanning agency (Bappeda).

5Variety of sources using differing definitions and classification schemes: Regional PhysicalPlanning Programme for Transmigration (RePPProT, 1990) a nation-wide thematic mappingexercise showing land-cover situation in the mid-1980s at 1:250,000 scale, World ConservationMonitoring Centre (1996) modified the RePPProT dataset and made it available on CD; Na-tional Forest Inventory (FAO/Ministry of Forestry) showing forest cover for the mid-1990sat a scale of 1:250,000; Forest/Non-Forest (Ministry of Forestry/World Bank) for the mid-late1990s available in digital form only (Holmes 2000). For a discussion of these data sources seeFWI/GFW (2002).

6Better known as the “agreed forest land-use categories” (TGHK – Tata Guna Hutan Kesep-akatan) originally mapped at 1:500,000 scale and published in 1985 (Potter, 1990).

7RTRWP (Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Propinsi) spatial planning maps produced by provin-cial planning agency (Bappeda) and available at a scale of 1:250,000 published in the latterhalf of the 1990s.

8Japanese International Co-operation Agency (JICA)—Indonesian Ministry of Forestry(MoF) Forest Fire Protection and Management Project (FFPMP), Bogor, Indonesia; Euro-pean Union – MoF Forest Fire Prevention and Control Project (FFPCP), Palembang, Suma-tra; German Technical Assistance (GTZ) – MoF Integrated Forest Fire Management Project,Samarinda, East Kalimantan.

476 Dennis et al.

A standard two-level land-cover/land-use classification scheme was used.First level classes were: natural forest, scrub/grass, plantation, agriculture,settlement, recent burn scars,9 and water bodies. The second level includeddensity of forest cover, type of plantations, and type of crops.

It is normal practice to provide an estimate of image classification ac-curacy by comparing it with the actual land-cover types on the ground atthe time (Congalton, 1991). However, all of the satellite imagery used inthis study was historical and it was thus not feasible to check its accuracy onthe ground. As a proxy for conventional accuracy the most recent classifi-cations were checked in the field by researchers accompanied by membersof local communities.

Cumulative area estimates were determined for each image classifica-tion and “trajectories” of land-cover change were calculated by creating a“from” and “to” matrix of land-cover change between two successive dates.Although these calculations did not provide conclusive indications of thespecific causes of changes in the landscape, they did enumerate changes thatmight be attributable to fire with further analysis, and provided evidenceto characterize landscape change between pre-fire and post-fire periods ata scale that would be impossible based on “grounded” social and ecolog-ical survey methods alone. These calculations also helped ensure that thesmaller areas within each site selected for more detailed study did not rep-resent extremely unusual cases of landscape change within each landscapescale study site.

Integrating Social and Remote Sensing Data

The final stage in the analyses was to integrate the image classifica-tions, burn scar locations, and active fire distributions with the results fromthe interviews, social surveys, participatory mapping, and information fromprevious research and secondary sources. This informed our understandingof the occurrence and apparent causes and impacts of fire to landscape andpeople within each site, and for specific smaller areas within it.

Paper sketch maps produced through participatory mapping exercisesand modified by GPS in the field, were scanned and input to the GIS. Thesedigital maps were then overlaid with the land cover/use, burn scars, and

9There are two quite different post-fire signals: the deposition of charcoal (char), and the al-teration of vegetation structure and abundance, commonly called a burn scar (Pereira et al.,1997). Recent burns have a high composition of charred material and a spectral reflectancethat is very distinct from living vegetation. This signal is relatively short-lived and tends to bealmost completely erased by wind and rainfall in a few weeks or months after the fire. Thesecond signal is more stable. Over time the spectral reflectance of the burn scar changes, aspioneer and eventually secondary vegetation grows back.

Fire, People and Pixels 477

active fire locations generated by satellite image analysis. Using the result-ing data layers, we could identify boundary overlaps between different landusers, such as areas claimed by local people under customary rights andplantation companies or other officially designated land uses. Estimatesof how much land had been burned and suggestions of why were basedroughly on the digitized sketch maps and on interviews for each site at thelandscape level. In many cases, narratives and comments by local residentsand others indicated specific details about particular fire events, includ-ing clear indications of both their immediate causes and immediate resultsand in some cases assertions concerning what we have termed underlyingcauses. Within the GIS it was possible to identify these burned areas moreprecisely on the satellite image-derived land-cover maps and calculate theformer land cover and the exact size of the burn scar, and thus approxi-mately the area burned in each period for which data were available.

This approach provides a rich record of where and when fires haveoccurred, how extensive they have been, and resulting changes in land coverand land uses. It indicates causes and impacts of specific fire events and thescope and characteristics of the “fire problem” in general, both as perceivedby the people most directly familiar with and most directly affected by fires,and through larger-scale, more generalized remote sensing perspectives.

RESULTS

Direct Causes

The study found that there were a number of direct causes of fire onany one site with the four main direct causes of fire, in order of frequencyas: fire used as a tool in land clearing; accidental or escaped fires; fire usedas a weapon in land tenure or land-use disputes; and fire connected withresource extraction. In over half of the sites, burning practices to clear landfor short rotation swidden were a frequent cause of fires, with burning con-ducted mainly by smallholders, including longstanding or indigenous popu-lations and recent migrants (Table II). Similarly, over half of the sites pro-vided examples of large landholders using fire as a tool in land clearing forgovernment licensed plantations or transmigration sites, in spite of the cen-tral government’s 1995 prohibition on commercial burning (Colfer et al.,2000; Mayer and Suratmoko, 2000; Suyanto and Ruchiat, 2000; Suyantoet al., 2000c,d).

