Centerville/Interzone, or: Map Ref. 41ºN 93ºW

Transcript of Centerville/Interzone, or: Map Ref. 41ºN 93ºW

132 Enrique Ramirez Centerville/Interzone 133

Centerville/Interzone, or: Map Ref. 41°N 93°W

ENRIQUE RAMIREZ

From the root of our national psyche, an Exhibit of sorts. The evidence is probative, sure, but what other admissible facts, what other morsels of conjured truth are there to be found? To our esteemed Jury of Peers, to this coterie of readers whose only task is to take in this skein of confabu-lation, let me assure you that this Exhibit is real, but only in the sense that it is something that occurs in space and time. Like Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom (né Virag) in the “Ithaca” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), we levitate into air, beyond the stratosphere, holding our breaths as satellites and space junk whir by our geostationary lockstep. We peer into the cerulean and phthalo patchwork world below and there, a surface once familiar rendered now into a joining of parallel and meridians. Decumanus and cardo intersect somewhere in the glacial moraines of southern Iowa, among the hills the Sioux call paha.

Rivers of anthracite once flowed deep underneath this rolling, hummocky prospect like blackened veins. On the surface, a network of railroad lines traced the land’s carboniferous circulatory system with iron spurs. Steam locomotives bear their bills of lading, emissaries of shipping lines that read like an abecedarium of Midwestern capital: Chi-cago, Burlington & Quincy; Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul; Keokuk & Western; Iowa and St. Louis. Affluents of coal and iron join at the headlands of the Mystic Coal Bed, near a city founded in 1846, first as “Chaldea,” a riverine name, reminiscent of that alluvial flat where the Tigris and Euphrates once joined, now a settlement attracting a host of New Englanders, Central Europeans and Scandinavians, as well as profiteers seeking bounty from individual treaties with Sac, Fox, and Winnebago tribes in the wake of the Black Hawk War. Less than a year later, on January 18, 1847, a law issued by the first Iowa legislature proclaimed that this town, the seat of Appanoose County, be renamed Centerville (instead of “Senterville,” for the Tennessean William Tandy Senter, long admired by the city’s founder, the surveyor Jonathon F. Stratton). Stratton himself was an expert in all things Centerville, and in 1878, along with other early Iowans, became one of several sources for an oral, comprehensive history of Appanoose County.

Of these men, Colonel James Wells, a veteran of the War of 1812 and the Black Hawk War, became known as one of Iowa’s most famous homesteaders. Around 1839, he built a cabin in “Section 16, Township 67, Range 16” in the County, a platted quadrant near the berm where the Missouri, Iowa & Nebraska railroad passed over the Indian River.

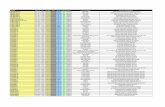

FIG 1: “Views of Centerville” (Source: L.L. Taylor, ed. Past and Present of Appa-noose County, Iowa: A Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achieve-ment (Chicago: S.J. Clarke, 1913), n.p.).

134 Enrique Ramirez Centerville/Interzone 135

And three years later, walking near a cabin owned by one “A. Kirken-dall,” Wells spotted a man sitting at the base of a tree with his torso slumped forward. He approached the body and noticed a small, charred bullet hole rimmed with dried blood in the middle of the man’s fore-head. He must not have been aware of the marksman sighting him from a distance before the fatal shot—Wells found a pencil and small, lined ledger book in the man’s hands with entries resembling “the notes of someone looking up lands; but as the township lines had not been laid, this seemed inexplicable.”1 This was the county’s first recorded death, a plot line braided into a larger, malevolent act of fiction, for “It is barely possible that the man had been riding away a horse not his own, had been followed, captured and put to death, and that the entries had been made by his executioners, in order to lead possible inquiry on a false scent.”2 Plot line is no different from plat line, as Wells’ homesteading is also a supreme act of fiction, a conjuring of something tangible from what once was a series of orthogonal lines on paper.

Such narratives could be skewed, literally. In his Past and Present of Appanoose County, Iowa (1913), L.L. Taylor, a former Justice of the Peace for the County, claimed that a “brief historical sketch” would suffice as a “fitting introduction to the history of the young and thriv-ing state of Iowa.”3 Yet the editor of the 1878 history of Appanoose County informed the reader, “In the absence of written records, it has often occurred that different individuals have given sincere, honest, but, nevertheless, somewhat conflicting, versions of the same events, and it has been a matter of great delicacy to harmonize these conflict-ing statements.”4 For his own history of the County, Taylor included photographic plates (fig. 1), taken from the tops of buildings or at street level, of various locales within Centerville. Places like South Eighteenth Street and even the Shawville Mine appear devoid of people. The excep-tion is the photograph of North Main Street, capturing a gathering of people and horses around a trolley making a slow jug-handle turn into the street, the only photograph that is not clipped or placed at an odd angle. These six “Views of Centerville” are distributed roughly into dual columns, yet some of the images are rotated and layered upon each other. It is far removed from the rough 4x4 grid of townships that give Appanoose County its fixed, quadrangular shape. These two images, map and photograph, offer competing narratives of Centerville. And yet the obsessive regularity of the Appanoose grid does not necessarily hint

