Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print

Transcript of Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of PrintAuthor(s): Louise M. BishopSource: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 106, No. 3 (Jul., 2007), pp. 336-363Published by: University of Illinois PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27712660 .

Accessed: 13/04/2015 10:32

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journalof English and Germanic Philology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print

Louise M. Bishop, Robert D. Clark Honors College, University of Oregon

Even in the fifteenth century, Chaucer was seen by his countrymen as the

preeminent English poet, the father, as Dryden was to call him in 1700, of

English poetry.1 Despite general agreement in the fifteenth and sixteenth

centuries about Chaucer's poetic preeminence, however, Thomas Speght's

edition of Chaucer's Works (1598, STC 5077, 5078, 5079; 1602, STC 5080,

5081)2 adds elaborate textual apparatus?illustrated frontispieces, life

i. Ethan Knapp, The Bureaucratic Muse: Thomas Hoccleve and the Literature of Late Medieval

England (University Park, PA: Penn State Univ. Press, 2001), points out that "in the early fifteenth century" the father metaphor "was actually used by only one poet, Thomas Hoc

cleve" (p. 108): it is not used by Lydgate. In print the metaphor appears early with William

Caxton in 1477, so that A. C. Spearing's claim that "the fatherhood of Chaucer was in effect

the constitutive idea of the English poetic tradition" still has purchase {Medieval to Renaissance

in English Poetry [Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1985], p. 92, quoted in Knapp, p. 108, n. 5). In his influential book, Chaucer and His Readers: Imagining the Author in Late Medieval

England (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1993), especially Chapter 5, "At Chaucer's Tomb:

Laureation and Paternity in Caxton's Criticism," pp. 147-75, Seth Lerer argues that print and editors efface Chaucer's fatherhood in favor of laureation to emphasize the role of an

editor, rather than the (dead) poet, in the production of books by humanist editors. This

essay qualifies that claim for the sixteenth century, arguing that the trope of living father

Chaucer continues to appear in print to counteract print's commodified lifelessness and,

especially in the last folio editions of his Works, to realign Chaucer's forced alliance with

Tudor politics. 2. Alice Miskimin, "The 1598 Folio of Speght," in The Renaissance Chaucer (New Haven:

Yale Univ. Press, 1975), pp. 250-55, and Derek Pearsall, "Thomas Speght, c. 1550-?" in

Editing Chaucer: The Great Tradition, ed. Paul G. Ruggiers (Norman, OK: Pilgrim Books,

1984), pp. 71-92. See also Rewriting Chaucer: Culture, Authority, and the Idea of the Authentic

Text, 1400?1602, ed. Thomas Prendergast and Barbara Kline (Columbus: Ohio State Univ.

Press, 1999); Kathleen Forni, The Chaucerian Apocrypha: A Counterfeit Canon (Gainesville: Univ. Press of Florida, 2001); and Stephanie Trigg, Congenial Souls: Reading Chaucer from Medieval to Postmodern (Minneapolis: Minnesota Univ. Press, 2002).

For the purposes of this essay, I have consulted two early editions of Chaucer, both owned

by the special collections department of the Knight Library, University of Oregon: PR 1850 1561, a second impression of the John Stow edition of 1561 of Chaucer's Works, STC 5076;

and PR 1850 1687, a 1687 edition of John Speght's 1602 edition of Chaucer's Works, C3736. In his 1602 edition (STC 5080, 5081 ), Speght added some material to his 1598 edition (STC

5077, 5078, 5079): see Pearsall, "Thomas Speght," pp. 83-90, and also Eleanor Prescott

Hammond, Chaucer: A Bibliographical Manual (New York: Macmillan, 1908), pp. 125-27. The 1687 edition reprints Speght's 1602 edition with some twenty-two lines added to the ends of The Cook's Tale and The Squire's Tale along with an "Advertisement" by "J. H."

asserting the volume's quality, according to Pearsall, "Thomas Speght, c. 1550-?" p. 91, and

Hammond, Chaucer: A Bibliographical Manual, pp. 127-29. I thank special collections for their courtesy.

Journal of English and Germanic Philology?July ? 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 337

histories and genealogies, epistles and dedicatory poems?that insist on

Chaucer's literary value in a particular way: they

use the tropes of Chau

cer as father and as living presence to affirm Chaucer's literary worth.

These apparatus?or peritexts, to borrow Gerard Genette's term3?invoke

Chaucer's living voice through dialogues and letters; their images picture him as if alive and situate his fatherhood, as well as his poetry, in the midst

of Tudor politics. Many peritexts are new to Speght's editions; others carry over from his editorial predecessors William Thynne (1532, STC 5068) and John Stow (1561, STC 5075, 5076). What prompts this expression of Chaucer as father and as living presence?

Seth Lerer has argued that a Chaucer made into (dead) artifact char

acterizes print editions of the poet's works, such as Caxton's from the

fifteenth century; James Simpson uses Lerer's argument

to propose two

tropes, "remembered presence" and "philological absence," that control

Chaucer's reception between 1400 and 1550.4 I counter that Chaucer's

editors and literary progeny throughout the sixteenth century make father

Chaucer live to answer printed books' loss of "aura," as Walter Benjamin

would term it.5 Benjamin's word "aura" treats film art and its attempts

to recreate stage presence, but books and reading also involve presence

and absence. A living father Chaucer participates in the "identifiable sys temic links between texts, printed books, reading, mentalities, and wider

consequences" that William St. Clair notes in his recent analysis of print

3- Gerard Genette, Paratexts: Threshholds of Interpretation, trans. Jane E. Lewin (Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997). As Richard Macksey explains in the foreword, paratexts

"compris[e] those liminal devices and conventions, both within the book (peritext) and

outside it (epitext), that mediate the book to the reader: titles and subtitles, pseudonyms, forewords, dedications, epigraphs, prefaces, intertitles, notes, epilogues, afterwords . . . the

elements in the public and private history of the book" (p. xviii). Peritext includes "such

elements as the title or the preface and sometimes elements inserted into the interstices of

the text, such as chapter titles or certain notes" (p. 5). My argument about folio editions of

Chaucer concerns dedications, a title page, an illustration, and poetry addressed to readers,

hence "peritexts." Paratexts as advertisements for authors and booksellers and their effects

on the idea of an author have been treated for fifteenth- and sixteenth-century French texts

by Cynthia Brown, Poets, Patrons, and Printers: Crisis of Authority in Late Medieval France (Ithaca:

Cornell Univ. Press, 1995). 4. James Simpson, "Chaucer's Presence and Absence 1400-1550," in The Cambridge Com

panion to Chaucer, ed. Piero Boitani and Jill Mann (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003),

pp. 251-69. Relying on Lerer, Simpson delineates changes in the "literary system" (p. 261 )

that made Chaucer's texts into "archeological remains" (p. 251): "By the 1520s Chaucer

has, then, definitely gone, leaving only textual remains" (p. 267). As I hope to show, the

trope of living father Chaucer modifies Simpson's claims.

5. Walter Benjamin, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in Il

luminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1968),

pp. 219-53: "aura is tied to presence" and "The aura which, on the stage, emanates from

Macbeth, cannot be separated for the spectators from that of the actor" (p. 231). I thank

my colleague Kathleen Karlyn for pointing me to Benjamin's essay.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

338 Bishop

culture.6 Books are, by the sixteenth century, part of "a new scheme of

values concerning inanimate objects":

by the end of the 16th century, an opposition between the material world

and the realm of language and ideas that had been an extreme and radical

position . . . two hundred years earlier had moved to the very heart of Eng

lish cultural life.7

Images of and words about a living poet return materiality to language to

reinvest lifeless print with material being's "aura." The trope of Chaucer's

living fatherhood apparent in both word and image in sixteenth-century

printed books animates Chaucer's presence. Benjamin's concept of "aura"

lets us understand the efforts printed books, especially print editions of

Chaucer, make to revive him and animate his living presence.

