Conrad Under Wraps: Reputation, Pulp Indeterminacy, and the 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness

Transcript of Conrad Under Wraps: Reputation, Pulp Indeterminacy, and the 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness

This article was downloaded by: [David Earle]On: 03 January 2013, At: 06:56Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Studia NeophilologicaPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/snec20

Conrad Under Wraps: Reputation,Pulp Indeterminacy, and the 1950Signet Edition of Heart of DarknessDavid M. Earle aa University of West Florida, USAVersion of record first published: 02 Jan 2013.

To cite this article: David M. Earle (2013): Conrad Under Wraps: Reputation, PulpIndeterminacy, and the 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness , Studia Neophilologica,DOI:10.1080/00393274.2012.751666

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2012.751666

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make anyrepresentation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. Theaccuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independentlyverified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions,claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever causedarising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of thismaterial.

Studia Neophilologica 2012, iFirst article, 1–17

Conrad Under Wraps: Reputation, Pulp Indeterminacy, andthe 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness

DAVID M. EARLE

The label “pulp” denotes that which is sensational, formulaic, and cheap, its connotationslong dissociated from its historical and material foundations in the all-fiction, wood-pulpmagazines which proliferated on American newsstands in the early twentieth century.Recently, however, the term has enjoyed a resurgence within critical theory as a meansof deconstructing the unhelpful logic of cultural polarization. Drawing on these develop-ments, this essay uses the sensationally marketed paperback edition of Heart of Darknessissued by Signet in 1950 as a way of recovering the larger history of Conrad’s writings inAmerican pulp magazines. In so doing, it offers “pulp” as a critical tool for questioningConrad’s reputation in relation to Modernism and genre. Comparison of Signet’s market-ing of this edition with those of mid-century race novels, it will be seen, offers a historicallyrevealing parallel between the ambiguity of its cover image and that of Conrad’s ownnarrative.

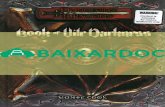

There are many manifestations of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, from Francis FordCoppola’s Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now (1979) to Arcana Comics’ Marlow: Soulof Darkness (2008), which casts Marlow as mercenary in a post-apocalyptic corpo-rate dystopia.1 But perhaps none of these manifestations are quite as surprising as the1950 Signet paperback reprint. This edition is shocking, but not because of any libertiestaken with the text, which the cover pointedly advertises as “Complete and Unabridged.”There is even a good, scholarly introduction written by Albert Guerard, complete with biog-raphy and explanation of symbolism in both “Heart of Darkness” and “The Secret Sharer,”the two stories contained in the volume. Furthermore, the back cover blurb flaunts Conrad’sreputation as “one of the greatest English novelists and perhaps the finest prose stylist ofthem all.” It is, rather, the seriousness of Conrad’s reputation, and the book’s mantle oferudition, that make this text so incongruous, for the cover image (fig. 1) is itself pure pulpsensationalism.

The cover features a shirtless Kurtz, Aryan blonde and spectacularly white, surroundedby dozens of black bodies in ritualistic frenzy. The natives are beating drums, crouchingand waving spears, while looking towards the bright central figure of Kurtz. Next to himis his African concubine, shirtless as well, but dressed from waist down in gleaming whitefabric, as if she has been (literally) enlightened by Kurtz’s whiteness. She seems to bedancing to the drumbeat, her body, in motion, turned away from Kurtz, while coyly lookingover her shoulder at him. The contrast of white and black, light and shadow, highlights thesetwo figures against the backdrop of nude, male, black bodies. I will stop short of sayingthat this illustrates a marriage ceremony, but it is clear that Kurtz and the woman are thecentral figures, and the message that we take from this cover is sensual and sensational.The publishers thought that Kurtz’s unspoken crime was miscegenation or going native –at least, that is what they thought would appeal most to potential buyers.

As gatekeepers of Conrad’s reputation, our reactions to this cover may vary. We maylaugh at its kitschy incongruity, we may see it as unworthy of Conrad’s fiction and rankle atits cheapness. Such reactions arise from a proprietary attitude distinct to academia, wherein

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2012.751666

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

2 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

Fig. 1 Heart of Darkness. Signet Paperback 834. NAL, 1950. Copyright.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 3

we privilege specific aspects – levels of reading or authorial reputation – while disavowingother aspects, such as sensationalism or commercialism, that conflict with academia’s self-image. This edition exemplifies one such instance since it is part of a long genealogy ofpopular reprints that support the idea of Conrad as both popular and populist writer. Suchtexts force us to question the consecrated portrait of Modernism based solely on initialappearances, first editions, and manuscripts. The Signet paperback, no matter how dis-parate to academic reputation, embodies an American version of Conrad that runs counterto tradition, a “Pulp Conrad” – sensational, material, and commercial.

The modern use of the word “pulp” stems from the periodical culture of the late nine-teenth century. Just as “slick” designates expensive slick-paper magazines and “littlemagazine” designates limited distribution and small size, “pulp” originates in the mate-riality of popular magazines and came to designate mass culture and low quality. In 1897,Frank Munsey tried to recapture his success with Munsey’s Magazine by changing thepaper of The Argosy from rag and mineral to cheap wood-pulp. Argosy had long floun-dered as a juvenile fiction magazine, so Munsey also changed the content to stories andserials for an older, more general audience, although Argosy still featured adventure fic-tion prominently.2 The success of these two inexpensive magazines gave rise to imitatorssuch as Ainslee’s (1898), The Popular Magazine (1903), and Young’s (1903). Soon, com-petition was such that specific genres arose in order to appeal to niche markets, includingThe Ocean (1906), Adventure (1910), and Detective Story (1915). These all-fiction pulppaper magazines were distributed to newsstands, train stations, and drug stores, and prolif-erated to such a degree through the 1910s that their covers evolved to grab the attention ofpassersby by means of vivid colors and active or sensational subject matter: the staid covergirls of the 1910s gave way to stylized pin-ups in the 1920s, which were vivid enoughto provoke the censor. But the pulp cover really reached its maturity in the 1930s withhyper-realistic paintings of sensational subjects. The covers promised idealistic love scenesfor the romance pulps, and action for the other genres. Whereas these covers remainedunchanged stylistically, their subject matter became increasingly violent and salaciousthrough the 1950s, at which point they jumped to the paperback form. By now the term“pulp” designated all that was torrid, violent, and formulaic.

