A Test of the Behavioral Perspective Model in the Context of an E-mail Marketing Experiment

Transcript of A Test of the Behavioral Perspective Model in the Context of an E-mail Marketing Experiment

The Psychological Record, 2013, 63, 295–308

The authors thank Bjarki Petursson, CEO at Zenter, and Edda in Reykjavik for access to databases that are used in the experiment. This research was supported by a grant (nr. 090660043) from the Icelandic Center for Research to Valdimar Sigurdsson.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Valdimar Sigurdsson, Reykjavik University School of Business, Reykjavik University, Menntavegur 1, Nautholsvik, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland. E-mail: [email protected] DOI:10.11133/j.tpr.2013.63.2.005

A TEST OF ThE BEhAvIORAL PERSPECTIvE MODEL IN ThE CONTExT OF AN E- MAIL MARkETING ExPERIMENT

Valdimar Sigurdsson, R. G. Vishnu Menon, Johannes Pall Sigurdarson, and Jon Skafti Kristjansson

Reykjavik University

Gordon R. FoxallCardiff University

An e- mail marketing experiment based on the behavioral perspective model was conducted to investigate consumer choice. Conversion e- mails were sent to two groups from the same marketing database of registered consumers interested in children’s books. The experiment was based on A- B- A- C- A and A- C- A- B- A withdrawal designs and consisted of sending B = utilitarian (economic/functional) and C = informational (social) advertising stimuli with a clear call for action. Key measurements consisted of individuals receiving the e- mail, opening it, clicking on a link, and buying the target books. Aggregated results showed that the informational stimuli were more successful in inducing consumers to open the e- mails whereas the utilitarian stimuli were beneficial in increasing buying behavior. Data for individual consumer behavior indicate possible stimulus control in the case of particular consumers and potentials for functional analysis. The results show different appropriateness of stimuli for shaping consumer responses online and possibilities for translational work in behavior analysis.Key words: e- mail, online behavior, behavioral perspective model, behavioral economics

Concerns have been raised about the relevance of behavioral economics and behavior analysis to natural, everyday behavior (e.g., Kunkel, 1987; Mace & Critchfield, 2010; Nevin, 2008; Woods, Miltenberger, & Carr, 2006) and that the time is right for an extension of theoretical explanations, concepts, and methods, demonstrating their importance (e.g., logue, 2002; Mazur, 2010). Keeping this in mind, we want to focus on the internet. The evolution of the internet has created of a world of choice and consumption behaviors and reciprocal innovative, motivational, and discriminative stimuli as well as reinforcing and punishing consequences. This area should be of importance to behavior analysts because the potential contribution of behavior analysis in understanding consumer choice online remains underdeveloped.

296 SigurdSSon et al.

There are only a few behavioral studies on online consumer behavior that are relevant from a behavioral economic perspective. Many of these studies made use of a simulated shopping environment. Among the initial studies, Rajala and hantula (2000) made use of a simulated internet mall to investigate the delay- reduction effects on foraging. This study made use of the foraging theory and extended the theory to include human purchase and consumption in postindustrial culture. diClemente and hantula (2003) extended the Rajala and hantula (2000) study by investigating the effects of exteroceptive cues on consumers’ sensitivity to time delay. The behavioral economic analysis conducted by C. Smith and hantula (2003) included a series of experiments across five virtual stores that assessed the influence of pricing on consumer preferences. The coherence between the effects of pricing and delay on consumer preferences was evident from the results, and the study also provided strong support for the argument that the price of goods contributes to total delay time to primary reinforcement. These studies, focusing on delay in online shopping, affirmed the conformity of individual consumption to the prediction of optimal foraging theory and delay reduction hypothesis. The study by Fagerstrøm (2010) introduced the concept of motivating operations (Mo) to the field of online consumer behavior and examined the motivating impact of antecedent stimuli on online purchasing. The results indicate that the concept of Mo is applicable to the analysis of the motivating impact of antecedent stimuli on consumer purchase behavior. in another study, Fagerstrøm, Arntzen, and Foxall (2011) investigated brand loyalty by arranging environmental contingencies in online stores. The study was conducted in a simulated online shopping environment where the participants purchased products from two different online stores. While there is much to admire and learn about the previous studies, there is also a significant concern. Most, if not all, of the studies have been done in a lab, based on scenarios where the experimenter has control over the conditions and the delivery of the reinforcements (Schwartz & lacey, 1988). in consumer marketing, the researchers have less control, budget effects can be very small, and competition between different behaviors can be fierce (lea, 1978; lea, Tarpy, & Weblay, 1987). This study seeks to bring the experiment to a natural setting, with less control, but with a more realistic situation.