Living father Chaucer, revived in books as a national figure to serve

the dynastic needs of Henry VIII and "staged" in a bookish fashion dur

ing Elizabeth's reign, answers the isolation, foreignness, and alienation

that mechanical reproduction cannot avoid. A close look at the efforts of

Chaucer's various editors and sixteenth-century authors to present Chaucer

as living and as father shows the ways these two tropes attempt to invest

print with "presence" in time and space in order to counter its depreciation as

commodity. Moreover, near the end of Queen Elizabeth's reign, in an

edition overloaded with multiple peritexts, John Speed's pictorial figura tion of Chaucer as father and living presence published in Speght's edition

of "The workes of our an tient and learned English poet, Geffrey Chaucer,

newly printed" ( 1598) not only counters print's dead, commodified nature

but lets us read one of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales as an especially poignant

antiauthoritarian plea. Through a long-standing identity of the poet with

The Tale of Melibee, a living father Chaucer confronts autocratic rulership in anticipation of successive change?of rulers, readers, and books.

To support these claims I will first note the tropes of Chaucer's father

6. William St. Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press,

2004): printed books fit "governing economic and intellectual property structures, financ

ing, manufacturing, prices, access, and actual reading" (p. 439) which differ from those of

manuscript culture. Other works on the idea of print include Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Print

Revolution in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1983); David Quint, Origin and Originality in Renaissance Literature: Versions of the Source (New Haven: Yale Univ.

Press, 1983); and Kevin Dunn, Pretexts of Authority: The Rhetoric of Authorship in the Renaissance

Preface (Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 1994). On medieval ideas of authorship, see The Idea

of the Vernacular, ed. Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, Nicholas Watson, Andrew Taylor, and Ruth Evans

(University Park: Penn State Univ. Press, 1999), pp. 3-19, esp. "The Idea of an Author" (pp. 4-8) and "Textual Instability, Memory, and Vernacular Variance" (pp. 10-12).

7. John Hines, Voices in the Past: English Literature and Archaeology (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer,

2004), p. 138. Both Hines and St. Clair note that, while relations between print and manu

script remain fluid at the beginning of the sixteenth century, lines harden during the six teenth century.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 339

hood and living presence in manuscripts and printed books, especially in

two engravings included in editions of Chaucer's Works from the second

half of the sixteenth century. After elaborating on the implications of the

father/living presence trope for Chaucer's readers, I conclude with an

against-the-grain reading of Chaucer's Tale of Melibee. This prose text, far

from being a "retreat from poetry into staid secure prose,"8 exploits the

tropes of living father Chaucer, along with a nascent link between rhetoric

and drama,9 to body forth a critique of authoritarianism, even though

literary redemption remains only a fond hope as the Tudor lineage, but

not authoritarian regulation, meets its extinction.

I

Fifteenth-century manuscripts attest that Chaucer's earliest acolytes used

a number of expressions to denote Chaucer's preeminence

as English

poet, with "master" the special favorite.10 Thomas Hoccleve is the first to

use the epithet "father" for Chaucer. In The Regement of Princes (1412), Hoccleve not only laments Chaucer's death, but imagines Chaucer speak

ing to him:

"Hoccleue, sone?" "I-wis, fadir, f>at same."

"Sone, I haue herd, or this, men speke of pe" . . .

"O maister deere, and fadir reuerent!

Mi maister Chaucer, flour of eloquence, Mirour of fructuous entendement,

O, vniuersel fadir in science! . . .

Mi dere maistir?god his soule quyte!? And fadir, Chaucer, fayne wolde han me taght; But I was dul, and lerned lite of naght."

8. Seth Lerer, Courtly Letters in the Age of Henry VIII: Literary Culture and the Arts of Deceit

(Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997), p. 196. Lerer details the Henrician court's

manuscript culture, primarily coterie works that, in the case of Henry's love letters to Anne

Boleyn, achieve an un-looked-for currency.

9. Hines, Voices in the Past, explains that "drama as a means of training and education . . .

was a practical complement to the rhetorical training in dialectics through which medieval

students had to develop their argumentative and analytical skills . . . the history of dramatic

production in England for the most of the 16th century is consequently strongly marked

by records of theatrical performances in schools . . . and at colleges" (p. 144). 10. Lydgate begins his ca. 1409 "Commendacioun of Chaucer" with "And eke my master

Chauceris nowe is graue / The noble rethor Poete of breteine"; he repeats the epithet "master" for Chaucer in virtually every other English poem he wrote. In 1448 John Metham

calls Chaucer "My mastyr Chauncerys"; George Ashby (ca. 1470) calls Gower, Chaucer, and

Lydgate "masters"; Henry Scogan begins a ca. 1407 poem with "My maister Chaucier." See

Caroline Spurgeon, 500 Years of Chaucer Criticism, 3 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press,

1925), followed by Jackson Campbell Boswell and Sylvia Wallace Holton, Chaucer's Fame in

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

340 Bishop

Hoccleve blends "master" with "father," then repeats "master" twice more

in the poem, while also at one point calling Chaucer "firste fyndere of our

faire langage." Indeed, TheRegement of Princes uses an array of tropes?mas

ter, father, originator?to certify Chaucer's preeminence, while the text's

dialogue form?Chaucer speaks to Hoccleve?revivifies the dead poet.

Three manuscripts of Hoccleve's Regement add Chaucer's image to Chau

cer's voice.11 In London, British Library MS Harley 4866, a picture of the

poet appears next to the following verses:

AljDogh his lyfe be queynt, pe resemblaunce

Of him \\ap in me so fressh lyflynesse

f>at, to putte othir men in remembraunce

Of his persone, I haue heere his lyknesse Do make, to p'xs, ende in sothfastnesse,

{)at \>e\ {>at haue of him lest fought & mynde, By J)is peynture may ageyn him fynde.12

The manuscript's drawing of Chaucer points its finger at the word "like

ness" while the lines credit Hoccleve's living memory for the image's lin

eaments. Chaucer's pointing finger gently testifies to the image's verisi

England: STC Chauceriana, 1475-1640 (New York: Modern Language Association, 2004). Boswell and Holton treat printed materials only, not manuscripts, but they have "checked

every edition of every book to see if a reference to Chaucer is present and, if it is present, whether it has changed in any way" (p. xii). For the purposes of this paper, all references to manuscript material (pre-1475) come from Spurgeon. References to printed materials come from Boswell and Holton. On occasion, I have used the database Early English Books

Online, http://o-eebo.chadwyck.com.janus, for references: footnotes indicate these citations.

Both Spurgeon and Boswell and Holton arrange their entries chronologically. The reader

may thus refer to either edition as appropriate by means of the year cited. Additional refer ences to print sources other than Boswell and Holton, or manuscript sources not listed in

Spurgeon, are cited in footnotes. 11. London, British Library MS Harley 4866; Philadelphia, Rosenbach Museum and Li

brary MS 1083/10; and BL MS Royal 17 D.vi; see Derek Pearsall, "The Chaucer Portraits,"

Appendix 1 in The Life of Geoffrey Chaucer: A Critical Biography (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), pp. 285-305. See also Michael Seymour, "Manuscript Portraits of Chaucer and Hoccleve,"

Burlington Magazine, 124, no. 955 (October 1982), 618-23. Pearsall considers the Rosen

bach portrait an eighteenth-century addition to the manuscript (p. 291). Trigg, Congenial Souls, pp. 21-28, evaluates the power of voice for the "imagined community" of Chaucer's readers and scholars from the Renaissance to the late 1990s. While I differ from Trigg's assessment of Chaucer's living voice, her book has influenced my thinking about Chaucer's

"lively" appearance and his voice. 12. The image is reproduced in Seymour, "Manuscript Portraits," p. 619; Pearsall, Life,

p. 286; M. H. Spielmann, The Portraits of Geoffrey Chaucer (London: Kegan Paul, 1900), p. 7; and as a line drawing in Spurgeon, Chaucer Criticism, I, 22. Trigg, Congenial Souls, treats the

image of Chaucer in tandem with the "famous picture of Chaucer" pointing to his name

in the rubric of the Ellesmere Tale of Melibee and calls it a "narrating presence" (p. 50). See also Knapp, Bureaucratic Muse, pp. 104-22, and Christopher Cannon, The Making of Chaucer's

English (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998), p. 12, on the word "finder" that exercises an "Hocclevian arc toward the infinite" to escape the confines of language.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 341

militude, but it also, in indicating the word "likeness," recalls the image's

representational nature. Pictures may gesture at life, but at the same time

they remain pictures. Still, so self-conscious an image

as Hoccleve's of Chau

cer, joining picture and text, indicates the protean relationship between

"figured objects and people" that Hoccleve uses: he expects his readers'

thoughts and minds will, through this "peynture," "ageyn . . .

