Do Differences Make the Heart Grow Fonder? Associations Between Differential Peer Experiences on...

Transcript of Do Differences Make the Heart Grow Fonder? Associations Between Differential Peer Experiences on...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttp://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vgnt20

Download by: [University of Missouri-Columbia] Date: 22 October 2015, At: 11:34

The Journal of Genetic PsychologyResearch and Theory on Human Development

ISSN: 0022-1325 (Print) 1940-0896 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vgnt20

Do Differences Make the Heart Grow Fonder?Associations Between Differential PeerExperiences on Adolescent Sibling Conflict andRelationship Quality

Kelly Bassett Greer , Nicole Campione-Barr , Brina Debrown & CynthiaMaupin

To cite this article: Kelly Bassett Greer , Nicole Campione-Barr , Brina Debrown & CynthiaMaupin (2014) Do Differences Make the Heart Grow Fonder? Associations Between DifferentialPeer Experiences on Adolescent Sibling Conflict and Relationship Quality, The Journal ofGenetic Psychology, 175:1, 16-34, DOI: 10.1080/00221325.2013.801336

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2013.801336

Accepted author version posted online: 22Oct 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 241

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 1 View citing articles

THE JOURNAL OF GENETIC PSYCHOLOGY, 175(1), 16–34, 2014Copyright C© Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 0022-1325 print / 1940-0896 onlineDOI: 10.1080/00221325.2013.801336

Do Differences Make the Heart Grow Fonder? AssociationsBetween Differential Peer Experiences on Adolescent

Sibling Conflict and Relationship Quality

Kelly Bassett Greer, Nicole Campione-Barr, Brina Debrown, and Cynthia MaupinUniversity of Missouri

ABSTRACT. Though it is known that different familial relationships influence one another (e.g., Yu& Gamble, 2008) the influence of outside relationships (i.e., peers) on family dynamics (i.e., siblingrelationships) is less clear. Thus, the authors examined the association differential peer experienceshad on the conflict frequency, conflict intensity, and relationship quality of the sibling relationship.A 1-year longitudinal design measured first-born siblings in Grades 8, 10, and 12 along with theirsecond-born siblings. In the first year, participants were brought to the university to complete ques-tionnaires and in the following year, siblings again participated by completing online questionnairesat home. Results partially confirmed the study hypotheses that adolescents would show greater siblingconflict and poorer relationship quality with greater peer group differences, revealing that when peergroup differences between siblings were greater, the youngest siblings reported more intense siblingconflicts (pe = –.10 p < .05), the oldest siblings reported greater relationship positivity (pe =.13 p < .05), and the oldest second-borns reported greater relationship negativity (pe = –.12p < .10). These findings underscore the importance of investigating siblings’ differential experi-ences beyond familial influence to focus on outside sources to better understand developmentalfluctuations in siblings’ relationships.

Keywords conflict, differential experiences, peers, relationship quality, siblings

Though a variety of past research has focused on the importance of within family influences onfamily outcomes (e.g., marital to child and parent to child; Brody, Stoneman, & Burke, 1987;Buhrmester, 1992; Yu & Gamble, 2008), little research has examined influences exterior tothe family on the family unit. Additionally, though marital and parent–child relationships havebeen widely investigated (e.g., Smolak & Levine, 2001), less is known about the influence ofother social relationships on the sibling relationship, particularly during adolescence (Kramer& Bank, 2005). Given that as individuals move into adolescence and their desire for expandedautonomy increases their exposure to friends and peers (Boer & Dunn, 1992; Rubin, Bukowski, &Parker, 2006; Smetana, 2011) and that peers become an important social influence for individualsduring adolescence (Cicirelli, 1995; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), examining peers as an outside

Received October 15, 2012; accepted April 29, 2013.Address correspondence to Nicole Campione-Barr, University of Missouri, Psychological Sciences, 210 McAlester

Hall, Columbia, MO 65211, USA; [email protected] (e-mail).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 17

influence on the sibling relationship provides insight into the interactions among adolescents’close relationships. Furthermore, understanding how siblings are uniquely influenced by theirvarying peer groups provides greater understanding of how differing sibling experiences canimpact the health and well-being of the sibling relationship. That is, as siblings move intoadolescence, it is likely that each individual experiences different peer groups from that of his/hersibling and these differences might contribute to the level of conflict and relationship qualitythat siblings experience. Thus, the aims of the present study were to (a) examine differences insiblings’ differential peer experiences throughout adolescence and (b) investigate how siblingdifferential peer experiences impact sibling conflict and relationship quality one year later.

Several studies have assessed important connections between peers and siblings. For instance,in a study of middle childhood youth (age 6–12 years old), children that did not have a siblingwere more likely to be the victims of peer aggression and also the instigators of aggressionamong peers compared to children that had at least one sibling (Kitzmann, Cohen, & Lockwood,2002). This study suggested that the sibling relationship appeared to be a significant avenue forlearning conflict strategies and social skills that then related to better adjustment among peers(Kitzmann et al., 2002). Additionally, relationship quality within the sibling relationship has beenassociated with adjustment among peers (Lockwood, Kitzmann, & Cohen, 2001). For example,children who experienced high levels of warmth within their sibling relationship were morelikely to experience positive peer outcomes (i.e., increased perceived popularity and decreasedvictimization by peers) whereas sibling relationships that were more characterized as conflictivewere associated with more negative peer outcomes (i.e., peer rejection; Lockwood et al., 2001).Similarly, a study conducted with aggressive first- and second-grade children showed that childrenwho experienced greater conflict in their sibling relationships were more disliked by peers thanchildren who had greater warmth and less conflict in their relationships (Stormshak, Bellanti, &Bierman, 1996). Each of these studies shows that siblings and peers do not function on independentplanes, and do indeed influence one another. Though these studies highlight connections betweensiblings and peers, they focus on qualities within the sibling relationship being associated withadjustment among peers. The present study proposes that the reverse is also likely; that qualitieswithin the peer relationship (i.e., differences among siblings’ peer group characteristics) mayalso be associated with the functioning and quality of sibling relationships. As siblings move intoadolescence, they should experience even more opportunities for peer interactions as peers becomea more significant part of adolescents’ lives (Rubin et al., 2006). Additionally, these studies did notassess differential experiences among siblings. How siblings experience nonshared environmentsoutside of the sibling relationship (i.e., within peer relationships) may be particularly relevant forthe adolescent sibling relationship. That is, past research has shown that individuals tend to veertoward different peer groups than their siblings (Manke, McGuire, Reiss, & Hetherington, 1995),making peer differential experiences a potentially relevant issue for adolescent siblings. Indeed,in the Manke et al. study, 10–18-year-old same-sex sibling pairs were assessed by examininggenetic and environmental contributions to their social experiences outside of the family (i.e.,with teachers and friends). The study found that the environmental influences associated withinteractions with teachers and friends were mostly nonshared, suggesting that when siblings’engaged with their friends (and teachers), these sibling experiences differed from one another(Manke et al., 1995).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

