LokLF; ,oa tula - National Institute of Health & Family Welfare

Building Memories at Tula: Sacred Landscapes and Architectural Veneration

Transcript of Building Memories at Tula: Sacred Landscapes and Architectural Veneration

81

4

Building Memories at Tula

Sacred Landscapes and Architectural Veneration

DOI: 10.5876/9781607323778.c004

Cynthia Kristan-Graham

IN TRODUCTION: GROUND RULES

Sited on a steep promontory above the confluence of two rivers, and featuring temple-pyramids, ballcourts, residential zones, colonnaded halls, and a large popu-lation of brightly painted figural sculpture, Tula was one of the most impressive civic-ceremonial centers in Early Postclassic Central Mexico (figures 0.2 and 4.1). Tula Grande, the nucleus of the site, was visible from every quarter of the city. In addition to being the center of political, ritual, and economic life, it was built and embellished as sacred terrain.

One set of buildings, Building 3 and the Canal and El Corral Localities, share similar plans and architectural elements that erode the distinction between domes-tic and public space and recall mythic-historic locales that were integral to Tula’s identity and governance. Here it is the language of architecture rather than imagery in the normative sense that references ancestral and ontological concerns through what I term architectural veneration and interior landscapes. Both are unusual and innovative in Mesoamerica. Beginning in the Preclassic period with the Gulf Coast Olmec, buildings, site plans, and landscapes were designed to create microenviron-ments that often recalled cosmic or mythic realms. The civic-ceremonial center of La Venta, Tabasco, for example, featured earthen mounds, tombs, and monumental carved stone heads and altars in an architecturally cultivated landscape that recalled sacred mountains and ancestry, and provided stages for the enactment of rituals (Grove 1999: 265–275). Likewise, the later Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan integrated

82 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

architecture with constructed landscapes to create ritual environments that evoked the aquatic and terrestrial topography and geography of creation myths (Broda 1987; Matos 1987; Broda et al. 1987; Townsend 1982). Elsewhere in Mesoamerica, especially among the Maya, ancestry was most often visually, symbolically, and lin-guistically asserted and celebrated in stone monuments via individuals or families.

At Tula, though, many times concerns with ancestry, family, and rulership seem to have looked inward to building interiors that featured vivid references to other times and places, where memories were both embedded and conjured. I suggest that Building 3 and major habitation units can be understood as both homages to, and pastiches of, past and present buildings and landscapes; these spaces were sacred venues for rituals and activities where family, ancestry, and polity were equated and commemorated.

Before turning to a discussion of Tula, I first consider the issues of architecture, landscape, and memory that inform this study. The essay length regrettably does not allow an in-depth analysis of these points. (For a magisterial discussion of these issues on both a theoretical level and as they relate to the Classic and Late Classic Maya, see Hendon 2010.)

The power of architecture and space to shape experience has long been under-stood, since “in the absence of books and formal instruction, architecture is a key to comprehend reality . . . In some societies, the building is the primary text for handing down a tradition, for presenting a view of the world” (Tuan 1977: 112). In Mesoamerica and elsewhere, this was most evident with the house, as most people lived in the same type of domicile from birth to death. The home is the cradle of distant and deep memories that continue to percolate throughout life. The Heideggerian notion that individuals dwell “in the world” has been instrumental in

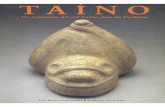

Figure 4.1. View of the Tula Grande civic-ceremonial center, facing north: (from left) Building 3, Pyramid B, and Pyramid C (photo by Cynthia Kristan-Graham).

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 83

analyzing how consciousness, identity, and relationships come into being via dwell-ing in and with a specific place (Tilley 1994; Basso 1996: 106–108; Bender 1998: 36; see Thomas 2008 for a revisionist phenomenology of building and dwelling). A near contemporary of Heidegger, Gaston Bachelard (1969), explored the ontology of architecture. He compared the topology of the house with the topology of the inner self, and considered the subtle and nuanced ways that the house, especially the childhood home, informed one’s relationship to the world and sparked memo-ries of family and protection.

Approaching the house and family from a structuralist perspective, Claude Lévi-Strauss (1982, 1987) developed the idea of the “house society” as a way to accommodate Northwest Coast and California Indian groups that did not easily fit into the existing kinship taxonomy. He observed that for some groups with flexible rules of descent, the house as both a domicile and an organizing principle served to identify family members and their tangible and intangible possessions. As a social category, the house society has had greater value as an explanatory tool than as an amendment to kinship classification, and has been used to help understand the dynamics of societies in Southeast Asia, the Maya region, and Amazonia (Carsten and Hugh-Jones 1995; Joyce and Gillespie 2000; Kristan-Graham 2001).

It probably is not happenstance that Heidegger, Bachelard, and Lévi-Strauss use houses as their examples to explore ontological relationships, Heidegger his Black Forest farmhouse, Bachelard the childhood house, and Lévi-Strauss the lifelong house. Far from being static stage sets or symbols that simply express meaning, buildings participate “in the construction of meaning through the ordering of space and social relationships” (Psarra 2009: 2).

Buildings also have intimate relationships with the landscape; they might repli-cate landscape features, have elements that symbolically or formally merge with the environs, and are part of the larger landscape. Today landscape has come to mean particularized ways of viewing the world, and encompasses seeing, remembering, and being. Originally, landscape, both linguistically and philosophically, meant a way of seeing and representing the world in Italian and Northern Renaissance painting in which the natural and cultural worlds were constructed to present ide-als and human interactions with the land (Cosgrove 1998: 9). In these and other cultures and art traditions, natural or altered terrains and the built environment are rarely perceived as neutral external domains, but rather as palimpsests or as per-petually shifting views, filtered through the sensibilities of individuals and groups with particular constituencies, histories, and interests (Thomas 1993; Schama 1995; Basso 1996; Cosgrove 1998: 1–13) (For an analysis of more complex concepts, espe-cially political landscapes, see A. Smith 2003.).

84 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

Landscape is neither passive nor something simple to see (Bender 1998: 25). People live in, view, appropriate, and transform the landscape, and in doing so understandings of the world and notions of identity are forged (Bender 1993: 3). Such treatment of the landscape is not limited to living or building in or on the land, or representing it, but involves fluid conceptions regarding ongoing relationships between people and their environment. An experiential understanding of buildings and landscape begins from the premise that both exist in and order three-dimen-sional space, and participate in social formation. People have a kinesthetic relation-ship with both architecture and landscape that is fundamental in the construction and the communication of knowledge. Because people simultaneously live in and view landscapes, the relationship can be casual but also causal.

Some of the most compelling ideas about the meaningful connection between people and the landscape are found in the work of Barbara Bender and Christopher Tilley. Their respective phenomenological approaches to Neolithic structures in Europe consider material, scale, and aesthetics to help fill in the frustrating lacunae of ritual, social, and political data, especially regarding the interaction between people and their environments. Bender (1993, 1998) vividly illustrates the long and nuanced life of Stonehenge from prehistoric through modern times. While important work continues to illuminate how Stonehenge functioned as a mortuary and ritual center for nearby villages (Parker Pearson et al. 2011; Parker Pearson 2012), Bender (1998: 39–67) suggests that the construction processes and materials were symbolic as well as practical. Drawing on archaeological data and ethnographic analogy, she suggests that at Stonehenge it was “the process of ritually working the landscape, the acts of making and depositing, rather than the creation of an enduring end result, that was significant” (Bender 1998: 57, empha-sis original). Bender reinserts ancient people as active agents making aesthetic, ritual, and procedural choices in rearranging monoliths, incising stones, and caching ritual deposits. In being aware of siting, sight, and the ancient designers of Stonehenge, she provides a useful model of how the union of buildings, monu-ments, and landscape is an ongoing process of the making, erasure, and remaking of memory, and fundamentally alters what might be seen as a mundane construc-tion process with symbolic, meaningful associations.

Likewise, Tilley’s (1994, 2008) work on Neolithic earthworks in Great Britain and Sweden focuses on the merging of self and place. His attention to the allur-ing qualities of stone and the kinesthetic experience of landscape erodes the rather comfortable “iconographic” or Albertian views in which the world is either a symbolic puzzle to be decoded or a space to be entered into or understood from one privileged, normative viewpoint. As Tilley (1994: 26) explains, people tend to derive deep meaning from land they inhabit and use in ways that give

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 85

meaning, assurance, and significance to their lives. The place acts dialectically so as to create the people who are of that place. These qualities of locales give rise to a feeling of belonging and rootedness and a familiarity, which is not born just out of knowl-edge, but of concern that provides ontological security.