fynde" Chau

cer, "fyndere" of the English language.13 While Hoccleve's image situates the reader as Hoccleve's companion,

hoping that those who have forgotten Chaucer's appearance will now

remember him, most readers have to do so without the aid of a "like

ness": just three of the forty or so manuscripts of The Regement include

a Chaucer image, and the image in one of those?Philadelphia, Rosen

bach MS 1083?was drawn in the eighteenth century. Still, "likeness"

of an author is an idea new to this time14 and Chaucer was not alone in

having his image painted in manuscripts. Two full-length portraits, in

Cambridge, Pembroke College MS 307 and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 290, portray the senex amans of the Confessio Amantis?-John Gower?without the kind of name attribution or pun on "likeness" found

in the Hoccleve manuscript's illustration of Chaucer.15 But Gower's like

ness, as well as Chaucer's and his "child" Hoccleve's, appears in several

initials in the deluxe Bedford Psalter (ca. 1410), and in one, "an explicit label on the background of the portrait

. . . identifies the elderly, bald

ing and bearded" Gower.16 Of the Psalter's three images of Hoccleve and

three of Chaucer, none has any identification like Gower's. However, the

drawings of Chaucer are thought

to come from the same hand that drew

his portrait in Harley 4866, the Regement of Princes manuscript already discussed. Portraiture begins

to denote authors for readers in the context

of late medieval manuscripts.

13- For an analysis central to my thinking about the living resonance of images, see David

Freedberg, The Power of Images (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1999): "image [is] more

than it seems" (p. xxiv) and "figured objects and people" are always "disrupting natural law"

(p. 43). See also Maidie Hilmo, Medieval Images, Icons, and Illustrated English Literary Texts

(Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2004): the medieval audience regards "visual details as a

signifying system for both literal truth ('what each looks like') and symbolic truth ('what

each stands for' or 'figures')" (p. 18), distinct from the Renaissance's "primary referent,"

which is "terrestial reality" (p. 10).

14. Sylvia Wright, "The Author Portraits in the Bedford Psalter-Hours: Gower, Chaucer

and Hoccleve," British Library Journal, 18, no. 2 (Autumn 1992), 190-201, sees the first com

memorations of Dante and Petrarch ca. 1375 as the genesis of author portraits (p. 190).

15. Derek Pearsall, "The Manuscripts and Illustrations of Gower's Works," in The Companion to Gower, ed. Si?n Echard (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2004), points out that the "unusual and

seemingly rather inappropriate choice" of an old man with forked beard shows that "The

artist, or the supervisor who gave him his instructions, has chosen the literal truth rather

than the literary subterfuge" (p. 89). 16. See images in Wright, "Author-Portraits"; for the explicit label, p. 192.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

342 Bishop

Admittedly, manuscript images are limited in their cultural purchase to a rather minimal, though influential, audience. But manuscripts

are

not the exclusive purveyors of Chaucer's and Gower's images. Gower's

chantry and tomb in the chapel of John the Baptist in St. Mary Overie, Southwark, may have been designed

as early

as the last years of Gower's

life; he died in 1408.17 Gower's chantry survived the religious tumult of the sixteenth century, so that antiquarian John Stow, who edited a 1561 folio edition of Chaucer, was able to describe the effigy and chantry in his 1598 Survey of London:

lohn Gower Esquier, a famous Poet, was then an especiall benefactor to that

worke, and was there buried on the North side of the said church, in the

chappie of S. lohn, where he founded a chauntrie, he lieth vnder a tombe of

stone, with his image also of stone ouer him: the haire of his head aburne,

long to his sholders, but curling vp, and a small forked beard, on his head a

chaplet, like a coronet of foure Roses, an habite of purple, demasked downe

to his feet, a collar of Esses, gold about his necke, vnder his head the likenes of

three bookes, which he compiled. The first named Speculum Meditantis, writ ten in French: The second Vox clamantis penned in Latine: the third Confessio amantis written in English, and this last is printed, vox clamantis with his Cr?nica

tripartita, and other both in latine and French neuer printed, I haue and

doe possesse, but speculum meditantis I neuer saw, though heard thereof to be in Kent: beside on the wall where he lyeth, there was

painted three virgins crowned, one of which was named Charity, holding this deuise.18

Chaucer too had a public tomb, and ca. 1556, following Nicholas Brigham's enhancement, worshippers in Westminster Abbey could have seen a por trait of Chaucer between the sepulchre's arches.19 Speght's 1598 edition

(STC 5077) provides the earliest written record of it, and Elias Ashmole's Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum ( 1652) provides the earliest image.20 The

figure holds a rosary in his left hand, a mark perhaps of an attempt to reclaim Chaucer for Roman Catholicism during the reign of Queen Mary.

While Westminster worshippers could see Chaucer's image in the second half of the sixteenth century, the upper crust could see portraits of the author in fine houses. Some six portrait panels survive from the sixteenth

century, but no such tradition immortalizes Gower. Chaucer's image had

special currency in sixteenth-century England.

17-John Hines, Nathalie Cohen, and Simon Roffey, "Iohannes Gower, Armiger, Poeta: Records and Memorials of His Life and Death," in A Companion to Gower, pp. 23-41, with photograph of the tomb (p. 37).

18. A Survey of London by John Stoiu Reprinted from the Text of 1603, ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908), I, 57.

19. Joseph A. Dane, Who is Buried in Chaucer's Tomb? (East Lansing: Michigan State Univ. Press, 1998), pp. 10-32.

20. See Dane, Who is Buried, p. 13, for Speght's description, with an image from the 1602 edition (STC 5080), and Pearsall, Life, p. 296, for an image of Ashmole's engraving.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 343

Chaucer and Gower both see print in deluxe folio editions in 1532.21 Unlike the tradition of Chaucer folios, the 1532 edition of Gower's Con

fessio Amantis (STC 12143)?a single work, unlike a "complete works"

edition like Chaucer's, and printed by Thomas Berthelet, business part ner with Chaucer's printer Thomas Godfray?is reprinted once, in 1554

(STC 12144), before it vanishes from continued impression. The Confessio Amantis sees deluxe folio again only in the nineteenth century. Chaucer's

complete works, however, see continual folio printing throughout the

sixteenth century, but his readers have to wait until 1598 for his "like

ness," as in the Hoccleve manuscript, the Bedford Psalter, or his tomb, to

emerge in print. Printed portrait or no, the "father" epithet applied to Chaucer, first

used in manuscript, follows Chaucer into print. In his 1477 Book ofCurtesye (STC 3303) William Caxton addresses Chaucer "O fader and founder of

ornate eloquence" and repeats himself in a 1478 epilogue to the Consola

tion of Philosophy, calling Chaucer "the worshipful fader 8c first foundeur

8c embelissher of ornate eloquence in our englissh."

The epithet endures

another century: in 1575, George Gascoigne uses it in his "Certayne Notes

of Instruction concerning the making of verse or ryme in English," part of

The posies of George Gascoigne esquire (STC 11637): "also our father Chaucer

hath used the same libertie in feete and measures that the Latinists do

use." In the same text Gascoigne, like Hoccleve, combines "master" and

"father" in one phrase

to describe Chaucer's particular verse form, "rid

ing rhyme": "that is suche as our Mayster and Father Chaucer vsed in his

Canterburie tales, and in diuers other delectable and light enterprises." In contrast, the somewhat later Cobler of Caunterburie (1590, STC 4579), a

collection of stories told by a Thames boating party to imitate Chaucer's

pilgrimage narrative, adds "old" to the father epithet, with no reference to

"master," making the work's most frequent epithet

"old Father Chaucer."22

This ostensibly endearing phrase simultaneously compliments the poet and relegates him to the past. The author's admission that "Syr Jeffrey Chauceris so hie aboue my reach, that I take Noli altum sapere, for a

warning,

and onely looke at him with honour and reuerence" follows Hoccleve's

desire to put his father Chaucer's "likeness" on the page tojog his reader's

21. James E. Blodgett, "William Thynne," in Editing Chaucer: The Great Tradition, ed. Paul

G. Ruggiers (Norman, OK: Pilgrim Books), pp. 35-52; Echard, Companion to Gower, pp.

115-35, esP- PP- 116?17. See also Forni, Counterfeit Canon, pp. 45-54. 22. The Cobler of Caunterburie and Tarltons Newes out of Purgatorie, ed. Geoffrey Creigh and

Jane Belfield (Leiden: Brill, 1987); John Pitcher, "Literature, the Playhouse and the Public,"

in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, vol. 4: 1557-1695, ed.John Barnard and D. F.

