Comparative Organography in Early Modern Empires

Transcript of Comparative Organography in Early Modern Empires

Music & Letters,Vol. 90 No. 3, � The Author (2009). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.doi:10.1093/ml/gcp010, available online at www.ml.oxfordjournals.org

COMPARATIVE ORGANOGRAPHY IN EARLYMODERN EMPIRES

BY DAVID R. M. IRVING*

For all types of instruments that are used in diverse parts of the world,the reader is referred to the historiography of the Indies, in whichthese subjects are treated, leaving nothing more to be desired.

unidentified Jesuit in Manila, Observationes diversarum artium,late seventeenth century

TRAVELLERS, TRADERS, AND MISSIONARIES within the global networks of European imper-ial powers in the early modern period made significant contributions to the compara-tive study of the world’s musics.1 In their writings, they sought not only to compareand contrast many non-European practices with those of classical antiquity, but alsoto equate them with contemporaneous practices in Europe. Song, dance, and instru-mental traditions of non-Europeans were observed and described in relation to theirritual and symbolic significance, while published accounts allowed readers in Europeto familiarize themselves with the ‘exotic’ through text, image, and music notation.Much has been written about early modern intercultural encounters that occurred

through the performative exchanges of song, dance, and instrumental music. But therehas been relatively little attention devoted to the processes by which Europeans col-lected, transmitted, studied, and classified non-European musical artefactsçespeciallyinstrumentsçin the early modern period. Unlike real, live non-European musicians,musical instruments could be boxed up and shipped back to Europe for minute exam-ination, after having been presented as gifts, bought, traded, or stolen.2 Failing acquisi-tion of any physical specimens, it was still possible for detailed plans, diagrams, anddescriptions to be produced for transmission and publication. Similarities and differ-ences between European and non-European instruments could be noted, and theoriesformulated to explain the reasons for divergence or convergence in instrumental con-struction and practice. This type of scholarship in the early modern periodçlet uscall it comparative organographyçwas corollary to the development of ethnology, or

*Christ’s College, Cambridge. Email: [email protected] By ‘networks’ I imply global connections that were devised for trade, conquest, colonization, diplomacy, and

communication. Individual travellers, traders, and missionaries venturing beyond the geographical reach of Euro-pean colonial empires still remained part of these networks for as long as they maintained contact with any otheragent of European expansion.

2 The transportation of non-European performers to Europe in the early modern period was a relatively uncom-mon occurrence, but not unknown; see, for example, Roger Savage, ‘Rameau’s American Dancers’, Early Music, 11(1983), 441^52.

372

the study of peoples. It was made possible by the early modern frameworks of empireand trade routes. And it had far-reaching consequences, since European nations with-out overseas empires were able to draw from intra-European dissemination of know-ledge about the wider world as a result of the concurrent development of print cultureand the circulation of published literature.Descriptions of non-European music and musical instruments were most often em-

bedded in Europeans’ narratives of heroic voyages, geographical surveys, or hagio-graphic discourses on religious missions. By the end of the eighteenth century, pertinentdata had been woven into large compendia of music history and theory, and a smallhandful of works devoted purely to the discussion of a specific non-European musicalsystem had been published. As illustrated in this article’s epigraph, the historiographyof extra-European exploration provided the source texts to which those interested innon-European musical instruments most commonly referred in the early modernperiod.3

In the light of more detailed and systematic research in our own times, what Euro-peans thought of music and musical instruments found throughout the wider worldduring the early modern period may seem irrelevant. But early modern comparativeorganography remained the initial, necessary groundwork. In fact, no other group ofpeople (loosely bonded through social, political, and religious systems) compiled so di-verse a range of observations on musics from around the worldçnor reproducedthem so methodicallyças early modern European imperialists, missionaries, and itin-erant travellers.4 The enormous proliferation in Europe of descriptive texts on the onehand, and physical specimens on the other, attests to the curiosity and interest in non-European instruments displayed by early modern Europeans. However misleading orsimply inaccurate their writings may have been, they are invaluable from philologicaland historical viewpoints as evidence of scholarly development in music criticism.Moreover, they provided crucial building blocks for the development of comparativemusicology, which would in time reform itself as ethnomusicology.Treatises by Praetorius, Mersenne, Kircher, Bonanni, and La Borde all mention non-

European instruments to a lesser or greater extent.5 The information contained in theseworks provided the building blocks for organologists, including Guillaume Andre¤ Villo-teau and Victor-Charles Mahillon in the nineteenth centuryçnot to mention FrancisWilliam Galpin and Curt Sachs in the twentiethçwhose empirical studies led ultimatelyto the system of organological classification devised by Erich M. von Hornbostel

3 The original text of the epigraph reads: ‘Pro instrumentis omnis generis usitatis in diversis mundi partibus remit-tit se ad historiographos indiarum, qui fuse ea tractant, nec quicquam aliud desiderari poterit.’ ‘Musicalia specula-tiva’, in Observationes diversarum artium, Manila, late 17th c., Biblioteca Nacional de Espan‹ a, MS 7111, p. 591. This (asyet unidentified) Jesuit writer is paraphrasing a passage from Athanasius Kircher, SJ, Musurgia universalis, sive, Arsmagna consoni et dissoni: in X. libros digesta, 2 vols. (Rome,1650), i. 530.

4 Medieval travellers from European and non-European backgrounds alike had of course described instrumentsfrom cultures other than their own, but early modern European organography is the first large body of evidence tohave a truly global range of reference.

5 Michael Praetorius, Syntagma musicum, 3 vols. (Wittenberg; Wolfenbu« ttel, 1615^1620); Marin Mersenne,Harmonie universelle: Contenant la the¤ orie et la pratique de la musique ou' il est traite¤ des consonances, des dissonances, des genres, desmodes, de la composition, de la voix, des chants, & toutes sortes d’instrumens harmoniques, 2 vols. (Paris, 1636); Kircher, Musurgiauniversalis; Filippo Bonanni, Gabinetto armonico pieno d’istromenti sonori indicati, e spiegati (Rome, 1722); Jean Benjamin deLa Borde, Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne, 4 vols. (Paris, 1780).

373

and Sachs in 1914.6 Seminal work has been carried out in our own times by Jeremy Mon-tagu, John Burton, and Margaret J. Kartomi.7 I use the term‘organography’ here to dis-tinguish early modern writings on instruments from the complex discipline of organo-logy that began to evolve in the nineteenth century towards its fully-fledged form today.8

Organological literature is vast, butçtogether with writings by historical musicologistsand ethnomusicologistsçit has often overlooked the early modern writings on globalinstruments (comparative organography) that contributed to organology’s development.In this article, I seek to show how non-European musical instruments and their

descriptions acted as transportable, material evidence of ‘exotic’ musics for earlymodern European scholars, and as visual representations of musical and cultural differ-ences for eyewitnesses and European readers alike. As such, these objects were literallyinstrumental in developing paradigms for the study of non-European musics; theyalso acted as a means of assessing common humanity through the taxonomic trendsand comparative ethnological thinking of the early modern period. As we shall see,observations made about non-European musical instruments demonstrate Europeans’curiosity about the musical practices of others (and vice versa), their desire to empa-thize with other cultures through musical exchange, or their refusal to acknowledge orappreciate foreign musical aesthetics.

I. DIFFUSION, TRANSMISSION, AND REPRESENTATION

The early modern periodçthe age of European exploration and expansionçmustbe viewed as a critical stage in the worldwide process of intercultural contact: itrepresented a time when societies were no longer isolated, when taxonomies and epis-temologies had to be revised, when intercultural exchanges were made, and whenlong-distance relationships were intensified. In essence, it encapsulated a type ofconciliation between widely dispersed peoples who were unaware of each other’sexistenceçan encounter that had tragic consequences for many societies. As Euro-peans and non-Europeans came into contact with each other, they had to test and re-assess their own understanding of what it meant to be human, and to determine whatcultural trappings were associated with human identity.However much we may lament the violence of intercultural collisions, it remains an

inescapable truth that many of the world’s peoples came to know and engage with

6 See, for example, writings on instruments by Guillaume Andre¤ Villoteau in Description de l’E¤ gypte, ed. E. F. Jomard(Paris,1809^22);Victor-Charles Mahillon, Catalogue descriptif et analytique du Muse¤ e instrumental du Conservatoire royal de Musi-que de Bruxelles (Ghent and Brussels, 1880^1922); and FrancisWilliam Galpin’s ATextbook of European Musical Instruments:Their Origin, History and Character (London, 1937); and Curt Sachs’s The History of Musical Instruments (New York, 1940).See also Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs, ‘Systematik der Musikinstrumente: Ein Versuch’, Zeitschrift fu« r Ethno-logie, 46 (1914), 553^90. It is important to note that the four-class system of instrumental classification devised by Mahillonin 1880 and subsequently adapted by Hornbostel and Sachs was modelled on the Indian scholar Rajah Sir SourindroMohun Tagore’sYantra Kosha: or, ATreasury of the Musical Instruments of Ancient and Modern India, and of various other countries(Calcutta, 1875). See Joep Bor, ‘The Rise of Ethnomusicology: Sources on Indian Music c.1780 ^ c.1890’, InternationalFolk Music CouncilYearbook, 20 (1988), 51^73 at 64.