Researchers studying consumer behavior in the marketplace probably have the least control over the environment of all those studying behavior economics. The control is higher in related fields, such as organizational behavior management, clinical psychology, or school psychology. in consumer marketing, the researchers have less control, budget effects can be very small, and competition between different behaviors can be fierce (lea, 1978; lea et al., 1987). The world of the internet is behavioral data- intensive, with many possibilities for detailed field experimental analysis and mathematical formulations. out of all the online communication tools, e- mail probably has had the most impact on consumer behavior. in effect, e- mail has become a widely adopted behavior modification platform, which is evident from the fact that the number of worldwide e- mail accounts is projected to increase from 2.9 billion in 2010 to over 3.8 billion in 2014 (E- Mail Statistics Report, 2010). E- mail marketing is considered to be one of the most personal forms of marketing, and for this reason it helps in building relationships. it is highly cost effective and easily measurable. E- mail has changed how, with whom, and about what people communicate; it is applied, effective, and international. Even though e- mail marketing and online shopping has increased over the years, there are still challenges to understand and predict consumer responses to e- mail marketing.

The empirical literature on e- mail marketing is limited and apparent. The knowledge of the effects of e- mail on consumer behavior is highly proprietary because it is conducted mostly by firms and therefore is not published. This is an underdeveloped field, with only a few published articles. The majority of the articles published in this area focus on studying consumer responses to e- mail marketing. Most of the experiments utilized attitudinal measures in their research settings, and no study was conducted from a behavioral point of view. Needless to say, none focused on individual analysis using single- subject designs. A brief literature review summarizes the past research in the area of e- mail marketing.

297A TesT of The BehAviorAl PersPecTive Model

Chittenden and Rettie (2003) identified the factors affecting the response rate in e- mail messages. The results showed that there is a significant correlation between the response rate and subject line, e- mail length, incentive, and the number of images. Zviran, Te’eni, and Gross (2006) showed that using color in e- mails makes a difference, and if it is used correctly, it can prompt the recipient to respond as the sender intended. Marinova, Murphy, and Massey (2002) analyzed permission e- mail marketing as a means of targeted promotion. They identified the factors that influenced the effectiveness of an e- mail permission marketing campaign, and results showed that personalization in e- mail messages is an ineffective method to generate desired customer responses. Merisavo and Raulas (2004) found that e- mail marketing had a positive impact on brand loyalty, and that recipients’ recommended the brand to their friends. Martin, Van durme, Raulas, and Merisavo (2003) studied consumer perceptions to e- mail advertising. The study also identified e- mail advertising factors that influence consumer visits to the company Web site and their bricks- and- mortar outlet. The results showed that the consumers were more likely to visit the company’s bricks- and- mortar store if they found the e- mails useful.

There has been, and is, only one systematic, long- term research study on consumer behavior and marketing in nonlaboratory settings from an operant perspective, and that is the consumer behavior analysis research program (Foxall, 2010). Consumer behavior analysis (CBA), the application of behavioral economics to the sphere of human consumer choice, particularly in the context of advanced marketing- oriented economies, attempts to redress the balance by exploring the nature of behaviorist explanation and its capacity to enlighten consumer research (Foxall, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2003). To explain consumer behavior in affluent environments is to locate it in space and time, at the intersection of a learning history and a current behavior setting (Foxall, 1998). This has led to the development of the behavioral perspective model (BPM) of consumer choice.

The BPM is built on the extensive empirical research results from applied behavior analysis on consumer behavior modification (e.g., Foxall, oliveira- Castro, James, yani- de Soriano, & Sigurdsson, 2006). The model offers consumer behavior analysts a conceptual and methodological system that makes it possible to analyze the interplay between consumer settings, learning history, and behavioral consequences (see Figure 1). The BPM is based on a three- term contingency and on drawing out a clear characterization of consumer behavior that can be observed, measured, and analyzed. The discriminative stimuli are produced by the interaction between the behavioral setting and the consumer’s learning history of consumption. A behavioral setting includes the temporal, physical, and social context within which action occurs. its bounds are determined by space and time and also by an entire sequence of associated behavior. For example, an e- mail is opened at a particular location and at a particular time (e.g., at home, in the morning). A setting, in this instance, is therefore a broader unit of possible discriminative stimuli than a situation. Sending an e- mail presents numerous situations in a marketer’s quest for a molecular successive approximation to buying behavior and to rebuying in the molar sense.