McKenzie with the assistance of Maureen Bell (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002), p.

367. Creigh and Belfield mention the possibility that the text is the work of Robert Greene

(pp. 9-10).

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

344 Bishop

memory and encourage his friendship: after hearing Chaucer's voice,

Hoccleve provides his reader Chaucer's likeness. The Coblers narrator also

uses voice to match his reverential gaze at Father Chaucer: he asks the

reader, "What say you to old father Chaucer?" The father trope in manu

script and print makes Chaucer genial and approachable, his reader's

eyes reaching him, his fatherhood folded into his voice and his reader's.

William Thynne's 1532 folio edition of Chaucer's collected Workes is not

the first folio of Chaucer printed: in 1526 Richard Pynson prints a folio

Canterbury Tales (STC 5086). But Thynne's edition, a complete Works, cre

ates Chaucer as "champion of the King [Henry VIII] against the conflict

ing claims of Church and nobility."23 Chaucer's earliest printer, William

Caxton, veteran of the War of the Roses, had already planted Chaucer into

the "Tudor Myth" for Henry VIII's father, Henry VII, who was "conspicu ously weak in his ancestral connections."24 Without mentioning Henry

VII by name, Caxton includes Chaucer among the "clerkes, poetes, and

historiographs" whose "many noble bokes of wysedome of the lyues, pas sions, & myracles of holy sayntes of historyes, of noble and famous Actes and faittes, And of the cronycles sith the begynning of the creaci?n of the

world" have contributed to "thys Royame."25 By 1532, "the royal patron

age of [Thynne's edition of Chaucer] was one of the many autocratic,

centralizing gestures of Henry's regime, and was intended to augment

Henry's own

glory and strength."26 Even the gesture of a Chaucer edition,

centralizing all of Chaucer in one book?a fate Gower escapes?imitates the authoritarianism of Tudor hegemony, providing "textual correlatives

of bureaucratic centralization."27

Chaucer may seem a natural for immersion in "The Tudor Myth," be

23-John Watkins, "'Wrastling for This World': Wyatt and the Tudor Canonization of

Chaucer," in Refiguring Chaucer in the Renaissance, ed. Theresa M. Krier (Gainesville: Univ. Press of Florida, 1998), p. 23.

24. E. M. W. Tillyard, Some Mythical Elements in English Literature (London: Chatto and

Windus, 1961), p. 47. Tillyard includes among the myth's popularizers Edmund Spenser, William Warner, Michael Drayton, John Dee, and Edward Hall (p. 53). To Tillyard's list of Tudor apologists, add John Stow, editor of the 1561 Chaucer edition, whose Chronicles

of England (1580) "present in chronicle form the legend of England as a people chosen

by God for His own purposes"; Rosemary O'Day, The Longman Companion to The Tudor Age (London: Longman, 1995), p. 79. Tillyard's handy title cannot comprise all the subtleties of

Tudor rule: see David Loades, Power in Tudor England (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997), for the shape of the Tudors' "personal monarchy," and on print his Politics, Censorship and the English Reformation (London: Pinter, 1991); also King, Tudor Royal Iconography: Literature

and Art in the Age of Religious Crisis (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1989). 25. W.J. B. Crotch, The Prologues and Epilogues of William Caxton, EETS o.s. 176 (London:

Oxford Univ. Press, 1928), pp. 90-91. 26. Theresa M. Krier, "Introduction," in Refiguring Chaucer in the Renaissance, ed. Krier,

p. 10.

27. Watkins, "'Wrastling for This World,'" p. 24.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 345

cause he lived during its inception. Chaucer's king was Richard II, whose

deposition fomented the York-Lancaster fracas now known as the War of

the Roses that eventually led to Henry Tudor's power grab in 1485. The

Tudor era, begun with Henry Tudor's ascension as Henry VII, officially concludes with Elizabeth's death in 1603. But Chaucer's biography did

not automatically identify him with the Tudors nor match his attitudes

with their policies. "Antiquarian enterprises like Thynne's often had a dis

tinctly counter-monarchical implication, the establishment of an English national identity apart from the Crown": Chaucer was alternately viewed as

a "right Wicleuian" and abettor of Protestant polemics or as sympathetic with Henry VIII's disaffected nobility.28 Chaucer's editors work hard to

identify him with the Tudor cause. Folio editions of Chaucer, dedicated

repeatedly to Henry VIII even after his demise, imbricate the poet with

the Tudors and their spin on England's national narrative:29 Thynne's dedication to Henry VIII, in which he asserts that Chaucer's Workes will

add to the "laude and honour of this your noble realme," continues to

be printed as peritext in every sixteenth-century folio edition, both the

reprints of Thynne and the new editions of John Stow ( 1561 ) and Thomas

Speght (1598 and 1602).30 Thynne's edition, produced during a year of parliamentary, royal, and clerical maneuvering that included a pro

rogued parliament and Thomas More's resignation

as chancellor, presages

Henry's Act of Supremacy (1534) and exemplifies the complicated and

unsteady alliances publishers and printers make with (dead) poets, living monarchs, and authoritarian national politics.31

"Father" Chaucer in folio

editions affects "father Chaucer" for Gascoigne and the Cobler author:

the poet is both remote and reachable, visible and audible in a readerly fashion begun with Hoccleve, now touched with Chaucer's immersion in

Tudor authoritarianism. Tudor politics and Chaucer's fatherhood work

28. Watkins, "'Wrastling for This World,'" pp. 23-25.

29. "Thynne's [1532] editions perhaps served Henrician dynastic and nationalistic im

peratives by establishing an English literary heritage . . . Chaucer's eloquence was valued

for its symbolic capital": Forni, "Thynne and Henrician Nationalism," Counterfeit Canon, p.

50.

30. On Thynne's 1542 and 1550 editions, see Martha W. Driver, "A False Imprint in

Chaucer's Works: Protestant Printers in London (and Zurich?)," Trivium,'*,! (1999), 131-54, who argues that the Thynne reprints were the work of Protestant, even offshore printers; Derek Brewer, Geoffrey Chaucer, Volume 1, 1385?1837, The Critical Heritage (London: Rout

ledge, repr. 1995), prints much of the Thynne's preface dedicating his edition to Henry

VIII, pp. 87-90. He also mentions the contention that the preface was written by Brian

Tuke. On the Tuke question, see Forni, Chaucerian Apocrypha, p. 30, and Trigg, Congenial

Souls, pp. 128 and 258, n. 41.

31. See Simpson, "Chaucer's Presence," and for a succinct chronology see Sharon L.

Jansen, Political Protest and Prophecy Under Henry VIII (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell, 1991),

pp. 21-24.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

346 Bishop

in tandem with the identity of family as nation to make Chaucer's readers

into Tudor subjects. The trope of Chaucer as father meshes with Tudor concerns about po

litical legitimacy as it limns their worries about succession and progeny:

Henry VIII's desire for a male heir and his daughter Elizabeth's virgin

queenship are among the family factors that animate Tudor policy, piety, and poetry.32 Although the Tudors are not unique in joining fatherhood

with nation, their success establishing "The Tudor Myth" in print and on

stage derived in part from their concerted efforts to regulate print. Henry VIII's treason legislation of the 1530s required all licensed books to print "cum privilegio regali ad imprimendum solum" on the title page; legisla tion in 1543 that specified penalties and in 1546 that required identity,

although aimed primarily at "theological matter," illustrates the climate in

which Chaucer's publishers worked.33 Tudor legislation of print matches

their innovative and absolutely authoritarian law of attainder, an act of par

liament pushed by Tudor interests that allows execution without trial. The

"steadily increasing efficiency and stringency of censorship" by 1590?the

print year of Cobler?gave "the English government a stronger grip on

the domestic printing industry than any other European monarch."34

In 1575 and 1590, Gascoigne and the Cobler author may have heard

their father Chaucer's voice in William Thynne's 1532 edition. Thynne himself, he tells us, had enjoyed hearing Chaucer: in his dedication to

Henry VIII, he writes of having "taken great delectacyon / as the tymes and

laysers might suffre / to rede and here the bokes of that noble 8c famous

clerke Geffray Chaucer."35 Or perhaps they heard their father Chaucer in a different folio edition: John Stow's 1561 Chaucer's Works is produced in the early years of Elizabeth's reign (1558-1603). Stow's book includes a suggestive image that joins father Chaucer to Tudor genealogy (fig. 1 ). Like Thynne's dedication to Henry VIII printed in later sixteenth-century folio editions, Stow's peritext also appears in a later edition, Speght's of

1598.36 This engraving depicts the lineage of Elizabeth's father Henry VIII: it begins with the family antagonists, Yorks and Lancasters, of the

32. "It can be difficult, if not impossible, however, to draw sharp distinctions among

political, pietistic, and aesthetic endeavors during this age [the Tudor age]": John N. King, Tudor Royal Iconography, p. 3.

