Web Services Coordination (WS- Coordination) 1.1 - OASIS ...

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Cruise Companies and Terminals

-

Upload

uniparthenope -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Cruise Companies and Terminals

IAME 2013 Conference July 3-5 – Marseille, France

Paper ID 292

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Cruise Companies and Terminals

Assunta Di Vaio1 University of Naples “Parthenope”

Via G. Parisi, no. 13, Naples, Italy, +390815474135 [email protected]

Luisa Varriale University of Naples “Parthenope”

Via G. Parisi, no. 13, Naples, Italy, +390815474165 [email protected]

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to investigate the cruise events in the seaport systems as critical managerial and strategic tool for the increase of cruise passenger flows. In particular, we identify three typologies of cruise events (“cruise events on ship boarding”, “cruise events on ship berthing”, “cruise events on terminal”) and recognize their role in the organizational and managerial seaport models.

According to the literature on the hospitality industry, we recognize the main role played by the events in promoting and developing the revenues for the hotels (room occupancy) and their specific economic and social impact on the territory. Regarding the methodology, this is a theoretical study conducted through a review of the literature in order to clarify and systematize the main contributions on this topic and finally to identify new research perspectives.

Our theoretical study, also through the observation of some experiences in the cruise industry, evidences that the cruise events could be considered as effective managerial and strategic tools for the increase of cruise passenger flows; to achieve this goal it could be necessary the coordination and cooperation in the cruise event management process among players.

Keywords: seaport organizational model, cruise events, cruise companies, passenger terminals, marketing tools.

1 Corresponding author

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 2

1. Introduction

The cruise industry is in continuous growth, and is one important segment in the global tourism industry. This development phenomenon consists in the increase of passenger flows and the vessel gigantism, supported by the last reforms of the organizational, managerial and ownership models of seaport systems. Otherwise, all the players of the cruise industry (cruise companies, maritime stations or cruise terminals, Port Authorities, and local governments) search for and adopt managerial and strategic tools to increase the passenger flows.

In this scenario, the cruise events tend to play a critical role to support the growth phenomenon requiring a specific organizational and managerial process in which cruise companies and terminals need to coordinate and cooperate.

Through a review of the literature and the observation of some specific experiences in the cruise industry, the purpose of this study is to investigate the cruise events in this perspective briefly described, developing a taxonomy of the same cruise events and a theoretical design in which we clarify and systematize the link between the typologies of cruise events and organizational and operative implications in their management process.

This paper is structured as follows: the section 2 describes briefly the context, in particular

the Mediterranean cruise seaports, with particular attention to the managerial models of the

seaport systems in Italy; the section 3 analyzes the cruise events in the perspective of

managerial and strategic tools for the growth of the cruise industry. It reviews the main

contributions in the literature on event management and more specifically on hospitality

industry and cruise events; the section 4 concerns the taxonomy of the cruise events and the

development of the analysis model; finally, the section 5 evidences some considerations about

the phenomenon investigated.

2. Cruise industry in Mediterranean seaport systems: development process and managerial models

In the world economy, “the cruise line industry is considered to be the fastest growing leisure sector in the travel, tourism and hospitality industries” (Teye and Paris, 2011: 17). The modern cruise industry, a specific segment within the tourism and leisure and travel industry (Wild and Dearing, 2000), is relatively young; its growth rate has been almost twice the average rate of traditional land-based leisure travel (Teye and Paris, 2011). According to the European Cruise Council (ECC) 2012, more than 20 million cruise passengers enliven this sector and about 11.000 of them are managed from Mediterranean ports, involved in a gradual growth process, such as Barcelona, Civitavecchia, Venice, Pireo, Palma de Majorca and Naples (ECC, 2012).

