'Between the Devil of the Desert and the Deep Blue Sea': re-orienting Kuwait, c.1900-1940

-

Upload

callibreil -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of 'Between the Devil of the Desert and the Deep Blue Sea': re-orienting Kuwait, c.1900-1940

lable at ScienceDirect

Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e65

Contents lists avai

Journal of Historical Geography

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate/ jhg

‘Between the devil of the desert and the deep blue sea’: re-orientingKuwait, c.1900e1940

Robert S.G. Fletcher*

Department of History, University of Warwick, UK

Abstract

This article examines the place of two environmental regimes e the desert and the sea e in the history of Kuwait before oil. Historians have longapproached Kuwait through its maritime past, foregrounding its connections around the Persian Gulf and across the Indian Ocean. This article shifts theemphasis, arguing that in the early twentieth century Kuwait faced westwards across the desert as much as it did across the sea. It takes this possibility asan opportunity to revisit a set of assumptions about the shape of the pre-oil Kuwaiti economy, the structure of its politics, and the nature of its positionwithin a wider British Empire. In all three, the interwar years in particular witnessed a loosening of Kuwait’s maritime bonds and a turn to the desert: anorientation which helped the state survive the difficult years preceding the coming of oil revenues.

In part, this act of re-orientation seeks to advance our knowledge of Kuwait before oil, a period and place still neglected by many commentators andscholars. But it also forms part of a wider concern to treat ’empty’ desert and steppe ’spaces’ as arenas of activity in their own right, capable of exertingsignificant influence on the polities around them. More broadly, then, Kuwait provides an excellent place to test the power and reach of desert dynamics,and to explore the interplay between maritime and desert influences in global history.� 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Maritime history; Deserts; Kuwait; Bedouin; British Empire; Arabian Peninsula; Persian Gulf

Kuwait today is a petrostate. Oil dominates economic life and un-derpins its ‘superwelfarism’. Its revenues have helped sustain theprominence of Kuwait’s ruling family and have reconfigured thefabric of society: rarely has the popular image of a country been soclosely tied to a single commodity.1 But those interested in thecountry’s pre-oil past soon find themselves wading in very differentwaters. Here, the sea predominates. Its images are everywhere: inthe dhows depicted on coins and bank notes and on the emblem ofthe state; in popular memoirs of shipping and pearling; in thereplica ships stationed outside the country’s museums (the first ofwhich, the great trading boum Al-Mohalab, was placed beforeKuwait’s first high school ‘to be a historic reminder for the students

* c/o Department of History, University of Warwick, Humanities Building, University RE-mail address: [email protected]

1 S. Khalaf and H. Hammoud, The emergence of the oil welfare state: the case of Kuwasee M. Herb, The Wages of Oil: Parliaments and Economic Development in Kuwait and the

2 K. Bourisley, Shipmasters of Kuwait: A Glorious Era Before the Oil Discovery, Kuwait, 23 This is the core theme of Yacoub Yusuf Al-Hijji’s influential Kuwait and the Sea: A Brie

the new museum.4 S. Khalaf, The nationalization of culture: Kuwait’s invention of a pearl-diving heritage

Arab Gulf States, London, 2008, 40e70; S. Khalaf, Globalization and heritage revival in th(2002) 13e41; N. Fuccaro, Histories of City and State in the Persian Gulf: Manama since 1

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2015.04.0200305-7488/� 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

about the Golden Pearl and Seafaring Era of their fathers andgrandfathers’).2 In 2010, a lavishly renovated Kuwait MaritimeMuseum re-opened its doors to the public in Salmiyah. Comparedwith the nearby Kuwait National Museum e gutted and torchedduring the Iraqi occupation, and with renovation work still un-derway e it tells a far more compelling national story. Kuwaitbefore oil was oriented towards the sea and its activities. Kuwaitis,the museum shouts, form ‘a maritime nation’.3

As anthropologists and historians of the Persian Gulf haveshown, this boom in maritime heritage forms part of the repertoireof power of the region’s national governments.4 Replicawaterfrontsand ‘Seaman’s Villages’ have proliferated since the 1990s, building

oad, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK.

it, Dialectical Anthropology 12 (1987) 343e357. For a fascinating comparative study,UAE, Ithaca, NY, 2014.009, 398e399.f Social and Economic History, London, 2010. Al-Hijji acted as a leading consultant on

, in: A. Alsharekh and R. Springborg (Eds), Popular Culture and Political Identity in thee Gulf: an anthropological look at Dubai Heritage Village, Journal of Social Affairs 19800, Cambridge, 2009, 2e3.

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6552

e in the case of Kuwait e on the ‘living cultural museums’ andinvented traditions of the annual Pearl Diving Festival and nationalSeaman’s Day (Youm al-Bahhar) celebrations.5 But scholars haveplayed their own part in advancing notions of Kuwait’s specialrelationship with the sea. Encouraged by the current revival ofocean histories, the country is regularly portrayed as a node in theIndian Ocean world, and rightly so: repositioning these waters as‘connective spaces or “continents”’ has recovered all manner of Gulfstories ill-served by efforts to nationalize and Arabize the past.6

In recent years a newwave of historians has set about rethinkingthe history of the Gulf’s port cities, exploring them as sites ofintersection around amaritime and littoral world that straddled theterritorial divisions e and Arab and Iranian ‘worlds’ e of today.Reidar Vissar, Nelida Fuccaro, Hala Fattah and many others besideshave shown how Basra, Manama and other Gulf ports and markettowns formed part of the wider regional networks of Indian Oceantrade.7 Urban historians have revealed how Kuwait’s maritimeeconomy ‘shaped the internal dynamics and structures of urban lifebefore oil’, while historians of empire also describe the country interms of its place along the maritime approaches to British India.8

This work has offered many insights, not least the rewards oflooking beyond narrowly national histories to unearth the denseweb of interconnections that have existed between the peoples ofthe Persian Gulf. Its achievements are reflected in the work ofColumbia University’s ‘Gulf/2000’ project, and its striking map of‘The Persian Gulf Cultural World’, in which ports and coasts appearbetter linked with one another than they are with their terrestrialhinterlands [Fig. 1].

Yet if the sea forms the backdrop to our newly connected his-tories of Kuwait and the Gulf, the desert has received far lessattention. Reconstructions of crossings and exchange have pre-dominantly been written with the sea in mind. Some who havecelebrated Kuwait’s pearl divers and nakhodhas (ship captains)have dismissed its desert population for having had ‘only a slenderpositive impact on the life of Kuwait’.9 Few serious historians wouldrepeat that accusation: as Frank Broeze put it almost twenty yearsago, ‘however much [Kuwaitis’] economic activity was determinedby the maritime face of their city, the desert remained a strongforce’.10 But that force has seldom been the dedicated focus of ourenquiry. Many have alluded to the significance of the deserteconomy and its political consequences, but often in the course of

5 Khalaf, Nationalization of culture (note 4).6 Fuccaro, Manama since 1800 (note 4), 24e25. See, for example, S. Bose, A Hundred Ho

Bhacker, The cultural unity of the Gulf and the Indian Ocean: a longue durée historical pethe maritime turn in historical studies, see K. Wigen, Oceans of history: introduction, A

7 R. Vissar, Basra, the Failed Gulf State: Separatism and Nationalism in Southern Iraq, MüTrade in Iraq, Arabia and the Gulf, 1745e1900, Albany, NY, 1997.

8 F. Al-Nakib, Inside a Gulf port: the dynamics of urban life in pre-oil Kuwait, in: L.G.2014, 199; R.J. Blyth, The Empire of the Raj: India, Eastern Africa and the Middle East, 1858eand the British in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf, Oxford, 2007.

9 S.M. Al-Shamlan, Pearling in the Arabian Gulf: A Kuwaiti Memoir, London, 2001, 59.10 F. Broeze, Kuwait before oil: the dynamics and morphology of an Arab port city, in: F1997, 178e179.11 Hala Fattah’s reconstruction of the Arabian horse trade is an accomplished exceptioShammar tribal confederations in particular. But it ends with the decline of that particula159e183. Yacoub Yusuf Al-Hijji’s Kuwait and the Sea contains an interesting and suggerequiring further examination, but more remains to be done to demonstrate its significanthe shoreline. Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 124e129.12 Al-Shamlan, Pearling (note 9), 59; Khalaf, Nationalization of culture (note 4).13 Bourisley, Shipmasters (note 2), 14, 25. For a similar argument, see Al-Hijji, Kuwait aopenness, Farah Al-Nakib also notes that ‘the cultural cohesion of the townspeople is so(note 8), 209.14 Al-Shamlan, Pearling (note 9), 59.15 A.N. Longva, Nationalism in pre-modern guise: the discourse on hadhar and badu inRevisiting hadar and badu in Kuwait: citizenship, housing and the construction of a dic16 Longva, Nationalism (note 15), 172, 179.

pursuing other questions.11 The net effect of the transnational turnhas been to create an imbalance between maritime-based studiesof the Gulf’s interconnectedness e detailed, textured, sensitive tochange over time e and those concerned more with terrestrialcrossings. And at a popular level, while Bedouin life was celebratedin a Desert Day (Youm al-Badiya) in 1986, the sea remains ‘the basicelement in the formation of Kuwait’, looming largest in the state’spromotions of national identity.12 Working the sea, so the storygoes, laid the foundations for Kuwait’s prosperity, stability, opengovernment and work ethic e values Kuwaitis are urged to recalltoday.13 The desert, in contrast, becomes for some an unproductive,empty and politically unimportant ‘waste’: best remembered as thesource of ‘raids and troubles’ that have ‘afflicted’ the nation, andwhich this ‘people of the sea’ have fought to overcome.14

