Chapter Four: Re-Reading Liverpool

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of Chapter Four: Re-Reading Liverpool

96

Chapter IV

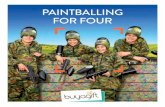

Picture 10: Albert Dock circa 1997, with the Museum of Liverpool Life and the Liverpool ’Trinity’ beyond (The white ‘tower’ to the right is the 1930s

ventilation shaft for the Mersey Tunnel).

97

Chapter Four:

Re-Reading Liverpool

During his philosophical consideration of the consumption of places, Consuming Places (1995)

Urry is concerned that “many localities in contemporary societies are being transformed by

diverse forms of economic restructuring.” He asks, “How though are we to analyse these

processes? What is the relationship between changes in such causally powerful entities and

sets of empirical events in particular places?” (Urry, 1995, 71). I would pose the possibility that

such “restructured” place, supplemented by a specific notion of time, may be discussed as an

emotional entity and a psychological Imaginary as well as a social and economic reality of urban

regeneration. Urry proposes that “some particular national and international processes” […]

“take a particular form in a certain locality” and that “As all social processes are contextualised

in particular places, the identification of the form taken by such a process in a given place is a

useful research project.” (Urry, 1995, 71). Through my research project around saga fictions, I

hope to illustrate that they address questions raised by Urry, as they may or may not apply in

post-industrial, post-transformational Liverpool. I believe that the topographical associations

identifiable in all saga fictions (table 1.2) exemplify Urry’s thesis for cultural relationship with

place, that “A general feature of the culture of a given region or nation may be that strong

distinctions may be drawn between the local and non-local.” (Urry, 1995, 73. See also Urry,

1995, 152-162; 187-192; 214-220). Fredric Jameson’s ideas become appropriate here.

Jameson asserts that contemporary populations have become lost within a topography

rendered unrecognisable not only by swift change in function and the perceived identity of a

place, but by a concurrent temporal disruption or dislocation in those populations’ experience of

life. Jameson quotes Lynch’s proposition that “the alienated city is above all a space in which

people are unable to map (in their minds) either their own positions or the urban totality in which

they find themselves:” (Jameson, 1991, 37). This combines comfortably with Urry’s suggestion

that landscapes “are narratively visible in time” and his discussion of Lynch’s question, ‘what

time is this place?’ ([Lynch, 1973] Urry, 1995, 189-190).

In (1960) Image of the City, Lynch notes that among his Los Angeles questionnaire

respondents, a “[…] frequent theme was that of relative age. Perhaps because so much of the

environment is new and changing, there was evidence of widespread, almost pathological

98

attachment to anything that had survived the upheaval.” (Lynch, 1960, 42). In the case of

Liverpool, the confusion and insecurity as to the time represented by, or usurped by, change of

place or space becomes compounded by the complications of nationalising and

internationalising interest in that place and its spaces.

This chapter seeks to contextualise Liverpool as a narrative space that pertains to the location

and development of a large and significant group of saga fictions set there, and examines

Liverpool as a setting that provides one particular version of what is demonstrably a national

trend in popular fiction. Therefore, of especial interest about Liverpool as a saga setting is not

its writing tradition, but what it had in common with other British regional saga settings in the

1980s and 1990s. Liverpool as a port exemplifies the collapse of British docklands and the way

of life that had evolved in them in several major cities where sagas are set, notably Bristol,

Glasgow, London, Portsmouth, Swansea, Tyneside, and the prolific canal quays of Manchester

and Bradford. In those decades, economic recession, post-industrial restructuring and a

prevailing mood of nostalgia about the defunct industrial age, coupled with anxiety surrounding

the drastic changes in both appearance and social function of city spaces, prevailed.

Recognition of the imminent erasure of evidence providing connections to a past that many

people still remembered led to a number of strategies for preserving those memories, with

particular emphasis on gender and class. The Merseyside Oral History Project was only one of

a number of such Liverpool initiatives that established a useful archive and produced

publications helpful to the researcher. Saga authors also developed a range of initiatives to

similar effect.

Recognising the remarkable extent to which personal and cultural memory become

incorporated into saga fictions raises a range of issues that I will address in this chapter. The

foremost of these is how to compare or connect Liverpool’s new persona as an international

tourist attraction with the city characterised by its long-term residents through these mass-

market fictions. My discussion draws on Jameson’s argument that “there no longer does seem

to be any organic relationship between the […] history we learn from schoolbooks and the lived

experience of the current multinational, high-rise, […] city […] and of our own everyday life.”

(Jameson, 1991, 15) and conflates from his identification of spatial issues as a fundamental

organising concern […] to be defined through an aesthetic of cognitive mapping (Jameson,

1991, 36). Liverpool’s wealth enabled the generation of architectural experiments that pioneered

99

‘high-rise’ building techniques, and it was apparently from Liverpool that ‘high-rise’ technologies

passed to Chicago (Browning, 1990, 31).

Liverpool’s recent rebirth as a cultural rather than commercial centre, the location of

universities and museums (sites of learning), has changed the nature and meaning of the city’s

spaces for its long-term communities. In the 1970s Liverpool de-industrialised and, in the 1980s,

became a tourist city (Urry, 1995, 154-157), a set of curiosities and spectacles for the outsider

to come in and marvel at (Urry, 1990; Urry, 1995, 189). The Albert Dock in its current pristine

tourist-friendly condition, a sanitised ‘heritage’ site, Liverpool’s legacy from ‘Heseltine’s Britain’

of the 1980s1, both symbolises and problematises today’s cognitive map of Liverpool

2. Gone is

the city’s former identity as a commercially significant Imperial port and transformative

international migrant and tourist translocation stage, and gone are the work practices and ethos

that went with that. In addition, Liverpool underwent many of the same changes to the nature

and use of its town centre spaces as many other town and city centres that “were deeply

affected by the recession of the late 1970s and early 1980s” (Worpole, 1992/1993, 93) and

“were perceived locally and nationally as having lost their traditional functions […] as the very

focus of the urban ‘public realm’”. Liverpool had been the subject of the pilot study that

established methodology for Worpole et al in the wider study (Worpole, 1992/1993, 1). I believe

that both Heseltine’s development and Worpole’s ideal urban environment are irrelevant to saga

readers, that there is a search for restitution of certain past meanings that cannot be addressed

by the ‘new’ Albert Dock or the regenerated town centre, taking place through the pages of

regional, in this case Liverpool, saga fictions.

