Defining the Historic Landscape on Eastern Santa Rosa Island: Archaeological Investigations at...

Transcript of Defining the Historic Landscape on Eastern Santa Rosa Island: Archaeological Investigations at...

The arrival of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo andhis crew on the California Channel Islands inAD 1542–1543 aboard 3 Spanish ships markedthe beginning of a turbulent period of transi-tion and reorganization for the Chumash andother Native Californians (Wagner 1929). Al -though contacts between southern CalifornianIndian groups and the Spanish were sporadicover the next 200 years, epidemics (Erlandsonand Bartoy 1995, Erlandson et al. 2001) and“crisis cults” (Bean and Vane 1978; Chartkoffand Chartkoff 1984:241) rapidly transformedthe world for native peoples. The construction

of Mission San Diego in 1769 coincided with thebeginning of the Historic Period (AD 1769–1830) and signaled the beginning of an aggres-sive colonization campaign of Alta Californiaby the Spanish. Anthropologists and historianshave consulted ethnohistoric accounts, travellogs, and mission records to document andbetter understand the lifeways of native peo-ples at historic contact and the consequencesof this meeting of different cultures (e.g., Kroe -ber 1925, Heizer 1955, Johnson 1999).

For Channel Island archaeologists, much ofthe Historic Period research has centered on

Monographs of the Western North American Naturalist 7, © 2014, pp. 135–145

DEFINING THE HISTORIC LANDSCAPE ON EASTERN SANTA ROSAISLAND: ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS AT QSHIWQSHIW

Todd J. Braje1,4, Torben C. Rick2, Leslie Reeder-Myers2, Breana Campbell1, and Kelly Minas3

ABSTRACT.—The Chumash village of Qshiwqshiw, located on eastern Santa Rosa Island, is described in ethnographicsources as one of the largest Chumash villages on the northern Channel Islands, with 4 chiefs and 119 baptisms accord-ing to mission records. The village is thought to correlate with 2 archaeological sites (CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87) thatcontain large and dense shell-midden deposits. Despite the importance of these sites for helping understand Late(650–168 cal BP) and Historic (AD 1769–1830) Period Chumash lifeways, only limited surface collections, one small col-umn sample, and 4 radiocarbon dates were previously available, leaving unanswered important questions about thechronology and structure of these sites. To help fill these gaps, we recently excavated, mapped, and obtained severalnew radiocarbon dates for CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87. Radiocarbon dating and artifact analyses demonstrate that CA-SRI-85 served as an important Late Period village that had continued occupation into the Historic Period. Additionalradiocarbon dates and glass beads confirm that CA-SRI-87 was likely the epicenter of Historic Period occupation, buttesting also revealed that the site was occupied about 3000 years ago. The data paint a complex occupational history forboth sites and provide the chronological and spatial context for future investigations into the historical ecology and cul-tural landscape of eastern Santa Rosa Island.

RESUMEN.—El pueblo Chumash de Qshiwqshiw, ubicado en la región oriental de la isla de Santa Rosa, es descritoen las fuentes etnográficas como uno de los pueblos Chumash más grandes de las Islas del Archipiélago del Norte, concuatro jefes y 119 bautismos documentados en registros de la misión. Se cree que el pueblo esta correlacionado con dossitios arqueológicos (CA-SRI-85 y CA-SRI-87) que contienen grandes y densos concheros. En contraste con la impor-tancia de estos sitios para ayudar a entender los estilos de vida de los Chumash durante los Periodos Tardío (650–168 calBP) e Histórico (1769–1830 AD), sólo están disponibles limitadas colecciones de superficie, una pequeña muestra decolumna, y cuatro fechas de radiocarbono, dejando preguntas importantes abiertas sobre la cronología y la estructura deestos sitios. Para llenar estos vacíos de información, recientemente excavamos, mapeamos, y obtuvimos varias nuevasfechas de radiocarbono para CA-SRI-85 y CA-SRI-87. La datación por radiocarbono y el análisis de artefactos demues-tran que la CA-SRI-85 sirvió como un pueblo importante del Periodo Tardío habitado continuamente hasta el PeriodoHistórico. Fechas adicionales de radiocarbono y cuentas de vidrio confirman que CA-SRI-87 muy probablemente fue elepicentro de la habitación de la región durante el Periodo Histórico, pero las pruebas también revelaron que el sitio yaestaba habitado desde hace aproximadamente 3000 años. Estos datos dibujan una historia habitacional compleja paraambos sitios y proporcionan el contexto cronológico y espacial para investigaciones futuras sobre la ecología histórica yel paisaje cultural de la región oriental de la isla de Santa Rosa.

