An empirical analysis of assortative mating in India and the U.S

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

20 -

download

0

Transcript of An empirical analysis of assortative mating in India and the U.S

*Grand Valley State University and University of Minnesota at Morris�U.S.A.

443

An Empirical Analysis of AssortativeMating in India and the U.S.

SONIA DALMIA AND PAREENA G. LAWRENCE*

This paper uses a conditional logit model to analyze empirically how individuals sortthemselves through marriage into households in India and the U.S. The results support positiveassortative mating of spouses with respect to age and schooling. We find no evidence in favorof Becker's theory of labor market specialization in couples. Moreover, while similarity in ageis the strongest predictor of marital choice in India, education of a prospective spouse plays amore important role in the U.S. Finally, we find that while dowry increases the likelihood ofwomen marrying men with characteristics dissimilar to their own, availability of a mate has apositive effect on the degree of stratification in India. (JEL C10, D10, J12); Int�l Advances inEcon. Res., 7(4): pp. 443-458, Nov. 01.©All Rights Reserved

Introduction

How do individuals (or their parents) sort themselves through marriage into households?This is an interesting and important economic issue. It has major implications for thedistribution of income, individual investment in self-improvement, fertility, and so on. It alsoinfluences the parent's efficient allocation of resources [Zhang, 1994, pp. 187-93], maritalstability [Becker et al., 1977, pp. 1141-88], labor market performance of women, and incomeinequality over time. This paper uses micro data from India and the U.S. to analyzeempirically who marries whom. It compares marriages in India, which are predominantlyarranged by the families of the bride and groom and are often accompanied by monetarytransactions, to marriages in the U.S., which are predominantly self-selected. In doing so, twoimportant issues are addressed that have not been examined in the literature. First, dodissimilar societies place different values on characteristics of potential matches? If so, howare they different? Second, does the availability of a potential partner and the presence of adowry affect the choice of one's spouse and, hence, the degree of stratification in themarriage market?

In his seminal work, Becker [1973, pp. 813-46; 1991, pp. 108-15] modeled marriage as aformal maximization problem where individuals derive utility from consuming commodities,which are produced by them via a household production function. When utility is transferableand there is full information, Becker shows that complementary traits between partners yieldthe optimal assignment of positive assortative mating under a centralized marriage market.Becker [1991, p. 108] notes: "An efficient marriage market usually has positive assortativemating, where high-quality men are matched with high-quality women and low-quality menwith low-quality women, although negative assortative mating is sometimes important. An

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4444

efficient market also tends to maximize the aggregate output of household commodities, sothat no person can improve his marriage without making others worse off."

The growing body of evidence on matching with respect to the husband-wife partnershipreveals there is positive assortative mating between partners when traits are complements andnegative or moderately positive assortative mating when traits are substitutes. This impliesthat "likes" tend to match with "likes" with respect to characteristics such as education, age,nonlabor income, and race, while the association is weaker with respect to characteristicssuch as wages and sexual division of labor [Jepsen and Jepsen, 1999, p. 13; Mortensen, 1988,pp. S215-S240; Becker, 1973, pp. 813-46]. An extended survey by Epstein and Guttman[1984, pp. 243-78] documents the widely observed positive assortative mating for many traitsas indicated by the conventional measure of simple correlations. Positive correlations arereported for intelligence, age, education, race, nonmarket income, religion, ethnic origin,height, and geographical propinquity of spouses. Studies that have focused on thesubstitutability of traits such as rich man/attractive wife have found mixed results [Stevenset al., 1990, pp. 62-70].

Only recently have economists turned their attention to marital choices that matchhusbands and wives, making use of household production and search theory [Keeley, 1997,pp. 238-50; Burdett and Coles, 1997, pp. 141-68; Wong, 1988]. Most of these studies aredescriptive in nature and do not separate covarying factors in mate selection. It is not clearhow the presence of other traits affects the sorting behavior of a particular trait. For example,how does age affect sorting by education? It is also not clear whether there is a distinctdifference regarding assortative mating in marriages that are arranged by parents andmarriages that are self-selected. In addition, while prior research has documented theassociation between marital opportunities and the decision to marry [Freiden, 1974, pp. S34-S53], little attention has been paid to whether marital opportunities influence the choice ofone's spouse. Thus, if women face a shortage of appropriate marriageable mates, do theymarry men with traits that differ from their optimal match under normal conditions?