All this is of more than merely academic interest. Claims tohaving contributed to Kuwait’s past e the stuff of historical mem-ory and belonging e form an active part of how groups competeover access to resources in the modern oil state. In everyday lan-guage in Kuwait today, the term hadhar (which connotes a sense ofbeing a ‘true’ Kuwaiti) is reserved for the descendants of Kuwait’sdivers, sailors, traders and fishermen: the pre-oil, maritime com-munity who had lived within the walls of Kuwait town. Bedu, incontrast, conveys a sense of otherness; it is used to mark out thedescendants of former nomadic pastoralists who had come toKuwait and secured nationality only after the export of oil.15 As AnhNga Longva and Farah Al-Nakib have shown, this discursive habit offraming hadhar and bedu as mutually exclusive identities is notmerely at odds with the historical record. It is actively on the rise,finding expression in the growth of ‘bedu ethnopolitics’, rising in-terest in purity of origin (asl), accusations of bedu disloyalty duringIraq’s 1990 invasion, and ongoing disputes over state housingpolicy.16

Visions of Kuwait’s maritime orientation, therefore, have muchcurrency in contemporary discourse. But howwell do they stand upas guides to the past? This article re-examines Kuwait’s earlytwentieth century with this question in mind. It considers the casethat in the final few decades before the coming of oil (firstcommercially exported in 1946), Kuwait faced westwards acrossthe desert as much as it did across the sea. It takes this possibility asan opportunity to revisit a set of assumptions about Kuwait’s po-litical and economic orientation in the not-so-distant past: about

rizons: The Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empire, Cambridge, MA, 2006; M. Redharspective, in: L.G. Potter (Ed), The Persian Gulf in History, London, 2009, 163e171. Formerican Historical Review 111 (2006) 717e721.nster, 2005; Fuccaro, Manama since 1800 (note 4); H. Fattah, The Politics of Regional

Potter (Ed), The Persian Gulf in Modern Times: People, Ports and History, Basingstoke,1947, London, 2003; J. Onley, The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers

. Broeze (Ed), Gateways of Asia: Port Cities of Asia in the 13the20th Centuries, London,

n, detailing the mechanisms and networks of a trade conducted by the ‘Anaza andr trade at the turn of the twentieth century: Fattah, Politics of Regional Trade (note 7),stive chapter on ‘The Desert Trade’ with Kuwait, and points to a number of areasce in Kuwait before oil, and to break historians’ habit of viewing desert events from

nd the Sea (note 3), 134. Exploring the pre-oil town’s reputation for tolerance andmetimes attributed to their experiences on board ship’: Al-Nakib, Inside a Gulf port

Kuwait, International Journal of Middle East Studies 38 (2006) 171e187; F. Al-Nakib,hotomy, International Journal of Middle East Studies 46 (2014) 5e30.

Fig. 1. ‘The Persian Gulf Cultural World’. Source: The Gulf/2000 project, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, New York, http://gulf2000.columbia.edu/maps.shtml.

R.S.G.Fletcher

/Journal

ofHistoricalG

eography50

(2015)51

e65

53

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6554

the shape of its economy before oil, the structure of its politics, andthe nature of its place within the British Empire.

In doing so, this article contributes to an emerging literaturewhich revisits the histories of port cities in Asia e Frank Broeze’s‘brides of the sea’ e recognizing the importance of their relation-ships with their rural hinterlands as well as their maritime fore-lands.17 As Broeze himself wrote in response to his critics, it wasnever his intention, in focusing on port cities ‘or “maritime influ-ence” in general’, to treat them ‘in splendid isolation’, or to forestallthe examination of other forces.18 And yet the collective emphasisand manifest achievements of the agenda Broeze helped advanceleaves us wanting something of a corrective nonetheless. It is stillworth our while to recall that the history of the Gulf’s port cities‘cannot be understood without their hinterlands’.19 Kuwait’s desertconnectivities are acknowledged more often than they are exam-ined; we still lack a sense of the integral contribution they havemade to the economic survival and political endurance of the pre-oil polity.

To achieve this e to help restore Kuwait’s desert horizons toview e this article focuses on the country’s interwar experience. Inthe 1920s and 30s a peculiar series of events e from the collapse ofpearling and the creation of new international boundaries, to therise of a new power in the desert, the future king of Saudi Arabia,Abd Al-Aziz Ibn Saud e combined to demonstrate the salience ofdesert dynamics. But while these dynamics were certainlyexaggerated in this period, they were not wholly unique to it. Theattention they garnered in the interwar years offers an invaluablechance to explore how desert and sea interacted up close, awindow onto forces and trends which historians have, in lesstroubled times, struggled to register fully.

In many respects, the networks of power, labour and commercethat flowed across Kuwaiti horizons e arid and maritime e wereinterdependent. Each year, as Barclay Raunkiaer observed first-hand on the eve of the First World War, thousands of Bedouinwere drawn to the town to try their hand in the great pearl dive.20

As we shall see, in straightened circumstances, the shaykhs ofKuwait re-allocated their time and resources between the demandsand actors of its maritime and desert arenas. Such intersections ofthe desert and the sea warrant further research, and are partly mysubject here. But if I also present the desert and the sea ascompetitive elements in what follows, it is only to offset our pre-sent habits of talking up Kuwait’s maritime connectedness withoutaffording its desert hinterland equal attention.

This article, then, forms a contribution to our knowledge ofKuwait before oil, a period still ‘understudied and undervalued’ bymany commentators and scholars.21 In the process, we shall also

17 A key theme of Nelida Fuccaro’s work on the history of Bahrain, in particular: Fuccacities in the Gulf, in: Potter, Persian Gulf in Modern Times (note 8), 29.18 F. Broeze, Brides of the Sea revisited, in: Broeze, Gateways of Asia (note 10), 1e16.19 Fuccaro, Manama since 1800 (note 4), 11. As Hala Fattah reminds us, the importanagricultural regions and the ports of Iraq and the Gulf can be neglected by those ‘who preIndia and Britain from 1864 onwards.’: Fattah, Politics of Regional Trade (note 7), 10.20 B. Raunkiaer, Through Wahhabiland on Camelback, London, 1969, 40.21 J.P. Cooper, Review of Kuwait and the Sea by Y. Al-Hijji, Journal of Arabian Studies 1 (22 Raunkiaer, Through Wahhabiland on Camelback (note 20), 51.23 Yacoub Al-Hijji notes that e pearling aside e Western scholarship has tended to vAl-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), xvi. Abu-Hakima noted a similar imbalance in studieThe Rise and Development of Bahrain, Kuwait and Wahhabi Saudi Arabia, London, 1988, 124 Abu-Hakima, Eastern Arabia (note 23), 165e166; Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 325 S.G. Knox, Trade report for Koweit for the year 1907e1908, 4 May 1908, British Librtrade of Kuwait for the year 1915e1916, 16 Aug. 1916, IOR, R/15/5/73.26 J.C. More, Report on the Trade of Kuwait for the year 1920e1921, 22 Feb. 1922, IOR,27 S.G. Knox, Trade report for Koweit for the year 1908e1909, 20 Apr. 1909, IOR, R/15/28 Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), xv.

see imperial understandings of the environment in Kuwait e afixation with the coast and a blindness to the desert e changing inresponse to interwar experiences. But it also forms part of a widerconcern to reconsider ‘vacant’ desert and steppe environments asforgotten arenas of activity, impacting on the polities aroundthem. This is a perspective that, for all its insights, the very successof the ‘new thalassology’ can obscure. For Kuwait’s experience alsoraises wider questions for the maritime turn in historical studies.When we talk, for example, of sea histories, or of ocean basins andregions, how far inland are these maritime influences and net-works supposed to have predominated? And what happenedwhen maritime and land-based systems intersected? In this,interwar Kuwait provides an excellent place to test the power andreach of desert dynamics, and to explore the interplay betweenmaritime history and desert influences. As we shall see, histori-cizing the ocean has had much to offer, but not at the expense ofneglecting a desert arena that was sometimes competitive,sometimes complementary.

‘A place of clay between steppe and sea’: the maritime heydayof Kuwait before oil22

When contemporaries described Kuwait between the wars, theycommonly gave it a dual aspect: a vibrant maritime sector to theeast, and the overland caravan trade to the west. Of the two, themaritime dimension is much the best documented.23 Kuwaitexemplified the commercial, religious and cultural networks thathad bound Gulf states into the Indian Ocean world for centuries.By the early twentieth century its nakhodhas dominated the Gulfcoastal trade. The profitable business of re-exporting dates fromBasra underpinned a far-flung maritime trading system, involvingcoffee from Yemen, horses from Arabia and rice, wheat and speciefrom India.24 From the water’s edge, successive British politicalagents at Kuwait attempted to quantify all this commerce inannual Trade Reports (gathering valuable material for future his-torians), but they also accepted that the sheer volume of trafficmade even their higher estimates inadequate.25 Timber from Indiaand East Africa fuelled a growing shipbuilding industry. Fishing e

‘the only truly local produce’ e employed hundreds more.26 Eventhe town’s fresh water supply was imported by sea: by 1909, sometwenty dhows were regularly shuttling up the Shatt al-Arab forthis purpose alone.27 Little wonder, then, that historians write sofulsomely of ‘the time-honoured bonds forged by Kuwaitis withthe sea’.28

Above all, Kuwait’s maritime orientation appeared confirmed bythe pre-eminence of pearling. The pearl industry, dependent on

ro, Manama since 1800 (note 4). See also N. Fuccaro, Rethinking the history of port

ce and survival of a range of trade relationships between interior market towns,fer to continue dwelling on the phenomenal rise of the region’s seaborne exports to

2011) 121.

iew all Gulf economic history before oil as ‘unworthy of description and analysis’:s of the eighteenth century: A.M. Abu-Hakima, History of Eastern Arabia, 1750e1800:68.), 58.ary, India Office Records [hereafter IOR], R/15/5/72; R.E.A. Hamilton, Report on the

R/15/5/74.5/72.

