dynamelt d15/d25/d45 series - adhesive supply unit - Societe ...

BUNNY ROGERS SOCIÉTÉ - Societe, Berlin

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

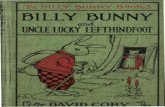

Transcript of BUNNY ROGERS SOCIÉTÉ - Societe, Berlin

Being ThereLouisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 2017

The exhibition presents 10 international contemporary artists who seek to depict the human con-dition and way of living in an era, where the physical and digital worlds are growing ever closer together.

Our lives are increasingly influenced by digital technologies and as a result the perception and concept of body, machine, life,death, sociality, isolation, nature and time are changing and taking on new meanings. At the same time, the notion that there is a physical world that is real, and a digital world that is unreal, seems to be rapidly breaking down.

The artists in this exhibition are engaged in exploring how these changes affect the way we live with each other and ourselves, and how we navigate among the ruins of an old world and the building blocks for a new one.

In the exhibition’s nine scenarios, the physical and the digital intermingle. There is no clear dis-tinction between where one ends and the other begins. Perhaps our existence right now can best be described as permanently having a foot in both camps – a state of simultaneous presence and absence, as indicated by the title, BEING THERE.

Bunny Rogers erects a self-initiated memorial to a dead high school student. She creates an image of a collapsed reality between a physical and a virtual existence by linking a one-dimensional com-ic-strip universe with a number of objects in detailed craftsmanship. The work has been created for the exhibition.

Installation viewBeing There

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 2017

Installation viewBeing ThereLouisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 2017

Brig Und Ladder Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2017

Organized by assistant curator Elisabeth Sherman and curatorial assistant Margaret Kross.

Bunny Rogers (b. 1990) interweaves reality and fiction throughout her work to reflect on experienc-es of loss, alienation, and community. For her first museum exhibition in the United States, Rogers has realized an installation in two parts. The first resembles a high-school auditorium in which an animated video takes the place of a stage. The second, accessed though a curtain, evokes a backstage area and is populated with sculptures that act as props, awaiting use in a theatrical scene that will never occur. Titled to bury private meanings in a phrase of familiar-sounding words, Bunny Rogers: Brig Und Ladder presents a mysterious and mournful narrative rife with encrypted intimate details of the artist’s life.

In building these tableaux and the surreal sculptures that fill them, Rogers aims to materialize her inner world—a personal constellation of TV shows, movies, Internet forums, and common objects—and to connect emotionally with the viewer. Culling from these sources, she reveals how emblems of youth culture have consumed her identity since childhood, much of which she spent online. She also touches on the collective as well as personal trauma of the Columbine High School shooting, which took place when she was nine years old.

Rogers’s cast of characters features archetypes of the social outsider and other tragic figures, ranging from the misanthropic outcast Joan from MTV’s short-lived animated series Clone High (2002–3) to the SeaWorld orca Tilikum, who killed three people during captivity, eliciting public shock and pity. By juxtaposing plotlines and bringing together an array of avatars for herself, friends, and family, Rogers creates a memorial for failed relationships. The diverse works on view here are united by the suggestion that sincerity and deceit, empathy and violence, are not as op-posed as they may seem. Instead, Rogers says “both extremes exist within themselves.’’

A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium, 2017Digital video, color, sound

8:27 min.https://youtu.be/vkAcR5oDdtQ

Memorial wall (fall), 2017Aluminum and inkjet prints on die-cut paper with ribbons

182.9 x 396.2 cm / 6 x 13 ft

Lady train set, 2017Wood, latex paint with chalk, and snail fossil

63.5 x 181 x 58.4 cm / 25 x 71 1/4 x 23 in

Computer chair A (Reject), 2017Plastic, chrome metal, polyurethane, and polyethelene fleece pile137.2 x 49.5 x 71.1 cm / 54 x 19 1/2 x 28 in

Computer chair D (Reject), 2017Plastic, chrome metal, polyurethane, and polyethelene fleece pile137.2 x 49.5 x 71.1 cm / 54 x 19 1/2 x 28 in

Computer chair C (Reject), 2017Plastic, chrome metal, polyurethane, and polyethelene fleece pile137.2 x 49.5 x 71.1 cm / 54 x 19 1/2 x 28 in

moving is in every direction. Environments – Installations – Narrative SpacesHamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2017

Bunny Rogers’ installation is part of a series that revolves around the processing of a collective trauma: the school shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado in 1999. In a meticu-lously planned attack modelled on military task forces and copying the type of video game know as first-person shooters, two students shot and killed twelve of their classmates, a teacher, and them-selves. The video shows a wine-drinking Mandy Moore as she appears in the episode Snowflake Day: A Very Special Holiday Special od the animated series Clone High (2003), playing three songs by Elliott Smith on a piano in the school cafeteria.

Installation viewmoving is in every direction. Environments – Installations – Narrative Spaces

Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2017

Untitled (Texas), 2016Dried infinity roses, dried red berries, plastic hydrangeas, black ribbon, artist frame94 x 154.5 x 18 cm / 37 x 60 3/4 x 7 in

Untitled (Poland), 2016Dried infinity roses, dried red berries, plastic hydrangeas, black ribbon, artist frame94 x 154.5 x 18 cm / 37 x 60 3/4 x 7 in

Untitled (Russia), 2016Dried infinity roses, dried red berries, plastic hydrangeas, black ribbon, artist frame94 x 154.5 x 18 cm / 37 x 60 3/4 x 7 in

WRJNGERFoundation de 11 Lijnen, Oudenburg, 2016Co-curated by Simon Castets and Hans Ulrich Obrist for 89plus

The exhibition title comes from the young adult book ‘Wringer’ by Jerry Spinelli, which tells the com-ing-of-age story of a boy refusing a small town’s tradition of pigeon shooting and the subsequent ‘wringing’ of the necks of pigeons to ensure death.

Bunny Rogers is part of the first generation of artists who grew up with the Internet as part of ev-eryday life. Her work is not specific to a medium, since she makes sculpture, installation, video, animation, etc., but rather is produced at certain points through digital processes (3D modelling, video editing, Second Life photography) and is in part exhibited and distributed through the in-ternet. Moreover, her works show a frequent use of elements and tools borrowed from her online presence. In her work, Bunny Rogers threads together uncanny representations of cultural icons, revealing something intimate about herself in the process. At the same time, she exposes societal norms and cultural memory for what they are: collective and constructed.

For Foundation ‘De 11 Lijnen’ Rogers has created a sculptural installation composed of ceramic pigeons displayed on the gallery floor. Alongside specially made curtains and flags, the exhibition includes five new mops using different colour variations with specially dyed grey yarn. The artist explains: ‘The mops exemplify ideas of grey morality, a lens in which to see the world, and the defi-nition of grey itself. Grey is the most important and all encompassing shade, the absence of what is distinguishable—the dissolution of that which is representable.’

Study for Joan Portrait, 2016Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305g

5 x (36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 x 12 x 1 in)

Study for Joan Portrait (Silence of the Lambs red), 2016Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305g

4 x (36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 x 12 x 1 in)

Mandy’s Piano Solo in Columbine Cafeteria, 2016Animated film, 13 min. 16 sec.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x__ROctj9nA

Columbine CafeteriaSociété, Berlin, 2016

My last show at Société was Columbine Library in 2014. I knew early on there would be a second part. I wanted the two main settings where the 1999 Columbine High School shooting took place to be acknowledged. But the ideas needed to be spaced out. I wanted it to be a subsequent experi-ence, even if you didn’t know about the first show or didn’t see it.

I think of the library as being slow and dark, filled with obstacles. That’s also how it looks in police photos. The cafeteria was open and well-lit, with tons of people and bombs hidden in duffel bags in plain sight. The cafeteria was more confusing. There’s not the same closure as in the library, where Dylan and Eric committed suicide.

The first show referenced characters from two TV series that I watched when I was younger: Joan of Arc from Clone High and Gaz from Invader Zim. I identified with them. I think of them as being each other’s sisters. They are both filled with anger. For Joan, it was complicated. The reality of hatred is that it’s often self-hatred. Joan expresses anger toward the person that she loves, so you wonder about whether it was love or hate, and about her capacity to love. I paired Joan and Gaz with Dylan and Eric, in part because I wanted to ask: What does female violence look like? How is it enacted? It’s usually just internalized forever.