7 Jeremy Montagu and John Burton, ‘A Proposed New Classification System for Musical Instruments’, Ethnomusic-ology, 15 (1971), 49^70; Margaret J. Kartomi, On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments (Chicago andLondon, 1990). One of the most recent seminal texts for modern organology, representing the synthesis of a lifetime’swork, is Jeremy Montagu’s Origins and Development of Musical Instruments (Lanham, Md., 2007).

8 Current organology is defined as ‘the study of musical instruments in terms of their history and social function,design, construction and relation to performance’; Laurence Libin, ‘Organology’, New Grove II, xviii. 657. In this art-icle, I use the adjective ‘organological’ when and as it pertains to instruments.

374

each other during the early modern period through networks that emerged as a resultof European imperialism. Of course, European contact with parts of Asia and NorthAfrica had been established since antiquity, and extended by Marco Polo in the thir-teenth century; Eurasian trade along the Silk Road had also engendered many typesof cultural exchanges. But the initation of seaborne colonial and commercial enterprisesby Portugal, Spain, France, England, and the Low Countries from the last decade ofthe fifteenth century onwards marked the beginning of sustained and regular inter-course on a global scale with the Americas, India, East and South-east Asia, the Pacificregion, and Africa. Multidirectional intercultural contact forged a new awareness ofthe world that resulted in constantly accelerating global circulation of commodities,knowledge, technology, and people.9 This was early modern globalization.The first major phase in the development of comparative organography can be

traced alongside the patterns of discoveries made by navigators and explorers fromthe first trans-Atlantic voyage of Columbus in 1492 to the British and French voyagesin the Pacific during the final third of the eighteenth century. Literary sources datingfrom this period contain invaluable records of first encounters between mutually aliencultures, although they must be read with caution, and interpreted in the light of thecontext in which they were produced. Early modern observations about unknownenvironments and peoples were often composed in a manner that conformed to thehopes and expectations of the patrons who funded exploratory expeditions. As such,they often perpetuated the biased views of conquerors from Christian nations, orsought to synthesize non-Christian cultures as one conglomerate whole, placing themin opposition to Christian Europe in a type of comparative ethnology.10 But whileevents and peoples in distant lands could only be recorded and communicated toEurope through the interpretative filter of the author, artefacts that were carriedhome in triumph could provide indisputable proof of other, ‘exotic’ cultures.The material artefact of the instrument acted as a physical embodiment of the differ-

ences or similarities between European and non-European musics. Early modern organ-ographers could discuss a diverse range of characteristics of musical instruments, suchas their production and sound, their use and context, their value and socialstatus, and their symbolism. Like so many trophies, musical instruments or their depic-tions symbolized the distance travelled by the collector, while testifying to an appre-ciable level of active engagement with non-European cultures. Their curiosity valueearned them pride of place in early modern European collections and evenvisual assessment alone could evoke a wholly alien aesthetic sphere. Yet the irony ofEuropean observations of non-European instruments during the early modernperiod is that every single European instrument known at the time had originated

9 It also brought about new ways of narrating national identities and consolidating mythologies in support of colo-nialist enterprises, as EdwardW. Said points out in Culture and Imperialism (London, 1993).

10 Katherine Brown has pointed out the need to ‘challenge our present-day understanding of historical reliability byreading these texts in the light of the contemporary culture and circumstances that produced them’. Other dichoto-mies were also apparent in these writings; Brown notes that ‘the most important of these was that of the medievalworldview of traditional Christianity versus the embryonic worldview of scientific rationalism. Other importantoppositions included Protestantism versus Catholicism, Anglicanism versus Puritanism, Royalists versus Cromwell,the Portuguese versus the other European traders, superstition versus rationalism, absolute monarchy versus embry-onic democracy, woman as Madonna or whore, and Europe versus the Mughal Empire’. Katherine Brown, ‘ReadingIndian Music: The Interpretation of Seventeenth-Century European Travel-Writing in the (Re)construction ofIndian Music History’, British Journal of Ethnomusicology, 9 (2000), 1^34 at 3.

375

elsewhereçmainly the East.11 These had been so thoroughly adopted into Europeanpractice, and incorporated within European aesthetic ideals, that they had becomeindigenized and their differences forgotten. Thus the encounter with non-Europeaninstruments in the early modern period refigured a dichotomy of Europe vs. Otherness.For Europeans who never left their continent, imported musical instruments could

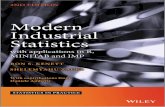

evoke the type of sound-world existing in distant lands. Even though only a relativelysmall clique (of scholars, the nobility, and patrons) was able to see and hear them atfirst hand, the general reader could learn something of particular specimens throughthe silent medium of published descriptions and illustrations. Images of these instru-ments were a means of evoking the sounds of musics that defied notation by Euro-peans, thus conveying their resonance even to readers non-literate in musical notation.As early as 1618, Michael Praetorius included in his Syntagma musicum three plates (oneis reproduced in Pl. 1) of ‘drawings of foreign, rustic and primitive instruments, someused in Muscovy, Turkey and Arabia, others in India and America, in order that weGermans might have some information about them, even though no knowledge ofhow they are played’.12 Visual comparison allowed Europeans to see types of ‘exotic’instruments, to estimate their sizes (the engraver went so far as to provide a scale-bar), and to imagine the sounds that might be produced.It seems, however, that the presence of ‘exotic’ instruments in Europe often served an

ornamental function. Only a few European musicians attempted to play non-Europeaninstruments in Europe (although many percussion instruments were eventuallyadopted and adapted into European practice13); in any case, these sorts of perfor-mances were, as we shall see, rare and incongruous affairs that allowed for nothingmore than superficial comparisons to be made with the standard European instrumen-tarium. Since the agents of collection and transmission generally had little knowledgeof the playing technique of non-European instruments or their cultural significance,instruments themselves were useless in the hands of practitioners or theorists withoutdetailed accounts of the complex cultural practices in which they were embedded. In1777, Charles Burney wrote to his correspondent Matthew Raper in China beggingfor more information about the Chinese sheng (mouth-organ), adding that ‘ourQueen [Charlotte] has one, but no one here can judge of its Effects for want of skill

11 Physical similarities noted between instruments of the Near East and Europe were undoubtedly due to the factthat these instruments had derived from common ancestors less than a millennium previously. According to TimothyMcGee, ‘the Crusades were for Europe a source of very practical knowledge about the culture of the eastern Medi-terranean. . . . Such musical instruments as the rebec, lute, and shawm, originally from the Islamic world, were intro-duced into Europe by the returning Crusaders’. Timothy J. McGee, ‘Eastern Influences in Medieval EuropeanDances’, in Robert Falck and Timothy Rice (eds.), Cross-cultural Perspectives on Music (Toronto, Buffalo, and London,1982), 79^100 at 97. Performance techniques varied enormously, however, and in spite of the visual resemblances ofinstruments, many sounds were described disparagingly by Europeans. See Ian Woodfield, English Musicians in theAge of Exploration (Sociology of Music, 8; Stuyvesant, NY, 1995), 270. For a general historical survey of Europe’s cul-tural and economic dependence on Asia, see John M. Hobson,The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization (Cambridge,2004; 2nd rev. edn., 2006).

12 Michael Praetorius,The Syntagma musicum of Michael Praetorius.Vol. 2, De organographia, First and Second Parts, trans.Harold Blumenfeld, 2nd edn. (NewYork,1980), g. ‘So hab ich auch derAu�la« ndischen / Barbarischen und BemrischenInstrumenten / so zum theil in der Mu�cam / Tu« rcten und Arabien / zum theil in India und America gebrauchtwerden / Abconterfenung mit hinzu seken wollen / damit sie uns Teutschen / zwar nicht zum gebrauch / besondernzur wissenschafft auch befantsein mu« chten.’ Praetorius, Syntagma musicum, ii (Tomus Secundus De Organographia, 1619),introduction.

13 See James Blades and Jeremy Montagu, Early Percussion Instruments from the Middle Ages to the Baroque (Early MusicSeries, 2; London, 1976).

