Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and emerging therapies for depressive episodes and...

Transcript of Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and emerging therapies for depressive episodes and...

Q1

Reviews�POSTSCREEN

Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014 REVIEWS

Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trialsand emerging therapies for depressiveepisodes and maintenance treatment

Ricardo P. Garay1,2, Pierre-Michel Llorca3, Allan H. Young4,Ahcene Hameg2 and Ludovic Samalin3

1 INSERM U999, Universite Paris-Sud et Hopital Marie Lannelongue, Le Plessis-Robinson, France2Craven, Villemoisson-sur-Orge, France3 Psychiatry Service, CHU Clermont-Ferrand, EA 7280, Auvergne University, Clermont-Ferrand, France4Centre for Affective Disorders, Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College London, De Crepisgny Park, London, UK

Bipolar disorder (BD) is one of the world’s ten most disabling conditions. More options are urgently

needed for treating bipolar depressive episodes and for safer, more tolerable long-term maintenance

treatment. We reviewed 30 recent clinical trials in depressive episodes (eight tested compounds) and 14

clinical trials in maintenance treatment (ten tested compounds). Positive results in Phase III trials,

regulatory approval and/or new therapeutic indications were obtained with some of the developing

drugs, particularly for depressive episodes. The current BD pipeline is encouraging with promising new

compounds, acting on novel pharmacological targets and on specific aspects of bipolar depression.

IntroductionBipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic, severe and recurring illness

(typically manic episodes alternate with episodes of depression),

which affects 3% or more of the population and is associated with

substantial morbidity and mortality [1]. The mortality rate of those

with BD is two-to-three-times higher than the rate in the general

population, owing particularly to suicide but also to accidents,

medical illness and substance abuse [2]. Indeed, BD is one of the

world’s ten most disabling conditions and one of the greatest

public health problems [3].

BD refers to a continuum of disorders [4], including: (i) the tradi-

tional bipolar I subtype (BD-I), which includes episodes of full-blown

mania and major depression; (ii) BD type II (BD-II) depressive and

hypomanic episodes; (iii) cyclothymic disorder (depressive and hy-

pomanic symptoms); and (iv) BD not otherwise specified.

The cause of BD is unknown, but genetic and environmental

risk factors are believed to have a role [5,6]. Treatment commonly

includes mood-stabilizing medication and supportive and educa-

tional therapy [7–12]. The treatment of mania is provided for by

the available treatments: (i) mood stabilizers including lithium

and anticonvulsants (valproate, carbamazepine) that are effective

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and e(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

Corresponding author: Garay, R.P. ([email protected])

1359-6446/06/$ - see front matter � 2014 Published by Elsevier Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.

in treating acute manic episodes and preventing relapses; and (ii)

some atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone,

aripiprazole) initially used to treat schizophrenia, which have also

been found to be efficacious for managing mania.

Generally speaking, the periods of depression far exceed those of

mania in terms of frequency and duration [13,14]. BD patients

commit or attempt suicide mostly during severe depressive epi-

sodes, but very rarely during states of euphoric mania or euthymia

[2]. Quetiapine and an olanzapine–fluoxetine combination (OFC;

a single capsule containing the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine

and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine) are used

to treat bipolar depressive episodes [10], but they are not exempt

from adverse effects in long-term treatment (e.g. weight gain,

dyslipidaemia and/or sedation or somnolence). Because of discor-

dant data concerning lithium and valproate, these two drugs are

placed either as first- or as second-line treatment for bipolar

depression [12,15]. Unmet treatment needs in the management

of BD include more options for treating bipolar depressive episodes

and safer, more-tolerable medications for long-term maintenance

treatment [8,16]. This review summarizes a selected number of

recent clinical trials in bipolar depressive episodes and in long-

term maintenance treatment and also discusses important ongo-

ing trials.

merging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

07.010 www.drugdiscoverytoday.com 1

SCC���

��

��

�

DW

lo

s�

�

�

��

REVIEWS Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

T

In

F

A

A

N

a

b

c

d

eQ9f Fg

h

i Tj A

2

Review

s�P

OSTSCREEN

election criterialinical trial eligibilitylinical trials were selected on the basis of the following criteria.

The primary outcome was at least one of the following:

efficacy in bipolar depressive episodes;

long-term efficacy for relapse prevention or residuals symp-

toms;

status as a long-term safety trial.

The clinical trial was recruiting or active (not recruiting), or

completed in 2012 or later.

It was a Phase II, III or IV trial.

It was a randomized trial, or an open trial versus placebo and/or

a comparative compound.

Compound development was not discontinued.

ata sources and searche identified clinical trials in bipolar depressive episodes and

ng-term BD maintenance treatment using the following main

ources.

The clinical trials databases of the NIH (National Institutes of

Health; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/), the European Medicines

Agency (EMA; EU Clinical Trials Register; https://www.clinical-

trialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search;jsessionid=sa0a1Jq2IuPPzCa-

QoIpaEOkYugzkgm_2UA9T_Bmp3ks9p4LXbe5D!-895578838)

and WHO (World Health Organization International Clinical

Registry Platform; http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

Records from the EMA (http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/) and

FDA (http://www.fda.gov/).

Medical journals, using PubMed, Science Direct and Google

Scholar.

Conferences and meetings on psychiatry.

