Creating the collaborative organisation: the promise of relationship management

Transcript of Creating the collaborative organisation: the promise of relationship management

Creating the Collaborative Organisation: The Promise of Relationship

Management

Jane Coughlan, Mark Lycett and Robert D. Macredie

Department of Information Systems and Computing, Brunel University, Uxbridge, UB8 3PH, UK

Email: [email protected] [Coughlan]; [email protected] [Lycett];

[email protected] [Macredie]

Abstract

Collaboration within an organisation can be said to be

subject to the effective management of relationships.

This study focuses on one such relationship, that between

the business and IT sides of an organisation, which need

to communicate and coordinate their activities for the

successful development of working systems. The

management of this key organisational relationship has

been given increased attention with the set-up of

‘Relationship Management’ programmes, envisioned to

mediate and improve organisational relations, strategy

and performance, by bridging activities between the

business and IT. To investigate the potential efficacy of

such an initiative, this study looks at Relationship

Management within a major UK bank, with the aid of a

communication framework. Interviews with 29

individuals from the mid-high management level of the

retail business and IT departments revealed mixed

perceptions of the efficacy of such a programme. The

merits of such an initiative in creating a one-team culture

within this organisation are debated against the backdrop

of the underlying problems that this particular

organisation faces.

1. Introduction

The concept of Relationship Management (RM) has

risen to prominence in recent times as a strategy for

creating, improving and managing relationships to acquire

and maintain a strong customer base for continued

competitive advantage [1]. The particular relationship

placed under research scrutiny has typically been focused

on external collaborations: business to the customer, or

business-to-business encompassing dealings of the

business (both international and domestic) with various

suppliers or partners [e.g., 2]. This study focuses on an

organisation within the retail banking industry (referred to

as FinCo hereafter for confidentiality purposes), where

the concept of RM has proved particularly attractive, with

their focus on delivering the best financial products to

their customers [3]. Increased pressures to be innovative

and financially successful however have rendered

effective internal, external and cross-functional

communication essential especially with co-ordinating

activities with existing services and infrastructure,

particularly in IT, which is largely responsible for

generating business solutions [4]. However, it is

proposed here that the business side of a single

organisation can (and should) also be viewed as the

‘customer’ — clients of the organisation’s own IT

division and it’s within this context of the business-IT

(BIT) relationship that RM is discussed.

The BIT relationship is so crucial to the functioning of

the business as a whole that its quality in terms of the

degree of effective collaboration can provide a good

performance indicator of the success of an organisation,

in terms of customer satisfaction and external negotiations

[e.g., 5]. IT undoubtedly now forms an integral part of

any given organisation on which business decisions and

strategies are enabled, often at hugely elevated investment

costs which often fail to provide tangible benefits to the

business in practice [6]. It is this shortfall that requires

renewed research efforts and which this study attempts to

address through an evaluation of some of the reasons for

why this occurs, in the context of the BIT relationship.

A large body of work has shown that the BIT

relationship has continually failed to act synergistically,

commonly depicted in the literature through the concept

of ‘alignment’ [e.g., 7]. However, the alignment

paradigm has dissatisfied some by inferring that

organisational business affairs can be merely

‘straightened up’ as one side of the business catches up

with the other [see 8]. In contrast, Smaczny [9] has taken

the middle ground in offering the concept of ‘fusion’,

where BIT strategies are developed and implemented

simultaneously as part of a more collaborative enterprise

in sharing perspectives. Alternative studies have

completely dispensed with the notion of alignment

altogether and taken a more sceptical view in looking to

the real-life separation of BIT activities. This body of

work points to a more fractured view of the BIT

relationship as a clear divide that needs to be bridged,

reflected most strongly in recent times with a whole series

of ‘gap’ type articles in the literature [e.g., 10].

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 1

In this study, FinCo has followed this tendency to

separate BIT activities, implicitly creating a ‘barrier,

which has now emerged as an area of organisational

concern, given its perceived negative effects on

organisational dialogue and collaboration [11]. A

common contributory factor to the problems that BIT

face, is poor communication. It has been found to blight

interactions between IT specialists and financial product

managers [e.g., 12] as well as in general adversely

affecting the integration of business and IT strategy [13],

where communication is seen as a critical component of

collaboration [14, 15]. Therefore, this paper will argue

that in order for people to co-operate to achieve a goal

(i.e., collaborate) they must be able to engage effectively

in a process of creating a shared understanding of

messages between senders and receivers (i.e.

communicate). In this vein, RM has emerged as a method

to facilitate collaboration.

Indeed, the practice of management can be seen as the

craft of creating a strategic vision to enhance

organisational effectiveness [16]. Increasingly then this

vision has been seen to encompass a more relational view

of organisations in terms of a network of interdependent

relationships in which communication is crucial for the

flow of messages between people and the organisation at

large [17]. RM then permits the creation and maintenance

of business and personal relationships with other diverse

members of the organisation in an effort to ‘flatten’ the

communication process into a more communication

friendly horizontal structure. Such a structure to

communication enforces the notion of integration and

thus collaboration, as it contends that however specialised

particular departments may be within an organisation, co-

ordination with other departments in different areas of

expertise is necessary in order to make the organisation

more seamless and avoid the pitfalls of a BIT divide.

