Changing Land Distribution System in India – A comparative analysis of 48 th and 59 th round By...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

6 -

download

0

Transcript of Changing Land Distribution System in India – A comparative analysis of 48 th and 59 th round By...

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 302

Changing Land Distribution System in India – A comparative analysis of

48th and 59th round

By Gaurav Arya Ph.D.Scholar

CSRD/SSS

Email: - [email protected]

Jawaharlal Nehru University

New Delhi-110067

Introduction

Agriculture in India holds a pride of place in terms of both income and

employment. It is a way of life that penetrates its organisational structure and moulds its value

system. In India unequal distribution of property and income forms the basis of agrarian

hierarchy. The prevailing value system justifies this existing inequality. Both the privileged and

the unprivileged believe that men are born unequal. The respect for higher status runs through

every level of the social system. The hierarchical values and un-equal social structures reinforce

each other thereby making the change of any status quo very difficult. Indian agriculture

comprises multiple social systems each displaying a different process of change. This structure

thus provides ample opportunities for research in land systems and reform procedures. Before

exploring the inherent complexities of the Indian agrarian sector, we shall trace the process of

evolution which contributed to this complex structure.

Land distribution and tenancy among the various social groups, especially in

rural India is important issue in these days because in rural areas land is major sources of income

and employment. But there is very diversification in land distribution in India. These

diversification increases the inequality in rural areas. The inequality is very high among different

social groups in rural areas because, in rural areas economy is based on agriculture. Some upper

society groups have their property right on agricultural land. On the other hand scheduled cast

and tribes are the most advantages to the agricultural land.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 303

In India where the agriculture is the prime source of livelihood for a vast

majority of people living in rural and tribal areas, land continues to be the pivotal property in

terms of both income and employment, around which socio-economic privileges and

deprivations revolve. Though the members of scheduled castes and tribes mostly reside in the

countryside and derive their livelihood by working on land, they are the most disadvantaged in

respect to the land. The incidence of landless is more having minuscule holdings or are

sharecroppers or other types of insecure tenants.

In India 10 percent of households are landless in 2003 while eighty percent are

marginal, the areas under them only 23 percent. On the other hand 0.6 percent households having

11.55 percent of owned land. India is a land of small farms, of peasants cultivating their ancestral

lands mainly by family labour. Although farms in India are typically are typically small

throughout the country, the average size holdings by state ranges from about 0.5 hectare in

Kerala and 0.75 hectare in Tamil Nadu to three hectare in Maharashtra and five hectare in

Rajasthan. Factors influencing this range include soils, topography, rainfall, rural population

density, and thoroughness of land redistribution programs in India. This various distribution of

land increases poverty and decreases efficiency of per capita per hectare. In this study we are

analysing the land distribution system in India among major states through a comparative study

between 48th

and 59th

round of NSSO (national sample survey organisation).

Literature review

The land reform (LR) policy was concretised for the first time in the First

Five-Year Plan (1951-56). Agrarian classes were classified into intermediaries, large owners,

small and medium owners, tenants at will and landless workers [Government of India 1951].

Special emphasis was given on the abolition of intermediaries, enactment of radical tenancy laws

and resumption of cultivation based on peasant proprietorship. The need for providing a ceiling

and lower limit to agricultural lands was recommended. The ceiling issue was later given proper

importance in the Agra session of the All India Congress Committee. Later the panel on land

reforms under Gulzarilal Nanda (1955) elaborated the method of imposition of ceiling, the unit

of ceiling fixation and the requisite precautions required to plug the loopholes of the ceiling law.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 304

The panel also dealt with the question of security of tenure and introduction of co-operation in

the case of non-viable units.