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 3

This phenomenon concerns the increase of passenger flows and, at the same time, the vessel gigantism; in fact, in the last decades, the traffic flows significantly increase and the cruise companies tend to introduce new and larger ships. During the past 25 years the industry has considered new and progressively massive mega-liners, with “larger, more elaborate amenities and facilities, thus further mainstreaming cruising and making the experience more attractive to more consumers” (Gulliksen, 2008: 342). Both phenomena, the growth of passenger flows and the introduction of larger ships, require high quality standards of the port facilities. In the Mediterranean area, the management of these issues has been promoted from the last reforms regarding the seaport system, that concerned the efficiency of the infrastructures trough the concessionaire to private operators.

Regarding the Mediterranean area, its development in terms of traffic flows and competitive position in the cruise market, depends on several factors, which are: “attractiveness of the area/tourist destinations for the natural and artistic characteristics, seasonality of the area; infrastructures in the area (ports and passenger terminals); organization and operativity of each ports” (Soriani et al., 2009: 241); “the services package offered by maritime stations, and the organizational, ownership and governance model of port infrastructures” (Di Vaio and D’Amore, 2012, Di Vaio et al., 2011a, 2011b).

The guidelines of World Bank (2007) and UNCTAD (1992), aimed at improving the efficiency of port infrastructures, brought to a reorganization of functions and responsibilities in the seaport system. Considering as variables of analysis, the “ownership” and “management” of the areas and port facilities, it is possible to identify different port models recognizing public and private partnerships among the several players involved (Port Authorities and cruise companies). With reference to the organizational model of maritime stations in Italy, these public and private partnerships (PPPs) between Port Authorities (PAs) and cruise companies are favoured by the legislator that considers the maritime stations as “services of general interest”2. The Italian ports reform, establishing the impossibility for the Port Authority (PA) to delivery directly the port services, led to the growth of those PPPs, where the PAs have specific tasks, such as “policy, planning, coordination, promotion, monitoring and control of port operations and commercial and industrial activities” (see Law n.84/94 and the following modifications) and the cruise companies manage the infrastructures (Di Vaio and D’Amore, 2012). Long-term relationships between port institutions and cruise companies are governed by a specific agreement (concession agreement under landlord port model), in which the cruise companies participate into the management of maritime stations as concessionaires, sharing the management with PAs or the companies are the exclusive concessionaires (the ownership is completely private). In both cases, each partner has to respect strictly the concession agreement, that contains a specific clause requiring the parties to increase the traffic flows. 2 Article 6, paragraph 1, letter c) of the Act on January 28 1994, n. 84; Ministerial Decree November 14, 1994, published on G.U. November 24, 1994 n. 275.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 4

In the perspective of the development in the cruise industry, several factors can explain the interesting and relevant growth of the cruise industry in the Mediterranean area; these factors help to increase the passenger flows and the development of the ships. In particular, we can identify some factors that concur to these phenomena, such as the vessels gigantism, the creation of more competitive offers, and the pricing strategy. In fact, “the modern cruise industry emerged in the late 1960s and soon developed into a mass market using large vessels and adding more revenue-generating passenger services onboard” (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013: 31). In this context, the main managerial and strategic tools to create and maintain the competitive advantage for the cruise industry are the price, the product, thus the offered services, the relationships in terms of cooperation.

3. Strategic and managerial tools to support the cruise industry

Each organization within the seaport system tends to adopt specific managerial and strategic tools to increase the passenger flows. More specifically, in the cruise companies, product packages in terms of services offered, pricing strategy, strategic and operational choices like the itinerary and tourism destinations represent the main tools adopted. Regarding the services offered, in the cruise companies, we can observe more than in other kind of industry the core and the peripheral services: the former includes all the basic and central services related to the cruise companies and their specific activity such as transportation, cleaning service, food and beverage, well-being, status, comfort, entertainment, and so on; the latter concerns each service or facility that supplement and surround the core service, such as shopping centre on board, special events, and so on (Roth and Menor, 2003).

In the same perspective, Peručić (2010: 71) has identified the main factors that can explain the high average annual passenger growth rate: “the evolution of cruising to mass phenomenon thanks to lower pricing strategy, the internationalization of cruise companies, the gigantism in the industry (the economy of scale and the increase in demand for cruise vacations explain the reason to build increasingly larger ships), the deterritorialization of tourist destinations, capital and labour force, high value for money, and the successful implementation of marketing strategies”.

