Beginnings: The International Photographic Collection at the National Gallery of Victoria (May 2015)

Transcript of Beginnings: The International Photographic Collection at the National Gallery of Victoria (May 2015)

Beginnings: The International Photographic Collection at the National Gallery of Victoria

Dr Marcus Bunyan

This is a story that has never been told. It is the story

of how the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne,

Australia set up one of the very first photography

departments in a museum in the world in 1967, and

employed one of the first dedicated curators of

photography, only then to fail to purchase classical

black and white masterpieces by international artists

that were being exhibited in Melbourne and sold at

incredibly low prices during the 1970s and early 1980s,

before prices started going through the roof.

The NGV had a golden chance to have one of the greatest

collections of classical photography in the world if only

they had grasped the significance and opportunity

presented to them but as we shall see - due to personal,

political and financial reasons - they dropped the ball.

By the time they realised, prices were already beyond

their reach.

Justifications for the failure include lack of financial

support, the purchasing of non-vintage prints and

especially the dilemma of distance, which is often quoted

as the main hindrance to purchasing. But as I show in

this research essay these masterpieces were already in

1

Australia being shown and sold in commercial photography

galleries in Melbourne at around $150, for example, for a

Paul Strand photograph. As a partial public institution

the NGV needs to take a hard look at this history to

understand what went wrong and how they missed amassing

one of the best collections of classical photography in

the world.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

May 2015

AbstractThis research paper investigates the formation of the

international photographic collection at the National

Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

KeywordsPhotographs, photography, 19th century photography, early

Australian photography, Australian photography,

international photography collection, National Gallery of

Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria photography

department, Art Gallery of New South Wales, National

Gallery of Australia, Melbourne, photographic

collections, curator.

2

George Baron Goodman, d. 1851

[Dr William Bland]

c. 1845

Daguerreotype (ninth plate daguerreotype in Wharton case) 7.5 x 6.3

cm

© State Library of New South Wales collection

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the purpose of

academic research

Introduction

Invented by Louis Daguerre in 1839, the daguerreotype - a

plate of copper coated in silver, sensitised to light by

being exposed to halogen fumes - was the first publicly

announced photographic process and the first to come into

3

widespread use. The first photograph taken in Australia

was a daguerreotype, a view of Bridge Street (now lost)

taken by a visiting naval captain, Captain Augustin Lucas

in 1841.1 The oldest surviving extant photograph in

Australia is a daguerreotype portrait of Dr William Bland

by George Barron Goodman taken in 1845 (see image above).

This daguerreotype is now in the State Library of New

South Wales collection.2

After these small beginnings, explored in Gael Newton’s

excellent book Shades of Light,3 the Melbourne Public Library

(later to become the State Library of Victoria) launched

the Museum of Art in 1861 and the Picture Gallery in

1864, later to be unified into the National Gallery in

1870, a repository for all public art collections, the

gallery being housed in the same building as the Library.4

The Pictures Collection (including paintings, drawings,

prints, cartoons, photographs and sculpture) was started

in 1859.5 The collection of photographs by the Library had

both moral and educative functions. Photographs of

European high culture reminded the colonists of links to

the motherland, of aspirations to high ideals, especially

in conservative Melbourne.6 Photographs of distant lands,

such as Linnaeus Tripe’s Views of Burma, document other

‘Oriental’ cultures.7 Photographs of settlement and the

development of Melbourne recorded what was familiar in an

unknown landscape. “Documentation of both the familiar and the

unknown intersected with the scientific desire for categorisation and

4

classification.”8

It is not the purview of this essay to dwell on the

development of photography in Australia during

intervening years between the 1860s - 1960s, but suffice

it to say that the collecting of photographs at the State

Library of Victoria continued the archiving of Australian

identity and place through the ability “to define the self, claim

the nation and occupy the world.”9 Australian photographic

practice followed the development of international

movements in photography in these years: art and commerce

from the 1860s - 1890s, Pictorialism from the 1900s -

1930s, Modernism in the 1930s - 1940s and documentary

photography from the 1940s - 1960s. The development of

Australian photography was heavily reliant on the forms

of international photography. Analysis of these years can

be found in Gael Newton’s book Shades of Light: Photography and

Australia 1839 - 198810 and Isobel Crombie’s book Second sight:

Australian photography in the National Gallery of Victoria.11

In 1959 the epic The Family of Man exhibition, curated by the

renowned photographer Edward Steichen from the Museum of

Modern Art, New York, toured Sydney, Melbourne and

Adelaide to massive crowds. Featuring 503 photographs by

273 famous and unknown photographers from 68 countries

this exhibition offered a portrait of the human

condition: birth, love, war, famine and the universality

of human experience all documented by the camera’s lens.12

5

In Melbourne the exhibition was shown in a car dealer’s

showroom (yes, really!) and was visited by photographers

such as Jack Cato, Robert McFarlane, Graham McCarter.13

The photographs in the exhibition, accompanied by text,

were printed “onto large panels up to mural size [and] gave The Family

of Man works an unprecedented impact, even given the role illustrated

magazines had played through most of the century.”14 This loss of the

aura of the original, the authenticity of the vintage

print, a print produced by the artist around the time of

the exposure of the negative, would have important

implications for the collection of international

photographs in the fledgling National Gallery of Victoria

photographic collection (even though Walter Benjamin saw

all photography as destroying the authenticity of the

original through its ability to reproduce an image ad

nauseum).15

As Benjamin observes in his Illuminations, “The enlargement of a

snapshot does not simply render more precise what in any case was visible

though unclear: it reveals entirely new structural formations of the subject.”16

Other ways of looking at the world also arrived in

Australia around the same time, namely Robert Frank’s

seminal book The Americans,17 a road movie photographic view

of American culture full of disparate angles, juke boxes,

American flags, car, bikes and diners.18

6

Beginnings

While legislatively the National Gallery had split from

the State Library of Victoria in 1944,19 it wasn’t until

August, 1968 that the National Gallery of Victoria moved

into it’s own building designed by Roy Grounds at 180 St

Kilda Road (now known as NGV International).20 In the

years leading up to the move the Trustees and Staff went

on a massive spending spree:

“But although the sources of income from bequests were limited during the

year [1967], a somewhat increased Government purchasing grant continued,

which, with the allowance made by the Felton Committee, seemed to

stimulate Trustees and Staff almost to a prodigality of spending. Perhaps, too,

an urge for as full a display as possible at the opening of the new Gallery

contributed; for by the end of the year the entire grant for purchase until the

end of June 1968 had been consumed, and as well some commitments made

for the future. Only donations made from private sources, and through the

generosity of the National Gallery society, enabled the rate of acquisition to

be maintained.”21

Unfortunately, this profligacy did not include spending

on photography. This was because the Department of

Photography was only formed in April 1967 after the

Director at the time, Dr Eric Westbrook, convinced the

Trustees of the Gallery “that the time had come to allow

photographs into the collection.”22 The impetus for establishing a

photography collection “was the growing recognition and promotion

7

of the aesthetics of photography.”23 The Department of Photography

at the NGV thus became the first officially recognised

curatorial photography department devoted to the

collection of photography as an art form in its own right

in Australia and one of only a few dedicated specifically

to collecting photography in the world.24 While the

collecting criteria of the NGV has always emphasised “the

primacy of the object as an example of creative expression,”25 the fluid

nature of photography was acknowledged in a 1967 report

on the establishment of the Department of Photography.26

The new department, however, did not gain momentum until

the establishment of a Photographic Subcommittee in

October 1969 that consisted of the Director of the

Gallery and three notable Melbourne photographers: Athol

Shmith, Les Gray and Chairman, Dacre Stubbs, along with

the Director of the National Gallery Art School, Lenton

Parr. Advising the Committee were honorary

representatives Albert Brown (in Adelaide) and Max Dupain

(in Sydney).27 The Photographic Subcommittee defined the

philosophies of the Department and began acquiring

photographs for the collection.28 While the Department was

located in the Gallery’s library and had no designated

exhibition space at this time,29 Committee members

stressed the need to make contacts with the international

art world and fact-finding missions were essential in

order to establish a curatorial department in Australia

as no photography department had ever been established in

8

Australia before. “Members were also concerned to position the new

Department in an international context (achieved initially through linking the

Gallery to an international exhibitions network and later by purchasing

international photography.”30

Financial support and gallery space was slow in

materialising and then (as now) “it was enlightened corporate and

individual support that would significantly help the NGV to create its

photography collection.”31 The first attributable international

photograph to enter the collection was the 21.8 x 27.5 cm

bromoil photograph Nude (1939) by the Czechoslovakian

photographer Frantisek Drtikol in 1971 (Gift of C. Stuart

Tompkins),32 an artist of which there remains only one

work in the collection, and other early international

acquisitions included twenty-seven documentary

photographs taken during NASA missions to the moon in the

years 1966 - 1969 (presented by Photimport in 1971)33 and

work by French photographer M. Lucien Clergue in 1972,

founder of the Arles Festival of Photography.34 Early

international exhibitions included The Photographers Eye from

the Museum of Modern Art in New York (facilitated through

Albert Brown’s connections with photography curator John

Szarkowski of MoMA).35

The purchasing of the Dritkol nude is understandable as

he is an important photographer of people and nudes.

“Drtikol made many portraits of very important people and nudes which

show development from pictorialism and symbolism to modern composite

9

pictures of the nude body with geometric decorations and thrown shadows,

where it is possible to find a number of parallels with the avant-garde works

of the period.”36 The acceptance of the set of twenty-seven

NASA photographs is understandable but still problematic.

Although some of the photographs are breathtakingly

beautiful and they would have had some social

significance at that time (the first lunar landing was in

1969), their relative ‘value’ as pinnacles of

international documentary photography, both aesthetically

and compositionally, must be questioned.37 One wonders on

what grounds the Photographic Subcommittee recommended

their acceptance at the very start of the collection of

international photography for the Department of

Photography when so many definitive photographs by

outstanding masters of photography could have been

requested as a donation instead. Similarly, the purchase

by the National Gallery of Victoria in 1980 of over 108

space photographs by NASA, Washington, D.C.

(manufacturer) for the international collection is

equally mystifying when there was a wealth of European

and American master photographers work being shown in

exhibitions around Melbourne (and sold at very low

prices, eg. $150 for a Paul Strand vintage print) that

did not enter the collection.

In 1972 Jenny Boddington (with a twenty year background

in documentary film)38 was appointed Assistant Curator of

Photography. She was selected from fifty-three

10

applicants,39 and was later to become the first full-time

curator of photography at the NGV, the first in Australia

and perhaps only the third ever full-time photography

curator in the world. In 1973, the Melbourne photographer

Athol Shmith, who sat on the Photographic Subcommittee,

visited major galleries and dealers in London and Paris

for five weeks and reserved small selections of non-

vintage prints for purchase by Henri Lartigue, Bill

Brandt, Paul Strand, Andre Kertesz, Edward Steichen and

Margaret Bourke-White40 (non-contemporary ie. vintage work

not being generally available at this time). Also in 1973

the corridor beside the Prints and Drawings Department

opened as the first photography exhibition space, to be

followed in 1975 by the opening of a larger photography

gallery on the third floor.41

In 1975 Boddington made a six-week tour of Europe, London

and America that included meeting photographers Andre

Kertesz and Bill Brandt and the Director of the Museum of

Modern Art, John Szarkowski.42 Boddington also spent four

weeks viewing photography at the MoMA, time that

radically changed her ideas about running the department,

including the decision that priority be given to the

acquisition of important overseas material. She states:

“My ideas about the running of my department are radically changed … I

believe that for some time in the future immediate priority and all possible

energy should be given to the acquisition of important overseas material,

remembering that ours is the only museum in Australia with a consistent

11

policy of international collecting, and that effort in the initiation and

mounting of exhibitions can be saved by showing some of the best work we

have already purchased.”43

As Suzanne Tate notes in her Postgraduate Diploma Thesis,

Boddington “was also determined to achieve autonomy from the

Photographic Subcommittee, and to act on her own judgment, as other

curators did.”44 Perhaps this understandable desire for

autonomy and the resultant split and aversion (towards

the Photographic Subcommittee) can be seen as the

beginning of the problems that were to dog the nascent

Photography department. In 1976 the Photographic

Subcommittee was discontinued although Les Gray (who

expressed a very ‘camera club’ aesthetic) continued to

act as honorary advisor.45 The Photography department

continued to collect both Australian and international

photography in equal measure (but of equal value?) and

held exhibitions of international photography from

overseas institutions (including the early exhibition The

Photographer’s Eye in 1968)46 and from the permanent

collection (such as an exhibition of work by Andre

Kertész, Bill Brandt and Paul Strand)47 in order to

educate the public, not only in the history of the medium

but how to ‘see’ photography and read ‘good’ photographic

images from the mass of consumer images in the public

domain.48

12

Paradigms and problems of international

photography collecting at the National Gallery of

Victoria

“It does not do to be impatient in the business of collecting for an art

museum. A public collection is a very permanent thing. It is really necessary to

think in terms of the future and how our photographs and our century will

appear in that future. We would like those in the future to inherit material

that is intelligible both for itself and in relation to the other arts; at the same

time there is the need to satisfy the present. A collection cannot be richer than

the responses of its artists but it is hoped that it will represent a rich trawl of

each historical period.”

Jenny Boddington 49

The current photography collection at The National

Gallery of Victoria consists of over 15,000 photographs

of which around 3,000 are by international artists (a

ratio of 20% whereas the ratio between Australian/

international photographers at the National Gallery of

Australia in Canberra is 60/40%).50 Dr Isobel Crombie, now

Assistant Director, Curatorial and Collection Management

and former Senior Curator of Photography at the National

Gallery of Victoria, notes in her catalogue introduction

“Creating a Collection: International Photography at the

National Gallery of Victoria,” from the exhibition Re_View:

170 years of Photography that several factors have affected

the collection of international photographs at The

National Gallery of Victoria. I have identified what I

13

believe to be the three key factors:

1. Lack of financial support

2. The purchasing of non-vintage prints

3. The dilemma of distance

Financial support

When the Department of Photography was set up at The

National Gallery of Victoria the lack of adequate funds

tempered the Photography Subcommittees purchasing

aspirations. This situation continued after the

appointment of Jenny Boddington and continues to this

day. Athol Shmith noted that there were two options for

building a collection: one was to spend substantial funds

to acquire the work of a few key photographers, the other

option (the one that was adopted) was a policy of

acquiring a small number of works by a wide range of

practitioners, a paradigm that still continues.51 “A broadly

based collecting policy was established to purchase work by Australian and

International practitioners from all periods of photographic history.”52

The majority of early acquisitions of the Department were

overwhelmingly Australian but this collection policy

broadened dramatically after the overseas travel of Athol

Shmith and Jenny Boddington.53 Cultural cringe was

prevalent with regard to Australian photography and it

14

was rarely, if ever, talked about as art. Australian

photography was still in the hands of the camera clubs

and magazines and influenced by those aesthetics... but

the ability to purchase the desired international work

was severely curtailed due, in part, to the low exchange

rate of the Australian dollar. In 1976 one Australian

dollar was worth approximately US 40 cents. Another

reason was the lack of money to purchase international

work. In the early 1970s the Department had approximately

$3,000 a year to purchase any work (international or

Australian) that gradually built up to about $30,000 per

annum in the mid 1970s. In 1981-82, this was reduced to

almost zero because of the financial crisis and credit

squeeze that enveloped Australia. This lack of funds to

purchase work was compounded by sky rocketing prices for

international photographs by renowned photographers in

the early 1980s.

While generous help over eight years from Kodak

(Australasia) Pty. Ltd had helped buy Australian works

for the collection (a stipulation of the funds),54 money

for international acquisitions had been less forthcoming.

In a catalogue text from 1983 Boddington notes,

“… classic, well-known photographs are now very expensive indeed. One can

only look back with sincere appreciation to the days when the department’s

purchasing budget was $1000 a year and the trustees agreed to buy 27 Bill

Brandts, whilst the National Gallery Society donated a further 13 from

15

‘Perspective of Nudes’, thus concluding out first major international purchase,

happily before Brandt’s prices quintupled in a single blow early in 1975.