33. See James Simpson, Reform and Cultural Revolution, vol. 2: 1350?1547, The Oxford

English Literary History (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2002), p. 338, n. 48, and "Chaucer's

Presence and Absence," pp. 265-66, for Henry's 1542 legislation that allows "Canterburye tales" and "Chaucers bokes" to continue in print.

34. Loades, Power, p. 122.

35. Francis Thynne's Animadversions upon Speght's first (1598 A.D.) Edition of Chaucers Workes, ed. G. H. Kingsley, revised F. Y. Furnivall, EETS o.s. g (London: Tr?bner, 1865), p. xxiv.

36. Anne Hudson, "John Stow, 1525?-! 605," in Editing Chaucer, ed. Ruggiers, pp. 57-58.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 347

War of the Roses. The illustration mimics a Jesse tree {radixJesse), a picto rial representation of the Virgin Mary's parentage familiar to medieval audiences.37 In a typical version of the Christian icon, Jesse, father of King David, lies at the illustration's bottom. A vine springs from his midsection to initiate the Virgin's genealogy, and this "tree" ascends through King

David to Jesus. In Stow's peritext, monarchs replace saints:38 a

recognizable

Henry VIII supplants?deposes??the Jesus who traditionally tops the im

age. Splitting the traditionally recumbent "Jesse" into two figures?John of Gaunt and Edmund, Duke of York?makes visible the two "houses" of

White and Red Rose central to the Tudor narrative. The ascent of rose

vines on either side of the illustration marks the division between the two

royal houses, their battles the subject of Shakespeare's history plays. The

vines culminate in a rose-enthroned King Henry VIII depicted, unlike

the other royals in the illustration, with all three accouterments of royal office?crown, scepter, sword?as father triumphant.39

In this fashion the

engraving replaces Jesus's family with England's royal lineage, equipped with the implements of authority?and punishment. Its allusion to the

Jesse tree suggests the redemptive quality of the patriarchal Tudor myth and Tudor authoritarianism, but its triumphalism mocks the mercy of

Mary's son.

This peritext functions in Stow's 1561 and Speght's 1598 editions as

title page for The Canterbury Tales: it layers Chaucer with Tudor genealogy. The title "The Caunterburie tales" appears in the center of the woodcut, surrounded by almost exclusively male Yorks and Lancasters. Besides

suggestively linking royal and divine history, the peritext, with its title

"The Caunterburie tales" weaves Chaucer together with English history in a matrix of royal "fatherhood." The image uses print and family to mix

royal, religious, national, and literary meanings together. Henry VIII's

family tree places Chaucer's Canterbury Tales squarely in the center of

royal genealogy and its concerns about legitimate progeny, patriarchal

authority, and political succession. Stow's image encapsulates Queen Elizabeth's bloodline, advertising her merits to

potential suitors while

conveniently eliding, three years into her reign, her dead and barren

siblings. When reprinted in Speght's 1598 edition after hope for Tudor

progeny has failed, Stow's woodcut, as "mediating literary artifact . . .

37- See Arthur Watson, The Early Iconography of the Tree of Jesse (London: Oxford Univ.

Press, 1934).

38. The Tudor wont to replace saintly images with their own is almost a critical com

monplace. See King, Tudor Royal Iconography, pp. 57-59, and Martha W. Driver, "Mapping Chaucer: John Speed and the Later Portraits," Chaucer Review, 36 (2002), 229-49.

39. The genealogy is, of course, fashioned to support Tudor ideology. Richard II is absent

from the page, and Henry VII looks to be inevitable as monarch.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

348 Bishop

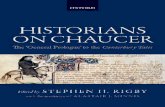

Figure 1. The woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer : newly printed with divers addicions, whiche were never in printe before

: with the

siege and destrucci?n of the worthy citee of Thebes, compiled by

John Lydgate, monke ofBerie : as in the table more

plainly dooeth

appere. London: Jhon Kyngston for Jhon Wight, dwellyng in Poules Churchyarde, 1561. Folio 5, recto. By kind per

mission of James Fox, head, special collections, Knight

Library, University of Oregon.

bears the traces of past as well as present social and political conflict."40

The picture's treacherous implications question Tudor fecundity and

Chaucer's relationship to it, and may have contributed to its elimina

tion in 1602 reprints of Speght's edition. No longer does Henry VIII's

genealogy frame father Chaucer: the increasingly fraught succession

40. Watkins, "'Wrastling for This World,'" p. 36.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 349

question encouraged the 1602 printers of Speght's edition to introduce

The Canterbury Tales without this peritext.

II

Besides the trope of "father Chaucer" traceable in both manuscript and

print, another trope?Chaucer as

living author?appears in the sixteenth

century. Thomas Proctor, in A Gorgious gallery of gallant inventions (1578, STC 20402), can only wish "If Chawser yet did live" in order to assure his

audience that, like Proctor, Chaucer too would write verses in praise of

"Mistress D." Samuel Daniel puts the wish for a living Chaucer even more

forcefully. In his Poeticall essayes (1599, STC 6261), he laments the "low

disgrace" of "hy races" that have occurred "Since Chaucer liu'd." While

this one part of Daniel's poem recognizes Chaucer's death, the rest of it

brings Chaucer back to life: "who yet Hues and yet shall, / Though (which I grieue to say) but in his last."41 What sort of hope are they expressing?

Marxist theory provides one way to understand this trope of a living Chaucer. In order to become objects of capital exchange, books as com

modities need to be drained of life, turned into "products that count for

more in social life than the real relations of persons."42 A printed book

does not entirely fit a Marxist idea of commodity: a book is not "a primary

good, such as coal or sugar, whose characteristics remain much the same

however much of it is produced," and booksellers have an interest in

"the fate of their product."43 But printed editions of Chaucer neverthe

less exemplify commodified lifelessness. Print's "deadness" contrasts with

the living nature of manuscripts: practices associated with manuscripts?

scraping, pointing, incising?emphasize their fleshly nature in contrast to

print.44 With word and image produced by hand on the skins of animals,

manuscripts embody the metaphor of "living words." Hoccleve's image

of Chaucer, meant to jog memory, fits the production

of manuscripts,

rather than the reproduction of printed books. Mechanical reproduction

changes books from heirloom to commodity. Print's early years did not inspire censorship: until the 1520s, its me

chanical nature occluded its political potency. Those efforts arise in the

4L Pitcher, "Literature, Playhouse," pp. 361-64, discusses Daniel's work.

42. Terrell Carver, A Marx Dictionary (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987), pp. 81-87, explains fetishism of commodities (quotation at p. 83); Brown, Poets, Patrons, and Printers, explores the way the printing press in France "led to the objectification, commercialization, and

commodification of the book" (p. 5); see St. Clair, Reading Nation, for modifications.

43. St. Clair, Reading Nation, p. 31.

44. See the editors' "Introduction," in The Book and the Body, ed. Dolores Warwick Frese

and Katherine O'Brien O'Keeffe (Notre Dame: Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1997), pp.

ix-xviii, for a meditation on manuscripts' lividity.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

3 5 o Bishop

1530s and grow in the 1540s. Nor does Elizabeth's official government

censorship begun in 1559 eliminate the seditious print of Shakespeare's

contemporaries, Latin historian William Camden (1551-1623) and poet Michael Drayton (1563-1631).45 Her 1586 Star Chamber decree "con

firmed the powers of the Stationers Company and the privileges of paten tees. Powers of censorship, previously mainly

a matter of self-censorship

within the industry, are

given to the ecclesiastical authorities": as William

St. Clair also notes, "From 1595. [sic] Ecclesiastical censorship tightened."46 Tudor authoritarianism tracks, but cannot contain, the figure of living father Chaucer: his liveliness answers commodification; his fatherhood

puts in perspective the Tudor hegemony's tragic family prospects, barren

like Macbeth's, unable to "stand in posterity"; and his image can challenge

reigning pieties as did his poetry in the hands of some of Henry VIII's

courtiers in the 1530s and 1540s.47

Father Chaucer's voice also sounds in three "protodramatic" dialogue texts that stage Chaucer in sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century print.

