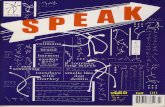

Portraiture as gossip: Andy Warhol's 1963 cover design for "C

Don Boyd's Gossip

Transcript of Don Boyd's Gossip

CHAPTER NINE

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

DAN NORTH

In November 1982, Don Boyd was two weeks into the shooting of his latest film, Gossip.1 This was to be his return to directing after a high-profile stretch as producer of a raft of British films and the subject of a significant amount of hype and controversy. The script had been in development for over two years, drafted and redrafted by brothers Michael and Stephen Tolkin, inspired by The Sweet Smell of Success and La Dolce Vita, though its sweetness was alloyed with the acidity of Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies. A cast of new, mostly young performers filled the main parts and the budget was a lavish £2 million. The only problem was that the core funding for the production existed only as a phantasmic, fraudulent promise. On 14 November the production was shut down, and it has never resumed. This is the story of what happened, and an analysis of the remnants of an important British film. It uses archival resources to reconstruct events surrounding the collapse of Gossip, and examines the surviving footage. This is certainly an unfinished film – less than a quarter of the script was shot - but insofar as it provides an entrypoint to considering certain aspects of the British film industry in the early 1980s, Gossip can be considered a complete text; there is as much contextual, historical and industrial information here as for most other films, and even if there is no opportunity for a full formal analysis of how its visual style connects with that background detail, we can surely benefit from reading the fragments

1 The majority of the research for this chapter was made possible by the holdings of The Don Boyd Collection at The Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture at the University of Exeter. I am grateful for the staff of the archive and the reading room for their assistance with these papers. All archival references (DBC), unless otherwise stated, relate to this collection.

CHAPTER NINE

176

Fig. 1: Don Boyd (far right) directing Gossip. as an index of film production in the London of 1982. To this day, Boyd cites Gossip as the lynchpin of his downfall, believing its collapse to have been at best the inevitable outcome of a brittle, booby-trapped industry where adventurous artists find precious little shelter from circumstance, and at worst a deliberately orchestrated intervention in his career by a shadowy foe. I will argue that, despite being unfinished, the film is still textually active as a cultural object, articulating through its own scandalous dissolution something pertinent about its cultural and industrial context.

The Boyd’s Co. Promise

When he arrived to promote his first feature film, Intimate Reflections, at the London Film Festival in 1975, Don Boyd was only twenty-six years old, but in his introductory speech he hinted at an iconoclastic revival of British cinema in opposition to the critical and industrial status quo:

British movies have traditionally been parochial. Very few British directors have made films that appeal in content and style to universal audiences (obviously there are exceptions). I think the time has come in Britain for a serious reassessment of the attitude of film-makers or critics (often

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

177

ridiculous misplaced reverence) to the naturalistic and realistic style of film-making – a style set by directors like Anderson, Richardson, Reisz, etc. over ten years ago (directors who in their time have made valuable and worthy films).2

Boyd frequently invoked this rhetorical conflation of critics, audiences and film-makers as an interconnected industrial identity, each playing a supportive, implicitly patriotic role. His media profile was as a high-volume mouthpiece for a certain type of British cinema that mixed artistic credibility with sound commercial sense; this oscillation between publicity-conscious populism and artistic integrity would define the identity of Boyd’s Co. for years to come. Boyd’s ambition was to lead British film-making by example, to offer a template for films that could earn their money back from the domestic audience without pandering to trite sensationalism or mainstream formulae. Such a model might thus create the basis for a national cinema that did not debase itself for quick box office returns or Hollywood patronage. Needless to say, the outcome was not such an artistic utopia.3

After directing his own films Intimate Reflections and East of Elephant Rock (1977), Boyd’s company set about preparing a package of films that, even before they were made, confirmed the perception that Boyd’s Co. was a fertile production base for new British cinema. Most of the money came from Roy Tucker’s Rossminster group, whose tax shelter schemes were controversial at the time but now seem par for the course in attracting investment to British film-making. Boyd had also sold, in 1978, the screenplay (written with Ed Clinton) which would become Honky Tonk Freeway, giving him a level of financial confidence and security to write up a roster of films that Boyd’s Co. would turn out. Many of these films never came to fruition, but instead occupied catalogues of future productions, sometimes with pre-publicity artwork in place before shooting (or even casting) had begun.4 By May 1980, though, Boyd’s Co. had released Derek Jarman’s thaumaturgic adaptation of The Tempest, the rock n’ roll documentary Blue Suede Shoes (directed by Curtis Clark), 2 Intimate Reflections programme notes, 19th London Film Festival, 1975. The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 708. 3 For more on the early career of Don Boyd, see Walker, National Heroes, 144-66; North, “The Accidental Producer”; Walker, The Once and Future Film, 139-45. 4 For instance, the 1980 Boyd’s Co. brochure lists eight films in preparation, with preliminary artwork in place, including an animated adaptation of Jekyll and Hyde by Ian Emes, Derek Jarman’s post-apocalyptic Neutron, the Claude Chabrol vehicle The House on Avenue Road and Ron Peck’s Actors.

