Chennai Beautiful

-

Upload

uni-heidelberg -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Chennai Beautiful

Fig. I Cinema posters and political slogans on a wall. Brick Ki ln Road, Chennai, April 20 I 0.

All photographs in this essay are by the author, unless specified otherwise.

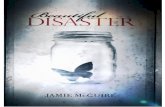

Chennai Beautiful Shifting urban landscapes and the politics of spectacle

Roos Gerritsen

A11 area 111ea11t forpreservi11g gree11e1J' f?J1 the Agric11lt11ral Depa1t111ent opposite to the Ge111i11i j/yover has been co111pletefy blocked fro111 the vie11J of the p11blic f?J1 h11ge adve1tise111e11t hoardings ....

]11st opposite to the High Co111t i11 front of the Bar Co1111cil Office there is a11 adve1tise111e11t boa1d 1JJhich is placed across the pave111e11t, ca11si11g 1111isa11ce to the traffic a11d the pedestJia11s. If 011e goes

do1JJ11 the N1111ga111bakka11 B1idge t01JJa1ds Poo11a111allee High road, 011e ca11 see a long ad1mtise-111e11t boa1d 1JJhich 11111st be abo11t 300 feet i11 the length . . .. lf?'e are 11ot even //Jonied abo11t the ob

scene advertise111e//ts, 111ostb1 l?J1fil111 prod11cers a11d Ci11e111a theatres, 1JJhich ca11 be taken care of l?J1 approp1iate existing legislation. B11t //JC are 11Jonied abo11t the size and location of the i111111111erable hoardings si111pb1 spo1Ji11g the aesthetic bea11!J1 of the Ci('y and so111e of the JJ1odem b11i/rli11gs 1JJhich

have (been) b11ilt a1tistically 1JJith the help of architect11ral expe1ts.

~Excerpt from High Court Document 2006 1

The state of Tamil Nadu is well known, even notorious, for the elaborate decoration

of billboards, murals, and posters featuring mostly actors and politicians that appear

in tl1e public spaces of its cities and towns (Fig. 1). This culture of what many see as

excessive display stems from an intimate and long-lasting relation between tl1e fields

of politics and cinema, with several actors and others from tl1e Tamil movie industry

pursuing political careers.2 The political leaders who gained eminence in tl1e state have

always been ubiquitously displayed across cities and towns ilirough iconic in1ages, party

colours, and slogans on walls, metres-high billboards and cutouts, and numerous

posters. What is important to note is that tlus kind of imagery is not merely organized

by the parties' leaders but is mostly displayed on the initiative of lower-level party

183

supporters. Political supporters coming from

lower socio-economic classes use this visibil

ity not merely to promote their party loyalty

but to make themselves visible as well.

Fig. 2 Artist working on a beautification mural. The series he is working on depicts the story of Kannagi and is copied from the famous Amar Chitra Katha comics. Greenways Road, April 20 I 0.

Even. though the presence of such spec

tacular images is widely taken for granted, the

High Court document quoted above alerts us

to the recurring rhetoric of agitation against

them in the Tamil public realm. Newspapers

regularly report on the physical dangers

posed by these ubiquitous images to pedes

trians struggling to navigate their way around

them (as these are often placed across pave

ments and footpaths), and to drivers unable

to see traffic signals that are obstructed by

such billboards. Furthermore, it is claimed

that young viewers in particular are distracted

by the stunning, frequently eroticized, stills

taken from new movie releases. In 2009, in

tl1e wake of extensive criticism about the de-

184

facing of public and private walls by political parties and others, the Chennai city ad

ministration attempted to intervene in the elaborate visual encroachment on its streets

and initiated campaigns to regulate the 'pollution' caused by unauthorized forms of

pictorial display within the city. From mid-2009 onwards, the city authorities decided

to enforce a ban on posters, murals, and hoardings on two of the main roads running

through the city. Billboards were pulled down and walls cleaned of posters and white

washed, covering up the remains of the once ubiquitous murals. To beautify these

roads, artists were commissioned to cover the walls with images of Tamil cultural her

itage and natural scenery (Fig. 2). Chennai's mayor, l'vI Subramanian declared, 'images

of various cultural symbols would be painted on compound walls of government

property on the two roads .... This is intended to keep those who paste posters away

and improve aesthetics. Posters are an eyesore'.3 Anna Salai and another road in the

city were chosen to launch pilot projects for a larger beautification initiative. On the

Visual Homes, Image Worlds

success of the pilot, the project was extended to the entire Chennai Corporation limits

a year later. Today, more tl1an 3,000 public walls are prohibited from being used for

posters and the like.4 Tvioreover, Chennai is being 'embellished' more and more with

beautification murals: main roads, junctions, and flyovers are decorated witl1 in1ages

of cultural and natural settings, providing parts of the city witl1 a new look.

