CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE SYSTEM: A CASE STUDY OF...

Transcript of CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE SYSTEM: A CASE STUDY OF...

148 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE SYSTEM:

A CASE STUDY OF JANANI SURAKSHA YOJANA SCHEME*

Nidhi S Sabharwal, Sandeep Sharma, Dilip Diwakar G and Ajaya K Naik**

The Government of India initiated a scheme called the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) in 2005 under its National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) with the aim of accelerating the reduction in the Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR). The scheme aims to reduce the maternal and newborn mortality rate through the promotion of institutional delivery, for which financial incentives are provided to mothers who deliver in a healthcare facility (MoHFW, 2006). It is a fully Centrally-funded scheme, which integrates cash assistance with ante-natal care during the pregnancy period, as well as with institutional care during delivery as also post delivery and post-natal care. This is provided by field level health workers through a system of coordinated care and health centres. Under the JSY, the scale of cash assistance for institutional delivery for states varies according to their performance in institutional delivery. The states are classified as low-performing and high-performing states in terms of institutional delivery if their performance is respectively lower or higher than the national average. In the low-performing states, the cash assistance offered for rural areas is Rs. 1400 plus transport charges (which are decided by the state, but are not less than Rs. 250) and the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) gets a transactional cost of Rs. 600 for each institutional delivery. For the urban areas, the corresponding cash assistance is Rs. 1000 plus transport charges (which are also decided by the state, but are not less than Rs. 250) and the ASHA gets a transactional cost of Rs. 200 for each institutional delivery. In the high-performing states, the cash assistance offered in the rural areas is Rs. 700 while the corresponding amount in the urban areas is Rs. 600 (MoHFW, 2006).

All women belonging to the Below the Poverty Line (BPL) category, Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in all the states and Union Territories (UTs) would be eligible for JSY benefits if they have given birth in a government or private accredited health facility. In the case of BPL women, they can get JSY benefits even if they prefer to deliver at home. However, earlier in the high-performance states, the criteria of age

** Nidhi Sadana Sabharwal ([email protected]), Sandeep Sharma ([email protected]), Dilip Diwakar ([email protected]) and Ajaya Kumar Naik ([email protected]) are with the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies (IIDS), New Delhi.

Journal of Social Inclusion Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2014

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 149

and the number of children were prevalent, which has been removed recently to further accelerate the incidence of institutional delivery and reduce maternal and infant mortality (Dhar, 2013).

The Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) plays an important role along with other link health workers to provide services associated with JSY. The ASHA’s role is to identify pregnant women as beneficiaries for the scheme and to report or facilitate their registration for ante-natal care (ANC); to assist them in obtaining the necessary certifications, wherever necessary; to provide and/or help women receive at least three ANC check-ups including tetanus (TT) injections and iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets; to identify a functional government health centre or an accredited private health institution for referral and delivery; to counsel them for institutional delivery; and to escort beneficiary women to their respective pre-determined health centres and stay with them till they are discharged. During the post-natal stage, the ASHA arranges for the immunisation of the newborn till the age of 14 weeks; informs about the birth or death of the child or mother to the auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM)/Medical Officer (MO); undertakes a post-natal visit within seven days of delivery to track the mother’s health after delivery; facilitates care, wherever necessary; counsels for initiation of breastfeeding to the newborn within one hour of delivery and its continuance till 3-6 months; and promotes family planning among the targeted women (MoHFW, 2006).

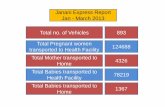

The scheme has expanded in scale since its introduction. The number of beneficiaries under the JSY in India increased from 7.34 lakhs in 2005-06 to 113.39 lakhs in 2010-11. The number of institutional deliveries under JSY also increased from 108 lakhs in 2005-06 to 168 lakhs in 2010-11 (MoHFW, 2011).

This paper examines the access and utilisation of JSY in seven states at the overall level as also separately for the SCs and high castes, identifies both the general factors that hinder or facilitate access to the scheme for all the beneficiaries, and the factors that are specific to the low castes in the utilisation of the health services (with particular emphasis on caste discrimination in terms of accessing the health services), and in the end, enlists all the possible measures to combat this discrimination.

The study was carried out between 2011 and 2013 in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar, covering 112 villages. About 963 respondents/households, including 664 SCs (comprising 69 per cent of the total) and 299 higher castes (comprising 31 per cent), which includes both Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and upper castes from the rural areas were studied during the study. The respondents for the JSY scheme include currently pregnant women, lactating mothers, and mothers who gave birth during the last five years.

Besides the quantitative data, the information was also gathered through focus group discussions (FGDs), including 43 for the SCs and 1 for the higher castes, and case studies, including about 18 for the SCs. The indicators that capture the access to and utilisation of

150 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

the scheme include institutional delivery amongst the JSY card-holders, utilisation of ante-natal care (ANC), the amount spent in giving birth in a hospital, the time taken to receive cash assistance, post-natal care (PNC), and service providers for the JSY.

1. UTILISATION OF HEALTH SERVICES

The utilisation of health services in terms of institutional delivery was found to be high, as 85 per cent of the mothers who had registered with JSY delivered in a government healthcare facility, 65 per cent of the mothers received ante-natal care, and 76 per cent received post-natal care. On an average, women received Rs. 1263 per head in cash assistance for delivery in the hospital. However, the SC mothers were found to be lagging behind in the use of these services to varying degrees and disparities were prevalent in all the spheres between the SC women and their high-caste counterparts. About 83 per cent of the SC women had had a delivery at the hospital, a figure that is somewhat less as compared to the corresponding figure of 90 per cent for the higher caste women.