Utilitarian Reinforcment

Informational Reinforcement

Utilitarian Punishment

Informational PunishmentLearning History

Consumer Situation

Consumer Situation

Behavior

Consumer Behavior Setting

Figure 1. The behavioral perspective model (BPM) of consumer choice.

298 SigurdSSon et al.

Previous research has revealed and supported two types of consequences for consumer behavior (Foxall, 2010; yan, Foxall, & doyle, 2012a, 2012b), called utilitarian (incentives) and informational (performance feedback) in the BPM. it is the specification of the nature of the utilitarian and informational consequences available in the setting that completes the definition of the situation of purchase or consumption. utilitarian consequences (reinforcement/punishment and positive/negative) can be defined as an increase (or decrease) in operant behavior (such as money spent for a particular good or service) as a function of particular economic consequences. The consequences are tangible and include utilitarian reinforcers (or punishers), which stem from purchase, ownership, and consumption, or the removal and avoidance of negative utilitarian consequences, such as car failure. The concept in utility, in utilitarian reinforcement, is seen as it is usually used in economic analysis, where it generally means that products and services can give pleasure or satisfaction to consumers (Foxall, 1998). informational consequences (reinforcement/punishment and positive/negative) can be defined as an increase (or decrease) in operant behavior (e.g., money spent) as a function of a presentation of particular symbolic consequences. The consequences are not tangible themselves but are communicational and include informational reinforcers (or punishers) that stem from social status; vocal, written, and gestural responses; or the removal and escape of negative informational reinforcers.

The BPM also classifies consumer behavior into open and closed settings, where relatively open settings are those in which the contingencies cannot be accurately specified through unambiguous indemnification and manipulations of controlling stimuli. Based on these relative levels of utilitarian and informational reinforcement, the BPM classifies four operant classes of consumer behavior: accomplishment (high utilitarian and high informational reinforcement), hedonism (high utilitarian and low informational), accumulation (low utilitarian and high informational), and maintenance (low utilitarian and low informational; Foxall, 1992).

Mass marketing was one of the success stories of the 20th century. Firms aimed to maximize profits and market share by selling large quantities of goods to a maximum number of people. With the advent of the internet, the concept of mass marketing reached new heights by utilizing e- mail. however, now with many regulations in practice, unsolicited e- mails sent for direct marketing is against the law unless the recipient has agreed to receive the e- mail. Thus evolved the concept of permission marketing. The idea of permission marketing was first proposed by Godin (1999). According to this concept, consumers grant marketers explicit permission to send them promotional messages. Permission marketing suggests an evolution of direct marketing, particularly with e- mail. it combines databases of customers who agree to receive marketing messages with low- cost, customized e- mails that attempt to slice through the advertising clutter, attract increased customer support, and change behavior (Tezinde, Smith, & Murphy, 2002). Such an approach not only decreases the amount of data to be sent but also increases the success rate in opening the e- mails by the customer. hence, it is of high importance to study e- mail marketing from a functional analysis (see, e.g., Pierce & Epling, 1999) point of view with models that scrutinize behavior- environmental contingencies. Keeping this in mind, we conducted an e- mail marketing experiment based on the BPM, using single- subject research designs. The primary aim of this research was to extend the consumer studies in behavior economics into an open and affluent environment and thereby study the single- subject research designs in the marketplace and explore its future relevance to personalized marketing. The purpose of this study was to experimentally test interpretation of the BPM by evaluating the effects of utilitarian and informational e- mail stimuli/situations on the conversion rate of consumers interested in children’s books. The conversion rate in this case is the ratio of visitors who converted their e- mail views into a desired action (i.e., purchasing the books).

299A TesT of The BehAviorAl PersPecTive Model

Method

Participants, Setting, and ProductThe current research was conducted in collaboration with Zenter, an icelandic market

research firm that specializes in e- mail marketing. The participants were randomly selected consumers who were interested in children’s books and who had given prior permission to send e- mails regarding any offers related to these books. Furthermore, each participant had opted to be in the membership scheme of the company who published these books. The participants were randomly divided into two groups, Group 1 and Group 2. The first e- mail was sent to a sample of 7,265 people in Group 1 and 7,227 people in Group 2. The second e- mail had 6,532 people in Group 1 and 6,508 people in Group 2 (the number of members’ changes with time). The target product in the experiment was disney’s donald duck comic books.

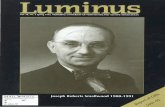

Six members from the e- mail list who bought the target books during the interventions were randomly selected for further experimental analysis at the individual consumer level (see Figure 2). These were consumer number 9652 (male, age 39), 2907 (female, age 41), 7816 (female, age 38), 11230 (female, age 62), 7472 (female, age 35), 11343 (female, age 38).