1San Diego State University, Department of Anthropology, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-6040.2Program in Human Ecology and Archaeobiology, Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washing-

ton, DC 20013-7012.3Channel Islands National Park, 1901 Spinnaker Drive, Ventura, CA 93001.4E-mail: [email protected]

135

identifying the roughly 22 or 23 villages (ranch -erías) named by Chumash consultants in thelate 19th and early 20th centuries (Johnson1999, 2001). Two ethnographic sources laid thefoundation for archaeological ground-truthing:mission register data and ranchería locationsas described by Chumash elders Juan EstebanPico (Heizer 1955, McLendon and Johnson1999) and Fernando Librado (Harrington 1913,Johnson 1982, Arnold 1990). Archaeologists haveused radiocarbon dating, identification of metaltools, glass trade beads or other clearly Euro-pean trade goods, and the presence of denseshell-midden deposits and house depressionsto correlate historic rancherías with existing ar -chaeological sites (Orr 1968, Arnold 1990, John -son 1993, 1999, Kennett et al. 2000, Kennett2005:91–104, Rick 2007a, 2007b).

After decades of ethnographic and archaeo-logical research, many of the rancherías havebeen identified with a high degree of certainty.However, inconsistencies between aspects ofthe mission records and ethnohistoric accountshave resulted in some uncertainty about thenames, locations, and number of rancherías athistoric contact. Ethnohistorian and archaeol-ogist John Johnson recently summarized thework of Channel Island archaeologists to ar -chaeologically verify the historic island ranch -erías. He determined that only 2 village loca-tions are “definite,” 9 are “very likely,” 4 are“likely,” 5 are “uncertain,” 2 are “possible,” and1 is “unknown” (Glassow 2010:3.6–3.15). Ques -tions even remain about some rancherías John -son believes to be “very likely.” These includeQshiwqshiw (translated to “bird droppings”),which is thought to be located on the east endof Santa Rosa Island near the mouth of OldRanch Canyon.

Qshiwqshiw is one of the largest islandChumash villages by baptismal counts (n =119) and appears to have had 4 chiefs. John -son and archaeologist Douglas Kennett (1998,2005, Kennett and Conlee 2002) suggest thatCA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87 are the most likelycorresponding archaeological sites. Glass beadshave been found at CA-SRI-87, but only lim-ited fieldwork has been conducted at the 2sites. It remains to be seen whether both siteswere occupied historically or whether onlyCA-SRI-87 was occupied during the HistoricPeriod, with CA-SRI-85 occupied during theLate Period. Here, we discuss our recent field -work at CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87, which

included extensive mapping and excavation ofauger holes and a test unit, and we present aseries of new radiocarbon dates that help de -fine the chronology and occupational historiesof these 2 important sites. Our data form thefoundation for future investigations into thehistorical ecology and ethnobiology of easternSanta Rosa Island.

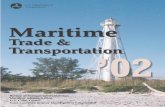

Environmental and Cultural Context

At 217 km2 Santa Rosa Island is the secondlargest of the northern Channel Islands and issituated 44 km off the mainland Santa Barbaracoast, approximately 9 km west of Santa CruzIsland and 5 km east of San Miguel Island(Fig. 1; Schoenherr et al. 1999; Table 1). Muchlike the mainland coast and the other northernChannel Islands, Santa Rosa contains a varietyof marine mammals and a diverse array of ma -rine resources, including intertidal and subtidalshellfish, and nearshore, kelp forest, and pe -lagic fishes. The island supports terrestrial eco -systems, with several perennial streams, highmountain peaks, inland valleys, rolling table-lands, and vegetation communities including is -land chaparral, oak and riparian woodland, andthe Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana insularis).

This rich marine ecosystem and its adequateterrestrial resources attracted the first islandinhabitants some 13,000 (or more) calendar yearsago (Johnson et al. 2002). The number and sizeof archaeological sites increased throughoutthe Holocene as more people occupied islandhabitats (Rick et al. 2005a). During the last 1500years, however, many of the typically Chumashcultural traits, first described by Spanish ex -plorers, took shape. Large coastal villages wereestablished around the island perimeters; plankcanoes (tomols) transported food stuffs, people,and trade items between the island and main-land; shell money beads became the standard-ized trade currency; and hereditary chiefs es -tablished sociopolitical authority (Arnold 2001,Kennett 2005, Rick et al. 2005a). Of the 22 or23 northern Channel Island ethnohistoric vil-lages, 9 were located on Santa Rosa Island,one of which was positioned on the far easternend of the island near the mouth of Old RanchCanyon.

Old Ranch Canyon is the largest drainageon the island and runs in a northwest–south-east direction. At its mouth is a large coastalplain and a small predominately freshwatermarsh that, along with a similar system at the

136 MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN NATURALIST [Volume 7

2014] ARCHAEOLOGY AT QSHIWQSHIW 137

Fig. 1. Map of Santa Rosa Island, the Santa Barbara Channel Islands, and the archaeological sites and geographic fea-tures discussed in the text (base map by L. Reeder-Myers).

TABLE 1. Notes from auger-hole excavations at CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87.