CHAPTER NINE

178

Sweet William (adapted from Beryl Bainbridge’s novel and directed, on her insistence, by Claude Watham) and the biggest box office draw of all, Scum, the cinema version of Alan Clark and Roy Minton’s banned BBC borstal drama. By this time, Boyd was already delegating the handling of Boyd’s Co. to Michael Relph while he himself tried to broaden his connections in North America. In Hollywood, working on Honky Tonk Freeway, a project which he had developed for himself to direct but which he ended up producing for John Schlesinger, and whose budget would become morbidly obese, he started to foster the ideas that would become Gossip, the film which would cement his position as a creditable British artist in America, and remind the industry that what he really wanted to do was direct (again).

Writing Gossip

Although the precise plot of Gossip changed over the course of numerous re-writes, at its core was always the story of a journalist who pores over the private lives of celebrities until forced to reconsider the ethics of her occupation. The driving force of the film was a critique of a burgeoning celebrity culture and the bottom-feeders who end up sustaining it. If we consider the shooting script to be the one that would have defined the completed story, then Gossip follows the fortunes of Clare Sendrow (played by Anne Louise Lambert), a young gossip columnist.5 When we first meet her, she is a feted figure gliding through the London nightlife in a montage that shows how easily she can infiltrate the spaces frequented by her human subject matter; the rest of the film will gradually disintegrate the harmonious relationship she is initially seen to enjoy with her social environment. The script makes one theme very plain in the opening credit sequence:

We will see the more sensitive side of [Clare’s] personality fighting the more brittle moods which the nature of her work conditions her to adopt …6

5 The character’s name is variously spelled “Clare” or “Claire” in various drafts and notes from the film’s production. I have settled, more or less arbitrarily for what I perceived as the most frequently used version, for the sake of consistency. 6 Gossip, screenplay draft, 5 October 1982 (new pages added 21 October), The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 70.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

179

Clare is sleeping with Andrew Saybrook, a handsome aristocrat who supplies drugs for her younger brother and occasional informant Oliver (played by Gary Oldman7), and who discards her immediately after sex, a fairly blunt articulation of Clare’s position on the peripheries of the rich and famous, both exploiter and exploited. Clare is in trouble with her editor over a story she has written about Alice and Edward Bircham and some sexual party games occurring at a private soirée on their premises; by reporting on the goings-on at a private function, she has committed the “cardinal sin of gossip columnists”8 and upset the delicate equilibrium of publicity and probity that had allowed gossips and their subjects to co-exist in a symbiotic circuit. She finds herself barred from functions that might ordinarily have welcomed her, in contrast to the access-all-areas status she was seen to possess at the film’s opening. Gate-crashing the unveiling of a new nightclub, she meets William, its architect, with whom she strikes up a stop-start flirtation based on spontaneous role-play, acting out imagined scenes of stealthy espionage. William also teaches at Cambridge University; his roguish, ironic sense of humour is a lifeline to Clare, enticing her to take a more detached view of the absurdities and pomposities of the social coteries upon which she has become a parasitic encrustation.

A running thread through the story is the anticipated arrival of Princess Adriana of Amalfi, who flies to the UK in pursuit of her errant husband; Adriana, at the centre of a potential scandal, represents to Clare the scoop that could secure her own fame and clear her debts (“I need a real juicy story. A twenty-three carat gold scoop. I’m running out of credit. I am afraid I am going to have to play dirty.”). However, when she finally engineers a confrontation between the royal couple, Clare has a change of heart and shares an intimate conversation with Adriana that marks Clare’s rejection of the gossip columnist’s lifestyle; she accepts the value of privacy and discretion, unaware that she is being duped. Subsequently 7 Oldman was to have made his screen debut in Gossip, though none of his scenes were ever shot. It appears that he replaced another future star, Rupert Everett, in the role of Oliver. There is barely a mention of Everett in the papers concerning Gossip in The Don Boyd Collection at The Bill Douglas Centre, but on a videotape of auditions for the role of Clare, he can be seen reading the part of Oliver. Casting took place in August and September 1982. Among those tested for the role of Clare were Greta Scacchi, Jenny Seagrove, Glynis Barber and Kim Thompson (all interviewed 6 August). For the role of William, David Hayman, Julian Sands, Nickolas Farrell, Andrew Seear and Nicholas Gecks were all interviewed on 20 August. 8 Don Boyd script notes, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 69.

CHAPTER NINE

180

ignored by Adriana, and having quit her job, she is abducted by William and taken to a smoker at King’s College, Cambridge, where he proposes to her.