In this show, the characters, the time, the temperature, and the things in the space have changed. Though Elliott Smith is still present. The project continues to serve as a memorial to him. And furniture still functions as a vessel of history. The chairs, tables, and bookshelves at Columbine experienced the events that happened and held onto them. In the Snowflake Special episode of Clone High, Joan becomes friends with a new character, who is unnamed, but who we understand to be Mandy Moore. At first, Joan is hostile to Mandy the same way she is to Cleo. In that way, her internalized misogyny is represented and questioned. But there’s finally a break when Mandy shows Joan the true meaning of Snowflake Day, which is appreciating friends and supporting one another. They go to a party where people are drinking alcohol, which is rare for cartoons. With tears in her eyes, Joan calls Mandy an angel. I’ve sometimes felt that way about female friends.

I was talking recently with my friend Leo about why I love things from my past more. Maybe it’s because you can’t love new things the same way that you loved things when you were younger, so you come to love new things through people, if you care about those people. The media makes it easy to love new things, but it’s actually closer to addiction. Loving people is hard.

The media leads to complicated feelings of sympathy and empathy. I have never been to Colum-bine, but the media made a big impact on me, and now I have strong feelings about it. Things like the internalized misogyny and alcohol abuse that I saw in the form of a cartoon were nevertheless part of the culture around me. In some ways, I think cartoons and theatre are good ways to talk about things like that. I don’t want to actually transport people to these places. They anyway have a place in our collective memory, which leads to subjective mourning.

Lady Dior Mattress, Death of Harlequin costume (outfit), 2016Soft-core foam mattress covered with artificial leather, knitted yarn (outfit)

84 x 174 x 14 cm / 33 x 68,5 x 5,5 in

Cafeteria set, 20161 custom-made table, 15 custom-made chairs, pastic, chromatic steel, wood

320 cm x 76 cm / 126 x 30 in

Cafeteria Wardrobe, 2016Wooden cabinet quilted with velvet custom-made pattern, aluminum, clothes hangers coated

with custom-made fabric, knitted yarn and cotton costumes, tinted bulletproof glass, balletshoes, dyed yarn mops, steel key, LED lighting system, rubber wheels

191 x 285 x 50 cm / 75 x 112 x 20 in

Cafeteria barre / Yellow portrait (Coward), Lavender portrait(Beta), Blue portrait (Anxious), Minkie Pie Love Lock (M + J), 2016

Chromatic steel / Oil on canvas, artist frames / steelDimensions variable

Untitled (Sad Chair II), 2015Wood, grey paint92 x 48 x 58 cm / 36 1/4 x 19 x 22 3/4 in

Stone is Not Stone, 2015Carved slate stone59 x 43 x 1 cm / 23 1/4 x 17 x 1/2 in

jrasjrMusée d’Art Moderne, Paris, 2015

Bunny Rogers’s three new mop sculptures represent a development in the series of so-called “mourning mops” that the artist has made in recent years. Rogers exhibited the first of such works in 2013. These works were titled “Self portrait (mourning mop)” (2013), “Lady Amalthea (mourning mop)” (2013), “Self portrait (mourning mop)” (2015), and “Allese (mourning mop)” (2015). For her project “jrasjr”, which accompanied the exhibition “Co-Workers, le réseau comme artiste” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Rogers produced eraser H (yellow), eraser M (red), and eraser T (blue)––each made of wood, aluminum, yarn, and water and dated 2015. On the aluminum pieces connecting the mops’ handles to their heads, each has been embossed with the silhouette of an evergreen tree and engraved, respectively, with the words “Memento”, “Heirloom”, and “Things Past”.

Rogers reference to this series of works as mourning mops further highlights their themes of isola-tion, nostalgia, subordination and repression. These are themes that recur in Rogers’s work. One example of that is Rogers’s presentation at Art Basel Statements in 2015, where the various grey–colored works referenced the tragic story and death of a character from the TV show Prison Break, who the artist felt a close affinity to. Prison serves as the link to “jrasjr” by way of the artist Jasper Spicero, a friend of Rogers’s who made a series of works called “The Prison Painter”, because “jrasjr” is intended as a play on the words “Jasper” and “eraser”. The way that language functions in these works should come as no surprise, considering Rogers’s prolific output as a poet, for example her well-known and highly sought-after first collection, Cunny Poems Vol. 1, from 2014.

Besides the actual use of language in these most recent mourning mops, all of the works exhibit formal characteristics that function metonymically and metaphorically––so in a way like language. The earlier ones each served as portrait of a person. These more recent ones, however, have a different relation to identity in that Rogers sees the three together as a team of “anonymous loners, socialized grey blobs”. For her, grey can stand for “the absence of that which is distinguishable, the dissolution of that which is representable, the rise of company and therefore safety.” A mysterious, circuitous arc of associations. Even the materials that Rogers used are sources of symbolism. The three types of yarn that the artist used to form the mop heads are sold under the names “Memento”, “Heirloom”, and “Things Past”––highly nostalgic language, which was important enough for the artist to communicate in the work by engraving it on the mops’ necks.

Though highly symbolic and representative, one could almost imagine the mourning mops actually being used as mops, evidence of how tightly bound they are to potential narratives and real-world contexts. Mops with this design are most often industrially produced and used by professional cus-todial staff at large corporations, federal buildings, schools, prisons, etc. In an art gallery or public museum like the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, they speak to work and workers often kept hidden from viewers given opening and closing times––work and workers also conventionally segregated by class, gender, and perhaps racial divides. Another artist who made a mop as a sculpture, Mike Kelley drew on his own experience working as a janitor before finding success as an artist (he was a janitor’s son who enjoyed upward socio-economic mobility through his education and work in art). Kelley’s “Janitorial Transcendence”, from 1980, which consisted of a broken-off mop handle turned upside down and affixed with a felt banner, foregrounded class politics, whereas other concerns central to both Kelley’s and Rogers’s work––socialization and repression, for example––are more signficant for Rogers’s mourning mops.

Rogers highlights the pairing of “use or abuse” embodied by the mourning mops. Their form, es-pecially their extra long handles, prompt themes of sex and sexual repression latent in the work. That narrative of repression––like the narrative of isolation and the themes of nostalgia and longing in general––exists at the uncanny collision of subject and object. This is one of the inventive oper-ations characteristic of all of Rogers’s mourning mops.

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Self - Portrait as clone of Jeanne d’Arc, 2014Fine Art Print on Hahnemühle PhotoRag Ultrasmooth 305 g, artist frame

36 x 31 x 3 cm / 14 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 1 1/4 in

Columbine LibrarySociété, Berlin, 2014

Columbine Library is Bunny Rogers’s first exhibition at Société.It takes as a backdrop the Columbine High School massacre, which occurred in Colorado, USA, onApril 20, 1999. That school shooting, which left 15 dead and 24 injured, resulted in a media frenzy.Fear spread across the country, as did doubts about a culture that creates a spectacle out of vio-lence and the use of firearms, to the point of normalizing them. Many wanted answers about whatmotivated the perpetrators, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. What emerged were portraits of dis-turbed teenage boys – as well as sobering insights into the pains of adolescence and the trauma of being in high school.

In the media, Harris was portrayed as deranged, and Klebold as prone to depression. They weredehumanized, described as monsters. Psychologically, they couldn’t be normal at all; they had to be aberrations, come untethered from social bonds. Any statement about identifying with them wastaboo, repressed, tantamount to homicidal or suicidal tendencies, impossible to reconcile with thestatus quo that so many had put faith in, that was supposed to keep kids safe and alive and in school.

But the culture industry – the media included – thrives on the capacity of spectator-consumers toidentify with the representations that it generates and regenerates. And there’s a kind of unspokenromance to tragic cases in particular, an attraction to the pain of others, an idolization of those whodie young (actors, musicians, artists; self-inflicted or not). Difficult though it may be to believe, that’sbeen the case with Harris and Klebold, too: Rogers discovered a subculture of teenage girls who obsess over them, using the Internet as a forum to express their empathy with the shooters as well as a sexual attraction to them. Not only does this challenge the media’s portraits of Harris and Klebold, it in fact forces us to face an inconvenient truth – that a death drive, rage, vulnerability, difficulties expressing oneself and integrating socially, and even a capacity for atrocities are cat-egorically human traits.

Several cultural icons crop up in Columbine Library, setting up a chain of identification always in re-lation to Rogers herself – the artist, the tie that binds. Perhaps more than we’d like to admit, there’ssomething that unites the perpetrators of a horrific school shooting, the victims, adolescent girls (sooften typecast as innocent, pure, and non-violent), a cartoon of an angst-filled teenage girl, one of arage-filled girl, a captive killer whale turned violent, a pacifist bull from a children’s book, and a musician who succumbed to addiction and depression. As Rogers, a kind of medium for the subjectivity of the young girl, threads together uncanny representations of these cultural icons, she reveals something intimate about herself. At the same time, she exposes societal norms and cultural memory for what they are: collective and constructed.

