A methodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation infrastructure: Application to...

Transcript of A methodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation infrastructure: Application to...

Case Studies on Transport Policy xxx (2015) xxx–xxx

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

A methodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportationinfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura

José Antonio Gutiérrez Gallegoa, José Manuel Naranjo Gómeza,*,Francisco Javier Jaraíz-Cabanillasb, Enrique Eugenio Ruiz Labradora, Jin Su Jeongc

aDepartment of Graphical Expression, University of Extremadura, Universidad Avenue, s/n, 10071 Cáceres, SpainbDepartment of Territorial Sciences, University of Extremadura, Universidad Avenue s/n, 10071 Cáceres, SpaincDepartment of Graphical Expression, University of Extremadura, Calle Santa Teresa de Jornet, 38, 06800 Mérida, Spain

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:Received 8 January 2014Received in revised form 26 May 2015Accepted 30 June 2015Available online xxx

Keywords:High-speed railAccessibilityGeographical information systemsRegional dissymmetryTunnel effect

A B S T R A C T

High-speed rail (HSR) affects enormously on the territory and provokes intense socio-economicdynamics because it articulates the territory according to the distribution of the accessibility in thesettlements. Thus, the easier it would be the access of the residents from a city to another, the better itwould be its opportunities of socio-economic development.These effects motivated by the different degree of accessibility produced in the territory are more acute

in the less developed regions. In this regard, this work proposes a methodology applicable not only to anyplace in general, but in this particular case also to Extremadura because this region is the least developedin Spain.This methodology in which importance resides that it is applicable before the physical implantation of

the HSR in the territory allows to achieve the following objectives: delivers a judgment if the distributionof the population which will accede to the HSR is balanced, shows the future hierarchical organization ofthe territory in more or less favoured zones and determines the degree of connection of the region on anational scale with Spain and an international scale with Portugal.This paper is based on the use of tools for network design and the geographic information systems (GIS)

and proposes a new indicator of absolute accessibility parameters application, together with theexploitation of information use of the descriptive statistics.The obtained results show how the isolated areas, without adequate access to high-speed service, are

going to continue to exist although it diminishes the lack of equity in the different zones of Extremadura,which is the object of study.

ã 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of World Conference on Transport Research Society.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Case Studies on Transport Policy

journa l homepage: www.e lsev ier .com/ locate /cstp

1. Introduction

The transport infrastructures according to the classic geographyreceive a prominent role in the socio-economic development of aterritory (Potrykowski and Taylor, 1984; Dematteis, 1995). Thus,the transport and communications network act as a linchpin of aset of spatial connections having the population as its actor and theterritory as the reference scenario (Reques et al., 2012). Accord-ingly, the structures and forms of transport systems grow inparallel to the society (Escolano, 2012) because they allow to

* Corresponding author. Present address: Department of Graphical Expression,University of Extremadura, Universidad Avenue, s/n, 10071 Cáceres, Spain.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego), [email protected](J.M. Naranjo Gómez), [email protected] (F.J. Jaraíz-Cabanillas), [email protected](E.E. Ruiz Labrador), [email protected] (J.S. Jeong).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.0032213-624X/ã 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of World Conference on Transp

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

supporting the relations between the inhabitants from differentparts in the socio-economic system (Bauman, 2000). Therefore,without being a sufficient condition for economic growth andwealth creation, the implementation of the high-speed rail (HSR)can stimulate the fundamental aspects of social and economicstructures (Plassard, 1997). Nevertheless, the structural effects tothis transport infrastructure such as the physical transformationcaused by the infrastructure construction, the changes in themobility patterns and land use, the impact in the dynamics andstructures, social and economic, and the physical transformationcaused by new and increased mobility patterns, which cannot beisolated. As a result, these depend on three factors as the following:the territorial context where it is implemented; the characteristicsand dynamics of the territory; and, the measures carried out by thesocial agents who act in the local environment (Bellet et al., 2010).

Then, the implementation of the HSR in the existing transportnetwork modifies unevenly the degree of connectivity to the nuclei

ort Research Society.

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

Fig. 1. Successive phases of the network-space effect.

2 J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

affected, since this variable depends on the characteristics of thenetwork itself and the location of settlements. So, the settlementsthat have major connectivity present also a major accessibility tothe offered services and more opportunities of socio-economicdevelopment. Therefore, it is possible to affirm that the connec-tivity somehow determines the evolution of the territory(Menéndez et al., 2002).

Considering the previous premises, in this paper, a methodolo-gy is described to measure the influence of the HRS in theaccessibility of the region where the infrastructure is imple-mented.For this, the degree of territorial peninsular connectivity isevaluated once well-established the infrastructure, by means of aseries of accessibility indicators and making the use of proper toolssuch as the geographical information systems (GIS). The combina-tion of both tools can generate a model with which to analyse thelevel of interconnection. The effects provoked by the HSR have tobe perceived in the alteration of the network-space in this territoryand in the modification of the accessibility level to the centres ofeconomic activity.