376

PL. 1. ‘Exotic’ instruments: ‘1./2. Satyr pipes. 3. American horn or trumpet. 4. A ring whichthe Americans strike much like a triangle. 5. American shawm. 6. Cymbals which the Ameri-cans play upon like our bells. 7. A tambourine which they throw into the air and then catch.8./9. American drums.’ Michael Praetorius, Syntagma musicum, ii: De Organographia (1619),pl. XXIX. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library

377

in playing upon it’.14 On the other hand, Jean-Philippe Rameau possessed an ‘orgue debarbarie’on which he played Chinese melodies transcribed by the Jesuit Jean Baptistedu Haldeçeven though the instrument seems to have come from or via the Cape ofGood Hope.15 Rameau may have considered that a ‘barbarian’ instrument fromAfrica was compatible with Chinese musical style,16 but he was exceptional for actuallyplaying the instrument at all. Europeans interested in non-European music or perform-ance practices generally had to resort to descriptions of ceremonies written by eyewit-nesses. As many of the earliest sources documenting non-European instruments relatedirectly or indirectly to voyages, it is sailors, merchants, and missionaries who aremainly responsible for most of the literature about maritime and land-based explor-ation. The copious numbers of published traveloguesçincluding anthologies such asPurchas his pilgrimes, The¤ venot’s Relations de divers voyages curieux, or the Churchill broth-ers’A Collection of Voyages and Travelsçwere recognized by scholars and general readersalike as ideal and unique sources for data concerning ‘exotic’ musical practices.17

Among the most highly educated early modern European travellers were missionariesçparticularly Jesuits, whose expertise in disciplines such as mathematics, astronomy,acoustics, and physics earned them positions of favour in several Asian high courts.Jesuits’ reports and letters, which were often published and circulated widely, were con-sidered at the time to provide some of the most reliable observations of distant places.Like other religious organizations and groups of colonists, the Society of Jesus relied

on global routes of trade and communication for its worldwide mission in the earlymodern period, and made full use of these systems for the transportation of its equip-ment. European instruments were therefore disseminated throughout the rest of theworld as the belongings of travellers, commodities to be sold or distributed in colonies,equipment for Christian missions and churches, or gifts to non-European rulers.18 Bycontrast, the contexts in which non-European instruments were transported back toEurope ranged from the presentation of curious artefacts (as trophies or ornaments)to the provision of ethnographic data for scholars, to the bestowal of gifts (often fromone monarch to another). For example, Captain James Cook transported a comprehen-

14 Charles Burney,The Letters of Dr Charles Burney, i: 1751^1784, ed. Alvaro Ribeiro, SJ (Oxford, 1991), 234.15 In writing about Chinese music theory, Rameau comments: ‘cela se trouve dans une Orgue de Barbarie, appor-

te¤ e du Cap de Bonne-espe¤ rance par M. Dupleix, dont il a eu la bonte¤ de me faire pre¤ sent, & sur laquelle peuvent s’exe¤ -cuter tous les airs chinois copie¤ s en Musique dans le III.e Tome du R. P. du Halde, & dans la page 380 du XXII.e

tome in-12 de l’Histoire des voyages, par M. l’Abbe¤ Prevo“ t’. Jean-Philippe Rameau, ‘Nouvelles re¤ flexions sur le principesonore’, Code de musique pratique (Paris, 1760), 192; facsimile in Jean-Philippe Rameau,The Complete Theoretical Writingsof Jean-Philippe Rameau, ed. Erwin R. Jacobi (Miscellanea, 3; [Rome], 1967^72), iv. 216. A few decades later, LaBorde contended that this instrument had been improperly described by Rameau. He gave an illustration of the in-strument in question (a type of xylophone), with the following caption: ‘Instrument Chinois. Que Rameau appelleimproprement Orgue de Barbarie dans son Code de Musique. Cet Instrument a e¤ te¤ aporte¤ des Indes par M. le M.is

Dupleix et apartient maintenant a' M. l’abbe¤ Arnaud.’ La Borde’s description of the instrument’s provenance (‘lesIndes’) is unilluminating. In the context of Chinese music, La Borde may have objected to Rameau’s use of the word‘orgue’ for a percussive instrument, since ‘orgue’ was more properly applied by early modern Europeans to the shengand related instruments. La Borde, Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne, i, 2nd plate after p. 142.

16 As Anthony Pagden has noted, ‘in European eyes most non-Europeans, and nearly all non-Christians, includingsuch ‘‘advanced’’ peoples as the Turks, were classified as ‘‘barbarians’’’. Anthony Pagden,The Fall of Natural Man:TheAmerican Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology, new edn. (Cambridge, 1986), 13^14.

17 Samuel Purchas, Purchas his Pilgrimes, in fiue bookes: the first, contayning the voyages and peregrinations made by ancientkings (London, 1625); Melchisedec The¤ venot, Relations de diuers voyages curieux qui n’ont point este¤ publie¤ es, new edn.(Paris, 1696); A Collection of voyages and travels: some now first printed from original manuscripts. Others translated out of for-eign languages, and now first publish’d in English, ed. Awnsham and John Churchill (London, 1704).

18 On the role of keyboard instruments as diplomatic gifts, see IanWoodfield, ‘The Keyboard Recital in OrientalDiplomacy, 1520^1620’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 115 (1990), 33^62.

378

sive collection of artefacts from Oceania (including many musical instruments) to Brit-ain in 1771,19 and, as we have seen, Queen Charlotte of Britain (wife of George III) pos-sessed a Chinese sheng. In some cases, instruments from abroad were imported toEurope for sale; there was, for instance, a thriving trade in ivory horns (oliphants)from north Africa, which were producedçand often adorned with intricate carvingsçfor the European market.20

Ivory was instantly recognizable to Europeans as a rare and valuable commodityfrom exotic climes. Once disembedded from its point of origin and transported toEurope, it both represented and evoked faraway localities, bringing them within therealms of immediate experience. We see that in many cases the physical make-up ofinstruments often reflected the different environments in which the world’s peopleslived.21 Local natural resources available to particular societies not only dictated thetypes of instruments that were built in those areas, but also ensured that some instru-ments were more highly prized than others since the materials used varied in value.The components of certain instruments could also demonstrate different levels oftechnological proficiency: for instance, the use of metal strings implied the knowledgeof extrusion techniques, while the methods of wood-carving used could indicate the in-genuity of craftmanship and familiarity with fundamental principles of acoustics. Ofcourse, some societies chose not to make use of particular resources or technologies,for their own cultural reasons. Just as the wheel and axle in the pre-Columbian Amer-icas were used only for children’s toys, Amerindian cultures appear to have made useof the bow and arrow for hunting and warfare without ever choosing to adapt thebow-string for any musical purpose.22 But global networks of trade and communicationdiffused raw materials and construction techniques throughout the world in the earlymodern period, just as they do today. For example, extra-European environmentswere the source of many raw materialsçconsidered luxury items in Europeçthatwere gradually introduced into the manufacture of European instruments, such asebony, ivory, pernambuco wood, silk, and tortoiseshell. While silk is the only one ofthese materials that could have any immediately recognizable difference in sound pro-duction, others contributed to the aesthetic function of the instrument, which was espe-cially significant within domestic settings and the culture of amateur musicians. Yetearly modern European bow-makers, having experimented with many different typesof hardwoods from around the world, appear to have made the deliberate choice ofusing snakewood, then pernambuco, as their favoured materials for bow sticks, asthese woods were strong and dense, but light.23 We can only speculate as to how differ-ently the design of the European bowçand, in consequence, the music it producedçmay have developed had these makers not had access to these particular woods from

19 Wilfred Shawcross, ‘The Cambridge University Collection of Maori Artefacts, Made on Captain Cook’s First Voyage’,Journal of the Polynesian Society, 79 (1970), 305^48 at 305.

20 Many oliphants were produced in parts of Africa where the Portuguese had set up regular trade; they were oftenornamented with carved scenes of African or European life. Those that are end-blown, rather than side-blown (as istypical in Africa), are thought to have been produced in Africa for the European market.

21 For a thorough treatment of the effect of different environments on the course of history for different peoples, seeJared M. Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel:The Fates of Human Societies, 2nd edn. (NewYork, 1999).

22 No string instruments existed in the Americas before the advent of sustained connections with Europe andAfrica from the turn of the sixteenth century. See Montagu, Origins and Development, 196; also Robert Murrell Steven-son, Music in Aztec and Inca Territory (Berkeley, 1968), 22^7.

23 See Robert E. Seletsky, ‘New Light on the Old Bowç1’, Early Music, 32 (2004), 286^96 at 288; id., ‘New Light onthe Old Bowç2’, ibid. 415^26 at 415.

379

the Americas. Like so many other aspects of early modern European culture, musicwas inextricably intertwined with the processes of incipient globalization.