Albert Dock appears unique, but is part of a national trend. The Merseyside County

Council (1980) Docks Prospectus development plan for the Liverpool South Waterfront, (around

Albert Dock) bears close resemblance to similar maritime heritage projects elsewhere at that

time, such as Gateshead on Tyneside. The creation of a simulated ‘heritage’ waterfront, with

simulacral stereotypical sailors and artefacts, a maritime version of Wigan Pier, was envisaged,

with shopping malls on derelict dockland sites further upriver. It is at this stage, due largely to

government intervention, that the Liverpool plan was substantially changed, placing greater

emphasis on establishment of museums and galleries at the site, shifting from local to national

and international heritage, attracting international interest. Along with refurbishment and

restructuring of Liverpool’s own museums and galleries, this incurred long-term effects on how

Liverpool’s own history would be presented both to tourists from outside the city and to the city’s

100

inhabitants. Mellor (1991) and Urry (1995) provide a useful summary of how the subsequent

Liverpool waterfront attractions developed. In 1981, Michael Heseltine set up the Merseyside

Development Corporation, which undertook the work of restoring the Grade 1 listed buildings

then in disrepair at the Albert Dock. Stage 1 was completed by 1984 when the Tall Ships Race

and the Liverpool International Garden Festival, which attracted 3.3million visitors, were held as

part of a specific project to regenerate a Liverpool where the number of manufacturing workers

had fallen from 240,000 in 1971 to 150,000 in 1981. On May 28th 1988, Tate Gallery North

opened in one of the Albert Dock buildings; by 26 April 1990 it had received 1,358, 435 visitors.

The Merseyside Maritime Museum had over 409,000 paid admissions in 1988 alone. That same

year, the Albert Dock became the third most visited attraction in the U.K. after Blackpool

Pleasure Beach and the British Museum (Mellor, 1991, 101-102; Urry, 1995, 115). In 1995, a

probable annual figure of 5 million visitors to this waterfront complex was being projected (Urry,

1995, 115).

At the same time Helen Forrester’s reputation for telling the story of the Liverpool poor

in previous decades was growing, and new authors were preparing their versions of this de-

industrialised, post-colonial city. In spite of the changes taking place during these decades,

including riots and rising poverty, Liverpool politicians had difficulty acknowledging that the city’s

function as a primary gateway to the Empire had ceased. Bishop of Liverpool, David Shepherd,

attempted to articulate the process of change that the city was undergoing:

Liverpool is sometimes dismissed as a maverick council and city […] When we look back in 20 years’ time, I believe that we shall see that it was the first, or one of the first, of many post-industrial cities. ([Halsall, 1987] Urry, 1995, 112).

Urry is resistant to the thesis of a post-industrial city or society, claiming that it “reduces social

and political life to changes in the structure of the economy and fails to address complex

transformations in the ways in which people experience such changes” [author’s italics] (Urry,

1995, 113). My thesis is that this is precisely the area where Liverpool saga novels become a

useful discussion of those social and political changes, and that the reading of them may be a

significant expression of a failure to address ways in which certain people experience such

changes. Sagas foreground ways in which older women’s experience of the city centre has

changed, and this may be because older women’s cultural and communal needs are not

catered to within the city’s new developments.

101

Merseyside Development Corporation’s 1990 plan to revitalise the city centre begins

optimistically, but takes scant interest in the type of city centre Worpole’s Utopian-nostalgic

thesis clings to (Worpole, internet, 1992)3:

4.1 This Strategy has a simple aim: to extend the benefits of waterfront regeneration into the heart of the City Centre. A strong centre to the conurbation is essential to its wider generation. 4.2 […] MDC will work very closely with the City Council […] The Liverpool Waterfront area has the capacity to accommodate an expansion of the shopping core close to the prime pitch, consolidation and expansion of the office quarter with prestige office developments on the waterfront […] (Merseyside Development Corporation, 1990, 7)

an aspiration not denied by the remarkably similar 1990 Liverpool City Council plan, which

simply places its emphasis more on new housing development in reclaimed docklands:

4.1 The Area Strategy seeks to consolidate the major changes which have taken place in South Liverpool during the 1980’s with a view to completing most developments by the mid-1990’s. An exciting residential and commercial environment is being established […] 4.2 The Area Strategy further identifies the importance of this area as an access to the City Centre […] (Liverpool City Council, 1990, 7).

In the event, neither of the plans has come completely to fruition, but the pedestrianised

shopping and resulting traffic-free spaces have evolved to allow conception of an entirely

different café-bar ethos for Liverpool (Carter, 2002), offering leisure facilities for residents as

well as the city’s new population of tourist hotel guests4.

Recent focus on the Liverpool waterfront seeks to develop and ‘modernise’ the space

that lies between the Albert Dock tourist attraction and the ‘three graces’ or ‘trinity’, an iconic trio

of buildings that have become symbolic of both Liverpool aspiration and of Liverpool itself.

