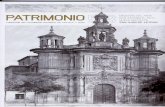

La imagen de la Corte en Valladolid: Palacio Real y palacio de los condes de Benavente

Casual or ritual: The Bell Beaker Deposit of La Calzadilla (Valladolid, Spain)

Transcript of Casual or ritual: The Bell Beaker Deposit of La Calzadilla (Valladolid, Spain)

lable at ScienceDirect

Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e96

Contents lists avai

Quaternary International

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate/quaint

Casual or ritual: The Bell Beaker deposit of La Calzadilla (Valladolid,Spain)

Corina Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck a,*, Elisa Guerra Doce b, Germán Delibes de Castro b

aDpto. de Prehistoria y Arqueología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Campus de Cantoblanco, C/ Francisco Tomás y Valiente 1, E-28049 Madrid, SpainbDpto. de Prehistoria, Arqueología, Antropología Social y CC.TT. Historiográficas, Universidad de Valladolid, Plaza del Campus s/n, 47011 Valladolid, Spain

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Available online 8 November 2013

* Corresponding author.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (C. Liesau

[email protected] (E. Guerra Doce), [email protected] (G

1040-6182/$ e see front matter � 2013 Elsevier Ltd ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.046

a b s t r a c t

The aim of this paper is to examine a Chalcolithic deposit found within a pit. The deposit contains asignificant amount of Beaker pottery, amongst other artefacts, as well as a few human bones and apeculiar faunal assemblage. The singularity of the faunal remains found made it necessary to carry out adetailed taphonomic study, since the deliberate selection of the anatomical parts of many species hasbeen documented. The presence of pig foetal bones, possibly corresponding to different litters, is alsonoteworthy. The assemblage reveals diverse predepositional origins, also confirmed by radiocarbondating: The cranial bone of an aurochs, which has undergone lengthy exposure, is the only finding in thispit with intensive weathering surface modification. This bone was probably introduced as a token at alater date, and is several hundred years older than the other dated sample from the pit.

� 2013 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The archaeological site of La Calzadilla, at Almenara de Adaja, islocated in the south of Valladolid, Spain (geographic coordinates:41� 110 3600 N, 4� 4000800 W). The area rests on the sandy soil sur-rounding the basin of the Adaja river, one of the tributaries of theDuero (Fig. 1.1). This landscape was intensely occupied throughoutPrehistory, probably due to the abundance of wetlands and wa-tercourses. La Calzadilla is described in Spanish terminology as“campo de hoyos” (i.e. a pit settlement), which generates a hori-zontal sequence as a result. Several pottery sherds point towardssome activity during the Neolithic, but the pit settlement wasincreasingly frequented by human groups throughout the CopperAge, Bronze Age and Iron Age. In the fourth century AD, a Romanvilla was built here and damaged part of the prehistoric settlement.

Over the last few decades, the excavations of the villa haveunearthed archaeological items dating back to Late Prehistory, butthese assemblages lacked specific information about their contexts(Balado, 1989). The construction of a visitor centre to the south-west of the villa, however, revealed over seventy preserved pre-historic pit features. One of these pits, of common type and di-mensions, provided an interesting collection of artefacts and faunal

von Lettow-Vorbeck), elisa.. Delibes de Castro).

nd INQUA. All rights reserved.

remains (Fig. 1.2e3). As the study of the pottery and the contentshave been previously published (Delibes and Guerra, 2004; Guerra,2006), we will focus here on a detailed taphonomic study of thefaunal remains, which also emphasises the special characteristics ofthis deposit.

2. Materials and methods

The pit examined here is structurally identical to the otherprehistoric pits found at this particular campo de hoyos. Theiroriginal number is not known. Cut into the natural sandy soil, theywere of varying depths and roughly oval in shape. In some cases,they seem to have been left open or have been reused, since thefindings recovered fromwithin correspond to different periods. Thepit of study has depth of around one meter and a similar diameter.Its fill produced a number of artefacts that were deliberatelyselected, in association with two complete human ribs found at thebottom. All the excavated sediment from the pit underwent drysieving in a 5 mm mesh.

The artefacts within the pit consist of a fragment of a stone axe,three bone objects (a bevelled tool, one awl and one needle or pin),three hand grinders, a reduced assemblage of flint items (onescraper, one blade, one sickle, two flakes and two knifes), and manypottery sherds and a small faunal assemblage (Fig. 2).