at any kind of veracity. Centerville, however, is a name that hints to space, location, and

orientation. It is the middle of a grid, a town in the cartographic center of Appanoose County (fig. 2). Centerville finds its kindred, toponymi-cal spirit in Interzone, a name given by another Midwesterner, William Seward Burroughs, as shorthand for the International Zone in Tangiers, an exotic destination in our literary imagination that, like Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria, becomes a code for something illicit. Whereas Durrell’s Alexandria became a purgatory for lovesick expatriates, Interzone was something much darker, last stop in a circuit for dead-eyed junkies craving for pyrethrum (distilled from the crushed flower heads of the Dalmatian Chrysanthemum, T. cinerariifolium), seeking night passage across the rachial divides of the Hindu Kush and into the incense-filled foyer of the Hotel Massilia on Rue Marco Polo, marking their transit across the continents as if dragging a leadened spike across a map. Two such itineraries begin their convergence, gliding between the Galeries Lafayette and storefronts advertising passage across the Strait of Gibraltar, on to the Boulevard Pasteur and intersecting at the Hotel Rembrandt in the nouvelle ville de Tanger. It was there that Burroughs

FIG 2: Map of Appanoose County, Iowa (Source: Western Historical Society, The History of Ap-panoose County, Iowa: Containing a History of the County, Its Cities, Towns, &c., a Biographi-cal Directory of Citizens, War Record of Its Volunteers in the Late Rebellion, General and Local Statistics, Portraits of Early Settlers and Prominent Men, History of the Northwest, History of Iowa, Map of Appanoose County, Constitution of the United States, Miscellaneous Matters, &c. (Chicago: Western Historical Society, 1878), n.p..

136 Enrique Ramirez Centerville/Interzone 137

saw Carnet de Voyage au Sahara, a show featuring English painter Brion Gysin’s aquarelles made in the North African dune seas, among the seif and barkhan. The two met briefly, with Gysin describing Burroughs as trailing “long vines” of peyote plant and adorned by an “odd blue light” emanating from his hat.5 Another convergence occurred in 1960 in Paris, where Gysin introduced Burroughs to the Dadaist penchant for composition via the “cut-up” and “fold-in,” a method of writing by literally manipulating physical scraps of text to conjure sentences, paragraphs, and even entire novels. Burroughs embraced the cut-up technique only shortly after he dispatched his first and most well known novel, Naked Lunch (1959), a dense, hallucinatory journey through the belly of America, via Tangier, that ends with an augur’s instructions to the reader, a channeling from a near-future: “You can cut into The Naked Lunch at any intersection point.”6

In reaching this and subsequent “intersection points,” Burroughs transforms writing into a kind of autobiographical transport whose docket conveys grim spectra spanning everything from an addict’s apho-rism to a doper’s needle. In a typical jeremiad, perhaps written under an oneiric haze of chloral hydrate, Burroughs channels his grandfather, William S. Burroughs I, founder of the American Arithmometer Com-pany, invoking something of a junky’s notion of eternal return when he writes, “So listen to Old Uncle Bill Burroughs who invented the Burroughs Adding Machine Regulator Gimmick on the Hydraulic Jack Principle no matter how you jerk the handle result is always the same for given co-ordinates.”7 Unlike grandfather Burroughs the First, famous for his hardline drawings, etchings, and centers rendered with sharpened styluses under the mirrored arc of a microscope, Burroughs opted for something more expansive: “In my writing I am acting as a map maker, an explorer of psychic areas, … a cosmonaut of inner space, and I see no point in exploring areas that have already been thoroughly surveyed.”8 This mania for maps and mapmaking would continue in The Ticket That Exploded (1962), a true “cut-up” novel, a science fiction nightmare where giant crabs roam the landscape at the behest of the nefarious, intergalactic enterprise known as the Nova Mob. In this novel, the autobiographical and cartographical collapse into a single line of text, a moment when Burroughs maps his family history onto his own fictions: “Word is an array of calculating machines from Florida up to the old North Pole—Image track goes with it.”9 Indeed, Burroughs jettisons