Table 1: JSY Card-holders: Delivery at Home or in the Hospital for Ensuring Safe Delivery (in per cent)

Place of Delivery SCs Higher Castes

Average

Proportion of women holding JSY cards who delivered in the hospital 83.06 89.95 85.31

Proportion of women holding JSY cards who delivered at home 11.83 6.7 10.16

Proportion of women without JSY cards who delivered in the hospital 1.39 1.44 1.41

Proportion of women without JSY cards who delivered at home 3.71 1.91 3.13

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

1.1 Ante-natal Care and House Visits

A majority of the women (65 per cent) registered with the JSY received ante-natal care. However, the ANC ratio was 63 per cent for SC women as compared to 70 per cent for the higher caste women.

The guidelines for the scheme specify a minimum of three visits to each of the beneficiaries of the scheme. During the course of the study, about 65 per cent of the women reported visits by the service providers in varying numbers, which means that the remaining 35 per cent of the households were not visited by the service providers. As against the norms of three visits, 44 per cent of the visits were made 1-2 times, and only 21 per cent households were visited three times. Thus, 79 per cent of the households did not receive home visits as per the prescribed norms.

In the case of the SC women, the ratio of the visits was already low (at 65 per cent) as compared to that for the higher caste (70 per cent). Further, the proportion of houses that were not visited at all was higher in the case of the SCs (36 per cent) than the higher

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 151

castes (31 per cent). There was less difference in the prescribed minimum limit of three visits. The proportion of 1-2 visits was 22 per cent for the SC women and 27 per cent for their higher caste counterparts. Thus, SC households were not only visited fewer times than the higher caste ones, but they also had fewer visits overall by the service providers than the prescribed minimum norms of three visits.

Table 2: Number of ANC Visits (in per cent)

No. of Visits SCs Higher Castes Average

One visit 20.1 21.7 20.6

Two visits 21.6 27.4 23.5

Three visits 21.8 19.6 21.1

No visit 36.5 31.3 34.8

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

As regards the cash assistance, on an average, the women spent Rs. 2734 for each birth that took place in a hospital. The mothers, on an average, received Rs. 1263 in cash assistance, which was lower than the amount spent. Thus, the average gap between the cash spent and cash received at the aggregate level was Rs. 1471. On an average, the gap between cash spent and cash received was wider for the SC mothers (Rs. 1555) than for the higher caste mothers (Rs. 1309). The average amount of money spent by the SC mothers was also higher by Rs. 318 than that spent by the higher caste mothers. The following extracts throw light on the differential treatment meted out the pregnant SC women under the JSY:

“Sometimes we have to go to a government hospital which is quite far and for that we have to arrange a vehicle. We have to spend up to Rs. 1000 for the vehicle. The nurses do not take care of us properly. Often they have to be called from the staff quarters as they are not available all the time in the hospital premises.” (SC, Women FGD, FGD No. 52,211, Village No.13, West Singhbhum, Jharkhand, 2012)

“We have to pay for a delivery in the hospital. ASHAs demand money to get the delivery done.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 21,221, Village No. 06, Muzaffarpur, Bihar, 2012)

“During the delivery, they take the pregnant lady to the hospital but the nurses ask for money and costly soap.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 61,241, Village No. 08, Khandamal, Odisha, 2012).

152 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

Table 3: Money Received and Money Spent for the Delivery (in per cent)

SCs Higher Castes

Average

Average Money Spent on a Delivery per Woman 2842 2524 2734

Percentage of those who spent money by range of money

Up to Rs. 1000 40.3 37.5 39.3

Rs. 1001 to 5000 53.2 53.1 53.2

Rs. 5001 to 10,000 4.3 6.8 5.2

Rs. 10,001 to 50,000 2.2 2.6 2.3

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Average cash received per woman under the JSY 1287 1215 1263

Percentage of Those Who Received Cash by the Range of Cash Received

Less than Rs. 1400 15.9 19.8 17.2

Rs. 1400 71.3 63.8 68.8

Rs. 1401 to 1650 11.6 16.4 13.2

Above Rs. 1650 1.2 0.8

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Average gap between cash spent and cash received 1555 1309 1471

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

1.2 Post-natal Care

Post-natal care (PNC) is an important part of the JSY programme as it is intended to ensure proper health for both the child and the mother. It includes a post-natal check up in the first 24 hours after delivery, counselling on breast-feeding, post-natal advice given within 7 days after the delivery, and advice on complementary feeding. At the overall level, the proportion of those who receive access to four services varies between 65 and 76 per cent, which also means that the remaining 35 to 24 per cent of the women did not receive post-natal services at all. Across caste groups for the four services, the higher castes had relatively high access to the services, which varied from a minimum of 69 per cent to a maximum of 79 per cent. In contrast, for the SCs, the access varies between 62 per cent to 74 per cent for the SC women. The access was particularly low where post-natal advice within 7 days of the delivery was concerned, though this is the crucial period for the newborn child. Thus, it emerges from the results of the survey that access to the four post-natal services was generally low for all the beneficiaries of JSY, with the figure ranging from 25 to 35 per cent for women who did not receive any of the services under the scheme, and this low access was particularly noticed in the case of SC women.

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 153

Table 4: Utilisation of PNC (in per cent)

PNC Rendered SCs Higher Castes

Total

Newborn babies receiving post-natal check-up in the first 24 hours after delivery

74.70 78.80 76.00

Mothers receiving counselling for initiation on breastfeeding 67.90 70.80 68.80

Mothers receiving post-natal advice within 7 days of the delivery 61.90 71.70 65.00

Mothers receiving advice on complementary feeding 67.80 69.10 68.20

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

1.3 Role of Service Providers

It was found that the ASHAs played a major role in helping pregnant women get their JSY cards. Of the total beneficiary who received the JSY cards, about 52 per cent got them with the support of the ASHAs, while the remaining received support from both the ANM and anganwadi workers, with both of them accounting for 22 per cent each of the beneficiaries. It was also observed that though the proportion of SC women covered by the ASHAs and anganwadi workers was the same as that for the higher caste women, the former provided somewhat lower assistance to the SC mothers as compared to the higher caste mothers.