The post of a relationship manager then bestows a

distinctive status upon the individual, which has been

given scant attention in the literature [but see 18]. The

central thesis of this paper therefore is that the notion of

communication provides a useful lens through which to

view the BIT relationship and survey its collaboration

potential, especially since communication features heavily

in the creation, development and destruction of

relationships [19]. The components of communication

which will be addressed here (see Section 2) can be better

understood in collaborative terms as ‘activity links’ [20],

which views relationships as a chain of communication,

where breaks in the relationship, through conflict for

example, will disrupt collaboration detrimentally.

Therefore in order to address the various

communication issues that a study of the BIT relationship

presents, the paper is divided into a further five sections.

Section 2 presents a four-dimensional framework

employed as a tool for analysis. Section 3 outlines the

research method, case background to FinCo, data

collection and analysis. Section 4 displays the results of

the thematic content analysis. Section 5 discusses the

implications of the study and Section 6 concludes the

findings, with the insights gained from the study of

managing relationships.

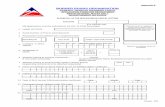

2. PICTURE: A framework for the effective

communication of requirements

A four-dimensional framework (PICTURE) was

applied in this study, which was developed from a

synthesis of the relevant literature in order to present a

structured approach to categorising complex

communication issues — a viable approach for

highlighting the multi-faceted nature to collaboration

[e.g., 21]. PICTURE was originally devised for the

micro-level analysis of small group and interpersonal

contexts of communication within requirements

elicitation for the design of systems and how it could be

improved [22]. The study reported here however, looks at

the communication of requirements, in terms of the

messages that are exchanged, on a much broader level of

analysis, in the wider context of the organisation,

particularly the BIT relationship. It is posited that the

framework is equally applicable on a higher level of

abstraction as the communication studied in both contexts

revolves around the creation and shared understanding of

requirements (or messages) between stakeholders who are

broadly defined as being business or technically based.

The framework is referred to by the acronym

PICTURE which makes reference to both the four

dimensions of the framework (numbered 1-4) and its area

of applicability (requirements elicitation) and can be

described thus: (1) Participation and selection; (2)

Interaction; (3) Communication activities; (4)

Techniques; Used for Requirements Elicitation. Figure 1

provides a graphical representation of PICTURE along its

numbered dimensions, sub-categories (explained in

Sections 2.1-2.4) and associated themes revealed by the

analysis (see Section 4), although some sub-categories

remained unpopulated by themes as little or no reference

was made to them from the analysis. PICTURE’s

structure has been constructed with reference to a classic

model of communication by Shannon and Weaver [23].

The description of each dimension in Figure 1 highlights

the core communication components (capitalised) that the

Shannon-Weaver model emphasises and which underlie

most models of communication.

However, the work reported on here, transforms this

early (and linear) model considerably. PICTURE

promotes a more dynamic and encompassing view of

communication as a process that occurs within a group of

stakeholders, which in this instance are directors and

managers from two sides of an organisation (business and

IT) and subject to several defining influences. For

example, a message may be competently delivered by a

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 2

knowledgeable stakeholder (see dimension 1), but the

culture of an organisation (see dimension 2) in which the

stakeholder resides can further shape the delivery of a

message. The negotiation activities undertaken by the

receiver of the message (see dimension 3), may be more

or less successful in breaking down the message in

creating a mutual understanding, which again can depend

upon the written/verbal medium (see dimension 4) used to

convey the message. Also, previously unconsidered by

the Shannon-Weaver Model was the concept of

‘feedback’, which is seen as an important mechanism in

collaborative terms for checking understanding and

maintaining the flow of communication. Each of the

dimensions and their purposes are briefly explained in

Sections 2.1-2.4.

2.1 Choosing collaborators: Participation and

Selection dimension

A business stakeholder is a type of person or group of

persons who represents the source of information (or

message), which they will strive to share and negotiate

knowledge with other parties. However, a stakeholder

can also be seen as the destination of messages as well as

the original source, which holds true if the concept of

feedback is considered. Choosing appropriate BIT

representatives is vital for having a team that can

collaborate successfully [24]. Identifying suitable

candidates highlights the importance of having a

transparent organisational structure. Interfaces within and

between divisional departments need to be clear so that

networking can occur for the appropriate exchange of

stakeholder views.

Macaulay [25] however, usefully identifies a

hypothetical group of stakeholders that can be categorised

into at least three different types, presented here with a

short description:

1. Task knowledge and skill – domain knowledge.

2. Status – high-low ranking managers with decision-

making powers.

3. Responsibility – technical implementers and financial

accountants.

One example of a type of stakeholder represented in

this work is the ‘relationship manager’. The relationship

Figure 1. The PICTURE framework

1.

Participation

and

Selection

3.

Communication

Activi ties

Description: The choice of

stakeholders and how these

represent both an INFORMATION

SOURCE and a DESTINATION

for messages.

