Austrian Demography and Housing Demand: Is There a Connection

Austrian Public Choice August 2012 BVd B

Transcript of Austrian Public Choice August 2012 BVd B

1

AUSTRIAN PUBLIC CHOICE:

AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION

Jean-Philippe Bonardi

University of Lausanne

Faculty of Business and Economics (HEC)

Lausanne – CH1015 - Switzerland

Tel : +41 21 692 3440

E-mail: [email protected]

Rick Vanden Bergh

University of Vermont

School of Business Administration

55 Colchester Avenue, 304 Kalkin Hall

Burlington, Vermont 05405

Tel: (802) 656-8720

Fax: (802) 656-8279

Email: [email protected]

This version: August 2012

JEL categories: B53; D72

2

AUSTRIAN PUBLIC CHOICE:

AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to explore empirically some of the key

propositions that can be derived when one combines insights from Public

Choice and Austrian economics. We call this approach Austrian Public

Choice. These key propositions are (1) that political markets are dynamic

processes driven by the action of suppliers and demanders of public

policies behaving as entrepreneurs, (2) that these political entrepreneurs

are ignorant ex ante of factors that can matter as the regulatory process

unfolds, suggesting that they imperfectly anticipate what will ultimately

matter for policy decisions, and (3) that these political entrepreneurs learn

over time and use local knowledge to discover future opportunities in

political markets. Using a dataset of utility initiated rate reviews in the

U.S. electricity industry, we find support for these propositions, which

suggests that Austrian economics could shed new lights on questions

typically raised by Public Choice scholars.

JEL categories: B53; D72

3

In their introduction to a special issue of the Review of Austrian Economics devoted to

Austrian perspectives on Public Choice, Boettke and Lopez wrote: “One of the challenges to

Austrian economics in general is to establish more and broader empirical relevance, to show

that its analytical principles are applicable to standard questions and can provide answers that

standard economics cannot. Such accomplishments are necessary to… “pass the market test”.

… we too emphasize the need for applied-theoretic and empirical work to come from Austrian

economists” (Boettke & Lopez, 2002: 114). The purpose of this paper is to move in this

direction and show the relevance of the Austrian lens for the study of political and regulatory

decisions.

Following Buchanan and Tullock (1965) or Stigler (1971), Public Choice scholars have

showed how private incentives play a considerable role in shaping public policy decisions.

Self-interested politicians or bureaucrats participate in political markets and negotiate with

various interest groups to set policies, therefore questioning views of public officials as

benevolent actors. Public Choice work generally use standard microeconomic tools such as

utility maximization, game theory and thus concentrates on solutions at equilibrium. However,

DiLorenzo (1988), Holcombe (2002) or Ikeda (1997, 2003) have highlighted how the Austrian

focus on dynamic processes –rather then equilibrium–, knowledge imperfections and

entrepreneurship could be used with great benefits to shed new light on the standard Public

Choice research program. In this paper, and for simplicity, we call this combination Austrian

Public Choice.1

Apart from the fact that Austrian researchers usually do not see empirical research as a key

part of their research program –which will not be discussed here– another reason for the lack of

1 Compared to Ikeda (1997) or Boettke and Lopez (2002), who use the term ‘Austrian Political Economy’ to

characterize the study of governments’ decisions and their welfare implications in a broad sense, we adopt a

4

empirical studies is certainly related to the data challenge it constitutes. For instance, exploring

whether actors behave as entrepreneurs in political markets, a key aspect in an Austrian

approach (DiLorenzo, 1988), requires observing when actors engage in political action, which

is often quite challenging, especially in a large sample. Another challenge certainly comes from

the difficulty to capture the informational/knowledge problems faced by the actors and the

surprises generated by political processes, as well as their impact on the final public policy

adopted. Last, how can one demonstrate that actors make mistakes or do not make perfect

decisions in the context of political processes, due to the fact that they cannot know in advance

the behaviors that others (either demanders or suppliers of public policies) will adopt?

In this paper, we attempt to address some of these challenges by looking at rate-reviews in

the U.S. electricity sector. Our dataset allows us to identify precisely when a political process

(the rate-review process) starts, why some actors decide to initiate this process and invest in

political activities (utilities initiating the rate-review process and lobbying accordingly), how

some other actors react to it (other potential demanders of public policies, especially rivals such

as consumers or environmental activists, who lobby as well), and how politicians or

bureaucrats, as suppliers of public policies, accommodate these demands.

This empirical set-up also provides an opportunity to compare utilities’ expectations when

they engage in political actions with the factors that, in the end, really drive the final policy

decision (in that case the variation in the allowed rate of return attributed to the utility). This

will allow us to examine empirically the knowledge limitations players face when they first

seize political opportunities, and how much of these limitations come from the dynamic nature

of political markets.

narrower focus here and restrict our analysis to political processes and the dynamics of political markets. Hence

we use the term Austrian Public Choice.

5

The rest of the paper is composed of four sections. In the first, we outline the theoretical

pillars of Austrian Public Choice and identify a few propositions to guide our empirical study.

The second presents the empirical context and our strategy to explore Austrian insights in

political environments. The third section discusses the methodology and presents the results.

The last section discusses these results and concludes.

Austrian Public Choice: Key insights

The foundations of what we call Austrian Public Choice have been laid out in several

pieces, in particular Boettke, Coyne and Leeson (2007), DiLorenzo (1988), Ikeda (1997) and

Holcombe (2002). In this section, we review this literature and identify key propositions that

will serve as the basis of our empirical investigation. Compared to typical Public Choice

models (see Mueller (2003) for a review), an Austrian approach to political economy issues has

several characteristics.

The first important feature is that policy-making, from an Austrian lens, cannot be modeled

as a static equilibrium state, but needs to be considered as a dynamic, competitive and

evolutionary process (Benson, 2002). Within this process, each actor involved (both demanders

and suppliers of public policies) search for opportunities to take advantage of the process, and

by doing so differentiate their actions and prevent the equilibrium described in standard Public

Choice models from taking place (Ikeda, 2003). Demanders of public policies might still start

this process in certain cases, but their actions are heterogeneous and often hard to predict for

their rivals. Suppliers of public policy, similarly, are numerous (politicians, bureaucrats,

regulators) and do not passively respond to potential vote support from interest groups (Benson,

2002). They actively seek ways through which to create new opportunities for wealth transfers

(Holcombe, 2002). In other words, all players within the policy-making process act as

entrepreneurs would in the context of economic markets as defined by Hayek (1945) and

6

Kirzner (1973 & 1992): they observe, discover and act upon (political) market opportunities

(Rizzo & Driscoll, 1985).