The identified faunal remains correspond to eight species ofmammals (cattle, aurochs, pig, ovicaprine, sheep, dog, hare andrabbit) with a total NISP of 103. The identification of the faunal

Fig. 1. 1. Map showing the location of Almenara de Adaja. 2. The Bell Beaker pit before excavation. 3. The Bell Beaker pit after excavation.

Table 1NISP, Weight and NMI of the species recovered in the pit.

Species NISP NISP % Weight(gr)

Weight % Weight %(withoutaurochs)

MNI

Cattle (Bos taurus, L.) 8 8.2 164 32.5 48.0 1Sheep (Ovis aries, L.) 2 2.1 6 1.2 1.8 1Ovicaprine (Ovis aries,

L.; Capra hircus, L.)21 21.6 50 9.9 14.6 1

Pig (Sus sp.) 26 26.8 96 19.0 28.1 4Dog (Canis familiaris, L.) 1 1.0 2 0.4 0.6 1Aurochs

(Bos primigenius, Boj.)1 1.0 162 32.1 0.0 1

Hare (Lepus, granatensis,Rosenhauer 1856 )

4 4.1 12 2.4 3.5 2

Rabbit (Oryctulaguscuniculus, L.)

34 35.1 12 2.4 3.5 3

Total mammals 97 100 504 100 100Bird (Pica pica, L.) 1 1Mollusk

(Unio/Anodonta)5

Unidentified 91 117 19Total 194 621 100 15

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e96 89

remains wasmade using as a reference the collection of Prof. ArturoMorales (LAZ-UAM) and our study follows the criteria proposed inboth Morales and Liesau (1995) and Liesau (1998). The identifica-tion of the hare remains (Lepus granatensis, Rosenhauer 1856) fol-lows the criteria discussed by Llorente (2010). The agedetermination of the pig foetal bones was done with the work ofHabermehl (1975) in mind. The taphonomic study was carried outin accordance with the so-called “taphonomic groups” defined byGautier (1987: 48e49), a useful, operational method for groupingthe animal bones in different categories that should be consideredand studied separately: consumption refuse, workshop/manufac-ture refuse, remains of carcasses, penecontemporaneous intrusives(animals that lived and died shortly before, during or after itsoccupation, brought in by predators, river transport, etc.). The fifthgroup includes the so-called reworked intrusives, such as fossilsfrom deposits underlying the site, reworked by human activity,fluviatile erosion etc. Finally, the late intrusives include remainsadded to the site much later, such as micromammals, or thoseadded due to human activity by digging pits. Most of these groupscould be identified in this assemblage and their determinationhelps us to explain the taphonomic processes that have taken placeand, in several cases, the origin of each bone. For the study of thepreservation stage of the bone surfaces, the taphonomical stages ofBehrensmeyer (1987) were used. The characterisation of the bonetools, which have not been included in Table 1, follows the criteria

proposed in Rodanés (1987) and Maicas (2007). According toGautier (1987), these tools must be considered as manufactured, asit is impossible to know whether they came from previouslyconsumed animals or were brought from another site or context.

Fig. 2. A selection of the archaeological items found in the pit. On top, bone and lithic tools, and pottery sherds below.

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e9690

3. Results

3.1. The archaeological record

The ceramic assemblage is very fragmented and includes largevessels and a significant number of bowls. While plain typesdominate the collection, some sherds display painted lines and onefragment is decorated with fingernail impressions. It is importantto note that a large selection of different types of Beaker potterywas deposited in the pit. The Beaker pottery found corresponds tothe Ciempozuelos-style, one of the late regional variants in Iberia,which is defined by incised and impressed decoration. However,Beaker sherds with comb-impressed decoration (Puntillado geo-métrico style) have also been recovered (Fig. 3). Fragments of pot-tery originating from the same vessel were recovered at differentdepths in the fill of the pit, strongly indicating that it was filled inone event. In some cases, the decorationwas incrustedwith awhitepaste, either made of calcium carbonate or biogenic apatite(crushed bones) (Odriozola et al., 2012). The three distinctiveshapes of the Ciempozuelos pottery have been identified: BellBeakers, shouldered bowls and hemispheric bowls. The latter wereprobably intentionally smashed as a number of perfect halves thathave sharp edges with fairly fresh breaks suggest their rapid in-clusion into the pit. One of these Ciempozuelos bowls is quiteexceptional, since it falls into the Symbolkeramik group, i.e. potterywhich displays motifs similar to those in open-air sites withSchematic Art, also present in some objects that have consequentlybeen considered idols. Beaker pottery with this kind of decoration

