“CALM stands for ‘be cool, man!’”: A Black Citizen’s Patrol in Denver.

Transcript of “CALM stands for ‘be cool, man!’”: A Black Citizen’s Patrol in Denver.

1

Shay Gonzales “CALM stands for ‘be cool, man!’”: A Black Citizen’s Patrol in Denver.

In 1967 Denver confronted the possibility of the long, hot summer in a shopping

center parking lot. On a Saturday night in July, youth came out of a dance at the YWCA. One

black youth was given a ticket for jay walking. The crowd was resentful over the fairness of

the ticket. That night and the next, the Holly Square Shopping Center in Northeast Park Hill

was full of black youth. They broke the windows of several storefronts. On Monday night

Denver police ordered the youth to disperse. They cleared the parking lot with dogs and

riot sticks.1 Nathan Clark, a nineteen-‐year-‐old black man, had been playing basketball

across the street at Skyland Park. He got into a friend’s car to leave just as more than a

dozen police cars arrived. Officers, who had reportedly removed their name badges,

banged on the roof of the car with their riot clubs and told Clark and his friend to leave. The

car would not start. Clark got out to help the driver, and the police herded him across the

street into another wall of officers. He tried to walk back to the car, but he was chased by a

police officer, who struck him over the back of the legs with a riot club.2 Clark and the

officer grappled with the riot stick as Clark yelled that he had not done anything wrong.

According to the Colorado Civil Rights Commission investigator present, Clark “was beaten

to the ground …. [and] was further struck by other policemen.” The crowd watched as Clark

was beaten until that investigator intervened.3 People were angry. Black business owners

were on edge that the scene would break out into more overt acts of violence and 1Jules Mondschein, Summer of 1967—Northeast Park Hill. Commission on Community Relations. FF 21, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 2“Justice is an Expensive Luxury.” New York Times News Service. Feb 27 1970. Clipping. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 3Frank Plaut, Minority Group – Governmental Relations: Investigations and Recommendations. FF 8, Box 5. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

2

vandalism. One slept inside his store. A black storeowner and his wife were told by two

black youth around thirteen that they “would be burnt out.” When the wife of the store

owner asked what she had ever done to them, one of the youth reportedly replied, “that’s

the trouble, you’ve never done anything for us.” Resentment and tension seemed about to

break through to a major riot.

Some community members took direct action to prevent a violent reaction to the

incident. On Tuesday, August 1st, fifteen adult black militants patrolled the shopping center.

They continued to patrol for another three weeks.4 Jules Mondschein, a consultant for the

Commission on Community Relations program through the Mayor’s Office, evaluated the

racially tense situation. He concluded that if the citizen’s patrol had not intervened there was

a “strong possibility that the shopping center would’ve burned to the ground.”5 The Northeast

Park Hill area was a focal point of racial tension in Denver. The Holly and Dahlia shopping

centers functioned as gathering points for black youth from across the city and had been

considered “problem areas” for vandalism and violence over the last several years.6

For a brief period in Denver, residents of impoverished areas were paid to participate

in the federally-‐sponsored Model Cities Program to propose and implement programs

affecting their communities. They joined a Police-‐Community Relations Committee to address

the issues their communities faced with Police. In response to a crisis of policing and violence

in Denver’s Northeast Park Hill, the committee proposed Community Action by Local

Marshals (CALM), an unarmed citizen’s patrol that would draw its ranks from militant groups. 4Jules Mondschein, Summer of 1967—Northeast Park Hill. Commission on Community Relations. FF 21, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 5Jules Mondschein, Summer of 1967—Northeast Park Hill. Commission on Community Relations. FF 21, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 6Rachael Noel, Summary and Recommendations-‐ Dahlia Area Summer 1966. Commission on Community Relations. FF 19, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

3

The proposal, which was written and backed by self-‐identified “militants,” was heavily

debated but ultimately failed to maintain a coalition of support.

Denver is largely absent from histories of race and democracy in the twentieth century.

Denver’s local political development can be contextualized by other local and national

histories. Robert Self’s American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland,

discusses the development of the ideology of black power and African American challenges to

urban decline. Black power activists, part of a dynamic black political culture, turned

institutions created by the War on Poverty into community-‐controlled bodies dedicated to

“organizing the poor.”7 These controversial community organizers contributed a rich black

power discourse of community participation to debates about planning, poverty, and jobs. In

Denver, black militancy joined the federal Model Cities programs and engaged municipal

politics in radical ways. Michael Flamm’s Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest and the

Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s examines how conservatives merged and countered civil

unrest, street crime, and civil disobedience of the civil rights movement in the discourse of

law and order.8 This project examines the fight between law and order and black power

movements for community control through the press, politics and violence. A study of the

proposal exposes how resident participation challenged and tested Denver’s professional

liberals. The debate over the proposal also highlights white liberals’ struggles to articulate a

coherent meaning of militancy and black power. In the course of the debate over the citizen’s

patrol, liberals in Denver abandoned black militant political participation and turned toward

the hardening ideology of security.

7Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003) 8Michael W. Flamm, Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005)

4

A Delicate Balance

The two shopping centers in Northeast Park Hill were the focal points of racial

tension manifesting in the neighborhood. Black families had only recently settled there.

The area north of 29th Avenue had been developed after World War II as affordable tract

housing for returning white servicemen and their families. The war also provided an

economic stimulus for black families who began to settle eastward out from the Five Points

neighborhood. They reached Colorado Boulevard by 1955. Across the street, Northeast

Park Hill was rapidly “block-‐busted” through the early sixties by real estate agents who

exploited fears of a “Dark Hill.” As white residents left, the area rapidly transitioned.9 The

neighborhood north of 26th Avenue became predominantly black. Some areas, such as the

blocks surrounding the Dahlia and Holly Shopping Centers, had gone from 5% to 88% black

within only ten years.

The majority of black families living in the area in 1966 had resided in the area for less than

9Thomas Noel and William J Hansen, The Park Hill Neighborhood. (Denver, CO: Historic Denver, Inc., 2002), 20-‐22.