Although the ASHAs offered significant help in the registration of the women under the scheme, yet they visited only 73 per cent of the households during registration and did not make any visit to the remaining 27 per cent of the households. It was also observed that the ASHAs visited only 70 per cent of the SC households during registration, a figure that is lower than the corresponding figure for visits to high caste women (81 per cent). It is, therefore, clear that the ASHAs make fewer house visits to the SC households for registration as compared to the higher caste households.

Table 5: Service Providers Who Helped the Beneficiaries Get JSY Cards (in per cent)

Service Providers SCs Higher Castes Average

ASHAs 54.10 53.30 53.90

ANMs 22.60 20.81 22.00

Anganwadi workers 21.10 25.38 22.50

NGOs 1.20 0.51 1.00

Panchayat 1.00 0.00 0.70

Registration of Pregnant Women through Home Visits by the ASHAs

Yes 69.8 80.6 73.3

No 30.2 19.4 26.7

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

154 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

As regards help rendered in taking the mother to the hospital, at the overall level, almost 44 per cent of the mothers were helped by the service providers (ASHAs/ANMs/AWWs) while the remaining 56 per cent depended on the family members and relatives. It is also clear that a lower proportion of SC women received help from the service providers (42 per cent) as compared to the higher castes (48 per cent). In the case of help offered during an emergency, at the overall level, about 61 per cent women received help from the health personnel. Here again, the ratio was lower for SC women (57 per cent) as compared to that for the higher castes (at 68 per cent). Further, as many as 40 per cent of the SC women had to depend on their families and friends instead of the health personnel for support. This clearly shows that SC women received relatively less support from the service providers during periods of hospitalisation and emergency care than did members of the higher castes.

Table 6: Help Received by the Women in Reaching the Hospital (in per cent)

Helped in taking the mother to the hospital came from: SCs Higher Castes TotalASHA 36.7 39.7 37.8ANM 3.3 3.9 3.5AW worker 2.3 4.3 3Family members/relatives 57.6 52.2 55.7Total 100 100 100Help offered during an Emergency by:Health Personnel* 57.4 68.3 61Family and friends 39.9 28.9 36.2

Note: *includes Doctors, Nurses, ANMs, ASHAs and AWWs.

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

1.4 Summary

i. The Overall Level: The study highlights the important features with respect to the access to and utilisation of health services providers under the JSY. It emerge that the utilisation in terms of institutional delivery was fairly high, that is, 85 per cent of the mothers who registered with JSY delivered in a government healthcare facility, while 65 per cent of the mothers received ante-natal care and 76 per cent received post-natal care. On an average, women received Rs, 1263 in cash assistance for delivery in the hospital.

The above figures, however, also indicate that 15 per cent of the women did not receive institutional facilities, 35 per cent did not receive ANC and 25 per cent did not receive PNC. The proportion of those who received access to four PNC services varies between 65 and 76 per cent, which also means that 35 per cent to 24 per cent of the women did not receive the post-natal service. The cash assistance was much less, that is, Rs. 1263, as compared with the actual expenditure of Rs. 2734. Thus, there is a need to increase the coverage in institutional delivery and in ANC and PNC services, as well as to increase amount of cash paid for the delivery.

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 155

There is also a need to improve delivery of the health services by health personnel. Only 21 per cent of the women received visits three times as per the norms while about 35 per cent of the households did not receive any visits by service providers. Further, about 26 per cent of the women did not receive help in registration, 55 per cent in being taken to the hospital and 36 per cent in case of an emergency

ii. Inter- caste Disparities: While this was the situation at aggregate level, the access and utilisation vary for SCs and higher castes. SC mothers lag behind in terms of access to various services and utilisation as compared with the high castes. About 83 per cent of SC women had a delivery in hospital as compared to 90 per cent of the higher castes. The proportion of SC women receiving ANC was 63 per cent as compared to 70 per cent for the higher caste women. Similarly, the SC women had fewer visits by the health personnel as compared to the high caste women, and they received less cash and less help from the health personal in registration, in being taken to the hospital and during an emergency.

2. FACTORS RESPONSIBLE FOR LOW ACCESS AND UTILISATION

Three things emerged quite clearly from the analysis of the working of JSY. Firstly, it is obvious that extending JSY services has met the objective of promoting institutional delivery and extending the pre- and post-natal care and support to women and children. Secondly despite this achievement, however, there are spheres wherein the target of full coverage still falls short. Thirdly, the access and utilisation are relatively less for the SC women as compared with the high caste, indicating unequal access to the lower caste women.

It also emerged from the analysis that some causes are common for less access to health services to both the SCs and higher castes, but there are group-specific reasons for lower access to JSY in the case of the SCs. In the case of both common factors and caste- specific factors in the case of the SCs, the weakness in the delivery of health services by the health providers is the main reason for lower access and utilisation.

2.1 Registration for Services

Registration becomes the first important step for utilisation of the health services under the scheme. The registration process is facilitated by ASHAs and other health link workers whose role is to identify pregnant woman and facilitate their registration. When asked about the nature of the difficulties faced by the beneficiaries, about 22 per cent of the mothers reported facing difficulty in registering for JSY. While 78 per cent did not report any difficulty, nearly 11 per cent of mothers reported that reluctance on the part of the service providers to provide advice (despite frequent requests) was the main difficulty they faced, 8 per cent of the respondents reported corruption in the form of demand for excess money by the service provider as the main reason for low registration (Table 7).