Landscape and architecture are closely related to another concern, memory. As we have seen, landscape is not a fixed vision or thought; in part this is because “human memory constructs rather than retrieves, and . . . the past thus originates from the elaboration of cultural memory, which is itself socially constructed” (Knapp and Ashmore 1999: 13). In other words, landscape is the world that is seen but not neces-sarily what is physically there to see (Thomas 1993: 27; Cosgrove 1998: 13).

This is also the case with the memory palace, a mnemonic device that classical orators and medieval and Renaissance scholars used to store and retrieve memories. Rather than being a real building, a memory palace is a mental construct wherein memories are stored in rooms that the rememberer creates. The entire edifice has flexibility for enlarging and remodeling as required for embedding specific memo-ries, with relative location, architectural details, furniture, and other specifications adding to the specificity of a particular memory’s location and thereby facilitating memory recall by mentally traveling to a room distinguished by location and fur-nishings ( J. Spence 1983). This system was—and can be—undeniably efficient, yet we now know that memory is an active, nuanced process that involves more than

“capturing” memories and concretizing them in the form of architecture, landmarks, or imagery (Küchler 1993: 103). Memories are flexible and sensitive; a memory is not “something people have but something they do” (Hendon 2010: 27, emphasis original). Within a culture, an individual may belong to a variety of shifting social groups that each foster recollections that form one larger, unique prismatic mem-ory. This process of social practices fashioning memories is termed memory work, and it is a multifaceted, elastic process that can include reformulations, conveying, and even forgetting (Mills and Walker 2008: 4).

One of the most fertile loci of memory work is the house. The same time that Heidegger, Bachelard, and Levi-Strauss were exploring the import of houses proved to be a watershed for scholarship about the family, social formation, and memory. Perhaps most influential was Maurice Halbwachs’s 1925 Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. One focal point was the family, which mediates not only daily life but also beliefs and interactions with the larger world; in particular, perceptions of the world are often colored by comparisons to one’s own family (Halbwachs 1992: 54, 74, 81). While not specifically addressing the house, Halbwachs (1992: 82–83, 175) does mention places, domains, and internal “landmarks” as catalysts for storing and retrieving memories, and the house is implicitly where family activity occurs.

86 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

As a student of Emile Durkheim, he furthered the Durkheimian notion of collec-tive memory for discerning the shared metamemory of cultures. Because collective memory privileges the overall culture at the expense of the individual and mini-mizes the effect of social contexts in memory making, today the concept of social memory is preferable (Connerton 1989; Mills and Walker 2008: 6). So, while the family is one group that fosters memories, it is not the only physical, emotional, or social context that shapes thoughts about the past.

Events that occur in familiar locations may seem more intimate and casual, and on a repetitive basis they can become more vivid, and hence are more likely to be remembered (Basso 1996: 108; Bradley 2002: 12; da Costa Meyer 2009: 178–179; Lyndon 2009: 65; Hendon 2010: 25). As a kin group, the family shares intimate moments, long stretches of time, routine activities, and special events, all in familiar spaces and structures. Membership within any social group, especially a kin group, enables memory acquisition, emplacement, and retrieval. Aside from personal memories, family members adopt attitudes that are common to the group and that follow a logic that is specific to the family that lives and/or performs rituals together (Halbwachs 1992). It is this casual and constant interaction that can be causal.

Pierre Bourdieu’s (1977) related concept of habitus unites space, practice, and remembering into a theory about the creation and perpetuation of social pat-terns: individuals and groups come to understand and pass on their understand-ing of the world through and within regular social practices in which they partici-pate yet not might be fully aware of, nor be able to explicate. Bourdieu attempts to modulate a strictly deterministic viewpoint to suggest that social space is a nuanced field in which history, objects, and the body share dispositions that seem to be natural and are transmitted generationally both internally and through everyday experiences such as observation, emulation, and bodily movements. Dispositions include social codes, behavior, and organizing principles in which the body becomes an agent of memory. Habitus operates in an indefinable ter-ritory between free will and determinism; practices and patterns that have been internalized can shift and be passed on from one context and one generation to another. In other words, although habitus is a structuring principle, it is flexible and not immune to further structuring.

Habitus is an important concept because it acknowledges the affective capacity of architecture and situates power in places, individuals, and groups:

It is because the subjects do not, strictly speaking, know what they are doing that what they do has more meaning than they know. The habitus is the universalizing mediation that causes an individual agents’ practice, with explicit reason or signifying intent, to be none the less “sensible” and “reasonable” (Bourdieu 1977: 79).

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 87

Bourdieu’s concept of habitus is somewhat vague and slippery in part because the formation of personhood and social group is complex and elusive. Still, habitus has been criticized for operating with agents who are too little involved or not fully aware of their roles or capacity (Bender 1998: 36).

One corrective is to consider social spaces and social relations as geopolitical landscapes. Critical to this is the notion of spatial perception or evocative space, the interaction between actors and the spaces they inhabit. According to Adam T. Smith (2003: 73), this is “a space of signs, signals, cues and codes—the analytical dimension of space where we are no longer simply drones moving through space but sensible creatures aware of spatial forms and aesthetics.” In this sense, the very building blocks of ancient cities are transformative sociopolitical domains in which relationships are diagrammed, perceived, and enacted. One of Smith’s examples is the Classic Maya, whose ceremonial centers were embellished with ritualized political-historical sculpture and painting. Such imagery diagrammed social relations, and as part of three-dimensional space, it merged with architec-ture, spatial patterns, and ritual actors and their movement to form a nexus that could enhance and complement filial, local, regional, and supraregional concerns. Geopolitical landscapes thus can foster an understanding of how power and social relations operate within a network of political practices and relations of authority (A. Smith 2003: 112–148). We shall return to all of these issues as specific build-ings are analyzed.

BUILDING 3

Building 3 is one of the largest edifices on the Tula Grande plaza, measuring 90 m by 60 m (Mastache and Cobean 2000: 116) (figures 4.1 and 4.2). It dates to the Tollan phase (850/900–1150 CE), which is roughly coeval with the Early Postclassic period, when Tula was a regional capital in what is now the state of Hidalgo, in the northern Basin of Mexico following the decline of Teotihuacan.1 The building is also known as the Palacio Quemado, or Burnt Palace, because the original adobe walls were transformed into fired brick when part of the Tula Grande plaza was burnt and abandoned at the end of the Tollan phase for reasons that remain enigmatic.

The building occupies the northwest corner of the plaza (figures 4.1, 4.3). A cor-ridor separates it from Pyramid B, and the vestibules of both buildings present a veiled façade of pillars to the rest of the plaza. Situated in Tula’s main public space, Building 3 surely was a focal point and backdrop for public spectacles, screening the public from more private rituals and proceedings that occurred within. The building consists of three large halls, several framing vestibules, and a row of small

88 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

rooms (figure 4.2). Halls 1–3 are north of the South Vestibule, which adjoins the Tula Grande plaza. Six small rooms are directly north of the halls; some provide access to the North Vestibule, which faces the North Plazoleta (see Acosta 1956, 1957, 1960 for discussions of the building’s construction, and Sterpone 2009 for a detailed discussion of the building’s stratigraphy). While the Tula Grande plaza, framed by Pyramids B and C, Buildings 3 and K, and Ballcourt 2, is usually thought of as Tula’s “main plaza,” Osvaldo Sterpone (2007: 26) proposes that the north or

“back” of Building 3 and Pyramid B, along with Ballcourt 1 and the North Plazoleta, formed another focal point (figure 4.3).

The building seems to have been designed for multiple uses, considering its flex-ible plan and customized features. Benches and altars attached to walls could have been used for sitting, feasting, and display. Associated carved and painted imagery illustrate rituals that probably occurred in these spaces, including processions and rites that used copal incense and autosacrificial instruments (Acosta 1957: 168–169; Diehl 1983: 65, plate IX, figure 19). Three-dimensional sculpture found in the halls, including chacmools and standard bearers, could have served as ritual furniture. The halls contain hearths; caches are in altars and beneath floors (Acosta 1956: 104; Taube n.d.; Cobean and Mastache 2003; Cobean and Gamboa Cabezas 2007); and one small room contained shelves lined with ceramic jars and pipes (Acosta 1945: 59) that perhaps were ritual supplies or tribute (George Bey and William Ringle, personal communication 2001).

