Dark Power Rising The Philippine Power Industry Nine Years Under EPIRA (RA 9136)

-

Upload

up-diliman -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Dark Power Rising The Philippine Power Industry Nine Years Under EPIRA (RA 9136)

Dark PowerRising

The Philippine Power Industry Nine Years Under EPIRA (RA 9136)

PAID!P e o p l e A g a i n s t I m m o r a l D e b tOfficial Publication of the Freedom from Debt Coalition

VOLUME 13 NO. 1 h t tp: / /www.fdc .ph November 2009

2 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

PAID!P e o p l e A g a i n s t I m m o r a l D e b tOfficial Publication of the Freedom from Debt Coalit ion

VOLUME 13 NO. 1 h t tp: / /www.fdc .ph November 2009

Edited by:Maitet Diokno-Pascual and Wilson Fortaleza

Layout design:Alvin Gallardo

FDC Officers2008 - 2010

President:Vice Presidents:

Secretary General: Treasurer:

Assistant Treasurer:

Walden Bello

Lidy B. NacpilLoretta Ann P. RosalesFr. Juvenal A. MoraledaRebecca D.L. MalayEdwin C. ChavezMilo N. TanchulingLuzviminda A. SantosArze Glipo

No. 11 Matimpiin Street, Barangay Pinyahan, Quezon City, Philippines 1100 +63 2 924 6399 +63 2 921 [email protected]://www.fdc.ph/

Address:

Phone:Telefax:

Email:Website:

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 3

� 10 Reasons Why Electricity Bills Are High

� A Dozen Ways to Reduce Electricity Rates

� ADB privatization policy aggravates climate crisis in the Philippines

Table of ConTenTs

4

7

28

Dark Power Rising in the privatized power industry

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

TRANSCO: The Filipino’s Last L ine of Defense Against Privatization

The Undistributed Powers

Why WESM Won’t Work

33

43

ANNEXES 55

4 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

On May 12, 2008, the Joint Congressional Power Commission (JCPC) or PowerCom conducted a full blown public hearing on why electricity rates are high. The hearing was held in reaction to the 51.88 centavos per kWh spike in the price of power distributed by the Manila Electric Company (Meralco) in April 2008. It was also during that time an electrifying power struggle took place between the Lopezes and Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) President Winston Garcia.

The public hearing could have been a very good opportunity for all the stakeholders to assess the power situation in the country seven years after the passage of the Electric Power Industry Reform Act or EPIRA and to find appropriate remedies to the pestering problem of high electricity rates in the country, now one of the most expensive in the world. Unfortunately, what came into sight after the hearing was not a clear roadmap to get away from the crisis of high power rates but images of dark powers rising on the horizon – made more pronounced by a hideous power play between old and new players fighting for control of the privatized and restructured power industry. And the story goes on.

During that hearing, the Freedom from Debt Coalition submitted a

position paper entitled, “10 Reasons Why Electricity Bills are High”, presenting a broad and comprehensive analysis of the many factors that contribute to the high cost of power in the country. The paper tried to widen the perspective in making an anatomy of high electricity rates as it pointed to many issues such as privatization and the implementation of EPIRA, weak regulatory environment, corporate abuse and outright fraud, inefficiency, bad governance and corruption, among others – which the government and other players tried to hide or skew by singling out the Lopezes.

This was followed by another paper, “A Dozen Ways to Reduce Electricity Rates”, where the FDC called for a complete overhaul of the EPIRA and a decisive shift to clean and sustainable power. These two papers bolstered the Coalition’s efforts in bringing out and popularizing its critique of the EPIRA and the power privatization program and in introducing alternatives for a more democratic and sustainable power.

EPIRA nonetheless is in a complete mess, prompting PowerCom Chair Senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago to declare: “Pitong taon na ang ating Epira na gumawa ng pagbabago sa ating industriya ng kuryente, pero pagkatapos ng pitong taon, hindi pa rin nakamit yung tanging layunin na ibaba ang binabayad

sa kuryente. Ibig sabihin lahat kami ay failure. EPIRA is a failure. The Senate is a failure. The executive branch is a failure.”1

Aside from the unaddressed problem of high electricity rates, EPIRA enhances rather than destroys oligopoly2 in the industry. In fact, the much-touted wisdom of an electricity spot market was tested to its limits after the Wholesale Electricity Spot Market (WESM) succumbed to manipulations from traders who gamed the market to earn more income, as admitted one player. In a report to stockholders, the Aboitiz group declared a 124% increase in their income in 2007 due mainly from their “strategy” of trading power at the WESM during peak hours.3 This issue will be presented in another article, “Why WESM Won’t Work”.

These things, however, are not unexpected since the privatization of the National Power Corporation (NPC) merely transferred the State’s monopoly power to the private oligarchs without the intended benefits for the people. And in the case where the State merely surrendered the monopoly power of the NPC to private player(s), that power shift did not, in essence, alter the monopolistic nature of the industry and therefore the persistence of oligopoly.

This was clearly the case when the franchise to operate the national

Editorial

Dark Power risingi N T H E P R i v AT i z E D P O W E R i N D U S T R y

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 5

grid, which is a natural monopoly, was transferred to the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP), a private consortium with reported close links to Malacañang. The sale of Transco allowed the private concessionaire to operate the national grid for up to 50 years. The deal, however, was deemed by many as gravely disadvantageous to the government since it was a product of an insidious power play in the industry, with groups closely identified with the First Family securing the bid under dubious circumstances. This will be discussed fully in a separate article, “Transco: The Filipino’s last line of defense against the onslaught of privatization in the electric power industry.”

Undeniably, this right to exercise monopoly power over a captive market is the biggest privilege the industry has bestowed to old and new players. The same is true even for private distribution utilities whose monopoly control over their own respective franchise areas was left uncontested. Consequently, this enormous opportunity to gain more wealth and power from a guaranteed and risk-free business gave rise to the ongoing power plays among the oligarchs.

The unfinished battle for control of Meralco between the Lopezes and Garcia was expected to erupt into a much bigger war when stockholders gathered again in May 2009 for their annual meeting. But in a sudden turn of events, prior to the meeting, Garcia assigned the task of a power grab to Danding Cojuangco by selling the GSIS shares4 (most likely with the full blessings of Malacañang) to the San Miguel Corporation5.

To foil the power grab attempt, the Lopezes sold some 20 percent of their

share to PLDT’s Manny Pangilinan6 reportedly to serve as counterbalance to the Cojuangco-Arroyo bloc’s planned take-over.

This ugly power play in the country’s largest private distribution utility provides a picture of how the nasty

political economy of private power comes into play, of course with more attention given to the issue of corporate control and high returns rather than to providing people with the most affordable, clean and efficient energy. Economically, the fight for corporate control is mainly a battle for economic hegemony over the more than four million captive Meralco customers in Luzon who bring in over P4-B annual net income7 for the company — a very lucrative and cash-rich business, indeed. Politically, having commanding control of Meralco

gives its owners economic advantage over the other players in the industry. And from that vast economic base emerges an enormous political power especially in this country where political influence is the best guarantee for this kind of business to prosper.

In the Visayas and Mindanao region, the Aboitiz family, a familiar name in the industry has silently expanded its empire

over private distribution business. An article, “The Undistributed Powers”, provides an analysis and baseline data on the current ownership structure of the distribution sector all over the country. It also includes information on the areas covered by the electric cooperatives and updates on which

This ugly power play in the country’s largest private distribution utility provides a picture of how the nasty political economy of private power comes into play, of course with more attention given to the issue of corporate control and high returns rather than to providing people with the most affordable, clean and efficient energy.

6 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

Dark Power Rising in the Privatized Power Industry

option the ECs have preferred in their response to the implementation of EPIRA.

Furthermore, the competition among the power oligarchs is not only confined within the distribution sector. The restructured power industry under the EPIRA regime pried open the whole industry for private exploitation. The more players, the better for the industry since it was envisioned by the government that private sector participation will usher in competition which in turn would bring efficiency into the system, and “eventually” lower rates to consumers. The government has in fact provided many incentives and undue compromises in the EPIRA just to entice private sector participation. One such incentive was the National Government’s assumption of the NPC’s P200-B debts8. Another is the P1.03 tariff rate hike granted to NPC in 2004. Sovereign guarantees extended to IPPs were also honored. Congress also made sure that EPIRA allows cross-ownership9 to attract investors to venture into both the generation, transmission and distribution sector. The Asian Development Bank, World Bank and other international financial institutions (IFIs), on the other hand, provided loan facilities to the government and the private sector to finance the country’s power sector reform program.10

But only a few players came in. And more obviously, they came from the same group of oligarchs who, in one way or another, have been in the industry since the last century. In

the generation sector for instance, the main contest is also between the Lopezes and the Aboitizes. The Lopez clan, aside from having their own big IPPs, acquired many of the geothermal and other NPC plants in Luzon and Visayas. They are now also into exploration after gaining control of the Philippine National Oil Company-Energy Development Corporation (PNOC-EDC). Meanwhile, the Aboitiz group, reported to be closer to the First Family, got most of the hydro and other NPC plants in Mindanao, some in the Visayas and also some in Luzon. And more buyouts and joint ventures are expected as the rest of NPC assets, including the NPC IPPs are lined up for full privatization. A baseline data on the current ownerships of generation companies (GENCOS) is provided in another article, “From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy.”