Regarding the pricing policy, Sun and colleagues (2011) argue that the cruise companies need to consider dynamic pricing policies, even if in this industry it “is more difficult than hotel and airline industries because the booking horizon is very long and the number of cabin types and fare classes are very large” (Sun et al., 2011: 753).

In summary, some authors focus on the previous aspects as pricing or services package (Raguz et al., 2012, Sun et al., 2011, Peručić, 2010); others, trying to identify different successful factors, investigate different issues, such as passengers’ motivation or perception, and so on (Teye and Paris, 2011, Teye and Leclerc, 1998).

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 5

In particular, some scholars examine passengers’ motivation for taking a cruise vacation, their travel-related activities while on vacation, and their preferences to return to each destination for a land-based vacation (Teye and Paris, 2011). In their survey study of cruise passengers on a 10-day itinerary with 6-ports-of-call from Miami, Florida to the Caribbean, using Push and Pull framework, Teye and Paris (2011) identify several and significant motivational factors, such as “experience nature, the outdoors, beautiful scenery”, “social activities”, “personalized, quality service, luxury of the ship itself”, “fine dining opportunities”, “comfort and security form being with people of similar interests”, and in detail “experience many activities and events in a relatively short time”. In this survey study, 165 respondents (over total 173) refer to the last motivational factor. This study evidences that cruise tourists participate in a wide variety of activities which can have large economic impacts on the destinations such as events on board or on terminal (Teye and Paris, 2011).

Despite the significant growth in the cruise industry, there are few studies in the literature yet that examine the successful factors in the sector, for this reason we consider studies in the literature on the hospitality.

Several studies on the hospitality industry investigate the main factors that can justify the customers’ behaviour, in particular they examine the relationship among hotel room prices, occupancy percentage and guest satisfaction (Mattila and O’Neill, 2003); indeed, prior research on the hospitality industry attributes to the price a key role in consumers’ quality perceptions, even if the exact nature impact of the price is still unknown (Oh, 2000, Lewis and Shoemaker, 1997, Bojanic, 1996, Parasuraman et al., 1991).

Mattila and O’Neill (2003) conclude that price was the main predictor of overall guest satisfaction and they also identify three key guest-satisfaction components: “guest room cleanliness, maintenance, and attentiveness of staff”. In this perspective, the price could also represent the key driver that can justify the growth of passenger flows in the cruise industry.

Otherwise, some authors evidence that “the formulation of a marketing strategy, strengthening hotel operations, and upgrading the quality of service, has become essential not only for profitability, but also for a hotel’s survival” (Hwang and Chang, 2003; Chen, 2007: 696). An important prerequisite of the overall market success is represented from the marketing effectiveness; in an increasingly competitive industry, firms, more specifically hotels, have to implement marketing as a business philosophy focused on the customer (Cizmar and Weber, 2000).

In this direction, hospitality firms, such as hotels, pay more and more attention to the services offered, in particular this is an ideal market which could benefit from the implementation of service innovation (Victorino et al., 2005). According to the conceptual background of the “service concept” in the perspective of “marketing concept”, some scholars recognize the marketing concept as “the key to achieving organizational goals and … determining the needs

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 6

and desires of target markets and delivering the fixed (customer) satisfactions more effectively than competitors…” (Agarwal et al., 2003: 68). Firms market-oriented are more able to understand their customers better than their competitors (Victorino et al., 2005).

Further studies evidence that many factors can affect the success of the hospitality industry, making it more competitive, such as the special events, these findings are derived from the application of interesting economic impact models (Bonn and Harrington, 2008), or considering the dynamics for meetings and conventions management (Toh et al., 2007).