These effects of the HSR specifically cause a new spatial andurban hierarchical organization (De Ureña, 2012a,b). Thus, theyhave a big territorial coverage and must be studied on a regional, anational and even an international scale (Varlet, 2000; Vickerman,1997; Gutiérrez, 2001; Zembri, 2005; Ureña et al., 2006). This studyanalyses the impact that supposes the extension of the high-speedrailway infrastructure in the Iberian Peninsula, about theinhabitants of Extremadura. The cartography uses the networkmodel of roads and railroads in the peninsular and all the urbancentres in Extremadura, together with the location of the futurestations of the HSR in the peninsular of Spain. In the same way,initially a model of analysis applies to regional scale inExtremadura and later expands to a national scale, to the stationsof the bordering provinces and to the peninsular centres ofeconomic activity. Of this form, it is determined in a more realisticway, the impact of the above-mentioned infrastructure.

With regard to the centres of the economic activity, the IberianPeninsula is taken into account. For the Spanish case, it isconsidered to be the urban areas whose resident populationexceeds 200,000 inhabitants, whereas for the Portuguese case, ithas the urban agglomerations exceeding 100,000 inhabitants. ThePortuguese limit is lower because its morphology is slightlydifferent and with the previous threshold settlements would beobviated by an important area of influence and a capacity ofimportant market (Gutiérrez et al., 2010).

The aims of the study are to determine if the populationdistribution that can potentially access to the HSR in Extremadurais homogeneous or not, to establish which are the areas that will bemore or less favoured by the arrival of the HSR infrastructure.Thus,it determines how the Spanish rail transport policy influences theimprovement of accessibility. Nonetheless, there does not forecastthe potential demand of HSR, since Spain is the only example ofhigh-speed rail network extended from criteria of equity, cohesionand territorial development. As consequence, in the developmentof HSR, there have been ignored criteria of economic efficiency anda great priority has given to meta-political objectives. For thisreason, territorial governments require the incorporation of theirterritories in the network of HSR, generating a radial networkwhich center is the political capital of the country, Madrid.Consequently, investments has been carried out with negativefinancial and social profitability, since the intensity of use of HSR isvery low in comparison with the rest of international experiences,and the contrast is going to tend to worsen with the entry in serviceof new lines whose demand is declining (Albalate and Bel, 2014).

Later, a brief literature review is described about similar studiesin other regions, to depict the methodology used in this particularstudy. In the Section 3, the obtained results are enumerated and

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

finally in the Section 4, the main conclusions and proposals resultof the research carried out.

1.1. State of the art

The infrastructures are one of the fundamental elements in theregional development, since they modify directly the conditions ofthe territories' accessibility in which it is constructed andindirectly that of the adjacent ones (Condeço-Melhorado et al.,2010; Quan and Si-Ming, 2011). Moreover, they constitute animportant instrument of territorial cohesion and integration,acting as catalysts in the unification of multinational spaces(Vickerman, 1994).

An evident proof of the value that the infrastructures receive inthe territorial cohesion and integration is the marked interest thathas the European Union (EU) in its development. Thus, the WhiteBook of Common Transport Polices already gathers in 1990 that themajor barrier for the development of the isolated regions is theproper transport infrastructure, since isolated to the peripheralregions at the same time as congested to the head offices, by theincrease of the activity concentration as the mentioned above(Vickerman, 2012). In this sense, the principal aim of the EU is toconvert the policy of infrastructures into a policy of territorialintegration, in order that the population of these isolated regionscould access to others with major economic dynamism and to forma part of activities that would be inaccessible without the above-mentioned infrastructures. The consequence of this policy is that,the transport systems in general and the HSR in particular, itgenerates homogeneous economic and social development in theterritory revitalizing the sector of the railroad and turning it into akey piece of this development for its high commercial speed and itscapacity of passengers (CEE, 1999). The proof of its importance isthat the majority of the developed countries possess technologi-cally at the present with a network of high-speed trains (Terribas,2011; Martí-Henneberg, 2013).

All these European recommendations can be found nationwidein Spain in the plan of infrastructure, transport and housing (PITVI)for the period 2012–2024. In this plan, it foresees the developmentof the high-speed railway line in Madrid–Extremadura–Portu-guese border. The stations projected to accede to this service arethe result of the consensus between representatives of theDepartment of Promotion, Government of Extremadura and themunicipalities affected.

This new projected infrastructure is looking for the incorpo-ration of Extremadura to the Spanish high-speed network,improving its connection with Portugal and the peninsular centre.The consequence of all this is that the region would be peripheralto turning into an integrated national and European level.Nevertheless, they must not neglect the intraregional environ-ments and, therefore, have to be avoided the breaks of the socio-economic relations between the peripheral and central areas,

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx 3

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

resulted that might take place with the implementation of the HSR(Fig. 1).

To reduce to the maximum of these polarization effects and toallow the equitable access to the service, they receive the interestof the studies that analyse the phenomena of hinterlands motivatedby the implementation of the HSR (Puga, 2002; Banister andBerechman, 2003; Bröcker et al., 2010). The common goal of theseresearches is to minimize the maximum of the effect mentionedabove and to distribute equitably the benefits of transport betweenthe possible maximum numbers of users of a territory, giving apriority to the connection to the high-speed network indepen-dently of the geographical location thereof.

Another problem that according to the EU must be avoided isthat, before the increasing risks of spatial polarization in theinvestments and the economic growth, has to assure that the highperformance infrastructures such as the high-speed railroads andthe high-capacity highways not absorbing resources of the leastfavoured or peripheral regions (pumping effect) and that crossregions without connecting them (tunnel effect). Therefore, thepolicies of territorial development should ensure because thesehigh-level infrastructures are complemented with secondarynetworks, promoting all the regions experience benefits asequitably as possible (CEE, 1999; Bristow and Nellthorp, 2000).