There are other players who have ventured into or have shown interests in power. The Abayas of CEPALCO is one. Davao’s Alcantara family which owns the Alsons Consolidated Resources, Inc., is also on power generation and exploration. Some new big names to mention are SM’s Henry Sy, Metrobank’s George Ty, and now San Miguel’s Danding Cojuangco. Others in the periphery are industry names like former Energy Secretary Francisco Viray and businessman Victor Del Rosario. Certainly, the only chance for them to be able to catch up with the well-entrenched oligarchs is to follow the same route – through rent-seeking which could only be worse under the present regime.

To some extent, there are little battles that complete the picture of the ongoing power play in the entire power industry. And that is happening in the sector of electric cooperatives (ECs) — between those who campaign to remain under the National Electrification Administration (NEA) and those who prefer to register under the Cooperative Development Authority (CDA), notwithstanding moves by politicians to keep hold of or gain foothold of the ECs in their respective areas. However, debates in this area are still confined to the matter of what advantage(s) an EC can get from putting itself under the supervision of the CDA or remaining under the NEA, and not on how to transform these ECs into genuine cooperatives that contributes to local economic development.

Clearly for the past seven years, a battle line has been drawn between the government and industry oligarchs in the implementation of the power sector reform program in the country under the EPIRA. Sadly, however, it was neither a battle to bring down the power rates nor a war to provide clean and sustainable energy to the people. It was mainly a battle for control and ownership of the privatized power. This fight for control of the privatized power does not only make the ongoing power play so intense. The process has also created an assembly of dark power – a horde of new and recycled rent-seekers who are out to extract more wealth and political power by gaining monopoly control of the most lucrative business in the country today, at the chronic expense of the consumers.

endnotes1 On the Powercom hearing on Monday (12

May 2008), http://www.miriam.com.ph/labels/Renewable%20Energy%20Bill.html

2 A market condition in which sellers are so few that the actions of any one of them will materially affect price and have a measurable impact on competitors.

3 Aboitiz Power Financial Report, Annual Stockholders Meeting 2008.

4 GSiS shares to Meralco amounts to 295.50 million in 2008 representing 36.5 % of the total share.

5 San Miguel Corporation is the country’s largest food conglomerate. Lately it diversified into infrastructure, heavy industries, and now in power.

6 PDi 03/14/2009

7 Meralco Annual Report 2007

8 EPiRA, Sec. 32

9 EPiRA, Sec. 45 (a)

10 Private Sector Development in the Electric

Power Sector: A Joint OED/OEG/OEU Review

of the World Bank Group’s Assistance in the

1990s, July 21, 2003

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 7

executive summary Set forth in the Electric Power Industry Reform Act of 2001 (EPIRA) or Republic Act No. 9136 are premises of a restructured power industry and a regime of fair and free competition in the country’s power sector as means to achieve quality, reliable and affordable supply of electric power for the public.

The EPIRA was designed primarily to increase efficiency, enhance investment and encourage competition in the power sector. The privatization of the National Power Corporation’s (NPC) assets is seen as a key to dismantling the monopoly in the electricity industry and in bringing about competition in the power sector thus provides greater efficiency in the generation, transmission and distribution of electricity. But doubts remain as to power industry restructuring under the EPIRA will result to realization and attainment of those benefits.

By and large, the EPIRA’s provisions are simply too forbidding to create competition and to de-monopolize the industry. EPIRA is actually creating a market which is headed for greater concentration in the hands of multinational corporations and primarily local elites. The reforms

envisioned by the EPIRA have actually resulted to the creation of an electricity oligarchy.

The success of reforms in the power sector in fact rely on the degree of competition policies introduced in the market and less on the coverage of privatization which is in contrary with the EPIRA’s provision on NPC privatization (Patalinghug and Llanto, 2004). In particular, introducing and enforcing strong competition policies and framework might matter more than the extent of ownership. The provision in the EPIRA on the cross-ownership is weak. A total prohibition of one entity from one or more sub-sectors of the electricity industry is

more superior to putting a limitation of 30% on a company or related group to own, operate, or control of the installed generating capacity of a grid and/or 25% of the national installed generating capacity.

With the creation of the wholesale electricity spot market (WESM) model in which distribution utilities retain their exclusive service territories and buy power from competing generators, there is an urgency to expand market

power monitoring and mitigation measures considering the generation sector is characterized by relatively few dominant power generation companies. However, several studies argue that “one of the prerequisites for this model to succeed is the existence of a sufficient number of unaffiliated suppliers (Kessides, 2004)”. The EPIRA’s provision on cross-ownership breaks this competition rule.

The EPIRA’s competitive provision depends on applying non-discriminatory access to existing systems through the implementation of the WESM. This provision is inferior to a situation where both divestment and open access are demanded to

de-monopolize the industry1. The potential of market abuse is real which market power abuses will result in wealth

transfers from end-consumers to power producers. Therefore in curtailing the exercise of market power abuse and anti-competitive behavior in the electricity industry, “more effective are structural remedies than imposition of behavioral rules as provided by the EPIRA (Abrenica and Ables, 2001).”

Fundamentally, the EPIRA has no effective solution to the problems besetting the power industry. It simply

From State Monopoly to de facto Electricity OligarchyA study of the development of privatization of NPC Assets

Fundamentally, EPIRA has no effective solution to the problems besetting the power industry. It simply transfers the monopoly privileges from the State to private interests.

By Jerbert Briola

8 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

transfers the monopoly privileges from the state to private interests and thus allowing the ‘gains’ to be kept as excess profits by the privatized monopoly instead of being shared with the consumers through lower electricity rates.

IntroductionWith the passage of the EPIRA in 2001, the country has embarked on the process of power industry restructuring and deregulation. From the vertically-integrated industry, the power industry was unbundled into four sectors: generation, transmission, distribution and supply. The primary objectives of the restructuring are to increase operational efficiency and reduce dependency on government funding by increasing competition and private sector participation in power sector activity. Another major reform embodied under the EPIRA is the privatization of the NPC’s generation assets (including the Independent Power Producers contracts).

The EPIRA was to set in motion the liberalization of the power industry through the privatization of at least 70% of NPC’s assets. The Power Sector Assets and Liabilities Management Corporation (PSALM) is created to manage the sale and privatization of NPC’s assets. Besides managing the privatization of NPC’s assets, PSALM is also tasked to renegotiate the IPP contracts based on the review of the Inter-Agency Committee established for this purpose. Unless it is extended by law, PSALM has a corporate life of 25 years from the effectivity date of the EPIRA.

The main aim of the EPIRA is to enable retail consumers to choose their electricity provider. EPIRA however states that retail competition and open access2 in the electric industry can be declared only when all of the preconditions have been fulfilled. These preconditions3 are: (i) privatization of at least 70% of NPC’s generating assets, (ii) the transfer to IPP contract administrators (private entities) of the management and control of at least 70% of the total energy output of power plants under Independent Power Producers (IPPs) contracts, (iii) initial removal of cross subsidies, (iv) unbundling of transmission and distribution charges, and (v) establishment of wholesale electricity spot market. Then retail competition will begin wherein end-users with an average peak demand of 1 MW will become contestable market4.

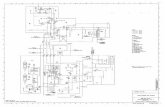

There are 31 generation assets (see Table 1) identified for privatization with an aggregate capacity of 5,914.1-MW (including decommissioned or retired power plants). The total installed capacity excluding decommissioned or retired power plants is 4,454.8-MW. These do not include the Agus and Pulangui hydroelectric power plants in Mindanao which cannot be privatized earlier than 10 years as provided by EPIRA5. The 70% privatization requirement for open access and retail competition only covers the interconnected grids of Luzon and Visayas. Hence, the Mindanao power

Table 1. List of NPC’s generation assets for privatization

Fuel type Power plantsInstalled capacity(in MW)

Location

Calaca* 600.00 Calaca, Batangas

Coal Masinloc* 600.00 Masinloc, zambales

Limay combined cycle*

620.00 Limay, Bataan

Diesel Navotas i and ii 310.00 Navotas, Metro Manila

Panay i* 36.50 Tinocuan, Dingle, iloilo

iligan i and ii 114.00 Mapalad, iligan City

Bohol* 22.00 Tagbilaran City

Diesel/Bunker Panay iii 110.00 Dingle, iloilo

Geothermal MakBan* 410.00 Laguna and Batangas

Tiwi* 275.00 Tiwi, Albay

BacMan 150.00 Albay and Sorsogon

Palinpinon* 192.50 valencia, Negros Oriental

Tongonan/Leyte* 112.50 Lim-ao, Kananga, Leyte

Hydro Magat* 360.00 Ramon, isabela

Angat 246.00 Norzagaray, Bulacan

Binga* 100.00 itogon, Benguet

Pantabangan* 100.00 Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija

Ambuklao* 75.00 Bokod, Benguet

Masiway* 12.00 Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija

Barit* 1.80 Buhi, Camarines Sur

Cawayan* 0.40 Sorsogon City, Sorsogon

Amlan* 0.80 Amlan, Negros Oriental

Agusan* 1.60 Manolo Fortich, Bukidnon

Loboc* 1.20 Loboc, Bohol

Talomo* 3.50 Tugbok, Davao City

Generation assets that have been retired

Bataan Thermal 225.00 Limay, Bataan

Manila Thermal 200.00 Ermita, Manila

Sucat Thermal 850.00 Sucat, Muntinlupa City

Cebu ii Diesel 54.00 Toledo City, Cebu

Aplaya Diesel 108.00 Jasaan, Misamis Oriental

Decommissioned power plant

General Santos Diesel

22.30 General Santos City

TOTAL CAPACITY 5,914.10

Source: Power Sector Assets and Liabilities Management (PSALM)Note: *privatized

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 9

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

plants such as Agusan and Talomo hydroelectric power facilities are not included.

