Bronze and Gold - Brill

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Bronze and Gold - Brill

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18778372-04803003

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

brill.com/orie

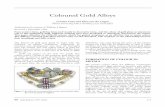

Bronze and GoldAl-Fārābī onMedicine

Miquel ForcadaProfessor, Section of Arabic and Islamic Studies, University of Barcelona,Barcelona, [email protected]

Abstract

Al-Fārābī wrote about the status of medicine in many of his works, and his defini-tion of medicine as a productive art influenced many later scholars. This definitiondemystified a philosophized conception of medicine that was current among the firstphysicians of Islam. However, al-Fārābī’s discourse is by no means unambiguous. Hesays that medicine may be a science, an art, and an art that may be composite, practi-cal, stochastic andnot self-sufficient. The article analyzes the textual basis of al-Fārābī’sdiscourse on medicine and its most salient references and influences, in connectionwith al-Fārābī’s understanding of Aristotle’s scientific method.

Keywords

al-Fārābī – medicine – philosophy – art – science

1 Introduction1

1.1 Al-Fārābī against the PhysiciansWhat medicine is, and in particular whether it is an art or a science, are com-plex issues that encompass many other questions about several meaningfulaspects of medical knowledge and its practice.2 Physicians and philosophers

1 This article has been commissioned as part of project FFI2017-88569-P, “Ciencia y sociedad enelMediterráneoOccidental: elCalendario deCórdoba y sus tradiciones,”Ministerio de Econo-mía, Industria y Competitividad.

2 Ian Maclean, Logic, Signs and Nature in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge U.P, 2002),

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

368 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

dealt with these issues in many different places and eras. Borrowing from thephysicians and iatrosophists (teachers of medicine) of late Antiquity and othersources, some scholars of early Islam made a contribution to the discussion,mostly conveying a philosophized image of medicine. Just as the late Alexan-drian legacy in medicine was a fundamental source of the new medicine writ-ten inArabic, the lateAlexandrian philosophers exerted a substantial influenceon the birth of philosophy in early Islam. The Islamicate scholars were thusaware of two images of medicine from Alexandria: that of the iatrosophistsand that of the philosophers, who objected that, when the iatrosophists saidthat “medicine is the sister of philosophy,” they were giving “bronze instead ofgold.” Al-Fārābī, (d. 950 or 951), one of the few philosophers of note in Islamwho did not earn his living as a physician, was profoundly influenced by theseAlexandrian philosophers.3 In accordance with their views, al-Fārābī definedmedicine as an art,4 as a reaction against the philosophized image of medicinecurrent in the Islamicate societies of the ninth and tenth centuries.5 The bestknown instantiation of this conception appears in absentia in Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm,al-Fārābī’s most popular treatise on the classification of the sciences, wheremedicine is not mentioned as a part of the tree of the sciences,6 not even as

70,mentions the following issues included in the discussion of whethermedicine is an art or ascience: dignity of the discipline, social usefulness, epistemology and characteristicmethods,relationship to other disciplines, relationship to the truth. The list may be longer.

3 Dimitri Gutas, “Fārābī iv. Fārābī and Greek Philosophy,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica. RetrievedAugust 20, 2019 via http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/farabi‑iv; see, moreover, PhilippeVallat, Farabi et l’École d’Alexandrie: Des prémisses de la connaissance à la philosophie poli-tique (Paris: Vrin, 2004).

4 For a synthesis of al-Fārābī’s conception of medicine, see Gotthard Strohmaier, “Receptionand Tradition: Medicine in the Byzantine and ArabWorld,” inWestern Medical Thought fromAntiquity to the Middle Ages, ed. by Mirko D. Grmek (Cambridge, MA-London: Harvard U.P.,1998), 165–7, and Joel Chandelier, “Medicine and Philosophy,” in Encyclopedia of MedievalPhilosophy: Philosophy between 500 and 1500, ed. by Henrik Lagerlund (Heidelberg: Springer,2011), 1, 737. It is worth noting that al-Fārābī was preceded by al-Kindī (d. 873), who definedmedicine as “a craft (mihna) intended to heal the human bodies of the excess and the defect[of their humoral imbalance] and to preserve their health”; see al-Kindī, Rasāʾil al-Kindī al-falsafiyya, al-qismal-awwal: kitābal-falsafaal-ūlā, risāla fī ḥudūdal-ashyāʾ, ed. byMuḥammadʿAbd al-Hādī Rīda (Cairo: Dār al-fikr al-ʿarabī, 1950), 171, ll.8–9; on al-Kindī on medicine, seePeter Adamson, Al-Kindī (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2007), 161–6.

5 Fritz W. Zimmermann, “Al-Fārābī und die philosophische Kritik an Galen von Alexander zuAverroes,” in Akten des VII. Kongresses für Arabistik und Islamwissenschaft, ed. by Albert Diet-rich (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1976), 407.

6 Al-Fārābī, Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm, ed. by ʿUthmān Amīn (Cairo: Dār al-fikr al-ʿarabī, 1949), 45, l.6 and104, l.6. Medicine is included, on the one hand, in a group of helpful matters together withagriculture, building and secretarial arts; and on the other, as a simile for explaining whatpolitics is. Onmedicine in the Iḥṣāʾ, seeMuḥsinMahdī, “Science, Philosophy, and Religion in

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 369

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

the spurious fruit of one of its true branches. This neglect is in stark contrastwith, for example, riyāsat al-bināʾ (architecture or construction engineering),which appears under the science of mechanics (ʿilm al-ḥiyal) and related disci-plines. In a modest but by no means negligible introduction to logic known asal-Tawṭiʾa, in which al-Fārābī also deals with the classification of the sciences,he sharply distinguishes medicine from theoretical (“syllogistic”) sciences inthat, like “agriculture, carpentry and building,” it applies deductive reasoningonly in a subsidiary manner.7All in all, what al-Fārābī said about medicine must be understood as one

aspect of his Aristotelization of philosophy and the sciences. Al-Fārābī crit-icized Galen and contrasted him with Aristotle in many ways and in manybooks8 in order to define the place of Galenism within Aristotle’s natural phi-losophy and to affirm the superiority of philosophy overmedicine. This processof Aristotelization was deeply rooted in the cultural ambiance of al-Fārābī’s

Alfarabi’s Enumeration of the Sciences,” in The Cultural Context of Medieval Learning, ed. byJohn Emery Murdoch and Edith Dudley Sylla (Dordrecht-Boston: D. Reidel Publishing Com-pany, 1975), 119 and 127–8; Sarah Stroumsa, “Al-Fārābī and Maimonides on Medicine as a Sci-ence,” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 3 (1993): 235–49; Gotthard Strohmaier, “Al-Fārābī überdie verschollene Aristotelesschrift ‘Über Gesundheit und Krankheit’ und über die StellungderMedizin im System derWissenschaften,” in Aristoteles alsWissenschaftstheoretiker, ed. byJohannes Irmscher and Reimar Müller (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1983), 202–5; and GerhardEndress, “The Cycle of Knowledge: Intellectual Traditions and Encyclopaedias of the Ratio-nal Sciences in Arabic Islamic Hellenism,” in Organizing Knowledge: Encyclopaedic Activitiesin the Pre-eighteenth Century IslamicWorld, ed. by idem (Leiden-Boston: Brill), 116–8.

7 Al-Fārābī, al-Tawṭiʾa aw risāla allatī ṣuddira bi-hā l-manṭiq, in Al-Manṭiq ʿinda l-Fārābī, vol. 1,ed. by Rafīq al-ʿAjam (Beirut: Dār al-mashriq, 1985), 56.

8 Zimmermann, “Al-Fārābī,”passim; Fritz W. Zimmermann, Al-Farabi’s Commentary and ShortTreatise on Aristotle’s De Interpretatione (London: Oxford University Press, 1981), introd.lxxxi–lxxxiii passim; Johann Christoph Bürgel, “Averroes ‘contra Galenum’: das Kapitel vonder Atmung im Colliget des Averroes als ein Zeugnis mittelalterlich-islamischer Kritik anGalen,” (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1967), 286–90 passim; Lutz Richter-Bern-burg, “Abu Bakr al-Rāzī and al-Fārābī on Medicine and Authority,” in In the Age of al-Fārābī:Arabic Philosophy in the Fourth/Tenth Century, ed. by Peter Adamson (London-Turin: War-burg Institute, 2008), esp. 120–6 and idem. “Medicina Ancilla Philosophiae: Ibn Ṭufayl’s Ḥayyibn Yaqẓān,” in The World of Ibn Ṭufayl, ed. by Lawrence I. Conrad (Leiden: Brill, 1996),esp. 94–6; and Gad Freudenthal and Resianne Fontaine, “Philosophy andMedicine in JewishProvence, anno 1199: Samuel Ibn Tibbon and Doeg the Edomite Translating Galen’s Tegni,”Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 26 (2016): 8–15. There are also two valuable recent studieson particular subjects: on logic, Kamran I. Karimullah, “Avicenna and Galen, Philosophy andMedicine: ContextualisingDiscussions of Medical Experience inMedieval Islamic Physiciansand Philosophers,”Oriens 45 (2017): 105–49; and on natural philosophy, Badr El-Fekkak, “Cos-mic, Corporeal and Civil Regencies: al-Fārābī’s anti-Galenic Defence of Hierarchical Cardio-centrism,” in Philosophy andMedicine in the Formative Period of Islam, ed. by Peter Adamsonand Peter E. Pormann (London:Warburg Institute, 2018), 255–68.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

370 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

time. Although an appraisal of the social and ideological aspects that underlieal-Fārābī’s thinking is beyond the scope of this article, we should bear in minda few contextual circumstances which are central to our analysis. Al-Fārābīshaped and developed his thought among the “Baghdad Aristotelians,” a groupof philosophers who aimed to restore the Aristotelian curriculumof the Schoolof Alexandria. These scholars probably wanted to reclaim and defend the roleof the philosopher as themain or only authority for scientific research and edu-cating elites.9 The jurisdiction over the soul, to which the physicians aspired,10seems to have been a crucial issue. An analysis of this issue and of the rivalrybetween physicians and philosophers is not among the aims of this article.However, Adab al-ṭabīb by al-Ruhāwī (fl. ninth century), the best record of howthe earliest physicians of Islamic societies sawmedicine and themselves, illus-trates sufficiently why al-Fārābī combated the philosophized conceptions ofmedicine. One passage is particularly eloquent in this regard; the author relatesan anecdote attributed to thephysician and logician Jibrīl b. Bakhtīshūʿ (d. 828):

It is said of Jibrīl, the physician of al-Maʾmūn, that he said one day to thislatter: “I have been healing the minds of kings and judges for fifty years.How can I be compared to anyone else?” [The caliph] considered he wasright.