Sub-category - themes:

Task knowledge and skill – BIT

experience

Status

Responsibility

2.

Interaction

4.

Techniques

Description: The way in which

messages are ENCODED before

they are sent.

Sub-category - themes:

Culture and politics –

Organisational structure, Location

of IT division, BIT camps.

Management style – Clarity and

understanding

Description: The CHANNEL

through which the message is

conveyed.

Sub-category - themes:

Spoken – Meetings

Text -based

Description: Communication

activities – refers to the way that

messages are DECODED when

they are received.

Sub-category - themes:

Knowledge acquisition – Gaps in

understanding

Knowledge negotiation –

Informat ion exchange, Customer

contact

Knowledge integration

Communication

within the BIT

relationship

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 3

manager’s remit is to provide both an understanding of

the technology side and the business interests that they are

meant to serve; a co-ordination task that in practice is

highly demanding from a communication standpoint in

juggling these concerns. This exemplifies the acute

difficulties of sharing information with a wide variety of

people, through interactions that are additionally subject

to a number of mediating influences, discussed next.

2.2 Attending to organisational influences:

Interaction dimension

Before they are sent, stakeholders formulate messages

by way of a transmitter (or an encoder), which in this

instance is seen as the interaction between a number of

mediating factors that influence the delivery of messages.

Organisational life in general is replete with a wide range

of features that are manifest in any given organisation

[26]. These features can be seen as elements (or sub-

structures) of the overall structure of an organisation as

typified by organisational charts, illustrating functional

relationships, which give little indication of the way that

these structures link and co-ordinate with each other and

across boundaries in reality.

The most interesting types of organisational structures

are more perceptual than physical and provide the broad

backdrop to the interactions between stakeholders on at

least two major levels, which comprise the sub-categories

for this dimension:

1. Culture and politics – Ting-Toomey [27] defined

organisational culture as the “complex frame of

reference that consists of patterns of traditions,

beliefs, values, norms, symbols and meanings that are

shared to varying degrees by interacting members of

a community” (p.10). From this definition comes the

notion that communication cannot be seen as a

separate entity from culture as each is produced from

the other as part of a highly dynamic relationship

[28]. The importance and pervasive nature of

organisational culture is reflected in studies that have

shown the cultural model has affected the messages

that are communicated [29], although the culture of

an organisation is rarely so uniform and is typically

composed of sub-cultures as exposed by the BIT

divide [see 30].

2. Management style – The adoption of a certain style to

management holds implications for communication

as ‘mediating posts’, where it can affect the quality of

interaction and thus the extent of the collaboration

[31]. The style that a business/IT/relationship

manager adopts to communicate (e.g., director or

relater) determines the way that information is

exchanged, although the links between (culturally-

influenced) management style and communication,

are complex [see 32]. Suffice to say that the type of

management style is a major component of the

communication process, in creating an atmosphere, in

which communication is encouraged among

stakeholders the exact nature of which is explained by

the next dimension.

2.3 Building working relationships:

Communication activities dimension

Encoded messages require decoding by the receiver.

In this instance it is the communication activities and the

particular behaviours that stakeholders engage in that

serve to break down the messages in order to create a

mutual understanding. The communication activities that

are undertaken by the management echelons of an

organisation have a bearing on the degree, structure and

quality of communication between organisational

members. Indeed, communication is a key activity of

managers so much so that communication is considered as

actually being the work of managers [33], although it is

apparent that the particular nature of the communication

activities should be structured in a way that promotes

effective communication.

A useful way of categorising these activities is

through the behaviours that are exhibited. Walz [34] have

identified three different behaviours of a communication

activity revolving around:

1. Knowledge acquisition – establishing links between

various stakeholders’ realms of knowledge and

experience and of the technological options.

2. Knowledge negotiation – sharing multiple

stakeholder perspectives and reaching a collective

understanding.

3. Knowledge integration – acceptance of the

strategy/system where successful collaboration

implies that stakeholders will be satisfied that it will

work within the limitations imposed.

In the banking industry, the success of these activities is

paramount in order to rapidly launch new products to

meet market demands [35]. Although, this success can be

more easily facilitated with the selection of suitable

techniques, discussed next.

2.4 Utilising a range of communication media:

Techniques dimension

A variety of techniques or media can be employed to

channel communication, which can be both verbal and

non-verbal. These techniques can be categorized into

different forms to convey an array of organisational

messages to meet certain communication goals that the

sender intends [36]. Selecting the most appropriate media

for conveying messages is of the utmost importance in

terms of the functions that can be achieved by the content

and form of the messages that are sent out. For example,

certain techniques (according to media richness theory)

have been shown to be more ‘rich’ than others in readily

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 4

lending themselves to obtaining timely feedback,

reducing uncertainty, resolving differences in opinion and

achieving understanding to name but a few possible

communication outcomes [see 37].

It is beyond the scope to enter into a discussion of the

richness of particular techniques at this stage but suffice

to say, the various techniques can be categorised in two

broad ways (spoken or text-based) with particular

techniques stated in order of richness [see 38]:

1. Spoken – Meetings (informal/formal/conferences);

Telephone; Video (phone/conferencing).