Response Definition and MeasurementFor each consumer in the experiment, the Zenter software recorded if the e- mails

were received and opened, if the consumer clicked on the uRl link to access the web shop, and the number of quantities sold of the target books. The number of clicks on other uRl links’ in the web shop and items bought was also monitored, as well as if consumers unsubscribed as members of the database after receiving an e- mail. All these measurements come in aggregated and simultaneously as they happen in a graphical format.

System validity and ReliabilityThe Zenter software was used to record the consumer responses. it had been tested

and practiced extensively for several months before the experiment. This means that deliverability of e- mails had been verified before, in accordance with best practices. Furthermore, to maximize the chances that the target e- mails would go into the inbox and in the appropriate format, the content was checked for spam (unsolicited commercial e- mail) filters, and the e- mails were sent to a few inboxes as a pretest.

Design and ProcedureThe members of the publishing house were divided into two groups; Group 1 received

the utilitarian e- mail first, but the informational e- mail was initially sent to Group 2. Therefore, the experiment was based on A- B- A- C- A and A- C- A- B- A withdrawal designs and consisted of sending B = utilitarian (economic/functional) and C = informational (social) advertising stimuli with a clear call for action. Separating the members of the publishing house into two groups with a different order of interventions was done to minimize threats to internal validity, attributable to the order of interventions, and to counterbalance the effects of external variables, such as the effects of sending the e- mail at a particular time. Furthermore, dividing the database into two groups gave more experimental comparisons that were supposed to control for extraneous variables, based on the assumption that such variables affect all of the experimental conditions. The baseline consisted of sales during days when the sales promotion attached to the e- mails was not in effect, to provide data on units sold of the target books in the absence of the e- mails.

The experiment (baseline and interventions) took place during March 15 to April 19, 2011. The baseline was taken for the first 7 days, but after that the e- mails were sent to the

300 SigurdSSon et al.

consumers. in the first intervention, Group 1 was sent the utilitarian stimuli (2 for 1—buy one book and get another one for free) whereas Group 2 got the informational message (if

Bought

Clicked

Opened

Response

Cons

umer

Res

pons

e

1 2 3 4 5 6 7E-mails Sent by the Publishing House

Customer No: 9652

No

Bought

Clicked

Opened

Response

Cons

umer

Res

pons

e

1 2 3 4 5 6 7E-mails Sent by the Publishing House

Customer No: 7472

No

Bought

Clicked

Opened

Response

Cons

umer

Res

pons

e

1 2 3 4 5 6 7E-mails Sent by the Publishing House

Customer No: 7816

No

Bought

Clicked

Opened

Response

1 2 3 4 5 6 7E-mails Sent by the Publishing House

Customer No: 11230

No

Bought

Clicked

Opened

Response

1 2 3 4 5 6 7E-mails Sent by the Publishing House

Customer No: 2907

No

Bought

Clicked

Opened

Response

1 2 3 4 5 6 7E-mails Sent by the Publishing House

Customer No: 11343

No

Disney

Other Books

Utilitarianstimuli

Utilitarianstimuli

Utilitarianstimuli

Utilitarianstimuli

Utilitarianstimuli

Utilitarianstimuli

Informationalstimuli

Informationalstimuli

Informationalstimuli

Informationalstimuli

Informationalstimuli

Informationalstimuli

Figure 2. Consumer behavior analysis for a sample of six consumers who bought the target item. Note. The blank space above the numbers denotes that the consumers received the e-mail but did not respond.

301A TesT of The BehAviorAl PersPecTive Model

you buy a book, we will give another one to charity). The sales promotion lasted for 8 days. After that, the second baseline was taken for the next 7 days, after which the second set of interventions was introduced, which lasted until April 12, 2011. in the second intervention, Group 1 received an informational message, and Group 2 received a utilitarian message. This was followed by another 7 days of baseline.

Finally, individual data for the six members that were selected for single- subject analysis are revealed (see Figure 2). We analyzed their responses to the interventions but also to previous e- mails from the publishing house. These e- mails were categorized as e- mails promoting (a) disney books and (b) other books.