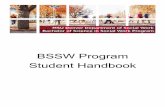

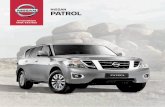

Figure 1: Racial Composition of Park Hill 1960, 1966, 1970 1960 1966 1970 # Black

Residents Total #

% Black

# Black Residents

Total #

% Black

# Black Residents

Total #

% Black

Northeast Park Hill (north of 26th avenue)

558

17,290 3.2% 10,591 16,804 63% 14,683 17,539 83.7%

Greater Park Hill Area 566 32,679 1.7% 11,512 31,066 37% 17,763 32,980 53% Sourced from: George E. Bardwell, Characteristics of Negro Residencies in the Park Hill Area of Denver, Colorado, (Denver, Commission on Community Relations, 1966). Bureau of the Census, 1970 census of Housing: block statistics, Denver, Colorado, urbanized (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1971)

5

a year. Despite some migration to the southern portion of Park Hill, the color line was

distinct at 26th Avenue.10

The social condition of Northeast Park Hill was becoming a concern. A few weeks

prior to the beating of Nathan Clark, Chris Wilkerson, a black policeman, spoke on

delinquency in the area in a meeting with the Park Hill Civic Association, an organization of

black community leaders. He asked for their support for increased police presence at the

Dahlia Shopping Center down the street. The area’s delinquency problem, he admitted, was 10George E. Bardwell, Characteristics of Negro Residencies in the Park Hill Area of Denver, Colorado. (Denver, Commission on Community Relations, 1966). Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census of Housing: Block Statistics, Denver, Colorado, urbanized (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1971)

Figure 2: Greater Park Hill Area

6

no worse than “the older Negro areas west of Colorado Boulevard and particularly west of

York St.” Wilkerson was distressed because what was perhaps, “the most beautifully

planned residential part of the city [was] going to hell.”11 According to a black community

activist the neighborhood was “a well-‐constructed community with physical elements of

middle-‐class living.”12 Jules Mondschein defined the area as “not a ghetto.”13 It was,

however, already in decline and lacked “middle-‐class money,” bus service after 7pm,

quality schools, and adequate representation on the city council.14 The combined area of

Five Points, the neighborhoods north of City Park, and Park Hill had the highest youth

delinquency cases for the city in 1968. 9% of youth enrolled in secondary school had a

delinquency filing. Northeast Denver’s high number of dropouts may have affected the

statistic, which was twice as high as the 4.3% delinquency rate in Northwest Denver.15

Youth were the cause for the recent uptick in Denver’s crime rates. From 1963 through

1965, Denver’s crime rates had bucked national trends, decreasing at a rate of about

twenty percent annually.16 In 1967 Denver rejoined the nation with a 29.9% increase in

major crimes like auto thefts, burglaries, and assaults. More than half of all felony arrests in

1966 were juveniles. Police blamed lax juvenile court judges and the Children’s Code for

encouraging habitual offenders.17 After the incident with Nathan Clark, rumors circulated

11Greg Pinney, “Police Need Support, ‘Trouble Area’ Advised.” Denver Post, July 7 1967. 12Shelley Rhym, Through My Eyes: The Denver Negro Community March 1934-‐January 1968. (Denver CO: Denver Post and Core Ministries, 1968) 13Jules Mondschein, Summer of 1967—Northeast Park Hill. Commission on Community Relations. FF 21, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 14Shelley Rhym, Through My Eyes: The Denver Negro Community March 1934-‐January 1968. (Denver CO: Denver Post and Core Ministries, 1968) 15Judith Brimberg, “Juvenile Court: Key Delinquency Areas Listed.” Denver Post, Mar 23 1969. 16Michael Rounds, “Denver’s 1965 Crime Rate down 20 percent from ’63.” Rocky Mountain News, Jan 16 1966. 17Michael Rounds, “Denver Crime Rate up by 29.9 Percent.” Rocky Mountain News, April 12 1967. Michael Rounds, “Youth Involved in Half of Major Crimes.” Rocky Mountain News, Jan 22 1968

7

that Denver was ripe for majorly destructive riots like those that took other cities.18

Something needed to be done in Northeast Park Hill to pacify the youth and prevent an

incident of police violence that could escalate the situation.

After the beating of Nathan Clark many of the city’s white liberal professionals

placed the violence in sociological terms and called to remedy the social and economic

inequality that caused it. In a letter to the editor concerning a new recreation center in the

area, Warren D. Alexander, the assistant director of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission,

contested the assertion that the disturbances were racial riots. He called the violence

“hostile expressions of a disgruntled minority over the inequalities foisted upon them by

the dominant power structure,” which, he added, “would no doubt have been termed

‘youthful exuberance’ had white youth been involved.” For Alexander, calling the incidents

“racial riots” only lent “credence to the fear and the myth that pervades the white

community.”19 Alexander knew fear of black violence was a barrier to solving racial tension

in the area. Liberals argued that the riots were hardly spontaneous. The real causes of the

disturbances, a Denver Post editorial argued, were a lack of recreation centers and jobs.20

Helen Peterson, of the Commission on Community Relations echoed this sentiment when

she said that rather than merely “maintaining the peace,” Denver needed to close the gap of

achievement and opportunity. She called for state intervention and funding for even more

“massive programs” to remedy the inequalities that lead to violence. She compared the

current War on Poverty to mere aspirin when areas in Denver required surgery.21 White

18“Will Black Denver Riot?” Denver Blade, June 22 1967. 19Alexander Warren, Letter to Gene Cervi C/O Cervi’s Rocky Mountain Journal. March 7 1968. FF 9, Box 5. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 20“What the Denver Police Must Do.” Denver Post, Aug 23 1967. 21Helen Peterson, The Model City Program’s Challenge to Denver Human Relations. FF 13, Box 12. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

8

professional liberals with a strong faith in economic intervention believed that in order to

stop youth disturbances resources would have to be reallocated. Existing federal programs

that did not offer full employment and genuine economic opportunities were simply

pacifiers.

Liberal officials and community activists alike called for more modern and

professional police. The Denver Post believed the problem lay with an older generation of

policemen who were practicing an outmoded form of policing.22 After jobs, liberals wanted

an in depth review of “police attitudes.” Black community activist Shelly Rhym asked that

police be trained in the “conditions of they neighborhoods they serve in.”23 The Denver

Blade, Denver’s black newspaper, wanted to see more black policemen in the area to

prevent any kind of incident that could lead to rioting.24 Prominent black liberal officials

and professional activists were not adverse to police presence itself, but they were upset

that Northeast Denver was both neglected and brutalized by the police, which hurt

community businesses and the community’s sense of dignity. Rachael Noel, State Senator

George Brown, and Reverend MC Williams signed a petition and press release. They

condemned police brutality and said that police directives “approximated a state of martial

law,” which had reduced the Northeast Denver community to a “concentration camp.”25

Black leaders also believed attention to disturbances damaged local businesses.