Clone State Bookcase, 2014Maple wood, metal, Limited-Edition Elliott

Smith plush dolls, “Ferdinand the Bull” thirdplacemourning ribbons, casters

246 x 309 x 61 cm / 97 x 121.5 x 24 in

Bunny RogersColumbine Library, 2014Text - Hannah BlackGraphic Design - Guillaume MojonProject Editor - John Beeson30 x 21 cm / 12 x 8 inEdition of 300Edition Société, Berlin 2014

Bunny RogersCunny, 2014Cunny Poem Vol. 1 represents a complete archive of poetry written from 2012-2014 and includes fourteen original illustrations by LA-based artist Brigid Mason.22 x 16 cm / 9 x 6 inEdition of 200

Bunny RogersMy Apologies Accepted, 2014Illustrations - Candice Burton and Brad PhillipsTexts - Bunny Rogers20 x 13.5 cm / 8 x 5 in

Lalka, 2013Plastic22 x 9.5 x 9.5 cm / 8 x 3 x 3 in

Afterlife are belong to me Sandy Brown, Berlin, 2013

Bunny Rogers and Benjamin Asam Kellogg are like figures of fine glass. The slightest touch and they may shatter. The pair suffer from a morbid acuteness of the senses. Bunny’s is worse for hav-ing existed the longer, but both of them carry this affliction. Any sort of food more exotic than the most pallid mash is unendurable to the taste buds. Any garment other than the softest, is agony to the flesh. Their eyes are tormented by all but the faintest illumination, and sounds of any degree whatsoever inspire them with terror.

Eighth anniversary (sadly), 2013Stock photo, plexiglass, mahogany, dyed roses5 x 5 cm / 2 x 2 in

Shades of bernyAppendix Project Space, 2013, Portland

Shades of berny include berry, burgundy, merlot, cabernet, maroon, and blood. All “wine colors” and any desaturated jewel tones occurring in the West Wing.

The home of one splintering scarecrow,a chair in pain.A loss of pigmentation due to natural sunlight,a frozen still life.

She is asking you to see her,Much like the iceblock, locked away in a freezer.

She is asking you to see her pugalo,And she smells good and she feels healthy.

You can kill the Beast. You cannot kill the Beauties.

An unusual chair sits in the corner between two walls: “Every day… every hour… think only of ru.”

Cherished ru quilt, 2013 “Princess” Beanie Babies, sterling silver pendants, cotton

75 x 75 cm / 29 1/2 x 29 1/2 in

Untitled, 2013Wool and poly satin198.5 x 149.5 cm / 78 1/4 x 58 3/4 in

If I Die Young 319 Scholes, New York, 2013

“If I Die Young” is an installation by Bunny Rogers and Filip Olszewski that addresses contem-porary understandings of childhood. Similar to the artists’ previous collaborative project, “Sister Unn’s” (2011-2012), in which they set up an out-of-business flower shop on a commercial avenue in Forest Hills, Queens, the work also explores loss.

The front gallery will consist of twelve black computer speakers spread along the walls, each playing the audio from a YouTube video in which a young girl (age four to sixteen) sings a cover version of the pop-country song “If I Die Young” by The Band Perry. Typically, the YouTube covers include a brief introduction by the girl, who announces her name and age and then proceeds to sing the song, which was written by lead vocalist Kimberly Perry from the point of view of a young girl who has died. Harmonized together in the gallery, the collection of voices takes on a different resonance.

In the rear gallery, the artists will display ten custom-made, twin-size blankets—each based on a watermarked photo taken from an Internet-based child modeling agency. The photos are replaced with the image’s average overall color, but retain the agency’s watermark logo, which is embroi-dered into the wool fabric.

BUNNY ROGERS

1990 born in Houston, TX / Works in New York, NY2012 BFA Parsons / The New School for Design / New York, NY2017 MA The Royal Institute of Art / Stockholm

Solo and Duo Exhibitions

2017Brig Und Ladder / Whitney Museum of American Art / New York

2016Columbine Cafeteria / Greenspon Gallery / New YorkWRJNGER / Co-curated by Simon Castets and Hans Ulrich Obrist / Foundation de 11 Lijnen / OudenburgColumbine Cafeteria / Société / Berlin

2015jrasjr / Co-Workers, le réseau comme artiste / Musée d’Art Moderne, ParisArt Basel Statements under the auspices of Société

2014 Columbine Library / Société / BerlinUnusuble chair / Important Projects / Oakland

2013 Afterlife are belong to me / Sandy Brown / Berlin Shades of berny / Appendix Project Space / PortlandIf I Die Young / 319 Scholes / New York

2012 Questions on Ice / Generation Works / Tacoma

Group Exhibitions

2017Being There / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art / HumlebaekAmericans 2017 / 89plus / Curated by Simon Castets and Hans Ulrich Obrist / LUMA Westbau / Zurichmoving is in every direction. Environments – Installations – Narrative Spaces / Hamburger Bahn-hof / Berlin

2016Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych. Intymność jako tekst / Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej / WarsawHigh Anxiety: New Acquisitions / The Rubell Family Collection / MiamiMined Control / as it stands / Los AngelesPure Fiction / Marian Goodman Gallery / Paris We Are All Traitors / Hessel Museum of Art / Annandale-on-Hudson

2015Unorthodox / The Jewish Museum / New York89plus: “Filter Bubble” / Luma Westbau / Zurich Anagramma / curated by CURA / Basement / RomeThe Heart is a Lonely Hunter / YARAT Contemporary Art Centre / BakuWelcome You’re in the Right Place / Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Foundation / Turin

Studio Program Exhibition / Queens Museum / New YorkDoes Not Equal / W139 / Amsterdam A Sentimental Education / Galerie Andreas Huber / ViennaMilk Revolution / American Academy / Compiled by CURA / Rome

2014 Warez / Carl Kostyál / LondonPrivate Settings / Art after the Internet / Museum of Modern Art / Warsaw Today : Morrow / Balice Hertling / New YorkJoan Dark / Western Front / Vancouver Significant Others (I am small, it’s the pictures that got big) / High Art / ParisFool Disclosure / Henningsen Gallery / CopenhagenArt Post-Internet / Ullens Center for Contemporary Art / BeijingRaster Raster / Aran Cravey / Los Angeles

2013 Random House / Arcadia Missa / LondonChambers at The Wrong: New Digital Art Biennale / thewrong.orgNational #Selfie Portrait Gallery / Moving Image / LondonMinku, Are You Here? / Springsteen / BaltimoreMawu-Lisa ii / Courtney Blades / ChicagoDouble Indemnity / Cornerhouse / ManchesterLonely Girl / Martos Gallery / New YorkShades of Berny / Appendix Project Space / PortlandUncanny Visions IV / Aux Performance Space / PhiladelphiaUniforum: A Place of Nonconsequence / Stamp Gallery at UMD / College ParkEthira / Arcadia Missa / LondonInstitute Bianche / Library + / London4. / CEO Gallery / Malmö Decenter / Abrons Arts Center / New YorkTrū Romance / Picture Menu / New York Open Shape / Kompan Playground / Wichita 2012Infamous Amplification / hpgrp Gallery / New YorkSex Life / Bodega / PhiladelphiaPrrrsona / Little Berlin / Philadelphia

2011Screen Play / 25 E 13th Street Gallery / New YorkMawu-Lisa / New Gallery London / LondonGUT FLORA / 25 E 13th Street Gallery / New York 2010 REAL/LY/FAKE / 25 E 13th Street Gallery / New York

Performances, Readings and Screenings

2018Poetry reading / Hauser & Wirth Publishers, Conversations in Contemporary Poetics: Precious Okoyomon and Bunny Rogers / Hauser & Wirth / 22nd Street / New York (forthcoming)Poetry reading / Codex / New York (forthcoming)

2017Poetry reading / WRJNGER / Swiss Institute / New YorkPoetry reading / Molasses Books / New York

Poetry reading / The Shed / New York

2016Poetry reading / We Are All Traitors / Hessel Museum of Art / Annandale-on-Hudson