In her online biography, former Ritz columnist Frances Lynn still lists Gossip as a treatment she was commissioned to write about her own experiences.9 Boyd denies that the story was based on any particular person, claiming that the character of Clare was based on a conglomeration of parts from Nigel Dempster and Lucretia Stewart, two prominent columnists.10 Dempster, who once described himself as “the greatest gossip in the world” saw his task as “to provide insights into the workings of those who are above us in terms of power and privilege, position and money.”11 This “champion of the underdog”, as The Daily Mail (who published his columns from 1971 to 2003) dubbed him in their obituary, used his aristocratic connections to glide from debutantes’ balls to embassy dinners, passing on bedroom secrets gleaned from his fellow guests.12 Dempster, like Lucretia Stewart and many other columnists, also wrote for Fleet Street’s flipside, Private Eye, which could develop the most risqué stories with relative anonymity, and from behind a satirical shield. Nicholas Coleridge suggested in The Evening Standard that advance publicity for Gossip had led some public figures to speculate on its contents:

There is already some speculation over who is going to be lampooned in Don Boyd’s film Gossip that there was surrounding Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop. Before a single foot has been shot of his forthcoming movie, based on four days in the life of a female gossip columnist, it has become a social imperative among café society faces to be recognised as the basis for one of the 40 transparent parodies in the screenplay.13

It is unclear where this advance buzz was coming from, or who suggested the very precise figure of “40 parodies”, but it sounds as though the film was already participating in the networks of chatter that it had taken as its subject.

9 http://www.franceslynn.org/biography.asp 10 In an advance notice of the film in The Hollywood Reporter, 16 September 1980, 13, Kenelm Jenour quotes Boyd as describing Clare as “a younger Rona Barrett figure”, referring to the American columnist and broadcaster. 11 Leavy, “Nigel Dempster.” 12 Ibid. 13 Coleridge, “The Best Place to Shoot the Gossips”, 18.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

181

Lucretia Stewart had come to Boyd’s attention while he himself was becoming a public figure, and her ability to extract “dirt” from fellow guests at a dinner party had sparked his interest in the “strange relationships” that columnists had with the people around them.14 During the peak years of Boyd’s Co’s profile, he became friendly with the photographer David Bailey, who provided a portal to the London fashion scene. The demimonde of glamour and privilege he found there must have offered an uncomfortable summation of his own position, pendulating between a need to offer sustenance to struggling artists through his company, and a need to court the favours of the powerful and influential in the film business. He has admitted to some disgust at his own willingness to participate in festivities of the kinds of high society that he should, as champion of film-makers like Derek Jarman and Alan Clarke, have been attacking.15 Torn between storming the castle of aristocratic privilege and observing it from within, Boyd may have felt conflicting feelings about the role of the gossip columnist, who depends upon the titled and the advantaged, while claiming to be their adversaries.

The development of Gossip began in earnest while Boyd was in Hollywood. As producer of Honky Tonk Freeway, and with his own East of Elephant Rock (1977) as a calling card, he was able to get some ideas across to producers. Don Simpson, prior to his period of lucrative profligacy in partnership with Jerry Bruckheimer, commissioned Boyd to direct Matthew Chapman’s script of Manon (adapted from the Abbé Prevost’s Manon Lescaut (1731)), another of Boyd’s long-cherished projects that, despite going through many drafts and casting sessions, never made it beyond the script stage. But it was while working in New York for EMI on another unmade film, Night People, that he met writers from The Village Voice, including Michael Tolkin.16 Both Dempster17 and Stewart served as advisors during the writing of the film, but the bulk of the screenplay was put together by Tolkin and his writing partner (and his brother) Stephen.

14 Don Boyd, interview with the author, 30 November 2004. 15 Ibid. 16 Prior to the Gossip screenplay, Michael Tolkin had written a script for an animated short called Monty the Mole, which might have become a series of cartoons, but which never made it into production. 17 Dempster’s employment is confirmed by correspondence from Michael Relph to Anthony Joes at A D Peters, London, 6 January 1982. The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 1197.

CHAPTER NINE

182

Frances Lynn had written for Boyd a treatment entitled Frantic: A Story About a Gossip Columnist in 1979.18 It featured characters only very thinly disguised by their names, including herself in the lead role of ‘Frantic’ – ‘Hamster’ is London’s top columnist, and David Dailey and Marie Shelvin are a famous photographer and his fashion model partner (Ceci Weaton and David Witchfield also make appearances, as does Romo Dolonski, “the Polish film-director who was out on bail for abducting a 12 year old girl”). Treatments are more of a feasibility study than a precise indicator of how a final film will turn out, but this version had a bitchy, carnivalesque tone that dripped with scorn for the self-absorbed cluster-fucking of the filthy rich, taking place entirely on a breathless circuit of parties. It was probably too close to the scattershot style of the kinds of journalism it was supposed to be satirising, and therefore difficult to turn into a dramatic feature. Furthermore, it was almost certainly libellous, but it served as a foundation for the future scripts by establishing Clare’s story as a moral odyssey through soul-destroying wine receptions.