18 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

Past research has highlighted the importance of siblings’ expansion of their nonshared en-vironments (e.g., experiencing individual differences with parents) as they get older in order todistinguish themselves from other family members by creating exclusive niches (Sulloway, 1996)or by deidentifying from one another in order to maintain uniqueness (Whiteman & Christiansen,2008; Whiteman, McHale, & Crouter, 2007). One significant avenue of expanding an individual’snonshared environment occurs during adolescence, when individuals increase their focus on rela-tionships outside of the family (e.g., peer development; Rubin et al., 2006). Given that peer groupdifferences are common among siblings (Manke et al., 1995) and that siblings desire to increasetheir nonshared experiences as they get older to distinguish themselves from each another (e.g.,Whiteman et al., 2007), peer differential experiences should impact the sibling dyad.

What remains unclear is how differences within siblings’ peer groups may be associated withoutcomes within the sibling relationship (i.e., sibling conflict and relationship quality). In regardsto sibling differentiation in association with peers, differences in siblings’ intimacy have beenassociated with the level of differences among siblings’ peers (McGuire & Segal, 2012). In thisstudy, siblings age 8–12 years old were assessed on their percentage of peer network overlap(children were asked to list their friends and then list the number of those friends that overlappedwith their sibling) and the quality of their sibling relationship. Results found that siblings higher inwarmth or intimacy tended to have less difference between their peer groups (i.e., siblings sharedmore friends; McGuire & Segal, 2012). Although these authors examined sibling relationshipquality to peer differences, it could be that the reverse is also true; differences in peer groups mayalso relate to relationship quality in the sibling dyad. Kretschmer and Pike (2010) also conductedresearch examining siblings’ differential peer experiences. This research conducted with ado-lescent siblings showed that differences among siblings’ peer groups (i.e., friendship positivity,emotional support from friend, and self-disclosure from friend) were associated with differencesin siblings’ aspirations (i.e., self-acceptance and being affiliated with significant others such as adating partner) suggesting that siblings’ nonshared experiences exterior to the family (i.e., peergroups) were associated with differences among siblings (Kretschmer & Pike, 2010). Thoughthis study assessed differential experiences in peer networks to sibling differences, it did notassess how those peer differences were associated with the well-being of the sibling relationship.Thus, the McGuire and Segal and Kretschmer and Pike studies suggest that sibling nonsharedenvironments outside of the family context (i.e., within peer relationships) are important in under-standing associations with siblings’ adjustment and differences among siblings. Though helpfulcontributions, neither of these studies examined the direction of effects between differential peergroups to the adjustment of each sibling or the quality of the sibling relationship. Addition-ally, these studies did not assess the sibling relationship in terms of both siblings’ perspectiveson differential peer experiences on their own outcomes and the influences of each individual’sperceptions of differential experiences on the other siblings’ outcomes. In the present study weaimed to clarify these associations. Thus, given the increased importance of peer relationshipsas children move into adolescence (Rubin et al., 2006) and previous associations with individualadjustment, sibling relationship quality, and peers (McGuire & Segal, 2012), examining differen-tial peer-group characteristics should bring more salience to nonshared experiences siblings havebeyond the family and further clarify how these differences are associated with the well-being ofsiblings.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 19

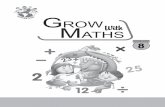

Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling

A principle contribution of the present study is the use of Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling(APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) that allows for the examination of both dyad members’perspectives on differential peer experiences, conflict, and relationship quality. Previous researchon siblings has often focused on one perspective (e.g., Howe, Aquan-Assee, Bukowski, Rinaldi,& Lehoux, 2000) or an average rating of siblings’ reports (e.g., Richmond & Stocker, 2009).Given the nested nature of dyadic data, where siblings are nested within the family and alsoexpected to influence each another, APIM is a breakthrough approach that most accuratelyanalyzes dynamics occurring within dyadic data. Therefore, the present study contributes to amore accurate perception of the sibling relationship by maintaining the independence of eachperson within the dyad. Thus, in the present study, APIM can clarify the association between anadolescent’s own perception of his/her peer group characteristics on that individual’s perception ofconflict and relationship quality with the sibling (see Paths A and B in Figure 1) but also illuminatethe association between the other dyad member’s perception of conflict and relationship qualityas a result of the individual’s peer group characteristics (see Paths C and D in Figure 1). As aresult of the use of APIM, both actor (adolescent or within individual) and partner (sibling oracross the dyad) effects should be present for the main hypothesis. Thus, Paths A and B respond tothe actor (i.e., individual’s perceptions of differential peer groups to the individual’s adjustment)effects and Paths C and D respond to the partner (i.e., siblings’ perceptions of differential peergroups to individual’s adjustment) effects. In the present study we hypothesized that the actor andpartner effects for differential peer experiences would be similar. Therefore, regardless of whomperceives greater peer group differences (adolescent or sibling), given that it is likely important

FIGURE 1 Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Note. Solid lines (A and B) represent actor effects. Dash lines (Cand D) represent partner effects.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

20 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

to be both the one that experiences differences in siblings’ peer groups and feels the effects ofthis differentiation personally and also to be the one that perceives these differences and thereforeinfluences his or her partner’s perceptions of the relationship, the actor and partner effects shouldbe similarly important for the outcomes.

Hypotheses

Thus, given the structure of APIM, the present study tests the associations between both siblings’differential peer experiences with sibling well-being (from both the actor and partner perspective).Based on past research, there do appear to be connections between differential experiences withinthe sibling and peer domains (Kretschmer & Pike, 2010; McGuire & Segal, 2012), althoughthis work has primarily focused on siblings’ differential experiences relating to peer outcomes.What is still unclear is how differential peer influences might be associated with sibling conflictand relationship quality. Broader work on sibling differentiation gives some implications forhow differences experienced by siblings might be associated with individual adjustment andsibling relationship quality. Research of early adolescents suggests that as siblings differentiate,relationship negativity increases (i.e., greater conflict; Brody et al., 1987). In seeming oppositionto this, Sulloway (1996) posited that increased niche-building (i.e., creating greater nonsharedexperiences) decreases sibling competiveness and contentiousness over time as a result of fewershared resources. Thus in the present study we tested two main hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 wasthat adolescents would report higher (more frequent and intense) conflict, more relationshipnegativity, and less relationship positivity with greater differential peer experiences (actor effects,see Paths A and B in Figure 1). Hypothesis 2 was that siblings’ perceptions of greater peergroup differences would also be associated with adolescents’ higher (more frequent and intense)conflict, more relationship negativity, and less relationship positivity (partner effects, see Paths Cand D in Figure 1).