As can be understood from tl1e Mayor's words, the reason for installing tl1e beau

tification murals is tl1e rising agitation over an absence of what is deemed to be aes

thetic, and over tl1e excessive display of hoardings and other public images. In this

essay, I argue instead tlut it is the needs of Chennai's growing neo-liberal economy

tl1at have catalyzed tlus 'beautification' plan. The new murals are in fact part of a larger

beautification and gentrification initiative by tl1e city, in wluch Chennai is clearly pre

senting itself as being on its way to becon1ing a 'world class' city. I explore how the

new beautification murals can be linked to tl1ree interrelated processes that are part

of tlus 'neoliberal turn'.

The first context of change is Chennai's positioning as a 'world class' city that will

attract capital investors, and, related to tlUs, tl1e emergence of increasingly affluent, neo

liberal, nuddle-class publics. '\Xlorld class' can be understood as a global imaginary ex

pressed, for instance, in arclutecture and tl1e built environn1ent, spectacular and exclusive

public spaces such as shopping malls, as well as in the aspirations towards cosmopolitan

lifestyles or globalized consumption.5 The imaginaries of world class seem to have be

come tl1e incentive for many beautification and urban renewal projects. Tlus has lead to

the increasing visibility of the new n1iddle classes in urban space, as well as the brushing

away of selected parts of tl1e city, such as slums, or inhabitants such as street vendors,

wh~ pose a problem for such an image. The gentrification of the city is part of new

'spatial strategies' in the urban environment that create or reinforce social distinctions.6

Second, following Abidin Kusno,7 I propose that the new beautification images

suggest social and political identities as well as reinforce old political ideologies. The

particular history of image display in Tamil Nadu, in which urban space has been used

extensively for political and cinematic publicity purposes, is strongly entangled with

the conventional political practices of the State. Now, just as public space demands

gentrification and beautification in order to attract foreign investors, the political system

demands an image cleanup as well, as populist politics is deemed inappropriate in a

neo-liberal environment. Therefore, public spaces as canvases for conventional political

Chennai Beautiful 185

practices have to be cleansed of the suggestions of populist politics. At the same time,

however, the beautification murals with their focus on Tamil or Dravidian history and

their mural form seem to reinforce the parties' focus on ideological Dravidian origins

and identity, only now more focused on a generic Tamilness.

This brings me to the third process. The murals are aimed at rebuilding present

day Chennai and its image for an aspired future. At the same time, they embody nos

talgia for the past rooted in the image of a collective history and identity. As Chennai.

aspires to become a world-class city through urban renewal and novel architecture, the

beautification murals mostly refer to the 'traditional' past. I suggest tl1at tl1e murals

figure as monuments of collective identity and memory8 through which a uniform,

idealized, and consumable hjstory and future can be (re)installed or (re)created. As

hyper-real objects,9 tl1e murals seem to cater to the desires of the new, affluent middle

classes to consume 'tradition' in a simplified 'postcard' history, a process which I will

refer to as neo-nostalgia. 10 Because tl1ey have become consumable historical narratives,

tl1ey actually become more potent tl1an tl1at to whkh tl1ey actually refer. l'vioreover,

tlus history, assembled from fractions of cultural values and moralities, is deemed lost

by tl1e city autl1orities in urban lifestyles, and tlrns in need to be instructed as well.

Taking these tlu:ee processes together, the production of murals indicates a move

on part of tl1e city authorities to embrace neo-liberalism and its publics tl1rough an

Fig. 3 Artist Mumusamy working on a beautification mural that depicts poetry from the Sangam Age. Poonamallee High Road, February 20 I 0.

186 Visual Homes, Image Worlds

emphasis on the aes

thetic and tl1e tradj

tional while sidelining

conventional political

practices and loyalties.

The murals turn the

city into a postcard

spectacle-a spectacle

of aspirations, nostal

gia, beauty, tradition,

and moral pedagogy.

They exemplify the

shift from more com

mon uses of public

space and taste to elitist visualities. In the meantime, unauthorized or 'spontaneous'

uses of public space are being replaced not only by sanitized, beautified images, but

also by otl1er new imaginings and desires.

Reflecting the essence of Tamil culture?

The renowned hoarding artist, JP Krishna, was the first to be commissioned by the

Chennai Corporation 11 to paint several walls as part of the beautification injtiative.

