Comparative Political Studies: 751 Comparative Political Studies Telecommunications Varieties of...

Transcript of Comparative Political Studies: 751 Comparative Political Studies Telecommunications Varieties of...

http://cps.sagepub.com/Comparative Political Studies

http://cps.sagepub.com/content/37/7/751The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0010414004266868

2004 37: 751Comparative Political StudiesMark Thatcher

TelecommunicationsVarieties of Capitalism in an Internationalized World: Domestic Institutional Change in European

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:Comparative Political StudiesAdditional services and information for

http://cps.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://cps.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://cps.sagepub.com/content/37/7/751.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Jul 29, 2004Version of Record >>

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

10.1177/0010414004266868COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS

VARIETIES OF CAPITALISM IN ANINTERNATIONALIZED WORLD

Domestic Institutional Changein European Telecommunications

MARK THATCHERLondon School of Economics

This article examines how internationalization affects domestic decisions about the reform ofmarket institutions. A developing literature argues that nations maintain different “varieties ofcapitalism” in the face of economic globalization because of diverse domestic settings. However,in an internationalized world, powerful forces for change applying across borders can affect deci-sion making within domestic arenas. The article therefore analyzes how three factors (trans-national technological and economic developments, overseas reforms, and European regulation)affected institutional reform in a selected case study of telecommunications regulation in Britain,France, Germany, and Italy between the 1960s and 2002. The author argues that when differentforms of internationalization are strong and combined, they can overwhelm institutional inertiaand the effects of different national settings to result in rapid change and cross-national conver-gence in market institutions. Hence different varieties of capitalism may endure only when inter-national pressures are low and/or for limited periods of time.

Keywords: internationalization; varieties of capitalism; historical institutionalism; institu-tions; telecommunications

Comparative studies of domestic politics frequently argue that the re-form of national institutions is difficult and that when it occurs, it differs

across countries. Thus, for example, a prominent recent group of studies,

751

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I wish to thank Nigel Bowles, Desmond King, Mathew Evangelista, PeterHall, and two anonymous referees for comments; Maria Kampp and Alexandre Serot forresearch assistance; and the editor of Comparative Political Studies. All views and errors ofcourse remain mine. This article arises from a project on European telecommunications withinthe Economic and Social Research Council’s Future Governance Programme, Project L216 252007, and the Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation, London School of Economics.

COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES, Vol. 37 No. 7, September 2004 751-780DOI: 10.1177/0010414004266868© 2004 Sage Publications

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

“historical institutionalist” work on “varieties of capitalism,” claims thatnational settings strongly condition institutional choices, so industrializednations adopt different reforms to adapt to economic globalization. Theresult is an enduring diversity of forms of capitalism, even in a limitedgeographical area such as Europe.

However, in an internationalized world, there are also powerful cross-national forces that affect decision making within domestic arenas. Theseforces are broader than economic globalization. They can provide impetusfor institutional reform and operate regardless of existing national settings.Hence they may overcome national institutional rigidities to produce changeand convergence across nations.

Using work on varieties of capitalism as its starting point, the present arti-cle examines how three international factors created pressures for institu-tional reform and convergence across four nations despite diverse domesticsettings. It seeks to add to the understanding of varieties of capitalism in threeways. First, it argues that “internationalization” is broader than the economicglobalization identified by the literature on varieties of capitalism. Second, itaids in defining the conditions under which different varieties of capitalismcan persist and those under which cross-national differences are weakened.Finally, it suggests that historical institutionalists should give greater place tothe ways in which international factors affect domestic institutional reform,bringing in the “second image reversed.”

The reform of telecommunications institutions in four European coun-tries—Britain, France, Germany, and Italy—during the late 1980s and 1990sis used as a case study. The four countries have had diverse political and eco-nomic institutional frameworks, and the telecommunications sector has char-acteristics that are extremely propitious for scrutinizing claims made by pro-ponents of varieties of capitalism. On one hand, it is a strategic economicsector with deep institutional roots that has been a key part of the state inEurope. On the other hand, a high level of internationalization developed thattook several forms, not just economic globalization. Thus European telecom-munications offers a case of embedded and diverse national market institu-tions facing strong internationalization.

The article begins by discussing claims that varieties of capitalism persistin the face of internationalization. It then explains the choice of case studyand outlines sectoral institutional developments in the four countries fromthe late 1960s until 2002. Thereafter it looks at how three major interna-tional forces affected domestic decision making over institutional reform.Finally it suggests broader conclusions regarding varieties of capitalism andinternationalization.

752 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

VARIETIES OF CAPITALISM IN THEFACE OF INTERNATIONALIZATION

Historical institutionalist models argue that nations are characterized bylong-established institutional differences arising from factors such as thetiming of industrialization, wars, revolutions, and geographical position(Hall, 1986; Thelen, 1999). They argue that economic “globalization”—driven by technological change, trade liberalization, enormous internationalcapital flows, and declining transport costs—does not lead to institutionalconvergence (Hall & Soskice, 2001a, pp. 54-60). Market structures, rules,and norms vary greatly across nations, for example, concerning public own-ership and privatization, the extent of “deregulation,” the role of the state, andthe power of firms and organized labor. Thus even in a confined and highlyinterdependent area such as Europe, several “varieties” or “models” of capi-talism persist (Albert, 1993; Berger & Dore, 1996; Crouch & Streeck, 1997;Hall & Soskice, 2001b; Hollingsworth & Boyer, 1997; Kitschelt, Lange,Marks, & Stephens, 1999; Rhodes & van Apeldoorn, 1998; Schmidt, 2002;Zysman, 1996). Even if policies and economic performance converge, insti-tutions do not (Boltho, 1996; Boyer, 1996). The national level remains vitalfor market institutions: “So many of the institutional factors conditioning thebehaviour of firms remain nation-specific and depend strongly on statutes orregulations promulgated by nation states” (Hall & Soskice, 2001a, p. 16).

Empirically, several categorizations of capitalisms have been put forward(coordinated market economies vs. liberal market ones, Hall & Soskice,2001a; market, state, and managed capitalisms, Schmidt, 2002; Rhenish vs.liberal economies, Albert, 1993). However, most suggest that Germany hasstrong coordinative institutions that aid cooperation between firms, whereasBritain has a liberal market economy in which the state ensures competition;traditionally, France has had a dirigiste and statist structure but may now liebetween liberal and coordinated market economies (Hall & Soskice, 2001a;Hancké, 2001; Hayward, 1995; Schmidt, 1996, 2002; Wood, 2001). Italy isoften seen as an economy with widespread state intervention matched bygreat fragmentation and politicization (cf. Cassese, 2000, chap. 2; Locke,1995, chap. 2). Despite increased international pressures, differences amongthe four countries are claimed to have persisted into the 1990s.

Why do inherited cross-national differences in capitalism continue in theface of internationalization? Earlier institutionalist works argued that be-cause domestic arenas institutions are supported by coalitions of actors whohave strong interests in their continuation, national reform is difficult, beingconfined to wars; revolutions; and/or slow, incremental movement (cf. Hall,1986). More recently, studies of varieties of capitalism have argued that in the

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 753

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

face of economic and financial internationalization, institutional change doesoccur but differs greatly across nations (Hall & Soskice 2001a, 2001b). Sev-eral explanations are given for diverse national reform paths. Existing set-tings condition the relative advantages of different reform strategies for firmsand policy makers (Hall & Soskice, 2001a): “Much of the adjustment processwill be oriented towards the institutional recreation of comparative advan-tage” (p. 63), and hence “nations often prosper, not by becoming more simi-lar, but by building on their institutional differences” (p. 60). Thus becauseof existing domestic institutional settings, political dynamics differ acrosscountries, resulting in diverse adaptation strategies. Confronted with global-ization, liberal market economies tend to choose deregulation (policies thatremove obstacles to competition, expand the role of markets, and increasemarket incentives), which advantages their firms, whereas nations with co-ordinated economies tend to introduce less deregulation because there isless support for liberalization and attempts to weaken trade unions (Hall &Soskice, 2001a). In a similar vein, Vivien Schmidt (2002) argues that theeffects of globalization and Europeanization are mediated by national cir-cumstances: economic vulnerability, national legacies, and the preferencesand reform capacities of policy makers. “Path dependence” explanationssuggest that once set on a particular path, which may occur because of anaccident of timing or sequence, a nation continues along its specific tra-jectory, as self-reinforcing processes shape actors’ interests and choices(Pierson, 2000). A further set of explanations claims that domestic institu-tions affect policy learning, so the lessons drawn from the experiences ofother nations and the diffusion of ideas vary across countries (Hall, 1989;Hansen & King, 2001; King, 1992; Reuschmayer & Skocpol, 1996).

