Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management of psoriasis from American and German...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management of psoriasis from American and German...

Journal of the Saudi Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery (2011) 15, 5–13

King Saud University

Journal of the Saudi Society of Dermatology &

Dermatologic Surgerywww.ksu.edu.sawww.jssdds.org

www.sciencedirect.com

REVIEW ARTICLE

Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management

of psoriasis from American and German guidelines q

Ali A. Al Raddadi a,*, Mohammad I. Fatani b, Yasir H. Shaikh c, Diamant Thaci d,

Abdullah A. Al Reshaid e, Abdullah M. Al-Eisa f, Walid A. Alghamdi g,

Hassan Y. Abdulfattah h, Zohir M. Al Belbisi h, Ali C. Atawi i,

Waleed A. Alajroush e, Abdullah A. Al Fadly j, Said I. El-Shamy k,

Sameer K. Zimmol, Abdullah A. Alqahtani

m, Majdy M. Abdulghani

n,

Khaled M. Al Abodo, Khaled M. Al Attas

p, Mohamad F. Al Ayouby

q,

Mohammed S. Qari l, Adel S. Al Ghanim r

a National Guard Hospital, King Abdulaziz Medical City, PO Box 9515, Jeddah 21423, Saudi Arabiab Hera General Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabiac King Fahd Specialist Hospital, PO Box 15215, Dammam 31444, Saudi Arabiad Goethe University, Frankfurt, Senckenberganlage 3160325, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

q Developed by the guideline committee of the following members: (1)

Dr. Ali Atallah Al Raddadi, Jeddah; (2) Dr. Sameer Khader Zimmo,

Jeddah; (3) Dr. Mohammed Saleh Abdulfattah Qari, Jeddah; (4) Dr.

Majdy Mohammed Rashad Abdulghani, Jeddah; (5) Dr. Diamant

Thaci, Germany; (6) Abdullah Abdelrahman Al Reshaid, Riyadh; (7)

Dr. Abdullah Mohammed. H. Al-Eisa, Riyadh; (8) Dr. Walid Ali

Alghamdi, Riyadh; (9) Dr. Hassan Yaser N. Abdulfattah, Riyadh; (10)

Dr. Zohir Mustafa Al Belbisi, Riyadh; (11) Dr. Ali Charif Atawi,

Riyadh; (12) Dr. Waleed Ahmed S. Alajroush, Riyadh; (13) Dr.

Abdullah Abdulmohsen Al Fadly, Riyadh; (14) Dr. Said Ibrahim El-

Shamy, Riyadh; (15) Dr. Yasir Hasan Shaikh, Dammam; (16) Dr.

Adel Soliman Al Ghanim, Dammam; (17) Dr. Abdullah Aljubran

Alqahtani, Abha; (18) Dr. Mohammad Ibrahim Fatani, Makkah; (19)

Dr. Khaled Mohamed Al Abod, Makkah; (20) Dr. Khaled M. Al

Attas, Jazan; (21) Dr. Mohamad Fakhry Al Ayouby, Madinah.* Corresponding author. Address: Dermatology Division, King

Abdulaziz Medical City, P.O. Box 9515, Jeddah 21423, Saudi Arabia.

E-mail address: [email protected] (A.A. Al Raddadi).

2210-836X ª 2010 King Saud University. Production and hosting by

Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

doi:10.1016/j.jssdds.2010.10.002

Production and hosting by Elsevier

6 A.A. Al Raddadi et al.

e National Guard Hospital, King Abdulaziz City, PO Box 22490, Riyadh 22490, Saudi Arabiaf Derma Clinic, Alolia - Cross of Athalatheen Street & Aldabab Street, Riyadh, Saudi Arabiag Security Force Hospital, PO Box 3643, Riyadh 11481, Saudi Arabiah Riyadh Medical Complex, PO Box 2897, Riyadh 11196, Saudi Arabiai Specialized Medical Center, PO Box 66548, Riyadh 11586, Saudi Arabiaj King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, PO Box 3354, Riyadh 11211, Saudi Arabiak National Hospital, PO Box 2715, Riyadh 11461, Saudi Arabial King Abdulaziz University, PO Box 80200, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabiam Military Hospital, PO Box 101, Khamis Mushait, Saudi Arabian King Fahd Military Hospital, PO Box 9862, Jeddah 21159, Saudi Arabiao King Faisal Hospital, Al Munhana Street, Shisha, Makkah, Saudi Arabiap King Fahd Central Hospital, PO Box 204, Jazan, Saudi Arabiaq King Fahd Hospital, PO Box 3892, Madinah, Saudi Arabiar King Fahd Military Medical Complex, PO Box 946, Dahran 31932, Saudi Arabia

Received 10 June 2010; accepted 30 June 2010Available online 15 December 2010

KEYWORDS

Psoriasis;

Guidelines;

Saudi

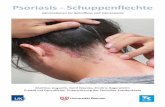

Abstract Psoriasis is a chronic, noncontiguous, inflammatory, multisystem disease with predomi-

nantly skin and joint manifestations affecting approximately 2% of the population. There is a

genetic predisposition to psoriasis and has tendency to wax and wane with flares related to systemic

or environmental factors, including life stress events and infection.

