Art review of Pol Bury: Instants donnés

Transcript of Art review of Pol Bury: Instants donnés

Pol Bury : Instants donnés

Espace Fondation EDF

6, rue Récamier 75007 Paris

April 28 - August 23, 2015

Published at Hyperallergic as Kinetic Sculpture that Moves at a Snail-like Pace

http://hyperallergic.com/229750/kinetic-sculpture-that-moves-at-a-snail-like-pace/

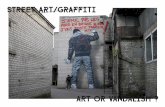

Pol Bury in front of his work “4087 cylindres érectiles” (1972) © Centre Pompidou, MNAM/CCI

I particularly admire Pol Bury’s (1922–2005) shimmering kinetic work when he puts technology

in the service of European slowness. At Espace Fondation EDF, curator Daniel Marchesseau and

Velma Bury, the artist’s wife, have assembled an exceptional historic presentation (free to the

public) of Bury’s decelerate and whimsical art. The poetic movements that Bury assigned to his

stirring sculptures and wall pieces are repeatedly gradual and/or periodical. There is an

imperceptible quivering action in some of them that does not immediately register with most

viewers. This user unfriendly aspect represents Bury’s unique pursuit of a dynamism in art that

was initiated by the Cubo-Futurists and intensified by Naum Gabo, Anton Pevsner, László

Moholy-Nagy, Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and then Nicolas Schöffer and Takis, et al. Like Bury,

they were concerned with opening up the static three-dimensional sculptural form to a fourth

dimension of time and motion that provokes in the psyche a temporary de-materialization of the

art object.

Such wooly and wiggy things went on in the search for a total art back in the 1960s, as developed

out of spectator participation, beginning with Op Art: that hard-edge geometrical movement

largely inspired by various optical experiments of Marcel Duchamp. Jesus-Rafael Soto, Bridget

Riley, the GRAV group, Yayoi Kusama, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Yaacov Agam, Marian Zazeela and

Victor Vasarely (among others) are key Op references here. Op Art implied the kinetic in that it

called attention to the spectator’s individual, constructive and changing perceptions, and thus

called upon the attitude of the spectator to transfer the creative act increasingly upon herself. But

Kinetic Art also played an important part in pioneering the unambiguous use of optical movement

and in fashioning links between science, technology and art relating to the notion of the

environment.

Simply stated, the term kinetic means the study of the relationship between moving bodies. Hence

the term Kinetic Art is usually used to describe either three-dimensional mobiles or constructions

that move in either foreordained or unplanned ways. With Op Art (which is kinetic in that Op

situations employ optical illusion that effect an appearance of motion) and Kinetic Art (both

conceptual descendants of the shifting perceptions initiated in 20th century painting with

Impressionism, Cubism and Futurism), the artwork under consideration is no longer merely a

categorical system but increasingly an invocation to raucous perception. Thus the element of

personal choice and physical motion by the beholder is emphasized, resulting in a decline in the

art object’s sequestered, fetishistic standing as an objet d'art.

This trend is very well exemplified by the work of the Belgium Pol Bury and makes him useful in

considering subject/object polarity in terms of artistic experience. That is the theoretical premise,

at least, in which I will briefly consider this show.

Given the period-piece nature of the exhibition, I found it stylistically engaging albeit retro in

look. It recalled for me my ideas of the early Paris 60’s and the shinny futuristic space age

designs of Paco Rabanne that also involved the use of moving metallic discs.

“Sphère avec deux plans sur un cube” (1975) Acier inoxydable, aimant, 40 x 20 x 20 cm ©

Collection privée Courtesy Galerie Patrick Derom, Bruxelles

In truth, Bury’s rather clunky looking sculptures are far more interesting to experience than look

at (particularly in reproduction), as their escargot-like pace of movement lends a cool Zenish

atmosphere to a room. Slow, seemingly random, trembling movements of individual parts of a

group of forms are leisurely tickled by purring hidden motors. Particularly funny and gratifying is

his erection series where small wooden rod-forms every-so-often twitch a bit upwards and then

pathetically wilt back down, such as in the huge “4087 cylindres érectiles” (1972) and the

smaller, earlier “Rérectile” (1964).

“4087 cylindres érectiles” (1972) 250 x 710 x 45 cm Oeuvre en 3 dimensions, installation mixte

Cylindres articulés, chêne verni sur panneaux de bois, moteurs © Centre Pompidou, MNAM/CCI,

Paris

Installation view of “4087 cylindres érectiles” (1972) 250 x 710 x 45 cm Oeuvre en 3 dimensions,

installation mixte Cylindres articulés, chêne verni sur panneaux de bois, moteurs © Centre

Pompidou, MNAM/CCI, Paris, photo Joseph Nechvatal

“Plans mobiles” (circa 1953) 110 x 150 cm, Tiges de fer et panneaux masonite peints, ©

Collection privée

“Multiplans” (1957) 117 x 65.5 x 16.2 cm, 10 lames métalliques et fond Isorel, peint à l’huile en

bleu, bleu pâle, jaune, orange, rouge, vert, cadre et caisse métal noir, courrole, moteur ©

Collection Letaillieur

“25 oeufs sur un plateau” (1970) laiton poli, moteur, aimants, 50 x 50 x 20 cm © Collection

privée

A sense of hypnotic connection between the human psyche and the surrounding environment is a

fair description of the alert experience of sharing a room with these pieces. At times one senses a

breeze in the room that does not exist. I think it is appropriate to think of his work as a means of

transforming static perspective vision into luminous motion study.