The 70% privatization target is seen as a crucial condition needed for the WESM to operate. The WESM is a main component of the reforms in the power industry to encourage competition in the sector and bring down the costs of electricity. It is a marketplace for the trading of electricity and a venue for generators/sellers to offer their outputs and specify their bid prices to buyers in 24 one-hour trading periods only. It also serves as a mechanism to encourage investors to participate in the generation sector and attract buyers of the NPC’s assets.

But it is widely seen that the delay in the privatization of the NPC’s assets has set back on the timetable for the opening of WESM. According to the EPIRA, WESM’s commercial operation would be one year after the actual commencement date of Open Access and Retail Competition (OARC) in the Luzon Grid. The WESM began commercial operations on June 23, 2006 in Luzon and is already in its 34th month of commercial operations. The Trial Operation Program (TOP) of WESM in Visayas is now being implemented. The first target of OARC was 2004 as provided by the EPIRA6.

With the sale of what are considered two big-ticket power plants in 2007, the 600-MW Calaca coal-fired power plant and 600-MW Masinloc coal-fired power plant are widely touted as the test case for the government’s privatization blueprint. Masinloc was sold for $930M to the Masinloc Power Partners Co. Ltd.7 While Calaca fetched $786.53M from the consortium of Calaca Holdco Inc. now Emerald Energy Consortium. The consortium is wholly owned by Suez-Tractebel8 through its wholly-owned subsidiary Belgelectric Finance B.V.

Before the 600-MW Masinloc power plant was sold by the government, it had been mired in controversy in December 2004. The Calaca and

Masinloc power plants were sold in 2007 but not without a series of failed biddings mainly because of the absence of transition supply contracts9 assigned to the sale of these power plants. Thus, the government has attached a 287-MW power supply contract to Calaca and another 265-MW for Masinloc when the said two power plants were finally sold. When sold last October 2007, a transition supply contract from Napocor was attached to the Calaca power facility to make it more palatable to the bidders.

However in January 2009, the winning bidder of the 600-MW Calaca power plant10, the Suez-Tractebel decided to back out of the deal citing the deterioration of the power plant since its bidding date on October 16, 2007. It will be noted that one of the conditions for the turnover of the power plant to the winning bidder is that it should be delivered “as is, where is” to the new owner, or in the same condition as it was during the bidding date.

The problem resulted from the unsuccessful sale of the Calaca power facility will not only affect the revenue flow for the PSALM but will also directly affect the implementation of OARC as provided under the EPIRA. The sale of 600-MW Calaca power facility was supposed to achieve the 70 percent privatization level of the NPC’s assets which is required before an open access is implemented. Under the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) guidelines, the interim open access (IOA) will not start unless the Calaca power facility sale has been consummated.

Then in July of 2009, the Calaca power facility was sold to DMCI Holdings Inc. at $361.71M bested the only other bidder, Banpu Power Ltd. of Thailand, which submitted a $280-million bid. The Calaca facility has been allocated a 287-MW power supply contract, or about 48 percent of the plant’s rated capacity. MERALCO will take 169 MW of the contracted energy.

Between 2001 and 2009 (table 2), twenty one power plants were sold. The Lopez and Aboitiz groups acquired the ownership of twelve of these power generation facilities, while nine power plants (Barit, Cawayan, Loboc, Masinloc, Calaca, Panay-Bohol, Amlan and Limay) have been sold to other private entities (including one electric cooperative). The 100-MW Pantabangan and 12-MW Masiway power plants were sold as one package11 in September 2006 to the Lopez-owned First Gen Corporation. In December 2006, Aboitiz Power Corporation acquired the 360-MW Magat power plant. The 75-MW Ambuklao and 100-MW Binga generation facilities were sold as one package fetched $325 M from SN Aboitiz Power Hydro Inc. (SNAP Hydro) in 2007.

In 2008, the 747.53-MW Tiwi-MakBan geothermal complex considered as big-ticket item on the auction block was the first geothermal power facility sold by the government. PSALM attached a total of 475-MW in power supply contracts to the sale, thus providing the new owner AP Renewables Inc. with a ready market sale for its electricity output. AP Renewables Inc. bested that of Lopez-owned First Luzon Geothermal Energy Corp. AP Renewables is a domestic corporation wholly owned by the Aboitiz Power Corporation (APC). APC is 75.59% owned by Aboitiz Equity Ventures.

On September 9, 2009, Green Core Geothermal Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Energy Development Corporation (EDC) of the Lopez group bagged the 192.5-megawatt Palinpinon and 112.5-MW Tongonan geothermal power facilities package for $220 million. It edged out the $200 million tender posted by Therma Power Visayas of the Aboitiz Group, the only other bidder in the asset sale.

Taking into account the momentum for the sale of NPC’s assets, the privatization of the power industry is moving at a slow pace. Nearly eight years after the passage of the EPIRA, the preconditions for open access and

10 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

Table 2. List of privatized power plants as of September 2009

Power Plant Year privatized Capacity (in MW) Grid Winning Bidder Price

(US$ M)1.Talomo Hydroelectric March 25, 2004 3.50 Mindanao Hydro Electric Development Corp. 1.37

2. Agusan Hydroelectric June 4, 2004 1.60 Mindanao First Generation Holdings 1.53

3. Barit Hydroelectric June 25, 2004 1.80 Luzon People’s Energy Services inc. 0.48

4. Cawayan Hydroelectric Sept. 30, 2004 0.40 Luzon Sorsogon ii Electric Cooperative, inc. 0.41

5. Loboc Hydroelectric Nov. 10, 2004 1.20 visayas Sta. Clara international Corp. 1.42

6-7. Pantabangan-Masiway Hydro Sept. 7, 2006 112.00 Luzon First Gen Hydropower Corp. 129.00

8. Magat Hydroelectric Dec. 14, 2006 360.00 Luzon SN Aboitiz Power Corporation 530.00

9. Masinloc Coal-Fired Thermal July 26, 2007 600.00 Luzon Masinloc Power Partners Co. Ltd. 930.00

10-11. Ambuklao-Binga Hydroelectric Nov. 28, 2007 175.00 Luzon SN Aboitiz Power Hydro inc. 325.00

12-13. Tiwi-Makban July 30, 2008 747.53 Luzon AP Renewables inc. 446.89

14.-15. Panay and Bohol Diesel Nov. 12, 2008 168.50 visayas SPC Power Corporation 5.86

16. Amlan Hydroelectric Dec. 10, 2008 0.80 visayas iCS Renewables inc. 0.23

17. Calaca Coal-Fired Thermal July 8, 2009 600.00 Luzon DMCi Holdings inc. 361.71

18. Power Barge 118 July 31, 2009 100.00 Mindanao Therma Marine inc. 14.00

19. Power Barge 117 July 31, 2009 100.00 Mindanao Therma Marine inc. 16.00

20. Limay Combined-Cycle Aug. 26, 2009 620.00 Luzon San Miguel Energy Corporation 13.50

21. Palinpinon-Tongonan Geothermal Sept. 2, 2009 305.00 visayas Green Core Geothermal inc. 220.00

TOTAL 3,897.33 $2,997.40 B

Source: PSALM

retail competition have not yet been fulfilled. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) noted the pace of power sector reforms in the Philippines is similar to that of other countries. The ADB in its study said “(w)orldwide the experience is that the risks of sector reforms are usually underestimated and that implementation takes longer than anticipated.”12 A former NPC President suggested that this is the prevailing case because the government has been following a flawed strategy of privatizing before restructuring.13 The sale of NPC’s assets14 will help bring down the debt level, but every year of delay in privatization according to the ADB study means opportunity costs running close to $1 billion. These are in terms of foregone interest, a drop in asset values due to wear and tear, and continuing losses from the operation of these assets.

The twenty one power plants that have already been sold and privatized translates to 3,897.33-MW generating capacity or equivalent to about 87.48% of the total 4,454.8-MW installed generating capacity scheduled for

privatization in the Luzon and Visayas grids. The total revenues earned from the sale of these generation assets have already reached $2,997.4B (P145,733.58B at peso-dollar rate P48.62=$1).