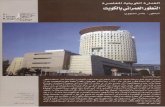

Fig. 2. Kuwait from the air, 1920s. Source: MECA, Dickson collection, album 2.

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e65 55

Bombay, accounted for about one third of the town’s annual in-come.29 From June to September the demand for pearl diverscleared Kuwait town of able-bodied men, and built relationships ofprofit sharing and debt that bound society together.30 Hundreds ofvessels worked the pearl banks in the early twentieth century; in1912, a bumper year, between seventy and eighty new pearlingboats were added to the fleet in a single season.31 Even after theboats returned, the sea e through fishing, shipbuilding and mari-time trade e still formed the basis of Kuwait’s economic strength.By 1920, Kuwait town itself extended about two miles along theshore, but only half a mile into the interior, as if clinging to the coastand recoiling from ’the waste country’, as one British handbookdubbed the desert [Fig. 2].32

29 Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 42.30 Knox, Trade report for 1907e1908 (note 25); Bourisley, Shipmasters (note 2), 117.31 G.W. Prothero (Ed), A Handbook of Arabia, London, 1920, 286; W.H.I. Shakespear, RepKuwait, 1912 became remembered as a ‘golden period’ (sanat al-tafha) or ‘zenith’ of the32 Prothero, Handbook (note 31), 295. For an analysis of the power of Kuwait’s harbour oKuwait before oil (note 10).33 Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 27.34 Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 9, 54.

In many ways, Kuwait’s politics also flowed from its maritimeorientation. The Sabah of Kuwait, a leading family since the 1750sand emphatically its rulers since the energetic administration ofMubarak Al-Sabah (1896e1915), closely regulated the pearlingseason, setting official opening and closing dates, and taking a shareof the profits from each boat.33 The Sabah promoted the interests ofKuwait’s mariners in the Gulf and its merchant houses in India,often corresponding with other governments and the British ontheir behalf, and worked to make the town a port of call for theBritish India Steam Navigation Company.34 The leading ship-owners and pearl merchants were, for their part, fully aware oftheir political and economic consequence. In 1910, for example,they issued a sharp reminder to the shaykh of how thoroughly

ort on the trade of Kuwait for the year 1911e1912, 18 May 1912, IOR, R/15/5/72. Inpearling business: Bourisley, Shipmasters (note 2), 76.ver the town’s spatial morphology, see Al-Nakib, Inside a Gulf port (note 8); Broeze,

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6556

‘their staying away would damage him and his town’.35 Well intothe interwar period, the shaykh remained mindful of their wealthand influence.36 It is this which fuels a persistent ‘merchant’s myth’today, by which members of the National Assembly talk up theirforebears’ role in tempering the shaykh’s power, while others pointto Kuwait’s maritime heritage inmaking it more liberal minded andpolitically inclusive than its Arab neighbours.37

The desert economy, in contrast, was always harder to pin down.British political agents, answerable to the Government of India,intuited that Kuwait’s desert trade might be significant e ‘Kuwait,after excluding those interested in the Pearl Trade, is nothing but acommunity of successful smugglers’. But this was never a priority,and they accepted that such records as they possessed werescarcely up to the task of enumeration; the tallies of imports andexports in their Trade Reports focus solely on commerce by sea.38

The Government of India’s records describe little beyond theshoreline; only glimpses of the desert economy emerge.39 Periodsof security around Kuwait, for example, triggered a noticeable in-crease in sales to Bedouin of tea, sugar, coffee and tobacco.40 Desertcaravans from Najd would, in normal years, purchase ‘large quan-tities’ of rice, while good rains and pasture would see an increasedtrade in ghee, hides andwool.41 In Safat Square, Bedouin exchangeda range of pastoral products (camels, sheep, horses, wool and ghee)for foodstuffs, piece-goods, arms and ammunitione partly for theirown consumption, but also for resale to the Qasim towns and acrossthe North Arabian and Syrian Deserts.42 This left some Britons witha vague feeling that ‘the population of Kuwait is largely Bedouin:their outlook is towards the desert’.43 But as late as the 1930s, of-ficials observed that there was no equivalent to the system of shipmanifests for caravans trading with Kuwait town, and that manytransactions were undertaken by ‘individual Bedouins’, ‘impossible’to count or control.44 In lieu of the statistics kept on shipping,pearling and shipbuilding, the case for the centrality of a desert-facing economy has tended to go by default.

The British Government also primarily viewed Kuwait throughthe concerns ofmaritime trade and security: thesewere thewesternapproaches to the Raj, and the Government of India’s turf. Indeed, as

35 Political Agent, Kuwait to Political Agent, Bahrain, 12 Sept. 1910, IOR, R/15/5/18. As Hthe Gulf region worked to curb rulers’ political power and forestall commercial restrictioTrade (note 7), 25e28; Fuccaro, Pearl towns and early oil cities: migration and integratiRiedler (Eds), Migration and the Making of Urban Modernity in the Ottoman Empire and B36 The best guide to the political activism of Kuwait’s merchants between the wars remCambridge, 1990, especially chapter 3. For a reading of the 1938 reform movement as onMiddle East Studies 28 (1992) 66e100.37 Crystal, Oil and Politics (note 36), 58; Bourisley, Shipmasters (note 2), 14, 233, 334, 338 S.G. Knox to V. Cavendish, 20 June 1923, IOR, R/15/5/53.39 Fuccaro, Rethinking the history of port cities in the Gulf (note 17), 32e33.40 S.G. Knox, Trade report for Koweit, 1905e1906, 12 Apr. 1906, IOR, R/15/5/72.41 Knox, Trade report for 1907e1908 (note 25); W.H.I. Shakespear, Trade report for Ku42 Raunkiaer, Through Wahhabiland on Camelback (note 20), 48e49; M.K. Al-Jassar, ConsKuwait courtyard and Diwaniyya (University of Wisconsin thesis), 2009, 117e119; H.R.P. DPS/12/3743. See also: Al-Nakib, Inside a Gulf port (note 8), 214.43 Political Resident, Bushire to Foreign Secretary, Government of India, 13 Feb. 1930, I44 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 31 Jan. 1934, IOR, R/15/1/531.45 Fuccaro, Manama since 1800 (note 4), 53, 59e60.46 For a useful survey, see R. Schofield, Britain and Kuwait’s Borders, 1902e1923, in: B47 W.H.I. Shakespear to A. Hirtzel, 26 June 1914, IOR, R/15/5/27.48 S.G. Knox to V. Cavendish, 20 July 1923, IOR, R/15/5/53.49 G.N. Curzon, Address Delivered by His Excellency Lord Curzon, Viceroy and Governor-Geon the 21st November 1903, London, 1906.50 Schofield, Britain and Kuwait’s Borders (note 46), 86e87. See also: F. Al-Nakib, The losStudies 2 (2012) 25.51 As Joseph Kostiner notes, J. Kostiner, Britain and the northern frontier of the Saudi staYork, 1988, 31.52 R.J. Blyth, Aden, British India and the development of steam power in the Red Sea, 1Imperial Maritime Trade in the Nineteenth Century, Woodbridge, 2004; H.L. Hoskins, The53 W.H.I. Shakespear, Note on tour along the pearl banks to Bahrain, 2 Sept. 1910, IOR,

Nelida Fuccaro has shown, Delhi’s readiness to arbitrate disputesover access to the pearl banks (and even, in some cases, to begin theprocess of delimiting territorial waters) favoured the very growth ofthe Gulf’s port settlements.45 By the FirstWorldWar the British hadentered into anumberof local agreements todefend Indian shippingand deny the shoreline to imperial rivals.46 Even after the secretagreement of 1899, in which the British undertook to protectKuwait’s ruler in exchange for control of its foreign affairs, Britishpolicy towards Kuwait remained limited and littoral. British in-terests in Arabia ‘are confined to the coast-line’, wrote the politicalagent at Kuwait on the eve ofwar; tribal conflict could be stomachedin the interior, so long as it did not affect life in the port.47 After all,only at sea did Britain possess the requisite advantages in knowl-edge and resources to project power effectively. When later facedwith the rise of Ibn Saud, one initial response was to considergranting him a seaport: only then would he be sufficiently ‘vulner-able’ for Britain ‘to exercise some influence’ over him.48

This maritime perspective e and maritime imperial rhetoric e

coursed through British descriptions of the Gulf. ‘We opened theseseas to the ships of all nations’, Lord Curzon declaimed, ‘and enabledtheirflags tofly inpeace’.49 But beyond the shore, and out of range ofits naval guns, British views of Kuwait’s desert hinterland weremarkedly less bombastic. Its politics seemed internecine and itstopography was largely unknown; this was a black hole into whichthey might be sucked. Officials were endlessly warned againstbecoming entangled in desert affairs, just as they feared Kuwait it-selfmight be swallowed by its forces. An Anglo-Ottoman agreementof 1913 e never ratified e actively sought to ‘absolve’ the British ofresponsibility for defence beyond the town.50 Therewere momentsof closer engagement: the despatch of talented liaison officers toBedouin groups during the First World War marked a particularhigh-point.51 But in general, British familiarity with the interior’sroutes to theMediterranean hadwaned following the acquisition ofAden (1839) and the opening of the Suez Canal (1869).52 In 1901,1907 and again in 1910, British officials took a dim view of MubarakAl-Sabah’s ‘adventurism’ in the desert, descrying the ‘burden ofuseless expenditure’ which his campaigns incurred.53 Thereafter,

ala Fattah and Nelida Fuccaro have shown, merchants’ readiness to relocate aroundns, and is a recurrent feature of the region’s history: Fattah, The Politics of Regionalon in the Arab coast of the Persian Gulf, in: U. Freitag, M. Furhmann, N. Lafi and F.eyond, London, 2010, 101.ains J. Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar,e led by a ‘business oligarchy’, see K.O. Salih, The 1938 Legislative Council in Kuwait,

49. See also Fuccaro, Manama since 1800 (note 4), 4.

wait for the year 1909e1910, 1 May 1910, IOR, R/15/5/72.tancy and change in contemporary Kuwait City: the socio-cultural dimensions of theickson, Report on the trade of Kuwait for the year 1934e1935, 23 Dec. 1935, IOR, L/

OR, R/15/1/332.