linear narratives in favor of something more like a film unspooling to the end only to spool back to the beginning in an ouroboros-like man-ner. The dead man slouched in front of Kirkendall’s cabin, trepanned in order to unburden a secret of Iowa history, who finds a parallel in Burroughs shooting his common-law wife Joan Vollmer in the head during a drunken game of “William Tell” in Mexico City on January 6, 1951—a montage connecting, compressing, and circulating images from disparate histories. Yet as critic Mary McCarthy observed in her review of Naked Lunch, Burroughs “has no use for history, which is all ‘ancient history,’” a moment reminiscent of another doper, the nefari-ous Wimpe, salesman for Ostarzneikunde GmbH (a subsidiary of I.G. Farben) in Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), divulging to the Red Army operative Vaslav Tchitcherine that his role is not to inter-pret history, but rather to “Die to help History grow to its predestined shape.”10 Like Bloom and Dedalus, Burroughs levitates into outer space, a “planetary perspective” that reveals another form, one where history is a “sloughed-off skin” that “shrivels into a mere wrinkling or furrowing of the surface as in an aerial relief-map or one of those pieced-together aerial photographs known in the trade as mosaics.”11

“[C]ut the prerecordings into air into thin air”: so concludes The Ticket That Exploded with a statement that is not of the air, but all-too-grounded, a reminder that the authorial act, the committing of words to the page, is really no different than cutting and pasting them on the flat surface of a page.12 Stories, characters, and fictions may be com-municated from hands to paper via a keystroke on the ribbon of an Antares or Hermes Rocket typewriter (or with a microphone that com-mits the author’s words as magnetized particles onto cellulose acetate, spun through a Nagra recorder’s tape head), yet they are a heaped into a jumble of words, sentences, and paragraphs that become something recognizable, something readable. What is a novel but a mosaic of words, a pact between author and reader that the stochastic jumble of text, the endless non-sequiturs, the breakneck changes in rhythm and pacing, will resemble something like a story, one that makes up for a lack of resolution with a relentless direction and energy? Narrative becomes a topographical construct, a bailiwick with its own features, courses, and jurisdictions. It is a world unto itself, its essence captured on the dust cover to Book No. 91 of the Traveller’s Companion Series of Maurice Girodias’ Olympia Press (fig. 3), the 1962 first edition of The Ticket

138 Enrique Ramirez Centerville/Interzone 139

FIG 4: William S. Burroughs, “Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning,” My Own Mag, No. 4 (1964) (Source: Reality Studio: A William S. Burroughs Community, http://realitystudio.org/bibliographic-bunker/my-own-mag/my-own-mag-issue-4/).

That Exploded. Here, an aerial photograph, presumably of a World War One-era French countryside, reveals a silvery, hoary ground of convex, concave, and cyclic polygons stitched together randomly. It covers only half of the dust cover, with a simulated tear delimiting the border be-tween image and text, an allusion to cutting-up, and underneath, “The Ticket That Exploded” appears in red grease pencil with Burroughs’ name typeset in all caps. Aerial photography and cut-up writing here become literary equivalents for the first time, a terrain where two mod-ernist tropes—the aerial regard surplombant and fragmented, multiper-spective writing—intersect to create their own terrain. More evidence of this appeared in 1964, when Burroughs published a small single-page cut-up entitled “Warning Warning Warning Warning Warning Warn-ing Warning Warning Warning” (fig. 4) for the experimental literary magazine My Own Mag. At the very top of the page, an admonition, also typeset in all caps, refers to aerial nuclear bombardment, while at the

FIG 3: Dust Jacket to Traveller’s Companion Series No. 91, William S. Burroughs, The Ticket That Exploded (Paris: Olympia, 1962) (Source: TRB Booksellers, Albany, NY).

140 Enrique Ramirez Centerville/Interzone 141

bottom, sentence fragments assemble into an 8x4 grid, “to be read every which way.” Yet the numbered columns point to a contradiction, one where the orthogonal arrangement of meridians and parallels results in something that is not regular, not ordered, but produced and fortuitous. This has always been the case with maps and aerial photographs, avatars for an incontestable way of looking at the world, an ironclad epistemol-ogy that is but a kind of highly-attenuated, high-altitude abstraction succumbing to all the vagaries and caprices of interpretation. As the so-ciologist Hans Speier noted in 1941, aerial views and maps are instances where science and technology “become subservient to the demands of effective symbol manipulation.”13 An assembly of plats into an aerial mosaic, the identification of “Section 16, Township 67, Range 16” in Appanoose County—these may correspond to a cartographic reality, yet they are fictions that appease our desire to conjure order out of disorder.