is quite unusual in Iberia, with less than thirty examples reported(Garrido and Muñoz, 2000). Amongst the most frequent motifs,such as suns, eyes, or male deer, the bowl from La Calzadilla depictsthree deer with exaggerated antlers (Delibes and Guerra, 2004)(Fig. 3, see a reconstruction in the box). No other pit at the site hascontained such a significant amount of Beaker pottery, nor Sym-bolkeramik vessels.

Residue analyses conducted on one of the hemispheric bowlshave detected traces of cereal grains with evidence of enzymaticattack, highly suggestive of beer. Cerotic acid was also found,although it is difficult to ascertain whether this bowl containedmead or beeswax, as well as beer (Guerra, 2006). A sample of woodcharcoal from the bottom of the pit was radiocarbon dated to be-tween 2345 and 1883 cal BC (3700 � 80 BP, GrN-27817). Radio-carbon dates have been calibrated using the IntCal09 curve and theOxCal v.4.2.2 programme at two standard deviations.

3.2. The archaeozoological record

Although the 103 remains identified are too scarce to inferreliable facts regarding livestock and hunting strategies, the pro-portion of the remains in the NISP and weight seem to indicate thatthe main providers of meat are cattle, ovicaprines and pigs. Thesespecies frequently appear at Iberian chalcolithic sites (Driesch,1972; Peters and Driesch, 1990; Morales and Liesau, 1994; Liesau,2011a). Wild species play a minor role in the consumptionpattern (Table 1). The only accidental remains seem to be a frag-ment of jackdaw humerus and a few of fresh water mollusc shells;

Fig. 3. Beaker pottery from the pit. In the box, a reconstruction of the bowl with symbolic decoration and a picture of one of the deer.

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e96 91

their scarcity makes it difficult to interpret them as kitchen refuse.However, these remains provide environmental information on thesite in prehistoric times.

The pig bones unearthed are of particular interest. According tothe criteria set out by Habermehl (1975: 140), based on osteometricdata from long bones at various stages of gestation, two of the fourindividuals identified represent a foetal stage rather than neonatal.In any case, this clearly indicates good preservation conditions forthe bone assemblage. The bones show a great disparity of size, anduneven growth is not unusual amongst members of the same litter.The smaller specimen could be derived from the runt member ofthe litter, which, during pregnancy, could have developed at thebottom of uterus where the blood flow from mother was lower,thus affecting its growth. However, the difference is so marked thatit might be indicative of two litters and this would therefore implythat several complete or partial foetuses at different stages ofpregnancy were introduced into the pit. Consequently, two preg-nant sows must have been slaughtered (Fig. 4).

Another exceptional finding is the aurochs bone. This wildspecies is neither common nor well-documented at Iberian chal-colithic sites, although this is also due to the difficulties in theoverlapping size and features of cows, heifers and calves (Driesch,1972). In Table 1 we include another column without the aurochsbone, since the bone’s different characteristics reveal no primaryconsumption (see Section 3.3).

Likewise, the skeletal representation of the main species sug-gests an intentional selection of body parts (Appendix, Table 1). Thefact that cranial elements are underrepresented (15.5% in NISP), theappendicular skeleton reveals habitual values for prehistoric sites(53.6% in NISP), and there is a high proportion for the axial skeleton,with a value of 25% for ribs (which are not complete, but well-preserved) is remarkable (Fig. 6.1e2). This result indicates thatthe main consumed forms of livestock were cattle, ovicaprine andpigs. With regards to the human remains present in this assem-blage, only two complete ribs were found.