Universal had optioned Gossip from Lynn’s treatment on 1 November 1979,19 and the following February Boyd had engaged the Tolkins as writers. They produced their first screenplay draft in the summer of 1980.20 The central characters of Clare, her brother and sometime assistant Rudy (later Oliver) and Jeff (later William), the mysterious man whose contempt for the world of celebrity gossip offers her a route out of that milieu (although in this draft he too is a jaded columnist rather than an architect), are all in place, as well as the macguffin of Princess Adriana, and they have given a goal-orientated dramatic structure to Lynn’s torrential sequence of events. If Boyd’s earlier films were dogged by some tentative or stilted dialogue scenes, then the screenplay for Gossip 18 Frances Lynn, script treatment, Frantic: A Story About a Gossip Columnist, no date (c.1979), The Don Boyd Collection, file no. 69. In another piece dated 23 November 1981, Lynn provided a list of London locations that Clare might have to visit at various points in the course of her work. 19 Gossip option agreement with Universal Pictures, 1 November 1979, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 86. Page 5 of this document includes, with some irony, the clause controlling sequel, remake and television rights to the finished film. Kendon Films acquired all rights to the Gossip screenplay in March 1980, when contracts were signed acquiring an Option Agreement (Motion Picture and Allied Rights), the Assignment of All Rights, the Short Form Assignment and the Short Form Option. 20 Unfortunately, the earliest copy I have been able to locate and consult is dated 31 October 1980.Michael and Stephen Tolkin, Gossip screenplay draft, 31 October 1980, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 765.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

183

suggests a much tighter, snappier composition with barbed repartee and, particularly in the earlier drafts, a sense of the grotesque: two characters are killed by their young children in a game of cowboys and Indians that escalates out of control, all captured on the kids’ own video tape of their exploits, a horrifically succinct vignette about voyeurism and societal rot.21 In this first draft, Clare and Jeff do not meet again at the end, but in the next version, Jeff is reappearing in the final scene at Clare’s side as she skims stones with kids by the riverside – a picture of innocence and simplicity far removed from her earlier embroilments in metropolitan party lives.22 Other revisions gradually smooth out the edges and ambiguities in Clare’s character to make her more sympathetic (she no longer takes heroin with Jeff – by the time of the shooting script, they bond over a cup of tea), less ethically erratic.

The biggest overhaul of the Gossip screenplay came when it was decided to transplant the setting from New York to London. According to Stephen Tolkin, Thom Mount, Vice President in charge of production at Universal, had found the script (which he had originally commissioned) “arty and European, and … nothing to do with anything they had any desire to make.”23 Mount had wanted the film to hinge upon Clare’s murder, and to be structured around flashbacks that would reveal who wanted her dead. Rejection from Universal left Boyd free to take the project elsewhere. With Boyd’s Co. floundering, and smarting from the devastating box office reports and reviews for Honky Tonk Freeway, it seemed expedient to remould Gossip for the British setting which had inspired it in the first place. Discussing his return to London from New York, Boyd told The Evening Standard:

It seemed to have changed completely and almost beyond recognition while I had been away. People suddenly seemed more ambitious, rich people less inhibited about their wealth, the whole city much more social and high-profile. In a short space of time I realised that the movie had to be made over here. Why on earth were we thinking of filming in New York,

21 The script revisions recommended for the April 10th draft say that these scenes are not realistic enough and should be altered: “I agree that the violent death of the mother and father is dramatically effective later in the script but the idea of Ariel and Gabriel killing them in the process of making a home make [sic] TC show is rather far fetched ad perhaps a little more macabre than it needs to be.” Don Boyd, Gossip script notes, May 1981, The Don Boyd Collection, box no. DBC 301. 22 Michael and Stephen Tolkin, Gossip screenplay draft, 10 April 1981, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 766. 23 Stephen Tolkin, correspondence with the author, 27 March 2004.

CHAPTER NINE

184

where I anyway felt much less socially confident, when London had suddenly become the gossip capital of the world?24

On 9 December 1981, the Tolkins were flown from Los Angeles to London for a three week research trip to soak up the scene and redraft the script for an English setting.25 Naturally, this involved quizzing the guests at a succession of nightclubs and parties.

Stewart’s frankly forthcoming script notes were particularly useful when it came to finessing the transition of the story from New York to London. She noted that New York gossip writing was mostly aimed at fashionable media celebrities, while the British press flavoured their columns with a hint of class warfare:

In a sense, for people to be gossip-worthy in England they have to be one of the following: very rich, titled, deviant (preferable [sic] combined with the former): powerful (and not as a dress designer either) related to someone famous …26 Stewart basically provided Clare’s character with a “how to…” guide

to being a gossip columnist, advising on where to find subject matter (“balls – this is where the upper classes come into their own”), sexual politics (“almost all references to homosexuals are derogatory in the British Press … [Clare] shouldn’t really be bothering with so many fags”) and Westminster politics (“politicians are fair game”). Her guidance may have made the film reflect her own experience more accurately, but in some ways it may also have depleted the strange aspects of the Tolkin script, which were also its great strength.