Majority of patients with psoriasis have limited disease (5% body surface area involvement) and

can be treated with topical agents, which generally provide a high efficacy-to-safety ratio.

To optimize the topical treatment of psoriasis in Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Society of Dermatology

and Dermatologic surgery (SSDDS) have initiated a project to develop guidelines for the manage-

ment of psoriasis. The guidelines are based on German and American one with subsequent discus-

sion with experts in the field; they have been approved by a team of dermatology experts.ª 2010 King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Contents

1. Recommendations for topical treatments in treatment of psoriasis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

2. Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

2.1. Before use of this guideline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72.2. Topical treatments for psoriasis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72.3. Corticosteroids . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72.4. Vitamin D analogues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.5. Combination of calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate ointment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

2.6. Calcineurin inhibitors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.7. Salicylic acid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102.8. Anthralin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102.9. Coal tar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

2.10. Emollient . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

3. Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1. Recommendations for topical treatments in treatment of

psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic disease, affecting approx-

imately 0.3–2.5% of the population (Plunkett and Marks,1998). Plaque psoriasis is the most common form, accountingfor approximately 90% of cases. The disease is usually chronic

and persistent, although up to 50% of patients may enterspontaneous remission for varying periods of time.

Psoriasis has a significant impact on patient quality of

life. The social and psychological impact is considerable.Psoriasis is not considered a life-threatening disease, but itis well established that those patients may experience arange of psychosocial difficulties, including elevated levels

of anxiety, depression, and worry (Richards and Fortune,2006).

The etiopathogenesis of psoriasis is still not fully under-

stood and involves a complex interaction of genetic and

Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management of psoriasis from American and German guidelines 7

environmental factors. Psoriasis was originally thought to be

a keratinisation disorder, but now substantial evidenceindicates that different components of the innate- andacquired-immunity (T cells, dendritic cells, and inflammatorycytokines) are critically involved in initiating and maintaining

the inflammatory response (Tagami and Aiba, 1997; Jullien,2006).

There is no cure for psoriasis; therefore, the aim of treat-

ment is to minimize the extent and severity of the disease tothe point at which it no longer substantially disrupts the pa-tient’s quality of life (Fairhurst et al., 2005).

Topical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for mild tomoderate psoriasis and often the initial treatment for severepsoriasis (Ashcroft et al., 2000).

About 80% of patients with psoriasis are treated topically(Peeters et al., 2005). Patients treated with phototherapy orsystemic agents, including biological agents, can also be man-aged with topical agents as adjunctive therapy (Guenther et al.,

2004).First-line therapy of psoriasis usually consists of topical

agents, such as emollients, tar, dithranol, corticosteroids and

vitamin D3 analogues. In cases of severe, extensive psoriasis,where topical therapy is either impractical or not sufficientlyeffective, phototherapy or systemic treatment may be war-

ranted at the outset.The majority of patients with psoriasis have limited disease

(<5% body surface area involvement) and can be treated withtopical agents, which generally provide a high efficacy-to-

safety ratio.In this guideline of care for psoriasis, we discuss the use of

topical medications for the treatment of psoriasis. We will dis-

cuss the efficacy and safety as well as offer recommendationsfor the use of topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues,tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, salicylic acid, anthralin, coal tar,

as well as combination therapy.

Table 1 Recommendations for topical corticosteroids.

Indication Plaque-type psoriasis

Initial dose 1–2 times per day

Maintenance dose Gradual reduction following onset of e

Duration of dosing – Should be initiated and monitored b

– For clobetasol and halobetasol, ma

2 weeks

Expected response After 1–2 weeks

Short-term results Highly potent agents have greater effica

Long-term results – True efficacy and risks associated w

duration

– Tachyphylaxis, while not demonstra

given patient

– Combination with other topical an

effects

Adverse drug reaction – Local – skin atrophy, telangiectasia

– Systemic – hypothalamic–pituitary–

in a large BSA (>30%)

Contraindication Skin infections, rosacea, perioral derma

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy Category C

Nursing Unknown safety

Pediatric use Because of the increased skin surface/b

systemic effects secondary to enhanced

children mid-potent steroids could be s

2. Method

A work group of expert dermatologists from different loca-

tions in Saudi Arabia set to determine the scope of the guide-line and to identify best data from American Academy ofDermatology (AAD) (Menter et al., 2009) and German guide-line (Nast et al., 2007) and adopted it according to team expe-

rience. So we have utilized expert opinion to generate thisclinical guideline.