They protested sensationalized coverage of the violence. The Denver Blade stated that the

22“What the Denver Police Must Do.” Denver Post, Aug 23 1967. 23Shelly Rhym, Dahlia Summary. FF 19, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 24“Denver Doesn’t Need It.” Denver Blade, Jun 28 1967. 25Press Release. Aug 1 1967. FF 13, Box 12. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. “Negro Leaders Condemn Police Brutality.” Denver Post, August 1 1967.

9

incidents of criminal behavior “constituted vandalism, not rebellion.”26 Other black

community members emphasized that youth delinquency was everywhere, not just

Northeast Denver.27

Mayor Currigan’s liberal administration struggled to balance the allegations of

brutality from black citizens against cries from whites on the right for greater security. He

received several letters from white residents of the area who wanted a firmer police

presence. One skeptical citizen wrote to Mayor Currigan to protest the press’ repeated use

of the word “youthful” to describe vandals and rioters, as it minimized the damage to

businesses. He wrote that slum conditions and brutality were transparent excuses and

cautioned that any restriction on policemen would lead to Denver becoming Detroit.28

Currigan’s own hesitancy with the issue is even evidenced in his personal papers. Shortly

before making a statement to the press, Currigan renumbered his speech to shift the

number one priority from “law and order” to what was originally the second, a call for

Denver police to treat citizens humanely.29

Liberal solutions were inadequate and limited to policy and media advocacy. Rioting

seemed imminent. No policy solution or letter to the editor could affect the young people in

the shopping centers before nightfall. Younger people, some activists and officials believed,

were harbingers of a new militancy that rejected liberalism’s slow inclusivity. Concerned

liberals, black and white, saw the Watts Riot as an instigator of a new form of militant

26Joe L Brown, “Denver Race Problems.”Denver Blade, Aug 3 1967. 27Greg Pinney, “Police Need Support, ‘Trouble Area’ Advised.” Denver Post, Jul 7 1967. 28Lee Haas, Letter to Mayor Currigan. August 8 1967. FF 13, Box 12. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 29Thomas Currigan, Statement to the Press. August 1967. FF 13, Box 12. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

10

action, violence, and that it was contagious.30 The Denver Blade wrote that youth who

identified themselves as “enemy to society in general” wouldn’t be swayed by liberal

programs to fund recreation centers and create economic stimulus. Liberals “could build

swimming pools, grant large amounts of money, create more and better opportunities and

yet any infringement on dignity and rioters would burn it all up in an afternoon.”31

Sundiata, an African culture and history-‐oriented group that shared a building in Five

Points with the Black Panthers, rejected liberal programs. “We black men,” they wrote in a

pamphlet, “will not be given better jobs, money, homes. We must get them for ourselves.”32

Autonomy, self-‐sufficiency and dignity formed the basic tenets of black militancy. Youth

were responsive to appeals with militancy’s authenticity. One black teacher at Metro State

College phoned Mayor Currigan’s office to tell him that he was in touch with the “wrong

people,” and that he needed to be in touch with “black nationalists” who held “the respect

of younger people.”33 Jules Mondschein, in his analysis of the citizen’s patrol following the

beating of Nathan Clark, saw that the adults’ militant posturing successfully swayed the

youth. He also claimed that the members of the citizen’s patrol were effective because of

their militancy, and the youth listened to them because they had also protested the

brutality against Nathan Clark.34 Militancy held legitimacy with the youth, and activists saw

the potential efficacy of involving militants in riot prevention.

30Jules Mondschein, Summer of 1967—Northeast Park Hill. Commission on Community Relations. FF 21, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 31“Denver Doesn’t Need It.” Denver Blade, Jun 28 1967. 32Sundiata: Dignity Unity Power Pamphlet. FF 20, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 33Call from Mrs. Gwendolyn Thomas. FF 13, Box 12. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 34Jules Mondschein, Summer of 1967—Northeast Park Hill. Commission on Community Relations. FF 21, Box 19. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

11

In 1967 the Colorado Commission of Civil Rights authored a report showing that the

Denver Police Department perpetuated a racist culture. Patrol cars regularly shone their

lights into each home in the primarily black sections of Park Hill. Police told groups of

youth of color to “break it up” without any justification. Illegal searches were

commonplace. A civil rights commission investigator observed an officer using an Amos and

Andy dialect while arresting and booking a black man.35 The problem was deeper than

personal prejudices and resultant hostilities against communities of color. The police force

was also overwhelmingly white. Only twenty-‐two black officers were employed in August

1967, with none above the rank of detective or technician.36 According to the Civil Rights

Commission’s investigation, the Denver Police Department maintained a program within

the Community Police Relations Bureau exclusively for youth in Northeast Denver. Youth in

the program were instructed by police officers to “respectfully answer questions” and if an

officer asked, “always consent to a search,” including “offering to open the trunk."37 The

Police Departments largest community relations program was instructing the youth of

Northeast Denver to waive their constitutional rights.

The study pressured Mayor Currigan to reform the Police Department. Currigan

began by appointing a new police chief, George Seaton. . Seaton was chosen to straddle the

divide between liberal discourses about jobs and community relations and a pragmatic

approach to security. Police Chief Dill announced his resignation November 1st. The Denver

Post speculated that Dill lacked “enthusiasm for [Currigan’s] community relations ideas,

35Frank Plaut, Minority Group – Governmental Relations: Investigations and Recommendations. FF 8, Box 5. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 36Bruce Wilkinson, “Potter Wants Emphasis in Race Relations.” Denver Post, Aug 22 1967. John Tooley, “Minority Problems: Bureau Handles Frequent Issues.” Denver Post, Aug 22 1967. 37Frank Plaut, Minority Group – Governmental Relations: Investigations and Recommendations. FF 8, Box 5. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

12

especially in regard to minorities.” In a statement shortly after the was named, Seaton said

he saw the role of police as “maintaining democracy” and identified the two major barriers

to this goal as rising crime rates and the “struggle for social tranquility.”38 Seaton was

contributing to a newly emerging discourse of “law and order” that collapsed racialized

civil disorders and civil rights as incursions on a right to security and peace. He mirrored

the liberal doctrines that civil disorders were primarily caused by lack of economic

opportunities. He also planned to modernize the police department with training in human

relations and help from sociologists. Seaton added staff to the Police Department’s