Evidence of positive simple correlations for a variety of traits is certainly consistent withBecker's theory of sorting. A more powerful test of his theory, however, requires evidenceon how specific matching characteristics are sorted when various other traits are heldconstant. In all research on assortative mating, note that assessment of direct assortativemating for a trait under study, such as religion, may be confounded with assortative matingfor an associated characteristic such as ethnic origin, cohort effects, or secular trends.Therefore, in testing suggested theories of mate selection, care must be taken to separate themultivariate factors.

Although Becker predicts positive and negative assortative mating for a variety ofindividual traits, he does not suggest a specific model to test his predictions. To explorewhether the data support the implications of his analytical marriage model of positiveassortative mating with respect to complementary traits and negative assortative mating withrespect to traits that are substitutes, the method of conditional logit is used to examine maritalchoice. The conditional logit model tests whether or not traits are more closely correlatedwithin married couples than across pairs of individuals who are not married. Thus, if likesmarry likes, a person will be more similar to his spouse than to a random individual. Jepsenand Jepsen [1999] used a similar methodology to compare marital sorting traits of same-sexcouples to those of opposite-sex couples.

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 445

The results in this present paper support positive assortative mating of spouses for bothIndia and U.S. with respect to age and schooling. Evidence in favor of positive assortativemating on height, parental wealth, and race appears mixed and weak. No evidence is foundin favor of Becker's theory of labor-market specialization in couples. Moreover, the resultsreveal that, traditional roles within married couples (for example, women marrying older andmore educated men) increase the probability of observing an actual match. In comparingmatching patterns across India and the U.S. and to isolate the factors that affect maritalchoice, similarity in age is found to be the strongest predictor of marital choice in India,followed closely by education. The education of a prospective spouse plays the mostimportant role in predicting a marital match in the U.S. As expected, the degree of assortativemating is found to be higher in the U.S., thus indicating that marriage markets are moreefficient in the U.S. compared to India with respect to age and education.

Furthermore, it is found that a monetary transfer or dowry from the bride's family to thegroom's family increases the chances of women marrying men with characteristics dissimilarto their own. Thus, the dowry acts as a transfer mechanism to compensate for a lack ofassortative mating in the Indian marriage market. Significant regional variation in the patternof assortative mating in India is also found. The probability of likes marrying likes washigher in southern India than in northern India. In addition, the influence of the gender ratioon assortative mating, though insignificant, reveals that an unfavorable marriage market,measured in terms of the relative number of women to men, decreases the chances of womenmarrying men with characteristics similar to their own. Furthermore, the coefficient on theyear of marriage, though insignificant, suggests that the probability of likes marrying likeshas increased over time, implying that tastes in India have changed to reflect more assortativemating.

This paper is organized as follows. The second section describes the estimationmethodology used to test Becker's theory of marriage, and the third section details the dataand presents the descriptive statistics. The fourth section reports the results, and the fifthsection concludes.

Estimation Methodology

This paper tests whether or not married couples are more similar to their mates than toanother randomly selected potential mate. Hence, this paper takes the characteristics of thealternative approach, which is appropriately estimated with McFadden's [1973, pp. 105-35]conditional logit model. This methodology is adopted from Jepsen and Jepsen [1999], whouse a conditional logit model to compare marital sorting traits of same-sex couples to thoseof opposite-sex couples.

It is often difficult to attach a behavioral interpretation to the results of models thatexclusively focus on the characteristics of the chooser, as estimated by the conventionalmultinomial logit techniques. The conditional logit model captures the impact of varioustraits of two individuals choosing each other as partners. Hoffman and Duncan [1998, pp.415-27] state: "It is more appropriate when the choice among alternatives is modeled as afunction of the characteristics of the alternatives, rather than (or in addition to) thecharacteristics of the individual making the choice," and, according to Jepsen [1998, p. 8],

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4446

"when the 'chooser' chooses from a set of characteristics of different alternatives in order tomaximize utility."

Both multinomial logit and conditional logit are used to analyze the choice of an individualamong a set of prospective mates. However, while the multinomial logit focuses on theindividual as the unit of analysis and uses the characteristics of the individual (such as age,race, and education of the chooser) as explanatory variables, the conditional logit focuses onthe set of alternatives for each individual, and the explanatory variables are characteristicsof those alternatives (such as age, race, and education of prospective mates).