2.1. Before use of this guideline

This guideline is intended for dermatologists in private

and government hospitals as well as for other specialties in-volved in the treatment of psoriasis. All physicians followthe recommendations contained in this guideline under their

own risk.

2.2. Topical treatments for psoriasis

Topical therapy forms the cornerstone in the management ofpsoriasis. Of significant value as monotherapy in mild to mod-erate psoriasis, it is used predominantly as adjunctive therapy

in moderate and severe forms of the disease. These are medi-cines in creams, ointments and lotions that are applied to theskin and scalp. There are a number of different approaches

possible. Here are some of the most common topicaltreatments.

2.3. Corticosteroids

Topical steroids are the most commonly prescribed medicinefor psoriasis. They are the primary treatment strategy for most

mild to moderate cases of psoriasis.

ffect

y dermatologists

ximal weekly use should be 25 g or less short-term treatment max.

cy than less potent agents

ith long-term use are unknown as most clinical trials are of short

ted in clinical trials, may affect the long-term results achieved in a

d variations in dosing schedules may lessen risk of long-term side

, striae, purpura, contact dermatitis, rosacea

adrenal axis suppression with high potency topical steroid and usage

titis

ody mass ratio, the risks to infants and children may be higher for

absorption. Growth retardation is also a potential concern. In

ufficient. Caution especially on the face.

8 A.A. Al Raddadi et al.

The mechanisms of action of corticosteroids include anti-

inflammatory, anti proliferative, immunosuppressive, andvasoconstrictive effects. These effects are mediated throughtheir binding to intracellular corticosteroid receptors and reg-ulation of gene transcription of numerous genes, particularly

those that code for proinflammatory cytokines (Cornell andStoughton, 1985).

Topical corticosteroids come in different strengths designed

for use on different parts of the body. Stronger potency ste-roids might be necessary for tough to treat patches of psoriasison the elbows or knees. Weaker formulas are good for more

sensitive skin on the face or groin.Steroids can cause side effects, such as thinning of the skin,

changes in the skin color, bruising, and dilated blood vessels.

Occlusion may increase these side effects (Koo and Lebwohl,1999; Pierard et al., 1989).

Recommendations for the use of topical corticosteroids areshown in Table 1.

2.4. Vitamin D analogues

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D3 analogue that is as potent as cal-citriol in inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing cell differen-tiation in vitro but is at least 100 times less active than

calcitriol in its effect on calcium metabolism in rats (Binderupand Bramm, 1988). During the last decade, calcipotriene hasemerged as an effective topical therapy for psoriasis (Kragballeet al., 1988, 1991; Highton and Quell, 1995; Lea and Goa,

1996).The mechanism of action of the vitamin D analogues in pso-

riasis is believed to be mediated by their binding to vitamin D

receptors, which leads to both the inhibition of keratino-cyte proliferation and the enhancement of keratinocytedifferentiation.

Irritation is the most common adverse event associated withcalcipotriene use occurring in 15–25% of patients, it maynecessitate withdrawal of treatment (Lea and Goa, 1996).

Recommendations for the use of vitamin D analogues areshown in Table 2.

2.5. Combination of calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionateointment

This new two-compound ointment is a combination of calci-

potriol 50 lg/g and betamethasone dipropionate 0.5 mg/g in

Table 2 Recommendations for vitamin D analogues.

Indication Plaque-type psoriasis

Initial dose Twice daily to affected areas, maximum 30

Maintenance dose Twice daily up to 100 g/weeks for up one

Duration of dosing 6 weeks

Expected response After 1–2 weeks

Response rate 30–50% of patients demonstrated marked

Adverse drug reaction Skin irritation (reddening, itching, burning

Contraindication – Reversible elevation of serum calcium –

– Causes photosensitivity, but no contrai

Drug interaction – Drugs which elevate the calcium levels

– No concomitant use of topical salicylic

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy Category C

Nursing No information on excretion in breast mil

Pediatric use Appears to be safe between ages 2–14 year

a single vehicle (5% polyoxypropylene-15-stearyl ether)

achieving optimal delivery of both drugs in an active state intothe skin (Simonsen et al., 2004), without affecting each other’sabsorption (Hansen et al., 2001; Guenther, 2005) and it is sta-ble and active for more than 2 years at room temperature

(Traulsen, 2004).The combination of calcipotriol with a corticosteroid im-

proves efficacy and decreases skin irritation. Two studies

showed that the administration of the combination of calcipot-riol and betamethasone dipropionate for a 4-week period im-proved keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation (Van

Rossum et al., 2001; Vissers et al., 2004), and inflammatorycharacteristics (Vissers et al., 2004). Also this new two-compound ointment induces a steroid-sparing effect in long-

term treatments and thereby reduces the risk of skin atrophyand skin thickness (Traulsen and Hughes-Formella, 2003),stretch marks, telangiectasia, rebound phenomenon, andtachyphylaxis.

Calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate combinationointment used once daily is well tolerated and more effectivein treatment of psoriasis than either active constituent used

alone (Kaufmann et al., 2002). Calcipotriol/betamethasonedipropionate has been shown to be effective in mild- to mod-erate psoriasis. It has been shown to be safe and effective in

the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris.Recommendations for the use of vitamin D analogues are

shown in Table 3.

2.6. Calcineurin inhibitors

Tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream are approved in

the United States for treatment of atopic dermatitis. Tacroli-mus and pimecrolimus are both calcineurin inhibitors andfunction as immunosuppressants (Reynolds and Al-Daraji,

2002). Calcineurin inhibitors function by blocking the synthe-sis of numerous inflammatory cytokines that play an impor-tant role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

In the treatment of psoriasis, the topical use of tacrolimusand pimecrolimus has promise (Ruzicka et al., 2003). How-ever, neither medication has yet to be approved by the FDAfor this indication.

Neither tacrolimus ointment (Lazarous and Kerdel, 2002)nor pimecrolimus (Gupta and Chow, 2003) cream appeareffective for treating plaque-type psoriasis when simply applied

as commercially available.

% of the body surface

year in intermitting use

improvement to clearance of the lesions after 4–6 weeks

)

more likely to occur in patients treated with greater than 100 g/wk

ndications to combining with UVB phototherapy

(thiazide diuretics).

acid preparations (Inactivation)

k; pregnant and nursing mothers were excluded from clinical studies

s with maximum 50 g/week

Table 3 Recommendations for topical combination of calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate ointment.

Indication Plaque-type psoriasis

Initial dose Once daily

Maintenance dose Once daily. Maximum dose: 15 g per day, 100 g per week

Duration of dosing 4 weeks. After this period, repeated treatment with calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate ointment can be

initiated under medical supervision in an as needed base

Expected response 4–8 weeks

Response rate – According to one clinical trial, patients treated with topical ointment achieved an average PASI reduction

of 71.3% at week 4 of treatment. In the same clinical trial, patients achieved an average PASI reduction of

39.2%. after only one week of treatment

– A 52-week clinical practice dosage study showed 70% to 80% of patients treated with Calcipotriol/beta-

methasone dipropionate ointment monotherapy achieving clear or almost clear status with no drug-

related serious adverse events, such as HPA-axis oppression or striae when used on as-needed basis

Contraindication/

adverse drug reaction

Local: Common undesirable effects are pruritus, rash and burning sensation of skin. Uncommon undesirable

effects are skin pain or irritation, dermatitis, erythema, exacerbation of psoriasis, folliculitis and application

site pigmentation changes. Pustular psoriasis is a rare undesirable effect

Systemic: Very rarely systemic effects after local application of the ointment may appear, such as

hypercalcaemia from the calcipotriol or inhibition of the adrenal cortex from the corticosteroid

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy Category C

Nursing Betamethasone passes into breast milk but risk of an adverse effect on the infant seems unlikely with

therapeutic doses. There are no data on the excretion of calcipotriol in breast milk. Caution should be

exercised when prescribing combining topical treatment to women who breast feed. The patient should be

instructed not to use treatment on the breast when breast feeding

Pediatric use Children and adolescents below 18: not recommended

Table 4 Recommendations for topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.

Indication No FDA-approved indications for psoriasis; primary indications for off-label use are for facial and

intertriginous psoriasis

Initial dose Pimecrolimus cream: 2·/dayTacrolimus ointment: 1–2·/day (use on face start with 0.03%, later increase to 0.1%)

Maintenance dose Individualized

Duration of dosing No duration of course is specified

Expected response Within 2 weeks

Response rate – Plaque psoriasis: Not generally effective

– Intertriginous and facial psoriasis: 65% of patients treated with tacrolimus 0.1% ointment were clear or

almost clear after 8 weeks of therapy compared with 31% of patients treated with placebo; 71% of the

patients treated with pimecrolimus 0.1% cream were clear or almost clear after 8 weeks of therapy as com-

pared with 21% of patients treated with placebo

Adverse drug reaction/

contraindication

– Most common side effect for both medications is burning and itching

– There are no specific contraindications/adverse reactions for psoriasis

– A controversial lymphoma ‘‘black box’’ warning has been issued by the FDA

Drug interaction Do not combine with phototherapy

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy Category C

Nursing Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are found in human milk and are not recommended for nursing mothers