Comparing the hospitality industry, exactly hotels, to the cruise industry, Toh and colleagues (2005) advance specific reasons (13 factors) why the cruise companies have out-done the hotels in cabin/room occupancy rates, grouped into three categories: “inherent structural advantages, idiosyncratic marketing conditions, and proactive management initiatives”. First, “cabins on cruise ships are perishable assets, they are nevertheless movable, and therefore can be relocated to follow demand” (inherent structural advantages) (Toh et al., 2005: 130); second, the cruise industry is not in the maturity stage of the tourism area life cycle, as hotel sector (i.e. Disney World)(idiosyncratic market conditions); third, “the cruise lines adopted specific initiatives: the development of a good all-inclusive product that has, according to repeated surveys, exceeded customer expectations; the consciously strengthening of their bonds with travel agents giving to form closer and more loyal ties; the institution of many safety features such as offshore registration, examination of all luggage, and issuance of photo identity cards; the introduction of unique on board spending cards that can record and analyze on board spending patterns by demographic groups; the lengthiness of the booking window for up to a year; the encouragement of passengers to purchase total transportation packages with air-bus-ship transfers” (proactive management initiatives) (Toh et al., 2005: 131-132-133).

Hence, in the cruise industry many are the supportive initiatives that can justify and stimulate the growth phenomenon.

Regarding the maritime stations, many tools support the increase of passenger flows such as port facilities, shopping centre, events on terminal and so on. Therefore, within this wide category of tools we identify the cruise events, which can contribute to the room occupancy (cabins) and enable the organizations, especially the cruise companies, to reach the break-even point. Cruise events can contribute for both the cruise companies and terminals to increase the passenger flows and, at the same time, cruise events can affect significantly the economy of the territory. Cruise events represent a common denominator among cruise companies, port terminals and territory; in fact, for each partner involved, cruise events could affect positively the economic and social development, i.e. for the territory by attracting new and more tourists, for the cruise companies and port terminals by increasing the passenger flows. At the same time, local events, especially mega events in the territory can affect positively the cruise industry, attracting the cruise companies to specific areas thanks to

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 7

innovative and more functional infrastructure and a particularly effective tourism policy; for instance, the port of Barcelona is currently one of the most important ports in the Mediterranean in number of quays, terminals and services to the cruise traffic after the several and consistent investments in the port that began prior to the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games (Soriani et al., 2009).

Otherwise, as it happens in the hospitality industry, where planning events has a positive effect on the room occupancy, at the same time the cruise events can contribute to reach the goal of high level of cabins occupancy.

4. Taxonomy and management of cruise events: an analysis model

Generally, events are an important tool for the development of the country; events are an important “motivator of tourism” (Getz 1997, 2000, 2008: 403, Pecchenino, 2002, Goldblatt, 1998, Ferrari, 2002) and “they figure prominently in the development and marketing plans of most destinations” (Getz, 2008: 403). “The roles and effects of planned events within tourism sector have been well documented, and are of increasing importance for destination competiveness” (Getz, 2008: 403).

The cruise events represent an interesting typology more than other events such as conference, workshop, fashion show, and so on, because of the involvement of many organizations (cruise companies, maritime stations, security agents, and so on) and the need of managerial and organizational tools for their planning and implementation process. Cruise events represent an interesting tool for the value creation of many organizations in the seaport system. Indeed, for cruise companies, cruise terminal and PAs, the cruise events become critical in order to attract new passengers, therefore the task in promotional function by PA (see Law 84/1994, art. 6) could not regard only the port promotion as tourist destination (Di Vaio and Pisano, 2011), but it could support both cruise companies and terminals in a wider national and international perspective by involving and promoting these same organizations in many other important events.

The events are classified in several categories considering different variables such as size, type, topic, and so on; in this perspective, cruise events can be investigated to evidence their main aspects in terms of characteristics, in fact, by considering the size (Bowdin et al. 2006; Van der Wagen 2005), cruise events can be classified as hallmark events but also as a typology of minor events (Di Vaio and Varriale, 2012). Cruise events are designed in order to increase the appeal of a specific cruise as it happens in the case of festivals to promote tourism destinations or regions, more specifically, some cruise companies plan special events “on board” such as The Cruise of Neapolitan Music in MSC Crociere. At the same time, cruise events represent minor events because they usually repeat every year, in each itinerary

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 8

such as concerts on board, meetings, parties, celebrations, award ceremonies, sporting finals, and many other social events are planned.