The term has, then, outgrown its initial application to a particular style of magazine.It now describes any kind of text that meets certain qualitative attributes. The grind housefilms of the 1970s are described as pulp (hence Quentin Tarantino’s homage to the genre inPulp Fiction [1994]); men’s adventure magazines and slick nudie magazines of the 1950sand 1960s are categorized as pulps, as are most mid-century paperbacks. Yet despite itsnegative connotations, the term is now evoked frequently by literary critics. Robin Walzuses the term “Pulp Surrealism” to describe the influence of Parisian popular spectacleupon the Surrealists (Walz 2000). Paula Rabinowitz has used the term “Pulp Modernism”for the hard-boiled aesthetics discernible in the gritty populist realism of 1930s photog-raphy (Rabinowitz 2002); and Sarah Ann Wells describes Jorge Luis Borges’s miningof popular culture as “pulp history” (Wells 2011). The most common use of the termin current criticism is in the study of the gay and lesbian “pulp paperback” originals ofmid-century. This area of study has been especially productive in highlighting the statusof this sensational form as a touchstone for the gay underground during McCarthyism.The designation “pulp” here stems mostly from the sensational marketing and culturalstigma of the form in question (See Nealon 2000, 745–64; Meeker 2005, 165–88; andKeller 2005, 385–410). In each case, the term has been separated from its original mate-riality. Traditionally used derogatorily for the lowest forms of fiction, “pulp” now standsas a deconstructive signifier enacted to dissolve the great divide between modernism’srestrictive stance and popular culture.

Literary history has, for the most part, overlooked the importance of pulp magazinesas the reading material for a large and largely underrepresented percentage of Americans.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

4 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

There are many reasons for this: they were undeniably economic, formulaic, and dispos-able, and as such were never preserved in the archives. The critical template of “quality”literature doesn’t always apply, but this template has lost potency since the rise of cul-tural studies. Critics like George Bornstein and Jerome McGann moved Modernist textualstudies and genetic criticism beyond manuscripts and typescripts to reprints and popu-lar editions (Bornstein 2001; McGann 1991). Only recently has Conrad studies expandedits focus to popular editions of his work, including newspaper serializations and appear-ances in popular magazines.3 Breaking away from the academic fetish of an author’s firstor hardcover appearance divulges a long history of Conrad under covers that are seem-ingly anathema to the image of Modernist authors as strictly avantgardistes writing, as inConrad’s case, works whose complexity excludes the common reader. Conrad’s pulpishpublishing history in America expands our understanding of the term beyond its simplemetonymic use for all that is blatantly economic, formulaic, and sensational. Recoveringthese dynamics promises to liberate aspects of Conrad’s reputation which have been lostthrough canonization.

Conrad in the pulp milieu

Conrad came to age as a writer in an era at the moment of mass literature’s emergence,before the hardening of strict cultural hierarchies. As Nicholas Daly puts it, “What we seenow as a chasm between two distinct literary cultures, the great divide, was scarcely morethan a crack in 1899. In many respects this was still a homogeneous literary culture” (Daly1994, 4) Both America and Britain were undergoing a popular magazine revolution (Ashley2006; Ohmann 1996). Conrad’s own publishing history, especially the placement of hisserializations, follows this trajectory towards new forms of popular reading: Blackwood’sand The Savoy gave way to Pall Mall and Hutchinson’s, and finally The Star (London)and The Argosy (not Munsey’s but a British reprint magazine).4 Besides mirroring thegeneral trend of magazine publishing, this history shows a writer first establishing a seriousreputation and then parlaying it into economically advantageous placement of future work.For whatever reason, Conrad’s later fiction undeniably appeared in popular venues and metwith mass audience acceptance.

In America, where class and cultural borders were fuzzier, Conrad had a rich pop-ulist publishing presence from the very beginning. The Conrad First website listseight simultaneous daily newspaper syndications of The Nigger of the “Narcissus”concurrent with its appearance in The New Review in 1897.5 Conrad published inMcClure’s Magazine in 1907, The Smart Set in 1914, and Munsey’s in 1915. The verybreadth of content in these magazines illustrates the inclusive literary culture describedby Daly.

Conrad’s appearances in Munsey’s and McClure’s firmly embedded him within theeconomy of mass literature. Katherine Baxter, in her overview of Conrad’s serialization of“The Brute” in McClure’s, concludes that it “represents [Conrad’s] necessary but alwaysambivalent relationship with the popular press” (Baxter 2009, 130). Roger Osborne hasestablished how the appearance of Victory in Munsey’s “should not be rejected as anephemeral form outside of the textual tradition of Conrad’s authority” (Osbourne 2009,285). Conrad’s serialization in popular American magazines exposes the commercial sideof publishing that is so evident in Conrad’s correspondence yet often ignored in the abstrac-tion of canonization and criticism. Similarly, such forms as serializations and popularmagazines demand a different critical methodology than that which has evolved from thestudy of traditional forms such as little magazines and first editions. These popular maga-zines in which Conrad appeared were emergent mass-magazines of the type that evolvedinto the pulps. The Smart Set illustrates this evolution even more explicitly.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 5

The Smart Set has been seen as a major American venue for Modernism and a keyagent in the growth of Conrad’s reputation (Mallios 2010; Hamilton 1999; Earle 2009).Besides Conrad, it published James Joyce, F. Scott Fitzgerald, D. H. Lawrence, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and many others. During this period of Modernist exposure, editors WillardHuntington Wright, H. L. Mencken, and George Jean Nathan stood against provincialAmerica, especially on issues like censorship and prohibition. This is the heritage for whichthe Smart Set is remembered. What has been forgotten is how these Modernists appearedalongside authors such as Dashiell Hammett, Edwin Baird (future editor of Weird Tales),and, in Conrad’s case, Achmed Abdullah, a colonial adventure writer who was often fea-tured in The Argosy, All-Story, and Top-Notch pulp magazines. Moreover, The Smart Setshared authors, editors, and office space with Parisienne, Saucy Stories, and Black Maskmagazines – pulps started by Mencken and Nathan and filled with left-over Smart Setsubmissions – and inspired the genre of “smart” or risqué pulps like Saucy, Snappy, andBreezy Stories (Earle 2009, 41–59). Academics have scrutinized The Smart Set in termsof its affinity to little magazines and Modernism, but few have recognized that it was arelatively open magazine which drew on a wide spectrum of literary “quality.”