Pediatric use Topical tacrolimus (0.03%) and topical pimecrolimus are approved for patients 2 years of age or older for

atopic dermatitis

Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management of psoriasis from American and German guidelines 9

Occlusion makes topical tacrolimus (Remitz et al., 1999)and pimecrolimus (Paul et al., 2000) more effective in treatingpsoriasis, suggesting that there was a lack of penetrationthrough the thick psoriatic plaque. This led to the concept of

utilizing the topical calcineurin inhibitors in thinner skin areassuch as facial and intertriginous psoriasis with no evidence ofresultant skin atrophy as compared with the use of topical cor-

ticosteroids in these regions.

The most common side effect for both medications is burn-ing and itching that generally reduces with ongoing usage andcan also be mitigated by not applying immediately after bath-ing. This side effect appears to be more significant in patients

treated with tacrolimus ointment as compared with patientstreated with pimecrolimus cream.

Recommendations for the use of topical tacrolimus and

pimecrolimus are shown in Table 4.

Table 5 Recommendations for salicylic acid.

Indication For localized psoriatic lesions less than 10%

For hyperkeratotic area

No specific FDA indication

Initial dose 2–10% x/daily

Maintenance dose –

Duration of dosing 2–4 weeks

Expected response – Data are limited on salicylic acid used alone

– Comparator study of tacrolimus and salicylic acid versus tacrolimus alone in small study (N= 24) of pso-

riasis patients with 10% BSA revealed improved efficacy with addition of salicylic acid. Comparator study

of 408 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis treated with mometasone and salicylic acid versus

mometasone alone for 3 weeks; psoriasis severity index measures erythema, indurations, and scaling

showed the combination of mometasone furoateesalicylic acid to be more effective than mometasone

furoate alone

Adverse drug reaction/

contraindication

Systemic absorption, although rare, can occur, especially when applied to more than 20% of BSA or in

patients with abnormal hepatic or renal function

Drug interaction Do notcombine salicylic acid with other salicylate drugs and also with vitamin D3 analogues

Salicylic acid decreases the efficacy of UVB phototherapy because of a filtering effect and should not be

used before UVB phototherapy

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy/nursing Appears to be a safe choice for the control of localized psoriasis in pregnancy

Pediatric use Because of greater risk of systemic absorption and toxicity, salicylic acid should be avoided in children

10 A.A. Al Raddadi et al.

2.7. Salicylic acid

Keratolytic agent Salicylic acid is the most widely used kerat-

olytic agent in psoriasis. It softens the scaly layers of psoriaticplaques and eases their removal. It is applied to palms, solesand scalp in concentrations of 2–10%. Salicylic acid is espe-cially useful in combination with corticosteroids to enhance

penetration and improve clinical efficacy (Federman andFraelish, 1999).

Salicylic acid is an irritant and, when used extensively at

high concentrations, can lead to salicylate toxicity.Recommendations for the use salicylic acid are shown in

Table 5.

2.8. Anthralin

Anthralin[1,8-dihydroxy-9(10H)-anthracenone, dithranol] wasfirst synthesized as a derivative of chrysarobin, prepared fromthe araroba tree, and is an established, safe, and effective top-ical treatment for psoriasis (Marsden et al., 1983).

Table 6 Recommendations for anthralin.

Indication Psoriasis vulgaris

Initial dose – Begin with 0.5% or lower concentratio

– 1% preparation for short-contact thera

Maintenance dose Not recommended for maintenance therap

Duration of dosing 4–6 weeks

Expected response Limited placebo-controlled trial data, but

more potent topical corticosteroids or vita

Response rate After 2–3 weeks

Adverse drug reaction – Most common side effects are skin irrit

of skin irritation, it is important to avo

Contraindication – Acute erythrodermic form of psoriasis

Drug interaction Photosensitizing drugs with dithranol may

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy/nursing Category C

Pediatric use Use with caution

It is one of few topical treatments to induce clearance ofpsoriatic plaques, leading to a period of remission, althoughits widespread use is limited by local irritation and staining.Anthralin inhibits proliferation of mouse and human keratino-

cytes as well as psoriatic keratinocytes in vivo (Hayden et al.,1994; Baxter and Stoughton, 1970), but its mechanism of ac-tion in psoriasis remains incompletely understood and its

molecular target(s) are unknown.The most common side effects of anthralin are skin irrita-

tion and staining of lesional and adjoining skin, nails, clothing,

and other objects with which patients come into contact.Recommendations for the use of topical anthalin are shown

in Table 6.

