Anti-Queer Morality in Uganda

Transcript of Anti-Queer Morality in Uganda

Anti-Queer Morality inUganda

An interdisciplinary study on the increasinganti-queer morality in Uganda.

Authors:Fleur van der Laan (3683184)

Religious Studies&

Eeke van der Wal (3588876)Human Geography

May 2014

“Boundaries (…) exist to be transgressed, they arethere to facilitate crossings, not to frustrate them.It is not (…) in those places whose exact frontiershave already been defined for us, but in the regions

of uncertainty where definitions have yet to belocated, that we must find our place” (Miller, 1992).

2

Anti-Queer Morality inUganda

Capstone Project Liberal Arts and SciencesAn Interdisciplinary Study

May 2014

Supervisor: Dr. R. van der Lecq

Disciplinary Referent Religious Studies: Prof. Dr. M.T.Frederiks

Disciplinary Referent Human Geography: Dr. A.C.M vanWesten

3

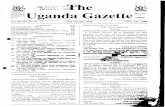

© The images are by ‘Hollandse Hoogte’ and depicts a demonstration againsthomosexuals in the city Jinja in Uganda.

The picture is derived from: Vermeulen, M. Homohaat is een westers exportproduct. De Correspondent. Februari 13th, 2014. Retrieved on March 27th on:<https://decorrespondent.nl/727/homohaat-is-een-westers-exportproduct/

38821876335-ad184973>

4

Content 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................- 6 -

PART I – Situating the Problem.................................- 9 -

2. The Anti-Queer Morality.........................................................................................- 10 -

2.1 Anti-Queer Animus versus Homophobia....................- 10 -

2.2 Anti-queer Animus and Morality.........................- 11 -

2.3 Christianity and the Anti-Queer Morality...............- 12 -

2.4 Restrictions of the Concept............................- 14 -

3. The Case of Uganda................................................................................................- 16 -

3.1 Context of the Republic of Uganda......................- 16 -

3.2 Perception on homosexuality in Uganda..................- 18 -

PART II – Anti-Queer Morality in a Context of Globalisation...- 19 -

4. Globalisation as a Framework...............................................................................- 20 -

4.1 Globalisation of Cultures..............................- 20 -

4.2 The Notion of Cultural Imperialism.....................- 21 -

5. Anti-Queer Animus as ‘Western’ export-product...................................................- 23 -

5.1 Colonisation of Uganda.................................- 23 -

5.2 Contemporary Cultural Imperialism through American

Fundamentalism.............................................- 25 -

5.3 Several Concluding Remarks.............................- 28 -

6. Anti-Queer Animus as a reaction to the ‘West’......................................................- 30 -

6.1 A Reaction on the Manifestations of Cultural Imperialism - 30

-

6.2 Religion versus Liberalisation.........................- 33 -

5

PART III – Local Explanations for an Anti-Queer Morality in Uganda -

36 -

7. A Religious Breeding Ground..................................................................................- 37 -

71. Local Religion.........................................- 37 -

7.2 Religion and Politics in Uganda........................- 39 -

8. A Socio-Cultural Breeding Ground..........................................................................- 41 -

8.1 Public Morality versus Private Sexuality...............- 41 -

8.2 Construction of Discourses through Government Institutions

and Media..................................................- 43 -

8.3 Local Discourses of Material Exchange..................- 44 -

8.4 The Image of National Unity............................- 45 -

PART IV – Conclusion and Reflection...........................- 47 -

9. Conclusion...............................................................................................................- 48 -

10. Reflection...............................................................................................................- 51 -

List of References............................................- 52 -

6

1. Introduction On the twenty-fourth of February 2014 the Ugandan president Yoweri

Kaguta Museveni signed an Anti-Homosexuality Act that prohibits and

criminalizes any form of relations between persons of the same sex.

The Bill includes, the possibility of a death sentence for those who

are ‘aggravated homosexuals,’ which refers to homosexuals that have

HIV/AIDS, children or a job in leadership (Anti-Homosexuality Act,

2014; 4). The Bill is, therefore, commonly referred to as the ‘Kill-

the-Gays Bill’. These increasing anti-gay attitudes are

simultaneously emerging in other African countries. Nigeria and

Zambia for instance, are currently also legislating anti-gay acts.

Nigeria passed a ban on same-sex relationships last January, known

as the ‘Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act’ (Gladstone, 2014).

It seems paradoxical that while we in the ‘West’ are

propagating the emancipation of gay rights another substantial part

of the world is propagating the opposite. In ‘Western’ media Uganda

seems to be at the forefront of this anti-gay movement because it is

the first country to actually illegalize homosexuality. Therefore

this study will focus on the increasing anti-gay perceptions, which

we term the ‘anti-queer morality’1, in Uganda. This study addresses

the following question: How can the increasing anti-queer morality in Uganda be

explained?

This study was conducted through interdisciplinary research

methods. In this study disciplinary insights are included which

eventually lead to an integrated answer to the main question. This

integration of different disciplinary insights will provide a more

comprehensive understanding of the issue. Repko (2008; 84)

1 In chapter 2 we will provide an elaborate definition and justification of the concept of anti-queer morality.

7

identifies four criteria that justify the use of an

interdisciplinary research approach:

The problem or question is complex.

Important insights or theories of the problem are offered by

two or more disciplines.

No single discipline has been able to address the problem

comprehensively or resolve it.

The problem is an unresolved societal need or issue.

The issue addressed in this study is considered complex due to the

many different components (e.g. origin, manifestation etc.) of

increasing homophobia that are studied by different disciplines.

Furthermore, different disciplinary insights and theories have

addressed this issue and none of the single disciplines has been

able to address the issue comprehensively. The issue thus remains an

unresolved societal issue, especially interesting in the light of

the contemporary diverging perceptions on gay rights in different

places in the world. The integration of different disciplinary

insights can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of this

phenomenon (Repko, 2012; 85).

Disciplines that can provide useful insights are Religious

Studies, Human Geography, Cultural Anthropology, Postcolonial

Studies, Conflict Studies but also Law and Political Studies. These

disciplines all address different aspects of homophobia: the origin

of homophobia, the complexity of cultural and religious differences

and anti-gay perceptions, the geographical distribution of

perceptions, the complex postcolonial context in which the

phenomenon occurs and the judicial and political manifestations of

homophobia. The interdisciplinary research for this paper has,

however, been conducted solely through two 'disciplines': Human

8

Geography and Religious Studies. Both studies have provided significant

and relevant insights on the issue of gay rights.

Human Geography is a social science that studies the world, its

peoples, communities and cultures from a geographical perspective,

thus emphasizing the relations with time, space and place. This

discipline has many different fields of which especially Cultural

Geography appears to be relevant for this study on increasing

homophobia. Cultural Geography studies the cultural products and

norms, including lingual, historical, religious, economic and

political phenomena and links these to time and space (Tomlinson,

2003; 273). This sub discipline is relevant for the issue as

cultural norms and values concerning homosexuality, their history

and contemporary manifestation in Uganda play an important role in

the increasing anti-gay perceptions in Uganda. Furthermore,

historical, economic, political and social trends influence

development of and the position of countries (Potter et. al., 2008;

7). These factors shall also be included in the analysis of the

upcoming anti-queer perception in Uganda. Especially theories on

globalisation have contributed to this paper, as they offer new

understandings of the contemporary upswing of homophobia due to

dynamics of time and space.

Religious Studies is a multi-disciplinary approach to the

secular study of religious beliefs, -institutions and -behaviours.