Land reforms have been treated as one of the principal instruments for the

creation of an egalitarian rural society, in tune with socialistic spirit, as provided in the preamble

and under part-4 of the constitution (Directive Principles of state policy). It has also been

included in the ninth schedule to ensure speedy and unhindered implementation of various

legislative measures. However, land reform being a state subject, the legislative as well as the

administrative responsibility devolves on states, and the union government lays down only the

general guidelines. Therefore, the nature of legislative measures and their implementation and

achievement are likely to vary from state to states because they are influenced by the complex

interaction of historical necessities and socio-political and economic forces, which are largely

state or region specific. In such a context, a comprehensive and comparative analysis of the

legislative measures of various states relating to land rights of the schedule groups and their

consequent effects on land distribution is imperative as these are issues of major policy concern.

Though the question of control and use of land among the scheduled castes and tribes has not

been left of the planning commission, 48 per cent of the population of scheduled entirely out of

scientific inquiry, it has received only occasional.

Mohanty B.B. (2001), in recognition of the basic proposition that poor land

ownership position of the scheduled groups accounts largely for their perpetual poverty and

makes them vulnerable to social injustice and exploitation, the government of India has made a

systematic endeavour to protect and promote their rights with regard to control and use of land

through land reforms and allied measures. Land distribution in India closely follows social

hierarchy. While the large landowners invariably belong to the upper castes, the cultivators

belong to the middle castes and the agricultural workers largely to the scheduled castes and tribes

(Beteille 1972).

Land being the important socially valued asset, its un-equal distribution helps

maintain the hierarchical structure and strengthen the basis of dominance of the privileged

groups by perpetuating inequality and deprivation in various socio-economic spheres. Seen from

this point, the idea of fair distribution of land directly strikes at the roots of such social relations.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 305

Therefore, the upper castes' landed interests have opposed the legislative measures with respect

to land redistribution through various methods (Mohanty, 2001). But when the magnitude of

resistance of the deprived people challenges the existing order or shows signs of potential threat,

the resultant change provokes reform measures. In an insensitive democracy like India, state

action is identified with people's action and people's empowerment rests on their collective

resistance and agitation. The measures to promote and protect the interests of the deprived are

not usually expected without persistent demands and protracted struggles.

Land reforms in India have been launched in response to compelling demands

expressed through agitation, struggle and movements (Dhanagare 1983, Radhakrishnan 1989).

But, land reform policy being fundamentally a political issue, the state passes legislation only to

pacify and neutralise the agrarian tension (Suri and Raghavulu 1996). In order to monitor the

implementation of such measures, the existence of strong social movements is crucial. The

entrenched dominant landowning privileged groups would never like to surrender their power

and privilege without exertion on them of mounting pressure from the deprived people.

According to census of India, (1991) 64 per cent of scheduled castes and 36 per

cent of scheduled tribes mainly workers are agricultural labourers as against 31 per cent of

others. It also reveals that 25 per cent of the scheduled castes and 55 per cent of scheduled tribes

are cultivators compared to 40 per cent of others. The poorest among the poor in the Indian

society are largely from these groups. As per the estimates castes and 51 per cent of scheduled

tribes are below poverty line.

The all India figure according to the millennium study by Chaddha, shows that

the share of scheduled castes in the total rural population, land and incidence of landlessness has

all increased. Land owned by these households has been highest in West Bengal (24 per cent).

On the other hand, for the scheduled tribes it is seen that the share in both population and land

has increased but share for incidence of landlessness has declined. Land owned by these

households has been high in Bihar, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and west Bengal. While, the share of

non-scheduled castes and tribes has declined for both population and land but have marginally

increased for incidence of landlessness. The incidence of landlessness among the SC households

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 306

stood at 13.34 per cent compared with 10.54 per cent among the non-SC and ST households and

11.50 percent among the ST households.