All these explanations posit that domestic settings and past reforms lead tonationally specific paths of institutional change in response to pressures forchange from globalization. Thus, for instance, it is argued that much greatercompetition has been introduced in liberal market economies such as Britainthan in coordinated ones such as Germany (Hall & Soskice, 2001a; Wood,2001). France’s strategy has been to ensure internationally competitivefirms through cooperation between its business and state elites (Hancké,2001). Italy has responded to international pressures with disaggregationof the state, technocratic management, and much greater use of regulation(Cassese, 2000; Locke, 1995).

Historical institutionalist studies of varieties of capitalism have manyimportant strengths. They investigate domestic politics, which is essentialbecause national institutional change involves debates and decisions byactors within countries. They insist on examining the behavior of specificactors to identify causal mechanisms. Recent work on varieties of capitalism

754 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

explicitly analyzes change and includes the interests and strategies of partic-ular actors. Studies are usually comparative across countries and/or coversubstantial time periods, providing empirical richness. At the same time,their claims that national settings block or mediate international factors meritcritical scrutiny. Three aspects are examined here: the treatment of the do-mestic effects of “international pressures,” the conception of those pressures,and empirical evidence.

Historical institutionalists tend to treat international factors as externalpressures that are mediated by domestic settings. They concentrate on hownational institutions operate differently to produce diverse national decisionsrather than examining directly the effects of international factors on domesticdecision making. However, this may downplay or sometimes obscure howinternational factors can influence decision making within domestic arenas,including decisions about transforming national institutional settings. Workin the second image reversed tradition shows that international developmentscan redistribute power within domestic politics and affect policy making(Gourevitch, 1978; Katzenstein, 1978; Keohane & Milner, 1996; for a re-view, see Evangelista, 1997). Internationalization can affect actors’ incen-tives, institutional preferences, and strategies by altering the constraints andopportunities faced by actors within domestic settings (Deeg & Lütz, 2000;Keohane & Milner, 1996). Thus the effects of international factors withindomestic politics must be studied directly.1

A second issue is that work on varieties of capitalism often treats interna-tionalization as economic globalization (see, e.g., Hall & Soskice, 2001a).Although this is undoubtedly an essential form of internationalization, sev-eral other international forces exist, for instance, increased supranationalregulation or reforms in one country that affect markets, create political pres-sures, and offer examples for other nations.2 It is valuable to consider differ-ent forms of internationalization concurrently, especially considering thatthey may be associated, and their combined impact is likely to be more pow-erful than that of a single form. This leads to the third line of scrutiny: cases to

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 755

1. At present, scholars who have examined the effects of international factors on domesticdecision making have also focused on how domestic political structures, such as numbers of vetoplayers, mediate national responses to international events rather than how they themselves arealtered (see, e.g., Hallerberg & Basinger, 1998; Katzenstein, 1978); hence they run parallel tohistorical institutionalist emphases on national refraction of international factors.

2. Paradoxically, as noted, much historical institutional work has recognized the importanceof ideas traveling across countries, albeit that it has focused on differences in how nations accept,interpret, and apply them (see, e.g., Hall, 1989; Hansen & King, 2001). Yet such work has beengiven little place in studies of international pressures in the literature on varieties of capitalism atpresent.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

test empirically contentions of varieties of capitalism. As is inevitable in anew approach, studies thus far have frequently been broad. Most have cov-ered entire countries and/or have examined a mixture of institutional reform,policy making, and the strategies of firms (Hall & Soskice, 2001b). The polit-ical process of institutional reform, including actors’ strategies, coalitions,and conflicts, needs to be analyzed in detail, especially across several coun-tries in “hard” cases for varieties of capitalism.

The present article pursues these three issues. With respect to the first, itstudies how international factors affected domestic decision making over thereform of market institutions. It analyses how they affected pressures andopportunities for actors and the strategies and coalitions of those actors toconsider whether they led policy makers to make similar choices in differentdomestic settings or whether they were refracted and hence were met withdiverse responses.

In considering different forms of internationalization, the analysis ex-tends beyond economic globalization by looking at the domestic impacts ofthree pressures for change: transnational technological and economic devel-opments, overseas reforms, and European Community (EC) regulation. Eachfactor is inspired by a general literature that can be used to scrutinize claimsof enduring cross-national institutional differences in markets.

Work on globalization and internationalization through economic inte-gration suggests that the weakening of national boundaries for markets andfirms constrains domestic decision making and alters the balance of incen-tives and the distribution of power within a nation (Deeg & Lütz, 2000;Garrett & Lange, 1995; Held, McGrew, Goldblatt, & Perraton, 1999;Keohane & Milner, 1996). If economic integration leads actors in domesticarenas to choose similar institutional reforms, it would challenge argumentsin the literature on varieties of capitalism that nations maintain different insti-tutional arrangements despite globalization. In telecommunications,extremely powerful transnational technological and economic developmentsoffer a good example of economic globalization. The second internationalfactor analyzed arises from the growing literature on cross-national policytransfer (cf. Bennett, 1991; Dolowitz & Marsh, 2000; Rose, 1993). Institu-tional decisions in one country can influence those in other nations throughcross-national learning, imposition, or “regulatory competition.” This articlelooks at how telecommunications reforms in two major nations, the UnitedStates and Britain, had repercussions for countries in continental Europe.The third factor examined is the effects of international regimes, specificallyEC regulation, on domestic politics. Recent studies of “Europeanization”suggest that the “institutionalization of Europe,” particularly the develop-ment of European Union (EU) legal frameworks, creates adaptation pres-

756 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

sures on national institutions (Green Cowles, Caporaso, & Risse, 2001;Stone Sweet, Sandholtz, & Fligstein, 2001). Work on varieties of capitalismhas either given relatively little attention to such regulation or underlined hownational factors mediate its domestic impacts (Hall & Soskice, 2001b;Schmidt, 2002). Yet an alternative view is that strong and sustained suprana-tional regulation can lead domestic policy makers to make similar choices.This article therefore considers how EC regulation in telecommunicationsaffected national institutional reform.

With respect to the third issue (empirical evidence), the article offers adetailed analysis of institutional reform in telecommunications in Britain,France, Germany, and Italy between the late 1960s and 2002. The four coun-tries have been used to exemplify different varieties of capitalism. The tele-communications sector is economically and politically important. Moreover,its features offer a valuable case for testing the persistence of varieties of cap-italism in the face of internationalization in two senses. On one hand, it hascharacteristics that, according to historical institutionalism, militate againstreform and convergence. It has been subject to continuous and prolongedregulation, often in forms that reflected cross-national differences set out bythe literature on varieties of capitalism. For decades, reforms were blocked,and when they were introduced, they differed among the four countries.Hence if international forces can lead to change and/or convergence in adomain that exemplifies varieties of capitalism, the outcome would underlinethe importance of internationalization for national institutional reform. In-deed, a fortiori, similar powerful international forces would then be expectedto be even more important in other domains in which domestic institutionsare less deeply rooted. Moreover, given the strength of international forces intelecommunications, the ways in which they affect domestic reform shouldbe particularly visible. On the other hand, the sector offers a hard case forclaims of enduring varieties of capitalism because of the degree of interna-tionalization. Hence if diversity of national institutions persists, one wouldexpect differences to exist and continue in other domains with deep historicalroots but subject to less internationalization, thereby supporting claims forvarieties of capitalism.

