A New Piece of the Early Rāṣṭrakūṭa Puzzle from Jamkhed

Transcript of A New Piece of the Early Rāṣṭrakūṭa Puzzle from Jamkhed

1

A New Piece of the Early Rāṣṭrakūṭa Puzzle from Jamkhed

This is an Author’s Original Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis

in South Asian Studies on 14 October 2014, available online:

http://wwww.tandfonline.com/10.1080/02666030.2014.962300

Please contact me (danbalogh at gmail dot com) to request full online access to the

final published version.

Abstract

A pair of copper plates found in Jamkhed and written in cursive box-headed characters

witness a donation of land by an anonymous prince or king who says he is the son of Devarāja

and grandson of the Rāṣṭrakūṭa king Bhavanmāna. This paper identifies Bhavanmāna as the

king known as Mānāṅka in two previously published inscriptions: the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī plates of

Avidheya and the Uṇḍikavāṭikā plates of Abhimanyu. Altogether four generations of this royal

house, sometimes referred to as the Rāṣṭrakūṭas of Mānapura, are known to have ruled

successively. The new discovery furnishes no date or previously unknown dynastic

information, but confirms that these rulers did indeed call themselves Rāṣṭrakūṭa, and hints that

their domain may have extended to the area around Jamkhed.

Keywords

Rāṣṭrakūṭa, Bhavanmāna, Mānāṅka, Devarāja, copperplate land grant, Mānapura,

Jamkhed

Introduction

A pair of copper plates written in a cursive box-headed text were brought to the

attention of Hans Bakker as a potentially interesting historical document, and eventually ended

up with the author of the present paper for study. A description and digital photographs of the

plates have been supplied by Mr. Prashant Kulkarni from Washim (Maharashtra), and the

actual object is now in the possession of Mr. Prakashchand Golechha of Karanja, who

originally found them with a coppersmith in Jamkhed, a town about 130 kilometres to the

south of Aurangabad in Maharashtra). The document turned out on scrutiny to be a land grant

belonging to an early Rāṣṭrakūṭa lineage (sometimes referred to as the Rāṣṭrakūṭas of

Mānapura), few other inscriptions of which have yet been published.

2

Description

The two plates, each inscribed on one face, were originally bound together by a ring

and seal. Their owner cut the ring to have photos of the plates made, and then in a stroke of

misfortune lost the seal in a street while taking the items to the photographer. He reports that

the seal had no recognisable picture, only an inscription of five or six akṣaras. The outside

faces of the plates are completely blank. The sheets are oblong, measuring 59 by 105

millimetres and weighing 81 grams each.

The entire circumference of both plates has a slightly raised rim. There is a single hole

for the binding ring, located near the middle of the longer side, at the bottom of the first page

(verso) and the top of the second (recto). The text was evidently engraved after the holes were

in place, as indicated by the smaller size of the characters above the hole in the last line of the

first plate and the slightly subscript position of characters below the hole in the first line of the

second plate.

The first sheet is in excellent condition except for a flaked-off or heavily corroded

patch in the lower right-hand corner, which has all but obliterated two to three characters. The

second sheet is more badly worn. The lines seem less deeply incised here, and are partially lost

in the weathered texture of the metal, especially in the last line.

The first plate (verso) is engraved with four lines of text, the second (recto) with five.

The characters belong not to the angular par excellence box-headed script found in many

Vākāṭaka documents, but a more cursive and rounded script of a Deccani, rather than central

type1 resembling the Kadamba grants of the 5th to 6th centuries. The engraving is executed in

bold but often very careless lines. The glyphs do have conspicuous box heads, which seem to

have been punched with a blunter instrument than the stylus used for the lines (or possibly first

drawn as outlines and then gouged in the centre), and are surrounded by a slight depression as

a result of this treatment.