2015Lecture / Communicating the Archive : Inscription / University of Gothenburg / GothenburgPoetry reading / Konstfack University of Arts, Craft and Design / StockholmPoetry reading / Sunday Sessions: It’s Not What Happens, It’s How You Handle It / MoMA PS1 / New YorkPoetry reading / Rapport de face à face / Hester / New YorkPoetry reading / Performa Poetry Series / What if someone told u you were significant ? / A+E Studios / New YorkPoetry reading / “My Apologies Accepted” / St. Mark’s Bookshop / New YorkReading and screening / Poetry will be made by all! / Moderna Museet / StockholmPoetry reading / Filter Bubble / Prospectif Cinéma / Centre Pompidou / ParisBook Launch and Reading of “My Apologies Accepted” / KGB Bar / New York

2014Poetry reading / Wicker Girls / Curated by Rachel Lord / American Medium / New YorkPoetry reading / Columbine Library / Musical accompaniment by Joseph Beers / Societe / BerlinPoetry reading / Beers and Brigid Mason / Issue Project Room / New YorkPoetry reading / A Striving After Wind / Musical accompaniment by Joey Nikles / Unnameable Books / New YorkPoetry reading / Rumours / Model Projects / VancouverPoetry reading / Otherless Walls / Queens Museum / New YorkPoetry reading / No Petals Left on a Dying Rose / Musical accompaniment by Nathan Whipple / Unnamable Books / New YorkPoetry reading / Hero Systems / Molasses Books / New YorkPoetry reading / To Fade and Spill Out (And Look at Another’s Whole) / FJORD / PhiladelphiaPoetry reading / Blackmail Series 1 / Mellow Pages Library / New YorkPoetry reading / New Agendas / Macie Gransion / New York

2013Poetry reading / Letter to Jane / Gothenburg University / Skogen / GothenburgPoetry reading / Lonely Girl Presents: An Evening of Readings / Martos Gallery / New YorkPerformance and poetry reading / gURLS / Transfer Gallery / New YorkReading / Alone with Other People / LaunchPad / New YorkPerformance / I’d give anything for another whiff / Novella Gallery / New YorkPerformance / CON/HAL Live-Con / Wayward Gallery / LondonPerformance / being(s) connected / Oslo House / LondonScreening / Monkey Town 3 / Eyebeam / New YorkScreening / G1RLZ NITE / The DL / New YorkScreening / The Embassy Sweet Sensation Tour / Inkonst / Malmö

2012Performance / Company Safety / Silvershed / New YorkScreening / Heavy Meta / Trinity Square Video / Toronto

2011Performance / The Real Boob v. 2.0 / Double-Double Land / TorontoScreening / Boxing Day Presents / Toronto

2010Performance / Diane’s Circus / New York

Bibliography

2017Molly Langmuir, Trish Deitch and curated by Carly Leitzes / ELLE WOMEN IN ART: WHO TO KNOW, LOVE, COLLECT / Elle US / DecemberRoberta Smith / What to See in New York Art Galleries This Week / The New York Times / Septem-berCaroline Goldstein / Processing Trauma: Artist Bunny Rogers on Using Her Work to Explore the Columbine Massacre’s Lingering Impact / artnet news / August Anne Doran / Bunny Rogers: Brig Und Ladder / Time Out / AugustJack Gross / Bunny Rogers Whitney Museum of American Art / Flash Art / August Bunny Rogers: Brig Und Ladder / The New Yorker / July‘Brig Und Ladder’ by Bunny Rogers at Whitney Museum of American Art, New York / BLOUIN ARTINFO / JulyJospeph R. Wolin / Bunny in the Headlights / Vice / JulyJohanna Fateman / Previews / ARTFORUM / Issue 55 / May / p 144Dayna Evans / Fending Off the Apocalypse With Blingee Art / NYMAG / AprilEileen Isagon Skyers / Code is Amoral: An Interview with Bunny Rogers and Nozlee Samadzadeh / sevenonseven.art / April5 ARTISTS ON OUR RADAR / novellamag / AprilAlex Greenberger / At Seven on Seven Conference, Artists and Technologists Unite to Ponder Politics, Sexting, Fake News, and More / ArtNews / April

2016James Tarmy / Investing in Art? Here Are 10 Young Artists to Watch in 2017 / Bloomberg / De-cemberConnie Kang / Bunny Rogers: Columbine Cafeteria / LEAP / Issue 40 / August / p 200 - 204Nasrin Leahy / Take This Gum and Stick It at Ellis King / Art Viewer / AugustEmily Steer / Now Showing: Take This Gum and Stick It / Elephant Magazine / AugustJulie Boukobza / Pure Fiction at Marian Goodman / Contemporary Art Daily / JulyBunny Rogers / artlover magazine / Issue 28 / June / p 38 - 42Bunny Rogers at Greenspon / Contemporary Art Daily / JuneWhat to see in New York, Art Galleries This Week / Bunny Rogres, Columbine Cafeteria / The New York Times / June Brian Droitcour / Exhibitions The Lookbook / Bunny Rogers at Grenspon Gallery / Art in America / JuneExhibitions / Bunny Rogers at Grenspon / Art Viewer / June Casey Lesser / 21 New York Gallery Shows Where You’ll Find Exciting Young Artists This May / Artsy / May Diane Solway / Meet Artist Bunny Rogers, Child of the Internet / W Magazine / May Gloria Cardona / The Top 3 Art Event In Berlin This Week / Coliumbine Cafeteria / sleek / May Ryan Steadman / Weekend Edition: 7 Things To Do in New York’s Art Worls Before May / Observ-er / May 10 Art Events to Attend in New York City This Week / Opening: Bunny Rogers at Greenspon / Art News / May Andrew Nunes / A Haunting Exhibition Re-examines Columbine’s Collective Trauma / The Creator Project / June Artist Rebuilds Columbine’s Cafeteria In A Sobering Take On Gun Violence / The Huffington Post / June Critics’ Pic / Bunny Rogers at Société / ARTFORUM / April Timo Feldhaus / Real Time Column / Spike / April Geoffrey Cruickshank-Hagenbuckle / Class Plus Sass: Bunny Rogers’ Columbine Cafeteria / Hyperalleric / May

2015Burke Harry / Page Break / Texte zur Kunst / Issue 98 / June / p 118 - 123Mugaas Hanne / Bunny Rogers / Kaleidoscope / Issue 24 / May / p 58 - 59

Fateman Johanna / Women on the Verge / Artforum / Vol. 53, No. 8 / April / p 218 - 224Farkas Rósza Zita / Bunny Rogers / Cura Magazine / Issue 19 / March / p 124 - 137Ghorashi Hannah / The internet-generation poets who are making the web a little weirder / i-D / MarchCarmichael Seth / Get ’em now, while they’re hot? / The Art Newspaper / Issue 264 / January

2014Mousse Magazine / Bunny Rogers Four poems / Issue 46 / December / p 156Beach Sloth / The Beachies / Beach Sloth / December Galperina Marina / The Year’s Best Art On The Internet / Fast Company / DecemberDent Beau / Bunny Rogers, Hannah Black + the ‘Unusuble Chaire’ / Aqnb / November Burke Harry / Bunny Rogers / Flash Art / November / p 47Archey Karen / Bunny Rogers - Columbine Library / Art Review / October issue / p 155 Pico Tommy / Five On It: Monica McClure / Hey, Teebs! / October Hohmann Silke / Bunny Rogers / Watchlist / Monopol / October issue / p 30Vasey George / Bunny Rogers / Review / Frieze / Issue 166 / SeptemberNava Nayeli / Bunny Rogers / Little Paper Planes / August 9 years. Fotoperformance en Second Life por Bunny Rogers / Hysteria / AugustPerlson Hili / Bunny Rogers / Critics’ Picks / Artforum / August Jarrison Bryan / Bunny Rogers Ryder Ripps R. Lord }{ American Medium / SPF 100 / August Bess Gabby / 10 new Indie books and zines that we love right now / Papermag / August Folks Eva / Bunny Rogers @ Société reviewed / Aqnb / August Messinger Connor / “Cunny Poem Vol. 1” by Bunny Rogers / Reviews / HTMLGIANT / JulyConnor Michael / The seven best net-art “things” right now / Dazed / JulyTully Dierks, Stephen / A Cunny Poet’s Beautiful Book / Fanzine / July Phillips Brad / Bunny Rogers, Cunny Poem Vol. 1 / The Art Book review / July Pearrlszine / Bunny Rogers, Occupational Postion / Pearrls / July Beach Sloth / Cunny Poem Vol. 1 by Bunny Rogers / Beach Sloth / July Veckans dikt 9: ”exit house Sobieski sob story” av Bunny Rogers / Bear Book / July Burke Harry / We Are All Traitors / Mousse Magazine / No. 44 / JuneGalperina, Marina / Here Is The “Cunny Poem” Book By Bunny Rogers / Animal / June Bunny Rogers, Occupational Position / Arcadiamissa tumblr / MayBlack Hannah and Coburn, Tyler / On Affectionate Sabotage and Exemplary Suffering: An Audio Guide to IsaGenzken / Rhizome / February MutualArt / 14 of the Most Anticipated Museum Shows of 2014 / HuffPost Arts & Culture / January Beach Sloth / No Petals Left on a Dying Rose: A Reading for Oskana / Beach Sloth / January

