Crossing Borders: Contemporary art in the United Arab Emirates Introduction Displaying and...

-

Upload

westernsydney -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Crossing Borders: Contemporary art in the United Arab Emirates Introduction Displaying and...

Crossing Borders: Contemporary art in the United Arab

Emirates IntroductionDisplaying and collecting art forms from the Middle East,

especially in the West since September 11 2001 and the Iraq

war of 2003, has become a global phenomenon. Public and

private, institutional and individual agencies interest in all

types of Middle Eastern art (ancient/ modern Islamic and

International art) has been increasing at unparalleled rates.

Cultural production backed by foreign capital and the

establishment of branches of auction houses such as Christies,

Sotheby’s, Phillips De Pury and Bonham’s have further

propelled the region internationally.1 By 2013 the sale of

Middle Eastern art had increased by 500%2 with Sara Plumbly,

Christie’s London office director of sales, agreeing that ‘all

eyes the world over have turned to the Middle East’.3

For the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a nation barely four

decades old, to be competing on the international stage with

traditional artefact suppliers such as Iran, Egypt, Syria and

Lebanon, is significant. All seven emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai,

Sharjah, Ras Al Khaimah, Fujairah, Ajman and Umm Al Quwain)

realise their regions past reliance on fossil fuels to sustain

their economies is limited and are keen to invest in

commodities other than natural resources to ensure future

economic security. With a clear and practical economic policy

1 S. Mejcher-Atassi, and J.P. Swartz, ‘Introduction’ in Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World .London: Ashgate, 2012, p. 12.2 C.M ‘Art in the Middle East: An Avenue of free expression’, The Economist, April 3, 2012. Retrieved from http://ww.economist.com3 CNBC.com., ‘Islamic Art: More than religious artefacts’, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com

1

in mind, cultural tourism has become the preferred avenue for

a successful financial future especially in the UAE’s biggest

two states: Dubai and Abu Dhabi. International interest from

outside the UAE and substantial growth in Arab artists who are

responding through the arts to their social, political and

economic realities have created ideal conditions for a

thriving art and cultural market to continue its dramatic

growth.

This rapid journey to become a cultural Mecca to rival Europe

has drawn scholarly interest but scant attention has been

given to cultural development prior to the last decade when

international collectors and auction houses began to take an

increased interest in the art of the region, especially the

work of contemporary artists. Additionally, as Robert Kluijer

argues, there has been an absence of a ‘broader understanding

of how contemporary visual arts both reflect and stimulate the

broader socio-cultural development in the region’.4 Despite the

fact that many of the artists practicing in the UAE aren’t

‘natives’ and trained overseas5, distinctive styles are

developing that are intricately linked to and reflective of

their own individual, community and national identities while

4 R. Kluijiver ‘Introduction to the Gulf Art World’, Gulf Art Guide. Retrieved from gulfartguide.com/g/GAG-Essay, 2012, p.4.5 The population of the UAE is approximately 5,314, 317 (July 2012estimate). This comprises: 19 percent Emirati, 23 percent other Arab andIranian, 50 per cent South Asian, and 8 percent other expatriates (includesEuropeans and East Asians). UAE citizens make up less than 20 percent.Local labour shortages, in the absence of income tax and relatively highwages, have resulted in encouraged a substantial number of male expatriateworkers to the UAE. Retrieved from Ethics, Equity and Social Justice’,United Arab Emirates, Cultural Sensitivity Notes, Curtin University ofTechnology, UAE.pdf

2

simultaneously responding to and incorporating global trends

and influences.6

Patronage in the Middle East has traditionally been a ‘top-

down’ system relying on commissions from the region’s ruling

families with sparse government funding, local or collective

interest or international sponsorship. Therefore local patrons

and their aesthetic preferences, expectations and world views

have impacted profoundly on the regional art scene.7 This

situation, coupled with negative stories and images of the

Middle East, Muslims and Islam fuelled by ‘clash of

civilisations’ rhetoric and sensationalised media reporting in

the West, has drawn criticism. Issues include the influence of

traditional Islamic doctrine, censorship, lack of democracy,

human rights abuses and the treatment of women. Unequal gender

laws especially have presented the West with a picture of

uniformly oppressed and marginalized groups, forbidden from

engaging in practices such as the creative industries.