An understanding of the pattern of ownership and operational holdings of land

is, therefore of central importance to an understanding of the agrarian class structure. Data on

landholdings in India, in particular, on ownership holdings of land have been fraught with

problems. Data from land and livestock surveys conducted decennially by the national sample

survey organisation (NSSO) are the most important source of information on distribution of

landholdings in India. As part of these surveys, detailed data are collected on ownership and

operational tenancy, nature of land use, status of irrigation, and cropping pattern. According to

the 59th

round of the land and livestock surveys, only about 10 per cent households did not own

any land (Sharma 1994, 2007; Chaddha, 2004). Primary data-based studies from most states

report a much higher level of landlessness. Also, NSS surveys themselves report much higher

level of landlessness (of order of about 40 per cent) in terms of operational holdings. Such a

large level of discrepancy between landlessness in terms of ownership holdings and landlessness

in terms of operational holdings cannot be explained by the extent of tenancy.

Framework of the present study

The present study brings out various facts of households ownership holdings

ownership holding of the countries in rural areas. It covers different aspects of ownership

holdings in terms of alternative uses to which land is put, types and terms of lease, and their

variation over size classes of ownership holdings. It also brings out the estimates of area under

household ownership holdings, average size of holding, the number and proportion of landless

households etc. In the present study size distribution, the “broad size classes” are further merged

into six size classes. The first of these, called „nil‟ relates to households that operated no land or

operated a land of area of less than 0.02 hectare during the reference period. The other five size

classes are found along the lines adopted in the agricultural census of India.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 307

Broad categories of holding

Marginal: 1.000 hectare or less

Small: 1.001 - 2.000 hectare.

Semi-medium: 2.001 - 4.000 hectare.

Medium: 4.001 - 10.000 hectare.

Large: larger than 10.000 hectare.

Objectives

To examine the change in land distribution and area owned pattern among states over five

broad classes in 17 major states for 48th

and for 59th

round.

To estimate the percentage of landless households between 48th

and 59th

round.

To measure the inequality through Gini Coefficient in operational holdings between the

two rounds.

To analyze the effect of some variables on the farm land used for cultivation.

Database and methodology

The whole study is based on the reports of NSSO (national sample survey organisation) of 48th

and 59th

rounds.

Simple correlation and regression technique has been used to measure the effects of some

variables on the farm land used for cultivation.

Y = β0+β1 X1+β2 X2+β3 X3+β4 X4

Where Y is the dependent variable showing the % of farm land used for cultivation, X1 shows the % of male educated farmers, X2 shows the % of

female educated farmers, X3 shows the % irrigated area, and X4 shows the % of farmers using fertiliser on their land.

Analysis

Here, in this study we find a lot change and variation in households and area

owned by different classes of the farmers. The size of distribution of ownership holdings in India

is characterized by predominance of marginal category farmers. During 59th

round, the marginal

holdings constituted about 80% of the rural households but owned only 23% of total area. The

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 308

medium and large holders accounted only 3.6% of the households but had a combined share of

about 35% in the total land owned by all households in 59th

round. The proportion of marginal

households has risen, from 71.88 to 79.9 per cent during 59th

round in all India. In Kerala, it was

92.66 percent in 48th round increased to 95.3% in 59h round and areas increased from 54.5 to

60.72%. Rajasthan reported lowest marginal households in both rounds. On the other hand

decreasing trends in large households it decreases from 0.88 % to 0.66% during 59th

round and

areas decreased from 13.83% to 11.55 in all India. In Andhra Pradesh, there are 0.5% large

households but areas owned are 14.05% in 59th

round but in case of marginal households there is

82.7% having 21.78% areas. In Tamil Nadu there are 90.1% marginal households having only

33.2% area and 2.9% semi medium households having 22.09% area during 59th

round.