Websites of pharmaceutical and biotech companies active in

the field of BD-targeted therapies.

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

ABLE 1

vestigational compounds for bipolar depressive episodes and mai

amily Compound Main

typical antipsychotics+antidepressant Quetiapine D2 an

Olanzapine D2 an

Paliperidone D2 an

Lurasidone D2 anAsenapine D2 an

Aripiprazole D2 an

OFCa D2 an

nticonvulsants Lamotrigine Sodium

ew investigational compounds Armodafinil Unkno

Ramelteon Melato

Lisdexamfetamine TAAR1

Cariprazine D2 anScyllo-inositol Amylo

Mifepristone Proge

Olanzapine–fluoxetine combination.

Dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A antagonist (see ref. for other actions on neurotransm

Dopamine D2 and D3 partial antagonist (see ref. for other actions on neurotransmitter re

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Progesterone and glucocorticoid receptor antagonist.

DA and/or EMA approval status before 2012 is given in Figs 1,2.

Treatment-resistant depression.

Cariprazine is currently under investigation for the treatment of BD and schizophrenia an

race-amine-associated receptor 1.

ttention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com

Identification of clinical trials and compoundsClinical trials are given with their proper name or a

literature reference, or the ClinicalTrial.gov identifier, in decreas-

ing order of priority. Compounds are given with their generic

name and the biotech or pharmaceutical company in charge of

development. Trade name is indicated when available.

Compound classificationCompounds reviewed here are divided into FDA- and/or EMA-

approved compounds (for the bipolar depressive episodes, for BD

maintenance treatment or for other psychiatric disorders) and new

investigational compounds (for the treatment of bipolar depres-

sive episodes and/or for maintenance treatment). Finally, the

phase of development is indicated together with its status.� With results.� Completed.� Ongoing, with the estimated study completion date.

Recent clinical trials in bipolar depressive episodesOur search identified 30 eligible clinical trials in bipolar depres-

sive episodes (accessed between 19th February and 7th May

2014) corresponding to eight developing compounds.� The olanzapine–fluoxetine combination (OFC, Symbyax1, Eli

Lilly) – for review of previous studies see [17].� Quetiapine extended-release (XR) (quetiapine XR, Seroquel

XR1, AstraZeneca) [18].� Asenapine (Saphris1, Forest, USA; Sycrest1, Lundbeck, EU) [19].� Lurasidone (Latuda1, Sunovion) [20].� Armodafinil (Nuvigil1, TEVA) [21].� Ramelteon (Rozerem1, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Japan) [22].� Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (Vyvanse1, Shire Pharmaceuti-

cals, UK) [23].� Cariprazine (Forest Laboratories, USA) [24].

emerging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

ntenance treatment of bipolar disorder (BD) reviewed in this article.

receptor actions Main medication usesf Refs

d 5-HT2A antagonistb BD and schizophrenia [18]

d 5-HT2A antagonistb BD and schizophrenia [33]

d 5-HT2A antagonistb BD and schizophrenia [35]

d 5-HT2A antagonistb BD and schizophrenia [20]d 5-HT2A antagonistb BD and schizophrenia [19]

d D3 partial agonistc BD and schizophrenia [34]

d 5-HT2A antagonistb + SSRId Bipolar depression and TRDg [17]

channel blocker BD, epilepsy and seizures [32]

wn (dopamine suspected) Sleep disorders [21]

nin MT1/MT2 agonist Insomnia [22]i activator ADHDj disorder [23]

d D3 partial agonistc Under investigationh [24]id antiaggregation agent Under investigationh [36]

sterone and glucocorticoide Abortifacient and contraceptive [38]

itter receptors).

ceptors).

d scyllo-inositol is under investigation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014 REVIEWS

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

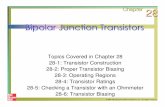

FDA- and/or EMA- approval status before 2012Compounds in clinical trials for

bipolar depression in 2012 or later

• Olanzapine-fluoxetine combination (OFC)

• Quetiapine

• Lurasidone• Asenapine

New investigationalcompounds

Compoundsapproved inpsychiatricindications

Other

Bipolardepressiveepisodes

• Armodafinil• Ramelteon• Lisdexamfetamine• Cariprazine

Drug Discovery Today

FIGURE 1

FDA and/or European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval status (before 2012) for compounds undergoing clinical trials in bipolar depressive episodes (in 2012 or

later). Compounds were divided into two different categories according to their approval status: compounds approved in psychiatric indications (bipolar

depressive episodes or other) and new investigational compounds.

Reviews�POSTSCREEN

Mechanism of action and medical uses of the above

compounds are given in Table 1. FDA and/or EMA

approval status before 2012 is given in Fig. 1. Unless otherwise

indicated, Phase III/IV trials in bipolar depressive episodes

were conducted using a similar protocol: a randomized,

placebo-controlled study, a large number of patients with a current

depressive episode (n � 150) and a six-to-eight-week treatment

period. Efficacy status and/or results are summarized in Table 2.