Moderating Variables

In addition to the two hypotheses presented, the associations between differential peer experi-ences with sibling conflict and relationship quality can be further explained with three potentialmoderators. That is, these direct associations may differ in degree or strength based on siblingordinal position, age, and sex composition (see Path E in Figure 1). It is possible that increases innonshared peer environments produce facets of both negativity and positivity within the siblingrelationship based on changes in siblings’ ordinal position or age (based on previous researchsuggesting that siblings might report either negative or positive outcomes depending on theirage or ordinal status; Buhrmester & Furman, 1990; McHale & Crouter, 1996). At younger ages,siblings’ increased differential peer experiences may create more conflict and relational nega-tivity (Brody et al., 1987) as younger adolescents (in terms of chronological age) as well aslater-born siblings (in terms of ordinal position within the family) are generally more investedin the sibling relationship than older adolescents and earlier-born siblings (Buhrmester & Fur-man, 1990; McHale & Crouter, 1996). Furthermore, later-born siblings’ attachment bond to their

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 21

earlier-born siblings is stronger than the reverse (Bank, 1992) and therefore fluctuations in thesibling relationship based on differences should impact younger and later-born siblings more thanolder and earlier-born siblings as they may perceive differences in peer group associations as anindication of distancing themselves from their sibling or the qualities that are important to theirsibling. Therefore, the relationship between sibling reports of peer differences and the conflictand relationship quality outcomes should be moderated by specific demographic variables (seePath E in Figure 1). That is, the association between peer differences and outcomes should havea stronger relationship for some siblings compared to others based on differences in ordinal po-sition, age, and sibling sex composition. Thus, the relationship presented in the main hypothesis(for both actor–adolescent and partner–sibling effects) would be moderated by ordinal positionwhere second-borns should show a stronger relationship between the associations than first-borns(Hypothesis 3) given that later-borns are often more invested in the sibling relationship (Bank,1992; Buhrmester & Furman, 1990; McHale & Crouter, 1996) and therefore perceivably moredistressed by increased sibling differentiation than earlier-borns. As siblings age and create theirown peer niches (Rubin et al., 2006) peer differences may help to dampen sibling conflict andnegativity creating more harmony for both older and younger siblings. Therefore, we posited thatthe hypothesized direct associations (i.e., adolescent perceptions of differential peer experiencesto individual conflict frequency and intensity) would be stronger for younger than older siblings(Hypothesis 4). Given the structure of actor–partner interdependence modeling, position withinthe family and age would be tested in tandem. As a result of position and age being inherentlyconfounded, both variables will be entered into the same models and the analyses will parse outthe distinguishing characteristics of each.

Additionally, the sex composition of sibling dyads might foster varying degrees of siblingrelationship quality and conflict given differences in peer groups. In general, same-sex siblingsreport greater companionship, intimacy, and affection than opposite-sex siblings during middleand late adolescence (Buhrmester, 1992). In addition, female adolescents are more investedin social relationships and find intimacy to be particularly important for high quality closerelationships (Cole & Kearns, 2001), and should therefore be affected the most by changes in thequality of the sibling relationship compared to males. Furthermore, sister–sister dyads have themost intense relationships of any other sibling dyad. Thus, though they show the highest levelsof warmth, female-female dyads also show the highest levels of conflict (e.g., Tucker, McHale,& Crouter, 2001). Therefore, it is possible that sister–sister dyads might show greater relationalpositivity and conflict compared to other dyadic constellations. Thus, we hypothesized that therelationship presented in the main hypothesis (for both actor–adolescent and partner–siblingeffects) would be moderated by sibling sex composition in which sister–sister dyads would showa stronger relationship between the associations than the other three sibling sex compositions(Hypothesis 5). Based on this model, the hypotheses would be analyzed from both siblings’perspectives by simultaneously taking into account Paths A, B, C, and D with the addition of themoderating influences of ordinal position, age, and sibling sex composition according to Path E(see Figure 1).

Taken as a whole, the present study extends our present understanding of adolescent sib-ling relationships by (a) examining an understudied aspect of siblings’ nonshared environ-ments (i.e., differential peer experiences), (b) expounding on our understanding of changesin siblings’ relationships throughout adolescence by examining both siblings’ perspectives,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

22 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

and (c) clarifying the moderating roles of sibling ordinal position, age, and sex com-position.

METHOD

Participants

First-born adolescents along with their second-born siblings from 145 dyads participated. Indi-viduals in Grades 8, 10, and 12 were recruited for the study. Those individuals who were thefirst-born in their family with a sibling within 5 years of age (the sibling had to be the second-born child in the family) were eligible to participate. Eligibility for the study also required allsiblings to be living in the same home the majority of time and for participating siblings tobe biological (either full or half siblings). Siblings were recruited with relatively equal divi-sion among the four gender compositions (brother–brother = 35, sister–sister = 43, brother–sister = 29, sister–brother = 38) and age cohorts (Grade 8 = 53, Grade 10 = 56, and Grade12 = 36 with their closest-in-age younger siblings). First-born siblings were 12–18 years old (Mage = 14.97 years, SD = 1.69 years) and second-born siblings were 9–17 years old (M age =12.20 years, SD = 1.90 years). The mean age difference between siblings was 2.77 years. Parentsprovided the majority of demographic information. The sample primarily included EuropeanAmericans (91.7%), with the remaining families African American (5.6%) or other ethnicities(2.8%). The majority of parents reported being married with both birth parents still intact (75.2%),6.9% of families were blended, 14.5% of parents reported being divorced or separated, and 3.5%of parents were single. Just under half of the parents indicated a college degree, 43.1% (29.2%with a graduate degree and 22.2% with some college experience). The median income familiesreported was between $70,000–84,000 (13.2%). The majority of parents that attended the labsession were mothers (139 mothers).

One year later, 127 of the original 145 families were assessed again (an attrition rate of 12%).Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare the families who participated at bothtime points with those who did not on ethnicity, marital status, education, income, as well asstudy variables at Time 1. Families from both time points were not significantly different on anydemographic or study variables. At Time 2, 19 of the first-born adolescents had gone to college.Analyses were initially run controlling for sibling living together status, but this control was notsignificant in any analyses and, therefore, dropped.