The verticals of a, ka, ra and (subscript) ña are curved back and up at the foot; the

curve of ka is occasionally joined back to the primary vertical, and so is that of rā, but not ra or

ru. The two instances of ṇa are both damaged, but the first (puttreṇa in line 4) seems to have a

looped bottom part, while the second (brāhmaṇa in l. 5) appears to consist of just a divided top

part, resembling the form typical in Gupta and Valabhī inscriptions. The character ta, never

looped, is normally rendered with a curving left stroke added to the vertical, but in subscript

form (saṃyukto in l. 8) preserves the older arch shape. Na is drawn in a variety of shapes,

mostly looped but once (the first na of °ānandana in l. 3) with a simple, bent horizontal stroke

resembling both ta and bha. Ya is generally tripartite, but occasionally (yathā in l. 6 and yo in l.

7, both slightly damaged) has a loop on the left-hand side. The letter la has an extended tail

curving back over the letter and down on its left side, except in lo (lopayiṣyati in l. 7), where

the tail loops back to the right to form the vowel mātrā, as in Gaṅga and Cālukya inscriptions.

3

Beside the standard form of sa, there is one instance (sagotro in l. 7) with a looped left limb,

very similar to the looped ya.

The only punctuation mark is an unusual sign featuring three vertical bars, the first

two joined into an arch at the top. This seems to mark the end of sentences or larger units2 and

I have therefore rendered it with a double daṇḍa in the transcribed text below. One instance

appears in line 1 and vaguely resembles the character gā; a possible second instance in line 9

seems to have two additional horizontal dashes: one at the bottom of the second bar (possibly

extended to the bottom of the third bar), and one to the right of the middle of the third bar

(possibly extending in a cross-stroke through all three bars).

The language of the inscription is Sanskrit throughout. The grammar is mostly correct,

except for the notable non-standard form devarājño (for devarājasya) in line 4, and the

omission of two visargas (l. 1 and 9) and one anusvāra (l. 1), each of which may actually have

been engraved shallowly and lost to wear over time. As is standard in inscriptional

orthography, consonants following r are doubled (the only instance of this is nivarttana in line

6). There may be a doubled t preceding r in the damaged word I tentatively read as puttreṇa in

(l. 4), but this is largely a guess, and all three instances of the word gotra are spelled with a

single t. Anusvāra is used before a semivowel in saṃyukto (l. 8), but a ligature with a

homorganic nasal is apparently preferred before stops, as in alaṅkṛtasya (l. 3-4) and °śatan

dattam (l. 6). Halanta m is used once (l. 2), in shape similar to a simplified ma character

without a box head, reduced in size and placed in a slightly subscript position.

Contents

Unusually terse for a land charter, the text begins with an invocation to Puruṣottama,

after which a very brief genealogy of the donor is given in prose. The recipient is then named

and identified as a brāhmaṇa of the Kauśika gotra, but no further personal information (such as

his pravara, the name of his father or his place of origin or residence) is specified. Though

commonly described at this point in land grants, the circumstances of the donation are not

mentioned. The plot is stated to be a hundred nivartanas in area, but no boundaries are

specified, nor is there a list of benefits to be enjoyed by its recipient. The grant stipulates no

purpose to which the donee should dedicate the income from the land. The text closes with a

hasty admonition to posterity to respect the beneficiary’s ownership, but includes not a single

one of the stock verses usually quoted at this point to emphasise the sanctity of land grants.

Seemingly as an afterthought, the name of the village near which the plot is located is specified

at the very end. The sign before the illegible name may indeed have marked the original end of

the inscription.

The donor’s genealogy begins with Bhavanmāna, described as a mahārāja of the

Rāṣṭrakūṭas. The word rāṣṭrakūṭa is clearly used as a family name here, not merely a common

noun denoting the rank of a governor. Albeit the text does not explicitly say so, it is safe to

4

assume that Devarāja, the next name featured in the inscription, was Bhavanmāna’s son. The

donor himself is unfortunately not named in the grant, but the compound jyeṣṭhaputtreṇa in

line 4 clearly implies that Devarāja had three or more sons, among whom he was eldest.