Community Relations Division, a department charged with improving relations with

minorities.39 Under his new training program, officers were required to take college

courses and were given training in basic crowd control with weekly refreshers.40 Pragmatic

about security, Seaton also formed a riot squad, which was specially trained by the FBI. To

aid the liberal image of a modern, professional and community-‐oriented policeman, Chief

Seaton also ordered regular officers to stop wearing the signature hard helmets and

replace their riot sticks with mace.41 White liberals were originally hopeful about Seaton’s

potential as a reformer. A Denver Post editorial praised his intentions with regards to

police-‐minority relations, but warned that even the most “enlightened” chiefs would face

difficulty keeping the peace with the “present volatile mood of the minorities.”42

Chief Seaton was capable of negotiating with liberal city officials to project a

cohesive liberal image. In the spring of 1967, he began making stronger statements about

38“Detective Captain is Promoted: Seaton is Police Chief, Dill Successor Says he Plans some Changes.” Denver Post, Dec 29 1967. 39“Seaton to Attack Strife Causes.” Denver Post, Dec 31 1967. 40“Denver Police Chart Aid-‐to-‐People Plans.” Denver Post, Dec 31 1967. 41“Denver Police: Riot Controls Slated.” Denver Post, Jan 14 1968. 42“Seaton Impresses Minority Leaders.” Denver Post, Jan 15 1968.

13

civil disorders to the chagrin of the Commission on Community Relations.43 In one article

he specified an additional special unit to combat a crime wave that would also be used for

riots.44 The Commission invited Seaton to an off-‐the-‐record meeting to discuss their

concerns about the “too-‐widely publicized news stories about ‘riot control.’”45 Seaton was

responsive. In an interview that appeared in the Denver Post a few days after the meeting,

he presented Denver’s riot control plan as less militaristic than other cities’. He told the

reporter that the civil disorders plan was secondary to the departments’ programs to

prevent disorder. The prevention efforts Seaton mentioned included targeted minority and

youth relations programs as well as a plan to hire and promote more minority officers.

Seaton recognized that the relationship between the community and the police department

was one of the main sources of minority group satisfaction.46 The Commission on

Community Relations wrote to praise him. Seaton was, at first, a pragmatic security minded

official with the ability to tailor his language to an established liberal platform.

Crisis and Response: The Summer of 1968

On June 13, 1968, a party let out around ten thirty at night, and a hundred youth

gathered at the Holly Shopping Center. Richard Clark, a consultant with the Commission on

Community Relations, was in the area and later reported that the crowd was peaceful.

Reverend Jonathan Fujita passed the crowd on his way home and also noticed no violence

43“Violence Won’t be Tolerated.” Denver Post, Mar 3 1968. Letter from Commission on Community Relations to Chief George L. Seaton, March 14 1968. FF 22, Box 18. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 44“Police Task Force Announced.” Denver Post, Mar 7 1968. 45Letter from Commission on Community Relations to Chief George L. Seaton, March 14 1968. FF 22, Box 18. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 46Dick Thomas, “Police Map Disorder Control.” Denver Post, March 17 1967.

14

or rock throwing.47 At eleven, a squad car announced the curfew. Clark and other

community members worked through the crowd, trying to get the youth to disperse.48

More police arrived, and Clark decided to stay within the crowd to “maintain effectiveness.”

He saw the youths’ growing resentment toward the officers. Clark noticed a cloud of smoke

coming from an alleyway. Believing there was a fire, he ran directly into what he

discovered to be tear gas. The gas had been set off without warning from two sides of the

street.49 Residents had to leave their homes, and some received medical treatment from the

fire department. Clark called Minoru Yasui, the Director of the Community Relations

Commission, who immediately sent off a memo to Chief Seaton late that night. Yasui wrote

to Chief Seaton that many in the neighborhood believed the “police felt free to

indiscriminately release tear gas because these were Negroes—not citizens or human

beings.” Clark worried that the incident would lead to greater violence in Northeast Denver.

The gassing signaled the close of an amicable relationship between Seaton and liberal city

officials. Seaton expressed his frustration with the youth in Northeast Park Hill to the press.

In response to Yasui’s memo, an “irate” Seaton told the director and the press that Denver’s

patrolmen were “tired of baby sitting … every weekend night.”50 Activists remembered the

chief’s paternalism later.51 Seaton’s refusal to issue an apology for the gassing signaled the

shift of his discourse toward security and a revival of the previous summer’s tensions.

47Interview with Reverend Fujita, June 14 1968, FF 22, Box 18. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 48Memo to Chief Seaton, from Minoru Yasui, June 14 1967. FF 22, Box 18. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 49Interview with Reverend Fujita, June 14 1968. FF 22, Box 18. Thomas G. Currigan Papers, WH929, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library. 50John Tooley, “’Tired of Baby Sitting’: Seaton Defends Gas Use.” Denver Post, June 18 1968. 51Clemens Work, “Negroes Discuss Racial Tension.” Rocky Mountain News, June 23 1968.

15

Another incident broke out a few days later. On Friday, June 21st, police responded

to a call about a fight in the parking lot of the Park Hill Shopping Center where around 150

youth were gathered. One youth, Nathan Jones, came out of the crowd toward the patrol

car. Officer Robert Moravek asked if he was hurt. Jones lifted his shirt and in the same

motion, shot at Moravek, grazing the back of his head. Moravek responded with four shots

out of the window, hitting Jones and two other youth in the crowd. His partner quickly

drove Moravek to the hospital, leaving Jones behind. Moravek’s partner radioed for more

officers. Chief George Seaton had been conferring with district Captain Doral E. Smith a few

blocks away and responded to the scene within a few minutes.52 When they arrived they

were confronted with an angry crowd.53 There was a brief standoff. Someone in the crowd

of black youth yelled “Civil Rights!”54 Officers were then pelted with rocks and bottles.

