cornucopia non est nidhisrnga

Transcript of cornucopia non est nidhisrnga

Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

Adalbert J. Gail, Freie Universität Berlin

SUMMARY: Sanskrit nidhiś�ṅga is no equivalent of Latin cornucopia and does not denote a horn of plenty. The relevant passage of the Viṣṇudharmottara-Purāṇa (Vdh) speaks about objects that should and should not be painted in the houses of (normal) men.

Nidhiś�ṅgān grammatically refers to v�ṣān, and it means: (painted) bulls which have treas-ures (such as padma, śaṅkha etc.) on their horns.

In contrast to a fitting term in Indian languages the object in question, cornucopia, trav-elled from the Mediterranean World to Iran and India, where it found a proper place in the hands of Lakṣmī, goddess of prosperity.

In an article in the Bulletin of the Prince of Wales Museum (No. 9, 1964–66, pp. 1–33) Moti Chandra tried to convince the reader that the Indi-an equivalent of Latin cornucopia is the Sanskrit term nidhiś�ṅga handed down by the Viṣṇudharmottara-Purāṇa III, 62, 3. The following lines try to make clear that this attempt titled Nidhiś�ṅga (cornucopia): a Study in Symbolism altogether fails.

In the Metamorphoses of Ovid the horn of plenty is derived from the horn of a bull whose form the river-god Achelous adopted when fighting with Herakles. The hero-god tears out this horn, nymphs fill it with fruits and fragrant flowers and Achelous remarks that the goddess of plenty is rich by his horn (divesque meo Bona Copia cornu est (Met. IX 88).

This derivation of cornucopia to which Moti Chandra refers (p. 3) seems, however, to be secondary. The horn in question is in general regarded as the horn of the goat Amaltheia1 who nourished the newly born Zeus with her milk. Moreover, the Roman variant contains a difficulty. The rather short horn of a bull has a massive tip and is therefore not very suitable as

1 LIMC I 1, p. 582 s.v. Amaltheia: The horn of Amaltheia (cornucopia) was represented as having the power to provide all that anyone might desire to eat or to drink, and was sometimes equated with that horn which Herakles broke off from the brow of Achelous; I 2, p. 437 no. 3. Coin of Antoninus Pius (AD 138–161): Amaltheia with baby Zeus in her left arm, in her right arm is a cornucopia.

100 PANDANUS ’12/1

a drinking horn and, even less, as a horn of plenty (Fig. 1). Only artificial bull-horns made of clay or of metal were practicable. The pretty long horn of a goat is hollow (Fig. 2).

Moti Chandra takes two verses of the Viṣṇudharmottara-Purāṇa III, 43, 15–16 as the key text for an equivalent of Latin cornucopia and Sanskrit nidhiś�ṅga. Quite rightly he criticizes the translations by Stella Kramrisch and by Priyabala Shah. His own version, however, is not better. I quote Moti Chandra (1964–66, pp. 12f.):

One of the most important references to the cornucopia, however, appears in the follow-ing couplets in the Vishṇudharmottara Purāṇa: (note 36: Vishṇudharmottara, III, edited by Priyabala Shah, Baroda, 1950; 43, 15–16.)

nidhi-ś�ṅgān v�ṣān rājan nidhi-hastān mataṅgajān /nidhīn Vidyādharān rājan �ṣayo Garuḍas tathā // 15 //hanūmāṃś ca sumaṅgalyā ye ca loke prakīrtitāḥ /likhitavyā mahārāja g�heṣu satataṃ n�ṇām // 16 //

Dr. Stella Kramrisch has translated the couplets as follows: “……bulls with the horns (im-mersed) in the sea, and (men) with their hands sticking out of the sea (whilst their) body is bent (under water) …….. (oh) great king, the Vidyādharas, the nine gems, Garuḍa, Hanumān, all those who are celebrated as auspicious on the earth, should always be painted in the residential houses of men.” (note 37: Stella Kramrisch, The Vishṇudharmottara (Part III), Calcutta, 1928, pp. 60–61.)