II. IDENTIFICATION AND UNDERSTANDING

Identifying the cultural specificity of certain instruments is a crucial part of organ-ological observation. But at the point of initial contact between European and non-European cultures, early modern explorers were often unaware of non-Europeaninstruments’ deep cultural significance, even after they had recognized such objectsçand particularly in their first encounters with peoples who had no prior experience ofEuropeans. In the earliest record of contact between Europeans and the Ma~ori ofAotearoa/New Zealand, for example, Abel Janszoon Tasman described how Ma~orimen shouted at his ship and blew an instrument that sounded ‘like a Moorish trum-pet’.24 The response in kind, ordered by Tasman, was a series of trumpet blasts in alter-nation with those of the Ma~ori, and finally cannon fire. The next day, brutal conflictensued. Mervyn McLean observes that Tasman was ‘unaware that he had probablyreceived and accepted a challenge to fight’.25 Misunderstandings of this sort werecommon in early modern exploration, although the sounds of instruments with warlikeassociations in European cultures, such as drums, were sometimes heeded for theirmessage in the right contexts. Nevertheless, almost nothing could be taken for grantedin interpreting different peoples’ sonic signals and their cultural resonance. It wasonly through sustained intercultural engagement that opposing parties could come toany mutual tolerance of each other, but this engagement was rarely on equal terms.In the Americas, many indigenous cultures were systematically eradicated, although

chroniclers (indigenous and European alike) often left extensive ethnographic docu-mentation of what had gone before. The earliest Spanish descriptions of Aztec musicalinstruments identified some that were reserved for the most solemn rituals (and whichoften accompanied human sacrifice),26 but since many of these instruments, such as rat-tles and conch trumpets, were assimilated into musical practices for Christian worship,it can be assumed that their associations with heathen rituals were quickly overlookedby missionaries.They saw the instruments as aides for conversion, especially once num-bers of converts began to swell. Lists of equipment required for missions even beganto include tiny aerophones, or percussion instruments such as rattles and drums, sincethey were thought to please non-Europeans.27 Dictionaries of indigenous languagesproduced by missionaries in the early modern period often contain seminal organologi-cal data, describing not only construction techniques but also the natural resourcesused. Since many of their definitions document practices that disappeared when

24 Mervyn McLean, Maori Music (Auckland, 1996), 23.25 Ibid.26 See, for instance, the discussion of the a¤ yotl (tortoise shell drum), chicahuaztli (long rattle board), tecciztli

(conch trumpet) and chililitli (copper discs) in Robert Murrell Stevenson, ‘Aztec Organography’, Inter-AmericanMusic Review, 9/2 (1988), 1^20 at 4^5.

27 For example, the list of requirements for the Jesuit mission to the Mariana Islands, drawn up in Mexico in 1668,included the following musical instruments: whistles, little bells, rattles, a drum, recorders, gayta (implying a type ofbagpipe) ‘or any other instrument [that is] easy to play’, along with standard European instruments such as a horn,a trumpet or shawms, harp, guitar, and (spare) strings. See History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents, ed.Rodrigue Le¤ vesque, 20 vols. (Gatineau, Que¤ bec, 1992^2001), iv. 382^3.

380

European instruments were introduced and began to dominate,28 these are particularlyuseful documents: in the words of Robert Murrell Stevenson, ‘anyone who has madeuse of the dictionaries soon comes to know them as the organologist’s best friends’.29

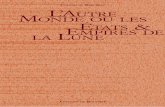

The syncretic nature of the local forms of Roman Catholicism that emerged in theSpanish empire was reflected in the pluralistic musical practices cultivated by the neo-phytes. Precolonial instruments sometimes appear to have complemented their newlyintroduced European counterparts. One eighteenth-century artist in Mexico demon-strated this juxtaposition clearly in his depiction of the traditional dance of the deposedAztec emperor Moctezuma, accompanied by an ensemble of indigenous instrumentson the left-hand side, and European instruments on the right.30 In areas where the mis-sion was on a less secure footing, however, missionaries often saw the use of traditionalpercussion instruments as a relapse to old ‘heathen’ ways. In the Congo, for example,the Capuchin Jerom Merolla da Sorrento noted in 1682 that when missionaries heardtheir neophytes revert to the use of drums at feasts and entertainments, they would ‘im-mediately run to the place in order to disturb the wicked Pastime’. He claimed thathis intended converts ‘not only make use of these Drums at Feasts, but likewise at theinfernal Sacrifices of Man’s Flesh to the Memory of their Relations and Ancestors, asalso at the time when they invoke the Devil for their Oracle’.31 The use of drums tocommunicate with the supernatural world was not confined to countries distant fromEurope. In northern Scandinavia, for example, the Laps were noted to play highlydecorated drums, or kannus (see Pl. 2), as the means of receiving messages from thegods. A change in the sound of the kannus, played while songs were sung, indicatedthat a sacrifice was pleasing to Thor. The sacrifice was never offered until sonicassent had been given.32

While gods could ‘speak’ through drums, some percussion instruments could becomeobjects of veneration themselves, as in Brazil, where the Tupinamba¤ made offeringsof food and drink to their maracas. These instruments, as Le¤ ry observed, were attribu-ted ‘some sanctity’; ‘they [the Tupinamba¤ ] say that oftentimes when they shake thema spirit speaks to them’.33 Similarly, the Aztecs believed that their instruments

28 The Jesuit Francisco Ignacio Alzina, for instance, observed that a dance called taruc in the Visayas (the centralthird of the Philippine Archipelago) was once accompanied by indigenous instruments such as bells and other smallpercussive devices, ‘but these were their ancient instruments and now they use guitars, harps and other musical instru-ments in our style’ (‘E¤ stos eran sus antiguos instruments y agora usan de guitarras y arpas y otros instrumentos mu¤ si-cos a nuestro modo’). Francisco Ignacio Alzina, SJ, Una etnograf|¤ a de los indios bisayas del siglo XVII, ed. Victoria Yepes(Coleccio¤ n Biblioteca de historia de Ame¤ rica, 15; Madrid, 1996), 213.

29 Robert Murrell Stevenson, Music in Aztec and Inca Territory (Berkeley, 1968), 260.30 Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (New Haven and London, 2004), 172.

Lam. 3, Pagina 118 in Joaqu|¤n Antonio de Basara¤ s y Garaygorta, ‘Origen, costumbres, y estado presente de mexicanosy philipinos’ (1763), Library of the Hispanic Society of America (NewYork), MS HC. 363^940,1^2. Basara¤ s’s descrip-tion of the instruments used can be found in Una visio¤ n del Me¤ xico del siglo de las luces: La codificacio¤ n de Joaqu|¤ n Antoniode Basara¤ s, ed. Ilona Katzew (Mexico, DF, 2006), 118^19.

31 Jerom Merolla da Sorrento, ‘A Voyage to Congo, and Several Other Countries, chiefly in Southern-Africk, byFather Jerom Merolla da Sorrento, a Capuchin and Apostolick Missioner, in theYear 1682’, in A Collection of Voyages andTravels, ed. Churchill, i. 695. The passage is also quoted in Frank Ll. Harrison,Time, Place and Music: An Anthology ofEthnomusicological Observation c. 1550 to c. 1800 (Amsterdam,1973), 96.

32 John Scheffer [ Johannes Schefferus],The History of Lapland, wherein are shewed the Original, Manners, Habits, Mar-riages, Conjurations, &c. of that People, trans. Acton Cremer (Oxford, 1674), 42; for the description of the drum, seep. 47; on the use of the instrument, see pp. 52^8 (also quoted in Harrison,Time, Place and Music, 74^83). Some Chris-tian elements had evidently begun to influence the designs made on the drum by this time, as can be seen in Pl. 2.

33 English translation (of edition published in Paris, 1585) in Harrison,Time, Place and Music, 23. Original text: ‘ilsdisent que souventesfois en les sonnans un esprit parle a' eux’. Jean de Le¤ ry, Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Bresil(original publication Geneva, 1580), facs. edn., ed. Jean-Claude Morisot (Geneva, 1975), 250.

381

PL. 2. Lappish drums (kannus or quobdas), in John Scheffer,The History of Lapland, 48 [erro-neously paginated as p. 50]. Reproduced by kind permission of the Scott Polar Research Insti-tute, University of Cambridge

382

teponaztli and hue¤ huetl were divine beings that had been expelled from heaven, as-suming ‘the form of musical instruments’on earth.34 For these societies, musical instru-ments constructed by humansçor, as in the case of seed-pod rattles, selected andadapted from natureçthus assumed a supernatural position by virtue of having beendevised by humankind, with guidance that was accorded to divine powers, thus becom-ing a ‘creation within Creation’. Some societies, of course, represented the other ex-treme in the association of religious belief with instruments. Certain early modernEuropean travellers to the Middle East were astonished to learn, for example, that theuse of instruments was officially prohibited in Islam (although this ruling was oftenflouted in practice).35 Comparative organography proved to early modern scholarsthat musical instruments served a diverse range of functions throughout the world,and that their use was often governed by religious tenets. The convergence of differentsocieties around the world as a result of sustained contact through trade, diplomacy,or colonialism in the early modern period meant that hierarchies of cultural and reli-gious symbolism had to be recast in the light of intercultural comparisons, but insome cases they were unceremoniously suppressed by a hegemonic imperial power.