.J. Slot (Ed), Kuwait: The Growth of a Historic Identity, London, 2003, 58e94.

neral of India, to the Trucial Chiefs of the Arab Coast at a Public Durbar held at Shargah

t ‘two-thirds’: Kuwait’s territorial decline between 1913 and 1922, Journal of Arabian

te, 1922e1925, in: U. Dann (Ed), The Great Powers in the Middle East, 1919e1939, New

825e1839, in: D. Killingray, M. Lincoln and N. Rigby (Eds), Maritime Empires: Britishoverland route to India in the eighteenth century, History 9 (1924) 302e318.R/15/5/18.

Fig. 3. C.J. Edmonds, ‘The Bedouin Market at Kuwait’ [n.d. c. March, 1934]. Source: MECA, Edmonds collection, album B7.

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e65 57

they remained haunted by the prospect of the shaykh becoming soembroiled indesert politics as toput both their interests andhis ownposition at risk.

It followed that British reports on the Persian Gulf defaulted todescribing its coast and towns as all-important, and the desert as a‘waste’. Kuwait town ‘presents a singular instance of commercialprosperity’, one lieutenant reported in 1845, in a surroundingcountry of ‘salt and sandy desert, of the most barren and inhospi-table description’. It was ‘an excellent harbor. without, however,any other advantage’.54 In descriptions of the town, the Britishalighted on its perimeter wall as a shorthand for their geographicalimagination: it seemed to seal off a thriving maritime communityfromadrainon its energies andwealth. Thefirstwallwas built in the1760s, but a later construction, in 1920,was thefirst tobe fortified. Inreality, it was intended to defend against a specific threat from IbnSaud, rather than to ward off the Bedouin in general. Even then itpreserved a wide and unenclosed space for Bedouin use within itslimits (thereby facilitating encounters with desert communities)[Fig. 3].55 But to the British, and to some Kuwaitis today, the wallbecame a symbol of the antipathy of the desert and the sea,markingthe limit of the shaykh’s legitimate ambition, the edge of imperialinfluence, and the bounds of the community.56

Indeed, by the 1920s and 1930s, expansionist voices amongKuwait’s Saudi and Iraqi neighbours would also be insisting e for

54 A.B. Kemball, Memoranda on the resources, localities, and relations of the tribes inIntelligence: Selections from the Records of the Bombay Government, NS, No. 24, 1856, Cam55 Al-Nakib, Revisiting (note 15), 8e10; Al-Jassar, Constancy and change (note 42), 11756 For example: Bourisley, Shipmasters (note 2), 241e254. Kuwait’s 1959 law of nationaindigenous Kuwaiti nationality. As a result, the wall has remained an evocative symbol i1950s: Longva, Nationalism (note 15), 176. For further discussion of the wall and the ‘hi57 George Ogilvie-Forbes (Charge d’Affaires, Baghdad) to Tawfiq Beg al Suwaidi (MinistDeputy Political Resident, Bushire, Telegram No. 305-K, 17 Sept 1920, IOR, L/PS/10/925.58 More, Trade report for 1920e1921 (note 26); H.R.P. Dickson, Report on the trade of59 H.R.P. Dickson, Report on the trade of Kuwait for the year 1932e1933, 15 Jan. 1934,Dickson collection, Box 3, File 8; Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 139.60 Dickson, Trade report for 1929e1930 (note 58).

their own reasons e that ‘there was no such thing as Kuwaiti ter-ritory outside the town of Kuwait’.57 And yet, in the era of the twoworld wars, a series of events combined both to shake Kuwait’smaritime orientation, and to remind the British, the Sabah andKuwait’s neighbours alike of the significance of its desert connec-tions. In the run-up to the coming of oil, the claim that Kuwait wasdisconnected from its desert hinterland would be loudly asserted,but it was harder than ever to sustain.

Crisis and opportunity on Kuwait’s horizons

Historians generally agree that the interwar period in Kuwait was atime of profound crisis. Both its maritime and desert trades un-derwent a dramatic decline, until the impact of oil revenues in the1950s eclipsed them altogether. At sea, the pearling indus-tryecentral to the life of so many Gulf economiese steadily lost outto Japanese cultured pearls. In 1921 only 320 of Kuwait’s 700pearling boats set out for the banks; by 1931, many had not been tosea for years.58 The Great Depression worsened matters: priceshalved as demand for pearls from Bombay, Paris, London and theUnited States all but collapsed.59 Kuwaiti merchants with ‘safes fullof pearls’ were unable to pay their pearling crews: in 1930, ShaykhAhmad Al-Sabah (1921e1950) was forced to compel them to sellother assets to provide temporary relief.60 By 1932 merchants had

habiting the Arabian shores of the Persian Gulf, in: R.H. Thomas (Ed), Arabian Gulfbridge, 1985, 109.e119.lity established 1920 e the year the wall was constructed e as the cut-off date forn contemporary discussions of identity and belonging, despite its demolition in theerarchy of spaces’ in the modern city, see Al-Nakib, Revisiting (note 15).er of Foreign Affairs, Iraq), 24 July 1934, IOR, R/15/5/129; Political Agent, Bahrain to

Kuwait for the year 1929e1930, 9 Apr. 1931, IOR, L/PS/12/3743.St. Antony’s College, Oxford, Middle East Centre Archive [hereafter MECA], Harold

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6558

faced four consecutive years of unsold pearls, representing a vaststore of locked up capital that was steadily depreciating in value.61

Even those historians most committed to demonstrating theenduring links between the Middle East and the Indian Oceanaccept that ‘the onset of the Great Depression sundered these Indo-Gulf trading ties on both sides of the ocean’.62 By 1939, only ahundred pearling boats remained active.63

The sea was receding from view in other ways too. The precip-itous decline of the pearl trade led to a contraction in ship- andboat-building, a once ‘busy and thriving’ industry.64 A special sur-vey of the state of British shipping in the Gulf complained of‘serious inroads’ being made into British and Indian lines in thedecade after 1906.65 As for Kuwait’s own merchant mariners, longdistance trading (al-safar) would outlast the decline of pearling, butwas certainly less profitable during the Depression, and the all-important trade in dates from southern Iraq fell sharply in themid 1920s.66 Over the same period, the number of dhows involvedin the shorter-distance Gulf carrying trade also declined, fromaround 50 in 1904 to 30 in the 1930s.67

By land, events would seem to tell an equally bleak story, asKuwait’s hinterland was buffeted by the rise of a powerful anddisruptive desert actor. Abd Al-Aziz Ibn Saud had captured Riyadhin 1902 and the eastern coastal province of Al-Hasa by 1912.Leaning on the dynamism of the Ikhwan, semi-settled Arab tribes ofWahhabi faith, he would launch out from his base of power in Najd,defeating his rivals, the Rashid, at Ha’il in 1922, pushing northwardtowards the new British mandates of Trans-Jordan and Iraq, andwestwards into the Hejaz in 1924e25. In the midst of this expan-sion, in 1921, Ibn Saud forbade Bedouin caravans from his growingdomain from trading with Kuwait. He was soon posting frontierguards to enforce his orders, and instructing the Amir of Al-Hasa tosearch Bedouin parties for merchandise. It was not until 1937 thatnormal trade with Kuwait resumed, although a formal agreementhad to wait until 1942.68

The reasons for imposing this long ‘blockade’ were complex,forming part of a targeted bid by Ibn Saud to curb the autonomy ofBedouin groups (the Mutair, above all), to increase his hand infuture negotiations over oil, to redirect desert trade towards hisown coastal ports at Uqair, Qatif and Jubail, andemany allegede to‘reduce Koweit to a position of dependence’.69 The upshot, how-ever, is widely regarded as having been a ‘disaster’ for Kuwait, with