This article uses two methods. First, it compares institutional reform pathsand outcomes across countries between the late 1960s and 2002. Second,however, it analyzes how, within domestic arenas, the three international fac-tors influenced the strategies of existing actors, caused new actors to enterinstitutional reform debates, and altered the distribution of resources amongactors. Thus in studying the second image reversed, it seeks to maintain sev-eral of the virtues of historical institutionalist approaches, notably the focus

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 757

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

on the decisions of specific actors within national settings, the use of cross-national comparisons, and the study of significant time periods.

“Institutions” are defined as the formal and informal rules and norms thatstructure conduct (cf. Hall, 1986); the focus is on sectoral institutions. “Inter-national factors” are defined as factors that apply cross-nationally and thatare beyond the control of policy makers in individual countries (at least forthe countries and time period studied) (cf. Frieden & Rogowski, 1996,pp. 26-27). Internationalization is the increasing strength of internationalfactors. “Convergence” involves countries becoming more alike over a de-fined time period but not the disappearance of all differences.

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE INWEST EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS:

STABILITY, DIFFERENCE, AND THENRAPID CHANGE AND CONVERGENCE

Telecommunications institutions in Britain, France, Germany, and Italypresent a puzzle for historical institutionalist claims of differing varieties ofcapitalism. Until the late 1980s, their evolution seemed to bear out stronglyclaims of inertia and diverse national reform paths. Yet suddenly, during thefollowing 10 years, comprehensive reforms resulted in remarkable and swiftconvergence across the four nations. This section sets out the pattern of insti-tutional reform, focusing on three key structural features: the organizationalposition of the incumbent supplier, monopoly versus the liberalization ofsupply, and the allocation of regulatory powers.

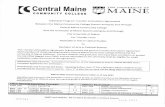

In the 1960s, the institutional features of telecommunications in Europeancountries were long standing, often dating back to the early 20th century(Foreman-Peck & Müller, 1988; Noam, 1992). State-owned public telecom-munications operators (PTOs) held monopolies over almost all telecommu-nications services and networks. In Britain, France, and Germany, the PTOswere the Post Office, Direction générale des télécommunications (DGT),and the Deutsche Bundespost (DBP), respectively. They were part of the civilservice and linked with postal services, being units within post, telegraph andtelecommunications ministries. Italy represented a partial exception in thatseveral PTOs existed; the largest, l’Azienda di Stato per Servici Telefonici(ASST), was part of the civil service, but others were majority state-ownedcompanies (Table 1).

Behind the institutional framework lay powerful, entrenched coalitions ofinterests: governments, PTO managements, postal services, private equip-ment manufacturers, PTO employees and trade unions, and political parties

758 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

759

Tabl

e 1

Inst

itut

iona

l Fra

mew

orks

in B

rita

in, F

ranc

e, G

erm

any,

and

Ita

ly in

the

1960

s

Bri

tain

Fran

ceW

est G

erm

any

Ital

y

PTO

Post

Off

ice

DG

TD

BP

ASS

T, S

TE

T (

hold

ing

com

pany

for

othe

r PT

Os:

SIP

,Te

lesp

azio

)O

rgan

izat

iona

l sta

tus

Gov

ernm

ent d

epar

tmen

t,G

over

nmen

t dep

artm

ent,

Gov

ernm

ent d

epar

tmen

t,A

SST:

gov

ernm

ent d

epar

tmen

t,lin

ked

to p

osta

l ser

vice

slin

ked

to p

osta

l ser

vice

s;lin

ked

to p

osta

l ser

vice

slin

ked

to p

osta

l ser

vice

s;a

few

pri

vate

law

STE

T: p

ublic

cor

pora

tion

subs

idia

ries

Com

petit

ion

No,

exc

ept f

or s

peci

aliz

edN

o, e

xcep

t for

som

e te

rmin

als

No,

exc

ept f

or s

peci

aliz

edN

o, e

xcep

t for

spe

cial

ized

term

inal

ste

rmin

als

term

inal

sR

egul

ator

Gov

ernm

ent

Gov

ernm

ent

Gov

ernm

ent

Gov

ernm

ent

Nor

ms

gove

rnin

gB

urea

ucra

tic f

or s

uppl

y:B

urea

ucra

tic f

or s

uppl

yB

urea

ucra

tic f

or s

uppl

yB

urea

ucra

tic w

ith p

oliti

cal

polic

yat

tem

pts

at m

ore

part

y“b

usin

ess”

cri

teri

a

Not

e:PT

O=

publ

icte

leco

mm

unic

atio

nsop

erat

or;D

GT

=D

irec

tion

géné

rale

des

télé

com

mun

icat

ions

;DB

P=

Deu

tsch

eB

unde

spos

t;A

SST

=l’

Azi

enda

diSt

ato

per

Serv

ici T

elef

onic

i; ST

ET

= S

ocie

tà T

orin

ese

Ese

rciz

i Tel

efon

ici;

SIP

= S

ocie

tà I

talia

na p

er l’

Ese

rciz

io T

elef

onic

a.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

(Cohen, 1992; Pitt, 1980; Foreman-Peck & Müller, 1988; Noam, 1992;Richeri, 1985; Werle, 1999). Each enjoyed benefits from the institutionalarrangements. Governments used PTOs as policy instruments for their mac-roeconomic and industrial strategies. PTOs subsidized postal services andprovided orders for privately owned “national champion” equipment manu-facturers. Moreover, PTO tariffs indirectly redistributed income: Long-dis-tance communications subsidized local calls and the cost of access, which ledto the cross-subsidization of most residential users by business users. Thecounterparts to these functions were that PTOs were protected from marketforces: They enjoyed wide monopolies, they were state-owned, and theirstaff members were mostly civil servants.

From the 1960s onward, pressures for change developed, notably dissatis-faction with PTO performance, increasing demand, and ever greater diver-gence between the postal and telecommunications sectors (Foreman-Peck &Müller, 1988). However, experiences of institutional reforms until the late1980s appeared to confirm historical institutionalist claims. Changes wereslow and difficult and, when introduced, differed greatly among the fourcountries.

The earliest and most far-reaching modifications took place in Britain,but only after lengthy discussions and widespread perceptions of the PostOffice’s failings. In 1969, the Post Office was removed from the civil service,becoming a public corporation with its own legal identity. In 1981, BritishTelecommunications (BT) was created, thereby separating telecommuni-cations and postal services. However, in the 1980s, more radical and rapidchange took place. In 1984, BT was privatized through the sale of a majoritystake, and a new semi-independent sectoral regulator was created, the Officeof Telecommunications (Oftel). Privatization required a new coalition com-posed of BT’s senior management and the Conservative government led byMargaret Thatcher and a fierce struggle against trade unions and oppositionpolitical parties. BT’s monopoly was also ended in the 1980s, with liberaliza-tion being led by Oftel, with support from ministers (Thatcher, 1999, chap. 7;Zahariadis, 1992).