Findings

Findings in this study are the change in percentage of households and areas owned

between 48th

and 59th

rounds. We find that the percentage of all type of households is decrease

except marginal households, in marginal households (7.72) it is increasing trends between 48th

round and 59th

rounds at all India level. The owned area is decreasing also except marginal and

small. The percentage of small households (-2.62) is decreasing but percentage of owned area is

increases (1.79). There is decreasing trend also in large households in all states except Andhra

Pradesh and increasing trends in percentage of marginal households in all states. The rate of

growth in percentage is highest in Karnataka (12.28) and lowest in Kerala (2.67) in marginal

households. The percentage of semi medium household is decreasing an all the states, the

percentage of areas owned are also decreasing in all the states except Maharashtra (0.83) and

Orissa (5.34) in the same category. The percentage of medium households and areas owned by

them is decreasing in all states except Karnataka (2.9 acres) and Gujarat (7.13 acres) is increase.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 309

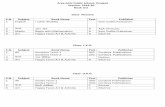

Table -1 Changes in different categories of households and their respective areas in all major states (in

%)

change in households change in area

states marginal small

semi

medium medium large marginal small

semi

medium medium large

AP 6.29 -3.25 -2.16 -0.78 0.11 0.57 -2.49 -2.99 -1.15 5.99

ASSAM 4.11 -0.62 -2.69 -0.63 -0.08 6.37 5.8 -6.7 -4.21 -1.3

BH 8.84 -4 -3.3 -1.44 -0.1 13.49 1.45 -5.92 -9.12 0.19

GJ 9.97 -3.28 -4.99 -1.12 -0.67 4.05 0.61 -5.82 7.13 -6

HR 18.16 -3.69 -10.49 -3.63 -0.37 5.19 2.4 -8.92 -3.03 4.35

HP 4.53 -0.05 -2.33 -2.08 -0.15 8.81 7.67 -1.8 -12.05 -2.6

J&K 14.1 -8.88 -4.25 -1.18 0.2 10.74 -7.91 -6.3 -4.11 7.58

KT 12.28 -4.17 -6.15 -1.18 -0.78 5.6 1.1 -4.64 2.9 -5

KE 2.64 -1.82 -0.76 -0.04 -0.02 6.21 -3.06 -3.54 0.83 -0.7

MP 9.32 -1.19 -4.1 -3.24 -0.78 4 3.58 0.83 -4.13 -4.3

MH 9.53 -1.09 -3.14 -4.04 -1.25 5.36 4.96 5.34 -6.08 -9.6

OR 10.35 -4.72 -3.64 -1.5 -0.02 15.15 -0.1 -6.27 -8.1 -0.6

PB 6.67 -0.48 -4.31 -2.01 -0.08 1.98 3.28 -4.91 -3.54 3.09

RJ 10.7 -2.03 -3.71 -3.79 -1.27 3.84 1.15 -0.29 -3.15 -1.6

TN 2.97 -2.31 -0.91 0.28 -1.11 -0.07 -3.14 -2.06 8.42 -3

UP 6.6 -2.43 -3.12 -1.16 -0.11 7.47 2.5 -5.08 -3.49 -1.4

WB 6.18 -3.78 -2.54 -0.51 0 16.94 -2.4 -11.1 -3.6 0

All

India 7.72 -2.62 -3.28 -1.54 -0.28 6.12 1.79 -2.6 -2.99 -2.3

Source: Calculated from reports of 48th and 59th rounds of NSSO

Through Gini coefficient we measure the degree of concentration of size

distribution of holdings; it shows a change in 59th

round in many states from the previous 48th

round. In the table the values of Gini coefficient shows a decreasing trend or can say low values

for many states except some agriculturally developed states like Punjab and Haryana, which are

showing a high value from 0.694 to 0.706 and 0.645 to 0.675 respectively for the states in 48th

and 59th

rounds.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 310

Table-2 Gini Coffecient of selected states

States AP ASSAM BH GJ HR KT KE MP MH OR PB RJ TN UP WB All

India

48th 0.53 0.41 0.53 0.57 0.65 0.58 0.39 0.53 0.57 0.46 0.69 0.59 0.53 0.5 0.43 0.591

59th 0.54 0.37 0.42 0.61 0.68 0.54 0.35 0.53 0.53 0.38 0.71 0.61 0.51 0.45 0.313 0.557

Source: Calculated from reports of 48th and 59th rounds of NSSO

Source: Calculated from reports of 48th and 59th rounds of NSSO

Another finding shows the trends in landless households between 48th

and 59th

rounds. The 59th

round shows that there is decreasing trends in landless households; the

percentage of landless householders has decreased from 11.3% to 10% in 59th

round at India

level. In Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil

Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and west Bengal, the proportion of landless has decreased in 59th

round.

Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Jammu Kashmir and Karnataka are the states in which the proportion

of landless households has increased. Haryana (5.5) is the state in which proportion of increasing

trends in landless households is highest followed by the Himachal Pradesh (4.6) and Karnataka

(4.1). In west Bengal (-4.8) there is sharply decreasing trend in landless households.

Table-3 Changes in proportion of landless households

States AP ASSAM BH GJ HR HP J&K KT KE MP MH OR PB RJ TN UP WB

All

India

48th 12 13.4 8.6 16.3 3.7 10.4 2.8 10 8.4 15.2 19.6 13.8 5.9 6.4 17.9 4.9 11 11.3

59th 14 8.1 7.6 13.6 9.2 15 3.3 14.1 4.8 12.1 17.7 9.6 4.6 5.7 16.6 3.8 6.2 10

%

change 2.4 -5.3 -1 -2.7 5.5 4.6 0.5 4.1 -4 -3.1 -1.9 -4.2 -1.3 -0.7 -1.3 -1.1 -4.8 -1.3

Source: Calculated from reports of 48th and 59th rounds of NSSO

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

Gini cofficient

48th

59th

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 311

Source: Calculated from reports of 48th and 59th rounds of NSSO

Results

Correlation coefficient

VAR X1 VAR X2 VAR X3 VAR Y VARX4

VA R Y Pearson Correlation -.508* -.623

** .070 1 .628

**

Sig. (2-tailed) .044 .010 .798

.009

N 16 16 16 16 16

The above table shows the correlation between the variables X1, X2, X3, X4 (%

male farmers educated, % female farmers educated, % irrigated area, % distribution of land

holdings and % of farmers using fertiliser respectively). Correlation coefficient is significant at

5% and 1% level. Correlation is negative for the two variables X1and for X2. And positive for

the X4varible, but there appear no correlation between the X3 variable. Negative correlation

shows that the education in the farmers‟ male and female both are highly educated having low

distribution of farm holdings or we can say the uneducated farmers are more engaged in farm

sector. Other finding shows the farmers using more fertilisers eager for the high distribution of

farm holdings.

Y = 55.04-0.286 X1-0.262 X2-0.131 X3+0.662 X4

t value 2.275 -.667 -1.017 -1.091 2.285

Value R square 0.650

0

5

10

15

20

25

48th

59th

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 312

The value of R square shows that explanatory variables are well captured by

dependent variable. This high value shows high association between the dependent and

explanatory or independent variable. But there is negative coefficient for the X1, X2 and X3

variables. So association is negative for the X1, X2, and X3 variables it shows these variables are

affecting negatively to the dependent variable. Only the X4 variable shows the positive

association between the dependent and independent X4 variable.

Major findings

Percentage of marginal, small and semi medium households has decreased in all states.

Percentage of large households has decreased in all states excluding Andhra Pradesh and

Tamil Nadu.

Percentage of marginal areas owned has increased except Tamil Nadu.

Medium area owned has decreased in all states except Gujarat, Kerala, Karnataka, and

Tamil Nadu.

Large areas owned have decreased in all the states except Andhra Pradesh, Bihar,

Haryana, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu.

Values of Gini coefficient also show decreasing trends except some agricultural rich

states like Punjab, Haryana, and few marginal in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Percentage of landless households has decreased from 11.40 % to 10%.

Coefficient of correlation shows negative values for the % male farmers educated and for

female educated farmers but shows a positive relation between operation farm holdings

and farmers using of fertilisers.

Regression value shows the negative association between the all variables taken under

study except the % of farmers using fertilisers in their farms.