This field of studies is used to describe, compare, interpret or

even explain religions. It is relevant because of the high level of

religiosity in Uganda and the increasing influence that religion

(especially Christianity) plays in local politics. Understanding the

influence of Christianity on the Ugandan society is an integral part

to understanding the anti-gay regulations that arose in recent

times. Besides that religious believers have been at the forefront

of formulating anti-gay discourses for a long time, justifying these

9

condemnations with references to various scriptures. Through the

study of world Christianity, a sub-discipline in Religious Studies,

a wide range of issues like politics, culture, migration and

globalisation can be studied that either shape or transform

Christian identities, both individual and collective, and practices

in the changing modern world (Irvin, 2008; 1). In this paper

Religious Studies, thus, provides the bridging capacities between

religion, culture, anti-gay discourses, politics and identities.

In order to answer the research question thoroughly and

comprehensively we have formulated several sub-questions that will

each be addressed in a different part or chapter:

1. What is an anti-queer morality? (chapter 2)

2. What is the current situation in Uganda? (chapter 3)

3. How do current global trends relate to the current upsurge of

anti-queer morality in Uganda? (Part II)

4. How do local factors in Uganda influence the current upsurge of

the anti-queer morality? (Part III)

The answers to these sub-questions will provide insights on the

phenomenon of the ‘anti-queer morality’ in Uganda. We will first

address the origin of such ‘anti-queer’ attitudes by introducing the

concept of ‘anti-queer morality’ in chapter 2. Both disciplines have

provided insights on anti-queer perceptions and on morality. In

chapter 3 we will elaborate on Uganda’s current situation, including

the economic, political, cultural and religious character.

Furthermore this chapter describes how the anti-homosexuality

perception has manifested itself in Uganda. In part II we will

provide explanations through the lens of globalisation (chapter 4).

Globalisation is currently a popular explanation for the upswing of

anti-gay attitudes in African countries, especially highlighted by

the media. Many scholars have argued that anti-gay attitudes were

10

‘brought’ to Uganda during the colonial rule. Another explanation is

that religious aid is responsible for the upsurge of homophobic

ideas in African countries (Seitz-Wald, 2014) (chapter 5). Yet,

other scholars see the ‘anti-queer’ perceptions as a reaction to

‘Western’ liberalisation of morals (chapter 6). Thereafter, we

address the local factors that influence the current upsurge of

anti-queer perceptions in Uganda in part III, both the religious

(chapter 7) and socio-cultural (chapter 8) factors. Finally, the

concluding chapters (9 and 10) integrate the different trends

addressed and reflect on the process of this interdisciplinary

study.

The relevance of this study lies both in the societal- and in

its scientific importance. The scientific relevance is to obtain a

better understanding of what an ‘anti-queer morality’ is, how it is

manifested and why it is present in certain areas and less in

others. The social relevance lies in the creation of a mutual social

understanding of the issue of same-sex sexuality. The gap between

pro-gay and anti-gay is a great a source of conflict, not just in

Uganda but all over the world. A mutual and more comprehensive

understanding can hopefully foster the current dialog on same-sex

sexuality. Our aim is thus to provide a more comprehensive

understanding of the phenomenon as a basis for further study.

11

2. The Anti-Queer Morality

Our study focuses on the ‘anti-queer morality’ that is increasingly

present in Uganda. This concept of ‘anti-queer morality’, however,

needs to be elaborated on before discussing the possible

explanations for this phenomenon. This chapter firstly elaborates on

the notion of the ‘anti-queer animus’ as described by the social

anthropologist Ryan Thoreson (2014; 25) in comparison to the more

commonly used term ‘homophobia’. Furthermore, we will elucidate our

preference for the former concept. Subsequently, this chapter will

link the notion of an ‘anti-queer animus’ to the concept of

morality. We will then define the concept of ‘anti-queer morality’

and argue that this morality is greatly determined by the values and

norms that nations, communities and individuals uphold. Finally,

this chapters will link the concept of ‘anti-queer morality’ to

religion, as religion tremendously influences the norms and values,

thus morals, upheld by society (Bloom, 2012).

2.1 Anti-Queer Animus versus HomophobiaThe most common concept used to describe non-proscribed prejudice

and negative, fearful or even hostile feelings towards homosexuals

is the term ‘homophobia’ (Schartz & Lindley, 2009; 149). We,

however, argue below that framing Africa or Uganda as ‘homophobic’

oversimplifies the problem of anti-homosexual perception and

attitudes. Therefore, we choose to uphold Thoreson’s (2014; 25) more

inclusive notion of the ‘anti-queer animus’.

Several arguments support the notion that the concept of

‘homophobia’ is restrictive. According to Thoreson (2014; 24-25) the

term homophobia leaves little room for nuances. The word ‘phobia’

14

suggests that ‘homophobic’ expressions are always rooted in fear. It

thus implies that such negative feelings regarding homosexuality are

always the result of fear. Thoreson (2014; 25) suggests that we

reject this monolithic concept of homophobia in sub Saharan Africa.

Furthermore, the global development specialist Marc Epprecht (2012)

indicates that the notion of ‘homophobia’ “bolsters racist

dismissals of the Global South as inherently hostile to queers”

(2012; 226). The concept of ‘homophobia’ thus implies that Africa is

backward in comparison to Europe and America.

A final argument made by the anthropologist Don Kulick (2009;

23) is that the notion of ‘homophobia’ places the anti-homosexual

attitudes within the psyche. We, however, adhere to the idea that

socio-structural dynamics can cause ‘homophobic’ prejudice and

resentment. We thus imply that the concept ‘homophobia’ is too

restrictive for this study, as we attempt to map social and

religious dynamics on anti-homosexual perception and behaviour.

Furthermore we do not think of anti-homosexual expressions as solely

derived from fear and psyche.

Instead we have chosen to adhere to Thoreson’s (2014; 25)

concept of the ‘anti-queer animus’. We prefer this concept, firstly

because it reflects more on the social construct of resentment and

behaviour towards homosexuals. The concept of ‘anti-queer animus’

entails also “anger, hatred, bias, ignorance, jealousy or other

sources of antipathy toward queer persons” (Thoreson, 2014; 25).

Secondly, the use of the concept ‘anti-queer animus’ instead of

‘homophobia’ prevents the narrow focus solely on homosexuals (which

refers to men who have sex with men) and allows the inclusion of

lesbians, bisexuals, transsexuals, and intersexuals, commonly known

as the LGBTI community (Thoreson, 2014; 25). Thirdly, the use of the

concept ‘anti-queer animus’ provides the opportunity to include the

consideration of other forms of sexual prejudice or hostility that

15

are based on gender, class, power or other forms of difference and

belonging (Fone, 2000; 6-7).

2.2 Anti-queer Animus and MoralityAs we have explained above, we uphold Thoreson’s (2014; 25) notion

of the ‘anti-queer animus’. This notion indicates that the anti-

queer perception is not merely based on fear, anger or hatred but

includes social aspects such as group-pressure, social control or

keeping-face and even economic reasons. The word ‘animus’ in the

concept, however, indicates a hostile attitude towards queerness. We

argue below that this ‘animus’ or perception of homosexuality and

queerness greatly arises from social and individual moral norms and

values.

Morality is a concept that can be defined as the codes of

conduct to which a society or individual adheres. It thus determines

what a society of individual perceives as right or wrong, normal or

abnormal (Gert, 2011). We adhere to a social constructivist

definition, indicating that morality is a normative concept,

constructed within certain social settings due to social interaction

and social processes of giving meaning (Chapouthier, 2004; 180). We

also adhere to the more geographical notion that both the ‘moral’

and ‘immoral’ become defined, practiced and reproduced in plural

ways across time and space (Lee & Smith, 2004a; 7). Additionally,

within this perception, we claim that one can have multiple morals

at the same time inspired by social, cultural, religious or

political rules of conduct (Gert, 2011).