Inwhat follows, al-Ruhāwī goes on to justify his view that the physician is supe-rior to the philosopher because the latter heals the soul whereas the formerheals both the body and the soul. The argument finishes with this lapidarystatement that needs no further comment:

The doctor therefore most deserves that one says of him: “He is who imi-tates the actions of the Creator, exalted be He, according to his capacity.”This is one of the definitions of philosophy.

In this context, al-Fārābī putmedicine, thephysicians andGalen in their properplace.11

9 Zimmermann, “Al-Fārābī,” 407–8 and Strohmaier, “Reception,” 167, mentioning the prob-lem of the jurisdiction over the soul.

10 Al-Ruhāwī, Adab al-ṭabīb, ed. by Murayzin Saʿīd Murayzin ʿAsīrī (Riyad: Markaz al-malikFayṣal li-l-buḥūth wa-l-dirāsāt al-islāmiyya, 1992), 213. The author is influenced by theAlexandrian commentaries onDeSectis, as OliverOverwien has shown in “Eine spätantik-alexandrinische Vorlesung über Galens De sectis in al-Ruhāwīs Bildung des Arztes (Adabal-ṭabīb),” Galenos 10 (2016): 195–206.

11 I borrow this expression from Richter-Bernburg, “Abū Bakr al-Rāzī and al-Fārābī,” 119.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 371

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

1.2 The Place of MedicineThe place of medicine lies outside the two main lines of al-Fārābī’s thought:12first, that only philosophical life brings human beings to ultimate felicity andperfection; second, the fuller realization of human beings occurs only withinthe confines of the ideal city ruled by the philosopher-king. From the first per-spective, al-Fārābī said that whereas medicine is an art like carpentry whosegoal is a work (health), natural philosophy is a deductive science whose goalis theoretical knowledge, which provides the natural philosopher with a sharein human perfection and gives him the utmost felicity.13 As for the collectiveperspective, al-Fārābī said in Fuṣūlmuntazaʿa,14 following Aristotle and Plato,15that in the city ruled by the “statesman,” the physician cares for the bodies ofthe citizens while the statesman cares for their souls. Since the soul is noblerthan the body, the statesman ismore eminent than the physician, and since it isthe statesman who ensures the proper functioning of the city, he must controlthe activities of the physician. In al-Tanbīh ʿalā sabīl al-saʿāda, a work on ethics,al-Fārābī combines the two perspectives.16Medicine is like trade, navigation oragriculture: an art comprising theory and practice whose final purpose is util-ity, in which knowledge (ʿilm) enables the practitioner to do something usefulfor the common good. In contrast, philosophy is a theoretical art whose objectis beauty, which in turn is the origin of felicity, and therefore philosophy is themeans by which one obtains true felicity.17However, the situation is not as simple as this. In an introduction to the

Metaphysics, al-Fārābī considers that medicine is actually a science.18 Here,

12 MiriamS. Galston, Politics andExcellence (Princeton: PrincetonU.P., 1990), 56–94, esp. 56–9.

13 Al-Fārābī, Risāla fī l-radd ʿalā Jālīnūs fīmānāqaḍa fīhi Arisṭūṭālīs li-aʿḍāʾ al-insān, in Rasāʾilfalsafiyya li-l-Kindī wa-l-Fārābī wa-Ibn Bājja wa-Ibn ʿAdī, ed. by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Badawī(Beirut-Casablanca: Dār al-Andalus, 1980), 39, l.18–40, l.20; on this work, see below §5.1.

14 Al-Fārābī, Fuṣūl muntazaʿa, ed. by Fawzī M. Najjār (Beirut: Dār al-mashriq, 1971), 24–5,§§3–4.

15 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1094a27–1094b7, and 1102a18–21. It is worth noting thatthis passage and the other excerpts considered in this section also reflect Plato’s concep-tion of medicine as a craft and the subordination of the physician to the philosopher. Heexpressed these views in the Republic and otherworks; for a recent analysis of these issues,see Susan B. Levin, Plato’s Rivalry with Medicine: A Struggle and Its Dissolution (New York:Oxford U.P., 2014), esp. 135–41.

16 According to Galston, Politics and Excellence, 13, he is a “statesman who is not a philoso-pher but it is nonetheless a ruler of excellence.”

17 Al-Fārābī, al-Tanbīh ʿalā sabīl al-saʿāda, ed. by Jaʿfar Āl Yāsīn (Beirut: Dār al-manāhil, 1987),73–7.

18 See below in this article, section 2.2.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

372 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

we may assume, he is following Aristotle, who defines medicine as epistēmēmany times in the Metaphysics,19 but al-Fārābī is likely to have known thatAristotle also says that medicine is a tekhnē in several works, including theMetaphysics.20 Hence al-Fārābī’s task consists not just of reviewing criticallywhat Galen and his followers said about the epistemic status of medicine, butalso of harmonizing the opinions of Aristotle and his commentators.21 In addi-tion, al-Fārābī had to shed light on other topics that precede the understandingof what medicine is, such as what science is or is not, and what the differenceis between a practical and a composite art. These processes culminate in thedefinition of medicine as a productive art extant in the Risāla fī l-radd ʿalā Jāl-īnūsmentioned above, a work that deals with the contrast between Galen andAristotle regarding the purpose of anatomy and physiology. This definitionwasoriginal and exerted a notable influence over major authors like Ibn Sīnā andIbn Rushd, whose works prompted a fruitful debate on the status of medicinein the Islamic lands and in Christian Europe. The general purpose of this arti-cle is therefore to analyze how, and on what grounds, al-Fārābī concluded thatmedicine was a productive art and what this assumption entailed. Since thechronology of al-Fārābī’s works is by nomeans clear, here we will structure thestudy in an order that al-Fārābī himself could have appreciated. First, we willanalyze his works on theOrganon, which contain the fundamentals of method

19 Aristotle,Metaphysics, 997b28–31, 1021b5–6, 1061a2–5,1064a1.20 Aristotle,Metaphysics, 1070a29.21 As is well known, whether medicine was epistēmē or tekhnēwas a complex issue that had

concerned many scholars since Plato and Hippocrates. For our purposes we should focuson the fact that neither Aristotle nor Galen held a clearly defined opinion on this issue. OnGalen, see Stefania Fortuna, “La definizione della medicina in Galeno,” La Parola del Pas-sato 42 (1987): 181–96; Mario Vegetti: “L’imagine del medico e lo statuto epistemologicodella medicina,” in Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II 37.2, ed. by WolfgangHasse (Berlin-New-York: Walter de Gruyter, 1994), 1672–717; Véronique Boudon-Millot,“Art, science et conjecture chez Galien,” inGalien et la philosophie, ed. by Jonathan Barnesand Jacques Jouanna (Geneva: Vandoeuvres, 2003), 269–98 and “La place de la médecineà l’ intérieur de la classification des arts dans le De constitutione artis medicae,” in Galien:systématisation de la médecine, ed. by Jacques Boulogne and Daniel Delattre (Villeneuved’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2003), 63–86; R. Jim Hankinson, “Art andExperience: Greek Philosophy and the Status of Medicine,” Quaestio 4 (2004): 3–24; andTeun Tieleman, “Galen on Medicine as a Science and as an Art,” History of Medicine 2(2015): 132–40. On Aristotle, see Philip van der Eijk and Sarah Francis, “Aristotelismus undantike Medizin,” in Antike Medizin im Schnittpunkt von Geistes-und Naturwissenschaften,ed. by Christian Brockmann and Wolfram Brunschön (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2009),220–1, particularly the bibliography given in n. 32; Riccardo Chiaradonna, “Universals inAncient Medicine,” in Universals in Ancient Philosophy, ed. by Riccardo Chiaradonna andGabrielle Galluzzo (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2013), 381–423.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 373

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

and epistemology that structure his conception of medicine, and then Risālafī l-radd ʿalā Jālīnūs on natural philosophy, where we find his most importantpassages on the topic. The books on practical philosophy and related matterswill be considered in order to provide additional insights into the other works.