On the other hand, numerous specialists (Biehl, 1986; Banisterand Berechman, 2003; Fürst et al., 2000; Bröcker et al., 2003;Ozbay et al., 2003; López et al., 2009; Vickerman, 2012) affirm thatthe improvement of the accessibility concerns the growth of theproductive sectors increasing the competitiveness, the growth andemployment. In relation to the improvement of the accessibility inthe peripheral regions, it produces an effect of competitionbetween them, besides an effect of the convergence and cohesion.This fact incites that a great number of cities demand the HSR totake benefits such as the efficiency in the transport and the effectsof transfer and re-location of productive activities (Martínez andAraya, 2000; Geurs and Ritsema, 2001).

Therefore, it is possible to say that the analyses of accessibilityare an interesting tool at the moment of valuing the degree ofconnection between different zones with the construction of aninfrastructure such this type. Nevertheless, there are circum-stances that prevent these analyses of direct form and it isnecessary to determine studying alternative variables thattogether, offering a clear vision of what is the degree ofaccessibility to the service analysed (Geurs and Ritsema, 2001).

In the bibliography on accessibility, it is observed a great varietyof indicators that evaluate them (Fotheringham and Wegener,2000; García, 2000; Monzón et al., 2005; Gutiérrez et al., 1994;Brocard, 2009) and though all of them offer a measure to close theexisting separation between human settlements and activitiesdepending on the transport network made available to defining asingle indicator of accessibility that includes all the approaches is anearly impossible to realize. Since each indicator measures thisvariable from a concrete point of view, to evaluate the quality of theaccess to the transport infrastructures and to determine strategiclocations or as tools for the planning in the decision-makingsprocess (Gutiérrez et al., 1994). However, these indicators cancomplement each other to provide a clearer picture about thebenefits that the analysed infrastructure will facilitate theterritories affected by it.

2. Materials and methods

To analyse the accessibility to the high-speed rail network of theresidents in the Extremadura nuclei the actual conditions aresupported by analysis tools of the networks of their own GISapplications, in a series of indicators of accessibility and incartographic information of vector type that represents the various

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

cores and the network that connects them (network of roads andrailways). Both transportation networks with arc-node topologyare divided into limited sections by nodes or points of intersectionbetween them.

The network of roads and railways together forms a multimodalroad network, being railway stations, the only places where canproduce the intermodality. It is considered that the residents in acenter of population are going to choose the route that should takethem minor time of access to their destination, using the networkof roads or railroads or both partially.With all these data, itdetermines the degree of proximity or regional peripherality,based on the premise that all residents will always have access tothe nearest HSR station. In the case of the stages of the network, itsaves also information on the category and maximum permissiblespeed; in the case of the population nucleus and the centres ofeconomic activity, the resident population data are stored in eachcase. The results obtained are shown in thematic maps with whichidentify spatial patterns not observable at a glance.

In previous studies similar to the one presented in this research,we analyse an infrastructure without contemplating informationwith which weigh the degree of importance to access the servicestations. To resolve this problem is to weight each station with itsdegree of accessibility to a regional and national level asdetermined by a series of variables and measures of topologicaltype linked to the access times.

The first variable used is the minimum access time ofpopulation to the train stations. To do this, we took into accountthe location of the population cores of Extremadura and the HSRstations. The next step is to assigning each population centre of thenearest HSR stop that is on the road network of Extremadura, intravel time. This indicator is measured in two models: closed oneand open one. The first one is based only on a regional analysis ofthe cores with respect to the Extremadura stations, while thesecond one analyses the minimum times of these nuclei inresponse to three different destinations: (1) HSR stops inExtremadura and its adjacent autonomous regions; (2) centresof peninsular economic activity are less than 600 km; and (3)peninsular centres of economic activity without any kind ofrestrictions.

Threshold is chosen as 600 km distance due to the fact that theinitial approach in the construction of high-speed railwaynetworks, especially in the French design, and was to establishconnections between big cities or remote metropolis (Auphan,2002). However, the use of this means of transport for distances forover 600 km whose travel time is between two and three hours tripwas very low (Klein et al., 1997), and its increased use for shorterdistances (Menéndez et al., 2002).

In this way, the HSR has renewed its roll going to be acompetitor of the transport mode by air to complement andbecome an effective way of transport for travel of middle distance(Vickerman, 2012).

The second variable is the improved index of absoluteaccessibility (IAAi), which measures the interconnection degreeof a population nucleus with the rest of the Extremadura cores,depending on the potential population and the minimum accesstime to the main centres of economic activity (Gutiérrez et al.,1994). Thus, this index calculates the weighted average of theminimum access time of each core activity centres over thenetwork, taking into account a weighting factor of the recentdemographic volume according to the following expression:

IAAi ¼

Xn

j¼1ðIRij � PCAEjÞ

Pnj¼1 PCAEj

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

4 J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

where IRij is minimum time between nodes ij, across the network,and PCAEj is the population of major urban areas in the IberianPeninsula.