Figure 4.2. Plan of Building 3 (after Healan 1989: figure 3.4).

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 89

All of these features indicate a plausible range of functions. Interpretations of Building 3 include a palace, a council house (Diehl 1983: 65; see Bey and May 2014 regarding formal similarities with Maya council houses); an administrative or govern-mental center (Matos 1981: 29; Guevara Chumacero 2004; Sterpone 2007: 48); and spaces where rites such as accession (Koontz, chapter 3, this volume), funerals (Kristan-Graham 1999), autosacrifice (Klein 1987), human sacrifice (Mastache et al. 2002: 117), and/or prayer or penitence (López Luján 2006: 410) may have taken place.2 I suggest,

Figure 4.3. Plan of Tula Grande (after Mastache et al. 2002: figure 5.8).

90 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

in addition, that the three main halls provided a symbolic domestic space for ritual-political theater, forming a visual-spatial equation between polity and family.

Building 3 may well represent a new type of structure, a fusion of the gallery-patio, colonnaded hall, and three-temple building. Karl Ruppert (1950) first described the gallery-patio structure at Chichén Itzá. This unique T-shaped building includes a gal-lery, or rectangular room with one or more rows of columns, fused to a square patio that often includes a central portico. The best-known gallery-patio at Chichén is the Mercado (Ruppert 1950: figures 1, 2, 8); Structures 3B3 and 3B8 are also gallery-patios, and each patio contains a central sunken area (Ruppert 1952: figures 19, 22) (figure

4.4a). Chichén also features several buildings that generally recall Building 3’s large halls and vestibules. Structures 2C1 and 2C8 have three adjacent rooms with rectan-gular foyers, sans supports (Ruppert 1952: figures 7, 13). This basic plan is enlarged in the more grandiose Casa Colorada (Ruppert 1952: figure 30). Finally, each hall in Building 3 can be considered a colonnaded hall. Precedents abound at Chichén, with the Temple of the Warriors as the most prominent; in North Mexico, both Alta Vista and La Quemada in Zacatecas have a building called the Hall of Columns, an apt name for a colonnaded hall (Tozzer 1957: 80; Hers 1989; 1995: 108–110) (fig-ures 4.4b and 4.4c). Precursors of colonnaded halls and sunken patios, in small scale, are also found in the Bajío (Kristan-Graham 2011; Beekman and Christensen 2011). Building 3 fuses salient aspects of each of the building types mentioned here: the impluvia of some colonnaded halls and gallery-patios, the vestibule of the gallery-patio, and the rectangular plan and triple room of the three-temple structure.

The genealogy of Building 3 intersects with the larger picture of Epiclassic Mesoamerica.3 Two of the principal excavators of Tula, Guadalupe Mastache and Robert Cobean (in Mastache, Cobean, and Healan 2002: 62–67, figure 8) also excavated the site of La Mesa, 14 km east of Tula. There they found what they thought was an embryonic form of Building 3: elevated on a 1-m platform stood a vestibule with one row of pillars in front of a rectangular hall with a central door-way (no central sunken area was apparent). The lack of domestic debris led to the conclusion that the building had ritual or cultic significance. La Mesa may be one of a number of new settlements founded by migrants from the Bajío (Mastache and Cobean 1989). Marshaling evidence from ceramics, climatology, biology, and linguistics, Christopher Beekman and Alexander Christensen (2011) suggest that these new Epiclassic arrivals to the Tula region were Nahua-speakers who left their homes during a desiccated Classic period for the Mezquital Valley, in which Tula resides, which “had a pull factor attracting migrants.”

Regardless of the ultimate origin of the gallery-patio and colonnaded hall, the larger issue is this: after the Classic period, Mesoamerican centers that sought to fill part of the void left by the decline of Teotihuacan seemed to have searched for

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 91

appropriate architectural forms as well as symbols for potent forms of expression and settlement. One advantage of colonnaded structures, as A. M. Tozzer (1957: 80) first noticed at Chichén, is the capacity to accommodate large numbers of people for communal worship and public rituals near pyramids.4 What Building 3 lacked in the dramatic, vertical focus of Pyramids B and C was compensated for by its square footage that accommodated ritual actors.

Building 3 as a Sacred Landscape: TollanOne locale embodied in this building is Tollan, as I (Kristan-Graham 2011) suggested earlier. Tollan was a concept central to a sense of heritage among many Mesoamerican

Figure 4.4. (a) Plan of Chichén Itzá Structure 3B8 (after Ruppert 1952: figure 22); (b) plan of Hall of Columns, Alta Vista (after from Pickering 1974: figure 1); (c) plan of Hall of Columns and southern part of La Quemada (after Nelson 2003: figure 6.2).

92 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

cultures. It was considered to be a fertile foundation place, most often a lake sur-rounded by reeds to which many Mesoamerican peoples traced their origins. Its inhabitants were Toltecs, a people skilled in the arts of fine craftsmanship and cred-ited with inventing the calendar, agriculture, divination, and autosacrifice. Tollan is mentioned frequently in Mexican contact-period sources, since the Aztecs, Late Postclassic Maya, and other Mesoamerican peoples traced descent from the Toltecs.5

One definition of the Nahua word Tollan is “place of rushes”; it later came to mean “metropolis,” since reeds grow together densely, paralleling large populations (Davies 1977: 26–27). As a linguistic prefix, the cognates tol or tul could signify a large population center; sixteenth-century sources list the well-known sites of Tula, Tulancingo, and Cholula as reed-places, with names including tol/tul in their names or having the honorific prefix, as in Tollan Chollan (Davies 1977: 26–27; Schele and Mathews 1998: 39). In antiquity such centers may have functioned as Tollans, or political centers and foundation places where political leaders were invested with power. Today, scholars understand Tollan as a foundation myth from which rul-ing peoples derived authority and links to ancestral, cultured people (Davies 1977; Schele and Mathews 1998), yet we cannot be sure what ancient Mesoamerican peoples thought of such places—were there actual or semilegendary places called Tollans, or was Tollan in ancient times more of a poetic and artistic metaphor?

A symbolic Tollan, or rather three such Tollans, is suggested by the plan and ele-vation of Building 3 (figures 4.2 and 4.5). Each of the three halls is roughly square in plan, and either pillars or columns supported roofs; however, the central spaces had shallow depressions that formed sunken patios or impluvia and may have been unroofed to admit light, rain, and views of the sky (Diehl 1989: 24).6 In his exca-vations at Tula, Jorge Acosta (1956: 104, 1960: 33) found round stone strainers to keep drains in the patios from clogging. When filled with water the impluvia would have appeared as artificial lakes, with the surrounding pillars or columns serving as abstract reeds symbolic of Tollan. On a more general level, the watery pools in Hall 3 are akin to the courtyards that collected rainwater runoff near Maya temple-pyra-mids and paralleled the landscape of valleys with natural rises and depressions (Fash 2009: 236). Barbara Stark (1999) has discussed the integration of pond systems with public space and site planning from the Preclassic-Epiclassic periods in the Gulf Coast. In many cases, runoff or natural water sources such as streams were diverted into cisterns or waterways in public spaces for ritual purposes. The artificial lakes in Building 3 are not very different from this concept, albeit in a smaller scale.

A secondary definition of Tollan as a place “where the trees stand erect” (López Austin and López Luján 2000: 35–36) is evoked if these supports are understood as tree trunks rather than reeds. In Mesoamerica seemingly everyone, especially rul-ers, claimed ancestry from Tollan, and the architectural support-as-tree metaphor

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 93

has a specific association with rulership. In both Aztec and Maya thought, a ruler was equated with a flowering tree, and the Mixtec believed that ancestors and rul-ers were born from trees at Apoala, a foundation place; illustrations appear in the Vienna Codex and the Bodley Codex (Boone 2000a 94, 239, figures 51, 55).