Bureaucrats for instance act as entrepreneurs and discover opportunities to expand their

resources while applying/enforcing the new regulations put forward by politicians and interest

groups. As described in Breton & Wintrobe (1982), this bureaucratic entrepreneurial discovery

process involves competition for budgets, power and influence within regulatory systems.

Bureaucrats, within the regulatory system, often benefit from a fair amount of discretion, in

spite of control by politicians and ultimately by courts. In the short term, maximizing their

utility might mean responding to interest groups’ demands in a way that favors vote

maximization for policy-makers (i.e., by giving groups that can provide the highest voting

support to politicians policy decisions close to what these groups want). This would be a result

compatible with traditional Public Choice insights.

However, there might also be cases where bureaucrats/regulators, because they already

have ample resources (large budgets, wealth of information, experience, credibility, etc.) might

decide to sacrifice short-term obedience to politicians in order to favor longer term objectives

such as the building of a reputation that will allow them to stimulate interest group rivalry in

the future and thus extract higher rents from policy-making processes in the future.2

Viewing policy-making as a process generates another important feature of Austrian Public

Choice: the knowledge problem and the divergence between intended and actual outcomes

(Ikeda, 2003). Because actors have only limited knowledge when they make decisions, errors

regularly occur during the policy-making process and unintended outcomes emerge. Bruce

Benson summarizes this ‘knowledge problem’ in political environments when he states: “The

knowledge problem suggests, among other things, that there are too many uncontrolled margins

2 Rents in that case can be of different kinds, such as extended influence over an industry or even over several

opportunities, better career opportunities, etc.

7

and unanticipated responses for a rule designer to recognize and anticipate, in part because the

changes create a new set of opportunities that have not previously been available” (Benson,

2002: 235). In other words, actors in an Austrian approach have to deal with ex ante ignorance

of factors that can affect outcomes. Even after conscientiously scanning their environment and

planning accordingly, actors end up making mistakes, overestimating certain factors,

underestimating other factors, and completely missing others. The implication is that neither

demanders of public policies nor suppliers of public policies will, in most cases, obtain exactly

what they expect from policy-making processes (Shane, 2000). The assumption of rational

ignorance is not, in itself, inconsistent with Austrian political economy for most voters.

However, the idea that actors know enough about the relevant probabilities so that, on average,

errors are only random and cancel each other out, is inconsistent with Austrian political

economy for most voters. An Austrian approach would predict systematic errors made by

actors in the policy process because, as all other actors act in an entrepreneurial way, none has

accurate information about their own real probability of success.

One last important component of an Austrian contribution to the Public Choice research

program is that local knowledge is critical to account for the way actors make decisions in

political markets. As suggested by Hayek (1945), knowledge differs across time and place, but

this does not imply that actors cannot accumulate valuable information and knowledge over

time and therefore learn throughout policy processes. Learning, and the local knowledge that an

actor has accumulated over time within a specific political market setting, will thus be an

important aspect of the future decisions that actor will take. Demanders of public policies will

vary not only in their ability to generate voting support to politicians (as in standard Public

Choice models) but also in the experience and knowledge they hold about how to proceed and

gain an advantage within political processes.

8

To summarize, we will try to empirically explore four propositions that define Austrian

Public Choice, i.e.:

- Both demanders and suppliers of public policies act in an entrepreneurial way, looking for

opportunities to change the regulatory status quo to their advantage;

- Political entrepreneurs build on knowledge, learnt over time through previous

experiences, to discover future opportunities in political markets;

- Local knowledge, in particular, is key to generate entrepreneurial discoveries in political

processes;

- Entrepreneurial behaviors within political processes generate a knowledge/ignorance

problem, i.e. an impossibility to know ex ante (even with some probability) all the factors

that influence final policy outcomes and how they will do so. This knowledge problem

pushes actors (both demanders and suppliers) to make prediction errors, i.e., underestimate,

overestimate or even ignore key factors that will ultimately affect the public policy

decision.

Empirical Setting: Rate Reviews in the U.S. Electric Utility Industry

To explore these propositions, we use a dataset of rate-reviews across the fifty states in the

U.S. electric utility industry. In the U.S., profit levels of utilities are regulated under a financial

rate-of-return regime by state (as opposed to federal) agencies. Utilities are able to improve

their financial performance by achieving – through political activities – higher prices and a

higher rate-of-return. State regulatory agencies (Public Utility Commissions, hereafter “PUCs”)

determine the rate-of-return that a utility is allowed to earn, and hence the final rates charged to

consumers, through an administrative process, commonly termed a “rate review”. Utilities are

able to file for rate reviews whenever they wish. Upon initiation of a rate review, a series of

public hearings is held where the utility and competing interest groups present arguments and

9

information supporting their positions about justifiable rates-of-return and rate levels. At the

end of this process, PUC commissioners make a final decision on the rate-of-return for the

utility and rates that final consumers pay. Even if they are not supposed to be instrumental in

this type of decision, politicians –i.e., legislators and governors– exercise some monitoring

power and control over regulators throughout the process (Hyman, 2000).

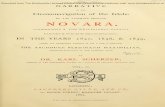

Figure 1 provides an overview of the different stages of the rate-review process.

------------------------------------------------

Insert Figure 1 about here

------------------------------------------------

This industry context affords a number of advantages for our empirical investigation.

Below, we explain how different aspects of an Austrian Public Choice approach can be

explored empirically using these data.

Identifying political entrepreneurship among demanders of public policies

The rate review process is characterized by an intense information exchange between

policy-makers, the utility and other interest groups (Hyman, 2000). Since the provision of

information regarding policy consequences and alternatives is a central characteristic of actors’

behaviors during public policy processes, the utility’s initiation of a rate review is a rational

strategy driven by some calculation or plan by the firms, and can therefore be viewed, from an

Austrian perspective, as an entrepreneurial behavior.3 Because we are able to identify when the

utility (a demander of public policy) files a formal regulatory request for rate review, we can

identify when it seizes an opportunity to start a policy-making process, i.e. discover an

entrepreneurial opportunity in the political market. Note that the Rate of Return (ROR) is firm-

specific: each ROR applies to a single utility only even though there are multiple utilities

3 Utilities are in fact likely to engage in activities that complement their regulatory filing with the agency, such as

gaining the support of the state governor and legislature (through lobbying, grassroots mobilization, coalition

building and financial campaign contributions). For lack of available data on the period under study here, we will

10

operating within a given state. This will allow us to identify individual behaviors, and not just

collective ones as is often the case for political issues.