Auger Depth (cm) Notes

CA-SRI-851 52 Possible house depression; fragmented shell visually dominated by Olivella shell2 100 Possible house depression; dense midden with a variety of shell and fish bone3 44 Possible house depression; dense shell midden4 125 Possible house depression; dense midden with abundant shell and bone5 90 Possible house depression; thin midden deposit6 135 Possible house depression; 2 strata, one thin then a thick deposit in the lower 50 cmbs7 89 Possible house depression; thin, moderately dense midden between 50 and 89 cm8 79 Possible house depression; relatively thin midden deposit in loose sandy soil9 84 Possible house depression; thin but dark midden soil from 50 to 84 cm10 70 Dark but thin shell midden beginning at ~50 cm11 135 Dark and dense midden soil at 80–135 cm; no visible house-depression feature12 90 Thick midden throughout auger but no visible house-depression feature13 75 Nearly sterile soil with a few shell fragments in the upper 20 cm14 12 Sterile15 20 Trace shell16 12 One lithic artifact, no shell17 45 Sterile

CA-SRI-871 67 Moderately dense, highly fragmented shell in sandy matrix2 157 Exceptionally dense shell midden in upper 80 cm3 129 Similar deposits to auger 2, with sterile reached at 129 cm4 105 Dense shell midden with abundant shell and bone remains5 62 Highly fragmented but dense midden with abundant shell and Olivella

mouth of adjacent Old Ranch House Canyon,was once a large estuary between about 8000and 5900 years ago (Cole and Liu 1994, Ricket al. 2005b). The mouth of Old Ranch Canyonis flanked by broad sandy beaches to the northand south and a surf-swept sandspit, SkunkPoint, to the north. These habitats foster a va -riety of marine shellfish, seabirds, marine mam -mals, and other organisms. A recent archaeo-logical survey of the entire canyon documented46 archaeological sites with associated radio-carbon dates ranging in age from 8180 to 300cal BP (Rick 2009:25). Even more sites mayexist along the canyon bottoms, but these siteshave not been identified due to heavy sedi-mentary accumulation and the introduction ofdense, invasive grasses during the historicalranching period.

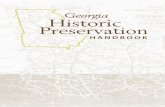

The 2 largest archaeological sites in the OldRanch Canyon watershed are found at its east-ern terminus, CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87 (Fig.2), and are the most likely locations for thehistoric village of Qshiwqshiw. In the 1880s,Pico described Qshiwqshiw’s location at themouth of Old Ranch Canyon, but Johnson (1982)originally suspected that the information wasincorrect and that the village was located tothe northwest at Southeast Anchorage withinBechers Bay. Santa Barbara Museum of Natu -ral History archaeologist Phil Orr (1968) iden-tified a large Late Period village with 10 housedepressions at CA-SRI-77, and Johnson (1982)thought that future fieldwork would produce

artifacts or radiocarbon dates that would con-firm a Historic Period occupation. A substantialhistoric occupation has never been verified atthis site, however, even after repeated visits byKennett (1998:218); and the majority of thedeposits seem to represent Middle (2440–650cal BP) to Late Period occupations and earliersettlement during the Middle Holocene (7500–3500 cal BP).

Orr (1968) also identified house depressionsat the mouth of Old Ranch Canyon at CA-SRI-85. Located directly to the south of thecanyon and bordered by a freshwater marsh tothe north and a sandy beach to the east, CA-SRI-85 is positioned on a small terrace withdeep midden deposits (50–150 cm) visibly erod -ing from the coastal sea cliff and the drainagefront. Much of the site surface is heavily vege-tated with low-lying grasses. When Orr firstrecorded the site, he noted 8 house depres-sions but no other features or artifacts. Orrrecorded the midden at CA-SRI-87 as beingdirectly to the north and separated by approxi-mately 300 m of sandy beach, but he did notreport any features or artifacts. CA-SRI-87 ispositioned immediately beyond a rocky out-crop to the east. Much of the site is coveredby sand and grasses, but dense midden caps asmall dune feature running to the northwest.

During an archaeological survey in the early1990s, National Park Service archaeologistDon Morris identified 8 house depressions and4 glass trade beads at CA-SRI-87. Subsequent

138 MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN NATURALIST [Volume 7

Fig. 2. Locations of CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87, south and north of the mouth of Old Ranch Canyon. For scale refer-ence, CA-SRI-85 is approximately 75 m at its widest point, parallel to the shoreline (by L. Reeder-Myers).

work at the site by Kennett (1998:218, 2005:99) recovered several needle-drilled Olivella1

wall beads and at least one glass bead. Thesefindings confirm that CA-SRI-87 is probablythe location of Qshiwqshiw. However, no ra -diocarbon dates were obtained, and questionsremain about how long the site was occupied.Additional archaeological testing was conductedby archaeologist Ann Munns a little more thana decade ago, but the results of her researchhave not yet been reported. More recent visitsto the site by Rick during 2003–2005 found asite that was well vegetated, with no evidenceof house depressions or other features apartfrom shell midden on the surface.

As part of an effort to document the loca-tion of Historic Period villages across SantaRosa Island, Kennett (2005) obtained 3 radio-carbon dates at CA-SRI-85, along with an ear-lier date run by ichthyologist Carl Hubbs (ascited in Kennett 1998:458), which all suggesteda Late Period occupation. Here, we address 3interrelated research questions: (1) when peo-ple first began to occupy CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87; (2) whether both CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87 were occupied during the Late andHistoric periods; and (3) whether CA-SRI-85was alternatively the locus of a Late Period oc -cupation that was abandoned and relocated toCA-SRI-87 at historic contact.