Unfortunately, the translation hardly makes any sense. Yet Priyabala Shah's explanation does not improve the matter. She explains: “All those things which are regarded as auspi-cious by people such as bulls with Nidhi horns, elephants with Nidhi trunks, (nine) Nidhis, Vidyādharas, sages, Garuḍa and Hanumān should generally be shown in them.” (note 38: Vishṇudharmottara-Purāṇa, Third Khanda, Vol. II, Baroda, 1961, pp. 135–136.)

I have translated the couplets as follows: (note 39: Bulletin of the Prince of Wales Muse-um, No. 7, 1959–1962, p. 8.)

“O King, in the residences of men should always be painted the 'treasure horns' (nidhi-ś�ṅgān) of the bulls, the 'treasure handles' (nidhihastān) made of elephant tusks (mataṅgajān), the nidhis, the Vidyādharas, the R̥shis (siddhas), Garuḍa, the 'wide-jawed one (mask)' (hanūmān), the auspicious women (sumaṅgalyāḥ) and other auspicious symbols famous all over the world.”

The Vishṇudharmottara therefore leaves no doubt that in the Gupta period to which probably the text belongs, nidhiś�ṅga represented by the bull horn and the elephant tusk was a well-recognized motif associated with good luck and fortune.

101Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

Yet, many doubts remain, disregarding the basic mistakes of Chandra's translation. Although the Vdh text is defective, a better translation is pos-sible when we place the verses within the context of the whole chapter. It discusses the question as to which objects, connected with certain senti-ments (rasa), should be painted in particular rooms, and which ones should not be painted. I propose the following translation:

In council-halls, in the palace of kings all sentiments2 should be represented. With the excep-tion of a council-chamber of a king (sabhā) and with the exception of a temple (devaveśma) inauspicious (topics such as) battle, cremation-ground, pity, death, misery, mishap, despised matters should never be painted in rooms (13b-15).

(The artist should paint) bulls with treasures on their horns, O king, and trunks with treasures that come from elephants (nidhi-hastān mātaṅgajān).3

Treasure (nidhi), Vidyādharas (= flying genii), �ṣis, Garuḍa, Hanumat are those very aus-picious (topics), o great king, that are praised in the world. They should always be painted in houses of men. (The painter) himself should not execute a work of art in his own house, o king [probably in order to avoid envy etc.]. (16–17).

sabhā-veśmasu kartavyā rajñāṃ sarva-rasā g�he // 13 b //varjayitvā sabhāṃ rājño deva-veśma tathaiva ca //yuddha-śmaśāna-karuṇā-m�ta-duḥkhārta-kutsitān // 14 //amaṇgalyāṃś ca na likhet kadācid api veśmasu //nidhi-ś�ṅgān v�ṣān rājan nidhi-hastān mātaṇgajān4 // 15 //nidhir Vidyādharā rājan �ṣayo Garuḍas tathā //hanumāṃś ca sumaṅgalyā ye ca loke prakīrtitāḥ // 16 //likhitavyā mahāraja g�heṣu satataṃ n�ṇām //citra-karma na kartavyam ātmanā svag�he n�pa // 17 //

From the context it is perfectly evident that we are not dealing with hol-low horns filled with fruits and flowers – the meaning of the real cornuco-pia –, but with painted horns of bulls and painted trunks of elephants that

2 Vdh 43,1: ś�ṅgāra (love), hāsa (mirth), karuṇa (distress), vīra (heroism), raudra (fury), bībhatsā (disgust), adbhuta (wonder), śānta (peacefulness), are the nine sentiments im-parted by pictures (nava citrarasāḥ).

3 An easier reading would be just mātaṅgān since we could translate: ‘and elephants with trunks that carry treasures’.

4 Matāṅgajān of the Veṅkaṭeśvara edition makes no sense at all.

102 PANDANUS ’12/1

are embellished with a nidhi decor, i.e. probably with śaṅkha- and cakra-patterns, the most popular nidhis in Indian art (Mallmann 1963, p. 187). Although we do not have such paintings at our disposal from Ancient In-dia, the text does not allow any other interpretation. Since, moreover, this is the only Sanskrit text that uses the term nidhiś�ṅga, we can also be al-most sure that there is no linguistic equivalent in Sanskrit for keras Amal-theias or cornucopia.