In the first stage of our empirical analysis, we will therefore account for the decision by

utilities to initiate a rate review at a certain point in time. Using a probit model, we will explore

the political market conditions which affect the firm’s decision (more on this below). We

expect to find that this choice will be driven by a variety of political market conditions, which

include the rivalry potentially created by competing interest groups (residential consumers,

industrial consumers and environmental activists) but also the rivalry faced by legislators and

governors for reelection and the amount of resources held by PUCs for reasons mentioned

earlier. In effect, the rate review process affords the opportunity for us to explore how a

particular Demander (i.e., investor owned utilities) is entrepreneurial in response to

characteristics of both the demand- and supply-sides of the political market.

Characterizing political entrepreneurship among suppliers of public policy

On the supply-side, multiple regulatory and political institutions have a potential role in rate

reviews. Final decisions are in the jurisdiction of state PUCs. However, PUCs are overseen by

state legislatures that determine their budgets, that can conduct hearings on specific decisions

and that can ultimately overturn PUCs through new legislation. PUC commissioners are

additionally typically appointed by state governors, giving a further lever to state politicians to

exert pressure on PUC decisions.4 From an Austrian point of view, political opportunities for

utilities are thus likely to be shaped by characteristics of both the elected state politicians and

the regulatory agency.

Capturing uncertainty, or the difference between intended and actual outcomes

not explore this dimension, but these behaviors are commonplace during the rate review process and, in our

analysis, we will assume they take place (Hyman, 2000). 4 In ten U.S. states PUC commissioners are elected. We control for this variation in our empirical analysis. Below we

discuss how PUC selection rules might influence the choice of a utility to initiate and the overall policy outcome.

11

Another advantage of using electric utility rate reviews for our empirical setting is that they

provide a good measure of the final outcome of the political process. As part of their final rate

review rulings, PUCs determine the financial rate-of-return on equity (hereafter ‘ROR’) that the

utility may earn. This ROR, in turn, is used to determine the allowed rate levels (i.e., prices a

utility can charge to its customers). Since, all else being equal, higher RORs lead to higher

profits, utilities are assumed to prefer higher RORs. While PUCs have a statutory duty to set

rates that are “just and reasonable”, in practice they have considerable discretion to set rates

and RORs within some implicit range.5 This will allow us to provide an analysis of the actual

outcome of the policy process, compared to the intended outcome that utilities expect to get.

A key aspect of our empirical approach will be, therefore, to estimate both the determinants

of the rate review initiation with the determinants of the allowed ROR. From a standard Public

Choice perspective, since demanders of public policy have extensive knowledge about the

process and the factors that will ultimately affect the final decision, one might predict that

utilities will initiate when political market conditions are favorable and that nothing else will

affect the final outcome. In other words, the decision made by the utility to initiate a rate review

will have captured and controlled for the key characteristics of the political market and thus any

uncertainty created by the rate review process. On the other hand, from an Austrian point of

view, a utility will plan according to its predictions regarding political market conditions, but

this utility will turn out to have only imperfectly anticipated what will happen during the

political process. Many factors including the entrepreneurial behaviors of rival interest groups

or of politicians and regulators will create unanticipated conditions within the political process

and will therefore generate differences between what the firm expects and the final outcome.

Learning local knowledge and the discovery of future political opportunities

5 Allowed RORs have historically differed significantly across utilities, states and time. For instance, the highest

allowed ROR by a state PUC during 1980 was 16.80% while the lowest was 12.50%.

12

Rate-reviews are also phenomena which tend to be repeated over time. We observe and

analyze utility decisions over a period of 10 years. Thus, we can estimate whether utilities

learn from previous periods and whether this learning matters either for their decision to engage

in political activities and for the final determination of the allowed ROR by the regulator. We

assume that when a utility initiates a rate review and goes through the rate review process the

firm is adding to its stock of local knowledge about the political market. We use this to analyze

whether local knowledge affects both the entrepreneurial decision to initiate and the regulatory

outcomes.

Furthermore, using our data, we can identify when a utility observes other utilities initiate

rate reviews. When a given utility observes other utilities engaged in the regulatory process,

we assume the focal utility is adding to their stock of general knowledge about the political

market. Thus, we can compare the effects of learning and accumulating local versus general

knowledge on the entrepreneurial actions of the utility and on the final regulatory outcomes.

Sample

We obtained information on all rate review processes initiated by the population of 190

investor-owned electric utilities during the period 1980 to 1992. These utilities represent those

operating in all fifty U.S. states except Alaska and Nebraska. While the age of our data may

raise concerns, we concentrate on the 1980-1992 period since rate reviews were initiated by

utilities and not by the PUCs. After 1992, PUCs also initiated rate reviews with the aim of

reducing utility rates. Using data after 1992 would have made it difficult to identify whether

rate-reviews were initiated by a utility or by the PUC, thus compromising our analysis of

entrepreneurial actions by Demanders within the political process.

13

The 1980 to 1992 panel of data creates a potential sample of 2470 utility-year observations.

After eliminating observations due to missing data, we are left with 1651 utility-year

observations.6 The sample includes 499 rate reviews initiated by utilities.

Variables

Dependent variables

As explained earlier, we will consider various models to isolate the specificities of an

Austrian Public Choice approach. To model utilities’ entrepreneurial actions, we will consider

probit models capturing the conditions in which these utilities decide to initiate a rate review. In

these models, the dependent variable Firm initiated rate review takes a value of 1 if the utility

decides to initiate a rate review in a specific year and 0 if it does not.

To measure the outcome of the political process (related to a utility firm’s specific action)

we calculate the change in the allowed ROR ( Allowed ROR) since the utility’s previous rate

review. We use the change in ROR rather than the absolute level since this allows us to control

for constant firm-level factors that influence the absolute ROR. We obtained the rate review

data from a private firm, Regulatory Research Associates, that tracks PUC decisions and cross-

checked a sample of rate review results with data available in annual volumes of the National

Association of Regulatory Utility Commissions (NARUC) for accuracy.