3.3. A taphonomic analysis of the faunal assemblage

In terms of our taphonomic study of the remains, although thebone surfaces are well-preserved, only 53% (NISP ¼ 103) could beidentified due to the high degree of predepositional fragmentation.Many pieces are small splinters and only achieved a mean value of1.3 g per piece (Table 1). Moreover, 20% of the bones reveal marksinflicted by several agents and suggest different origins before theywere added to the pit. This stands in sharp contrast to the potteryassemblage, all dating to the Beaker period. In the light of the evi-dence,wehaveopted todeduce that thepitwasfilled inonegoduringthe Beaker period. At that particularmoment in time, all the artefactswere deposited within the pit along with the bone remains, some ofwhich might have already been in the soil when the pit was dug.

Fig. 4. Pig foetal bones of at least two possible litters recovered from the pit. 1. Left scapula, lateral view. 2. Right scapula, lateral view. 3 and 4. Left humeri, caudal view. Number 1, 2and 3 probably belong to the same individual. According to Habermehl (1975: 140), the Maximum Length of the humerus number 4 is indicative of a foetal evolution of 96e100 daysof pregnancy while number 3 corresponds to a foetus of 71e75 days of gestation.

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e9692

In accordance with the different taphonomic groups establishedby Gautier (1987), most of the unidentified bones and the mainsample of identified bones probably fall into the first group definedas consumption refuse, where anthropic actions causing cut andchop marks reveal leftovers from meals, especially de-fleshingmarks on ovicaprine ribs and extraction of the tongue (hyoids)(Fig. 6.1e4). Burnt surfaces on the distal ends of the appendicularbones were also frequent on hares and rabbits (humerus, distaltibia, calcaneus and metapodials) (Fig. 6.6), indicating their prep-aration by grilling, as is also the case with one large bovine rib.

A second taphonomic group, not included in Table 1, is a smallassemblage of three manufactured bones recovered from the pit.Firstly, a bevelled artefact, made from a big ruminant rib with apolished surface on the lateral and ventral side, was probably usedas a spatula/smoothing tool (Fig. 2.1). The second tool, probablymade from a long bone diaphysis of a large mammal, is moreelaborated and has a rounded base. The entire artefact surfaceshows an intensive polish. It may well have been discarded due anold fracture on the pointed end (Fig. 2.2). The third item is madefrom a pig fibulawith evidence of slight polish. It has a long pointedend but we cannot make out whether it was a pin or a needle as thedistal end is fractured (Fig. 2.3).

Many unidentified bone splinters could correspond to the fourthgroup, the penecontemporaneous intrusives, i.e. a secondary refusethat got into the fill from the surrounding sediment, mixed withrubbish from the settlement. Several marks caused by biologicalagents, like carnivore gnawing and digested bones, affected 7% ofthe bones (appendicular bones of pigs, ovicaprine and rabbit) andalmost 2% of the bones had been attacked by rodents (Figs. 5 and 7).

The basioccipital bone from the aurochs reveals completelydifferent features than the rest of the bone assemblage (Fig. 8). Thesurface is deeply altered and eroded, presenting fissures andcracking marks on the occipital condyles and the muscular tuber-cles, but not in the inner side of the bone. These taphonomic

modifications are indicative of prolonged exposure to climaticagents, so the skull was quite possibly more complete originally.Only part of the skull was deposited in the pit, otherwise thealteration would also affect its inner side. It is difficult to applyseveral of the weathering stages described by Behrensmeyer(1978:151) to this cranial bone, but it might fall into Stage 2e3. Ifwe consider the taphonomic groups of Gautier, this bone could beinitially classified in the fifth category, a reworked intrusive, i.e. afossil from deposits underlying the site reworked in the site byhuman activities or brought in by other agents (Gautier, 1987, 49).The bone of the aurochs was dated and yielded a result of between2459 and 2204 cal BC (3845 � 35 BP, Poz-43076).

4. Discussion

Independently of the faunal remains recovered from other pitson the site (which, unfortunately, have not yet been studied indetail), the ones deposited in this Beaker pit are quite distinctivesince their taphonomic study has revealed different predeposi-tional origins. The taphonomical grouping was useful for obtainingexhaustive information for the interpretation of the faunal remains.Taking into account the different taphonomic groups, we have beenable to discriminate primary and intentional consumption refuserelated to the deposition act from other remains, such as thosealtered by carnivores, digested bones from unfossilised coprolites,rodent teeth marks or root marks, which would not have beenintentionally included when the pit was filled with sediment.