On the other hand there can be no doubt that the object itself, the horn of plenty, reached Gandhara and the Kushan empire via Iran from the Mediterranean world (Rosenfield 1967, pp. 72–75). Ardochsho, Nanā and most probably Lakṣmī are equipped with cornucopiae.5

Much effort has been made to study the obverse types of Kuṣāṇa and Gupta coins including a female carrying a cornucopia in her left hand. According to the coin-inscriptions of the Kuṣāṇas – Kaniṣka, Huviṣka, Vāsudeva I and Kaṇiṣka II – the goddess is definitely Ardochsho, the Iranian “embodiment of the principle of abundance and prosperity” (Rosenfield 1967, p. 74, Coins 46, 80–82, Fig. 78; see below Fig. 3). In the same period statues of the Bud-dhist goddess Hāritī appear together with Pāñcika. As parents with chil-dren they are related to Ardochsho and Pharro, but Hāritī is not equipped with a horn of plenty (Fig. 4).

In the Gupta period, as pointed out by Ellen Raven (2010, pp. 259–261; cf. Fig. 5 below), we should identify the goddess with cornucopia as Lakṣmī, goddess of wealth and fortune, and the patroness and symbolic spouse of the Gupta kings according to Kālidāsa (Raghuvaṃśa I. 31f. tayā manasvinyā [scil. Sudakṣiṇyā] Lakṣmyā ca).6

5 Raven (2010, p. 259, fn. 5) remarks: “The cornucopia is one of he most conspicuous at-tributes shared by goddesses related to fortune, abundance and fertility in the Hellenized sculptural and numismatic arts of the crossroads of Asia area.”

6 Puzzling, however, is a coin of Samudragupta where the obverse side exhibits a god-dess seated on a lion and holding a fillet and cornucopia (Raven 2010, Fig. 21b). We do not expect the lion vehicle with Lakṣmī, but with Durgā. Nanā, a common type among Kuṣāṇa coins (Kaṇiṣka, Huviṣka, see Rosenfield 1967, 83–90) is used to sit on a lion. In the Gupta period, however, Nanā seems to have disappeared from the religious landscape in India.

103Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

Vasudhārā is the genuine heiress of Lakṣmī in the Buddhist Pantheon. The iconographical successor of the cornucopia seems to be the dhānyamañjarī (ear of corn, épi de riz) (Sādhanamālā 213f.) exhibited in the middle left hand of the six-armed Vasudhārā (Figs. 6–8). This variety of Vasudhārā was the most popular in Nepal. In India, during the Early Pāla period (9/10th century AD), Vasudhārā seems to carry some sort of straight pipe, perhaps the last (misconceived) remnant of the cornucopia (Fig. 9).

Postscriptum

After having finished this article my highly esteemed colleague Cinzia Pieruccini pointed my interest to two additional translations of the debat-ed passage of the Viṣṇudharmottara that I did not consult.

Mukherjee (2001, p. 245) simply changes the text by replacing nidhi by niḥ/nir. I quote:

“[Scenes such as] the representation of battles, funeral grounds, the tragic, death, pain, peo-ple tormented with grief and the villainous, bulls without horns (niḥś�ṅgān v�śān) and el-ephants without trunks (nirhastān mātaṅgajān) are regarded as inauspicious and they are not allowed to be painted in houses. They are only permitted in the royal assembly halls and the temples.”

This procedure, however, is philologically not justified since there is no manuscript the authority of which would be able to ignore nidhi as docu-mented in the printed editions.

Sivaramamurti (1978, p. 195) translates:

“Bull with horns holding treasure and elephants holding treasure pots in their trunks, the treasure themselves personified, …”

While “bull with horns holding treasure” is acceptable (see my transla-tion above), “elephants etc.” makes no sense. The treasures are, in Indian art, either depicted as (nine) pots (together with Kubera), or as the two (sometimes personified) nidhis, śaṅkha- and padma-nidhi. “Treasure pots

… the treasures themselves personified” are, to the best of my knowledge unknown in the visual arts.