2. Text-based – Email; Memos, letters and faxes;

Company newspaper, bulletin board, policy manuals,

posters, and intranet.

Therefore, media richness theory would suggest that any

media involving face-to-face discussion (e.g., meetings)

will be richer than written communications (e.g., e-mail),

which decrease the opportunities for interaction, although

this view has its critics, given that the full range of

benefits of computer-mediated communications, such as

e-mail, may be more far-reaching than previously

assumed by media richness theory [see 39]. Nevertheless,

there is an imperative to educate managers as to the

suitability of certain techniques to achieve the desired

outcomes, in this case increased collaboration, which

PICTURE attempts to highlight.

3. Research method

A common approach to unpacking the complexity of

the issues involved in communication and collaboration is

to undertake an interpretative case study such as this one,

which fits with other studies focused on the meaning of

relationships in business [e.g., 40]. Such an approach

affords an in-depth look at a dynamic process such as

communication in terms of the shared meanings and

experiences of the people involved [41], and becomes

instrumental in making explicit the links between

antecedents and outcomes of contextual conditions upon

communication [42]. These are interpreted from the

perspectives of the individuals themselves, given that

multiple realities exist in this organisation (broadly

business and IT), which have been shaped by their

communication experiences.

3.1. FinCo: A case study

The organisation in the study, FinCo, a major high

street bank, was deemed a suitable case as it was at the

early stages of implementing a RM programme, which

comprised the company’s response to improving

relations, communication and collaboration between BIT.

Furthermore, these efforts were being conducted across a

perceived divide, which was held to be significant in

inhibiting the communication of messages between the

retail business and their counterparts in IT. Furthermore,

this study made use of a free data set in the sense that the

interview questions posed were not directly related to the

framework as in previous work [see 22]. This study was

designed to be both sensitive to FinCo’s environment and

conduct more of a test of PICTURE, which despite being

applied to a single case holds considerable value to other

companies in the assessment of the levels and quality of

communication in the organisation in accordance with

each of its four dimensions.

In considering the divide, the focus of the study was

directed at two key areas of the organisation — retail

business and IT. Retail banking was specifically chosen

as some research suggests that it is here that

organisational divisions appear more pronounced [e.g.,

43] and because it is the biggest ‘customer’ of the IT part

of the organisation. The two opposing areas of business

(retail) and IT can be described as follows:

1. Retail banking – covers services such as current

accounts, credit cards, share dealing etc. The retail

business division is comprised of different and often

competitive units (e.g., customer service, retail sales)

and is relatively distributed, although with an obvious

hierarchy of a tiered directorate down to management

levels (similar to the IT division);

2. IT – caters for solutions delivery, infrastructure and

architectures and support, for example, but is

relatively (and recently) centralised. The IT division

in organised into ‘silos’, where departments are

divided into separate lanes and where adjacent lanes

do not necessarily have as much contact and

communication as might be expected.

3.2. Data collection

In total, 29 semi-structured interviews each lasting an

hour were conducted with directors, heads of departments

and managers from both retail banking and IT. The

collection of data from at least three different

management levels permits the elicitation of multiple

viewpoints from individuals within the same departmental

division to be contrasted across divisions so as to identify

common themes that represent key concerns for BIT.

Eight interview questions were prepared, designed to

probe for experiences, thoughts and opinions relating to

three broad areas: (i) General background/BIT interaction

scenarios; (ii) Intent for enhancing the BIT relationship;

and (iii) RM as a viable solution for improving the BIT

relationship (see Appendix 1 for the interview schedule

used). Data collected from questions relating to areas 1)

and 2) are presented in Section 4, and data collected from

questions relating to area 3) presented in Section 4.1.

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 5

Table 1. Dimensional themes relating to BIT perceptions of a divide

REPRESENTATIVE QUOTE

DIMENSIONAL

CATEGORY

THEME RETAIL BUSINESS IT

DIMENSION 1: PARTICIPATION AND SELECTION

Tas

k

kno

wle

dg

e

and

sk

ill

BIT

exp

erie

nce

“The main problem as I see it is finding the right people for the job, but you know IT just don’t have the

resources” (Director, Retail Finance)

“I think strongly, the right people should take lead roles according to specialisms” (Manager, Group

Project Management)

DIMENSION 2: INTERACTION

Org

anis

atio

nal

stru

ctu

re

“The difference is that IT are very product related and

expertise is concentrated in a small group” (Head of

Customer Service)

“It is quite silo orientated around here, but it is Retail

that supports the layers of responsibility, and well it

can be a barrier” (Director, Group Technology Architectures and Support)

Lo

cati

on

of

IT d

ivis

ion

“IT people don’t move around, they just sit in X, and

wait to be told what needs to be done” (Manager, Group Development)

“I do feel like we are far away from the business and

so co-location is definitely something to be encouraged” (Manager, Data Centre Operations)