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and e(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

TABLE 2

Efficacy of compounds undergoing clinical trials in bipolar depressi

Phase Compound Identifier Population

IV OFCa (SymbyaxW) NCT00844857 Pediatric BD-I (DE

III Quetiapine XR (Seroquel XRW) NCT00811473 Pediatric BD-I/II (

Lurasidone (LatudaW) PREVAIL 1 Adult BD-I (DEb)

PREVAIL 2 Adult BD-I (DEb)

PREVAIL 3 Adult BD-I (DEc)

Armodafinil (NuvigilW) NCT01072929 Adult BD-I (DEb)

NCT01072630 Adult BD-I (DEb)

Ramelteon (RozeremW) NCT01305408 Adult BD-I (DEb)

NCT01467700 Adult BD-I (DEb)

NCT01677182 Adult BD-I (DEb)

II Cariprazine NCT01396447 Adult BD-I (DEb)

Asenapine NCT01807741 Adult BD-I (DEb)

a Olanzapine–fluoxetine combination.b Depressive episode.c Patients resistant to lithium or divalproex alone.d Statistically significant.e Change in children depression rating scale (revised) total score (mean � SE).f Change in Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale total score (mean � SE).g 30-Item inventory of depressive symptomatology-clinician-rated at all post-baseline visits uhData not communicated.i Completion date (past or estimated).

OFCOne Phase IV trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00844857)

showed significant efficacy of the OFC in BD-I children or adoles-

cents aged 10–17 years (Table 2).

QuetiapineOne Phase III trial ( NCT00811473) did not show significant

efficacy of quetiapine XR in BD-I or BD-II children or adoles-

merging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

ve episodes (during and after 2012).

Results

Criteria Placebo Test compound

b) CDRS-R scoree �23.40 � 1.49 �28.43 � 1.13d

DEb) CDRS-R scoree �27.3 � 1.60 �29.6 � 1.65

MADRS scoref �13.5 � 0.9 �17.1 � 0.9d

MADRS scoref �10.7 � 0.8 �15.4 � 0.8d

MADRS scoref �10.4 � 0.8 �11.8 � 0.8

IDS-C30 scoreg Positive result (P = 0.0097)h

IDS-C30 scoreg Negative resulth

IDS-C30 scoreg Negative resulth

MADRS scoref May 2015i

MADRS scoref November 2015i

MADRS scoref Positive resulth

MADRS scoref July 2015i

p to week 8.

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com 3

c

s�

�

r

d

p�

�

�

�

�

�

a�

�

�

AIn

e

d

p

LT

B

II

lu

a

a

d

g

t

lu

s

c

t

REVIEWS Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

4

Review

s�P

OSTSCREEN

ents aged 10–17 years (Table 2). We can also mention two pilot

tudies.

NCT00671853, showing small effects on bipolar depressive

episodes and co-morbid generalized anxiety disorder (no

statistical analysis was provided to ClinicalTrials.gov).

A small pilot study in 42 patients with bipolar depression

showing that quetiapine XR monotherapy was more effective

than lithium and suggested that quetiapine XR can improve

subjective and objective sleep quality [25].

A large number of other studies are now ongoing or were

ecently completed with quetiapine and quetiapine XR in bipolar

epression in specific populations. Six of these studies were com-

leted, but the results were not posted to ClinicalTrials.gov.

NCT00232414 – quetiapine in BD-I depressive episodes in

children and adolescents (Phase III study).

NCT01527448 – quetiapine XR in BD-II women with postpar-

tum depression (open-label study).

NCT01195363 – adjunctive quetiapine XR in mixed states of BD

(Phase IV study).

NCT00186043 – quetiapine for the treatment of dysphoric

hypomania in BD-II patients (Phase IV study).

NCT00608296 – brain structure, function and chemistry of BD

patients who are receiving quetiapine or lithium.

NCT00751504 – psychotic features of depression under

quetiapine treatment (pilot study, n = 20).

Three other studies were communicated to ClinicalTrials.gov

nd are currently recruiting participants:

NCT00817323 investigates whether quetiapine exerts its

antidepressant activity in bipolar disorder through altering

either serotonergic or catecholinergic activity.

NCT01213121 examines within-subject changes in neurophys-

iologic parameters in patients with bipolar depression treated

with quetiapine.

NCT01357967 – this Phase IV study investigates quetiapine XR

in depressive patients showing aberrant N100 amplitude slope

(the N100 amplitude slope is used as a marker of central

serotonergic activity).

senapine September 2013 a Phase II trial ( NCT01807741) was initiated

valuating the efficacy of asenapine versus placebo in BD-I

epressive episodes (Table 2). This study is currently recruiting

articipants.

urasidonehe efficacy of lurasidone for the acute treatment of adults with

D-I depression was established in two placebo-controlled Phase

I trials: PREVAIL 1 (NCT00868452) investigating adjunctive

rasidone in patients treated with either lithium or valproate;

nd PREVAIL 2 (NCT00868699) testing lurasidone as monother-

py (Table 2) [26] (http://www.latuda.com/). In these two trials,

iscontinuation rates as a result of adverse events in the lurasidone

roup were small (<7%) and were not different from those of

he placebo group. The most common adverse events in the

rasidone group were headache, nausea, somnolence and akathi-

ia. The changes in lipid profiles, weight and parameters of gly-

emic control were minimal, and these findings were in-line with

hose observed in schizophrenia trials.

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com

In a third Phase III study (Prevail 3, NCT01284517) of patients

with BD-I depression, who were nonresponders to lithium or

divalproex alone, adjunctive lurasidone showed no significant

differences with a placebo (Table 2). Other Phase III/IV studies

are planned or in progress in children and adolescents with bipolar

disorder (NCT01932541, NCT02046369).