The generally well-preserved bone assemblage, revealing an-thropic alterations for preparation or de-fleshing actions allows usto conclude that the main sample corresponds to consumptionrefuse. This is also evident from the high figures of the axial por-tions (30.9%). These selected skeletal elements, especially ribs fromdifferent species, are traditionally most appreciated for consump-tion. Other distinctive findings include the hyoids, which are fairly

Fig. 5. Graph representing the animal bones with weathering marks, biologic agents and anthropic marks documented on the faunal remains recovered of the pit.

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e96 93

unusual at archaeological sites and their cut marks reveal manip-ulation of the tongue.

If the preservation of some foetal bones is exceptional in itself,the remains at La Calzadilla are even more extraordinary since theyrepresent the sacrifice or hunting of pregnant pigs or wild boars.The symbolism of pig sacrifice is known at other Bronze Age Sites,such as La Loma del Lomo (Guadalajara), where several pigs werefound in ritual and funerary contexts (Valiente, 1992). However,these deposits usually include complete specimens related either tofertility rites or human burials (Valiente, 1993). Here, we aredealing with a more complex situation. We are unaware of theattitudes that prehistoric communities had towards foetuses, whena pregnant femalewas slaughtered or hunted. The scarce number ofpig foetal bones could be due either to the lesser ossification

Fig. 6. Selection of different taphonomic marks on the bone sample. 1e2. Rib fragments of ovwith cut marks on their caudal angle. 5. Right calcaneus and tibia of a rabbit, cranial view. 6.in cranial view.

process of these skeletons, taphonomic loss, or the sieving tech-nique employed. In any case, this small sample could not corre-spond to common consumption refuse, but possibly to the thirdtaphonomic group, the remains of more or less complete carcasses.

The remains of dog and jackdaw, and the few molluscs could beassigned to penecontemporaneous intrusives (fourth group)because of their scarcity and small size. The three bone artefacts donot imply necessarily previous consumption in the site and couldbe grouped in the manufacture refuse (second group), as two ofthem are incomplete and reveal old fractures.

The aurochs skull fragment is another example of this deposit’ssingularity. Considering the location of basioccipital region in theskull, which is protected when in upright position, the features onthe bone suggest that the basioccipital came from a more or less

icaprine with several cut marks, ventral view. 3 and 4. Hyoid (stilohioidea) of ovicaprineRight calcaneus and Tibia of a hare with burnt surfaces. Calcaneus in plantar view, tibia

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e9694

complete skull of an aurochs, suffering long exposure as indicatedby the weathering modifications of the external surface of bone.Although Behrensmeyer (1978) and, more recently, Madgwick andMulville (2012) remarked on how difficult it is establish clearweathering patterns for archaeological samples, cracking and sur-face alterations are only present on this remain from the pit, thusindicating its antique origin. The radiocarbon date of the woodcharcoal has a range between 2345 and 1883 cal BC, whilst thesample of the aurochs bone yielded a result of between 2459 and2204 cal BC. Not only is the charcoal sample more recent than thebone sample, but it could also be younger considering the old woodeffect. Therefore, the aurochs might have been several hundredyears oldwhen it was incorporated into the pit. As a result, it cannotbe classified into the conventional category of a reworked intrusive.This bone was most probably the final remain of a skull and couldserve as a token.

Aurochs remains are not frequently registered in Iberian pre-historic sites, but in some cases it seems that the skulls receivedspecial treatment. In the chalcolithic ditched enclosure of Caminode Las Yeseras (Madrid), two skulls were discovered in pits: a largemale aurochs cranium, demonstrating long exposure before the pitwas filled in, and a second skull associated with a bone assemblage,the horns of which were painted with ochre (Liesau et al., 2008;Liesau, 2011b).