2.9. Coal tar

Coal tar is produced by the primary condensation during cor-

bonization of coal (Gruber et al., 1970). In 1931 Goeckermanpopularised his therapy of coal tar in psoriasis (Goeckerman,1931). Although the mechanism of action of coal tar is not well

n for long term therapy

py, with increasing concentration over time as tolerated

y

as monotherapy, anthralin appears to have lower efficacy than

min D derivatives

ation and staining of the skin and other touching objects. Because

id contact with surrounding normal skin

vulgaris, pustular psoriasis

increase their photosensitizing effect

Table 7 Recommendations for coal tar.

Indication Used in the treatment of psoriasis for more than 100 years

Initial dose 5–20% ointments or gels for topical therapy, daily

Maintenance dose No long term application or widespread use, clinical monitoring for potential development of skin carcinoma

is required

Duration of dosing Maximum 4 weeks

Expected response After 4–8 weeks, efficacy improves in combination with UV application

Response rate In double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of 324 patients with mild to moderate psoriasis comparing 1%

coal tar lotion with 5% coal tar extract, there was better improvement in both PASI score and Total Sign

Score in patients treated with 1% lotion than in 5% extract

Adverse drug reaction/

contraindication

– Often poorly tolerated by patients because of cosmetic issues, including staining of clothes and tar odor;

other potential adverse events include irritant contact dermatitis, folliculitis, and photosensitivity

– Coal tar is carcinogenic in animals, but in humans, there are no convincing data proving carcinogenicity,

and epidemiologic studies fail to show increased risk of skin cancer in patients who use coal tar

Drug interaction – Not known with topical use

– Attention should be paid to the concomitant intake of oral photosensitizing systemic drugs

Baseline monitoring None

Pregnancy/nursing Coal tar products are contraindicated during pregnancy and nursing

Pediatric use Use with caution

Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management of psoriasis from American and German guidelines 11

understood, it is known to suppress DNA synthesis by lessen-ing the mitotic labeling index of keratinocytes.

Many formulations of coal tar exist, and standardization of

these products is not always ideal. In one small study of 18 pa-tients, 5% liquor carbonis detergens was more effective thanits emollient base in the treatment of psoriasis (Kanzler and

Gorsulowsky, 1993).Side-effects of tar include folliculitis, irritation, and photo-

sensitivity. It should not be used on acutely inflamed skin, or

on pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis (Comaish, 1981).There is no definitive evidence of an increased risk of skin

cancer above the expected incidence for the general populationfrom the use of therapeutic tar (Pion et al., 1995; Pittelkow

et al., 1981).Education regarding the favorable safety profile and place in

therapy as a steroid-sparing adjunct may increase tolerance and

compliance of this excellent and underutilized topical therapy.Recommendations for the use of topical Coal tar are shown

in Table 7.

2.10. Emollient

Emollient therapy describes the application of moisturiserswhich are used to make the skin less scaly and dry. Often

Table 8 Recommendations for emollient.

Indication The use of emollients represents an internationally

accepted standard adjunctive therapeutic

approach to the treatment of psoriasis

Dosing Applied once to three times daily

Efficacy Two controlled studies of aloe vera had conflicting

results

Contraindication

No known contraindications

Baseline

monitoring

None

Pregnancy/

nursing

Generally considered safe

Pediatric use Generally considered safe

the words emollient and moisturiser are used interchangeably.Emollients or moisturizers can act as an important adjunctivetherapy of topical treatment in psoriatic patients. The use of an

emollient can limit relapses after the end of corticosteroid ther-apy, and maintain the improvement obtained after 1 monthcorticosteroid therapy at clinical level (physician global assess-

ment) and skin dryness (Seite et al., 2009). There are numerousother non-medicated topical moisturizer compounds and for-mulations available; depending on the individual product, they

can be applied up to several times daily. The goal of treatmentwith these agents is to provide and retain moisture in the stra-tum corneum; these agents are thought to function by forminga film on the skin surface to help retain moisture. There are no

known contraindications to the use of these non-medicatedmoisturizers; the large majority of these agents are consideredsafe during pregnancy and lactation as well as for pediatric

use. Recommendations for the use of emollients are shownin Table 8.

3. Conclusion

Great advances have been made in the understanding of the

pathogenesis of psoriasis and this has led to the use of newtherapies for patients.