156 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

Table 7: Difficulties Faced by Women during Registration (in per cent)

Difficulties Faced SCs Higher Castes

Average

Requested service providers for help several times 10.90 9.77 10.50

Service providers asked for money 8.80 6.90 8.20

Service providers avoid rendering service because of the caste/religion of the women

4.40 0.00 4.40

No difficulty faced 75.90 83.33 77.90

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

2.2 Ante-natal Care

In response to our questions regarding ANC, we received 507 responses stating the reasons as to why some women are not able to access ANC. More than 30 per cent of the women did not receive any ANC. Lack of information on ANC services from the service provider was cited as one of the most important reasons, it was reported by 36 per cent of mothers. As regards the other reasons for the women failing to access ANC services, 14 per cent of the mothers indicated the absence of transport facilities to visit the health centre and 8 per cent of them cited the poor quality of services (Table 8).

Table 8: Reasons for Not Taking ANC (in per cent)

Reasons SCs Higher Castes Total

Lack of information from the service provider 36.0 33.1 15.5

No support at home or in the neighbourhood 5.8 4.7 5.5

Superstitions 4.2 3.5 4.0

Felt that it was not necessary 6.3 5.2 6.0

The service is expensive 2.6 7.0 4.0

Health facility is too far 5.6 6.4 5.8

No transport facility available 12.4 16.3 13.6

Poor quality service at the health centre 9.0 5.2 7.8

No time to go to the health centre 2.4 2.9 2.5

Staff not present 0.3 0.0 0.2

Non availability of ultrasound, blood and urine test in

the health centre

15.3 15.1 15.3

Any other 0.0 0.6 0.2

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

The following results of the FGDs also provide an insight into the problems faced by women in accessing ANC services.

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 157

“We do not get any support from the ASHAs and ANMs. The ASHA comes only when the ANM visits us. The ASHA does not pay house-to-house visit to inform us about immunisation. She informs some women and tells them to inform everyone. So sometimes we get the information late and are thus unable to go to receive immunisation. Moreover, the time for immunisation coincides with our working time, so it becomes difficult for us to leave our work and go to receive immunisation.” (Mixed Women FGD, FGD No. 51,141, Village No. 04, Jamtara, Jharkhand, 2012)

2.3 Post-natal Care

Among the 507 responses received regarding the reasons for some women not being able to access PNC, lack of information on the provision of these services in the village was one of the most important reasons for the mothers not accessing PNC, as reported by nearly 38 per cent of the mothers. The poor quality of services was the next most important reason cited by 17 per cent of the mothers, while another 17 per cent mothers indicated that the facility was too far away (Table 9).

Table 9: Reasons for Not Receiving PNC (in per cent)

Reasons SCs Higher Castes Average

Lack of information from the service provider 42.2 32.9 37.5

Superstitions 7.0 8.7 7.5

Health facility is too far 15.6 19.5 16.8

No transport facility available 10.6 18.1 12.8

Poor quality service at the health centre 18.7 13.4 17.2

No time to go to the health centre 5.9 7.4 6.3

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

2.4 Difficulties Faced during Institutional Delivery

Among the major problems faced by those who reported difficulties in having an institutional delivery, the unavailability of medicines emerges as the most common difficulty. In 49 per cent of the cases, the mothers were asked to purchase medicines from outside the hospital for their delivery. The other problems faced by the women who opted for institutional deliveries include the rude behaviour of the healthcare staff, ignorance and lack of proper attention from the latter, not being examined properly by the staff, and failure of the hospital to provide a bed or forcing the would-be mother to share a bed with another patient during the process of delivery.

It has also been observed that many of the women prefer to have deliveries at home in contravention to the main objective of the JSY of promoting institutional deliveries among women. Some of the major reasons cited by mothers for their decision to opt for having

158 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

the delivery at home include financial constraints in seeking an institutional delivery, failure to reach the healthcare facility in time, lack of availability of transport facilities at the time, absence of institutional services in the locality, access to better care at home, lack of knowledge about the available services, and the women being more comfortable in entrusting themselves to the care of dais (midwives). The other reasons cited by mothers for not going in for institutional deliveries include poor quality of services, lack of family permission, the doctors not being available in the PHC when required, and the absence of suitable infrastructure for ensuring smooth and efficient deliveries in the PHCs.

Table 10: Reasons for Delivery Taking Place at Home (in per cent)

Reasons SCs Higher Castes Average

Financial constraints 53.5 53.8 53.6

No time to go to the health centre 53.5 46.1 51.8

Unavailability of transport facility at that time 52.3 42.3 50

Unavailability of institutional services at the locality 47.1 53.8 48.6

Better care available at home 33.8 52 41.9

Lack of knowledge of available services 37.2 50 40.2

More comfortable with dais 34.1 38.5 35.1

Poor quality service at the health centre 33.7 34.6 33.9

Not necessary/customary 24.7 32 26.4

Family did not allow 22.1 23.1 22.3

Doctors not available in the PHC whenever required 17.6 26.9 19.8

No connecting road to the health facility 18.6 19.2 18.8

Any other 7.7 0 6.7

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

3. CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN THE CASE OF THE SC MOTHER

In addition to the common problems mentioned above faced by all the mothers, including both the higher caste and SC women, the SCs also reported caste discrimination as one of the main causes for low access to and use of health services. The field level health worker, paramedical staff and doctor provided discriminatory access to the SC women it affected their access to health services and their health status (Acharya 2010). Discriminatory access of health services to SC women indirectly affected the nutritional status of the SC Children (Sabharwal 2011, Diwakar 2014). We, therefore, examined the nature of the differential treatment experienced by SC mothers using the social exclusion framework (Thorat and Sabharwal 2010). The results reveal that SC mothers faced discrimination in: a) registration for the JSY scheme, (b) access to ANC services, c) access to PNC services, and, d) the process of institutional delivery, and e) receiving cash assistance for giving birth in the hospital.