As both disciplines refer to concepts of ‘morality’, ‘moral

panic’ and ‘moral decline’ in order to explain anti-queer attitudes

(see Valentine et. al., 2013; Sadgrove et. al., 2012; van Klinken,

2010; Shah, 2003; amongst others) and because morals greatly

determine what is perceived as right and wrong within society, we

16

assume that morality underlies the perception of society towards

homosexuals and queers. We thus find that an anti-queer perception

is greatly determined by societal as well as individual morals.

Consequently, we propose a more comprehensive concept that can

replace ‘anti-queer animus’ in this thesis, namely the ‘anti-queer

morality’2. The concept of ‘anti-queer animus’ then refers to a

hostile attitude towards queerness while the ‘anti-queer morality’

henceforth indicates the underlying set of norms and values (that

determine ‘wrongness’ and ‘rightness’ in society) that create such

an animus towards queers.

Summarizing, we define ‘anti-queer morality’ as both an

individual and social morality that perceives homosexual acts,

including other sexual activities that deviate from the norm, as

wrong and therefore immoral. The anti-queer morality thus imposes

heterosexual norms and values that stress the importance of

heteronormativity, along with other cultural values such as family

or reproduction. Furthermore, this concept indicates the societal or

individual impulse to actively pursuit those norms and values. This

pursuit can take on hostile attitudes, but hostility is no longer

inherent to the anti-queer reactions.

2.3 Christianity and the Anti-Queer MoralityMorality is determined by a multiple and complex construct

influenced by culture, politics, social interaction, money and

religion. Many disciplines have offered insights on what morality

is. Also Religious Studies has provided many insights on morality,

as religion is often regarded as underlying moral norms and values

(Gert, 2011). Furthermore religion is often understood to underlie

2 We have used the common ground technique of redefinition as proposed by Repko (2012) to create this concept of the ‘anti-queer morality’. The technique of redefinition entails modifying or redefining concepts to bring out a common meaning (Repko 2012, 336).

17

anti-queer perceptions (Bloom, 2012). We thus argue that the

construction of an anti-queer morality is likely to have been

influenced greatly by religion3.

Religion can be given meaning in many different forms by

different people. According to the psychologist William James (1902)

religion is a transcendent or mystical experience. The

anthropologist Edward Tylor (1871), however, claims that religion is

a set of supernatural beliefs. A third conception sees religion as

solely a social activity (Bloom, 2012; 183-184). Whichever view of

religion is adhered to, all scholars mentioned above attest to the

fact that religion influences personal behaviour. With regard to the

concept of morality the debates on whether religion influences

behaviour positively or negatively have, literally, been going on

for ages (Bloom, 2012; 181).

According to psychologist Paul Bloom, this dualism in the

perceived effects of religion can also be seen in the study of

religion and behaviour. There are traditions in social psychology

that focus on the relationship between religion and prejudice, but

also on the relationship between religion and altruism or generosity

(Bloom, 2012; 183). One can therefore conclude that there is a

connection between religion and (im)moral behaviour.

Although all rational persons have their own morality,

individual of religious beliefs, religion has greatly effected and

influenced moral perceptions (Gert, 2011). According to Bloom there

are three reasons why religion and morality are likely to be linked.

Firstly, religion makes explicit moral claims that are accepted by

followers because they believe in religious texts. “Through holy

texts and the proclamations of authority figures, religions make

moral claims. [...] People believe these claims because, implicitly

or explicitly, they trust the sources. They accept them on faith” 3 In this study we address mainly the Christian religion because it is the largest religion in Uganda (as elaborated on in Chapter 3).

18

(Bloom, 2012;184). Secondly, religion emphasizes certain aspects of

morality that they perceive as important, like family or sexuality.

Herewith, you are ‘good Christian’ and therefore a good person if

you follow these moral rules of conduct. Religious values thus

greatly influence and determine moral perceptions (Bloom, 2012; 184-

185). Finally, it can be argued that religion has a more general

effect which could form moral perceptions because it stresses

feelings such as compassion, empathy, caring and love for one’s

neighbours. Consequently, this might also increase prejudice and

intolerance towards those that are perceived as ‘outside’ of the

community (Bloom, 2012; 185).

The concept of the ‘biblical creation narratives’ as termed by

Massiwa R. Gunda (2011) affirms Bloom’s first argument. According to

Gunda these biblical narration narratives are used in order to

justify moral claims. In the case of anti-queer morality biblical

passages are addressed as sources of authority to prove that

homosexuality is sinful (Gunda, 2011; 93). These narratives are

based on the books of Genesis and are said to interpret Gods

creation of both a man and a woman as the proof that men and women

should be together. This anti-homosexuality perception is commonly

phrased as “It’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve!” referring to

Gods initial creation of Eve (female and woman) and Adam (male and

man).

With the aid of the Bible these gender distinctions are

sacralised and therewith same-sex relationships are demonised.

Homosexuality is thus perceived as going against God’s divine

intentions and therefore as unnatural and immoral. Theology scholar

and former priest Edward E. Malloy (1981) argues that homosexuality

is seen as immoral for several reasons. Firstly, it goes against the

procreative purpose of sexual intercourse; this contributes to the

view of Gunda (2011). This argument implies that homosexuality is

19

often seen as an attack on the family, which is in Christian eyes

seen as the basic unit of society (Malloy, 1981). Secondly, because

homosexuality is seen as something unnatural – ‘not how God made

us’ – homosexuality is often attributed to mental health issues ,

upbringing or personal choice (Brooke, 1993; 77).

For the greater part of Christian people the Bible, being the

word of God, remains the ultimate source of guidance and

inspiration. The Bible holds immense authority and during

controversial discussions Christians will most of the time fall back

on the Bible to see what it says about the topic (Helminiak, 1995;

12). Several passages in the Bible are repeatedly used to authorize

the anti-queer morality, for example Leviticus 18:22: “You shall not

lie with a male as with a woman; it is an abomination” or Leviticus

20:13: “If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman,

both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put

to death; their blood shall be upon them”.

Religious scholar Allan Aubrey Boesak (2011) interprets these

passages as being about homosexual acts of ancient culture that took

on the forms of punishment or putting others in an inferior

position. However not all religious scholars agree on such anti-

queer interpretations of the bible. According to Boesak “there is no

inkling that the Bible says anything about, let alone passes

judgement on committed, loving, stable same-sex relationships”

(2011; 18). C. B. Beal (1994) in his article ‘Modern medicine,

homosexuality, and the Bible’ agrees that committed, loving gay

relationships are equally capable of fulfilling “God’s design for

creation” (1994;93). Furthermore both Beal and Boesak stress the

social context of today differs greatly from the context in which

the bible was construed. They indicate that this should be taken

into account in contemporary interpretations of biblical texts.

20

Thus, we imply that religious perceptions and interpretations

of biblical texts greatly underlie the anti-queer morality we

discuss. We, however, do not state that religious morals are per

definition the same as anti-queer morals. We find that religious

morals are diverse and subject to (collective or individual)

interpretation. We do suggest that moral codes of conduct are

influenced by religion and that certain religious interpretations

can invoke an anti-queer morality.

2.4 Restrictions of the ConceptThe concept of anti-queer morality as introduced above will be used

throughout this study. We are aware of the limitations of the

concept as we have proposed and defined it. We assume that the anti-

queer morality or anti-homosexual perception and attitudes are the

result of cultural and moral notions. We thus imply that ‘normality’

and ‘abnormality’, ‘moral’ and ‘immoral’, and ‘wrong’ and ‘right’

are socially determined. Yet, for many, sexuality is considered

innate, biologically determined and even pre-cultural, implying that

sexuality remains unaffected by social perceptions and thus culture

(Reddy, 2004; 2004). An anti-queer perception is, consequently,

considered a natural response. We have chosen to uphold a social-

constructivist perspective on anti-queer morality because it offers

opportunities for changing perception and behaviour.