In contrast, attempts in France to alter the organizational position of DGTaway from its civil service status failed because of strong opposition fromtrade unions and employees (Thatcher, 1999; Zahariadis, 1992). Only verylimited liberalization was introduced, no powerful regulator for telecom-munications was established, and privatization was not attempted, even un-der the rightist government of 1986 to 1988. Instead, a strategy of grandsprojets—massive investment projects with close cooperation between publicand private sectors financed by specially created, off-budget financial instru-ments—was pursued (Cohen, 1992). In Germany, DBP was not reformed;

760 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

limited liberalization was introduced in the 1980s, but the core DBP monop-oly was left untouched. Changes faced a determined coalition of DBP tradeunions, together with parts of the political Left, equipment suppliers, and onliberalization the DBP management (Grande, 1989, pp. 206-237; Schmidt,1991; Schneider & Werle, 1991; Werle, 1990, pp. 307-345). In Italy, the frag-mented structure of its PTOs was widely seen as inefficient, but reformsremained blocked by unstable governments and political parties that sharedout the various PTOs for use as sources of finance and jobs (Richeri, 1985).Thus by the late 1980s, considerable differences had developed among thefour countries both in formal structures and norms governing policy. Theseare set out in Table 2.

The cross-national differences corresponded to the categorizations pro-posed by the literature on varieties of capitalism (Hayward, 1995; Kitscheltet al., 1999; Schmidt, 2002). Britain appeared to be following a “liberal” pathbased on competition; private ownership; and a strong, semi-independentregulator. France conformed to the dirigiste model, with its “entrepreneurstate” undertaking planned government action and monopoly supply. Ger-many lay in between, having state monopolies but lacking French planningand state-led expansion. Finally, reforms in Italy were blocked by predatorypolitical parties.

However, in the 1990s, a very different pattern of institutional reformfrom that of the 1970s and 1980s took place. Rapid and comprehensive insti-tutional changes were introduced in France, Germany, and Italy at similartimes. They involved two steps. First, PTOs were separated from postal ser-vices and removed from the civil service to become publicly owned entitieswith their own legal identities (i.e., forms similar to BT in Britain after 1981).In Germany, Telekom (later renamed Deutsche Telekom) was created in1989 and 1990, while in France, DGT (renamed France Télécom) became atype of public corporation in 1990. In Italy, ASST was removed from thePosts and Telecommunications Ministry in 1992 and merged with the othervarious PTOs to become Telecom Italia between 1994 and 1996.

The second phase of reform was the privatization of PTOs, large-scale lib-eralization, and the creation of semi-independent regulators. Thus a majorityof Deutsche Telekom shares were sold between 1996 and 2002 (58% by2002). A new semi-independent sectoral regulator, Regulierungsbehörde fürTelekommunikation und Post was established in 1998 (cf. Coen, Héritier, &Böllhoff, 2002). France Télécom was partially privatized in 1997; by 2002,the state owned 55% of shares. A semi-independent regulatory authority,Autorité de régulation des télécommunications, was created in 1997. Sur-prisingly, given the past history of fragmentation and inertia, the greatestreforms were seen in Italy. The vast majority of Telecom Italia shares were

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 761

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

762

Tabl

e 2

Inst

itut

iona

l Fra

mew

orks

in 1

989

Bri

tain

Fran

ceW

est G

erm

any

Ital

y

PTO

sB

T; M

ercu

ryFr

ance

Tél

écom

DB

PA

SST,

ST

ET

(SI

P, T

eles

pazi

o,et

c.)

Stat

usM

ajor

ity p

riva

te o

wne

dG

over

nmen

t dep

artm

ent,

Gov

ernm

ent d

epar

tmen

t,A

SST:

gov

ernm

ent d

epar

tmen

t,si

nce

1984

linke

d to

pos

tal s

ervi

ces

linke

d to

pos

tal s

ervi

ces

linke

d to

pos

tal s

ervi

ces;

STE

T: p

ublic

cor

pora

tion

Com

petit

ion

Duo

poly

in p

ublic

voi

ceC

ompe

titio

n in

sev

eral

Com

petit

ion

in s

ever

alV

ery

limite

d co

mpe

titio

nte

leph

ony

and

netw

orks

;ad

vanc

ed s

ervi

ces

and

adva

nced

ser

vice

s an

din

term

inal

sco

mpe

titio

n in

term

inal

term

inal

equ

ipm

ent

term

inal

equ

ipm

ent

equi

pmen

t and

adv

ance

dse

rvic

esR

egul

ator

Oft

el, g

over

nmen

t,G

over

nmen

tG

over

nmen

tG

over

nmen

tM

onop

olie

s an

dM

erge

rs C

omm

issi

onPr

evai

ling

norm

sC

ompe

titio

n to

be

exte

nded

Gra

nds

proj

ets

Bur

eauc

racy

Bur

eauc

racy

and

par

typo

litic

izat

ion

Not

e:PT

O=

publ

icte

leco

mm

unic

atio

nsop

erat

or;B

T=

Bri

tish

Tele

com

mun

icat

ions

;DB

P=

Deu

tsch

eB

unde

spos

t;A

SST

=l’

Azi

enda

diSt

ato

perS

ervi

ciTe

lefo

nici

; ST

ET

= S

ocie

tà T

orin

ese

Ese

rciz

i Tel

efon

ici;

SIP

= S

ocie

tà I

talia

na p

er l’

Ese

rciz

io T

elef

onic

a.; O

ftel

= O

ffic

e of

Tel

ecom

mun

icat

ions

.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

sold in 1997, and a new semi-independent regulator was established in 1998,which covered both telecommunications and broadcasting, l’Autorità per leGaranzie Nelle Communicazioni. Britain continued on its path of privatiza-tion, as remaining government shares in BT were sold in 1991 and 1993. Inall four countries, the liberalization of supply was introduced across the sec-tor, including mobile phones, public voice telephony, and the infrastructure.

The reforms in France, Germany, and Italy were often highly controver-sial, involving long negotiations and sometimes sharp conflicts (Natalicchi,2001, pp. 117-179; Schneider, 2001b, pp. 241-284; Stehmann, 1995,pp. 178-224; Thatcher, 1999, pp. 155-163; Werle, 1999, pp. 110-113). Theyarose because the strategies of key policy actors altered. Governments pro-moted or at least accepted privatization, liberalization, and delegation to newsemi-independent regulatory bodies. The new strategies were adopted evenby administrations on the Left or Center Left, such as the Jospin governmentin France after 1997 or the Prodi and d’Alema governments in Italy after1995. PTO managements pressed for privatization and sought to abandon thepast behavior of civil service monopolists, adopt a commercial approach tomeeting user needs, and form international alliances (Chevallier, 1996;Rendini, 1995; Locatelli, 1996; Martino, 1996; Roulet, 1994; Schmidt,1996). Users and new entrants pressed for liberalization. New reform coali-tions were formed, composed of PTO managements, governments, newentrants, and sometimes users; they were joined by parts of the “nationalist”Left and Right. Opponents of change became limited to PTO trade unionsand employees and parts of the political Left.

The result of the reforms was cross-national institutional convergence. Bythe late 1990s all four countries shared key institutional features: the privat-ization of incumbent PTOs, the full liberalization of the sector, the creation ofnew semi-independent regulatory authorities, and the spread of new norms offair and effective competition. Although some differences remained, the newinstitutional features represented a strong movement in the same directionand a lessening of differences; it stood in stark contrast to the 1970s and1980s (Table 3).