This lateral (as opposed to hierarchical) vector of the early-twentieth-century Americanliterary marketplace is even more apparent in reprint magazines such as The Golden Bookand Famous Story, both of which appeared in the mid-1920s. These magazines, whosestated goal was to bring quality literature to the newsstand, featured respected authorsmixed in with genre authors. When The Golden Book hit newsstands in 1924, many weresurprised to find such established writers in its pages. As one journalist put it, “You hadheard all the names before, but for a moment you could in no way connect them with anews-stall. It was like running across a bishop in a saloon or seeing your wife about to playquarterback for varsity” (Mott 1968, 117). The Golden Book was printed on pulp paperwith typical line drawings (wood-pulp is unsuited to photographic reproduction) and brightArt Deco covers. Ads were mostly for correspondence schools and publishers, reflectingits dual popular and literary ethos. And its list of authors was indeed impressive: D. H.Lawrence, Arthur Symons, Thomas Hardy, Alexander Pushkin, W. B. Yeats, and more.Conrad appeared eleven times in the magazine, including Youth, Heart of Darkness, and anexcerpt from Lord Jim. The Golden Book’s formula obviously worked. Within a year of itsinitial publication, it had a distribution of over 165,000, according to the Audit Bureau ofCirculation for January–June 1926, and it would inspire copycat magazines such as FamousStory, launched the next year. Published by George Delacorte, an established pulp publisher(“I Confess,” War Stories), Famous Story serialized “The End of the Tether” alongsideFitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in 1926. The magazine used pulp paper interspersed withsome slick paper sections for illustrations and ads (fig. 2).

These two reprint magazines can be considered pulps in terms of materiality, venue, andmarketing, if not content. They dispel the stigma of pulp magazines as entirely formulaicor sensational. In actuality, pulps played an important part in the intellectual life of thelower and middle classes in the early twentieth century; Richard Wright and John Fantehave written about the importance of pulps as reading matter during their adolescence(Wright 1998, 133; Fante 1999).6 Conrad’s presence in these magazines illustrates the massaudience’s cultural and intellectual aspirations – the pulps as, in fact, a training ground forliteracy. At the very least, the pulps put Conrad into the hands of hundreds of thousands ofreaders in a form that was neither antagonistic nor condescending to the masses.7

In these magazines Conrad became a gateway figure for class mobility and literacy, ascan be seen in the numerous ads for Doubleday’s Inclusive Kent Edition of Joseph Conrad(“A saving of $140.75 over the limited Autographed Sun Dial Edition”). These ads playoff of class aspirations for self-improvement (see fig. 3). After describing the expense ofthe Sun Dial Edition, which “most bookish people have heard of,” the ad lets the readerknow that this edition is “the best opportunity ever presented” for “those who want to own

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

6 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

Fig. 2 The Famous Story Magazine, January 1926, containing first installment The End of the Tether.Copyright 1925 by the Famous Story Publishing Co.

Conrad complete – and what intelligent book lover does not?” The ad outlines the “secretof Conrad” as “the exciting narratives” based upon actual experiences, “the riff raff of theworld thrown up in the mysterious East,” and “strange and ever-bewitching women.” It

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 7

Fig. 3 Advertisement for the Kent Edition of the Complete Works of Joseph Conrad, The Famous StoryMagazine, January 1927. Inside front cover.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

8 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

ends by quoting Gouveneur Morris, “‘Those who have not read Conrad are not well read,’”adding that this is “One of the truest things ever said of Conrad. . . . No one who professes toappreciate good literature can afford not to be familiar with every one of his great novels.”In short, this edition puts buyers on the same cultural standing as the “735 wealthy book-collectors [who] paid a total sum of $129,176.25 for this edition.” Surrounded by advertsfor correspondence schools, these ads for the Kent Edition establish Conrad as a brandname selling cultural self-improvement; Conrad was a “good investment.”

In America, Conrad offered a stepping stone for class aspiration. In Gentlemen PreferBlondes (1925), Anita Loos presents gold-digger Lorelei Lee as receiving “a whole com-plete set of books for my birthday by a gentleman called Mr. Conrad” (Loos 1925, 20).Throughout Loos’s satire, social standing is dependent upon being “literary,” and numer-ous (rich) suitors try to “better” Lee via gifts to her library, rather than the diamonds shewants. As Lee explains, “I mean it seems to me a gentleman who has a friendly interest ineducating a girl . . . would want her to have the biggest square cut diamond in New York.”Instead, she gets the Conrad.

But according to the Kent Edition advertisements, Conrad’s intellectual worth is equatedwith economic worth: “The world’s most famous authors paid homage to [Conrad] asthe greatest of them all; his original manuscripts, at an auction before his death, sold for$110,998 (probably no such tribute had ever been paid to an author while he was stillalive).” Such reductions of cultural capital to monetary capital are the source of the humorand criticism within Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. “Getting educated” for Lee means (amongother things) getting jewelry, gold-digging as indicative of both shallow cultural posing andconspicuous consumption. A favorite of Faulkner and Joyce, Gentlemen Prefer Blondesparticipates in an intellectual critique of popular literacy as culturally diluting and unsa-vory because of its blatant commercialism. This stance is not terribly dissimilar to theconflicted relationship between Modernist writers (Conrad included) and popular period-icals, the former snidely denouncing the latter while simultaneously looking to them as awell-paying outlet for their work.