ArmodafinilA Phase II study showed that adjunctive armodafinil significantly

improved depressive symptoms over a placebo in patients with

bipolar depression [21]. Three Phase III trials of armodafinil were

recently completed in adults with major depression associated

with BD-I: 3071 (NCT01072929), 3072 (NCT01072630) and

3073 (NCT01305408). Two out of the three Phase III trials did

not reach statistical significance in their primary endpoint (Table

2) (http://ir.tevapharm.com). Interestingly, armodafinil reached

statistical significance in several important secondary endpoints,

such as responder rate and remission.

RamelteonA small pilot study in ambulatory BD-I with insomnia showed that

ramelteon improved the global rating of depressive symptoms

[27]. Recently, two Phase III studies were initiated for sublingual

adjunctive ramelteon in bipolar depressive episodes:

NCT01467700 and NCT01677182 (Table 2).

LisdexamfetaminePilot Phase IV studies suggested that lisdexamfetamine can miti-

gate depressive symptom severity in BD (NCT01051440) [23]. In

2010, a 30–36-month Phase III trial was initiated evaluating lis-

dexamfetamine as an adjunctive treatment of bipolar depression

(NCT01093963, NCT01131559). The sponsor halted both studies

in March 2014 (http://article.wn.com/view/2014/02/08/Shire_-

scraps_Vyvanse_for_depression_after_failed_trials/).

CariprazineForest and Gedeon recently completed their Phase IIb trial in

patients with bipolar depression and announced positive results

(http://news.frx.com/press-release/r-and-d-news/forest-laborato-

ries-inc-and-gedeon-richter-plc-announce-positive-phase-ii), but

at time of writing the results had still not been communicated

to ClinicalTrials.gov (Table 2).

Therapeutic advances and future perspectives inbipolar depressionThe atypical antipsychotic lurasidone demonstrated efficacy in

reducing depressive symptomatology in adult BD-I (Table 2) and

received FDA approval for this indication in 2013, either as

monotherapy or as adjunctive to lithium or valproate Q2(http://

www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda). Lurasidone is a dopamine

D2 receptor (D2R) and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor (5-HT2AR)

antagonist, which can be differentiated from other available

atypical antipsychotics by a strong antagonist activity at 5-HT7

receptors (5-HT7R) and partial agonist activity at 5-HT1A recep-

tors (5-HT1AR), compatible with favorable effects on cognitive

function and an antidepressant action. By contrast, lurasidone

has a low affinity for adrenergic a1R, a2cR and 5-HT2cR, and no

affinity for histamine H1R or muscarinic M1R, suggesting a

emerging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

Q3

Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014 REVIEWS

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

Q8

Reviews�POSTSCREEN

better tolerability profile than other second-generation antipsy-

chotics.

The OFC combination showed efficacy in pediatric BD-I

depressive episodes (Table 2) and received FDA approval in

2013 for this indication (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drug-

satfda). Further development of OFC in bipolar depression

should consider the well-known adverse effects of long-term

OFC treatment in adults with schizophrenia (weight gain, dys-

lipidaemia and somnolence) [28].

Conversely, quetiapine XR, which was already FDA- and EMA-

approved for the treatment of adult bipolar patients, failed to

demonstrate a statistically significant difference with a placebo

in pediatric BD-I and/or BD-II depressive episodes (Table 2). The

antidepressant mechanism of quetiapine is poorly understood,

and several trials are ongoing to understand its effects in humans.

Data were also obtained with armodafinil, which showed

negative results in two out of the three Phase III trials

(Table 2). The compound reached statistical significance in

several important secondary endpoints, such as responder rate

and remission, but Teva decided not proceed with regulatory

filings in this therapeutic indication.

The antipsychotic cariprazine recently completed a Phase IIb

trial in patients with bipolar depression (Table 2) and Forest and

Gedeon announced positive results (http://news.frx.com/press-

release/r-and-d-news/forest-laboratories-inc-and-gedeon-richter-

plc-announce-positive-phase-ii), but at time of writing the results

had still not been communicated to ClinicalTrials.gov. Caripra-

zine is a dopamine D2 partial agonist, similar to aripiprazole, but

with preferential affinity for dopamine D3 receptors [24].

Ramelteon is the first in a new class of sleep agents that

selectively binds to the MT1 and MT2 receptors in the suprachias-

matic nucleus [22,29–31]. Two Phase III studies were initiated for

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and e(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

FDA- and/or EMA- approval status before 20

Compoundsapproved inpsychiatricindications

New investigationalcompounds

Other

BDmaintenance

treatment

FIGURE 2

FDA and/or European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval status (before 2012) for

disorder (BD) (in 2012 or later). Compounds were divided into two different categ

indications (maintenance treatment or other) and new investigational compound

sublingual ramelteon in adult BD-I patients with acute depressive

episodes (Table 2). The rational of these studies is supported by

studies showing that abnormalities in circadian rhythms are

prominent features of bipolar disorder [29] and by a small pilot

study in ambulatory BD-I with manic symptoms and insomnia

showing that ramelteon improved the global rating of depressive

symptoms [27].