The images that he painted on Anna Salai all refer to Tamil culture and heritage, and

the natural beauty of tl1e state (Fig. 3). Most of tl1e murals build on tl1e style of realistic

paintings initiated by Raja Ravi Varma in tl1e late 19th century, and later on adapted,

popularized, and commercialized in calendar art and cinematic and political hoardings.

Among other subjects, tl1e images include tl1e UNESCO heritage site of Mamallapu

ram (Fig. 4), the statue of the classical Tamil poet and saint, Thiruvalluvar at India's

southernmost tip, Kanyakumari, several temples and temple sculptures, and performers

of Carnatic music (Fig. 5). Anotl1er stretch of paintings on one of the large intersec

tions in tl1e southern part of the city depicts tl1e m}rthological story of Kannagi, tl1e

heroic woman character of the epic Silapathikara111 (Fig. 2) . The artist conurussioned

to paint tl1e story used tl1e version that appeared in tl1e popular A111ar Cbitra Katha

comics as an example. 12 He made slight changes to the images of tl1e cartoon (sans

Fig. 5 Beautification mural made by artist JP Krishna depicting a musician. Anna Salai, May 2009. Photograph by McKay Savage.

tl1e balloons), and tl1e

last image of this se

ries is a copy of the

Kannagi statue on

]\farina Beach. 13 Fig.

2 in fact 'shows the

artist using a page

copied from the

Alllar Chitra Katha

cartoon of Kannagi

that he used as a

model to paint one

of the scenes.

The Corporation selected these images to use for the murals and carefully moni

tored the painting process. For the first few stretches of walls, they authorized the use

of a book containing paintings by Tamil artists that depict scenes of Tamil heritage

and nature. Initially the Corporation planned to commission students of the Govern

ment College of Arts and Crafts; it was they who had actually proposed this plan to

the government. 14 Paradoxically, however, the city authorities ended up commissioning

former hoarding artists to paint the scenes. I call it paradoxical because the same artists

who previously flourished within the 'cut-out culture' and benefited from the com

missioning of numerous political murals subsequently saw their income disappear as

political parties fought each other by imposing restrictions on cutouts. Within the cur

rent context of beautification, these former hoarding artists have now been commis

sioned to replace their own work on the city walls.

In fact, the artists receive a relatively good salary for the beautification murals

(around Rs 35 per square foot), a sum that is much higher than what they were being

paid (around Rs 10 per square foot) for political murals during the last several years. 15

The artists I spoke to actually appreciated the work, not only because of the money

they were earning with the murals but also because of the positive reception they get

for their work. Passersby often stop at the scene where they are working and praise

them for their efforts. Moreover, several artists indicated that they enjoy creating new

kinds of images after endlessly painting portraits of the same politicians.

188 Visual Homes, Image Worlds

According to tl1e Corporation, tl1e images should reflect Tamil culture. One of

the artists who was commissioned to paint tl1e new murals found tlut not everything

belongs to Tamil culture as tl1e Corporation sees it. Along witl1 some colleagues, Raj

was commissioned to paint a public wall, around 270 metres long, on Rajaji Salai, close

to tl1e former seat of Government in Fort St. George. He explained to me how he

and his colleagues often sketched scenes from daily life in their own environment- a

sunrise at Marina beach, a street vendor selling ice cream to a young boy, or a rag picker

picking recyclable garbage off the streets. For Raj and his colleagues, tl1ese scenes ex

press tl1e real and typical Chennai. He suggested to the Corporation officer who was

in charge of the project tl1at he would like to paint tl1ese kinds of everyday life scenes,

but the officer refused such a commission because in his view such images did not

correspond to what they regarded as 'Tamil culture'. Remarkably, however, in tl1e light

of the emphasis on 'traditional' culture, the Corporation permitted tl1e inclusion of a

man playing golf on one of the city walls (Fig. 6). Even tl1ough tlus painting was com

missioned by tl1e local golf course, it was sanctioned by tl1e Corporation and integrated

into tl1e series of paintings comnussioned for this road. Later, when I asked about this

particular image, tl1e Corporation officers in charge appeared slightly embarrassed re

garding what tl1ey now deem a 'mistake'. Such 'mistakes' cannot be explained merely in

I I i

190

Fig. 7 Man lighting a cigarett in front of beautification mtit'al of doctor looking at an X-ray. Compound wall in fro t of the government hospitrl, Ponnamallee High Road, March 2010.

terms of a distinction between 'traditional' and 'modern' images, as various other in

dustries or technologies have been showcased on the public walls. The compound wall

of a government hospital, for example, shows us images of doctors looking at X-rays

(Fig. 7) and an operation chamber; these images are placed next to a panel in which heal

ers are shown using Ayurveda (a health care technique with growing popularity across

India, and in particular in the southern states) (Fig. 8). The image of golf play, however,

had been privately commissioned by the golf course. My suggestion is that whereas doc

tors and X-rays reflect contemporary icons of the state, a golf player is an image of af

fluent consumption and urban spatial aesthetics and, therefore, does not fit in the range

of themes that express the achievements and highlights of the state.