Ironically, this commercialization of Conrad evidenced in these ads, and in the glut ofpopular sets over the 1920s (eight between 1917 and 1928), may have caused a down-ward spiral in regards to his high-literary reputation. Critics have seen the reaction againstConrad during the 1930s as the result of Modernist reaction to his “florid” Victorian style,but it could also have much to do with his wide dissemination in popular and blatantly com-mercial forms, such as these popularly marketed sets and pulp magazines (Knowles 2009,67–69). The overtly commercial aspects of pulps are one of the main reasons why theyhave been so long ignored by literary historians.8 The pulp magazines should not be writ-ten off as literary detritus. Tellingly, Conrad published in magazines that are much morestereotypically pulpish than The Golden Book and Famous Story: “An Outpost of Progress”in Britain’s The Grand Magazine (1906), “The Inn of the Two Witches” in Ghost Stories(1930), and, most famously, The Rescue in Romance magazine (1919). Conrad’s pulp pub-lications have been largely neglected exactly because they are popular and unavoidablyeconomic, but also because they demand a distinct methodology of reading that differsfrom how we read hard-covers, story collections, and little magazines.

Put more contentiously, because literary aura relies upon an archive that privilegesmanuscripts, first editions, and hard covers, the construction of academic reputation resistsmaterial commercialism – and the pulps are defined by their materiality: pulp paper, pulpmagazines. Yet canonization is also reliant upon reprints, though only in sanctioned de-contextualized anthologies rather than popular forms. These pulp manifestations, reprintor otherwise, and the ascendancy of Conrad’s popular reputation in America as both apopulist writer and literary author stand as evidence of his commercialization. The his-torical academic reclamation of Conrad as too difficult for or opposed to a mass-audiencepolices cultural borders between audiences. Reception, though, is unstable. The materiality

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 9

of a book – its price, retail venue, meta-textual or critical apparatus – attempts to guide ordictate its reception, as most explicitly illustrated in limited first editions and academicanthologies. Popular reprints of Modernist classics, especially those that categorize thework in specific genres, prove that not only is text unstable but so is reputation. Considerhow any cultural cachet acquired by Heart of Darkness in appearing in the thousandth issueof Blackwood’s Magazine was lost in its republication in The Golden Book or, for that mat-ter, the 1950 Signet paperback. What emerges from a history of American populist printingis a new, anti-academic, street-level version of “Conrad”: as a writer of the newsstand.

Conrad beyond criticism

There is little question that Conrad’s fiction relies upon the conventions of the adventurestory and the sea narrative; the degree to which he is categorized as a genre writer is anongoing debate, and one which, ultimately, is moot. Undeniably, he has been read and mar-keted as genre fiction by millions of readers, just as millions have read him in academicallysanctioned anthologies. Only relatively recently have studies of Conrad, and modernism ingeneral, divulged publication histories that were accessible by the working classes in news-papers, book-clubs, and serializations (Rose 2001, Donovan 2005, Collier 2006, Rainey1998). Conrad’s popular reception is of history, while his academic reception supportstoday’s Conrad industry. There is a constructed opposition between these two extremes ofhighbrow and lowbrow, despite ongoing attempts to destabilize these categories. If, as hispulp publications show, Conrad existed on both sides of the “great divide,” perhaps it is notjust that our portrait of Conrad is askew but that our very line of vision is being obstructed.

Genre writing must follow certain formulaic conventions, and must be encoded or cat-egorized as generic by the marketplace. In actuality, genres are more multiplicitous thansingular, just as the restrictions (and competition) of the marketplace ensure invention.A work is considered of a particular genre if it has an arbitrary number or combination offormulaic attributes, including plot elements, setting, tone, and characterization. Sciencefiction can include alternate future, future war, steam punk, space opera, and cyberpunk; itcan range from utopian fantasy and Victorian romance to the postmodern and post-human.Genre need not be a strict or limiting categorization. Pliable and porous, it can include arich variety of authors and quality. The second aspect of genre, how a book is marketed,poses a greater challenge to the conventions of literary scholarship insofar as it involves thenotion already mentioned, that literary study is based upon an excessively narrow archive.

We privilege manuscripts because they are closer to the aura of authorship, uncontami-nated by publishers, copyeditors, and marketing department. And we privilege first editionsbecause there is less possibility of contamination, and so on down the genealogy of print.If we consider reception, dissemination, and the afterlife of a text, then authorial intent isof little importance. Reprints with large distribution trump “authoritative” editions. Oncein the marketplace, a text cannot be contained; it jumps cultural borders, goes viral, andbecomes “mass” literature. Pirated copies are excellent examples of this, as are genericor sensational reprints. Genre is considered mass literature because it was overabundant,distributed in mass forms such as penny dreadfuls, dime novels, and pulp magazines.Academic neglect of these forms is a history of containment and strict categorization.

Of all Conrad’s texts, Lord Jim has arguably proven most difficult to contain or cate-gorize: it is adventure fiction, Modernist, a “Modernist romance,” post-modern, yet Jimhimself is a stereotype, the “unflinching hero” of a thousand sea adventures. At a singleglance Marlow judges him “one of us” and “typical of that good stupid kind we like tofeel marching right and left of us through life” (Conrad 1996, 30). On the surface, Jimis generic, of a genre, hence the novel’s eponymous title Lord Jim: A Romance. But heis much more – he is symbolic and deeply flawed. Ironically, critics also accused Lord

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

10 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

Jim of being deeply flawed, uneven exactly because of the book’s straightforward andconventional (or generic) second half.9

Yet the text cannot be contained. Jim’s identification with “the sea-life of light literature”led critics to reconceive the book as metatextual, criticizing British Masculinity and thevalues of mass literature as flawed (see Kestner 2010, 1; McCracken 1993). Therefore, LordJim is a self-reflexive criticism of form like Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. By admitting thebook’s generic elements, either as marring the novel or enabling its complex criticism ofmasculinity, identity, and popular fiction, academic critics have been able to accommodategenre as Lord Jim’s “Secret Sharer.”