Likewise, among the Classic Maya, trees and blossoms were equated with ancestry and royalty. One well-known example is Pakal’s stone sarcophagus from Palenque, which is carved with royal ancestors “emerging as trees sprouting from the earth” (Martin and Grube 2008: 165–166). David Stuart (in Houston and Cummins 2004: 366) suggests that the jade regalia of Maya lords precisely replicated parts of flowers. The beauty and fragrances of flowers had affinities with “aesthetic discern-ment, eloquence, and merriment—all emblematic of pleasurable elite life” (Stuart in Houston and Cummins 2004: 366). This poetic understanding of the pillars and columns is not only congruous with reading Building 3 as a symbolic Tollan, but it also supplements the understanding of the halls as loci of elite power.7

Further, the symbolism of the actual water collected in the patios is augmented by two caches buried under the patio in Hall 2. Acosta (1956: 104) found a 41-cm circular pit cut through the plaster floor; the contents of this, Offering 1, included a turquoise and pyrite mosaic mirror, fan coral, earspools, and other shell artifacts (Taube n.d.). Below this, sealed beneath the floor, Offering 2 contained five levels. From top to bottom the levels include: a pyrite mosaic mirror; a spondylus-shell

Figure 4.5. Aerial view of Building 3 (photo by Cynthia Kristan-Graham).

94 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

necklace; the famous shell tunic, made of over 1,200 rectangular pieces of spondylus shells, with a frame of oliva shells, that now resides in the Templo Mayor Museum in Mexico City; 18 spondylus shells; and a base of fan coral (Taube n.d.; Mastache et al. 2002: figure 5.39; Bernal 2012: figure 95; see Gettino Granados and Figueroa Silva 2003 for a discussion of solar symbolism and the caches). In Mesoamerican symbolism, mirrors can evoke a pool of water (Taube n.d.), and so the subterranean caches echo the sacred geography of Hall 2’s design.

Together both caches reinforced the concept of centrality. The offerings are in the center of the central hall of Building 3, marking both the building’s core and symbolizing the axis mundi, or world center. The mirrors likewise are a symbol of centrality. Such symbolism has been noted as early as the Middle Formative Olmec, and Teotihuacan recumbent figures with mirrors on their abdomens may refer to the world navel (Taube n.d.). Among the Maya, watery pools “seem to have been considered as mirror-like reflective portals to the underworld, where rituals, divina-tion, and sacrifice were performed” (Fash 2009: 232).

In addition, Karl Taube (n.d.) interprets Offering 1 as illustrative of a fiery hearth, since round mirrors can symbolize the sun, and in an oxidized state their red hues connote fire and burning. Spatially, hearths would be expected in the center of rooms and patios, but here they are symbolized by cached mirrors in an east-west line framing the patio and just south of the central axis of the room.

Building 3 as Architectural Vista: TeotihuacanGiven that Tollan was a widespread Mesoamerican myth, and that some actual place names referred to reed-places, Teotihuacan is a likely candidate for an early Tollan in the Mesoamerican landscape, considering its size, power, and magnificence (P. Carrasco 1982: 109; Boone 2000b: 380–381; Stuart 2000: 506; Fash, Tokovinine, and Fash 2009: 221). Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1998: 39) suggest that Teotihuacan and many lesser Tollans may have dotted the Mesoamerican landscape as “declarations of origin.” While many reed-places, such as Tula and Cholula, were known in the contact-period, there is epigraphic evidence for an actual reed-place. Stuart (2000: 502–504, figure 15.27a) identified the glyph puh in inscriptions from Tikal and Copan as “cattail reed.” The glyph “is noticeably placed in scenes evoking Teotihuacan styles and associations. Arguably, it specifies the location of such scenes as occurring in the place of the cattails, or Tollan” (Stuart 2000: 504). Teotihuacanos, too, may have perceived their home as Tollan, or a Tollan. Annabeth Headrick (1996: 80–81) has observed that in a mural at the Tepantitla apartment compound, four plants remarkably close to the puh glyph sprout from a doorway marked as a mountain, marking it as “Place of Cattails.”

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 95

Considering the status of Teotihuacan as a paragon of power and wealth, many sites emulated its distinctive architecture and symbol system, and Tula was no exception. However, its geographic and temporal proximity to Teotihuacan indi-cate that its architectural and aesthetic quotations were based, at least in part, on direct ties. For example, the site of Chingú, 9 km east of Tula and dating to the Teotihuacan Tzacualli-Metepec phases (1–700 CE), was a large Teotihuacan out-post devoted to lime procurement for construction projects in the Basin of Mexico. Links to Teotihuacan are evident in talud-tablero building profiles, the layout of public buildings that echoes the Ciudadela, and residential buildings that are simi-lar to Teotihuacan apartment compounds (Díaz 1980). Classic-period settlements within a few kilometers of Tula have traits that indicate direct ties with Teotihuacan, including apartment compounds, talud-tablero building profiles, and ceramic figurines. These sites were abandoned in the Epiclassic period, and then some of the occupants of the Teotihuacan-related sites, along with immigrants from North Mexico, populated Tula Chico, an Epiclassic settlement near Tula Grande (Mastache and Cobean 1989: 51, 56; Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009).

Tula Grande in general and Building 3 in particular reference or quote part of Teotihuacan. The civic-ceremonial core of Early Postclassic Tula is aligned 17 degrees east of astronomical north, like Teotihuacan. Moreover, two architec-tural anchors of the plaza are placed in a pattern reminiscent of the northern end of the Street of the Dead; the larger Pyramid C faces west, as does the Pyramid of the Sun, while the smaller Pyramid B faces south, as does the smaller Pyramid of the Moon (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 294). When Tula Chico was founded, it was virtually without such echoes of Teotihuacan. Since Teotihuacan’s decline and collapse paralleled Tula Chico’s rise, there probably was no strategic advantage to quote Teotihuacan’s art or architecture; however, Teotihuacan sym-bolism was reintroduced at Tula Grande as an integral part of political ambitions (Beekman and Christensen 2011).

Building 3 in particular references Teotihuacan by the talud-tablero profiles of altars and benches, processional compositions, and Offerings 1 and 2 in Hall 2 (figure 4.6a). At Teotihuacan, imposing temple platforms line the Street of the Dead, and some altars in apartment compounds feature the talud-tablero profile (Headrick 2007: figures 1.4, 3.1, figure 4: 6a, 6c). Tula’s use of the talud-tablero is intriguing, for a defining exterior architectural element adorned the interior of a building that lacked a planar façade and became ubiquitous in Tula halls (figure

4.6b–c). Although the talud-tablero predates Teotihuacan, geographic proxim-ity and its appearance in concert with a constellation of other distinctive traits makes it seems likely that Teotihuacan was the source of inspiration for the talud-tablero at Tula.8

Figure 4.6. (a) Drawing of a profile of the talud-tablero portion of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent from the Ciudadela, Teotihuacan (after Schele and Mathews 1998: 7.38); (b) Hall 2, Building 3, Tula, processional frieze (photograph by Mark Miller Graham); (c) drawing of a typical talus and wall at Teotihuacan. Murals were typically painted on the sloping talus surface and the flat upper walls.

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 97

Another Teotihuacan-Tula parallel involves processional compositions. Those from Building 3 are comparable in location and form to the ones painted on taluses on the lower walls in Teotihuacan apartment compounds, where figures seem to move along the interior walls (Kristan-Graham 1993) (figure 4.6b). In both cases, processional compositions seem to have been used in similar ways: movement is oriented around corners and even converges at open doorways. This suggests the images had a ritual use, perhaps as backdrops or actual parts of cer-emonies, with real actors plausibly acting out part of rituals in doorways, adding flexibility and theatricality to the rites and symbolic association of the spaces they inhabited.