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 159

3.1 Registration for JSY

It emerge from the responses that a high proportion of SC mothers (25 per cent) than higher caste mothers (17 per cent) reported difficulties in registration for JSY. This relationship between caste groups is statistically significant as revealed by the chi square test (c2 =4.87, p = 0.01).

The nature of difficulties reported by SC mothers mostly relate to the service providers and their discriminatory behaviour in the provision of various services. The discriminatory treatment assumes various forms. About 51 per cent of the SC mothers reported that the ASHAs did not visit their homes to provide information about the registration process, 37 per cent reported that since the ASHAs are members of the upper castes, they generally avoid visiting ‘untouchable’ localities, and 9 per cent of them attributes caste prejudice as reason for the ASHAs not visiting the SC localities (Table 11). The SC mothers in the focus group discussions stated the following:

“The ASHA rarely visits the SC bastis (localities) as she belongs to a higher caste. So, we have to especially call her for registration.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 11,221, Village No. 6, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, 2012)

Some reported lack of awareness as a factor for low registration, due to infrequent visits of health providers to untouchable localities and inadequate dissemination of information about the JSY. The lack of information is also aggravated by the venue of the meeting, which is invariably a high caste locality. The SC women are thus generally reluctant to attend the meeting due to the socially hostile milieu and the possibility of encountering discrimination in the meeting held in a higher caste locality.

Table 11: Difficulties Faced in Registration for JSY Services on the Basis of Caste Status

Difficulties in Registration Percentage

ASHA does not visit my house 51.0

ASHA belongs to an upper caste 36.5

Lack of awareness because ASHA by-passes the Dalit locality due to caste and religious biases

9.4

Meeting was held in upper caste locality so hesitation in going there 3.1

Total 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

3.2 Ante-natal Care

The lack of information emerged as the main reason for the low use of ANC services by the SC women. About 17 per cent of the SC mothers reported lack of information about available services as a reason for not availing of the ANC service as compared to 12 per cent high caste women.

160 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

The lack of information was mainly responsible for the poor participation of SC mothers in the monthly meetings held on the village health and nutrition day (VHND). This was mainly due to the fact that the anganwadi workers avoid calling the SC women for these monthly meetings held on the VHNDs. About 22 per cent of the SC mothers also reported that the ASHAs from the higher castes visited their houses less frequently than those of others (Table 12).

“The ASHA, who belongs to a higher caste, does not visit the lower caste localities to give advice as per the guidelines and the problems faced by pregnant women and to give other necessary information. Instead she sends her husband to give information, we feel shy and intimidated by him.” (SC Women the FGD, FGD No. 12,241, Village No. 16, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, 2012)

The various aspects of discrimination emerge from the following FGDs:

“The service providers practice untouchability as they do not touch us during ante-natal and post- natal care check-ups for performing tasks like weighing and immunisation.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 11,211, Village No. 5, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, 2012)

“The ANM talks to SC women and children unwillingly. This is because she considers SC women and children as dirty and backward. If any SC women ask any question, the ANM says, ‘Kya karoge puchkar? Tum nahi samjhoge, dava mil gayi aab jaoo’” (‘What will you do with the information? You would not understand, it is enough that you have received the medicine, now just go.’).” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 42,231, Village No. 15, Maharajganj, Uttar Pradesh, 2012)

Table 12: Difficulties Faced in Accessing Ante-natal and Post-natal Care Services Due to Caste Status

Difficulties Cited by the SC Women in Accessing ANC Percentage

Anganwadi worker avoids calling me for monthly meetings/village health and nutrition day (VHND)

25.2

ASHA from the higher caste visits my house less frequently as compared to others so there is lack of information and less awareness on the availability of ante-natal facilities and its benefits

21.9

Health workers avoid giving IFA tablets in my hand to avoid physical touch and therefore drop them from a distance on the hand in an undignified and humiliating manner

9.4

Difficulties Cited by the SC Women in Accessing PNC

Health workers visit my house and locality less frequently to inform me on feeding/counselling at the time of PNC

25.0

Avoid holding my newborn child for weighing and ask me to do it 6.8

Avoid holding the hand of my child for immunisation and therefore causing pain and inflammation

6.4

Ask someone from the SC community to give polio drops to children to avoid touching SC children

5.3

Total 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 161

3.3 Post-natal Services

Again a high proportion of SC mothers reported lack of information from the service provider as a reason for not availing of PNC as compared to higher caste mothers (42 per cent vis-à-vis 32 per cent). This also means that ASHAs failed to reach out to SC women to provide them information. About 25 per cent of the SC mothers indicated that the ASHAs from the higher castes visited their houses less frequently than those of others (Table 12). Over 18 per cent reported untouchability-related discrimination in accessing PNC. The forms of untouchability were: AWWs avoid holding newborn children to weigh them and instead asking mothers to do it (7 per cent), ANMs avoiding holding the hands of children for immunisation, and therefore causing pain and inflammation to the baby (6 per cent), and asking someone from the SC community to give polio drops to the children to avoid touching the SC children (5.3 per cent). The following passages from the FGDs highlight the discrimination faced by the SC women.