2 Before al-Fārābī: An Overview of the Bipartite Conceptionsof Medicine

2.1 The Influence of Pseudo-Galen’sDe sectis ad introducendosThe study of the impact of Alexandrian views of medicine and philosophy onearly Islam is beyond the scope of this article but there are several features thatshould be considered in order to understand al-Fārābī’s position on medicine.First, the Summaria Alexandrinorum,22 and most particularly the abridgmentof pseudo-Galen’s De sectis, exerted a strong influence over the early Islami-cate physicians.23 The impact of the De sectismay bemeasured by the numberof Arabic versions that have come down to us. Apart from the abridgementmentioned above translated by Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq (d. 873) and his circle, twoother works have come down to us in Arabic: Ḥunayn’s translation of the fulltext24 and an abridgment of the Alexandrian summary attributed to a certainYaḥyā al-Naḥwī.25 In addition, sufficiently sound evidence has been found byOverwien in Ibn Hindū’s Miftāḥ al-ṭibb to believe that there were other com-

22 On this collection in Arabic sources, Elinor Lieber, “Galen in Hebrew: the transmissionof Galen’s works in the mediaeval Islamic world,” in Galen: Problems and Prospects, ed.by Vivian Nutton (London: The Wellcome Institute for Medicine, 1981), 171–9 and OliverOverwien,Medizinische Lehrwerke aus dem spätantiken Alexandria: Die Tabulae Vindobo-nenses und Summaria Alexandrinorum zu Galens De sectis (Berlin-Boston: Walter deGruyter, 2019), 50–67.

23 On De sectis, see Peter E. Pormann, “The Alexandrian Summary ( Jawāmiʿ) of Galen’s Onthe sects for Beginners: Commentary or Abridgment?,” Bulletin of the Institute of Classi-cal Studies 47 (2004): 11–33; Ivan Garofalo, “La Traduzione araba del De Sectis e il som-mario degli alessandrini,”Galeno 1 (2007): 191–210; andOverwien,Medizinische Lehrwerke,esp. 26–34 and 160ff. (annotated translation into German).

24 Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq, Kitāb Jālīnūs fī firaq al-ṭibb li-l-mutaʿallimīn, ed. by Muḥammad SalīmSālim (Cairo: Maktabat Dār al-Kutub, 1977).

25 Peter E. Pormann, “Jean le Grammairien et le De Sectis dans la littératuremédicale d’Alex-andrie,” in Galenismo e medicina tardoantica: Fonti Greche, Latine e Arabe, ed. by IvanGarofalo and Amneris Roselli (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 2003), 253–258. AsPormann says, this Yaḥyā al-Naḥwī should not be taken to be John Philoponus; he is theobscure author of the Summaria abridgments, who may possibly be the John of Alexan-dria whowrote a commentary on De sectis preserved in Latin that will be analyzed below;see, moreover, Pormann, “The Alexandrian Summary,” 22.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

374 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

mentaries on De sectis,26 now lost, that the Islamicate scholars could read.27These commentaries were heavily influenced by the introductions to philoso-phy written by the late Alexandrian philosophers,28 and so wemay reasonablyassume that they contributed decisively to creating the philosophized image ofmedicine that spread in early Islam.Second, according to the tradition of late Alexandrian iatrosophists, mostly

conveyed by the abridgment of De sectis, the Islamic authors presented medi-cine as a discipline divided into ʿilm (or naẓar) and ʿamal, theory and practice,and further subdivided under five headings: theory into physiology, aetiologyand semiology, and practice into hygiene and therapy.29 Ḥunayn b. Isḥāqwrotean introduction to medicine known asMadkhal fī l-ṭibb orMasāʾil fī l-ṭibb (Isa-goge Johannitii in the European medieval tradition),30 complemented by hisnephew Ḥubaysh, in which medicine was expounded according to the patternof De sectis and thus began with the pairing of theory and practice.31 This bookcontributed to the diffusion of this division of medicine.

26 Oliver Overwien, “Eine spätantik-alexandrinische Vorlesung über Galens De sectis in IbnHindūs Schlüssel zur Medizin (Miftāḥ al-ṭibb),” Oriens 43 (2015): 318 ff.

27 On the extant versions of these texts and their authors, seeOverwien,Medizinische Lehrw-erke, 24–8. Two commentaries have come down to us complete, possibly from sixth-century Ravenna. One is attributed to Agnellus of Ravenna. This work is usually knownas Lectures on Galen’s De Sectis, after the title given in the edition and translation byLeendert G. Westerink and Classics Seminar 609 (Buffalo: Department of Classics-StateUniversity of New York at Buffalo, 1982). Agnellus’ commentary is attributed to Gessiusin one manuscript. The second commentary, very similar to the first, is attributed to acertain John of Alexandria, Commentaria in librum De sectis Galeni, ed. by ChristopherD. Pritchet (Leiden: Brill, 1982). There are fragments of two other commentaries writtenby Archelaus and Palladius edited in Giovanni Baffioni, “Inediti di Archelao da un codicebolognese,” and “Scolii inediti di Palladio al De sectis di Galeno,” Bollettino del Comitatoper la preparazione dell’Edizione nazionale dei Classici Greci e Latini 3 (1954): 57–76, and 6(1958): 61–78, respectively. There is also a prologue to a lost commentary of an unknownauthor, edited by Daniella Manetti, “Commentarium in Galeni De sectis,” in Corpus deipapiri filosofici greci et latini (CPF): testi e lessico nei papiri di cultura greca e latina. Parte III,Commentari (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1995), 19–38.

28 Mossman Roueché, “Did Medical Students Study Philosophy in Alexandria?,” Bulletin ofthe Institute of Classical Studies 43 (1999): 166–9; see below in this article.

29 John Walbridge (ed.), Jawāmiʿ al-Iskandarāniyyīn li-kitāb Jālīnūs fī firaq al-ṭibb (Provo,Utah: Brigham Young U.P., 2014), 7–9; see Overwien,Medizinische Lehrwerke, 38–42.

30 Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq and Ḥubaysh,Masāʾil fī l-ṭibb, ed. byMuḥammad ʿA. Zayyān et al. (Cairo-Beirut: Dār al-kitāb al-miṣrī-Dār al-kitāb al-lubnānī, 1978), 2; on the parts of medicine, see19, 39, 63, 75 and 224–5.

31 Danielle Jacquart and Nicoletta Palmieri, “La tradition alexandrine desMasāʾil fi ṭ-ṭibb deḤunain ibn Isḥāq,” in Storia e ecdotica dei testimedici greci, ed. by Antonio Garzya (Naples:M. D’Auria Editore, 1991), 223–31, and Palmieri, “La théorie de lamédecine des Alexandrinsaux Arabes,” in Les voies de la science grecque, ed. by Danielle Jacquart (Geneva: Librairie

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 375

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

Third, there was a quite widespread definition of medicine based on itsessential ends, maintaining health and healing disease, which are at the sametime the two subdivisions of practice. Al-Rāzī (d. 930) formulated this defini-tion inal-Manṣūrī fī l-ṭibb as follows:32 “medicine is preservinghealth inhealthybodies, repelling malady in sick bodies and returning them to health.” The ori-gin of this bipartite definition is out of the scope of this article but it is worthnoting that it has some precedents in De sectis33 and in the texts derived fromit, where several definitions are given.34 This simple bipartite formula, with noqualification of medicine as art or science, appears in the works of the earlyphysician-philosophers of Islamicate medicine. In Firdaws al-ḥikma, al-Ṭabarī

Droz, 1997), 56–60. The theoretical part of medicine has two divisions in Masāʾil: one isthat of De Sectis; the second is a variant of the former in which theory is divided intoknowledge of natural, non-natural and anti-natural things. This latter division is due toḤunayn’s nephew, Ḥubaysh, who summarized it on the grounds of Galen’s Ars Medicathrough a complex process of interpretation.

32 Al-Rāzī, al-Manṣūrī fī l-ṭibb, ed. by Ḥāzim al-Bakrī Ṣiddīqī (Kuwait: Maʿhad al-makhṭūṭātal-ʿarabiyya-al-Munaẓẓama al-ʿarabiyya li-l-tarbiya wa-l-thaqāfa, 1989), 29, ll.5–7. See,moreover, al-Rāzī, al-Mudkhal ilā ṣināʿat al-ṭibb, ed. by María de la Concepción Vázquezde Benito (Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca-Instituto Hispano-Árabe deCultura, 1979), 5. Abū l-Qāsim al-Zahrāwī, who borrowed heavily from al-Rāzī’s Manṣūrī,included this definition in his handbook of medicine: al-Taṣrīf li-man ʿajiza ʿan al-taʾlīf,ed. by Fuat Sezgin (Frankfurt: Institut für Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wis-senschaften, 1986), 1: 4, ll.9–12.

33 Pseudo-Galen,DeSectis I 64:3–10K: “Medical art has an aim (telos), health, and a goal (sko-pos), its attainment. It is necessary for the physicians to know by what they can restorehealth in he who lacks it or to preserve it in he who has it (…). For this reason, the ancientdefinition says thatmedicine is the science of health-related anddisease related things.” Inthe last sentence of Ḥunayn’s translation, ed. by Muḥammad Salīm Sālim (Cairo: Makta-bat dār al-kutub, 1977), 12, epistēmē is rendered bymaʿrifa. This “ancient definition” is verysimilar to the tripartite definition given by Galen in Ars Medica (I, 307–309 K), borrowedfrom Herophilus, which includes the neutral state, “Medical science is the knowledge ofhealth-related, disease-related andneutral things”; trans.Heinrich vonStaden,Herophilus:The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge U.P., 1989),103–4. Other variants of the bipartite definition appear in two pseudo-Galenic books: Def-initiones medicae, XIX 351: 5–7 K, and Introductio sive medicus, ed. and transl. by CarolinePetit (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2009), 12, l.21–13, l.1. In this second book, the definitionreads, “la médicine est une science, qui veille sur la santé et éloigne les maladies.” Onp. 125, n. 1, Petit suggests a possible parallel in Soranus’Diseases of Women. Interestingly,the Alexandrian summary gives a bipartite definition attributed to Soranus, Jawāmiʿ al-Iskandarāniyyīn li-kitāb Jālīnūs fī firaq al-ṭibb, 11, ll.3–9, modified according to Overwien’stranslation,Medizinische Lehrwerke, 165–66, n. 16: “medicine is the knowledge (maʿrifa) ofhealth-related things and disease-related things.”