Let be the characteristics of the jth alternative for individual i, and β is theZijcorresponding parameter vector. Let J be the number of unordered alternatives, and is thePijprobability that individual i chooses alternative j. The choice probability in the conditionallogit model is then:

Pij 'e (Zij β )

j Jk'1 e [ (Zik& Zij )β]

. (1)

Note that the explanatory variables, Z, assume different values in each alternative. However,the impact of a unit of Z is usually, though not necessarily, assumed constant acrossalternatives. Thus, only a single coefficient is estimated for each Z variable. So the impactof a variable on the choice probabilities derives from the difference in its value acrossalternatives [McFadden, 1973, pp. 105-35]. Thus, (1) can be rewritten as:

Pij '1

j Jk'1 e [ (Zik& Zij )β]

. (2)

The application of a conditional logit model to the process of choosing a mate requiresseveral steps. First, define the independent variable to capture the effects of a potential mate'scharacteristics in relation to the characteristics of the chooser. Since the choice of a matedepends not only on the characteristics of a potential partner but also on the characteristicsof the chooser, define the independent variable to be the absolute value of the difference inthe characteristics of the mate and the chooser. In doing so, we assume that only thedifference in the values of the individual characteristics matter and not the direction of thedifference (the validity of this assumption is tested in the fourth section).

Second, specify the alternatives for the chooser, given that only the outcome of the choiceis observed, that is, the actual match. In other words, we know whom a person chooses as aspouse but not who was considered while making the final choice. Unfortunately, the datasets do not contain information on who was rejected while selecting a marriage partner.Therefore, a rejected match is created for each household head in India and the U.S.

There are several ways to create a rejected match. For instance, an individual householdhead, usually a male, can be paired with the average woman in the sample who is not theperson's actual mate. Alternatively, the individual household head can be matched with arandomly selected woman from the sample, who is not the person's actual partner. This paper

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 447

uses the latter approach to create rejected matches to avoid the possibility of each male in thesample rejecting the same female. Since the average of the characteristics of the women notchosen will not have much variance, this method would essentially involve all men rejectingapproximately the same match. Therefore, a randomly selected individual will not only bemore representative of a rejected match but will also increase the variation in the samplecompared with using the average match of persons not selected.

The rejected match is created by pairing each household head with a randomly selectedindividual who is not the person's actual partner. For example, suppose Person 1, a male, ismarried to Person 2, a female. To create a rejected match for Person 1, randomly selectPerson 3, a female, who is married to a male other than Person 1. In this case, matchingPerson 1 with Person 2 is the actual match, while matching Person 1 with Person 3 is therejected match. Therefore, the sets of alternatives for Person 1 are Person 2 and Person 3.This procedure is repeated to create a rejected match for each household head in the data sets.Although each married male can be paired with every other married female, this analysis isrestricted to one rejected match per household head to maintain a matrix of workable size.

Finally, evaluate the predicted effects of the independent variable on the alternatives ina way that is consistent with Becker's predictions of positive and negative assortative mating.The predicted effects of the characteristics suggest an inverse relationship between theprobability of an actual match and characteristics that are complements. For example, ifpeople prefer mates with an educational background similar to theirs, we would expect to seea small difference in education within couples. In other words, if education were acomplementary trait, a small difference in years of schooling would likely predict a match.

The predicted effects also suggest a positive relationship between characteristics that aresubstitutes and the probability of observing an actual match. For instance, if higher-earningmales are to be matched with lower-earning females, as Becker predicts, then the greater thedifference between the earnings of a husband and wife, the more likely they are to be anactual match, ceteris paribus. Thus, negative coefficients are expected for the variables age,education, height, caste, parental wealth, and race, and positive coefficients are expected forthe variables wages and hours worked in the market.

Data and Descriptive Statistics

The data for India used in this study are obtained from the Census of India [RegistrarGeneral of India, various] and data concerning marriage transactions and individual andhousehold characteristics are obtained from a retrospective household survey from theNational Council of Applied Economic Research [1995]. The fieldwork took place betweenJuly 1995 and September 1995. Seventy villages from northern and southern India werechosen for this study, resulting in a sample size of 1,878 households. However, since mostmales in India are married by the age of 32 [Dalmia and Lawrence, 1999, p. 38], we consideronly those households in which the age of the household head (male) at the time of thepresent marriage is less than or equal to 32. This leaves a sample size of 905. The sample istruncated by this criterion to avoid the possibility of outliers and second marriages.