Someone in the crowed shoved Chief George Seaton.55 The police laid down a blanket of

tear gas without warning. Observers worried that Nathan Jones, who was still on the

ground, could not breathe.56 Some black community members attempted to disperse youth

over bullhorns. Newspaper reports carried differing accounts of their success.57 A riot

began and spread to the nearby Five Points neighborhood.58 The press detailed many

incidents of racialized violence against white people. One older white man was attacked by

youth who threw rocks through his car windows.59 White owned businesses downtown

52Michael Rounds, “State Patrol Aids Police In Tense Denver Areas.” Rocky Mountain News, June 23 1968. 53Richard O’Reilly, “Chief Seaton Gives Report on Shootings, Investigation.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. Harry Gessing and Fred Baker, “Police at Site; One Critical in Hospital.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. 54Charles Green, “Details are Described by Witness at Center.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. 55Ed Pendleton, “Bystanders Bewildered After Shooting.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. 56Ed Pendleton, “Bystanders Bewildered After Shooting.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. 57Harry Gessing and Fred Baker, “Police at Site; One Critical in Hospital.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. Michael Rounds, “Rights Leader Is Beaten, Robbed in Disturbance.” Rocky Mountain News, June 23 1968. 58Michael Rounds, “State Patrols Aid Police in Tense Denver Areas.” Rocky Mountain News, June 23 1968. 59Harry Gessing and Fred Baker, “Police at Site; One Critical in Hospital.” Denver Post, June 22 1968.

16

and on Welton Street were vandalized and looted.60 A Denver Post reporter witnessed

several black youth attack a white gas station attendant. Minoru Yasui was mugged; the

Japanese internment survivor said he had “apparently” been mistaken for an Anglo.61

After the are cooled off, black residents mobilized. Around three hundred met

Sunday in the Curtis Park Community Center. They elected George L. Brown, a state senator

from Denver, to serve as their spokesman. Brown announced their plans to march and

meet again Tuesday afternoon to issue their demands to the city. Flanked by some of his

unidentified “young friends,” Brown said that the black community did not need whites in

their march.62 Joe Boyd, a middle-‐aged letter carrier and secretary to the newly formed

Police-‐Community Relations Committee under Denver’s Model Cities program, attended

the meeting. He wrote in a memo to the committee, “I was in a meeting with some more

reputable people of east Denver area and we were in agreement that we should try to

prevent this necessity by patrolling in advance of these incidents in order to alleviate the

police department’s involvement.”63 Before the march on Tuesday the newly formed group

called Black Citizens United asked a student from Adams State College to read their

demands from the steps of the City and County Building. The exact details of the group’s

membership are absent from newspaper accounts. They claimed to represent the “entire

black community,” but according to a reporter, the march on Tuesday consisted primarily

of young men. Their militancy was also unspecified. They maintained a calm and friendly

relationship with the black police officers who escorted the march. Senator Brown denied

60Richard O’Reilly, “Chief Seaton Gives Report on Shootings, Investigation.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. 61Ed Pendleton, “Bystanders Bewildered After Shooting.” Denver Post, June 22 1968. 62Greg Pinney, “Negroes Plan Denver March on Tuesday.” Denver Post, June 24 1968. 63Joe Boyd to Police Community Relations Committee, June 17, 1968. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

17

rumors the march would be violent. “We are wonderful, beautiful black people, and we

know how to act,” he said, rejecting the idea that the group would riot. After the march, the

group gave their demands from the steps of the capitol. They pledged to end vandalism and

disturbances. They wanted the immediate removal of all white police officers from the

black community. They said white police couldn’t effect a solution because they were a part

of the problem, and some within the group declared they were the whole problem. They

also pledged to set up their own citizen’s patrol. They called for an end to the use of “tear

gas, mace and riot sticks, ‘stop and frisk’ as well as abusive language, inhumane treatment

and disrespect of all black people.” In addition to these moves toward autonomy and

dignity, they wanted the city and state to allocate more resources to riot prevention, the

inclusion of black men in policy-‐making, and less sensational reporting from the news

media.64 According to a reporter, a “cadre of militants who declared they were unsatisfied

with the march” confronted Senator Brown afterwards. The reporter concluded the article

with the statement that despite this interruption, “Brown prevailed” when the march

peacefully dispersed as scheduled. Available accounts support the idea that although Black

Citizens United was made of young, black men, they represented a variation of black power

rhetoric that garnered a broad coalition of support and rejected the spectacular tactics of

groups like the Black Panthers.

The Denver Post ran an editorial a few days later in support of most of the group’s

demands. The paper called the group’s pledge to contribute to reforms a “constructive

manifestation of black dignity,” which gave meaning to previously empty terms like “black

power.” The paper was hopeful that the group which it wrote, “represented virtually every 64Richard O’Reilly and Leonard Larsen, “Tuesday March: City Negros List Pledges and Demands.” Denver Post, June 26 1968.

18

segment of opinion” would lead the entire metropolitan area to “peaceful progress.” The

editors did not believe, however, that the police presence in Park Hill should be entirely

black, as the neighborhood was also home to many white residents. This ignored the

concentration of black residents north of 26th Avenue. The paper did call a black patrol of

men and young men to work with the police to prevent rioting “the only way to improve

the situation until sufficient Negro policemen [could] be recruited and trained.”65

Professionalization and other traditional liberal policy-‐based solutions had failed to

remedy the situation. With this push from a well-‐packaged militant group, white liberals

opened to new strategies including expanding of black participation and recognizing

militancy as an authentic political culture.

After the rally, the Police-‐Community Relations Committee, a resident project of

Denver’s Model Cities program, met to draft their patrol proposal, Community Action by

Local Marshalls (CALM). They also heard from Nathan Jones’ brother about the shooting

and discussed gassing incidents near their home. They stayed late drafting the proposal in

preparation for a presentation to the regional branch of the federal Office of Economic

Opportunity (OEO) in Kansas City.66 CALM planned for nearly a hundred men from the

“Black and Mexican communities” between seventeen and twenty five to patrol Denver’s

five target areas, including Northeast Park Hill, to quell any “summer disturbances.” The

marshals would be recruited through militant organizations such as the Black Panthers,

SNCC, and Crusade for Justice. The marshals would patrol streets, disperse “disorderly

assemblies,” direct traffic, investigate complaints of disturbances and provide emergency

65“Negro Ideas Merit Positive Action.” Denver Post, June 28 1968. 66Meeting Minutes, Police-‐Community Relations Committee. July 2 1968. Box 305. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library

19

first aid. They wanted to begin immediately and end the program in September. The CALM

proposal received an endorsement from the OEO. They were ineligible for federal funding

but would receive any returned funds on the condition that the plan gained the support of

the Police Department.67 A few days later, Denver’s police and the city officials announced

their rejection of CALM.