Independent variables

Interest group activities: We use three variables to capture interest groups’ competitive

activities and thus important characteristics of the Demanders in the political market. Consumer

Advocate is a measure of the degree of residential utility consumer organization per state. In the

U.S. utilities sector, 30 states have created consumer advocacy offices to represent residential

6 To measure our dependent variable (change in allowed ROR) we need a baseline measure of allowed ROR.

Thus, we eliminate observations on utilities until they initiate their first rate review in the data. We also eliminate

observations if we are missing information on the allowed rate of return for a firm since this makes it impossible to

calculate the change in allowed ROR. The need for a baseline and the missing data on allowed ROR resulted in a

14

utility consumer interests before state regulatory agencies and courts (Holburn and Vanden

Bergh, 2006). Consumer advocates, which are publicly funded and which have statutory power

to participate in rate review procedures, can provide strong opposition to utility requests for rate

increases (Holburn and Spiller, 2002). The variable Consumer Advocate equals one if a

consumer advocacy office existed in a given state in a particular year and zero otherwise.

Rivalry can also come from industrial consumers who, due to higher average levels of

consumption than residential consumers, have stronger incentives to organize. Industrial

Consumers, a time-varying variable, is equal to the industrial percentage share of electricity

consumption in each state. Data on electricity consumption by consumer sector was obtained

from the Energy Information Administration. Finally, we use Environmental activists to capture

the extent to which state populations participate in environmental and other non-governmental

activist organizations. We use data from the Sierra Club which is the largest environmental

NGO in the U.S. Such groups have historically been particularly active against utilities

regarding the citing of new power generation plants and the environmental impacts of existing

facilities. The variable Environmental activist is equal to the total number of Sierra Club

members in the state divided by state population (in thousands). Annual information on state

membership was provided directly to us by the Sierra Club.

Voting support generated by the utility. To capture the idea that a utility will be more

likely to influence policy in a favorable direction when it can provide voting support for policy-

makers, we also include Market Share for a utility, defined as the total megawatt hours (MWh)

of electricity provided by the utility divided the total MWh provided by all utilities in the state.

This measure captures both the idea of firm size and its importance as electricity provider

within the state, i.e. important political variables for politicians and regulators. The assumption

reduction of 311 observations. We also eliminated 475 observations arising from missing data to measure market

share. Finally, we have missing data on three utilities resulting in 33 additional observations being eliminated.

15

is that if a utility is a major player within a PUC’s jurisdiction, then that utility is more likely to

provide strong political support to suppliers of public policies.

Politicians’ activities: To attempt to capture conditions under which elected politicians may

extend pressure on the PUC, we develop proxies for the degree of rivalry among elected

politicians. We construct two dummy variables based on the winning vote margin in the most

recent state gubernatorial and legislative elections. For the executive branch (governors), we

consider rivalry intense if the margin of electoral victory between the winning and second-place

candidates is less than 5%. In this case there is likely to be intense political competition during

the next electoral cycle. For the legislative branch, given the importance of party control of the

legislature, we consider rivalry intense if the margin of control by the majority party (measured

by the number of seats in the combined upper and lower chambers) is less than 5%. Thus, we

create dummy variables for Governor rivalry and for Legislature rivalry which are equal to one

if rivalry is intense and zero otherwise. We use dummy rather than continuous variables since

the underlying distributions of governor vote and legislature party majorities are not normal but

highly skewed. We collected this information from annual volumes of The Book of the States.

Bureaucrats’ entrepreneurial activities: As argued earlier in this paper, a dynamic theory

of regulators’ behaviors could suggest that PUCs with greater resources will be more likely to

diverge from the pure vote-maximizing approach of politicians to try to build long-term capital

such as reputation. Therefore, regulators with greater resources are also more likely to take

risks and make decisions against a strong political actor like a utility. Again, we use several

measures of resources. Our first, PUC Budget per state capita, is a measure of financial

resources. Second, we construct a measure of PUC commissioner experience since experience

may partially substitute for financial resources: Tenure PUC is equal to the sum of each

commissioner’s tenure in years divided by the total number of commissioners on the PUC. We

16

expect that more experienced commissioners will have better information/local knowledge

regarding utility rate review requests. We obtained annual information on PUC budgets and the

identities of PUC commissioners from annual reports of the National Association of Regulatory

Utility Commissioners, annual volumes of The Book of the States and the websites of individual

PUCs. We also include a variable that may influence the weight that PUCs put on utility versus

consumer interests in their ROR decisions. Elected PUC is a dummy variable equal to one in

states where PUC commissioners are elected and zero otherwise. PUC commissioners are

elected by the voting population in 10 states and are appointed by the governor in other states.

Prior research suggests that elected PUCs place greater weight on consumer welfare (Besley

and Coate, 2003). Details on commissioner selection were obtained from the Book of the States.

Learning local political knowledge: The Austrian Public Choice framework stresses the

role of local knowledge in the ability of political entrepreneurs to discover opportunities. We

introduce three measures that will help us distinguish local from more general types of

knowledge. We create the variable Local knowledge to capture the stock of knowledge that the

utilities has potentially learned about the PUC and the local politicians. Local knowledge is

equal to the total number of rate reviews the utility has experienced in the past (our sample for

this variable started in 1970).

To estimate the real impact of this local knowledge on political entrepreneurial discovery,

we also compute General knowledge which is a proxy for the utility’s stock of general

knowledge about the political market. General knowledge (state) and General knowledge

(region) are equal to the number of rate reviews for other utilities operating in the same

state/region that the focal utility has observed in the past. The knowledge associated with these

measures are arguably of a much more general nature since it does not take into account how

17

the firm’s own characteristics are considered by the local regulators and politicians nor the

firm’s own past interactions with the political market.