Cult

ure

and

po

liti

cs

BIT

cam

ps

“You see the people over in [IT] are of the mindset that

avoids a one-team attitude, by saying such things as the business wants this, as if they are not part of the

business” (Manager Information Management

Programme)

“I think X lacks something of a one team culture

really and part of it is because the business see us as some sort of add-on” (Manager, Retail Channel and

Operations Development)

Man

agem

ent

Sty

le

Cla

rity

and

und

erst

andin

g “To be honest, and this might sound a bit strange, I

really don’t know who to talk to over in [IT], I mean

some of the functions that these departments are meant to perform are quite lost on me” (Director, Retail

banking)

“I can give you an example of when it is really

important to have to talk to someone over in business,

when a system breaks down, say in the branches, and I for one have had difficulty in the past in knowing

and locating my opposite number in the business”

(Director, Retail Customer Risk and Decisioning)

DIMENSION 3: COMMUNICATION ACTIVITIES

Kn

ow

led

ge

acquis

itio

n

Gap

s in

und

erst

andin

g “I’d be the first to admit that I do not understand some

of the technicalities of our systems although I have signed off documents from IT and therefore given a

blanket acceptance of stuff I actually know little about,

with I have to say no help from the IT guys” (Head of Relationship Management Lending)

“To be perfectly honest, I think that as a division we

may perhaps lack the necessary knowledge of business requirements and objectives, but having said

that the business have to take some responsibility in

understanding how their requirements will pan out in terms of time and cost” (Systems Manager)

Info

rmat

ion

exch

ang

e

“Communication with other parts of the organisation, namely IT appears to be blocked at times for want of a

better term, you know, for example, business people

are rarely asked to talk at IT conferences so obviously we lose out on that important mixing element”

(Director, Retail Programme)

“Most of the time many of our messages don’t get through to business or they get through and are

confused and then you find yourself in the situation

where systems problems are fixed without discussion of the issues with the business” (Director, Solutions

Delivery)

Kn

ow

led

ge

neg

oti

atio

n

Cu

stom

er

con

tact

“You know I get the distinct impression sometimes in some of my dealings with the IT people that they don’t

see that they are in fact working towards delivering to a

customer” (Managing director, Retail Finance)

“I do hear of complaints now and again mainly from the business, that we are out of touch with the man on

the street as it were, you know the end users of some

of our systems, but the reality is as a department we receive very little feedback on the customer

experience” (Director, Group Technology Services)

DIMENSION 4: TECHNIQUES

Sp

ok

en

Mee

ting

s

“Meetings tend to be totally ad hoc here, I mean it makes me wonder if some of these people are meant to

be involved in these forums as they appear to have

been selected from a quick flick of the internal telephone directory” (Director, Retail banking)

“We do have regular meetings which is an excellent way of exchanging ideas, but on the whole there is a

severe lack of mixing and talking with people

generally” (Manager Supply Management)

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 6

3.3. Data analysis

The transcribed interview data was analysed for its

thematic content, which involved identification of a

number of themes. These were subsequently assigned to

the four dimensional categories of PICTURE, to provide a

narrative on the BIT relationship, a tried and tested

approach in a number of studies seeking to substantiate a

structure to an investigative framework [44]. The themes

were generated following a systematic and manual coding

procedure in four clear steps [see 45]:

1. Unit of analysis – the complete concept of a

respondent’s utterance, typically ranging from a few

words to an entire paragraph to which codes were

attached.

2. Code attachment – act as labels on the units of

analysis and represent the theme prevalent in that

section of text.

3. Theme categorisation – the identified themes are then

assigned to the predefined dimensional categories of

PICTURE.

In total, nine broad themes were identified from the

analysis. In the interests of brevity, the presentation of

the vast amount of data has been condensed to the display

in Table 1. A representative quote to illustrate the context

of each theme is provided from both the retail business

and IT, in order to give an indication of the conflicting

nature of the stance taken from these two sides of the

organisation. Without the luxury of entering into an in-

depth analysis of these themes, discussion will be directed

in the next section on the key notes of interest highlighted

by Table 1.

4. Perceptions of a BIT divide

The themes surrounding dimension 2: interaction,

especially within the category of culture and politics,

were more numerous than in other categories. This

demonstrates that this aspect of organisational life

appeared to cause the most concern for FinCo employees

and where the BIT divide was most clearly in evidence.

Also of note were themes associated with the category

of knowledge negotiation (dimension 3: communication

activities), where two key themes emerged (information

exchange and customer contact). Here, it was revealed

that opportunities within the organisation to communicate

had practically degenerated with dangerous repercussions

being felt in another crucial relationship — the customer

outside of the organisation. However, while conflict

prevailed in BIT, there was also a fair degree of

agreement between the two sides in the sense that their

perceptions on certain issues would occasionally be

matched (e.g., on theme: BIT experience and ‘finding the

right people for the job’) although they lacked the means

to resolve these issues.