Related inscriptions

Although the name Bhavanmāna is not found in other known records, a certain

Mānāṅka is mentioned in the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant of Abhimanyu (first reported by Indraji,3

analysed by Fleet,4 and re-edited by Hultzsch5) and the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī grant of Avidheya

(first edited by Krishna,6 re-edited by Mirashi7). The former calls Mānāṅka an eminent

Rāṣṭrakūṭa (rāṣṭrakūṭānāṃ tilakabhūto Mānāṅka iti rājā,8 l. 2-3). Both say that Mānāṅka had a

son called Devarāja, just as our Bhavanmāna had a son of the same name. The Uṇḍikavāṭikā

grant further states that Devarāja had three sons, one of whom, called Bhaviṣya (of unspecified

seniority) was the father of Abhimanyu, the issuer of the charter. The Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī grant

was issued by another of Devarāja’s sons called Avidheya (again of unspecified seniority),

who remains regrettably silent not only about the names of his brothers, but also about their

very existence. He does, however, inform us clearly that his father was dead (lokāntarastho, l.

4) at the time the grant was composed.

Both inscriptions probably date from the fifth or sixth century. Indraji (p. 89) noted

that the palaeography of the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant of Abhimanyu suggests a 5th-century origin,

while Fleet (p. 233) was inclined to put it in the late seventh century. Hultzsch (p. 164) offered

no opinion of his own, but seems to have agreed with Fleet. Krishna (p. 200) put the

Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī grant of Avidheya in the fifth or sixth century on a palaeographic basis and

then (p. 203) proposed 516 CE as its probable date, based mostly on circumstantial evidence

and speculation. Mirashi (p. 15–17) gives no date for the grant, but hypothesizes (somewhat

tenuously) that Mānāṅka, the founder of the dynasty, ruled in the last quarter of the fourth

century, and Devarāja in the first quarter of the fifth.

A third set of copper plates, the Hiṃgṇī Berḍī plates of Vibhurāja,9 probably also

belong to the same dynasty. These were issued in the third year of the reign of a certain

Vibhurāja, described as an ornament of the goddess that is the Rāṣṭrakūṭa dynasty

(rāṣṭrakūṭeśvarāṇām anvavāyaśriyo ’laṃkāreṇa,10 l. 1-2). On palaeographic grounds Dikshit (p.

174) places the inscription in the 5th or 6th century, but his editor revises this to 6th or 7th in his

corrigenda. The text of the grant is rather vague, with numerous misspellings and dubious

readings. As deciphered by Dikshit, it seems to say that a lady called Śyāvalaṅgī Mahādevī,

who may have been identical to the lady Prabhāvatyāryā, wife of Devarāja and mother of

Māṇarāja, donated land and gold ingots11 to a brāhmaṇa. No other members of the dynasty are

named, but the Devarāja mentioned here is in all likelihood identical to our Devarāja. Dikshit

(p. 176) suggests that Māṇarāja and Vibhurāja are two names for one person, the hitherto

unknown son of Devarāja. His editor disagrees, and in his corrigenda remarks that “there is no

5

reason to identify” Vibhurāja and Māṇarāja, then proposes that Prabhāvatyāryā may have been

Śyāvalaṅgī’s mother-in-law, the former donating gold to supplement the latter’s land donation.

This latter scenario, though plausible, does not make the cast of characters any clearer, while

giving rise to new questions: who was Māṇarāja in this case, and who was Śyāvalaṅgī married

to? Given the vagueness of the text as presently deciphered, I do not believe it is possible to

decide either way (however, re-editing the text from the original plates would be definitely

worth the while if they are still available somewhere).

A fourth grant, the Gokāk plates of Dejja,12 may also contain a reference to this

dynasty. Mirashi noted this possibility in his paper on the early Rāṣṭrakūṭa dynasty,13 while

Dikshit (p. 175) took it for granted. These plates were issued by a certain Indraṇanda of the

Sendraka dynasty, whose liege lord was Dejja mahārāja of the Rāṣṭrakūṭa dynasty

(rāṣṭrakūṭānvaya-jāta-śrī-dejja-mahārāja°, l. 5–6). Rao tentatively proposed 532/533 CE as the

date of the inscription, which Mirashi14 accepted, hypothesising that Dejja was a descendant of