“The anganwadi worker helps in the registration but the ASHA does not. The ASHA and the ANM do not visit the SC basti (locality), so we have to go to the primary health centre for ante-natal and post-natal care. Moreover, the ASHA does not like to touch Dalit women and children.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 11,221, Village No. 6, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, 2012)

“The ASHA never visits any SC family within seven days of the childbirth for the check-up of the newborn whereas she regularly visits the higher caste families after childbirth for check-ups.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 72,231, Village No. 15, Malda, West Bengal, 2012)

“The ASHAs accompany pregnant women to hospital at the time of delivery. However, they never visit their home post delivery. Also, ASHAs do not give any advice on breastfeeding and on other precautions to be taken.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 51,231, Village No. 07, Jamtara, Jharkhand, 2012)

“Neither the ASHAs nor the AWWs pay a post delivery visit.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 52,131, Village No. 11, West Singhbhum, Jharkhand, 2012)

3.4 During Institutional Delivery

The women from SC community also face discrimination during institutional deliveries in the following ways: being asked to clean the child themselves as the service provider did not want to touch the untouchable child, being kept waiting for a long time (17 per cent), facing the use of abusive language at the time of delivery (14 per cent), being provided beds away from the higher caste women (11 per cent), being forced to have the delivery on the floor without a bed, sharing a bed and placement of their bed in the corridor (about 9 per cent). The following excerpt from an FGD illustrates the difficulties faced by SC women at the time of giving birth:

162 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

“The nurses in the hospital do not behave well with people like us who are poor and belong to the lower castes. For every little thing she uses abusive language. When we try to talk to her, she responds angrily . If we inform her about any problem that we face, she never responds to the problem and remains seated in her room. However, after the baby is born, she demands money for sweets. Moreover, we do not get free medicines and vaccines from the hospital. We have to purchase them from the hospital.” (SC Female FGD, FGD No. 52,221, Village No. 14, West Singhbhum, Jharkhand, 2012)

“Many times the family members of the higher caste beneficiary women practise caste bias if they come to know that the woman in the next bed belongs to a lower caste. They then demand a bed that is quite distant from the lower caste beneficiary woman” (Interview of staff nurses from Sehore district at Budni block level hospital, 2012).

Table 13: Discrimination Faced by SC Women in Government Hospitals (in per cent)

Different Forms of Discrimination Percentage

Kept waiting for long time 16.7

Made to lie on the floor 5.0

Had to deliver the baby on the floor 4.6

Given a bed away from the higher caste women 11.0

Given a bed which was placed in the corridor of the hospital 7.1

Was asked to share a bed with another woman 7.9

Was asked to clean the child as the nurse would not like to touch the baby due to caste

49.5

Adequate medicine not provided 8.2

Use of abusive language by the health workers at the time of delivery 7.6

Any other forms of untouchability and discrimination at the time of delivery 5.6

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

3.5 Cash Assistance Given for Birth in the Hospital

The average amount of money spent by SC mothers was Rs. 318 more than that spent by the higher caste mothers. The gap between the cash spent and cash received is wider for SC mothers (Rs. 1555) than for higher caste mothers (Rs. 1309). The SC mothers also faced problems in receiving the money. While 64 per cent of them reported that they had paid money in order to receive the JSY cash assistance, another 36 per cent reported that they had to wait for a longer time in comparison to higher caste women to get their money (Table 14).

The following extracts from the FGDs shed light on some of the reasons for the high cost incurred on delivery by the SC mothers.

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 163

“We have to go to a government hospital for delivery, which is quite far and for that we have to arrange a vehicle. The cost of booking a vehicle is Rs 1000. Again, the nurses who are on night duty usually do not stay in the hospital at night. They go back to their quarters. So, if there is a delivery at night, we have to call the nurse. The nurse who comes to attend to the delivery at night sometimes charges money.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 52,211, Village No. 13, West Singhbhum, Jharkhand, 2012.)

“We have to pay for delivery in hospital. Sometimes, the ASHAs also demand money to get the delivery done.” (Mixed Women FGD, FGD No. 21,221, Village No. 06, Muzaffarpur, Bihar, 2012)

“If we give Rs 300–400 as donation to nurses and dais, then we receive some facility in the hospital at the time of delivery. If we do not pay that money, then they abuse and harass us. Tthey sometimes even put the newborn child on the floor or on a table.” (Mixed Women FGD, FGD No. 51,111, Village No. 01, Jamtara, Jharkhand, 2012)

“The nurses demand Rs 400–500 for care and delivery. If we do not give them that amount, then they keep us waiting for a longer time, use abusive language and beat the beneficiary during delivery.” (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 12,141, Village No. 12, Sehore, Madhya Pradesh, 2012)

Table 14: Difficulties Faced by SC Women in Accessing JSY Services Due to Caste Status (in per cent)

Difficulties Faced Percentage

Have to wait for longer duration to receive JSY money as compared to the higher caste women

36.2

Had to pay money to the ASHAs/ANMs to get the rightful share of the JSY money 63.8

Total 100.0

Source: Based on the data from IIDS field survey, 2011-12.

3.6 Reasons for Having the Delivery at Home

The SC women were also asked questions regarding their choice of having deliveries at home and the main reason for this that emerged from the discussion was the discriminatory practices adopted by the health providers. During the qualitative survey, many women reported that they chose to have the delivery at home because proper facilities were not provided and that the behaviour of the healthcare personnel towards them was hostile. The following passage from an FGD highlights the fact that neglect by the ASHAs or caste prejudices lead the SC women to have deliveries at home.