Some observations related to the data deserve mention. First, most marriages hadtransactions on both sides associated with them, reflecting a ritual gift exchange between thetwo families. To isolate the price component of the transfers, the net value of the transfer is

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4448

considered. One major problem with the net dowry variable is that the dowries in the samplewere made at vastly different points in time, since the earliest marriage dates to 1956 and themost recent to 1994. To deal with this problem, all net dowry values were converted toconstant 1994 prices.

Second, data on the premarital income of the bride and groom households is not available.However, it is likely to be highly correlated with parental household wealth at the time ofmarriage. It is important that this wealth variable reflect the bride and the groom household'swealth position before or at the time of marriage. The 1995 retrospective survey obtainedinformation on the parental household wealth (in terms of land owned) of both marriagepartners just before they were married. Using this wealth variable ensures that the bride'shousehold wealth variable is exogenous to groom selection and dowry decisions.

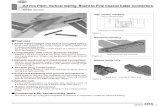

The Indian census data are used to construct the marriageable age-gender ratio, providinga more accurate measure of the marriage offer rate instead of the more traditional female-male gender ratio (shown in Figure 1). The latter ratio, which is less than 1 for India, shouldgive women an advantage in the marriage market since fewer females per male should implya higher marriage offer rate for women. However, this is an inaccurate measure of theavailability of potential spouses in the Indian marriage market. This ratio would be adequateif men and women were to marry at the same average age. However, culture and social normsdictate otherwise.

FIGURE 1Gender Ratio in India

0.98

0.97

0.96

0.95

0.94

0.93

0.92

1881 1891 1901 1911 1921 1931 1941 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991

Source: Census of India [Registrar General of India, various].

It is well documented that women marry at a relatively younger age than men [Goyal1988]. Therefore, a more precise measure of surplus brides or grooms and the resultingmarriage offer rate is the ratio of women of marriageable age to men of marriageable age andthe trend of this ratio. The calculated marriage offer rate (shown in Figure 2) shows that agehypergamy, marrying older men, in the Indian marriage market completely reverses a female

Fem

ales

to M

ales

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 449

marriage market advantage. Therefore, what had been a surplus of males without agehypergamy becomes a surplus of females with it.1

FIGURE 2Marriage Offer Rate Using Reconstructed Data

1.4

1.2

1.0

0.8

0.6

1881 1891 1901 1911 1921 1931 1941 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991

Source: Dalmia and Lawrence [1991].

To compare arranged marriages in India with self-selected marriages in the U.S., data fromthe March 1998 Current Population Survey is used. The data set contains information onemployment status, earnings, hours worked, and other indicators for 98,970 households.These are available by a variety of demographic characteristics including age, sex, race,marital status, and educational attainment. They are also available by occupation, industry,and class of worker. Since we are interested in who matches with whom, we consider onlythe married households. Unlike in the Indian data set, there is no information on whether ornot this is the couple's first marriage.

Correlation of traits between spouses in the literature generally represents degrees ofsimilarity on the trait studied after some (usually unspecified) years of marriage. Thesesimilarities may be due to actual mate choice, but they could also be the result ofconvergence during years of marriage. To overcome this discrepancy in the U.S. data set, thisstudy is restricted to households in which the head is less than or equal to 40 years old. Thisresults in a sample size of 8,198. The variables of interest are defined as follows. Age ismeasured in years; race is a dummy variable that takes on a value of 1 if the individual's raceis white and zero if the individual's race is not white; schooling is the highest year of formaleducation completed (converted from census codes); U.S. earnings are the individual's annualwage and salary income; and hours are the average number of hours worked in the marketper week.

Summary statistics of the variables used in the empirical analysis are presented in Table1 for India. Both educational level attained and age of the couple are measured at the timeof marriage. The data shows significant variation in the net dowry transfer as measured bythe standard deviation. It is interesting to note that while grooms are older, taller, and moreeducated than their brides, the parents of the bride owned more land than the parents of thegroom. This indicates a fair degree of male hypergamy in the sample.