Control variables

We control for a number of factors that may affect a utility’s performance in the rate review

process as well as the decision to initiate a rate review. These variables can be interpreted by

the fact that regulators and politicians, when they allocate public policies in order to get

reelected or reappointed, have to take into account some public interest dimensions and not

only the private interests related to interest groups lobbying and highlighted by the Public

Choice approach. Interest rates on treasury securities enter into a PUC’s decision on the

allowed ROR since these are a benchmark to measure the cost of capital. Interest rate change,

measured in percentage points, is the difference between the interest rate on ten year Treasury

bills at the given time minus the interest rate at the time of the last rate review. Change fuel cost

is the percentage change in a utility’s average fuel costs (on a per Btu basis) since the last rate

review, and is driven mainly by external market forces. Increases in the cost of utilities’ fuel

purchases, as occurred during the early 1980s, directly reduce utility profits, thereby increasing

the probability that utilities will initiate rate reviews. In the selection equation, we also control

for the absolute level of fuel costs. Since absolute costs are inversely related to profits, we

expect a positive relationship between absolute costs and the probability that utilities initiate.

We measure Average fuel cost as the average price of fuel per Btu purchased by electric

utilities within a state. Fuel cost data is published by the Energy Information Administration.

To control for varying economic conditions across the States, we include a measure of the

Change per capita income (lagged one year) which is equal to the annual percentage change in

18

per capita income in the state. Voter pressure on utility rates may be inversely correlated with

recent economic growth trends. We gathered this data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

A summary of the variables and descriptive statistics can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

-------------------------------------------

Insert Tables 1 and 2 about here

-------------------------------------------

Table 1 provides statistics for variables included in the full sample of utility-year

observations used in the probit models (firms that choose to initiate a rate review) while Table

2 provides statistics for variables included in the Allowed ROR (OLS regression) model.

Methodology

Empirically, our investigation will move in several stages with the purpose of exploring

step by step how the different aspects of an Austrian Public Choice approach improve our

understanding of public policy decisions and guide our empirical analysis. First, we will use an

ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model accounting for a baseline of what might be seen

as a traditional Public Choice approach. Variables capturing the impact of various interest

groups and of various policy-makers on the Allowed ROR will be included. We will then

explore entrepreneurial political behaviors of utilities by exploring their decision to initiate rate

review processes. We will therefore introduce and discuss a set of probit models (Maddala

1983) which allow us to analyze this choice. Within these probit models, and as a third step, we

will then add variables considering the role of knowledge, both general and local, in political

entrepreneurial behaviors. Last, we will consider a two-stage Heckman model (Heckman,

1979) which allows us to analyze how the utilities’ entrepreneurial decision to initiate a rate-

review in the first stage has an effect on the second stage PUC decision regarding the

Allowed ROR. We use this two-stage model to help estimate the total marginal impact of

political entrepreneurial behaviors on public policies. Furthermore, this two-stage model will

19

allow us to consider which dimensions create the ignorance problem we introduced in the

previous section, by comparing the factors a firm considers relevant to the PUC decision when

the utility initiates a rate-review with the factors that still affect the ultimate outcome of the

policy-making process after the firm initiates. If firms do not face the ignorance problem, then

we would expect that the decision to initiate to account entirely for the observed variation in the

PUC decision over allowed ROR.

RESULTS

The first model we consider to start our discussion is a model capturing what might be

considered as a straightforward ‘traditional’ Public Choice analysis, i.e. a model that does not

include utilities’ political entrepreneurship in the Austrian sense. Table 3 presents the results

for an OLS regression with changes in the rate-of-return as the dependent variable and

variables characterizing the demand (interest group rivalry) and the supply (politicians and

regulators) sides of political markets as independent variables. To account for unobserved

variations related to firms’ characteristics, we also include firm fixed effects in the regression.

-----------------------------------

Insert Table 3 about here

-----------------------------------

Results indicate that, beyond economic control variables, the variables having a statistically

significant impact on public policy decisions are variables related to the supply side of political

markets, and in particular the variables characterizing the regulator’s behaviors. Elected PUC

and Tenure PUC both have a negative and significant impact on the rate-of-return allocated to

each utility firm. From a Public Choice perspective, this seems to indicate that regulators that

have the most knowledge and consumer connection occupy the best position for creating strong

bargaining power vis-à-vis utilities. This fits with arguments indicating that players that truly

control the policy-making process are the most likely to extract rent from such a process.

20

To consider how an Austrian Public Choice perspective changes the traditional Public

Choice perspective, we now introduce utilities’ behaviors as political entrepreneurs. The OLS

analysis above does not take into account that the subset of utilities that engage in rate reviews

may have done so due to differential opportunities in the political market. As mentioned

earlier, utilities can, but do not have to initiate rate reviews. If utilities are behaving

entrepreneurially, they are likely to initiate a rate review when they have identified an

opportunity to turn the public policy process to their advantage. We thus consider two probit

models with the dependent variable Firm initiated rate review. Results of the probit models can

be seen in Table 4. The independent variables in the first model we consider are the same

demand and supply dimensions presented in the baseline OLS model presented in Table 3.

Column 1 in Table 4 provides the raw coefficient estimates from the probit model, whereas

column 2 calculates the marginal effects related to the different independent variables on the

probability of initiating. We present the marginal effects separately due to nonlinearities in the

probit estimation (Maddalla 1983).

------------------------------------

Insert Table 4 about here

------------------------------------

The results presented in Model 1 do provide support for an Austrian-style hypothesis that

utilities seek entrepreneurial opportunities in the political market. It appears that the utility is

concerned not only with the supply side characteristics, but also with the structure of the

demand side of the political market to determine when to initiate a rate review. On the supply

side, when we observe an Elected PUC or when the PUC Budget increases we see a reduced

likelihood that a utility initiates a rate review by nearly 17% or 3% respectively. These results

are consistent with the notion that a utility is less likely to engage with a political actor as the

attractiveness of the supply side of the political market declines.

21

We see similar effects for the demand side of the market. First, those utilities that possess

attractive features for the policy makers (i.e., Market share is larger) are more likely to initiate

by about 15.6%. However when the rivalry with other Demanders increases, utilities are less

likely to engage with the PUC. An increase in the strength of Environmental Activists or

Industrial Consumers the likelihood that a utility will initiate a rate review declines by nearly

2.9% or 31.4% respectively.

