A Crystal Elephant from the Kunstkammer of Catherine of Austria

Transcript of A Crystal Elephant from the Kunstkammer of Catherine of Austria

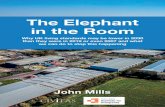

A CRYSTAL ELEPHANT FROM THE "KUNSTKAMMER"OF CATHERINE OF AUSTRIA*

VON ANNEMARIE JORDAN GSCHWEND

Throughout the 1550's Cathenne of Austna (1507—78) made significant purchases of imported luxury waresfrom the Eastern colonies for her personal collection and treasury housed in the royal palace of Lisbon. A rockcrystal elephant from India, today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, was obtained from a Lisbongoldsmith and presented by the Portuguese Queento herdaughter-in-law,Joanna of Austria (1535-73), in 1553.Later, this saltcellar possibly entered the Austrian imperial collections äs part of Rudolf II's "Kunstkammer" inPrague.

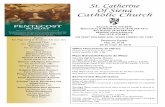

Wolf gang Born first published in 1936 a series of eastern objects from the f ormer Habsburg imperial collections,located today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum'. Among these, was an Indian saltcellar in the form of an elephant,dating from the fifteenth Century (/7g. 85 )2. Both Donald Lach in his seminal work on Asia, Europe and the impactof the east on the visual arts, and Born suggested that the elephant had formerly belonged to Archduke Ferdi-nand II of Tyrol; although, there has never been any documentation to substantiate this3. Rudolf Distelberger hasdisputed that the elephant had ever belonged to the Schloss Ambras collection4. Until it was first recorded m the1750 Kaiserliche Schatzkammer mventory, the elephant's provenance and history remams vague5.

In 1550 Catherine of Austria purchased from the Lisbon goldsmith, Francisco Lopez6, a crystal elephant for theamount of 3600 reats. A patent-letter dated September 30 details not only this purchase; but also, the commission

*) I would like to thank both Drs. Elisabeth Scheicher and Rudolf Distelberger for their assistance with this present work. They were extremelygenerous with their observations and suggestions.

') W. BORN, Some Eastern Objects from the Habsburg Collections, Burlington Magazine (1936), pp. 269-276, pl. II-D.2) KMV, inv. no. 2320, 7,3 x 9,4 x 5 cm. See Os Descobrimentos Portugueses e a Europa do Renascimento, XVII Exposicäo Europeia de Arte,Ciencia e Cultura, Casa dos Bicos, Lisbon, 1983, cat. 47, pp. 105-106; R. SKELTON, Indian Art and Artefacts in Early European Collecting,The Ongin of Museums. The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, Oxford, 1985, p. 274; India! Art andCulture 1300-1900, New York, 1985, cat. 77, pp. 132-133; Circa 1492, Washington, DC, 1991, cat. 14, pp. 130-131.The dating of this piece is difficult due to the crystal medium. Born placed it in the third Century B. C. and most recently in the Circa 1492exhibit in Washington, DC, it was dated to the Bahmanid dynasty of the Deccan Sultanate (13th to early 16th Century) based on stylisticcomparisons with contemporary sculpture and elephant depictions.3) BORN, op. cit., p. 275, and D. LACH, Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. II: A Century of Wonder, Book One: The Visual Arts, Chicago,1970, p. 27, pl. 9. The saltcellar was not recorded in the 1595 Ambras inventory. See E. SCHEICHER, O. GAMBER, K. WEGERER, & A. AUER (eds.),Die Kunstkammer. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Sammlungen Schloss Ambras, Innsbruck, 1977, and E. SCHEICHER, Die Kunst- undWunderkammern der Habsburger, Vienna, 1979.4) According to a letter from Rudolf Distelberger dated September 22, 1989.5) Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 10,1889, p. ccv: Ein kleiner elephant, worauf ein dintenfäszel,zusammen von crystal, die fassung massiv von gold und schwarz geschmolzen.') Francisco Lopez remains to be identified. It is known from Catherine's household payment books that he was not an artisan permanentlyemployed by the Queen. In 1550 a total of 430 craftsmen worked in precious metals in Lisbon with 53 ateliers for goldsmiths and 45 forsilversmiths. European (Flemish, Spanish, French, Italian and German), Oriental and Portuguese gold- and silversmiths practiced their tradeon the Ruas Nova and Ounvesaria. Everything from drugs to textiles were sold in shops located in the streets of the lower sections of Lisbon.Each year alone two thousand gemstones (rubies, diamonds and emeralds) were sold. See A. JORDAN, The Development of Catherine ofAustria's Collection in the Queen's Household: Its Character and Cost (Ph.D in progress, Brown University), Parts One & Three; JoAoBRANDÄO, Tratado da magestade, grandeza e abastan^a da cidade de Lisboa na 2a metade do seculo, Lisbon, 1923, pp. 79-80; DAMIÄO DE Gots,RAUL MACHADO (trans.), Lisboa de quinhentos, Lisbon, 1937, p. 48; A. VIEIRA DA SILVA, As muralhas da ribeira de Lisboa, l Lisbon, 1940-1941, pp. 91-112; R. DOS SANTOS, A India Portuguesa e äs artes decorativas, Belas Artes 7 (1954), pp. 3-16; J. COUTO and A. M. GoNgALVES,A Ounvesaria em Portugal, Lisbon, 1962, and LACH, op. cit., pp. 10-14.