In terms of type (Bowdin et al. 2006; Van der Wagen 2005; Shone and Parry 2004; Ferrari 2002), cruise events may be categorized as “commercial, marketing and promotional events” and also as “meetings, conventions and exhibitions”, known as MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions), or more simply labelled as “Business events”. For istance, there is a specialized international company, called “Cruise and Business Events”, that plans and manages worldwide MICE Events on MSC Crociere cruise ships3. Expensive budgets and high profiles are required from the cruise events to promote and support the cruise core business that is the traffic flows; to reduce the high costs related to the process, the cruise companies tend to carry out all the activities to external specialized organizations and focus more on the “cabin occupancies”: “... in the cruise industry, the number of people in the cabin affects both the costs and revenues, and must be counted in measures of occupancy” (Toh et al. 2005: 130). In the cruise industry the room occupancy is the main revenue instrument to increase the cruise passenger expenditures on board, such as alcoholic drinks, casino operations, theatre and other board services, opposite to the hotel industry (Toh et al. 2005).

In the same category of cruise events, we can distinguish three specific sub-typologies on the basis of the actors involved and the content of events, in fact, we identify these specific manifestations (Di Vaio and Varriale, 2012): “cruise events on ship boarding”, “cruise events on ship berthing” and “cruise events on terminal”.

The “cruise events on ship boarding” consist in the events planned and managed from the cruise companies during the navigation (i.e. musical cruise, dancing cruise, tasting cruise, reading cruise, and so on), instead the events when the ship is stopping to the quay of the cruise terminal (i.e. presentation of projects of the “cruise events on ship boarding”, presentation of new partnership between the cruise company and other operators, awards, and so on) are called “cruise events on ship berthing”. Finally, the “cruise events on terminal” are events planned and managed directly by the port terminals, that are qualified like multi-business structures also for this reason because they dedicate their own slots for this kind of business area.

In this scenario above described, the organizational and managerial models adopted in the seaport systems can differently affect the cruise event management process; indeed, the cruise terminals could continuously interact with cruise companies in order to plan and manage the cruise events with the goal to increase the passenger flows. Their long-term partnerships become critical and are considered as “rapid and flexible approaches to attain complementary resources and may share costs and risks” (Ranaei et al., 2010: 20).

3 For more details see: www.cruiseandbusiness.com.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 9

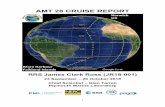

Within the managerial and organizational models (PPPs), we can develop one pattern distinguishing different ways to plan and manage cruise events. In this pattern, there are two main actors: cruise terminals and cruise companies (conceived as shareholder of the concessionaire). In our design there are different characteristics on the basis of the location of the cruise events. As shown in figure 1 below, when the cruise event is planned and managed on board during the navigation, the participants, called “cruise event participants”, who are already passengers enjoy the event without the need to visit the terminal; therefore, the event already supports the cabins occupancy achieving the goal of the cruise company. Instead, if the cruise event takes place on the ship berthing, it is possible to identify one typology of visitors, called “temporary cruise visitors”, that experiencing the event on board could become “cruise passengers”. In this case, between the terminal and cruise company there could be the common use and management of resources, such as hostess service or security service. In this perspective, we can see a directional movement from Box [2] to box [1]. In another situation, if the location of the event is the terminal infrastructure, thanks to coordinated and integrated activities between terminal and cruise companies during the stopping berthing of ships, it is possible to stimulate visitors for the event on terminal (called “event terminal visitors”) in order to visit the ship, so they could become “temporary cruise visitors”, in this case we see the moving from box [3] to box [2], “temporary cruise visitors” (i.e. visitors on board can participate to a buffet with food and beverage provided from the ship); also in this case the partners involved share resources and costs.