Finding the Money

Without the patronage of Universal, Gossip needed new backers. While the Tolkins set about their new writing assignment, Boyd sought finance (all the while co-producing Scrubbers (Mai Zetterling, 1983) in collaboration with HandMade films). Following a trip to Cannes in May 1982, he met with Alan Shephard, a representative of “the Martini Foundation”, back in their Mayfair offices, which they had decked out with family crests and other artefacts of entitlement. This heavily- 24 Quoted in Coleridge, “The Best Place to Shoot the Gossips”, 18. 25 Letter from Alan Scarfe to TWA Reservations Dept, 9 December 1981, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 86. 26 Lucretia Stewart, script notes, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 70.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

185

moneyed, Lichtenstein-registered company, led by Raymond Lanciault, had sold out its interest in the Martini Rosso drinks business, and wanted to expand into film financing, and were prepared to give Boyd $20 million to invest in the production of four films.27 Rather than providing Gossip’s $5 million upfront, the Martini Foundation were to provide certificates of deposit with a mutually agreed bank in the Netherlands, against which Boyd could borrow to pay for the costs of pre-production. The Foundation would receive a $600,000 introductory fee and 50% of the profits from the film.28

The stage-by-stage story of how the production of Gossip ceased is too lengthy to be included here, but it depends upon one simple detail: the certificates of deposit against which the costs of production had been borrowed did not exist. The Martini Foundation deployed repeated delaying tactics to give the impression that their arrival was imminent, but they never materialised. Boyd’s error had been a naïve one, proceeding with principal photography before there was concrete confirmation of the money’s actuality. When the shooting stopped in November 1982, a vast night-club set, constructed in Twickenham Studios at a cost of £100,000, was left dormant.

Shooting had commenced 25 October 1982, with £100,000 of interim finance that had been advanced from a company called Terrell SA, which had partly funded the script writing stages. Filming lasted as long as was possible on the Terrell money, finally shutting down on 14 November. It wasn’t until January of 1983 that Boyd accepted that this had been a confidence trick committed against him by the Martini Foundation, but no legal action could be taken against them – his company didn’t have sufficient funds to mount an action, and nothing could be recovered from a Lichtenstein-based company in any case. As of September 1983, the liabilities from Gossip’s production company were calculated at £1,162,000.29

27 Clark, “Gossip: A Cautionary Tale”, 16. Shephard confirmed these arrangements in a letter to Boyd dated 4 June 1982. 28 Many of these financial details can be found in the liquidation documents for Boyd’s Co (Gossip) Ltd., the company (originally called Trestleport Ltd) which Boyd had purchased and incorporated to make the film. The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 374. 29 Liquidation documents, Boyd’s Co (Gossip) Ltd., 16 August 1984, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 374.

CHAPTER NINE

186

The Surviving Footage

The Martini agreement had been signed on 6 July 1982, the day after the re-drafted, anglicised screenplay was received from Stephen Fry. Boyd had felt that the Tolkins draft lacked authenticity in its dialogue and its ethnographic observations of partying aristocrats following the trans-Atlantic shift, and had employed Fry to provide a re-write. Fry’s re-write30 alters much of the dialogue to make it more specific to a London setting but, perhaps unsurprisingly given his background in the Footlights Revue, hands over some of the final scenes to a smoker at King’s College, Cambridge; perhaps it is a betrayal of the film’s original stinging critique that Clare ends up swapping one closed-door arena of elite privilege for another.31 One of the final scenes, in which William leads into his marriage proposal by arranging for Clare to be abducted and brought to King’s College chapel, where she enters just as the choir breaks into Handel’s coronation anthem “Zadok the Priest”, is a stirring moment, but it is a romantic contrivance that stands in contrast to the cynicism that made the early drafts so biting. [Fig.2] If one wanted to examine Gossip as an attack on self-absorbed decadence legitimated by the Thatcher government (and it should be very easy to do so, given that it focuses so heavily on the leisure pursuits of the aristocracy), then its use of Cambridge Dons as the alternative exemplars of virtue might block the path of such a discursive avenue. Dempster may have claimed that his gossip was designed to redress the balance of class power, but that seems like a far-fetched piece of self-justification.