The Musi Banyu Asin (MUBA) site clearly shows the sequence fromburning to establishment of a transmigration site (Fig. 3). The trajectoryof land-cover change analysis, for the same site shows that between 1986

478 Dennis et al.

and 1992, 44% (12,690 ha) of land classified as recently burned in 1986 hadbeen developed for transmigration by 1992, with a further 5,532 ha of landcleared by fire for transmigration between 1992 and 1998.

In many of the sites, fires set to clear limited areas of land forplantations of smallholder coffee (Sekincau), oil palm (Menggala, TanahTumbuh, Sanggau) or illegal logging (Sekincau) escaped into adjacentopen access forest land or young timber plantations. In most cases, theescaped fires spread extensively due to the lack of incentives for peopleto effectively control fire that was not on their own land. This is clearlyseen in Sekincau, where both recent migrants and long-term residentsare establishing coffee gardens on a forest frontier previously degradedby illegal logging. The long-term land-cover change trends (Fig. 4) showforests being replaced by coffee gardens or burn scars, with 91% (25,972ha) of forest cover converted to coffee gardens and 9% appearing as recentburn scars between 1985 and 1994. Some of these fires were intentional,but many burned beyond the limited areas intended by the people who set

Table II. Direct Causes of Fire Listed by Site [Adapted from Applegate et al. (2000)]

Sumatra Kalimantan

Direct causes of vegetation fires 1 2A 2B 3 4 5 6 7 8

Fires as a tool in land clearingSmall holders (indigenous

people, migrants)Conversion of forests to

√ √alternative land uses(e.g. to coffee or rubber)Rotational tree cropping

√ √ √Short rotation swidden

√ √ √ √ √ √Large landholders (companies)

Large-scale plantation√ √ √ √ √ √

developmentTransmigration sites

√ √ √ √Fire as weapon in land tenure/use disputes

Arson√ √ √ √ √ √ √

Accidental fires (Escaped)Land clearing/illegal logging

√ √ √ √ √ √ √Cooking/smoking/camping

√ √ √ √Fire connected with resource extraction

Improve fishing areas/√ √ √ √

search for fish andturtles/access tracksfor boats/deer hunting

Site 1= Sekincau (Sumatra); Site 2a = Menggala peneplains (Sumatra); Site 2b = Menggalaswamps (Sumatra): Site 3 = Musi Banyu Asin (Sumatra); Site 4 = Tanah Tumbuh (Sumatra);Site 5 = Danau Sentarum (Kalimantan); Site 6 = Sanggau (Kalimantan); Site 7 = TumbangTiti (Kalimantan); Site 8 = Long Segar (Kalimantan).

Fire, People and Pixels 479

Fig. 3. Musi Banyu Asin (MUBA)-Landsat image time series 1986–1992–1998. Band displaycombinations are 421 (MSS) and 457 (TM). Red (MSS) and orange (TM) tones indicate veg-etation cover, with paler shades representing sparser cover. Pale green tones (MSS) indicatecleared lane, and cyan tones (TM) indicate recent burns. Water is cyan (MSS) and black(TM).

them. The more extensive “accidentally” burned areas are later plantedwith smallholders’ coffee as well (Suyanto, 2000).

Fire used as a weapon in conflicting or overlapping land use or tenureclaims was clearly found in seven of the nine sites. Deliberately set fireswere reported to be prevalent in many areas rich in commercially valuableresources where land for agricultural production is either becoming scarceand/or where conflicts over resource tenure or resource access and uses oc-cur, or have occurred in the recent past. These types of fire were particularlyimportant in areas with remaining natural forest on fertile soils, and areaswhere large landholders have obtained land concessions from central or re-gional governments for oil palm and timber plantations. This scenario isparticularly well exemplified in the peneplains of Menggala (Site 2a) wherelocal farmers used fire to claim back land from a plantation company in1998. The conflict area is highlighted in Fig. 5 (Zone 3) by the presence of

480 Dennis et al.

Fig. 4. Cumulative land-cover change estimates for Sites 1, 2a, 2b, and 3, based on satelliteimage classification for individual years.

a large irregular shaped burn scar within the plantation boundary. Similarfires were also set by smallholders to reclaim land for their own use that hadbeen previously cleared and planted by government-approved concession-holders in the Sanggau and Tanah Tumbuh sites.

Some of the findings most difficult to interpret were cases where lo-cal informants asserted that fires that eventually spread to extensive areaswithin official concessions, and sometimes beyond, had been deliberatelyset by agents of companies holding plantation development concessions inorder to eliminate land claims by local communities. Similar findings alsocome from a study in East Kalimantan where local residents reported thatfires were deliberately set by oil palm company workers specifically to burnthe forest gardens of communities adjacent to the plantation in order to re-duce the company’s financial compensation liability (Gonner, 1999). Thesefires could be counted as arson, and thus as weapons in resource conflict, oras agricultural land clearing.