Additionally our concept of anti-queer morality might be

considered incomplete or inadequately explained. Justification of

the use of an anti-queer morality might require a more elaborate

explanation and the inclusion of more psychological and

philosophical insights on morality. We, however, have chosen to

uphold this concept as we consider it more inclusive and less

biased than the previously discussed concepts of ‘homophobia’ and

‘anti-queer animus’. In this paper we will use it as defined above.

21

Finally, we make several general claims regarding the religious

influence on anti-queer morality. We are aware of the fact that not

all religious groups agree with this notion. We do, however, find it

important to stress the influence that religion has on moral

perception. We find that, though people might not practice religion,

their norms and values are still greatly influenced by and

descending from religious norms and values. We do not wish to imply

that everyone (or all Christians) is (are) in complete accordance

with the anti-queer morality as we describe it. We are aware of the

generalizing tendency that this explanation might bear.

22

3. The Case of Uganda

This chapter describes how the contemporary perception on

homosexuality and queerness has manifested itself in Uganda.

Firstly, this chapter will provide a short overview of Uganda’s

history and the religious, social and political situation. This

acquaintance with Uganda is important to later understand how and

why an anti-queer morality has manifested itself in Uganda.

Secondly, this chapter will describe the current upsurge of the

anti-queer perception and the subsequent coming into effect of the

Anti-Homosexuality Act that was signed into law by the president of

Uganda on February 24th, 2014. These recent events, as will be

elaborated on in later chapters, have great effects on the anti-

queer perceptions in Uganda.

3.1 Context of the Republic of UgandaThe Republic of Uganda is a country located in central Africa in

between Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Rwanda

and Tanzania (United Nations, 2014). Population of Uganda was 36.35

million in 2012 (Worldbank, 2013). Uganda is considered a Heavily

Indebted Poor Country and thus struggles with issues of low income,

high levels of poverty and low life expectancy (WHO, 2012). Over 40

different ethnic groups reside in Uganda. The Baganda is the largest

ethnic group present, comprising almost 17% of the population

(Marjoke, 2012).

23

Uganda has a history of colonisation by the United Kingdom. Its

current boundaries were agreed upon by Britain and Germany in 1890

and in 1894 Uganda officially became a protectorate of the British

Empire (Griffith, 1986; 209)4. During the British rule Uganda was

divided into four provinces. Upon independence in 1962 Uganda’s

provincial divisions were dropped. Only the Buganda district

remained, which subsequently became the federal state (Green, 2009;

349).

Following the independence from the British colonial rule

Uganda has experienced a decade of political and economic

instability. A military coup in 1971 led to a trajectory of violence

and mismanagement that reduced the country to a ‘failed’ state, a

state in which the government has little to no control over its

territory (Worldbank, 2013).

4 We do not want to imply that Ugandan history started with the colonisation of the Uganda by the British. However, none of the available literature connected the pre-colonial history of Uganda with the current upswing of anti-queer morality in Uganda. Therefore, we chose not to include it in the contextualisation of Uganda.

24

Figure 1: Geographical Location of Uganda (Alltravel, 2014)

This period of political and economic turmoil lasted until 1986

when the National Resistance Movement (NRA), led by Museveni, took

over power. This resulted in a period of sustained economic and

political renewal. The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Northern

Uganda has, however, waged a civil war in Uganda since 1987

(Worldbank, 2013). The establishment of the LRA is often linked to

the attacks that the NRA targeted towards the Acholi people, a

minority ethnic group in Uganda. The LRA, led by Jospeh Kony,

intended to establish a theocratic state based on the biblical Ten

Commandments and the Acholi tradition (Quinn, 2004; 8). This

guerrilla campaign deepened the poverty and diminished the economic

activity in Northern Uganda. As of 2005, the LRA was pushed out of

Uganda and there have not been any more major attacks since then

(Worldbank, 2013).

Uganda has progressed toward a multi-party democracy that holds

regular elections. Constitutional amendments were set in the

constitution of 1995. Museveni and his NRM Party won the first

multi-party elections and he had been re-elected twice since then.

Museveni’s current term has, however, been characterized by

increasing opposition and mounting parliamentary pressure over the

government. Recent cases of large-scale corruption in some

ministries indicate that governance remains a major challenge for

Uganda (Worldbank, 2013).

The main religion in Uganda is Christianity. Approximately 84%

of Uganda’s population is Christian. The Roman Catholic Church has

the largest number of adherents, followed by the Anglican Church of

Uganda. Evangelical and Pentecostal churches claim the rest of the

Christian population (Ward, 2013; 417). Consequently, Christian

religious values greatly influence societal life. Many traditional

Christian values such as family and reproduction are considered to

be important cornerstones of society (Ward, 2013; 412-413). Muslims

25

are thought to represent 12% of the population in Uganda, and these

Muslims are mainly Sunni (Ward, 2013; 417). Prior to the advent of

alien religions such as Islam and Christianity traditional

indigenous beliefs were practised to ensure that the welfare of

people were maintained at all times. Nowadays these practices are

sometimes still practiced in rural areas or blended with and

practised alongside Christianity and Islam (Ward, 2013; 411).

3.2 Perception on homosexuality in UgandaReligion is said to be greatly influential in societal life but also

in political decision making. Both the president and his wife are

known to be a dedicated born-again Anglican Christians openly

proclaiming Christian values and morals (Sadgrove, 2007; 121).

Furthermore, Uganda’s ambassador openly proclaimed to find

homosexuality “unnatural, abnormal, illegal, dangerous, and dirty”

(AFP, 2009; quoted in Thorseon, 2014; 29). This open and politically

invoked anti-queer morality and animus in Uganda can be deduced from

the Anti-Homosexuality Bill 2014.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act was first proposed in 2009 by the

Member of Parliament David Bahati. It prescribed life in prison for

anyone who “touches another person with the intention of committing

the act of homosexuality” and the death penalty for aggravated

homosexuals (Thoreson, 2014; 28). It also permitted imprisonment for

any person who openly supports and/or promoted homosexuality or

fails to report such violations within 24 hours (Anti-Homosexuality Act,

2014; 9-10). On the 20th of December 2013 the parliament passed on an

amended version of the Anti-Homosexuality Act. It was signed into

law by Museveni on the 24th of February 2014.

There has been strong national and international opposition to

the bill. The commencement of this bill has shaped new socio-

political realities and created a strong LGBTI movement in Uganda.

These groups have created a diverse network of organisations often

26

linking to international Human Rights organisations. The Human

Rights Movement indicates that this bill violates the Human Rights

Law (HRW, 2013). Furthermore the LGBTI movement has allied with

journalists to obtain (international) support (Thoreson, 2014; 30).

Contradictory to the (international) efforts we have only seen an

increase of violence against and discrimination of the LGBTI

community in Uganda.

27

4. Globalisation as a Framework

The perceived upsurge of the anti-queer morality has not solely

occurred in Uganda. This trend has been perceived in many countries

over the world and seems plausible in a context of increasing and

intensifying global political, economic social, media and other

forms of interaction. Development specialist Ankie Hoogvelt (2001;

124) states that intensified global relations link distant

localities and therefore local events are constantly influenced by

events elsewhere. This chapter thus attempts to explicate global

interactions and recognized trends that are currently depicted in

scientific literature and thus provide a in which the current

upsurge of the anti-queer morality in Uganda can be explained.

Firstly, this chapter elaborates on different perceptions on

the concept of globalisation, focussing specifically on cultural

globalisation. Secondly, this chapter explains the implied and

experienced hegemonic character of cultural globalisation and

subsequently the notion of cultural imperialism.