30 Gossip Screenplay, 5 July 1982, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 82. A letter dated 28 June 1982, from Jill Gutteridge (associate producer) to Nigel Palmer at Denton Hall and Burgin, details the engagement of Stephen Fry to revise the Gossip script. Fry had been given three weeks and £1000 to undertake the task. The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 87. 31 The final scene to be shot was William’s proposal to Clare, and their fairy-tale ending at King’s College Chapel, which was actually shot at the chapel of Eton College, Windsor. Indeed, some unsigned script notes (possibly from Richard Greatrex) point out the later drafts of the screenplay risked losing audience sympathy by making William a Cambridge Don: “It instantly, in the audience’s eyes isolates him, takes him away from most people’s world – shuts him in an ivory tower … I consider the use of Cambridge as a script device/visual location a mistake, but if Cambridge it is then we must keep away from many of the stereotypes that will only reinforce audience preconceptions.” Script notes, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 69.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

187

Fig.2: Anthony Higgins as William (far left) in a production still from Gossip.

The texts cited as influences for the film reveal the remarkable scale of the ambition invested in Gossip. Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1956) is repeatedly referenced for its specificity of place (Rome) in justifying Gossip’s depiction of London’s Fleet Street scene, but also for its use of the celebrity scene as the canvas for the main character’s existential crisis: a note from September 1980 describes the similarities between Clare and Marcello Mastroianni’s characters:

At the end of La Dolce Vita Marcello Mastroami (sic) seems to have become deaf and blind to innocence. He has completely lost his virginity and in doing so has become an inferior citizen as a result of his promiscuity. In Gossip Clare has also lost her virginity. She is equally promiscuous but consciously so. She is finally romantic about the possibility of innocence and wants to be optimistic. And she does not want to give up. Ironically in observing weakness professionally she becomes acutely aware of her own shortcomings and is determined to do something about it. And if she could include others with her sensibilities that would

CHAPTER NINE

188

be even more exciting. She hates her loneliness and cynicism and is determined to lose them.32 It was clearly hoped that Gossip would slot into a cinematic heritage of

films about the press, including His Girl Friday and The Sweet Smell of Success. Boyd acknowledges Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies only as a coincidental intertext, but Stephen Tolkin confirms his having read it during the process of trans-Atlantic adaptation, even to the extent of including a quotation from the novel on the title page of the first English draft to illustrate the writers “thematic underpinning”:

… Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St John’s Wood, parties in flats and studio and houses and ships and hotels and night clubs, in windmills and swimming baths, tea parties at school where one ate muffins and meringues and tinned crab, parties at Oxford where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris – all that succession and repetition of massed humanity … Those vile bodies.33

A shooting schedule suggests that principal photography was to have been completed on 16 December 1982.34 What might not be apparent from the screenplay, but which is definitely there in the footage, is the reinforcement of Clare’s separateness from the glamorous world she observes. If the dialogue suggests fast-talking gregariousness, the imagery shows her to be fragile and disconnected. Notes to the cinematographer confirm this as an intentional visual motif:

32 Don Boyd, script notes, September 1980, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 1320. 33 Taken from Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies (1930) and reprinted on the cover of a script treatment by Michael and Stephen Tolkin, dated 28 February, 1982. The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 68. Stephen Fry would later write and direct his own adaptation of Waugh’s novel under the title Bright Young Things (2003). On her blog, Frances Lynn cites the book as the novel that inspired her to become a gossip columnist: http://www.blogger.com/profile/10275056224826137022 34 Gossip shooting schedule, 13 October 1982, The Don Boyd Collection, box no. DB 025.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

189

THIS IS CLARES FILM – SHOT WITH HER PRESCENCE – NOT NECESSARILY FROM HER POV – BUT REFLECTING HER FEELINGS – HER LONLINESS – HER JOY SO… - SHE’S BIGGER IN FRAME - SHE’S OFTEN IN THE EDGE OF WIDE SHOT - SHE REVEALS THINGS TO US - WE FRAME HER WIDE ALONE IN ROOMS WHEN SHE IS

ALONE - WE TRACK IN TO CLOSE UPS AT POINTS OF DRAMA CLARE – A PRIVATE INDIVIDUAL IN A CROWD – HER SEPERATENESS – HER LACK OF REAL CONTACT – REVEALLED THROUGH CROWDS – ALONE SO… - USE LONGER LENSES FOR ISOLATION - HER POV OF THINGS – BUT NOT OTHERS POV - HER CLOSE UPS ALWAYS BIGGER [sic throughout]35 The chemistry of competitive banter between the two leads, Anthony

Higgins and Anne Louise Lambert was pre-formed from their appearance together in Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, which had been shot earlier that year. Greenaway’s film was another tale of aristocratic hypocrisy being counter-acted by the poise and decorum with which their sexual power games are executed. Lambert had appeared in Peter Weir’s The Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and as Lucrezia in a lavish BBC costume drama, The Borgias in 1981, a c.v. that cumulatively suggested a cold distance which recommended her to Boyd, but may have worked against the comedic requirements of the role. Gossip severely impeded her promising career, sending her back to her native Australia, where most of her subsequent TV work has been made.36 She was not a bankable enough star to persuade investors to return to the film after its initial collapse, and not sufficiently well known to shake off the bad publicity.