Conclusion

After studying and analysing the major findings we can conclude that farm

percentage of operational households has decreased between two rounds in all India except some

few states. But percentage area holding has decreased for few states in few categories. Gini

coefficient showing concentration also showing a decreasing trend in all India except some farm

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 313

rich states. Correlation and regression shows negative relation which express the distribution of

farm holding is high among the uneducated farmers not in the educated farmers. Still the

agriculture farmers are highly uneducated.

References

Bandyopadhyay D., (1986), “Land Reforms in India: An Analysis”, Economic and Political

Weekly, vol. 21, No. 25/26, pp.A50-A56.

Bandyopadhyay Rekha, (1993), “Land System in India: A Historical Review”, Economic and

Political Weekly, Vol. 28, No. 52, pp. A149-A155.

Beteille, A. (1972), “Inequality and Social Change”, Bombay: Oxford University Press

Chaddha, G.K., S Sen and H.R. Sharma (2004): Land resources: State of Indian Farmer,

Academic Foundation, New Delhi. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 36, No. 40, pp. 3857-

3868.

Dhanagare, D.N. (1983). Peasant Movements in India, c.1920-1950, Delhi: Oxford University

Press.

Mohanty B. B., (2001), “Land Distribution among Scheduled Castes and Tribes”.

National Sample Survey Organisation (1992), “Land and Livestock Holding Survey”, Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India.

National Sample Survey Organisation (2003), “Some Aspects of Operational Land Holdings in

India”, Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India.

Prasad Sakti, Padhi and K. N. Nair, (2007), “Dynamics of Land Distribution: An Alternative Approach

and Analysis with Reference to Kerala”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 28, No. 12/13, pp. A29-

A36.

Radhakrishnan, P. (1989). “Peasant Struggles, Land Reforms and Social Change: Malabar

1836-1982”, New Delhi: Sage.

Sharma, H.R., (1994), “Distribution of Land Holdings in Rural India, 1953-54 to 1981-82”,

Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 29, No. 39, pp. A117-A128.

Suri K.C and C.V Raghavulu (1996), “Agrarian Movements and Land Reforms”. Land Reforms

in India (vol.3): Andhra Pradesh-People’s Pressure and Administrative Innovations. Ed. B.N

Yugandhar. Sage Publication India.

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 314

Appendix

Table-4 Changes in different categories of households and their respective areas in all major states (in %)