During the Twentieth Century this space and other nearby spaces have changed function

several times. North of the ‘three graces’ was the landing stage for prestigious trans-Atlantic

liners from circa 1830 to 1930 and the railway terminal for boat trains, with Welsh, Irish and

cross-river ferry terminals nearby (Browning, 1990, 25-26; Andrews, 1991c, 25; Wilkinson,

1993). These national and international connections were well supported by a cluster of local

transport facilities, including bus and tram terminals and the docklands artery, the overhead

railway, a trip on which was from the 1930s promoted as a tourist experience (Coles, 1993,

Plate 12; 176). Demolition in the 1950s transformed these spaces to mundane car parks and a

revamped Mersey Ferry terminal that form the focus for the controversial 2002 architectural

competition (which currently promulgates a combined futuristic shopping mall and office

complex). The road alongside this area is still named The Goree after the source of Liverpool’s

102

principal founding wealth, the island off East Africa where freshly captured slaves were held

until collection by ship. To have grown to be among the richest cities in the British Empire by

1900, after less than 300 years as a major port, Liverpool had to be underpinned by strong

economic activity, trade. The ‘Africa’ trade that provided Liverpool’s copper-bottomed

investment potential5 also enabled the construction of both shipping and associated

manufacturing industry. Large service industries such as insurance also developed in Liverpool,

incurring the need to build increasingly large and significant buildings.

The iconic buildings of the Liverpool waterfront seem classical, historic and demonstrative of

international influence, with a strong indication of India and Empire in some features, such as

the twin towers of the Royal Liver Building. In fact they are both fairly recent (the ‘long’

Edwardian period), and symbolise the renewed hope of Liverpool at the end of the nineteenth

century, before the cycle of boom and bust economics that characterise the decline of Empire

during the first half of the Twentieth century.

Royal Liver Building Cunard Building Mersey Docks and Harbour

Board Building.

Liverpool reached its zenith at the turn of the 20th century, becoming one of the

richest cities in the world. […] This wealth is vividly expressed in the trio of buildings erected […] at the Pier Head: the Royal Liver Building, the Cunard Building and the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board Building. […] The Pier Head group of buildings typifies the money that was spent by those who felt confident that Liverpool was a genuine rival to London. This is also reflected in street names such as Covent Garden, the Temple, Islington and The Strand which echo the streets of the capital. (Morris and Ashton, 1997, 15).

The rightmost building of the trio, the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board Company Building, was

completed in 1907, built in grandiose renaissance style to (successfully) attract investors for

dock development and administer the extensive Liverpool dock area. The centrally located

Picture 11: The Liverpool waterfront ‘Trinity’ or ‘Three Graces’

103

Cunard Building, styled after an Italian palazzo, was completed in the First World War (1916).

The leftmost building, the Royal Liver Building, is a bold architectural experiment, with its multi-

story pre-cast concrete construction and heavy clocks ensconced in high towers, completed

between 1908 and 1911. The vista presented by these three buildings has continually

symbolised Liverpool aspiration since.

By the 1950s industrial dirt and grime had reduced the appearance of these buildings to

a more workaday condition, yet director Michael Anderson foregrounds their iconography in his

Liverpool-based social realist/’social problem’ film Waterfront (1950), using a studio backdrop of

the Liver building, a liner looming alongside, implying its wider significance to a cinema

audience as a symbol for Liverpool. The Liver Building had particular meaning for anyone who

returned to Liverpool by sea, signifying ‘home’ and now serves as the principal sign for the City,

its statues incorporating the city’s crest – the Liver Bird. An immense amount of local Liverpool

pride remains invested in this sign. The railway, tram, ferry and liner traffic and the Mersey

Tunnel traffic that converged on this spot meant that mass translocation of both local and

transitory populations occurred daily, if not hourly, imbuing a sense of the Liver building being

the heart of the city. From the mid-1950s a series of traumatic transformations to Liverpool

traditional industry, and therefore the Liverpool waterfront, took place. Edwina Currie (writing

her own attempt at a Liverpool saga) cites: “[…] seventy four shipping companies registered in

Liverpool this year [1963]. Within twenty years there’ll be hardly a dozen.” (Currie, 1998, 43).

The overhead railway, the ‘docker’s umbrella’, was demolished; the liners were replaced by

aeroplanes (to Manchester); the tramway was replaced by buses; dock work practices were

transformed by new designs in machinery and shipping; tenement populations were relocated;

markets and ‘slum’ communities along the nearby artery, Scotland Road, were replaced by a

multi-lane highway. But the Liver building remains, a significant Liverpool waterfront icon, and

has become the focus of today’s tourist map of Liverpool. Yet this map does little to address the

difficulties of long term residents who, navigating by an archaic map, attempt to devise cognitive

maps that may at least trace an organic relation, a way back ‘home’ through the complexities of

recent change.

These buildings, rather than the Albert Dock complex, increasingly dominate cover

design for Liverpool and Merseyside sagas during the 1990s, as Liverpool’s post-industrial

renaissance as a tourist city gathers pace, but closer analysis reveals continued gradual

changes in cover iconography that concur with thematic shifts in the narratives. For instance,

104

the cover art of Forrester’s autobiographies (1974-1985) features locally significant Liverpool

buildings such as the Town Hall rather than the waterfront, so that the iconography impacts as

universal, of poverty, girlhood, and the city. The ‘map’ of Liverpool that now interests the

readers of Liverpool sagas is located elsewhere, however, away from both waterfront and city

centre. Those readers live in or, after relocation, warmly remember having lived in, the many

miles of Victorian terraced streets that remain to the north and east of the city, especially in

Everton and Anfield. It is these districts and their red brick streets that constitute the locales for

fast-selling and steady-selling British regional saga fiction. Lynch asserts that

Environmental images are the result of a two-way process between the observer and his environment. The environment suggests distinctions and relations, and the observer – with great adaptability and in the light of his own purposes – selects, organises, and endows with meaning what he sees. (Lynch, 1960, 7).