122 ANNEMARIE JORDAN GSCHWEND

85. Elephant Saltcellar, Indian rock crystal, 13th to 16th Century (Deccan Sultanate), 7,3 x 9,4 x 5 cm. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum,Kunstkammer, inv. no. 2320. Medieval salt, jacinth eyes, gold tusks tail and ornamentation added in Lisbon in 1550

the Queen gave Lopez to polish, buff and decorate the elephant with gold ornamentation (Appendix)7. In total33,810 reais was spent in labour and expenses for material, and an additional 1100 reais spent for a small iron boxwith silver clasps, in which it was placed. In this latter document, äs well äs, in Catherine of Austria's 1550-54treasuryandwardrobeinventory (/ig. 86), the elephant is minutely described:... a crystal elephant with a saltcellarabove and a lid topped by a. green andpink enamelled rose, entirely decorated with fine gold, jacinth eyes and gold

7) Archive Nacional de Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, Corpo Chronologico I, maco 85, doc. 56. See JORDAN, op. cit., Part Two: Appendix 5:cat. 8. This patent-letter was partially published with the Vienna elephant in 1983 and mis-interpreted in relation to its provenance fromCatherine's collection. See XVII Exposicäo Europeia de Arte, Ciencia e Cultura, Casa dos Bicos, Lisbon, 1983, cat. 47, pp. 105-106.

A CRYSTAL ELEPHANT FROM TUE KUNSTKAMMER OF CATHERINE OF AUSTRIA 123

eil aute:

y! "*'" J]. ' " Vleptj 33 U £ < *

i afL^Jnn^ G l U 4-««o/f>nn"r £ l ö ü/ l O . d< »M«O GI£ l 'uju f«.

oo

inCii.'llin/'iBltVU« l / . l 5

o»£ cn «

OKIIC C £n-ft.mn/"j j D y t O CO

.^«b* (Äartniccy» Jl *"&««.hilito < ^ J t"

86. Inventory of Catherine of Austria's gems, jewels and treasury, 1550-54, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, N.A. 794, fol. 88r.

tuskss. Catherine's inventory and patent-letter noted the weight of the elephant in 1550 - crystal and gold - äs onemarco, three ounces and two and half eighths, approximately 394.5 grams9. In the margin, next to this inventoryentry, the Queen's wardrobe scribe added that the elephant with its iron casket had been presented by Catherineto her mece and daughter-in-law, Joanna of Austria, äs a gift on October 5, 1553. In addition, the patent-letter ofpayment made to Francisco Lopez was cited äs well.