INTERNATIONAL FORCES ANDDOMESTIC INSTITUTIONAL REFORM

Until the late 1980s, institutional outcomes seemed to bear out stronglyhistorical institutionalist claims that change is very difficult and/or differsacross countries. In addition, sectoral institutional patterns in Britain, France,Germany, and Italy matched those described by the literature on varieties of

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 763

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

764

Tabl

e 3

Inst

itut

iona

l Fra

mew

orks

in 2

002

Bri

tain

Fran

ceG

erm

any

Ital

y

PTO

Seve

ral c

able

com

pani

es,

Seve

ral,

but F

ranc

eSe

vera

l; la

rges

t is

Deu

tsch

eSe

vera

l; Te

leco

m I

talia

stil

lB

T, r

esel

lers

Télé

com

dom

inan

tTe

leko

mdo

min

ant

Org

aniz

atio

n st

atus

of

100%

pri

vate

55%

pub

lic s

hare

42%

pub

lic s

hare

Alm

ost e

ntir

ely

priv

ate

hist

oric

incu

mbe

ntC

ompe

titio

nPe

rmitt

ed in

who

le s

ecto

rPe

rmitt

ed in

who

le s

ecto

rPe

rmitt

ed in

who

le s

ecto

rPe

rmitt

ed in

who

le s

ecto

rR

egul

ator

Oft

el, g

over

nmen

t,A

RT,

gov

ernm

ent,

Con

seil

Reg

ulie

rung

sbeh

örde

für

Post

, gov

ernm

ent,

Com

petit

ion

Com

mis

sion

,de

la C

oncu

rren

ceTe

leko

mm

unik

atio

n un

dA

GC

OM

, gov

ernm

ent

OFT

Bun

desK

arte

llam

ptD

omin

ant n

orm

sFa

ir a

nd e

ffec

tive

Exp

andi

ng c

ompe

titio

n,Fa

ir a

nd e

ffec

tive

com

petit

ion

Exp

andi

ng c

ompe

titio

nco

mpe

titio

nal

thou

gh s

ome

deba

te o

npr

otec

tion

of P

TO

s

Not

e:PT

O=

publ

icte

leco

mm

unic

atio

nsop

erat

or;B

T=

Bri

tish

Tele

com

mun

icat

ions

;Oft

el=

Off

ice

ofTe

leco

mm

unic

atio

ns;O

FT=

Off

ice

ofFa

irT

radi

ng;

AR

T =

Aut

orité

de

régu

latio

n de

s té

léco

mm

unic

atio

ns; A

GC

OM

= l’

Aut

orità

per

le G

aran

zie

Nel

le C

omm

unic

azio

ni.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

capitalism. Yet thereafter, rapid change and convergence change took place,as new reform coalitions were formed. Convergence and the similar timing ofreform among three of the four countries suggest that powerful commoninternational forces were at work that overcame the effects of differences indomestic settings across countries. However, such forces cannot just be pre-sumed: They must be linked to the strategies of actors within domesticarenas.

This section therefore examines three major international forces forchange—transnational technological and economic developments, overseasreforms, and supranational regulation—that became increasingly powerfulover the 1980s and the 1990s. Each international factor is very briefly set outbefore looking at how it affected the domestic politics of institutional reform,specifically, how it contributed to the separation of postal and telecommuni-cations services, PTOs becoming forms of public corporations, privatization,and the creation of semi-independent sectoral regulators. The argument is notthat the three international forces were the sole cause of institutional changeand convergence but rather that they significantly aided them.

TRANSNATIONAL TECHNOLOGICAL ANDECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

Policy makers in Western Europe faced sweeping technological develop-ments in telecommunications that began in the late 1960s but greatly acceler-ated over the 1980s and 1990s. The changes involved the application of com-puting (e.g., the digitalization of switching and transmission), new methodsof transmission such as optical fiber cables and satellites, and the appearanceof new services (cf. Stehmann, 1995, pp. 12-38; Thatcher, 1999, pp. 47-70).They were transnational, being largely beyond the control of policy makersin European countries.

Technological and economic developments transformed the nature of thetelecommunications market and thereby put pressure on traditional institu-tional arrangements in Europe. They altered costs and services, greatlyweakening “natural monopolies,” a fundamental pillar of public ownershipand monopolies for PTOs (Stehmann, 1995, pp. 43-85; Ungerer & Costello,1988, pp. 35-82). Thus, for instance, the costs of establishing competing net-works (fixed line, mobile, and satellite) fell, and new services developed thatwere clearly not natural monopolies, such as advanced data services. Byoffering much lower costs and greatly improved quality, the new technolo-gies made existing equipment technically and economically obsolete. Butthey often required massive capital investment by PTOs. At the same time,the remarkable expansion of telecommunications and related services

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 765

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

appeared to create tremendous opportunities for profit. The value of PTOsrose: From being dull utilities, they became potentially lucrative investments,especially in the “new technology” stock market boom of the 1990s. Finally,the interests at stake widened: Telecommunications became economicallystrategic to many industries, such as banking, tourism, and even manufactur-ing; the boundaries between telecommunications and the computing andaudiovisual sectors weakened.

Technological and economic developments reduced the advantages oftraditional institutional arrangements—PTO monopolies, public ownership,and direct government regulation—for existing sectoral actors, notably in-cumbent PTOs and governments. They also contributed to new actors be-coming involved in discussions of reform and weakened economic argu-ments for PTO monopolies and public ownership.

From the 1980s onward, PTO managements accepted that competitionwas inevitable as entry costs fell, especially in fast-growing markets such asmobile services and advanced services combining telecommunications andcomputing. By the mid-1990s, BT, France Télécom, and Deutsche Telekomdid not even oppose legislation ending their monopolies (British Telecom,1991; France Télécom, 1995; Telekom Fordert, 1992; Postminister, 1992;Thorein, 1997, p. 40). Instead, incumbents began to prepare for liberaliza-tion. This involved rebalancing tariffs to bring them closer to costs; increas-ing investment; reducing costs (labor and subsidies to governments andpostal services); expanding operations in newer, growth markets; and form-ing international alliances (Gassot, Pouillot, & Balcon, 2000; Graack, 1996).

To pursue their new strategies, PTO managements linked accepting theloss of their monopolies to reforms that would increase their autonomy fromgovernments. They argued that the constraints of public sector ownership,especially within the civil service, inhibited them from competing effec-tively, investing, and reducing costs. In Britain, the massive sums needed tomodernize the system made privatization attractive to BT’s management,which sought much greater freedom from treasury control over its spending(Hills, 1986, p.124). In Germany, raising money for investment also becameparticularly significant in the 1990s because the costs of modernization in theformer East Germany were very large (Robischon, 1999, pp. 213-224;Thorein, 1997, p. 42; Werle, 1999). Even France Télécom’s strategy was topress hard for organizational reform (Thatcher, 1999, p. 160). It faced leviesto pay for postal services or general industrial policy tasks, and most of itsemployees were civil servants with many legal rights. Its head, MarcelRoulet, linked the acceptance of a new liberalization law to the alteration ofits organizational position. The issue became so heated that his replacementresigned after only 10 days in 1995, because of a failure to receive sufficient

766 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

government assurances over a new organizational status with greater auton-omy (Monnot, 1995). The conflict was resolved by the partial privatization ofFrance Télécom in 1997.

Historically, governments had gained advantages from being the owners,suppliers, and direct regulators of telecommunications. PTOs had performedindustrial policy and political functions such as subsidizing voters, nationalmanufacturers, and postal services. However, increased competition and theheavy investment needs of PTOs weakened these functions. Liberalizationand changes in costs made it more difficult for PTOs to cross-subsidizegroups of users, and tariff rebalancing (to reflect new cost structures and lib-eralization) was unpopular with domestic users and small businesses whofaced higher tariffs for certain services (access and local calls) but gained lessthan large users from lower tariffs for long-distance ones (Mansell, 1990).Higher short-term investment was needed, increasing state deficits. At thesame time, lower costs and new services promised higher long-term profits.The reduced advantages of public ownership and higher values of PTOsmade privatization a tempting option for cash-strapped governments, and inall four countries, sales of PTO shares were used to reduce budget deficitsand debt.