On four of the eight sites, we were told that nearby residents and sea-sonal migrants set fires to facilitate small-scale, seasonal resource extrac-tion, including fishing and deer and turtle hunting. In some cases, these ac-tivities specifically took advantage of improved access to dried-out swampsduring drought periods. In 1997, the burning of 60,172 ha of degradedswamp forest in the MUBA site was attributed by local informants partly tofires associated with fishing activities, where it is used to clear undergrowth

Fire, People and Pixels 481

Fig. 5. Burn scar patterns in the Menggala peneplains site, Sumatra. Background imageLandsat ETM September 1999 displayed in 4, 5, 7 band combination: cyan – bare fields,orange – corporate plantation tree crop, pink – recent burn scars. Zone 1 – escapedswamp fires; Zone 2 – deliberate clearings clearing by company; Zone 3 – land conflictfires; Zone 4 – land conflict fires; Zone 5 – Land conflict fires; Zone 6 – escaped swampfires.

for ease of access to small pools rich in fish and sometimes turtles, and incampfires used for cooking the catch. Smaller uncontrolled fires associatedwith fishing and turtle hunting were also reported by local informants inDanau Sentarum and Long Segar in 1997 (Colfer et al., 2000; Dennis et al.,2000a). An earlier study of the use of fires in resource extraction in theDanau Sentarum area found anecdotal evidence of burning swamp forestto facilitate capture of a valuable ornamental fish species (Luttrell, 1994).Although it is nearly impossible to establish the burden of proof for actualignition in such cases (as discussed by Vayda, 1999), researchers in DanauSentarum found compelling evidence that a small fire in dried-out swampforest had started from a campfire that had not been properly extinguishedearly that morning.

482 Dennis et al.

Underlying Causes

This study identified six major underlying causes of fire. At each site,fire was attributed to more than one underlying cause, as summarised inTable III.

Land Tenure and Land-Use Allocation Conflicts and Competition

By far the most significant underlying cause of fire across the siteswas related to land tenure and land allocation competition and conflict(Table II). In Sekincau and Menggala in Sumatra where land was scarceor where smallholders had informal land claims when occupying nationalpark land or disputed land officially designated to other parties, competingclaimants sought solutions through the use of fire. Smallholders, includingboth longstanding local populations and newcomers, have burned naturalforest to plant a variety of crops and settle land frontier-style, or to establishor reassert claims over land that had previously been planted by timberor oil palm companies. Local communities in Menggala (Site 2a) burnedplantation land to reclaim it for their own use, and reactivate their ownclaims during a period of political turmoil in 1998. A similar pattern wasobserved in Tanah Tumbuh, where individuals used fire to prepare landfor tree planting that would secure informal recognition of their “private”property claims on lands that the community had previously consideredcommon property.

Another major issue across all sites was a classic “tragedy of thecommons”—the lack of incentives for individuals, local communities, orprivate companies to control unwanted fire on land which was not theirown, where they had no secure property rights, and where they had nosense of responsibility for land management and received few direct ben-efits from investing in fire control. Related to this are overlapping claimsand competition for land and natural resources among many stakeholdersin areas where actual development patterns are already well-defined andin some cases, in contrast to official plans and designations, such as inparts of Lampung Province, as well as Tanah Tumbuh in Jambi Province.The fire problem in these situations is often related to the lack of anaccessible, equitable, and transparent legal system to resolve disputed landand land-use claims.

Inappropriate, inequitable, and uncoordinated allocation of landby multiple government agencies and administrative levels for differentuses has resulted in various stakeholders’ burning land and forests, eitherdeliberately or by neglecting to control fires they set or discover. Boththose authorized by central or regional authorities, and those attempting

Fire, People and Pixels 483

Table III. Underlying Causes of Forest and Vegetation Fires for Sites 1–8 [Adapted fromApplegate et al. (2000)]

Sumatra Kalimantan

Underlying causes of vegetationfires

1 2a 2b 3 4 5 6 7 8

Land tenure and land use allocation conflicts and competitionLack incentives for individuals,

local communities, or privatecompanies to controlunwanted fire on land whichwas not their own, wherethey had no secure propertyrights, and where they had nosense of responsibility forland management.

√ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Overlapping claims andcompetition for land andnatural resources amongmany stakeholders in areaswhere actual developmentpatterns are already welldefined, and contrary toofficial plans anddesignations in some cases.

√ √ √ √ √ √ √

Inappropriate, inequitable anduncoordinated allocation ofland by multiple governmentagencies and administrativelevels for different uses.

√ √ √ √ √ √ √

Lack of an accessible, equitable,and transparent legal systemto resolve disputed land andland use claims.

√ √ √ √

Informal land tenure securitypromotes site occupation andforest conversion

√ √

Forest degrading practicesInappropriate timber harvesting

practices for site conditions.

√ √ √ √ √ √

Repeated fires due to increasedfire proneness of previouslyburned vegetation.

√ √ √ √ √ √ √

Drainage systems in swampsthat lower the water table dryout the peat and provideincreased access.

√ √

Economic incentives/disincentivesAnticipated high profits of

alternative uses to plantationdevelopers, both largecorporations andsmallholders of forest landfollowing logging (e.g. oilpalm, rubber, coffee, timber).

√ √ √ √ √ √ √

484 Dennis et al.

Table III. Continued

Sumatra Kalimantan

Underlying causes of vegetationfires

1 2a 2b 3 4 5 6 7 8

Perverse developmentprocesses and mechanisms.