Given the lack of differences between time points, data were likely missing at random andtherefore, the Expectation Maximization procedure in SPSS was utilized in order to retain theuse of all data for analyses.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from local schools within a small Midwestern city through rosterinformation given by each school district. Letters outlining the purpose of the study and eligibilitywere mailed out to all families (3,027 families total). Families who were interested in participatingwere encouraged to call or email the investigators. Several weeks after the letters were mailed,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 23

families that had not contacted the lab were called to see if they were interested and eligibleto participate. Of the total families contacted, 5% of the sample that was approached and meteligibility criteria agreed to participate. As part of a larger study, families participated at theuniversity lab where adolescents completed questionnaires, had one-on-one interviews withtrained investigators, and participated in videoed sibling interactions (only the questionnaire datawas utilized for the present study). Three separate adjacent rooms were used for the study, with acomputer in each room. Siblings were put into separate rooms to complete questionnaires onlinewhile the parent attending the study completed questionnaires in the third room. Investigatorsstayed in the hallway outside of the rooms to answer any questions. For the present study, siblingscompleted questionnaires about their perceptions of their peer group compared to their sibling’s,the frequency and intensity of conflict with their sibling, and the quality of their relationship withtheir sibling. Families were paid $40 for their participation at Time 1.

At Time 2, families completed questionnaires from home (either via the Internet or with papercopies; 26% of families requested paper-based questionnaires). All of the original 145 familieswere initially contacted for participation at Time 2 through mailed letters home and phone calls.Families that choose to participate a second time were asked to return their questionnaires attheir earliest convenience. Honoraria were paid to the families ($10 per person) at Time 2.Studies for Time 1 and Time 2, as well as the broader study, were approved by the universityInstitutional Research Board and were in accord with all American Psychological Associationethical standards.

Measures

Sibling differential peer group experiences

The Sibling Inventory of Differential Experiences scale (SIDE; Daniels & Plomin, 1985)was initially used to measure sibling differential experiences in four different domains: siblinginteraction qualities, parental treatment, peer group characteristics, and events specific to theindividual (a 73-item measure). Given that our goal was to investigate differential experienceswithin siblings’ peer groups, we chose to focus specifically on this domain (a 26-item subscale;assessed only at Time 1). This domain assessed individuals’ ratings of their peers’ orientationtoward college, delinquency, and popularity compared to their siblings’ peer group. Siblingsinitially rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (my sibling’s friends much more thanmy friends) to 5 (my friends much more than my sibling’s friends). Sample items included “areresponsible,” “are college-oriented,” and “are apart of the ‘bad’ group.” The original scoring wasa relative scoring that provided information concerning the amount (e.g., “whose friends are morepopular?” in which a response closer to 1 or 5 would indicate a greater amount of differencewhereas a response closer to 3 would indicate less difference between siblings’ peer groups) anddirection (i.e., a score closer to a 1 would indicate the sibling’s friends held these characteristicsmore whereas a score closer to a 5 would indicate that the individual’s friends were much morecharacteristic of the trait being assessed) of differential experiences. As outlined by Daniels andPlomin, items were rescored for an absolute score in which the amount of differential experienceswas focused on to the exclusion of the direction of differences (e.g., how much difference thereis between peer popularity of the individual’s and the sibling’s peer groups; Daniels & Plomin,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

24 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

1985). This scoring was on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (no difference in siblingexperiences) to 2 (much difference in sibling experiences) to assess difference. Thus, a relativescore of 3 was coded as 0 (no difference), relative scores of 2 and 4 were coded as 1 (a bit ofdifference in sibling experiences), and relative scores of 1 and 5 were coded as 2 (much differencein sibling experiences). Cronbach’s alpha values for Time 1 for first- and second-borns were .89and .91, respectively. Separate mean scores for older and younger siblings were used in the finalanalyses. A higher score equals greater differences in peer group experiences.

Sibling conflict

The Sibling Issues Checklist (Campione-Barr & Smetana, 2010), a 20-item assessment, mea-sured siblings’ conflict frequency and intensity, each on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not atall/calm), to 5 = (often/very angry) over a variety of issues was assessed at Time 1 and oneyear later at Time 2. Participants were first asked how often, within the last two weeks, eachtopic was discussed and then were asked how hot or intense these discussions were over thesame items. Sample items included “going into other’s room without asking” and “whose turn itis to do chores.” Cronbach’s alpha values for Time 1 and Time 2 for conflict frequency rangedfrom .75 to .84, and for conflict intensity from .70 to .87. Separate mean scores for older andyounger siblings’ conflict frequency and intensity were used in final analyses. A higher scoreequals greater frequency/intensity of conflict. While conflict frequency and intensity were highlycorrelated (see Table 1), these constructs were kept separate due to previous research showingfrequency and intensity to have different developmental trajectories (Laursen, Coy, & Collins,1998) and relationship consequences (Montemayor, 1983) in parent–child relationships.

Sibling relationship quality

The Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985) is a 33-itemmeasure and was used to assess the quality of the sibling relationship (assessed at Times 1 and2). The measure includes 11 relationship quality subscales that load on three factors: support,negativity, and relative power, as shown in previous research (Adams & Laursen, 2007). Giventhat the emphasis of the present study was relationship quality, only positivity and negativitywithin the relationship were utilized, and therefore 24 items for support/positivity and 6 itemsfor negativity were extracted. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (littleor none) to 5 (the most). Sample items included “How much free time do you spend with thisperson?” and “How much do you and this person get on each other’s nerves?” Separate meanscores for older and younger siblings’ relationship positivity and negativity were used in the finalanalyses. Cronbach’s alpha values for Times 1 and 2 were .95 (relationship positivity) and .90–.95(relationship negativity) for older and younger siblings.