It is proposed the following formulation to calculate IRij that isthe minimum travel time between a nuclei origin (i) and the nucleiof destination (j):

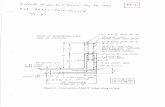

IRij ¼ tui þ tr þ th þ tuj

where:tui = Urban time penalty from the origin (i) to the exit of the

town.tuj = Urban time penalty up to coming to the final point of the

trip (j).tr = Travel time on the road.th = Travel time by rail, either conventional or high-speed rail.

th ¼ tusi þ tusj þ tc þ tm

tusi = Urban time penalty needed to get the railway station oforigin of travel by rail.

tusj = Urban time penalty needed to get the final point of thetravel (j), from railway station of destination of travel by rail to thefinal point of the travel (j).

tc = Transfer time or waiting time of a line of high-railway speedto another and waiting time at the railway station.

tm= Time within the HSR in motion.It must be clarified that the transfer time and the waiting time

at the HSR stations, are calculated in the same way, according to theservice frequency of the rails. These times are estimates asinversely proportional to the frequency of service and in the casethat the obtained value is greater than one hour, it is considered asthe transfer time and the waiting time an hour (Fig. 2).

In this regard, the frequency of high-speed rail service andmiddle-distance rail service are estimates by means of the formulaestablished by Megía (2002).

Nsði; jÞ ¼ aPiPj=D

2r

IR2n

!b

where:Pi = Population that live in the city where the station is at the

beginning of the journey by rail, expressed in thousands ofinhabitants.

Pj = Population that live in the city where the station is at theend of the journey by rail, expressed in thousands of inhabitants.

Dr = Geographical distance between the origin and destinationstation, expressed in kilometres.

IR2n = Travel time using the high-speed rail network, expressed

in hours.The number of high-speed rails is estimates through the

calibration of the parameters named a and b. To get this aim the

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of calculated travel times.

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

present frequency of existing services are used. Thus, the valuesobtained for a and b are 3.009 and 0.3224, and 0.68 for coefficientof correlation.

On the other hand, the absolute accessibility index is improves,considering the time of global shift, the cost of crossing each urbanenvironment. This intra-urban time can be decisive in the choice ofa mean of transport or another.

The estimate of the urban time has been calculated consideringthis travel time as variable depending on the characteristics of theurban core. Since the time analysis carried out in this researchconsiders all the urban areas of Extremadura and the peninsularcentres of economic activity. In considering the density of residentpopulation, the running speed and radius of the urban surface, somuch for the urban nucleus that receives the station of departureas that of arrival, are departing from the premise from that all theurban areas are considered to be circular. The population of eachmunicipality is obtained from the municipal census relative to theyear of 2012 (INE, 2012) and the urban surface of the NationalCartographic Base, 1:200,000 scale. These travel times areestimated based on the population density of the areas, througha linear fit that allocates a maximum of 80 km/h to the areas oflower density and a minimum of 20 km/h to the more populousones (Condeço-Melhorado et al., 2010).

3. Results

In order to provide a clear vision about the degree ofaccessibility to the existing stops of the HSR in Extremaduraand the degree of connectivity between this region and the IberianPeninsula, different thematic maps are generated in this regard:minimum access times to the nearest HSR station in Extremadura;minimum access times to the nearest HSR station either inside oroutside of Extremadura; improvement of the minimum accesstime of each core of Extremadura to the centres of economicactivity located 600 km away; and improvement of the absoluteaccessibility index to the peninsular centres of economic activityafter the introduction of high-speed. These mappings arecomplemented with a series of frequency histograms that analysedthe variables considered.

3.1. Minimum access time from population centres to the HSR stationsin Extremadura

First, we analyse the minimum access time from the differentpopulation centres to the nearest HSR train station in Extremadurathrough the road network.

Areas where there will be a station which have greateraccessibility and as gradually as urban areas are more remotestations will increase access time, as shown in Fig. 3. Firstly, we areable to see how the nuclei in the territory located between Badajozand Merida stations are going to have an access time to thesestations less than 20 min. As a result in these areas the tunnel effectare going to occur, since the infrastructure is established in theirterritory but resident in urban areas are not going to have adequateaccess to high-speed rail service. Secondly, there is a strip aroundstations that clearly delimits the area where are contained urbannucleus whose access time to stations is less than 40 minutes.Thirdly, this strip divides symmetrically Extremadura in terms ofaccess time. Therefore, the variable that determines mainly theaccess to the stations is the distance of separation from towns tostations and no other factors like the quality that allow access tothe stations.

Then, a histogram with the minimum access time to the HSRstations is presented.

In Fig. 4, we can glimpse that more than half of the cores ofExtremadura are located less than 40 min of access to the future of

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

Fig. 3. Map of minimum access time to the HSR stations.

Fig. 4. Histogram of minimum access time to the HSR stations.

J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx 5

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

the HSR stations. These municipalities indicate 71% population ofExtremadura.

Moreover, if we look at the percentage of the population thatlives in the area whose access is less than 20 min compared it withthe remaining areas defined by their access time, it is found thatthis is the most heavily populated area of Extremadura,concentrating in 59 municipalities, the 43% population ofExtremadura.

The areas whose access times to the stations are between 40and 80 min are considered as peripheral areas. In addition, theseareas present a low population density because there is a highnumber of population centres whose resident population is verylow. This proportion of population will have access to loweropportunities for socio-economic development to have morelimited access to stations located in the region.