Photography was then beginning to be a factor in the market place of art and

a budget of $1000 a year was no longer adequate - even for the purchase of

Australian work! Where funds are limited (as they are) a fairly basic decision

has to be made as to the direction a collection will follow. Here in Melbourne

we have on the whole focused on the purest uses of straight photography as

it reflects broad cultural concerns …”55

By 1976 the Felton Bequest purchased works by Julie

Margaret-Cameron (one image!) and the NGV purchased

thirty-four André Kertész, evidence that the status of

the Photography department was rising. Throughout the

remainder of the 1970s and early 1980s, eighty works were

acquired by artists such as Imogen Cunningham (five

images), Edward Muybridge (two images - the only two in

the collection), Lois Conner (three images) and Man Ray

(eleven images).56 In 1995 Isobel Crombie revised the

collecting policy of the Department and she notes in

“Collecting Policy for the Department of Photography, National Gallery of

Victoria (Revised October 1995),” Appendix 1 in Suzanne Tate’s

Postgraduate Diploma Thesis under the heading

‘International Photography’57 that, “Given our financial resources

extremely selective purchases are to be made in this area to fill those gaps in

the collection of most concern to students and practicing photographers.”58

Crombie further notes that the contemporary collection is

an area that needs much improvement whilst acknowledging

the dramatic increases in prices asked and realised for

16

prime photographs and the restricted gallery funds for

purchases.59

While today the importance of philanthropy, fund raising

and sponsorship is big business within the field of

museum art collecting one cannot underestimate the

difficulties faced by Boddington in collecting

photographs by international artists during the formative

years of the collection. As photography was liberated to

become an art form in the early 1970s through the

establishment of museum departments, through the

emergence of photographic schools and commercial

photographic galleries (such as the three commercial

photography galleries showing Australian and

international work in Melbourne: Brummels (Rennie Ellis),

Church Street Photographic Centre (Joyce Evans) and The

Photographers Gallery (Paul Cox, John Williams, William

Heimerman and Ian Lobb), photography was given a place to

exist, a place to breathe and become part of the

establishment. But my feeling is that the status of

photography as an art form, which was constantly having

to be fought for, hindered the availability of funding

both from within the National Gallery of Victoria itself

and externally from corporate and philanthropic

institutions and people.

To an extent I believe that this bunker mentally hindered

the development of the photographic collection at the

17

National Gallery of Victoria until much more recent

times. Instead of photography being seen as just art and

then going out and buying that art, the battle to define

itself AS art and defend that position has had to be

replayed again and again within the NGV, especially

during the late 1970s-1980s and into the early 1990s.60

This is very strange position to be in, considering that

the NGV had the prescience to set up one of the first

ever photography departments in a museum in the world.

Then to not support it fully or fund it, or to really

understand what was needed to support an emergent art

form within a museum setting so that the masterpieces

vital for the collection could to be purchased, is

perplexing to say the least. I wonder whether more could

not have been done to attract philanthropy and funds from

personal and big business enterprises to support

international acquisitions. I also wonder about the

nature of some of the international purchases for the

Department of Photography (the choice of photographer or

photographs purchased) and the politics of how those

works were acquired.

The purchasing of non-vintage prints

The paradigm for collecting international photographs

early in the history of the Department of Photography was

set by Athol Shmith in 1973 on his visit to Paris and

18

London.

“Typically for the times, Shmith did not choose to acquire vintage prints, that

is, photographs made shortly after the negative was taken. While vintage

prints are most favoured by collectors today, in the 1970s vintage prints

supervised by the artists were considered perfectly acceptable and are still

regarded as a viable, if less impressive option now.”61

This assertion is debatable. While many museums including

the NGV preferred to acquire portfolios of modern

reprints as a speedy way of establishing a group of key

images, Crombie notes in the catalogue essay to 2nd Sight:

Australian Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria that the

reason for preferring the vintage over the modern print

“is evident when confronted with modern and original prints: differences in

paper, scale and printing styles make the original preferable.”62 Crombie’s

text postulates that this sensibility, the consciousness

of these differences slowly evolved in the photographic

world and, for most, the distinctions were not a matter

of concern even though the quality of the original

photograph was not always maintained.63 I believe that

this statement is only a partial truth. While modern

prints may have been acceptable there has always been a

premium placed on the vintage print, a known value above

and beyond that of modern prints, even at the very dawn

of photography collecting in museums. I believe that

price (which is never mentioned in this discussion) is

the major reason for the purchase of non-vintage prints.

19

In Crombie’s “Collecting Policy for the Department of

Photography, National Gallery of Victoria (Revised

October 1995),” she notes under the heading ‘Past

Collecting Policy’ Point 1 that “Many non-vintage

photographs have been collected … Purchase of non-vintage

prints should not continue though we may we accept such

photographs as gifts on occasion.”64

I vividly remember seeing a retrospective of the work of

Henri Cartier-Bresson at the Dean Gallery in Edinburgh in

2005. One room consisted of small, jewel-like vintage

prints that were amazing in their clarity of vision and

intensity of the resolution of the print. In the other

three rooms there were large blown-up photographs of the

originals, authorised by the artist. Seen at mural size

the images fell apart, the tension within the picture

plane vanished and the meaning of the image was

irrevocably changed. Even as the artist’s intentions

change over time, even as the artist reprints the work at

a later stage, the photograph is not an autonomous object

- it becomes a post-structuralist textual site where the

artist and curator (and writers, conservators, historians

and viewers) become the editors of the document and where

little appeal can be made to the original intentions of

the author (if they are known).65 While change,

alteration, editing, revision and restoration represent

the true life of objects66 (and noting that the same re-

inscription also happens with vintage photographs), the

20

purchase of non-vintage prints eliminates the original

intention of the artist. This is not to say that the

modern printing, such as Bill Brandt’s high contrast

version of People sheltering in the Tube; Elephant and Castle,

underground station (1940 printed 1976, below) cannot become

the famous version of the image, but that some

acknowledgement of the history of the image must be made.

Ignoring the negative/print split is problematic to say

the least, especially if the original was printed with

one intention and the modern print with an entirely

different feeling. This is not a matter of refinement of

the image but a total reinterpretation (as in the case of

the Brandt). While all artists do this, a failure to

acknowledge the original vision for a work of art and the

context in which it was taken and printed - in Brandt’s

case he was asked by the War Office to record the Blitz,

in which Londoners sheltered from German air raids in

Underground stations - can undermine the

reconceptualisation of the modern print.