The aim of these guidelines is to help the dermatologist to

know more about different types of topical therapies and to re-duce toxicity and side effects. Topical therapies still have a vi-tal role to play in the management of psoriasis. The letter classof drugs possesses better efficacy and a better patient accept-

ability profile.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by LEO pharma under supervision

of Saudi Society of Dermatology and dermatologic surgery.We would like to thank Dr. Diamant Thaci for help in review-ing the American and German guideline for topical therapy forpsoriasis.

12 A.A. Al Raddadi et al.

References

Ashcroft, D.M., Li Wan Po, A., Griffiths, C.E., 2000. Therapeutic

strategies for psoriasis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 25, 2–10.

Baxter, D.L., Stoughton, R.B., 1970. Mitotic index of psoriatic lesions

treated with anthralin, glucocorticosteriod and occlusion only. J.

Invest. Dermatol. 54, 410–412.

Binderup, L., Bramm, E., 1988. Effects of a novel vitamin D

analog MC903 on cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro and

on calcium metabolism in vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol. 37, 889–895.

Comaish, J.S., 1981. Tar and related compounds in the therapy of 5.

Psoriasis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 6 (6), 639–645.

Cornell, R.C., Stoughton, R.B., 1985. Correlation of the vasocon-

striction assay and clinical activity in psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol.

121, 63–67.

Fairhurst, D.A., Ashcroft, D.M., Griffiths, C.E., 2005. Optimal

management of severe plaque form of psoriasis. Am. J. Clin.

Dermatol. 6 (5), 283–294.

Federman, D., Fraelish, C., 1999. Topical psoriasis therapy. Am. Fam.

Physician 59, 957–962.

Goeckerman, W.H., 1931. Treatment of psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol.

Syphilol. 24, 446–450.

Gruber, M., Klein, R., Foxx, M., 1970. Chemical standardization and

quality assurance of whole crude coal tar USP utilizing GLC

procedures. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 59, 830–834.

Guenther, L.C., 2005. Calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate:

daivobet/dovobet. Therapy 2, 343–348.

Guenther, L., Langley, R.G., Shear, N.H., et al., 2004. Integrating

biologic agents into management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a

consensus of the Canadian psoriasis expert panel. J. Cut. Med.

Surg. 8, 321–337.

Gupta, A.K., Chow, M., 2003. Pimecrolimus: a review. J. Eur. Acad.

Dermatol. Venereol. 17, 493–503.

Hansen, J. 2001. Mixing the unmixable. Verbal communication at

the Leo Satellite Symposium. 10th Congress of the European

Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; Oct 10–14; Munich,

Germany.

Hayden, P.J., Free, K.E., Chignell, C.F., 1994. Structure–activity

relationships for the formation of secondary radicals and inhibition

of keratinocyte proliferation by 9-anthrones. Mol. Pharmacol. 46,

186–198.

Highton, A., Quell, J., 1995. Calcipotriene ointment 0.005% for

psoriasis: a safety and efficacy study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 32,

67–72.

Jullien, D., 2006. Psoriasis physiopathology. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol.

Venereol. 20 (Suppl. 2), 10–23.

Kanzler, M.H., Gorsulowsky, D.C., 1993. Efficacy of topical 5%

liquor carbonis detergens vs. its emollient base in the treatment of

psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 129, 310–314.

Kaufmann, R., Bibby, A.J., Bissonnette, R., et al., 2002. A new

calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate formulation (Daivo-

bet�TM) is an effective once-daily treatment for psoriasis vulgaris.

Dermatology 205, 389–393.

Koo, J., Lebwohl, M., 1999. Duration of remission of psoriasis

therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 41, 51–59.

Kragballe, K., Beck, H.I., Søgaard, H., 1988. Improvement of

psoriasis by a topical vitamin D3 analogue (MC 903) in a

double-blind study. Br. J. Dermatol. 119, 223–230.

Kragballe, K., Gjertsen, B.T., de Hoop, D., Karlsmark, T., van de

Kerkhof, P.C.M., Larko, O., et al., 1991. Double-blind, right/left

comparison of calcipotriol and betamethasone valerate in treat-

ment of psoriasis vulgaris. Lancet 337, 193–196.

Lazarous, M.C., Kerdel, F.A., 2002. Topical tacrolimus Protopic.

Drugs Today (Barc) 38, 7–15.

Lea, A.P., Goa, K.L., 1996. Calcipotriol: a review of its pharmaco-

logical properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of

psoriasis. Clin. Immunother. 5, 230–248.

Marsden, J.R., Coburn, P.R., Marks, J., Shuster, S., 1983. Measure-

ment of the response of psoriasis to short-term application of

anthralin. Br. J. Dermatol. 109, 209–218.