METHODS

During summer 2012, we visited CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87 to conduct site mapping andsubsurface excavations and to collect shell sam -ples for radiocarbon dating. We worked closelywith Chumash monitors in order to minimizeour impact on these relatively well-preserveddeposits while still obtaining information thatwill assist in understanding the chronologyand structure of these 2 sites. Our fieldworkfocused on mapping the site features, deter-mining the horizontal and vertical extent ofarchaeological deposits, and obtaining marineshell samples for radiocarbon dating from insitu shell-midden deposits. High-precision map -ping was conducted using a laser transit. Topo -graphic data, house-depression locations andsizes, site boundaries, and locations of augersand test units were all recorded, and mapswere drafted using ArcGIS 10.1.

Seventeen auger holes were excavated atCA-SRI-85, along with 5 at CA-SRI-87. Theseholes were positioned to determine the siteboundaries and the depth of site deposits andto obtain radiocarbon samples from various lo -cations at the site. At CA-SRI-85, augers helpedground-truth surface features where possiblehouse depressions are still visible on the surface.All auger samples and a 1.0 × 0.5-m excava-tion unit at CA-SRI-85 were screened over1/16-inch mesh to maximize the collection ofbeads and other small artifacts and ecofacts.

Radiocarbon dates were obtained on singlemarine-shell fragments collected in situ fromsite deposits and were analyzed by the Na -tional Ocean Sciences AMS (NOSAMS) facil-ity at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute orthe DirectAMS facility in Seattle, Washington.To remove any contaminants prior to dating,all specimens were etched in dilute hydro -chloric acid to remove the outer shell layersthat are most susceptible to diagenesis. Speci-mens were then rinsed in distilled water andprocessed according to standard laboratory pro -cedures and methods at NOSAMS or Direct -AMS. All radiocarbon dates, including thoserun by earlier researchers, were calibrated us -ing CALIB 6.0 and the Marine09 calibrationcurve (Reimer et al. 2009); an R of 261 +– 21was applied for all marine samples (see Jazwaet al. 2012:73).

RESULTS

Our field research at CA-SRI-85 helpedidentify the site boundaries and density of sub -surface deposits (Fig. 3). The main site area atCA-SRI-85 is approximately 2060 m2 and isbordered by a freshwater marsh to the northand a sandy beach to the east. The southwest-ern site area is bordered by a thin 990-m2

lithic scatter that is visible within de-vege-tated blowouts.

At CA-SRI-85, auger holes were positionedat the center of possible house depressionsand along 2 perpendicular, linear transects tohelp determine the site boundaries. Nine housedepressions were tentatively identified basedon surface features and the presence of thickmidden deposits that formed a circular shape(Table 1). These features ranged in depth from44 cm to 135 cm, and most contained dense

2014] ARCHAEOLOGY AT QSHIWQSHIW 139

1The genus name for purple olive snail shells has recently changed from Olivella to Callianax. Since Olivella has been used for over 100 years in thearchaeological literature, we will continue to use it for consistency.

deposits of shell and bone, with limited num-bers of artifacts such as chipped stone andwhole and broken Olivella shell. Unfortunately,sea cliff erosion and trampling and erosion fromcattle and sheep grazing may have destroyedor obscured additional house features. The onlyway to confidently determine the exact num-ber of houses will be with large-scale subsur-face excavations that can identify subsurfacehouse floors.

Three new radiocarbon dates were obtainedon well-preserved California mussel (Mytiluscalifornianus) shell collected from the south wallof unit 1 (Table 2). Eleven new radiocarbondates also were obtained from the best pre-served and deepest auger holes at CA-SRI-85.The 1-sigma age range of these dates combinedwith the 4 radiocarbon dates run by earlier re -searchers suggests an occupation at CA-SRI-85 between 1230 and 250 cal BP. To gether, these18 radiocarbon dates indicate a late Middle Pe -riod to Historic Period occupation. The artifact

assemblage recovered from both the auger holesand unit 1 is dominated by Olivella wall andcallus cup beads, Olivella bead-production de -tritus, utilized/retouched flakes, chert cores,micro blades, and microdrills. Though analysisis still ongoing, no clearly European artifactssuch as glass trade beads, needle-drilled beads,or bottle glass have been identified. However,careful measurement of the perforation diame-ters and maximum bevel widths and identifi-cation of perforation types of Olivella wallbeads from CA-SRI-85 will help identify anyneedle-drilled beads from our assemblage (seeGraesch 2001).

The only auger hole to produce a radio -carbon date with a 2-sigma age range clearlywithin the Historic Period was auger 7, takenfrom the possible house depression at the farsoutheastern extent of the site (Fig. 3). The ra -diocarbon chronology suggests that the centraland northwestern portion of the site was occu-pied during the Late Period, with the Historic

140 MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN NATURALIST [Volume 7

Fig. 3. Map of CA-SRI-85 showing the site boundaries and location of possible house features, auger holes, and exca-vation unit (by L. Reeder-Myers).