The famous disparity between the book’s two halves corresponds not to the antagonismbetween Modernism and twentieth-century mass literature, but Modernism’s symbiosiswith the market in a popular narrative that resists segregation or categorization. In otherwords, Lord Jim is a generic, stereotypical sea story in which a hero who doubts his couragefinally proves himself in a moment of duress. It succeeds as such because it is preciselynot this kind of narrative; the generic conventions of the form demand novelty becauseof hyper-competition, and Lord Jim both meets and refuses reader’s expectations. Conradhimself admitted that the novelistic form is “in the end a matter of convention,” and by theend Lord Jim is literally conventional in both senses of the phrase (qtd in Watt 1979, 309).

That Lord Jim might more accurately be defined as “Generic Avant-Garde” is suggestedby contrasting descriptions of Conrad’s work in the 1920s. In The Commercial Side ofLiterature (1926), a guide for selling fiction, Michael Joseph outlines various genres of themodern novel, including the love story, adventure, psychological novel, detective, romance(meaning fantasy), western, aviation, and of course sea stories. He lists Conrad under thelast of these rather than the psychological novel: “The steady popularity of writers likeClark Russell, James B. Connolly, Richard Matthews Hallet, Albert R. Wetjen, and, ofcourse, Joseph Conrad, provides a useful pointer for the young writer with any experienceof the sea and ships” (Joseph 1926, 29). Listing Conrad amongst authors who publishedin Pall Mall, Metropolitan, and The Saturday Evening Post as well as pulps such as SeaStories, Action Stories, Danger Trail, and Adventure illustrates the porous lines betweenliterary cultural positions as well as Conrad’s reputation as genre author.

Joseph points out that “psychological studies without the framework of a good storyare apt to be tedious and only a gifted craftsman can be expected to combine the two”(Joseph 1926, 33). He may well have Conrad in mind, especially since this recalls manyof the portraits of Conrad in the popular press that surrounded his visit to America in1923 and death in 1924. For example, “The Secret of Joseph Conrad’s Appeal” in CurrentOpinion, a gloss on an article by A. Hutchinson in the New York Times, states: “With theearlier writers [of sea stories,] adventure was the main concern, and in their field theyare unsurpassed. In Conrad, too, we may find adventure and romance. But it is ‘handleddifferently’ . . . [due to Conrad’s] collective psychology of the ship . . . [and] mankind”(June 1923, 677). Here we have a familiar portrait: Conrad as craftsman of depth. Coming ayear after Modernism’s annus mirabilis, this article exemplifies the early canonization pro-cess: Here is the groundwork for the later, academically defined schism between high andlow. It is impossible to separate “the ship” from “mankind”; these are more than Conrad’ssubject: the ship is also Conrad’s “craft,” i.e. his métier (writing), and “mankind” is bothConrad’s audience and his subject.

The disjunction between the aura of a work’s first appearances or an author’s academicreputation and the mundane populism of reprints or popular reception brings into questionthe possibility of attempting to dictate the cultural identity of a given text. Such attempts toinfluence a text’s reception by authors or academics are rendered moot by the afterlife of aliterary work, including the ways in which it was ultimately read and received beyond thecritical coterie and the bookstore. What does it mean if Lord Jim criticizes its own genericfoundations yet is marketed or received as that very genre? Lord Jim was, after all, subtitled

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 11

“A Tale” and “A Romance,” which raise the reader’s expectations of formulaic convention.Madame Bovary was a bestseller precisely because it relied on the very romance conven-tions that it criticized. Authorial intentions or the efforts of publishers have only a slightinfluence upon the reception of literary works; once in the marketplace, texts – especiallyambiguous texts – refuse to be contained.

To substantiate this last point, it is sufficient to allude to the many popular editions ofLord Jim, from the excerpts in The Golden Book in the 1930s to the Armed Services paper-back of the 1940s to the Classic Illustrated comic of the 1960s. And yet the parallel thatI ultimately want to draw here is to the book’s exterior and, specifically, how the way inwhich it has been marketed forces us to consider the multiplicity of possible readings out-side of canonized and canonizing agenda. It is this matrix of factors that we find explicitlyembodied in the Signet edition of Heart of Darkness.

Paperback Conrad

The tension between surface and interior, a central theme of Lord Jim and much ofConrad’s fiction, parallels that between modernism and genre; it is not an oppositionalbinary but a contact zone that demands reflexive thinking about text, reception, genre, andphenomenological reading. This relationship is embodied in the dialectic between the coverand content of the pulp paperback, nowhere more evident than in the clash between culturalstances of pulp paperbacks of Modernist texts. These are the contact zone of avant-gardeand mass literature, academic and populist, art and pulp. Such texts are intrinsically decon-structive to the traditional definitions of “pulp” and “modernism,” the cultural assumptionswith which they are imbued, and the border between them.

In 1939, Robert De Graff started the American paperback revolution by launchingPocket Books.10 There had been other attempts at mass-market paperbacks, especially inEurope (Penguin, Albatross, Tauchnitz), but they were aesthetically austere with uniformcovers. The key to the success of paperbacks in America was that they participated in avisual and reading culture which had already been established by pulp magazines. Pocketbooks were distributed in newsstands and had illustrative covers that competed with themagazines surrounding them. In effect, the cultural and hierarchical distinction betweenhardback and magazine was bridged by the paperback. Pocket’s early covers were inspiredby the dustcover designs of its parent company, Simon and Schuster. Often abstract andsymbolic, rarely realistic, they were both novel and familiar to their potential buyers. The25-cent paperback was highly portable and visually appealed to the magazine buyer. Yet itsdesign was reminiscent of an expensive hard cover that could only be found in a bookstore,a fact which De Graff made much of in his marketing. The bookstore, with its constantlychanging and relatively expensive crop of first editions, was the ground of high culture anda place where staff (stand-ins for the book critic) could direct patrons. The newsstand wasa purely commercial space, on the other hand, organized around the quick and convenientconsumption of disposable reading matter. The modern paperback blurred, even destroyed,the conceptual line between these spaces, a refusal to differentiate that became galling tocultural critics as paperback publishers appeared on the scene, many with backgrounds inpulp rather than respectable hardback publishing.