III. ANTIQUITY

While for L. P. Hartley, ‘the past is a foreign country’, for early modern European tra-vellers, the opposite was true. At a time when Eurocentric writers considered theirown territory a hotbed of modernity, and all other places to ‘lag behind’ in technology,political systems, or social structures, some non-European peoples appeared to sharecommon cultural elements with the classical civilizations of Europe itself. Europeanswere familiar with the differences revealed to them by studying their own ancient cul-tures, and antiquity became a standard with which non-European cultures could becompared. In European eyes, certain non-European societies represented living exam-ples of antique civilizations.We have already seen how images of non-European instruments entered the imagin-

ation of European readers; we should also remind ourselves that illustrations of musicalinstruments from European antiquityçGreece and Romeçwere regularly publishedand republished in early modern European books.36 With these two types of imagespresented alongside each other, non-European instruments resembling those of classicalantiquity were considered to be signifiers of an emerging civilization. In early modernethnographic descriptions, comparisons between contemporary ‘pagan’ peoples andpre-Christian European antiquity were also a means of making non-European culturesand practices more palatable to European sensibilities. For missionaries, the messagewas clear: if pagan Europe had been converted to Christianity, what was to stop evan-gelical success in the rest of the world?European religious functionaries were quick to capitalize on the comparisons that

emerged between the societies of the Old and NewWorlds. The French Jesuit JosephFranc� ois Lafitau, for example, documented the customs of the indigenous population

34 Stevenson, Music in Aztec and Inca Territory, 111.35 See the comments by Jean Chardin in Harrison,Time, Place and Music, 128, 133. However, the role of music in

Islam throughout the history of religion has been reassessed by a number of writers in recent times. See e.g. AmnonShiloah, ‘Music and Religion in Islam’, Acta Musicologica, 69 (1997), 143^55.

36 See Naomi J. Barker, ‘Un-discarded Images: Illustrations of Antique Musical Instruments in 17th- and 18th-Century Books, their Sources and Transmission’, Early Music, 35 (2007), 191^211.

383

in North America in relation to those of European ‘primitive times’.37 His publicationincluded two detailed plates of ‘musical instruments of earliest antiquity’ças hadbeen proposed and illustrated by Kircher in his Musurgia universalisç‘placed in com-parison with those of the Americans’.38 Philip V. Bohlman notes that ‘Lafitau was a re-markable experimenter with musical ethnography . . .demonstrating that such instru-ments possessed no less rational functions than similar instruments of the Greeks’.39

Likewise, in the Spanish colony of the Philippines, another Jesuit named Pedro MurilloVelarde claimed that a local flute called the bangsi looked as if it came from an ancienttomb, and ‘accordingly [sounded] sad’; he also compared warlike dances of certain in-digenous communities to those of the ancient Greeks and Trojans.40 For early modernethnographers the rational nature of non-Europeans could be tested against the modelof classical antiquity, and instruments were highly visible and audible markers of a civi-lization’s condition.Nowhere was this comparative process more evident than in the islands of the Pacific

Ocean, where Europeans encountered societies that they considered to epitomize theiridealized visions of ancient Greek life and customs. The isolation of many Polynesianpeoples was broken in the second half of the eighteenth century, with British andFrench voyagers at the forefront of this endeavour.41 By this time, the philosophy ofthe Enlightenment prevailed, pervading the organization and operation of exploratoryvoyages, which carried scientists and artists instead of soldiers and missionaries.42 Ves-tiges of antiquity were apparent in Pacific Islander communities, and these werereflected in the voyagers’ descriptions and artistic representations of various islandsand their peoples, as well as the names given to them by Europeans. Not least, connec-tions with European classical antiquity were noted in their musics.43

In 1776, Charles Burney commented in his General History on the reports that cameback from the Pacific:

A syrinx, or fistula panis, made of reeds tied together, exactly resembling that of the ancients,has been lately found to be in common use in the island of NewAmsterdam [Tongatapu], inthe South Seas, as flutes and drums have been in Otaheite [Tahiti] and New Zealand; whichindisputably prove them to be instruments natural to every people emerging from barbarism.

37 Joseph-Franc� ois Lafitau, SJ,M�urs des sauvages ameriquains compare¤ es aux m�urs des premiers temps (Paris,1724).Trans-lated as Joseph Franc� ois Lafitau, SJ, Customs of the American Indians Compared with the Customs of Primitive Times, ed. andtrans. William N. Fenton and Elizabeth L. Moore, 2 vols. (Publications of the Champlain Society, 48^9; Toronto,1974^7).

38 Lafitau, Customs of the American Indians, pl. VIII and IX. See also Philip V. Bohlman, ‘Missionaries, MagicalMuses, and Magnificent Menageries: Image and Imagination in the Early History of Ethnomusicology’, World ofMusic, 30 (1988), 5^27.

39 Philip V. Bohlman, ‘Representation and Cultural Critique in the History of Ethnomusicology’, in Bruno Nettland Philip V. Bohlman (eds.), Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology(Chicago and London, 1991), 131^51 at 137.

40 ‘El Bangsi, a' modo de flauta, que parece sale de una sepultura, segun es triste . . .Los Visayas, Zambales, y Boho-lanos usan un Bayle muy guerrero, con lanzas, campilanes, y otras armas, como los Griegos, y Troyanos.’ Pedro Mu-rillo Velarde, Geographia historica, donde se describen los reynos, provincias, ciudades, fortalezas, mares, montes, ensenadas, cabos,rios, y puertos, con la mayor individualidad, y exactitud, etc., 10 vols. (Madrid,1752), viii. 38. For further discussion of the mu-sical dimension of early modern colonial ethnography in the Philippines, see D. R. M. Irving, Colonial Counterpoint:Music in Early Modern Manila (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

41 See David Irving, ‘The Pacific in the Minds and Music of Enlightenment Europe’, Eighteenth-Century Music,2 (2005), 205^29; Anthony Pagden, Peoples and Empires: Europeans and the Rest of the World, from Antiquity to the Present(London, 2002), 119^34.

42 See Pagden, Peoples and Empires, 132.43 On European reactions to the music of Pacific Islanders, see Vanessa Agnew, Enlightenment Orpheus:The Power of

Music in OtherWorlds (Oxford, 2008), 73^119.

384

They were first used by the Egyptians and Greeks, during the infancy of the musical artamong them; and they seem to have been invented and practised at all times by nationsremote from each other, and between whom it is hardly possible that there ever could havebeen the least intercourse or communication.44

Even in the final quarter of the eighteenth century, Burney already seems to be hintingat a theory of convergent evolution for musical instruments, arguing that flutes anddrums are part of a teleological ‘natural’ progression from a state of ‘barbarism’ to‘civilization’. He also identifies the fact that vast distances separating various humansocieties from others had acted as insurmountable barriers preventing communicationor intercourse (musical or otherwise) until the advent of global systems of transporta-tion in the early modern period. By this reasoning he proposes that all humans expressinnate musicality by means of instrument production as a result of convergent evolu-tion in isolationçnot diffusion from other cultures. But he does not go so far as to sug-gest that Pacific Islanders in continual isolation from Europe would have developedmusic that was ‘sophisticated’ in his eyes.While the Pacific Ocean and the NewWorld represented the most distant frontiers in

the early modern European consciousness, the Near East and India were regions thathad been known to Europeans for far longer, since they were relatively more accessiblefor travellers. Many Europeans were resident in the Near East for diplomatic purposes,and their sustained contact with Oriental cultures made them more qualified thanmost Europeans of the time to proffer descriptions of instruments or to pass judgementon them. The eighteenth-century French writer Charles Fonton, who had lived in Con-stantinople at a young age and had been thoroughly immersed in the Ottomans’ lan-guage, history, and culture, described a number of Ottoman instruments in his unpub-lished ‘Essai sur la musique orientale compare¤ e a' la musique europe¤ enne’ of 1751.45

In treating the tanbur, a plucked chordophone, he identified Plato as a common elementbetween European and Ottoman musics, but he disputed the extent of the Ottomanclaim for a direct musical lineage from the Greek philosopher.46 Evidently he wished topreserve ancient Greek heritage for Europe, in defiance of Ottoman hegemony over Hel-lenic regions.India, too, furnished many specimens of ‘ancient’ musical instruments in common

use during the early modern period that fascinated European scholars. Mersenne, forinstance, reproduced a diagram of a v|~nq a~ in his Harmonie universelle, but claimed errone-ously that part of it could double as a flute.47 The v|~nq a~ was sufficiently different in ap-pearance from so many other instrumentsçits two gourds made it stand outçthat itcaptured the eye of many Europeans. Many early modern observers described it aspleasing in sound, even if it struck them as looking ‘odd’.48 In the late eighteenth cen-tury, this instrument was the subject of another examination, described by Joep Bor

44 Charles Burney, AGeneral History of Music, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period.To which is prefixed, A Dissertationon the Music of the Ancients, 4 vols. (London, 1776^89), i. 267.