However, owing to the slow pace of privatization, PSALM revised its target for the sale of the remaining NPC’s generation assets. PSALM’s indicative privatization plan for the NPC’s generation assets in Luzon and Visayas shows a 50% target for 2007. Based on the stage of the privatization of NPC’s power plants, the government hopes to achieve 70% privatization level by 2008 while the complete privatization is by end of 2009.

PSALM reported that the delay in the privatization is attributed to a confluence of factors such as investors’ interest and plant-specific concerns including operations and maintenance agreements for multipurpose hydro power facilities, fuel supply agreements and land-related issues. The absence of supply contract between power producers and its prospective market

i.e. distribution utilities, electric cooperatives etc. poses a major reason for the delay.

Another cause of delay is the waiting period of PSALM for the approval of NPC’s creditors in the sale of power plants before the completion of the sale and transfer of NPC’s assets to winning bidders. The transfer of management control of at least 70% of the total energy output of power plants under NPC-IPP contracts also had its share in the slow process of privatization.

supply and demand situationThe country’s electric grid with about 15,937.1-MW is divided into three: Luzon grid accounts for about 76.3% of the total installed capacity, Visayas represents about 11.4% and Mindanao accounts for about 12.1% (table 3). The generation sector consists of the following: (i) NPC owned and operated generation facilities; (ii) NPC-owned plants, which consist of plants operated by Independent Power Producers (IPPs), as well as IPP-owned

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 11

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

and operated plants, all of which supply electricity to NPC; and (iii) IPP-owned and operated plants that supply electricity to customers other than NPC.

As of 2008, the country has 107 power plants (operational) i.e. NPC owned and operated, NPC-IPPs and non-NPC with a total installed generating capacity of 15,937-MW.

Based on DoE data in 2008, of the 15,937.1-MW total installed generating capacity, 13,205-MW or 83% is said to be dependable capacity. Although no additional power plant went online in 2007, the increase was due to the reconciliation of data between DoE, NPC and PSALM. Coal-fired power plants have the largest share in terms of installed capacity, contributing 4,213-MW or 26.44% of the mix. Majority of these coal plants are located in Luzon. Oil-based power plants accounted for 3,616-MW or 22.69% of the total capacity. Hydroelectric power plants, which is the main source of electricity in Mindanao accounted for

3,289-MW or 20.64%. Natural gas fired power plants in Luzon grid amounted to 2,834-MW or 17.78%; geothermal power plants which are mostly located in Visayas grid accounted for 1,958-MW or 12.29% to the total installed capacity. Other renewable energy such as wind and solar accounted for only 0.16% of the capacity generation mix15.

Power generation is undertaken by the NPC, by IPPs and by privately-owned generation facilities. Some utilities and electric cooperatives also have their own generating units, but the energy output of these are generally small. Gross power generation in 2008 (table 5) reached 60,821 gigawatt-hours (GWh), 2.03 percent higher than 59,612 GWh in 2007. Natural gas fired power plants remain the dominant source of fuel for power generation with 19,576 GWh or 32.19% of the total country’s generation. This marks the fourth consecutive year in which natural gas-fired had the biggest share on gross generation since replacing coal-fired in 2005 (DOE Power Statistics 2008).

Table 3. Indicative Privatization Targets for Generating Assets, 2008-2009

Year Grid Plants Fuel typeRated

capacity (MW)

2008 Luzon Tiwi* Geothermal 289.00

Luzon Makban * Geothermal 458.53

Mindanao iligan i & ii Diesel/ Bunker

114.00

visayas Panay* Diesel 146.50

visayas Bohol* Diesel 22.00

visayas Amlan* Hydro 0.80

Sub-Total of Operating Capacities/Year (excluding Iligan I & II)

916.83

Sub-Total of Operating Capacities/Year 1,030.83

2009 Luzon Angat Hydro 246.00

Luzon Navotas i & ii Diesel 310.00

visayas Palinpinon* Geothermal 192.50

visayas Tongonan* Geothermal 112.50

Luzon Bacman Geothermal 150.00

Sub-Total of Operating Capacities/Year 1,011.00

T O T A L (without Iligan I and II) 1,927.83

T O T A L 2,041.83

Source: PSALM. *sold as of September 2009

Table 4.Power plants Installed capacity (in MW)

Luzon 55.00 12,172.02

visayas 31.00 1,831.60

Mindanao 21.00 1,933.40

National 107.00 15,937.10

Source: Department of Energy, 2008

Table 5.

2008 Gross Power Generation by Utility (in GWh)

Generation in GWh % share

NPC 12,743.00 21.00

NPC-SPUG 448.00 1.00

NPC-iPP 27,972.00 46.00

Non-NPC 19,658.00 32.00

Total generation 60,821.00 100.00

2007 Gross Power Generation by Utility (in GWh)

Generation MWh % share

NPC 15,151,017.00 25.00

NPC-SPUG 437,372.00 1.00

NPC-iPP 26,155,930.00 44.00

MERALCO iPP 14,413,361.00 24.00

Non-NPC 3,454,109.00 6.00

Total generation 59,611,788.00 100.00

2006 Gross Power Generation by Utility (in GWh)

Generation MWh % share

NPC 17,299,198.00 30.50

NPC-iPP 23,172,666.00 40.80

MERALCO iPP 14,308,642.00 25.20

RECs/other iPPs 2,003,624.00 3.50

Total generation 56,784,130.00 100.00

2005 Gross Power Generation by Utility (in GWh)

Generation MWh % share

NPC 15,780,230.00 27.90

NPC-iPP 24,716,762.00 43.70

MERALCO iPP 13,985,901.00 24.70

RECs/other iPPs 2,084,846.00 3.70

Total generation 56,567,740.00 100.00

Source: Department of Energy

12 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

This was followed by coal at 28.24%. Meanwhile generation from hydro electric power plants fell by 13.84%, from 9,939 GWh in 2006 to 8,563 GWh in 2007. Likewise, generation from geothermal power plants decreased by 2.39% from 10,465 GWh in 2006 to 10,215 GWh in 2007 due to outages experienced by Macban, Bacman and Tiwi geothermal plants in Luzon.16

The share of NPC to the total generation by utilities fell by 9.77 % contributing 15,588 GWh or 26.15% of the mix in 2007. This was due to the transfer of Pantabangan-Masiway hydropower plant complex to First Gen on November 18, 2006 and Magat hydropower plant to SN Aboitiz on April 26, 2007. Contributions from NPC-IPPs accounted for 26,156 GWh or 43.88% of the total electricity generation while from non-NPC power plants contributed 17,867 GWh or 29.97% of the mix. Non-NPC power plants are those of Meralco IPPs and privately-owned generation facilities. Of the 17,867 GWh, the Meralco IPPs have a 24 % share (14,413,361 GWh) of the total generation in 2007. DoE data shows the share of IPPs of Meralco in total power generation grew from 2% in 1997 to 24% in 2007. In contrast, the share of NPC (including its IPPs) fell from 97 percent to about 70 percent.

Out of the total installed capacity of 15,937.1-MW (table 4), the NPC owned and operated generation facilities accounted for 22% or 3,554.48-MW (includes Tiwi-MakBan geothermal power complex). The large portion of installed capacity is under the operation of NPC-IPPs accounted for 47% or equivalent to 7,547.21-MW. And the non-NPC power plants accounted for 30% or 4,837.02-MW.17

Based on DoE data in 2008, in the sale of Tiwi-Makban hydro facilities, NPC’s market share of its remaining generating assets was reduced to 2.8 percent in the Luzon Grid while for the national grid its share is 12.4 percent. Aboitiz Power Corporation market share in the Luzon grid grew to 9.0 percent with its acquisition of privatized power plants to include Magat hydro, Ambuklao-Binga hydro complex and Tiwi-Makban geothermal facilities. NPC-IPPs maintain the bulk of the share with 69.6 percent in the national grid.

Luzon accounted for about 74% of all energy demand, which is 76% of the national installed generating capacity. Visayas, on the other hand, shared for roughly 12% of demand, boasted of only 11.4% of total installed generating capacity. Mindanao has about 14% of all energy demand that translated to 12% of the country’s total installed capacity.