Buoyed above the Midwest in geosynchronous orbit, we once again peer below through our splayed feet at another series of lines, intersecting slightly north of Centerville, in Monroe County, Iowa, a point between Chariton and Ottumwa, on the asphalt surface of U.S. Highway 34, the Red Bull Highway, named after the 34th Infantry Division, the first Army unit deployed to Europe during World War II. There are even coordinates: 41°N 93°W, or simply, “Map Ref. 41°N 93°W,” which is the fourth track of the second side of English band Wire’s 1979 album 154 (fig. 5). Recall vocalist Colin Newman’s words in the first verse, a reminder of what is underneath the North American grid:

Straining eyes try to understand

The works, incessantly in hand

The carving and paring of the land

The quarter square, the graph divides

Beneath the rule, a country hides14

With this evocation of the telltale Jeffersonian grid firmly in place, now listen to what is “beneath.” Now, carve and pare the Ampex tapes, cut the prerecordings into air into thin air acetate inscribed and sprinkled with magnetized particles corresponding to the peaks and valleys of an audio recording. Take out the strands of horsehair from your violin’s bow. Replace with a strip of tape, a recording of William S. Burroughs’ reading the words “LISTEN TO MY HEARTBEAT.” Replace your violin’s bridge with an amplified, magnetized tape head (fig. 6). Push and pull the bow, collé, détaché, louré … until the author’s words become

FIG 5: (LEFT) Wire, 154, 33 1/3 rpm (EMI Records, 1979) (RIGHT) Wire, Map Ref 41°N 93°W, 45 rpm (Harvest Records, 1970).

FIG 6: Laurie Anderson, Tape-Bow Violin, from For Instants: Part 5, Amsterdam: De Appel, 1977 (Source: Museum of Modern Art, New York, Please Come to the Show: Invitations and Event Flyers from the MoMA Library, http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2013/please_come_show/).

142 Enrique Ramirez Centerville/Interzone 143

NOTES

1. Western Historical Society, The History of Appanoose County, Iowa: Containing a History of the County, Its Cities, Towns, &c., a Biographical Directory of Citizens, War Record of Its Volunteers in the Late Rebellion, General and Local Statistics, Portraits of Early Settlers and Prominent Men, History of the Northwest, History of Iowa, Map of Appanoose County, Consti-tution of the United States, Miscellaneous Matters, &c. (Chicago: Western Historical Society, 1878), 334.

2. Ibid.3. L.L. Taylor, ed. Past and Present of Appanoose County, Iowa: A Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achieve-

ment (Chicago: S.J. Clarke, 1913), 1.4. Western Historical Society, Preface to The History of Appanoose County, Iowa, n.p.5. Brion Gysin, Let The Mice In (New York: Something Else Press, 1973), 8.6. Burroughs, Naked Lunch (New York: Grove Wiedenfeld, 1992 [1959]), 203.7. Burroughs, Introduction to Naked Lunch, xviii-xix.8. Burroughs, “The Future of the Novel” (1964), in Randall Packer and Ken Jordan, eds. Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual

Reality (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001), 294.9. Burroughs, The Ticket That Exploded (New York: Grove Wiedenfeld, 1994 [1962]), 147.10. Mary McCarthy, “Dejeuner sur l’Herbe,” The New York Review of Books, Vol. 1, No. 1 (February 1, 1963), n.p. Thomas

Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (New York: Viking, 1973), 715.11. Mary McCarthy, “Dejeuner sur l’Herbe,” The New York Review of Books, Vol. 1, No.1 (February 1, 1963), n.p.12. Burroughs, The Ticket That Exploded, 217.13. Hans Speier, “Magic Geography”, Social Research, 8:1/4 (1941), 31314. Graham Lewis, Colin Newman, and B.C. Gilbert, “Map Ref. 41°N 93°W,” by Wire, in 154, EMI, 1979, 33 rpm.15. Laurie Anderson, “Sharkey’s Day,” in Mister Heartbreak, Warner Bros., 1984, 33 rpm. For her performance of “Late Show,”

from her concert film, Home of The Brave (1986), Anderson played a tape-bow violin with a recording of William S. Bur-roughs’ saying “Listen to my heartbeat.”

elongated and slowed down in sonic space. Now, listen as another singer, actually an artist, Laurie Anderson, also from the Midwest, enunciates, “Deep in the heart of darkest America. Home of the Brave. Ha! Ha! Ha! You’ve already paid for this. Listen to my heart beat.”15 Landscapes become images. Images become words. And words recorded, cut-up, splice and reassemble to create a fictional America.

From Earth orbit down to the depths of “darkest America” lurking somewhere underneath its patchwork topographies, from handwritten plats and grids inscribed into the first county registers in Appanoose County, Iowa, and moving forward to a more recent past where dead authors come to life as voices bowed across electric violins, consider the lines journeyed, the paths traversed. We can use any number of devices to describe these spatial and temporal transits, from lines of longitude and latitude to timelines. These lines meet in locales recognizable be-cause of names like Centerville or titles like “Map Ref. 41°N 93°W.” We can even arrange these lines spatially, an ordered logic where lines marking changes in vertical altitude and passages from past to present to future time become vectors, and their intersecting planes form, of all things, a structure. And of this structure, let us give it a name. “Fiction” has a nice ring to it.