Bhaviṣya. While this is definitely a possibility, the Gokāk plates regrettably yield no

information about any other members of this early Rāṣṭrakūṭa house, and therefore float in a

sort of contextual vacuum. An alternative possibility, which for the present must remain a

hypothesis for want of evidence, is that Dejja may have been the vernacular name of Devarāja,

that is to say, Bhaviṣya’s father rather than one of his descendants (although Dejja is clearly

called a mahārāja, while Devarāja, when given a title at all, is a rājan in other known

inscriptions). Mirashi may have ignored this possibility because he wanted to see the

Rāṣṭrakūṭas of Acalapura as late descendants of Mānāṅka’s dynasty15 and thus needed a far

earlier date for Devarāja than the second quarter of the sixth century.

Konow16 had been the first scholar to propose that Mānamātra and his son Sudevarāja

of Śarabhapura might be identical to Mānāṅka and his son Devarāja, at that time known only

from the Uṇḍikavāṭikā plates of Abhimanyu. Krishna17 carried the assumption further,

proposing that Jayarāja of Śarabhapura may have been the third son of Devarāja, and

proceeded to weave an elaborate, if tenuous, theory about an overarching Rāṣṭrakūṭa empire in

the late fifth and early sixth century. Altekar18 argued methodically (though at some points,

over-enthusiastically) against his conjectures, which were also mostly rejected by Mirashi.19

Over the century since then, a good number of other Śarabhapura inscriptions have come to

light,20 ruling out for good the identification which Konow himself had qualified as “very

doubtful.”

Mirashi21 also put forth the idea that the Siroda plates of Devarāja22 may have been

issued by our Devarāja. These plates were assigned to the 4th century by Krishnamacharlu,

which more or less fits Mirashi’s grand theory. He further points out that the ruler is compared

in this inscription to the divine Devarāja, just like his Rāṣṭrakūṭa namesake in the Uṇḍikavāṭikā

and the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī charters, which in his opinion “proves the identity of this Devarāja.”

Nonetheless, the terminology of the comparison is dissimilar in all three grants,23 and in any

6

case what would be really remarkable is if any king named Devarāja were not compared to

Indra in a praśasti. Mirashi24 attempts to explain the Siroda donor’s apparently unique dynastic

name Gomin by positing that it could have been an early name of this Rāṣṭrakūṭa dynasty, or

alternatively that the words candrapurād gomināṃ devarāja-vacanāt might mean “by order of

Devarāja from Candrapura of the Gomins” rather than “by order of Devarāja of the Gomins,

from Candrapura.” It appears, however, that Mirashi was unaware of (or conveniently

neglected?) Rao’s convincing argument25 that the correct reading should in fact be candraūrād

bhojānāṃ devarāja-vacanāt, which makes Devarāja of the Siroda grant a member of the Bhoja

dynasty known from other inscriptions to have ruled in Candraūra (modern Chandor, a few

kilometres south of Siroda).

7

Table 1: Overview of potentially cognate plates

grant size (cm) rim placement of hole seal dynastic information

Jamkhed

(anonymous)

5.9×10.5 slightly

raised

centre of top (recto) and

bottom (verso)

5-6 akṣaras of text, no

image (?)

Rāṣṭrakūṭa Bhavanmāna – son

Devarāja – three sons

Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī

(Avidheya)

6.4×19.1 flat centre of left side

(recto & verso)

lion rampant facing

proper right

Mānāṅka – son Devarāja – son

Avidheya

Uṇḍikavāṭikā

(Abhimanyu)

6.4×13.7 flat centre of top (recto) and

bottom (verso)

lion couchant facing

proper right

Rāṣṭrakūṭa Mānāṅka – son Devarāja

– three sons including Bhaviṣya –

son Abhimanyu

Hiṃgṇī Berḍī

(Vibhurāja)

6.4×12.7 raised centre of top (recto) and

bottom (verso)

akṣamālā, kamaṇḍalu

and daṇḍa or kuśa blade

Rāṣṭrakūṭa Devarāja – son(?)