Shifting publics: New images of world class imaginations

'Beautification' is nothing new or specific to Chennai. Other Indian cities are working

on their appearance in similar ways, also initiating new paintings depicting regional

cultural scenes. 16 \Xi'hat is happening in Chennai, however, is somewhat different, as

this is not merely an attempt to beautify the city by means of wall paintings but also

involves a rigorous-and almost iconoclastic-prohibition of every kind of billboard,

even commercial ones, on these 'corridors' in the city. Chennai's new look indicates

that the city is claiming and restructuring forms and appropriations of public space,

Visual Homes, Image Worlds

Fig. 8 Beautification mural next to the one of the Doctor looking at the X-ray. This one depicts an ayurvedic healing scene. Poonamallee High Road.January 2010.

first in the form of beautifying the city through murals, and thus aligning it to a dif

ferent form of aesthetic experience and urban imaginary, and second, through the bu

reaucratic interpretation of culture that embraces capital investments. In this way, a

distinct and selective image of the city is imposed, but whose image of the city is it?

The following quote is instructive for what it reveals of the paradox inherent in the

idea of reflecting Tamil culture. The author aptly pinpoints the ubiquitous presence

of political imagery in Tamil Nadu's visual culture .

. . . Thiruvalluvar, Mamallapuram and Bharatanatyam do contribute to t11e culture

of the state, tlrns how can you call it t11e essence of Tamil culture wit11out the

colourful politicians? Always on the walls of Mount Road, t11ey were t11e friendly

neighbourhood Spidermen of Chennai. I miss Kalaignar [respectful artist] .Mutlrn

vel Karunanidhi in his trademark dark glasses smiling down from vinyl billboards

at t11e Thousand Lights traffic jam. I feel mot11erless as I stare into the void left

behind by the cut-outs of Amma [mother] alias J Jayalalithaa on Mount Road.

\Xfhen my boss says I lack aggression, how do I convince him it is because t11ey

have removed all the posters of Vaiko whose roar for t11e dead tigers of Lanka

used to instil a revolutionary zeal in me on my way to edit meetings? 'Karuppu

[black] MGR' Vijaykant11 has been whitewashed; S Ramadoss has been shredded.

On the smaller roads and bylanes, however, they all t11.rive in myriad forms. 17

Because of Tamil Nadu's specific historical background, of which public political

imagery has been an essential part, t11e restrictions on it today raise questions about

how the political landscape is changing. Until now, it has always been argued that po

litical parties triumph because of t11eir ubiquitous presence in the public realm. It is

Chennai Beautiful 191

192

striking though that it is politicians who have tried try to curb these images in the city;

indeed, they are the ones who initiated this visual regime of representation. Chennai

is the only city that has gone so far as to completely ban all billboards from its urban

milieu. It seems paradoxical that politicians are now in favour of replacing their own

images with postcard images of historical and natural scenery. This is even more sur

prising since in official political discourse the images of the Chief l\!Iinister,

Karunanidhi and his successor, Stalin appear almost everywhere. The streets of Tamil

Nadu are swamped with their pictures during party rallies, inaugurations, or state-or

ganized events. The paradox here is that on the one hand the people who vote for

Karunanidhi's party are rejected or by-passed by the restrictions on their appropriation

of images of adulation and publicity. And on the other hand, the city administration

· continues to use the same kinds of images within a discourse of 'official' politics.

Political parties in the state are still largely dependent on support from lower socio

economic classes, and this makes the politics of visibility necessary after all. The re

jection of grassroots images by political rulers, however, suggests an act of distancing

from the political praise and linkages that these images symbolize and sustain. In fact,

this kind of political practice is deemed populist and does not fit in the neo-liberal

economy that the city is also aspiring to adopt.