In Model 2 (columns 3 and 4) of the same Table 4, we present estimated coefficients and

marginal effects when we add our knowledge variables. Comparing the statistical significance

of the Local knowledge with the General knowledge variables is consistent with an Austrian

perspective. When a firm’s own knowledge increases, they are more likely to initiate a rate

review. However, gaining knowledge by observing others does not appear to have a significant

effect on political entrepreneurship. We interpret this result as consistent with an Austrian view

of policy-making processes, in which the knowledge that matters for entrepreneurs is mainly

local knowledge rather than the general knowledge gained from observing other utilities going

through rate-reviews). While the significance of some of the other political market variables

changes when we introduce knowledge, there appears to be a robust relationship between

characteristics of the supply and demand side of the political market and a utility incentive to

act entrepreneurially. The main interpretation is that utilities are more likely to act

entrepreneurially when the political market is more attractive. The political market

attractiveness improves when PUC budgets decline, PUC commissioners are appointed, and

when environmental activists are not as strong.

In the last part of our empirical analysis, we turn to a model taking into account both the

utilities’ political entrepreneurial behaviors (initiation of the rate-review process) and the final

outcome regarding public policy (the rate-review decision by the PUC). We therefore estimate

22

a Heckman two-stage sample selection model which incorporates the utility’s first-stage

decision to initiate a rate review (Heckman, 1979) into the second-stage decision of the PUC to

change allowed ROR. In table 5, we present the estimated coefficients along with the estimated

total marginal effects that different characteristics have on the final PUC decision. The first

stage results are identical to Model 2 presented in Table 4. The second stage coefficient

estimates now take into consideration the entrepreneurial decision of the utility. Given

nonlinearities in the estimation of the two-stage model (Heckman, 1979), we estimate the

marginal effects separately and present these estimates in the third column of Table 5. The

significance of the Inverse Mills Ratio shows the importance of taking into account political

entrepreneurial behaviors and their impact on policy-making processes. Failing to take the

entrepreneurial behaviors into account would create a bias in the coefficient estimates on the

factors that affect the PUC decision. Significance also suggests that we can reject the null

hypothesis at the 5% level of confidence that the decision to initiate has no effect on the final

policy outcome. This provides support for the Austrian perspective that utilities are

entrepreneurial in their decision to engage with the PUC and that this decision is not

independent of the PUC rate review process.

-------------------------------------

Insert Table 5 about here

------------------------------------

Turning to our key variables, we find good statistical support for some of the predictions

related by the Austrian Public Choice approach. The analysis of the results in Table 5 provides

several interesting insights. First, several political market variables appear to be significant in

the first stage (selection equation) but not in the second stage (regression): PUC budget,

Environmental Activists, and Consumer Advocate. Our interpretation of these joint results is

that the factors associated with these variables were correctly predicted by the firms when they

23

decided to initiate. In other words, the utilities understood how these factors could affect PUC

decisions negatively and managed these in its entrepreneurial choice to engage with the

political market. Through an understanding of when to be entrepreneurial, the utilities did not

experience any added uncertainty associated with these political market factors. On the other

hand, the uncertainty created by longer Tenure PUC and when operating in a state with an

Elected PUC seems to have been underappreciated by utilities: the coefficient associated with

both Tenure PUC and Elected PUC are significant in the first stage, but also in the second stage

(both with a negative sign).

Interestingly for an Austrian argument, the variable Legislature Rivalry displays a

coefficient estimate that was not significant in the first stage but that became significant in the

second stage. Again, our interpretation of these results is that the impact of this dimension,

related to the behaviors of regulators and politicians, was not understood ex ante by utilities. In

other words, the behaviors of regulators and politicians in the political process created

conditions that were largely ignored and not anticipated by utilities. These results related to the

supply side of political markets are thus quite consistent with the Austrian view.

Now that we control for the entrepreneurial choice of utilities to initiate when political

markets are more favorable, we can estimate the overall marginal effect that different political

market characteristics have on a PUC decision to change the allowed ROR. The estimated

marginal effects are largely consistent with an Austrian Public Choice perspective. When

political markets are less favorable, the marginal effect on the change in allowed ROR is

negative. We see statistically significant negative marginal effects for PUC Budget, Tenure

PUC, Environmental Activists, Consumer Advocate, and Elected PUC. The magnitude of these

effects are economically significant as they range from about a 3% to about a 20% effect on the

change in allowed ROR relative to the mean of -0.43. Additionally when a firm increases its

24

own knowledge, it has a statistically significant positive marginal effect of close to 10% on the

change in allowed ROR (marginal effect of .04 while average allowed ROR = -0.43)

CONCLUSION

This article sets out to empirically explore some of the key propositions of Austrian Public

Choice. Overall, results are supportive and suggest that Austrians have something to bring to

the study of how political markets work. Key findings can be summarized by the following

points. First, firms involved in public policy processes (in this case, electric utilities) behave as

political entrepreneurs in the sense that they scan the competitive environment in the demand

side as well as the characteristics of the supply side of the political market, looking for

opportunities to change regulations in their favor. This fits with Kirzner’s definition of

entrepreneurship in economic markets (Kirzner, 1992).

Second, our study also uncovers the important role played by knowledge, especially local

knowledge, on entrepreneurship in political markets. Compared to general knowledge

accumulated by observing other firms going through rate-reviews, the knowledge that firms

have learnt through their own experiences with their state regulator is much more likely to

impact their decision to engage in political activities and also affect favorably the final policy

decision. This is in line with the role of knowledge in markets as characterized by Hayek

(1945).

Third, other demanders, competing against the initiating firm, also act in an entrepreneurial

way, introducing surprises into the process. Our empirical analysis suggests that suppliers of

public policies, both regulators and politicians, are the ones that are particularly likely to trigger

these surprises and uncertainty within political processes. Other demanders of public policies

(residential consumers, activists, industrial consumers) seem to matter much less. This result is

25

probably specific to the U.S. electricity sector. However, this result is also broadly compatible

with the Austrian view of entrepreneurship, starting with Mises (1949) or Rothbard (1962 &

1985), who stress the importance of property rights in entrepreneurial decisions: entrepreneurial

decisions, characterized by profits and losses, matter really for firm owners. In the case of

political decisions, a parallel can be made there. Regulators or politicians all have some form of

property rights over public policies, whereas consumers or activists do not.

In a similar vein, our analysis shows that politicians’ and regulators’ behaviors are the ones

that create true uncertainty that is hard for utilities to predict and plan for. When considered

from a perspective that is ‘out of the equilibrium’, suppliers of public policies create more

uncertainty than is generally assumed in most Public Choice models.