35 Gossip, notes on photography, October 1982, The Don Boyd Collection, box no. DB 025. 36 Stephen Tolkin reports having dinner with Lambert prior to the shooting, at which point she had already professed a desire to retire from acting after the film was completed.

CHAPTER NINE

190

Fig. 2: Anne-Louise Lambert as Clare in a production still from Gossip.

The Aftermath

After the shooting had been shut down, various attempts were made to re-ignite the production of Gossip. Investors were wary of the project’s bad karma, and the cast was not quite starry enough to garner unqualified support. In a letter to David Puttnam in January 1983, Boyd adds a joyous note saying “I think I have refloated Gossip.”37 Later that year, still unable to get the film progressed, he was sounding out Puttnam about the possibility of his joining Goldcrest – it must have been difficult for Boyd, having enjoyed such autonomy in his career to date, to run for the shelter of another company, but a retreat from the bitter aftermath of Gossip was doubtless very tempting.38 Similar deals with the Martini Foundation had caught out Ken Maidment, president of the BFTPA and Carl Foreman (formerly back-listed Hollywood screen-writer, and producer of the Guns 37 Don Boyd, letter to David Puttnam, 20 January 1983, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. 73. Puttnam had read one of the Tolkin brothers’ screenplay drafts and made some concerned suggestions about its suitability, agreeing with Boyd about the appointment of Stephen Fry as a script doctor. 38 Don Boyd, letter to David Puttnam, 30 November 1983, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. 73.

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

191

of Navarone (J. Lee Thompson, 1961)), amongst others, but it was Boyd who suffered the heaviest professional price. He was prevented from working at a time when he needed to salvage his company and take advantage of new opportunities created by the establishment of Channel 4.

The A.I.P. bulletin published an account of the crisis, “Gossip; A Cautionary Tale”, probably based on Boyd’s own write-up of events, with the more personally-affected title “Gossip: A Tragic Fiasco.”39 Their headline was “Never believe a film financier until you’ve checked him out”, which seems like a simple and sensible rule of thumb, but as Boyd himself responded, “there are times when an instinctive, impetuous judgement is best.”40 A healthy film industry might have ensured that film-makers did not need to seek funding from unsavoury, insecure sources, but the Unions were less accommodating; they saw the film collapse, and in particular the resulting loss of work and revenue for their members, as the direct consequence of Boyd’s impetuous decision to proceed with shooting before the film’s finance was fully anchored.

Co-producer Andy Donally had persuaded the unions to forgo their usual practice of having monies placed in escrow to safeguard their members’ salaries in the event of the film being unfinished, thus allowing shooting to go ahead in the first place. An agreement signed on 7 June 1985 shows that Boyd’s Co was to pay the trade union NATKI £29,750 in instalments “sufficient for the Union to withdraw its recommendation to its members not to be employed or sub-contract with the Plaintiffs”; effectively, this meant that until he began paying up, the union members would be advised not to lend Boyd their services: he was being blackballed.41 Over the next three years Boyd was ordered to submit at least 50% of all producer’s fees he received for subsequent work, including his opera compendium film Aria (1987), but the affair dragged on into the early 1990s until sufficient funds had been reclaimed. No amount of analysis on my part will satisfactorily settle the matter of whether the Unions’ pursuit of repayment for lost earnings was disproportionate to Boyd’s culpability in the matter. At least some blame must be cast in the direction of the lawyers who represented and vouched for the integrity of the Martini Foundation: Private Eye reminded its

39 Clark, “Gossip: A Cautionary Tale”; Don Boyd, “Gossip: A Tragic Fiasco”, June 1983, The Don Boyd Collection, box no. 747. 40 Ibid., 19. 41 Correspondence from Anscomb Hollingworth (solicitors) to Boyd’s Co Film Productions Ltd., 7 June 1985, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 374.

CHAPTER NINE

192

readers that Lanciault and Shephard had already been brought to their attention for fraudulent accounting as early as 1977.42

Michael Tolkin blamed Boyd in part for the failure of Gossip, since the director was too preoccupied with the business affairs of Boyd’s Co. to fully devote himself to the craft of film-making:

… The present situation has distracted your attention from problems with the script. You cannot make a good movie and try to be the Messiah of British cinema, or the new Korda, at the same time – or, rather – Fellini doesn’t have an office building.43

Tolkin however, remained loyal to Gossip, refusing to believe that it was truly over. It has been suggested that his experiences on the film inspired him to write The Player, in which a Hollywood executive is stalked and threatened by a rejected screenwriter.44 Boyd didn’t make another film for three years. Finally, he was able to help set up a four-film package in 1985, producing Heroine for Paul Mayersberg to direct.45 Screen International announced his “top-line return to UK scene”, and it seemed as though the fiscal aftershocks of Gossip had passed, but he would continue to be financially and professionally damaged for many years to come.46 He has sometimes averred that Gossip had been deliberately felled