Fem

ales

(10-

19 y

ears

old

)to

Mal

es (2

0-29

yea

rs o

ld)

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4450

TABLE 1Summary Statistics of Data from India

Variables Mean Standard Deviation

Net dowry (in constant 1994 rupees) 134,077.00 167,225.30Groom's age at marriage 21.76 4.77Bride's age at marriage 16.06 3.51Groom's schooling (in years) 4.79 4.76Bride's schooling (in years) 2.06 3.55Groom's height (in centimeters) 163.69 6.57Bride's height (in centimeters) 152.00 7.80Groom's parental landholdings ( in acres) 3.12 6.68Bride's parental landholdings ( in acres) 3.77 9.78Year of marriage (19xx) 79.23 8.80Marriageable age-gender ratio 1.10 0.08High caste 0.44 0.50Medium caste 0.40 0.50Low caste 0.16 0.36Uttar Pradesh 0.45 0.50Karnataka 0.55 0.50

Summary statistics for the U.S. data set are presented in Table 2. While the average ageof the female respondent (bride) at the time of the interview was 31.08, her spouse (groom)was 32.66 years old, with 12.92 years of schooling for both. The annual earnings of theaverage bride and groom were $15,374 and $34,468, respectively, and their hours worked perweek were 23.28 and 39.74, respectively. In the sample, 89 percent of the brides and groomswere white. Unfortunately, data on married couples from the U.S. and India are notcomparable with respect to traits other than age and schooling.

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 451

TABLE 2Summary Statistics of Data from the U.S.

Variables Mean Standard Deviation

Groom's age at marriage 32.66 4.95Bride's age at marriage 31.08 5.23Groom's schooling (in years) 12.92 2.93Bride's schooling (in years) 12.92 2.73Groom's earnings (in dollars) 34,467.99 36,676.89Bride's earnings (in dollars) 15,374.05 21,846.86Hours worked by the groom 39.74 18.12Hours worked by the bride 23.28 19.78Groom's race (white) 0.89 0.311Bride's race (white) 0.89 0.313

Pearson correlation coefficients are presented in Table 3. They show positive (althoughnot perfect) assortative mating across all the traits. The individual traits of the groom havehighly significant and positive association with the respective traits of the bride. For the traitsthat Becker characterizes as complements (age, schooling, height, parental wealth, race, andcaste), there are positive correlations. However, for substitute traits (earnings and hoursworked), there are no negative correlations, as predicted by Becker. Though smaller inmagnitude, these correlations imply that husbands and wives are positively sorted on earningsand hours worked. Overall, married couples show the strongest patterns of matching withrespect to age.

TABLE 3Pearson Correlation Coefficients for India and the U.S.

Variables India U.S.

Age 0.747 0.777Schooling 0.501 0.655Earnings 0.087Race 0.786

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4452

TABLE 3 (CONT.)

Variables India U.S.

Hours worked 0.074Height 0.457Parental wealth 0.091High caste 1.000Medium caste 1.000Low caste 1.000

The correlations, where comparable, indicate a lower degree of assortative mating on ageand years of schooling in India compared to the U.S. The difference between the twosocieties, however, was greater with schooling than with age. Comparing marriages withinthe same race (U.S.) to marriages within the same caste (India), it is found that while thecorrelation for same-race marriages was 0.79 for the U.S., there were no intercaste marriagesin India. Though the correlation results provide strong support for the hypothesis that likesmarry likes, they do not control for the effects of other variables on marital choice.

Results

The results of the conditional logit model specified in (1) are presented in Table 4 forIndia. As mentioned earlier, the predicted effects of the characteristics suggest an inverserelationship between the probability of an actual match and characteristics that arecomplements, such as education, age, schooling, parental wealth, and caste or race, and apositive relationship between characteristics that are substitutes, such as earnings or wagesand hours worked in the labor market.

TABLE 4Conditional Logit Results for India

Variables Coefficients Marginal Effects

Age -0.0549867* (12.17) -0.013746675Schooling (in years) -0.0542336* (15.86) -0.013558400Height (in centimeters) -0.0008193 (0.51) -0.000204825

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 453

TABLE 4 (CONT.)

Variables Coefficients Marginal Effects

Parental landholdings (in acres) 0.0006767 (0.56) 0.000169175Net dowry transfer

(in constant 1994 rupees) -0.0036910** (1.65) -0.000922700Year of marriage 0.0062746 (1.30) -0.001568650Marriageable age-gender ratio -0.5778872 (0.36) -0.144471800Utter Pradesh (northern India) -0.0374231* (2.24) -0.009355775

Notes: * and ** denote significance at the 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively. Absolute t-values are in parentheses.