2014] ARCHAEOLOGY AT QSHIWQSHIW 141

TAB

LE

2. R

adio

carb

on d

ates

from

CA

-SR

I-85

and

CA

-SR

I-87

.a

Con

vent

iona

lC

alib

rate

d ag

eC

alib

rate

d ag

eC

alib

rate

d ag

eSi

te n

o.b

Prov

enie

nce

Lab

no.

Mat

eria

lc14

C a

ge(c

al B

P, 1

sig

ma)

(cal

BP,

2 s

igm

a)(c

al A

D/B

C, 2

sig

ma)

Sour

ce

SRI-

85a

Uni

t 1, 0

–10

cmbs

Bet

a-96

870

Hc

1060

–+60

500–

370

520–

300

AD

143

0–16

50K

enne

tt 1

998

SRI-

85b

Sam

ple

A3,

uni

t 1, 7

0–80

cm

bsB

eta-

1070

44M

c12

70 –+

6064

0–54

068

0–50

0A

D 1

270–

1450

Ken

nett

199

8SR

I-85

cSe

a-cl

iff p

rofil

e, 1

20 c

mbs

Bet

a-10

0513

Mc

1300

–+80

665–

540

750–

490

AD

120

0–14

60K

enne

tt 1

998

SRI-

85d

Aug

er 1

, 47

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

05M

c10

15 –+

3045

0–33

547

0–30

0A

D 1

480–

1650

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85e

Aug

er 2

, 10

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

06M

c11

45 –+

3053

0–47

556

0–44

0A

D 1

390–

1510

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85f

Aug

er 2

, 95–

100

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

07M

c15

45 –+

3088

0–78

091

0–73

5A

D 1

040–

1215

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85g

Aug

er 3

, 25

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

08M

c13

30 –+

3067

0–60

569

0–55

0A

D 1

260–

1400

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85h

Aug

er 4

, 123

cm

bsD

-AM

S 00

2809

Mc

1140

–+30

520–

470

550–

435

AD

140

0–15

15T

his

stud

ySR

I-85

iA

uger

5, 5

0 cm

bsD

-AM

S 00

2810

Mc

1020

–+30

455–

340

475–

305

AD

147

5–16

45T

his

stud

ySR

I-85

jA

uger

6, 5

–10

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

11M

c10

15 –+

3045

0–33

547

0–30

0A

D 1

480–

1650

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85k

Aug

er 7

, 8 c

mbs

D-A

MS

0028

12M

c89

0 –+

2531

0–25

038

0–14

5A

D 1

570–

1805

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85l

Aug

er 8

, 15

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

13M

c10

60 –+

3048

5–41

050

0–33

0A

D 1

450–

1620

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85m

Aug

er 9

, 15

cmbs

D-A

MS

0028

14M

c98

5 –+

2541

0–32

045

0–29

0A

D 1

500–

1660

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85n

Aug

er 9

, 80–

84 c

mbs

D-A

MS

0028

15M

c10

95 –+

3050

0–44

053

0–40

0A

D 1

420–

1550

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

85o

Uni

t 1, 5

–10

cmbs

, Sou

th P

rofil

eO

S-98

749

Mc

1380

–+25

660–

730

700–

640

AD

121

0–13

30T

his

stud

ySR

I-85

pU

nit 1

, 25–

30 c

mbs

, Sou

th P

rofil

eO

S-98

748

Mc

1550

–+20

880–

790

910–

750

AD

104

0–12

00T

his

stud

ySR

I-85

qU

nit 1

, 45–

50 c

mbs

, Sou

th P

rofil

eO

S-98

747

Mc

1880

–+20

1230

–115

012

60–1

100

AD

690

–850

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

87a

Aug

er 2

, 140

–14

cmbs

, Bot

tom

OS-

9874

6M

c36

70 –+

2533

35–3

245

3370

–319

014

20–1

240

BC

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

87b

Aug

er 3

, 5–1

0 cm

bs, T

opO

S-98

745

Mc

815

–+20

250–

145

270–

90A

D 1

680–

1860

Thi

s st

udy

SRI-

87c

Aug

er 3

, ~12

0 cm

bs, B

otto

mO

S-98

744

Mc

995

–+20

420–

330

450–

300

AD

150

0–16

50T

his

stud

ySR

I-87

dA

uger

5, 5

0–53

cm

bs, B

otto

mO

S-98

743

Mc

890

–+30

320–

240

380–

145

AD

157

0–18

10T

his

stud

ya A

n ad

ditio

nal r

adio

carb

on d

ate

(Lab

# L

J-05

14) w

as o

btai

ned

by H

ubbs

from

CA

-SR

I-85

from

cha

rcoa

l in

a he

arth

. The

rad

ioca

rbon

dat

e yi

elde

d a

conv

entio

nal 1

4 C a

ge o

f 970

–+25

0; h

owev

er, w

e ha

ve n

ot in

clud

ed t

his

date

due

to

the

larg

eer

ror

rang

e an

d la

ck o

f pro

veni

ence

info

rmat

ion.

b Let

ters

nex

t to

site

num

bers

cor

resp

ond

to c

alib

rate

d ag

e de

sign

atio

ns in

Fig

. 5.

c Hc

= H

alio

tis c

rach

erod

ii, M

c =

Myt

ilus

calif

orni

anus

.