45 For a biographical summary of Fonton, see Amnon Shiloah, ‘An Eighteenth-Century Critic of Taste and GoodTaste’, in Stephen Blum, Philip V. Bohlman, and Daniel M. Neuman (eds.), Ethnomusicology and Modern Music History(Urbana and Chicago, 1991), 181^9 at 182^3.

46 Charles Fonton, ed. Eckhard Neubauer, ‘Essai sur la musique orientale compare¤ e a' la musique europe¤ enne[1751]’, Zeitschrift fu« r Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften, 2 (1985), 317^18. What Fonton probably failed torealize, however, is that Europe owed its knowledge of many ancient Greek philosophers to the Arab world’s preserva-tion of classical texts that had been forgotten in Europe for centuries.

47 Mersenne, Harmonie universelle, ii. 228. Also noted in Bor, ‘The Rise of Ethnomusicology’, 53.48 See Pietro della Valle’s description, quoted in Bor, ‘The Rise of Ethnomusicology’, 52.

385

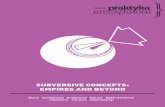

as ‘highly accurate’, which culminated in the Englishman Francis Fowke publishing hisobservations in the first volume of the journal Asiatick Researches (Calcutta, 1788).49

Fowke described how he had compared the tunings of a v|~nq a~ and a harpsichord inorder to establish the intervals of the frets.50 He also praised the ‘style, scale, and an-tiquity of this instrument’, and provided two engravings, one showing it being playedby the virtuoso Jeewun Shah, and another presenting a clear diagrammatic representa-tion of the instrument (Pl. 3).51 Fowke’s reference to the antiquity of the v|~nq a~ reflectsthe growing interest of Anglo-Indian colonial society in the histories of ancient cultureson the sub-continent. This area of inquiry was spearheaded by the seminal work ofthe Sanskrit scholar SirWilliam Jones (‘Orientalist Jones’, 1746^94), who founded theAsiatic Society of Bengal, and who was in fact responsible for the publication ofFowke’s letter. Jones rendered great homage to ancient Indian languages, especiallySanskrit (whose refinement made him prefer it over both Classical Greek and Latin),and his influence undoubtedly contributed to the rise of ‘Orientalism’ as a significantacademic pursuit in the following centuries. Yet at the same time he also played a piv-otal role in codifying and consolidating the Occident^Orient dichotomy from a philo-sophical, linguistic, and literary perspective, as EdwardW. Said has pointed out, thusfurthering colonialist objectives (whether unwittingly or not).52

PL. 3. Diagram of a v|~nq a~ in ‘An EXTRACT of a LETTER from Francis Fowke, Esq. to the Presi-dent’, plate between pp. 296 and 297. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cam-bridge University Library

49 Ibid. 55; Francis Fowke, ‘An EXTRACT of a LETTER from Francis Fowke, Esq. to the President’, Asiatick Researches:or,Transactions of the Society, Instituted in Bengal, for inquiring into the history and antiquities, the arts, sciences, and literature, ofAsia, 1 (Calcutta, 1788). This article is reprinted in Sourindro Mohun Tagore, Hindu Music from Various Authors, 3rdedn. (Chowkhamba Sanskrit Studies, 49; Varanasi, 1965), 191^7.

50 ‘You may absolutely depend upon the accuracy of all that I have said respecting the construction and scale ofthis instrument. It has all been done by measurement: and, with regard to the intervals, I would not depend uponmy ear, but had the Been [v|~nq a~ ] tuned to the harpsichord, and compared the instruments carefully, note by note,more than once.’ Fowke, ‘An EXTRACT of a LETTER’, 295. See also IanWoodfield, Music of the Raj: A Social and Eco-nomic History of Music in Late Eighteenth-Century Anglo-Indian Society (Oxford, 2000), 178^9.

51 Fowke, ‘An EXTRACT of a LETTER’, 299.52 See EdwardW. Said, Orientalism (London, 1978; new edn., London, 2003), 77^9.

386

Still, even when read in the light of this context, Fowke’s report is arguably the mostdetailed of any description of the v|~nq a~ made during the early modern period, and inmany ways it represents the beginnings of reliable organological studies made in situoutside Europe, as it combines observations of performance practice with meticulousphysical examination of construction and of sound production.53 It is also unusual forextolling the virtuosity of a named (and depicted) practitioner of the instrument, inmuch the same way a celebrated performer in Europe might be praised and idol-ized at the time. Technical proficiency on an instrumentçwhether non-European orEuropeançand interculturally recognizable excellence in musical interpretation werebeginning to manifest themselves as yardsticks by which any nascent notions ofhuman egalitarianism could be measured.

IV. EMPATHY AND ANTIPATHY

Anthony Pagden has noted that ‘sixteenth- and seventeenth-century observers . . . livedin a world which believed firmly in the universality of most social norms and in ahigh degree of cultural unity between the various races of man’.54 This observation,made in reference to the origins of comparative ethnology, applies no less to musicthan to any other aspect of society or culture. Early modern European writers compar-ing other musics to their own often expressed sentiments of either empathy or antipathytowards foreign cultures when discussing the appearance, sound, or function of instru-ments. European orchestral instruments reached their relatively immutable forms (orholotypes) in the late nineteenth century, but in the early modern period the widescope for innovation in their designçand the vast array of variant instruments frome¤ lite and popular cultures alikeçmeant that travellers might be familiar with a greatrange of instrument types and playing styles. In turn, this allowed them to react morefavourably to the alien specimens that they encountered, at least in considering theirshape and size, if not their sound.For societies that would experience sustained contact with Europeans, either in the

context of colonial domination (as in the case of subjugated populations in Latin Amer-ica) or through regular trade (for example, Japan, until it closed its doors definitivelyto the outside world in 1639, with the exception of limited contact with quarantinedDutch traders), the similarities that were noted between certain Western and non-Western instrument types also implied the capacity of non-Europeans to take up Euro-pean instruments. In the eyes of colonialists, this transcultural ability would also there-by demonstrate non-Europeans’ propensity to adopt other aspects of European culture.When the Jesuit Matteo Ricci observed a Confucian ceremony in the early seventeenthcentury, he considered Chinese court practices to be comparable with those ofEurope.55 He even seemed to imply that instrumentalists who had the technique to

53 Francis Fowke (1753^1819), the eldest son of a wealthy East India Company employee and free merchant, was akeen amateur musician, and resided in Benares, Chinsura, and Calcutta from 1773 to 1786. He collaborated with hissister Margaret (1758^1836) in broad enterprises that aimed at developing understanding and appreciation of Indianmusical cultures. See Ian Woodfield, ‘The ‘‘Hindostannie Air’’: English Attempts to Understand Indian Music in theLate Eighteenth Century’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 119 (1994), 189^211; T. H. Bowyer, ‘Fowke, Joseph(1716^1800)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004)5http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/635604,accessed 9 Jan. 2009.

54 Pagden,The Fall of Natural Man, 6.55 See Matteo Ricci, SJ and Nicolas Trigault, SJ, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Iesu: Ex P.

Matthaei Ricij eiusdem Societatis co[m]mentarijs, libri V. ad S. D. N. Paulum. V . . .Auctore N.Trigautio (Augsburg, 1615), 369;English translation in Oliver Strunk, Source Readings in Music History, rev. edn., ed. Leo Treiter et al. (NewYork andLondon, 1998), 507.