34 Owsei Temkin, “Studies on Late Alexandrian Medicine: 1. Alexandrian Commentaries onGalen’s De sectis ad introducendos,”Bulletin of the History of Medicine 3 (1935): 417–9.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

376 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

(d. ca. 864) presents the division into theory and practice and the definitionembedded in a conceptual Aristotelian framework: the four essential questionsthat must be posed in science according to the Posterior Analytics.35 For al-Ṭabarī, the “mā huwa” of medicine, its ti esti or essence—thus, its definition—is:36

The preservation of health and elimination of malady, and its [conditionof] being complete in virtue of two things, the theory and the practice,whichmeans the science [acquired] in the books and its exercise in heal-ings.

Al-Ṭabarī is probably inspired by a commentary similar to that of Agnellusof Ravenna,37 even though in this latter work the explanation of the fourquestions culminates in a more complex definition of medicine that we willsee below. It is not impossible that al-Ṭabarī knew the Alexandrian philoso-phers, from whom the Alexandrian iatrosophists borrowed.38 Indeed, the Jew-ish physician-philosopher of Qayrawān Isaac Israeli (d. ca. 320/932) presentsin his Book on fevers a variant of this bipartite definition also embedded in thefour questions. The interesting point in this definition is that Isaac says thatit is the answer of “philosophy” to what medicine is.39 Whether Isaac borrowsfrom the Alexandrian introductions40 or from other sources like al-Ṭabarī’s Fir-

35 Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, 89b23–25.36 Al-Ṭabarī, Firdaws al-ḥikma, ed. by Muḥammad al-Ṣiddīqī (Berlin: Sonnen-Druckerei

G.M.B.H, 1928), 6, ll.6–8.37 Agnellus of Ravenna, Lectures, 18, 14–7. See the commentary of Palladius inBaffioni, “Scolii

inediti”, 72, 5–7. On this issue, Temkin, “Studies,” 416; Nicoletta Palmieri, “Survivance d’unelecture alexandrine de l’Ars medica en latin et en arabe,” Archives d’Histoire Doctrinale etLittéraire du Moyen Âge 60 (1993): 75; and Overwien, Medizinische Lehrwerke, 27 and thebibliography mentioned there.

38 David, Davidis Prolegomena et in Porphyrii Isagogen Commentarium, ed. by Adolf Busse,CAG, vol. 18.2 (Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1904), 17, l.33–18, l.6, and Elias, Eliae In Porphyrii Isa-gogenetAristotelisCategorias commentaria, ed. byAdolf Busse, CAG, vol. 18.1 (Berlin:GeorgReimer, 1900), 3, ll.1 ff.; see Manetti, “Commentarium,” 28–9 and Overwien, MedizinischeLehrwerke, 19–20.

39 Lola Ferre, “Medicine through a Philosophical Lens: Treatise I of Isaac Israeli’s Book onFevers,” in Isaac Israeli: the philosopher physician, ed. by Kenneth E. Collins, Samuel S. Kot-tek and Helena Paavilainen (Jerusalem: Muriel & Philiip Berman Medical Library, 2015),114. According to Ferre’s translation, Isaac says: “when somebody asks ‘what is medicine?,’philosophy answers: ‘it is that which maintains the natural temperament and causes anunbalanced temperament to go back to its natural disposition.’ ”

40 Alexander Altmann and Samuel M. Stern, Isaac Israeli: a Neoplatonic Philosopher of theEarly Tenth Century: HisWorks Translated with Comments and anOutline of His Philosophy(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 13–9.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 377

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

daws41 is unclear; what, in contrast, appears clearly is the diffusion of theAlexandrian views in general, and of the Alexandrian philosophized presen-tation of medicine in particular.

2.2 Bipartite Definitions: Medicine as Art or ScienceThe commentaries on De sectis contain another bipartite definition that is par-ticularly relevant:42 “Medicine is an art concernedwith the human bodywhichbrings about health.” This second bipartite definition is a loan from the intro-ductions to philosophy written by the scholars of late Alexandria.43 Unlike thefirst bipartite definition, the second is firmly grounded because, according tothe Alexandrian philosophers, all sciences and arts have a subject matter anda finality, which are at the same time the genus and the differentia that makeup a definition according to Aristotle’s essential requirements.44 In addition,this definition is symmetricalwith the bipartitionbetween theory andpractice.The importance of this consistency for a philosophicalmindmaybe seen in IbnRushd (d. 1198). Inhis commentary on IbnSīnā’s didactical poemof medicine,45

41 Leonard Levin, R. DavidWalker and Shalom Sadik, “Isaac Israeli,” in The Stanford Encyclo-pedia of Philosophy, ed. by Edward N. Zalta. Retrieved on 20 August 2019, via https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/israeli/, §3.1.

42 Agnellus of Ravenna, Lectures, 16, ll.28–31; trans. reproduced here, 17; see, moreover, Lec-tures, 18, ll.21–2 and 40, ll.4–6; John of Alexandria, Commentaria, 1rb: 24–39; and Yaḥyāal-Naḥwī, Kitāb ikhtisār al-sittata ʿashara li-Jālīnūs talkhīs Yaḥyā al-Naḥwī, ed. Pormann,“Jean le Grammairien,” 254 §I,1. It appears moreover at the beginning of one MS of theSummaria in an introduction of sorts added by an unknown hand that reproduces thewords of a “shaykh.” Walbridge suggests that this latter may be Ibn Tilmīdh (d. 1165); seeJawāmiʿ al-Iskandarāniyyīn, 3, ll.3–5, trans., 3, n. 8.

43 Ammonius, In Porphyrii Isagogen sive V voces, ed. by Adolf Busse, CAG, vol. 4.3 (Berlin:Georg Reimer, 1891), 2, ll.1–3 and 6, ll.1–4; David, Prolegomena et in Porphyrii IsagogenCommentarium, 17, l.33–18, l.6; and Elias, In Porphyrii Isagogen et Aristotelis Categoriascommentaria, ed. by Adolf Busse (Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1900), 5, ll.23–24 and 5, l.34–6,l.1. See further references in the apparatus of John of Alexandria, Commentaria, 5.

44 See the explanation given by David, Prolegomena, 18, l.33–19, l.5, trans. Sebastian Gertz,Elias andDavid: Introductions toPhilosophy.Olympiodorus: Introductions toLogic (London:Bloomsbury, 2018), 101: “Definitions that derive from the end or from the subject matteror from both have both a genus and constitutive differentiae; for example ‘medicine is acraft that deals with the human body’. Notice how here ‘craft’ stands for the genus, andthe other words for the constitutive differentiae. Another example: ‘medicine is a craftproductive of health.’ Notice how here ‘craft’ stands for the genus, and the other wordsfor the constitutive differentiae. Another example: ‘medicine is a craft that deals with thehuman body and is productive of health’. Notice how ‘craft’ stands for the genus, and theother words for the constitutive differentiae.”

45 Ibn Rushd, Sharḥ Urjūzat Ibn Sīnā, ed. by Jaime Coullaut Cordero et al. (Salamanca: Edi-ciones Universidad de Salamanca, 2010), 44, ll.13–6.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

378 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

Herophilus’ tripartite definition is insufficient to distinguish betweenmedicineand natural philosophy because of the lack of a differentia.46 As for the ver-sion of the first bipartite definition given by Ibn Sīnā, “medicine is preservationof health, healing of disease,”47 Ibn Rushd considers it to be an incompletedefinition in need of replacement.48 The significance of the second bipartitedefinition may be appreciated through its influence on the philosophers. Notonly does it coincide with al-Kindī’s definition seen above, but it also underliesal-Fārābī’s definition of medicine as a productive art, as we will see below. Atthis point it should be noted that, paradoxically, al-Fārābī rephrases this def-inition in his introduction to the Metaphysics49 in order to explain that the“science of medicine” is a “partial science” likemathematics or physics which ischaracterized by dealing with the human body (substrate) in terms of its sick-ness or health (end).50Whether medicine is said to be a science or an art is irrelevant in Agnel-

lus’ and John’s commentaries, unless it is understood in its context. In tunewith the philosophers, they consider medicine an art but while the Alexan-drian introductions to philosophy explain the difference between art and sci-ence, and consider medicine an art,51 the commentators of De sectis holda general conception of art that subsumes science. John of Alexandria and

46 This notwithstanding, the Alexandrian summary of Ars medica, Jawāmiʿ al-Iskandarā-niyyīn li-kitāb Jālīnūs al-maʿrūf bi-l-Ṣināʿa al-ṣaghīra al-ṭibbiyya, 57, l.2–3, says that sciencestands for the genus while health-related, disease-related and neutral things stand for thedifferentiae.

47 Ibn Rushd, SharḥUrjūzat Ibn Sīnā, 46, ll.2–5. Ibn Sīnā’s phrase goes onwith “[malady] thatappears in the body out of some reason,” which adds nothing to the definition.

48 Ibn Rushd’s alternative is “medicine is the art whose work ( fiʿl) consists of maintaininghealth and healing disease on the basis of science and experience.” As we will see below,it is a version of al-Fārābī’s conception of medicine as a productive art.