Among those who delivered at home, majority of them mentioned the practice of untouchability and discrimination by ASHAs and ANMs as the main reason. According

164 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

to a respondent, “Humara chhoti jati ke hone ke karan ASHA humare sath aspatal nahi jati hai.”(Because we belong to a low caste, the ASHA does not accompany us to the hospital.) (SC Women FGD, FGD No. 31,212, Village No. 10, Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, 2012)

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 The Aggregate Level

The access to and utilisation of the services by the prospective mothers at the aggregate level also differ according to the particular service offered. The utilisation level was about 85 per cent in the case of institutional delivery in a government health facility followed by 76 per cent for PNC and 65 per cent for ANC. Thus, while the utilisation was relatively high in the case of institutional deliveries, it was low in the case of ANC. This means that about 14 per cent of the eligible mothers gave birth at home; 35 per cent of the mothers did not receive ANC services, and another 24 per cent did not receive PNC. On an average, the women received Rs. 1263 per head for utilising the service, which was lower than the amounts prescribed under the norms. In fact, this amount was much lower than the actual cost incurred by the women when giving birth in a health centre (Rs. 2734). The difference in delivery cost and the cash assistance offered under the JSY per birth was thus Rs. 1471. The high cost incurred on the delivery was mainly due to higher expenses on transportation and purchase of medicines at the hospital. Besides, the cash assistance was also not made at the health centre immediately upon arrival, though that is the prescribed norm. Only 5 per cent of the mothers received the cash within a week of the delivery while about 38 per cent of them received the amount within a month’s time, while the rest had to wait as long as six months for receiving the cash assistance. Thus, none of the mothers received cash as per the JSY guidelines.

As regards the frequency of use of ANC services, only 21 per cent of the mothers were paid received three visits as prescribed in the guidelines, while 79 per cent were paid one or two visits. In the case of PNC, 76 per cent of the women received post-natal check-ups during the first 24 hours after birth, while 65 per cent received post-natal advice within seven days and 68 per cent received advice on complimentary feeding.

According to JSY guidelines, the ASHAs or ANMs have to accompany mothers to a healthcare centre during pregnancy. However, our analysis shows that in more than 50 per cent of the cases, pregnant mothers have to rely on their own family members. Even in the case of emergencies, 36 per cent reported that they took help only from family/relatives. Although ASHAs are supposed to arrange vehicles for taking the pregnant mothers to health centres, the latter have to mostly depend on private vehicles.

The study also brings out the reasons for low access and utilisation of services. The reasons are mainly to be found in the inefficient functioning of health personnel and poor administration, which affects the delivery of service. The various lacunae include

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 165

inadequate support in the registration process, resistance by the health personnel in terms of extending support, demand for facilitation remuneration by the service providers, lack of information on ANC services from the service provider, absence of transport facility, poor quality of services, and unavailability of medicine.

In the case of PNC, the reasons for the lack of service mainly include lack of information by the service provider, poor quality of services, the compulsion to undertake long-distance travel to avail of the service, and receipt of less cash than they were entitled as also failure to disburse the cash support on time by the authorities.

4.2 Inter-caste Disparities

It emerged quite clearly that SC mothers lag than the upper caste women in the use of health services by varying degrees. The disparities between the SCs and higher caste beneficiaries were relatively high with regard to incidences of giving birth in the hospital (9 percentage points), ANC (7 percentage points), and PNC (4 percentage points).

On an average, the SC mothers spent a higher amount (Rs. 2842) than the high-caste mothers (Rs. 2524) on delivery, which implies a difference of Rs. 318. Furthermore, in the case of the SC mothers, there was a wider gap between the amount of cash spent and the amount of cash received (Rs. 1555) as compared to the higher caste mothers (Rs. 1309), which means that the additional out-of-pocket expenses for giving birth in the hospital were higher for SC mothers (Rs. 1555) than for higher caste mothers (Rs. 1309). The high expenditure incurred by the SC mothers on their deliveries is also the result of the low and irregular cash assistance received by them under the JSY.

Besides, less assistance was offered by the healthcare personnel at the time of birth to SC mothers (57 per cent) than to their higher caste counterparts (62 per cent). Even in the case of assistance provided by the healthcare personnel during childbirth, the SCs lagged behind the higher castes in terms of receipt of this service, which compelled them to depend more on their family members. Even during emergencies, 68 per cent of the higher caste women received assistance from health personnel as compared to only 57 per cent of the SC women.

The disparities between SC and higher caste mothers are also clearly visible in terms of access to ANC and PNC services. While 36 per cent of the SC mothers did not receive any kind of ANC, the corresponding figure for higher caste mothers was 31 per cent. Even in the case of PNC services, the SC mothers lagged behind their higher caste counterparts. The difference was particularly high in the case of PNC for mothers after seven days of delivery. While 72 per cent of the higher caste mothers received this service, the corresponding percentage was only 62 for the SC women.

Similar variations persist in the case of visits by ASHAs to the homes of the women for registration—they visited only 70 per cent of the SC mothers as compared to 80 per cent of the higher caste mothers. Differences were also seen in the case of health personnel

166 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

accompanying the pregnant mothers. The higher caste mothers were accompanied by healthcare workers in 48 per cent of the cases of delivery, while the corresponding percentage for SC mothers was only 42 per cent. Even in the case of emergencies, 68 per cent of the higher caste women were helped by healthcare personnel as compared to only 57 per cent of the SC mothers.

In addition to the common factors, the SC mothers also suffer from low utilisation of services under the JSY due to the prevalence of caste discrimination and untouchability. The areas in which the SC mothers face discrimination include: (a) registration, (b) ANC services, (c) PNC services, (d) institutional deliveries, (e) receipt of cash assistance for giving birth in the hospital, (f) visits to the home by health workers, and (g) lack of appropriate information pertaining to the services offered under the scheme.

These factors are discussed in detail in the following section.