Recent clinical trials in maintenance treatmentA total of 14 clinical trials fulfilling our selection criteria were

identified in the above databases (accessed between 19th Febru-

ary and 7th May 2014). These corresponded to ten compounds

active in clinical trials for maintenance treatment in 2012 or

later.� Lamotrigine (Lamictal1, GlaxoSmithKline) – for review of

previous studies see [32].� Olanzapine (Zyprexa1, Lilly) [33].� Quetiapine (Seroquel1, AstraZeneca) [18].� Aripiprazole (Abilify1, Otsuka) [34].� Lurasidone (Latuda1, Sunovion) [20].� Paliperidone extended release (ER, Invega Sustenna1 in USA,

Xeplion1 in Europe, Janssen), the primary active metabolite of

the older antipsychotic risperidone [35].� Ramelteon (Rozerem1, Takeda Pharmaceuticals) [22].� Cariprazine (Forest Laboratories) [24].� Scyllo-inositol (ELND005, AZD-103, Elan Pharmaceuticals)

[36].� Mifepristone (Mifeprex1, Korlym1) [37,38].

Mechanism of action and medical uses of the above compounds

are given in Table 1. FDA and/or EMA approval status before 2012

is given in Fig. 2. Efficacy status and/or results are summarized in

Table 3.

merging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

12Compounds in clinical trials for

bipolar depression in 2012 or later

• Ramelteon• Cariprazine• Scyllo-inositol• Mifepristone

• Lurasidone• Paliperidone extended release

• Lamotrigine• Olanzapine• Quetiapine• Aripiprazole

Drug Discovery Today

compounds undergoing clinical trials in maintenance treatment of bipolarories according to their approval status: compounds approved in psychiatric

s.

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com 5

LO

v

e

c

n

QS

q

B

p�

a�

�

�

AO

ic

w

p

z

LS

o

(T�

REVIEWS Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

TABLE 3

Compounds undergoing clinical trials for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder (during and after 2012).

Condition Phase Compound Identifier or ref. Results

Relapse prevention IV Lamotrigine versus olanzapine NCT01864551 Completed in September 2012

III Paliperidone ER (InvegaW) [39] Significant for MEa, not for DEb

III Quetiapine (FK949E) NCT01725308 October 2016c

III Aripiprazole (AbilifyW) NCT01567527 February 2016c

III Lurasidone (LatudaW) PERSIST May 2015c

III Ramelteon (RozeremW) NCT01467713 February 2015c

II Quetiapine (FK949E) NCT01737268 October 2016c

II Scyllo-inositol (ELND005, AZD-103) NCT01674010 August 2014c

Safety trial III Lurasidone (LatudaW) NCT00868959 Completed in February 2013

III PERSISTxt August 2015c

III Cariprazine NCT01059539 Completed in March 2012

Not specified Quetiapine XR (Seroquel XRW) NCT01447082 Completed in December 2012

Cognitive function II Mifepristone (MifeprexW, KorlymW) [38] Memory improvement

aManic episode.b Depressive episode.c Estimated completion date.

6

Review

s�P

OSTSCREEN

amotrigine versus olanzapinene Phase IV trial ( NCT01864551) compared lamotrigine

ersus olanzapine for relapse prevention of depressive

pisodes (time frame = 12 months) (Table 3). The trial was

ompleted in 2012, but at time of writing the results were

ot posted to ClinicalTrials.gov.

uetiapineome studies are now ongoing or were recently completed with

uetiapine and quetiapine XR in the maintenance treatment of

D. One of these studies was completed, but the results were not

osted to ClinicalTrials.gov:

NCT01447082 – epidemiological safety study of quetiapine XR

(estimated time frame is 1.5 years).

Three other studies were communicated to ClinicalTrials.gov

nd are currently recruiting participants:

NCT01725308 – quetiapine (FK949E) in BD-I or BD-II patients

with major depressive episodes;

NCT01737268 – quetiapine (FK949E) in elderly BD patients

with major depressive episodes (open-label study, 52 weeks);

NCT01938859 – quetiapine, lithium or shuganjieyu capsules

(Chinese medicine) in bipolar patients currently suffering from

depressive episodes.

ripiprazolene Phase III study (NCT01567527) was communicated to Clin-

alTrials.gov and is currently recruiting participants. The trial

ill assess the time to recurrence of any mood episode in BD-I

atients who have maintained stability on intramuscular aripipra-

ole for at least 8 weeks.

urasidoneeveral long-term studies are in progress to assess the efficacy

f lurasidone in the maintenance treatment of BD-I depression

able 3).

NCT00868959. A 24-week extension study of PREVAIL 1

and 2 trials. The primary outcome of this study is to

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and em(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com

evaluate safety and tolerability of lurasidone. This study was

recently completed. Of 813 participants analyzed, 529

participants with serious and nonserious treatment-emergent

adverse events completed 24 weeks of extension study

treatment.

PERSISTExt (NCT01575561). A 12-week extension study of the

PREVAIL 3 trial. The primary outcome of this open-label study

is to evaluate treatment-emergent adverse events. At the time of

writing, this study was currently recruiting participants.

�

� PERSIST (NCT01358357). This is a 28-week, Phase III study

designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lurasidone (in

combination with lithium or divalproex) for the maintenance

treatment of BD-I. This study was currently recruiting

participants.