49 Al-Fārābī, Maqāla (…) fī aghrāḍ al-Ḥakīm fī l-kitāb al-marsūm bi-l-ḥurūf, in Alfārābī’sphilosophische Abhandlungen aus Londoner, Leidener und Berliner Handschriften, ed. byFriedrich Dieterici (Leiden: Brill, 1890), 34, l.21–35, l.7; see Metaphysics VI 1, esp. 1025b3,where Aristotle mentions “the cause of health and physical fitness,” thus alluding indi-rectly to medicine. Aristotle contrasts in this section the project of a general scienceof being with the sciences that deal with particular aspects of being; on this issue, seeJohn C. Cleary, Aristotle andMathematics: AporeticMethod in Cosmology andMetaphysics(Leiden: Brill, 1995), 192. Al-Fārābī deals with general and particular sciences in Kitābal-Burhān, ed. by Mājid Fakhrī under the title Al-Manṭiq ʿinda l-Fārābī [vol. 4]: Kitāb al-Burhān (Beirut: Dār al-mashriq, 1987), 62ff., within a wider discussion on subordinatesciences, as we will see below.

50 Al-Fārābī, Maqāla (…) fī aghrāḍ al-Ḥakīm, 35, ll.5–6: ṣināʿat al-ṭibb [yanẓūru] fī l-abdānal-insāniyya min jihat mā tuṣaḥḥu wa-tumraḍu.

51 See particularly David, Davidis Prolegomena, 43, l.19–45, l.25.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 379

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

Agnellus of Ravenna uncritically believe in the scientific essence of medicine,as we may see in their gloss of the first textus of De sectis, in which theyaddress a dilemma noted by an unknown reader: how is it possible that Galenconsiders medicine to be, at the same time, an art and a science?52 Bothauthors give a similar answer, which in Agnellus’ commentary reads as fol-lows:53

Some people raise an objection and argue with Galen as to why he pre-viously called it an art, but here he calls it a science. We answer that allarts derive their first principles from philosophy whereas medicine alonetakes first place after philosophy. As Plato the philosopher said: “Philoso-phy and medicine are two sisters, since philosophy cures the vices of thesoul and medicine cures the ills of the body.” The Poet Homer said: “Ban-dage with care,” this is, in a scientificmanner. The comic poet said: “Learnwith care” [i.e., scientifically] “the art from whose substance you nourishyourself.”

Now, in this fragment neither Agnellus nor John give real reasons for consid-ering medicine a science, only an argument ex auctoritate.54 The unsoundnessof the “two sisters” argument is duly noted by Elias and David:55 the definitionof medicine as philosophy of the body and of philosophy as medicine of thesoul is a circular definition coined by “doctors whowish to exalt their own craftexchanging gold for bronze.”56 Put another way, John’s and Agnellus’ inconsis-tent explanation of medicine is motivated by their professional pride and itmerely expresses what they would like society to believe that medicine is.The reason why significant authors like al-Ṭabarī, Isaac Israeli, al-Rāzī, al-

Zahrāwī and Ibn Sīnā in the Poemonmedicineused the first bipartite definition,

52 See note 31 above. The unknown objector is therefore referring to the first bipartite defi-nition as formulated in De Sectis.

53 Agnellus of Ravenna, Lectures, 44, ll.6–11, trans. reproduced here, 45; John of Alexandria,Commentaria, 2va, ll.45–52.

54 The argument of the “two sisters” appears in the introduction of both commentaries:Agnellus of Ravenna, Lectures, 22, ll.20–30, John of Alexandria, Commentaria, 2ra, ll. 9–17,this latter attributing these words to Aristotle. In these mentions, both authors add thatmedicine is “philosophy of the body.” At the beginning of John’s Commentaria, 1rb, ll.23–34, medicine is named “second philosophy” because of the nobility of its subject, humanbody (Metaphysics, 1026a20–22). As for the origin of the maxim of the two sisters, see theapparatus of John of Alexandria, Commentaria, 14.

55 David, Davidis Prolegomena, 25, ll.4–15; Elias, Eliae in Porphyrii Isagogen, 9, ll.6–10.56 Trans. of David’s sentence, Sebastian Gertz, Elias and David, 108. The translator mentions

that this metaphor is borrowed from Homer’s Iliad.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

380 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

without the words “science,” “art” or “knowledge,” instead of the second bipar-tite definitionor that of Herophilus is out of the scopeof this article.57 Al-Fārābīgave “gold instead of bronze,” i.e. a definition that Elias and David would haveappreciated, so the authors who after himwrote on the status of medicine hadto bemore careful in explaining their conceptions of medicine to their readers.Al-Masīḥī (d. ca. 1010) and Ibn Hindū (d. 1019 or 1029), two authors who had asolid philosophical training,mentioned the second bipartite definition in theirintroductions to medicine.58 Ibn Sīnā’s complex solution to what medicine isin the Qānūnmight be understood in this regard.59

3 Al-Fārābī onMedicine according to the Posterior Analytics

3.1 Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr3.1.1 Medicine as a Science (ʿilm al-ṭibb)Al-Fārābī’s epitome of the Posterior Analytics, Kitāb al-Burhān, was probablypreceded in time by Kitāb al-Musīqā al-kabīr. As is well known, the treatise onmusic has a prologue on method derived from the Posterior Analytics, which,although it focuses on the analysis of music, also deals with other disciplines,namely astronomy, optics andmedicine.60 The prologue is by nomeans a con-

57 The reasonwhy Ibn Sīnā says in the Poem something different fromwhat he says inQānūnis explained by Danielle Jacquart, “Avicenne et le galénisme,” in Galenismo emedicina tar-doantica: Fonti Greche, Latine e Arabe, ed. by Ivan Garofalo and Amneris Roselli (Naples:Istituto Universitario Orientale, 2003), 265–82.

58 Al-Maṣīhī, al-Miʾa fī l-ṭibb, ed. by Floréal Sanagustin (Damascus: Institut d’Études Arabesde Damas, 2000), 1:28, ll.1–2 and Ibn Hindū, Miftāḥ al-ṭibb, ed. by Mahdī Muḥaqqiqand Muḥammad T. Dānišpažūh (Tehran: Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill UniversityTehran Branch andTehranUniversity, 1989), 22, ll.9–11. See alsoOverwien, “Eine spätantik-alexandrinische Vorlesung,” 328, n. 94. For the case of Ibn Tilmīdh, see Overwien, Medi-zinische Lehrwerke, 29.

59 Dimitri Gutas, “Medical Theory and Scientific Method in the Age of Avicenna,” in Beforeand After Avicenna, ed. by David C. Reisman and Ahmed al-Rahim (Leiden: Brill, 2003),150–4 and Jon Mc Ginnis, Avicenna (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2010), 230–3. See, moreover,Joël Chandelier, Avicenne et la médecine en Italie: le Canon dans les universités (1200–1350) (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2017), 354ff. and Peter E. Pormann, “Avicenna onMedicalPractice, Epistemology, and the Physiology of the Inner Senses,” in Interpreting Avicenna:Critical Essays, ed. by Peter Adamson (New York, Cambridge U.P., 2013), 93–5. The generalidea is that medicine is a science divided into a theory and a “theory of practice.”

60 For the treatment of astronomy and cognate issues in K. al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr, see DamienJanos, “Al-Fārābī on the Method of Astronomy,”Early Science andMedicine 15 (2010): 237–65 andMethod, Structure, andDevelopment in al-Fārābī’s Cosmology (Leiden-Boston: Brill,2012), passim.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 381

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

sistent account of Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics but it nevertheless containsinteresting insights into some relevant aspects of this book from which wecan derive a relatively thoroughgoing idea of what medicine is. Al-Fārābī doesnot define medicine in K. al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr and the closest he comes to somekind of definition is when he describes it in passing as a composite discipline(ʿilmiyya wa-ʿamaliyya).61 Interestingly, whereas he hardly deals at all with thepractical side of medicine, he devotes a notably large part of the text to explainits scientific nature. This idea is expressed by two means: on the one hand, bya key concept in Aristotle’s scientific method, the premises of the sciences; onthe other, by external elements such as the association with other sciences andterminology. On this latter point, al-Fārābī refers tomedicine twice as “art” andtwice as “science.”62 This statistic is only indicative since the terminology of K.al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr is verymisleading.63 However, an overall idea that medicineis actually a science appears from the joint analysis of medicine with threeindisputably theoretical and subordinate sciences, namely astronomy, musicand optics. In consequence, al-Fārābī conveys the idea thatmedicine is a subor-dinate science even though hemakes no further exploration of the issue.64 Thescientific status of medicine is addressed in K. al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr together withits premises. The first kind of these premises is borrowed from natural philoso-phy in tune with the subordinate character of medicine.65 The two other kindsof premises stem from two types of experience or tajriba. One is the tajribathatmeans direct experiencewith the object of knowledge. Al-Fārābī speaks, inparticular, of the premises yielded by direct experience in sensible perceptionsfrom dissection or anatomy (tashrīḥ) on the one hand, and of “the experiencewith simple medicines” on the other.66 Both types of perceptions are put onan equal footing with astronomical observations. The exact meaning of tajribahere is that of the inductive process which culminates in the understanding

61 Al-Fārābī,K.al-Mūsīqāal-kabīr, ed. byGhaṭṭās ʿAbdal-MalikKhashaba (Cairo:Dār al-kātibal-ʿarabī li-l-ṭibāʿa wa-l-nashr, 1967), 89, ll.5–14.

62 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 100, l.13 and 101, l.13, ʿilm al-ṭibb; 100, l.14 and 101, l.3, ṣināʿat al-ṭibb.63 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 89, l.13: al-Fārābī speaks of “the science of prudence and the science of

carpentry” (ʿilm al-taʿaqqul wa-ʿilm al-najāra); the term ʿilmmust be taken in these casesin its general sense of “knowledge.”