On the other hand, the inhabitants of the population centres inthese peripheral and isolated areas may have less access time tothe HSR stations of adjacent provinces to Extremadura to the ones

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

located within the region. Therefore, secondly it analyses theminimum access time to the nearest stations inside and outside ofthis autonomous community, through the road network (seeFig. 5). Thick green lines represented routes taken by theinhabitants of the population centres to other HSR workstationsoutside of Extremadura.

There are inhabitants from Extremadura, who are going to getbetter access to HSR stations located in others autonomouscommunity that HSR stations placed in Extremadura. The accesstime by these inhabitants to stations outside of Extremadura ismore than 50 min. Therefore, this population are not going toimprove their accessibility, by the introduction of high-speedrailway lines. Nonetheless, it is a lacking proportion of population,only 26,568 inhabitants from Extremadura, 2.41% of totalpopulation. Therefore, it is possible to affirm that the vast majorityof the population are going to access to the stations located in theautonomous community and not to stations outside Extremadura.

3.2. Improvement of the minimum access time from the settlement inExtremadura to peninsular centres of economic activity within 600 km

Thirdly, the minimum access time of the different populationcentres from Extremadura to the peninsular centres of economicactivity that is at a distance of less than 600 km is discussed, beforeand after the introduction of high-speed railway.

On the map in Fig. 6, it can be seem as it becomes apparent thetunnel effect along the route of the HSR. Due to the fact that thereare areas crossed by the infrastructure, but in these areas do nothave access to the new infrastructure, since the access to the sameis through the stations. This effect is caused by the need that hasthe infrastructure to have a minimum separation distance betweenstations to accelerate and reach their optimal commercial speed.Therefore, in the Extremadura case, the tunnel effect shown in

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

Fig. 5. Map of minimum access time to HSR stations in other autonomous communities.

Fig. 6. Map of improved access time to the peninsular centres of economic activity within 600 km.

6 J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A methodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportationinfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx 7

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

Fig. 6 is due to the existing infrastructure and distribution, both ofthe cores from Extremadura, as to the peninsular centres ofeconomic activity less than 600 km.

This effect is evident in the area between the stations ofBadajoz, Merida and Caceres, with intervals for improvement ofaccess times no longer than 3 h compared to areas south of Badajozwith an improvement of 3.5–4.0 h and Plasencia with the longestimprovement of 4.0–4.5 h. Likewise, the longest tunnel effectoccurs in the surrounding area and to the south of the station inNavalmoral de la Mata, whose the improvement is less than 1.5–2.0 h.

In addition, the map of Fig. 6 represents globally a radial modelmoved to the east of Extremadura. The centre of the model wouldbe located outside of Extremadura, to the east of this area. Due tothe fact that the different isochrones, the model increases its valuefor improving access time from this imaginary centre located to theeast of 1.5–2.0 h, until they reach their maximum values to the westof Extremadura to 3.0–3.5 h (excluding the enhancement valuesmore than 3.5 h). This model suggests that the improvement ofaccess time to the centres of economic activity is greater howfurther away is from the urban core of the Extremadura ofassembly centres of economic activity and decreases as the urbancore from Extremadura is located closest to the whole centres ofeconomy activity. Consequently, the HSR is more effective when itis more remote from the Extremadura populations’ centre of theset of the peninsular centres of economic activity.

This model stratifies the Extremadura territory in terms ofaccessibility in six different areas, in the absence of more data toallocate different ranges of importance to the HSR stations inExtremadura. The area of a big improvement of access time is in thenorth of Plasencia and south of Badajoz: have an improvement ofthe access time between 4.5 to 4 h and 3.5 to 4 h, respectively, to bethe most remote areas of the peninsular centres of economicactivity and count with a good access to the HSR station. Even, thestation in Badajoz is included in the area between 3.5 and 4 h. Thearea of improving time between 3.5 to 4 h is between the previousarea of Badajoz and the vicinity of the highway A-66 that dividedvertically Extremadura. This area includes the stations of Caceresand Malpartida de Plasencia, although are in the perimeter. Thearea between 2.5 and 3 h embraces the station in Merida andCaceres. Therefore, it will be necessary to look at an improvementof the access roads in the urban centres to Mérida and Caceres. Theoccupied extension by the improvement of time between 1.5 and2 h is surrounding to the previous one and is the smaller surfacearea of all the others, on the contrary, highlights the big extensionof the improvement area between 1.5 and 2 h. So in Extremadura,the most part of its surface will be less favoured by the arrival of theHSR.

As shown in Fig. 7, the area of the greatest increase in accesstime corresponds to the inhabitants of 2 settlements that areequivalent to 1% of the population of Extremadura. Therefore, the

Fig. 7. Histogram of access time improvement to the peninsular centres ofeconomic activity within 600 km.

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

greatest improvement in access time to the centres of economicactivity to mainland (up to 600 km) has few potential users in thisautonomous community. It emphasizes that the second lowestpercentage of population presents an improvement of timebetween 3.5 and 4 h. This is because the fact that welcomes thecity of Badajoz, which is the most populated of Extremadura. As aresult, the HSR seems to have been conceived to connect Madridwith the most populated centres of Extremadura.

The intermediate zone, corresponding to the times of improve-ment between 2.5 and 3.5 h is the area with a larger population andmore amounts of urban centres. Therefore, the intermediateimprovement in access time to the peninsular centres of economicactivity within 600 km occurs in the most populated area inExtremadura and with more amounts of urban centres.