The Hall 2 caches discussed earlier may also allude to Teotihuacan. The lower, earlier Offering 2 contains spondylus shells, a common offering at Teotihuacan. The layer of 18 such shells is especially compelling. Aside from the calendric importance of 18 throughout Mesoamerica, at the Temple of Quetzalcoatl the number 18 is repeated frequently. Eighteen sculpted images of the Teotihuacan War Serpent frame the main stairway and 18 individuals wearing warrior garb were found in three burials there (Taube n.d.). Taube (n.d.) compares Offering 2 to a Teotihuacan warrior bundle that contains not a mortal burial, but that of Tlaloc, a rain deity whom many scholars think originated, at least in part, at Teotihuacan.9 To Taube, the portion of the offering that consists of a mirror over a tunic is diagrammatic of Classic and Postclassic representations of Tlaloc, who often is represented with a solar disk on his abdomen. More important than this specific point of compari-son with Tlaloc is the idea that Offering 2 represents the ritual burial of a symbol of Teotihuacan par excellence. Moreover, since the cache’s topmost item, a mirror, could symbolize a fiery hearth, the bundle may have been symbolically burned. The location of a fire symbol below a fountain evokes the Aztec concept of atl-tlachinolli, or “water-fire,” which in Aztec art is usually represented as a stream of water interwoven with a flame. It was a metaphor for warfare, especially where defeat was lamented (Pasztory 1983: 83), and here might symbolize Teotihuacan’s demise. Unlike Aztec art, however, in Hall 2, “water-fire” and other vital concepts are expressed diagrammatically in three dimensions, demonstrating the penchant for spatial symbolism at Tula.

The focal point of the later Offering 1 is a pyrite and turquoise mirror. Turquoise was a new and important exchange item of the Postclassic period, and its presence may demonstrate Tula’s participation in new trade patterns (Taube n.d.). The super-imposition of Offerings 1 and 2, moreover, presents a stratigraphy of actual geopoli-tics in Central Mexico. Read sequentially beginning at the bottom, the offerings might commemorate the central place of Teotihuacan in Mesoamerica’s past, its symbolic death, and the subsequent rise of Tula (Taube n.d.). The placement within

98 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

an architectural setting that evokes Tollan adds a more ancient temporal layer. Ethnohistory and archaeology offer another version of this scenario. The Aztecs and other Central Mexican peoples believed that the Fifth Sun, or present age that they lived in at the time of contact, was created at Teotihuacan; they named the site, made offerings there (Heyden 2000; Matos 2000), and according to the Florentine Codex believed that government was created there (Boone 2000b: 375). The Aztecs likewise revered Tula and its inhabitants, made offerings there, and modeled some of their art and architecture after Tula prototypes (Umberger 1987).

Building 3 and Rites of RulershipHow does the imagery in Building 3 intersect with the edifice as a sacred landscape evocative of Tollan and Teotihuacan, and of ancestry in general? Stepping back to view the northern edge of the Tula Grande plaza provides some compelling evi-dence that much of the two- and three-dimensional imagery there represents rulers and heroes, and focuses on the life of the polity, principally its ritual-political con-cerns and staged events.

Some of the most prominent figural imagery, the monumental pillars that now are atop Pyramid B, are very probably portraits of rulers and heroes, as are the fig-ures carved on reliefs from Halls 1 and 2 of Building 3 ((Kristan-Graham 1989, 1999: figures 7.8–7.10) (figure 4.1). Many of the pillar figures have name glyphs, and in some instances these figures, sans glyphs but wearing the same costumes, appear in some of the Hall 3 reliefs. Acosta (1956: 91, 96, 112), who found the reliefs in the building rubble, thought that they originally adorned the upper walls of the halls, above benches with processional imagery. Aztec ethnographic data indicate that comparable horizontal imagery in similar rooms in the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan, were funereal images of rulers and heroes, with the benches serving as platforms for offerings. For clarification, horiziontal here includes prone, supine, and recumbent poses. Guadalupe Mastache (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 307) follows Eduard Seler in identifying the figures at Tula as “deceased warriors” comparable to the huehueteteo, or “honored deceased ancestral warriors,” illustrated on page 33 of the Codex Borgia. More recently, Elizabeth Boone’s (2007: 186, figure 108) close reading of this page suggests that Borgia 33 is an episode preceding the birth of the sun, with the supine figures on the roof of the Black Temple, who have the face paint of Quetzalcoatl or a fire deity and white hair and feathers indicative of sacrificial victims, as the “deified souls of dead warriors, who accompanied the sun from dawn to noon.” Susan Milbrath (2013: 82–83) analyzes this section of the codex as a narrative about astronomy, with page 33 illustrating a spring equinox festival and the recumbent figures on the temple as ahuiateteo, or deceased warriors

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 99

who rise with the equinox sun. Both of these readings contextualize and sharpen Mastache’s idea, and support my interpretation of the horizontal figures at Tula as funerary images of heroes and/or rulers.

There is also compelling evidence for attention to living rulers at Tula. A section of the east wall bench in Hall 2 that projected into the room has been interpreted as a throne (Miller 1985: 12). Acosta (1963: 53) found a chacmool near this projec-tion, and Koontz (chapter 3, this volume) notes that this configuration is similar to the throne and chacmool pairings at Chichén. A doorway connects this hall with Room 4, which has several important features: it is elevated, is accessed via a small stairway, is the only one in the building, and is on the building’s north-south axis (Mastache, Cobean, and Healan 2002: 117). This small but unique room has been called a sanctuary for the most sacred rites at Tula (Acosta 1960: 34, 37) or a space reserved for rulers (Mastache et al.. 2002: 117), and it is tempting to see the stair-way as the ritual entry to a throne room. Both the throne and the special nature of Room 4 create a hierarchy in Building 3, with the central room and its direct access to the Tula Grande plaza being the focal space (figure 4.2). In fact the profile of the benches in Halls 1 and 2 very nearly matches the profile of Aztec teoicpalli, or straw thrones, illustrated in sixteenth-century codices such as the Codex Mendoza to such an extent that Miguel Guevara Chumacero (2004: 166–167, figure 5) calls benches at Tula “stone thrones.” If Hall 2 was conceived of as a Tollan, such a sacred geography would be a fitting locale for a royal space, including the funerals and audiences of rulers.

The two rooms are also linked via imagery. A portion of the bench frieze in Room 4 shows two frontal figures; one stands next to a profile bench, complete with a talud-tablero profile, as if he is marching into Hall 2 ( Jiménez 1998: figure 91). Then, figures in Hall 2 appear to move from the hall to the South Vestibule and then down to the Tula Grande plaza (de la Fuente, Trejo, and Gutierrez 1988: figures 81–83, 85). Today the bench friezes in Hall 2 are in poor condition, but line drawings made shortly after their discovery in the 1950s illustrate two rows of figures entering from Room 4, marching around the room, and converging at the doorway in the south wall that leads to the main plaza. One row of figures, led by a goggle-eyed figure, seems to carry weapons and be protected with cot-ton armor, and so they have been identified as warriors (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 309), caciques, priests, and dignitaries (Diehl 1983: 64) (figures 4.7a and 4.7b). Others, in contrast, carry banners, staffs, rattles, and a conch trumpet, and have sound scrolls (figure 4.7c). This frieze has been read as a ceremony similar to the Aztec ritual Etzqualitzli, led by the high priest of Tlaloc (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 309) or a commemoration of Teotihuacan in general, with the sound scrolls and musical instruments paralleling pages 35–37 of the Codex Borgia,

100 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

which depicts the heroic sacrifice of the gods at Teotihuacan, followed by the birth of music (Taube n.d.).

These readings, like the echoes of landscape and architecture in Hall 1, stress continuity with a predecessor and successor of Tula. Water, buried caches, ances-try, architectural vistas, and symbolic landscapes are all essential ingredients of the great halls in Building 3. Together they form a complex setting that adds depth and texture to the history that was created and recalled. The power and allure afforded by landscape were central to these endeavors.

Looking at LandscapeIf the Tula populace shared in the general Mesoamerican mythic-architectural con-ception in which temple-pyramids symbolized primordial mountains, and plazas, courts, and halls primordial seas with portals to the supernatural underworld, then the Tula Grande plaza was imbued with de facto sacred dimensions (Brady and Ashmore 1999: 135; Schele and Mathews 1998: 43–48).

Building 3 has a low elevation compared to the adjacent Pyramid B and the nearby Pyramid C, yet, set on a steep terrace and with a vestibule of plastered col-umns and pillars, it could have been an alluring curtain between the public gaze and private rituals and business it housed. The central patio plan is not infrequent in

Figure 4.7. Tula: (a) Plan of Hall 2, Building 3 (after Healan 1989: figure 3.4); (b) Hall 2, Building 3 frieze (after Mastache and Cobean 2000: figure 25); and (c) Hall 2, Building 3 frieze (after Jiménez 1998: figure 92).