The beautification murals as part of a larger gentrification project taken up by the

city can be situated in Chennai's aspirations to become an attractive, world-class city. 18

This was given initial impetus by the former mayor, MK Stalin, son of current Chief

Minister, Karunandhi, initiating the Si11gara [beautiful] Chennai plan, in which parts of

the city were to be beautified and made attractive to economic investors. Chennai realizes

its economic and global aspirations in conspicuous initiatives that selectively refurbish

the city: IT corridors, Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and beautification schemes in

volving the renovation and planning of roads and parks, the erection of large statues,

and, as I show here, the embellishment of public walls. The aspiration to become a

world-class city is informed by envisioning of the future and other cities that are taken

as models. Chennai uses the larger beautification project to emphasize its own attrac

tiveness and to root out unplanned encroachments that are seen as unsolicited uses of

the city. Local authorities in Chennai are actively erasing images of the city that do not

belong in this cosmopolitan view of being attractive or 'world class'. Publicity and visu

alities are put into play in order to pursue imaginaries and transformations of public

Visual Homes, Image Worlds

spaces, and they have become crucial tools for changing the image of the city and the

ways in which belonging to the city is defined. 19 In this regard, the city selectively at- .

tempts to push back the encroachment on public space by restricting its use.

Whereas on the one hand a certain segment of and practice in the city is being

curbed and set aside, on the other hand, the beautification images point to a shift in

attention towards another public. By becoming an attractive city for affluent investors

and citizens, Chennai seeks to reach an audience of middle-class professionals aspiring

to join the ranks of a global class of similar professionals. As slum dwellers are re

moved from sight within the city, the neo-liberal middle classes become much more

visible. The liberalization of the Indian economy in the 1990s has brought about a rise

in lucrative businesses and consequently, an increase in tl1e number of affluent mid

dle-class Indians. Several authors have indicated that the notion of middle class is used

as a marker by means of practices of distinction,20 tl1e wish to be visible, and of be

longing to a 'world class'.21 This desire for public visibility of the middle class expresses

itself in conspicuous consumption,22 but also in a political culture shifting from 'older

ideologies of a state-managed economy to a middle class-based culture of consump

tion.23 In this light, the golf player who has been inserted in the series of images would

actually not be an anomaly after all. This becomes more and more evident in the ma

terial form of the city, as Chennai is increasingly becoming a city selectively made up

of malls, multiplexes, housing enclaves, and IT corridors. In tlus regard, when we look

more closely at the spatial politics of tl1e new interventions we find that the city ad

ministration is mostly concerned with only that section of the city that relates to a

shift in the public. Several areas, or even corridors of the city, are being reorganized,

sanitized, and beautified partly to realize the global aspirations of this new public. In

the fringes of these corridors, as Arun Ram has already observed, political and com

mercial imagery thrive in myriad forms.

Aspirations for the future, nostalgia for the past

The aspiration to become a world-class city and to attract a middle class audience is

oriented towards a prosperous future, and informed by a reproduction and evocation

of the past through tl1e revival of postcard images of vernacular arclutecture, ritual

ized commemoration, and 'traditional' practices.24 As Christiane Brosius has pointed

out, the heterogeneous middle class negotiates concepts such as national identity and

Chennai Beautiful 193

194

'worldliness,' or tradition and modernity25 in which heritage and nostalgia can be uti

lized as markers of 'having tradition'. Brosius convincingly shows how being world

class is a 'rooted' cosmopolitanism, i.e., rooted in locality, heritage, and moral instruc

tion and consumption.26 In Tamil Nadu, the evocation of the past is more specifically

directed at the politics of Dravidian or Tamil linguistic heritage of the region. If

today Dravidianism has become a generic sign of Tamilness, in the past it was much

more closely tied to nationalist and linguistic projects in which Tamil Nadu distin

guished itself from the north of India in religious, cultural, and linguistic traditions.27

Political parties, particularly the DMK in its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, gained po

litical capital by staging themselves as guardians of the Tamil language and the Tamil

cause.28 The placement of ephemeral yet spectacular cutouts of cinematic and political

figures and more permanent monuments of historic figures has played an important

role in the construction of Chennai as a Tamil city as well as establishing the political

face and identity of these parties.29 The politicization and reproduction of monuments

or, as discussed here, beautification murals, actually emphasize the state's connection to

what it wants to represent and hence underscore its power.30 Just like monuments, the

beautification murals are a type of symbolic speech31 in which the authorities mediate

a common past and future. According to the Corporation officials I interviewed,32 the murals have two main

objectives. First of all, as I already suggested above, they are expected to keep away

people who want to use these walls for political or commercial purposes; hoardings

or billboards with this function are considered unsightly, and walls should now become