104 PANDANUS ’12/1

A later chapter of the Viṣṇudharmottara that I checked only recently, con-firms my translation of the Vdh III, 43,15b (see above), but seems to specify the nidhi-hastān in such a way that the trunks of the (painted) elephants actually carry (painted) padmas and śaṅkhas in their trunks. Vdh III, 82 describes Lakṣmī, bathed by two elephants, a famous icon in Hindu, Bud-dhist and Jaina art. The verse 10 (identical in both editions) either identi-fies the two elephants with śaṅkha- and padma-nidhi (a) or – and that is evidently the same idea as in Vdh III,43,15b – puts the two nidhis, conch and lotus, into their trunks:

hasti-dvayaṃ vijānīhi śaṅkha-padmāv ubhau nidhī / (a)samutthitā vā kartavyā śaṅkhāmbuja-karā śubhā // (b)

References

Chandra, M., 1964–66, Nidhiś�ṅga (cornucopia): a Study in Symbolism. Bulletin of the Prince of Wales Museum, No. 9., Bombay, pp. 1–33.

Foucher, A., 1900, Étude sur l’Iconographie Bouddhique de L’Inde. Ernest Leroux, Paris.Kālidāsa, 1971, The Raghuvaṃśa of Kālidāsa. With the Commentary of Mallinātha. Ed.

G.R. Nandargikar. 4th ed., Motilal, Delhi-Patna-Varanasi.Kramrisch, S., 1928, The Vishṇudarmottara (Part III). Calcutta.LIMC 1981ff., Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. Artemis & Winkler, München.Luczanits, Ch., 2008, Gandhara uns seine Kunst. In: Gandhara – Das buddhistische Erbe

Pakistans. Legenden, Klöster und Paradiese. Ed. Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bun-desrepublik Deutschland GmbH. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz.

Mallmann, M.T. de, 1963, Les Enseignements iconographiques de L’Agni-Purana. Presses Uni-versitaires de France, Paris.

Mukherjee, P.D., 2001, The Citrasūtra of the Viṣṇudharmottara. Motilal Banarsi Das, New Delhi.

Publius Ovidius Naso, 1988, Metamorphosen. 11th ed. Artemis, München.Raven, E., 2010, The Seated Lady and the Gupta King. In: South Asian Archaeology 2007.

Proceedings of the 19th Meeting of the European Associateion of South Asian Archaeology in Ravenna, Italy, July 2007. Vol. II: Historic Periods. Ed. P. Callieri and L. Colliva. Ar-chaeopress, Oxford, pp. 259–273.

Rosenfield, J., 1967, The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press, Berke-ley and Los Angeles.

Shah, P., 1961, Viṣṇudharmottara-Purāṇa. Third Khanda, Vol. II. Gaekwad’s Oriental Se-ries, Baroda.

Sivaramamurti, C., 1978, Chitrasūtra of the Viṣṇudharmottara. Kanak Publications, New Delhi.

105Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

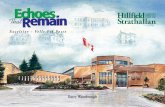

1. Bull, domain Dahlem, Berlin (Photo A.J. Gail)

2. Goat, domain Dahlem, Berlin (Photo A.J. Gail)

106 PANDANUS ’12/1

3. Ardochsho and Pharro, Gandhāra, ca. 2nd century AD (Photo Museum für Asiatische Kunst Berlin)

107Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

4. Hāritī and Pāñcika, Sahri Bahlol, Gandhāra, ca. 2nd century AD (Photo Luczanits 2008, p. 17)

108 PANDANUS ’12/1

5. Samudragupta and Lakṣmī , coin, middle of 4th century AD (Photo Raven 2010, Fig. 7)

6. Vasudhārā, Nepal, from Aṣṭasāhasrikā-Prajñāpāramitā ms., fol. 200 verso 1. Cambridge Add. 1643. 1015 AD (Photo University of Cambridge)

109Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

7. Vasudhārā, bronze from Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, 1644 AD (Photo A.J. Gail)

111Cornucopia non est nidhiś�ṅga

9. Vasudhārā, bronze from Kurkihar, Bihar, Indian Museum Kolkata, ca. 9th/10th century AD (Photo A.J. Gail)

Fontein, J., 2012, Entering the Dharmadhātu. A Study of the Gandavyūha Reliefs of Borobu-dur. Studies in Asian Art and Archaeology. Continuation of Studies in South Asian Culture, Vol. XXVI. Ed. by Marijke K. Klokke. Brill, Leiden – Boston, 257 pages, 41 figures; ISSN 1380-782X, ISBN 978-90-04-21122-3 (hardback), ISBN 978-90-04-22348-6 (e-book) – Re-viewed by Adalbert J. Gail, Freie Universität Berlin.