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 101

Mesoamerica, but at Tula the specific arrangement is symbolically charged. While some sites linguistically and/or functionally were Tollans, or neo-Tollans, a promi-nent building at Tula actually was built to resemble Tollan and very probably evokes its most magnificent earthly manifestation: Teotihuacan.

This may have been part of a strategy—following the decline of Teotihuacan, as many centers vied to be its political and economic successors—to bear a dual aura of antiquity and legitimacy. Likewise, allusions to the Bajío and North Mexico were natural, considering Tula’s heterogeneous demographics and social interactions. While it was de rigueur in many Mesoamerican art traditions to proclaim ancestry, prestige, and affiliation via costume (Stone 1989), Tula parsed its political and social aspirations through architecture as well.10

Building 3, then, can be seen as part of the landscape and as a storehouse of constructed landscapes. In geography and architecture, and as an expansive trope, landscape can operate on nuanced levels. While the large halls in Building 3 are technically interior spaces, they recall external and mythic worlds furnished with reeds, trees, and lakes. Such interior landscapes erode, conceptually and spatially, the normative interior/exterior boundary by including open roofs, porous façades, and imagery that represents and invites movement through rooms and even out-side. The Building 3 interior landscapes might have assisted—in poetic and meta-phoric ways—in recalling or transporting individuals and groups to other times and places, especially in vividly recalling a pan-Mesoamerican foundation place. Because the Tollan and Teotihuacan allusions are inhabitable, and because land-scape is a physical realm and also an internal place concerned with being and identity, the effect is experienced rather than just seen, and roads to personhood and polity existed in Building 3. Considering the esteem and sacred nature that Mesoamerican peoples held for Tollan and its heirs, and the fact that people expe-rience space and landscape through the body (Ashmore 2008; Rainbird 2008), the immediate and hyperdramatic effects of occupying such spaces can only be imagined.

BUILDING 3 A S A MODEL HOUS E

Building 3 has another symbolic referent that is closer to home: domestic architec-ture. The plan and architectural elements of Halls 1–3 are also reminiscent of the central courtyards of house groups and apartment compounds in Tula and its envi-rons, notably the Canal and El Corral Localities (cf. Guevara Chumacero 2004: 165–166).

The Canal Locality house group is located 1.5 km northeast of Tula Grande and dates to the Late Tollan phase (Healan 1989, Mastache, Cobean, and Healan 2002:

102 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

159). Its three main sectors—the West, Central, and East Groups—feature houses arranged around central courtyards with altars. The Central Group courtyard is the focus of the entire house group, since all houses face it (figure 4.8). Houses that abut the courtyard have three steps that lead to the sunken courtyard, where the central altar has a talud profile, reminiscent of those from Teotihuacan apartment compounds. Ten stone carvings of human skulls were probably once attached to the altar, and may refer to death or ancestors, given the Mesoamerican pattern of ances-tor burial in domestic space (Healan 1989: 126, figures 9.18–9.20). Beneath the west stairs of the courtyard was a cache of human bones that came from four or five indi-viduals. The bones show evidence of mutilation or sacrifice, and may postdate the construction of the courtyard (Healan 1989: 126–127). The West Group Courtyard and its altar are similar in form, but the altar contained a human burial. This may be an interred ancestor, and as with other Mesoamerican cultures, indicate that the occupants of the houses had some type of kin association and practiced ancestor worship (Healan 1989).

The El Corral Locality is the largest apartment compound at Tula; it dates to the Early Tollan phase and is close to Tula Chico. Apartment compounds are single-story complexes that consist of individual apartment units, or a few rooms surrounding a patio. In plan it is a smaller and simpler version of a Teotihuacan

Figure 4.8. Canal Locality central court (courtesy of Dan Healan).

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 103

apartment compound (Healan in Mastache, Cobean, and Healan 2002: 155; fig-ure 6.6). At Tula, one family would have lived in one apartment, which clustered together and surrounded a central public courtyard. The El Corral Locality is simi-lar to Building 3 and other structures at Tula Grande that feature colonnaded halls, patios (but lacking sunken floors), possibly open roofs, and altars with talud-tablero profiles built into walls. At least one altar contained a human burial with offer-ings. Caches beneath three of the four columns in Structure 1 contain remains of starfish (Mandeville and Healan 1989: 181–194), with a marine association similar to the deposits found in Building 3. Because the El Corral Locality has larger interi-ors and superior-quality construction compared to the house groups, Dan Healan (in Mastache, Cobean, and Healan 2002: 156) thinks that it may have been a resi-dence for higher-status families; general similarities with Building 3 may indicate combined political and ceremonial and/or domestic activities (Mandeville and Healan 1989: 197). Hendon (2010: 170) notes that among the Maya, a bench was an index of a house. The same may be true for the buildings under discussion at Tula; benches with a talud-tablero profile frame domestic courtyards and patios and the Halls 1 and 2 in Building 3, where part of their function may have been as so-called stone thrones.

It is likely that extended families lived in the house complexes and apartment compounds. In the Canal Locality it is probable that a nuclear family lived in each house, and extended families or lineages occupied house groups (Healan 1989: 142, 153). The courtyards would have been foci of family life, serving as extensions of houses and providing additional space for craft specialization and domestic and ritual activities (Mastache, Cobean, and Healan 2002: 153). The same would probably hold true for apartment compounds. Hence, besides being the spatial and symbolic centers for kin groups, the courtyards were the domestic and ritual anchors for habitation units, where the life of the lineage was perpetuated in a private setting.

Houses at TeotihuacanIn addition to being analogous to Tula residential courtyards, the basic design of Halls 1–3 has especially close parallels with Teotihuacan. Michael Smith (2008: 145) has observed that “Tula’s epicenter, typified by symmetry and regularity, exhib-its perhaps the most strongly formal plan of any Mesoamerican city.” Tula Grande’s plan, including a large plaza, framing structures, ballcourts, and “unplanned resi-dential zones” turns away from Teotihuacan’s unique single-avenue plan and pro-claimed an allegiance to basic Mesoamerican principles (M. Smith 2008: 145). However, as discussed earlier, in other ways Tula seamlessly integrated features of

104 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

Teotihuacan planning and architectural into its new design idiom. This is especially true regarding domestic architecture.

Teotihuacan domestic architecture provides some remarkable parallels with Tula regarding form and symbolism. The approximately 2,000 apartment com-pounds at Teotihuacan housed most of its population, and had remarkable con-sistency in basic plan and usage throughout the city’s history (Manzanilla 2002: 55; Widmer and Storey 1993). While location, size, construction quality, and embellishment are indices of status, the compounds share the same basic plan: the center is a large patio with an adoratorio, or altar, in the middle. A temple frames one side of the patio, and porches are on the other sides (Pasztory 1997: 46–49). The stepped platform of each porch creates the patio’s sunken appear-ance. Porches or porticoes lead to family apartments, which have living quarters and small patios for family use. All patios were used for cooking, eating, working, and other communal activities. Rainwater was channeled to floor basins and out through drains (Headrick 2007: 6). The apartment courtyard seems to have been one of the most common yet important filial and ritual spaces at Teotihuacan; it was the spatial and ritual focus of the apartment compound, and the area where craftsmen belonging to a corporate kin group carried out their work (Millon 1968; M. Spence 1974).

Specific ancestral memories and referents at Teotihuacan are associated with the principal patios. High-status burials, found there near temples, are notable for their associated artifacts and cremated state, and are differentiated from the lower-status burials found in private spaces below patio floors (Cowgill 2003). Since the number of these burials is far lower than all of the occupants, they probably attest to an ancestor cult (Manzanilla 2002: 57–60; Widmer and Storey 1993: 101). Skeletal evidence of kinship ties among dwellers of each compound reinforces the notion of ancestor burial (M. Spence 1974). Ancestor burials, whether in founda-tion walls (Linné 1934: 54–59) or altars (Rattray 1992), symbolically extend the constituency of apartment compounds to both the living and the dead. A high-status burial often accompanied the early construction phase of an apartment compound (Sempowski 1992). The equation of high-status burials and inaugura-tion of apartment compounds may indicate that corpses of revered ancestors were requisite elements for residents to claim descent from that ancestor (Headrick 2007: 44–71).