64 Aristotle, PosteriorAnalytics, I 7, I 13 passim. As iswell known, subordinate sciences are thedisciplines likemusic, optics or astronomy thatmathematize physical phenomena. Thesedisciplines are said to beposterior and inferior to themore abstract disciplines fromwhichthey borrow their premises, namely arithmetic and geometry.

65 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 100, l.13.66 Al-Fārābī, Mūsīqā, 100, ll.11–101, l.14; the author addresses moreover astronomy and op-

tics.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

382 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

of a universal premise that Aristotle calls epagōgē in the Posterior AnalyticsII 19. Al-Fārābī explains this process some lines earlier67 as the intentionalaccumulation of sense perceptions that brings the intellect to the formula-tion of true premises (muqaddamāt yaqīniyya); these may be either “perfectuniversals” (kulliyyāt kāmila) or “[premises that hold] for the most part” (ʿalāl-akthar).68 In this way al-Fārābī invokes the well-known clause of Aristotle(hōs epi to polu)69 which includes under the heading of demonstrative sciencethe knowledge of the phenomena that are not necessary. The other kind ofexperience alluded to by al-Fārābī is the tajriba that has been accumulatedby the previous generations of physicians, that is, what is commonly acceptedor “well-known” (mashhūr) among them. In Aristotelian terms, this is endoxa,usually rendered as “common” or “reputed” beliefs, which naturally belongs todialectics.70 For this reason, their use in sciences is justified byAristotle’s exam-ple, which al-Fārābī recalls in saying that he also uses reputed knowledge onthe purpose of “plants, animals and natural philosophy,” in much the sameway as do physicians with regard to already existing knowledge of anatomyand pharmacology, or the astronomers with regard to the observations of theirpredecessors.71 In this way al-Fārābī reflects not only the common practicesof the scientists of any time, but also the practice of Aristotle, who in someinstances uses endoxa and legomena (“things said”) to understand accounts orexplanations provided by someone (usually a reputed authority but also possi-bly a mere informant) that may be used as principles once they are verified insome way.72 Al-Fārābī’s confidence in the experience of his predecessors is vir

67 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 94, ll.9–95, l.3, 96, ll.8–10 and 98, ll.3–8; there is a similar explanation inBurhān, 23, l.1 ff.; see, moreover, Kitāb al-Jadal, ed. by Rafīq al-ʿAjam under the title Al-Manṭiq ʿinda l-Fārābī: al-juzʾ al-thālith, Kitāb al-Jadal (Beirut: Dār al-mashriq, 1986), 18,ll.8–11. On al-Fārābī on tajriba, see Jules Janssens, “«Experience» (tajriba) in Classical Ara-bic Philosophy (al-Fārābī—Avicenna),” Quaestio 4 (2004): 47–52. Al-Fārābī says that theprinciples of science are, on the one hand, primary cognitions that seem to be a kind ofinborn knowledge and, on the other, the universals attained via tajriba/epagōgē.

68 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 95, ll.1–3; see Posterior Analytics, 96a17–19.69 For instance, Metaphysics, 1027a1, Posterior Analytics, 87b19–22, and Nicomachean Ethics

1094b11.70 Aristotle, Topics, 100b22–24.71 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 101, ll.12–15.72 Gwilym Ellis Lane Owen, “Tithenai ta phainomena,” in Logic, Science and Dialectic: Col-

lected Papers in Greek Philosophy, ed. byMartha C. Nussbaum (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univer-sity Press, 1986), 239–44, esp. the references in n. 14 on 243. A discussion of the contro-versy raised by Owen’s article is beyond the scope of this paper. For a helpful summarythat explains al-Fārābī’s interpretation of the issue (Aristotle does actually use endoxa inscience), see Miira Tuominen, Apprehension and Argument: Ancient Theories of StartingPoints for Knowledge (Dordrecht: Springer, 2007) 57–8 and 95–102, and Allan Bäck, “Avi-

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 383

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

unlimited, since he equates it with the experience that an assistant who dirtieshis hands with a dissection, or spends a long time watching the heavens, mayfurnish to a physician or an astronomer.73 It is unclear here whether al-Fārābīis borrowing from another author or is speaking on his own. Galen also men-tions the premises obtained via anatomy and dissection in works likeMethodomedendi and De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis,74 which were translated intoArabic. As for the “experience” in medicaments, Galen speaks, again in workstranslated into Arabic like De Simplicium Medicamentorum, of a “qualified”experience (diorismēnepeira) to determine as exactly as possible thepropertiesand effects of medicaments, which is greatly indebted to Aristotle’s connectionbetween experience and universal knowledge.75 It is probable that this notionwas known to al-Fārābī,76 but there can be hardly any doubt that he had readthe example of how one obtains primary premises about the virtues of helle-bore, which the commentators of Aristotle presented in order to explain whatepagōgē is.77 The experience in anatomy and pharmacology will reappear inanother work of al-Fārābī, Kitāb al-Taḥlīl,78 to enable him to criticize the log-ical consistency of the conclusions derived by Galen. This criticism, however,is by no means incompatible with the consideration of the knowledge yieldedby experience as suitable for science in K. al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr. The gist of thecriticism of Galen is that conclusions derived from experience are formed byreasoning through signs (dalāʾil). These conclusions are therefore less certainthan the conclusion of an apodictic demonstration: from the prior, a knownphenomenon, one infers the existence of the posterior, an unknown cause, butthis does not necessarily mean the existence of causal connection betweenprior and posterior. Now, al-Fārābī knows that Aristotle and his commentatorssay that knowledge through signs is scientifically sound if prior and posteriorare convertible (if one implies the other). What ultimately the different treat-ment of experience in medicine means is that al-Fārābī, at the moment ofwriting K. al-Musīqā al-kabīr, has little interest (if any) in criticizing Galen.

cenna the Commentator,” inMedieval Commentaries onAristotle’s Categories, ed. by Lloyd.A. Newton (Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2008), 34–7.

73 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 101, ll.3–11.74 Geoffrey Ernest Richard Lloyd, “Demonstration in Galen,” in Rationality in Greek Thought,

ed. by Michael Frede and Gisela Striker (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 271.75 Philip van der Eijk, “Galen’s use of the concept of ‘qualified experience’ in his dietetic and

pharmacological works,” in Galen on Pharmacology: Philosophy, History andMedicine, ed.by Armelle Debru (Leiden [e.o.]: Brill, 1997), 50–1.

76 Karimullah, “Avicenna and Galen,” 106.77 See below in this article, section 3.1.2.78 Karimullah, “Avicenna and Galen,” 111–9.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

384 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

3.1.2 An Alexandrian View of Medicine within the Posterior AnalyticsWhat we saw in the previous section is consistent with the characterizationof medicine as a science that appears in al-Fārābī’s introduction to the Meta-physics, which seems indebted to the Alexandrian tradition. Actually, the over-all description of medicine in K. al-Mūsīqā al-Kabīr shows hints of the ideal-ization that characterizes the Alexandrian iatrosophists and their Islamicateimitators, such as the description of astronomers and physicians as elevatedscholars who leave the dirty and tedious work to their assistants, the deeprespect for the knowledge of the predecessors, the consideration of medicineas a science derived from philosophy and the lack of criticism of Galen. How-ever, al-Fārābī’s analysis of medicine is more complex than the iatrosophists’generalizations and must be understood with reference to the Posterior Ana-lytics. Within the framework of this latter work, it is to a certain extent naturalthat al-Fārābī considers medicine as a science because Aristotle provides someinsights that suggest this, even though he does not mentionmedicine togetherwith the term epistēmē.79 The commentators added interesting nuances ofwhich al-Fārābīwas aware.We still know little about the sources of K.al-Mūsīqāal-kabīr or al-Burhān but one of them is certainly Themistius’ paraphrase ofthe Posterior Analytics, explicitly quoted in the first treatise in order to exem-plify the possibility of knowing a fact which is not perceived by the senses.80The Islamicate scholars also had at hand a translation of Philoponus’ com-mentary,81 and it is possible that it was known to al-Fārābī.82 Themistius’ andPhiloponus’ commentaries are helpful to understand al-Fārābī’s conceptions of

79 At 88b11–14 of the Posterior Analytics, Aristotle speaks of the principles of geometry, arith-metic andmedicine as principles of science; on 97b26–28, hementions that the remediesdo not apply for a particular eye but for eyes in general, suggesting therefore that they arebased on universal principles.

80 Al-Fārābī, al-Mūsīqā, 103, ll.4–7. See also Themistius, Analyticorumposteriorumparaphra-sis, ed. byMaximWallies, CAG, vol. 5.1 (Berlin: George Reimer, 1900), 29, ll.15–20 andMiiraTuominen, The Ancient Commentators on Plato and Aristotle (London-New York: Rout-ledge, 2014), 95. Themistius’ commentary is also quoted in al-Burhān, 53.

81 On Philoponus’ commentary, see Henri Hugonnard-Roche, “Averroes et la tradition desSeconds Analytiques,” in Averroes and the Aristotelian Tradition: Sources, Constitution andReception of the Philosophy of Ibn Rushd (1126–1198), ed. by Gerhard Endress et al. (Leiden-Boston: Brill, 1999), 174–17. The possibility that al-Fārābī knew a commentary writtenby Porphyry has been suggested by Michael Chase, “Did Porphyry Write a Commentaryon Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics? Albertus Magnus, al-Fārābī, and Porphyry on per sePredication,” in Classical Arabic Philosophy: Sources and Reception, ed. by Peter Adamson(London-Turin: Warburg Institute-Nino Aragno Editore, 2007), 23.