61 Dickson, Trade report for 1932e1933 (note 59).62 Bose, Hundred Horizons (note 6), 84.63 A. Villiers, Sons of Sindbad: an account of sailing with the Arabs in their dhows, in thePersian Gulf; and the life of the shipmasters and the mariners of Kuwait, New York, 1969,64 Shakespear, Trade report for 1909e1910 (note 41); E. Epstein, Kuwait, Journal of theSecond World War would trigger a small revival: Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 165 G. Lloyd, Summary of notes on economic situation in Gulf and Mesopotamian mark66 Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 74e75, 88.67 Al-Hijji, Kuwait and the Sea (note 3), 96.68 T. Hickinbotham to C. Prior, Telegram 560, 4 June 1942, IOR, R/15/5/115. Even then,69 A. Ryan, Ibn Saud’s attitude towards Kowait, 16 Aug. 1933, IOR, R/15/5/110. ‘Bin SRedirecting Kuwait’s trade to Uqair and Qatif ‘will mean the Customs at those placesCommissioner, Baghdad, 6 Apr. 1920, IOR, R/15/5/25.70 H. Winstone and Z. Freeth, Kuwait: Prospect and Reality, London, 1992, 90.71 J.C. More, Report on the trade of Kuwait for the year 1925e1926, 17 Feb. 1927, IOR,[hereafter TNA], CO 732/46/8. For modern calculations of these and other losses to Kustruggles over Kuwait’s frontiers, 1921e1943, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 3272 For example, Epstein, Kuwait (note 64), 602.73 J.B. Glubb, Annual report on the administration of the Southern Desert of Iraq, 1 Ma74 For the wider context of Britain’s heightened interwar engagement with desert affaiImperialism and ‘The Tribal Question’: Desert Administration and Nomadic Societies in the75 Special Service Office (Basra), report for 31 July to 4 Aug. 1926, TNA, AIR 23/273.76 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 14 Sept 1933, IOR, R 15/1/531.77 H.R.P. Dickson, Kuwait and her Neighbours, London, 1956, 280; Glubb, Report on the

recorded sales of tea and sugar e staple commodities in the deserttrade e falling away across the 1920s.70 By 1926 Najdi merchantswho had long been resident in Kuwait town were already packingtheir bags; four years later, Shaykh Ahmad Al-Sabah would claimthat the blockade was costing him Rs 4,000,000 a year in customsrevenue alone.71 More generally, the blockade has been seen asemblematic of the wider fate of nomads and pastoral economies ina newly partitioned Middle East, as Bedouin groups were containedby artificial political borders, forbidden from raiding and collectingkhuwwa, and displaced by the advent of mechanized transport.72

For one British officer, the blockade ‘severed’ one of the ‘twogreat arteries’ through which Kuwait’s lifeblood flowed e the otherbeing the pearl trade.73 Yet there is plenty of evidence to suggestthat desert patterns were not so easily strangled. Kuwait did notmerely act as a clearing-house for trade across the North Arabianand Syrian Deserts. The grazing resources of its hinterland alsoattracted tribes from across the region, from the Mutair, Ajman andAwazim of northern and eastern Arabia, to the Dhafir, Muntafiq andDahamshah of southern and western Iraq. Because of the implica-tions for their new aerial and overland communications routes, andfor colonial control in their new mandated territories, British offi-cials from Egypt to Iraq were paying growing attention to thesemigratory movements. Their reports to the Colonial Office, ForeignOffice and Air Ministry e alternate centres of calculation from theGovernment of India records onwhich Gulf historians have so oftenrelied e point to widespread evasion and negotiation of Ibn Saud’sattempt to seal off Kuwait’s desert frontiers.74

In 1926, for example, the British Special Service Officer at Basrafound that Ibn Saud’s own Ikhwan tribes were circumventing theblockade by trading through Iraqi Shammarwho grazed their flocksin Kuwait.75 ‘Underground sources’ confirmed that smuggling intoNajd increased again when Ibn Saud was forced to direct hisattention towards Yemen and the Asir.76 Further evidence suggestswidespread collusion between merchants and nomads on bothsides of the border. In 1928, at the start of a three-year rebellionagainst Ibn Saud’s control, Ikhwan leaders approached the shaykh ofKuwait requesting permission to trade in exchange for immunityfrom attack. The political agent, Harold Dickson, denied that theshaykh had evermade such a deal; officials in southern Iraq, notablyJohn Glubb, were adamant that he had.77 Either way, it is clear thatsmuggling went on throughout the rebellion, amidst a general

Red Sea, round the coasts of Arabia, and to Zanzibar and Tanganyika; pearling in thexx.Royal Central Asian Society 25 (1938) 601. A demand for transport ships during the6e17.ets, Arab Bulletin 19 (1916) 217e226.

the new rules were markedly more restrictive.aud is badly in want of money’, the British political agent at Bahrain explained.will be doubled or even trebled in a short time’: Political Agent, Bahrain to Civil

R/15/5/77; H.R.P. Dickson to H.V. Biscoe, 18 Mar. 1930, The National Archives, Kewwait, see A.B. Toth, Tribes and tribulations: Bedouin losses in the Saudi and Iraqi(2005) 150.

y 1929 e 16 May 1930, TNA, CO 730/168/8.rs, and for its new experiment in ‘desert administration’, see: R.S.G. Fletcher, BritishMiddle East, 1919e1936, Oxford, 2015.

administration of the Southern Desert (note 73).

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e65 59

‘breakdown’ of Ibn Saud’s blockade arrangements.78 Before October1928 theMutair and other ‘rebel’ tribes continued to trade in Kuwait‘quite openly’.79 A year later Dickson reported their camels grazingin Kuwait at Jahra each evening, and a large increase in the numberof Bedouin trading inKuwait townonbehalf of Ikhwan camps acrossthe border.80 Members of the Ajmanwere particularly successful indrawing on kinship networks to this end, while the prominentmerchant Hilal Al-Mutairi e himself of Bedouin origin, his storyproof that commercial success could buy social status in the portcity e was also suspected of being ‘a chief supplier’ to the rebels.81

By the mid-1930s local British officials perceived more clearlythat ‘the peculiarly difficult nature of the frontier’meant Ibn Saud’sblockade, despite its ‘drastic methods’, had ‘not been successful’.82

It wasn’t simply that forms of nomadic migration (amidst whichsmuggling was masked) proved remarkably versatile, or thatKuwait’s land frontiers were contested, undefended and 260 mileslong. The new political landscape also worked to make this ‘a mosttempting desert frontier’ for mobile populations and their metis.83

Its frontiers were open and offered good winter grazing. Policeposts and patrols were as yet few and far between, yet partitionhad created an attractive assortment of unequal customs regimes.With no formal system of manifests for caravans, there was little tostop merchants or individual Bedouin leaving Kuwait ‘with theintention’ of trading with Iraq, only to smuggle contraband intoSaudi territory instead.84 Even Ibn Saud did not always enforce theblockade as severely as his rhetoric would imply. As Anthony Tothhas shown, he received numerous petitions from Bedouin groupsto make exceptions and be allowed to enter Kuwait, and hefrequently relented in the interests of maintaining a claim to theirallegiance.85 At the end of the Ikhwan rebellion, ‘thousands’ ofBedouin poured into Kuwait to replenish their supplies.86

This was not the first time that tough circumstances had pushedKuwait towards desert smuggling. During the First World Warmany seized the opportunity to run contraband across the Arabianand Syrian Deserts, against a backdrop of bad rainfall, a poor pearlmarket and the dislocation of Gulf trade.87 Across the nineteenthcentury, Kuwait had profited from its status as ‘a very significanthole’ in the Ottoman customs regime. Indeed, the British hadexploited it themselves before the war, relying on the movements

78 Political Agent, Kuwait to T.C. Fowle, Contraband questions with Iraq, 21 Feb. 1934,79 Dickson, Kuwait (note 77), 297.80 Dickson to Political Resident, Bushire, 25 Nov. 1929, IOR, R/15/5/34; Political Agent,81 H.R.P. Dickson, Administrative report of the Kuwait Political Agency for the year 1929Bushire, 29 July 1929, IOR, R/15/5/31. See also, Broeze, Kuwait before oil (note 10), 160.82 A. Clark-Kerr to J. Simon, 11 Apr. 1935, IOR, R/15/5/130.83 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, Note on the contraband problem of Iraq with her neigh84 G. de Gaury to Ibn Sobah, 3 Oct. 1936, IOR, R/15/5/113.85 During a period of drought in the spring of 1931, for example, the ‘Utayba were allo‘dying the death of a thousand cuts’: A.B. Toth, The transformation of a pastoral econom2000, 278e280.86 Dickson, Trade report for 1929e1930 (note 58).87 Civil Commissioner, Baghdad, to Political Agent, Kuwait, Telegram No. 4641, 29 May 1trade of Kuwait for the year 1914e1915, 10 Aug. 1915, IOR, R/15/5/73. Despite hurried attgrowing importance in overland smuggling until the summer of 1918: H.S.B. Philby to P88 F. Anscombe, The Ottoman role in the Gulf, in: Potter (Ed), Persian Gulf in Modern T89 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 14 Sept. 1933, IOR, R/15/1/531.90 Yasin Pasha al-Hashimi to F. Humphreys, 11 July 1933, IOR, R/15/1/531. For the Iraqi91 F. Humphreys to G.W. Rendel, 11 Jan. 1933, IOR, R/15/1/531.92 Yasin Pasha to Humphreys, 11 July 1933 (note 90); Dickson to Fowle, 7 Mar. 1933, R93 F. Humphreys to J. Simon, 16 Dec. 1934, IOR, R/15/1/533; F. Humphreys to J. Simon,94 Dickson to Fowle, Contraband problem (note 83).95 Dickson to Fowle, Contraband problem (note 83).96 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 21 Dec. 1933, IOR, R/15/1/531.97 F. Humphreys to J. Simon, 6 Mar. 1935, IOR, R/15/1/533; F. Humphreys to J. Simon, 198 For example, Anon., Note on the activities of Sheikh Subah [n.d.], IOR, R/15/5/218; WBritish Embassy, Baghdad, 27 Dec. 1950, TNA, FO 371/91343.

of the Shammar, the Dhafir and the Ajman to run arms to theMuntafiq rebels.88

The record of the interwar years suggests a similar pattern. IbnSaud’s sustained efforts to prevent overland trade, Dicksonconcluded, had been ‘without real success’: such was the impor-tance to Kuwait of Bedouin trade that ‘she [is] bound to encourage’it ‘by every means in her power’.89 And as its pearling industrycontracted once again, so its desert economye illicit or otherwiseecould be said to have grown in importance.