Finally, cruise companies and terminals can coordinate their activities in order to plan special cruise package offered to allow the cruise passengers to visit the terminal and enjoy special events planned and managed on land; in this case the visitors come from the ship, we assist to another process: cruise passengers become “cruise passengers on land”. In this perspective, both partners need to plan the itineraries of cruise package offered (see Figure 1, Box [4]).

For instance, applying our theoretical design, we can observe that in the seaport of Naples (Italy), in which there is the concessionaire of the terminal (Terminal Napoli S.p.A.), some cruise events are managed and planned during the year, such as medical conventions or meetings, i.e. the events “Congresso Nazionale Oncologia” (Oncology National Workshop), “Convegno Nazionale Centro Studi e Ricerche Fondazione AMD” (National Workshop Studies Centre and Researchers Fondazione AMD), and “Convegno Management in Medicina e Riabilitazione Sportiva” (Management and Medical Sport Rehabilitation Convention). In this case, the medical workshops participants (event terminal visitors) could become temporary cruise visitors if there is a coordination between the terminal concessionaire and the cruise companies in order to push the same participants to visit the cruise ships on the quay.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 10

CRUISE TERMINAL C

RU

ISE

SH

IP

On

bert

hing

Com

mon

are

as

Box [2]

Temporary cruise visitors

Box [3]

Event terminal visitors

In n

avig

atio

n

Cab

ins

Box [1]

Cruise event participants

Box [4]

Cruise passenger on land

Figure 1 – Cruise events on board and on terminal

Another typology of events planned and managed on terminal in Naples is represented from food and beverage events like the event “Cioccoland 2012 Galleria del Mare Porto di Napoli” (Chocolate event 2012 on terminal in Naples), that promoting the typical Neapolitan and Italian food culture, could give the chance to transform the event terminal visitors in the cruise event participants thanks to an effective and efficient coordination and control activity among the players directly and indirectly involved (terminal concessionaire and cruise companies).

In our design, it is clear the influence of some specific variables, whom management is crucial for the success of all the actors involved in the cruise event management process. In particular, an effective coordination is necessary and it is possible to make it only if we can manage specific factors: information complexity that concerns timing (length of the cruise, or the cruise event), number of actors involved, dimension of the ships, quality of the cruise companies involved (the main brand of the ships).

5. Conclusions

This paper contributes to the existing literature on the cruise industry investigating aspects that other studies on this specific issue have still not enquire, trying to develop previous ideas on this topic. In particular, we have observed how cruise events could be considered as effective managerial and strategic tools for the increase of cruise passenger flows in the seaport. In the cruise industry literature, there are only few studies on this phenomenon and they do not follow this perspective, for this reason we compare literature on hospitality to the cruise industry.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 11

We have focused on organizational and managerial models of seaport systems that can affect the cruise event management process, in fact, the concrete experience observed in the cruise industry has shown that the cruise events play an important role for all the partners in the seaport system. Each partner plans and manages cruise events in order to achieve its specific goals (increase of passenger flows) and tends to keep any information and data about the process, because of the high level of the competition in the cruise market. In our perspective, we tried to evidence, instead, that all the partners can achieve the same goal cooperating and sharing resources and costs; in this case, the different partnerships in the management and ownership of seaport system can represent the basic for the coordination and cooperation in the cruise event management process.

However, in order to obtain the increase of cruise passenger flows, it becomes relevant the coordination among the players involved in the event management process. Therefore, a critical variable it is represented by “integrated information systems” among cruise actors. An integrated and shared management of information can effectively and efficiently overcome the negative effects of high levels of uncertainty and complexity related to the cruise events.

Nevertheless, the information sharing about cruise events could to find a favourable opinion by the cruise companies because this would mean to share the skills with own competitors. So, if on one side the cruise companies could be adverse to the cruise event cooperation “on board”; on the other side, the situation could be different for the cruise events “on ship berthing” and “on terminal”. Indeed, in these last two cases, the cruise terminal “must play” an active role in stimulating the events “on terminals” ensuring also to cruise ships some levels of “temporary cruise visitors”.