21

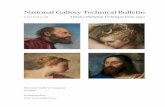

Bill Brandt

People sheltering in the Tube; Elephant and Castle, underground station

1940

Silver gelatin print

© Bill Brandt Archive © IWM Non-Commercial License

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

Civilians sheltering in Elephant and Castle London

Underground Station during an air raid in November 1940.

Elephant and Castle London Underground Station Shelter:

22

People sleeping on the crowded platform of Elephant and

Castle tube station while taking shelter from German air

raids during the London Blitz.

Bill BrandtPeople sheltering in the Tube; Elephant and Castle,

underground station

1940, printed 1976

Silver gelatin print

34.4 x 29.3 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, MelbournePurchased, 1974

© Bill Brandt Archive

23

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

NB. Note the removal of the man sitting up at right in

mid-foreground

The dilemma of distance

While the dilemma of distance is cited as an obstacle to

the collection of international photographs by the

Department of Photography in the early 1970s by Isobel

Crombie,67 this observation becomes less applicable by the

middle of the decade. Master prints from major

international photographers were available for purchase

in Australia by The National Gallery of Australia in

Canberra (which had been collecting photography since the

early 1970s),68 The Art Gallery of New South Wales (which

established a Department of Photography in 1974),69 and

The National Gallery of Victoria, through exhibitions at

newly opened commercial galleries in both Melbourne and

Sydney. Public touring exhibitions were held of the work

of international photographers, most notably British

Council exhibition of Bill Brandt in 1971, and the French

Foreign Ministry’s major exhibition of Cartier-Bresson in

1974.70

24

In Melbourne commercial galleries specialising in

photography and photographer run galleries had emerged,

namely Brummels established by Rennie Ellis in 1972, The

Photographers Gallery and Workshop founded by Paul Cox,

Ingeborg Tyssen, John F. Williams and Rod McNicoll in

1973 (the Gallery was taken over in late 1974 by Ian

Lobb, his first exhibition as director being at the

beginning of 1975; Bill Heimerman joined as joint

director at the beginning of 1976), and Church Street

Gallery established by Joyce Evans in 1977.71 At the

commercial galleries the main influence was

overwhelmingly American:

“The impact of exhibitions held by the NGV was reinforced by exhibitions of

the work of Ralph Gibson, William Clift, Paul Caponigro, Duane Michals and

Harry Callahan at The Photographers Gallery and by the series of lectures and

workshops that the artists conducted during those exhibitions. Joyce Evans

also organised important exhibitions during this period but again the focus

was American with work by Minor White, Jerry Uelsmann, Les Krims and

others.”72

Shows of American photography, many of which toured

extensively, became relatively commonplace and it was the

first time Australian photographers and the general

public had access to such a concentration of

international photography in a variety of styles.73 Ian

Lobb, who took over the running of the Photographers

25

Gallery in late 1974 (with Bill Heimerman), notes that

the first exhibition of international photography at the

gallery was that of Paul Caponigro in 1975.74

“We sold 22 prints which he told us was the second highest sale he had made

to that point. With the success of the Caponigro show, we closed the gallery

for a few months while the gallery was rebuilt. I took Bill as a business

partner, and he made a trip to the USA to set-up some shows. From 1975,

every second show was an international show.”75

Lobb observes that,

“The initial philosophy was simply to let people see the physical difference

between the production of prints overseas and locally. After a while this

moved from the Fine Print to other concerns both aesthetic and conceptual.

The gallery at best, just paid for itself. During international shows the

attendance at the gallery was high. During Australian shows the attendance

was low.”76

From 1975 - 1981 The Photographers Gallery held

exhibitions of August Sander (German - arranged by Bill

Heimerman), Edouard Boubat (France), Emmet Gowin (USA -

twice), Paul Caponigro (USA - twice), Ralph Gibson (UK -

twice, once of his colour work), William Eggelston (USA),

Eliot Porter (USA), Wynn Bullock (USA), William Clift

(USA), Harry Callahan (USA), Aaron Siskind (USA - twice,

once with a show hung at Ohnetitel) Jerry Uelsmann (USA),

Brett Weston (USA). There was also an exhibition of

26

Japanese artist Eikoh Hosoe (Japan) and his Ordeal by Roses

series in 1986. These exhibitions comprise approximately

60% of all international exhibitions at The Photographers

Gallery during this time, others being lost to the

vagaries of memory and the mists of time. Prices ranged

from $100 per print (yes, only $100 for these

masterpieces!!) in the early years rising to $1500 for a

print by Wyn Bullock towards the end of the decade.77 At

Church Street Photographic Centre the focus was

predominantly on Australian and American artists, with

some British influence. Artists exhibited other than

those noted above included Athol Shmith, Rennie Ellis,

Wes Placek, Fiona Hall, Herbert Ponting, Julia Margaret

Cameron, Eugène Atget, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jack Cato,

Norman Deck, Jan Saudek, Robert Frank, Edouard Boubat,

Jerry Uelsmann and Albert Renger-Patzsch to name just a

few.78

The purchasing of vintage prints by major international

artists from these galleries by the National Gallery of

Victoria was not helped by the allegedly strained

relationships that Boddington had with the directors of

these galleries. The feeling I get from undertaking the

research is that one of the problems with Boddington’s

desire to achieve autonomy and make her own decisions

about what to purchase for the Photography Department

(being strong willed) was that she ignored opportunities

that we right here in Melbourne - because of the

27

aforesaid relationships and lack of money (a lack of

support from the hierarchy of the National Gallery of

Victoria). Her under-standable desire to be independent

coupled with relations with other professionals working

in the photographic field was to cost the gallery dearly

in the long run.