The area of minimum improvement in access time to thepeninsular centres of economic activity to less than 600 kmbetween 1.5 and 2 h is corresponding to approximately a quarter ofthe population of Extremadura. Then, to access the peninsularcentres of economic activity within 600 km of the ExtremaduraHSR is not an effective means of transport for the fourth part of thepopulation.

On the other hand, the HSR station that is located in Malpartidade Plasencia is several kilometres away from Plasencia. Thisnucleus is the fourth most populated city in Extremadura. For thisreason, it is analysed how the accessibility model would bemodified if the train station were in Plasencia.

Fig. 8 shows the result of relocating the HSR station fromMalpartida de Plasencia to Plasencia. Comparing the improve-ments of access times to the main centers of economic activity inthe study area, it shows how this relocation improves access timeTAV service of 15% of the municipalities located west of the stationin question, here reside the 8% of population in Extremadura. Costreduction in travel time for these municipalities is estimated atbetween three hours and four hours. The main reason for thispalpable improvement in the areas is that Plasencia acts as thehead city of Extremadura North, implying better infrastructuresaccess road than in the case of Malpartida. This certainly improvesthe access measured as time to the HSR service.

If Fig. 6 is compared with Fig. 8 it can be seen as many townssituated east of Plasencia increase by 3.5 h access time. Therefore,we should ask, depending on the demand of the railway servicethat would have in these nuclei, whether it is worth implementingthe railway station in Plasencia or Malpartida de Plasencia.

3.3. Absolute accessibility

Finally, we have analysed the degree of interconnection of eachof the Extremadura urban cores with all the centres of peninsulareconomic activity, linking with the potential of the population ofthese centres with the minimum access time through the network,the major urban agglomerations peninsular before and afterimplementation of the HSR in Extremadura (Fig. 9).

In the map, it can be seen as the entire territory of Extremaduraimproves its index of absolute accessibility to peninsular centres ofeconomic activity. Therefore, the implementation of the HSR inExtremadura ameliorate the connectivity of the autonomouscommunity. Consequently, the improvement of accessibility favorsthat the region passes to be a peripheral region to become a moreintegrated territory to be a national and an international leveltogether with Portugal.

However, the greatest improvement in the absolute accessibili-ty index that occurs within Extremadura is in the peripheral areas.These areas are situated at south of the station in Badajoz andaround the railway station located in Malpartida de Plasencia, ashere the major benefit is going to be gathered by the arrival of theHSR.

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

Fig. 8. Map of improved access time to the peninsular centres of economic activity within 600 km, considering the HSR station in Plasencia instead of Malpartida de Plasencia.

Fig. 9. Map of absolute improvement in accessibility to the peninsular centres of economic activity.

8 J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A methodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportationinfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx 9

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

The inland area, which contains the minimum improvement inaccessibility, is located in the half of the western in Extremadura,where shows that there is a smaller number of transport routes oflarge capacity because in this area there are a lot of smallmountains. Therefore, the orography of the territory acts as abarrier and restricts the possibilities of territory development.Nonetheless, the station located in Navalmoral de la Mata that isinside this area is not going to get better accessibility, since now itis close to Madrid that is the greatest city in Spain.

On the other hand, the areas of intermediate improvement arethe most extensive. However, the HSR stations that are located inthis area are Merida and Caceres, though the situation of thestations with respect to the network is very close. Therefore, thelowest improvement of accessibility may be due to the transportnetwork, which connects the capital with the autonomicpeninsular centres of economic activity, is not as effective as theinfrastructure network of the other stations in the HSR (Fig. 10).

The greatest improvement of absolute accessibility correspondsto only 12 towns that are indicating 4% of the inhabitants ofExtremadura.

The greatest number of population centres and inhabitants is inthe area of improving absolute intermediate accessibility. As aresult, the insertion of the high-speed railway infrastructure in theexisting transport network causes a degree of improvement ofintermediate connectivity for the greater part of the population ofExtremadura. In a consequence, improving the degree of connec-tivity peninsular caused by the HSR will be equal between 37% ofthe population centres and 92% of the population from Extrem-adura.Therefore, the implementation of the HSR in Extremadurahas been conceived as an improvement in the degree of connectionof the most populated towns of Extremadura.

On the other hand, the space of less improvement of absoluteaccessibility embraces only 17% of the population. However, it isnecessary to improve the accessibility of the urban centres locatedin this space and to avoid the inequality of opportunities of socio-economic development that will occur in 89 urban centres locatedin this area, the introduction of the HSR in Extremadura.

4. Conclusions and proposals

The first conclusion, in general, is that a proper use of theaccessibility indicators together with the application of analysistools of own networks of a GIS, and allows analyse efficiently andcorrects the impact of the new railway infrastructures raised by thePITVI 2012–2024. In addition, these analyses can be performedbefore and after the implementation of these infrastructures,which increases the ability to detect interesting changes for thistype of research.

Another conclusion drawn from this study (analysis ofminimum time) is that the infrastructure seems to have beendesigned to connect to the core with a larger population (43% of the

Minimum Low Minor Notewort hy Hi gh MaximumNumber of tow ns 89 52 62 110 39 12Cumulative relative frequency (%) 23 37 53 82 92 95Population (%) 17 7 14 41 17 4

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Fig. 10. Histogram of absolute improvement of the index of absolute accessibility tothe peninsular centres of economic activity.