The halls in Building 3 contain the essential, minimal elements of a Teotihuacan ritual patio: porticoes or columns frame a central sunken patio, which in turn con-tains a central adoratorio as the ritual focus (Sanders and Evans 2006: 257). The principal patios at Teotihuacan served communal ritual purposes for compound residents (Headrick 2007: 49), which is similar to the function of domestic

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 105

patios at the El Corral and Canal Localities at Tula. At Tula, sometimes a hearth replaces the central altar (Evans 2006: 297), but Taube’s reading of Offerings 1 and 2 in Hall 2 has shown how a symbolic hearth can be understood to occupy the center of that room.

In addition to practical or ritual concerns, the apartment compounds were reservoirs of memory. Esther Pasztory (1997: 52–54) presents a compelling archi-tectural genealogy that has powerful ancestral associations. The apartment com-pounds replicate in miniature the basic plan of the Ciudadela, an immense enclo-sure at the southern end of the Street of the Dead; it included a 7-m-high wall, a single entrance, housing, pyramids on raised platforms that created the large plaza’s sunken appearance, and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. While the Ciudadela probably was a palace with ritual and administrative functions that was built in 100–200 CE, and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent was modified in ca. 400 CE, apartment compounds in general had a longer lifespan as they were built and used throughout the city’s life (Pasztory 1997: 108–109, 116). These links between the Ciudadela and apartment compounds might symbolize Teotihuacan’s corporate and collective ideology as grafted from the state to the lineage (Pasztory 1997: 50), or perhaps the social relations among the lineage or other apartment inhabitants were patterned along principles similar to the state at large.11

Ancestor Veneration in MesoamericaOther traditions of ancestor veneration provide a conceptual framework for under-standing the house and its symbolism at Tula. At La Quemada, skeletal displays seem to have been one of the most prolific visual-symbolic programs. The Hall of Columns contained broken and disarticulated bones from several hundred indi-viduals buried below the floor (Nelson, Darling, and Kice 1992: 306; Nelson 2004). It is unclear if these remains are associated with cataclysmic events since mortuary remains were carefully displayed elsewhere. An example is found at Terrace 18, a nearby residential unit. The basic terrace plan and building components—includ-ing ballcourt, temple, sunken spaces, and benches—replicate in miniature the gen-eral layout of the La Quemada site core. The temple contained selected remains of 14 individuals that were displayed on, or suspended above, the floor. Similar bones were displaced in discrete groups. Ben Nelson and others (Nelson, Darling, and Kice 1992: 311) who excavated La Quemada think that this temple may have served as a charnel building in which the remains of revered ancestors and/or community elders were displayed or entombed. This is one evocative example of a La Quemada mortuary display used for enshrinement. When the site was abandoned ca. 900 CE it remained the focus of ritual maintenance by departing lineages, and presumably

106 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

their heirs, who periodically returned to the site center and former residences for ritual visits. Nelson (2003: 87–89) views the mortuary displays as a continuing link with the ancestors, the past, the supernatural realm, and also the land that was home to the visitors who maintained such presentations.

At the other end of Mesoamerica, both the highland and lowland Maya prac-ticed ancestor veneration from at least 1000 BCE through the contact period, according to Patricia McAnany (1995). By participating in such an ingrained tradition via funerary pyramids, burials beneath house floors, household shrines, and ritual practices, the Maya managed to maintain the existing social order, and especially to help the elites sustain their noble or even divine status. Ancestor veneration was central to the lineage, as land rights were passed generationally through the trappings of ritual and special-purpose architecture, and respect for the ancestors was borrowed and enhanced for emergent elites (McAnany 1995). Such practices were powerful structuring principles for kin groups living near or in the lineage compound of their ancestors, which through time became sacral-ized. By living in their houses and conducting rites on their behalf, the Maya were in the constant presence of their ancestors. Of particular interest here is the physical expression of lineage, where “the residence is the primary place where ancestral genealogy is encoded both ritualistically and corporally” (McAnany 1995: 111).

While compounds or clusters of residences may parallel the organization of a lineage, lineage may also structure or mirror social relations, particularly social or economic inequality. More specifically, Maya houses can be “under-stood as a locus for the enactment of claims to group continuity through the curation, transformation, and renewal of that group’s material and immaterial property” (Gillespie 2002: 73). By interring the bones of deceased relatives and heirlooms to facilitate reverence and communication, Susan Gillespie (2002: 68–73) argues, Maya house compounds played a role in perpetuating the souls and names of the dead.

The house was also a more intangible structuring element in society. Throughout Mesoamerica, there are instances where the house is a trope—physical, sym-bolic, and/or linguistic—for the family. A house might signify a body because in Mesoamerica parts of a house are often known by the names of body parts (Mock 1998: 4). Some communities or local divisions were conceived of as “great houses,” as John Monaghan (1996) as shown. A familiar case is the Aztec calpolli, which in the sixteenth century was translated as “house,” “large hall,” or “barrio” (Monaghan 1996: 181). The house or household may also be a metaphor for social relations. In the modern Mixtec town of Santiago Nuyoo in Oaxaca, Nuyootecos consciously order themselves on the model of the household (Monaghan 1996:

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 107

181, 192), and among the modern Zinacantanecos in Chiapas, Mexico, houses are diagrammatic of both society and the universe (Vogt 1998: 21).

Closest to Tula, Building 3 has close analogs with Aztec buildings in the Templo Mayor. In an analysis of autosacrifice that insists upon a precise under-standing of buildings and their functions, Cecelia Klein (1987: 304–314, figure 7) discusses the close analogs between Building 3 and the House of the Eagles at Tenochtitlan. The House of the Eagles sits on the north side of the Templo Mayor; its easternmost chamber includes a colonnade, patio, and benches that all recall elements from Building 3 (López Luján and López Austin 2009: figure 15). However, the smaller scale, more complex plan, and the meandering placement of the benches compared to the regularity of the halls in Building 3 indicate that the structures share architectural elements yet are not duplicates (López Luján and López Austin 2009: 410; also see Moedano Koer 1947, Molina Montes 1987, and Solís 1997 for arguments about the similarities of the structures). Imagery also connects the two sites. As at Tula, the bench reliefs feature armed figures processing; the subject in the House of the Eagles is clearly autosacrifice, as Klein argues, and implements of autosacrifice were on carved panels that once adorned the tops of walls in the halls of Building 3 (Acosta 1956, 1957). Following Klein, Leonardo López Luján’s (2006) archaeological work and analysis provides a much richer understanding of the House of the Eagles. The second building stage, ca. 1469, incorporated the allusions to Tula just discussed and chemical analysis has confirmed the practice of autosacrifice (López Luján 2006: 260–262). The smaller scale and dark interior were more suited to thoughtful reflection, pen-ance, funerary rites for a deceased king, and then the accession of his successor (López Luján 2006: 271–290; López Luján and López Austin 2009: 410).

The House of the Eagles thus can be understood as a structure that quoted parts of Tula’s Building 3 but was not a wholesale duplication. Interestingly, the entire Aztec building is called a house, as was a smaller section, the tlacochalco, or House of Darts; could those names, which originated from translations of their original Nahuatl, allude to the similarity of some building parts to domestic architecture?

Often the Tula-Tenochtitlan connection is discussed without specificity even though archaeological evidence exists. An Aztec occupation followed the Early Postclassic abandonment of Tula. Aztecs lived in the civic-ceremonial center and renovated some buildings, including the construction of platforms inside Building 3 (Diehl 1983: 168). Living in the capital of the society from which they claimed ancestry was an effective way for the Aztecs to absorb memories that are evident in countless examples of architecture and art in the Templo Mayor.

Lastly, houses have intimate associations with the body. Their plans and posses-sions help to shape movement and routines for daily and ritual life. As Bourdieu

108 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

suggests, houses house bodies that are agents of memory and help to structure and perpetuate society. And, just as bodies contain valuable, life-sustaining substances, houses protect precious contents such as the living and the dead, lineages, cached treasures, and cached memories (Hendon 2010: 178, 232).