The generation capacities today far exceed consumption levels. The country consumed 59,612 GWh18 in 2007. The demand for electricity at peak levels is only in the range of 8,000-MW to 9,000-MW (table 5). The bulk of installed capacity is in Luzon, 12,172.02-MW, where the peak demand reached 6,643-MW in 2007. Over the past five years, Visayas has watched peak demand increase from

Table 8. List of NPC owned and operated power plant in Luzon as of September 2009

Power plant Capacity (in MW) LocationNavotas i and ii diesel 133.38 Navotas, Metro Manila

Limay combined-cycle* 620.00 Limay, Bataan

MakBan geothermal* 442.80 Calauan, Laguna

BacMan geothermal 150.00 Bacon, Sorsogon

Tiwi geothermal* 275.69 Tiwi, Albay

Angat hydroelectric 246.00 Norzagaray, Bulacan

Total 529.38

Source: Department of Energy note: *privatized

Table 9. List of NPC-IPP in Luzon as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Pagbilao i and ii coal-fired* 728.00 Pagbilao, Quezon

Sual i and ii coal-fired* 1,294.00 Sual, Pangasinan

San Antonio natural gas 3.00 Echague, isabela

Subic diesel 116.00 Subic, zambales

Bauang diesel 235.20 Bauang, La Union

ilijan natural gas 1,271.00 Batangas City

Hopewell gas turbine 310.00 Navotas, Metro Manila

San Roque multi-purpose 345.00 San Manuel, Pangasinan

Ampohaw-Bineng hydro 18.35.00 Sablan, Benguet

Caliraya-Botocan-Kalayaan (CBK) 755.50 Kalayaan, Laguna

Bakun hydroelectric 70.00 Alilem, ilocos Sur

Casecnan hydroelectric 165.00 Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija

Northern Mini Hydro Corp. 12.40 Bakun, Benguet

Malaya Thermal 650.00 Pililia, Rizal

TOTAL 5,973.45

Source: Department of Energy *privatized

Table 6. Installed capacity as of April 2008 (in MW)NPC owned

and operated NPC-IPP* Non-NPC TOTAL

Luzon 1,867.18 5,973.45 4,330.64 12,172.02

visayas 570.50 861.28 402.24 1,831.60

Mindanao 1,116.80 712.48 104.14 1,933.40

National 3,554.48 7,547.21 4,837.02 15,937.10

Source: Department of Energy *PNOC-EDC power plants are included in NPC-IPP power plants

Table 7. Peak demand (in MW)Grid 2007 2006 % change

Luzon 6,643.00 6,466.00 2.74

visayas 1,102.00 1,066.00 3.38

Mindanao 1,241.00 1,228.00 1.06

TOTAL 8,986.00 8,760.00 2.58

Source: Department of Energy

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 13

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

903-MW in 2002 to 1,102-MW in 2007, while installed capacity reaches 1,831.6-MW. That same year, peak demand was at 1,241-MW in Mindanao compared to the installed capacity of 1,933.4-MW.

In Luzon, there are 55 power generation facilities. Six are NPC owned and operated generation facilities19. These power plants have a total installed generating capacity of 1,867.18-MW while there are 13 NPC-IPPs with a combined installed capacity of 5,973.45-MW. 36 non-NPC power plants have a total generating capacity of 4,330.64-MW.

In Visayas, there are 31 power generation facilities of which nine are NPC owned and operated (table 9) with a total installed generating capacity of 570.5-MW, 5 are NPC-IPPs (table 10) with a combined installed generating capacity of 861.28-MW, and 17 non-NPC power plants (table 11) have a total installed generating capacity of 402.24-MW.

In Mindanao, there are 21 power generation facilities the biggest of which is the 727-MW Agus hydroelectric power complex. While 4 power plants are NPC owned and operated (table 12) with a total installed generating capacity of 1,116.8-MW, 6 are NPC-IPPs (table 13) with a total installed capacity of 712.48-MW. The 11 non-NPC power generation facilities have a combined installed capacity of 104.14-MW (table 14).

from government monopoly to private monopolyIn economics, privatization turns over the control of an enterprise from government to the private sector. If the enterprise is run inefficiently by government (which is mostly the case) then theoretically privatization is likely to result in greater production efficiency and lower prices

Table 10. List of non-NPC power plant in Luzon as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Calaca coal-fired* 600.00 Calaca, Batangas

Masinloc coal-fired 600.00 Masinloc, zambales

Quezon Power 511.00 Mabalacat, Pampanga

Asia Pacific Energy Corp. 50.00 Bauang, La Union

Duracom iii and iv 109.00 Navotas, Metro Manila

Angeles diesel 30.00 Angeles City

Tarlac Electric 18.90 Capas, Tarlac

Trans Asia Power 52.00 La Union

Magellan Cogen** 63.00 Rosario, Cavite

Sta. Rita natural gas 1,060.00 Sta. Rita, Batangas

San Lorenzo natural gas 500.00 Sta. Rita, Batangas

MakBan Ormat 15.73 Bay, Laguna

Manito 1.50 Albay

Magat hydroelectric 360.00 Ramon, isabela

Pantabangan-Masiway 112.00 Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija

Ambuklao-Binga 175.00 Bokod, Benguet

Cawayan hydroelectric 0.40 Guinlajon, Sorsogon

Barit hydroelectric 1.80 Buhi, Camarines Sur

NiA Baligatan 6.00 Benguet

Aqua Grande 4.50 Pagudpod, ilocos Norte

Amburayan 0.20 Sudipen, La Union

Dawara 0.53 Suyo, ilocos Sur

Bachelor 0.75 Natividad, Pangasinan

Sal-angan 0.50 itogon, Benguet

Club John Hay 0.50 Baguio City

Magat A and B 2.52 Ramon, isabela

Tumauini 0.25 Tumauini, isabela

Dulangan 1.60 Oriental Mindoro

Balugbog 0.65 Nagcarlan, Laguna

Palapaquin 0.40 San Pablo City, Laguna

San Juan river 0.15 Kalayaan, Laguna

yabo 0.20 Pili, Camarines Norte

NorthWind Project 25.00 Bangui, ilocos Norte

TOTAL 4,330.64

Source: Department of Energy *privatized last July 28, 2009 **Magellan Cogen: for confirmation on the operation of the power plant

Table 11. List of NPC owned and operated power plant in Visayas as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Power Barge (PB) 103 32.00 Estancia, iloilo

Panay diesel power plant i 36.50 Dingle, iloilo

PB 101 32.00 iloilo

PB 102 32.00 Obrero, iloilo

Bohol diesel power plant* 22.00 Tagbilaran City

Panay diesel power plant iii (Pinamucan)*

110.20 Dingle, iloilo

Palinpinon geothermal* 192.50 valencia, Negros Oriental

Leyte geothermal* 112.50 Tongonan, Leyte

Amlan geothermal* 0.80 Amlan, Negros Oriental

TOTAL 570.50

Source: Department of Energy *privatized

Table 12. List of NPC-IPP in Visayas as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Cebu thermal i and ii 109.30 Naga, Cebu

Cebu diesel 37.80 Toledo City, Cebu

Cebu Land-Based Gas Turbine i and ii

55.00 Cebu City

Tongonan geothermal ii and iii (Leyte A)

610.18 Tongonan, Leyte

Northern Negros geothermal 49.00 Bago City

TOTAL 861.28

Source: Department of Energy

14 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

to consumers. The government enterprise activity will first have to be de-monopolized and greater private sector participation is encouraged. Otherwise, the monopoly privileges will simply be transferred to the private interest, and any resulting efficiency gains will be kept as excess profits by the privatized monopoly instead of being shared with the consumers through lower prices.

Steve Thomas, an academic who has closely followed the electricity reforms throughout the world, observes the tendency towards monopolization as a result of these reforms. “After initially unbundling electricity monopolies into several firms, many countries saw those companies vertically and horizontally reintegrated through mergers and acquisitions. In many cases, therefore, power liberalization resulted in the creation of electricity oligarchies. These tend to be dominated by powerful multinational and transnational corporations.”20

With the passage of the EPIRA, the power industry began its own process of power industry restructuring and deregulation. This restructuring characterizes greater

reliance on competition and market forces which are expected to increase efficiency and enhance investment in the power industry. The EPIRA has specific provisions dealing with monopoly such as policies on cross-ownership, open access and wholesale electricity spot market but none on mergers. The EPIRA’s aims of retail competition and open access in the power industry are unlikely to be realized since the provisions of the law on anti-competitive behavior. Suffice it to say that it will make the system from once-government monopoly to private monopoly. It also opened up the real possibility of excesses and market abuses by few dominant players thus further exacerbating the burden on consumers due to oppressive power rates.

It is important to place strict limits on market share and cross-ownership in the power industry to prevent market power abuse. But the risk of market power abuse in the EPIRA is inherent because the cross-ownership provision in the law is insufficient and weak. In fact, it does not forbid a company or related group to own, operate, or control 30% of the installed generating capacity of a grid and/or 25% share of the national grid. In 2008, the ERC has determined the total installed generating capacity in each grid and has set the market share limitations (see table 18).

The leading private sector participant in the generation industry is the Lopez-owned First Gen Power Corporation and its affiliates with 19.8 percent share in the Luzon grid and 15 percent of the national grid. Thus, outright disallowance of cross-ownership is deemed superior to a stipulation on open access because the cross-ownership provision of the EPIRA exposes the industry to more competitive risks and “opens the possibility for a distribution company to enter into supply contracts with its generation subsidiaries and create hidden profits for the conglomerate (Patalinghug and Llanto, 2004).”