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

population). Thus, while the most populated towns are minimumaccess times to the stations close to 30 min, there are a significantpercentage of cores whose times are higher than 60 min (21% of thesettlements). Nevertheless, the latter receives low population(11%). On the other hand, the analysis of minimum access times tothe centres of population from Extremadura to the HSR stationsboth in Extremadura, as in other neighbored autonomouscommunities shows that only 2.41% of the population would berequired of a station of the HSR outside of Extremadura. Therefore,according to the spatial localization of the urban nuclei, theexisting terrestrial infrastructure and location of the railwaystations, the new railway infrastructure offers service to most ofthe residents in Extremadura.

On the other hand, the analysis of the improvement in accesstime to the centres of economic activity to less than 600 km allowsobserving, as the territory becomes a discontinuous space andpolarized. The poles are the cities that in the future will have a HSRstation. However, the degree of polarization of each of these citiesis determined by the above fact, as well as by the benefit obtainedby the reduction in access time to the centres of economic activitywithin 600 km.

Regarding the results obtained by placing HSR station inPlasencia instead of Malpartida de Plasencia, it stands out asterritorially increases the service area of HSR. It would be thereforebe appropriate to consider whether in the expanded service areathe future demand to use the HSR would be enough to decide tochange the location of this station. Obviously, before it is implantedthe high-speed railway infrastructure in the territory.

In the third place, the results obtained the improved index ofabsolute accessibility determine that the deployment of high-speed in Extremadura improves the connectivity of the autono-mous community with the mainland. In a consequence, the HSRfavors that the region passes from a peripheral region to become amore integrated territory in a national and international level withPortugal. However, this improvement in the intraregional penin-sular connectivity produces an asymmetry,since such improve-ment compared to the peninsular connectivity is much higher inthe peripheral areas that in central areas. Therefore, it will benecessary to take action on the last territories that balance theirpotential possibilities of socio-economic development respect tothose territories more favoured.

Finally, the first two analyses determine that this high-speedrailway service fulfils the aim raised in the PITVI 2012–2024. Itoffers the major capacity of service to the major quantity ofExtremadura population and excludes to a low quantity ofpopulation use of the HSR. Nevertheless, the third and lastanalyses show that the implementation of the high-speed railwaywill produce an enormous hierarchical organization of theterritory.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewers their constructive commentsthat have helped to improve the final version of the paper.

References

Albalate, D., Bel, G., 2014. The Econoics and Politics of High-Speed Rail. LexingtonBooks, Maryland.

Auphan, E., 2002. Le TGV Méditerranée: un pas décisif dans l'évolution du modèlefrançais à grande vitesse. Méditerranée 98 (1–2), 19–26.

Banister, D., Berechman, J., 2003. Transport Investment and EconomicDevelopment. UCL Press, London.

Bauman, Z., 2000. Liquid Modernity. Wiley, Minneapolis.Bellet, C., Casellas, A., Alonso, M., P, 2010. Infraestructuras de transporte y territorio:

los efectos estructurantes de la llegada del tren de alta velocidad en España.Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 52, 143–163.

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003

10 J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego et al. / CSTP xxx (2015) xxx–xxx

G ModelCSTP 73 No. of Pages 10

Biehl, D., 1986. The Contribution of Infrastructure to Regional Development: Annex,vol. 2. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities,Luxembourg.

Bristow, A.L., Nellthorp, J., 2000. Transport project appraisal in the European Union.Transp. Policy 7 (1), 51–60. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0967-070X(00)10-X.

Brocard, M., 2009. Transports et territoires: Enjeux et débats. Ellipses Marketing,Paris.

Bröcker, J., Capello, R., Lundavist, L., Meyer, J., Rounwendal, J., Schneekloth, N.,Spairani, A., Spangenberg, M., Spiekermann, K., Van-Vuuren, D., Vickerman, R.,Wegener, M., 2003. Territorial Impact of EU Transport and TEN Policies.Luxembourg: The European Spatial Planning Observatory Network (ESPON),vol. 2. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities,Luxembourg.

Community EE, 1999. European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP): Towardsbalanced and sustainable development of the territory of the European Union,vol. 1. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities,Luxembourg.

Condeço-Melhorado, A., Gutiérrez, J., López, E., Monzón, A., 2010. El valor añadidoeuropeo de los proyectos transnacionales (TEN-T): una propuesta metodológicabasada en los efectos de desbordamiento, accesibilidad y SIG. Paper presentedat the Actas del XIV Congreso Nacional de Tecnologías de la InformaciónGeográfica, Seville, September 2010.

De Ureña, J.M., 2012a. High-speed rail and its evolution in Spain. In: Ureña, J.M. (Ed.),Territorial Implications of High Speed Rail. A Spanish Perspective. AshgatePublishing, Limited, Farnham p. 16.

De Ureña, J.M., 2012b. Territorial Implications of High Speed Rail. A SpanishPerspective, first ed. Ashgate Publishing, Limited, Farnham.

Dematteis, G., 1995. Progetto implicito, II Contributo Della Geografia Umana AlleScienze Del Territorio. Strumenti Urbanistici, Vol Sociologia Dell'ambiente, DelTerritorio E Del Turismo. second ed. Franco Angeli, Milan.