A RCHITECT UR A L VENER ATION AT T ULA

Ancestral and funereal connotations may now be considered on other levels. The archaeology of death underscores the importance of visual monuments, landscapes, spatial patterning and symbolism, and the creation and perpetuation of memories (Bradley 1991; Cannon 2002). Temporal distance from the time of death results in personal memories ebbing and the advancement of social memories for a broader audience. Social memories can be more abstract and symbolic, since they are based less on personal relationships. Reservoirs and catalysts for such memories include symbolic or visual landscapes, ongoing rituals, or serial events (Cannon 2002: 192–195). While Building 3’s halls contain no extant human burials, the caches, funereal imagery, and ancestral associations based on parallels with domestic patios might be understood as a symbolic mortuary space, among its other uses. One hallmark of Tula public architecture is its architectural and narrative flexibility to house a range of ritual events. Funerary portraits, thrones, altars, and processional imag-ery amidst ritual and political activity was in a hallowed central place reminiscent of Tollan and foundations. Images, rites, and ideas about the recently departed mingled with those of more ancient forebears in a landscape that equated geo-graphical and cultural ancestors. Keith Jordan (2013) suggests that the recumbent Hall 3 figures might be part of a larger symbolic network that includes chacmools and horizontal figures with mirrors on their abdomens that the Hall 2 offerings invoke. A pose that is somewhat restricted in Mesoamerica yet is represented in at least three contexts in two rooms in one building—and which unites the ideas of death, warfare, sacrifice, and ancestry—resonates with the vital symbolism of the structure.

The physical and functional parallels between the great halls in Building 3 and the central courtyards of residential compounds cannot be underestimated. The courtyard is the nucleus of the house, and the house is the most basic, and as we have seen, the most resonant of personal and social spaces and images (Bachelard 1969). One plausible reading is that not only were lineages and the polity housed in similar quarters, but that the polity is the extended family, and vice versa, much like the polity and family were structured similarly in Maya (Webster 2001: 146) and Aztec (P. Carrasco 1982: 32–35) society. Healan’s (1989) observation that the El Corral courtyard might evince political uses unfortunately went without further

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 109

analysis. However, architectural equations are evident elsewhere in Mesoamerica. Hendon (1999: 117) has observed that some Classic Maya domestic patio forms are built into ritual and administrative centers in a possible attempt to represent the entire community. Yet she suggests that, rather than being a simple equation about the parity between family and state, the appearance of a domestic form in the ceremonial core implies the close structural relations between the two institutions.

The parallel between the structure of kinship and the political body is not unique to Mesoamerica. The most obvious point of comparison is ancient Roman soci-ety, which had many parallels between the family and state, including family and government organization and domestic and civil architecture. In her study of the Roman house (domus) and identity, Shelly Hales (2003: 55) observes that

at its most basic, Rome could be understood as growing from the house. In many respects, the city was an overgrown house and the house, a microcosmic city. So, for instance, they are both built around a hearth and contained within divinely pro-tected boundaries. Just as the domus represented the family’s past and present, so the cityscape of Rome preserved the presence and memoria of the entire citizen body.

Hales carefully constructs a case for the house and family as the genesis of Romani-tas, or Roman-ness. Likewise, the epicenter of what I call Tula-ness (Kristan-Gra-ham 2011) can, in part, be traced to the structure of filial organization and space. At the center is Tula Grande, with stone portraits of rulers and heroes and monu-mental house forms, surrounded by intermittent habitation units whose form and ancestral connotations echo the center.

Both domestic and public space shared fundamental traits and embedded mem-ories. Just as the Maya and the inhabitants of La Quemada carefully curated and venerated the bones of their ancestors and used them as a bridge between genera-tions, Building 3 seems to be the result of selecting and splicing architectural and offertory memories. The building designers seem to have enshrined architectural elements to form an archive of mythohistoric allusions that invite comparisons with Tollan, Teotihuacan, and other cultural points of origin. Roman Piña Chan (1975: 129) even proposed that Epiclassic sites with sunken patios were a form of remembrance for Teotihuacan; this is arguably the case with the slightly later Tula Grande. While Building 3 has no extant ancestral burials as corollaries to those in the Canal and El Corral Localities, Halls 1 and 2 were plausible loci of funerals for the expanded Tula family, with the simultaneous focal and sequestered nature con-noting a hallowed quality.

Recent work at Tula has allowed a deeper temporal understanding of some of these concepts. Tula Chico dates to the Epiclassic period, ca. 650–850, and is on

110 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

a rise north of Tula Grande. As its name denotes, it is smaller, occupying about 4 km2 compared to the 16-km2 area of Tula Grande during its Early Postclassic apo-gee (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 293, 312). Along with habitations, the ceremonial core of Tula Chico included a plaza, pyramids, a ballcourt, and large platforms. While these basic structures are similar to those from Tula Grande, ori-entation differs significantly, as discussed earlier (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 311–313).12

Most pertinent to this discussion is the discovery of imagery similar to that in Building 3. Fragments of carved horizontal figures were found; the figures wear ornate costumes and carry weapons similar to their counterparts in Building 3 images; one had a glyph near the head (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: figures 20, 21, 22). Several carved panels were found atop a pyramid that is dated 750–800 on the basis of ceramic evidence (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009). The architectural context atop the pyramid has similarities to Building 3 and structures at Tula Grande, as the reliefs “appear to have adorned benches and possibly the interiors of impluvia-like openings in the roofs” (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 313). Fragments of similar sculpted panels were also found in rubble associated with a partially dismantled building in the southwest corner of

Figure 4.9. (a) Carved bench panel, Hall 1,

Building 3, Tula (after de la Fuente et al. 1988: figure 107); (b) carved

panel, Tula Chico (after Mastache, Healan, and

Cobean 2009: figure 20).

B U I L D I N G M E M O R I E S AT T U L A 111

the plaza, which dates ca. 650–750 (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 313) (Figures 4.9a and 4: 9b).

The damaged state of this imagery is probably due to the abandonment and burning of Tula Chico sometime between 700 and 900. While the ceremonial core was left in a ruinous state, surrounding habitation areas continued to grow dur-ing the succeeding Early Postclassic period (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 314, 316). Several hypotheses try to explain this situation. Perhaps Tula Chico was regarded as sacred, hallowed ground as the earliest settlement in the area (Matos 1978; Mastache and Crespo 1982), or possibly it was the site of a conflict between competing factions (Mastache, Healan, and Cobean 2009: 322).

These discoveries have exciting ramifications: the roots of some Tula Grande imagery can now be firmly traced back to the Epiclassic period, with some typi-cal Tula imagery appearing several centuries earlier than previously thought. No doubt this also will be a crucial nugget in the ongoing debate of the Tula-Chichén Itzá chronology. Equally important, the long tradition of horizontal-figure imagery associated with prominent buildings at Tula evinces that this was an important and enduring category of imagery there. What might explain their continuing significance? If the Epiclassic figures had similar identities to their later counterparts—rulers and heroes—their placement at the bases and sum-mits of pyramids not only equates with some loci of Classic Maya stelae and bones of rulers but also with the artificial sacred terrain of mountaintops and valley floors. This is not exactly where the Hall 3 and Pyramid B images were located in Tula Grande, yet they were ensconced in buildings with allusions to sacred geography.

While the Tula art tradition does not include the glyphic texts of Maya art, the aforementioned parallels are uncanny, and suggest a reference to rulership that focuses less on linguistic literacy and more on the literacy of place. Nearly contemporary with Tula Chico was La Quemada, whose residential and public areas can be understood as charnel houses late in the site’s history, or at its aban-donment (Nelson, Darling, and Kice 1992). Could the Tula tradition of horizon-tal-figure imagery be a permanent form of deceased elite ancestors, sans actual bones? Their original locations, on bench/altar faces at Tula Chico and on the upper walls of the halls in Building 3 at Tula Grande, seems to approximate the location where actual bodies might have been placed or displayed.

Scattered throughout Tula Grande, familial and political domiciles traced the material and spiritual benefits of ancestor veneration. In addition to strength-ening ties between generations, lineages, households, and the polity, the venera-tion of ancestors directly, and in the form of architecture, could have promoted a sense of origin, identity, and destiny. The structures under discussion share some

112 C Y N T H I A K R I S TA N - G R A H A M

key design elements whose appearance in Tula Grande create a symbolic and formal unity. The repetition of the talud-tablero profile and sunken patios, for example, creates a sense of uniformity while recalling similar places. Such stan-dardized features could lead to a “shared form of understanding and performance” (Mills 2008: 95). While the import of ritual in public and special-purpose spaces or buildings is indisputable, the authority of rituals in domestic space is equally compelling when equated with the polity, ruler, and Tollan (see Hendon 1999: 117 for a parallel situation among Classic Maya ceremonial centers).