As mandated by the structure of APIM, every participant’s individual scores for each measurewere used in analyses. Thus, each sibling within the dyad maintained individuality to test thedirect associations between an individual’s differential experiences to that individual’s outcomes,but also to test the individual’s differential experiences to the sibling’s outcomes.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 25

TABLE 1Correlations Among Differential Peer Experiences, Conflict, and Relationship Quality

M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 M SD

1. Sibling peer groupdifferences

0.57 0.37 — −.02 −.01 .02 .00 −.33∗∗ −.24∗∗ .19∗ .16∗ 0.65 0.36

2. T1 Conflictfrequency

2.10 0.65 .18∗ — .58∗∗ .80∗∗ .58∗∗ .09 .01 .38∗ .45∗∗ 2.30 0.65

3. T2 Conflictfrequency

1.84 0.59 .17∗ .61∗∗ — .49∗∗ .85∗∗ .05 −.02 .42∗∗ .61∗∗ 1.78 0.54

4. T1 Conflictintensity

1.86 0.64 .24∗∗ .84∗∗ .48∗∗ — .55∗∗ .01 −.12 .39∗∗ .37∗∗ 2.01 0.61

5. T2 Conflictintensity

1.68 0.63 .25∗∗ .51∗∗ .80∗∗ .42∗∗ — .05 −.06 .37∗∗ .61∗∗ 1.65 0.54

6. T1 Relationshippositivity

3.23 0.78 −.32∗∗ .04 −.04 .02 −.10 — .68∗∗ −.12 −.05 3.15 0.80

7. T2 Relationshippositivity

3.10 0.80 −.18∗ .02 −.14 −.07 −.19∗ .45∗∗ — −.11 −.12 3.00 0.72

8. T1 Relationshipnegativity

2.77 1.05 .13 .42∗∗ .35∗ .44∗∗ .32∗∗ −.15 −.08 — .70∗∗ 2.70 0.97

9. T2 Relationshipnegativity

2.74 1.08 .09 .35∗∗ .48∗∗ .30∗∗ .53∗∗ −.10 −.20∗ .56∗∗ — 2.66 1.00

Note. Older siblings are above the diagonal. Younger siblings are below the diagonal. Means are uncentered scores.Bolded text indicates significant correlations. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Correlational analyses were run to compare differential peer experiences with conflict frequency,conflict intensity, and relationship quality (positive and negative) separately for younger andolder siblings (see Table 1). Greater peer group difference between siblings were moderately andpositively associated with conflict for younger siblings revealing that the greater the differencesbetween siblings’ peer groups, the more frequent (T1 r = .18 [p < .05]; T2 r = .17 [p < .05]) andintense (T1 r = .24 [p < .01]; T2 r = .25 [p < .01]) younger siblings reported their conflicts beingat both time points. Greater peer group differences were also moderately negatively associatedwith relationship positivity for both older (T1 r = –.33 [p < .01]; T2 r = –.24 [p < .01]) andyounger (T1 r = —32 [p < .01]; T2 r = –.18 [p < .05]) siblings such that the greater the differencesbetween siblings’ peers, the less positivity both siblings reported at both time points. There wasalso a low positive correlation between peer groups and relationship negativity relating greaterdifferences between siblings’ peer groups with more negativity (reported by older siblings; T1r = .19 [p < .05]; T2 r = .16 [p < .05]). All Time 1 variables were moderately to highly positivelycorrelated to their corresponding Time 2 variables, showing that the more conflict or relationshippositivity/negativity siblings reported initially, the more conflict frequency (older siblings r = .58[p < .01]; younger siblings r = .61 [p < .01]), conflict intensity (older siblings r = .55 [p < .01];younger siblings r = .42 [p < .01]), positivity (older siblings r = .68 [p < .01]; younger siblingsr = .45 [p < .01]), or negativity (older siblings r = .70 [p < .01]; Younger Siblings r = .56

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

26 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

[p < .01]) they reported one year later, correspondingly. Greater conflict frequency and intensitywere also moderately positively correlated with relationship quality such that the greater theconflict, the more negativity both older (T1 frequency to T1 negativity r = .38 [p < .01]; T2frequency to T2 negativity r = .61 [p < .01]; T1 intensity to T1 negativity r = .39 [p < .01]; T2intensity to T2 negativity r = .61 [p < .01]) and younger (T1 frequency to T1 negativity r = .42[p < .01]; T2 frequency to T2 negativity r = .48 [p < .01]; T1 intensity to T1 negativity r = .44[p < .01]; T2 intensity to T2 negativity r = .53 [p < .01]) siblings reported.

APIM

Due to the nested design of the data (individuals nested within dyadic sibling relationships) andthe important contribution of both individuals within the dyad, the APIM (Kenny et al., 2006)was utilized to test older and younger adolescent siblings’ differential peer group experiences anddyadic (sibling conflict and relationship quality) outcomes (see Figure 1). All parameter estimateswere estimated using Mixed procedures in SPSS 17. One advantage of APIM modeling is theuse of both dyad members’ data and, like multilevel modeling, the true sample size (as it relatesto power estimates) is estimated to be somewhere between the number of individuals (290 inthe present study) and the number of dyads (145 in the present study) within the sample. Giventhat APIM models use both members of a dyad, this produces both actor (within individual) andpartner (across members of the dyad) effects. Within this structure, individuals of a dyad operateas both an actor and a partner. For clarity, hereafter, all actor-effects will refer to adolescents (orboys and girls) and partner-effects will refer to their siblings (or brother or sister). Only significantmain effects and significant or marginally significant interaction effects are discussed in the text.When interactions were tested, significant (or marginally significant) interactions were graphedand simple slopes analyses were calculated for interpretation (Aiken & West, 1991). If higherorder interactions were not significant, they were dropped (along with lower order interactionsassociated with the higher order interaction) and re-run with the lower order interactions inorder to preserve power. Only the highest order interactions were interpreted (e.g., if there was asignificant age by differential peer group experiences interaction and a significant age by sex bydifferential peer group experiences interaction, only the three-way interaction was interpreted).Additionally, only interactions that produced significant slopes were further discussed.

Originally, interactions with adolescent and sibling sex were explored, but were nonsignificantfor all analyses and therefore dropped (though adolescent and sibling sex were kept as controls).Therefore, for each model, three- and two-way interactions were tested with age and ordinalposition (birth order) as possible moderators.

Longitudinal Associations Between Sibling Differential Peer Experiencesand Conflict

Conflict frequency

Analyses in this section tested the association between sibling differential peer experienceson sibling conflict frequency. Both actor (adolescents’ perceptions of differential peer groups

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 27

TABLE 2Standardized Parameter Estimates for Time 1 Differential Peer Group Differences to Time 2 Conflict and

Relationship Quality

Conflict frequency Conflict intensityRelationship

positivityRelationship

negativity

Estimate t Estimate t Estimate t Estimate t

Intercept .76 7.58∗∗∗ .88 8.80∗∗∗ 1.35 7.88∗∗∗ 1.04 7.06∗∗∗Age Actor −.02 −1.15 −.03 −1.80† .01 0.23 −.05 −1.49Sex Actor −.02 −0.86 .00 0.14 .02 0.43 −.04 −0.90Sex Partner .03 0.93 .02 0.70 −.01 −0.35 −.01 −0.12Position Actor −.05 −1.43 .00 0.13 −.04 −0.87 .04 0.73T1Conflict/Relationship