Vibhurāja/Māṇarāja

8

Implications

Given the extreme terseness of the Jamkhed charter, there is little historical

information to be gleaned from it. It definitely serves as corroboration, though still not absolute

proof, that the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī and the Uṇḍikavāṭikā plates are cognate and belong to a

dynasty that called itself Rāṣṭrakūṭa (as Krishna26 and Mirashi27 had surmised, pace Altekar28).

The only place name (if a place name at all) in the present document is illegible, but if

the findspot is any clue to the historical location of the donated land, then it implies a fairly

wide domain for this Rāṣṭrakūṭa family. The provenance of the Uṇḍikavāṭikā and

Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī charters is rather hazy. Fleet (p. 511–514) identified several of the places

mentioned in the Uṇḍikavāṭikā charter’s description of the donated land as lying in the

Mahadeva Hills (near Pachmarhi in southern Madhya Pradesh). Krishna29 proposed to identify

Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī with modern Pandharpur, about 50 km west of Solapur in southern

Maharashtra, and proceeded to locate in the same vicinity some more places named in

Avidheya’s grant. Contesting both earlier authors, Mirashi30 traced both these grants to the

vicinity of Karhāḍ (often spelt Karad in English) in the Satara district of southern Maharashtra,

about 130 km west-southwest of Pandharpur. Jamkhed is over 500 kilometres southwest of the

region proposed by Fleet and about 200 kilometres northeast of that put forth by Mirashi (and

just 120 km north of Krishna’s Pandharpur, but given that most of his place name readings

have been convincingly rejected by Mirashi, his specific identifications cannot be relied upon).

The single geographical name in the Hiṃgṇī Berḍī grant has not been identified, but the site

the plates were discovered is about 100 kilometres east of Pune (approximately 150 km north

and somewhat east of Karhāḍ). Gokāk, where the plates referring to Dejja were found, is

located in the northwestern region of modern Karnataka (about 150 kilometres southeast of

Karhāḍ). Of the four place names in this grant, only one has been identified, which is in the

same vicinity.

The location of Mānapura, named only in the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant but presumably the

seat of the dynasty and connected in name to Mānāṅka/Bhavanmāna, remains uncertain. Indraji

(p. 89) proposed to identify it with modern Malkhed in the north of Karnataka, i.e.

Mānyakheta, the capital of the imperial Rāṣṭrakūṭas. Fleet (p. 514) rejected this and, though he

offered several alternatives, finally concluded that Mānapura “cannot be satisfactorily

identified” and may not have been a capital, but “simply an ordinary town or village […]

which Abhimanyu had honoured by camping at it.”31 Mirashi32 in turn put forward the town

called Māṇ (nowadays Anglicised as Maan and apparently identical to or situated near

Dahiwadi) in the Satara district, about 80 kilometres northeast of Karhāḍ.

Fleet’s proposition of a Rāṣṭrakūṭa territory in the Mahadeva Hills must have rested

greatly on the assumption that Mānāṅka’s descendants were identical to the rulers of

Śarabhapura. Beside the loss of this pillar to his argument, all the geographical data outlined

9

above point to a region in southern Maharashtra. Furthermore, the alphabets employed in the

grants of Mānāṅka’s family, though slightly varying, are generally of a southern rather than

central Indian class. The emergence of a land charter from the neighbourhood of Jamkhed

suggests that even if the sway of this dynasty did not extend as far as the Satpura range, they

did control some territory to the north and east of their southern heartland.

No matter how great a domain they ruled, the Rāṣṭrakūṭas of this lineage could not

have been emperors, as evidenced by their sparing use of royal titles. Unlike his father

Bhavanmāna, who was (at least posthumously) styled a mahārāja, Devarāja is described in the

present grant as a humble rājan, yet a cause of joy to his gotra in spite of his ostensibly

diminished stature. This strongly implies that whether or not Bhavanmāna was an independent

ruler in his own time, Devarāja would have been a subordinate prince governing under a more

powerful liege. The wording rājaśabdālaṅkṛtasya may also hint that his title rājan was viewed

as “decoration” conferred on him by an overlord.