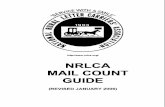

ResultsThe mean sales, standard deviation during each condition, and the effect sizes d

(McConville, hantula, & Axelrod, 1998) for the difference between the baseline (normal web- shop sales) and the experimental interventions for Groups 1 and 2 can be seen in Table 1. For statistical purposes, we combined the results from Groups 1 and 2 together and get a statistically significant main effect, F(1,17) = 6.321, p = .026. if the results are combined together for both groups, then sales for the utilitarian stimuli are (M = 2.78, SD = 4.37), and for the informational stimuli (M = .14, SD = .36). For consumers who responded to the e- mails, both types (utilitarian and informational stimuli) tend to induce maximum responses during the first 2 days after the e- mails were sent, as most consumers tend to look at their e- mails every day, or at least every other day. As a consequence, it is most helpful to look at the time series generated by the experimental design. Figure 3 shows the number of orders and amount bought for all conditions in the case of both experimental groups. Based on the results from the experiment, it is apparent from the steady state zero sales during all baseline conditions that the members of the publishing house are more likely to buy when prompted with an e- mail.

For Group 1, during the “2 for 1” conditions, a total of 830 consumers (12.69% of the total consumers who received the e- mail) opened the e- mail, 86 consumers clicked on the image/link, and seven consumers ordered the books. out of this, six consumers bought two books for the price of one, and one consumer bought 13 books. in total, 25 books were sold to Group 1 during this condition. When this e- mail was sent, eight people from Group 1 opted out of the e- mail list, but it is quite common and considered normal that some individuals opt out with every e- mail that is sent. Group 1 received the offer, “you buy we give” as a second intervention. A total of 1,282 consumers opened the e- mail (19.63% of the total people who received the e- mail), 64 consumers clicked on the image/link, and none ordered the target books. during this intervention, nine people opted out of the e- mail list.

For Group 2, during the “you buy we give” conditions, the number of consumers who opened the e- mail increased to 1,431 (21.92% of the total consumers who received the e- mail), 75 consumers clicked on the image/link, and two consumers ordered the books. it was also noted that 20 people from Group 2 opted out of the e- mail list during the first intervention. Group 2 received the offer “2 for 1” in the second intervention. A total of 716 consumers opened the e- mail (11% of the total people who received the e- mail), 80 consumers clicked on the image/link, and seven consumers ordered the target books, bringing the total sales to 14. during this intervention, 12 people opted out.

From the experiment, we noticed that the open rate, during the “you buy we give” (informational) intervention, 19.63% and 21.92% for Group 1 and 2, respectively, was on par with the media and publishing industry average of 20.9% (Silverpop, 2012). in the case of “2 for 1” (utilitarian) intervention, however, the open rate was much lower (12.69% and 11% for Groups 1 and 2, respectively) than the industry average. This suggests that participants tend to open those messages that have informational content more than those with utilitarian content. however, when coming to actual clicks on the messages opened (click- to- open rate), the results are somewhat different. in Group 1 and 2, the click- to- open rate was 10.36% and 11.17%, respectively, for “2 for 1” intervention as compared to 4.99%

302 SigurdSSon et al.

and 5.24% for “you buy we give” intervention. Even though the utilitarian content has a higher click- to- open rate than the informational content, it is much lower than the industry

Figure 3. Number of orders received and actual sales for Groups 1 and 2.

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

15-M

ar

17-M

ar

19-M

ar

21-M

ar

23-M

ar

25-M

ar

27-M

ar

29-M

ar

31-M

ar

02-A

pr

04-A

pr

06-A

pr

08-A

pr

10-A

pr

12-A

pr

14-A

pr

16-A

pr

18-A

pr

Freq

uenc

ies

Freq

uenc

ies

Days

Baseline You Buy We Give Baseline 2 for 1 Baseline

Baseline 2 for 1 Baseline You Buy We Give Baseline

Group 1 Baseline

Number of Orders

Quantity Sold

Group 2 Baseline

Number of Orders

Quantity Sold

303A TesT of The BehAviorAl PersPecTive Model

average of 24.20% (Silverpop, 2012). This is probably because the study conducted was limited to children’s books and did not include other categories in media and publishing, such as fiction books or newspapers.

We studied individual responses to the e- mails sent in the experiment and identified that those consumers who bought the target books did so either when they received utilitarian or informational stimuli. Figure 2 reveals data for a sample of six consumers. Their responses to the two interventions (utilitarian and informational) were analyzed in addition to the five e- mails previously sent by the publishing house. This data reveal that the consumers generally did not respond to e- mails that were not promoting disney books because only customer number 9652 opened all three e- mails that were sent about other books. The utilitarian and informational e- mails were more successful than previous e- mails sent by the publishing house. For all six consumers, both types were successful in getting them to open and click on the e- mail, but only one type (either utilitarian or informational) is strong enough to facilitate buying behavior.