In 1941, both Avon and Penguin launched American paperback lines, followed byPopular and Dell in 1943, Bantam in 1945, and Signet in 1948. By the late 1940s, therewas a general shift in paperback cover design away from hard-cover aesthetics and towardsthe sensationalism and realism of pulp covers. In 1954, Malcolm Cowley could write ananti-paperback diatribe, in which he browses the paperback racks of Chicago’s SouthSide, lamenting the destruction of American culture by paperbacks that do not discrim-inate between high and low literature (Cowley 1954, 96–99). In the fifteen years between

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

12 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

the first Pocket Book and Cowley’s essay, the paperback had fundamentally changedAmerican publishing. Paperbacks were now so successful that even conservative firmssuch as Scribners started their own lines of “quality” paperback – larger, more expensive,and without illustrative covers. Such “academic” paperbacks were in direct reaction to themass-market paperbacks and their pulp aesthetics.

By 1950, when it brought out an edition of Heart of Darkness, Signet had the mostdiverse catalogue of books among paperback publishers. A division of The New AmericanLibrary of World Literature (NAL), Signet had acquired Penguin’s catalog in a 1948 buy-out. Unlike its parent company, Penguin America featured cover illustrations. Like thoseof Pocket Books, these were more abstract; most were painted by Robert Jonas, a friendof Willem de Kooning. After NAL’s buyout, Jonas’s art was used mostly for nonfiction,and the realistic artwork by James Avati became the house style for Signet. The differencesof style are apparent in a comparison of Signet’s Heart of Darkness with the PenguinAlmayer’s Folly published in 1947 (fig. 4). Penguin’s cover is bright, minimalist, and crit-ical to a degree in that it privileges Nina over the white figure in the background, notsalaciously but as dominant. Indeed, recent criticism of the novel has similarly reevaluatedher as an empowered figure outside the white patriarchal colonial system (Sewlall 2006;Purdy 2005, 131; Goodman 1998).

Signets, on the other hand, were almost uniformly illustrated in the pulp style with “emo-tionally realistic” scenes from the narrative. Compared to publishers such as Avon andPopular books, Signet is more staid but in general its art directors would mine the text forthe slightest hint of salacious innuendo, no matter how contrived, and this would becomethe cover’s subject. Heart of Darkness is typical of Signet’s design and, if anything, a littlemore extreme than usual in depicting the woman as topless. Nudity was nominally tabooand guaranteed trouble with the censors – and, of course, high sales.

These paperbacks are designated “pulp” because of their sensational marketing and,to a lesser extent, inexpensive form and wide popular distribution. Like pulp magazines,paperback publishers offered a variety of literature that was as wide and inclusive as gen-eral publishers. Paperbacks offered the worst and best of literature. As a general rule, theonly literature excluded was at the top of the cultural scale, i.e. literature thought too dif-ficult for the general public. But there are so many exceptions to this rule that it fallsapart under scrutiny: much of Faulkner was available in paperback at mid-century, as wasVirginia Woolf’s Orlando and The Years, and just about all of D. H. Lawrence. EvenUlysses was sold as a pirated paperback by Marvin Miller’s pornographic Collector’sPress. What makes possible the publication of certain Modernist classics, but not oth-ers, was exactly the kind of sensationalism that enabled Modernism’s breakthrough in thefirst place, that is to say, what attracted the public’s attention in the 1920s and facilitatedits popularity beyond mere novelty. The challenging of Edwardian morality, undeniably adefining characteristic of literary Modernism, made these texts infamous and, eventually,read by a wider public. This is why Signet pursued and published Portrait of an Artistand not Joyce’s arguably more accessible Dubliners. We only have to consider the scandalsurrounding Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Ulysses, and Faulkner’s Sanctuary, and the impor-tance of these texts for their authors’ canonization as well as their popular reputations, tosee that sensationalism was an integral part of Modernism’s heritage despite the effortsof English Studies to spackle over this history. The paperback has suffered a similar fate:Scribner’s recalled paperback publishers’ reprint licenses for Hemingway and Fitzgeraldin order to begin their own collegiate paperback line, illustrating the attempt to realign lit-erature into sanctioned definitions, and paperbacks have been historically excluded fromarchives, which favor instead the format known as “library binding.”

Victor Waybright, co-owner of NAL, writes in his memoirs that he saw the company’smission as “a constructive force in the life of the times”: in the first place, it fought censor-ship of good literature “regardless of the price or method of distribution of books, and to

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 13

Fig. 4 Almayer’s Folly. Penguin Paperback 619. Penguin, 1947. Cover art by Robert Jonas.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

14 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

prevent the establishment of a double standard – one for the rich, another for the poor, i.e.one for the $5.00 book in the nation’s twelve hundred book shops, another for the 25-centbook in over a hundred thousand retail outlets”; in the second, it brought quality litera-ture to the general public (Weybright 1967, 202–3). Weybright sought out both risqué andModernist literature, hence Signet’s books and marketing (covers, distribution) embodythe company’s blended mission as well as an ethos deconstructive to cultural divides.

Yet Heart of Darkness is not Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Its preeminence as the standardConrad for high school students and college freshman is due as much to its inclusion inanthologies such as the Norton Introduction series as to its showcasing of Conradian styleand themes. This Signet edition, with its orgiastic and titillating aura, stands counter to allthat. One can only imagine that a buyer of the 1950s might be disappointed in the storysince it barely hints at the action depicted on the cover. It would be convenient to think thatthe thematic and stylistic gap between text and cover is impossible to bridge, yet this editionwent into at least three printings, which means that it sold at least 600,000 copies.11 Thequestion then becomes: why choose Heart of Darkness, and why put Kurtz’s relationshipwith his African mistress on the cover?