Overall however, the dimensional categories and

associated themes cannot be viewed in isolation. In

practical terms, the PICTURE framework has usefully

highlighted that the dimensional categories and themes

impact upon each other in ways that require urgent and

further attention, but ultimately contribute to an

organisational communication problem and thus an

inhibitor for effective collaboration. This in turn has

considerable implications for anyone undertaking the role

of RM, who given the analysis provided above, may have

a serious problem co-ordinating large scale BIT activities

for example, in such a communication minefield. Until

the time of the study, FinCo itself had not formally

conducted an assessment of their communication needs.

Nevertheless, they were acutely aware that a problem

existed between BIT, though without qualifying its

nature, and hence the instigation of the RM programme to

combat the BIT communication divide. However,

respondents when questioned on the efficacy of such an

initiative revealed many misgivings of its potential

success, of which the findings are summarised in the next

section.

4.2 Perceptions of the efficacy of relationship

management

The data presented here is in its preliminary stages, as the

interview questions pertaining to the efficacy of an RM

programme sought merely to gauge briefly the level of

understanding of the term ‘relationship management’ and

whether it would improve BIT relations. At the time of

the study, the organisation was undergoing restructuring

to accommodate the role of designated relationship

managers, so thoughts and opinions were therefore

canvassed at a very early stage of this upheaval. The

questions were posed with a view to assessing how well

the notion of RM had been relayed to the workforce in the

context of the unique problems FinCo faced and

subsequently how these opinions would change (if at all)

in follow-up studies.

The issues that were uncovered in relation to the RM

programme were assigned to the relevant themes

identified from the first part of the study (see Table 1), in

order to expand them further in terms of relating this

knowledge to perceptions of RM. In light of the fact that

the RM programme was in its infancy, many of the

interviewees expressed views both for and against RM as

they attempted to make sense of the value RM could

impart for them both as an individual and member of their

department and their division. This process generated 30

individual issues presented in Table 2, further categorised

into whether they were positively or negatively expressed

in order to give a finer impression of the some of the

confused debate over the efficacy of RM.

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 7

Table 2. Dimensional themes relating to the efficacy of RM

BUSINESS-IT PERCEPTIONS

THEME Positive Negative

BIT experience

Get right people together Forward-looking

Mobilising resources

Dilution of expertise Resourcing relationship

Organisational

structure One point of contact

Creation of vertical RM organisations Another unnecessary boss

BIT camps

Interface between BIT

Act as conduit Repairing relations

Change agent

Bridging not closing gap

Artificial division Passivity and reactivity

Breaking existing good links

Selling and dictating

Clarity and

understanding

Provide holistic view Enable understanding

Needs constant information and updating

Gaps in

understanding

Repository of knowledge

Detailed understanding of requirements Internal tensions over remit of role

Information

exchange

Communicate requirements clearly

Raise awareness

Manage communication links Building trust in relations

Act as a barrier to lower levels

Could add cost but no value

Remaining unbiased

Table 2 reveals perceptions of RM that are almost

equally positive, as they are negative, indicating a great

deal of trepidation from FinCo employees as to the actual

benefits that RM will hold in practice. To provide some

context to these misgivings it was felt, for example, in

some quarters of the organisation that RM wasn’t such a

new thing after all in that “several people [have] already

been a relationship manager for some time now despite

not being officially titled!” (Director, IT and

Infrastructure). How the officially appointed relationship

managers would fit into the existing organisational

structure is yet to be seen, but it would appear that the

management of relationships is of major concern within

this organisation in terms of increasing collaboration

through effective communication means.

However, it does not necessarily have to be the formal

programme along the route that FinCo is embarking upon,

especially when the understanding of the present

relationships as PICTURE has uncovered is not clear.

Rather, each of the dimensions of PICTURE pinpoints the

particular problem areas that this organisation needs to

attend to, that are affecting the BIT relationship

negatively and which a formal RM programme could

complicate yet further.

5. Implications of the study

The potential of the PICTURE framework as an

organisational tool for diagnosing communication

problems within the BIT relationship is still in its infancy

and future work is needed to focus on the nature of the

communication problems in modern organisations and

how they can be resolved in order to pave the way for

collaborative activities. Following from this, the main

findings of the paper can be summarised in four main

ways:

1. Demystifying communication – deconstructing the

nature of communication by breaking it down into its

constituent parts (dimensions, sub-categories, themes)

reveals how the communication process works in the

day-to-day life of a real organisation and the impact

that this has on the way stakeholders collaborate.

2. Exposing relationships - a focus on relationships as

intricate collaboration links serves to explode a

number of myths about the existence and

maintenance of relationships in organisations. A

business stakeholder is related to an IT stakeholder as

an opposite number in an organisation, but in FinCo

this tended to be in a purely associative rather than

cohesive sense. Relationships were exposed to be in

fact quite weak, in terms of the number of

communication problems that were experienced, as

documented by the thematic analysis.

3. Assessing RM as a collaborative tool - the instigation

of a RM programme is questionable given the nature

of the problems FinCo faced. The success of such

popular RM programmes in general could be

negligible, without first attempting some type of audit

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 8

of communication and collaboration processes within

an organisation to spotlight problem areas and

provide solutions before restructuring management.