The saga editors, and the cover artists they commission, understand this in a social as well as

environmental sense, as true for their readership. The generic nickname for working-class

regional sagas, 'clogs and shawls' (Alex Hamilton, 1994), allows a useful social visuality,

suggesting a particular iconicity for the regional working-class saga. By the late nineteen

eighties, regional saga covers had developed a distinct semiology (chapter two above) often

conveying that same information and a “visual quality of the […] city which is held by its citizens”

(Lynch, 1960, 2).

Picture 12: Cover: All the Dear Faces, Howard (1992)

Picture 13: Cover: There Is A Season, Murphy (1991)

105

Cover iconography on Liverpool saga fictions evolves as public perceptions of Liverpool may be

envisaged to have evolved during the 1980s ‘renaissance’. So we find the maritime heritage

illustrated at first, both an earlier and more picturesque version and the grubbier one which

Michael Anderson (1950) captured in the opening montage of the workaday Liverpool

waterfront; then, on saga covers, came the sanitised ‘tourist’ iconography. It is well into the

1990s before covers demonstrate the personal cognition that is at the heart of British regional

sagas everywhere, and this (the depiction of the housewife) begins with covers depicting World

War Two.

By 1986, Audrey Howard had joined Helen Forrester with Liverpool based saga-like

fictions published both with Century / Arrow and with Hodder / Coronet. There is a notable

ambivalence by her cover artists between the nostalgia of the working mid-century waterfront, of

‘clogs and shawls’ and the days of sail, Liverpool and Albert Dock tourist status having been

publicised internationally by twice hosting the Tall Ships Race in that decade. In 1989, London

publishers Headline and Corgi made their first foray into the Liverpool saga market with

Elizabeth Murphy (The Land Is Bright) and Lyn Andrews (The White Empress) respectively; the

cover artists for each foregrounded a young woman in period dress against a distant maritime

background; each sold in excess of 90,000 paperbacks.

Picture 14: Cover: To Give and to Take, Murphy (1990) Picture 15: Cover: Ellan Vannin, Andrews (1991)

106

By 1993 these two authors had published a total of ten similar books in which the Liverpool

waterfront ‘tourist’ iconography – the Liver building, the Pierhead ‘trinity’, if present, was

distant/remote. They were joined by Anne Baker (Headline, 1991), Joan Jonker (Print

Origination/Headline, 1991), June Francis, (Piatkus/Bantam, 1992), Sheila Walsh,

(Century/Arrow, 1993), Katie Flynn (Heinemann/Mandarin, 1993) and Maureen Lee (Orion,

1994), making the market highly competitive and cover symbolism a significant factor impacting

on sales figures. The semiology of Liverpool saga covers of the early 1990s appeals to similar

local nostalgia for the lost mid-century Liverpool to The Helen Forrester Walk (Rickard, 1987)

(see below), but internationally understood iconography for Liverpool features increasingly. In

1993 ten authors published twelve new Liverpool sagas, the most ever in one year. From this

point, such strong competition for the same readership precipitated a number of changes in

approach to saga production. Cover artists begin to be named on individual sagas, revealing the

use of local freelance artists. For instance Gwynneth Jones, a local F.E. teacher, has provided

illustrations for a number of sagas by Katie Flynn, June Francis, and Joan Jonker. Other artists

include Gary Blythe, Nigel Chamberlain, Chris Collingwood, Gordon Crabb, Gary Keane, Nick

Price, George Sharpe, and Len Thurston. The fact that the artists are usually named on the

books from 1993 onward, and that the authors of highest status, such as Katie Flynn, are

shown preliminary sketches for approval (as observed at meetings of the Romantic Novelist’s

Association North West Chapter meetings, from 1998 to the present, where artists’ preliminary

sketches may be circulated), implies continued publisher recognition of relevance to the

potential customer with strong local/regional affiliations.

Picture 16: Cover: The Girl From Penny Lane, Flynn (1993) Picture 17: Cover: All On A Summer’s Day, Gardiner (1991)

107

The work of the port is no longer the focus and Liverpool as a fantasy setting becomes

foregrounded in (a fact that artists and authors alike bemoan) publishers’ insistence on

unrealistic pristine white buildings against a fabulous blue sky (an interesting intersection of

recognisable tourist iconography with signification of the Utopian ideal typical of saga and other

popular fictional fantasies. ([Gramsci] Fowler, 1991, 31-33). Generally, trams, cranes and ships,

the “schoolbook” signifiers of Liverpool, are no longer much in evidence. (Jameson, 1991, 15).

The fictions themselves then begin to diverge between those that sell through the icons and

historical references of Liverpool locale and those that sell by a more subtle sense of theme. At

this point the saga market nationwide was diverted into a plethora of World War Two scenarios

to cash in on a national nostalgia. But by the mid-1990s even those Liverpool sagas not

catering to the World War Two anniversary market began to deviate from the earlier elements of

specific Liverpool cover iconography.

Picture 18: Cover: Liverpool Lamplight, Lyn Andrews (1996)

Nationally, the terraced street had been the working-class regional saga’s iconography from the

late 1980s. Indeed, new publishing house Orion had concentrated on soap opera-like back-

street community sagas set in a variety of English cities, with covers reflecting that rather than

locale. But it was the mid-1990s when the publishers finally realised that the icon for the 1990s

British regional working-class saga is actually the working-class woman, albeit often encoded

as her younger self in training, for her ultimate role as ‘the housewife’.