√ √ √ √ √

Population growth and migrationLarge-scale government

sponsored and spontaneousin-migration

√ √ √ √ √ √

Lack of commitment to newlocation and careless use offire

√

Inexperience with use of fire innew environments

√

Different resource (and fire)use patterns by differentethnic groups

√ √

Inadequate fire fighting and management capacityInadequate forest and fire

management plans, andfacilities to prevent andsuppress accidental orescaped fires in plantationsand natural forests

√ √ √ √ √ √ √

Lack of institutional capacity,resources and will to monitorand deal with encroachmentand other illegal activities inprotected forest areas

√ √

Sumatra: 1 = Sekincau; 2a = Menggala peneplains; 2b = Menggala swamps; 3 = MusiBanyuasin; 4 = Tanah Tumbuh. Kalimantan: 5 = Danau Sentarum; 6 = Sanggau; 7 = Tum-bang Titi; 8 = Long Segar.

to contest government land or resource allocations have used fire to try toremove competing land occupants or resource claimants, or to eliminatehigh-quality native forests whose continuing presence would legally pre-vent certain types of land development that would require forest clearing.In some instances, central government authorities allocated the same tractof land to different users or concession-holders. In other cases, especiallyas regional authorities began exercising new perogatives under tentativemoves toward administrative devolution in the chaos toward the end of theSuharto period, central and regional authorities issued permission or rec-ognized claims for conflicting uses on the same land. For example, in TanahTumbuh, local communities contested allocation of their customary land fordevelopment of oil palm plantations in 1994. In ensuing conflicts, fire wasused as a weapon by both sides. Plantation developers burned local com-munity members’ tree crops (rubber) to reinforce their concession claims,

Fire, People and Pixels 485

Fig. 6. Cumulative land-cover change estimates for Sites 5, 6, 7, and 8, based on satellite imageclassification for individual years.

and members of local communities burned plantation crops (oil palm) anda site office. Similar instances were observed in South Sumatra and EastKalimantan by other researchers (Bompard and Guizol, 1999; Gonner,1999). Sometimes, the use of fire as a weapon is not so clear-cut. In Sang-gau, villagers contesting the rights of a timber plantation to operate withinvillage customary boundaries simply allowed a fire of undetermined originsto burn out of control through fire-prone grasslands along the village bor-der. The fire destroyed an extensive area of the company’s newly plantedtrees, while village farmers effectively protected their own rubber trees.

Forest Degrading Practices

On a number of sites with varied forest types, fire damage was exac-erbated by timber harvesting and related land practices, swamp drainage,and repeated deliberate burning as well as accidental escaped fires. Re-peated fire reduces options and possibilities for rehabilitating these forestsand creates a positive feedback loop whereby forests become more proneto repeat fire damage (Cochrane et al., 1999; Nepstad et al., 1999; Siegertet al., 2001b). In the coastal swamps of Sumatra, the MUBA site providesa good example of unsustainable logging practices and swamp drainage

486 Dennis et al.

creating an increasingly fire-prone landscape.10 In 1986, much of thehigh-density swamp forest (82,741 ha) was part of a logging concession. By1992, satellite images show that 69,526 ha were already severely degradedswamp forest, 6,898 ha had been drained and converted to transmigrationsettlements and cultivated fields, and the remainder had been burned butnot necessarily converted to other obvious use. The entire remaining forestarea (apart from some mangrove) had burned by 1998 (Fig. 4). Similarly,the Long Segar site (Site 8) shows the creation of a drier, more fire-pronelandscape since the 1970s with the conversion of closed-cover lowlandtropical forest to overlogged and degraded.11 forest followed by industrialtimber plantations, oil palm and other cash crop plantations, or transmi-gration agriculture (Colfer and Dudley, 1993) (Fig. 6). For Long Segar,the breakdown of the forest cover change estimates between 1983 and2000, shows the degradation of 44,061 ha12 of closed-cover lowland forest,all within logging concessions, to secondary forest (20%), fragmented/firedamaged forest (21%) and sparse trees/scrub (45%), the remainder beingplantations and agriculture Dennis and Colfer (In press). Repeated firesover an extended history in Sanggau and Tumbang Titi have also led toadvanced stages of land degradation characterized by large swathes offire-prone grasslands ( Imperata). Similarly, in the Sanggau site, 42% of the31,552 ha of lowland forest that existed in 1991 had been altered by officiallysponsored logging, timber and oil palm plantations, indigenous cultivation,and fire to a mosaic of cultivation and Imperata grasslands by 1998 (Fig. 6).

Economic Incentives/Disincentives

The anticipated high profits to both large corporations and smallhold-ers of alternative uses of forest land following logging, in many cases de-pending on subsequent burning, is a major driving force for deforestation(FWI/GFW, 2002; Holmes, 2000; Tomich and Lewis, 2001; Tomich et al.,1998b, 2001). In seven sites, the transition from logged (both legally and il-legally) forests to large corporate, or smallholder plantations is exemplifiedby the trends we see in Sekincau and Menggala (Fig. 4) and Sanggau andLong Segar (Fig. 6). Although official Indonesian land-conversion policies

10Although there is some debate about how “fire-prone” landscapes are formed, for the pur-poses of this study we use the following definition: a landscape where fires are more likely tooccur and spread than they would under previous conditions.

11Forest degradation can be defined as a “temporary or permanent deterioration in the densityor structure of vegetation cover or its species composition” (Grainger, 1993).