To see this we need look no further than to Kuwait’s othercontested interwar borderland: that with the British mandate andHashemite Kingdom of Iraq. On achieving independence in 1932,Iraq promptly raised its customs tariffs to boost state revenues andprotect a nascent manufacturing industry.90 Faced with this neweconomic opportunity, smuggling from Kuwait quickly assumed‘rather serious proportions’ e though its extent was fiercelydisputed.91 Iraqi officials complained of an illicit trade worth£30,000 to £60,000 a year; Harold Dickson thought this a deliberateexaggeration to pressure Kuwait, via the British, to raise its ownduties.92 But it remains the case that following a series of promi-nent incidents involving smuggling by sea and up the Shatt al-Arab,smuggling increasingly concentrated on overland routes.93 Theregular presence of 15,000 Muntafiq and Hammar Lake tribesmenwintering in Kuwait, for example, offered a seasonal screen forrunning contraband up to the Euphrates. Their migration har-boured experienced smugglers ‘who easily pass locally for Iraqishepherds’, while each family ‘load[ed] up asmuch contraband as itpossibly can’ on its return to Iraq each spring.94

The Dhafir, the Shammar and the Beni Huchaim were similarlyinvolved, grazing herds southward into Kuwait each spring andmaking purchases in town.95 Merchants from Basra were alsoaccused of stockpiling sugar in Kuwait and arranging for Iraqi boatsand desert tribes ‘to take it away in driblets’.96 Sugar, tea, coffee,tobacco, matches and cigarette paper were all flowing across Iraq’sborders in the 1930s, and while some Kuwaiti imports were ulti-mately destined for Persia and Najd, Iraq offered ‘the easier andwider target and a greater prospect of success’.97 Indeed, evidenceof overland smuggling, and even of Al-Sabah involvement, wouldcontinue to surface throughout the 1940s.98

IOR, R 15/1/531.

Kuwait to Ibn Sobah, 6 Nov. 1929, IOR, R/15/5/34., [n.d.], MECA, Dickson collection, Box 3, File 6; Harold Dickson to Political Resident,

bours, 30 May 1933, IOR, R 15/1/531.

wed to graze in Kuwait and conduct so much trade that the blockade seemed to bey: Bedouin and states in Northern Arabia, 1850e1950 (Oxford Univ. D. Phil. thesis),

918, IOR, R/15/5/101. For Kuwait’s wartime ‘misfortunes’, see W. Grey, Report on theempts to impose a blockade of their own, the British were unable to check Kuwait’s. Loch, 20 Apr. 1918, IOR, R/15/5/101.imes (note 8), 267; Dickson to Fowle, Contraband problem (note 83).

Customs Tariff Law of 1933, see TNA, FO 624/1.

/15/1/531.IOR, 19 Feb. 1935, IOR, R/15/1/533.

6 Dec. 1934, IOR, R/15/5/130.. Hay to British Embassy, Baghdad, 1 May 1948, IOR, R/15/5/218; J.C.B. Richmond to

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6560

Many of Iraq’s claims were undoubtedly oversold. There was apowerful rhetorical dividend to be reaped by branding Kuwait as anest of smugglers: Shaykh Ahmad and Harold Dickson both saw init a ‘carefully laid plan to bring Kuwait to her knees and force herinto the Iraq fold’.99 But desert smuggling certainly was a seriousbusiness between thewars, into which the Sabah themselves wereincreasingly drawn. Shaykh Ahmad refused to countenanceexternal interference in Kuwait’s customs service, and made onlylimited attempts to tighten supervision.100 In frustration, Iraqiofficials accused the shaykh of profiting handsomely from thetrade, but that charge missed the point: there was far more atstake. For Ahmad, Iraq’s new tariffs were a boost to Kuwait’s tradeprospects in otherwise difficult times. Were he to attempt to shutit down he risked losing ‘the good-will of his subjects’ and being‘regarded as a traitor’ by other members of the Sabah family.101

Ahmad insisted he was ‘just as free to encourage his people’strade’ as Iraq was herself. What was smuggling from an Iraqiperspective was to the shaykh ‘all good trade’, and in such matters‘every state had the right to do the best it could for its ownnationals’.102

By the late 1930s, overland smuggling had become a vital propto the Kuwaiti economy, especially significant e as Britain’sambassador to Iraq observede ‘in light of the declining profits to behad from diving for pearls’.103 To a degree, it helped offset pearling’scollapse: few now doubted that Kuwait’s prosperity ‘is to someextent bound up’with smuggling.104 As such, this interwar episodebrings into focus how possibilities and energies could shift betweenKuwait’s maritime and desert sectors; it is a good reminder that thesteppe and the sea cannot be approached in mutually exclusiveterms.105 Before thewar, as we have seen, at least a third of Kuwait’spearling crews (and perhaps as many as half) were made up ofBedouin signing on for a season.106 This was a fluid pool of labourdrawn from beyond the town walls, but also one quite prepared toleave the dive when better opportunities arose. During the FirstWorld War, for example, the demand for labourers in Mesopotamiadrew in ‘numbers of poor class Arabs who were ordinarily engagedin pearling’; in 1918 only a third of Kuwait’s pearling boats couldput to sea for want of manpower.107 A similar shift in energiesbetween the desert and the sea occurred again between the wars.Many Ajman, Mutair and Awazim participated in the dive in goodyears, but nonetheless maintained their pastoral herds, relying onrelatives to graze them at Jahra and across Kuwait’s borders. Theseconnections not only made smuggling viable: amidst the crisis of

99 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 14 Sept. 1933, IOR, R/15/1/531. Some Iraqi demands e este clawed at the edges of Kuwaiti sovereignty, while the Baghdad press was yet more brazdirect intervention: T.C. Fowle, Note on Iraqi-Kuwaiti smuggling, encl. in: Laithwaite to WSyed Hamid Beg al Naqib, 26 Apr. 1935, TNA, FO 624/3, file 169/6/35.100 Humphreys to Simon, 16 Dec. 1934 (note 97).101 A. Clark-Kerr to J. Simon, 11 Apr. 1935, IOR, R/15/1/533; Syed Hamid Beg al Naqib, 2102 Note giving the views of his Excellency the Shaikh on the smuggling questions with103 Humphreys to Simon, 16 Dec. 1934 (note 97).104 Humphreys to Simon, 16 Dec. 1934 (note 97).105 Similarly, Hala Fattah has shown how ‘the active rerouting of trade’ between key maof the Arabia-Gulf-Iraq trading region, facilitating the interconnection of land and sea r106 W.H.I. Shakespear, Report on the trade of Koweit for the year 1912e1913, 16 June 1107 Hamilton, Trade report for 1915e1916 (note 25); D.V. MacCollum, Report on the tra108 H.R.P. Dickson to Political Resident, Bushire, 17 June 1929, IOR, R/15/5/31. The pusordinarily have dived had been reduced to near starvation.109 See H.R.P. Dickson, Administrative report of the Kuwait Political Agency for the yea110 Clark-Kerr to Simon, 11 Apr. 1935 (note 101).111 Translation of a letter dated 28th May 1935 from His Excellency Sheikh Sir Ahmad aencl. in T.C. Fowle to H.A.F. Metcalfe, 24 May 1935, IOR, R/15/1/533.112 Broeze, Kuwait before oil (note 10), 166.113 Most famously, following Mohammad al-Rashid’s capture of Ha’il in 1887, Mubarakbroker in the desert in his own right: J.G. Lorimer, Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, ’Oman, an114 Crystal, Oil and Politics (note 36), 20; Abu-Hakima, Eastern Arabia (note 23), 173, 179

the pearl trade, and in the tough times of the Depression, theireconomic consequence actually grew.108

In the 1920s and 30s, then, as one aspect of Kuwait’s economiclife reached a low ebb, another appears to have swelled to a flood.Harold Dickson believed that ‘Kuwait’s very existence depends onthe Pearl market, so long as the land blockade continues’.109 Butwhile the collapse of pearling was very real, the blockade soonproved porous, and the opportunities for overland smugglingincreasingly attractive. ‘At present’, wrote Britain’s ambassador toIraq, ‘the whole economy of [the Shaykh of Kuwait’s] domain rests,for a variety of reasons, almost entirely on the illicit activities of hispeople’.110 Even Ahmad Al-Sabah would claim that his state‘entirely depends on trade with the interior’: the pearl dive,apparently, already forgotten.111

Desert politics

We often consider Kuwait before oil to have operated as a kind ofmerchant coalition. At the centre of its politics lay ‘a delicate bal-ance between the inclinations and requirements of the amirs, onthe one hand, and those of themerchants, on the other’.112 Al-Sabahauthority was formed through negotiation with that of themercantile elite, and centred on promoting, supervising and taxingthe pearl trade, the Gulf carrying trade and long-distance oceanicexchange. Between the wars, however, the political consequence ofdesert affairs surged to the fore, and its prominence demands thatwe historians recognize e as contemporaries had to at the time e

the inclusion of another seat at the table. In the 1920s and 30s inparticular, Kuwait’s politics would be oriented as much towards itsdesert hinterland as it was to markets beyond the shore.