pleasant to look at. The second argument put forward by the Corporation is one of

cultural promotion and education. The beautification murals aim to show the rich cul

tural tradition of the state in the form of consumable heritage sites and cultural tra

ditions. \X!hat is interesting is tlut none of tl1e murals explicitly shows religious sites

or ritual interaction. Many sites or practices are associated with religious or ritual in

teraction, but in their representation on the walls tl1ey seem to operate independently

of that association. As postcard images, temples merely become heritage sites and Car

natic musicians are comically shown performing with their shoes on33 (Fig. 5). Instead

of drawing attention to tl1e lived aspect of traditions, the images emphasize the (touris

tic) in1portance of tl1e heritage of the state in a universal language of heritage. Just as

in museums tl1e status of an object changes, the iconic state of the murals turns them

Visual Homes, Image Worlds

from cultural materials into (art) objects.34 Now tl1e city itself has become a tourist

brochure or a selection of postcards, a spectacle from which tradition can be selectively

picked and consumed. The incorporation of tourists in some images (Fig. 4) reinforces

the relevance of tl1e monuments as heritage sites.

Besides turning Tamil Nadu into a site of spectacle and cultural promotion, the

Corporation indicates that cultural traditions should also be kept alive witllin the city.

The murals should teach the young about tl1e state's culture and historic past, some

tlling people supposedly forget when growing up in the city. The depiction of those

aspects of culture that are believed to pass into oblivion in the city and consequently

have to be revived, points to a nostalgic imagination of the past and the village. In

light of the booming economy for which Chennai is selectively refurbishing its city,

tl1e pedagogical aim of the murals, I suggest, is not necessarily directed only at the

younger generation but also a wider middle class audience. This may explain the ease

witl1 which the mural of the golf player was incorporated into the series of 'traditional'

settings, despite tl1e exceptionality of the mural within the series as a whole.

Since the envisioning of the village as tl1e repository of Indian culture by orientalist

scholars and figures such as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, it has become a privileged

trope in the imagining of the 'original' and 'real' India. Following from this vision,

cities are deemed degraded places that seem to have lost the wisdom, morality, and

harmonious lifestyle of the countryside. This rural lifestyle is believed to have disap

peared with tl1e mass movement to the city and should be passed on again to individ

ualistic and materialist city dwellers. These ideas about the new middle classes are

reflected in stereotypes, fuelled by media coverage, stating iliat tl1e rapidly growing young

middle class of IT professionals is leading this individualistic and materialist lifestyle

with all its negative connotations of materialism, sexual affairs, and an active nightlife.35

I am not interested in tracing iliese stories but I do think that the omnipresence of such

rumours and opinions actually reinforces the ideas about the middle class' lifestyle and

ilie city as a place of decay that is rapidly losing its traditional values and morals.

As a moral-pedagogical tool, the beautification murals fit in with ilie nostalgia for

the idealized, harmonious village and traditional ways of life. This nostalgia has come

to be envisaged and articulated in consumption patterns and lifestyles, and by themed

sites that noticeably refer to the past or rural life in films, theme parks, handicraft

exhibitions, heritage hotels, museums, craft villages, or ethnic chic.36 Mary Hancock

Chennai Beautiful 195

196

has coined the term 'neo-liberal nostalgia' to indicate how under neoliberal globaliza

tion, heritage-themed sites rearticulate the rural life worlds for cosmopolitan elites.37

These sites, she argues, have come to epitomize what modernity has displaced; they

serve as sanitized reproductions of rural life and the past. Hence, heritage is something

arising within capitalism and not against it; it is a _counter-narrative of the city, taking

place within the landscape of urban life. By showing images of Tamil heritage, rural

life, and the past, the new murals are part of this counter-narrative of neo-liberal nos

talgia. The patchwork of images from different periods, themes, and genres indicate

that this is not nostalgia for a specific period or past but for an arbitrary and assembled

past, which was not experienced as such by its referents themselves.38 History and tra

dition have become postcard images drawing on stereotypical images and 'memories'

that evoke 'neo-nostalgia'.39 Marilyn Ivy has sinU!arly developed the concept of 'neo

nostalgia' in relation to tourism ads in Japan which do not refer to a specific period but

to a free-floating past in which '[t]he idea of the neo is a literal displacement from any

original referent'.40 The ad hoc assemblage and ubiquitous repetition of in1ages, rein

forced by sinlliar genres such as calendars, postcards, or movies, underpins this feeling.