Paliperidone ERBerwaerts et al. [39] conducted a Phase III study of paliperidone

extended release Q4(ER) as maintenance treatment in adult BD-I

patients with manic or mixed episodes who achieved remission

with flexibly dosed paliperidone ER (3–12 mg/day) or olanzapine

(5–20 mg/day) (NCT00490971). Responders to paliperidone ER

were randomized (1:1) to a fixed-dose paliperidone ER (n = 152)

or a placebo (n = 148); those on olanzapine continued to receive it

at a fixed dose (n = 83) (maintenance phase). Median time to

recurrence of any mood symptoms (primary endpoint) was 558

days (paliperidone ER) and 283 days (placebo) and not observed

with olanzapine (<50% of patients experienced recurrence). Time

to recurrence of any mood symptoms was significantly longer with

paliperidone ER than the placebo (P = 0.017); the difference was

significant for preventing recurrence of manic, but not depressive,

symptoms. Treatment-emergent adverse events (maintenance

phase) occurred more often in the olanzapine group (64%) than

in the placebo (59%) or paliperidone ER (55%) groups.

RamelteonA Phase III study of ramelteon was recently initiated for

the maintenance treatment of BD-I in adults (NCT01467713)

erging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014 REVIEWS

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

Reviews�POSTSCREEN

(Table 3). The primary endpoint is the time from randomization to

relapse over 9 months.

Scyllo-inositolIn 2012, a Phase II trial was initiated for the adjunctive mainte-

nance treatment of BD-I with scyllo-inositol (NCT01674010), as

compared with placebo, lamotrigine or valproic acid (Table 3).

The primary endpoint is the time to recurrence of any mood

episode up to 48 weeks.

CaripiprazineThe NCT01059539 study evaluated the long-term safety, tolera-

bility and pharmacokinetics of cariprazine in patients with bipolar

I disorder (n = 403, time frame = 16 weeks). The study was com-

pleted in March 2012 (Table 3). No results were posted at time of

writing to ClinicalTrials.gov.

MifepristoneWatson et al. [38] examined the longer-term efficacy of 600 mg/

day of mifepristone as an adjunctive treatment for one week in a

placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind trial in 60 patients

with bipolar depression, with spatial working memory (SWM) as

the primary outcome measure. Mifepristone treatment was asso-

ciated with a sustained improvement in SWM performance. The

magnitude of this neuropsychological response was predicted by

the magnitude of the cortisol response to mifepristone. The re-

sponse occurred in the absence of a significant improvement in

depressed mood.

Therapeutic advances and future perspectives inmaintenance treatmentPaliperidone ER significantly prevented relapse in clinically stable

bipolar patients. Interestingly, the compound was efficacious for

preventing recurrence of manic but not depressive symptoms

(Table 3). Paliperidone ER is not approved for the treatment of

BD-I in the USA or the EU.

Extension studies with lurasidone are testing its long-term

tolerability and safety in bipolar patients (Table 3). Positive results

are expected because lurasidone differs from the other second-

generation antipsychotics by having a good tolerability profile, in

particular for cardio-metabolic tolerability [20,40]. However, lur-

asidone seems to have a significant although moderate link with

the occurrence of akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms and hyper-

prolactinemia at the start of treatment [20]. Lurasidone should be

tested for its long-term tolerability and safety in BD in comparative

studies versus quetiapine or olanzapine.

Several trials are ongoing with quetiapine for maintenance

treatment of BD (Table 3). Further head-to-head trials of quetia-

pine versus other drug regimens that are effective in bipolar

depression would be of considerable interest.

One interesting Phase IV trial compares olanzapine versus

lamotrigine in the prevention of depressive episodes (Table 3).

The investigators hypothesized that olanzapine will be superior to

lamotrigine in the prevention of any kind of recurrence of bipolar

disorder. By contrast, the lamotrigine group will have better

prevention of depressive episodes than the olanzapine group.

The study was completed, but at time of writing results were

not posted to ClinicalTrials.gov.

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and e(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

Long-term maintenance treatment does not only imply relapse

prevention but also improvement of residual symptoms. In this

respect, ongoing studies with ramelteon will decide if the com-

pound mitigates insomnia. Similarly, there is hope that mifepris-

tone will confirm preliminary results on cognitive function.

Ramelteon has a strong rational to be tested in this indication.

Disrupted circadian rhythms are associated with an increased risk

of relapse in bipolar disorder, and a Phase IV pilot study (n = 83)

showed that patients treated with ramelteon were approximately

half as likely to relapse as patients treated with a placebo through-

out a 24-week treatment period [29].

Scyllo-inositol is an amyloid beta peptide aggregation inhibitor

under investigation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

and BD. The drug has been shown to prevent, reduce and reverse

AD processes, such as amyloid beta load and loss of cognitive

function in animal models. By contrast, the cognitive, affective

and functional impairment in BD could be difficult to differenti-

ate from those in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease [41].

Moreover, both diseases show response to lithium treatment [41].

An ongoing Phase II study with scyllo-inositol will indicate if the

compound reduces relapse in BD.