Independently of the circumstances of the settlement, strate-gically placed next to the entrances of the ditches, or to funerarycontexts, the collection or exhibition of cattle and aurochs skulls isnot an isolated phenomenon and is frequently documented as it isin British sites (Davis and Payne, 1993; Towers et al., 2010). In thespectacular findings of the Barrow 1 at Irthlingborough in central-southern England, the skulls and other bones of 185 animals have

Fig. 7. Selection of bones with carnivore gnawing and digestion marks. 1 and 2.Digested rabbit bones. 1. Tibia proximal, cranial view. 2. Femur distal, plantar view. 3.Digested astragalus from ovicaprine, plantar view. 4. Scapula fragment of ovicaprinecovered by gnawing marks, medial view.

also led to an interesting discussion about the consumption of thecattle at the site and the accumulation of other skulls as tokens.Besides, radiocarbon dating suggests that some of the aurochsbones were several hundred years older than the context of thebarrow (Davis and Payne, 1993). Another interesting Early BronzeAge tomb is at Gayhurst, where in a ring-ditch surrounding Barrow2 the limb bones of at least 300 animals were uncovered. RecentStrontium isotope analysis carried out on the teeth found at Irth-lingborough and Gayhurst reveal interesting results regarding thelocal origin of the sacrificed cattle and also others coming fromlong-distance exchange networks, revealing the important rolethey had in recent Prehistory (Towers et al., 2010).

The presence of so much Beaker pottery in the pit at La Calza-dilla, including perfect halves of five bowls (one of them withsymbolic motifs), therefore suggests an unusual filling of the pit.The rest of the findings, interesting in their variety (one stone axe,three hand grinders, some flint items, several bone implements,possibly discarded?), and the atypical animal remains cannot beinterpreted as a simple refuse deposit, but as the result of an eventthat involved the manipulation of human bones, evidenced by thetwo ribs found at the bottom of the pit. Whilst we cannot be surewhether the human ribs were intentionally deposited within thepit (a cenotaph?) or they were amongst the secondary refuse thatwas thrown there, it seems clear that both artefacts and faunalassemblage point towards a “ritual” ceremony.

Fig. 8. Fragment of basioccipital bone from an aurochs with characteristic weatheringmarks caused by long exposure. Fissures and cracking marks are present only onexternal surface, basal view.

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e96 95

The term “ritual” and its significance for prehistoric societieshave been discussed by several authors. Brück (1999, 328)emphasised that “culture” is not a uniform entity and cannotbe simply polarised into ritual and non-ritual categories. Bradley(2005), on the other hand, remarked upon the difficulties of differ-entiating between ritual and domestic life in prehistoric Archae-ology. When it comes to faunal deposits, terms such as “ritual”,“special deposits”, “structural depositions” or more aseptically“associated animal bone groups”, have been used to refer to com-plete or partial articulated animal depositions (Hill, 1995). Recentstudies draw attention to the need for amore exhaustive contextualstudy of these deposits, their associations and their taphonomichistory (Morris, 2011, 2012).

At La Calzadilla, the residue analysis carried out on Beakersherds and the bone assemblage point towards the consumption offermented beverages and portions of special kinds of meat. Alcoholwould have been distributed in Beaker pottery which was inten-tionally smashed at the end, even the singular bowl with symbolicmotifs, in order to prevent the profanation of the vessels or toannounce the end of the ceremony (Delibes and Guerra, 2004). Notonly was this exceptional pottery included in the pit, but also apeculiar aurochs bone, probably kept as an ancestrial symbol anddefinitively buried during the course of the ceremony.

5. Conclusion

The late Copper Age occupation of La Calzadilla corresponds to a“pit settlement”. The excavation of one of these pits has provided aninteresting archaeological record that questions its proposed func-tion as a dump. It contained, amongst other items, an exceptional

Appendix

Table 1Bone collection according skeletal categories of the identified species.

Species La Calzadilla-Pit 2000/4/201

Cattle Sheep Sheep/Goat Pig D

Skull 1 3Upper teeth 1Mandible 2Lower teeth 1 1Hyoid 2Cranial skeleton 0 0 6 5 0Thoracic vert. 1Lumbar vert.Sacral vert.Rib 8 7 8Axial skeleton 8 0 7 9 0Scapula 3Humerus 1 3Radius 1UlnaCarpalsMetapodialPelvisFemur 1 1 1Tibia 2 1Astragalus 1 1Calcaneus 2Centroquartal 1Metatarsal 3Phalanx 2 1Appendicular skeleton 0 2 8 12 1Stylopodium 0 0 2 4 1Zygopodium 0 0 2 2 0Autopodium 0 2 4 3 0Total 8 1 21 26 1Weight (g) 194 6 50 96 2