82 Heidrun Eichner, “Al-Fārābī and Ibn Sīnā on ‘Universal Science’ and the System of Sci-ences: Evidence of the Arabic Tradition of the Posterior Analytics,”Documenti e Studi sullaTradizione Filosofica Medievale 21 (2010): 76.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 385

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

science andmedicine, particularly if read togetherwith their commentaries onother relevant sources of Aristotle’s scientific method like Physics, which werealso translated into Arabic. Since the study of al-Fārābī’s sources on scientificmethod is far beyond the scope of the present article, I will just mention threeissues that deserve particular attention for our purposes. The most visible isthe condition of medicine as a subordinate science. Aristotle does not addressmedicine in this way but speaks of it as an example of a case in which onediscipline may borrow premises from another without being subordinate toit.83 Themistius and Philoponus not only consider this example,84 but includemedicine together with optics, music, astronomy and the like in several pas-sages in which the subordination of the sciences is debated.85 The two otheraspects are connected less directly to the status of medicine but are never-theless crucial for the understanding of al-Fārābī’s scientific method. One isthe possible influence of Themistius’ and Philoponus’ commentaries on al-Fārābī’s interpretation of Aristotle’s first premises of science as, on the onehand, axioms that appear tobe innate inhumannature and, on theother,86 uni-versals that appear out of epagōgē.87 The third issue is Themistius’ and Philo-

83 Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, 79a13–16: the physician knows that circular wounds healslower while the geometer explains the cause of this fact; but in no way could one saythat medicine is subsumed into geometry.

84 Themistius, Analyticorum posteriorum, 6, ll.24–6 and 29, ll.20–2, and Philoponus, In Aris-totelis Analytica posteriora commentaria cum anonymo in librum II, ed. by MaximillianWallies, CAG, vol. 13.3 (Berlin: George Reimer, 1909), 182, l.10–183, l.3, including moreoverthe example of medicine and astrology for the case of the critical days.

85 Themistius, Analyticorum posteriorum, 18, ll.15–7 and 25, ll.23–7. A more explicit refer-ence tomedicine’s subordination to natural philosophymay be found in Themistius’Epit-ome of Physics, In Aristotelis Physica paraphrasis, ed. by Heinrich Schenkl, CAG, vol. 5.2(Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1900), 3, ll.17–23, trans. Robert B. Todd (London: Bloomsbury Aca-demic, 2012), 21: “so if natural science has a science prior to itself, it will take its principlesfrom it, as medicine does from natural science and optics from geometry.” Philoponusmentions the subordination many times; In Aristotelis Analytica posteriora, 100 and 146–7.

86 Zimmermann, Al-Farabi’s Commentary, 255. See also Themistius, Analyticorum posterio-rum, 7, ll.2–5, Philoponus, In Aristotelis Analytica posteriora 34, l.10–35, l.1 and 127, ll.22–4.

87 Themistius, Analyticorumposteriorum, 63, ll.2–26, and Philoponus, InAristotelis Analyticaposteriora, 435, ll.2–35 (fragment of the anonymous commentary on Posterior AnalyticsII included in this edition). On primary premises and epagōgē according to Themistiusand Philoponus, see Tuominen, Ancient Commentators, 85–103, and Apprehension andArgument, 205–15. The example of hellebore is considered by Tuominen as some kind ofdidactic commonplace used by the commentators. As for al-Fārābī, the example is impor-tant for two reasons: on the one hand, it explains the use of experience in a pharmacology;on the other, it explains how primary premises may appear to us as some kind of innateknowledge.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

386 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

ponus’ treatment of Aristotle’s “proof of the that” (Posterior Analytics I 13) as atekmeriodic proof throughwhich the cause is known by the effect.88 The gist ofthe argument is that tekmeriodic reasoning may be considered as demonstra-tive or not but that in any event it is a kind of inductive reasoning bywhich onemay find the principles of demonstration (Physics I 1), knowing the posterior innature though the prior in knowledge, and so it has a relevant role in science.A similar argumentation may be found in Alexander of Aphrodisias’ commen-taries on the Prior Analytics and the Topics on the purpose of induction, whichinfluence al-Fārābī’s differentiation between a scientific induction which onthe one hand yields primary premises of the sciences, and on the other a peda-gogic induction thatmakes the student understand these principles.89All in all,it seems that the commentators’ insights into tekmeriodic reasoning, in con-nection with Aristotle’s distinction between priority in knowledge and priorityin nature, provide some of the essential bases of al-Fārābī’s dynamic concep-tion of Aristotle’s scientificmethodwhich he explains in a summarized form inTaḥṣīl al-saʿāda: demonstration has “a less central role in the pursuit of truth,”as Galston puts it.90 That is to say, the activity of theoretical sciences consistsmainly of the establishment of principles by the ascent from theprior in knowl-edge to the prior in nature by means of inductive and dialectic reasoning. Thisconception of science is made explicit in al-Fārābī’s Burhān when he dealswith the essential themes of his epistemology, and most particularly with thenotion of “certainty,” yaqīn, which designates the result of demonstrative rea-soning instead of “knowledge” or “science.”91 Al-Fārābī differentiates between

88 The question is thoroughly discussed in DonaldMorrison, “Philoponus and Simplicius onTekmeriodic Proof,” inMethodandOrder inRenaissancePhilosophyof Nature:TheAristotleCommentary Tradition, ed. by Daniel A. di Liscia, Eckhard Kessler and Charlotte Methuen(Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997), 1–22; Tuominen, Apprehension and Argument, 140–42 andAncient Commentators, 104–5; and Francesco Bellucci and Costantino Marmo, “Sign andDemonstration in Late-Ancient Commentaries on the Posterior Analytics,” Cahiers del’ Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin 87 (2018): 1–33. As for Islamicate philosophy, seeAndreas Lammer,TheElements of Avicenna’s Physics: Greek Sources andArabic Innovations(Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter, 2018), 51–62.

89 Joep L. Lameer, Al-Fārābī and Aristotelian Sylllogistics: Greek Theory and Islamic Practice(Leiden-New York-Köln: Brill), 1994, 169–73; on Alexander, see Miira Tuominen, “Alexan-der and Philoponus on Prior Analytics I 27–30: Is There Tension betweenAristotle’s Scien-tific Theory and Practice?,” in Interpreting Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics in Late Antiquityand Beyond, ed. by Frans A.J. de Haas et al. (Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2010), 150–3.

90 Miriam S. Galston, “Al-Fārābī on Aristotle’s Theory of Demonstration,” in Islamic Philoso-phy andMysticism, ed. by Parviz Morewedge (Delmar: Caravan Books, 1981), 29–31.

91 Deborah Black, “Knowledge (ʿilm) and Certitude (yaqīn) in al-Fārābī’s Epistemology,”Ara-bic Sciences and Philosophy 16 (2006): 11.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 387

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

two kinds of certainty that may be deemed as scientific:92 on the one hand,absolute andnecessary certaintywhich results from indisputable premises anddemonstrative reasoning;93 on the other, approximate certainty, or else “a sec-onddegree of certainty,” stemming from the testimonyof everybody, that yieldsrhetoric and dialectic premises, or, else, from sense-perceptions. In this lattercase, al-Fārābī speaks of sense perceptions obtained in the past, the presentor even also the future, provided that no other sense-perception or reasoningcontradicts them.This second degree of certainty “may be employed by the sci-ences” (qad tustaʿmal fī l-ʿulūm).94 It is a relative certainty that explains why inK. al-Musīqā al-kabīr al-Fārābī speaks of the dialectic premises that consist ofthe past experience as explained by the text-books, and considers medicine tobe a science on a par with optics andmathematical astronomy, even though heknows that it is very different from both.

3.2 Kitāb al-Burhān3.2.1 Practical Arts and Composite DisciplinesAl-Fārābī develops most of the arguments of K. al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr in a sec-tion of al-Burhān devoted to analyzing the subordination and interrelationof the sciences and the difference between science and art.95 Nevertheless,al-Burhān contains a more complete and nuanced discourse which changessome of the conclusions presented in K. al-Musīqā al-kabīr. Medicine is alsoconsidered as a composite discipline in al-Burhān but, unlike K. al-Mūsīqā al-Kabīr, the practical side is carefully addressed in connection with experience.As we will see below in greater detail, al-Fārābī’s explanations are influencedby the Nicomachean Ethics. Al-Fārābī’s great caution regarding the conditionof medicine is reflected in the terminology he uses. Even though in al-Burhānthe terms ṣināʿa and ʿilm are relatively interchangeable, al-Fārābī never desig-natesmedicinewith the expression ʿilmal-ṭibb but instead calls it ṭibb or ṣināʿatal-ṭibb. Borrowing from Aristotle’s differentiation between praxis (doing) andpoiēsis (making), between the kheirotekhnēs (manual worker) and the arkhitek-

92 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 74, ll.3–9; see Black, “Knowledge,” 28ff. and Galston, Opinion andKnowledge, 210 ff.

93 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 21–2.94 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 74, ll.8–9; see, moreover, 25, ll.13–4, where al-Fārābī says that the

name ʿilm is applied to necessary certainty more often than it is used in no-certainty ornon-necessary certainty, implicitly admitting one may use “science” or “knowledge” forreferring to the lower degrees of certainty.