Remaining treatment needsBesides bipolar depression and long-term maintenance, there are

other unmet needs of BD, like comorbidities, residual symptoms

and cognition. Although this topic is out of the scope of our study,

it is interesting to mention that lisdexamfetamine reduced

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptom severity

(in comorbid BD) in a pilot Phase IV study (NCT01051440) [23]

and that mifepristone improved cognition [38]. Adjunctive psy-

chosocial interventions are providing substantial progress in the

management of BD [8], and their combination with the new

pharmacological treatments warrants further clinical research.

Drug development limitations in BDDrug development in BD is hampered by the scarce knowledge of

basic disease mechanisms and the unconvincing animal models

[8]. The advances in pathophysiological [8] and diagnostic aspects

of BD [42,43] could contribute to define therapeutic targets and

treatment options of BD better. One successful example is the

study by Watson et al. [38] suggesting that mifepristone could

enhance spatial working memory in bipolar depression by a per-

sistent enhancement of hippocampal mineralocorticoid receptor

function.

More treatment outcome research is needed in BD. Comparative

studies are lacking, particularly for long-term tolerance. Clinical

trials of adjunctive therapies for treatment refractory cases are also

lacking [9]. Patients in clinical trials usually differ from those in

real life who are frequently poly-medicated and suffer multiple

comorbidities. Randomized, controlled research is needed to pro-

vide guidelines for possible use of mood stabilizers and/or anti-

psychotics in patients with comorbidities [44].

Concluding remarksA great deal of work is going on in the area of BD-targeted

therapies. We identified 30 recent clinical trials testing eight

compounds in depressive episodes. Among these, lurasidone

showed efficacy and was approved by the FDA for adult BD-I

merging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com 7

d

p

m

c

r

II

t

b

c

a

r

a

o

t

R

1

1Q6

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

REVIEWS Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

8

Review

s�P

OSTSCREEN

epressive episodes. OFC showed efficacy and was approved for

ediatric BD-I depressive episodes.

Fourteen other recent clinical trials tested ten compounds in

aintenance treatment. Paliperidone ER prevented relapse in

linically stable patients. A Phase III trial with the melatonin

eceptor agonist ramelteon is ongoing in BD-I in adults. A Phase

study suggested that the progesterone and glucocorticoid recep-

or antagonist mifepristone improves spatial working memory in

ipolar depression. A large number of other clinical trials should be

ompleted in the near future.

Recent clinical trials reviewed here are providing therapeutic

dvances, particularly for depressive episodes. Moreover, the cur-

ent pipeline is encouraging with promising new compounds,

cting on new pharmacological targets and on specific aspects

f bipolar depression. After years of slow development and with

he help of governments and public organizations, we hope that

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com

current research will lead to advances that mean that BD will lose

its status as one of the top ten disabling conditions.

Conflict of interestThe authors have received no payment in preparation of this

manuscript. Ricardo Garay and Ahcene Hameg are members of

a non-profit association for therapeutic innovation (Craven, Vil-

lemoisson-sur-Orge, France), and have no conflicts of interest to

declare concerning this study. Pierre-Michel Llorca declares grants,

consulting, expertise and conferences from Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly,

Lundbeck, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka. Ludovic Samalin has

received honoraria for conferences and consulting from AstraZe-

neca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck and Otsuka. Allan

Young declares paid lectures and advisory boards for all major

pharmaceutical companies with drugs used in Q5affective and related

disorders.

eferences

1 Fagiolini, A. et al. (2013) Prevalence, chronicity, burden and borders of bipolar

disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 148, 161–169

2 Gonda, X. et al. (2012) Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: epidemiology,

characteristics and major risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 143, 16–26

3 Kupfer, D.J. (2005) The increasing medical burden in bipolar disorder. J. Am. Med.

Ass. 293, 2528–2530

4 Phillips, M.L. and Kupfer, D.J. (2013) Bipolar disorder diagnosis: challenges and

future directions. Lancet 381, 1663–1671

5 Craddock, N. and Sklar, P. (2013) Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet 381,

1654–1662

6 Alloy, L.B. et al. (2005) The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: environmental,

cognitive, and developmental risk factors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 25, 1043–1075

7 APA (2002) American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment

of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am. J. Psychiatry 159 (Suppl. 4), 1–50

8 Geddes, J.R. and Miklowitz, D.J. (2013) Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet 381,

1672–1682

9 Keedwell, P.A. and Young, A.H. (2014) Emerging drugs for bipolar depression: an

update. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 19, 25–36

0 Mc Intyre, R.S. et al. (2013) A review of FDA-approved treatment options in bipolar

depression. CNS Spectr. 18 (Suppl. 1), 4–20

1 NICE Bipolar Disorder (2006) Clinical Guidance no. 38. Available at: http://

www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG38

2 Samalin, L. et al. (2011) Lithium and anticonvulsants in bipolar depression.

Encephale 37 (Suppl. 3), 203–208

3 Baldessarini, R.J. et al. (2010) Bipolar depression: overview and commentary.

Harvard Rev. Psychiatry 18, 143–157

4 Leboyer, M. and Llorca, P.M. (2011) Bipolar depression. Encephale 37 (Suppl. 3),

161–162

5 Selle, V. et al. (2014) Treatments for acute bipolar depression: meta-analyses of

placebo-controlled, monotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, lithium and

antipsychotics. Pharmacopsychiatry 47, 43–52

6 Ketter, T.A. (2010) Nosology, diagnostic challenges, and unmet needs in managing

bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, e27

7 Silva, M.T. et al. (2013) Olanzapine plus fluoxetine for bipolar disorder: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 146, 310–318