This small genre of living, speaking Chaucers resembles the dialogue Hoc

cleve works into his R?gentent of Princes and suggests intersections between

literature and the stage before Richard Burbage's 1576 purpose-built theater makes a theatrical idiom concrete.48 William Bullein publishes a tract against the plague, "A Dialogue both pleasaunte and pietifull"

(1564), in which he describes Chaucer preparing to speak of poetry:

Wittie Chaucer satte in a chaire of gold couered with roses, writing prose 8c Rime, accompanied with the spirites of many kynges, knightes and faire

ladies. Whom he pleasauntly besprinkeled with the sweete water of the well,

consecrated unto the Muses, ecleped Aganippe.

After this introduction and description, Chaucer speaks in iambic hex

ameter, asserting in his own voice "no buriall hurteth holie men, though

beastes them deuour, / Nor riche graue preuaileth the wicked for all

yearthly power." A living Chaucer here answers any wish to put him in

his grave in a fashion more powerful than a

monologue. Such dialogues

presage Elizabethan theatrical energy. A later sixteenth-century tract also includes this sort of speaking Chau

cer: Greenes Vision: written at the instant of his death ( 1592, STC 12 261 ) .49 A

45- Watkins, "'Wrastling for This World,'" p. 23.

46. St. Clair, Reading Nation, Appendix 2, p. 481. 47. Watkins, "'Wrastling for This World,'" p. 25.

48. Pitcher, "Literature, Playhouse," esp. p. 351, and Hines, Voices in the Past, esp. pp. 143-44.

49. See Helen Cooper, "'This Worthy Olde Writer': Pericles and Other Gowers, 1592-1640," in A Companion to Gower, ed. Si?n Echard, pp. 110-13, esp. 100-4. On Greenes Vision and

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 351

dream vision in prose and poetry, it treats a colloquy on literaryjudgment

ostensibly dreamed by Robert Greene, prolific Elizabethan dramatist and

writer. The vision recounts Chaucer, Gower, and Greene arguing about the

morality of their several works as well as the meaning of literature more

generally. While scholarly opinion divides on whether Greene himself wrote the work, his dramatic ambiance pervades it. After Greene states

his case regarding the fitness of his own poetry (or whether he wrote The

Cobler of Caunterburie), "Chawcer sat downe and laught, and then rising vp and leaning his back against

a Tree, he made this merry aunswer."50 The

colloquy goes on for some forty-one pages, and includes Chaucer again

being called, as in The Cobler of Caunterburie, "old." Although Chaucer

loses the argument, his liveliness in Greenes Vision makes "old" seem an

affectionate epithet. When Greene accedes to Gower's injunction to

leave off writing of love, "Chawcer shakt his head and fumed."51 Then

Solomon, like a deus ex machina, appears and has the last word, enjoining

Greene to "leave all other vaine studies, and applye thy selfe to feede

upon that heauenly manna," to which the waking Greene accedes, con

cluding with "as you had the blossomes of my wanton fancies, so you shall

haue the fruit?s of my better laboures."52 While Gower's morality "wins,"

Chaucer's voice argues for tolerance. He tells Greene not to concern

himself with the ascription of the Cobler, and his tale, while lacking a

moral issue at its heart, teases authority through the comeuppance of

a jealous husband. Helen Cooper reads Greenes Vision on the worth and

morality of literature this way: "Literature may indeed be wanton; but

although its attractiveness may make it suspect, that does not in every

case necessitate a denial of its worth, its power of persuading to virtue.

The responsibility may, however, fall as much on the reader as on the

writer."53 A living father Chaucer, ostensibly bested by John Gower, makes

the more important case for readerly judgment, itself possibly a matter

of life and death under the Tudors.

In a final instance of a dramatically speaking Chaucer?Richard Brath

wait's "Chaucer's Incensed Ghost" (1617, STC 3585), a

post-Tudor poem

attached to The Smoking Ages, or, The man in the mist: with the life and death

of Tobacco?Chaucer voices his unhappiness and disgust, not only to have

"self-authorization," see Lori Humphrey Newcomb, Reading Popular Romance in Early Modern

England (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2002), pp. 47, 52.

50. Brewer, The Critical Heritage, pp. 130-35, prints a fair amount of Greenes Vision, as do

Boswell and Holton.

51. Accessed through the Early English Books Online (EEBO) database (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1998- ), February 13, 2005.

52. EEBO, accessed February 13, 2005.

53. Cooper, "'This Worthy Olde Writer,'" p. 104.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

352 Bishop

been brought "o' th' stage," but at the damage "Pipe-Pageants" are

having

on his reputation:

Las; Is it fit the stories of that book,

Couche'd and compil'd in such a various forme,

Which art and nature joyntly did adorne,

On whose quaint Tales succeeding ages look,

Should now lie stifled in the steems of smoak,

As if no poet's genius could be ripe Without the influence of Pot and Pipe?54

Father Chaucer speaks to

reputation, not

regulation; genius, not morals,

in defending his tales now "subjects both for Presse and Stage."55 Not

only a

living visitor, Chaucer is father, except to "a brat hee never got,"

and requires that his audience "conceive this well." For this living father

Chaucer, stage and press equally bring his generative figure back to life.

The desire for a living Chaucer to meet the restrictions of print produces a small genre of "performing" Chaucers. The trope of a living Chaucer

uses the stage's idiom of presence56

to counteract the commodified life

lessness of print's mechanical reproduction.

The last sixteenth-century folio edition of Chaucer's Works, Speght's in

1598, provides the most powerful representations of living father Chaucer

to answer "dead" print. Speght's edition includes many more peritexts than

had its predecessors. One is a long biography, "Chaucers Life," divided

into "His Marriage," "His Education," "His Revenues," "His Rewards," "His

Children, with their advancement" (a long section), and "His Countrey."

Speght's other peritexts include a glossary of hard words, a drawing of

Chaucer's arms like that found in sixteenth-century wealthy houses' panel

portraits, and a schematic of his family tree, in Latin. Speght's printed words,

like those of Bullein, Greene, and Brathwait, animate father Chaucer.

A poetic peritextual dialogue, reminiscent of Hoccleve's, has two speak

ers, "The Reader" and "Geffrey Chaucer." Not only Chaucer but his?and

Speght's?reader speaks: a revoiced Chaucer joins

a uniquely voiced read

er.57 The poem's content

specifically adumbrates an editor's concern about

54- Included in Caroline Spurgeon, Richard Brathwait's Comment, in 1665, upon Chaucer's

Tales of the Miller and the Wife of Bath (London: Kegan Paul, 1901), pp. viii-xi.

55. Spurgeon, Richard Brathwait's Comment, p. x.

56. "Aura is tied to [an actor's] living presence; there can be no replica of it. The aura

which, on the stage, emanates from Macbeth cannot be separated for the spectators from

that of the actor . . . Any thorough study proves that there is indeed no greater contrast

than that of the stage play to a work of art that is completely subject to it or, like the film, founded in, mechanical reproduction"; Benjamin, "The Work of Art," pp. 231-32.

57. Peter Stallybrass and Margreta de Grazia, "Love Among the Ruins: Response to Pech

ter," Textual Practice, 119 (1997), 69, suggest that modernity predicates "certainty on the

existence of consciousness" (p. 69). The appeal to the reader's voice as well as a revoiced

Chaucer signals this shift towards consciousness as a literary issue.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 353

book as commodity. Both Chaucer and Reader use the language of print to praise Speght for his tireless work.

Reader

Where hast thou dwelt, good Geffrey, all this while, Unknown to us, save

only by thy Books'?

Chaucer

In Haulks and Herns, God wot, and in Exile, Where none

vouchsaft to yield me Words or Looks;

Till one which saw me there, and knew my Friends, Did bring me forth: such Grace sometime God sends.

Reader

But who is he that hath thy Books repair 'd, And added more, whereby thou are more graced?

Chaucer

The self-same Man who hath no Labour spar'd To help what Time and Writers had defaced:

And made old Words, which were unknown of many, So plain, that now they may be known of any.

Reader

Well fare his heart; I love him for thy sake, Who for thy sake hath taken all this Pains.