4. Structuring an approach to the study of

communication – the complex nature of relationships

and their attendant issues such as communication are

difficult to investigate, but a framework such as

PICTURE can pinpoint the relevant issues and

present them in a digestible form for a diverse range

of people (e.g., business and IT) to understand

clearly.

The use and implementation of a framework such as

PICTURE can set the agenda for change. Specifically, in

order for the shift towards the collaborative organisation

to begin, a firm needs to attend to the way that their

relationships are managed, and a useful starting-point may

be found in at least four key areas as prescribed by

PICTURE.

6. Conclusions

This study has offered some fresh insights into the

management of relationships within organisations.

However, maintaining the delicate balance of

collaboration within large organisations is a huge

challenge, which a programme such as RM can promise

and deliver on, but not necessarily as an overlaid or

inserted organisational layer as FinCo has attempted.

Investing in relationships is critical to building

collaboration within the organisation. However, it needs

to permeate organisation-wide so that the life and value of

these connections can be substantiated whilst

simultaneously becoming more fluid in dissolving the

many barriers (primarily communication), which can halt

or hinder collaborative activities. PICTURE therefore,

endeavours to provide a snapshot of the state of

communication within an organisation by unveiling the

workings of a relationship, and thus providing a sound

platform for the creation of more fruitful collaborative

activities.

References

[1] K. Eriksson and J. Mattsson, "Managers' perception of

relationship management in heterogeneous markets," Industrial

Marketing Management, vol. 31, pp. 535-543, 2002.

[2] D. A. Griffith, "The role of communication competencies

in international business relationship development," Journal of

World Business, vol. 37, pp. 256-265, 2002.

[3] S. Dibb and M. Meadows, "The application of a

relationship marketing perspective in retail banking," The

Services Industries Journal, vol. 21, pp. 169-194, 2001.

[4] J. Kuljis, R. D. Macredie, and R. J. Paul, "Information

gathering problems in multinational banking," Journal of

Strategic Information Systems, vol. 7, pp. 233-245, 1998.

[5] J. Peppard and J. Ward, "'Mind the gap': Diagnosing the

relationship between the IT organisation and the rest of the

business," Journal of Strategic Information Systems, vol. 8, pp.

29-60, 1999.

[6] C. M. Hinton and G. R. Kaye, "The hidden investments in

information technology: The role of organisational context and

system dependency," International Journal of Information

Management, vol. 16, pp. 413-427, 1996.

[7] J. C. Henderson and N. Venkatraman, "Strategic alignment:

Leveraging information technology for transforming

organizations," IBM Systems Journal, vol. 32, pp. 4-16, 1993.

[8] C. Sauer and P. W. Yetton, Steps to the Future: Fresh

Thinking on the Management of IT-based Organisational

Transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1997.

[9] T. Smaczny, "Is an alignment between business and

information technology the appropriate paradigm to manage IT

in today's organisations?," Management Decision, vol. 39, pp.

797-802, 2001.

[10] J. Peppard, "Bridging the gap between the IS organisation

and the rest of the business: Plotting a route," Information

Systems Journal, vol. 11, pp. 249-270, 2001.

[11] A. Holmes, Failsafe IS Project Delivery. Aldershot:

Gower, 2001.

[12] P. Vermeulen and B. Dankbaar, "The organisation of

product innovation in the financial sector," The Services

Industries Journal, vol. 22, pp. 77-98, 2002.

[13] B. H. Reich and I. Benbasat, "Factors that influence the

social dimension of alignment between business and information

technology objectives," MIS Quarterly, vol. 24, pp. 81-113,

2000.

[14] J. E. Austin, The Collaboration Challenge: How Nonprofits

and Businesses Succeed through Strategic Alliances. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2000.

[15] R. C.-W. Kwok, M. Lee, and E. Turban, "On inter-

organizational EC collaboration: The impact of inter-cultural

communication apprehension," presented at Proceedings of the

34th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

2001.

[16] D. Tourish and O. Hargie, "Communication and

organisational success," in Handbook of Communication Audits

for Organisations, D. Tourish, Ed. London: Routledge, 2000,

pp. 3-21.

[17] G. M. Goldhaber, Organizational Communication, 6th ed.

Dubuque, IA: Brown, 1993.

[18] C. S. Iacono, M. Subramani, and J. C. Henderson,

"Entrepreneur or intermediary: The nature of the relationship

manager's job," presented at Proceedings of the 16th

International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS'95),

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995.

[19] S. Duck, Relating to Others, 2nd ed. Buckingham;

Philadelphia: Open University Press, 1999.

[20] A. Dubois and H. Håkansson, "Relationships as activity

links," in The Formation of Organizational Networks, M. Ebers,

Ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

[21] S. Horrocks, N. Rahmati, and T. Robbins-Jones, "The

development and use of a framework for categorising acts of

collaborative work," presented at Proceedings of the 33rd

Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

1999.

[22] J. Coughlan, M. Lycett, and R. D. Macredie,

"Communication issues in requirements elicitation: A content

analysis of stakeholder experiences," Information and Software

Technology, vol. 45, pp. 525-537, 2003.