PERCENTAGE CHANGE IN HOUSEHOLDS

Percentage change in area

marginal small

semi

medium medium large all marginal small

semi

medium medium large all

AP 2003 82.7 9.1 5.3 2.6 0.5 100 21.9 20 21.2 22.9 14.1 100

1992 76.4 12.4 7.46 3.38 0.39 100 21.3 22.4 24.2 24.1 8.06 100

ASSAM 2003 81.8 14.2 3.6 0.5 0 100 44.4 34.9 16.4 4.32 0 100

1992 77.7 14.8 6.29 1.13 0.08 100 38.1 29.1 23.1 8.53 1.29 100

BH 2003 89.4 7.1 2.7 0.7 0.1 100 42.1 25.3 18.5 9.56 4.63 100

1992 80.6 11.1 6 2.14 0.2 100 28.6 23.8 24.5 18.7 4.44 100

GJ 2003 73.3 11.9 7.2 6.5 1 100 13.6 16.1 19 39.1 12.3 100

1992 63.3 15.2 12.2 7.62 1.67 100 9.55 15.4 24.8 32 18.2 100

HR 2003 77.2 9.8 7.7 4.9 0.4 100 13.2 15.8 24.6 34.1 12.3 100

1992 59 13.5 18.2 8.53 0.77 100 7.96 13.4 33.5 37.2 7.91 100

HP 2003 83.7 11.5 4.1 0.5 0.1 100 43.8 28 19.8 6.45 2.03 100

1992 79.2 11.6 6.43 2.58 0.25 100 35 20.4 21.6 18.5 4.6 100

J&K 2003 77.5 15 5.6 1.7 0.2 100 36.3 25.5 19.5 11.1 7.58 100

1992 63.4 23.9 9.85 2.88 0 100 25.5 33.4 25.8 15.2 0 100

KT 2003 71 14.1 8.8 5.4 0.7 100 16.7 19.5 23.2 29.5 11.2 100

1992 58.7 18.3 15 6.58 1.48 100 11.1 18.4 27.8 26.6 16.2 100

KE 2003 95.3 3.5 0.9 0.3 0 100 60.7 21.1 10.8 7.16 0 100

1992 92.7 5.32 1.66 0.34 0.02 100 54.5 24.2 14.3 6.33 0.66 100

MP 2003 61.7 18 12.1 7.1 1.1 100 11.6 19.1 25.8 31.3 12.3 100

1992 52.4 19.2 16.2 10.3 1.88 100 7.61 15.5 25 35.4 16.6 100

MH 2003 69 13.1 12 5.1 0.8 100 12.4 17.6 30.9 27.4 11.8 100

1992 59.5 14.2 15.1 9.14 2.05 100 7.02 12.6 25.5 33.4 21.4 100

OR 2003 85.5 9.7 3.7 0.9 0.1 100 41.5 27.1 19.7 9.98 1.78 100

1992 75.2 14.4 7.34 2.4 0.12 100 26.4 27.2 26 18.1 2.4 100

PB 2003 76.3 9.5 7.9 5.1 1 100 9.16 15.6 25.3 34.5 15.3 100

1992 69.6 9.98 12.2 7.11 1.08 100 7.18 12.4 30.2 38 12.2 100

RJ 2003 55.2 16.5 14 10.1 4.1 100 9.26 11.2 18.6 28.4 32.5 100

1992 44.5 18.5 17.7 13.9 5.37 100 5.42 10 18.9 31.6 34.1 100

TN 2003 90.1 5.7 2.9 1.2 0 100 33.2 23.1 22.1 20.6 1.23 100

1992 87.1 8.01 3.81 0.92 1.11 100 33.3 26.2 24.2 12.2 4.18 100

UP 2003 81 12.3 4.8 1.6 0.1 100 34.9 27.4 20.7 14.7 2.34 100

1992 74.4 14.7 7.92 2.76 0.21 100 27.4 24.9 25.8 18.1 3.73 100

WB 2003 92.1 5.7 1.4 0.2 0 100 58.2 25.7 11.9 4.02 0 100

1992 85.9 9.48 3.94 0.71 0 100 41.3 28.1 23 7.62 0 100

ALL INDIA 2003 79.6 10.8 6 3 0.6 100 23.1 20.4 22 23.1 11.6 100

1992 71.9 13.4 9.28 4.54 0.88 100 16.9 18.6 24.6 26.1 13.8 100

Source: Calculated from reports of 48th and 59th rounds of NSSO

CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 1 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202

International Research Journal of Commerce Arts and Science http:www.casirj.com Page 315

Table-5

variables x1 x2 X3 y X4

States

% MALE

farmer

educated

% female

farmer

educated

%

irrigated

area

%distribution of

holdings for

cultivation

% of farmer

households using

fertilisers

AP 47.9 20.7 26.5 61.45 55.5

ASSAM 85.3 71.4 8.5 71.8 57.5

BH 62 15.6 72 81.2 90

GJ 73.1 37.6 30.5 59.7 59.5

HR 73.6 31.3 75 55.6 57.5

J&K 56.3 31.2 21 86.25 86.5

KT 64.6 34.2 21 53.95 60

KE 93.8 85.4 21.5 18.2 55.5

MP 59.3 22.2 33 74.55 55.5

MH 74.2 45.7 25 67.55 61

OR 63.6 22.2 14 61.45 45.5

PB 63.5 48.1 94.5 49.65 54.5

RJ 51.9 15.4 17.5 60.5 47

TN 71.2 43 51 50.45 51

UP 60.4 18.9 73 82.8 83

WB 73.4 13.7 46.5 71.85 80.5