Surprisingly, it is in spite of these patriarchal societies

that women artists are finding their voices, outnumbering and

out selling their male contemporaries. The focus of this essay

is the current Three Generations travelling exhibition which is

showcasing twelve artists from the Al Dhafra region of the

UAE, eight of them women. The premise that travelling

exhibitions, whose objects have been temporarily removed from

their permanent homes and reinstalled in new spaces, have a

greater capacity to be represented in ways that can

6 R. Kluijiver, 2012, p. 6.7 Ibid, pgs. 11-15.

3

potentially shatter stereotypes, redefine identities and build

cross-cultural understanding on national and international

levels, is explored. Also investigated is whether these

successes can translate into global careers for these women

(and UAE artists generally) and what the unprecedented scale

of art and cultural development entails for local and national

identity of this emerging nation.

The EventThree Generations is currently showing at Sotheby’s in London,

then Cleveland Clinic Arts and Medicine Institute USA and

finally displayed back home in Al Dhafra. In addition to their

main sponsors Sotheby’s and the newly formed philanthropic

body Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation (ADMAF), the

exhibition is under the patronage of HH Sheikh Hamdan bin

Zayed Al Nahyan (Ruler’s Representative of the Western

Region), Sheikh Nahayan Mabarak Al Nahyan (UAE Minister of

Culture, Youth and Community Development President and patron

ADMAF) and Her Excellency Hoda I. Al Khamis-Kanoo (Founder of

ADMAF). No doubt this co-operation between the highest levels

of UAE government and an international auction house raises

questions about the direction of art and culture in the Middle

East often seen as simply following market-orientated

practices/ strategies and dictated by state authorities.8This

is the first time Sotheby’s has displayed Emirati art,

maintaining the exhibition is ‘non-commercial, so there will

be no auction’ and that artists will benefit from the

8 S. Kamel, C. Gerbich & S. Lanwerd, ‘Do you speak Islamic Art? The Museological Laboratory’ in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B Junod, G. Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012, p. 206.

4

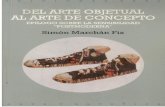

‘exposure’.9 However, there is an obvious commercial focus: the

catalogue announces the latest Sothby’s auction achieved the

highest sale of a ‘living Arab Artist’ in Chant Avedissian’s

Icons of the Nile artwork (figure 1), selling for a record

$15,199,750.10 In addition, visitors are told if they want to

purchase a work gallery staff can put them in contact with the

artist.11

Figure 1

The rhetoric surrounding the display, however, is far more

philosophical and inspirational. Executive Vice President and

Chairman of Sotheby’s International, Robin Woodhead, who

writes that this ‘snapshot of UAE artistic expression ...

9 S. Radan ’12 Emirati artist to exhibit at Sotheby’s’, Khaleej Times, 9 July 2013. Retrieved from htpp://www.khaleejtimes.com10 Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue,2013, p.19.11 C. Lord ‘Works by UAE artists go on show in London’, The National, July 24,2013. Retrieved from http://www.thenational.ae

5

[reveals] the evolution of contemporary artistic practices

based upon a rich understanding of the local culture and

heritage ...’ resonates with Sheikh Hamdan’s belief that ‘the

visual arts have the power to transcend borders and boundaries

...’, Sheikh Nahayan’s desire to ‘... communicate the essence

of the UAE cultural identity to the world...’ and Hoda I. Al

Khamis-Kanoo’s view that ‘Artists are essential to society.