[23] C. Shannon and W. Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of

Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1949.

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 9

[24] G. Klein, J. J. Jiang, and D. B. Tesch, "Wanted: Project

teams with a blend of IS professional orientations,"

Communications of the ACM, vol. 45, pp. 81-87, 2002.

[25] L. Macaulay, "Requirements capture as a cooperative

activity," presented at Proceedings of the 1st IEEE International

Symposium on Requirements Engineering (RE'93), San Diego,

CA, USA, 1993.

[26] A. M. Pettigrew, "Conclusion: Organizational climate and

culture: Two constructs in search of a role," in Organizational

Climate and Culture, B. Schneider, Ed. San Francisco: Jossey-

Bass, 1990, pp. 413-441.

[27] S. Ting-Toomey, Communicating Across Cultures. New

York: The Guilford Press, 1999.

[28] T. Schirato and S. Yell, Communication and Culture: An

Introduction. London: Sage, 2000.

[29] A. M. Wilson, "Understanding organisational culture and

the implications for corporate marketing," European Journal of

Marketing, vol. 35, pp. 353-367, 2001.

[30] D. M. Rousseau, "Assessing organizational culture: The

case for multiple methods," in Organizational Climate and

Culture, B. Schneider, Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass,

1990, pp. 153-192.

[31] D. H. Sonnenwald, "Communication roles that support

collaboration during the design process," Design Studies, vol.

17, pp. 277-301, 1996.

[32] J. R. Darling and A. K. Fischer, "Developing the

management leadership team in a multinational enterprise,"

European Business Review, vol. 98, pp. 100-108., 1998.

[33] H. Mintzberg, Mintzberg on Management: Inside our

Strange World of Organizations. New York: The Free Press,

1989.

[34] D. B. Walz, J. J. Elam, and B. Curtis, "Inside a software

design team: Knowledge acquisition, sharing, and integration,"

Communications of the ACM, vol. 36, pp. 63-77, 1993.

[35] D. Wilson, "Diagonal communication links within

organizations," The Journal of Business Communication, vol.

29, pp. 129-143, 1992.

[36] D. Te'eni, A. Sagie, D. G. Schwartz, N. Zaidman, and Y.

Amichai-Hamburger, "The process of organizational

communication: A model and field study," IEEE Transactions

on Professional Communication, vol. 44, pp. 6-20, 2001.

[37] R. L. Daft and R. H. Lengel, "Information richness: A new

approach to managerial behaviour and organization design," in

Research in Organizational Behaviour, vol. 6, B. M. Staw, Ed.

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1984, pp. 191-233.

[38] R. L. Daft and G. P. Huber, "How organizations learn: A

communication framework," in Research in Sociology of

Organizations, vol. 5, N. Tomasso, Ed. Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press, 1986, pp. 1-36.

[39] O. K. Ngwenyama and A. S. Lee, "Communication

richness in electronic mail: Critical social theory and the

contextuality of meaning," MIS Quarterly, vol. 21, pp. 145-167,

1997.

[40] T. Fuller and J. Lewis, " 'Relationships mean everything'; A

typology of small-business relationship strategies in a reflexive

context," British Journal of Management, vol. 13, pp. 317-336,

2002.

[41] G. Walsham, "The emergence of interpretivism in IS

research," Information Systems Research, vol. 4, pp. 376-394,

1996.

[42] M. Janson, A. Brown, and T. Taillieu, "Colruyt: An

organization committed to communication," Information

Systems Journal, vol. 7, pp. 175-199, 1997.

[43] G. Koloszyc, "Retailers, suppliers push joint sales

forecasting," Stores, 1998.

[44] E. Longmate, P. Lynch, and C. Barber, "Informing the

design of an online financial advice system," presented at

Proceedings of the HCI'00 Conference on People and

Computers XIV, Sunderland, UK, 2000.

[45] I. Dey, Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide

for Social Scientists. London: Routledge, 1998.

Appendix 1. Interview schedule

Section A: General Background/ BIT interaction scenarios

1. Can you describe your department’s primary role(s) and

responsibilities within the organisation?

2. Which other functional units/departments does your

department interact with to fulfil these roles and

responsibilities?

PROMPT: How important is the relationship with IT and in

what ways?

3. Please describe typical scenarios of interaction with

business/IT units, highlighting any particularly good or bad

examples?

PROMPT: Purpose, effectiveness, formalities, frequency,

communication channels?

Section B: Intent for enhancing business-IT relationship

4. Given your knowledge of business/IT strategy/direction,

how do you see your relation with business/IT units

changing/transforming in the future?

PROMPT: Optimism or pessimism and why?

5. If you were granted three wishes to improve the

relationship between business and IT units, what changes

would you like to see within your relationships?

PROMPT: Expectations, intent to collaborate and requests?

6. What could you do to facilitate these changes and what

could others to do to facilitate these changes?

Section C: Relationship management solution option

7. What do you understand by the term ‘relationship

management’ and its role?

8. In what ways do you think ‘relationship management’

can/cannot improve the relationship between the business

and IT?

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 10