Chaucer

Would God I knew some means amends to make, That for his Toil he might receive some Gains.

But wot ye what ? I know his Kindness such, That for my good he thinks no Pains too much.58

Chaucer's liveliness here, like his liveliness in the protodramas, comes

from his voice rather than, in Hoccleve's case, his likeness. In the high

value folio edition, however, self-conscious printers' metaphors layer the

work of editors, parents, and readers to let Chaucer's liveliness answer

print's status as

commodity.

Speght's 1602 edition includes two more poems that animate Chaucer.

Written by Francis Thynne, son of the editor William, the first poem closes

with lines attuned to the trope of a living Chaucer: "Then Chaucer live, for

still thy Verse shall live / T'unborn Poets which Life and Light will give."59

58. Transcribed from the University of Oregon's copy of Speght's edition (see n. 2). Trigg,

Congenial Souls, prints a final couplet: "And more than that; if he had knowne in time, / He

would have left no fault in prose nor rime" (p. 133). 59

Upon the Picture of Chaucer.

What Pallas City owes the heavenly mind

Of prudent Socrates, wise Greece's Glory; What Fame Arpi?as spreadingly doth find

What lasting Praise sharp witted Italy By Tasso's and by Petrark's Pen obtained;

What Fame Barias unto proud France hath gained;

By seven days World Poetically strained:

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

354 Bishop

Even more insistently, Thynne's second poem, "Of the Animadversions

upon Chaucer," uses, like the dialogue poem from the earlier Speght edition, the trope of Chaucer's living fatherhood while gesturing toward

print and editorship:

In reading of the learn'd praise-worthy Pain, The helpful Notes explaining Chaucer's Mind, The abstruse Skill, and artificial Vein;

By true Annalogy I rightly find

Speght is the Child of Chaucers fruitful Brain; Vernishing his Works with Life and Grace,

Which envious Age would otherwise deface.

Then be he lov'd and thanked for the same,

Since in his Love he hath reviv'd his Name.60

In this poem, Speght becomes the "vernisher" of Chaucer's works, coating and rubbing to warm and enliven. Both the Reader and Francis Thynne aver that Chaucer, the living father-artist, "really"

comes to life in the edi

tion of his child, Thomas Speght. Speght includes these poems of Francis

Thynne, son of William, Chaucer's first folio editor, with a conscious nod to

filial pieties, his to Chaucer and Francis's to his father. The elder Thynne's and Chaucer's entanglements with the Tudor family seem background here: Speght prints Francis's "Animadversions" as peritexts in which Francis

details his father's contretemps with Cardinal Wolsey.61 Yet Speght brings his own Tudor entanglements to bear, printing his dedicatory epistle to

Elizabeth's secretary, "Sir Robert Cecil, one of hir highnes most honvrable

privie covnsel," as first peritext in the edition. The edition's numerous

peritexts surround Chaucer with the earliest and latest Tudor history.

What high Renown is purchas'd unto Spain, Which fresh Dianaes Verses do distill; What Praise our Neighbour Scotland doth retain

By Gawine Douglas, in his Virgil Quill; Or other Motions by sweet Poets Skill; The same, and more, fair England challenge may,

By that rare Wit and Art thou do'st display In Verse, which doth Apollos Muse bewray.

Then Chaucer live, for still thy Verse shall live

T'unborn Poets which Life and Light will give. Fran. Thynn.

See Francis Thynne's Animadversions, pp. cvi-cvii. The poem appears in the University of

Oregon's edition of Speght (see n. 2 above), on a 1 verso.

60. Francis Thynne's Animadversions, p. cvii. 61. Despite Henry VIII's assurances, "my father was called in questione by the Bysshoppes,

and heaved at by cardinall Wolseye, his olde enymye, for manye causes, but mostly for that

my father had furthered Skelton to publishe his 'Collen Cloute' againste the Cardinall"; Francis Thynne's Animadversions, p. io.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 355

The most striking of Speght's new peritexts is, as in Thynne's 1532 Jesse tree illustration, a visual one. New to Speght's 1598 edition of Chaucer's

Works, it pictures Chaucer full length, standing in a position similar to that

of both the portrait painted in 1556 over Chaucer's Westminster tomb

and the illumination in the Hoccleve manuscript (fig. 2).62 By including both Chaucer's image and his genealogy, the image goes one step further

than Stow's Canterbury Tales title page?which Speght uses in 1598 and

rejects in 1602?to fold Chaucer into Tudor hegemony. Not only regularly

reprinted but actually pasted into copies of Stow's edition, this woodcut, or "momentous talisman," is entitled "The Progenie of Geffrey Chaucer."63

Like the engraving of Henry Vffl's lineage used to title The Canterbury Tales, this peritext layers Chaucer with Tudors. Drawn by John Speed, it portrays two families, royal and Chaucerian: Chaucer's daughter ends up, by dint

of marriage, ennobled. In contrast to the earlier woodcut, generations run down, rather than up, this illustration's sides so that John of Gaunt's

name parallels Chaucer's in a roundel atop the illustration, rather than

at its bottom.

Since the image details the entry of Chaucer's children into the no

bility, it includes, on its left-hand side, a version of the royal genealogy

depicted in the earlier woodcut. In

Speed's version, however, the gene

alogy of Henry VII, the first Tudor king, contains five female forbears,

including Henry's mother Margaret Beaufort, and nearly doubles the

number of female forbears shown in the earlier woodcut. Not only that,

but Chaucer's own family tree, on the image's right-hand side, includes

four women, including the poet's wife, making for a total of nine women,

rather than the three appearing in the earlier woodcut and, interest

ingly, in traditional images of a Jesse tree.64 In these two ways Speed's illustration provides

more space for generative women than does the

earlier woodcut?and does so in the waning years of Elizabeth's reign. The

choice to include more women may allude to an opinion,

current in the

sixteenth century, that Chaucer was particularly sympathetic

to women.65

62. Driver, "Mapping Chaucer," p. 241, infers a different portrait as Speed's source: a late

sixteenth-century portrait found in British Library, MS Additional 5141; for the image, p.

242.

63. The phrase "momentous talisman" is John R. Hetherington's, Chaucer 1532?1602, Notes and Facsimile Texts Designed to Facilitate the Identification of Defective Copies of the Black-Let

ter Folio Editions of 1532, 1542 c. 1550, 1561, 1598 and 1602 (Birmingham, England: John R. Hetherington [privately published], 1964), p. 7. The engraving is treated in Arthur M.

Hind, Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: A Descriptive Catalogue with Introductions, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1952), pp. 286-89.

64. I thank James W. Earl for this insight into the Tudor tree's imitation of religious

iconography. 65. "Excuse Chaucer . . . for he was euer god wate, all womannis freynd," from Gavin

Douglas's translation of Virgil's Aeneid (Spurgeon dates the manuscript version 1513, Boswell

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

"H .. ?1 ..__. ... i g

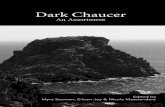

Figure 2. The works of

our ancient, learned, ?? excellent

English poet, feffrey Chaucer : as they have lately been

compared with the best manuscripts, and several things

added, never before in print : to which is adjoyn 'd, The

story of the siege of Thebes, by fohn Lydgate, monk of Bury :

together with the life of Chaucer, shewing his countrey,

parentage, education, marriage, children, revenues, ser

vice, reward, friends, books, death : also a table, wherein

the old and obscure words in Chaucer are explained, and

such words (which are many) that either are, by nature

or derivation, Arabick, Greek, Latine, Italian, French,

Dutch, or Saxon, mark'd with particular notes for the bet

ter understanding their original. London: n. p., 1687.

Folio 2, verso. By kind permission of James Fox,

head, special collections, Knight Library, University

of Oregon.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 357

Or it may, through a subtle analogy with Elizabeth's own

strategies, make

Chaucer the paternal vernacular poet of the mother tongue, metaphori

cally both father and mother,66 even as it represents Chaucer's fecundity and progeny. The "Progenie" illustration puts "father Chaucer" squarely into English history, mapping the familial affiliations of Chaucer, from

wife to great-great-grandson, onto royal lineage.

But this image does more. The bottom of the image shows the tomb

of the poet's son, Thomas, and his wife, Maud. Yet Chaucer stands up

right in the illustration's center atop his son and daughter-in-law's tomb,

his posture genially defying death. Making Chaucer's image central in a

full-length, authoritative portrait subtly suggests, on the model of Henry VIII?a monarch famously obsessed with progeny?Chaucer

as father.