DiscussionThis study has emphasized the use of the BPM as a tool to understand consumer’s

responses to e- mail marketing. The results showed that the opening rate of the informational message (you buy we give) was double than that of the utilitarian message (2 for 1). But when it came to sales, the utilitarian reinforcement was a much stronger force, inducing consumers to purchase. According to the BPM, the consumption of products and services that are entirely entertainment- based, such as children‘s books, tends to belong to the category of relatively open, high utilitarian but low informational reinforcement. This interpretation is confirmed experimentally by the data from the experiment. in line with the data presented here (baseline sales), the appearance of the publishing house’s web shop does not generate any buying behavior because consumers spend their scarce time and money elsewhere. in such open settings as online and offline retailing, it might be relatively easy to predict consumer behavior based on the consumer’s recent buying history, as consumption tends to be habitual. however, identifying contingencies in such an open setting with unambiguous indemnification might be a difficult task without attempts to close the setting (e.g., lowering the number of possible reinforcers) and manipulating the controlling stimuli. The intention of e- mail marketing does exactly that: it tries to close the setting with possible motivational and/or discriminative stimuli (signaling utilitarian or informational consequences) and shape consumer responses through the sales pipeline (from opening to buying).

For consumers who responded to the e- mails containing both utilitarian and informational stimuli, the maximum number of responses was recorded during the first 2 days after the e- mails were sent, as most consumers tend to look at their e- mails every day, or at least every other day. The current study reveals that the e- mail stimuli increases response probability, and we identify that those customers who bought a copy of the book series did so under a particular condition, meaning that they bought only when they received the utilitarian stimuli but not under the informational condition, and vice versa. The findings also generalize from one group to another, and the order of interventions does not seem to impact the results. This strengthens the appropriateness of further uses of single- subject research designs and functional analysis in e- mail marketing experiments. however, as the particular intervention was not reintroduced for each individual, this could be tested further. Prompting seems to be necessary, but further identification of individual learning histories (more time series in the Zenter system) and experimental analysis with e- mails is necessary to better examine the contingencies. it is apparent that further single- subject research could also examine marketing segmentation based on responses to different or combined e- mail stimuli and products instead of on verbal statements from consumers.

304 SigurdSSon et al.

in this experiment, the impact of utilitarian reinforcement is higher than that of informational reinforcement, probably because the utilitarian reinforcement provides a more tangible and immediate economic benefit; that is, the consumers get more of the product without having to spend extra money (greater amount of reinforcement without additional response). on the other hand, the informational reinforcement signaled (e.g., positive communications from others or being a good consumer) is more difficult to grasp. This is an unusual stimulus in this setting, and it is mostly dependent on peer- to- peer communications. in an online environment such as this experiment, the informational stimuli are not high enough to elicit a response, as the social value derived from such a response is rather low, abstract, and possibly delayed. however, this type of stimuli might work in different situations, such as when consumers receive points for clicking the advertisement. Further research is required to verify such a possibility. The main prediction of the BPM that needs to be tested is the statement that a combination of utilitarian and informational reinforcement will deliver the best result (e.g., Foxall et al., 2006).

Another possible research area is to identify the factors needed for more profound effects of antecedents and/or reinforcement for socially important behavior online, such as donating to charity. The uses of e- mail and other online tools in applied behavior analysis should be examined, for example, exploring the usefulness and indicating best practices for education or therapy.

This study extends the domain of behavior analysis into e- mail marketing and buying behavior in the affluent and nonlaboratory online setting. We have technically demonstrated the use of withdrawal designs to test the effects of different e- mail stimuli on consumer responses, and the research is theoretically driven by the BPM. Consumer behavior analysis tends to be performed in open settings, with many stimuli and possible reinforcers, where the researcher has no kind of authority over the behavior of the human organism. This kind of work has mainly been conducted in traditional brick- and- mortar retailing settings, with panel data (oliveira- Castro, Foxall, & Schrezenmaier, 2006) or in- store experiments (e.g., Sigurdsson, Saevarsson, & Foxall, 2009). however, the previous works have in common the inability to study individual consumer behavior experimentally, as panel data are correlational and in- store experiments are performed on groups of consumers. in this study, however, there are experimental interventions and opportunities to study the responses of individual consumers. With panel data, the researcher can assess individual buying behavior history, but with the limitations of only studying what is; that means not being able to verify and study environmental arrangements that are not present. This experimental analysis of individual consumer behavior is now possible, and with more precision than before. Skinner made behavior analysis possible by focusing on the behavioral techniques that this new science had to offer. it is because of the new online analytical techniques that are being developed that further advancement and popularity of behavior analysis is possible. The limitation of this study was the restricted amount of data. The analysis was restricted to only one type of product and the forms of utilitarian and informational stimuli. Future research should examine longer periods of time series with single- subject research, with different interventions replicated and, perhaps, more products or behaviors (e.g., donations or learning).