They challenge commonly held perspectives with innovative

thinking. They raise awareness about issues, break down

barriers to cross-cultural understanding and encourage global

dialogue...’12

The WorksAll Three Generation artists displayed work at the 2013 Abu Dhabi

Festival and are members of the an ADMAF initiative, the

Nation’s Gallery, introduced in 2010 to ‘support Emirati

artists at home and abroad’.13With the mandate to ‘represent

the creative practices of three generations’ by investigating

‘... our past, our present and our future’ four works by women

artists14 that explore the position of women in Middle Eastern

patriarchal societies are: the mixed media work Untitled by

Najat Makki; paintings Diffused by Shamsa Al Omaira and Emirati

12 Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue,2013, pgs. 9-13.13 S. Radan ’12 Emirati artist to exhibit at Sotheby’s’, Khaleej Times, 9 July2013. Retrieved from htpp://www.khaleejtimes.com14 Many Emirati women (including these 4 artists) wear traditional dress as proscribed under Islamic law as a symbol of national identity and pride including the ab’a (black robe), the shailah (headscarf) and sometimes the burqa (covering the whole face). Retrieved from Ethics, Equity and Social Justice’, United Arab Emirates, Cultural Sensitivity Notes, Curtin University of Technology, UAE.pdf

6

Burqa by Karima Al Shomaly; and Sumayyah Al Suwaidi’s digital

art piece Feminine Delicacy.

Veteran UAE artist Dr. Najat Makki has exhibited both

nationally and internationally since her first exhibition in

1989 at the Dubai Al Wasl Club, receiving the UAE National

Award of Arts in 2008. She was the first Emirati woman to be

awarded a scholarship to study abroad and her early career

focused on expressionism and symbolism. Makki describes her

artistic practice as based on rhythm and tone with colour

functioning to ‘strengthen the density and dynamism’ of her

art forms. Using her fingers rather than brushes to apply

henna and saffron because ‘they belong to the Emeriti

culture’, Untitled (figure 2) shows her progression from purely

abstract forms to the incorporation of figurative elements

with designs combining colour, strong lines and textural areas

of mixed media to produce a feeling of harmony and constant

rhythm. The female figure, though off- centre, shadowy, veiled

and positioned facing a stately and pharonic form, exudes a

dominant and compelling female presence, likened to a ‘palm

tree touching the sky, yet grounded with roots digging deep

into the earth’.15This is characteristic of her work which

abounds with images of iconic women who symbolically embody

characteristics such as ambition, patience, struggle, optimism

and love.16

15 Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue,2013, p. 30.16 Ibid.

7

Figure 2

Abu Dhabi born visual artist Shamsa Al Omaira relies on

personal experiences to explore a diversity of concepts

including the intricacy of the mind, thought processes, memory

and philosophy. She maintains ‘art without a thought or strong

idea behind it is just a beautiful object that could be

marketed or sold ...’17 Utilising a range of mixed media

(painting, photography, printmaking, found objects and

installations) she creates works motivated by memories of

childhood and treasured possessions, becoming ‘personal

confessions’. Al Omaira exhibits regularly, most recently at

the 2011 Venice Biennale and at the Ghaf Art Gallery in Abu

Dhabi in 2012. Her acrylic and graphite triptych titled Diffused

(figure 3) is a self portrait depicting her ‘struggle to

restrain my personality, and the frustration in wanting to be 17 Artist website htpp://shamsaalomaira.com

8

accepted’ and the pressure to curb her character to please

others. The obscuring of her true personality is represented

by the lampshade dispersing the light that would otherwise

interfere with seeing. The artist explains that the lampshade

is a ‘metaphor for being trapped, hidden and concealed. The

clowns symbolise curiosity, nosiness and the games people

play. Viewing them from a distance they are deliberately

inconspicuous. Their size indicates insignificance and

weakness.’18

Figure 318Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue, 2013, p. 34.

9

The strongest comment on socio-cultural issues is Karima Al

Shomaly’s painting Emirati Burqa (figure 4), questioning ‘why do

people feel driven to wear this invisible mask? Is that mask

now a requirement of modern life?’19 After a lengthy

exploration, she has defined the Burqa as: ‘a physical and

symbolic expression of the invisible mask worn by people in

their daily life’. She investigates ‘what exactly the Burqa

means to the other’ especially from the mental, psychological

and creative perspective when worn in other countries and

cultures.20 Al Shomaly conducts her own research into reactions

to the Burqa concluding the ‘invisible Burqa makes it user

uncomfortable’.21The heavy, painterly layered off-white

background contrasts with the stencilled outline of the black

Burqa image, central but seemingly lost in the wide expanse of

the textured and uneven space of the square canvas. She

maintains: ‘As an artist, I always place the human experience

at the centre of my work. I want to explore the social,

political and philosophical issues that people face ... The

work does not offer solutions to problems but reveals the

truth of the world as I see it’.22

19 Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue,2013, p. 40.20 Ibid.21Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue, 2013, p. 41.22 K. Al Shoaly, ADMAF website. Retrieved from http://admaf.com