2013Burke Harry / Apologies / West Space Journal / Issue 1 / Winter Archey Karen / Lonely Girl: Martos Gallery / Frieze / Issue 159Allegrezza Lauren / Currently Crushing on Bunny Rogers / Blue Stockings Magazine / October Farkas Rózsa / Exhibitionism, or Perhaps Rejection / EITHER/AND / October Cunningham Erin / The Art of the Selfie / The Daily Beast / October Reznik Eugene / Off Your Phone and on View: The National #Selfie Portrait Gallery / TIME Light-Box / October Kirsch Corinna / The Digital Art World’s Secret Feminism / ARTFCITY, October Alvarez Ana Cecilia / The Artists of gURLs / The Daily Beast / September White Rachel Rabbit / Oh gURL: It’s so good to finally meet u IRL / Rhizome / September Owens Ashleigh / Cornerhouse Manchester: Double Indemnity / Tusk / September Galperina Marina / Brutal Fairy Tales, Sexualized Innocence, and Russia: Bunny Rogers, Shades of berny / Animal / June Burke Harry and Farkas, Rózsa / Postscript (P.S. Forever) / Mute / June Burke Harry / Love Letter to Bunny Rogers / Dazed / May Manousakis Dimitrios / Stepping in the Internet Shit is Inevitable / Bushwick Daily / April Galperina Marina / Children as Internet Things for Adults: ‘If I Die Young at 319 Scholes’ / Animal / MarchChayka Kyle / Fleeting Youth, Captured in YouTube Videos and Modeling Photos / Hyperallergic

/ March McHugh Gene / Lingua Photographica / Aperture / March Le Lap / Under My Colors / WOW HUH / Spring 2012King Abby / Prrrsona / Title Magazine / September Phillips Brad / Bunny Rogers / Millions Magazine / Issue 1 / SeptemberDoulas Louis / Artist Profile: Bunny Rogers / Rhizome / May

2011Troemel Brad / Friday Interview with Bunny Rogers / Slow Content / March

Publications

2017Flowers for Orgonon / Edition Société / BerlinWrjnger / De 11 Lijnen

2014 My Apologies Accepted / Civil Coping MechanismsColumbine Library / Artist’s book / Edition Société / BerlinCunny Poem: Vol. 1 I Love Roses When They’re Past Their Best / Pwr Studio for Test CentreMy Apologies Accepted: An Excerpt / Atticus Review

2013 Loyalties / Übergang / Issue #01 / Edited by Will Furtado and Kevin Junk 2012Future Caves / Vol. 1 / Piet Zwart Institute / Edited by Olivia DunbarFour Poems / Illuminati Girl Gang / Vol. 2 / Edited by Gabby GabbyLife in the Cell / Issue No. 1 / Edited by Mauricio Vargas

2011 The Owners’ World / Pool / November Issue / Edited by Louis Doulas

FEATURE

Elle USELLE WOMEN IN ART: WHO TO KNOW, LOVE, COLLECT

The Media Sampler: Bunny Rogers

When Bunny Rogers got to Parsons in 2008, she discovered the labored-over outfits she enjoyed creating put her well out of step with her fellow students. So she made a mental switch from fashion design to fine arts, thinking, “There I’d be able to do whatever I wanted,” she says. And how. Today she’s part of a generation of artists who are as likely to produce a website as a sculpture as a video as, in Rogers’s case, environmental installations that incorporate all of the above.

By the time Rogers received her MFA from the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm last spring, she’d been picked up by the innovative German gallery Société Berlin and had begun a rapid art-world ascent via layered exhibits that feel at once cryptic and diaristically intimate. In a solo show at the Whitney earlier this year, for example, the final installment in a trilogy of works focused on the Col-umbine shooting featured (a) a video in which characters from MTV’s early-aughts animated show Clone High performed “Memory,” from Cats, in Russian; (b) three chairs covered in shotgun holes; and (c) a stuffed-animal version of the violent SeaWorld whale Tilikum. “I’m interested in the way the media ascribes compassion to some entities but not others,” Rogers says. “And how tragedy gets mythologized.” Entering the installation felt like observing a person’s interior world made manifest, with obscure patterns and repetitions in interlocking layers.

“The experience and how it affects you is the key thing,” says Mathias Ussing Seeberg, curator at Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, where Rogers is part of a group show that runs until February. “She’s looking at how mourning can become something for the living to thrive in, and death something for the living to live through. She incorporates adolescent themes, but it’s not youthful work.”

Molly Langmuir, Trish Deitch and curated by Carly Leitzes

Originally published in Elle US, December issue, 2017

INTERVIEW

artnet news

Processing Trauma: Artist Bunny Rogers on Using Her Work to Explore the Columbine Massacre’s Lingering Impact

We spoke to the artist about her first major museum show at the Whitney.

If you haven’t yet heard of Bunny Rogers, take note. At only 27, with the ink still wet on her MFA diploma from the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Bunny Rogers is poised to join the ranks of internationally acclaimed artists such as Anne Imhof and Ian Cheng, with the full faith and credit of a solo exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

Since graduating from Parsons School of Design in 2012, Rogers has put forth a trio of works that focuses primarily on the Columbine High School Massacre, where in 1999 Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold went on a shooting rampage, resulting in 15 dead (including Harris and Klebold) and 24 injured.

In two previous exhibitions, “Columbine Library” (2014) and “Columbine Cafeteria” (2016), Rogers reconstructs these main sites of trauma—the cafeteria and library were the two central points of the school shooting. These installations often incorporate found objects such as school library chairs and cafeteria tables, alongside plush toys and school bags inspired from the MTV’s cartoon show Clone High. The artist also makes animated videos featuring some of the characters of Clone High placed inside different areas of Columbine High School.

In her first major museum exhibition, “Brig Und Ladder,” now on view at the Whitney Museum in New York, Rogers implements the visual markers she defined in the previous two shows to com-plete the third segment of her trilogy. The show opens with an animated video, A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium, playing in front of a row of auditorium seats. On screen, three stylized Clone High characters perform a Russian rendition of the musical number “Memory” sung by the former glamour-cat Grizabella in Cats. While the song and the musical are often maligned as schmaltzy, the nostalgic ballad is not only a personal favorite of Bunny’s, but also functions as a sign for the character’s fall from grace.

Recently artnet News sat down with the artist to discuss her new work and her fixation with the infamous tragic event.

AN: When did you start making art seriously?

BR: The art that I’m making right now, I would say I started making maybe two years into college, probably when I was about 20. But I’ve always been interested in making things: clothing, websites, drawings, poetry. I wanted to be a fashion designer, although I didn’t know what that meant at the time. In my head I thought, “Oh I want to make one-of-a-kind beautiful costumes.” Then I got into Parsons, which was the best school to go to for fashion design, and it wasn’t what I thought it would be. And my boyfriend at the time—someone I’ve collaborated with a lot—made the suggestion that I go into fine arts, because you can do whatever you want. That was probably one of the most important moves I ever made. So I’m indebted to him.

AN: So after you graduated from Parsons in 2012, you later went onto graduate school at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, where you just completed your MFA in 2017. When did you have your first show?

BR: In 2013, I did a residency program at Appendix Project Space in Portland, Oregon. It was an art space that operated out of a garage. I did a show called “Shades of berny.” But the very first solo show I did was “Questions on Ice” at Jasper Spicero’s Generation Works, which took place in his mother’s foreclosed apartment, in Tacoma, Washington.

AN: It is really impressive that you have this platform at the Whitney, right as you finish graduate school. How did the show at the Whitney “Brig Und Ladder” come together?

BR: I met an assistant curator at the Whitney a few years ago. She and I started talking, very ca-sually, and kept in touch over the years. After a while, they asked me if I wanted to do the show. It was a big surprise for me.

The experience has been intense and overwhelming, but also really exciting. I’m really happy that I got to have this space to myself, because I often think of artworks in the context of an installation. So to have my own room was really freeing. I basically got to do exactly what I wanted to do, which was really ideal.