12Trajectory of change estimates for only those pixels which are not in cloud in any one of theyears.

Fire, People and Pixels 487

of the 1990s limited clear-felling of forests for plantation development to al-ready “degraded” forests, policy analysts have long asserted that many tim-ber companies seeking to maximize profits deliberately “degraded” forestswithin their concessions in order to ensure permission to clear-fell later,or subsequently converting their selective logging concessions to industrialtimber or oil palm plantations(Potter and Lee, 1998a,b; Telapak Indonesia,2000).13

Satellite image classifications overlain with maps of plantation conces-sion boundaries also highlighted that not all land where forests had beenclear-felled for plantations (much of which was also subsequently burned)was actually planted in plantation crops. In many sites, scrub and grasslandor burn scars later covered a very high proportion of the deforested land.For example, in the Menggala peneplains, of the 54,060 ha of forest clearedwithin designated plantation concession boundaries between 1984 and 1999only 51% were actual plantations in 1999, 10% was scrub and grassland,30% was transmigration settlement areas, and 7% appeared as burn scar(Fig. 4). We could perhaps conclude here that the aim in these cases wasto obtain the timber with little future interest in developing the land forplantations, as similarly concluded by Potter and Lee (1998a).

Population Growth and Migration

Many areas, in Sumatra and Kalimantan (including extensive areaswithin the sites of Sekincau, Menggala, MUBA, Tumbang Titi, and LongSegar) were subjected to large-scale government sponsored in-migrationassociated with Indonesia’s Transmigration program (Down to Earth,2001).14 Migrants, local land-clearing contractors, and original local custom-ary property, owners intending to turn land over to projects, burned forestsand other vegetation to prepare land for new settlements. Such burning was

13A Minister of Forestry and Estate Crops decree (No. 376/Kpts-II/1998) on the “Criteria forthe Allocation of Forest Land and Oil Palm Estates,” according to Potter and Lee (1998)covered the following; “In addition to specifying site criteria for new oil-palm plantationsthe decree said estates in the forest zone would be steered towards land that was open ratherthan vegetated, not owned by any party and that was classified as suitable for agriculture inthe provincial land use plans.” Potter and Lee go on to state “. . . since the announcement ofthe decree there has been no evidence that it has operated to limit the spread of oil-palmestates into forested areas.”

14The original goal of the Transmigration policy was to resettle millions of people from thedensely populated islands of Java, Bali, and Madura, to the less densely settled outer islandssuch as Kalimantan and Sumatra and provide land and new opportunities for the poor mi-grants. This goal was later superseded by an explicit aim to “develop” the Outer Islands. Asdescribed by Barber and Schweithelm (2000) based on the Government of Indonesia SixthFive-Year Development Plan, “Between 1969 and 1993, the program “opened” 1.7 millionha of agricultural and resettled some 8 million people.”

488 Dennis et al.

legal prior to 1995, and afterward openly practiced despite official prohibi-tions. Often migrants, coming mainly from Java and other areas where agri-cultural burning is not customary practice, were unfamiliar with the precau-tions traditionally used for small-scale agricultural burning in Sumatra andKalimantan often resulting in fires escaping into very fire prone environ-ments (Colfer et al., 2000). In other cases, migrants brought their own landuse patterns and fire practices with them, which may have involved burningon a smaller scale or at a different time of the year than was appropriatefor their new environment, making fire control more difficult. This under-lying cause of fire is of moderate importance and is less likely to be an issuein densely populated regions than where rapid inmigration and frontier-style development is under way, with new migrants arriving from distantand dissimilar areas, and forests being cleared for agriculture. In addition,officially sponsored transmigration to Kalimantan and Sumatra has virtu-ally ended, with the exception of resettlement of refugees from disastersand civil violence.

Inadequate Fire Fighting and Management Capacity

Lack of institutional capacity for fire management was apparent in allsites. In many cases, fires deliberately set to assist with land clearing, whichburned beyond their intended area into forested areas of commercial oreconomic value, could not be suppressed due to lack of capacity in terms ofmanagement planning for prevention and suppression. This was evident inboth natural forests and timber plantations. This situation is less likely to bea major problem in the future as many plantation companies are developingthe institutional capacity to manage fire on their concessions—now requiredunder recent national land and forest management reforms. In contrast tolarge-scale plantation companies, there is a growing body of evidence re-garding local capacity to manage fire and prevent its spread among estab-lished smallholder communities (Byron, 2004). Moreover, experience fromThailand shows the feasibility of strengthening community level capacity tomanage fire (Hoare, 2004). However, institutional capacity is likely to con-tinue to be a major issue in protected areas where the human, financial, andlaw enforcement resources are not available and customary tenure systemsand other local institutions have been disrupted.

Burn Scar Typology

Through the mapping and social interpretation of burn scars in each ofthe sites patterns of burn scar typology emerge that may also be extended to

Fire, People and Pixels 489

support a more general typology of fire causes and effects. We found thatsmall regular burn boundaries are often found in areas of smallholder orswidden cultivation; whereas medium–large irregular burns on the periph-ery of, or just inside corporate plantations suggest areas of conflict betweenland users, such as in the Menggala peneplains (see Fig. 5, Zone 3, 4, and5). Regular, large burns within plantation boundaries are most likely to in-dicate deliberate fires authorised by the plantation company (Fig. 5, Zone2). We could identify where fires had escaped (accidentally) into planta-tion areas by the juxtaposition of fire prone areas (e.g., dry swamps) andplantations (Fig. 5, Zones 6 and 1). In swamp areas, large irregular burnscars in open access natural forest areas that had burned during El Ninoyears were often associated with small-scale natural resource extraction,such as turtle hunting (also described by Jepson et al. (1998) and Vayda(1999) in East Kalimantan). Further rigorous testing is required beforewe can confidently extrapolate beyond the immediate research site bound-aries to provide a definitive or predictive link between burn scar typologyand cause/perpetrator for Sumatra and Kalimantan. This could provide apowerful policy tool at a wider scale where detailed socioeconomic surveysare not feasible.