4.1 Globalisation of CulturesGlobalisation in its most general definition refers to the

interaction influences that different localities have onto each

other. More specifically globalisation can refer to the

interconnection and influence of economics, politics, culture,

religion, biology and almost any other transmissible subject

(Hoogvelt, 2001; 120-121). Literature has indicated that different

trends of globalisation are considered important regarding the

upsurge of the anti-queer morality in Uganda. Culture, politics and

Human Rights strongly influence the anti-queer morality. As we

31

perceive the anti-queer morality mainly as a cultural and religious

manifestation (see Chapter 2) we choose to focus mainly on theories

of cultural globalisation.

From a geographical perspective cultural globalisation

addresses the cultural constructs within certain time and space

constraints (Flint & Taylor, 2007; 5). Cultural norms and values are

considered important factors underlying morality and thus anti-queer

morality (as elaborated on in Chapter 2). Therefore, we consider the

globalisation of cultural norms and values important for this study.

They create a framework in which the transmissibility of morals,

such as the anti-queer morality, can be elucidated. The notion of

the transmissibility of morals is depicted by several Religious and

Geography scholars. Human geographer Valentine (et. al., 2013; 165)

indicates that in the light of globalisation, moral values, or

normative standards, are expected to transcend specific contexts.

There are two dominant perceptions of globalisation of the

cultural sphere according to the Cultural Sociologist John Tomlinson

(2003; 269). The first trend describes the notion of destruction of

cultural identities and the creation of a more ‘westernized’ and

‘homogenized’ world. This trend suggests that the western forms of

lifestyle spread across the world and that there is an increasing

convergence of cultures and cultural norms all over the world

(Potter et. al., 2008; 129). It thus implies a certain hegemonic

character of western (mainly American and European) cultures over

others.

The second, and according to Tomlinson (2003) the more

plausible, trend is that of heterogenization: the diversification of

cultures. According to this perception cultures become more diverse

as a consequence of intensified global interaction (Tomlinson, 2003;

275). According to the human geographer Potter (et. al., 2008; 178)

cultural anthropologists have always characterised culture through

32

hybridisation, difference, rupture and clashes. Differences between

and within cultures have always existed and interaction between

cultures have created ‘hybridised’ forms of cultures, resulting in

more diversity of cultures within specific localities.

The social scientist Castells (2000; 7) gives an even more

complex definition of cultural globalisation. He indicates that

cultures are created due to the consolidation of a ‘shared meaning’

that manifests through social practices in a social time and space

constraint. He thus indicates that cultural meaning is not created

within an existing cultural realm and then transmitted elsewhere.

Instead, he states that interaction between people consolidate

meaning and thus create a cultural realm. This perception of culture

implies an unfixed, fluid and changing character of culture.

Concerning our research subject of the anti-queer morality we

will provide different explanations that relate to these different,

but complementary, visions of cultural globalisation. Foreign

‘invasion’, influence and/or interaction has dislocated certain

traditional cultures.

Therefore, we do uphold the notion of Potter et. al. (2008; 163)

that globalisation has proven to be profoundly unsettling for

cultural identities, morals, norms and values but also the

identities of individuals.

4.2 The Notion of Cultural ImperialismIn social and cultural studies cultural imperialism mainly refers to

the influencing of cultures by the westernized, homogenized and

consumption driven culture (Tomlinson, 2003; 269). The concept of

cultural imperialism thus assumes that previously homogenous and

‘authentic’ cultures are imposed, subverted or corrupted by

‘foreign’ influences (Morley & Robins, 1995; 7). It is important to

note that cultural imperialism implies a ‘western’ hegemony of

33

cultural practices. This notion insinuates that the dissemination of

cultural values and practices are controlled and influenced by

western standards (Gregory et. al., 2009; 327).

In their book Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and

Cultural Boundaries Morely & Robins (1995; 7) explain that cultural

imperialism can occur through many different means, such as actual

encounters but also the increasing reach and influence of media and

social media. A result of cultural imperialism is that different

cultures become increasingly similar due to dominance of certain -

‘western’ – cultural norms and values (cultural homogenisation)

(Tomlinson, 2003; 269).

There is much criticism on the concept of cultural

homogenisation as elaborated on above. The notion of

heterogenisation and Castell’s (2000) idea of consolidation of a

‘shared meaning’ through interaction, are generally much more

accepted in Human Geography.

Nevertheless, the notion of cultural imperialism is still

upheld by many scholars. Firstly, the ‘West’ is still considered

more capable of exercising power on peripheral countries, mainly due

to their economic resources and strong political institutions.

Consequently, ‘peripheral’ countries still are more dependent on the

‘West’ than vice versa, reinforcing the perception of the

imperializing ‘West’.

Although the ‘West’ has attempted to improve their relations

with peripheral countries in a postcolonial era, the notion of

cultural imperialism indicates that these relations are not equal.

Western perceptions still prevail, also in many international

agreements such as the Human Rights. The notion of Africa being

‘backward’, though not formally recognized, still exists. Also, it

is still often implied by (western) scholars that Africa needs to

develop and modernize according the ‘Western’ standards in order to

34

become successful. As Lee & Smith (2004b; 13) state: “it is [still]

frequently assumed that the ‘underdeveloped’ countries are impeded

by their own ways of life, and that they thus need to ‘modernize’ or

‘Westernize’”.

An alternative perspective on imperialism is offered by Hardt &

Negri (2004). They argue that it is not merely states that dominate

or imperialize other states. Multinationals, (governance)

institutions and media are increasingly obtaining hegemonic

influences. It is likely that such institutions therefore also

influence cultural identities and social life locally.

Thus, the concept of cultural imperialism is multifaceted,

complex and perhaps incomplete. Yet, according to our view it is

important with regard to the issue of increasing anti-queer

morality. Valentine et. al. (2013; 165) indicate that also

culturally determined moral values are likely to transcend from the

‘West’ to other places. Globalisation and cultural imperialism thus

offer a framework in which current flows of anti-queer morality,

that we will elaborate on in the subsequent chapters, can be

understood.

35

5. Anti-Queer Animus as ‘Western’

export-productA common explanation of the increasing anti-queer perception in many

African countries, including Uganda, is that anti-queer perceptions

are ‘Western’ cultural phenomena that are exported through means of

cultural imperialism. This is currently a popular explanation of

current anti-queer tendencies that is especially explicated in

Western as well as Ugandan media. This chapter elaborates on two

perceptions of the anti-queer morality as a ‘Western’ export product

through the lens of cultural imperialism. Firstly, this perception

draws on the history of colonialism in Uganda during which western

cultural morals are said to be ‘transported’ mainly from the

colonizing countries (the ‘West’) to the colonized countries (the

‘rest’) (Drucker, 1993; 13-15). Secondly, this explanation draws on

the current popularity of the notion that American evangelicals

greatly and actively influence the perception on same-sex sexuality

of the Ugandan population (Amanpour, 2014).

5.1 Colonisation of UgandaOne of the most visible forms of globalisation and imperialism is

that of colonisation. Colonisation is the obtaining of control or

governing of a nation, which subsequently becomes dependent on its

colonizer. It has an imperialistic character because the system of

government seeks to defend unequal systems of commodity exchange for

its own (Potter et. al., 2008; 48).

Uganda was colonized by the British from 1894-1961. It

eventually became completely independent in 1962 (Griffith, 1986;

209). It is often argued by Africans who oppose homosexuality, that

homosexuality is ‘non-African’, but rather a foreign and ‘western’

37

phenomenon that was ‘brought’ to Africa during colonisation5 (Tamale,

2007; 18). Historically this, however, seems unlikely. According to

Peter Drucker (1993; 6) homosexual activity appears to be universal,

and is thus present in all human societies, across boundaries of

time and culture. At the same time he indicates that it has been

condemned and repressed in many societies.