387

play Chinese instruments such as the pipa and the sheng could apply their skills to theequivalent European instruments. For Ricci, the same ran true for philosophical andintellectual capacities, and in his mind’s eye he positioned the Chinese scholarly classas ripe for conversion. In a similar vein, Juan de Torquemada compared the religiousrituals of pre-Conquest Mexico to those of Catholic Europe, citing similaritiesbetween the use of instruments to summon worshippers or adorn devotions, therebyidentifying pre-existing structures onto which the Christian religion could be grafted.56

The use of musical instruments was recognized as a cultural characteristic that wascommon to all human societies, yet the presence of instruments in one society in noway defended it from enslavement or annihilation by another. The most acute demon-stration of this reality is obviously to be found in Africa, where complex instrumentswere observed by early modern Europeans,57 but where entire communities wereapprehended by slavers for transportation to the Americas. As we shall see, the inher-ent ingenuity in instrument design in the African diaspora could not be suppressed,even after enslavement and trans-oceanic relocation, during which all that slavescould take with them were their cultural memories. These memories resulted in theconstruction of many African instruments in the Americas, among which figured xylo-phones and gourd-resonated bows.58

Certain other non-European populations were treated with great deference, however,particularly where potentially lucrative trading agreements were at stake. In a morepeaceful type of trading mission, a French delegation to Siam in the 1680s presentedFrench music (‘several Airs of our Opera on the Violin’) to the kingçwho received itwith indifference (‘he did not think them of a movement grave enough’)çand witnessedperformances of Siamese music. The leader of the group, Simon de la Loube' re, reporteddisparagingly that ‘their Instruments are not well chose [sic], and it must be thoughtthat those, wherein there appears any knowledge of Musick, have them brought fromother parts. They have very ugly little Rebecks or Violins with three strings, which theycall Tro, and some very shrill Hoboys which they call Pi, and the Spaniards Chirimias.’59

However, he was encouraged by the impression made on the Siamese by Europeaninstruments: ‘The Siameses do extreamly love our Trumpets, theirs are small and harsh,they call them Tre.’60 To La Loube' re, favourable reactions of another people to his ownmusical instruments indicated apparent willingness to engage in cultural exchanges overand above that of trade. Just a few years before this mission, Louis XIV himself had

56 See Juan de Torquemada, Parte de los veynte y un libros rituales y Monarchia Indiana con el origen y guerras de los IndiosOccidentales de sus poblac� ones descubrimiento, conquista, conversion y otras cosas maravillosas de la mesma tierra (Madrid,1723; ori-ginally published Seville, 1615), quoted in Harrison,Time, Place and Music, 27^8, 39.

57 See, for example, a description by Denis de Carli of a Congolese xylophone with gourd-resonators in MichaelAngelo and Denis de Carli, ‘A Curious and Exact Account of a Voyage to Congo in the years 1666 and 1667’, in ACol-lection of Voyages and Travels, ed. Churchill, i. 622.

58 See Montagu, Origins and Development, 10, 196.59 Simon de La Loube' re, A new historical relation of the kingdom of Siam by Monsieur De La Loubere, Envoy Extraordinary

from the French King, to the King of Siam, in the years 1687 and 1688, trans. A. P. Gen. R. S. S., 2 vols. (London, 1693), PartII, 68; also quoted in Harrison,Time, Place and Music, 87. Original text: ‘Leurs instruments ne sont pas d’ailleurs bienrecherche¤ s, et il faut croire que ceux ou' il para|“t quelque connaissance de la musique leur sont venus de dehors. . . .Ils ont de mauvais petits rebecs, ou violons a' trois cordes, qu’ils appellent tro“ , et des hautbois fort aigres qu’ils nommentp|¤ , et les Espagnols chirimias’; cited in Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, E¤ tude historique et critique du livre de Simon de la Loube' re‘Du Royaume de Siam’çParis 1691 (Paris, 1987), 269^70. It is worthy of note that La Loube' re identified certain Siameseinstruments as chirim|¤as (Spanish shawms); these were probably examples of similar-looking Siamese shawms calledPi chawa. Diplomatic missions sent from Spanish Manila to Siam in the 17th and 18th cc. probably included playersof chirim|¤a among their musical personnel, thus effecting mutual recognition of the instrument’s ceremonial roleand facilitating intercultural negotiations.

60 La Loube' re, A new historical relation of the kingdom of Siam, Part II, 69.

388

attempted to emulate Siamese sonic rituals in Versailles for the reception of an embassyfrom Siam, in order to foster good relations between the two countries.61

Although intercultural encounters sometimes resulted in empathetic observations, atother times it was the alien musical aesthetic and the differences in the physicalmake-up of instruments that were emphasized by Europeans. Observations on strings,for instance, provided a theme for endless speculation and comparison. Such aspectsas numbers of strings or playing technique were noted: in Japan, for example, theJesuit Lu|¤ s Fro¤ is commented in the late sixteenth century that ‘our vihuelas have sixstrings, without counting the double courses, and we play [pluck] them with the hand[fingers]; those of Japan have four, and they are played with a sort of plectrum’.62

The materials used for strings could also impart particular cultural significance, or re-flect environmental differences. For example, Le Chevalier Jean Chardin claimedthat in Persia ‘the strings of their instruments are not gut, as ours are, because withthem it is a contamination in law to touch dead parts of animals; their instruments’strings are either of twisted raw silk or of spun brass’.63 On the other hand, some morepejorative judgements about materials used for strings point to lack of knowledge or a‘wasted opportunity’ on the part of non-Europeans; Ricci commented, for instance,that the use of silk strings (which he called ‘twisted cotton’) in China implied ignoranceof the musical uses of animal guts.64 But we should remember that the use of onestring type rather than another neither confirms nor denies knowledge of particularstring-making techniques; it is merely reflective of a common practice that has pre-vailed in accordance with other dimensions of a musical culture that is steeped in trad-ition rather than dependent on (or expectant of) innovation.In terms of sound quality, silk strings were nevertheless sometimes considered to be

on a par with gut, at least when they were used on European instruments. The JesuitDiego de Bobadilla wrote in around 1640 that the strings of the guitars and harpsplayed by indigenous musicians in the Philippines ‘are made of twisted silk, and pro-duce a sound as agreeable as that produced by our [type of] strings, even though theyare made of quite different material’.65 Once the knowledge of silk strings was trans-mitted to Europe, and raw materials imported and manufacturing techniques devel-oped, silk strings were adopted by some European musicians for use on plucked andbowed instruments, and in this context they have fluctuated in favour from the seven-teenth century to the present day.66

61 See Ronald S. Love, ‘Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Ver-sailles in 1685 and 1686’, Canadian Journal of History, 31 (1996), 171^98.

62 ‘As nossas violas tem seis cordas afora as dobradas, e tanjen-se com a ma‹ o; as de Japa‹ o 4 e tanjen-se com humamaneira de pentes.’ Lu|¤s Fro¤ is, SJ and Josef Franz Schu« tte, SJ, Kulturgegensa« tze Europa-Japan (1585):Tratado em que secontem muito susinta e abreviadamente algumas contradic� o‹ es e diferenc� as de custumes antre a gente de Europa e esta provincia deJapa‹ o (Monumenta Nipponica, 15; Tokyo, 1955), 246.

63 English translation in Harrison,Time, Place and Music, 132. The original text reads: ‘Vous observerez, que lescordes de leurs Instrumens ne sont pas des cordes a' boyau, comme aux no“ tres, a' cause que chez eux c’est une impurete¤legale de toucher aux parties mortes des animaux: leurs cordes d’Instrumens sont, ou de soye crue« retorse, ou de fil d’archal.’Jean Chardin,Voyages de Monsieur le Chevalier Chardin, en Perse, et autres lieux de l’Orient, 3 vols. (Amsterdam,1711), ii. 115.

64 ‘Fides instrumentis omnibus adhibent e' cruda bysso retortas, ex animalium fibris ne confici quidem possenorant.’ Ricci and Trigault, De Christiana expeditione, 21.

65 ‘Sont de soye torse, & rendent un son aussi agre¤ able que les nostres, quoy qu’elles soient de matie' re bien diffe¤ r-ente’. In ‘Relation des Isles Philippines, Faite par un Religieux qui y a demeure¤ 18 ans’, in The¤ venot, Relations dedivers voyages curieux, i. 5.

66 Mersenne and other theorists make mention of this alternative to gut or metal. See Patrizio Barbieri, ‘Romanand Neapolitan Gut Strings 1550^1950’, Galpin Society Journal, 59 (2006), 147^81 at 170.