The lessons from California’s power sector restructuring experience can be cited to prove the potential for market power abuse in a deregulated power sector. It was

Table 15. List of NPC-IPP in Mindanao as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Southern Philippines Power Corporation

59.00 Alabel, Sarangani

Power Barge 117* 100.00 Nasipit, Agusan del Sur

Power Barge 118* 100.00 Maco, Davao del Norte

Western Mindanao Power Corporation

113.00 Sangali, zamboanga del Norte

Mt. Apo geothermal i and ii 108.48 Kidapawan, South Cotabato

Mindanao coal-fired thermal 232.00 villanueva, Misamis Oriental

TOTAL 712.48

Source: Department of Energy *privatized

Table 14. List of NPC owned and operated power plant in Mindanao as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Power Barge (PB) 104 32.00 Brgy. ilang, Davao City

iligan diesel i and ii 102.70 Dalipuga, iligan City

Agus hydroelectric complex 727.10 Lanao del Sur/del Norte

Pulangi hydroelectric 255.00 Maramag, Bukidnon

TOTAL 1,116.80

Source: Department of Energy

Table 13. List of non-NPC power plant in Visayas as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Toledo Power Corporation (Sangi station)

88.80 Toledo City, Cebu

Panay Power Corporation 74.88 La Paz, iloilo

Panay Electric Company 19.85 iloilo City

Toledo Power (Carmen station) 45.8 Toledo City, Cebu

Cebu Private Power 70.00 Cebu City

Janopol hydroelectric 5.00 Bohol

Loboc hydro 1.20 Loboc, Bohol

Mantayupan 0.50 Barili, Cebu

Basak 0.50 Badian, Cebu

Matutinao 0.72 Badian, Cebu

Ton-ok 1.08 Calbayog City, Samar

Henabian 0.81 St. Bernard, Southern Leyte

TOTAL 402.24

Source: Department of Energy

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 15

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

demonstrated most vividly by the California electricity crisis at the onset of this century. The California crisis revealed that competition and antitrust regulation in place at that time were not sufficient to impede or prevent the exercise of market power abuse by a number of generation companies.

From the lessons of California’s power sector restructuring, market power abuse has been identified and is possible to occur therefore it is necessary that mitigation measures i.e. strong regulation and enforcement policies are in place to prevent these power generation firms from causing harm to consumers. Given the constraints inherent in the market, the market power abuse of private companies is real possibility to happen.

The generation sector has a number of large companies and distribution utilities such as Lopez-owned generation company First Gen has Meralco and Panay Electric Company (PECO) as its distribution firms while Aboitiz-owned distribution utilities are Visayan Electric Company (VECO), Davao and Cotabato Light and Power Companies, have ever been thriving and more profitable under the transition to a privatized regime. These companies, either deliberately or unwittingly, have the ability to price their output at higher than competitive prices. Looking at the WESM indicators of market concentration you will get the picture that the Lopez-controlled First Gen, and the Aboitiz-owned power generation and distribution utilities dominate the power industry.

Market power abuses result in wealth transfers from consumers to producers simply because the law allows

it. A strong monitoring and prevention of market power abuse is an important task of the power sector regulator—that the ERC can and will live up to this task is in serious doubt. The competitive provision in the EPIRA relies on implementing non-discriminatory access to existing systems. This provision is inferior to a situation where both divestment and open access are demanded to de-monopolize the industry. Open access provision relies on effective monitoring and enforcement of regulatory rules which is unlikely given the performance of government regulatory agencies like the ERC which has a dismal track record and also doubt remains as to their “independence”. Learning from the experience of California’s power restructuring and other countries, it is more effective to impose structural remedies in curtailing the exercise of market power abuse and anti-competitive behavior in the industry than just impose a set of behavioral rules.21

Table 16. List of non-NPC power plant in Mindanao as of April 2008

Power plant Capacity (in MW) Location

Mindanao Energy Systems 18.90 Brgy. Tablon, Cagayan de Oro City

Cotabato Light and Power Company 10.00 Cotabato

Davao Light and Power Co. 58.69 Davao City

Agusan mini-hydro 1.60 Manolo Fortich, Bukidnon

Bubunawan 7.00 Baungon, Bukidnon

Talomo 3.70 Brgy. Mintal, Talomo, Davao City

Balactasan 0.27 Lamitan, Basilan

Kumalarang 0.68 Lantawan, Basilan

Mountain view 0.80 valencia, Bukidnon

Matling 1.50 Malabang, Lanao del Sur

Solar Photovoltaic 1.00 Brgy. indahag, Cagayan de Oro City

TOTAL 104.14

Source: Department of Energy

Table 17.

GridInstalled

generating capacity (kW)

% Market share limitation

Installed generating

capacity (kW)Luzon 10,060,904.00 30.00% 3,018,271.20

visayas 1,637,270.40 30.00% 491,181.10

Mindanao 1,703,348.00 30.00% 511,004.40

National 13,401,522.40 25.00% 3,350,380.60

Source: PSALM

Table 18. Installed Capacity and Share Per Grid

Luzon Visayas Mindanao PhilippinesNPC* 282.32 438.32 440.32 1,661.44

NPC-iPP** 6,217.57 785.46 668.48 7,671.51

TOTAL NPC and NPC-iPP 6,499.89 1,223.78 1,609.28 9,332.94

First Gen 1,608.50 69.00 1.60 1,679.10

Aboitiz 908.59 119.60 57.77 1,085.96

Other iPPs 1,043.92 224.89 34.70 1,303.51

Sub-total iPPs 3.561.02 413.49 94.07 4,068.58

TOTAL 10,060.90 1,637.27 1,703.35 13,401.52

Share in percentage per grid

NPC 2.81 % 26.77% 55.23% 12.40%

NPC-iPP 61.80% 47.97% 39.25% 57.24%

TOTAL NPC and NPC-iPP 64.61% 74.75% 94.48% 69.64%

First Gen 15.99% 4.21% 0.09% 12.53%

Aboitiz 9.03% 7.30% 3.39% 8.10%

Other iPPs 10.38% 13.74% 2.04% 9.73%

Sub-total iPPs 35.39% 25.25% 5.52% 30.36%

TOTAL 100% 100% 100% 100%

Source: 13th EPIRA Implementation Status Report (May to October 2008)

16 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

In relation to this, Diokno-Pascual emphasized the Asian Development Bank (ADB) findings from a fact-finding mission it sent to the ERC, in preparation for a technical assistance grant to the ERC. The main findings of this mission are as follows:22

z “employees are unable to undertake thorough analysis due to lack of knowledge and skills in regulation and rate setting methodologies”

z “the document tracking and filing system is poor as business processes are not clearly defined”

z “staff are inexperienced in handling consumer complaints and dispute resolution.”

The Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) argued the provision in the EPIRA on privatization of NPC’s assets that has overlooked the probability that the “success of reforms may hinge more on the degree of competition introduced in the market and less on the extent of privatization”. PIDS further said Caves and Christensen (1980) found no evidence of inferior performance by the government-owned railroad compared to that of the privately-owned railroad. Estache and Rossi (2002) showed that the efficiency is not significantly different in private water companies than in public ones. And Kwoka (1996) “found that competitive pressures are more important than ownership in explaining electric utilities’ performance in the US.” In the U.S. where state-owned and privately-owned electric companies competed, there was little difference in performance. Similarly, in the U.S., where electricity supply was provided by the state-owned monopoly, performance was lower than in states where privately-owned monopoly supplied electricity.23 As if the Philippines had not had enough painful lessons from past privatization projects, private ownership does not automatically bring about a competitive situation that creates more efficiency and higher consumer welfare.

As of April 2008, the continuing sales of NPC’s assets had increased private sector share (NPC-IPPs and non-NPC power generation facilities) in the generation sector with 90.5% combined share in Luzon total installed capacity and 82.2 % share in the national grid. But even as the EPIRA’s envisioned de-monopolization of the power industry has come to fruition, the restructuring of the power industry is actually creating a market that is heading for greater concentration among a handful of private players in the industry.

snapshot of power players in the industrySince the passage of EPIRA, the share of Lopez-owned generation companies and Meralco’s IPPs in total power generation has increased significantly. This is largely due to the Lopez-owned natural gas plants which began commercial operations around the same time EPIRA was passed. In 2007, First Gen bought out the shares of its Dutch

partner, Spalmare Holding BV, in the Philippine National Oil Company-Energy Development Corporation (PNOC-EDC). First Gen now owns a 60% stake in PNOC-EDC. First Gen and its subsidiaries owned or have controlling interests in 13 generation facilities nationwide with (see tables 19, 20 and 21) a total installed capacity of 3,515.66 MW. This translates to about 23 percent share of the national grid.

First Generation and its affiliates accounted for 13% of the total generation facilities in Luzon with a total installed generating capacity of 2,421.6 MW. It translates to 20 %

share over the total Luzon installed capacity of 12,172.02 MW or 15% share in the country’s total grid.

In Visayas, First Gen and its subsidiaries have shares and investments in three generation facilities with a combined installed generating capacity of 984.03 MW. This account for 53% share of Visayas grid.

While in Mindanao, First Gen has two generation facilities with total installed generating capacity of 110 MW or 5.6 % share of Mindanao grid.