This is not to discount the long record of Kuwaiti shaykhscourting Bedouin tribes, nor the definite readiness of Mubarak Al-Sabah to intervene in pre-war Arabian politics.113 Kuwait’s over-land trade had always rested on maintaining ties of kinship, con-tract and obligation with Bedouin groups in the interior, and sincethe eighteenth century the Sabah family had been particularlyclosely involved in the desert (as opposed to the sea) trade.114 But itremains the case that these long-standing connections acquired anew urgency between the wars. There is still a tendency in some ofthe scholarly literature to see this involvement in desert politics asan aberration, and in conflict with the state’s legitimate andmaritime concerns. ‘Instead of being satisfied with playing the roleof primus inter pares of an oligarchic maritime republic’, wrote

ablishing a joint Iraqi-Kuwait preventive service, or forcing Kuwait’s duties into lineen in claiming that desert smuggling and clashes with Iraqi patrols gave grounds forarner, 31 July 1934, IOR, R/15/1/532; Express Letter No. C-118, Visit of His Excellency

6 Apr. 1935, TNA, FO 624/3.Iraq, 30 Jan. 1934, encl. in: Dickson to Fowle, 31 Jan 1934, IOR, R/15/1/531 (note 44).

rket towns in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries formed ‘one of the strategies’outes: Fattah, Politics of Regional Trade (note 7), 9.913, IOR, R/15/5/73.de of Koweit for the year 1917e1918, 3 Apr. 1919, IOR, R/15/5/74.h factors were certainly there: Dickson recorded that some Bedouin who would

r 1930, MECA, Dickson collection, Box 3, File 6.

l Jabir as Sabah, Ruler of Kuwait, to the Political Resident in the Persian Gulf [n.d.],

had offered refuge to a young Abd-Al Aziz Ibn Saud, becoming a significant powerd Central Arabia, Calcutta, 1908e1915, 1156; Prothero, Handbook (note 31), 289e290..

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e65 61

Frank Broeze of Mubarak Al-Sabah (1896e1915), ‘[he] began toview himself as a dynastic ruler whose destiny lay in Kuwait’sArabian hinterland rather than in the fostering of the port city’smaritime economy’.115 In contrast, the dramatic rise of Abd Al-AzizIbn Saud e a disruptive force in desert politics e can be seen asupsetting an established Al-Sabah preference for pursuing a bal-ance of power in Arabia. The question of how to respond wouldincreasingly preoccupy the rulers of Kuwait.116

Across the 1920s, Ibn Saud called on the Wahhabi Ikhwan tribesto project his power outwards from its base in Najd. An Ikhwan raidinto Kuwait in October 1920, for example, came close to over-whelming the town, and was only seen off with heavy losses andBritish military support. Two years later, a great swathe of Kuwaititerritory was signed away e under British pressure e in an attemptto assuage Ibn Saud’s ambitions. Meanwhile, the allegiance of theAwazim and Ajman tribes, whose migrations covered that fluidborderland between Saudi and Kuwaiti influence, had becomeanother ‘burning question’ between Shaykh Salem of Kuwait(1917e21) and his aggrandizing neighbour.117 By the later 1920s,the prospect of the very collapse of Saudi power had becomeequally disconcerting. When in 1927 Ibn Saud attempted to rein inthe Ikhwan, those tribes most accustomed to viewing Kuwait astheir preferred source of provisions e the Ajman, Harb and Mutaire began a three-year revolt along the limits of Saudi authority.

Behind the ebb and flow of these particular desert campaigns, apicture emerges of Kuwait’s hinterland e as a rich source of wintergrazing and a point of resupply e becoming a vital location in awider political arena, buffeted by events around the North Arabianand Syrian Deserts. It witnessed regular incidents of trans-borderraiding, the development of frontier patrol schemes, and aheightened competition for tribal allies. From March 1929 toFebruary 1930, it played a pivotal role in the endgame of the Ikh-wan Revolt against Saudi control. Thereafter, the blockade, smug-gling disputes with Iraq and ongoing frontier violations continuedto draw Shaykh Ahmad into desert affairs, as did his own attemptsto court Bedouin groups that had previously acknowledged Saudiauthority.118

It followed that between the wars the ruling Sabah family ofKuwait increasingly looked to desert communities e and indeed toa growing infrastructure of British desert control e for informationand support. As politics itself began to turn on desert affairs, so the‘merchant coalition’ that formed Kuwait’s political field waswidened to include other actors. Again, the Sabah had leaned on

115 Broeze, Kuwait before oil (note 10), 167e168.116 Glubb, Report on the Administration of the Southern Desert (note 73).117 Anon., The Ajman Question, Arab Bulletin 107 (1918) 362e363.118 The Rashaida under Ibn Musaillim, for example, went over to the Ikhwan to save theIntelligence Summary, No. 10 [n.d. 1934], IOR, L/PS/12/2082.119 Anon., Situation at Kuwait, Arab Bulletin 88 (1918) 147.120 Political Agent, Kuwait, to H.R.P. Dickson, 9 Sept. 1918, IOR, R/15/5/102; D.H. Finnie,121 Crystal, Oil and Politics (note 36), 49; Schofield, Britain and Kuwait’s borders (note 4122 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, Shaikh’s visit to Baghdad, 9 Sept. 1932, IOR, R/15/1/505123 G. de Gaury to T.C. Fowle, Ambassador and Smuggling, 26 Apr. 1936, IOR, R/15/1/5341936, but had grounds to suspect many more. The Iraqi government responded with a lista statement made on 12th Safar 1353 [26 May 1934] by Mutlaq bin Abdulla al Dahamreproduces some of these Bedouin testimonials in Tribes and tribulations, 162e165.124 Translation of a letter No. R/5/43, dated the 1st Safar 1355 (22nd April 1936) from125 G. de Gaury to Baghdad, Telegram 995, Koweit-Iraqi incidents, 18 Oct. 1937, TNA,December 1944, IOR, R/15/5/218.126 H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 18 Aug. 1936, IOR, R/15/1/535.127 H.R.P. Dickson, extract from Kuwait Intelligence Summary No. 15, Sept. 1935, IOR, R128 Political Resident, Bahrain to British Embassy, Baghdad, 1 May 1948, IOR, R/15/5/218218.

Bedouin groups for support in the past, but their doing so becameparticularly visible in the interwar years. Jaber Al-Sabah (1915e17),for example, had ‘let desert politics slide’, but his successor Salem(1917e21) knew ‘how important it was. to maintain a hold over[the Bedouin]’ and ‘set about repairing the damage’, dispatchingyoungermembers of the Sabah family ‘to beat up the Hinterland’.119

By 1918 the Ajman affair e that ongoing dispute between ShaykhSalem and Ibn Saud as to the right to claim this Bedouin group’sobedience e and the protection of overland trade were already ‘theonly real questions in Kuwait’; the British troops who came to thedefence of the town in 1920 did so following unprecedented de-mands to shore up Kuwait’s desert forces.120 Salem’s successor andnephew, Ahmad, invested great time and energy in seeking outBedouin groups to monitor and check Ikhwan activity; in 1938 hewould also call on his Bedouin allies to shut down a merchant-ledassembly critical of his rule.121 Ahmad even extracted an under-taking from the British to attempt to resolve the Saudi blockade e

though it was never delivered upon to his satisfaction.122

Moreover, tensions were rising on Kuwait’s northern frontiereven as they began to ease in thewest. By themid 1930s Iraqi policecar patrols were routinely entering Kuwait e so deep, in fact, thatGerald De Gaury felt Iraq’s de facto frontier was now halfway intoKuwaiti territory e harassing nomads and traders, seizing propertyand attacking suspected smugglers.123 Those Bedouin who campedsouth of Safwan, where a section of the Iraqi desert police werequartered, were particularly exposed.124 British investigationsrevealed ‘a regular plan of armed infiltration’ by Iraqi desert police‘to catch smugglers before they reach [the] frontier’; for the police,confiscating contraband and extorting smugglers became an eco-nomic opportunity in itself.125 Faced with all this, Shaykh Ahmadwould not only resist Iraqi demands to raise his tariffs, or accept anIraqi Zollverein, or submit to greater interference in internal affairs.He would actively invoke Kuwait’s political relationship with GreatBritain in the hope of resolving disputes on behalf of his desertpopulation.126 Indeed, the popularity Shaykh Ahmad derived fromresisting Iraqi threats and incursions offered a vital source of do-mestic support in deeply troubled times.127 As late as the 1940s, heproved reluctant to investigate those charged with overlandsmuggling, especially if they had rendered him some form of po-litical assistance in the past.128

Together, the rise of Ibn Saud, the new importance of overlandtrade and the growing friction along the land frontier with Iraqworked to place events on Kuwait’s desert periphery at the heart of

ir herds in 1927, only to be wooed back by the shaykh in 1934: Extract from Kuwait

Shifting Lines in the Sand: Kuwait’s Elusive Frontier with Iraq, London, 1992, 46.6), 74... De Gaury counted eleven serious frontier violations between April 1933 and Aprilof complaints of its own. For an example of alleged Iraqi brutality, see Translation ofi, encl. in H.R.P. Dickson to T.C. Fowle, 29 May 1934, IOR, R/151/532. Anthony Toth

his Excellency the Ruler of Kuwait to the Political Agent, Kuwait, IOR, R/15/1/534.FO 624/9; Political Agent, Kuwait to Political Resident, Bushire, Telegram 957, 29

/15/1/534.; Political Resident, Bahrain to British Embassy, Baghdad, 12 June 1948, IOR, R/15/2/

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6562

its interwar politics.129 Sympathetic political agents like HaroldDickson and Gerald De Gaury acknowledged as much, drawing adirect link between the shaykh’s tolerance of desert smuggling, hisinfluence among the Bedouin and his wider personal reputation.130

Despite strong pressure from Baghdad and the Foreign Office inparticular, these local British officials were loath to act againstsmuggling, or to do anything to undermine the shaykh’s authorityin the desert. Any move by the shaykh ‘to control what the Bedouinbought or took out’ would surely be ‘a deadly blow to his pres-tige’.131 And if word got out that a crackdown had come about as aresult of British pressure, then her reputation around the Gulfwould doubtless suffer too.132

Empire turned around: British imperialism and the pull of thedesert

The growing political consequence of desert affairs in Kuwait pointsto a final topic for reconsideration: the impact of desert dynamicson Britain’s imperial arrangements.