Finally, this paper presents several limitations. First, this is a theoretical study based on the previous contributions in the literature, especially on the hospitality industry, and observations of few experiences in the cruise industry. Second, we have defined a model without exactly identifying the dimensions to measure and empirically test in the cruise industry. In the next step of this study, we propose to develop the analysis model clarifying in details the dimensions involved and the relationship among them in order to manage the cruise event process. In the future development of the theoretical design, we outline that it is more complex to investigate the “events terminal visitors” becoming “temporary cruise visitors” and then “cruise event participants” and not the contrary, because it is easy to collect data about how many and which “cruise event participants” or “cruise passengers on land” visit the terminal for shopping or events, and so on; i.e. in the case of medical workshops on terminal, the “event terminal visitors” have to respect strictly timing schedules and it is very difficult for them spend time to visit the cruise ships without a specific coordination activity between the terminal and the cruise company, also because there are formal rules regarding the security on board.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 12

References

AGARWAL, S., KRISHNA, E.M., and DEV, C.S., 2003, Market orientation performance in service firms: role of innovation. The Journal of Services Marketing, 17(1), 68-82.

BOJANIC, D. C., 1996, Consumer perceptions of price, value and satisfaction in the hotel industry: An exploratory study. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 4 (1), 5-22.

BONN, M. A., and HARRINGTON, J., 2008, A comparison of three economic impact models for applied hospitality and tourism research. Tourism Economics, 14(4), 769-789.

BOWDIN, G., ALLEN, J., O’TOOLE, W., HARRIS, R., and McDONNELL, I. (2006). Events Management. Elsevier Ltd. Australia.

CHEN, C.F., 2007, Applying the stochastic frontier approach to measure hotel managerial efficiency in Taiwan. Tourism management, 28, 696-702.

CIZMAR, S., WEBER, S., 2000, Marketing effectiveness of the hotel industry in Croatia. Hospitality Management, 19, 227-240.

DI VAIO, A., and D'AMORE, G., 2012, Cruise seaports networks: key relationship indicators and information systems. KMI International Journal of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, 4 (1), 33-55.

DI VAIO, A., and VARRIALE, L., 2012, Cruise companies in the cruise event management: key relationship indicators and coordination tools. Proceedings at the Conference IRAT-CNR Enlightening-Tourism, Naples, Italy, 161-177.

DI VAIO, A., MEDDA, F.R., and TRUJILLO L., 2011a, An Analysis of the Efficiency of Italian Cruise Terminals. International Journal of Transport Economics, 18, 29-46.

DI VAIO, A., MEDDA, F.R., and TRUJILLO L., 2011b, Public and Private management and efficiency index of cruise terminals. Proceedings of the European Conference on Shipping, Intermodalism & Ports, Chios, Greek, June, 1-13.

DI VAIO, A., and PISANO, S., 2011, The role of Information Systems in the Port Authority’s promotion activities. D’Atri A., Te’eni D., De Marco M. (Editors), Information Systems: a crossroads for organization, management, accounting and engineering. itAIS: The Italian Association for Information Systems, Springer, 1-8.

EUROPEAN CRUISE COUNCIL, 2012, The cruise industry. Contribution of cruise tourism to the economies of Europe.

FERRARI, S., 2002, Event marketing: I grandi eventi e gli eventi speciali come strumenti di marketing. CEDAM, Padova.

GETZ, D., 2008, Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tourism Management. 29 (3), 403-428.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 13

GETZ, D., 2000, Defining the field of event management. Festival Management and Event Marketing, 6 (1).

GETZ, D., 1997, Event Management & Event Tourism. Cognizant Communication Corporation Press, New York.

GOLDBLATT, J., 1998, The marketing stage. Event solutions. 5/1/98.

GULLIKSEN , V., 2008, The cruise industry. Symposium: touring the world., 45, 342-344, DOI 10.1007/s12115-008-9103-7

HWANG, S., CHANG, T., 2003, Using data envelopment analysis to measure hotel managerial efficiency change in Taiwan. Tourism Management, 24, 357–369.