The negative coefficients on age and education support Becker's assertion of positiveassortative mating for these traits. Height and parental wealth, however, were found to havean insignificant effect on the probability of observing an actual match. The negativecoefficient on net dowry suggests that monetary transfers from brides and their families togrooms and their families increase the chances of women marrying men with characteristicsdissimilar to their own. This lends support to the argument that dowries compensate forbride-groom quality differences. Prior research [Dalmia and Lawrence 1999, p. 10; Dalmia,2001] suggests that marriage transactions equalize the value of marriage services exchangedby the households of the bride and groom. In other words, the dowry is payment forestablishment of a desirable marital alliance, one in which the groom's status, age, height,education, hence, income earning potential is higher than that of the bride.

The positive coefficient on the year of marriage, though insignificant, implies that, ceterisparibus, the probability of likes marrying likes has increased over time, suggesting that tastesin India have changed to reflect more assortative mating. It also supports the result that theamount of real dowries over time has declined in India [Dalmia, 2001]. The influence ofgender ratio on assortative mating, though insignificant, is as expected: a demographicshortage of suitable mates decreases the chances that women will marry men withcharacteristics similar to their own.

Finally, the probability of observing an actual match is lower in northern India comparedto southern India. This is partly consistent with the ethnographic evidence pointing to a broadnorth-south dichotomy in marriage markets in India [Miller, 1980, pp. 95-129; Srinivas,1984; Dyson and Moore, 1983, pp. 35-60]. According to this ethnographic evidence, the tworegions of northern India and southern India have structurally distinct kinship patterns andmarriage systems. Northern India is strongly patrilineal, and from this basic principle flowits other characteristic features: rules of exogamy, exclusion of women from property rights,the ideology of marriage accompanied by dowry, and hypergamy [Trautmann, 1993]. On theother hand, southern India is characterized by marriages between close relatives (notably,children of siblings of the opposite gender), status equity between wife-givers and wife-takers

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4454

(that is, isogamy), and recognition of women's rights to land, which may raise the probabilityof observing an actual match.

The results of the conditional logit model for U.S. are reported in Table 5. The negativerelationship between the difference in age, schooling, and race of partners as well as theprobability of observing an actual match support Becker's predictions of positive assortativemating for these traits. The impact of race, however, is insignificant. This is probably becauseof the very few interracial marriages in the sample (11 percent). For the variables where wemight expect opposites to attract due to labor market specialization, earnings, and hoursworked, instead, likes are pairing with likes. However, only earnings are a significantpredictor of an actual couple. Thus, there is no support for Becker's theory of a sexualdivision of labor as manifested by negative assortative mating for wages and hours worked.

TABLE 5Conditional Logit Results for the U.S.

Variables Coefficients Marginal Effects

Age -0.0705353* (39.15) -0.017633825Schooling (in years) -0.1020924* (42.07) -0.025523100Race -0.0200425 (1.34) -0.005010625Earnings -0.0008738* (6.77) -0.000218450Hours -0.0002716 (1.15) -0.000067900

Notes: * denotes significance at the 5 percent level. Absolute t-values are in parentheses.

Considering the marginal effects of schooling and age, similarities in age are a strongerpredictor of observing an actual match in India than similarities in schooling, though only bya marginal amount. For the U.S., similarity in schooling is the strongest predictor ofobserving an actual match. The magnitude of the marginal effect of earnings is very small:a $1,000 increase in the difference in earnings decreases the probability of being an actualmatch by .2 percent. Comparing the marginal effect of differences in age and education onthe probability of observing an actual match for India and the U.S. reveals once again thatassortative mating with respect to these characteristics is stronger in the U.S. compared toIndia. A one-year increase in the difference in age, for instance, decreases the probability ofbeing an actual couple by 1.4 percent for India and 1.8 percent for the U.S., while a one-yearincrease in the difference in education decreases the probability of observing an actual coupleby 1.3 percent for India and 2.5 percent for U.S.

The dependent variable in the conditional logit regression is the absolute value of thedifference in the characteristics of the mate and the chooser. In doing so, we assume that onlythe difference in the values of the individual characteristics matters and not the direction ofthe difference. The most common difference in the attributes of prospective mates is with

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 455

gender. That is, we expect the males to be older, more educated, work more hours, and so on.To test whether the direction of the difference in the individual characteristics affects theprobability of a natural match, dummy variables are introduced to capture the tradition orrole effect [Jepsen, 1998, p. 10].