Liberalization and privatization also made the delegation of “unsexy” anddifficult regulatory matters to independent agencies attractive to govern-ments. The latter faced increased pressures to achieve greater “credible com-mitment” in the eyes of investors to sell PTOs and attract inward capital. Gov-ernments also faced pressures from incumbents, new entrants, and users,who had different and often conflicting interests. Moreover, as competitiondeveloped, policy makers had to deal with arcane technical issues, such assetting interconnection terms, which offered few evident political advan-tages. Thus in Britain, Oftel was created in part to reassure investors in BTthat political “interference” would not compromise the company’s profitabil-ity and to balance the different interests of consumers and suppliers in a mar-ket characterized by a dominant supplier (Thatcher, 1999, p. 147). Othercountries equally saw the advantages of delegating regulation to new bodies,and the need for semi-independent regulators was widely accepted by the1990s.

Technological and economic changes contributed to new actors enteringdomestic debates on institutional reform. These actors broke open previouslyclosed policy communities and lobbied governments for liberalization and“fair regulation.” As information technology and broadcasting convergedwith telecommunications, politically powerful companies from these sec-tors wished to enter the expanding telecommunications market; exam-ples included Compagnie Générale des Eaux (CGE) in France; Veba and

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 767

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Mannesman in Germany; and Olivetti, Fiat, and Mediaset in Italy. Largebusiness users that were increasingly dependent on high-quality telecommu-nications services also became active, especially when faced with high PTOtariffs for advanced services and inability to meet demand; thus, for example,in Italy, banks and large industrial companies such as Olivetti and Fiat lob-bied for reform (Foreman-Peck & Müller, 1988; Hills 1986, p. 90;Humphreys, 1992, p. 123).

The new technological and economic features of telecommunicationsweakened the rationales used for traditional institutional frameworks. Argu-ments that public monopolies were needed to avoid private exploitation of anatural monopoly were challenged. Similarly, the “public service” functions,notably of cross-subsidizing users, were threatened by competition. In con-trast, supporters of reform argued that technological and economic develop-ments made liberalization and privatization desirable, if not inevitable (forFrance, see Dandelot, 1993; Larcher, 1996).

OVERSEAS REFORMS

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the U.S. telecommunications marketwas greatly altered: AT&T’s monopoly was reduced, new entrants emerged(e.g., MCI and Sprint), and then AT&T was broken up in 1984 (cf. Crandall,1991). Within Europe, Britain introduced its reforms during the 1980s, nota-bly the privatization of BT and liberalization. These reforms created pres-sures and opportunities for actors within continental European countries. Onone hand, they appeared to offer remarkable expansion opportunities forEuropean PTOs, especially considering that the United States represented45% to 50% of the world market. On the other hand, they represented a threatto countries and PTOs that failed to follow suit. Aggressive American PTOsemerged, both the “baby Bells” and new companies such as WorldCom,competing for customers across the world. British policy makers sought toopen up European markets and gain a “first mover advantage” for its pri-vatized national champion, BT, and engaged in regulatory competition inEurope to attract inward investment and telecommunications “hubs” throughits liberal regulatory regime (Cawson, Morgan, Webber, Holmes, & Stevens,1990, pp. 93-95, 114, 202-203).

Faced with new market opportunities and challenges from overseas, in-cumbent PTOs and governments in France, Germany, and Italy adopted atwo-pronged strategy. Each prong included institutional reform, notablygreater autonomy for PTOs through privatization. First, they sought to pre-pare for competition from overseas firms in their domestic markets. Thismeant not only tariff rebalancing, investment, and improved quality but also

768 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

emulating Britain. Continental European policy makers saw Britain as a dan-gerous competitor, thanks to liberalization, its policy of attracting large mul-tinational telecommunications users, and BT’s capacity as a privately ownedcompany to expand abroad (cf. Dandelot, 1993; Locatelli, 1996; Larcher,1993; Stehmann, 1995, pp. 212-213). The management of incumbent Euro-pean PTOs looked at the example of BT and realized that privatization andliberalization did not weaken PTOs but indeed often strengthened them.They became aware of the advantages of privatization, including greaterautonomy from elected politicians and trade unions, avoiding being used as“cash cows” for governments, and higher rewards for top managers (cf.Roulet, 1994).

The second prong was international expansion to transform incumbentPTOs from national champions into international champions. PTOs soughtto form alliances, particularly with United States–based operators, hoping tocapture a share of the liberalizing American market. Examples included thealliances between France Télécom, Deutsche Telekom, and Sprint; betweenBT and MCI; and then between BT and AT&T (cf. Cowhey & Aronson,1993; Gassot et al., 2000; Graack, 1996).3 However, forming alliances rap-idly became linked to domestic institutional reform, both directly and indi-rectly. Direct linkage came from overseas demands for reciprocity. Thus inthe 1990s, U.S. regulatory authorities made the approval of FranceTélécom’s and Deutsche Telekom’s purchase of a stake in the Americanoperator Sprint conditional on the liberalization of French and German mar-kets (Nexon, 1994; Petit, 1994; Barroux, 1995; Der Postminister, 1995).Thereafter, obtaining U.S. approval for a full alliance by the two operatorswith Sprint became enmeshed in France Télécom’s privatization (Pressionsaméricaines, 1995). Even forming alliances within Europe had repercussionsfor domestic reform, because the more autonomous partners wished to marryequal rather than politically controlled entities. Hence in forming the alliancebetween France Télécom and Deutsche Telekom, German policy makersdemanded partial privatization of the former (Monnnot, 1993; Petit, 1993).The indirect linkage of alliances to institutional reform came as internation-alization strategies by PTOs altered domestic debates. Thus, for example,French governments of the Left and Right in the 1990s faced constant argu-ments that France Télécom’s statut needed to be altered to allow it to interna-tionalize, and when the American operator MCI chose BT rather than FranceTélécom as its international partner, the head of the latter blamed public own-

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 769

3. In retrospect, international expansion was limited, and the alliances were unsuccessful,with most breaking up after losses, but the key point here is that at the time, they were eagerly pur-sued by policy makers and PTOs and offered good arguments in domestic institutional reformdebates.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

ership (Chevallier, 1996; Dandelot, 1993; Larcher, 1993, 1996; Roulet,1994).

Overseas reforms also contributed to new actors becoming more active indomestic debates. The “Bell settlement” created American PTOs that wereeager to expand abroad (notably AT&T and the new baby Bells). They andAmerican public officials lobbied governments (especially in Britain andGermany) for liberalization and fair regulation (Schmidt, 1991; cf. Hills,1986). After privatization, BT also began to expand in continental Europe,forming alliances in France (CGE/Vivendi), Germany (Viag), and Italy(Albacom); with its new allies, it pressed for regulatory reforms based on theprinciple of “fair competition.”

Overseas reforms weakened coalitions for the institutional status quo.Opponents of change were confronted with examples of apparently success-ful liberalization and privatization. Many of the nationalist members of anti-reform coalitions ceased to reject change when they believed that publicownership no longer ensured powerful national industrial championsbecause it prevented them from expanding internationally and meeting over-seas competition. Thus in France, the Jospin government, which includedthe most determined party opponents of privatization, the Communist Party,justified its reversal in 1997 of electoral promises made a few months earlierto abandon the sale of France Télécom by the need for a cross-holding withDeutsche Telekom and to allow France Télécom to meet international com-petition (Delebarre, 1997; Escande & Marti, 1997). The framework of debatethus altered, because overseas experiences showed, or were claimed to show,the benefits of privatization, liberalization, and regulation by newindependent authorities.

SUPRANATIONAL REGULATION: THE EC

From the late 1980s onward, the EC4 developed a sectoral regulatoryframework for telecommunications. EC legislation outlawed monopolies,beginning with terminal equipment and advanced services in the late 1980sand early 1990s and then moving to core areas such as voice telephony andthe infrastructure; by 1998, EC law insisted that competition be allowedthroughout telecommunications (Natalicchi, 2001, pp. 38-85; Sandholtz,1998; Schneider, 2001a). EC directives also required regulators to be sepa-rate from suppliers, thus prohibiting the traditional combination of supplier,minister, and regulator. They laid down re-regulatory rules on matters such asinterconnection, universal service, licensing, and numbering.