The other charters of the dynasty are similarly modest. The Uṇḍikavāṭikā plates (l. 2)

refer to Mānāṅka as a rājan and the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī plates (l. 1) as nṛpati (the choice of this

synonym may have been dictated by the anuṣṭubh metre used at this point in the genealogy).

Devarāja bears no title in either of these grants, nor does he have one in the Hiṃgṇī Berḍī as

read by Dikshit. However, I propose that the words śrīmato rāṣṭṛadevarājasya in lines 9-10

(which Dikshit emends to śrīmato rāṣṭra[kūṭa]devarājasya) should instead be read as śrīmato

rājño devarājasya. In this case two of the four extant documents mentioning Devarāja agree

that his title was rājan, though if Dejja was indeed the same person, as I conjectured above,

then the number of documents increases to five, with one (issued by a subordinate prince who

may well have wanted to flatter his liege) calling him mahārāja.

The fortunes of the dynasty may have risen subsequently. Avidheya is also called just

a rājan in the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī plates (l. 9), but the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant describes the three sons

of Devarāja as sakala-rājaka-bhūmināthāḥ (l. 8-9), which at least suggests that they were not

the pettiest kind of ruler, while the Hiṃgṇī Berḍī inscription refers to Vibhurāja as a mahārāja

(l. 2). In contrast, the donor of the present grant, identified as the eldest son of Devarāja,

altogether lacks a royal title. Taken together with the fact that he is not named and is not

afforded a scrap of eulogy, this suggests that he was underage at the time of the donation,

possibly even a very young child.

Text

Transliteration

Dubious readings are enclosed in round brackets; square brackets mark badly

damaged (and hence particularly uncertain) characters. Spaces in the inscription are indicated

10

by underscores, all other spaces in the transliterated text are my additions. Asterisks denote

illegible akṣaras.

Plate 1

1. nama puruṣottamāya (||) rāṣṭrakuṭānā

2. mahārājaśrībhavanmānasya _ ru(la)

3. gotrānanda(n)a(k)arasya _ rājaśa(bdā)

4. la(ṅkṛ)tasya (de)vara(jñe) jyeṣṭha[puttreṇa]

Plate 2

5. brāhma(ṇakau)śi(ka)sagotra(kṛṣṇa)svā

6. m(i)ne _ nivarttanaśatan dattam (yathā)

7. (yo lopa)yiṣyati sagotro (anyo)vā

8. sa pa(ñ)camahāpātakasaṃyukto bhavi

9. (ṣya)ti _ [(||) **grāme bhūmi]

Emended version

The following is my reconstruction of the text as it may have been intended by its

composer, emending what I take to be engraver’s mistakes, but retaining the orthography and

the grammatical peculiarity of the original. I have added a single daṇḍa at the end of the

sentence where the inscription features a halanta m, and used hyphens to indicate compound

boundaries not obscured by vowel saṃdhi.

namaḥ puruṣottamāya|| rāṣṭrakūṭānāṃ mahārāja-śrī-bhavanmānasya kule

gotrānandana-karasya rāja-śabdālaṅkṛtasya devarājño jyeṣṭha-puttreṇa brāhmaṇa-kauśika-

sagotra-kṛṣṇa-svāmine nivarttana-śatan dattam| yathā yo lopayiṣyati sagotro anyo vā sa

pañca-mahā-pātaka-saṃyukto bhaviṣyati|| **grāme bhūmiḥ||

Problematic readings

As noted above, many of the characters in the inscription are executed in a boldly

careless style, and the surface of the plates is damaged enough in some places to make glyph

identification problematic. A hands-on study of the original plates would probably resolve at

least some of the issues. Till then, the following discussion might serve as partial justification

for my proposed readings.