There is a lack of communication between the behavioral economics and applied fields of consumer behavior because economic theorizing is often unconcerned with what is going on in the real world (Coase, 1998; V. l. Smith, 1989; Thaler, 2000). Although the problems of academics and practitioners are not always the same, they share an interest in consumer and marketer behavior. Managers have various data and possibilities for experimentation that could be used to extend the domain of a theory or behavioral principles to nonartificial markets. Behavioral scientists have, by contrast, theories and methods that can enhance the value of the data for better marketing interventions and further theoretical and methodological testing. Academics are also often better able to disseminate the results. Collaboration between academics and practitioners is important, to

305A TesT of The BehAviorAl PersPecTive Model

keep the behavioral economic research both rigorous and relevant. This study is our first step of many in that direction, for a more complete investigation of the interaction of consumers with the economic and social environment. our next research steps will be to tap into a much more detailed analysis of consumer behavior in terms of the competition of stimuli and behavioral consequences for consumers’ observing, clicking, and other contingency- shaped and rule- governed behavior.

To our knowledge, no rigorous analysis based on a sound theoretical foundation has been applied to analyze consumer reactions to e- mail marketing. Rather, marketers and those running e- mail marketing programs have accepted marketing’s status quo ante of the technologies for understanding e- mail marketing, in terms of statistical social scientific data, in terms of classifying e- mail as work related or personal, or in terms of generating awareness or loyalty. We interpret that these concepts and measurements are too vague and that a much more detailed analysis of consumer behavior is both needed and possible in this realm. As with choices of marketing terms and metrics, it is a classic case of institutional imprinting that has gone unchallenged and unquestioned. in the meantime, behavioral economics and marketing science technology have advanced to the point at which single- subject experimental techniques need to be explored in the affluent online environment, to test behavioral principles gained in the course of rigorous experimental investigations. in the age of the increasing value of personalized marketing and objective clickstream data for e- mails and Web sites, it is time to explore further the research paradigm, as experimental analysis of consumer choice and preference is possible in the marketplace.

ReferencesChiTTENdEN, l., & RETTiE, R. (2003). An evaluation of e- mail marketing and factors

affecting response. Journal of Targeting Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 11, 203–217. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740078

CoASE, R. (1998). The new institutional economics. American Economic Review, 88, 72–74. doi:10.1080/14719030000000027

diClEMENTE, d. F., & hANTulA, d. A. (2003). optimal foraging online: increasing sensitivity to delay. Psychology and Marketing, 20, 785–810. doi:10.1002/mar.10097

E- MAil STATiSTiCS REPoRT. (2010). Executive summary. Retrieved from www.radicati.com/FAGERSTRøM, A. (2010). The motivating effect of antecedent stimuli on the web shop:

A conjoint analysis of the impact of antecedent stimuli at the point of online purchase. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 30, 199–220. doi:10.1080/01608061003756562

FAGERSTRøM, A., ARNTZEN, E., & FoxAll, G. R. (2011). A study of preferences in a simulated online shopping experiment. The Service Industries Journal, 31, 2603–2615. doi:10.1080/02642069.2011.531121

FoxAll, G. R. (1992). The behavioral perspective model of purchase and consumption: From consumer theory to marketing practice. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 20, 189–198. doi:10.1007/BF02723458

FoxAll, G. R. (1998). Radical behaviorist interpretation: Generating and evaluating an account of consumer behavior. The Behavior Analyst, 21, 321–354.

FoxAll, G. R. (2001). Foundations of consumer behavior analysis. Marketing Theory, 1(2), 165–199. doi:10.1177/147059310100100202

FoxAll, G. R. (2002). Consumer behavior analysis: Critical perspectives in business and management. london: Routledge.

FoxAll, G. R. (2003). The behavior analysis of consumer choice: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 581–588. doi:10.1016 /S0167-4870(03)00002-3

306 SigurdSSon et al.

FoxAll, G. R. (2010). Interpreting consumer choice: The behavioral perspective model. New york, Ny: Routledge.

FoxAll, G. R., oliVEiRA- CASTRo, J. M., JAMES, V. K., yANi- dE SoRiANo, M., & SiGuRdSSoN, V. (2006). Consumer behavior analysis and social marketing: The case of environmental conservation. Behavior and Social Issues, 15, 101–124.

GodiN, S. (1999). Permission marketing: Turning strangers into friends, and friends into customers. New york, Ny: Simon & Schuster.