Period occupations concentrated in the south-ern portion of the site. The midden depositsfrom auger 7 are relatively stable, and the lackof clearly Historic Period artifacts (metal drills,glass beads, bottle glass, etc.) may be best ex -plained by spatial changes during the occupa-tion of CA-SRI-85.

With no house depressions currently visi-ble on the surface at CA-SRI-87, we positionedauger holes along a linear transect, samplingthe thickest shell-midden deposits (Fig. 4). Au -ger samples revealed deep and thick shell-midden deposits, ranging from 62 to 157 cm,many as thick or thicker than those at CA-SRI-85. These results suggest that house fea-tures may exist at CA-SRI-87 but are likelyburied below historic dune sands and thickvege tation cover. Large-scale excavations will bethe only means of positively identifying livingfloors and other domestic features at the site.

Bordered on the east by rocky intertidaland sandy beaches and to the west by wet-lands, CA-SRI-87 measures at least 6750 m2,with the thickest shell-midden deposits likelyconcentrated in a 1230-m2 area. Auger sam-ples produced very few artifacts, other thanfragmented Olivella shell, likely used in beadproduction, and thick accumulations of shelland fish, bird, and sea mammal bone.

Four radiocarbon dates were obtained onwell-preserved California mussel shell frag-ments from CA-SRI-87. Three of the dates,which are from the basal deposits of augers 3and 5 and the top of auger 3, span the Proto-historic (AD 1542–1769) to Historic Periods,ranging in age from 420 to 145 cal BP. Theseradiocarbon dates, the first obtained for CA-SRI-87, combined with the glass trade beadsand needle-drilled Olivella beads recoveredby earlier researchers (Kennett 2005:99), sug-gest that this area was part of the historic vil-lage described by Chumash elder Pico. Thedeposits at the base of auger 2 also produced a1-sigma age range of 3335 to 3245 cal BP, sug-gesting that the site was occupied beginningas early as the early Late Holocene (3500 calBP to present).

CONCLUSIONS

Our mapping, radiocarbon dating, and sub-surface excavations suggest that the historicvillage of Qshiwqshiw likely consists of 2 locali -ties: CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87. The primaryvillage during the late Middle Period to Late Pe -riod was located at CA-SRI-85. During the His -toric Period, Qshiwqshiw was expanded to oc -cupy landforms at CA-SRI-87, with a contracted

142 MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN NATURALIST [Volume 7

Fig. 4. Map of CA-SRI-87 showing the site boundaries and location of auger holes (by L. Reeder-Myers).

historic occupation at CA-SRI-85 concentratedin the southeastern portion of the site. The de -gree of historic land use at CA-SRI-85 is stilluncertain, but the locality seems to primarilybe a Late Period village occupied prior to firstSpanish arrival. Setting aside the 3200-year-old date from CA-SRI-87 that clearly repre-sents an earlier site component, the 2-sigmaradiocarbon age ranges at CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87 suggest a likely Late to Historic Periodland-use scenario at the mouth of Old RanchCanyon. The youngest end of the calibrated

radiocarbon age ranges at CA-SRI-85 and theoldest end at CA-SRI-87 suggest that humanoccupation of the large Late Period village atCA-SRI-85 was contracted right before or wascoincident with first contact with Ca brillo andhis crew in AD 1542 (Fig. 5). Shortly there-after, during the more than 200-year pe riodbetween first contact and the beginning of theCalifornia Mission Period, CA-SRI-85 was oc -cupied by a smaller community concentratedin the southeastern portion of the site, with theepicenter of the historic village of Qshiwqshiw

2014] ARCHAEOLOGY AT QSHIWQSHIW 143

Fig. 5. Radiocarbon chronology for CA-SRI-85 and CA-SRI-87. One- and 2-sigma age ranges are expressed in cali-brated years AD (by T. Rick).

established at CA-SRI-87. Determining whetherthis pattern of land use was due to the intro-duction of Old World diseases (see Erlandsonand Bartoy 1995, Erlandson et al. 2001), hu -man impacts on local subsistence resources, orsome other reason will require continued ar -chaeological investigation.

The apparent absence of other potential his -toric village sites on eastern Santa Rosa Islandis also supported by recent radiocarbon datingof most of the shell middens in the Old Ranchvicinity (see Kennett 1998, Rick 2009). Theexception is CA-SRI-700, a rockshelter in OldRanch Canyon that produced needle-drilledbeads and which is a likely satellite locationused by people who lived at CA-SRI-87 orpossibly CA-SRI-85 (Rick 2009).