Conrad would have been a logical choice for Signet since he had a strong literary repu-tation and could be marketed as genre literature to a popular audience. Having Conrad inthe Signet catalog brought cultural capital that would serve as a levee against charges ofprurience. In other words, Conrad conformed perfectly to Weybright’s mission for NAL.The choice for Heart of Darkness was more complicated, since Weybright had initiallywanted The Nigger of the “Narcissus.” However, he eventually listened to the objectionsof his sales department that the title would be too contentious, despite the fact that “WalterWhite of the NAACP agreed to write a foreword condoning the title” (qtd. in Bonn 1989,144). He opted for Heart of Darkness in order “to avoid any possible misconceptions of theattitudes of New American Library on the delicate question of the use of the word ‘nigger,’even in a semi-classical frame of reference” (qtd. in Bonn 1989, 144).

Weybright’s sensitivity was pragmatic: African-Americans were now an importantmarket. According to Weybright, NAL

[s]timulated the distribution of books in predominantly Negro neighborhoods . . . where previouslymagazine wholesalers had insisted that self-service book racks would be doomed by excessive pil-fering. Our experience demonstrated the very opposite. Aspiring young negroes were a substantialand grateful audience, pleased by the fact that they didn’t have to buy their literature “downtown.”(qtd. in Bonn 1989, 220)

The last statement is ironic since it reverses Cowley’s odyssey to the South Side of Chicago,where he derides the ungoverned dissemination of literature to the masses. But Weybright’schoice for Nigger of the “Narcissus”, condoned by the NAACP, and Heart of Darknessadorned with this particular cover, situate this edition as a “Race Novel.”

Race novels were some of Signet’s most popular sellers during the repressive Cold Waratmosphere of the 1950s and up to the Civil Rights movement. By the time its Heart ofDarkness appeared in 1950, Signet had already published Richard Wright’s Black Boy(1950) and Uncle Tom’s Children (1947), Ann Petry’s The Street (1949), Lillian Smith’sStrange Fruit (1948), and Will Thomas’s God is for White Folks under the title Love KnowsNo Barriers (1950), soon to be followed by Chester Himes’s If He Hollers Let Him Go(1954). Just six months previously, Signet had shocked the publishing world by announcingit was going to break its 25-cent rule by publishing a series of longer paperbacks at 35 cents;the “Signet Giants” was launched with Richard Wright’s Native Son in 1950, followed byRalph Ellison’s Invisible Man in 1953. By the time it published Heart of Darkness, notesKenneth C. Davis, NAL had “established itself as the only mass market reprinter willing tohandle serious work by black writers or about blacks” (Davis 1984, 148).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 15

It is difficult to align NAL’s humanizing and populist social ethos with the Signet coverof Heart of Darkness, which seems to justify Chinua Achebe’s condemnation of the story’sportrayal of Africans as chaotic and dehumanized savages. The African woman depicted onthe cover is clearly meant to embody the lure of the Dark Continent for the white explorerand reader, enticing them to penetrate continent and text alike (see Bunn 1988). Her coylook and body language, coupled with Kurtz’s clenched fists and resistant stance, make itclear that she is inviting him to “go native.” For black readers, the cover is equally enticingas a book about taboo race relations, while the fact that the scene nowhere takes place inConrad’s novella opens it up for interpretation.

The cover, like the NAL publications in this series, dictates a reading of the novel asa “race novel.” A reader unfamiliar with the text would pick up on the racial themes –whether Conrad’s text is highlighting the plight of the colonized or further dehumanizingthem – because of the “emotional realism” of the cover vignette. Reading such themesmay seem commonplace to us in the wake of Achebe’s accusations of racism, but this waspublished twenty-five years before Achebe’s talk. Lest we forget, the depoliticization ofConrad by Southern Agrarians and New Critics reached its apogee in 1950, by which pointhe had been established as the maestro of stylistic complexity and psychological depth (asGuerard’s introduction insists), and cleansed of his popular and generic genealogy.12 Thecover reminds us that the imperial brutality depicted in Heart of Darkness would resonate inthe early 1950s as Civil Rights forced itself upon the public’s consciousness. Peter Mallioshas shown how the ambiguity of Conrad’s novella generated highly conflicting responseswith regard to race in America, and the Signet cover displays this same dynamic (Mallios2010, 186– 217).

Whether Signet’s cover opens up Heart of Darkness to contemporary debates overrace, or is simply racist, it spectacularly affirms the ambiguity and instability of Conrad’sreception. Ultimately, this pulpish and sensational Heart of Darkness, the culmination ofConrad’s popular publishing history, deconstructs binaries precisely because of the dis-junction between Conrad’s reputation and the pulp form. Our reaction to this cover’s“mis-marketing” is a modern one, skewed by prejudice against its form. Ultimately, thiscover is perfectly appropriate in its theme of miscegenation, not because it is Kurtz’s unde-fined crime, but because this edition refuses to be segregated. It is itself a hybrid betweenclassifications that are ultimately cultural constructions, non-essentialist. And that, ulti-mately, is what “pulp” means in its original sense: a formless mass, without border, shape,or form. Such popular forms of modernism “pulp” our own inherited literary prejudices.

David M. EarleUniversity of West FloridaUSA

NOTES

1 Thanks to Patrick Belk and Stephen Donovan for help with earlier drafts of this article.2 On the pulps, see Peterson 1964, 306, 314–15; Goulart 1972; Goodstone 1970. See also Ohmann 1996 for an

account of the role magazines played in the rise of popular culture.3 The entrenchment of cultural studies promises a shift in Conrad Studies. See, for example, Donovan 2005 and

Mallios 2010.4 For this trajectory, see the 2009 triple-issue of Conradiana on “Conrad and Serialization,” especially the

contributions by Laurence Davies and David Finklestein on the placement of Conrad’s early stories.5 Available at www.conradfirst.net/view/volume?id=23.6 On pulps as tools for acculturation, see Smith 2000, 23.7 The pulps, especially high-brow literary manifestations in them, are similar to the working class reading clubs

described by Jonathan Rose (Rose 2001). Many of the magazines had vibrant letters-to-editor sections forreaders’ response and critique.