Meralco is the most dominant distribution utility in the Philippines. It has a franchise area of 9,337 sq. km. serving 23 cities and 88 municipalities including Metro Manila, the entire provinces of Bulacan, Rizal and

Table 19.Luzon Location in MW

1.Quezon Private Power Mauban, Quezon 511.00

2.Bauang Diesel Bauang, La Union 235.60

3.San Antonio natural gas Echague, isabela 3.00

4. Sta. Rita natural gas Sta. Rita, Batangas 1,060.00

5. San Lorenzo natural gas Sta. Rita, Batangas 500.00

6-7. Pantabangan-Masiway hydro complex

Pantabangan,Nueva Ecija 112.00

TOTAL 2,421.60

Table 20.Visayas Location in MW

1. Panay Electric Company iloilo City 19.85

2. Tongonan Geothermal Tongonan, Leyte 610.18

3. Northern Negros Geothermal Bago City, Negros Occidental 49.00

4. Palinpinon Negros Oriental 305.00

TOTAL 984.03

Table 21.Mindanao Location in MW

1. Mt. Apo Geothermal plant i and ii

Kidapawan, North CotabatoPower

108.40

2. Agusan Hydroelectric Manolo Fortich, Bukidnon 1.60

TOTAL 110.00

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 17

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

Cavite; parts of the provinces of Laguna, Quezon and Batangas; and 17 barangays in Pampanga. The franchise area covers around 19 million people, almost a quarter of the entire Philippine population of 80 M which accounts for approximately 50% of the gross domestic product (GDP), 31% from Metro Manila alone. MERALCO’s total energy sales grew 1.1% from 24,806.2M kWh in 2005 to 25,077.5M kWh in 2006. The number of customers likewise rose by 1.6% from 4,317,064 in 2005 to 4,388,086 in 2006, 88% of which are residential customers.24

Meralco’s supply contracts with its IPPs e.g. Lopez-owned Sta. Rita and San Lorenzo power plants are singled out as classic cases of the disadvantageous nature of the cross-ownership provision of EPIRA. Meralco had a 10-year contract for the supply of electricity (CSE) from NPC beginning January 1, 1995. But in 2002 it opted to buy some of its electricity from its IPPs instead of from NPC. And Meralco has been accused of buying power from its affiliated IPPs at higher prices compared to the price charged by NPC.

The Meralco-NPC dispute continued through 2003, when, after mediation talks in the first half of the year, a settlement was reached on July 15, 2003. The Agreement was brought to the ERC, for its approval on April 15, 2005. In a joint filing to the ERC on January 20, 2006, NPC and Meralco showed that the net settlement amount payable to NPC and for collection from customers once approved by the ERC has been reduced from P20.05B to P14.32B. As of March 26, 2006, hearings on the joint application have already been completed and the case is still pending resolution by the ERC. (MERALCO Annual Report 2006).

In Mindanao, the dominant private power generation company is the Aboitiz Power Corporation. Aboitiz

and its subsidiaries have six power plants with a total installed capacity of 676.39 MW or 35 percent share of

the total Mindanao grid. Nationwide, Aboitiz owned or have controlling interests in 20 generation facilities with a combined installed capacity of 2,288.87 MW or 14 percent share of the national grid.

Aboitiz and its subsidiaries owned or have controlling interests in 10 generation facilities in Luzon which are equivalent to 12.3 percent of Luzon grid.

While in Visayas, it has two generation facilities with 119.7 MW or 6.53% share of the total Visayas grid.

Aboitiz also owns interests in various electricity distribution utilities that distributed 3,498 GWh of electricity to approximately 616,261 customers in the Philippines. The Visayan Electric Company or VECO is the second largest power distribution utility serving Metropolitan Cebu (Cebu City, Mandaue City, Talisay City, Naga City including the municipalities of Consolacion, Liloan, Minglanilla and San Fernando. Next on the list, the Davao Light and

Table 22.

Cities Municipalities Area Covered (sq.km)

Estimated Population (millions)

Metro Manila 13 4 636.00 10.99

Rizal 1 13 1,309.00 1.51

Bulacan 2 22 2,625.00 2.08

Cavite 3 20 1,297.00 1.91

Laguna 2 17 1,281.00 1.68

Quezon 1 10 1,780.00 0.79

Batangas 1 2 409.00 0.36

Pampanga - - - 0.06

Total 23 88 9,337 19.38

Source: MERALCO Annual Report 2006

Table 23.Mindanao Location in MW

1. Cotabato Light and Power Company Cotabato 10.00

2. Davao Light and Power Davao City 58.69

3. Southern Philippines Power Corporation Alabel, Sarangani 59.00

4. Western Mindanao Power Corporation Sangali, zamboanga City 113.00

5. Talomo Hydro Talomo, Davao City 3.70

6. Mindanao Coal-fired Thermal i and ii

PHiviDEC industrial Estate, villanueva, Misamis Oriental

232.00

7. Power Barge 118 Compostela valley 100.00

8. Power Barge 117 Agusan del Norte 100.00

TOTAL 676.39

Table 24.Luzon Location in MW

1. Duracom Unit 3 and 4 Navotas,Metro Manila 109.00

2. Ampohaw-Bineng Hydroelectric Sablan, Benguet 18.35

3. Magat hydroelectric Ramon, isabela 360.00

4-5. Ambuklao-Binga itogon, Benguet 175.00

6. Bakun hydro Alilem, ilocos Sur 70.00

7. Northern Mini Hydro Bakun, Banguet 12.40

8. Sal-anga (Philex) itogon, Benguet 0.50

9. Tiwi-MakBan geothermal complex

Albay, Laguna and Batangas

747.53

TOTAL 1492.78

Table 25.Visayas Location in MW

1. Cebu Private Power Corp. Cebu City 70.70

2. East Asia Utilities Corp. Cebu City 49.70

TOTAL 119.70

18 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

Power Company is the third largest distribution utility in the Philippines. Its franchise area covers Davao City, and Panabo City and the municipalties of Carmen, Santo Tomas and Dujali in Davao del Norte. Also in Mindanao, Aboitiz owned the Cotabato Light and Power Company serving the area of Cotabato City (including municipality of Dina-ig and parts of Sultan Kudarat province.

Aboitiz first power distribution utility in Luzon is the San Fernando Electric Light and Power Company which is considered the country’s seventh largest distribution utility serving San Fernando, Pampanga. The newest power distribution owned by Aboitiz is the Subic Enerzone Corporation which manages the whole power distribution system within the Subic Bay Freeport Zone. Mactan Enerzone Corporation of Aboitiz manages the Mactan Export Processing Zones (MEZ 2) while the power distribution system within the West Cebu Industrial Park is managed by Aboitiz-owned Balamban Enerzone Corporation.

The Global Business Power Corporation, a subsidiary of The Metrobank Group and the Global Formosa consortium is also a major player in Visayas with its six generation facilities with a combined

installed capacity of 249.48 MW. It controls 13.6% share of Visayas grid, next to First Gen’s 37% share.

Trans-Asia Power Generation Corporation of Executive-Vice President Victor Del Rosario. Trans-Asia Power is a subsidiary of Philippine Investment Management, Inc. (PHINMA). DOE former Secretary Francisco Viray is the current president. Trans-Asia

power has two power generation facilities, one in La Union (52 MW) and another in Guimaras province (3.40 MW) with a total installed capacity of 55.4 MW.

The Abaya-owned Cagayan Electric Power and Light Company (CEPALCO) have three

generation facilities and a distribution utility which covers the City of Cagayan de Oro and the municipalities of Tagoloan, Villanueva and Jasaan all in Misamis Oriental including the 3,000-hectare PHIVIDEC Industrial Estate. CEPALCO’s three generation facilities with a combined installed capacity of 26.9 MW have 1.4% share in Mindanao grid.

In terms of power generation by NPC-IPPs, three power generation facilities are under Mirant (TeaM Energy) with a total installed capacity of 2,332 MW. These are the 728-MW Pagbilao coal-fired in Pagbilao, Quezon, 1,294-MW Sual coal-fired in Sual, Pangasinan and the 310-MW

Hopewell power plant in Navotas. Mirant’s share in Luzon grid is 19 percent.

Under the Korea Electric Power Company (KEPCO) are the 1,271-MW Ilijan natural gas power plant and 650-MW Malaya thermal power plant. It also has controlling interest in SPC Power Corporation (former Salcon Power

Corporation) which owns the 109.3 MW-Naga Power Plant I and II in Naga City, Cebu, and 168.5 MW Panay and Bohol Diesel Power Plants. KEPCO power generation facilities have a combined installed capacity of 2,030.3 MW. Its two power generation facilities in Luzon i.e. Ilijan and Malaya have 15.7% share in Luzon grid.

Table 26.Luzon Location in MW

1. Sangi Power Plant Toledo City, Cebu 88.80

2. Panay Power Corp. La Paz, iloilo 74.88

3. Carmen diesel Toledo City, Cebu 45.80

4. 20-MW bunker fuel La Paz, iloilo 20.00

5. 15-MW bunker fuel Nabas, Aklan 15.00

6. 5-MW bunker fuel New Washington, Aklan 5.00

TOTAL 249.48

Table 27.Location in MW

1. Mindanao Energy Systems Brgy. Tablon, Cagayan de Oro City 18.90

2. Bubunawan hydro Baungon, Bukidnon 7.00

3. Solar photovoltaic Brgy. indahag, Cagayan de oro City 1.00

TOTAL 26.90

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 19

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

endnotes1 Patalinghug, Epictetus and Gilbert M Llanto, “Competition Policy and

Regulation in Power and Telecommunications”, Philippine institute for Development Studies, Discussion Paper Series No. 2005.