What does this say about who actually looks at these murals? Even though, as I

hope to have shown in this essay, the city authorities seem to be catering to the emer

gent new neo-liberal middle class publics, this does not necessarily suggest that the

murals appeal to them. Many middle class members I spoke to were in fact dismissive

of the 'badly painted' or 'kitschy images'; some were not even aware of the new murals

and often noticed them only after I drew their attention to them. In contrast, urban

poor city dwellers, just like the artists themselves, were largely quite happy to finally

see something other than the endless iconic faces of the state's two major political

leaders.

Like postcard images the new murals have helped reinforce the iconic, standard

ized status of history, tradition, and the beauty of the state, but is not their repetition

again creating indifference? I think we can be almost sure that after the newness of

the mural form has worn off, the depicted scenes will return from their short-lived

presence in hyperreality into the sphere of cliched, everyday manifestations that are

largely unnoticed.41

Visual Homes, Image Worlds

Notes

I have presented this work on different occasions. I would like to thank all who responded

with comments and questions that helped me shape it to its current form. I would partic

ularly like to thank Christiane Brosius, Steve Hughes, Kajri Jain, Sumath.i Ramaswamy, Pa

tricia Spyer, SV Srinivas, A Srivathsan, .Mary Steedly, and AR Venkatachalapathy for their

valuable comments, suggestions and insights. See the original version of this essay at:

http://tasveerghar.net/ cmsdesk/ essay/ 57 /

1 Note, Osamu. 2007. 'Imagining the Politics of the Senses in Public Spaces: Billboards and

the Construction of Visuality in Chennai City', So11th A sian Popular Cult11re, 5(2): 139. 2 For an elaborate account on the use of cinematic imagery in politic~! discourse, see:

Jacob, Preminda. 2009. Cell11loid Deities: The Vis11al Cult11re of Ci11e111a and Politics i11 So11th India

(New Dellu: Orient Blackswan). 3 The Hi11d11, Chenna.i edition, 29 .May 2009. 4 Public walls are compound walls of government property. 5 Brosius, Christiane. 2010. India} }diddle Class: Ne11J Fonm of Urban Leis11re, Co11s1111;ptio11 and

Prosperi()' (New Dellu: Routledge). 6 Deshpande, Satish. 1998. 'Hegemonic Spatial Strategies: The Nation-Space and Hindu

Communalism in Twentieth-Century India', P11blic Cult11re 10, 2(1): 249- 83. 7

Kusno, Abidin. 2010. The Appearances of 1Vfe11101)'." Nfne111011ic Practices of Architecl11re and Urban

For111 i11 Indonesia (London: Duke University Press). 8 Rowlands, lVIichael, and Christopher Tilley. 2006. '.Monuments and .Memorials', in

Christopher Tilley, Webb Keane, Susanne Kochler, J\tlichael Rowlands, and Patricia Spyer

(eds), Handbook of LV!aterial C11lt11re (London: Sage), pp. 500-15. 9

Eco, Umberto. 1990. Travels i11 f!Jpe/'/'eali!J1 (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich); Bau

drillard, Jean. 1994. Si11111lacra and Si11111latio11 (Michigan: University of J\tlich.igan Press).

'0

See Ivy, .Marilyn. 1988. 'Tradition and Difference in tl1e Japanese .i\fass .Media', P11blic

Cllit11re, 1(1): 21; Hancock, Mary E. 2008. The Politics of Heritagefro111 M.adms to Che1111ai

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press) . 11 The civic body iliat governs tl1e city. Its responsibilities include ilie infrastructure and planning of tl1e city. 12

A111ar Chitra Katha ('immortal illustrated story') comics have since tl1e 1980s become

very popular in India and witl1 Indian n1igrants abroad. The stories often serve an educa

tional purpose as iliey are about Indian history, religion, and mytl1ology.

Chennai Beautiful 197

198

13 Ironically, the statue depicts a fiery Kannagi who curses the city (of Madurai, in the story)

and destroys it. The statue on ·Marina beach caused various rumours, controversies and ag

itation as it was suddenly removed for a while (Pandian, ·MSS. 2005. 'Void and Memory: Story

of a Statue on Chennai Beachfront', I11te1'Asia C11lt11ral St11dies, 6: 428-31). 14 My thanks to Gandhirajan, a teacher at the Government College of Arts and Crafts,

who alerted me to this. 15 \Xlith the advent of vinyl banners and digital printing, this amount has decreased over

the years. \Xfhen the banner business was still in its heydays, an artist could earn around Rs

125 per square foot. 16 Of course, even outside India there are many examples of cities and towns in which

murals have become part of beautification projects. 17 Blog post by Arun Ram, 'j\ifissing in Action: Spidermen of Chennai', Ti111es of India.