8 The advent of Material Modernism, a subgenre of New Modernist Studies, challenges this traditionalparadigm. See in particular Bornstein 2001, Cooper 2004, and Dettmar and Watt 1996.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

16 D.M. Earle Studia Neophil iFirst (2012)

9 For an account of this long-standing debate and dismissal of the book’s second half, see Erdinast-Vulcan1991, 32.

10 Schreuders 1981, 6–8. For a general history of paperbacks, see Davis 1984.11 The normal edition size for a mid-century Signet was anywhere between 200,000 to 500,000 depending on

the title; my estimate is, if anything, conservative (Bonn 1989, 93–6, 178).12 See White’s reading of F. R. Leavis’s “de-genrefication” of Conrad in 1948 (White 1993, 1).

REFERENCES

Ashley, Mike. 2006. The Age of the Storytellers. London: British Library.Baxter, Katherine. 2009. “‘He’s lost more money on Joseph Conrad than any editor alive!’: Conrad and McClure’s

Magazine.” Conradiana 41.2–3 (Fall/Winter): 115–31.Bonn, Thomas. 1989. Heavy Traffic & High Culture. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University.Bornstein, George. 2001. Material Modernism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Bunn, David. 1988. “Embodying Africa.” English in Africa 15.1 (May): 1–28.Collier, Patrick. 2006. Modernism on Fleet Street. Aldershot: Ashgate.Conrad, Joseph. 1996. Lord Jim. New York: Norton.Cooper, John Xiros. 2004. Modernism and the Culture of Market Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.Cowley, Malcolm. 1954. The Literary Situation. New York: Viking.Daly, Nicholas. 1994. Modernism, Romance and the Fin de Siècle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Davis, Kenneth. 1984. Two-Bit Culture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.Dettmar, Kevin, and Stephen Watt. 1996. Marketing Modernisms. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.Donovan, Stephen. 2005. Conrad and Popular Culture. New York: Palgrave.Earle, David. 2009. Re-Covering Modernism: Pulps, Paperbacks, and the Prejudice of Form. Burlington, VT:

Ashgate.Erdinast-Vulcan, Daphna. 1991. Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper. Oxford: Clarendon.Fante, John. 1999. Wait Until Spring, Bandini. New York: Perennial.Goodman, Robin Truth. 1998. “Conrad’s Closet.” Conradiana 32.2 (Fall): 83–123.Goodstone, Tony. 1970. The Pulps. New York: Chelsea House.Goulart, Ron. 1972. An Informal History of the Pulp Magazine. New York: Ace.Hamilton, Sharon. 1999. “The Smart Set Magazine and the Popularization of American Modernism.”

Unpublished Dissertation, Dalhousie University.Joseph, Michael. 1926. The Commercial Side of Literature. New York: Harper’s.Keller, Yvone. 2005. “‘Was It Right to Love Her Brother’s Wife So Passionately?’: Lesbian Pulp Novels and the

U.S. Lesbian Identity.” American Quarterly 57.2 (June): 385–410.Kestner, Joseph. 2010. Masculinity in British Adventure Fiction. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.Knowles, Owen. 2009. “Critical Responses, 1925–1950.” In Conrad in Context, ed. Allan H. Simmons, 67–74.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Loos, Anita. 1925. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. New York: Boni and Liveright.Mallios, Peter Lancelot. 2010. Our Conrad: Constituting American Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.McCracken, Scott. 1993. “‘A hard and absolute condition of existence’: Reading Masculinity in Lord Jim.”

Conradian 17.2 (Fall): 17–38.McGann, Jerome. 1991. The Textual Condition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Meeker, Martin. 2005. “A Queer and Contested Medium.” Journal of Women’s History 17.1 (Spring): 165–88.Mott, Frank Luther. 1968. A History of the American Magazines: Volume 5. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.Nealon, Christopher. 2000. “Invert-History: The Ambivalence of Lesbian Pulp Fiction.” New Literary History

31.4 (Autumn): 745–64.Ohmann, Richard. 1996. Selling Culture: Magazines, Markets, and Class at the Turn of the Century. London:

Verso.Osborne, Roger. 2009. “The Publication of Victory in Munsey’s Magazine and the London Star.” Conradiana

41.2–3 (Fall/Winter): 267–88.Peterson, Theodore. 1964. Magazines in the Twentieth Century. Second edition. Urbana: University of Illinois

Press.Purdy, Dwight. 2005. “The Ethic of Sympathy in Conrad’s Lord Jim and Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss.”

Conradiana 37.1–2 (Spring/Fall): 119–32.Rabinowitz, Paula. 2002. Black & White & Noir: America’s Pulp Modernism. New York: Columbia University

Press.Rainey, Lawrence, 1998. Institutions of Modernism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Rose, Jonathan. 2001. The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Studia Neophil iFirst (2012) The 1950 Signet Edition of Heart of Darkness 17

Schreuders, Piet. 1981. Paperbacks, U.S.A. New York: Blue Dolphin.Sewlall, Harry. 2006. “Postcolonial/postmodern Spatiality in Almayer’s Folly and An Outcast of the Islands.”

Conradiana 38.1 (Spring): 79–93.Smith, Erin. 2000. Hard-Boiled. Philadelphia: Temple.Walz, Robin. 2000. Pulp Surrealism. Berkeley: University of California Press.Watt, Ian. 1979. Conrad in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.Wells, Sarah Ann. 2011. “Late Modernism, Pulp History: Jorge Luis Borges’ A Universal History of Infamy

(1935).” Modernism/modernity 18.2 (April): 425–41.Weybright, Victor. 1967. The Making of a Publisher. New York: Reynal.White, Joanna. 1993. Joseph Conrad and the Adventure Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Wright, Richard. 1998. Black Boy. New York: Perennial.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dav

id E

arle

] at

06:

56 0

3 Ja

nuar

y 20

13