But the roundels on the image's right side?Chaucer's line?end with

great-great-grandson Edmund De la Pole, whom Henry VIII had be

headed in 1513.67 Living father Chaucer atop his children's tomb flanked

by his extinguished line cannot help but remark on a childless queen

Elizabeth?increasingly controlling press and pamphlet?and the "liv

ing" nature of print, overcoming both commodification and censorship.

Speed says his image of Chaucer comes not from the image on Chaucer's

tomb but from Hoccleve, Chaucer's scholar.68 Speed invokes manuscript to gesture towards those once-living books, the "haulks and herns" of

the forest primeval in which manuscript Chaucer formerly resided.

But the gesture also brings to light what's lost between manuscript and

print. Speed's image, based on Hoccleve, brings manuscript life to the

printed book and living Chaucer to many readers, undoubtedly more

readers than Hoccleve's manuscripts had: it can even affect "readers"

and Holton date the printed version 1553); "Chaucer, how miscaried thy golden pen?" with a side note "Chaucer, lib. faeminarum encomion.I.& alterum, de laudib.bonarum.faeminar,"

William Heale, from An Apologie for Women (1609). Lerer, Chaucer and His Readers, p. 282, n. 14, states that "Chaucer himself stages a critique of patriarchal (and, for that matter, heterosexualist) authority in his fictions." But see also Elaine Tuttle Hansen, Chaucer and the Fictions of Gender (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1992), for important qualifications

of this view. 66. Roy Strong, The Cult of Elizabeth (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1977), esp. pp.

16,69. 67. Pearsall, Life, p. 284. 68. See above, note 62. Speght contends that the portrait on Chaucer's tomb also comes

from the image in the Hoccleve manuscript; see Dane, Who Is Buried, p. 13: "M. Nicholas

Brigham did at his owne cost and charges erect a faire marble monument for him, with his picture, resembling that done by Occleve." Ashmole, whose Theatrum first published an

image of the tomb, credits Hoccleve's image as guide for the tomb painting's restoration, which leads Pearsall to consider Speght's peritext the restorer's real inspiration (Pearsall,

Life, p. 296). But, as Pearsall also points out, "Speght's picture [i.e., Speed's engraving] itself of course derived from the tradition of which the original tomb portrait may have been an

important early ancestor" (p. 296).

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

358 Bishop

of Chaucer's Westminster tomb. Chaucer's generative power is simulta

neously historical, literary, royal, legitimate, doubly gendered, artistic,

and living. It subtly challenges both live queen and dead print. Life and art atop the obverse face of generation?death?answers print's dead

letter. The peritext puts on one page, with image instead of the words

Bullein and Greene put in living Chaucer's mouth, a challenge to the Tudor regime of letters.

This image well deserves its epithet "a momentous talisman": although new to Speght's 1598 edition, the image was pasted into copies of Stow's

1561 edition, including one now in the Huntington library. Unlike the

previously discussed peritext of Henry's lineage, which, perhaps because of its troublesome content, was excised from reprints of Speght's edition

beginning in 1602, this second peritext continues to be printed in both the 1602 and 1687 folio Chaucers. These two reprints of Speght, nearly

a century apart, are, however, the only editions of Chaucer published in

the seventeenth century: John Urry's 1721 folio Chaucer edition replaces Speed's engraving with "a bust in oval" to depict the poet?and a portrait of Urry himself, sign of modern criticism's advent, precedes both it and the book's title page.69

Read together, Speght's three peritextual poems?the dialogue poem and the two by Francis Thynne?and Speed's engraving animate Chau cer and laud his editors, whose efforts come, not from the desire to

profit from their commodified books, but from kindness and love and

family devotion.70 But in Speght's editions, peritexts voice Chaucer and

Reader, warm Chaucer to life, and show him atop a tomb to give life to the Chaucer who appears in other printed matter. The concert of

these peritexts, late in Elizabeth's reign, enlivens and revoices father

Chaucer. Tracing Chaucer's fatherly liveliness through the sixteenth

century tracks Tudor politics' interp?n?tration with print. Speght's edi tion makes Chaucer's fatherly liveliness not

only an answer to

print's commodification but a comment?or

warning?upon print's conjuga tion with authority. Editors, engravers, and dialogists?Speght, Speed,

Bullein, Greene, Brathwait?meet multiple needs in making Gascoigne's

and the Cobler's father Chaucer live.

6g. Hind, Engraving in England, I, 287, notes the "bust in oval"; the University of Oregon's copy of Urry's Chaucer, Special Collections Rare Books PR 1850.1721, has a full-page en

graving of Urry facing the edition's title page, the bottom of which shows Chaucer's tomb.

Driver, "Mapping Chaucer," p. 239, and Dane, Who Is Buried, p. 24, both provide images of

Urry's title page. On Urry's edition, see William Alderson, Editing Chaucer, ed. Ruggiers, pp. 93-115

70. See Trigg, Congenial Souls.

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print 359

Images situate Chaucer as father, showing him with his progeny. Such

repetitions of Chaucer's living fatherhood reverse the "childhood" trope Lerer outlines for early print culture,71 and make Chaucer the father

rather than a child. Read in tandem with the woodcut of Henry VIII's

forebears, Speght's image hopes to evoke Chaucer's presence, his "aura,"

on the page. Such images, despite Lerer's denials, can "conjure [Chau

cer's] discerning visage" not

only over the "impersonator's shoulder," but

over the reader's.72 An aura of masculine generative power defines print

culture's Chaucer and parallels Chaucer's generative success with the

ruling families of York, Lancaster, and Tudor. Repetition of Chaucer's liv

ing fatherhood also makes visible print's new mode of "genetic relations

among texts and of textual history itself as a form of familial relations."73

Aura-making woodcuts in sixteenth-century editions of Chaucer picture

his fatherhood allied with royal authority: Chaucer's fecundity extends

from progeny to printed

text. Chaucer editions' images, powered by

royal concerns, make Chaucer not the "dead auctor" Lerer describes,74

but a living poet. The motif recurs in sixteenth-century prose and po

etry, along with Chaucer editions' images, to satisfy both national and

patriarchal desires, all framed by Chaucer's living fatherhood.

Ill

Late sixteenth-century print and theater complement each other in their

concern with legitimacy and authority, paternity, and nation.75 Theater

can take the idiom of "living" beyond that which print can accomplish

through inert picture and word.76 As far as the plays of Shakespeare are

concerned, a living, breathing Chaucer?desired by Bullein, Greene, and

Brathwait, and invoked in early Chaucer editions' peritexts?does not

appear. We get close: Chaucer's contemporary Gower acts as chorus in

Shakespeare's late romance Pericles, and the "Prologue" figure opening

The Two Noble Kinsmen repeats Chaucer's underground cry,

71. Lerer, Chaucer and His Readers, p. 18.

72. Lerer, Chaucer and His Readers, p. 151.

73. Lerer, Chaucer and His Readers, p. 167.

74. Lerer, Chaucer and His Readers, p. 19.

75. Valerie Traub, Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakespearean Drama (Lon don: Routledge, 1992); Gordon Williams, Shakespeare, Sex, and the Print Revolution (London:

Athlone, 1996).

76. Cf. Benjamin, "The Work of Art," pp. 231-32: "Aura is tied to presence . . . there is

indeed no greater contrast than that of the stage play to a work of art that is . . . founded

in mechanical reproduction."

This content downloaded from 128.223.86.31 on Mon, 13 Apr 2015 10:32:43 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

360 Bishop

". . . O, fan

From me the witless chaff of such a writer

That blasts my bays and my fam'd works makes lighter Than Robin Hood!"77

But even here Shakespeare is absent: critics attribute this prologue to

Shakespeare's collaborator, John Fletcher.

Without a literal stage, Speght's living father Chaucer still adds a new

interpretive dimension to Chaucer's text through another feature of early

print Canterbury Tales. From Caxton through Speght, the conventional

printing of The Tale of Melibee makes that tale most fully Chaucer's own.

The pilgrim Chaucer tells two tales on the road to Canterbury, according to the Tales' frame narrative: one of Sir Thopas, and one of Melibee and his

wife Prudence. Early and modern editions treat the two tales quite differ

ently. Chaucer's name graces neither author-told tale in modern editions: