Eleanor of Aquitaine: 20th & 21st century approaches

Transcript of Eleanor of Aquitaine: 20th & 21st century approaches

1

How have 20th and 21st Century historians

portrayed Eleanor of Aquitaine?

Introduction

Eleanor has in fact inspired some of the very worst historical writing devoted to

the European Middle Ages. Adopted as a figurehead by literary romantics, and

more recently by feminist historians, the Eleanor of history has been

overshadowed by an Eleanor of wishful-thinking and make-believe.1

Eleanor of Aquitaine holds a unique place in Anglo-Norman

history as the only woman to be both Queen of France and Queen

of England in a remarkable life spanning over eight decades.

She bore ten children, two of whom would be Kings of England

and outlived all but two of them. Yet this long and very

public life has been almost eclipsed by myths over the eight

centuries since her death.2 This essay will explore how modern

historians depict Eleanor, whether her portrayal is favourable

or not and if there are points upon which historians agree or

disagree. Whilst this essay will not refer to the sources

which modern historians have utilised to reach their

conclusions, it will consider the interpretation of such

sources with a view to understanding why this woman retains a

persistent appeal. Furthermore, this essay will focus upon

historians whose works are published in English, although

1 N. Vincent, ‘Patronage, Politics and Piety in the Charters of Eleanor of Aquitaine (c.1122-1204)’, M. Aurell and N-Y. Tonnerre (eds.), Plantagenets et Capetiens: confrontations et heritages (Turnhout, 2006), p.172 G. Duby, Women of the Twelfth Century Vol. 1, Eleanor of Aquitaine & 6 others (Cambridge, 1997), p.8

C1161252

2

reference will be made to French historians where translations

are available.

Much of what has been written about Eleanor has come from

sources which have little or no first-hand knowledge of the

lady or her actions; they are reliant upon information

gathered from others. Elizabeth Van Houts divides such

information into seven categories for easier analysis; where

category one is direct personal experience and seven relates

to events ‘so distant in time and place from the writer that

he gives them little positive credence’.3 Surviving records

from the Twelfth and Thirteenth centuries are limited in

number and comprise chronicles and memoires written by

churchmen and courtiers, governmental charters, legal

documents and private letters. Scott Hahn states the role of

the chronicler was not to report history as it happened but to

interpret the deeds of history as a way of providing their

readers with spiritual guidance in an uncertain world.4

Therefore the actual events taking place are not as important

as the message being passed on to the reader, which Gabrielle

Spiegel suggests was heavy with social, religious and

political ideals.5

The power of myth in historical writing lies in this ability

to alter events to fit a particular ideology, which itself can3 E.M.C. Van Houts, Memory and Gender in Medieval Europe, 900-1200, (Basingstoke, 1999), p.204 S.W. Hahn, The Kingdom of God as Liturgical Empire: A Theological Commentary on 1-2 Chronicles,(Grand Rapids, 2012), p.75 G.M. Spiegel, Romancing the Past: The Rise of Vernacular Prose Historiography in Thirteenth Century France, (London, 1993), p.5

C1161252

3

change dependent upon socio-political factors. The myths

surrounding Eleanor are primarily of a negative nature

resulting in the blackening of her name and reputation and

overshadowing what she did and why.6

Introducing Eleanor

Eleanor was born in 1122, the eldest child of William X Duke

of Aquitaine and she inherited the Duchy in April 1137 upon

his death, making her one of the richest and most desirable

6 P. McCracken, ‘Scandalizing Desire: Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Chroniclers’ in B. Wheeler and J.C. Parsons (eds.) Eleanor of Aquitaine: Lord and Lady, (Basingstoke, 2002), p.247

C1161252

Figure 1: Map of 12th Century France showing possessions and vassalsof French King and Angevinswww.vivamost.comAccessed: 4 Mar 2014

4

heiresses in Europe. She married the future Louis VII of

France on 25th July 1137 to ensure the extensive lands of

Aquitaine fell under the control of the French crown and

became Queen of France on 1st August aged 15. Over the next 15

years she bore two daughters and took the cross from Pope

Eugenius III to accompany her husband on Crusade to the Holy

Land between 1147-9. Sadly this was not a happy union and the

couple sought a divorce on the grounds of consanguity, citing

their shared ancestry (great, great, great grandparents King

Robert the Pious of France and his wife Constance of Arles),

an annulment was granted in March 1152.

On 18th May 1152 Eleanor married Henry of Anjou, eleven years

her junior and transferred the Duchy of Aquitaine from Louis

to Henry. Upon Henry’s succession to the throne of England in

1154, Eleanor became Queen. She provided Henry with five sons,

four of which survived to adulthood and three daughters. This

was a fiery relationship but the marriage continued until

Henry died in 1189. She supported and guided her son Richard

as both Duke of Aquitaine and King of England, acting as

regent in his absence. She retired to Fontevraud Abbey in 1194

but came out of retirement to help secure the succession for

John in 1199. She died on 31st March 1204 and was buried at

Fontevraud alongside Henry, her son Richard and daughter Joan.7

7 J. Martindale, ‘Eleanor, suo jure duchess of Aquitaine (c.1122-1204)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn., May 2006 [www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/8618, accessed 23 Jan 2014

C1161252

5

The fabric of Eleanor’s life has proved popular in modern

media combining a romantic and historical appeal, casting

Eleanor as the consort of two Kings who went on crusade whilst

pursuing her personal ambitions for power in a man’s world.

However, those very attributes that filmmakers and writers of

romantic fiction relish (the whiff of scandal, her headstrong

ambition, passionate spirit and desire to confront and change

circumstances which are not to her liking) are those which

Twelfth century commentators found unsavoury in a Queen and

lady of Eleanor’s stature. The defamation of Eleanor’s name

began during her lifetime when gossip circulated regarding her

improper relationships with male acquaintances alongside

whispers of conduct unbecoming to a Queen and lady.

Twelfth and Thirteenth century chroniclers who wrote about

Eleanor like William of Tyre, John of Salisbury, Matthew

Paris, Helinand de Froidment and Aubri des Trois Fontaines

were all men of the church who had to rely upon ‘the common

C1161252

Figure 2: Katherine Hepburn as ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine’ in 1968 film The Lion in Winter http://thegreatkh.blogspot.co.ukAccessed: 7 April 2014

6

talk of the day for their knowledge of public affairs’.8 This

resulted in unsubstantiated rumour and hearsay becoming a

written record of the time and used by later writers and

historians as the basis upon which their analysis and

observations of Eleanor are built.

Biographers and Historians

There have been many books written about Eleanor over the last

century, by esteemed historians and non-academics alike that

provide their own insight. Even historians who write about

other family members family or key figures of the day (John

Gillingham and Wilfred Warren to name but two), find

themselves exploring Eleanor to gain an insight into their

chosen subject. Whilst both historians and biographers

undertake research on their chosen subject, the publication of

this research by a historian carries a higher degree of

scholarly prestige than that of the biographer; primarily

because academic research is examined far more critically upon

publication than popular biographies, which tend to have a

different audience. Jean Flori clearly sets out his opinion by

declaring ‘it may be alright for the general public to like

historical novels, but it is not right for historians to

novelise history’.9

8 R. Fawtier, The Capetian Kings of France: Monarchy and Nation 987-1328, trans. L. Butler & R.J. Adam (London, 1960), p.6. R. Barber, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Media’ in M. Bull and C. Leglu (eds.), The World of Eleanor of Aquitaine: literature and society in southern France between eleventh and thirteenth centuries (Woodbridge, 2005), pp.13-279 J. Flori, (trans. O. Classe), Eleanor of Aquitaine: queen and rebel (Edinburgh, 2007), p.12

C1161252

7

The real question is whether there is a place for biographies

alongside the more academic historiography in portraying

Eleanor; in much the same way as Thucydides (the historian)

and Plutarch (the biographer), themselves separated by eight

hundred years, describe aspects of Greek characters like

Alcibiades, modern biographies can provide valuable material.

Ann Kelly produced the first modern biographical account of

Eleanor’s life in the 1950’s, which took twenty years to

research and write and relies upon recognised sources. Whilst

this biography makes no historical comment and paints a

romantic and fanciful picture of Eleanor, bestowing upon her a

personality that the sources cannot substantiate, Kelly’s

work, and that of other biographers like Marion Meade and

Alison Weir, are of benefit to modern historians in building

up a picture of Eleanor. For the modern historian utilising

primary sources requires a level of care to appreciate any

influence which may underpin the writers work; this same

principal can be applied to biographies to expunge the layers

of embellishment from the raw material underneath.

Queenship in the Medieval Period

As Queen of France and then of England, Eleanor was expected

to fulfil a certain role which has been subject to intense

study relatively recently. Theresa Earenfight describes

medieval Queenship as ‘inherently ambiguous’ and ‘privileged

but oppressed’; a Queen was a public figure with no real

political status or power, whose primary function was to

provide a male heir.10 Whilst Eleanor may have failed to 10 T. Earenfight, Queenship in Medieval Europe (Basingstoke, 2013), p.27

C1161252

8

provide Louis with that heir, she certainly fulfilled such a

role for Henry. Elena Woodacre expands upon this and states

that the Queen’s political role was defined by her personal

relationship with the King; the stronger the bond between the

spouses, the greater the possibility for the queen to exercise

some form of political power.11 Whilst married to Louis, there

is little evidence to show that Eleanor wielded any authority

in her own right as only a small number of charters from

Aquitaine remain all of which were issued jointly with Louis.12

However, when married to Henry she acted as regent during his

absence and issued charters under her own name and seal in

Aquitaine, which if Woodacre’s analysis is applied, suggests

that the relationship between Henry and Eleanor was stronger

than between Louis and Eleanor.

Conversely Lisa Hilton argues that Eleanor was a young and

inexperienced girl when married to Louis, unfamiliar with the

ways of French government, treated with disdain for her

‘southern’ background and found no place for her to fill

politically as Louis had inherited his father’s trusted

advisors. By the time she married Henry she was a thirty year

old woman, experienced in the machinations of royal rule and

capable of keeping the wheels of government in motion.13

Eleanor’s Political Power and Authority

11 E. Woodacre (ed.), ‘Introduction’, Queenship in the Mediterranean: Negotiating the Role of the Queen in the Medieval and Early Modern Eras (Basingstoke, 2013), p.312 H.G. Richardson, ‘The Letters and Charters of Eleanor of Aquitaine’, English Historical Review 74 (1959), pp.209-1113 L. Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens (London, 2008), ch.5

C1161252

9

Modern sources agree that Eleanor’s marriage to Louis was for

dynastic purposes to ensure the duchy of Aquitaine fell under

the direct control of the King of France. As mentioned above

there is little evidence to substantiate Eleanor’s power and

authority as Queen of France; Earenfight points out that only

two hundred charters issued by Eleanor during her lifetime

survive to the modern day and twenty were issued by her during

her marriage to Louis.14 In direct contrast Marion Facinger

states that Louis’ mother, Adelaide of Savoy, was more

politically active with her name appearing alongside her

husband’s in forty five charters, but more significantly is

that Adelaide’s regnal year appears with her husband’s in

royal acts for the first time in Capetian regal history.15

Whilst the power and authority of these two Queens of France

is open to interpretation, the lack of evidence to the

contrary suggests that Eleanor fulfilled the role of King’s

consort as was required of her without expressly exercising

political authority. Parsons and Wheeler suggest that if the

consorts name is absent from the witness list, does this prove

that they played no part in the counsel and administration or

could their role be more of a ‘sleeping’ partner?16

14 Earenfight, Queenship, pp.137-915 M.F. Facinger, ‘A Study of Medieval Queenship: Capetian France 987-1237’,Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, 5 (1968), pp.3-4716B. Wheeler and J.C. Parsons (eds.), Eleanor of Aquitaine. Lord and Lady (Basingstoke, 2002), p.xxiii

C1161252

10

As Henry’s Queen, Eleanor served as regent in England during

his many absences and Donald Seward points out that Eleanor

‘dispensed justice, arbitrated disputes over land and feudal

dues and presided over law courts’, emphasising the key to

understanding her personal character and political ambitions

is her thirst for power.17 Turner also states that between

1152-4, Eleanor played the primary role in governing

Aquitaine; which changed in December 1154 when Henry became

King of England as her responsibilities widened, compounded by

her near constant state of pregnancy.18 She returned to take up

the reins of power in Poitou in 1168, although Henry kept the

essential elements of military force and money under his

control, which undermined the real power she held in her duchy

and probably contributed to her role in the ‘Great Rebellion’

of 1173.

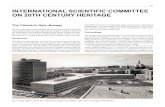

Modern historians concur that Eleanor’s regency of England

after Henry’s death in 1189 and Richard’s absence on crusade

provided her with the power and authority she had wanted for

17D. Seward, Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Mother Queen (London, 1978), p.8518R.V. Turner, Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England (New Haven and London, 2009) p.175

C1161252

Figure 3: The obverse seal of Eleanor Eleanor By the Grace of God, Queen of theEnglish, Duchess of the Normanshttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:EleanorAkvitanie1068.jpgAccessed 11 Apr 2014

11

so long and she dedicated her energies to preserving her son’s

authority.19 Despite being in her seventies, she dealt with

John’s attempts to usurp power and kept Phillip of France at

bay as well as the routine administration of the land.20. She

also oversaw the collection and delivery of Richard’s ransom

when he was taken prisoner en route from Jerusalem, provided

him with counsel to finalise his release and accompanied him

home from Germany.21 As dowager queen mother her talents were

required again in 1199 to secure the throne for John. While

John worked to secure England and Normandy, Eleanor tirelessly

toured her duchy of Aquitaine, dispensing favours to her

barons and demanding fealty to John through her; to emphasise

her authority she paid homage to Phillip of France as overlord

of her duchy of Aquitaine, something from which women were

routinely excluded.22

Myths and Legends

I. Eleanor the Adulteress

The first protracted whiff of scandal to attach itself to

Eleanor concerned her relationship with her uncle Raymond of

Antioch during her time in the Holy Land on crusade.

Historians differ in their opinions on this subject, with some

19 R.V. Turner, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine in the Governments of her Sons Richard& John’, in Wheeler & Parsons, Eleanor, p.7820 H. Castor, She Wolves: the Women who Ruled England before Elizabeth, (London, 2010), p.19221 J. Gillingham, The Angevin Empire, (London, 2001), p.4522 W.L. Warren, King John, (Berkeley, 1978), p.51Castor, She Wolves, p.214

C1161252

12

rejecting the idea as pure fabrication, whilst others hint

that there ‘is no smoke without fire’. While Ralph Turner does

not proffer an outright opinion on this episode, he concludes

that the absence of evidence suggests that these accusations

were baseless.23 Flori states that Eleanor’s behaviour in

Antioch both on a personal and political level provided the

foundation for the rumours. He suggests that she is at fault

by allowing (or seeking) private audiences with Raymond,

regardless of what they were discussing, and by refusing to

leave Antioch when Louis demanded it of her.24 The first of

these attracted the suspicion of her husband, while the second

was an outright challenge to his authority, both as his wife

and his subject.

Eleanor’s behaviour is the causation of the chasm in her

marriage to Louis, which spawned many rumours most notably

accusations of adultery with Raymond and others, including a

Saracen warrior (name by Matthew Paris as Saladin – although

he would have been aged eleven at the time of such an

affair).25 Thus the die was cast and gossip gathered pace,

painting Eleanor as the disrespectful wife, who was capable of

not only iniquitous behaviour towards her husband but

immorality with other men under his very nose. The list of her

supposed lovers grew, including French noble men (even her

future father-in-law Geoffrey of Anjou) and the Troubadour

Bernart de Ventadour. Douglas Owen states that Eleanor 23 Turner, Eleanor, p.30624 Flori, Eleanor, p.22725 McCracken, ‘Scandalising Desire: Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Chroniclers’ in Wheeler & Parsons, Eleanor, p.247-50

C1161252

13

‘attracted legend to herself like a magnet’ and the most

innocent of activities would give rise to speculative rumour;

her character was already blackened so attaching more

accusations to her was a simple task.26

Interestingly, modern historians concur that there is no

evidence of any new allegations of adultery after Eleanor’s

marriage to Henry; such accusations appear to be limited to

her time as Queen of France.27

II. Eleanor the Amazon Warrior

Frank Chambers’ Speculum article refers to a Seventeenth

century work by Isaac de Larrey which depicts Eleanor in full

armour leading a regiment of ‘Amazon’ warriors into battle

alongside their husbands.28 Although this is a story full of

imagery there is no corroborating evidence and historians

agree that it is without foundation but the stories have been

repeated countless times. The Amazonian myth features in

almost every historical representation of Eleanor; Seward,

writing in 1978, adds a story of Eleanor jousting with her

ladies to the traditional tale.29 Christopher Daniell suggests

that this myth highlighted how status and wealth freed noble

26 D.D.R. Owen, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Queen and Legend (Oxford U.K. and Cambridge Mass., 1993), p.10727 Seward, Eleanor, p.10928 F.M. Chambers, ‘Some Legends concerning Eleanor of Aquitaine’, Speculum 16(1941), pp. 460-129 Owen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, pp. 150-1Seward, Eleanor, p.44

C1161252

14

women from social constraints so they could accompany their

men of Crusade.30

Whilst the ‘Amazon’ stories are retold by modern historians,

there seems to be a general consensus that they are just tall

tales. Realistically Eleanor’s security would have been

paramount to Louis as she would be expected to provide his

future heir so there would be no possibility of her being

close to any fighting. Additionally commentary by modern

historians highlight how much of an inconvenience it was to

Louis’ army having ladies, maidservants and their baggage on

campaign, particularly when a crusading army was expected to

be chaste.31

III.Matriarch of the Devil’s Brood

Martin Aurell remarks that Henry, Eleanor and their numerous

offspring were in constant conflict with each other,

culminating in the rebellion of 1173 when Henry the Young

King, Richard and Geoffrey, supported by Eleanor, rose up

against Henry II.32 This was not a small family disagreement

but a bitter, smouldering hatred remarked upon by both Walter

Map and Gerald of Wales, even St Bernard of Clairvaux decried

‘From the devil they come, and to the Devil they will return’

when describing the family.33

30 C. Daniell, From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta: England 1066–1215, (Abingdon, 2003), p.9231 Chambers, ‘Some Legends’, p.45932 M. Aurell, D. Crouch (trans.), The Plantagenet Empire 1154-1224 (Harlow, 2007),p.3533 Warren, King John, p.2

C1161252

15

The tale of Melusine the she-devil, as told by Gerald of

Wales, appears in most modern academic or biographical

publications, used as an explanation of why the Angevins

behaved the way they did. The belief that the Counts of Anjou

were descendants of the devil, hence the title Devil’s Brood,

suggests their very nature was one of turmoil and bloodshed;

although interestingly, Melusine is cast as an ancestor of

Henry not Eleanor.34 Four sons all competing for a taste of

power, together with a father unwillingly to relinquish any

part of that power culminates in a melting pot of desperation

and ambition; not a recipe for family cohesion especially when

compared to the relative harmony of the Capetiens in France.

Robert Chapman refers to a thirteenth century work entitled

Richard Coure de Lion, in which the hero’s mother, Cassodorien, is

referred to as a ‘Demon Queen’; whilst Eleanor is not named,

there is little doubt as to whom the writer is describing. It

is not unusual for heroic figures to be given supernatural

parentage (Alexander the Great, Merlin, etc.), but it is

highly unusual for a recently deceased historical monarch to

be given demonic parentage especially as Eleanor had been dead

less than fifty years when the piece was written.35 No evidence

shows how and why this tale became attached to Eleanor but the

very fact it existed at all is evidence of the powerful hold

she had on the imagination of her age.