One of the crucial issues in deciphering the inscription is the uncertainty of the fifth

through eighth characters of line 4. The first three of these are almost certainly devara, but the

final character, though boldly drawn and free of damage, is perplexing. I propose reading this

as jñe (with the superscript j part drawn in a somewhat idiosyncratic manner, like many of the

less equivocal characters in the inscription) and emending the text to devarājño. The

declension of rājan at the end of a compound in a way identical to a non-compounded -an stem

is not unheard of in inscriptional language.33 Note also that the expression rājño devarājasya

11

may have been a standard expression in the grants of this dynasty (see my proposed reading of

the Hiṃgṇī Berḍī grant above), and the compound devarājño may be a hasty contraction of

this, to save space on the very small Jamkhed plates.

At the end of line 4, only the top part of the letter ṇa is preserved intact at the very

end, but the trace of the rest its loop and tail are visible enough to leave little doubt as to the

identification of this character. My reconstruction of the previous two akṣaras admittedly relies

on conjecture. Due to heavy damage to the surface of the plate here, only two box heads can be

made out with any degree of certainty. Of the first letter, I believe it is possible to discern the

left and bottom part of pa, while of the second, an e mātrā at the top and a curling subscript r at

the bottom are reasonably recognisable; the section in between seems to consist of a vertical

line with at least one, more likely two horizontal strokes to the left – hence my conjectural

reading puttreṇa.

Translation

Homage to the Supreme Person. In the family of the great king Śrī Bhavanmāna of the

Rāṣṭrakūṭas [was born] Devarāja, decorated with the word “King” and a bringer of delight to

his lineage. [His] eldest son has given Kṛṣṇasvāmin, a brāhmaṇa belonging to the gotra of

Kauśika, a hundred nivartanas [of land]. Thus anybody, whether of the same lineage or other,

who would deprive [him of that] shall be sullied with the five great sins. The land is in the

village of **.

12

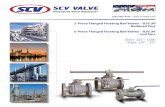

Figure 1: photograph of the plates

Digital photographs by courtesy of Prashant Kulkarni, image enhancement by the author.

13

Figure 2: Transcript

Black colour shows lines unequivocally visible on the original photographs of the plates; grey

colour indicates uncertain lines.

Notes

1 As classified by Georg Bühler, ‘Indian Paleography,’ IA 33 (1904), Appendix (pp. 64–67). 2 My thanks to Hans Bakker for pointing out that a vaguely similar sign is used with a similar function in the

Muṇḍeśvarī inscription. For a brief discussion see Hans Bakker, ‘The Temple of Maṇḍaleśvarasvāmin – The

Muṇḍeśvarī Inscription of the Time of Udayasena Reconsidered,’ Indo-Iranian Journal 56 (2013), 263–277 (p.

267). 3 Paṇḍit Bhagwānlāl Indraji, ‘New Copper-plate Grants of the Râshṭrakūṭa Dynasty,’ JBRAS 16 (1885), 88–92. 4 John Faithfull Fleet, ‘Notes on Indian History and Geography / The places mentioned in the Uṇṭikavâṭikâ

grant,’ The Indian Antiquary 30 (1901), 509–14. 5 Eugen Hultzsch, ‘Undikavatika Grant of Abhimanyu,’ EI 8 (1906), 163–66. 6 Mysore Hatti Krishna, ‘Panduranga-palli Grant of Avidheya,’ Annual Report of the Mysore Archæological

Department for the Year 1929 (1931), 197–210. 7 Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, ‘Pandarangapalli Grant of Rashtrakuta Avidheya,’ EI 37 (1968), 9–24.

14

8 Text quoted from the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant throughout this paper follows the reading and emendations of

Hultzsch. 9 Moreshwar G. Dikshit, ‘Hingni Berdi Plates of Rashtrakuta Vibhuraja; year 3,’ EI 29 (1952), 174–177. 10 Following Dikshit’s reading; the avagraha is my addition. 11 Dikshit’s reading (l. 13-15) is kamalībhūhakāgrāhārasya dakṣiṇā suvarṇṇaśilakāyāḥ (Dikshit em. °śalākāyāḥ)

pañcāśat tāmraśāsananabaddhā (Dikshit em. °nibaddhā). As far as I can make it out on the plates in

Epigraphia Indica, the actual inscription says dakṣiṇe, hence I believe suvarṇṇaśilakāyāḥ should be understood

as a place name (and probably emended to °śilakāyāṃ). My interpretation still requires a supplied

nivarttaṇānāṃ or a similar noun to complete the sentence, but this feels less awkward than Dikshit’s version. 12 N. Lakshminarayan Rao, ‘Gokak Plates of Dejja-Maharaja,’ EI 21 (1932), 289–292. 13 Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas of Mānapura,’ ABORI Vol. 25, No. 1/3 (1944), 36–50. Mirashi (p.