AN: In two recent exhibitions, “Columbine Cafeteria” and “Columbine Library,” the titles reference the Colorado school shooting from 1999, perhaps the first instance of a national tragedy connected to a school shooting. And in the Whitney show, “Brig Und Ladder,” you use some of the visual sym-bols from those works—the animated character playing piano, for instance, and the mops. Why is this event a touchstone for your work?

BR: It fully saturated the media. The Columbine shooting affected me in ways that I wouldn’t even fully understand the gravity of until I was older.

AN: I also remember noticing the communal nature of the grieving for this horrible tragedy. It was an isolated incident, but it felt like it really impacted our entire world. But like many of us, we were mourning this event through the media. I also felt that way on September 11th.

BR: Exactly, on television. It was ubiquitous. Media shifted to where now you choose the channel you want to follow. When I was younger, it felt like something happened and you saw it everywhere. The footage for the Columbine shooting is so clear in my memory. I’m able to recall it with such visual accuracy. It’s as if it exists in my head as a reel. I want to allow for complex ways of viewing and articulating a trauma. Because otherwise, you can never really pull apart your feelings toward something that has happened, and eventually relate it to others. Talking about trauma is going to be problematic. It touches places within you that you don’t even know about. And things bubble up. You can ignore it, and keep swallowing it—I definitely still do that all of the time. But a lot of reactions and ways of registering things are automatic. For me, this is an attempt to understand the processing of trauma.

AN: One aspect of the so-called “trauma culture” is the way that strangers respond to tragedy. For example, people will often leave teddy bears and notes for victims. There always seems to be a fine line between actual mourning and the fetishization of trauma and grief, especially en masse. Is that an aspect of visual representation of trauma that you consider?

BR: Absolutely, I’m very aware of it. Especially when I first started researching and reading as much as I could about Columbine—all of the books that had been published, and the countless online message boards where people are still discussing Columbine, even 20 years later. This event was incredibly devastating for so many people. And some people are still trying to figure out, factually, what happened, which is amazing to me. You can have the exact time line, but still feel like there are holes.

People fixate on the endless material to look through; the notebooks and the thousands of pages of police reports. But on the other side of the spectrum, there are people who are most concerned with Dylan and Eric. And that could be a somewhat romantic, sexual attraction. I don’t even think that some people recognize it as such. They just seek out a better understanding of these two peo-ple that committed this act of violence and then killed themselves. So it may come from a romantic interest, but also an intellectual interest, where it is more about the psychology of children and teenagers that commit these acts of violence.

I feel like looking into the online responses—because it has had 20 years to accumulate—gives

you a really good sense of how Columbine has registered for so many people, including people that it directly affected. Blogs about Columbine that are run by people who were involved in some way exist too. Just this past year, Dylan Klebold’s mother released a book detailing her sorrow over what her son did, and the burden she still feels. And that’s 20 years later. So I think for these types of tragedies, you can’t underestimate the longterm traumatic effects.

AN: Of course Columbine is the first thing people hear or see in regards to your work, but there are also other things that inspire you as well. On the audio tour of the Whitney show, you talk about Clone High, a short-lived animated TV show that illustrated essentially famous women from histo-ry, but reimagined as high school girls. These archetypes of powerful women are reduced to an animated version.

BR: Flatness, exactly. When I was a kid, and even now, I connect very deeply with television, and characters on TV, as well as in books and in movies. Those characters were real to me, the way that my Neopets were real to me. I wished that I could visit Neopia, and why couldn’t I. So I ended up writing about it, and that ended up fulfilling a desire for me. It wasn’t completely satisfying, but it helped me to understand how to coalesce this identity that I feel like I should have, or should embody, completely.

AN: You work a lot with technology, using animation and referencing websites and computer games. But you also incorporate different materials such as plush toys and found objects. Is this a conscious decision on your part, to juxtapose these two worlds, the digital and the material?

BR: The end goal is visualizing a world, specifically, my inner world I guess. And I’m always seeking to make that happen. The palette in “Brig Und Ladder,” and some of the symbols, like the flags, are very important to me, and make references to a specific relationship that I had. I’ve spoken a lot about this “perfect audience of one.” It’s almost a reflection of me goes to see the show, and gets every reference, knows exactly what I’m saying, and feels my sorrow. I’ve realized that people can still register the loss, without knowing exactly what it is that I’m describing.

I read something recently where someone said the work looks “just dated,” which is interesting to me, because it doesn’t look dated to me. I’m using things that are currently of interest to me. But I understand how someone sees it as dated. My hope is that even with those things, you can swap them out—the Clone High characters, for instance—for characters that you connect with. They’re basically just stand-ins for me too. So my hope is that the feelings register, regardless.

Caroline Goldstein

Originally published on: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/bunny-rogers-interview-1038647, Au-gust, 2017

FEATURE

The New York TimesWhat to See in New York Art Galleries This Week

Bunny RogersWhitney Museum of American Art

The artist Bunny Rogers, who was born in 1990 and is a published poet, has received a lot of atten-tion in a short amount of time. Now she is having her first museum exhibition in the United States, a large video installation titled “Brig Und Ladder” that meditates on the pain of teenage alienation.

Like many of her contemporaries, Ms. Rogers works with an extended back story. But the haunting quality of her animated videos and the impressive physical precision of her objects can be alluring, as often happens with the works of other cosmologically minded artists — like Matthew Barney, for example, or members of a younger generation, like Kaari Upson and Helen Marten.

At the center of Ms. Rogers’s cosmology is the massacre at Columbine High School in 1999, its spectacularization in the media and the disturbing sympathy online for the shooters, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, especially among young women who called themselves Columbiners. Around this charged center swirl references to television shows like “Clone High,” an animated parody of overly earnest teen dramas; the melancholy music of Elliott Smith; and Tilikum the orca at Sea World who killed three people. And throughout floats the question of the outlets that teenage girls, as opposed to boys, find for anger and fear.

Ms. Rogers explored the tragedy in “Columbine Library” (2014) and “Columbine Cafeteria” (2016); “Brig Und Ladder” concludes the trilogy. In a theater setting, it starts with a slightly tedious video titled “A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium,” in which three sad young women — including Joan of Arc, from “Clone High” — perform “Memory,” the soppy hit from “Cats,” slowly, lugubriously and in Russian. It could easily be a memorial service. A large stuffed-animal body pillow of Tilikum lies beside the screen, offering comfort. A doorway with red velvet curtains leads backstage to three sets of sculptures: mops for cleaning up blood; office chairs seemingly gouged by bullets; and elegant ladders, a means of escape or a stairway to heaven.

Additional pieces include “Memorial Wall (fall),” a stretch of chain-link fence festooned with red leaf-shapes that evoke room fresheners, and “Lady train set,” a large painted wood version of the perky young neighbor, named Lady, from the “Thomas & Friends” series. Her cheerfulness seems poignantly out of place.

Roberta Smith

Originally published on: https://nyti.ms/2jLpnbR, September, 2017

INTERVIEW

I-DBunny Rogers wants you to know she ‘acknowledges your hurt’

In her intimate solo show at the Whitney Museum, the artist meditates on mourning, with help from an MTV cartoon character and the ‘Cats’ soundtrack.

Stepping into a Bunny Rogers exhibition has the effect of a teleportation device, though the realm you are transported to can feel equally visceral and enigmatic. It’s not totally clear where you are, but it’s certain you are now somewhere else. Over the past decade, the 27-year-old multimedia artist, poet, and performer has created immersive installations that are so thick with ambience you can practically pocket the aura. For instance, Columbine Cafeteria (2016) featured, among other things, a room filled apple-scented votive candles and faux snowfall as a character from the ear-ly-aughts MTV show Clone High performed a cover of a Elliott Smith song in a 3D-rendered video loop. Despite her ability to manifest a pungent vibe in each of her exhibitions, the environments she constructs are cryptic and intuitive. Her personal ties are purposefully blurred.

In Brig Und Ladder, Rogers’s current exhibition on view at the Whitney and her first major museum show, she entwines shared cultural memories like the Columbine High School massacre with a “personal constellation” of pop culture references and hat-tips to private experiences that have informed her identity. The work, which includes sets of three “self-portrait” mops, three spotlit lad-ders, and three recreations of chairs from the Columbine Library sporting shotgun holes, is installed in both a model of Columbine’s auditorium and a “backstage” area of her own imagining. Rogers was nine-years-old when Columbine happened, and while she was living in Texas at the time, the tragic event coincided with a formative phase of her childhood.