Menter, A., Korman, N.J., Elmets, C.A., Feldman, S.R., Gelfand,

J.M., Gordon, K.B., Gottlieb, A., Koo, J.Y., Lebwohl, M., Lim,

H.W., Van Voorhees, A.S., Beutner, K.R., Bhushan, R.American

Academy of Dermatology, 2009. Guidelines of care for the

management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 3. Guide-

lines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with

topical therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 60 (4), 643–659.

Nast, A., Kopp, I., Augustin, M., Banditt, K.B., Boehncke, W.H.,

Follmann, M., Friedrich, M., Huber, M., Kahl, C., Klaus, J.,

Koza, J., Kreiselmaier, I., Mohr, J., Mrowietz, U., Ockenfels,

H.M., Orzechowski, H.D., Prinz, J., Reich, K., Rosenbach, T.,

Rosumeck, S., Schlaeger, M., Schmid-Ott, G., Sebastian, M.,

Streit, V., Weberschock, T., Rzany, B., 2007. German evidence-

based guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris (short

version). Arch. Dermatol. Res. 299, 111–138.

Paul, C., Graeber, M., Stuetz, A., 2000. Ascomycins: promising agents

for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases. Expert Opin.

Investig. Drugs 9, 69–77.

Peeters, P., Ortonne, J.P., Sitbon, R., et al., 2005. Cost-effectiveness

of once-daily treatment with calcipotriol/betamethasone

dipropionate followed by calcipotriol alone compared with tacalc-

itol in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 211, 139–

145.

Pierard, G.E., Pierard-Franchimont, C., Mosbah, T.B., Estrada, J.A.,

1989. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids. Acta Derm.

Venereol. (Stockh) 69 (Suppl. 151), 26–30.

Pion, I.A., Koenig, K.L., Lim, H.W., 1995. Is dermatologic usage of

coal 6. tar carcinogenic? A review of the literature. Dermatol. Surg.

21 (3), 227–231.

Pittelkow, M.R., Perry, H.O., Muller, S.A., et al., 1981. Skin cancer in

7. Patients with psoriasis treated with coal tar. A 25-year follow-up

study. Arch. Dermatol. 117 (8), 465–468.

Plunkett, A., Marks, R., 1998. A review of the epidemiology of

psoriasis vulgaris in the community. Australas. J. Dermatol. 39 (4),

225–232.

Remitz, A., Reitamo, S., Erkko, P., Granlund, H., Lauerma, A.I.,

1999. Tacrolimus ointment improves psoriasis in a microplaque

assay. Br. J. Dermatol. 141, 103–107.

Reynolds, N.J., Al-Daraji, W.I., 2002. Calcineurin inhibitors and

sirolimus: mechanisms of action and applications in dermatology.

Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 27, 555–561.

Richards, H.L., Fortune, D.G., 2006. Psychological distress and

adherence in patients with psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol.

Venereol. 20 (Suppl. 2), 33–41.

Ruzicka, T., Assmann, T., Lebwohl, M., 2003. Potential future

dermatological indications for tacrolimus ointment. Eur. J. Der-

matol. 13, 331–342.

Seite, S., Khemis, A., Rougier, A., Ortonne, J.P., 2009. Emollient for

maintenance therapy after topical corticotherapy in mild psoriasis.

JPExp. Dermatl. 18 (12), 1076–1078.

Simonsen, L., Hoy, G., Didriksen, E., et al., 2004. Development of a

new formulation combining calcipotriol and betamethasone dipro-

pionate in an ointment vehicle. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 30, 1095–

1102.

Tagami, H., Aiba, S., 1997. Psoriasis. In: Bos, J.D. (Ed.), Skin Immune

System (SIS). CRC Press LLC, 2, Boca Raton, New York, pp. 523–

530.

Traulsen, J., 2004. Bioavailability of betamethasone dipropionate

when combined with calcipotriol. Int. J. Dermatol. 43,

611–617.

Traulsen, J., Hughes-Formella, B.J., 2003. The atrophogenic potential

and dermal tolerance of calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate

oinment compared with betamethasone dipropionate ointment.

Dermatology 207, 166–172.

Adopted guidelines of care for the topical management of psoriasis from American and German guidelines 13

Van Rossum, M.M., van Erp, P.E.J., van de Kerkhopf, P.C., 2001.

Treatment of psoriasis with a new combination of calcipotriol and

betamethasone dipropionate: a flow cytometric study. Dermatol-

ogy 203, 148–152.

Vissers,W.H., Berends,M.,Muys, L., et al., 2004.The effect of the com-

bination of calcipotriol and betamethasone dipropionate versus both

monotherapies on epidermal proliferation, keratinization and T-cell

subset in chronic plaque psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 13, 106–112.