CALM, along with the other demands put forth by Black Citizens United were

originally dismissed. Chief Seaton made it clear that the Denver Police Department would

not accept CALM performing any police duty. This left CALM with two tasks: reporting

unsafe conditions and assisting residents in obtaining public services. With the exception of

launching an investigation into the shooting of Nathan Jones, the Denver Police Department

and the Mayor's office rejected all of Black Citizens United's demands. Chief Seaton

explained how policies and lack of eligible candidates limited his ability to promote and

hire black policemen. He also “saw no reason” to change policy on the use of procedures

like “stop and frisk” or riot-‐control weapons like tear gas and mace. To the demand that the

city spend more money on riot prevention and less on control, Currigan countered that he

had devoted more money to social programs than any of his predecessors. The city simply

couldn’t afford to expand the programs without new revenue sources.68 The

administration’s liberal social spending program had reached its limit. That same week,

law-‐and-‐order oriented Democratic Councilman Robert B. Keating said that he and other

councilman opposed the patrol, which, “however meritorious,” would implicate “a lack of

faith in the Police Department.”69 The answer to Black Citizens United was no. The group’s

67Richard O’Reilley, “Chief Rejects Six Proposed CALM duties.” Denver Post, July 3 1968. 68Richard O’Reilley, “Only One Black Citizen Demand Met.” Denver Post, July 3 1968. 69John Morehead, “Panel Opposes Patrol Plan by Minorities.” Denver Post, July 3 1968.

20

attempts at self-‐sufficiency and autonomy challenged the professionalism of the police and

the efficacy of liberal economic interventions. Black militants, including Black Citizens

United, contested the legitimacy of a multiracial liberal coalition and demanded a role in

the allocation both of resources and creation of policy that affected them.

The situation was becoming more desperate. Denver’s black community received

threats of violence from white supremacist groups. At the same time the Black Panthers

were attacking the legitimacy of the police department to protect their communities.

Lauren Watson, leader of the Denver chapter of the Black Panthers, and other militants

interrupted a public meeting of the Commission of Community Relations. Watson hailed

the creation of civilian police patrols as the “only likely source of peace and just protection”

for the black residents of Northeast Denver. Watson claimed to have organized an armed

group that was already proving effective at preventing violence.70 Sorl Shead, a Black

Panther, had recently been arrested at the site of a riot at the Dahlia Shopping Center.

Armed, he was arrested for intervening with an officer’s arrest of a looting girl. “Get out of

here,” Shead reportedly told the officer, “I’m in charge in here and I make the reports.”71

The black residents of Park Hill felt increasingly desperate to find a solution as rumors

spread of a Minutemen attack. Reverend Phillips received a call from a “white male voice”

that threatened to bomb homes in the neighborhood if any “children gather[ed] in the

[Holly] shopping center.” Three area churches were firebombed.72 Flyers circulated in the

neighborhood claimed that Denver Police were “friendly” with the Minutemen.73

70Chuck Green, “Militants Dominate 2nd Relations Meet.” Denver Post, July 3 1968. 71Michael Rounds, “Vigilante-‐Type Patrols Distress Police.” Rocky Mountain News, June 29 1968. 72“Negro Minister Reports Telephone Bomb Threat.” Rocky Mountain News, June 29 1968. 73John Tooley, “Police Officials Deny N.E. Denver Law Breakdown.” July 3 1968.

21

As the Police-‐Community Relations Committee began to negotiate with the mayor

and the Denver Police Department, white liberals revealed their misunderstanding of and

distrust for black militancy. The downtown papers partially conflated the Black Panthers’

armed patrol with Black Citizens United and CALM. In one article, a writer presented Black

Citizens United's warning about violence due to inadequate policing as a threat.74 Another

said CALM was presented by “less militant-‐talking youths” and listed unarmed patrols as

one of the points put forth by “those advocating peaceful solutions.”75 A sympathetic

Denver Post article criticized Seaton for opposing the proposal on the basis of the residents

involved. He was quoted as saying, “I can’t even talk to these people" and “I don’t want

anything to do with them.” Shelly Rhym, a black community activist and the coordinator of

resident participation for Model Cities, countered that the committee was balanced

between moderates and militants. Rhym also explained that militants were not “advocates

of violence,” and it was better to harness their concern than to exclude it. Without militant

involvement, he said, resident participation was meaningless.76 If the administration was

going to pick which resident perspectives were legitimate, they would effectively

disenfranchise Denver’s black community.

Despite these barriers, the administration sought a compromise. They were

increasingly aware that militancy was necessary to command the respect of youth and

prevent rioting and property destruction. Militants had been credited with the de-‐

escalation of the crisis the previous summer, and some advocates said patrols of militants

74Richard O’Reilly, “Only One Black Citizen Demand Met.” Denver Post, July 3 1968. 75Chuck Green, “Militants Dominate 2nd Relations Meet.” Denver Post, July 3 1968. 76Richard O’Reilly, “CALM patrol, Seaton Policy Called Unfair.” Denver Post, July 4 1968.

22

had controlled crowds of up to 1500 people.77 In a memo entitled, “Citizen Participation in

Community Harmony,” the mayor’s office requested negotiations between CALM

representatives, the Denver Police Department, and groups like Crusade for Justice and

Black Youth United. The negotiation committee also included James E. Young, a Black

Panther. Currigan’s administration wanted the police to “recognize the importance of

utilizing some of the “‘militants’ in the program.”78 Militants could command the respect of

the youth and extend authenticity to the program’s decisions. Peace required collaboration.

The first set of negotiations was deadlocked about the genuine autonomy of the

project. The Police-‐Community Relations Committee and the Police Department disagreed

over who would have the final say in controlling the marshals. The police department

wanted marshals to fall under the Police-‐Community Relations Division within the

department. The organizers found this unacceptable to the spirit of CALM, and attempted

to mobilize support for an autonomous patrol by holding a rally.79 According to the Rocky

Mountain News, the administration sided with the police and had no plans to further

negotiate. The CALM proposers resolved not to compromise and requested a private

meeting with Currigan.80 Both sides had retrenched in their bases: Currigan quietly allied

with Seaton and the organizers of CALM turned to the larger community for support.

77Model Cities Resident Participation Retreat. July 13 1968. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 78Citizen Participation in Community Harmony, July 11, 1968. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 79Police-‐Community Relations Meeting Minutes, July 16, 1968. Box 305. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 80Police-‐Community Relations Meeting Minutes, July 16, 1968. Box 305. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library CALM chronology, July 16 1968. Denver Model City Program Records, Box 305 WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library

23

The concept of resident participation united the diverse coalition backing CALM.