Quality Actor.48 11.03∗∗∗ .41 8.52∗∗∗ .53 10.31∗∗∗ .61 12.05∗∗∗

Peers Actor .13 1.22 .10 1.21 −.04 −0.38 .30 1.56Peers Partner −.04 −0.44 .04 0.42 .02 0.24 −.04 −0.247Position Actor∗Peers Actor .06 0.56 .05 0.38 −.25 −1.69† .25 1.28Age∗Peers Actor −.07 −1.61 −.10 −2.11∗ .13 2.24∗ −.11 −1.45Position Actor∗Peers Partner −.01 −0.06 .06 0.51 .01 0.10 −.02 −0.08Age∗Peers Partner .00 0.05 −.01 −0.27 −.05 −0.96 .02 0.21Age∗Position∗Peers Actor — — — — — — −.12 −1.67†Age∗Position∗Peers Partner — — — — — — .05 0.51

Note. T1 Conflict and relationship quality = Time 1 reports of conflict frequency, conflict intensity, positive relation-ship quality, or negative relationship quality. Peers = Sibling peer group differences. Bolded text indicates significantcontrols, main effects, or interactions. †p < .10. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01.

on adolescents’ own conflict frequency; see Paths A and B in Figure 1) and partner (siblings’perceptions of differential peer groups on adolescents’ conflict frequency; see Paths C and D inFigure 1) effects were tested. Conflict frequency was the dependent variable that was predictedby the control variables of age, adolescent sex, sibling sex, ordinal position, and Time 1 conflictfrequency. Initially three- and two-way interactions were tested but there were no significantinteractions, thus the final model included only the control variables and sibling and adolescentmain effects (see Table 2). There were no significant adolescent or sibling main effects for conflictfrequency.

Conflict intensity

Analyses in this section tested the association between sibling differential peer experienceson sibling conflict intensity. Both actor (adolescents’ perceptions of differential peer groupson adolescents’ own conflict intensity; see Paths A and B in Figure 1) and partner (siblings’perceptions of differential peer groups on adolescents’ conflict intensity; see Paths C and Din Figure 1) were tested. Conflict intensity was the dependent variable that was predicted bythe control variables of age, adolescent sex, sibling sex, ordinal position, and Time 1 conflictintensity. All three-way interactions were dropped due to nonsignificance, therefore, the final

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

28 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

FIGURE 2 Associations between sibling peer group differences and conflict intensity. †p < .10. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p <. 01.∗∗∗p < .001.

model included adolescent and sibling two-way interactions, main effects, and controls (seeTable 2).

There were no adolescent or sibling main effects, but there was a significant adolescent ageby adolescent peer group differences interactions such that the greater the peer group differencesbetween siblings, the more conflict intensity the youngest siblings reported having with theirelder siblings (Hypotheses 1 and 4; actor effect; see Figure 2).

Longitudinal Associations Between Sibling Differential Peer Experiencesand Sibling Relationship Quality

Relationship positivity

Analyses in this section tested the association between sibling differential peer experienceson sibling relationship positivity. Both actor (adolescents’ perceptions of differential peer groupson adolescents’ own relationship positivity; see Paths A and B in Figure 1) and partner (siblings’perceptions of differential peer groups on adolescents’ relationship positivity; see Paths C andD in Figure 1) effects were tested. Relationship positivity was the dependent variable that waspredicted by the control variables of age, adolescent sex, sibling sex, ordinal position, and Time 1relationship positivity. All three-way interactions were dropped due to nonsignificance, therefore,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 29

FIGURE 3 Associations between sibling peer group differences and relationship positivity. †p < .10. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p <.01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

the final model included adolescent and sibling two-way interactions, main effects, and controls(see Table 2).

There were no adolescent or sibling main effects, but there was a marginally significant positionby adolescent peer group differences interaction, although testing the simple slopes revealed onlymarginal differences (Hypotheses 1 and 3). In addition, there was a significant adolescent ageby adolescent peer group differences interaction such that the greater the peer group differencesbetween siblings, the more relationship positivity the eldest siblings reported (Hypotheses 1 and4; actor effect; see Figure 3).

Relationship negativity

Analyses in this section tested the association between sibling differential peer experiences onsibling relationship negativity. Both actor (adolescents’ perceptions of differential peer groupson adolescents’ own relationship negativity; see Paths A and B in Figure 1) and partner (siblings’perceptions of differential peer groups on adolescents’ relationship negativity; see Paths C andD in Figure 1) effects were tested. Relationship negativity was the dependent variable that waspredicted by the control variables of age, adolescent sex, sibling sex, ordinal position, and Time1 relationship negativity. The final model included all three-way and lower order interactions,main effects, and controls (see Table 2).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

30 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

FIGURE 4 Associations between sibling peer group differences and relationship negativity. †p < .10. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p <.01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

There were no significant adolescent or sibling main effects, but there was a marginallysignificant adolescent age by position by adolescent peer group differences interaction such thatthe greater the peer group differences between siblings, the more relationship negativity oldersecond-born adolescents reported (Hypotheses 1, 3, and 4; actor effect; see Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to address the lack of present research examining differentialexperiences beyond the family within the adolescent sibling relationship (Brody et al. 1987;Buhrmester, 1992; Yu & Gamble, 2008) by examining how differential peer group experiencesaffect the sibling relationship. Therefore, the present study longitudinally explored associationsbetween differential peer experiences, sibling conflict, and relationship quality with regard tosibling ordinal position, age, and sex composition of sibling dyads. Overall, results showedthat younger (by age; Hypotheses 1 and 4) and second-born (by ordinal position; Hypotheses 1and 3) siblings consider greater differences in their nonshared environments with older siblings(i.e., differential peer group experiences) to disrupt the sibling relationship (with greater conflictintensity and increased relationship negativity) but that older siblings report more relationshippositivity with greater peer differences (Hypotheses 1 and 4).