Throughout the nineteenth century, British officials had beendeeply reluctant to intervene in the affairs of the Arabian interior.‘Physical inaccessibility and economic importance’, J.G. Lorimeronce wrote, kept Arabia ‘almost beyond the purview of the Britishand Indian Governments’.133 It was the Government of India,accustomed to viewing Kuwait as part of its patch, which was mostinsistent on this point. It consistently warned that nothing shouldbe done in the interior to undermine the impression of Kuwaitiindependence, for nothing would be more certain to provokegreater Saudi or Iraqi encroachment. But the interwar years wouldwitness a growing struggle between Delhi and Whitehall for thecontrol of Gulf policy e a struggle which the strain of coordinatingthe First World War had helped to rekindle.134 Amidst the devel-oping crisis of the Ikhwan Revolt, the Government of India’s rep-resentatives continued to deprecate calls from the Colonial Officeand the Royal Air Force establishment in Iraq to station British orIraqi forces in Kuwait’s desert hinterland.135 Yet this positionwouldbe transformed by the force of events on the ground, and theway inwhich this happened reveals the reverberations of a wider desertarena upon the workings of the interwar British Empire.

Between the wars, as local British officials in Egypt, Palestine,Trans-Jordan and Iraq sought to develop new overland communi-cations routes, theywere gradually drawn into closer arrangementswith the region’s nomadic populations.136 In Kuwait, too, manyfactors conspired to pull the British deeper into desert affairs e andall before the rise of the oil producing industry. The escalatingdispute over the allegiance of the Ajman, for example, forced the

129 Anon., Situation at Kuwait (note 119), 149.130 Anon., Note of an informal conversation between Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon Loch, Aand Dr. Naji Beg al Asil (Director General of Foreign Affairs, Iraq Government), with Ma131 Dickson to Fowle, Contraband problem (note 83).132 T.C. Fowle to Secretary of State for India, 26 Feb. 1935, IOR, R/15/1/533.133 Lorimer, Gazetteer (note 113), 1157. The Ottoman empire, too, concentrated its effor134 Blyth, Empire of the Raj (note 8), 132e169.135 For example, G.W. Rendel, Foreign Office minute, 18 Feb. 1929, TNA, FO 371/13714,136 R.S.G. Fletcher, Running the corridor: nomadic societies and imperial rule in the int137 Anon., Ajman Question (note 117).138 H. Dobbs to L. Amery, 29 Mar. 1928, TNA, AIR 23/38.139 Dickson, Administrative report for the year 1929 (note 81). As Frederick Anscombe hled historians to exaggerate Britain’s role in determining the development of Gulf polOttoman role (note 88), 273.140 H.R.P. Dickson, Administrative report of the Kuwait Political Agency for the year 193141 For some of the proposed measures, see ‘Record of a meeting held at the Foreign OfApr. 1935, IOR, R/15/1/533.142 The Shaykh of Kuwait made growing use of fidawis (bodyguards) to help maintain auwars: Salih, The 1938 Legislative Council (note 36), 69.

British to supervise their relocation to southern Iraq.137 The seri-ousness of Ikhwan raiding along the borders of Britain’s mandatoryterritories fed talk of a common Desert Defence scheme ‘stretchingright across the Iraq Trans-Jordan “corridor” from Kuwait to theSyrian boundary’.138 Newmotor roads and imperial air routes werealso being developed through Kuwait’s desert hinterland, but thegrowth of British knowledge of and influence in the desert was justas much in response to events originating there and instigated byArab actors.139 Far from shunning the desert ‘waste’, the politicalagent at Kuwait began undertaking extended desert tours ‘to showhimself to the tribes, and to familiarize himself with the hinterland,the various wells, caravan routes, grazing areas, and the lines ofannual migrations of the Kuwait and neighbouring bordertribes’.140 British Trade Reports began to carry revised maps of ‘TheCountry Round Kuwait’, slowly paying more attention to thephysical and human geography that made up the Kuwaiti hinter-land [Fig. 4]. By the end of our period, as smuggling and policeincursions across the Kuwaiti-Iraqi frontier became the centre ofdispute, British advisors and investigators had become entangledthere too.141

While historians often stress the fragmentation that attendedthe creation of the region’s new international boundaries, theseBritish practices of ‘desert administration’ developed a momentumof their own. To monitor migration, pursue raiders and smugglers,and arbitrate tribal disputes, disparate officials came to collaborateand connect with one another, so that they e like the Bedouinthemselves e operated across formal boundaries. By the timeIkhwan raiding threatened the security of Kuwait town, it was theseBritish officers who were well placed to provide the relevantexpertise and personnel.142

Consequently, the growing British activity in the hinterland ofKuwait was not so much the product of bilateral relations betweenmetropole and periphery. Nor did it progressively advance inlandfrom an established, coastal enclave. It occurred instead through akind of administrative creep, as structures and powers basedaround this desert system e from the RAF’s regional network ofSpecial Service Officers, to the armed cars and camel patrols ofsouthern Iraq e were drawn across borders by the movements ofthe Bedouin themselves. And as the jurisdiction of desert forcesanswering to the Colonial Office and Air Ministry seemed toadvance onto its turf, the Government of India protested, and astruggle for authority ensued.

These tensions flared across the interwar years, but the ex-changes surrounding the climax of the Ikhwan Revolt are partic-ularly instructive. In February 1928, Iraqi officials began to proposeusing Kuwaiti territory as a forward base to intercept Ikhwan raids

cting Political Resident in the Persian Gulf and Tahsin Beg ‘Ali (Mutasarrif of Basrah)jor R.P. Watts (Political Agent, Kuwait) present, [n.d. Sep. 1934], IOR, R/15/5/129.

ts on coastal control in the Gulf: Anscombe, Ottoman role (note 88), 263.

E/842/3/91.er-war Syrian Desert, Past and Present 220 (2013) 185e215.

as noted, a failure to properly acknowledge the political skill of Arabian shaykhs hasitics, economy and society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: Anscombe,

1, MECA, Dickson collection, Box 3, File 6.fice on the 5th February [1935]’, encl. in India Office to Political Resident, Bushire, 5

thority on the frontiers, but had ‘no permanent desert control system’ between the

Fig. 4. ‘The Country Round Kuwait’. Source: J.C. More, Report on the trade of Kuwait for the year 1925e26, 17 Feb. 1927, IOR, R/15/5/77.

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e65 63

from Najd. The Gulf Resident, Government of India and the IndiaOffice all resisted the move, lest visibly connecting Kuwait withIraq prove the first step along the road to its wholescale absorp-tion.143 But advocates of this forward movement tried to explainthat the connection had long been formed by the desert tribesthemselves. The rich grazing of Kuwait’s hinterland, they argued,

143 For example, Political Resident, Bushire to High Commissioner, Baghdad, 11 Feb. 192144 R. Jope-Slade, Special Service Officer (Basra) report, 31 Jan. 1929, TNA, AIR 23/47; J.B145 High Commissioner, Baghdad to Secretary of State for Colonies, Telegram No. 98, 2Baghdad, 25 Sept. 1928, TNA, AIR 23/43.

formed ‘a corridor for the passage of raiding parties to the Iraqifrontier’, and one that ‘almost neutralizes all our effort andexpenditure on defence against the Akhwan’.144 Soon enough,British aircraft from Iraq were indeed being sent to Kuwait tobetter monitor the Ikhwan.145 Even after their withdrawal, theKuwait political agent noted with alarm the petrol dump left

8, TNA, AIR 23/35.. Glubb to K. Cornwallis, 21 Jan. 1929, TNA, AIR 23/47.0 Feb. 1928, IOR, R/15/5/29; Secretary of State for Colonies to High Commissioner,

R.S.G. Fletcher / Journal of Historical Geography 50 (2015) 51e6564

behind in the country ‘as if it were a part of Iraq’ e a move hedoubted to be ‘politically sound’.146

By the end of 1928, desert police forces operating in the Britishmandate for Iraq were demanding the right to patrol in Kuwait todefend Iraqi pastoralists drawn to its grazing grounds.147 TheAdministrative Inspector of Iraq’s Southern Desert, John Glubb,noted how Kuwaiti enthusiasm for this rose and fell with the for-tunes of Ibn Saud’s campaign. When Ibn Saud’s control seemed togrow, the people of Jahra ‘were dropping hints about the desire-ability of an Iraq police post in Jahra’; when the rebels struck back,the Shaykh of Kuwait was ‘imperiously demanding that Iraq tribesand police be forbidden to enter his territory’.148 Yet after a group ofIraqi shepherds were attacked before the very walls of Kuwait towne and seemingly afforded no assistance by Kuwaiti forces nearby e

the demands of Iraqi police to patrol inside Kuwait became harderto refuse.149 Kuwait, long viewed as ‘the only chink in the armour’along Iraq’s frontiers, was gradually being drawn into a widerdefensive scheme.150 In March 1929 Iraqi desert police began su-pervising migrations in Kuwaiti territory, though they were or-dered to keep a low profile, and their movements restricted whenShaykh Ahmad protested to the Gulf Residency.151 Nonetheless,officials in Iraq like Glubb continued to send unauthorized patrolsinto Kuwait, and confessed to treating Kuwaiti tribes ‘on [an] equalfooting with those of Iraq’.152