2 Open access refers to the system of allowing any qualified person the use of transmission, and/or distribution system, and associated facilities in which electricity end-users are free to choose where to get their supply of electricity.

3 EPiRA, Section 31.4 Contestable market refers to the electricity end-users who have a

choice of a supplier of electricity.5 EPiRA, Section 47-i.6 Retail competition and open access should have started not later

than three years after the law was passed.7 it was established as a special purpose company through which

Singapore-based AES Transpower Pte. Ltd. would bid for and hold the Masinloc power plant.

8 Suez-Tractebel is a Belgium-based utility company and one of the world’s top independent power producers.

9 A transition supply contract is a power supply agreement offered to NPC customers which state-owned generation facilities are still undergoing privatization.

10 Calaca coal-fired thermal power plant was sold to DMCi Holdings inc. last July 8, 2009 in the amount of $361.71M.

11 EPiRA, Chapter v, Section 47 (g)12 ADB Operations Evaluation Department, “Sector Assistance Program

Evaluation of Asian Development Bank Assistance to Philippines Power Sector,” September 2005, SAP:PHi 2005-09, p. 36

13 Congressional Planning and Budget Department, House of Representatives, Occasional Paper No. 5, Feb. 2007.

14 As of April 2009, the proceeds of the privatization of generation assets made NPC’s debts to $5B from $7B.

15 The generation mix refers to the proportion of the different fuel types used by NPC in the production of electricity.

16 ibid.17 ibid.18 ibid.19 includes Tiwi-MakBan geothermal plant complex20 Maitet Diokno-Pascual, “The Third Way: Shifting to People Power”,

unpublished, December 2005 21 Epictetus Patalinghug and Gilbert M. Llanto, “Competition Policy and

Regulation in Power and Telecommunications”, Philippine institute for Development Studies, Discussion Paper Series No. 2005-18.

22 Asian Development Bank (ADB), “Proposed Technical Assistance to the Republic of the Philippines for institutional Strengthening of Energy Regulatory Commission and Privatization of National Power Corporation,” December 2004, TAR:PHi37752-01, p. 1.

23 Epictetus Patalinghug and Gilbert M. Llanto, “Competition Policy and Regulation in Power and Telecommunications”, Philippine institute for Development Studies, Discussion Paper Series No. 2005-18.

24 MERALCO Annual Report 2006.

References:12th and 13th EPiRA implementation Status Reports, Department of

Energy.

Asian Development Bank, Proposed Loan and Political Risk Guarantee,

Republic of the Philippines: Privatization and Refurbishment of the

Calaca Coal-Fired Thermal Power Plant Project, Project Number 41958,

April 2008.

Aboitiz Power Corporation website, www.aboitiz.com

Department of Energy website, www.doe.gov.ph

First Philippine Holdings Corporation Annual Report 2007.

Freedom from Debt Coalition website, www.fdc.ph

National Power Corporation Annual Report 2007.

MERALCO Annual Report 2006.

Occasional Paper No. 5, Congressional Planning and Budget

Department, House of Representatives, February 2007.

Patalinghug, Epictetus and Gilbert M Llanto, “Competition Policy and

Regulation in Power and Telecommunications”, Philippine institute for

Development Studies, Discussion Paper Series No. 2005.

Pascual-Diokno, Maitet, (unpublished) “The Third Way: Shifting to

People Power”, December 2005.

Philippine Power Fact Sheet, Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC),

Quezon City.

Power Sector Assets and Liabilities Management website, www.psalm.

gov.ph

Power Statistics 2007, Department of Energy.

“Praymer sa Presyo ng Kuryente”, Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC),

June 2, 2008, Quezon City.

Rimban, Luz and Shiela Samonte-Pesayco, “Trail of Power Mess Leads

to Ramos”,

Philippine Center for investigative Journalism (PCiJ), August 2002,

Quezon City.

Rules and Regulations to implement Republic Act No. 9136 entitled

Electric Power industry Reform Act of 2001, February 27, 2002.

Wholesale Electricity Spot Market website, www.wesm.ph

20 PAID! Dark Power Rising November 2009

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

IPP NAME INSTALLED CAPACITY, MW IPP SPONSOR LOCATIONilijan Natural Gas Combined Cycle 1271.00 Kepco ilijan Corp. ilijan, Batangas

Sual Coal Units 1& 2* 1294.00 Mirant Power Corp. Sual, Pangasinan

Pagbilao Coal 1&2* 728.00 Mirant Power Corp. Pagbilao, Quezon

Bauang Diesel Power Plant 235.00 Bauang Private Power Bauang, La Union

Subic Diesel Power Plant 116.00 Enron Power Corp. Subic, zambales

Casecnan Multi Purpose Hydro 165.00 National irrigation Administration Casecnan, Nueva Ecija

San Roque Multi Purpose Hydro 345.00 Marubeni/Sithe San Manuel, Pangasinan

Bakun Hydro 100.75 AEv-NMHC-others Alilem, ilocos Sur and Benguet

Leyte B Geothermal 610.18 PNOC-EDC Tongonan, Leyte

TOTAL = 10 4,864.93

*privatized

annex b. lIsT of eXIsTInG PoWeR PlanTs

annex a: list of IPP Plants in luzon Grid for Transfer to IPP administrators

Luzon (as of September 2009)

PlantsCapacity MW

Location Proponent Owner Type of contract

Year CommissionedInstalled Dependable

Coal 3,783.00 3,055.70

Pagbilao Unit 1 364.00 364.00 Pagbilao, Quezon TeaM Energy Therma-

Luzon BOT-ECA 3/7/1996

Pagbilao Unit 2 364.00 364.00 Pagbilao, Quezon TeaM Energy Therma-

Luzon BOT-ECA 5/26/1996

Calaca 1 300.00 142.93 Calaca, Batangas DMCi Holdings inc. NON-NPC Privatized

July 8, 2009 9/5/1984

Calaca 2 300.00 160.71 Calaca, Batangas DMCi Holdings inc. NON-NPC Privatized

July 8, 2009 6/5/1995

Masinloc i 300.00 203.81 Masinloc, zambales

AES Transpower Pte. Ltd NON-NPC Privatized

July 26, 2007 6/18/1998

Masinloc 2 300.00 165.37 Masinloc, zambales

AES Transpower Pte. Ltd NON-NPC Privatized

July 26, 2007 12/1/1998

Sual i 647.00 590.87 Sual, Pangasinan TeaM Energy

San Miguel Energy Corporation

BOT-ECA 10/23/1999

Sual 2 647.00 562.01 Sual, Pangasinan TeaM Energy

San Miguel Energy Corporation

BOT-ECA 10/5/1999

Quezon Private Power Limited 511.00 460.00 Mauban,

QuezonQuezon Private Power Ltd. Philippines NON-NPC 5/1/2000

Asia Pacific Energy Corp. 50.00 42.00 Mabalacat, Pampanga

Asia Pacific Energy Corp. (APEC) NON-NPC 7/1/2006

Diesel 783.08 678.09

Enron Subic 2 116.00 114.46 Olongapo, zambales

Enron Power Corporation (USA) NPC-iPP BOT-ECA 2/22/1994

Duracom Unit 1 and 2 133.38 113.00 Navotas, Metro Manila NPC PSALM NPC 9/1/1995

East Asia Diesel (Duracom Unit 3 and 4) 109.00 109.00 Navotas, Metro

Manila East Asia Utilities NON-NPC 9/1/1995

Note: installed Capacity for NPC/NPC-iPP as per NPC Power Economics Dept. data. Assuming the privatization of Calaca and Masinloc,Ambuklao-Binga. Dependable capacity of NPC/NPC-iPP based on 2007 Average Dependable Capacity. Magellan Cogen: for confirmation on the operation of the power plant.

November 2009 Dark Power Rising PAID! 21

From state monopoly to de facto electricity oligarchy

Luzon (as of September 2009)

PlantsCapacity MW

Location Proponent Owner Type of contract

Year CommissionedInstalled Dependable

Angeles Pi DPP 30.00 30.00 Angeles City Angeles Electric Corporation NON-NPC 12/5/1994

Bauang Diesel Power Plant 235.20 225.33 Bauang, La

UnionFirst Private Power Corp. NPC-iPP BOT-ECA 8/30/1994

FCvC DPP 25.60 23.70 Cabanatuan City Cabanatuan Electric Corporation NON-NPC 1/15/1996

Tarlac Electric 18.90 12.60 Capas, Tarlac Tarlac Electric inc. NON-NPC 6/17/1905

Trans Asia Power 52.00 50.00 La UnionTrans Asia Power Generation Corporation

NON-NPC

Magellan Cogen (CEPzA) 63.00 0.00 Rosario, Cavite Magellan Cogen

Utilities NON-NPC

(ceased operation by June 30, 2003)

7/1/1995 - 1/1/1997

Natural Gas 2,834.00 2,565.42

San Antonio 3.00 3.00 Echague, isabela PNOC-EDC NPC-iPP 7/1/1994

Sta. Rita combined-cycle natural gas-fired Power Plant