The avatar-like characters that appear throughout the first-floor gallery space function as stand-ins for her friends, family, and herself. They also serve as easter eggs, with certain objects and materials (Precious Moments plush toys, ribbons, Jelly Pen ink) nodding to personal history as well as past exhibitions. (In Brig Und Ladder, Joan from Clone High sings “Memories” from Cats in Russian in a new 3D-rendered video loop.) All together, the installation adds layers to Rogers’s ever-expanding visual vernacular, while inspiring viewers — at least this one — to sub in their own avatars and meditate on loss, mourning, and ultimately connection.

You’ve explored Columbine and concepts related to mourning in many different works. What push-es to keep grappling with these same themes?

A lot of the time, I’m thinking about relationships with people in my life — relationships that are ongoing, or relationships that have failed, or have seemingly failed. I don’t see an end to any rela-tionship I’ve ever had. Similarly, I don’t believe that it makes sense to ascribe mourning as having a beginning and an end. I’ve always carried this sensation of loss, and it took me a long time to realize that it was an affectation. That it was something I was imbuing in everything I was seeing, in every relationship I was entering.

You once said that you view the world through a sad lens, and as a result things reveal themselves in a way that’s the most honest or beautiful. Do you still feel that way?

I don’t want to say “most beautiful,” but what I have found is that when I feel like I’m most reflecting the characteristics of my depression — slow, introverted, maybe more careful, maybe less opti-mistic or something — it makes me feel more connected to other people, even if on an interactive level it is alienating.

Why do you use Columbine, in particular, as a recurring lens to examine mourning and loss — es-pecially when there have been many other school shootings in recent years?

This was a shooting that happened at a formative time for me. I was nine and living in Texas. The three years I spent there I remember vividly. It’s where I started playing Neopets, and where I met my best friend of my childhood. I can’t really explain why memories fit together for me in the way they have, but I guess in my artwork it’s me trying to assemble them so I can create some kind of record, or departure point.

I read something [about how memory works] a long time ago and it really stuck with me. Each time you recall a memory, it changes or shifts. That’s not taking into account how much we lie to our-selves and how skewed our perceptions are to begin with. We’re all delusional, whether or not we want to be. And even if you work against it, you can’t escape your blind spots; if anything, working against them might have different types of delusional consequences.

When you try to correct something you see as a character flaw, it’s difficult not to overcompensate, and then again, and then again, and the process is like Tetris. The game ends and by that time people have been hurt and you’ve adjusted, but in what ways you’re not exactly sure, though you tried your best, and you’re stuck.... and the new game starts up and you feel better equipped but the pieces have changed and the problems are different. Anyway, I see my artwork like that — like a Tetris metaphor about stacking blocks and it getting harder to see the bottom. So I can’t purely recall something.

Do you view Columbine as a pathway to revisit that formative time of your life in Texas?

Maybe. In the moment the Columbine massacre happened, I can recall the media on television, but I don’t remember how I felt about it. I don’t remember much more than confusion. It wasn’t until later on (and after going through high school) when I began researching Columbine and revisiting its initial documentation, that the gravity of what had occurred actually resonated: A small-town tragedy so devastating it swallowed a nation whole and the complete (moral, political, ideological) destabilizing that inevitably followed, resulting in an open question regarding the immeasurable reach of loss — be it individual, collective, communal, or national. [Columbine] was at an age when I felt alien. I didn’t feel like a person. I definitely didn’t feel like I was a girl. I felt perverse and that there wasn’t a place for me.

Did that friendship make you feel like there was a place for you?

The way I think about this relationship with my friend [from Texas] is relatively unusual. When I was 10, my family moved to New York, and it decapitated this relationship, but also encapsulated it in this idyllic way. My moving kept it in this vacuum of youth. As I got older and started participating in new relationships, I was constantly comparing those relationships to this one best friend I had, and I struggled with issues of loyalty. Why can’t people just have one person, and why aren’t they satisfied with one person?

I remember talking with this same friend from Texas a few years later, and she had made new friends with me having gone. And I had not made any new friends in my new school. I felt betrayed. When I think of [the Columbine shooters] Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, I can’t help but see them memorialized with each other, as a relationship between two people. You can’t think of Dylan’s death without Eric’s death. I think that’s a fantasy for a lot of people, especially a lot of young peo-ple: to remove the fear of being alone in life and in death. We go to extreme lengths to ensure that we don’t face death by ourselves.

Is there a parallel between struggling to move past that time in your life and the exhibition’s looping video, which is like a static memory repeating itself?

In short, yes. The animation is a looping performance, and the sculptures are static. The chairs [in the back room of the installation] are damaged, but there’s no indication of what they looked like before, or if they were meant to be fixed or replaced. For instance, Columbine Library was com-pletely redone after the massacre.

You watch a memory like a movie, or a clip from a movie, but you’re outside it. Maybe it’s fuzzy and whole, or clear and segmented. You go behind it, “backstage,” and all the pieces — these affected sculptures — are isolated and suspended. They are suspended in shadow. And you can still hear the audio starting over, but it’s quieter. It’s repeating itself, and a song stuck in your head is men-acing, not pacifying — even if it’s “Memory” from Cats, even if it’s in an unfamiliar language, even if it’s your favorite character’s theme song. You love that character for weird reasons and you connect to her theme about surrendering to death, even though you are eight-years-old.

I watched Cats on VHS at least 100 times. I knew all the lyrics and choreography to all the songs. It would end and I would rewind it and watch it again. But I had this process of consumption with everything. I still practice it. It’s a part of me. It used to clearly happen with things I knew I loved or obsessed over. But I tried making a list when I was 17 — “Everything I’ve Ever Been Addicted To” — and it never ended. I couldn’t draw a line between compulsive and non-compulsive behavior. The nature of addiction kept broadening, in my life and in my head.

Making artwork helps me organize thoughts and feelings that would otherwise repeat endlessly if left internal. I’m so afraid of forgetting. If my thoughts and feelings, and especially memories, are erratic and untrustworthy, in artworks they can, by my logic, be pinned down. And if I succeed in that transference, momentarily I feel a resolve.

You’ve described your mop works as “self-portraits” in the past. Do you view the ladders similarly? The ladders are portraits, and one of them represents me. Also, there’s ladders, bridges, and trains in the exhibition. Bridges and ladders are means of connecting to separate places. The train is a means of getting to a place, but it’s not on tracks, it’s not moving around the exhibition. It’s some-thing that’s non-functioning and static, too.

I left the exhibition with the feeling that it was simultaneously extremely personal and also very cryptic — and you seem intent on keeping it that way. I’m curious about how that tension makes you feel.

It makes me think about how certain people who exist for me in this installation have been present in many artworks I’ve made. It’s objectifying to make work about someone you care about but can’t communicate with anymore — it kind of makes me feel like it’s an unwanted gift to these people. I think it makes sense that the people are represented with objects and avatars [in my work]. And there are also characters I attach to, so that’s why they reappear, but with them it’s more like dis-placing feelings.

It’s complicated to make absence into artwork that’s not objectifying. You’re creating things to fill these spaces. Is it really empty, is it really absence?

There is so much left behind. Presence is the slowest dissipating substance. When someone leaves your life, someone you’ve had an intimate relationship with... even if they stop talking to you cold and you never talk again and never see them again, that doesn’t mean it’s resolved. I feel like those remnants were the basis for making these works.

Can you elaborate on that more?

I think all my artwork is me trying to connect with at least someone. Regarding being somewhat cryptic, I mentioned that I have this idea of the perfect audience — someone who sees the work and understands everything, immediately. Without explanation, this person sees it and is left with this feeling that they understand: I see you, you see me.

I once wrote this one poem that was like, “Special recognises special / hurt recognises hurt.”A lot of my life, I’ve felt invisible. And also, when I’m struggling with something or I’m hurting, my first thought is, I want to disappear; I want to go away. It’s a feeling that even if you’re there, physically present, someone could put their hand through you. It’s different than being a ghost. I have this

other poem: “It means so much to have your words remembered / It means so much to have your pain acknowledged,” and I guess that’s what it’s about — someone acknowledging your hurt. And, from my perspective, wanting to say it to other people that are hurting: I acknowledge you.

Zach Sokol

Originally published on: https://i-d.vice.com/en_au/article/9kkjb3/bunny-rogers-wants-you-to-know-she-acknowledges-your-hurt, August, 2017

REVIEW

TimeOut New YorkBunny Rogers: Brig Und Ladder

Born in 1990, Bunny Rogers grew up on the internet, and her art vividly conveys a childhood lived partly in the real world and partly online. Her installation is the third in a trilogy set at Columbine High School, scene of the 1999 school shooting. While the first two parts revolved around Colum-bine’s library and cafeteria, respectively, the third centers on the school’s auditorium.