LEWIS, R., SHOEMAKER, S., 1997, Price-sensitivity measurement: A tool for the hospitality industry. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 38(2), 44-54.

MATTILA, A. S., O’NEILL, J. W., 2003, Relationships between hotel room pricing, occupancy, and guest satisfaction: A longitudinal case of a midscale hotel in the United States. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 27(3), 328-341.

OH, H., 2000, The effects of brand class, brand awareness and price on customer value and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 24(2), 136-162.

PARASURAMAN, A., BERRY, L. L., ZEITHAML, V. A., 1991, Understanding customer expectations of service. Sloan Management Review, 39-48.

PECCHENINO, M., 2002, Organizzare gli eventi. Come gestire convegni, manifestazioni e feste per la comunicazione d'impresa. Il Sole 24 Ore, Milano.

PERUCIC, D., 2010, The importance of cooperative marketing in the development of sustainable cruise tourism in the Mediterranean, in: Leko Šimić, M. (Eds.) Sustainable development of tourism and agrotourism. Osijek: Faculty of Economics, 69-83.

RAGUZ, I. V., PERUCIC, D., PAVLIC, I., 2012, Organization and Implementation of Integrated Management System Processes-Cruise Prot Dubrovnik. International Review of Management and Marketing, 2(4), 199-209.

RANAEI, H., ZAREEI, A., ALIKHANI, G., 2010, Inter-organizational relationship management a theoretical model. International Bulletin of Business Administration, 9, 20-30.

RODRIGUE, J. P., NOTTEBOOM, T., 2013, The geography of cruises: Itineraries, not destinations. Applied Geography, 38, 31-42.

ROTH, A. V., and MENOR, L. J., 2003, Insights into service operations management: A research agenda. Production and Operations Management, 12(2), 145-164.

SHONE, A., and PARRY, B., 2004, Successful Event Management. 2nd Edition. Thomson Learning, London.

Cruise Events in the Value Creation: Coordination between Liner Companies and Passenger Terminals

ID 292

IAME 2013 Conference, July 3-5– Marseille, France 14

SORIANI, S., BERTAZZON, S., DI CESARE, F., 2009, Cruising in the Mediterranean: Structural aspects and evolutionary trends. Maritime Policy & Management: The flagship journal of international shipping and port research, 36(3), 235-251.

SUN, X., JIAO, Y., TIAN, P., 2011, Marketing research and revenue optimization for the cruise industry: A concise review”. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 746-755.

TEYE, V., LECLERC, D., 1998, Product and service delivery satisfaction among North American cruise passengers. Tourism Management, 19(2), 153-160.

TEYE, V., and PARIS, C. M., 2011, Cruise Line Industry and Caribbean Tourism: Guests' Motivations, Activities, and Destination Preference. Tourism Review International, 14(1), 17-28.

TOH, R. S., RIVERS, M., and LING, T. W., 2005, Room occupancies: Cruise lines out-do the hotels. Hospitality Management, 24, 121-135.

TOH, R. S., PETERSON, D., and FOSTER, T. N., 2007, Contrasting Approaches of Corporate and Association Meeting Planners: How the Hospitality Industry Should Approach Them Differently. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9, 43-50.

UNCTAD, 1992, Development and improvement of ports. The principles of modern port management and organization. Report by the UNCTAD secretariat. TD/B/C.4/AC.7/13.

VAN DER WAGEN, L., 2005, Event Management for Tourism, Cultural, Business and Sporting Events, 2nd Edition. Pearson Education Hospitality Press, Australia.

VICTORINO, L., VERMA, R., PLASCHKA, G., DEV, C., 2005, Service Innovation and Customer Choices in Hospitality Industry. Managing Service Quality, Special Issue on service Innovation. 15 (6), 555-576.

WILD, P., and DEARING, J., 2000, Development of and prospects for cruising in Europe. Maritime Policy & Management, 27 (4), 315-333.

WORLD BANK, 2007, Alternative port management structures and ownership models. Module 3. Port reform toolkit (2nd Edition).