34 D. Power, ‘Stripping of a Queen: Eleanor in 13th Century Norman Tradition’, in Bull and Leglu, The world of Eleanor of Aquitaine, p.13135 R.L. Chapman, ‘A Note on the Demon Queen Eleanor’, Modern Languages Notes, vol.LXX, no.6, June 1955

C1161252

16

IV. Eleanor the Murderess

This particular myth refers to the suggested murder of Henry’s

long-time mistress Rosamond Clifford, whom he openly lived

with during Eleanor’s imprisonment after the failed rebellion

of 1173. Given the nature of the arrangement, it would seem

reasonable for sympathies to lie with Eleanor as the wronged

party but this myth clearly shows the depth of enmity towards

Eleanor when she is cited as responsible for Rosamond’s death

in 1176. There is no evidence to suggest that Rosamond’s death

was by foul means, nor that Eleanor had any link other than as

an imprisoned, distant observer. This myth is summarily

dismissed by modern writers as pure fabrication; Weir and Owen

both assert that even the suggestion of a ‘competition’

between Eleanor and Rosamond for Henry’s affection should be

greeted with derision.36

Hilton writes that a King was not expected to be faithful to

his consort, whose primary role was to bear his children;

36 A. Weir, Eleanor of Aquitaine: by the wrath of God, Queen of England (London, 2007), p.225Owen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, p.115

C1161252

Figure4: Queen Eleanor byFrederick Sandys (1858), National Museum of Wales,Cardiffhttps://www.pinterest.com/marythegator/frederick-sandys/Accessed 11 Apr 2014

17

Eleanor’s grandfather, the ‘troubadour’ Duke William IX of

Aquitaine lived a colourful private life and even married his

son to the daughter of his favourite mistress.37 Turner states

that being twelve years Eleanor’s junior, Henry would have

been expected to have lovers; a similar situation took place

with his parents, as Matilda was eleven years older than

Geoffrey. Kelly backs this up with specific reference to Henry

and his appetites, declaring that Eleanor ‘averted her eyes’

from the king’s lustful adventures and was in no position to

complain or take action against someone who had caught the

King’s eye.38

Aquitanian Culture and Patronage of Troubadours

The Duchy of Aquitaine in the twelfth century was considered

an attractive acquisition for Franco-Anglo-Norman royalty but

whilst vast in size, it was extremely difficult to govern;

Jane Martindale remarks that any form of cohesive government

in the duchy was almost impossible to maintain.39 However, this

southern region had a thriving creative culture, together with

a distinctive dialect Occitan or langue d’oc and Eleanor’s

childhood home at Poitiers is cited by numerous writers for

its patronage of troubadour poetry, as is her grandfather

William IX for his lyrical compositions.40

37 Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens, ch.538 A. Kelly, Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings (Cambridge Massachusetts and London, 1950), pp.150/239 J. Martindale, Status, Authority and Regional Power (Aldershot: Variorum, 1997), ch. XI, p.2540 E.M. Hallam & J. Everard, Capetian France 987-1328, (Harlow, 2001), p.727. D. Hilliam, Eleanor of Aquitaine: the Richest Queen in Medieval Europe, (New York, 2005), p.8-9

C1161252

18

Polly Schoyer Brooks, Moshe Lazar and Simon Schama are among

those writers supporting Eleanor’s position as patron of the

troubadours and cite the work of Bernart de Ventadorn (amongst

others) as evidence, particularly his poem ‘Huguet, my courtly

messenger, sing my song eagerly to the queen of the Normans’

believed to refer to Eleanor.41 Ruth Harvey provides a detailed

analysis of Eleanor’s supposed enthusiasm and patronage of the

troubadour culture and concludes that her role has been

overstated and was merely supportive of the rich Occitan

literary tradition that already existed in Aquitaine.42 The

evidence to support Eleanor’s patronage is limited and subject

to interpretation, what can be said with certainty is that

poetry and song were celebrated in southern France during the

Twelfth century and population movement throughout Europe

encouraged that tradition to spread; Flori concludes that as

head of their court whether together or separately, Henry and

Eleanor would welcome travelling poets, musicians and

troubadours, just as they would extend hospitality to other

travellers but this is not evidence of patronage.43

The Courts of Love

41 P. Schoyer Brooks, Queen Eleanor: Independent Spirit of the Medieval World: A Biography ofEleanor of Aquitaine (New York, 1983), p.107M. Lazar, ‘Cupid, the Lady and the Poet: Modes of Love at Eleanor of Aquitaine’s Court’, in W.W. Kibler, Eleanor of Aquitaine, (Austin, Texas, 1976), p.38S. Schama, A History of Britain: At the Edge of the World? 3000BC-AD1603, (London, 2009), p.11042 R. Harvey, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Troubadours’, in Bull & Leglu (eds), World of Eleanor, p.10143 Flori, Eleanor, p.249

C1161252

19

Accompanying this myth is the concept of ‘Courtly Love’, (an

unrequited love between a knight and a lady of noble station

which is unlikely to be consummated), which has been expanded

by certain biographers to encapsulate a ‘Court of Love’

overseen by Eleanor and her daughter Marie in Poitou between

1166-1173 where lovers brought matters of the heart to the

Queen for guidance.44 Schoyer Brooks, Meade and Kelly’s Speculum

article from 1937 cite Andreas Capellanus Twelfth century work

The Art of Courtly Love as evidence for the existence of such a Court

with Eleanor acting as both mediator in matters of love and

exemplifying how life at court should be conducted.45

This view has been brushed aside by Owen, Flori, Turner and

others citing there is no evidence to support the existence of

such a court; Owen vociferously states that there is also no

evidence to suggest Eleanor had any contact with her daughter

Marie, who was seven when she divorced Louis in 1152.46 Turner

suggests that the growth in modern writers utilising medieval

literature, either to supplement or instead of the traditional

Latin chroniclers, has resulted in an increase in ‘emotional’

biographies of Eleanor that have little basis in fact.47

Nicholas Vincent is similarly critical claiming certain modern

writers do not differentiate between sources and ascribes

equal credibility to all, which highlights a lack of academic

44 Schoyer Brooks, Queen Eleanor, p.110-245 A. Kelly, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine and her Courts of Love’, in Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, January 1937, Vol:XII, No.1Kelly, Eleanor, pp.159-6046 Owen, Eleanor, p.15547 Turner, Eleanor, pp.312-3

C1161252

20

nuance to analyse what is valuable evidence to support their

theories and what is not.48

During the last fifty years, sources like Capellanus have been

analysed and stripped of major historical significance, with

modern academic heavyweights (Turner, Flori, Owen, etc.)

concurring that his book was either ‘an ironic, humorous

account of courtly love or a severe criticism of its

doctrines’.49 With this particular myth opinion is divided

between the romantic vision of Eleanor as patroness of a gay,

brightly dressed court full of music and the more pragmatic

approach decrying the lack of real evidence to support it.50

Eleanor and Fontevraud

Surviving charters provide evidence of Eleanor’s beneficence

towards Fontevraud, the place to which she retired in 1194 for

material and spiritual comfort.51 Martindale describes annual

grants made by Eleanor to Fontevraud which provide evidence of

48 N. Vincent, ‘The Indiscretions of the History Men’ Times Literary Supplement, February 15 200849 Turner, Eleanor, p.19950 E.A.R. Brown, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine Reconsidered’, in Wheeler & Parsons, Eleanor, p.251 Castor, She Wolves, p.209

C1161252

Figure 5: Effigies ofEleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II at Fontevraud Abbey

www.commons.wikimedia.org

21

her sustained patronage of the Abbey, which had enjoyed prior

patronage from both Eleanor and Henry’s forebears and was

conveniently located to both natal provinces.52 Kathleen

Nolan’s study of Eleanor and Fontevraud concludes that in all

probability it was a convenient location to bury Henry, close

to his place of death and familial lands, which became the

family mausoleum when both Richard and Joan were buried

there.53 As Eleanor was imprisoned in England at the time of

Henry’s death and it is highly unlikely she would have issued

any instructions regarding the place of his burial.54 Brown

quotes from Gerald of Wales who deems the burial of Henry at

Fontevraud an act of divine retribution, given that he wished

to confine Eleanor within the Abbey walls long before his

death.55

Family Dynamics

Modern historians agree that Eleanor was the instigator in

seeking a divorce from Louis; she was unhappy in the marriage

and even the intervention of Pope Eugene III in 1149 failed to

rectify the problems. Criticism of Eleanor has generally come

from three areas; her failure as a mother by leaving her young

daughters with Louis, taking the duchy of Aquitaine with her

52 Martindale, Status, Authority & Power, ch.XI p.17-1853 K. Nolan, ‘The Queen’s Choice: Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Tombs of Fontevraud’, in Wheeler and Parsons, Eleanor, p.380E.A.R. Brown, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine: Parent, Queen and Duchess’ in Kibler, Eleanor, p.20A. Erlande-Brandenburg, ‘Les Gisants de Fontevrault’ in R. Gregory (trans.), Figuration of the Dead in Medieval Christendom (Berkeley, 1989), pp.4-554 J. Martindale, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine’, in J.L. Nelson (ed.), Richard Coeur de Lion in History and Myth (London, 1992), pp.20-155 Brown, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine’ in Kibler, Eleanor, pp.30-1

C1161252

22

and morally acting like a man by wishing to end an unhappy

union. Hilliam points out that custody of Marie and Alix was

granted to Louis by the four archbishops who confirmed the

annulment of their marriage, giving Eleanor no option but to

leave them with him.56 Technically the duchy of Aquitaine was

Eleanor’s inheritance and was bestowed upon her husband,

therefore if she changed husbands then her province had a

change of Duke; Marie Hivergneaux suggests that this is an

issue for French sources who keenly felt the stripping away of

the assets of Aquitaine and in all probability contributed to

the blackening of her name and reputation in France.57

The very idea that a woman would seek to set aside a husband

because he did not satisfy her or make her happy was

inconceivable in the twelfth century, this was very much male

behaviour at a time when a highborn woman was usually traded

in marriage for some territorial gain or political alliance.

Many historians refer to Eleanor’s supposed quote stating

Louis was ‘more monk than man’ which adds sexual incongruity

to the problems in their marriage; not only was Eleanor

unhappy with married life in general but there were problems

in the bedroom too, which historians suggest was the reason

for the lack of children in the royal nursery after fifteen

years of marriage.58 This would seem to be borne out as Eleanor

produced eight children between 1153 and 1166 when married to

56 Hilliam, Eleanor, p.4157 M. Hivergneaux, ‘Queen Eleanor & Aquitaine, 1137-1189’, in Wheeler & Parsons, Eleanor, pp.62-3Duby, Women of the Twelfth Century, p.958 H.E. Lehman, Lives of England’s Reigning and Consort Queens, (Bloomington, 2011), p.83-4

C1161252

23

Henry, whilst Louis was well into his forties when his third

wife produced the desired heir.

There is also some agreement between modern writers as to why

Eleanor married so quickly after divorcing Louis; Martindale

sums up Eleanor’s position by suggesting that she was a highly

desirable heiress who could be kidnapped to gain control of

her lands (she avoided two such attempts on her trip from

Paris to Poitou), so she needed a husband both for political

purposes and for her own safety.59 Eleanor’s union with Henry

was more of a meeting of equals, both had strong characters,

hot tempers and decisive ambitions, but this was not a

harmonious match as attested to by Walter Map and Gerald of

Wales and retold by biographers and historians alike.

The volatile nature of Eleanor’s relationship with Henry

spread to include their offspring, especially their three

older sons Henry, Geoffrey and Richard; an environment

dominated by competition for their father’s favour, mistrust

and desire for personal power – this was not a cohesive family

unit. John Gillingham refers to Henry’s empire as the ‘family

firm’, stating it existed for the benefit of the family; the

lands Henry inherited from his father, his mother and through

marriage to Eleanor combined to provide an inheritance for his

sons whilst his daughters forged dynastic marriages with royal

houses across Europe.60

Owen, Flori, Turner and more all state that Henry’s reluctance

to part with authority was the prime reason behind his sons 59 Martindale, Status, Authority, p.14260 Gillingham, Angevin Empire, p.116

C1161252

24

rebellion and Eleanor’s support for that rebellion was a

direct result of Henry undermining her authority in Aquitaine

(specifically for the concluding of a treaty with Toulouse

rather than pursuing her claims to the duchy).61 Eleanor’s

imprisonment as punishment by Henry was preferable to divorce,

Henry was all too aware that he would lose Aquitaine by

divorcing Eleanor, so from 1174 until Henry’s death in 1189

Eleanor remained his prisoner in secure accommodation, away

from her familial powerbase.

Andrew Lewis explores the birth and childhood of John and

draws parallels with Aurell in concluding that Henry and

Eleanor’s parenting skills were responsible for the behaviours

exhibited by all their children, although Eleanor’s absence

through imprisonment during his formative years compounded

those experiences and were certainly a contributing factor to

John’s paranoia and emotional instability in later life.62

Whilst evidence suggests that Eleanor took one or more of her

children with her when travelling through the Angevin lands,

Brown argues that she was ‘more queen than mother’ to them and

only had any real interest in Richard, her supposed favourite,

when he reached adolescence and joined her to administer

Aquitaine.63 In their competitive relationship, Eleanor’s final

triumph over Henry was to outlive him by fifteen years during

which she held real political power through her sons.

61 Brown, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine Reconsidered’, in Wheeler & Parsons, Eleanor, p.1362 A.W. Lewis, ‘The Birth and Childhood of King John’, in Wheeler and Parsons Eleanor, p.169Aurell, Plantagenet Empire, p.4363 Brown, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine’ in Kibler, Eleanor, pp.9-34

C1161252

25

Analysing Eleanor

The main problem when seeking to understand Eleanor and see

what drove her to make the decisions she did, is the

fundamental lack of reliable, impartial information. Turner

desperately tries to find the ‘real’ Eleanor but is restricted

by utilising the same sources read and re-read by earlier

historians with no new conclusions. The same can be said for

Owen and Flori, and although Richardson attempts to widen the

pool of sources by reviewing Eleanor’s charters and letters,

he is hampered by the relatively small number of such

documents at his disposal to make any real impact. Martindale

seeks to analyse Eleanor’s political status and authority with

particular reference to Aquitaine but this again is limited by

the amount of information available.

In 1973 Brown compiled a psychological profile of Eleanor,

applying twentieth century moral and ethical values to a

twelfth century queen which produced some stringent criticisms

of her as a wife and mother. In 2002 she revisited the topic

and came to the conclusion that this passionate, manipulative

woman was impossible to pigeon-hole and continued to be a

subject of speculation.

Eleanor remains an enigma; a character created by the media of

her own time and embellished through eight hundred years of

creative writing. The scarcity of definitive evidence is what

attracts modern historians to Eleanor and her appeal shows no

sign of diminishing in the twenty first century. New evidence

in the form of religious iconography erected in her honour

C1161252

26

(stained glass windows and the effigies at Fontevraud),

artefacts like her royal seals or the Rock-Crystal Vase of

Saint-Denis or even the relatively new interest in materiality

of buildings and their social biography leading to an analysis

of architectural features associated with her may provide more

clues but Eleanor will continue to attract speculation and

historical study because her story is so tantalising.