Picture 19: Cover: Until Tomorrow, Walsh (1993)

The cover iconography, then, has finally caught up with the typical reader6, who is a woman

over fifty years old, negotiating her way through a cultural re-mapping of her life and her

mother’s life that concurs with scores of similar fictions set in other regions and other cities of

108

industrial/colonial Britain. The pace of social change for women has, since the 1970s, been so

rapid and so radical that the profoundly organic, and socially determined, role of housewife has

virtually vanished. Ignored by Marxism, her way of life castigated by Second Wave Feminism;

inscribed into history only in her middle-class persona, without any sense, historical or

otherwise, of her importance to British twentieth century life, or her ingenuity in negotiating the

final difficult decades of colonial decline7. So these fictions map a wider reality, and their

semiology and central topography are common to a wider than local readership; the Liverpool

saga therefore interpellates both a large body of local readers, and a wider readership in other

post-industrial locations with whom its central concerns particularly resonate.

My adoption of Jameson’s argument that “there no longer does seem to be any organic

relationship between the […] history we learn from schoolbooks and the lived experience of the

current multinational, high-rise, […] city […] and of our own everyday life.” (Jameson, 1991, 15)

as a rubric for recent Liverpool publications, is supported by a range of film and literary

evidence. In the late 1990s, the British Film Institute rediscovered and re-released Michael

Anderson’s Waterfront (1950), which offers a realist view of both the fictional and the real space

of Liverpool based on John Brophy’s contemporary novel of the same title. John Brophy (1899-

1965) was a Liverpool resident with strong connections to the Labour Party. In 1950, Brophy’s

novel was reprinted in paperback by Pan. It was reprinted once more, by Corgi (1958)8, then fell

into oblivion, along with his other social realist novels, which in 2002 are unobtainable, even in

Liverpool. The Waterfront prologue is set in 1919, a year of significant political unrest in

Liverpool, but the main narrative is contemporary to publication in 19349. The place-establishing

montage opening Michael Anderson’s black-and-white movie filmed on location on the Liverpool

waterfront in late 1949 or early 1950, offers shots of docks, cargo ships, liners, overhead

railway, tenements, pervaded by the foggy atmosphere characteristic of British cities at the time.

Historically this was just before the city’s geographical and topographical character changed far

more radically in national and spatial terms even than during World War Two. It is striking the

extent to which Anderson’s opening shots, panning across the power of the working port, giving

a glimpse of the twin economies of shifting goods and shifting people, concur with the

“schoolbook” account of Liverpool and of Empire (accessed via the docklands’ ‘mighty

gateway’) that was being offered at about the time that this film was released. What would have

been a geography lesson then, becomes a history lesson now – an interesting intersection of

109

questions of space and time – simply because, through the collapse of Empire in the 1960s, so

much has changed.

In 1933, expatriate, Pat O’Mara, writing his Autobiography of a Liverpool Slummy for an

American readership, strikes a similar “schoolbook” tone:

Liverpool, England, where I was born and raised, is [...] the greatest seaport in the world. There are seven miles of docks, stretching from the Herculaneum, at the most southerly tip, to the Hornby, at the most northerly. Skirting these docks and taking in practically all of the slums is the overhead railway, and it is from this vantage point, […] that you may glimpse the more significant phases of the city […] (O’Mara, 1933/1994, 1)

Comparing Anderson’s account with O’Mara’s (1933), the principal mise-en-scéne of the film

closely reconstructs tenement living conditions in Liverpool, known as ‘barracks’ or, worse, if

Corporation owned, ‘Courts’, where the poor and the shiftless gravitated10

. Examples of these

also existed very close to Albert Dock. I propose that parts of this early ‘social problem film’ can

no more be automatically characterised ‘cliché’ rather than ‘history’ than saga fiction can.

Indeed, in offering the opening of Anderson’s filmic fiction as a factual account, I foreground the

complexity of fictional accounts of place, as well as their usefulness to the researcher.

The prologue to the filmic realist-moralist drama becomes a discussion of the

devastations wrought on three women by the fecklessness, selfishness or helplessness of their

menfolk, unlike working-class regional saga fictions, which demonstrate how women’s

knowledge and agency brought the family through the vagaries of late colonial capitalism.

Anderson’s prologue involves a strong argument between schoolgirl Nora and her seaman

father as he departs for a long haul, leaving his pregnant wife and two daughters with no

money. Nora rightly perceives that her father has failed to arrange an allocation from his income

for his family’s keep in his absence. The “allotment” was a portion of the seaman’s wages that

could be kept back by the shipping line employing him, for his wife to collect at intervals decided

by them – this may have been every two or three weeks, for example. Examples of allotment

orders may be seen at the Museum of Liverpool Life at Albert Dock, but no explanation is

offered of how this translated into everyday reality for Liverpool women. Liverpool saga authors,

on the other hand, are well versed in such details. The Forrester extract below demonstrates

how convincingly these fictions can reflect reality (and note how the sense of place seems

inexorably woven in to the action):

[…] they had walked, the appointment having been made for the day before Daisy drew her allotment from her husband’s shipping company, a day on which she was always penniless. Michael’s allotment was eighteen shillings a week and this,

110

added to her mother’s old age pension of ten shillings, had made the two women a shilling or two better off than if they had been dependent upon the Public Assistance Committee. Still, it was not very much.

Now as she sat demurely in the tram, hands folded neatly in her lap, as it trundled through the streets, bell pinging impatiently to make carters move their wagons off the lines, it dawned on her that her mother’s pension had ceased with her death; yet she would be faced with the same need to pay the rent, the same need for a coal fire and oil for the lamp; but she would have only eighteen shillings with which to do it all. She was aghast. Under her warm shawl her body felt cold, and she trembled. (Forrester, 1979, 47).