KuNKEl J. h. (1987). The future of JABA: A comment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20, 329–333. doi:10.1901/jaba.1987.20-329

lEA, S. E. G. (1978). The psychology and economics of demand. Pychological Bulletin, 85, 441–466. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.3.441

lEA, S. E. G., TARPy, R. M., & WEBlAy, P. (1987). The individual in the economy: A survey of economic psychology. Cambridge, uK: Cambridge university Press.

loGuE, A. W. (2002). The living legacy of the harvard Pigeon lab: Quantitative analysis in the wide world. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 77, 357–366. doi:10.1901/jeab.2002.77-357

MACE, F. C., & CRiTChFiEld, T. S. (2010). Translational research in behavior analysis: historical traditions and imperative for the future. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 93, 293–312. doi:10.1901/jeab.2010.93-293

MARiNoVA, A., MuRPhy, J., & MASSEy, B. l. (2002). Permission e- mail marketing as a means of targeted promotion. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43, 61–69. Retreived from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8804(02)80009-x

MARTiN, B., VAN duRME, J., RAulAS, M., & MERiSAVo, M. (2003). E- mail advertising: Exploratory insights from Finland. Journal of Advertising Research, 43, 293–300. doi:10.1017/S0021849903030265

MAZuR, J. E. (2010). Editorial: Translational research in JEAB. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 93, 291–292. doi:10.1901/jeab.2010.93-291

MCCoNVillE, M. l., hANTulA, d. A., & AxElRod, S. (1998). Matching training procedures to outcomes: A behavioral and quantitative analysis. Behavior Modification, 22, 391–414.

MERiSAVo, M., & RAulAS, M. (2004). The impact of e- mail marketing on brand loyalty. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 13, 498–505. doi:10.1108/10610420410568435

NEViN, J. A. (2008). Control, prediction, order, and the joys of research. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 89, 119–123. doi:10.1901/jeab.2008.89-119

oliVEiRA- CASTRo, J. M., FoxAll, G. R., & SChREZENMAiER, T. C. (2006). Consumer brand choice: individual and group analyses of demand elasticity. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 85, 147–166. doi:10.1901/jeab.2006.51-04

PiERCE, W. d., & EPliNG, W. F. (1999). Behavior analysis and learning (4th ed.). upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice- hall.

RAJAlA, A. K., & hANTulA, d. A. (2000). Towards a behavioral ecology of consumption: delay- reduction effects on foraging in a simulated internet mall. Managerial and Decision Economics, 21, 145–158.

SChWARTZ, B., & lACEy, h. (1988). What applied studies of human operant conditioning tells us about humans and about operant conditioning. in G. davey & C. Cullen (Eds.), Human operant conditioning and behavior modification (pp. 27-42). Chicester, uK: John Wiley and Sons.

SiGuRdSSoN, V., SAEVARSSoN, h., & FoxAll, G. (2009). Brand- placement and consumer choice: An in- store experiment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 741–744. doi:10.1901/jaba.2009.42-741

307A TesT of The BehAviorAl PersPecTive Model

SilVERPoP. (2012). 2012 Silverpop email marketing metrics benchmark study (White paper). Retrieved from http://www.silverpop.com/marketing- resources/white- papers/download/benchmark- study.html

SMiTh, C., & hANTulA, d. A. (2003). Pricing effects on foraging in a simulated internet shopping mall. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 653–674. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(03)00007-2

SMiTh, V. l. (1989). Theory, experiment and economics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3, 151–169. Retreived from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942969

TEZiNdE, T., SMiTh, B., & MuRPhy, J. (2002). Getting permission: Exploring factors affecting permission marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 16. 28–36. doi:10.1002/dir.10041

ThAlER, R. (2000). From homo economicus to homo sapiens. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14, 133–141. Retreived from http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/richard .thaler/research/pdf/homo.pdf

WoodS, d. W., MilTENBERGER, R. G., & CARR, J. E. (2006). introduction to the special section on clinical behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 407–411. doi:10.1901/jaba.2006.intro

yAN, J., FoxAll, G. R., & doylE, J. R. (2012a). Patterns of reinforcement and the essential values of brands: i. incorporation of utilitarian and informational reinforcement into the estimation of demand. The Psychological Record, 62, 367–376. Retreived from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-298058813.html

yAN, J., FoxAll, G. R., & doylE, J. R. (2012b). Patterns of reinforcement and the essential value of brands: ii. Evaluation of a model of consumer choice. The Psychological Record, 62, 377–394. Retreived from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1 -298058814.html

ZViRAN, M., TE’ENi, d., & GRoSS, y. (2006). does color in e- mail make a difference? Communications of the ACM, 49, 94–99. doi:10.1145/1121949.1121954