Specifically, dummy variables are defined for age, education, height, parental wealth,earnings, and hours worked, taking the value of 1 if the woman is older, more educated,taller, and so on, that is, if the pairing reflects a nontraditional match as opposed to a moretraditional match. Since the existence of a nontraditional characteristic should decrease theprobability of a natural match and if tradition is followed in choosing partners, negativecoefficients are expected on all dummy variables.

The results of the conditional logit model with the role effect in Tables 6 and 7 are similarto the results reported in Tables 4 and 5, respectively, suggesting that direction does notmatter.

TABLE 6Conditional Logit Results for India with Role Variables

Variables Coefficients Marginal Effects

Age -0.0549867* (12.17) -0.013746675Schooling (in years) -0.0542336* (15.86) -0.013558400Height (in centimeters) -0.0008193 (0.51) -0.000204825Parental landholdings (in acres) 0.0006767 (0.56) 0.000169175Net dowry transfer

(in constant 1994 rupees) -0.0036910** (1.65) -0.000922700Year of marriage 0.0062746 (1.30) 0.001568650Marriageable age-gender ratio -0.5778872 (0.36) -0.144471800Uttar Pradesh (northern India) -0.0374231* (2.24) -0.009355775Age dummy -0.0385199* (11.88) -0.009629975Schooling dummy -0.0107994* (14.36) -0.002699850Parental landholding dummy 0.0373992 (0.56) 0.009349800

Notes: *and ** denote significance at the 5 and 10 percent levels, respectively. Absolute t-values are in parentheses.The height dummy was dropped since no marriage involved a taller woman matched with a shorter man.

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4456

TABLE 7Conditional Logit Results for the U.S. with Role Variables

Variables Coefficients Marginal Effects

Age -0.0705353* (39.15) -0.017633825Schooling (in years) -0.1020924* (42.07) -0.025523100Race -0.0200425 (1.34) -0.005010625Earnings -0.0008738* (6.77) -0.000218450Hours -0.0002716 (1.15) -0.000067900Age dummy -0.0054146* (3.85) -0.001353650Schooling dummy -0.2191076* (8.74) -0.054776900Earnings dummy -0.0231704* (6.73) -0.005792600Hours dummy -0.0056211 (1.63) -0.001405275

Notes: * denotes significance at the 5 percent level. Absolute t-values are in parentheses.

The dummy variables for age and education for India and age, education, and earnings forthe U.S. are significant at the 5 percent level, the effects of which are as expected. Forcouples in India and the U.S., if the woman is older or more educated, for example, they areless likely to be an actual match. In other words, if people prefer a traditional match, theexistence of nontraditional characteristics reduces the probability of such a match.

Conclusions

This paper uses micro data from India and the U.S. to analyze empirically who matcheswith whom. While several studies in economics and sociology have researched matching withrespect to marriage, most are merely descriptive and do not separate covarying factors inmate selection. For example, it is not clear how the presence of other traits affects the sortingbehavior of a particular trait. It is also not clear whether there is a distinct differenceregarding assortative mating in marriages that are arranged by parents and marriages that areself-selected. Although prior research has documented the association between maritalopportunities and the decision to marry, little if any attention is given to the question ofwhether marital opportunities also influence marital choices. In addressing these issues, thispaper makes an important contribution to economics literature on marriage and matching.

Estimates of the conditional logit model for India and the U.S. strongly support Becker'sprediction of positive assortative mating with respect to age and education. That is, youngerwomen marry younger men and women with more education marry more educated men.Moreover, these results reveal that traditional roles within married couples (such as womenmarrying older, more-educated men) increase the probability of an actual match. However,

DALMIA AND LAWRENCE: MATING IN INDIA AND THE U.S. 457

evidence in favor of positive assortative mating with respect to height and parental wealthin India and race in the U.S. appears to be mixed and weak. Consistent with other research[Jepsen, 1998], no evidence is found to support negative assortative mating for individualcharacteristics that are substitutes, such as wages or earnings and hours worked, as a directconsequence of sexual division of labor. Instead, it is found that likes match with likes withrespect to these characteristics in the U.S.

In comparing the matching patterns across societies to isolate the factors that affect maritalchoice, we find that while similarity in age is the strongest predictor of observing an actualmatch in India, the education of a prospective spouse has a dominant effect on marital choicein the U.S. As expected, the degree of assortative mating on individual spousal characteristicsis higher in the U.S. compared to India given the self-selection of mates in the former and theexistence of dowries and marriages arranged by the bride and groom's families in the latter.This indicates that marriage markets are more efficient in the U.S. compared to India withrespect to spousal characteristics of education and age.