10

Figure 4

The last and youngest artist under discussion is Sumayah Al

Suwaidi: successful fashion designer, writer, musician,

dancer, performer, jewellery maker and the UAE’s first female

digital artist. Since beginning her career in 2001 she has

exhibited in many countries (UAE, Kuwait, USA, Germany,

France, China and Morocco), received local and international

commissions and been the recipient of no less than 3 national

(2010 Arab Woman Award, Emirates Woman Achievers Award and

Emirati Woman of the Year both in 2011) and the 2012

International Award of Petrochem GR8! Women Awards.

Similar to Najat Makki, Al Suwaidi works promotes love,

optimism and happiness through ‘people who are driven by

passion to succeed and make their own path’ experiencing and

sharing life’s highs and lows. Akin to Al Shomaly’s

sentiments, she hopes people ‘reach a stage where they feel

11

liberated and free to think and do as they please’.23 Acclaimed

for manipulating ‘seemingly normal, boring photographs into

masterpieces of emotions and sensuality’,24 Feminine Delicacy

(figure 5) is a digital photographic collage incorporating

distortions of the human body, fashion and nature in the form

of leaves and flowers in subtle and muted shades of gold,

orange with dark tonal highlights enclosed within a gilded

frame. The central figure of a female alludes to finery and

elegance yet is juxtaposed with a solemn facial expression and

dominant stance intended to represent authority and power.

23 Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, Exhibition catalogue,2013, p. 43.24 Ibid.

12

Figure 5

Local ConcernsWhile artworks showcased in travelling exhibitions such as

Three Generations certainly raises the profile of their creators

and demonstrates the increase in women participating in the

arts in the UAE, there is speculation that the majority of

females in the Middle East face obstacles that may ultimately

prove insurmountable in the long term. For example, the

expectation that family responsibilities cannot co-exist with

careers and restrictions about working or travelling without

family permission are problematic.25 On the other hand, some

commentators are accusing Emirati women of not ‘thinking big’

as their male counterparts do in the entrepreneurial sense and

are being criticised for making traditional choices like

retail, fashion and crafts. This situation is exacerbated by a

general lack of knowledge of women’s rights and access to

loans to finance businesses.26

Although Emirati artists are receiving increasing

International recognition, acclaim at home is often non-

existent. Artists such as Adbul-Raheem Sharif, founder and

chief executive of the non-profit institution The Flying House

which promotes local artists, maintains the biggest problem in25 Emirati women are allowed to drive, work, attend school and university and own property and businesses. However, women are not permitted to live alone or with a male outside of marriage and are only permitted to engage in sports activities with other women. Emirati women do not usually attend official events or meetings. Islamic law places the rights of the society over that of the individual and therefore, people risk punishment if any action disrupts the peace. For more detail see ‘Ethics, Equity and Social Justice’, United Arab Emirates, Cultural Sensitivity Notes, Curtin University of Technology. Retrieved UAE.pdf 26 Arabic Knowlege@Wharton. Retrieved from http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu

13

the lack of education in the arts of the general population

and absence of public and school art based education programs.

Despite art fairs, festivals, biennales and art prizes, Sharif

complained that few multinational companies and local banks

have corporate art collections. He argues since all energies

are being directed at constructing and displaying

international art in the Guggenheim and Louvre museums, no one

appears to be catering solely to the local context.27

There is also concern that cultural and artistic developments

are purely investment vehicles subject to market manipulation

and that the lack of qualified and experienced local

professionals, such as independent curators, academics and art

critics, needs to be addressed for there to be a real local

and national identity representation. Furthermore, many are

questioning the future of those who decide not to be ‘market

artists’? Sara Rahbar convincingly argues in an ‘uncertain’

industry:

... based solely based on opinions, an artist has

to play his or her cards very carefully regardless

of the nature of the market. Some get greedy and

never come out the other end, some don’t take enough

risks and miss the opportunity altogether and some

benefit more than the dealers and the auction

houses, but come out the other end washed out ... 28

With Saayidat Island Cultural Complex (due for completion in

2015) to add to their numerous art and culture fairs, 27 N. Samaha ‘UAE artists want a piece of the action’, The National, Nov 19, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.thenational.ae28 S. Zakharia ,’Contradicitions and Developments: Market and Art Culture inthe UAE’, Nuktaart Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.nukaartmag.com

14

biennales, commercial galleries and international auction

houses, the UAE is unquestionably increasing their ‘cultural

credentials’ to become successful players in the global art

market.29 Nevertheless, concerns over the possible lack of

future audiences (especially locally) for these museums, the

place of the local artistic practice and national identity and

whether the UAE is ‘buying a cultural identity rather than

developing it’ are compelling arguments that require

consideration.

Global IssuesIn terms of the wider conversation, artist’s regardless of

gender face a multitude of challenges about how their art

works will find their way into national and international

collections. Many have worked in the tradition of

Expressionism and Arab Modernism, with abstract painting

becoming increasing popular because of religious taboos

prohibiting figurative depictions but are often accused of

producing work that is ‘meaningless’ and not ‘contextualized’

due to its strong association with the tourism and investor

sectors. Additionally, modern technologies and new media’s

have made world art both democratic and homogenous, risking

local traditions and narratives becoming ‘embedded in global

vocabularies’. 30 The many social and political constraints,

especially in conservative and religious societies such as

those dominating the Middle East, means contemporary artists

fear reprisals which can reduce their chances of being

29 R. Kluijver, 2012, p. 62.30 S. Raza, in A. Akkermans, ‘The Curators View’, The Mantle- a forum for progressive critique’, January 22, 2013. Retrieved from mantlethought.org

15

acquired by private and public collections. Touring shows have

greater freedom to display art works of a more controversial

nature than most permanent collections in museums but they

have a limited life and do not have the capacity to attract

all audiences.

Historically the inclusion of contemporary art from the Middle

East in many collections has been problematic. The majority of

prominent collections have focused on acquisitions of

traditional and medieval objects to the exclusion of

contemporary art, which is viewed as being global rather than

national or ethnic art.31 Furthermore, auction houses often

label these art works as ‘contemporary Islamic art’ which

risks continuing the essentialisation of Middle Eastern art as

monolithic, static and always religious, perpetuating the

tradition of excluding non-western arts from contemporary art

museums.32

Despite these debates, many museums are responding to audience

research which reveals that the inclusion of contemporary art

works makes ‘historical objects more relevant to the public’.33

There is the belief that by highlighting ‘patterns of global

experience’ and facilitating a ‘visual dialogue’ this may

create a ‘tension’ by exposing the visitor (especially for

audiences who believe Islamic and Arab art to be only medieval

and solely decorative) to issues of contemporary cultural 31 S. Weber, ‘The Role of the Museum in the Study and Knowledge of Islamic Art’, in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B Junod, G. Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012, p.27.32 V. Beyer, ‘Preliminary Thoughts on the Entangled presentation of “IslamicArt’”, in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B Junod, G. Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012, p. 96.33 S. Lanwed, ‘The Aesthetic Approach’ in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B Junod, G. Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012, p. 203.