Under Joe Boyd’s leadership, the Police-‐Community Relations Committee networked within

Model Cities and city government to ramp up support for CALM.81 Prior to the first set of

negotiations, the committee secured support from various committees within Model Cities,

who rallied behind the idea of citizen participation.82 Notes from the second negotiation

reveal the administration’s position on the proposal. City officials recognized that a

“different type of leadership from the Black and Brown Communities” had proposed CALM

and they felt it essential that the proposal and its leadership be maintained. However the

impasse was to be breached, both sides would need to “sell” the compromise to their

backers.83 Authenticity was essential for the patrol to be effective with the youth.

CALM Compromised: A hard sell

This second set of negotiations breached the impasse. The Denver Police

Department issued “Guidelines for Civilian Volunteer Groups,” which allowed for citizen’s

patrols of all kinds. CALM was approved by the Police Department and readied for

inclusion in the Denver’s Model Cities proposal, to be sent to the City Council and then on to

the OEO. No government funding would be involved with the patrol. The new proposal put

“overall policy control … supervision and coordination” of CALM and other patrols under

the Community Relations Division of the Denver Police Department.84 In an apparent

81Police Community Relations Committee Meeting Minutes, July 16 1968. Box 305. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 82Model Cities Resident Participation Retreat, July 13 1968, Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 83Initial Statement of Negotiator at Secret Negotiation Meeting, July 17 1968. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 84Guidelines for Civilian Volunteer Groups, July 18 1968. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library

24

reversal of their principled stance, the organizers of CALM had ceded control of the patrol’s

staffing and internal discipline to the Police Department.

Liberal city officials and black community activists celebrated the compromise as

proof that resident participation could work. The compromise also represented an effective

integration of militants into Model Cities and the Currigan administration. In his

announcement, Boyd framed the compromise plan as one that signified the closure of the

communications gap between citizens of the “hard-‐core” area of Denver and the Police

Department. This was a “real point of break through in community relations,” Boyd said of

the proposal.85 He also warned that the proposal required complete support from the

community to be effective. The celebratory rally ended with a plea for contributions to pay

volunteer marshalls. “If you turn your back on the ghetto,” Boyd warned, “you turn your

back on yourselves.”86 Shelly Rhym said CALM was one victory in a series of battles

between minority communities and the city administration in search of more autonomy in

their neighborhoods. This autonomy, he said, “is essential to freedom.” Liberal media also

commended the compromise as evidence of authentic participation. The journalist who

interviewed Rhym wrote that the “real significance” of the CALM proposal compromise was

that “some of Denver’s angrier black men decided to take a chance with a bureaucratic

system that frustrates a lot of middle-‐class whites.” Rhym also hoped that the process

would show the militants that something could be accomplished by “working on

committees and going to lots of meetings.”87 Optimistically liberal city officials and

community activists thought the compromise would strengthen a multiracial liberal

85Joe Boyd Speech, July 19 1968. Denver Model City Program Records, Box 186 WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 86Marvin Moran, “City Approves Citizen Patrol Proposal.” Rocky Mountain News, July 20 1968. 87Richard O’Reilly, “CALM Patrols: Minority, City Pact Assessed.” Denver Post, July 21 1968.

25

coalition. The resident participation celebrated by the media and Model Cities’ participants

was already tainted by the compromise with the Denver Police Department.

To the militant supporters of the CALM proposal, this level of police involvement

was unacceptable. Two organizations represented by Lauren Watson, the Black Panthers

and SNCC, withdrew support from the proposal and pledged to start their own armed

patrols. Lauren Watson issued a statement that the once-‐good proposal had been “watered

down until it [was] worthless.” “The idea of a model city is ridiculous,” Watson continued,

“as long as racist murderers like Mayor Currigan and Chief Seaton hold control over all

programs.” The original proposal, Watson said, did what Model Cities was intended to do:

give the residents of the target area control over their lives. When asked, Currigan said

Watson’s comments were “too ridiculous” to warrant a response.88 Watson was not the

only one who felt the new CALM proposal betrayed the ideal of resident participation. The

Adult Education Committee, another resident committee of Model Cities that had endorsed

CALM at the Citizen Participation Retreat, backed away from the new proposal. In the

committee’s meeting minutes, it wrote that it took the “same position as the Black Panthers

and SNCC.”89 In a statement to all the Model Cities committees, the Adult Education

Committee decried “the establishment” and its continued use of “veto power” over resident

programs as an expression of paternalism. This paternalism, it wrote, had created a

“colonial situation.” The Committee called for “the establishment [to be] taught that people

are the top priority … not property, money, … an imposed order (generally called peace), or

88Richard O Reilly “Panthers, SNCC Quit Patrols Group.” Denver Post, July 21 1968. 89Adult Education Committee Meeting Minutes. Box 305. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library

26

even law.”90 To the more militant activists, the CALM compromise meant the

“establishment” had abandoned autonomy and dignity, essential elements of black power’s

challenge to liberal politics.

The Police Community Relations Committee continued to work on CALM regardless

of the fallout. It expanded CALM to be a year-‐round program and provide additional

services within the terms of the compromise. Joe Boyd resigned from his position as a

postal carrier to fundraise for CALM full time.91

Those opposed to the proposal began to campaign against it in advance of the city

council vote. Robert B. Keating, who had been opposed to CALM since the beginning, took

advantage of the rift by conflating CALM and armed patrols. He said, “many participants in

CALM [were] the greatest agitators of unrest in our community,” and they now operated

with “the official blessing of the city administration.”92 Keating referenced the incident a

few weeks prior wherein Sorl Shead, a Panther and member of the Police-‐Community

Relations Committee, had intervened in a girl’s arrest at the Holly Shopping Center.93 In a

statement distributed to the City Council, Keating said that CALM’s militant participants

and planners would likely violate the rules of the proposal and use arms to intimidate and

interfere with police.94 The compromise, which had allowed for other citizen’s patrol

groups to form within Police Department guidelines, had spawned several “off-‐shoot”

patrols. The informal and volunteer CALM patrol had split into an additional “militant

90Adult Education Committee, Education of the Establishment, July 22 1968. Box 305. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 91July 24th Draft of CALM proposal, Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library and August 2, Letter of Resignation from Joe Boyd to USPS, Joe Boyd Speech, July 19 Denver Model City Program Records, Box 186 WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 92“CALM plan sharply attacked by Keating.” Rocky Mountain News, July 21 1968 93Michael Rounds “Vigilante-‐Type Patrols Distress Police.” Rocky Mountain News, June 29 1968 94“CALM plan sharply attacked by Keating.” Rocky Mountain News, July 21 1968

27

patrol.” Also on the street were “unarmed adults” who had begun patrolling in the summer

of 1967 and the “Virginia Vale Village Association,” a white patrol that sought to “protect

white residents.” City officials were concerned that the multitude of groups could result in a

competition for power to the detriment of community safety.95 After the above press, City

Council President Elvin Caldwell, a black representative of district containing most of

Northeast Denver, publicly cautioned against the citizens patrols.96

The CALM proposal failed to win popular support because it could not be divorced

from the armed patrols of the Black Panthers or rioting youth. Few residents polled had

heard of CALM. Only 15% knew the purpose of the specific patrol or could identify its

leadership. 70% of those polled were against citizen patrols in their neighborhood. The

perspectives of black businessmen interviewed reveal confusion about the plan’s purpose.