95 Al-Fārābī,al-Burhān, 59–75, fourth section of the bookwhichdealswith the use of demon-strations and definitions in the theoretical arts.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

388 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

tōn (master craftsman),96 al-Fārābī speaks of two kinds of practical arts. On theone hand, there is an art, different from medicine,97 that consists of repetitivework. It suffices that the crafter thinks, without further reflection, of simplemental representations of the work. These representations are the “lowest cog-nitions” (aqall al-maʿārif ) and so the art is learned through reiterated opera-tions and works (muzāwalat aʿmāl al-ṣināʿa) or imitation (iḥtidhāʾ).98 On theother hand, there is the art in which there is some kind of mental reflectionand may be thus rationalized in some way so as to be explained and trans-mitted bi-l-qawl, meaning an oral explanation that expresses some degree ofabstract conceptualization. Themain difference between the two kinds is that,in the first, all the knowledge needed in order for an art to be an organized bodyof rules able to fulfil a given purpose appears from the experience furnishedby the same art, whereas the arts of the second type necessitate external cog-nitions.99 Irrespective of their origin in experience or deduction, these exter-nal cognitions must be “prepared for practice” ([maʿārif ] maqrūna bi-stiʿdādnaḥwa l-ʿamal).100

3.2.2 Composite and Subordinate Disciplines, Science and ExperienceFor al-Fārābī, a true composite discipline is one that is “essentially connected”to theory and practice, in contrast with the sciences and arts which are con-nected to theory or practice only accidentally.101 It may be deduced from al-Burhān and K. al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr, where this question also appears, that atrue composite discipline is one that needs the conjunction of theory andpractice in order for it to achieve its particular ends. The accidental connec-tion, which is mostly explained by examples,102 may be defined as the attri-bution of the quality of “theoretical” to a practical discipline, and vice-versa,just because the practical discipline uses elements from the theoretical disci-pline for its purposes, and the theoretical discipline deals with issues that aredealt with in practical disciplines. The example that al-Fārābī offers in K. al-

96 Nicomachean Ethics, 1140a6–24 and Metaphysics, 981b1–982a3; see, moreover, the meta-phor of the physician and the builder extant in Parts of Animals I.1: both are crafters whoplan and execute a work, the first using reason and the second using the senses.

97 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 74, l.15.98 Nicomachean Ethics, 1103a31–34, on learning by doing in the case of virtue and crafts.99 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 72, ll.20–3.100 This sentence means literally “[cognitions] connected with a preparation for practice.” I

interpret it in the sense that, for example, a carpenter might borrow an intuitive knowl-edge of shapes from geometry for the purpose of making a piece of furniture.

101 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 74, ll.13–5.102 Al-Fārābī,Mūsīqā, 89, ll.5 to end; al-Burhān, 74, l.22–75, l.8.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 389

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

Mūsīqā al-kabīr is that of geometry, whose objects of study are not intendedfor practice but are nevertheless used for practical arts, some of which arenamed after “geometry.”103 Likewise, al-Fārābī mentions carpentry and pru-dence (ʿilmal-taʿqqul), probablybecause the former applies, explicitly or tacitly,theoretical notions of geometry104 and the latter applies ethical principles. Themain examples in al-Burhān105 are theoretical politics and natural philoso-phy.106In order to reflect the difference between the composite and subordinate

disciplines in the matters that deal with the same subjects, al-Fārābī uses thevery basis of Aristotle’s definition of subordinate disciplines. On the one hand,there is a science that collects perceptions that explain the fact (to hoti) ofsome phenomenon; on the other, a superior science that gives the why (todioti) of this phenomenon, even though the practitioners of the superior sci-encemay ignore the fact since their main concern is the universal.107 Al-Fārābīadapts this relationship according to the model of the pairings of theoreti-cal/practical politics and natural philosophy/medicine:108 the empirical disci-pline assists the deductive science so as to complement what the latter doesnot know by deduction; conversely, the deductive provides the empirical withthe theoretical knowledge that the latter cannot obtain via experience. Whenthis kind of connection happens, it may be thought that both disciplines areone and the same, and thus medicine may be taken as a part of natural phi-losophy. What this ultimately means is that no composite discipline is sub-ordinate to another science but is an independent, essentially practical andempirical matter which for its completion needs knowledge from other sci-ences and arts, even if this additional knowledge mostly comes from only one(in the case of medicine, natural philosophy). In order to show that there isno subordination but a kind of cooperative relationship, al-Fārābī reconsid-ers the examples put by Aristotle in the Posterior Analytics I 13 and comple-ments them with others of the same kind:109 medicine and agriculture are

103 Nicomachean Ethics, 1098a29–31: the carpenter uses the right angle for his work while thegeometer studies it.

104 Al-Fārābī, Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm, 77. Interestingly, the use of geometrical shapes in carpentry,blacksmithing and building is included in practical geometry.

105 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 74, l.20–75, l.3.106 Al-Fārābī also makes a general reference to mathematical sciences and describes another

case of a non-essential connection: music is related to theory and practice by homonymybecause theoretical music and practical music are different disciplines.

107 Posterior Analytics I 13, 74a2–6.108 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 72, ll.7–11.109 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 75, ll.13–5.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

390 forcada

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

“helpful” for natural philosophy; the navigator’s knowledge of the stars is help-ful for astrology (sic, aḥkām al-nujūm); practical music is helpful for theo-retical music.110 Here Al-Fārābī mentions only disciplines that are empiricaland applied, while disregarding Aristotle’s conventional examples of harmon-ics and arithmetic, or optics and geometry. The only question that remainsunclear is the share that medicine takes in theory. Al-Fārābī says in this con-nection that medicine speculates or theorizes in natural things “as much asis necessary for practice”111 while natural philosophy studies these things inthemselves.112 Al-Fārābi does not explain the meaning and the extent of thisclause in al-Burhān, but rather in his epistles criticizing Galen’s natural philos-ophy.113

3.2.3 Kitāb al-Burhān and al-Fārābī’s Works on Ethics and PoliticsThe essential features of al-Fārābī’s thinking on medicine and composite sci-ences seen thus far are further complemented in his books on ethics and poli-tics. The best instantiation of the kind of discipline that medicine is appears inhis Kitāb al-Milla, in a well-known excerpt that is reproduced in Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm.Al-Fārābī does not set out to saywhatmedicine and the physician are, butwhatpractical politics and the ruler should be.

Clearly, [the physician] could not have acquired this determination114from the books of medicine he studied and was trained on, nor fromhis ability to be cognizant of the universals (kulliyyāt) and general thingsset down in medical books, but through another faculty developing fromhis pursuit of medical practices with respect to the body of one indi-vidual after another, from his lengthy observation of the states of sickpersons, from the experience (tajriba) acquired by being occupied withcuring over a long period of time, and from ministering to each individ-ual.

110 Posterior Analytics, 78b38–39 and 79a1.111 Al-Fārābī, al-Burhān, 74: 23: al-ṭibb yanẓuru fi l-ashyāʾ al-ṭabīʿiyya bi-miqdār al-kāfiya fī l-

ʿamal.112 Nicomachean Ethics, 1098a26–33 and 1102a23–25; the clause is mentioned, moreover, by

al-Fārābī in Fusūl muntazaʿa, §5, 26:9–12.113 See below in this article, §5.114 Thedeterminationof a particular treatment for a particular patientwhohas been checked

by the physician; this treatment has been thoroughly described in the preceding lines. Itis worth noting that Galston, Politics and Excellence, 111–2, considers this treatment to bean example of deliberative reasoning.

Downloaded from Brill.com02/15/2022 10:11:22AMvia free access

bronze and gold 391

Oriens 48 (2020) 367–415

Therefore, the craft of the perfect physician becomes complete, to thepoint of performing with ease the actions proceeding from that craft,by means of two faculties: one is the ability for unqualified and exhaus-tive cognizance of the universals that are parts of his art so that nothingescapes him; and then there is the faculty that develops in him throughthe lengthy practice of his art (ʿan ṭūl afʿāl ṣināʿātihi) with regard to eachindividual.115

The excerpt puts some flesh on the bare bones of K. al-Mūsīqā al-Kabīr and al-Burhān on the basis of the Nicomachean Ethics.116 As a composite discipline,medicine is first and foremost an art committed to the action in particularinstances and the production of a result. The practitioner derives the rules ofthe art from the experience provided by practice. Al-Fārābī speaks of the “abil-ity for unqualified and exhaustive cognizance of the universals that are parts ofhis art,” whichmeans the capacity of the physician to do his own sciencewithinthe limits of the clause “as much as it is necessary for practice” seen above.This knowledge is complemented by the knowledge provided by handbooks.In order to better understand what al-Fārābī means, one must look again attheNicomacheanEthics, andAristotle’s distinctionbetween two faculties in therational soul, the scientific and the calculative or deliberative:117 or, accordingto al-Fārābī, the theoretical and practical faculties. This issue is addressed by al-Fārābī inmany places,118 andmost particularly in Fuṣūlmuntazaʿa and FalsafatArisṭūṭālīs in which practical reason is subdivided in a certain way. Accordingto the first source, practical reason intervenes in what is mihnī (related to thecraft) and in what is fikrī (related to thought, understanding, calculation and

115 Al-Fārābī, Kitāb al-Milla, ed. by Muḥsin Mahdī (Beirut: Dār al-mashriq, 1991), 57, l.19–58,l.6, trans. reproduced here Charles Butterworth (Ithaca-London: Cornell University Press,2001), 105; see al-Fārābī, Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm, 104, ll.3–9.

116 Nicomachean Ethics X 9, especially, 1180b7–28 and 1181a9–1181b6. First, medical treatmentand educational tuition are more efficient if particularized for one person, but theymust be prescribed by a doctor and a tutor (in the example, a boxing coach) becausethey have a universal knowledge of what is good in these cases. Second, experienceis necessary in medicine and politics, and indeed no doctor learns his healing skillsin books; however, the physicians write medical books which are only understood byexperts.