Our study suggests that historic ChannelIsland villages are located on ideal settingsthat often supported earlier occupations, some-times several millennia before the HistoricPeriod. CA-SRI-87, for example, was first oc -cupied at least 3200 years ago. Similarly,Rick’s (2007b) excavations at the historic vil -lage of Niaqla (CA-SRI-2), located on thenorthwest coast of Santa Rosa Island, pro-duced a radiocarbon date of ca. 4300 cal BPfrom a small midden deposit at the site.Arnold (2001) and colleagues also have identi-fied Chumash villages that were occupiedfrom the Middle Period through Europeancon tact. Because many of the island Chu -mash villages are situated along highly pro-ductive coast lines and are in close proximityto freshwater, it is likely that earlier compo-nents are buried below many of these villagesites.

Our research reaffirms findings by a varietyof other archaeological studies that landscapeuse during the Late and Historic Periods wasdynamic and included more than the largecoastal villages identified in the enthnohistoricrecords. Several sites that have been identi-fied and dated to the Historic Period are un -named by ethnohistoric sources, including rock -shelters on San Miguel (CA-SMI-516; Rick2007a), Santa Rosa (CA-SRI-700; Rick 2011:280), and Anacapa (Rick 2011) Islands and cere -monial shrine sites and temporary campsiteson Santa Cruz Island (Glassow 2010:3.12; Perry2007). Though identifying and ground-truth -ing the large coastal Chumash villages men-tioned in enthnohistoric records will continueto be an important avenue of future research,

archaeologists need to investigate the longerhistory of land use at these sites and considerHistoric Period landscape settlement patternsthat were dynamic and diverse.

The use of relatively low-impact tech-niques—such as intensive radiocarbon dating,detailed site mapping, and auger testing—willcontinue to be a critical part of investigatinglarge Chumash villages on both the islandsand the mainland. These sites represent someof the most important areas for better under-standing the evolution of sociopolitical com-plexity, the anthropogenic impacts on marineand terrestrial ecosystems, and the complexinterplay between humans and their environ-ments. A detailed understanding of chronology,occupational history, and settlement size atthese sites is essential baseline information forbuilding broader archaeological and histori calecological research programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Chumash Indian community,Tawnee and Qun-Tan Shup, and Kathy Contifor their consultation during the design andimplementation of this research project. AnnHuston and Mark Senning at Channel IslandsNational Park helped facilitate our field re -search and provided logistical support. Twoanonymous reviewers, Scott Sillett, Annie Lit-tle, and the editorial staff at Western NorthAmerican Naturalist were instrumental in thereview and production of our manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

ARNOLD, J.E. 1990. An archaeological perspective on thehistoric settlement pattern on Santa Cruz Island.Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology12:112–127.

ARNOLD, J.E., EDITOR. 2001. The origins of a Pacific Coastchiefdom: the Chumash of the Channel Islands. Uni -versity of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

BEAN, L.J., AND S.B. VANE. 1978. Cults and their transfor-mations. Pages 662–672 in W.C. Sturdevant, editor,Handbook of the Indians of California. SmithsonianInstitution, Washington, DC.

CHARTKOFF, J.L., AND K.K. CHARTKOFF. 1984. The archaeo -logy of California. Stanford University Press, PaloAlto, CA.

COLE, K.L., AND G. LIU. 1994. Holocene paleoecology ofan estuary on Santa Rosa Island, California. Quater-nary Research 41:326–335.

ERLANDSON, J.M., AND K. BARTOY. 1995. Cabrillo, theChumash, and Old World diseases. Journal of Cali-fornia and Great Basin Anthropology 17:1–15.

ERLANDSON, J.M., T.C. RICK, D.J. KENNETT, AND P.L.WALKER. 2001. Dates, demography, and disease:

144 MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN NORTH AMERICAN NATURALIST [Volume 7

cultural contacts and possible evidence for OldWorld epidemics among the Island Chumash. PacificCoast Archaeological Society Quarterly 37(3):1–16.

GLASSOW, M.A., COMPILER. 2010. Channel Islands Na -tional Park archaeological overview and assessment.Report on file at Channel Islands National Park,Ventura, CA.

GRAESCH, M. 2001. Culture contact on the Channel Is -lands historic-era production and exchange systems.Pages 261–285 in J.E. Arnold, editor, The origins of aPacific Coast chiefdom: the Chumash of the ChannelIslands. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

HARRINGTON, J.P. 1913. Notes from Fernando Librado on Is -land Chumash placenames. National AnthropologicalArchives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

HEIZER, R.F. 1955. California Indian linguistic records:the mission Indian vocabularies of H.W. Henshaw.University of California Anthropological Records 15:85–202.

JAZWA, C.S., D.J. KENNETT, AND D. HANSON. 2012. LateHolocene subsistence change and marine productiv-ity on western Santa Rosa Island, Alta California.California Archaeology 4:69–98.

JOHNSON, J.R. 1982. An ethnohistoric study of the IslandChumash. Master’s thesis, University of California,Santa Barbara, CA.