The reasons for the expansion of EC regulation have aroused strongdebate. There has been disagreement as to whether the EC Commission, with

770 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

the support of the European Court of Justice, imposed regulation on reluctantmember states or whether in fact EC regulation was developed in partnershipbetween the commission and member states (cf. Sandholtz, 1998; Schmidt,1997; Thatcher, 2001). This debate is important in determining the extent towhich national governments as a group were coerced into regulatory reformor whether they collectively were able to control the EC. However, it is notaddressed here because it does not affect the status of EC regulation as aninternational factor, in the sense of being outside the control of individualgovernments. Moreover, the key purpose of this article is not to determinewho shapes internationalization but rather to see how internationalizationinfluences decision making over institutional reform within nations.

The EC provided a common legal framework that all member states had torespect, including directives that they had to transpose into national law. Tocomply with them, France, Germany, and Italy all passed major pieces of leg-islation, notably in 1996 and 1997.5 However, EC legislation did not coverprivatization, nor did it require the establishment of sectoral regulators thatwere independent from governments.6 Nevertheless, EC regulation did haveindirect effects on domestic decisions about these institutional featuresthrough its impacts on the strategies of PTO managements, governments, andnew actors in domestic arenas. Thus its influence went considerably furtherthan its legal requirements.

For PTO managements and governments, the EC liberalization of tele-communications markets across Europe undermined the traditional advan-tages of the public ownership of PTOs. It increased fears in France and Italythat unreformed PTOs would be disadvantaged facing powerful, expansion-ist competitors such as BT and AT&T in a liberalized European market andhence offered an important argument for altering the organizational status ofPTOs (Larcher, 1996; Locatelli, 1995). At the same time, as liberalizationadvanced, the EC Commission accepted cooperation among PTOs, approv-ing a series of joint ventures, cooperation agreements, and takeovers bynational champion PTOs such as France Télécom and Deutsche Telekom (cf.Blandin-Oberrnesser, 1996, pp. 142-147). Thus it increased the attractive-ness of privatization and international expansion for incumbent PTOs to off-set their loss of domestic monopolies. Moreover, the commission acteddirectly by developing networks with national actors and occasionally used

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 771

4. The 1997 General Agreement on Trade in Services on telecommunications added little tothe EC’s existing framework, hence it is not analyzed here; the term EC is used because legisla-tion was passed under the EC “pillar” of the EU.

5. In France, the 1996 law on liberalization and competition, 96-559; in Germany, the 1996Telekommunikationsgesetz (Postreform III); in Italy, Law 249 of July 31, 1997. Britain passedlittle legislation because it had already introduced most EC provisions.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

its legal powers over competition to aid change; for instance, in 1993 itapproved state aid to Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale on conditionthat Telecom Italia be privatized.

EC regulation also increased the advantages for governments of creatingsemi-independent regulators to whom difficult regulatory tasks could be del-egated. Governments faced conflicts between incumbent PTOs, new entrantsarmed with EC law, and pressure from the EC. Thus in Italy, governmentsfound themselves embroiled in lengthy conflicts between Telecom Italia, theItalian Anti-Trust Authority, the EU Commission’s powerful CompetitionDirectorate, and influential new entrants such as Olivetti and Fiat (Cassese,2001; Perez, 2002). Similar difficulties arose in interconnection, wherebyEC law increased complexity and threatened sharp clashes between incum-bents and new entrants (Autorité de régulation des télécommunications,1998, 1999; Prosperetti & Cimatoribus, 1998; Werle, 1999).

At the same time, the EC also offered a good mechanism for national pol-icy makers to shift blame and justify change. Governments and PTOs arguedthat the EC made liberalization inevitable (Chevallier, 1996, pp. 910-915;Dandelot, 1993, pp. 38-39; Direction générale des postes et télécommu-nications, 1994; Cavalli, 1995; Rendini, 1995; Brivio, 1996; Werle, 1999).Blame shifting extended to reforms that were not directly required by EC law.Thus in 1989 and 1990, EC requirements that regulation and supply be sepa-rated offered a convenient argument for governments in France and Germanyto justify transforming PTOs from civil service units into forms of public cor-poration (cf. Prévot, 1989, pp. 133-136; Schmidt, 1991). Later in the 1990s,EC liberalization was used to justify the creation of independent regulatoryagencies and privatization, especially in France (Chevallier, 1996, p. 916).

Within member states, EC regulation offered important instruments fornew actors to attack traditional norms and institutional structures. Entrantsuppliers applied EC law against “unfair competitive practices.” The clearestexamples came in Italy, where resistance to liberalization by the incumbentoperator Telecom Italia, together with political and bureaucratic inertia, pre-sented greater obstacles to reform than in other countries. Reformers, ledby the Italian Anti-Trust Authority turned to EC law to overcome oppositionto competition by Telecom Italia during the early and mid-1990s; exam-ples included mobile telephony, closed user networks, and laws on competi-tion and privatization in 1996 and 1997 (Cassese, 2001; Perez, 2002, chaps.2, 4, 5).

772 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

6. Under the Treaty of Rome, the EC may not alter ownership within member states (Article295, ex. 222); EC law insisted only that regulators be separated from market suppliers, not thatthey be independent of governments.

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Opponents of change were left badly disadvantaged by EC regulation.Reformers claimed that liberalization “imposed by Brussels” made overseasexpansion and privatization essential for the survival of incumbent PTOs.These arguments were attractive to the nationalistic Left and Right and henceweakened remaining coalitions that sought to preserve public ownership andmonopolies. A few trade unions, a proportion of employees, and isolatedparts of the extreme Left remained diehard opponents of reform. However,they faced a highly hostile terrain. They had no alternative to the EC’s regula-tory framework and could mount little opposition by the mid-1990s to legis-lation ending PTO monopolies. The key battle became the privatization ofPTOs. However, EC liberalization created a strong logic in favor of at leastpartial privatization, and opponents were left to defend a sectional interest(the position of PTO employees) rather than the previous institutional settle-ment of public ownership and monopoly. By the mid- to late 1990s, conflictscentered on how to “buy off” incumbent PTO employees in selling PTOsmore than the overall direction of institutional change. Even in France,the central battle concerned preserving the civil service status of FranceTélécom’s employees rather than liberalization, partial privatization, or theestablishment of a new semi-independent regulator (Thatcher, 1999, pp. 157-163).

CONCLUSION

Telecommunications in Western Europe offer a good case of how interna-tional factors can undermine institutional stability and cross-national differ-ences. Britain, France, Germany, and Italy represented examples of differentforms of capitalism. Long-established national institutions, supported bypowerful coalitions of interests within domestic arenas, existed in telecom-munications. Historical institutionalist models would predict that such insti-tutions would be difficult to alter and/or that reform would follow nationallyspecific paths. Thus nations would maintain different varieties of capitalism.

Until the mid-1980s, such predictions held true in telecommunications.Reform attempts were rare and were usually blocked. When changes wereintroduced, they varied across Britain, France, Germany, and Italy. More-over, they conformed to national patterns suggested by work on varieties ormodels of capitalism. However, from the late 1980s onward, rapid changeand convergence took place. By the late 1990s, all four countries had pri-vatized, liberalized, and delegated powers to new sectoral independent reg-ulatory authorities. Well-entrenched national institutions were reformed.

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 773

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Differences in domestic settings and past reform paths did not prevent insti-tutional convergence.

International pressures for change help explain the pattern of reform.Three international factors have been investigated in detail: transnationaltechnological and economic developments, overseas reforms, and EC regu-lation. They offer good examples of broader international forces of eco-nomic integration or globalization, cross-national policy transfer, and inter-national regulatory regimes. Direct links between these factors and thestrategies and coalitions of actors in the domestic politics of institutionalreform have been drawn. The international factors pressed actors in the samedirection, irrespective of diverse domestic settings. They contributed toreform and cross-national convergence, counteracting the effects of differentnational contexts.