ConclusionIt would be a great pity if the oral history of the early

exhibition of international photographers in Melbourne

was lost, for it is a subject worthy of additional

research. It would also be interesting to undertake

further research in order to cross-reference the

purchases of the Department of Photography at the

National Gallery of Victoria in the years 1975-1981 with

the independent international exhibitions that were

taking place at commercial galleries in Melbourne during

this time. What international photographs were purchased

from local galleries, what choices were made to purchase

or not purchase works, what works were actually purchased

for the collection and what were the politics of these

decisions?

For example, during 1976 nine photographs by the Italian

photographer Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000) entered the

collection as well as nineteen photographs by German

photographer Hedda Morrison; in 1977 twelve photographs

entered the collection by a photographer name Helmut

28

Schmidt (a photographer whose name doesn’t even appear

when doing a Google search). Under what circumstances did

these photographs come into the collection? While these

people might be good artists they are not in the same

league as the stellar names listed above that exhibited

at The Photographers Gallery and Church Street

Photographic Centre. Questions need to be asked about the

Department of Photography acquisitions policy and the

independent choices of the curator Jennie Boddington,

especially as the international prints were here in

Melbourne, on our doorstep and not liable to the tyranny

of distance.

Dr Isobel Crombie notes that the acquisitions policies

were altered so that there was no major duplication

between collections within Australia79 but it seems

strange that, with so many holes in so many collections

around the nation at this early stage, major

opportunities that existed to purchase world class

masterpieces during the period 1975-81 were missed by the

Department of Photography at the NGV.

While Crombie acknowledges the preponderance of American

works in the collection over European and Asian works she

also notes that major 20th century photographers that you

would expect to be in the collection are not, and blames

this lack “on the massive increases in prices for international

photography that began in the 1980s and which largely excluded the NGV

from the market at this critical time.”80 Crombie further observes

29

that major contemporary photographers work can cost over

a million dollars a print and the cost of vintage

historical prints are also prohibitively high,81 so the

ability to fill gaps in the collection is negligible,

especially since the photography acquisitions budget is

approximately 0.5-1 million dollars a year.82

Crombie’s time scale seems a little late for as we have

seen in this essay, opportunities existed locally to

purchase world class prints from master international

photographers before prices rose to an exorbitant level.

Put simply, the NGV passed up the opportunity to purchase

these masterworks at reasonable prices for a variety of

reasons (personal, political and financial) before the

huge price rises of the early 1980s. They simply missed

the boat.

I believe that this subject is worthy of further in-depth

research undertaken without fear nor favour. While it is

understandable that the NGV would want to protect it’s

established reputation, the NGV is a partial public

institution that should not be afraid to open up to

public scrutiny the formative period in the history of

the international collection of photography, in order to

better understand the decisions, processes and

photographic prints now held in it’s care.

Dr Marcus Bunyan, May 2015 Word count:

30

5,592

Front cover of John Szarkowski’s book The Photographers Eye,

originally published by The Museum of Modern Art in 1966

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

31

André Kertész

A Bistro at Les Halles, Paris

1927

Gelatin silver photograph

17.7 x 24.7 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1976

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

32

Julia Margaret Cameron

Mrs Herbert Duckworth, her son George, Florence Fisher and H. A. L. Fisher

c. 1871

Albumen silver photograph

31.0 x 22.7 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the

assistance of the Herald & Weekly Times Limited, Fellow,

1979

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

33

Imogen Cunningham

Leaf pattern

c. 1929; printed 1979

Gelatin silver photograph

33.0 x 26.1 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased 1979

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

34

NASA, Washington, D.C. (manufacturer)

Instrument called Gnomon to determine size and distance of objects on moon

1969

Gelatin silver photograph on aluminium

49.0 x 39.0 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented by Photimport, 1971

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

35

purpose of academic research

Neil Armstrong / NASA, Washington, D.C. (manufacturer)

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot, walks on the surface of the Moon

near the leg of the Lunar Module (LM)

1969

Colour transparency

50.8 x 40.6 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

36

Purchased 1980

Photograph used under conditions of “fair use” for the

purpose of academic research

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical

Reproduction. 1936

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Shocken,

1969

Boddington, Jennie. International Photography: 100 images from the

Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Adelaide: The Art

Gallery of South Australia, 1983

Boddington, Jennie. Overseas Travel by Assistant Curator of

Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1976

Boddington, Jennie. Modern Australian Photographs. Melbourne:

National Gallery of Victoria, 1976

Cox, Leonard B. The National Gallery of Victoria, 1861-1968: The Search

for a Collection. Melbourne: The National Gallery of Victoria;

Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd, 1971

Crombie, Isobel. Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne:

National Gallery of Victoria, 2009

Crombie, Isobel. Second sight: Australian photography in the National

Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria,

2002

Downer, Christine. “Photographs,” in Galbally, Ann [et

al]. The first collections: the Public Library and the National Gallery of

37

Victoria in the 1850s and the 1860s. Parkville, Vic.,: The

University of Melbourne Museum of Art, 1992, pp. 73-79

Frank, Robert. The Americans. Washington: Steidl/National

Gallery of Art, Revised edition, May 30, 2008

Newton, Gael. Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839-

1988. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, Collins, 1988

Tate, Suzanne. Photographic Collections in Victoria: Waverley City

Gallery, Horsham Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria: An Analysis

of Past History and Future Directions. The University of Melbourne:

Postgraduate Diploma Thesis, 1998

Endnotes

1. Anon. “Photography in Australia,” on Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 01/08/2014.2. “Daguerreotype Portrait of Dr William Bland circa 1845,” on the State Library of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 27/07/2014.3. Newton, Gael. Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839-1988. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, Collins, 1988[Online] Cited 02/06/2014.4. Fennessy, Kathleen. “For ‘Love of Art’: The Museum of Art and Picture Gallery at the Melbourne Public library 1860 - 1870,” in The La Trobe Journal 75, Autumn, 2005, p. 5 [Online] Cited 27/07/2014.5. Anon. “Pictures,” on the State Library of Victoria website [Online] Cited 02/09/2010. No longer available.6. Fox, Paul. “Stretching the Australian Imagination: Melbourne as a Conservative City,” in The La Trobe Journal 80,

38

Spring, 2007, p. 124 [Online] Cited 27/07/2014.7. Tsara, Olga. “Linnaeus Tripe’s ‘Views of Burma’,” in The La Trobe Journal 79, Autumn, 2007, p. 55 [Online] Cited 27/07/2014.8. Crombie, Isobel. “Likenesses as if by magic: The earlyyears 1840s - 1850s,” in Second sight: Australian photography in theNational Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2002, p. 15.9. Fox, Paul Op. cit., p. 124.10. Newton, Gael. Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839-1988. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, Collins, 1988[Online] Cited 02/07/2014. Chapter 11 “Live in the Year 1929” and Chapter 12 “Commerce and Commitment.”11. Crombie, Isobel. Second sight: Australian photography in the National Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2002. See chapters “In a new light: Pictorialist photography 1900s - 1930s” (p.38), “New Photography: Modernism in Australia 1930s - 1940s” (p.50)and “Clear statements of actuality: Documentary photography 1940s - 1960s” (p.64).12. Anon. “The Family of Man,” on Wikipedia [Online] Cited 02/09/201413. Newton, Gael. Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839-1988. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, Collins, 1988[Online] Cited 02/06/2010. Chapter 13 “Photographic Illustrators: The Family of Man and the 1960s - an end and a beginning” and Footnote 13.14. Ibid., See also the layout and size of the photographic murals on the Musuem THE FAMILY OF MAN, Chateau de Clervaux / Luxembourg website , the only permanent display of the exhibition left in the world. [Online] Cited 02/09/2014.15. “Benjamin’s work balances, often with paradoxical results, tensions between aspects of experience: the experiences simultaneously of being too late and too early (too soon) in the temporal dimension (c.f. Hamlet’s“the time is out of joint”) and being both distant and close (in the spatial dimension), and anyway of being both temporal and spatial. The concept of “aura,” which is one of Benjamin’s most influential contributions, is best understood in terms of these tensions or oscillations. He says that “aura” is a “strange web of

39

space and time” or “a distance as close as it can be.” The main idea is of something inaccessible and elusive, something highly valued but which is deceptive and out ofreach. Aura, in this sense, is associated with the nineteenth century notions of the artwork and is thus lost, Benjamin argues, with the onset of photography. At first photographs attempted to imitate painting but very quickly and because of the nature of the technology photography took its own direction contributing to the destruction of all traditional notions of the fine arts.”Phillips, John. On Walter Benjamin. [Online] Cited 02/06/2014. “One might generalize by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence.”Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. 1936, Section 2. [Online] Cited 02/06/2014.16. Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Shocken, 1969, p. 236.17. Frank, Robert. The Americans. Washington: Steidl/National Gallery of Art, Revised edition, May 30, 2008.18. Newton, op. cit., Chapter 13.19. Anon. “A chronology of events in the history of the State Library of Victoria,” on the State Library of Victoria website. [Online] Cited 03/06/2010. No longer available.20. See Cox, Leonard B. The National Gallery of Victoria, 1861 - 1968: The Search for a Collection. Melbourne: The National Gallery of Victoria; Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd, 1971.21. Ibid., p. 378.22. Crombie, Isobel. op. cit., Introduction p. 7.23. Crombie, Isobel. op. cit., Introduction p. 7.24. Westbrook, Eric. “Minutes of the Photographic Subcommittee” 22/07/1970 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. Photographic Collections in Victoria: Waverley City Gallery, Horsham Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria: An Analysis of Past History and Future Directions. The University of Melbourne: Postgraduate Diploma Thesis, Chapter One, 1998, pp. 12-13. Other institutions included the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, Berlin Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin, The Victoriaand Albert Museum, London and the Art Institute of

40

Chicago.25. Crombie, Isobel. op. cit., Introduction p. 6.26. Westbrook, Eric and Brown, Albert. “Establishment of Photography at the Victorian Arts Centre,” in Minutes of Trustees Reports, NGV, 4th April, 1967, p. 886 quoted in Crombie, Isobel. op cit., Introduction p. 6. Footnote 2.27. See Crombie, Isobel. op cit., Introduction p. 8 and Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 14-15.28. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1969 - 70.Melbourne, 1970, np quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 14-15.29. NGV Photographic Subcommittee. Report. Melbourne, 1970, p. 2 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. p. 16.30. Crombie, Isobel. op cit., Introduction p. 8.31. Crombie, Isobel. “Creating a Collection: International Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009, p. 7.32. Ibid.,33. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1971-72. Melbourne, 1970, np quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. p. 16.34. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1972-73. Melbourne, 1970, np quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. p. 16.35. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1969-70. Melbourne, 1970, np quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. p. 16.36. Anon. “Frantisek Drtikol,” on Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 06/10/2014.37. Some of these images have been shown for the first time in over twenty years in the 2009 exhibition Light Years:Photography and Space in the third floor photography galleryat NGV International.