collection of Bell Beaker Ciempozuelos-style vessels, including onewith symbolic decoration, and a singular assemblage of faunal re-mains, of species both domestic and wild. The ages and skeletalportions, with a high proportion of ribs (two complete human ribswere also included), lead us to interpret this context as a ceremonyof ritual character related to the manipulation of human bones. Theritual may have also involved the consumption of alcoholic bever-ages, as is indicated by the results drawn from the analysis of theresidues in one of the Bell Beaker bowls. According to the datingevidence, this must have happened at the end of the 3rd/beginningof the 2nd millennium cal BC. The separate study of taphonomicmodifications of the faunal remains demonstrated different origins.The taphonomic modifications documented for the aurochs bonereveal it as not a contemporaneous consumption refuse, furtherdemonstrated by radiocarbon dating, but probably a singular itemwith a symbolic value for several generations.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper was carried out withinresearch projects HAR 2009-10105 and HAR 2011-28731 (PlanNacional IþDþi, Ministerio de Economía y Competividad, Spain).We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Paloma García-Fer-nández from the School of Veterinary Medicine (UCM Madrid) forher information on the possibility of size differences within thesame litter during the pregnancy of a sow. This paper was pre-sented at the II Taphonomy Working Group meeting held inSantander (Spain) in September 2012 and organised by A.B. Marín-Arroyo and M. Moreno-García.

og Aurochs Hare Rabbit Bird Total %

1 1 6 6.21 1.0

2 4 4.12 2.12 2.1

1 0 3 0 15 15.51 1.0

4 4 4.11 1 1.01 24 24.7

0 0 6 0 30 30.93 6 6.2

1 1 1 6 6.21 2 2.12 3 2.11 1 1.0

1 1 1.05 5 5.23 6 6.2

1 5 9 9.32 2.1

1 3 6 6.21 1.0

1 4 4.11 1.0

0 4 25 1 52 53.60 1 4 1 12 12.40 1 9 0 14 13.40 2 4 0 15 16.51 4 33 1 97 100

162 12 30 1 587

C. Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. / Quaternary International 330 (2014) 88e9696

References

Balado Pachón, A., 1989. Excavaciones en Almenara de Adaja: El poblamiento pre-histórico. Diputación Provincial de Valladolid, Valladolid.

Behrensmeyer, 1978. Taphonomic and ecological information from bone weath-ering. Paleobiology 4 (2), 150e162.

Bradley, R., 2005. Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe. Routledge, London.Brück, J., 1999. Ritual and rationality: some problems of interpretation in European

Archaeology. Journal of European Archaeology 2 (3), 313e344.Davis, S., Payne, S., 1993. A barrow full of cattle skulls. Antiquity 67, 12e22.Delibes de Castro, G., Guerra Doce, E., 2004. Contexto y posible significado de un

cuenco Ciempozuelos con decoración simbólica de ciervos hallado en Almenarade Adaja (Valladolid). In: Baquedano Pérez, E., Rubio Jara, S. (Eds.), Misceláneaen Homenaje a Emiliano Aguirre, Arqueología, vol. IV. Museo ArqueológicoRegional, Alcalá de Henares, pp. 116e125.

Driesch von den, A., 1972. Osteoarchäologische Untersuchungen auf der IberischenHalbinsel. Studien über frühe Tierknochenfunde von der Iberischen Halbinsel,3.

Garrido Pena, R., Muñoz López-Astilleros, K., 2000. Visiones sagradas para loslíderes. Cerámicas campaniformes con decoración simbólica en la PenínsulaIbérica. Complutum 11, 285e300.

Gautier, A., 1987. Taphonomic groups: how and why? Archaeozoologia 1 (2), 47e51.Guerra Doce, E., 2006. Sobre la función y el significado de la cerámica campani-

forme a la luz de los análisis de contenidos. Trabajos de Prehistoria 63 (1), 69e84.

Habermehl, K.H., 1975. Die Altersbestimmung bei Haus-und Labortieren. Paul Parey,Hamburg.

Hill, J.D., 1995. Ritual and Rubbish in the Iron Age of Wessex. British ArchaeologicalReports, British Series, vol. 242. Oxford.

Liesau, C., 1998. El Soto de Medinilla: Faunas de mamíferos de la Edad del Hierro enel valle Medio del Duero (Valladolid, España). Archaeofauna 7, 7e210.