“2270 points blanc sur un losange – Entité” (1965) Relief tactile, moteur, bois, nylon et acrylique,

© Musée de Grenoble, photo Joseph Nechvatal

“1815 et 2185 points blanc” (1967) Relief tactile, moteur, bois, nylon et acrylique, © Collection

du MAC VAL, Musée d’Art contemporian du Val-de-Marne, photo Joseph Nechvatal

Also granting an unsettling effect with regard to the spectator’s ocular aptitude are Bury’s wiggly

hairy wall pieces, such as “2270 points blanc sur un losange – Entité” (1965) and “1815 et 2185

points blanc” (1967). They consist of a textured wooden picture plane with protruding bunches of

grass/hair-like tendrils, again powered by a veiled motor. Their unexpected and irregular slow

motion gives them an element of dilated time where surprise and chance seem to emerge. That

quality seems to me to be a legacy of the Surrealists. Whimsical humor and delight permeates the

work’s gentle visual poetry, which makes Bury a key figure in the middle of the art-tech

intellectual narration – a narration that increasingly defines artistic achievement outside market

considerations/manipulations in the beginning of the 21st century.

His plucky musical instruments, like “17 cordes horizontales et cylinders” (1973) and “12 et 13

cordes vertcales et leur cylinder” (1973) create an unexpected minimal music through the

grinding, scraping, rattling of the hidden mechanism. This mechanical murmur, along with the

plucking of the strings, creates a tiny eccentric symphony of impromptu notes and noise.

“17 cordes horizontales et cylinders” (1973) Bois, 125 x 49 x 18,5 cm © Collection Sylvie

Baltazart-Eon

“12 et 13 cordes verticales et leur cylinder” (1973) Bois et nylon, 141 x 50 x 25 cm © Collection

Sylvie Baltazart-Eon 20- 17 cordes horizontales et cylindres, 1973, Bois, 125 x 49 x 18,5 cm ©

Collection Sylvie Baltazart-Eon

“43 éléments se faisant face” (1968), Collection privée, Courtesy Galerie Patrick Derom,

Bruxelles, photo by Joseph Nechvatal

Also on view are a number of fountains and models where Bury incorporated water as an

additional ingredient of movement in his sculpture. The movement that he assigned to these

sculptures was also rather slow, often not immediately registering with the viewer.

Generally, Bury’s work is not as technically sophisticated or flashy as Nicolas Schöffer’s, (who

also had an enlightening retrospective at Espace Fondation EDF a few years ago) for example,

Schöffer’s “CYSP 1” (1956), a work considered the first cybernetic sculpture in art history made

with electronic computations developed by the Philips Company. “CYSP 1” is set on a base

mounted on four rollers, which contains the mechanism and the electronic brain. Photoelectric

cells and a microphone built into the sculpture catch all the variations in the fields of color, light

intensity and sound intensity. All these changes occasion reactions on the part of the sculpture.

Colored lights bounce off revolving polished metal towers - casting ever-changing lights and

shadows onto huge wall-screens and into our eyes. Oh la la! Party room!

By contrast, Bury’s polished metal pieces, like “Grand cube miroir avec demi-sphères” (1970),

have only a bit of this heavy metal razzle dazzle. Generally speaking, his slower, more modest,

post-Surrealist displays of technological prowess protect the work from falling into the special

effects category of spectacle that sometimes swallows up Schöffer’s grander projects.

“Grand cube miroir avec demi-sphères” (1970) private collection, photo Joseph Nechvatal

The perverse dreaminess of Surrealist taste detected in his work is traceable to young Bury’s first

influence, meeting René Magritte, who inspired him to start painting in Surrealist style. But Bury

then abandoned painting in 1952 after encountering the sculpture of Alexander Calder. Calder’s

mobiles, in particular, made a powerful impression, one that we can see in Bury’s first kinetic

pieces from the 1950s: weathervane-like sculptures that were inter-activated by viewer-

participants. In 1955 this interactive work led him to being asked to participate in the historical

exhibition Le Movement that was organized in Paris by Denise René and Pontus Hulten.

Thereafter, Bury dropped interactivity for the motorized and chose to live permanently in Paris

with significant time spent in the United States between 1966 and 1971, particularly in Manhattan

and Berkeley.

Bury has said “Speed limits space, slowness increases it.” Hense perhaps one central benefit of

this show of eighty works might be in its allowing us to better position Bury in a certain art-tech

artist-engineer intellectual geography - one that is far from evident or exhausted.

Joseph Nechvatal