The hypotheses that second-born (Hypothesis 3) and younger (Hypothesis 4) siblings wouldexperience greater conflict frequency and intensity, lower relationship positivity, and higherrelationship negativity with greater peer differences were partially confirmed. The youngestsiblings reported higher conflict intensity with greater peer differences and decreased relation-ship quality (the oldest second-borns reported increased negativity with greater peer differences;Hypotheses 3 and 4). This also supports previous research that greater differentiation with early

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 31

adolescent siblings increases relationship negativity (Brody et al., 1987) and that younger siblingstend to be the most affected by differential experiences (McHale, Crouter, McGuire, & Upde-graff, 1995), although both of these studies tested differentiation among parents and children,not differentiation between adolescents and peers. Interestingly, though younger and second-born siblings did not report decreases in positivity, older siblings actually reported increasesin relationship positivity when peer group experiences were greater (Hypothesis 4). Given thatfirst-born older siblings are often the first among the siblings to expand their peer network (e.g.,they enter the school system first and often receive more freedom to spend time with friendsbefore younger siblings), older siblings may not see peer group differences as a problem forthe sibling relationship. Older siblings may view these differences as a key way to distinguishthemselves from younger siblings and develop their own identities. This freedom, or segregatedidentity from younger siblings, may help to decrease any general negativity within the siblingrelationship (e.g., the less our peer groups, and thus our interests, are similar, the less oppor-tunity for conflict). This notion supports previous research by Sulloway (1996) that increasedniche-building decreased sibling competiveness and contentiousness over time. Thus, as sib-lings get older, it appears that greater differences allow for more positivity within the siblingrelationship.

Our hypothesis that sister–sister dyads would report more conflict and decreased relationshipquality with greater peer differences regardless of who was reporting differences (actor or partner),was not confirmed (Hypothesis 5). Nonsignificant gender composition results were surprising,given that past research has shown sex differences with sibling differential experiences (e.g.,Crouter, McHale, & Tucker, 1999). Overall, the issue of expanding peer group differencesappeared to be an issue of ordinal position and age, but not one of sex differences betweensiblings.

Interestingly, none of the significant interactions were for partner effects (sibling’s perceptionof peer group differences on the adolescent’s perception of the sibling relationship; Hypothesis2). This was surprising given that past research utilizing APIM with sibling dyads has shownthat both adolescent and sibling perceptions are significant to the adjustment of both siblings(e.g., Campione-Barr, Greer, & Kruse, 2013). The present study findings appear to suggest thatwithin individual perceptions are most important in this particular instance (Hypothesis 1). It isnot necessarily objective differences in the qualities of the peer group that are important to theactual quality of the sibling relationship, but instead it is the way one dyad member views howsimilar or different his/her peer groups in comparison to their siblings’ are that impacts that dyadmember’s subjective view of the quality of his or her sibling relationship. Thus, it is importantfor us to continue to examine both actor and partner effects within close dyadic relationships sothat we may better understand in what instances effects are particularly impactful only within theindividual versus those that are impactful across the dyad.

In general, peer group differences did not appear to impact the frequency of conflict betweensiblings (Hypotheses 1 and 2). It could be that siblings are not necessarily changing the amountof issues they fight about when peer group differences are greater, but that those conflicts that arepresent become more heated when siblings differ in this area. For instance, younger siblings maygenerally want to spend more time with older siblings but that this issue becomes particularlyheated when older siblings are more insistent on their space when their friends are around. Thatis, when siblings perceive issues as personal (i.e., borrowing another’s clothes without asking,hanging around when the sibling’s friends are present) conflicts over these issues become more

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

32 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

intense because they are seen as an invasion of the individual’s personal space (Campione-Barr& Smetana, 2010).

Considering these results within a developmental context, as older siblings begin to pullaway from the sibling relationship to invest more time in peer relationships (Rubin et al., 2006)younger siblings may view these differences as deteriorating a relationship that they are still eagerto depend on. Though not examined in the present study, due to not following younger siblingsuntil the same age their older siblings were in this study, it is possible that as both siblings becomemore highly engaged with peers, younger siblings will also become less invested in the siblingrelationship. In turn, those differences that once created conflict may become less disruptive andperhaps increase the positivity within the relationship (as was suggested by the eldest siblings)in the present study. Regardless, the present study highlights a differential experience outside ofthe family relationship (peers; Rubin et al., 2006) that has been shown to have an impact on thewell-being of the sibling relationship.

Overall, the present study contributes to our understanding of sibling relationships by ex-amining changes in conflict and relationship quality longitudinally using an analytic design thatcaptures the importance of both the individual and the dyad in the sibling relationship. Despite theimportant contributions of the present study to the literature, there were some limitations as well.Some of the results presented in this study represent marginally significant findings, thus, theseresults should be interpreted with caution. Although some interaction findings were marginal, thesimple slopes that were interpreted were significant, thus leading us to have greater confidencein these effects. Additionally, participants were primarily White and middle to upper-middleclass. Future studies should involve more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples toimprove generalizability. For instance, in Latino cultures, siblings place more emphasis on familytogetherness and caretaking than other cultures (Kao, Romero-Bosch, Plante, & Lobato, 2012),thus, differences in peer group characteristics may have a greater impact on sibling relationshipsin those cultures than in cultures that may emphasize the importance of individual identity. Also,we did not specifically distinguish between those friends that were shared by siblings and thosefriends that were nonmutual, although we did ask them to directly compare the similarities anddifferences of their broader peer group to that of their brother or sister. Since past work has shownthat siblings do share some friends (McGuire & Segal, 2012; Rowe, Woulbroun, & Gulley, 1994),future researchers would benefit from distinguishing between mutual and nonmutual friends ofsiblings. Finally, to fully understand the developmental influences of peer group differences onsibling outcomes, siblings should be investigated for a longer period of time. Ideally, testingsiblings at the point when younger siblings are at the same age that older siblings were whentesting initially began would give a clearer picture of the transitions that siblings may experienceas well as assist in teasing apart the effects of age versus ordinal position.

Importantly, this study may have implications for greater understanding within the family.Previous research has found that sibling conflict is often influenced by relationships outside ofthe sibling dyad, such as marital conflict (e.g., Poortman & Voorpostel, 2009). The present studyalso implicates the influences of relationships exterior to the family (peer relationships) as havingan impact as well, but by a different process. Given the impact that differential experiences outsideof the sibling relationship have on sibling relationship quality, parents may help to facilitate siblingconflict and relationship quality by encouraging an appreciation for spending time in the siblingrelationship (a helpful consideration for younger siblings still wanting to invest in their eldersiblings) while also making separate time with friends important (a helpful consideration for

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

SIBLING DIFFERENTIAL PEER GROUP EXPERIENCES 33

older siblings who want to engage more with peers as they develop their burgeoning autonomy).It is also important for parents to understand the developmental context of sibling relationalstatus in light of these peer differential experiences and view spikes in conflict and relationshipnegativity as a potential temporary perturbation, which may subside again as younger siblingsage.

AUTHOR NOTES

Kelly Bassett Greer received her Ph.D. in developmental psychology at the University of Mis-souri in 2013. Her research interests include adolescent development and sibling relationships.Nicole Campione-Barr is an assistant professor of psychological sciences in the developmentalpsychology area at the University of Missouri. Her research interests generally encompass familyrelationships during adolescence. All authors were at the University of Missouri at the time theresearch was conducted. Brina DeBrown is now a student at St. Louis University. CynthiaMaupin is now a student at the University of Georgia.