Liesau, C., 2011a. Los restos de mamíferos del ámbito doméstico y funerario. In:Blasco, C., Liesau, C., Ríos, P. (Eds.), Yacimientos calcolíticos con campaniformede la región de Madrid: Nuevos estudios, Patrimonio Arqueológico de Madrid,vol. 6, pp. 171e189.

Liesau, C., 2011b. La Arqueozoología, un elemento clave en la concepción espacial deCamino de las Yeseras. Los restos de mamíferos del ámbito doméstico yfunerario. In: Blasco, C., Liesau, C., Ríos, P. (Eds.), Yacimientos calcolíticos concampaniforme de la región de Madrid: Nuevos estudios, Patrimonio Arqueo-lógico de Madrid, vol. 6, pp. 167e170.

Liesau, C., Blasco, C., Ríos, P., Vega, J., Menduiña, R., Blanco, J.F., Baena, J., Herrera, T.,Petri, A., Gómez, J.L., 2008. Un espacio compartido por vivos y muertos: el

poblado calcolítico de fosos de Camino de las Yeseras. Complutum 19 (1), 97e120.

Llorente, L., 2010. The Hares from Cova Fosca (Castellón, Spain). Archaeofauna 19,59e97.

Madgwick, R., Mulville, J., 2012. Investigating variation in the prevalence ofweathering in Faunal assemblages in the UK: a multivariate statistical approach.International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 22, 509e522.

Maicas, R., 2007. Industria ósea y funcionalidad: Neolítico y Calcolítico en la Cuencadel Vera (Almería). Bibliotheca Praehistorica Hispana. Publicaciones del ConsejoSuperior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid.

Morales, A., Liesau, C., 1994. Arqueozoología del Calcolítico en Madrid: Ensayocrítico de síntesis. In: Blasco, C. (Ed.), El Horizonte Campaniforme de la regiónde Madrid en el centenario de Ciempozuelos, Patrimonio Arqueológico del BajoManzanares, vol. 2. Depto. de Prehistoria y Arqueología UAM, pp. 227e247.

Morales,A., Liesau, C.,1995. Análisis comparadode las faunas arqueológicas enel vallemedio del Duero (prov. Valladolid) durante la Edad del Hierro. In: Delibes, G.,Romero, F., Morales, A. (Eds.), Arqueología y Medio Ambiente: El Primer Milenioa.C. en el Duero Medio. Junta de Castilla y León, Valladolid, pp. 455e514.

Morris, J., 2011. Investigating animal burials: ritual, mundane and beyond. In:British Archaeological Reports, British Series, vol. 535. Oxford.

Morris, J., 2012. Animal “ritual” killing; from remains to meanings. In:Pluskowski, A. (Ed.), The Ritual Killing and Burial of Animals. European Per-spectives. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 8e21.

Odriozola, C., Hurtado, V., Guerra Doce, E., Cruz-Auñón, R., Delibes de Castro, G.,2012. Los rellenos de pasta blanca en cerámicas campaniformes y su utilizaciónen la definición de límites sociales. Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras 19, 143e154. Actas do IX Congresso Ibérico de Arqueometria (Lisboa, 2011).

Peters, J., von den Driesch, A., 1990. Archäozoologische Untersuchungen der Tier-reste aus der Kupferzeitlichen Siedlung von Los Millares (Prov. Almería).Studien über frühe Tierknochenfunde von der Iberischen Halbinsel 12, 51e109.

Rodanés Vicente, J.M., 1987. La Industria ósea prehistórica en el valle del Ebro.Neolítico-Edad del Bronce. Colección Arqueología y Paleontología 4. SerieArqueología Aragonesa, Zaragoza.

Towers, J., Montgomery, J., Evans, J., Jay, M., Pearson, M.P., 2010. An investigation ofthe origins of cattle and aurochs deposited in the Early Bronze Age barrows atGayhurst and Irthlingborough. Journal of Archaeological Science 37, 508e515.

Valiente, J., 1992. La Loma del Lomo II. Cogolludo (Guadalajara). Servicio de Pub-licaciones de la Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha, Toledo.

Valiente, J., 1993. Un rito de fertilidad agraria de la Edad del Bronce en la Loma delLomo (Cogolludo, Guadalajara). In: Homenaje a José María Blázquez, vol. I.Ediciones Clásicas, Madrid, pp. 253e265.