Across the road from the Albert Dock and its nearby much-photographed companion waterfront

buildings on the Pier Head, were the only slightly less imposing offices of the main shipping

lines (Browning, 25-26). Saga fictions sometimes describe how ignominious petty clerks could

make the experience of queuing and signing at these offices for the allotment11

. In the Liverpool

economy between the wars married women were not allowed to work in better-paid jobs in

factories (Jones, 1996; Ayers and Lambertz, 1984; Williamson, 2000b). Many seamen’s wives,

however, were quietly equated with widows and granted low-paid, low-status work as cleaners,

often by the same shipping companies, either in their offices or their ships-in-port. Another fact

that sagas incorporate into the fiction:

A young widow with six children to bring up by herself and God knows that hadn’t been easy. […] after that terrible day when they’d come to tell her that he’d fallen from a hatch cover into an empty hold and had broken his neck, she’d known she would have to work even harder. […] She’d had four cleaning jobs. All in India Buildings. Two early in the morning, the other two in the evenings when the office staff had gone home. In between she had washed, shopped and cooked, then once a week she had joined the army of cleaners who converged on the Cunard liners and worked like furies so the ship would be ready to sail again the following day. Twelve or fourteen hours at a stretch they worked and she often wondered how she’d found the energy to crawl home, but the money was good and she desperately needed it. (Andrews, 1992, 16)

12.

In twentieth century Britain everywhere, inner city demolition led to the post-war relocation of

entrenched populations, the dispersal of established communities and the development of new

‘problem’ housing developments and estates. The destruction caused by bombing is dealt with

comprehensively within the remit of British regional sagas generally, and by re-locating lost

spaces into the Imaginary, constitutes an important aspect of the concept of cognitive

remapping for this genre. As Jameson points out, Lynch found that

Disalienation in the traditional city […] involves the practical reconquest of a sense of place and the construction or reconstruction of an articulated ensemble which can be retained in memory and which the individual subject can map and remap along the moments of mobile, alternative trajectories. (Jameson, 1991, 36)

111

Post-war mass re-housing with traumatic relocation came very late to bankrupt Liverpool, and

the personal implications of that in the early 1980s became the focus of a whole other range of

fictions, plays and soap operas (for instance, Russell, 1983; Redmond, 1984) attempting to

assist the emotional negotiation of the new map of Liverpool.

Autobiography offers an emotional account of place that in the case of Liverpool also

translates into tourist activity. Helen Forrester’s four-volume life story, set in the city from 1930

to 1946, inspired the 1980s best-selling booklet, The Helen Forrester Walk (Rickard, 1987).

The Helen Forrester Walk (Rickard, 1987) maps the area just beyond the city centre directly

correlated to the contents of this saga-like story. Its cover iconography of ships, trains and trams

signifies ‘Liverpool Past’ and the ‘schoolbook’ version of Liverpool, its content is closely related

to a remembered rather than actual topography, informed by Rickard’s notes cross-referencing

to Forrester’s autobiographies. It is sold almost exclusively at outlets on Albert Dock, especially

the Tourist Information Office and The Museum of Liverpool Life.

Picture 20: Cover: The Helen Forrester Walk, Rickard (1987)

What readers/users will find, if they have read the fictions as well as the autobiographies,

contrasts sharply with their mental ‘map’ of Liverpool. They will find themselves in the smart

conservation area and strong university presence around Rodney Street, that two post-war

cathedrals (Catholic, 1967; Anglican, 1978), both tourist destinations in their own right, now

dominate either end of Hope Street, and that Forrester’s past (and first) Liverpool home beyond

had disappeared long before the 1980s riots engulfed its neighbourhood (Henri, 1991 in Coles,

1993). Yet these locations become blended into ensuing saga fictions.

Liverpool saga fiction authors frequently latch on to the Forrester ethos, or its tourist

connections, mentioning Rodney Street and Hope Street in the early pages (those usually

browsed by prospective readers), and all Liverpool sagas are likely to make mention of the Liver

Building and/or the Pier Head. The Imaginary Liverpool indicated in much of the earliest saga

112

fiction negotiated heavily around the liminal area of landing stages, alongside the Pier Head.

Indeed, the theme of escape by traversing those spaces onto ships (or escaping their bounds)

dominated early attempts at the genre by certain authors, taking their cue both from a common

Liverpool fantasy and from Forrester’s autobiographies, where escape is the key to betterment.

Forrester’s first autobiography foregrounds this aspiration to escape in its title Twopence To

Cross the Mersey, (1974) where the cost of a ferry fare is perceived as the impossible price of

escape to a remembered childhood idyll on the Wirral Peninsula. Judy Gardiner’s heroines do

not ring true within the later saga tradition because they either come in to Liverpool having

grown up elsewhere and do not establish themselves in working-class communities (Gardiner,

1984), or locate a substantial part of the heroine’s action in war-torn Europe (Gardiner, 1991).

Lyn Andrews posits several early heroines as travelling the world or settling in various other

parts of Britain, excitement, glamour, wealth and adventure appearing to lie beyond Liverpool

and its slums, (Andrews, 1989, 1990, 1991a, 1992), while Forrester’s later bestselling sagas

feature central characters returning to Liverpool from abroad (Forrester, 1991, 1993) and thus

experiencing the city from an outsider’s point of view, combined with extensive flashbacks and

reminiscences. Anne Baker’s heroines increasingly leave Liverpool, usually for Africa, but their

engagement with the effect of Empire on Liverpool-connected individuals locates them firmly

within the saga palimpsest, (Table 4) on occasion offering insight into how the inner palimpsest

was escaped by some women (e.g. Baker, 1991, 1996). Sheila Walsh, June Francis and Katie

Flynn (and also Lyn Andrews) make use of the layers of the palimpsest just beyond the city,

Liverpool’s nearest pleasuregrounds, to the South, North Wales and to the North, Southport, or

its nearest islands, the Isle of Man and/or Ireland, which also may constitute, for an interlude,

‘home’, or refuge (Andrews, 1989; Flynn, 1993; Francis, 1990; Walsh, 1993).