DISCUSSION

Research implications focus on the three main outcomes of this re-search: the methodology it demonstrates, the underlying causes and impactsof vegetation fires, and the policy implications of our findings.

Linking Fire, People, and Pixels

The relationship between remote sensing and social science proved tobe extremely positive in this research. Spatial analysis techniques largelyanswer the questions about what burned and where, at multiple scales ofanalysis. Linking these analyses with social investigations “on the ground”answered questions about who burned what, as well as why and how peopleand communities experienced impacts of fire. The remote sensing productsprovided precise place-specific information on historic and recent patternsof fires and their impacts on vegetation. This provided important guidanceto direct and focus social research on the ground that in turn enabled usto draw conclusions about causal processes underlying landscape trans-formation associated with fire and burning, and understand the humandimensions of the land-cover change seen on remotely sensed imagery.Participatory mapping proved to be a powerful means of linking land-cover

490 Dennis et al.

classifications based on satellite imagery with information from interviewsand narratives provided by people with direct experience of fires. Byoverlaying the participatory village and landscape land-use maps with theland-cover classifications, we could identify the origins and social signifi-cance of the changes so clearly outlined in the remotely sensed imagery.Likewise, the improved explanatory power of combining landscape-scaleremote sensing analysis with data obtained through ethnographic and rapidrural assessment methods, along with secondary data sources, impressedresearchers initially focusing on the social and institutional dynamics of firecauses and impacts.

Underlying Causes and Policy Implications

The study shows that multiple direct and underlying causes are ap-parent in each of the eight sites. Important findings include the indicationthat fire causes at each site differ widely and are complex and diverse,and the lack of a clearly dominant single cause of fire at any of the sites.This complexity is understandable within the context of multiple stakehold-ers and land-use activities on the sites. The results strongly indicate thateffective approaches to preventing and managing fire, and to solving, orlessening fire problems must be multifaceted, and must target specifics ofcomplex fire causes in particular regions and localities (Tomich and Lewis,2002).

We believe that complex sets of causes underlying recent seriousfires probably characterize fire problems in most parts of western In-donesia. Potter and Lee (1998a) arrive at a similar conclusion in theirstudy of the oil palm plantations: “. . . in each case quite complicated,with a number of active participants involved and contributing to theburning.” Similarly, in a comparative study of the proximate and un-derlying driving forces of deforestation, Geist and Lambin (2002) foundmany and varied causal factors revealing no single dominant cause–effectpattern.

Although the results of this study do not belittle the importance ofmacrostructural causes of Indonesia’s recent fire crises, they do contradictassertions that originate from a wide range of political standpoints insist-ing that solutions will be found almost entirely in national policy reformsbroadly aimed at structures of centralized land allocation, developmental-ist regional investment policies, inequitable imperatives toward global com-modity exports, cronyism, and corruption. They also belie the research-related corollary of such assertions: that detailed research on specific causesand impacts of particular fires is not necessary or is superfluous, from apolicy perspective, and that such particular research may actually serve to

Fire, People and Pixels 491

obscure the most significant fire causes and reduce pressure for necessarystructural reforms (compare Byron, 2004; Gellert, 1998).

Based on the identification of both direct and indirect causes andimpacts of fire in this research, we have outlined some policy issues andimplications of this research for the regions studied, and by extension forIndonesia. The policy implications we note in the following analyses high-light the value of the hybrid methods developed in this study. Two crucialsets of policy issues relate to (a) the need to reduce the use of fire as a toolin land clearing, and to reduce fire risks where burning continues; and (b)the need to resolve problems relating to land-use allocations and tenure,which result in widespread uncontrolled fires. Additional policy reformsand their effective implementation are required to reduce forest degradingpractices and population pressures that result in increased burning, and tobuild economic incentives and disincentives as well as legal, administrative,and other institutional capacity to promote more sustainable uses of landand management of fire.

Reducing the Use of Fire as a Land-Clearing Tool, and Reducing RisksWhere Fire Burning Continues

The central government’s current official zero-burning policy, if ef-fectively enforced by Provincial governments, could directly reduce thefire problem. However, many land development and plantation companiesclaim that preparing land for plantation crops without burning, while tech-nically feasible, remains impractical and uncompetitive under Indonesia’scurrent structure of fiscal incentives and lack of meaningful penalties forillegal burning (Simorangkir and Sumatri, 2002). Conversely, the expan-sion and expectations of reasonable profits by several oil palm and timberplantations by companies in Indonesia and Malaysia that have consistentlyused zero-burn techniques calls such assertions into question (Guyon andSimorangkir, 2002; Simorangkir et al., 2002).15

Some policy analysts suggest that some land clearing with fire shouldbe allowed, under limited, relatively low-risk conditions, and only with ap-propriate safeguards (Byron, 2004; Tomich and Lewis, 2002). To implement

15These include companies operating in or adjacent to study sites for this research—FinnantaraIntiga timber plantation in Sanggau, and the Golden Hope oil palm plantation near TumbangTiti in Ketapang. Golden Hope’s “no burn” practices have guided the standard now requiredby law in Malaysia. Simorangkir et al. (2003) conclude “Generally zero-burning methods arenot more expensive than burning, especially when replanting oil palms or rubber trees, orclearing low secondary vegetation or heavily logged-over forests. Burning is more economi-cal for clearing high-volume forest . . . In the long term . . . zero burning will actually be morecost effective mainly due to lower fertilization costs, pay off of fire management system, andlower socioeconomic costs of fire damages” (p. 34).