As in any empirical work, this paper has many limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the effort is focused on decisions made by one type of actor (utilities). The decisions and

the uncertainty created by other actors’ entrepreneurial behaviors (consumers, activists,

politicians, regulators, etc.) are assumed rather than observed. Second, the firms’ political

activities during the rate-review process are assumed but not measured. For instance, we do not

have data on lobbying expenditures or campaign contributions. Adding observations on these

data would certainly strengthen the approach presented here.

Third, and more importantly, real implications of the Austrian approach are in the nature of

the regulation process, and on its implications in terms of welfare and institutional

comparisons. As this article only attempts to empirically explore some foundations of Austrian

Political Economy, it is limited in its ability to participate in important debates on these

questions, such as that of Virginia and the Chicago schools regarding the costs and harm

generated by the political market process (Benson, 2002). We leave that for future research.

26

Finally, in addition to showing relevance compared to mainstream approaches, another

potential benefit from empirical investigations in Austrian political economy might be to

generate questions. The results presented here can be considered from this point of view as

well. For instance, it seems that certain aspects of the political process, or rather the behaviors

of certain actors within that process, can be better predicted than others. It seems for instance

that the rivalry generated by consumer advocates can be fairly well assessed ex ante by utilities,

whereas other behaviors such as those of Sierra Club activists or of legislators generate

systematic errors by utilities. In other words, are there certain factors in political markets that

generate a higher level of uncertainty, and therefore clusters of errors, among actors than

others? In the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, manipulated interest rates play that role of

generating clusters of errors among entrepreneurs; are there similar mechanisms in political

markets? Future work on Austrian Public Choice probably needs to provide some answers to

these questions.

27

References

Benson, B.L. 2002. Regulatory Disequilibrium and Inefficiency: The Case of Interstate

Trucking. Review of Austrian Economics. 15: 2/3, 229-255.

Besley, T. and Coate, S. 2003. Elected versus Appointed Regulators. Journal of the European

Economics Association, 1, 5: 1176-1206.

Boettke, P.J., Coyne, C.J., Leeson, P.T. 2007. Saving Government Failure Theory from Itself:

Recasting Political Economy from an Austrian Perspective. Constitutional Political

Economy. 18, 2: 127-143.

Boettke, P.J., Lopez, E.J. 2002. Austrian Economics and Public Choice. Review of Austrian

Economics. 15: 2/3, 111-119.

Breton, A., Wintrobe, R. 1975. The Equilibrium Size of a budget maximizing Bureau: a Note of

Niskanen's Theory of Bureaucracy. Journal of Political Economy. 83, 1: 195-207.

Buchanan, J. and Tullock, G. 1962. The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of

constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

DiLorenzo, T.J. 1988. Competition and Political Entrepreneurship. Review of Austrian

Economics. 2, 1: 59-71.

Hayek, F. A. 1945. The Use of Knowledge in Society. American Economic Review, 35, 4:

519-530.

Heckman, J.J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 47: 153-161.

Holcombe, R.G. 2002. Political Entrepreneurship and the Democratic Allocation of Economics

Resources. Review of Austrian Economics. 15: 2/3, 143-159.

Holburn, G.L.F. and Spiller, P. 2002. Institutional or Structural: Lessons from International

Electricity Sector Reforms, in The Economics of Contracts: Theories and Applications p.

463-502, editors Eric Brousseau and Jean-Michel Glachant, Cambridge University Press.

Holburn, G.L.F., and Vanden Bergh, R.G. 2006. Consumer capture of regulatory institutions:

The diffusion of public utility consumer advocacy legislation in the United States. Public

Choice, 126: 45-73

Hyman, L.S. 2000. America’s electric utilities: Past, present, and future. (7th

ed.). Vienna, VA:

Public Utilities Reports.

Ikeda, S. 1997. Dynamics of the mixed economy: Towards a theory of Interventionism. London:

Routledge.

28

Ikeda, S. 2003. How Compatible are Public Choice and Austrian Political Economy? Review of

Austrian Economics, 16: 1, 63-75.

Kirzner, I.M. 1973. Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kirzner, I.M.1992.The Meaning of Market Process. New York: Routledge.

Lopez, E.J. 2002a. The Legislator as Political Entrepreneur: Investment in Political Capital.

Review of Austrian Economics. 15: 2/3: 211-228.

Lopez, E.J. 2002b. Congressional Voting on Term Limits. Public Choice. 112: 405-431.

Maddalla, G. 1983. Limited dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Mises, L.1949. Human Action. Henry Regnery Company: Chicago.

Mueller, D. 2003. Public Choice III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizzo, M., O'Driscoll, G. 1985. The Economics of Time and Ignorance. New York: Basic

Blackwell.

Rothbard, M.N. 1962. Man, Economy and State. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing.

Rothbard, M.N. 1985. Professor Hebert on Entrepreneurship. Journal of Libertarian Studies, 7,

2: 281-286.

Shane, S. 2000. Prior Knowledge and the Discovery of Entrepreneurial Opportunities.

Organization Science. 11, 4: 448-469.

Stigler, G. 1971. The theory of economic regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and

Management Science, 2: 3-21.