Forty-five years after the printed edition of his PhD thesis, the author comes back to his sources. In 1967 he published a study on The Pilgrimage of Sud-hana. The main result of this thesis was an important discovery. Formerly, the fact that only 45 visits of Sudhana to his kalyāṇamitras (good friends) are described, while 110 visits are mentioned and depicted, led to various explanations, including one which suggested the addition of meaningless scenes (p. 121). If the 20 reliefs that do not represent Sudhana in conver-sation with a teacher are withdrawn, the remaining 90 scenes constitute exactly the double amount of described visits. Fontein demonstrated that the authors of the reliefs showed Sudhana's visits twice, from the first vis-its up to the entrance into Maitreya' palace (II-126–128).

This understanding had been made difficult by the following fact:“In the first pilgrimage (II-16–II-72) the first half of Sudhana’s pilgrimage

was illustrated almost completely, followed by a more cursory treatment of the second half. In the second series (II-73–II-128) this imbalance was corrected by representing the second half of the visits more completely than the first” (p. 154).

In his thesis Fontein left aside Sudhana's encounter with Maitreya, Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra, depicted in the third and fourth gallery of the monument, expecting a critical edition of the relevant Sanskrit texts that would probably facilitate the interpretation of the reliefs. This, however, did not happen. Yet a meritorious German translation of the Gaṇḍavyūha by Torakazu Doi entitled Das Kegon Sutra appeared in Tokyo 1978. The au-thor did not use the opportunity to quote from this translation in connec-tion with the corresponding reliefs. For example: Maitreya invites Sudhana to step into his palace by snapping his fingers. This scene is depicted (III-4, Fig. 18) and accordingly translated from the original text: “Da schnippte Bodhisattva “Maitreya” mit den Fingern der rechten Hand, und das Tor des Palastes öffnete sich von selbst” (p. 434).

The new text, concerning Sudhana’s visits, is partly connected to Hikata’s

116 PANDANUS ’12/1

interpretations (Hikata 1960) and partly adds descriptions, where they were short or altogether missing in the edition of 1967.

The difference between Sudhana and the banker lies not only in the fact that they sit on different levels, but also the hand gestures vary (1967, p. 122, Pls. 50f.; 2012, p. 59, Fig. 14).

In the present study Fontein is able to show that the number of 110 vis-its (see above) forms part of the balanced design of the decor of the whole monument.

“The total numbers …amount to 220 for Maitreya, 110 for Samantabhadra and 5 for Mañjuśrī. Considering the scope and the complexity of his huge project, and the fact that, once it got underway, corrections probably could no longer be easily made, minor numerical discrepancies do not seem to be of crucial importance (Fontein 2012, p. 164).”

This balanced composition includes the narrative topics of the lowermost galleries: “…if we exclude the 500 panels of the first balustrade which are known to have been added later, the total number of panels illustrating avadānas and jātakas in the lower register of the main wall and on the bal-ustrade of the second gallery is also exactly 220” (ibid.).

The more astonishing is the fact that – as distinctly pointed out by the author – the relationship between textual material and depicted surface is very uneven. Sometimes the sculptors seem to combine much textual material into one relief, while at other times they are able to turn every word into an image. So it is not easy to understand that the two rounds of visits of 45 friends are narrated on 110 reliefs, while Sudhana’s sojourn in Maitreya’s palace, lacking any narrative colour, is honoured by 220 images. Here, a careful design cannot easily be demonstrated.

A further important question is by no means limited to Borobudur but concerns all depicted texts in South and Southeast Asia: how should we explain the many minor discrepancies between the texts known to us and the extant images?