16

production. Such an environment has the possibility of

encouraging reflection on contemporary representations of

Middle Eastern cultures which could foster new insights and

promote cross-cultural understanding.34

Worthy of mention but beyond the scope of this paper is the

contentious issue of how ‘value’ is attributed to art: is it

driven by market forces only or are there a wider range of

factors in circulating art forms and attributing value? Some

commentators such as Iain Robertson believe market forces

entirely control distribution systems and critic Robert Hughes

argues that such a network is essential.35 Although the

curatorial process attributes value to artworks more expert

curatorship, publications and criticism is needed for this

region’s cultural and artistic sector to move beyond the

purely ‘descriptive approaches’ that predominates. 36

ConclusionRegardless of these debates and criticisms, exhibitions such

as Three Generations are examples of new government initiatives

and international co-operation working along-side the

34 Ibid.35 Alan Bowness discusses the conditions of success for artists to become recognized requires four stages: peer recognition, critical recognition, patronage by collectors and dealers and public acclaim. In this theory, nations who are seeking to have their collections valued internationally have nine steps to complete on their path to success: perceived as politically stable countries, education especially in art and culture, government policies supporting art/cultural programs and attracting foreigninvestment, building museums, organizing biennales, establishing local commercial galleries, attracting and encouraging collectors, auction housesand art fairs. For a detailed account of how it applies to the UAE refer to S. Sabella ‘Isthe United Arab Emirates constructing its Art History? The Mechanisms that Confer Value to Art’, Contemporary Art Practices Journal, Vol. IV.36S. Raza, 2013.

17

traditional patronage of the ruling families to create new

spaces for dynamic and innovative displays of Emirati artists.

Women especially, who are reacting in nuanced ways to their

socio-cultural circumstances, can become significant players

in the development and maintenance of a fluid and vibrant

artistic scene that is not ‘imported’ but home grown.37

Economic diversification, the development of a solid art

infrastructure based on educating the public in art

appreciation and cultural awareness and the necessity for

local creative industries, will all contribute to critical

reflection at home and abroad. Only then will there be a

greater chance of redefining identities and shattering

stereotypes of what the modern Middle Eastern individual and

nation is beyond the impact of a travelling art display.

37R. Kluijver, 2012, pgs. 74-80.

18

ReferencesBooks

V. Beyer, ‘Preliminary Thoughts on the Entangled presentation

of “Islamic Art’”, in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B Junod, G.

Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012.

S. Kamel, C. Gerbich & S. Lanwerd, ‘Do you speak Islamic Art?

The Museological Laboratory’ in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B

Junod, G. Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012.

S. Lanwed, ‘The Aesthetic Approach’ in Islamic Art and The Museum,

Ed. B Junod, G. Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi,

2012.

S. Mejcher-Atassi, and J.P. Swartz, ’Introduction’ in Museums

and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World. London: Ashgate, 2012.

S. Weber, ‘The Role of the Museum in the Study and Knowledge

of Islamic Art’, in Islamic Art and The Museum, Ed. B Junod, G.

Khalil, S. Weber and G. Wolf. London: Saqi, 2012.

Journals/Newspapers

CNBC.com., ‘Islamic Art: More than religious artefacts’, 2012.

Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com

C.M ‘Art in the Middle East: An Avenue of free expression’, The

Economist, April 3, 2012. Retrieved from http://ww.economist.com

19

R. Kluijiver ‘Introduction to the Gulf Art World’, Gulf Art Guide.

Retrieved from gulfartguide.com/g/GAG-Essay.2012

C. Lord ‘Works by UAE artists go on show in London’, The

National, July 24, 2013. Retrieved from

http://www.thenational.ae

S. Radan ’12 Emirati artist to exhibit at Sotheby’s’, Khaleej

Times, 9 July 2013. Retrieved from htpp://www.khaleejtimes.com

S. Raza, in A. Akkermans, ‘The Curators View’, The Mantle- a

forum for progressive critique’, January 22, 2013. Retrieved

from mantlethought.org

N. Samaha ‘UAE artists want a piece of the action’, The National,

Nov 19, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.thenational.ae

S. Zakharia ,’Contradicitions and Developments: Market and Art

Culture in the UAE’, Nuktaart Magazine. Retrieved from

http://www.nukaartmag.com

Blogs, Websites

S. Al Omaira, artist website htpp://shamsaalomaira.com

K. Al Shoaly, ADMAF website. Retrieved from http://admaf.com

Arabic Knowlege@Wharton. Retrieved from

http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu

20

Curtin University of Technology, ‘United Arab Emirates,

Cultural Sensitivity Notes’, Ethics, Equity and Social Justice, UAE.pdf

Catalogue

Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation, Three Generations, exhibition

catalogue, 2013. Retrieved from www.admaf.org

All images courtesy of Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation

(ADMAF).

21