29

Table 1: Descriptive statistics

Full sample

Variable Mean S.D. MIN MAX

Firm initiated rate review 0.30 0.46 0 1

PUC budget 2.02 1.48 0.23 10.58

Tenure PUC 3.63 2.62 0 17

Governor Rivalry 0.21 0.41 0 1

Legislature Rivalry 0.09 0.29 0 1

Market share 0.29 0.26 0 1

Environmental Activists 1.50 1.08 0.29 6.97

Industrial Consumers 0.27 0.08 0.08 0.53

Consumer Advocate 0.58 0.49 0 1

Elected PUC 0.14 0.34 0 1

Change per capita income 0.06 0.03 (0.06) 0.28

Interest rate change (0.85) 2.28 (6.25) 4.49

Change fuel cost (1.54) 20.46 (54.84) 147.14

Average Fuel Cost 1.68 0.82 0.45 6.33

Local knowledge 6.24 2.78 1 17

General knowledge (state) 17.13 12.23 0.00 51

General knowledge (region) 72.83 31.03 13 133

n=1,651

Table 2: Descriptive statistics

Subsample of firms that initiate rate reviews

Variable Mean S.D. MIN MAX

Allowed ROR -0.43 1.37 -4.25 3.25

PUC budget 1.77 1.25 0.23 10.58

Tenure PUC 3.33 2.61 0 17

Governor Rivalry 0.23 0.42 0 1

Legislature Rivalry 0.08 0.28 0 1

Market share 0.30 0.25 0.00 1

Environmental Activists 1.46 1.00 0.29 6.36

Industrial Consumers 0.27 0.08 0.08 0.49

Consumer Advocate 0.58 0.49 0 1

Elected PUC 0.08 0.28 0 1

Change per capita income 0.07 0.03 0.00 0.28

Interest rate change -0.29 2.37 -6.25 4.49

Change fuel cost 2.08 20.34 -52.90 147.14

Average Fuel Cost 1.82 0.93 0.45 6.33

Local knowledge 7.00 2.87 2 17

General knowledge (state) 18.36 12.73 0 49

General knowledge (region) 73.03 31.44 13 133

n=499

30

Table 3: Regression model

Dependent Variable: Allowed ROE

OLS

PUC budget -0.180

(0.126)

Tenure PUC -0.115***

(0.042)

Governor Rivalry -0.070

(0.162)

Legislature Rivalry 0.449

(0.346)

Market share -0.371

(1.959)

Environmental Activists -0.130

(0.223)

Industrial Consumers 1.851

(2.991)

Consumer Advocate 0.183

(0.392)

Elected PUC -3.010**

(1.467)

Change per capita 0.976

income (2.652)

Interest rate change 0.339***

(0.038)

Change fuel cost -0.007

(0.005)

Average Fuel Cost 0.572***

(0.184)

Constant 0.465

(1.181)

Observations 499

Adjusted R2

Firm Fixed Effects

0.372

YES Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

31

Table 4: Probit models (coefficient estimates and marginal effects)

Dependent Variable: Firm initiated rate review

Model 1 Model 2

Probit Marginal Probit Marginal Standard Effects Knowledge Effects

PUC budget -0.086*** -0.029*** -0.091*** -0.031***

(0.027) (0.009) (0.028) (0.010)

Tenure PUC -0.010 -0.003 -0.042*** -0.014***

(0.015) (0.005) (0.016) (0.005)

Governor Rivalry 0.119 0.041 0.123 0.042

(0.085) (0.029) (0.087) (0.029)

Legislature Rivalry -0.081 -0.028 -0.199 -0.067

(0.123) (0.042) (0.128) (0.043)

Market share 0.455*** 0.156*** 0.247 0.084

(0.133) (0.046) (0.155) (0.052)

Environmental Activists -0.086** -0.029** -0.116*** -0.039***

(0.036) (0.012) (0.041) (0.014)

Industrial Consumers -0.913** -0.314** 0.457 0.155

(0.463) (0.159) (0.508) (0.172)

Consumer Advocate -0.101 -0.035 -0.157** -0.053**

(0.073) (0.025) (0.079) (0.027)

Elected PUC -0.566*** -0.169*** -0.266* -0.085**

(0.127) (0.032) (0.143) (0.042)

Change per capita 2.029 0.697 2.877*** 0.312***

Income (1.293) (0.444) (1.055) (0.118)

Interest rate change 0.052*** 0.018*** 0.036* 0.012*

(0.019) (0.006) (0.020) (0.007)

Change fuel cost 0.005** 0.002** 0.005*** 0.002***

(0.002) (0.001) (0.002) (0.001)

Average Fuel Cost 0.050 0.017 0.094** 0.032**

(0.044) (0.015) (0.046) (0.016)

Local knowledge 0.125*** 0.042***

(0.015) (0.005)

General knowledge (state) 0.000 0.000

(0.004) (0.001)

General knowledge (region) -0.001 -0.000

(0.001) (0.000)

Constant -0.135 -1.203***

(0.229) (0.324)

Observations 1,651 1,651 1,651 1,651 Log likelihood -959.78 -921.26

Standard errors in parentheses

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

32

Table 5: Heckman model (coefficient estimates and marginal effects)

Dependent Variable -- Allowed ROR

2nd Stage 1st Stage Total Marginal Effect on

Allowed ROE Firm initiated rate review Allowed ROR

PUC budget -0.161 -0.091*** -0.029***

(0.104) (0.028) (0.009)

Tenure PUC -0.082** -0.042*** -0.013***

(0.040) (0.016) (0.005)

Governor Rivalry -0.165 0.123 0.039

(0.156) (0.087) (0.028)

Legislature Rivalry 0.532* -0.199 -0.063

(0.299) (0.128) (0.040)

Market share -0.550 0.247 0.078

(1.572) (0.155) (0.049)

Environmental Activists -0.321 -0.116*** -0.037***

(0.204) (0.041) (0.013)

Industrial Consumers 1.330 0.457 0.145

(2.447) (0.508) (0.161)

Consumer Advocate 0.310 -0.157** -0.050**

(0.343) (0.079) (0.025)

Elected PUC -2.476** -0.266* -0.084*

(1.113) (0.143) (0.045)

Change per capita -1.347 2.877*** 0.228***

Income (2.644) (1.055) (0.106)

Interest rate change 0.314*** 0.036* 0.012*

(0.037) (0.020) (0.006)

Change fuel cost -0.010** 0.005*** 0.002***

(0.005) (0.002) (0.001)

Average Fuel Cost 0.543*** 0.094** 0.030**

(0.155) (0.046) (0.015)

Local knowledge 0.125*** 0.040***

(0.015) (0.005)

General knowledge (state) 0.000 0.000

(0.004) (0.001)

General knowledge (region) -0.001 -0.000

(0.001) (0.000)

Constant 1.344 -1.696***

(0.997) (0.300)

Observations 499 1,651

Firm Fixed Effects YES

Inverse Mills Ratio Significant YES**

Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

33

Figure 1: Utility rate reviews as a political process

The utility firm

initiates the process

and asks for a rate

review

The Public Utility

Commission opens

up an investigation,

evaluation and holds

hearings

Demanders of Public

Policy (e.g., the utility,

industrial consumers,

environmental

activists, etc.) lobby

and express their

views in hearings

Potential

intervention from

other Suppliers of

Public Policy

PUCs make a

decision regarding

the firm’s rate-of-

return (increase,

decrease or no

change)