In a darkened theater furnished with a large toy orca representing the SeaWorld animal that killed three people, an animated video features characters appropriated from MTV’s series Clone High. Stand-ins for the artist, her family and her friends, they sing a Russian rendition of “Memory” from Cats, a lugubrious performance that, like the cuddly orca, represents an attempt to heal public and private trauma. Another series of sculptures—including three savaged office chairs and a chain-link fence decorated with autumn leaves—suggests the aftermath of violence and rituals of mourning.

Rogers’s work is surprisingly potent, tapping into a peculiarly American strain of weirdness, teen-age angst and the uncertain comforts of family and community. Sometimes these things combine to produce tragedies like Columbine. At other times they conspire to create artists of promise like Rogers.

Anne Doran

Originally published on https://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/bunny-rogers-brig-und-ladder, Au-gust, 2017

REVIEW

Flash ArtBunny Rogers Whitney Museum of American Art / New York

After “Columbine Library” (2014, at Société in Berlin) and “Columbine Cafeteria” (2016, at Green-spon in New York), “Brig Und Ladder” is Bunny Rogers’s third show partially dedicated to me-morializing the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School, thus making it the final part of a sort of architectural trilogy.

As with the previous exhibitions, here Rogers faultlessly displays a signature lexicon: alternative cartoon characters from the early 2000s, mass murder, stuffed animals, cartoonish domestic ob-jects and the impenetrable sadness of teenagers.

The centerpiece of the show is the video A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Audi-torium (all works 2017), presented in a carpeted screening room with six spring-assisted folding auditorium chairs (Columbine Auditorium seating). Sitting in the auditorium chairs, we watch three animated characters (crude 3-D adaptations of characters from Clone High) ascend to the auditori-um stage and perform a Russian rendition of a song from the musical Cats. While any true occasion for the “holiday performance” is indiscernible, it is understood to be related to the thirteen killed in the massacre — as a memorial, the limp and creepy preciousness of the recital casts an ambigu-ous mood of mourning that feels both earnest and put-on.

On the floor in front of the video lies a limp stuffed animal with a homemade quilting patch stitched to its abdomen (Tilikum body pillow). Rogers’s stated interest in the Columbine shooting involves online communities of teenage girls who express a fantastical and empathetic attraction for Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, the tortured pseudo-goths who shot up their high school; Tilikum, the now-dead orca whale who killed two SeaWorld employees and a hapless trespasser, became an object of empathy largely due to the 2013 documentary Black Fish, which detailed the brutal treatment of whales in captivity. A homely body pillow of an actual killer whale speaks to the overwhelming and haphazard capacity of empathy: in this case, horror at human cruelty displaced and converted into warm feelings for a whale who, while deserving of respect and freedom, is unlikely to be a (huggable) friend of human people.

Beyond the screening room are a series of spotlit works (three wrecked office chairs, two sets of giant ladders and mops, a Thomas the Tank Engine toy, air fresheners hanging on a fence) that, per the press release, are to be understood as related to the artist’s own life and lost relationships. Their impenetrability makes them hermetic as objects of memorial or autobiography. The cheesy maroon curtains, then, differentiate between an onstage area that, with the Columbine memorial scene and Tilikum pillow, seems to speak to the inadequacy of empathy to deal with structural trag-edy or individualized pain, and a backstage so oblique that it refuses anything like an identificatory response — with diaristic intimacy providing only the possibility for further alienation.

Jack Gross

Originally published on https://www.flashartonline.com/2017/08/bunny-rogers-whitney-museum-of-american-art-new-york/, August, 2017

REVIEW

BLOUIN ARTINFO ‘Brig Und Ladder’ by Bunny Rogers at Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York is presenting “Brig Und Ladder” by Bunny Rogers.

At 27, this young artist is presenting her first museum exhibition in the U.S. Bunny Rogers in true sense is the gen next internet child who grew up with the computer. Even her first brush with art-making came through her experiments on Neopets.com, a website that allowed her to create and care for her own virtual pets. Rogers became known online for her provocative and honest portray-als of self. Whether she is writing a poem or creating a website or sculpting, her output reflects a pre-teen angst, friendship, and memory. In her current work, Bunny Rogers draws from a personal cosmology to explore universal experiences of loss, alienation, and a search for belonging.

Her layered installations, videos, and sculptures begin with wide-ranging yet highly specific ref-erences, from young-adult fiction and early 2000s cartoons, like Clone High, to autobiographical events and violent media spectacles, such as the 1999 Columbine High School shooting. Rogers’s techniques are equally idiosyncratic. She borrows from theater costuming, design, and industrial furniture manufacturing, and often crafts her work by hand. This hybrid approach gives Rogers’s objects and spaces a distinct texture; they read simultaneously as slick and intimate, highly con-structed but also sincere. She is the author of “Cunny Poem: Vol 1” (2014) and “My Apologies Accepted” (2014) and currently lives and works in New York.

Originally published on http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2367512/brig-und-ladder-by-bun-ny-rogers-at-whitney-museum-of-american, July, 2017

REVIEW

VICEBunny in the Headlights

On view this July at the Whitney Museum of American Art is Bunny Rogers’ “Brig und Ladder,” a sometimes-confounding fusion of personal reflection and pop-cultural theatrics.

On April 20, 1999, on the outskirts of Denver, two students at Columbine High School killed a dozen of their fellows and one teacher, and injured multiple others, inscribing themselves in American culture in the process. The Columbine High School massacre, as it has come to be known, has sparked a wearying number of copycat mass shootings, as well as music, books, movies, TV shows, and endless tortured reflection. Bunny Rogers was nine years old at the time, and the rever-berations of that day have stuck with her. The young artist has titled three of her recent exhibitions after the school’s library and cafeteria—scenes of much of the carnage—and many of her works make reference to the event and its aftermath.

The centerpiece of “Bunny Rogers: Brig Und Ladder” at the Whitney, the artist’s first major muse-um outing, is the animated video A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium. The video itself depicts the auditorium’s stage in relatively convincing 3D, and is projected in a darkened room fitted with six theater seats. These replicate those in the school, giving audience members the impression of being in a simulation of the original site. The stage in the video is ee-rily empty and completely bare save for a couple of plastic chairs off to one side, a boxlike plinth draped in black fabric, and an upright piano at which sits a female figure. Volumetric, yet not limned with the naturalism of her surroundings, the young woman makes for an odd avatar, half in the “real” world of the illusionistic digital rendering, half in the flatland of a cartoon.

The pianist plays a short piece, then two more girls enter and mount the steps to the stage. Both seem even more stylized than the one at the piano, moving stiffly, like paper dolls brought to life. They have smooth, U-shaped faces with flattened, truncated heads from which sheets of hair hang down, and their perpetually downcast eyes are represented by simple curved lines. The pianist begins again and the central figure, clad entirely in teen-goth black, starts to sing the familiar tune “Memory,” from the Broadway musical Cats, but in Russian. The third figure plays a flute solo near the end of the song, the two young women exit, and a flock of small birds (or perhaps huge insects) flutters against the burgundy curtain at the back of the stage. Fade out.

The CGI performance produces a strange and complex affect. The plaintive, girlish rendition of the elegiac show tune, the weird mien and awkward quasi-life of the characters, and the magical-realist entrance and disappearance of the flying creatures combine with our knowledge of the setting to elicit a certain melancholy. This is commingled with a chilled splash of horror, even as we remain fully aware that these emotions play out as the result of kitsch piled on top of kitsch. A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium is creepy and alienating, yet also quietly bracing in the way it forces us to watch ourselves being seduced by such transparent means.

But Rogers’s project is also baffling. Specific meaning remains elusive, and the artist’s choice of details cryptic. Why these figures, compellingly particular but unrelatable in their abstract artifice? Why that tacky song, and why in Russian? And what about the only other object in the gallery, a large plush-toy orca, Tilikum Body Pillow, named after the animal performer at SeaWorld who killed three people?

Stepping through a wine-colored curtain into a second room, we find more sculptural ciphers. Spot-lit against mid-gray walls, these often occur, like the performers and chairs in the video, in groups of three. A trio of high wooden ladders, too platonically perfect to ever see use, leans against one wall. Each structure stands over twelve feet tall and sports a finish of metallic marker in a different hue: copper, blue, or purple. Those flanking the central one are missing one or two rungs, throwing their utility into further doubt. Three oversized cartoonish string mops have double-layered heads in paired hues—yellow and blue, red and green, blue and orange—like school colors. A knee-high