Escolano, S., 2012. Territory and high-speed rail: a conceptual framework, In: Ureña,J.M. (Ed.), Territorial Implications of High Speed Rail. A Spanish Perspective. firsted. Ashgate Publishing, Limited, Farnham, pp. 22.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2012. Padrón Municipal. Ministerio de Fomento,Madrid.

Gutiérrez, J.A., Mora, J., Domínguez, P., Jaraíz, F.J., 2010. Accesibilidad De LaPoblación a Las Aglomeraciones Urbanas De La Península Ibérica, 89. Finisterra-Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, pp. 107–118.

Fotheringham, S., Wegener, M., 2000. Spatial Models and GIS: New Potential andNew Models. Taylor & Francis, Oxford.

Fürst, F., Schürmann, C., Spiekermann, K., Wegener, M., 2000. The SASI model:demostration example (trans: Planning IoS). Reports from the Institute ofSpatial Planning, vol. 51. University of Dortmund, Dortmunt.

Megía, M.J., 2002. Oferta de transporte de viajeros por ferrocarril entre ciudadesimportantes de la Unión Europea. Estudios de Construcciín y Transportes 95,71–92.

Monzón, A., Gutiérrez, J., López, E., Madrigal, E., Gómez, G., 2005. Infraestructuras detransporte terrestre y su influencia en los niveles de accesibilidad de la Españapeninsular. Estudios de construccién y transportes 103, 97–112.

García, J., 2000. La medida de la accesibilidad. Estudios Construcciín Transportes 88,95–110.

Geurs, K.T., Ritsema, J.R., 2001. Accessibility measures: review and applications:evaluation of accessibility impacts of land-use transport scenarios, and related

Please cite this article in press as: J.A. Gutiérrez Gallego, et al., A minfrastructure: Application to the high-speed rail in Extremadura, CSTP

social and economic impacts. Research for Man and Enviroment, vol. 6.Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, Bilthoven.

Gutiérrez, J., 2001. Location, economic potential and daily accessibility: an analysisof the accessibility impact of the high-speed line Madrid–Barcelona–Frenchborder. J. Transp. Geogr. 9 (4), 229–242. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6923(01)17-5.

Gutiérrez, J., Monzón, A., Piñero, J.M., 1994. Accesibilidad a los centros de actividadeconémica en España. Revista de obras públicas 141 (3331), 34–49.

Klein, O., Claisse, G., Pochet, P., 1997. Le TGV-Atlantique: entre récession etconcurrence. Laboratoire d'Economie des Transports, Paris.

López, E., Ortega, E., Condeço-Melhorado, A.M., 2009. Anólisis de impactosterritoriales del Plan Estratçgico de Infraestructuras y Transporte 2005–2020:cohesián regional y efectos desbordamiento. ICE: Revista de economía 848,159–172.

Martí-Henneberg, J., 2013. European integration and national models for railwaynetworks (1840–2010). J. Transp. Geogr. 26 (0), 126–138. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.09.004.

Martínez, F.J., Araya, C.A., 2000. A note on trip benefits in spatial interaction models.J. Reg. Sci. 40 (4), 789–796.

Menéndez, J.M., Coronado, J.M., Rivas, A., 2002. El AVE. en Ciudad Real y Puertollano.Cuadernos de Ingenieria y Territorio 2, 53–69.

Ozbay, K., Ozmen-Ertekin, D., Berechman, J., 2003. Empirical analysis of relationshipbetween accessibility and economic development. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2 (97),97–119. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9488(2003)129:2(97).

Plassard, F., 1997. Les effects des infraestructures de transport, mòdeles etparadigmes. Infrastructures Transprot Territoires 15.

Potrykowski, M., Taylor, Z., 1984. Geographía del transporte. Ariel Editorial, S.A.,Barcelona.

Ureña, J.M., Escobedo, F., Serrano, R., 2006. Metodología e hipótesis para laevaluación de las consecuencias de la red de Alta Velocidad Ferroviaria en laorganización territorial española. Paper Presented at the VII Congreso deIngeniería del Transporte, Ciudad Real, Juny 2006.

Reques, P., De Cos, O., Marañón, M., 2012. Demographic and socio-economic contextof spatial development in Spain, In: Ureña, J.M. (Ed.), Territorial Implications ofHigh Speed Rail. A Spanish Perspective.. first ed. Ashgate Publishing Limited,Farnham, pp. 27.

Terribas, B., 2011. La vuelta al mundo en alta velocidad. Revista Ministerio Fomento608 (2), 15.

Varlet, J., 2000. Dynamique des interconnexions des réseaux de transports rapidesen Europe: devenir et diffusion spatiale d’un concept géographique. Flux 5–16.

Vickerman, R., 1997. High-speed rail in Europe: experience and issues for futuredevelopment. Ann. Reg. Sci. 31 (1), 21–38. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001680050037.

Vickerman, R.W.,1994. The Channel Tunnel and regional development in Europe: anoverview. Appl. Geogr. 14 (1), 9–25. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0143-6228(94)90003-5.

Vickerman, R.W., 2012. High-speed rail—the European experience, In: Ureña, J.M.(Ed.), Territorial Implications of High Speed Rail. A Spanish Perspective. first ed.Ashgate Publishing Limited, Farnham p. 16.

Zembri, P., 2005. El TGV, la red ferroviaria y el territorio en Francia. Ingeniería yTerritorio 70 (2), 20.

ethodology to assess the connectivity caused by a transportation (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2015.06.003