Che1111ai Talkies, 3 August 2009. 18 Chennai is not the only Indian city searching for world-class stature. Other big cities such

as Bangalore, Mumbai, and Dellu actively try to position themselves on the world map. 19 Zukin, Sharon. 1995. The Cllit11res of Cities (Maldon, Oxford and Carlton: Wiley-Blackwell). 20 Bourdieu, Disti11ctio11. 2 1 Brosius, India's Middle Class; Fernandes, Leela. 2006. India's Nen1 Nliddle Class: De111ocratic

Politics i11 a11 Era of Eco110111ic Refom1 (Nlinneapolis: University of J\ilinnesota Press);Jaffrelot,

Christophe, and Peter van der Veer. 2008. Pattems of Middle Class Co11s11111ptio11 i11 India and

China (New Dellu: Sage). 22 Brosius, India's M.iddle Class, p. 23. 23 Fernandes, India's Ne111 Middle Class, p. ]l.'V.

24 Hancock, The Politics of Heritage fro111 NI.adras to Che1111ai; Brosius, India's Middle Class. 25 Brosius, India's Middle Class, 12. 26 Brosius, India's Middle Class. 27 Ramaswamy, Sumathi. 1998. Passions of the To11g11e: La11g11age Devotion i11 Ta111il India, 1891-

1970 (New DellU: Munshi.ram Manoharlal). 28 Ramaswamy, Passions of the To11g11e, p. 73. 29 For elaborate accounts on the use of cutouts, statues, and architecture by political parties,

see: Srivathsan, A. 2000. 'Politics, Popular Icons and Urban Space in Tanlli Nadu', in Sluvaji

K Panikkar (ed.), TiJJe11tieth-ce11t1101 Indian Smlpt11re: The Last T1JJ0 Decades (Mumbai: Marg), pp.

108-17; Pandian, 'Void and Memory'; Hancock, The Politics of Heritage fro111 l\lladras to Che11-

11ai; Jacob, Cel!ttloid Deities.

Visua l Homes, Image Worlds

30 Anderson, Benedict. 1991 . I111agi11ed Co1111111111ities: Reflections 011 the Origin and Spread of Na

tio11alis111 (London: Verso), pp. 182-85; Kusno, The Appearances of l\lle11101J'· 31 Anderson, Benedict. 1978. 'Cartoons and Monuments: The Evolution of Political Com

munication under the New Order', in Karl D Jackson and Lucian W Pye (eds), Political

PoJJJer and Co1111111111icatio11s i11 Indonesia (Ewing: University of California Press), pp. 282-321. 32 Personal conversations with several Corporation officials who are responsible for the se

lection or supervision of the new murals, i.e. the PRO, the Deputy Comnussioner, the Su

perintending Engineer (Bridges) and the Cluef Engineer of Corporation zone 10. Chennai,

2010. 33 My thanks to Sumatlu Ramaswamy for alerting me to tlus. 34 Alpers, Svetlana. 1991. 'The Museum as a Way of Seeing', in I. Karp and S. D Lavine

(eds), E xhibiting C/llt11res: The Poetics and Politics of Nfose11111 Displqj' (Washington and London:

SnLithsonian Institution Press), pp. 25-32. 35 Fuller, CJ, and Haripriya Narasimhan. 2006. 'Information Technology Professionals and

tl1e New-Rich J\iliddle Class in Chennai (Madras)', Modem Asian St11dies, 41 (1) : 121. 36 Brosius, India's Middle Class; Hancock, The Politics of He1itage fro111 Madras to Che1111ai; Sri

vastava, Sanjay. 2009. 'Urban Spaces, Disney-Divinity and Moral Middle Classes in Dellu',

Eco110111ic & Political Week!y, 44: 26-27; Tarlo, Emma. 1996. Clothing Matters: Dress and Ide11ti!J1

i11 India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). 37 Hancock, The Politics of He1itage fro111 i'vladras to Che1111ai, pp. 148-49. 38 Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. lvf.odemi!Ji at La1ge: C11lt11ral Di111e11sio11s of Globalization (Nlinneapo

lis: University of i\ifinnesota Press); Ivy, 'Tradition and Difference in tl1e Japanese Mass

Media'. 39 Ivy, 'Tradition and Difference in the Japanese Mass Media'. 40 Ibid., 28. 41 Several months later, I came across the remains of posters and writings on a few murals;

the others all look conspicuously clean.

Chen nai Beauti ful 199