Also in Africa numerous cultures encountered homosexual

activities, long before the era of colonisation. The Ugandan

academic in law and philosopher Sylvia Tamale (2003; 2) indicates

that different ethnic groups in Uganda acknowledged homosexual

activities. Amongst the Langi in northern Uganda the males were

treated as women and could marry men (Tamale, 2007; 18-19).

Homosexual encounters were also acknowledged among other ethnic

groups: the Iteso, Bahima, Banyoro and the Baganda (Tamale, 2007;

18-19).

The Baganda are even known to have had a bisexual leader, king

Mwanga. Development specialist Epprecht (2013; 115-116) indicates

that in Uganda this history has often been used to create different

narratives on the approval or condemnation of homosexuality.

Narratives of opponents of same-sex sexuality indicate how the

homosexual encounters of king Mwanga set the stage for Uganda’s

subordination under colonial rule. In this narration Mwanga is said

to have become king of a court where many people with different

backgrounds and religions resided. He himself was said to be Muslim

but also upheld several traditional practices. Mwanga thus felt

entitled to practice the traditional polygyny and also felt

authorized to command the sexuality of young men under his

authority. Several British Christian pages that resided at court,

however, refused and were subsequently executed. This led to much

5 When we refer to colonisation we refer to the period during which Uganda was colonized by the British. When we refer to other, previous, forms of colonisation orimperialism (for instance by the Muslims) we will specify this.

38

turmoil in the and eventually led to the British imposing their own

preferred king onto the throne.

This narration of Ugandan history is used in different

discourses concerning same-sex sexuality. Firstly, this narration

indicates that homosexual activities already occurred in Uganda,

prior to colonisation by the British. Opponents, however, argue that

homosexuality was previously ‘brought’ by Muslims after their king

converted to the Islam. Secondly, the interpretation of history as

described above implies that colonisation was the result of, and a

penance for, the misbehaviour of king Mwanga (Epprecht, 2013; 116).

Pre-colonial history thus indicates with certainty that homosexual

encounters occurred in Uganda prior to British colonisation.

Colonisation by the British has laid out an even larger

breeding ground for the anti-queer morality. They have influenced

the perception on homosexuality greatly. Firstly the notion of

identifying people as being ‘homosexual’ was not present amongst

(most) societies. It was only known to be coined in the nineteenth

century in western societies and allowed for people encountering in

homosexual activities to acquire the sexual identity of being gay or

lesbian (Hoad, 2007; 59). This perception of people being

‘homosexual’ is said to be imposed onto colonized countries during

the era of colonisation (Drucker, 1993; 13-15).

Secondly the current perception on homosexuality is greatly

influenced by the sexual, and thus anti-homosexual, mores of that

time. Tamale (2007; 19) indicates that it is not homosexuality that

is foreign to Uganda, but the dominant Judeo-Christian and Arabic

religions upon which most African anti-homosexuality proponents

rely. In ‘the West’ unconventional sex was considered a national

threat as it did not function for the purpose of reproduction.

Epprecht (2013; 125) also indicates that the silencing and

oppression of same-sex activities can be linked to the cause of

39

nation- and empire-building. According to him homosexuality was, at

that time, perceived as a weakness in men. In an era of colonisation

they wanted strong and virile men to confront their enemies with.

Consequently, a lot of ‘scientific’, cultural and religious

evidence against homosexuality was gathered in Europe during the

late nineteenth and early twentieth century (Epprecht, 2013, 125).

The dominant discourse of that time distinguished between normality

and abnormality, between what was respectable and what were sexual

deviances, and between what was morally right and wrong (Stoler,

1995; 34). This led to oppression of (mainly male) same-sex

activity, but also to the silencing of evidence of the existence of

gay men and lesbians (Drucker, 1993; 13). Also in the colonies

homosexual activities were silenced, reflecting the traditional

taboos in British society.

Finally, as a result of the anti-queer perceptions of that

time, the first Anti-Homosexuality laws and systems of surveillance

in Uganda were introduced by the British in order to repress

homosexual activity (Valentine, et. al., 2013; 168 & Epprecht, 2012;

228). According to Thoreson (2014; 28) this is the most obvious

heritage of the British colonialism for LGBTI community. The

prohibition of same-sex activities under the Penal Code Act of 1950

states that “carnal knowledge against the order of nature is

punishable with life imprisonment” (Ottosson, 2010; 20). Though, in

Uganda the British colonial-era laws criminalising male

homosexuality were long ignored, they have now been invoked to

persecute individuals and emergent LGBT groups (Valentine, 2013;

170).

Anti-queer morality can be said to be ‘brought’ with

colonisation. Although little is known about the sentiments towards

homosexuals before colonisation, active discrimination and exclusion

of homosexuals was known to be present in Britain and its colonies

40

during the era of colonisation. Even the first Anti-Homosexuality

laws are known to be introduced by the British.

5.2 Contemporary Cultural Imperialism through American

FundamentalismThough the era of actual colonisation is over, other forms of

contemporary (cultural) imperialism are still present. Not only

during colonisation, but also now, anti-queer perceptions are being

spread across the globe. A popular explanation of the increasing

anti-queer perceptions in Uganda is the presence of American

Fundamentalists6. This relation is especially focussed on in the

media, but also several scholars acknowledge these trends. There are

four main arguments that indicate the plausibility of this

relationship and its importance for the current emergence the anti-

queer morality in Uganda. Firstly, Christian groups like the

American Fundamentalists seek to spread their beliefs around the

globe (Valentine et. al, 2013; 166-167). Secondly, several notorious

American Fundamentalists have visited Uganda and have actively

participated in their debate on homosexuality (Sadgrove et. al.,

2012; 113). Thirdly, local bishops and Ugandan politicians have

often stressed their relationship with the American Fundamentalists

in public (Kaoma, 2009; Epstein, 2007). Fourthly, the Ugandan anti-

queer morality seems influenced by the American one (Gunda, 2010;

Valentine et. al, 2013; Van Klinken, 2012). These four points,

6 The terms 'American Fundamentalists', 'US conservatives', ‘Christian fundamentalists’ or 'the Christian Right' are used interchangeably and without criticism in African media. This is because, as Didi Herman in her book The Antigay Agenda: Orthodox Vision and the Christian Right argues, in Africa the Christian Right falls under the banner of “evangelicalism”, which they relate with a biblical and doctrinal orthodoxy. Furthermore the US Christian conservatives working in Africa are generally called American Fundamentalists for most Africans do not make distinctions between the Christian Right, Fundamentalists, Scott Lively and Rick Warren (Herman, 1997; 5-7). Because we do not want to make it too complex for our readers, we, like the African media, do not distinguish between all these actors andname them all American Fundamentalist.

41

together with the criticism on this view, will be elaborated on in

the following body of text.

Firstly, the imposition of the American Fundamentalists’ anti-

queer agenda in Uganda seems plausible because these Christian

groups seek to spread their beliefs. With declining members and

followers in the US and decreasing credibility due to their

extremism they search for supporters elsewhere (Valentine et. al.,

2013; 166-167). These beliefs include the notion that homosexuality

is sinful and a threat to society. Due to the decreasing members7

and their diminishing credibility the American Fundamentalists are

said to be the losers of the ‘culture war’. This so-called ‘culture

war’ is a figurative war they have been fighting within a

liberalizing and individualizing America. According to Kapya Kaomo,

author of Globalizing the Culture Wars: U.S. Conservatives, African Churches &

Homophobia (2009; 7) the American Fundamentalists are now trying to

globalize the culture wars and therefore spread their beliefs in

countries elsewhere.