4.3 Spheres of Discrimination

i) Registration: The dissemination of information by ASHAs is important to allow the women to avail of the various services available under the JSY. The ASHAs are expected to visit the SC homes to provide this information. However, it emerged from the survey that the higher caste ASHAs visit the SC homes less frequent-ly than they do the higher caste homes for providing vital information regarding registration for the scheme. This is because the higher caste ASHAs are generally unwilling to visit the SC homes due to caste prejudice. Thus, fewer visits by the health workers to the SC localities lead to a lack of information and awareness among the SC women, which, in turn, results in low registration among them for the scheme. Besides, most meetings related to registration are held in higher caste localities wherein the SC women face difficulties in terms of lack of social access to the venue.

ii) ANC Services: The main problems faced by the SC mothers relate to the lack of information by the service providers and ASHAs. The differential treatment as-sumes a number of forms, which results in the lack of information and awareness about the ANC services among the SC women, and ultimately in the low utilisation of these services. It emerged from the results that the anganwadi worker gener-ally avoids informing the SC mothers about monthly meetings for disseminating healthcare tips and nutrition briefs. The ANMs also often avoid giving iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets in the hands of the SCs to avoid physical touch and drop the tablets from a ‘safe distance’ into the hands of the mothers, thus subjecting the latter to humiliation.

iii) PNC Services: The discrimination in the delivery of PNC services assumes vari-ous forms. The ASHAs, who belong to higher castes, visit SC houses less frequently than those of the higher caste women. Even the AWWs avoid holding the newborn SC children, and avoid holding the hands of these children during immunisation,

CASTE DISCRIMINATION AS A FACTOR IN POOR ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH 167

which sometimes causes pain and inflammation to the baby. They also ask some-one from the SC community to give polio drops to the children to avoid touching the SC children.

iv) Birth in a Health Centre: SC mothers reported facing discriminatory treat-ment in the healthcare centres at the time of delivery. The SC mothers are gener-ally required to clean their own child, as the higher caste service provider avoid touching the untouchable newborn child. Moreover, SCs often have to wait for a long time, encounter the use of abusive language at the time of delivery, have their beds placed away from the higher caste women or in the corridor, have to share beds or have to deliver on the floor. As a result, some SC women reported humili-ation as one of the reasons for avoiding institutional deliveries.

v) High Cost of Delivery: The average amount spent by SC mothers was higher than that by higher caste mothers by Rs. 318. Among other reasons, the low cash assistance is one of the reasons for the high delivery cost incurred by the SC wom-en. This was mainly due to the high transportation and medicine costs. Besides SC women are also required to wait for a longer time in comparison to higher caste women to get their money.

The above findings highlight the nature of discrimination faced by SC mothers in seeking health services before and after delivery from the service providers both outside and inside the health centres, which equally affects the level and quality of the services they receive. Discrimination against the SC mothers also results in lack of information and awareness, which, in turn, leads to inadequate health precautions and prevents the women from accessing the health services offered by the service providers.

The study also underscores the need to improve the administrative governance of the JSY, In addition to effecting improvements in infrastructure by augmenting connectivity and medical infrastructure, as also the supplies of medicines and the delivery of services by the health personnel. The Government must also ensure regular visits by the health workers to the homes of the beneficiary women both before and after delivery, and that the women receive adequate information as per the guidelines laid down in the JSY.

As regards the SC mothers and their newborn children, the study points to |the need for implementing a number of measures in order to ensure that these beneficiaries receive non-discriminatory access to healthcare. These critical measures are:

• Establishment of functional sub-centres, Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and anganwadi centres in the areas primarily inhabited by SC households to pro-vide the latter greater access to health services.

• Recruitment of SC anganwadi workers, ASHAs, and auxiliary nurses and mid-wives to serve members of their own community, if necessary.

• Framing of regulations (and administrative guidelines) against discrimina-

168 JOURNAL OF SOCIAL INCLUSION STUDIES

tion experienced by SC mothers in various forms in terms of accessing health services from the higher caste service providers, which would serve as a deter-rent against discrimination as practised by the higher caste service providers.

• Development of administrative rules to enforce visits by the health workers to SC localities/houses both for providing health-related information as per the JSY norms, as well as adequate pre-natal and post-natal care.

• Drafting of rules to prevent discrimination in any form against SC beneficiaries by the higher caste service providers and health workers, namely nurse and attendants in various forms.

• Conduction of public awareness campaigns against discriminatory practices.

• Organisation of workshops and orientation roundtables on a regular basis to sensitise the service providers to the various aspects of discrimination and develop an attitude of love and affinity.

Note

* This paper is based on the study “Social Exclusion and Rural Poverty: Role of Discrimination and General Factors in Access to Government Schemes for Employment, Food, Health Services, Agriculture Land and Forest Resources in the Poorest Areas in India”, a study for poorest areas civil society programme - IFIRST, sponsored by DFID, New Delhi, 2013

References

Acharya, Sanghmitra S. (2010). “Caste and Patterns of Discrimination in Rural Public Healthcare Services”, in Sukhadeo Thorat and Katherine S. Newman (eds), Blocked by Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India, pp 208-229, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Diwakar G. Dilip. (2014). “Addressing Utilisation of ICDS Programme in Tamil Nadu, India: How Class and Caste Matters?”, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Vol 34 Issue 3/4, pp 166-180.

Dhar, Aarti (2013). “Age Limit Relaxed for JSY Benefits”, Available at: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/age-limit-relaxed-for-jsy-benefits/article4736820.ece, Accessed on 22 May 2013.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2006). “Janani Suraksha Yojana—Features and Frequently Asked Questions”, Government of India, New Delhi, Available at: http://mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/FEATURES%20FREQUENTLY%20ASKED%20QUESTIONS.pdf, Accessed on 20th January 2013.

——— (2011). “Annual Report to the People on Health”, Government of India, New Delhi, Available at: http://mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/6960144509Annual%20Report%20to%20the%20People%20on%20Health.pdf , Accessed on 12th January 2013.

Sabharwal, Nidhi S. (2011). “Caste, Religion and Malnutrition Linkages”, Economic and Political Weekly, 10 December, Vol. XLVI, No. 50, pp. 16-18.

Thorat, Sukhadeo and Nidhi S. Sabharwal (2010). “Caste and Social Exclusion Issues Related to Concept, Indicators and Measurement”, UNICEF–IIDS Working Paper, Vol 2, No.1.