By the mid-1990s, however, the majority of Liverpool sagas are located where Murphy

and Jonker, and then Lee, always locate them, in homes within the working-class districts of

Liverpool. Only when Lyn Andrews settles for this location (Andrews, 1998b) does she enter

Alex Hamilton’s annual table of the UK top one hundred fastsellers (Appendix 1).

These fictions usually rapidly locate the reader inside the neighbourhood and the home:

The front doorways of the tiny houses were flush with the street, and at most of them women in flowered pinafores stood by their open doors. Cathy Redmond stepped from the door of number twenty, next to which stood a baby carriage, and looked anxiously down the narrow street. […] (Murphy, 1991, 1). They went through to the back kitchen and Cathy lifted a basket of dry washing from the top of the mangle. […] “You must be the cleverest lad in Everton - Liverpool even.” (Murphy, 1991, 2).

113

They usually also foreground their ‘Liverpoolness’ in the first twenty pages by reference to, even

incorporation of, actual main streets whose character was in actuality substantially demolished

decades previously, most commonly Scotland Road and Great Homer Street (e.g. Howard,

1992; Flynn, 1993; Francis, 1996; Andrews, 1997a; Hamilton, 1997).

For Jameson,

the great Althusserian (and Lacanian) redefinition of ideology as ‘the representation of the subject’s Imaginary relationship to his or her Real conditions of existence’ […] is exactly what the cognitive map is called upon to do in the narrower framework of everyday life in the physical city: […] The Althusserian concept now allows us to rethink […] specialized geographical and cartographic issues in terms of social space--in terms, for example, of social class and national or international context, in terms of the ways in which we all necessarily also cognitively map our individual social relationship to local, national, and international class realities. (Jameson, 1991, 37).

I believe that is what saga fiction is doing, explicating a cognitive map through which readers

may pleasurably navigate not only bygone topographies, but may renegotiate both past and

present social realities through fictional perspectives. It also seems likely that much tourism

assists the same project. Galsworthy’s tourists visit Victorian London and the Arts and Crafts

mansion; there is the colonial mansion of Gone With The Wind, Krantz’s imaginary artists’

France, Binchey’s cosy Ireland, and the English village and its church of Joanna Trollope and

Mary Wesley. ‘Heritage’ tourism in defunct (usually male) work places concurs with the

Imaginary of The Catherine Cookson Trail and The Helen Forrester Walk. Place and capitalism

via colonialism are central to the development of generic tropes specific to saga fiction; the sub-

text is invariably the effects, both material and psychic, of loss of Empire. And Liverpool’s Albert

Dock marks the end of Empire.

It is a generic feature of saga fictions that they recognise, even record, the sense of loss

of identity by the saga reader invoked by their (usually historic) dis-location from ‘home’ (Paizis,

2001). In some historical sagas either war or emigration provides this dislocation, in others it is

economic change that relocates the home and its land from the centre to the edges of the

family’s economic project. Migration sagas in English mainly deal with the difficulties faced by

rural Jewish or Irish immigrants coming in to industrial cities, or of British migrants converting

the wilderness into a worthy factor in colonial economics. Either is fuelled both by a sense of

homesickness and a determination to make a home.

All sagas have the same discussion of place and nation as a subtext to be called into

play as a narrative device when it suits the author. An analysis of generic tropes, such as the

114

structural narratology, therefore gives rise to a sense of generic topoi, which can then be further

mapped onto the topographical palimpsest (Table 2) where each type of saga may emphasise

different spatial aspects of the palimpsest. The saga attaches a particular sense of, or aspect of,

identity or personal cognition to a particular aspect of space within the palimpsest. In the case of

the regional British saga, the palimpsest appears tight and parochial and engages in the wider

topography only when a protagonist aspires to escape or to attain betterment (Table 4). The

Liver Building and its liminal landing-stages / arrivals and departures are located within the

Liverpool saga palimpsest, but in the outer area, at the edge, where only the most ambitious

saga heroines penetrate its patriarchal portals, rather than at the heart of the Imaginary city.

Generally, in actuality, either the place or the sense of identity attached to it has been displaced

or erased during sudden rapid change. Thus the fiction generates a convincing sense of the

identity of a specific place that concurs with how readers may remember it, or may wish to

experience it again; and the success of British regional working-class saga fiction has

developed through the sense of recognition, or perhaps, what Worpole calls “respect”, for their

emotional involvement with that place.

Local identity remains one of the strongest emotional ties left in secular life, one of the most powerful 'imaginary communities' in which we live. It deserves serious consideration and respect. (Worpole, internet, 1992)

The driving emotion of all regional working-class sagas is ‘home-sickness’. At the centre of the

saga’s topographical palimpsest, place and identity seem interdependent. In the case of

Liverpool women readers relocated to new towns at Kirby and Skelmersdale (persistently

among the poorest towns in Britain), they comment to authors that they find “comfort and love

out of your books”.13

Mention of Liverpool roads or neighbourhoods remembered from childhood

brings particular pleasure, where an actual home and the reader’s remembered experience of it

become integral to their experience of the novel. (Williamson 2000, 272). Maaria Lenko’s (1998)

case study of Laila Hietamies (Finland’s ‘Catherine Cookson’) and her fans finds that the

dialogue between readers and writer “brings concepts such as nostalgia and a sense of locality

into this type of reading process. […] The homestead saved by a novelist or a filmmaker may

feel much closer and much more familiar than the experience of returning to the original place.”

(Lenko, 1998, 12). Lenko’s article explores the emotional reception of regional saga texts; one

reader says: “Anyway, to me your book was so real that I felt as if I was living inside everything

that happened.” Some readers supply details of their own increased home-making activities

resulting from their emotional reaction to the novels (Lenko, 1998, 10-12).