46 note) credits Altekar for this suggestion, but gives no reference to any publication of the latter, so this

appears to have been oral communication. 14 ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas…’ p. 46. 15 ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas…’ p. 47–50. 16 Sten Konow, ‘Khariar Copper Plates of Maha-Sudeva,’ EI 9 (1908), 170–173. 17 ‘Panduranga-palli Grant…’ p. 202–205; also Mysore Hatti Krishna, ‘The Early Rashtrakutas of the

Maharashtra,’ Professor K. V. Rangaswami Aiyangar Commemoration Volume (1940), 55–63. 18 Anant Sadashiv Altekar, ‘Was there a Rāṣṭrakūṭa Empire in the 6th Century A.D.?’ ABORI vol. 24 pt. 3–4

(1943), 149–155. 19 ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas…’ p. 38–39. 20 Ajay Mitra Shastri, Inscriptions of the Śarabhapurīyas, Pāṇḍuvaṁśins and Somavaṁśins, Motilal Banarsidass

1995. See Part I, pp. 95–109 for the genealogy and p. 114 for a summary dismissal of the identification of the

dynasty with that of Mānāṅka. 21 ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas…’ p. 42–43. 22 C. R. Krishnamacharlu: ‘Siroda plates of Devaraja,’ EI 24, (1938), 143–145. Mirashi consistently spells the

place name as Sisodrā, which seems erroneous. The findspot must have been the village today known as

Shiroda or Shirodem, a couple of kilometres south of Ponda (Goa). 23 Siroda l. 16: devarāja-pratimasya devarājasyājñayā; Uṇḍikavāṭikā l. 3-4: tasya vigrahavān iva devarājā

devarājeti sūnuḥ; Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī l. 4–6: devarājaḥ sutas tasya devarāja ivāśritān| cakārāsamasampattīn niratyayasukhodayān||

24 ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas…’ p. 43. 25 N. Lakshminarayan Rao, ‘A note on Siroda plates of (Bhoja) Devaraja,’ EI 26 (1942) 337–340. 26 “There can be little doubt now that Avidhêya was a brother of Bhavishya and […] the grand-son of […] the

founder of the first known independent Râshṭrakūṭa kingdom,” ‘Panduranga-palli Grant…’ p. 207. 27 “I did not, however, share Altekar’s suspicions about the identification of Mānāṅka and Devarāja with the

homonymous princes described in the Pāṇḍaraṅgapallī grant,” ‘Pandarangapalli Grant…’ p. 14. 28 “It is likely that […] Avidheya […] and Abhimanyu […] were the descendants of Mānāṅka […], though there

is no conclusive proof for this assumption. […] is it not strange that only in one of them […] they should have

been described as Rāsṭrakūtas?[sic],” p. 153. 29 ‘Panduranga-palli Grant…’ p. 206. 30 ‘Pandarangapalli Grant…’ p. 14. 31 This idea may have been sparked by the wording of the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant: tena Mānapuram

adhyasanenālaṃkurvatā (l. 12–13). 32 ‘Pandarangapalli Grant…’ p. 12, 14; ‘The Rāṣṭrakūṭas…’ p. 42. 33 See e.g. devarājā (for devarājo) in line 3 of the Uṇḍikavāṭikā grant for an example in a closely related record,

or the seal imprint śrīhastirājñaḥ at the end of the Jabalpur Plates of Mahārāja Hastin (Raj Bali Pandey,

‘Jabalpur Plates of Maharaja Hastin,’ EI 28 (1950), p. 264–267) for a more widely known example (thanks to

Csaba Dezső for bringing this to my attention).