One said he thought “the militants” were behind CALM and that they were “hurting this

part of Denver” by destroying property. Another said that he thought CALM was “the basis

of the troubles we have been having,” and blamed the organization for making it hard for

black-‐owned businesses to get insurance.97

Public support of the CALM proposal was further damaged when Denver’s Five

Points erupted in several nights of violence. Gerald Mitchell, a black sixteen-‐year-‐old boy

caught his arm on the screen door of Gregory’s Cleaners on 28th Avenue. Mitchell told the

clerk about his injury, and the clerk called him a slur. Byron Gregory, the white owner,

came out from the back of the store and brandished a pipe at the youth. Gregory threw

cleaning fluid on Mitchell and locked him out of the store. Later that day, a group of young

95“City Civilian Patrol Plan Spawns Several Offshoots.” Rocky Mountain News, July 25 1968. 96Charles Roach, “Caldwell fears Results of Citizens Patrol Move.” Rocky Mountain News, July 25 1968. 97Ed Pendleton, “Patrols Lack Wide Support.” Denver Post, July 28 1968.

28

black men broke the store's windows and trashed the inside of the store. This escalated

into an open conflict involving youth, Black Panthers, and police. The police raided the

home of Lauren Watson and swept more than half a dozen militants into custody.98 Of

those arrested, many had affiliations with Model Cities and had been under scrutiny by

conservative politicians for receiving federal funding through the Resident Participation

program that paid for meeting attendance.99 The rioting continued into the following night.

Police responded to a kitchen fire in the neighborhood, but soon after their arrival, multiple

snipers began to fire at them. One of the arrested sniper suspects was James E. Young, a

Panther who also sat on the mayor’s negotiation committee for CALM.100 Rioting continued

in the area for several hours. Police cars were met with bottles and rocks. Once again,

newspapers reported on racially motivated muggings against white people in the area.

In the days following, Chief Seaton and others opposed to CALM capitalized on white

anxiety. Seaton enjoined sniping by Panthers, liberal social theories, and the self-‐identified

militants within municipal programs in an attack on resident participation and Currigan’s

administration. In the days after the riots, he blamed the riots on “black revolutionists,”

who he said were “working to discredit the Denver Police Department.”101 In a meeting

with Chief Seaton, a group of mostly black business owners asked for additional police

support in the Five Points neighborhood. A diligent politician, Seaton first addressed the

crowd by explaining how he wouldn’t tolerate discrimination. When the mood of the room

became apparent, the police chief switched his strategy to promising additional police

98“Angry Mob Attacks Police Car.” Denver Post, Sept 13 1968. 99Dick Johnson “Aid To Senator Probe Pushed by Dominick.” Denver Post, July 30 1968. 100Citizen Participation in Community Harmony, July 11 1968. Box 186. Denver Model City Program Records, WH1222, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library 101“Prominent Negros Call for Restraint.” Denver Post, Sept 15 1968.

29

presence and a crackdown on rioting and juvenile delinquency. Seaton blamed the area’s

under-‐policing on “bad advice” given by community relations experts and unnamed people

in Mayor Currigan’s administration. Seaton assured the group that he wouldn’t listen to the

“phony theory” peddled by the liberal administration and black militants. Encouraged by

the group’s requests for additional policing, Seaton named the militants as the problem. Joe

Boyd and Lauren Watson, among others, Seaton said, “[are] determined to run things in

this city …. They want their own black police.” He then encouraged the black business

owners to go to the mayor and make their grievances known. The business owners agreed

that “too many committees” had claimed to represent them and obscured their needs. The

riots had led the black middle class, concerned first with economic security, to ally with

Seaton and against resident participation.102

Seaton’s shift during the meeting with black business owners signified the

successful dominance of law and order and security rhetoric. In a statement a few days

later, Mayor Currigan fell in line behind Seaton and endorsed his “get tough” policy.103

Seaton pulled the liberal administration toward increased policing and away from resident

participation. CALM made no more major waves in the media until it was withdrawn in

November at the urging of the City Council.104 The Rocky Mountain News published an

editorial on the floundering Model Cities Program, which mentioned how some committees

had become wallowed in conflicts between minority leaders and existing city departments.

The editorial concluded, however, that the “ambiguous” and “ambitious” project was too

102Richard O’Reilly, “Seaton Vows Better Police Protection.” Denver Post, Sept 27 1968. 103John Morehead, “Mayor OKs Firm Police Reaction.” Denver Post, Sept 30 1968. 104Dan Bell, “CALM Proposal is Withdrawn from Model Cities.” Rocky Mountain News, Nov 8 1968.

30

costly to be effective.105 Police-‐minority relations in Denver continued to be strained, and

Seaton dedicated even more department resources to aggressively pursuing Denver’s small

Black Panthers chapter.

In the wake of a crisis of policing in Northeast Park Hill black militants injected

liberal politics with black power solutions. White liberal officials at first opened to the ideas

of autonomy, dignity and authentic participation the CALM proposal signified. The Denver

Blade had defined militancy as “vigil, an awakening, a need, an act,” and “a movement

which is already here.” The Blade continued that if anything were to be averted in the

summer of 1968 or any other, “the power structure” would have to “recognize this body,”

referring to an amorphous militancy.106 Over the course of the CALM debate, white liberals

split over the challenge of incorporating an authentically dynamic black political culture. In

crisis, liberals abandoned militant voices and dynamic strategies and turned toward an

ideology of security.

105“Model Cities Experiment.” Rocky Mountain News, Nov 15 1968 106Joe L Brown, “Change the Name Now!” Denver Blade, April 8 1968.