115

In Britain, the chief project of the regional saga narrative by the late 1990s had become

the interrogation of that central interdependence and its contemporary implications for women.

(I am not unaware, here, of some similarity between the centre of the cognitive map of Liverpool

that is the saga’s topographical palimpsest (especially as described in Hoggart’s ‘Landscape

with Figures’ (Hoggart, 1957, 33-58)) and the “confining walls” of Jameson’s “Plato’s cave”).

That interdependence, this community, and the attainment or denial of essential consumption is

a strong strand in Liverpool sagas (Williamson, 2000b), one understanding of the housewife’s

project; lack of representation of this and other women’s house work in official record and

heritage museums is an important impetus to writing and reading working-class sagas

(Williamson, 2003). A case study that exemplifies the operation of this palimpsest is a

consideration of World War Two as a discourse of place in Liverpool saga fictions. The World

War Two scenario allows all British working-class regional saga fictions to consider women’s

lives without men, and discussion of the renegotiation of their relationships with a variety of

spaces (e.g. the factory, the dance hall), discourses that can be continuous in Liverpool sagas

because of the prevalence of transitory men in a seafaring culture.

There is a great deal more to be said about the working-class saga author’s utilisation

of social and private space to illustrate her heroine’s (and her reader’s) quest to construct useful

cognitive maps of inner city spaces, which will constitute the focus of much of the next chapters.

The conventions of titling of Liverpool sagas foreground this focus, and perhaps this chapter at

this point may be seen to have evolved from a story of By The Waters Of Liverpool (Forrester,

Collins, 1981) through The Leaving Of Liverpool (Andrews, Corgi, 1992), and Going Home To

Liverpool (Francis, Piatkus, 1995) to a recognition that Home Is Where The Heart Is (Jonker,

Print Origination, 1993).

In conclusion: Jameson says of the historical novel that it “can no longer set out to

represent the historical past; it can only "represent" our ideas and stereotypes about that past”

(Jameson, 1991, 18). Yet the reworking of the Liverpool map through saga fiction has entailed a

significant re-vision of local history, where important discourses of gender, class, and social

change make possible a discussion of women’s lives at the end of the twentieth century

(Moody, 1997) in both organic and hypothetical relation to women’s lives in time just escaping

from memory. Jameson propounds that it

[…] should [not] be too hastily assumed that [Lynch’s] model - while it clearly raises very central issues of representation as such - is in any way easily vitiated by the conventional post-structural critiques of the "ideology of representation" or

116

mimesis. The cognitive map is not exactly mimetic in that older sense; indeed, the theoretical issues it poses allow us to renew the analysis of representation on a higher and much more complex level.” (Jameson, 1991, 37)

What I am attempting to reveal about saga fiction is that a mapping is taking place through

these fictions that cannot be navigated either through classic movies like Waterfront or by

visiting today’s Albert Dock museums. Through a complex set of discourses and the use of the

history of place as an Imaginary, sagas interrogate the “Real conditions of existence” of women

in Liverpool now, where fictional representations of the past are being used to interrogate the

very different realities for women of the present and “the urban totality in which they find

themselves.” (Moody, 1997, 319). As Forrester points out of Liverpool’s VE Day celebrations:

[…] For years afterwards, one would come across brick walls with Welcome home Joey or George or Henry, splashed across it in drippy, faded whitewash.

I never saw a message for the Marys, Margarets, Dorothys or Ellens, who also served. It was still a popular idea that women did not need things. They could make do. They could manage without, even without welcomes. (Forrester, 1985, 252).

Liverpool women, then, apparently must look to these fictions to discover a “welcome home”.

My analysis and discussion of the representation, or lack of representation, of working-class

women’s work and history in heritage and other museums in Liverpool and throughout the North

West, and the significance of that to the impetus to create saga fictions, continues this

discussion in the following chapter.

117

Endnotes

1 Michael Heseltine, 1980s conservative government minister in Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet.

Through the analysis of his team of business advisers, Liverpool’s regeneration through

investment initiatives, attracted by high-profile projects including the 1984 Garden Festival,

extended higher educational provision and the establishment of new national museums and

art galleries has proved a successful long-term economic strategy for Liverpool. This model

has since been successfully extended into other post-industrial cities such as Glasgow and

Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

2 Ken Worpole’s ‘Out of Hours’ study and report for Comedia, financed by the Gulbenkian

Foundation, published as Towns for People: Transforming urban life ([1992]1993) offers

discussion of government and capitalist intervention in town politics and planning at that time.

3 Worpole’s thesis is that “the 'retail revolution' of the 1980s is perhaps the key single factor that

changed the nature and meaning of town centres in the UK.” Worpole would restore traditional

city centre pubs and their communal life, but ignores the importance to women of specific city

centre shops and markets that saga fiction foregrounds.

4 The June 2003 announcement of the award of the ‘European City of Culture’ for 2008 is

already generating new approaches.

5 See Transatlantic Slavery Gallery, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool.

6 Participant observation at author signings and other meetings with readers (Appendix 2; Table

5) demonstrate that readers are mostly women, and all over fifty years of age; a number were

clearly over seventy. See also Alex Hamilton, 1993; Fowler, 1991.

7 Except for a few pages in Hoggart (1957, 41-53).

8 1958 was the year that the overhead railway was demolished.

9 These dates concur with those of particular interest to authors writing saga fictions since 1974

(Table 1).

10 See photograph at http://www.scottiepress.org/sr2003/sr2003.htm

11 Worse still was applying, always in person, to the Public Assistance Office that took over from

the workhouse in the early 1930s.

12 Andrews usually drew on real case histories when quoting these kinds of facts.

13 Reader at Skelmersdale meeting, 1998, (Table 5).