C1161252

Figure 6: Rock-Crystal Vase of Saint-Denis (c.12th century) Le Louvre, Parishttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_crystal_vase

27

Bibliography

M. Aurell, D. Crouch (trans.), The Plantagenet Empire 1154-1224

(Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2007)

L. Benz St. John, Three Medieval Queens: Queenship and Crown in

Fourteenth-Century England (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

M. Bull and C. Leglu (eds.), The world of Eleanor of Aquitaine: literature

and society in southern France between eleventh and thirteenth centuries

(Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2005)

A. Capellanus, J.J. Parry (trans.), The Art of Courtly Love

(Chichester: Columbia University Press, 1941)

H. Castor, She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England before Elizabeth

(London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2010)

F.M. Chambers, ‘Some Legends concerning Eleanor of Aquitaine’,

Speculum 16 (1941), pp. 459-68

R.L. Chapman, ‘A Note on the Demon Queen Eleanor’, Modern

Languages Notes, vol.LXX, no.6, June 1955

C. Daniell, From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta: England 1066–1215,

(Abingdon: Routledge, 2003)

G. Duby, Women of the Twelfth Century Vol. 1, Eleanor of Aquitaine & 6 others

(Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997)

C1161252

28

A.J. Duggan (ed.), Queenship in Medieval Europe (Queenship and Power)

(Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997)

T. Earenfight, Queenship in Medieval Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2013)

A. Erlande-Brandenburg, ‘Les Gisants de Fontevrault’ in R.

Gregory (trans.), Figuration of the Dead in Medieval Christendom

(Berkeley: University of California, 1989)

M.F. Facinger, ‘A Study of Medieval Queenship: Capetian France

987-1237’, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, 5 (1968), pp.3-47

R. Fawtier, . L. Butler & R.J. Adam (trans.) The Capetian Kings of

France: Monarchy and Nation 987-1328, (London: Macmillan, 1960)

J. Flori, O. Classe (trans.), Eleanor of Aquitaine: queen and rebel

(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007)

J. Gillingham, The Angevin Empire, (London: Hodder Group, 2001)

S.W. Hahn, The Kingdom of God as Liturgical Empire: A Theological Commentary

on 1-2 Chronicles, (Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing, 2012)

E.M. Hallam & J. Everard, Capetian France 987-1328, (Harlow: Pearson

Education Ltd, 2001)

D. Hilliam, Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Richest Queen in Medieval Europe (New

York: Rosen Publishing Group, 2005)

L. Hilton, Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens (London:

Weidenfeld Nicolson, 2008)

C1161252

29

A. Kelly, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine and her Courts of Love’, in

Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, January 1937, Vol. XII, No.1

A. Kelly, Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings (Cambridge

Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press, 1950)

W.W. Kibler (ed.), Eleanor of Aquitaine, Patron and Politician (Austin,

Texas: University of Texas Press, 1976)

H.E. Lehman, Lives of England’s Reigning and Consort Queens, (Bloomington:

Author House, 2011)

J. Martindale, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine’, in J.L. Nelson (ed.),

Richard Coeur de Lion in History and Myth (London: King’s College London

Centre for Late Antiquity and Medieval Studies, 1992), pp. 17-

50

J. Martindale, Status, Authority and Regional Power (Aldershot:

Variorum, 1997)

J. Martindale, ‘Eleanor, suo jure duchess of Aquitaine

(c.1122-1204)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford

University Press, 2004; online edn. May 2006

[www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/8618, accessed 23 Jan 2014].

M. Meade, Eleanor of Aquitaine: a biography (London: F. Muller, 1978)

H. Moller, ‘The Meaning of Courtly Love’, in The Journal of

American Folklore (1960), pp.39-52

D.D.R. Owen, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Queen and Legend (Oxford U.K. and

Cambridge Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 1993)

C1161252

30

J.C. Parsons, Medieval Queenship (New York: St Martin’s Press,

1993)

H.G. Richardson, ‘The Letters and Charters of Eleanor of

Aquitaine’, English Historical Review 74 (1959), pp.209-11

S. Schama, A History of Britain: At the Edge of the World? 3000BC-AD1603,

(London: Random House, 2009)

P. Schoyer Brooks, Queen Eleanor: Independent Spirit of the Medieval World:

A Biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine (New York: Houghton Mifflin Books,

1983)

D. Seward, Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Mother Queen (London: Book Club

Associates, 1978)

G.M. Spiegel, Romancing the Past: The Rise of Vernacular Prose Historiography

in Thirteenth Century France, (London: University of California Press,

1993)

R.V. Turner, Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England (New

Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009)

R.V. Turner, ‘Eleanor of Aquitaine, twelfth-century English

chroniclers and her “Black Legend”’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 52

(2008), pp. 17-42

E.M.C. Van Houts, Memory and Gender in Medieval Europe, 900-1200,

(Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1999)

N. Vincent, ‘Patronage, Politics and Piety in the Charters of

Eleanor of Aquitaine’, in M. Aurell and N-Y. Tonnerre (eds.),

Plantagenets et Capetiens: confrontations et heritages (Turnhout: Brepols,

2006), PP. 17-60

C1161252

31

N. Vincent, ‘The Indiscretions of the History Men’ Times Literary

Supplement, February 15 2008

W.L. Warren, King John, (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1978)

A. Weir, Eleanor of Aquitaine: by the wrath of God, Queen of England (London:

Vintage, 2007)

B. Wheeler and J.C. Parsons (eds.), Eleanor of Aquitaine. Lord and Lady

(Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002)

E. Woodacre (ed.), Queenship in the Mediterranean: Negotiating the Role of

the Queen in the Medieval and Early Modern Eras (Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2013)

C1161252