Moreover, the dowry increases the likelihood of women marrying men with characteristicsdissimilar to their own. This is an important result because it provides support for theequalizing differences in the role of marital arrangements in India. In regions of southernIndia, the degree of assortative mating on average appears to be higher. Finally, results onthe effect of gender ratio on the choice of one's spouse, though insignificant, reveal that theavailability of a mate negatively affects the degree of stratification. That is, an unfavorablemarriage market, measured in terms of the relative number of women to men, decreases thechances that women will marry men with characteristics similar to their own. In addition, thecoefficient on the year of marriage, though insignificant, suggests that the probability of likesmarrying likes has increased over time, implying that tastes in India have changed to reflectmore assortative mating.

Footnotes

1. For details on this calculation procedure, see Dalmia and Lawrence [1999, p. 15].

References

Becker, Gary S. "A Theory of Marriage: Part I," Journal of Political Economy, 81, 1973, pp. 813-46.. A Treatise on the Family, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Becker, Gary S.; Landes, Elisabeth M.; Michael, Robert T. "An Economic Analysis of MaritalInstability," Journal of Political Economy, 85, 1977, pp. 1141-88.

Burdett, K.; Coles, M. "Marriage and Class," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 1997, pp. 141-68.Dalmia, Sonia. "A Hedonic Analysis of Marriage Transactions in India: Estimating Demand for

Dowries and Groom Characteristics in Marriage," working paper, Grand Valley State University,2001.

Dalmia, Sonia; Lawrence, Pareena. "The Institution of Dowry," unpublished manuscript, 1999.Dyson, Tim; Moore, M. "On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in

India," Population and Development Review, 9, 1, March 1983, pp. 35-60.Epstein, Elizabeth; Guttman, Ruth. "Mate Selection in Man: Evidence, Theory and Outcome," Social

Biology, 31, 1984, pp. 243-78.

IAER: NOVEMBER 2001, VOL. 7, NO. 4458

Frieden, Alan. "The U.S. Marriage Market," Journal of Political Economy, 82, 2, 1974, pp. S34-S53.Goyal, R. P. Marriage Age in India, Delhi, India: BR Publishing, 1988.Hoffman, Saul D.; Duncan, Greg J. "Multinomial and Conditional Logit Discrete-Choice Models in

Demography," Demography, 25, 1998, pp. 415-27.Jepsen, Lisa K. "Do 'Likes' Still Like 'Likes' in the '90s?," doctoral dissertation, Vanderbilt University,

1998.Jepsen, Lisa K.; Jepsen, Christopher A. "An Empirical Analysis of Same-Sex and Opposite-Sex

Couples: Do 'Likes' Still Like 'Likes' in the '90s?," working paper, WP-99-5, NorthwesternUniversity Institute of Policy Research, 1999.

Keeley, Michael C. "The Economics of Family Formation," Economic Inquiry, 15, 1997, pp. 238-50.McFadden, D. "Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior," in P. Zarembka, ed.,

Frontiers in Econometrics, New York, NY: Wiley and Sons, 1973, pp. 105-35.Miller, Barbara. "Female Neglect and the Costs of Marriage in Rural India," Contributions to Indian

Sociology, 14, 1, 1980, pp. 95-129.Mortensen, Dale. "Matching: Finding a Partner for Life or Otherwise," American Journal of

Sociology, 94, 1988, pp. S215-S240.National Council of Applied Economic Research. "Poverty, Gender Inequality, and Reproductive

Choice," survey, 1995.Registrar General of India. Census of India, New Delhi, India: Ministry of Home Affairs, various.Srinivas, M. N. Some Reflection on Dowry, Delhi, India: Oxford University Press, 1984.Stevens, Gillian; Owens, Dawn; Schaefer, Eric C. "Education and Attractiveness in Marriage

Choices," Social Psychology Quarterly, 53, 1990, pp. 62-70.Trautmann, Thomas R."The Study of Dravidian Kinship," in Patricia Uberoi, ed., Family, Kinship, and

Marriage in India, New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press, 1993.Wong, Linda. "Essays on Matching and Mating: Stratification, Assimilation, and Family-Income

Inequality," doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa, 1998.Zhang, Junsen. "Bequest as a Public Good Within Marriage: A Note," Journal of Political Economy,

102, 1994, pp. 187-93.