492 Dennis et al.

such a policy, practical and accurate early warning mechanisms for high-firerisk conditions would be required for land managers to make prudent deci-sions about when, where, and how to burn, and to prepare appropriate andsufficient workforce, expertise, equipment and infrastructure to suppressescaped fires. In addition, more research is needed into alternative meth-ods of land preparation and management that either require no burningor generate less smoke (Murdiyarso et al., 2004). This is especially press-ing with regard to developing peat lands and other wetlands, where fireshave tended to spread very widely and rapidly, and generate the bulk ofthe smoke that has prompted such great concern among Indonesia’s neigh-bors and those concerned about global carbon loadings (Page et al., 2002;Tacconi, 2003; Tan and Tay, 2003; Tomich and Lewis, 2002). Under cur-rent political and administrative conditions, any of these policy directionswill demand considerable investments in both institutional and technicalcapacity by Indonesia’s central and regional governments, international as-sistance, in addition to new private investments.

Land Tenure, Land Use and Resource Allocation, and Regional Autonomy

Evidence from our research confirmed that by far the most commonunderlying cause of fire was related to competition and conflict about landtenure and land allocation.

Early hopes in the post-Suharto reform period that increased regionaladministrative and fiscal autonomy would enable the equitable and effec-tive reforms in resource allocation necessary to reduce fire risks originatingin tenure conflicts or uncertainty (Barber and Schweithelm, 2000; Downto Earth, 2002) are now being put to the test, with less than encouragingindications to date. Prior to 1999, when the reforms started to come in toeffect,16 central government agencies granted resource-use concessions toprivate companies, parastatal enterprises, and government land develop-ment projects. Land-use allocation decisions made by central governmentagencies frequently overlaid concession and project boundaries on local ju-risdictions and indigenous communities’ customary territories, and prop-erty held under local customary law (adat). In some cases, different centralgovernment agencies designated incompatible uses on the same land (mostseriously, mining or logging concessions in nature conservation areas).

Regional reform clearly opens the way for resolution of resource con-flicts in ways more in keeping with the diversity of local customary law,

16The most significant regional autonomy laws are Law 22 on Regional Governance and Law25 on Fiscal Balancing, both issued in May 1999 (Resosudarmo and Dermawan, 2002). Offi-cial national decentralization began on 1 January 2001.

Fire, People and Pixels 493

and offers opportunities for regional government to “harmonize” decisionswith those of local and customary institutions. From a recent CIFOR studyof decentralisation and forests across Kalimantan and Sumatra, evidence ofstakeholder participation and consultation in district decision-making wasvariable. For example, Casson found positive evidence in West Kutai Dis-trict, East Kalimantan, especially the involvement of local NGOs. However,the scenario in Central Kalimantan was much more disheartening (Casson,2001a,b). Ironically in Kalimantan and Sumatra, the regional authorities’increased access to and dependence on regionally generated revenues mayactually increase pressure on officials to permit potentially lucrative usesof land and resources claimed by local communities and their members,regardless of their effects on fire risks (Barr et al., 2001). Strong regional in-stitutions, representing local interests through elected representatives andconsultation with people most directly affected by resource allocation de-cisions, as well as with commercial and other stakeholders, must give sig-nificant weight to local interests in social justice in the face of often over-whelming commercial pressures (Bennett, 2002; Byron, 2004; Tomich andLewis, 2002).

Regional reforms should also ensure that land and resource allocationsand decisions at all levels are compatible with physical site characteristics,prominently taking fire risks into account. Technical aspects of these analy-ses should be widely accessible, and should assess a wide variety of potentialimpacts of proposed developments—including fire risks—as well as oppor-tunities for more sustainable alternative land and resource uses. However,Indonesia’s legacy of inaccurate maps, overlapping boundaries, and a lackof technical expertise at the Provincial and District levels will make this adifficult task (Potter and Badcock, 2001).

Reducing Forest Degrading Practices

Policies to improve land management by all stakeholders, and mea-sures to restore ecological integrity to degraded natural forests are ex-tremely important to reduce the incidence of repeated fires in the remaininglogged-over and secondary forests of Kalimantan and Sumatra. Promotingcommunity involvement in such rehabilitation efforts or management plansis critical for their success in reducing fire risks. Sustainable land use bysmallholders integrating both subsistence crops (including diverse rice andother staple cultivation systems) and commercial crops (focusing on sustain-able and lucrative agroforestry production with potential regional compar-ative advantages, such as rubber, coffee, fruit, rattan) needs to be promotedthrough improved government support for research and extension services,along with opportunities to enlist the resources of private enterprises.