Telecommunications in Europe is only one case, but it is interesting andimportant for claims of varieties of capitalism given its economic and histori-cal significance, deep institutional roots, high levels of internationalization,and patterns of institutional change. Nevertheless, although empirical con-clusions must be modest, four broader arguments can be put forward fordebate and testing.

First, despite powerful international pressures for change that operatedin the 1980s, initially, national institutional arrangements were resistant intelecommunications; insofar as reform occurred, it took nationally specificpaths. However, by the 1990s, transnational technological and economicdevelopments combined with overseas reforms and EC regulation to offer apowerful cocktail for rapid institutional reform and convergence. Twononrival hypotheses can be put forward for testing in other domains. One isthat varieties of capitalism hold for only limited periods of time but cannotwithstand international pressures over the medium term (from the case study,perhaps 10 to 15 years). Domestic settings may delay reform and conver-gence, but only for relatively limited periods. The other hypothesis is thatvarieties of capitalism cannot be maintained in domains characterized bypowerful combined international forces such as those seen in European tele-communications in the 1990s.

A second argument is that the analysis of internationalization shouldinclude not only economic globalization but also overseas reforms andsupranational regulation. Not only can these different forms of international-ization influence domestic politics, but they may combine to produce power-ful pressures for institutional reform. In the case of telecommunications,although countries were able to resist economic globalization, when otherinternational factors also operated, rapid, convergent institutional changetook place. Overseas examples and EC regulation reinforced the effects of

774 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

technological and economic pressures, altering the incentives of actors forreform, as well as providing rationales and examples for change.

A third issue is whether telecommunications is an exceptional case forvarieties of capitalism. On one hand, internationalization has gone furtherand faster than in many other sectors. Moreover, it is an economically strate-gic industry (i.e., one affecting other domains). Hence all countries may beobliged to adopt similar reforms to preserve competitive advantages in otherareas of economic life. On the other hand, international factors in telecom-munications, such as rapid technological and economic developments thatreduce the advantages of public ownership or monopoly and EC regulation,are also at work in other industries, such as energy and financial services.Moreover, telecommunications has offered examples for reforms in otherindustries, especially utilities, and hence its changes may cascade into otherfields. It would be valuable to compare the results found with other sectorswith similar institutional characteristics and levels of internationalization tosee if the results are replicated.

Finally, work on varieties of capitalism should examine explicitly howinternational factors operate within domestic decision making (i.e., it mustincorporate the second image reversed in explanations of patterns of nationalinstitutional reform). International factors can counterbalance or even over-come the effects of domestic settings in blocking change or orienting it innationally specific directions. Several mechanisms for their operation havebeen shown: They can alter the strategies of existing actors toward institu-tional reform; they can contribute to new actors entering institutional debatesto press for new arrangements; and they can weaken opponents of reform,both by diminishing their coalitions and by undermining their rationales forexisting arrangements. Analysis of how international factors affect domesticdecision making over institutional change does not undermine historicalinstitutionalist methods nor the value of studying varieties of capitalism. Onthe contrary, it allows the better specification of the conditions under whichdiverse domestic settings result in enduring varieties of capitalism and thoseunder which international factors can lead to institutional reform and/orcross-national convergence.

REFERENCES

Albert, M. (1993). Capitalism against capitalism. London: Whurr.Autorité de régulation des télécommunications. (1998). Rapport public d’activité. Paris: Author.Autorité de régulation des télécommunications. (1999). Rapport public d’activité. Paris: Author.

Thatcher / CHANGE IN EUROPEAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS 775

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Barroux, D. (1995, December 4). Fillon plaide pour l’alliance Phoenix à Washington. La Tri-bune desfossés, Retrieved from Dossiers de Presse, Bibliothèque de Sciences Po Paris.

Bennett, C. J. (1991). How states utilize foreign evidence. Journal of Public Policy, 11(1), 31-54.Berger, S., & Dore, R. (Eds.). (1996). National diversity and global capitalism. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.Blandin-Oberrnesser, A. (1996). Le régime juridique communautaire des services des télécom-

munications. Paris: Masson/Armand Collin/CNET-ENST.Boltho, A. (1997). Has France converged on Germany? Policies and institutions since 1958. In S.

Berger & R. Dore (Eds.), National diversity and global capitalism. (pp. 89-104). Ithaca, NY:Cornell University Press.

Boyer, R. (1996). The convergence hypothesis revisited: Globalization but still the century ofnations? In S. Berger & R. Dore (Eds.), National diversity and global capitalism. (pp. 29-59).Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

British Telecom. (1991). Serving telecommunications customers. London: Author.Brivio, E. (1996, June 7). Bruxelles mette in riga l’Italia. Il Sole 24 Ore. Retrieved from http://

www.ilsole24ore.com/.Cassese, S. (2000). La nuova costituzione economica. Rome: Laterza.Cassese, S. (2001). L’arena pubblica: Nuovi paradigmi per lo stato. Rivista Trimestrale di Diritto

Pubblico, 3, 601-650.Cavalli, M. (1995, February 6). L’Antitrust lascia I telefoni aziendali senza regolamenti. Il Sole

24 Ore. Retrieved from http://www.ilsole24ore.com/.Cawson, A., Morgan, K., Webber, D., Holmes, P., & Stevens, A. (1990). Hostile brothers: Com-

petition and closure in the European electronics industry. Oxford, UK: Clarendon.Chevallier, J. (1996). La nouvelle réforme des télécommunications: Ruptures et continuités.

Revue Française de Droit Administratif, 12(5), 909-951.Coen, D., Héritier, A., & Böllhoff, D. (2002). Regulating the utilities: Business and regulator

perspectives in the UK and Germany. Berlin, Germany: Anglo-German Foundation.Cohen, E. (1992). Le colbertisme “high tech.” Paris: Hachette.Cowhey P. F., & Aronson, J. (1993). Managing the world economy: The consequences of corpo-

rate alliances. New York: Council of Foreign Relations.Crandall, R. W. (1991). After the breakup: U.S. telecommunications in a more competitive era.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.Crouch, C., & Streeck, W. (Eds.). (1997). Political economy of modern capitalism: Mapping con-

vergence and diversity. London: Sage.Dandelot, M. (1993). Le secteur des télécommunications en France: Rapport au Ministre de

l’industrie, des postes et télécommunications et du commerce extérieur. Paris: PTT Ministry.Deeg, R., & Lütz, S. (2000). Internationalization and financial federalism. Comparative Political

Studies, 33(3), 374-405.Delebarre, M. (1997). Les enjeux d’avenir pour France Télécom. Paris: Ministre de l’Economie,

des Finances et de l’Industrie.Der Postminister findet für seine radikalen Liberalisierungspläne zunehmend Verbündete.

(1995, May 4). Wirtschaftswoche. Retrieved from Bundestag Pressedokumentation.Direction générale des postes et télécommunications. (1994). Quelle réglementation pour les

télécommunications françaises? Paris: Author.Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contem-

porary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5-24.Escande, P., & Marti, R. (1997). France Télécom en Bourse dès octobre. Les Echos, 9, 12.

776 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / September 2004

at University of Birmingham on November 10, 2013cps.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Evangelista, M. (1997). Domestic structures and international change. In Michael Doyle & JohnIkenberry (Eds.), New thinking in international relations theory (pp. 202-228). Boulder, CO:Westview.

Foreman-Peck, J., & Müller, J. (Eds.). (1988). European telecommunication organisation.Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos.

France Telecom. (1995). Télé-communiquer demain: Quelles règles du jeu? Paris: Ministère déléguéà la poste, aux télécommunications et à l’espace.