41

38. “After Eureka Stockade Boddington went to work at Film Australia and in 1950 worked for the GPO Film Unit. With the introduction of television she went to work at the ABC as an editor. She and her second husband cameraman Adrian Boddington would then set up their own company Zanthus Films. After his death she became the curator of photography at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1971.”Allen, J. “Australian Visions. The films of Dahl and Geoffrey Collings,” in Eras Journal Edition 4, December 2002, Footnote 33 [Online] Cited 14/10/201439. Minutes of the NGV Photographic Subcommittee. Melbourne, 16/05/1972 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 17-18.40. Crombie, Isobel. “Creating a Collection: International Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009, p. 9.41. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1974-75. Melbourne, 1975, p. 24 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 17-18.42. Boddington, J. Overseas Travel by Assistant Curator of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1976,pp. 1-3 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 18-19.43. Boddington, J. quoted in Crombie, Isobel. “Creating aCollection: International Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009, p. 9.See also Boddington, J. quoted in quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 18-19.44. Boddington, J. Overseas Travel by Assistant Curator of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1976,pp. 1-3 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 18-19.45. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1975-76. Melbourne, 1976, p. 26 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National

42

Gallery of Victoria. pp. 18-19.46. See Crombie, Isobel. “Creating a Collection: International Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009, p. 9.47. NGV Trustees. National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 1975-76. Melbourne, 1976, p. 27 quoted in Tate, Suzanne. op cit., Chapter 2: The Photography Department of the National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 18-19.48. See Crombie, op. cit., p. 9.49. Boddington, Jenny. Modern Australian Photographs. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1976. Catalogue essay.50. See Crombie, op. cit., p. 7.“The first formulation of policy in the Gallery’s annual report of 1976/77 stated the aim was to ‘develop a department of photography which will include both Australian and overseas works. The Australian collection will be historically comprehensive, while the collection of overseas photographers will aim to represent the work of the major artists in the history of photography’. Since that statement of intent thirty years ago, the collection has grown to include over 16,000 works. There are approximately sixty per cent Australian to forty per cent international photographs, a ratio that has remained constant over the years.”O’Hehir, Anne. “VIP: very important photographs from the European, American and Australian photography collection 1840s - 1940s” exhibition 26 May - 19 August 2007 on the National Gallery of Australia website [Online] Cited 12/10/2014.51. See Crombie, op. cit., p. 9.52. Crombie, Isobel. “Collecting Policy for the Department of Photography, National Gallery of Victoria (Revised October 1995),” in Tate, Suzanne. Photographic Collections in Victoria: Waverley City Gallery, Horsham Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria: An Analysis of Past History and Future Directions.The University of Melbourne: Postgraduate Diploma Thesis,1998, p. 73. Appendix 153. Crombie, Isobel. Second sight: Australian photography in the National Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2002, p. 954. Boddington, Jennie. Modern Australian Photographs. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1976. Catalogue essay.55. Boddington, Jennie. International Photography: 100 images from

43

the Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Adelaide: The Art Gallery of South Australia, 1983. Catalogue essay.Here we must acknowledge the contradiction between the quotations at footnotes 52 and 55, where the former proposes a broad based collecting policy from all eras both internationally and locally and, a few years later, the other proposes a focus on the purest uses of straightphotography (in other words pure documentary photography)as it reflects broad cultural concerns.56. Tate, Suzanne. Photographic Collections in Victoria: Waverley City Gallery, Horsham Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria: An Analysis of Past History and Future Directions. The University of Melbourne: Postgraduate Diploma Thesis, 1998, pp. 19-2057. Crombie, Isobel. “Collecting Policy for the Department of Photography, National Gallery of Victoria (Revised October 1995),” cited in Tate, Suzanne. Ibid., Appendix 1 ‘International Photography’ Point 2, 1900-1980, p. 73.58. Ibid.,59. Ibid.,60. This battle is still being fought even in 2014. See Jones, Jonathan. “The $6.5m canyon: it’s the most expensive photograph ever - but it’s like a hackneyed poster in a posh hotel,” on The Guardian website 11/12/2014[Online] Cited 15/11/201461. Crombie, Isobel. “Creating a Collection: International Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009, p. 962. Crombie, Isobel. Second sight: Australian photography in the National Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2002, p. 1063. Ibid., p. 1064. Crombie, Isobel. “Collecting Policy for the Department of Photography, National Gallery of Victoria (Revised October 1995),” in Tate, Suzanne. Photographic Collections in Victoria: Waverley City Gallery, Horsham Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria: An Analysis of Past History and Future Directions.The University of Melbourne: Postgraduate Diploma Thesis,1998, p. 73. Appendix 165. McCaughy, Patrick. Review of ‘ Securing the Past: Conservation in Art, Architecture and Literature’ by Paul Eggert on The Australian

44

newspaper website [Online] December 2nd, 2009. Cited 01/01/201566. Ibid.,67. Crombie, Isobel. “Creating a Collection: International Photographyat the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Re_View: 170 years of Photography. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009, p. 968. O’Hehir, Anne. op. cit.,69. Dean, Robert. “Foreign Influences in Australian Photography 1930 - 80.” Lecture delivered at Australian Photographic Society Conference (APSCON), Canberra, 2000, p. 10. [Online] Cited 01/01/2015 Download the lecture (40kb pdf)70. Ibid.,71. Ibid., See also footnote 2872. Ibid., p. 1173. Ibid.,74. Lobb, Ian. Text from an email to the author, 20th May, 201475. Ibid.,76. Ibid.,77. Ibid.,78. Evans, Joyce. Text from an email to the author, 6th September 201479. Crombie, op. cit., p. 1080. Ibid.,81. Ibid.,82. Vaughan, Gerard. Lecture to Master of Art Curatorshipstudents by the Director of the National Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne, 30/03/2010.

45