494 Dennis et al.

Our research (e.g., at Menggala, MUBA, and Tumbang Titi) stronglyindicates that special attention should be paid to swamp areas, where risksof extensive fires have been extremely high; and deforested landscapes,which in drought years are very fire-prone. Regional authorities should ap-prove land development proposals only with the strongest precautions toreduce risks generating smoke and uncontrolled fires. The need to sustainexisting transmigration schemes in the face of limitations on burning andhigh risks of wildfire calls for technical assistance and appropriate resourcesto these new communities.

Developing locally acceptable techniques and institutional mecha-nisms to rehabilitate fire-prone Imperata grassland and other fire-degradedvegetation for more economically (and in many cases more ecologically)productive and fire resistant use holds promise for reducing the futureincidence and impacts of devastating fires (Garrity, 1996/97; Menz et al.,1998; YDT, 2003). Such efforts could generate significant and sustainableincome for local people as well as large-scale industry, unlike Indone-sia’s dominant models of industrial timber plantations and authoritarian“regreening” programs. Evidence from both failed and successful programsto date suggests that reinforcing local stakes in effective rehabilitation willbe important (Hartanto et al., 2003).

Building Institutional Capacity to Prevent and Suppress Fires

In Indonesia, as elsewhere, efforts to improve fire management haveconfronted tension between focusing resources on fire prevention versusfire suppression, and choices between building fire management systemsbased on centralized, authoritarian/paramilitary models versus more de-centralized, participatory, consultative, community-based models (Mooreet al., 2002). Recent legal and administrative reforms require companies tocontrol fires within their concession areas and private holdings (ostensiblyrequiring them to invest in fire suppression) and monitor or control burningby smallholders within their boundaries. Regional governments at Provin-cial and District levels are scrambling to implement new fire managementpolicies, designate responsibilities, and provide appropriate staff and tech-nology. The effectiveness of these measures has not yet been tested.

The results of this study suggest two major considerations in buildinginstitutional infrastructure for fire management. First, the diversity ofunderlying causes of fire and of fire impacts in Kalimantan and Sumatrahighlights the need to develop fire management systems that address partic-ular concerns of specific areas. A national framework providing some uni-formity of purpose should help make available appropriate and sufficient

Fire, People and Pixels 495

resources to improve fire management to regions that need them, whilerecognizing the diverse needs of different regions and the people withinthem.

Second, remote sensing technology, digital mapping, and instanta-neous communications hold great promise for supporting Indonesian ef-forts to predict, detect, and respond to potential fire crises, and eventuallyto prevent unwanted fires from occurring (Tomich, 1999). These technolo-gies also hold promise for supporting enforcement of burn prohibitions andinvestigations of alleged illegal commercial burning. However, “high-tech”information and communication must be broadly accessible, widely used,and transparently controlled if they are significantly to improve fire man-agement “on the ground” in remote regions. Institutional capacity to deploy“high tech” information technology cannot replace locally based knowl-edge, skills, planning and cooperation, a sense of fairness, and material re-sources for fire management.

Economic Incentives and Disincentives

Beyond providing effective criminal and monetary penalties for illegalburning and liability for fire damage, some policy analysts seeking solutionsto Indonesia’s fire problem place enormous confidence in the potential foreconomic policy reforms and market-based incentives to minimize fire risksand promote sustainable land use, with disincentives for forest conversionand unsustainable land use. Although the rationales behind many proposedpolicy instruments are clear in economic theory, serious empirical tests formost of them must wait for their large-scale implementation.

A combination of eco-labeling and international trade restrictions toshrink markets for commodities produced in ways that pose high-fire risksmay hold promise. For example, “fire-safe” labeling programs, similar toemerging eco-labeling of sustainable timber or shade-grown coffee, couldidentify products grown by companies that do not burn, and by members ofcommunities that have adopted effective measures to minimize risks of ac-cidental fire. Over time, international restrictions could limit trade in prod-ucts whose producers cannot demonstrate that their products originate inlegal production areas.

Providing fiscal advantages to support companies’ initial investmentsin more effective fire management above and beyond increased legally re-quired minimum levels could make such over-minimum investments moreappealing to timber, plantation, and mining companies. However, with on-going fiscal devolution to regional governments, such measures would likelyrequire support from central government or international sources.

496 Dennis et al.

Other market-oriented measures could include the removal of market-ing restrictions on wood from agroforestry species felled during replant-ing (e.g., eliminating marketing restrictions on rubber wood), which wouldreduce biomass burning and hence smoke pollution (Tomich and Lewis,2001). However, such incentives would need to be carefully crafted to coveronly planted agroforestry species and to avoid encouraging additional de-forestation.

CONCLUSION

As outlines of Indonesia’s national and regional fire managementinstitutions are just emerging, debates on the most effective means to buildfire management capacity are colored by broadly contested debates on po-litical, economic, and administrative reform. All agree that more effectivefire management must draw on technical knowledge and investments bygovernment at several levels, land development and resource extractioncompanies, and local smallholders and communities. However, theseparties often disagree about the most effective division of responsibilities,and about the fair share of total efforts that each should bear.

This study identifies both constraints on institutional development forfire management, and specific opportunities to improve fire managementwithin each region studied, and in general. The diversity and complexity ofunderlying fire causes that this study identifies also point to three areas ofcontroversy where study results suggest appropriate opportunities.