8 Sanford, M. and Keating, G.M. (2012) Quetiapine: a review of its use in the

management of bipolar depression. CNS Drugs 26, 435–460

9 Stoner, S.C. and Pace, H.A. (2012) Asenapine: a clinical review of a second-

generation antipsychotic. Clin. Ther. 34, 1023–1040

0 Samalin, L. et al. (2011) Clinical potential of lurasidone in the management of

schizophrenia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 7, 239–250

1 Calabrese, J.R. et al. (2010) Adjunctive armodafinil for major depressive

episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: a randomized, multicenter, double-

blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 1363–

1370

2 Miyamoto, M. (2009) Pharmacology of ramelteon, a selective MT1/MT2 receptor

agonist: a novel therapeutic drug for sleep disorders. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 15,

32–51

23 Mc Intyre, R.S. et al. (2013) The effect of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate on body

weight, metabolic parameters, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

symptomatology in adults with bipolar I/II disorder. Human Psychopharmacol. Clin.

Expl. 28, 421–427

24 Citrome, L. (2013) Cariprazine in bipolar disorder: clinical efficacy, tolerability, and

place in therapy. Adv. Therapy 30, 102–113

25 Kim, S.J. et al. (2014) Effect of quetiapine XR on depressive symptoms and sleep

quality compared with lithium in patients with bipolar depression. J. Affect. Disord.

157, 33–40

26 Woo, Y.S. et al. (2013) Lurasidone as a potential therapy for bipolar disorder.

Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 9, 1521–1529

27 Mc Elroy, S.L. et al. (2011) A randomized, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive

ramelteon in ambulatory bipolar I disorder with manic symptoms and sleep

disturbance. Intl. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 26, 48–53

28 Leucht, S. et al. (2013) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic

drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 382,

951–962

29 Norris, E.R. et al. (2013) A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of

adjunctive ramelteon for the treatment of insomnia and mood stability in patients

with euthymic bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 144, 141–147

30 Liu, J. and Wang, L.N. (2012) Ramelteon in the treatment of chronic insomnia:

systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Practice 66, 867–873

31 Krystal, A.D. (2005) Q7Ramelteon. Hypnotic agent targets delayed sleep onset. Curr.

Psychiatry 4, 11

32 Reid, J.G. et al. (2013) Lamotrigine in psychiatric disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74,

675–684

33 Tohen, M. et al. (2013) Efficacy of olanzapine monotherapy in acute bipolar

depression: a pooled analysis of controlled studies. J. Affect. Disord. 149, 196–201

34 McKeage, K. (2014) Aripiprazole: a review of its use in the treatment of manic

episodes in adolescents with bipolar I disorder. CNS Drugs 28, 171–183

35 Canuso, C.M. et al. (2009) Paliperidone extended-release for schizophrenia: effects

on symptoms and functioning in acutely ill patients with negative symptoms.

Schizophrenia Res. 113, 56–64

36 Ma, K. et al. (2012) Scyllo-inositol, preclinical, and clinical data for alzheimer’s

disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 64, 177–212

37 Swica, Y. et al. (2013) Acceptability of home use of mifepristone for medical

abortion. Contraception 88, 122–127

38 Watson, S. et al. (2012) A randomized trial to examine the effect of mifepristone on

neuropsychological performance and mood in patients with bipolar depression.

Biol. Psychiatry 72, 943–949

39 Berwaerts, J. et al. (2012) A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled

study of paliperidone extended-release as maintenance treatment in patients

with bipolar I disorder after an acute manic or mixed episode. J. Affect. Disord. 138,

247–258

40 Citrome, L. et al. (2014) Clinical assessment of lurasidone benefit and risk

in the treatment of bipolar I depression using number needed to treat,

number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. J. Affect. Disord.

155, 20–27

emerging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

Drug Discovery Today � Volume 00, Number 00 � July 2014 REVIEWS

DRUDIS 1467 1–9

41 Besga, A. et al. (2012) Discovering Alzheimer’s disease and bipolar disorder white

matter effects building computer aided diagnostic systems on brain diffusion tensor

imaging features. Neurosci. Lett. 520, 71–76

42 Angst, J. et al. (2014) DSM-IV diagnosis in depressed primary care patients with

previous psychiatric ICD-10 bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 152–154, 295–298

Please cite this article in press as: Garay, R.P. et al. Bipolar disorder: recent clinical trials and e(2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.07.010

43 Parker, G. et al. (2013) Differentiation of bipolar I and II disorders by examining for

differences in severity of manic/hypomanic symptoms and the presence or absence

of psychosis during that phase. J. Affect. Disord. 150, 941–947

44 Azorin, J.M. et al. (2010) Possible new ways in the pharmacological treatment of

bipolar disorder and comorbid alcoholism. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 6, 37–46

merging therapies for depressive episodes and maintenance treatment, Drug Discov Today

www.drugdiscoverytoday.com 9

Reviews�POSTSCREEN

![[CONFERENCE PAPER] Bipolar Bozuklukta BDT](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/63328d1f4e0143040300b9b3/conference-paper-bipolar-bozuklukta-bdt.jpg)