______. 1993. Cruzeño Chumash social geography. Pages19–46 in M.A. Glassow, editor, Archaeology on thenorthern islands of California: studies of subsistence,economics, and social organization. Archives of Cali-fornia Prehistory No. 34, Coyote Press, Salinas, CA.

______. 1999. The Chumash sociopolitical groups on theChannel Islands. Pages 51–66 in S. McLendon andJ.R. Johnson, editors, Cultural affiliation and linealdescent of Chumash peoples in the Channel Islandsand Santa Monica Mountains. Report on file at theArchaeology and Ethnography Program, National ParkService, Washington, DC.

______. 2001. Ethnohistoric reflections of Cruzeño Chu-mash society. Pages 53–70 in J. Arnold, editor, Theorigins of a Pacific Coast chiefdom: the Chumash ofthe Channel Islands. University of Utah Press, SaltLake City, UT.

JOHNSON, J.R., T.W. STAFFORD JR., H.O. AJIE, AND D.P.MORRIS. 2002. Arlington Springs revisited. Pages541–545 in D. Browne, K. Mitchell, and H. Chaney,editors, Proceedings of the Fifth California IslandsSymposium. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural His-tory, Santa Barbara, CA.

KENNETT, D.J. 1998. Behavioral ecology and hunter-gath-erer societies of the Northern Channel Islands, Cali-fornia. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthro-pology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

______. 2005. The Island Chumash: behavioral ecology ofa maritime society. University of California Press,Berkeley, CA.

KENNETT, D.J., AND C.A. CONLEE. 2002. Emergence ofLate Holocene sociopolitical complexity on SantaRosa and San Miguel islands. Pages 147–165 in J.M.Erlandson and T.L. Jones, editors, Catalysts to com-plexity: Late Holocene societies of the CaliforniaCoast. Perspectives in California Archaeology, Vol-ume 6. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA.

KENNETT, D.J., J.R. JOHNSON, T.C. RICK, D.P. MORRIS, AND

J. CHRISTY. 2000. Historic Chumash settlement oneastern Santa Cruz Island, southern California. Jour-nal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 22:212–222.

KROEBER, A.L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of Cali -fornia. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 78.Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

MCLENDON, S., AND J.R. JOHNSON, EDITORS. 1999. Culturalaffiliation and lineal descent of Chumash peoples inthe Channel Islands and Santa Monica Moun tains.Report on file at the Archaeology and EthnographyProgram, National Park Service, Washington, DC.

ORR, P.C. 1968. Prehistory of Santa Rosa Island. Santa Bar -bara Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara, CA.

PERRY, J. 2007. Chumash ritual and sacred geography onSanta Cruz Island, California. Journal of Californiaand Great Basin Anthropology 27:103–124.

REIMER, P.J., M.G.L. BAILLIE, E. BARD, A. BAYLISS, J.W.BECK, P.G. BLACKWELL, C. BRONK RAMSEY, C.E. BUCK,G.S. BURR, R.L. EDWARDS, ET AL. 2009. IntCal09and Marine09 radiocarbon age calibration curves,0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 51:1111–1150.

RICK, T.C. 2007a. The archaeology and historical ecologyof Late Holocene San Miguel Island. Perspectives inCalifornia Archaeology, Volume 8. Cotsen Instituteof Archaeology, University of California, Los Ange-les, CA.

______. 2007b. Household and community archaeology atthe Chumash village of Niaqla, Santa Rosa Island,California. Journal of Field Archaeology 32:243–263.

______. 2009. 8000 years of human settlement and landuse in Old Ranch Canyon, Santa Rosa Island, Cali-fornia. Pages 21–31 in C.C. Damiani and D.K.Garcelon, editors, Proceedings of the Seventh Cali-fornia Islands Symposium. Institute for Wildlife Stud -ies, Arcata, CA.

______. 2011. Historic period Chumash occupation of‘Anayapax, Anacapa Island, Alta California. Califor-nia Archaeology 3:273–284.

RICK, T.C., J.M. ERLANDSON, R.L. VELLANOWETH, AND

T.J. BRAJE. 2005a. From Pleistocene mariners to com -plex hunter-gatherers: the archaeology of the Cali-fornia Channel Islands. Journal of World Prehistory19:169–228.

RICK, T.C., D.J. KENNETT, AND J.M. ERLANDSON. 2005b.Preliminary report on the archaeology and paleoe-cology of the Abalone Rocks estuary, Santa Rosa Is -land, California. Pages 55–63 in D. Garcelon and C.Schwemm, editors, Proceedings of the Sixth Califor-nia Islands Symposium. Institute for Wildlife Stud-ies, Arcata, CA.

SCHOENHERR, A.A., C.R. FELDMETH, AND M.J. EMERSON.1999. Natural history of the islands of California.University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

WAGNER, H.R. 1929. Spanish voyages to the NorthwestCoast of North America in the sixteenth century.California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

Received 7 March 2013Accepted 6 November 2013

Early online 21 July 2014

2014] ARCHAEOLOGY AT QSHIWQSHIW 145