389

Just as material components of instruments could be reassigned from one instrumen-tal culture to another, some early modern scholars believed that playing techniquescould be similarly transposed. Burney noted in 1776 that ‘the New-Zealand trumpet,though extremely sonorous, is likewise monotonous, when it is blown by the natives,though it is capable of as great a variety of tones as an [sic] European trumpet’.67 Evi-dently, a local (European) trumpeter had been commissioned by Burney to test theharmonic series on the Ma~ori instrument. But we can see that since the physics of a vi-brating column of air apply universally, the technical capabilities of a European nat-ural trumpet and a Ma~ori pu~ta~tara or pu~ka~ea would differ only according to theirlength, width, and bore. More significantly, the range of notes used by different music-al cultures would depend on the instrument’s function, the local society’s aestheticrequirements, and the musicians’ sensibilities.Nevertheless, European scholars still assumed that professional instrumentalists were

best placed to probe into the mysteries of the non-European instruments with whichthey were presented. In 1775, the Irish musical theorist Joshua Steele published hisreport on ‘the curious system of pipes, brought by Captain Fourneaux from the SouthSeas’ (Pl. 4). He commented that ‘the instrument was so new to me, that I should besorry its reputation should rest intirely [sic] on my report, as I think an expert blow-er of the German flute might make further discoveries’.68 By overblowing and produ-cing octaves and tierces above the fundamentals of most pipes, Steele was able to con-struct a series of nineteen notes, ‘sufficient for an infinite number of airs’ from ninepipes of seven different pitches.69 It is evident that some Europeans, like Steele, wereable to empathize with exotic instruments only when they could be accommodatedwithin European modes of musical theory and practice.70 The sort of Eurocentrism ex-emplified here by Steele is apparent in many other examples of early modern compara-tive organography, and we can see that the standards by which late eighteenth-centuryscholars sought to judge non-European instruments and their music were often basedon unrealistic parameters constructed by an oversimplification of non-European music-al systems and aesthetics. But we should remember that it was undoubtedly also basedpartly on a genuine desire to know and appreciate foreign technology and artistry.Some exotic instruments were (re)constructed specifically for inclusion within Euro-

pean music as a means of evoking faraway times or places, producing sounds that pre-sented a direct contrast to the musical norms of early modern Europe. Ruth Smithhas shown that Handel commissioned the building of a‘tubalcain’or carillon, supposed-ly after the style of the ancient Hebrews, for use in his oratorio Saul.71While the musicwritten for this instrument is typically Handelian, the tubalcain evoked for Handel’saudience the sound of the ancient Near East. Non-European instruments were gradual-ly adopted for percussion in large-scale works from the seventeenth century onwards;as early as 1680, for instance, Nicolas Strungk used cymbals in the orchestration of his

67 Burney, A General History of Music, i. 216.68 Joshua Steele, ‘Account of a Musical Instrument,Which Was Brought by Captain Fourneaux from the Isle of Am-

sterdam in the South Seas to London in the Year 1774, and Given to the Royal Society’, Philosophical Transactions, 65(1775), 67^71 at 67.

69 Ibid. 70.70 On contemporary criticism of Steele’s comparisons, see Irving, ‘The Pacific in the Minds and Music of Enlight-

enment Europe’, 211^14; and Agnew, Enlightenment Orpheus, 114.71 Ruth Smith, ‘Early Music’s Dramatic Significance in Handel’s Saul’, Early Music, 35 (2007), 173^89 at 175^6.

390

opera Esther.72 Quite apart from the quite frequent use of Turkish instruments in Euro-pean Scores, more exotic borrowings included the use of South Sea percussion instru-ments in John O’Keeffe and William Shield’s pantomime Omai: Or, a Trip Round the

PL. 4. A ‘curious system of pipes, brought by Captain Fourneaux from the South Seas’, inJoshua Steele, ‘Account of a Musical Instrument’, 68. Reproduced by kind permission of theSyndics of Cambridge University Library

72 Blades and Montagu, Early Percussion Instruments from the Middle Ages to the Baroque, 18.

391

World (1785),73 and Aztec ‘Ajacatzily’ (ayacachtli) by Gaspare Spontini in his opera Fer-nand Cortez, ou La Conque“ te du Mexique (1809).74 This fetishization of non-European per-cussion became a means of symbolizing distant musical cultures and evoking exoticsound-worlds on the European stage. But it could be argued that in the early modernperiod it acted predominantly as a colourful percussive veneer that had little effect onEuropean tonality or compositional structures.

V. RECIPROCITY

Although we have focused so far on European encounters with the ‘Other’, it is import-ant to acknowledge that early modern organological comparison was by no means aone-way process. Non-Europeans also encountered the alien instruments and practicesof Europe, and assessed them in accordance with their own musical systems. Some-times their responses were favourable, but they could equally react with indifferenceor scorn. Relatively few reactions were recorded, but many were related by Europeans,who may have been interestedçor amusedçto see reflections of themselves offeredby this mirror of alterity. Of course, reports written by non-European scholars andread without the filter of subsequent European interpretation are likely to be more reli-able representations of non-European reactions.The location and interpretation of add-itional examples of non-European reactions to early modern European music wouldno doubt inform or change our perspective of Europe’s place in the early modern mu-sical world.In 1711, Le Chevalier Jean Chardin reported his interrogation by a devout Muslim

who queried aspects of instrumental practice in the Christian religion:

The Chief Steward, who was Mohhamadan by birth, came to me and asked if the useof instruments were [sic] permitted in our religion. I told him it was. He replied that theMohhamadan faith forbad [sic] it quite expressly. We had a half-hour’s discussion on thissubject, in which that gentleman confirmed something I had learnt a long time before, thatmusical instruments were forbidden by Mohhamad, and that although their use was universalthroughout Persia, it was nevertheless unlawful. He told me further that instruments wereabove all prohibited from religious use, since it was only with the human voice that Godwishes to be praised.75

To the Chief Steward, Chardin probably represented a culture and a religion thatflaunted the teachings of the prophet Mohammed, but as ‘unlawful’ usage of instru-ments was likewise practised by his fellow believers throughout Persia, their discussionprobably proceeded on grounds that were not judgemental in nature. In his response,Chardin may even have empathized with the steward, informing him that the voicewas indeed the primary instrument of praising God in Europe, citing more than a mil-

73 John O’Keeffe, A Short Account of the New Pantomime called Omai: or, ATrip Round theWorld, A new edition (London,1785), 15.

74 Stevenson, ‘Aztec Organography’, 4.75 Translation in Harrison,Time, Place andMusic,128.The original text reads: ‘Durant ce tems-la' , le premier Ma|“ tre

d’ho“ tel, qui e¤ toit Mahometan de naissance, s’approcha de moi & me demanda, si l’usage des instrumens e¤ toit permisen no“ tre Religion? Je lui dis qu’il l’e¤ toit. Il me repliqua, que la cre¤ ance Mahometane le de¤ fendoit bien expresse¤ ment.Nous eu“ mes un entretien de demie heure sur ce sujet, dans lequel ce Seigneur me confirma ce que j’avois apris il y along-tems, que les Instrumens de Musique sont de¤ fendus par Mahomet; & qu’encore que l’usage en soit universeldans toute la Perse, il ne laisse pas d’e“ tre illicite. Il me dit encore, que les Instrumens e¤ toient sur tout prohibez dansla Religion, n’y ayant que la voix de l’homme avec laquelle Dieu vouloit e“ tre loue¤ .’ Chardin,Voyages de Monsieur le Che-valier Chardin, i. 142.

392

lennium of chant traditions. Speculation aside, however, it is likely that interculturalexchanges in Eurasia were sufficiently old and regular for Christians and Muslims tohave formed a general impression of the place of music in each other’s religioustraditions.For non-European observers, the unfamiliar was sometimes cloaked with the famil-

iar; for example, they sometimes saw their kin or compatriots playing European in-struments. In regions where the stakes for evangelistic success were high, these sortsof encounters were often deliberately orchestrated by European missionaries, whosought to impress on ‘gentiles’ who had not yet converted that adaptation or conversionwas a benign process that had other cultural benefits. When a combined Japanese^Jesuit embassy to Europe returned to Japan in1590, the Jesuit superiors eagerly awaitedan audience with the taiko~ (regent) Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536^98), which they weregranted the following year. A programme of European music to be performed byfour Japanese converts, who had travelled to Europe as part of the embassy, was devisedto beguile the ruler. This aim was achieved with some success, as Fro¤ is relates:

At last, Toyotomi returned to the visitors. . . . They talked of various things, and he said thathe wanted to hear the four gentlemen play some music. Then the musical instruments werebrought, which had been prepared in advance. The four gentlemen began to play and sing tothe cravo [harpsichord], the arpa [harp], the laude [lute], and the rabequinha [fiddle]. They per-formed very gracefully because they had learned much in Italy and Portugal. He listened tothem with great attention and curiosity. The envoys stopped playing soon after they began inorder not to cause trouble to the ruler. He ordered them to perform three times on the sameinstruments. Then he took each instrument in his hands, and asked the four princes questionsabout the instruments. He further ordered them to play the violas de arco [viols] and the realejo[reed organ]. He examined them with great curiosity. He told various things to the gentlemen,and said that he was very happy to find them to be Japanese.76

Hideyoshi, who generally resented many aspects of European influence in his domain,evidently welcomed foreign artistry and technology. Moreover, in this account heseemed genuinely pleased that his young compatriots had taken advantage of pro-curing knowledge and skills from afar. But his curiosity appears to have stemmedfrom the differences that he noticed between their European instruments and those oftraditional Japanese usage. However, instruments did not save the Roman Catholicmission from orders to its detriment that were later given by Hideyoshi, which culmi-nated in the martyrdom of twenty-six European and Japanese Christians at Nagasakiin 1597, and continued the following year with the demolition of churches, seminaries,and religious houses.77