Consequently, many American Fundamentalists have travelled the

world to convert others. In Uganda they have found fertile grounds

for their mission. Africa, in general, is a viable option since

supposedly one out of four Christians now live in Africa (Pew

Research Centre, 2011). Many American Fundamentalists therefore

travel to Africa forming a ‘transnational “orthodox” movement’. This

movement retains its orthodox religious perception which greatly

influences the moral perceptions of its adherents. This has resulted

in increasing public opposition of homosexuality within the Anglican

community there (Valentine et. al., 2013; 166-167)8. 7 In the 1980’s around 60-65% of the US population described themselves as being Protestant, in 2008 this had declined to 51%. While the Catholic membership has remained constant around 24% (Pew Research, 2008).8 It should, however, be noted, that issues of homosexuality were hardly addressed in religious circles as moral issues in the 1990’s. Not until the preparation of theLambeth Conference of Bishops in 1998 did it gain the church leaders attention (Ward, 2013; 417-418). Since then the discussion has become more ferocious and

42

The American Fundamentalists in Uganda have set up extensive

communication networks, social welfare projects, education projects

including Bible schools wherein the dangers of homosexuals also

included (Kaoma, 2009; 3). The Fundamentalists are thus very

influential in the promotion of the anti-queer morality according to

Kaoma (2009; 4). These American Fundamentalists gain even more

influence through the financial support they give Ugandan churches

that adhere to their views (Valentine et. al., 2013; 166-167) .

Also the visit of three fundamentalist Americans in 2009 seemed

to be directly connected with the creation of the Anti-Homosexuality

Act that followed shortly. These three American Fundamentalists

organised a three day conference in Kampala, the capital of Uganda.

Amongst them was Scott Lively, who is known for his opposition to

LGBTI rights, and who claims to know more about homosexuality than

anyone else (Blake, 2014). The intention of the conference was to

expose the threat of homosexuality and the ‘gay-agenda’. The

conference attracted many laymen, local pastors and even government

officials. This visit is therefore named as a cause for the

emergence of the Bill, as it would have inspired the politicians

that visited the conference (Sadgrove et. al., 2012; 113).

A third argument supporting the notion of the cultural

imperialism of Uganda by American Fundamentalists is the

conformation and acknowledgement of the relations between prominent

Ugandans (politicians and pastors) and these Americans. We will

elaborate on three recent occurrences that illustrate the

manifestation and impact of such relations. Firstly president

Museveni’s wife, a self-proclaimed conservative born-again

Christian, once visited US president George W. Bush in Washington

D.C. to ask for financial support for her AIDS prevention programs

(Epstein, 2007; 188). These programs, which focus on abstinence and demonizing. The church leaders have often emphasized that sexual orientation is not mentioned in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Tamale 2007).

43

faithfulness, renounce the use of condoms and encourage youngsters

to sign virginity pledges, and thus encourage fundamentalist sexual

morals. Many of these programs are now funded by, and under guidance

of American Fundamentalists (Human Rights Watch/ Africa, 2005; 44).

Another example is that of David Bahati, a member of the young

National Resistance Movement, and the one responsible for the

initial draft of the Anti-homosexuality Bill, claimed himself to

have strong relations with ‘The Family’ a religious political

organisation in the US (Sander, 2010). Moreover, Uganda’s most

infamous pastor Martin Ssempa, who is known to have shown homosexual

pornographic videos in church to prove the harmfulness of

homosexuality, has frequently proved to have strong ties with both

the American Fundamentalists and the government officials of Uganda

(Girard, 2004 & Kaoma, 2009).

Fourthly, due to these relationships the Ugandan anti-queer

morality is said to be influenced by the American one. Valentine et.

al. (2013; 167) claims to see similarities in the fact that both

groups connect homosexuality to paedophilia, stressing the

vulnerability of children and insinuating that homosexuals are out

to recruit these youngsters. Sadgrove et. al. (2012; 116) claim that

both Ugandan- and American Fundamentalists portray homosexuals or

pro-homosexual groups as wealthy and therefore as capable of buying

support, thus warning people not to accept money from people who

might want to lure them into homosexuality. Religious scholar Van

Klinken (2012) sees other connections between anti-queer morality of

Africa and American Fundamentalists. He indicates that both American

and African groups associate homosexuality with the Devil or the

‘End of Times’. Though Van Klinken’s theory is based on Zambia,

religious scholar Masiiwa R. Gunda (2010; 232) affirms that this

belief is widespread in Africa. This is confirmed by religious

scholar Birgit Meyer’s study in Africa generally and her later study

44

in Ghana (Meyer, 1996; Meyer, 2010; 115). We therefore assume that

it is also applicable to Uganda.

Although many religious scholars seem to support the notion

that American Fundamentalists have intensified the anti-queer

morality in Uganda through their imperialism, several scholars do

not agree. While Kamoa regards the relation more as a mutual process

that benefits both, religious scholar Timothy Samuel Shah (2003; 23)

does not agree with this notion in the least bit. According to Shah,

Third World evangelism is “largely an indigenous phenomenon”

emphasising the existence of the AIC’s, the African-Initiated

Churches. Shah (Shah, 2003; 24) argues that the Third World

evangelical agenda does not resemble the American one, for it is

diverse and pluralistic.

But Shah (2003; 28-29) also states that because of this

pluralistic character of African evangelism, these African groups

are not capable of organising a strong national or transnational

movement and more importantly are very prone to manipulation and

cooptation. This seems contradictory to his idea that the American

Fundamentalists do not have any influence, for he suggests that the

American Fundamentalists can, and indeed have, easily co-opted the

African evangelism into their own mission.

5.3 Several Concluding RemarksSo, this chapter has argued and provided insights in how an anti-

queer morality has travelled from the ‘West’ to the ‘rest’. First

this happened due to colonisation by the British. In the 19th century

same-sex encounters were considered inappropriate, uncivil and

immoral and therefore silenced and prohibited in their country and

their colonies.

Contemporary imperialism of anti-queer morality has taken on

other forms. Mainly the American Fundamentalists have actively

45

influenced the emergence and nature of the anti-queer morality in

Uganda. Contrary to the influence of colonisation, Americans

Fundamentalists actually have more supporters in Uganda. The upsurge

of the anti-queer morality is considered the result of a

consolidation of shared meaning by most of Uganda’s society, rather

than the imposition of morals as was the case during colonialism.

One thing that both imperialising trends have in common, however, is

their religious substantiation. During colonialism Christianity was

much more important and present in the British cultural morals but

also in their politics. The validation of religion for the American

Fundamentalists is obvious; they travel to Uganda in order to spread

their religious views and find adherence to their religion.

6. Anti-Queer Animus as a reaction

to the ‘West’In both Religious Studies and Human Geography, the notion of anti-

queer morality as moving from the ‘West to the Rest’ is considered

an important and valid explanation for the upcoming anti-queer

animus in many African countries, including Uganda. This

explanation, however, is paradoxical to another dominant perception

of contemporary cultural globalisation, that of the liberal and

individualizing ‘West’ and the reaction of the ‘rest’ through

fundamentalism and traditionalism (Sadgrove et. al., 2012; 109).

Thus, we find the clarification of anti-queer animus as a ‘Western

export product’ interesting and valid but incomplete given other

global trends, such as individualisation and liberalisation that are

perceived in both Human Geography and in Religious Studies.

An alternative explanation for the increasing anti-queer

morality in Uganda that is derived from contemporary literature is

thus discussed in this chapter. Religious Studies can provide

46

explanations for these trends through focussing on the upcoming

fundamentalism and traditionalism in Uganda, by using the theory of

desecularisation. The disciplinary insights of Human Geography,

African Studies and Postcolonial Studies elaborate on concepts such

as traditionalism, and focus on the manifestation of such anti-

Western reactions in Uganda.