42 Anon., “Martini on the Rocks”, Lanciault had already been convicted of cheque fraud and credit card theft at Bromley magistrates court in 1968. 43 Michael Tolkin, letter to Don Boyd, 18 November 1982, The Don Boyd Collection, box no. DB 025. 44 In Tolkin’s novel, there’s a description of Tom Oakley, a character who bares a passing resemblance to Boyd: “Standing a little behind Civella was Tom Oakley, an English director who had been famous three years ago, that year’s boy genius, but two fifteen-million-dollar movies had died, and now he looked tired, a little whipped. Still, he hadn’t lost the odor of success. He had the shamelessness Griffin respected; he was in the club.” Tolkin, The Player, 69. Earlier in the book, during a threatening tirade against the studio executive, Griffin Mill, a disgruntled producer makes a reference which likens Mill to Thom Mount, who had commissioned and rejected the Tolkin script: “It’s easy to buy things, Griffin. Why don’t you come outside and try and sell something.” “I’m in a meeting right now. Why are you saying all this to me?” “Because I’m rich, because I don’t give a shit. Because you said you liked Gossip but you didn’t fight for it, and it’s in turnaround now …” Ibid., 20. 45 Bilbow, “Boyd’s Heroine”, 15. The other films were to be produced by David Puttnam, Jeremy Thomas and Michael Hamlyn. 46 Ilott, “Boyd in Top-line Return.” Even at this time, the four-film package was delayed by the refusal of the Federation of Film Unions to accept his offers to

DON BOYD’S GOSSIP

193

by a shadowy conspiracy of his industry rivals,47 a rather irrational and emotional theory that can probably be discounted, but such (fictional?) intrigue around the production applies an extra layer of mystique to the meta-narrative of Gossip’s demise. Just as Clare’s character was compromised by her closeness to the world from which she had hoped to remain a detached observer, so Boyd felt himself ensnared in what he saw as an industry which was desperate for commercial success but punishing of those who approached its achievement. Boyd told biographer Guy Phelps in 1984:

The Gossip story explains the problems film-makers have more succinctly than any experience I can think of; it explains the financial problems, questions of loyalty, the conflict between [creativity] and business, the complex infrastructure of a film and the problems caused by that.48 John Hill has argued that it has become “impossible to talk about

British cinema in the 1980s without taking some account of how it was engaged in an ongoing dialogue with Thatcherite ideas, meanings, and values.”49 If Gossip was to be looked back on as a satirical attack on cut-throat capitalism in early-80s Britain, and the social abandon it facilitated, even is this was a theme stressed more in some screenplay drafts than others, then it could be argued that the film’s own scandalous demise at the hands of fraud and deception transforms it from observations thrown from the sidelines, to a more fully-involved series of statements about film production in Britain in that context. All films can be read at some level as a story about their own making, and Gossip is a film whose production history now supersedes the story it had set out to tell.

Works Cited

Anon. “Martini on the Rocks.” Private Eye, 30 December 1983. Bilbow, Marjorie. “Boyd’s Heroine is First of Four Picture ‘Virgin

Package.’” Screen International, 9 November 1985, 15, 23. repay the money owed from Gossip in instalments over three years, as reported on 21 August 1985 in The Times. It wasn’t until the following month that a deal was struck with the FFU to repay the £250,000 owed, allowing Heroine to go ahead unchallenged. 47 Don Boyd, interview with the author, 30 November 2004. 48 Don Boyd, interview with Guy Phelps, 11 October 1984, The Don Boyd Collection, file no. DBC 337. 49 Hill, British Cinema in the 1980s, xi.

CHAPTER NINE

194

Clark, Al. “Gossip: A Cautionary Tale.” A.I.P. no.52 (March 1984): 16-19. Coleridge, Nicholas. “The Best Place to Shoot the Gossips.” The Evening

Standard. 2 August, 1982. Hill, John. British Cinema in the 1980s: Issues and Themes. Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1999. Ilott, Terry. “Boyd in Top-line Return to UK Scene.” Screen International,

24 August 1985. Leavy, Geoffrey and Richard Kay. “Nigel Dempster: King of the Gossip

Columnists.” The Daily Mail. 13 July 2007. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

North, Dan. “Don Boyd: The Accidental Producer.” In Seventies British Cinema, edited by Robert Shail. Forthcoming. London: BFI, 2008.

Tolkin, Michael. The Player. London: Faber, 1988. Walker, Alexander. National Heroes: British Cinema in the Seventies and

Eighties. London: Harrap, 1985. Walker, John. The Once and Future Film: British Cinema in the Seventies

and Eighties.