REFERENCES

Adams, R. E., & Laursen, B. (2007). The correlates of conflict: Disagreement is not necessarily detrimental. Journal ofFamily Psychology, 21, 445–458. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.445

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Bank, S. (1992). Remembering and reinterpreting sibling bonds. In F. Boer & J. Dunn (Eds.), Children’s sibling relation-

ships: Developmental and clinical issues (pp. 139–151). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Boer, F., & Dunn, J. (1992). Children’s sibling relationships: Developmental and clinical issues. Hillsdale: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, Inc.Brody, G. H., Stoneman, Z., & Burke, M. (1987). Child temperaments, maternal differential behavior, and sibling

relationships. Developmental Psychology, 23, 354–362. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.23.3.354Buhrmester, D. (1992). The developmental courses of sibling and peer relationships. In F. Boer & J. Dunn (Eds.),

Children’s sibling relationships: Developmental and clinical issues (pp. 19–39). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1990). Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence.

Child Development, 61, 1387–1398. doi:10.2307/1130750Campione-Barr, N., Greer, K. B., & Kruse, A. (2013). The impact of different domains of sibling conflict on adolescent

adjustment. Child Development, 84, 938–954. doi:10.1111/cdev.12022Campione-Barr, N., & Smetana, J. G. (2010). Who said you could wear my sweater? Adolescent sibling conflicts and

associations with relationship quality. Child Development, 81, 464–471. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01407.xCicirelli, V. G. (1995). Sibling relationships across the life span. New York, NY: Plenum Press.Cole, A., & Kerns, K. A. (2001). Perceptions of sibling qualities and activities of early adolescents. The Journal of Early

Adolescence, 21, 204–227. doi:10.1177/0272431601021002004Crouter, A. C., McHale, S. M., & Tucker, C. J. (1999). Does stress exacerbate parental differential treatment of siblings?

A pattern-analytic approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 286–299. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.13.2.286Daniels, D., & Plomin, R. (1985). Differential experience of siblings in the same family. Developmental Psychology, 21,

747–760. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.5.747Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks.

Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016Howe, N., Aquan-Assee, J., Bukowski, W. M., Rinaldi, C. M., & Lehoux, P. M. (2000). Sibling self-disclosure in early

adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 653–671.Kao, B., Romero-Bosch, L., Plante, W., & Lobato, D. (2012). The experiences of Latino siblings of children with

developmental disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38, 545–552.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015

34 GREER, CAMPIONE-BARR, DEBROWN, & MAUPIN

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.Kitzmann, K. M., Cohen, R., & Lockwood, R. L. (2002). Are only children missing out? Comparison of the peer-

related social competence of only children and siblings. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19, 299–316.doi:10.1177/0265407502193001

Kramer, L., & Bank, L. (2005). Sibling relationship contributions to individual and family well-being: Introduction tothe special issue. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 483–485. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.483

Kretschmer, T., & Pike, A. (2010). Links between nonshared friendship experiences and adolescent siblings’ differencesin aspirations. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 101–110. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.001

Laursen, B., Coy, K. C., & Collins, W. A. (1998). Reconsidering changes in parent–child conflict across adolescence: Ameta-analysis. Child Development, 69, 817–832. doi: 10.1037/0012-10.2307/1132206

Lockwood, R. L., Kitzmann, K. M., & Cohen, R. (2001). The impact of sibling warmth and conflict on children’s socialcompetence with peers. Child Study Journal, 31, 47–69.

Manke, B., McGuire, S., Reiss, D., & Hetherington, E. M. (1995). Genetic contributions to adolescents’ extrafamil-ial social interactions: Teachers, best friends, and peers. Social Development, 4, 238–256. doi:10.1111/j.1467–9507.1995.tb00064.x

McGuire, S., & Segal, N. L. (in press). Peer network overlap in twin, sibling, and friend dyads. Child Development,.McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (1996). The family contexts of children’s sibling relationships. In G. H. Brody (Ed.),

Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences (pp. 173–195). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C., McGuire, S. A., & Updegraff, K. A. (1995). Congruence between mothers’ and fathers’

differential treatment of siblings: Links with family relations and children’s well-being. Child Development, 66,116–128. doi:10.2307/1131194

Montemayor, R. (1983). Parents and adolescents in conflict: All families some of the time and some families most of thetime. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 3, 83–103. doi:10.1177/027243168331007

Poortman, A., & Voorpostel, M. (2009). Parental divorce and sibling relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 74–91.doi:10.1177/0192513×08322782

Richmond, M. K., & Stocker, C. M. (2009). Associations between siblings’ differential family experiences and differencesin psychological adjustment. European Journal of Developmental Science, 3, 98–114.

Rowe, D. C., Woulbroun, E. J., & Gulley, B. L. (1994). Peers and friends as nonshared environmental influences. In E. M.Hetherington, P. Reiss, & R. Plomin (Eds.), Separate social worlds of siblings: The impact of nonshared environmenton development (pp. 159–173). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In W. Damon & R.M. Lerner (Series Eds.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 3: Social, emotional, andpersonality development (6th ed., pp. 571-645). New York, NY: Wiley.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development: How teens construct their worlds. Cambridge,MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Smolak, L., & Levine, M. P. (2001). Body image in children. In J. K. Thompson & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image, eatingdisorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment (pp. 41–66). Washington, DC: AmericanPsychological Association.

Stormshak, E. A., Bellanti, C. J., & Bierman, K. L. (1996). The quality of sibling relationships and the develop-ment of social competence and behavioral control in aggressive children. Developmental Psychology, 32, 79–89.doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.1.79

Sulloway, F. J. (1996). Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.Tucker, C. J., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2001). Conditions of sibling support in adolescence. Journal of Family

Psychology, 15, 254–271. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.15.2.254Whiteman, S. D., & Chritiansen, A. (2008). Processes of sibling influence in adolescence: Individual and family correlates.

Family Relations, 57, 24–34. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00480.xWhiteman, S. D., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2007). Competing processes of sibling influence: Observational

learning and sibling deidentification. Social Development, 16, 642–661. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00409.xYu, J. J., & Gamble, W. C. (2008). Pathways of influence: Marital relationships and their association with parenting styles

and sibling relationship quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 757–778. doi:10.1007/s10826-008-9188-z

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f M

isso

uri-

Col

umbi

a] a

t 11:

34 2

2 O

ctob

er 2

015