To this question the author of the reviewed book devoted a seminal ar-ticle from which I would like to quote an important passage:

“Our interpretation of this literary evidence, chiselled in stone and frozen in time, is hampered by at least three obstacles. The first is our ignorance of

117Reviews and Reports

the physical condition, contents and textual affiliation of the written texts that guided the sculptors. As oral transmission is known to have played a key role in the spread of the literary themes throughout the subcontinent and the entire region of Southeast Asia, it is often taken for granted that it must also have influenced the visual representation of the stories. It may even account for some of the discrepancies between the written word and the sculpted or painted image” (Fontein 2000).

The importance of oral transmission, repeated by Fontein in this article several times, does not play the pivotal role that one would expect in his new study. Even minor discrepancies that could easily refer to differences between a written and an oral transmission are explained by missing texts rather than by the oral tradition of a story-telling society.

If a sculptor – to give an example – transfers a scene into a building that the text places instead in the landscape, the assumption that the story-teller or the craftsman did not remember this detail seems to be more plausible than a deliberate liberty on the part of the sculptor. The numerous minor deviations in the pictorial Lalitavistara in the first gallery, when compared with the (overwhelming) textual tradition, can best be explained in terms of deficiencies of memory.

The ideal researcher, according to Fontein, is a well-versed philologist and, at the same time, a trained art historian. The author himself widely fulfils these requirements, making it the more surprising that many San-skrit terms that were correctly transliterated in his thesis (1967), now ap-pear somehow distorted, i.e. without appropriate diacritical signs (correct is: kūṭāgāra, kalyāṇamitra, karmavibhaṅga , asaṃkhyeya etc.; alaṃkāra m. does not mean “decorated”, but décor; p. 165).

The term kūṭāgāra in the sense of palace (of Maitreya) seems to have considerably changed its original meaning (Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture. South India 1983, p. 289: “roofed chamber on a house-terrace”).

The style of the author is (in all his publications) clear and distinct. It is a pleasure to read the book. To go into the details regarding the identifi-cations of scenes of the third and fourth gallery would need a sort of in-vestigation that cannot be the duty of this review.

The selection of figures is not always convincing. Why did the author not publish photos that refer to the same scenes in the first as well as the

118 PANDANUS ’12/1

second tour of visits (e.g. Avalokiteśvara II-47, II-100–102, and, Mahādeva II-48, II-104)? If Supratiṣṭhita is at one point depicted on the ground and at another mid-air, as the text requires, why is only the version on clouds revealed to the reader (1967, Pl. 9, 2012, p. 53, Fig. 12)?

As a matter of fact many publications on Asian art from the first half of the 20th century were of much better quality than contemporary ones. In our case the best photos of the Borobudur reliefs can be found in T. van Erp / N.J. Krom (1920). The photos in Fontein’s thesis (1967) are more brilliant than those in the present publication (2012). At least one vertical section of the monument, such as Erp / Krom 1920, Pls. 1 and 2, would have been helpful for realizing the exact position of the reliefs on the main walls and on the balustrades of the monument.

References

Doi, Torakazu, 1978, Das Kegon Sutra. Das Buch vom Eintreten in den Kosmos der Wahrheit. Aus dem Chinesischen übersetzt. Tokyo.

Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture. South India. Ed. M.W. Meister / M.A. Dhaky, American Institute of Indian Studies, New Delhi 1983.

Erp, T. van / Krom, N.J., 1920, Beschrijving van Borobudur II, Reliefs en Buddha-Beelden. Nijhoff, ‘s-Gravenhage.

Fontein, J., 1967, The Pilgrimage of Sudhana. A Study of Gaṇḍavyūha illustrations in China, Japan and Java. Mouton & Co Publishers, The Hague – Paris.

Fontein, J., 2000, Sculpture, Text and Tradition at Borobudur: A Reconsideration. In: Narra-tive Sculpture and Literary Traditions in South and Southeast Asia. Ed. by Marijke J. Klokke. Brill, Leiden – Boston – Köln, pp. 1–18.

Hikata, R., 1960, Gaṇḍavyūha and the Reliefs of Barabuḍur-Galleries. In: Studies in Indo-logy and Buddhology, presented in honour of Professor Gishō Nakano on the occasion of his seventieth birthday. Koyasan University, pp. 1–51.