This chapter firstly elaborates on the imperialising and

hegemonic tendency of trends such as liberalisation,

individualisation and the Human Rights. We discuss how such

manifestations of cultural imperialism are perceived in Uganda and

how they evoke reaction. Secondly we will discuss the

desecularisation theory, which explicates how (religious)

fundamentalism and traditionalism are the result of liberalising and

secularising trends in the ‘West’. This is subsequently linked to

the current reinforcement of religious and anti-queer morals in

Uganda.

6.1 A Reaction on the Manifestations of Cultural ImperialismCurrent imperialising trends that are considered and dominant in

both Human Geography and Religious Studies are trends of

individualisation, politics and the Human Rights (Sadgrove et. al.,

2012; 107). These trends are perceived in many ‘Western’ countries’

and are said to have a hegemonic character towards other, less

developed, countries (Sadgrove et. al., 2012; 107). Also human

geographers acknowledge that this hegemonic character of ‘Western’

countries, consequently, leads to action and reaction in

imperialised countries (see: Valentine et. al., 2013; Hoad, 2007;

Epprecht, 2012).

Within the framework of globalisation a global consciousness

has manifested in peoples all over the world (Hoogvelt, 2001; 123).

This global consciousness has led to many international agreements

47

and even the institutionalisation of for instance the Human Rights.

Such international agreements imply that there is a ‘universal’

agreement on the issues addressed.

Such agreements, however, are not freed of Western hegemony.

The Human Rights discourse is often perceived as one of the most

visible forms of Western domination of ‘the Rest’ (Epprecht, 2013;

228). In the Human Rights and development discourse processes of

individualisation and liberalisation are considered important.

According to Valentine (et. al., 2013; 165) this foregrounds the

process of self-actualisation in which individuals have the freedom

to choose between wider ranges of identities, lifestyles and social

ties.

As Africa’s economic development, political and judicial

institutions, health profiles, levels of education and the standard

of living are not as prevailing as in the ‘West’, Africa is often

considered backward according to ‘Western’ scholars (Epprecht,

2004). Consequently the Human Rights projects’ goal seems to be to

transform non-Western cultures into Eurocentric prototypes. The

Human Rights are thus perceived as an instrument of cultural

imperialism (Sadgrove, et. al., 2012; 107-108).

Sexuality and gender have recently become topics of development

and have thus been included in political and Human Rights

discourses. This has created a context in which foreign states can

meddle with issues of sexuality (Epprecht, 2013; 36). The

conservative perceptions on human sexuality, and more specifically

the repression and disavowal of same-sex sexuality in many African

countries, therefore strengthens this notion of Africa being less

developed and civilized than Europe and the United States.

Also, the current ‘Western’ discourse concerning sexuality

implies that the tolerance of same-sex sexuality is a maker of

‘civilized’ sexual values. Within this discourse gay men and

48

lesbians are aligned with the ‘historically’ oppressed (based for

instance of class or racial divides). According to the Zimbabwean

religious scholars Togaresi and Chitando (2011; 122) this current

discourse of (sexual) liberalisation imposes the notion that Africa

still has to be “[…] ‘civilized’ or talked down to accept same-sex

sexuality”. It is, however, ironic that historically the ‘West’

perceived homosexuality as quite the opposite of ‘civilized’ (Hoad,

2007; 57-58).

Furthermore, the importance of individualisation and

liberalisation in the ‘West’ is not as easily transmitted to the

‘rest’. Globalisation, especially of the media, has fostered the

intrusion of Western individualism in places, such as Africa, that

were generally considered to emphasise the communal (Valentine et.

al., 2013; 169).

Epprecht (2012; 228) argues that in Africa, they have lost

confidence in the ‘West’ due to their history of colonisation and

the subsequent adjustment policies that have all had a devastating

impact on African economies and societies. Current interference of

the ‘West’ is thus often perceived as paternalistic, degrading and

depriving of Africa’s own agency. ‘Western’ values and ideas of

development are therefore not blindly adopted in Africa. As a

reaction to this so-called Westernisation strong anti-colonialist

and nationalist discourses of postcolonial rulings have commenced in

several African countries, including Uganda. Their governments seek

to protect their own cultural and national sovereignty by appealing

to their own ‘traditional’ values (Sadgrove et. al., 2012; 108). In

such traditionalist discourses lesbian and gay identities there are

often configured as a consequence of excessive Westernisation and

violation of traditional norms and forms of sexuality (Hoad, 2007;

57). This, however, ignores the notion that Christianity and

colonial traditions also mark Westernisation and have greatly

49

influenced the anti-queer perception there, as depicted in the

previous chapter (Hoad, 2007; 58). Nevertheless, this resistance of

‘western’ (non-Christian) influence further rekindles the anti-queer

discourse.

Valentine (2013; 170) indicates that in the anti-westernisation

discourse the ‘West’ is often depicted as morally degenerate and as

the purveyor of homosexuality through processes of western

imperialism. Consequently, homosexuality in Uganda is perceived, by

many of its inhabitants, as the moral-decline of their ‘own’ nation.

Furthermore the existence of homosexuality is depicted as being

‘foreign’ or ‘Western’ and therefore ‘non-African’ (Valentine, et.

al. 2013; 1654-168). Tamale (2007; 17-18) indicates that in Uganda

it is even implied that there is a network of western homosexual

organisation with an agenda to “recruit” young African men and women

into same-sex sexuality.

The homophobic turn in many African countries, has mobilized

many ‘Western’ scholars and activists, and piqued the interest of

much ‘Western’ media (Epprecht, 2012; 224). As a result many Western

countries have openly expressed support for the LGBTI community in

Uganda and other African countries. Many aid donors have spoken out

against the violation of the Human Rights, and the UK and USA have

even threatened to cut off aid to the violators of the Human Rights

(Epprecht, 2012; 224). This has, however, only invoked the anti-

queer morality, especially in the political sphere, as this creates

a means through which governments can gain agency and invoke their

own rules of enforcement, seemingly independent of ‘Western’

influence. Epprecht (2012; 230) indicates that even same-sex

practicing people in Africa that are “[…]‘out’ as regards to their

sexual orientation have expressed frustration with pressure from the

West”. Western countries often encourage the LGBTI community to be

50

more confrontational and more ‘out’ in Western approved ways,

without considering the cultural differences.

As a result, the synthesis of African nationalism (the result

of current Westernisation) and (colonially, thus ‘Western’,

imported) Christianity has constructed an anti-queer context in

Uganda. The anti-queer morality in Uganda has become part of their

postcolonial identity and is greatly included in their politics

(Hoad, 2007).

6.2 Religion versus Liberalisation“God is winning in global politics. And modernisation,

democratisation, and globalisation have only made him stronger” (Shah

& Toft, 2006; 42).

Many human geographers acknowledge and describe the trends discussed

above, which are perceived in Uganda. Religious scholars acknowledge

that, as a result of globalisation, modernisation, liberalisation

and individualisation, people start to feel lost and unattached to

their communities (Juergensmeyer, 2004; 6). A clear trend has been

noticed by religious scholars, which entails that people start to

seek a sense of community among religious institutions. This does

not only mean that more people fall back on religious communities

but also that these communities are becoming more strongly religious

(Juergensmeyer, 2004, 6). This trend is explained through the

desecularisation theory.

Thus, within Religious Studies, the desecularisation theory

offers a theoretical framework which explains these trends of

conservatism and fundamentalism, that are also acknowledged by human

geographers. This theory offers a religiously invoked explanation

that complement the reactions described above. These seem plausible

in the case of Uganda, due to the strong presence and influence of

religion there (see Chapter 7).

51

Max Weber (1920) was the first to formulate a theory on the

future of religion in his book The Sociology of Religion. In his thesis of

‘Die Entzaubering der Welt’ Weber predicts that the world will

become more and more disenchanted in time. Meaning that a cultural