There are striking coincidences and similarities between the Vienna elephant and the Lisbon document,particularly in the description of the gold decoration, tusks, and jacinth eyes. Both the lid of the saltcellar and theeyes of the Vienna elephant are now lost, which according to the 1891 Kunsthistorisches Museum inventory werealso jacinths. The present weight is 279 grams. If originally there was an iron casket for storage, it is no longerextant. Elisabeth Scheicher and Rudolf Distelberger consider the elephant of Indian ongin, the saltcellar a

8) Archivo Nacional de Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, N. A. 794, fol. 88r: en lixboa a xbij dotubro de mil bei [l SSO] recebeo a camareira dona metiadandrade do thezoureiro afoaro lopez hun elifante de xpal [cnstal] com huapeca en riba a maniera de saleiro com seu tapador e tudo guarnecidodouro fino e o tapador ten buä rosa esmaltada de verde e rosicre que pesa todo juntamente xpal e ouro hun marco tres on^as e duas oytavas emein, os colmulhoös deste elifante säo douro e em cada olho tem hum jacinto ouve conhecimento em forma, and JORDAN, op. cit., Part Two:Appendix 1: Ms. 2.') A weight conversion is provided in: NUNO VASSALLO E SILVA, Um gomil do tesouro de D. Joäo III. Ourivesaria de Aparato dos Seculos XVe XVI, Artes Plästicas 6 (1990), pp. 10-13. One old Portuguese marco is 229.44 grams, one ounce 28.68 grams and one eighth 3.585 grams.

124 ANNEMARIE JORDAN GSCHWEND

medieval piece added later, defeating Born's supposition that both the elephant and sah were of the same periodand origin10. The author proposes that the Vienna elephant and the one purchased by Catherine of Austria in 1550are one and the same; this elephant being one of the only examples of its kind known today.

By the mid-sixteenth Century, Lisbon had become a vast emporium for eastern products and Catherine ofAustria greatly profited from this advantageous Situation11. No other contemporary collector avid for Asian warescould compete with her accessibility12. Judging from the quantity of imported objects recorded in her inventories,Catherine of Austria may have owned the largest non-European collection in the mid-sixteenth Century, and onlylater Habsburg rulers - Ferdinand I, Philip II, Rudolf II and Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol - had formedcollections of "Indian"13 objects of equal importance14. Catherine of Austria's collection was not simply amiscellany of curiosa imported from overseas, äs they were, for instance, in the collection of her brother,Charles V15. She was the first Habsburg princess to have systematically collected objects from the East16.

Therefore, there is little reason to doubt an Indian origin for Catherine's elephant purchased in 1550, thefunction of which was to serve äs an exotic Kunstkammer object in her collection. The Portuguese court held, sincethe reign of Manuel I (1495-1521), a special affection for elephants and their iconography which not onlyrepresented a fascination of India and Africa; but also, the triumphal Portuguese conquests of these lands17. Theelephant symbolized throughout the Renaissance, power, strength, dihgence and virtue, and held particularemblematic and allegorical significance for Catherine of Austria18.

The addition of the medieval sah, jacinth eyes, gold decorations and tusks commissioned by Catherine ofAustria demonstrates the common practice followed by Portuguese goldsmiths during the sixteenth Century torework and elaborately ornament in gold gems, jewels and naturaha (i. e. coconut shells, bezoar stones, musk,civet) imported and sold in Lisbon. Catherine probably intended to use the elephant sah not only äs a ceremonialobject; but also, äs a functional and decorative one for the Queen's table. Other documentation found in theLisbon archives prove that she often made frequent purchases of crystal, commissioning, for example, in 1552twenty-four pairs of eye-glasses - obviously a novelty - for her court ladies, buttons and mirrors cut from pieces

10) BORN, op. cit., p. 275, who proposed that the Vienna elephant was originally conceived of äs a chess-piece.") NUNO VASSALLO E SILVA, Subsidios para o estudo do comercio das pedras preciosas ein Lisboa no seculo XVI, Boletim Cultural daAssembleia Distrital de Lisboa (1989), pp. 3-39.12) Catherine of Austria often presented her Habsburg relatives with oriental and exotic gifts. Joanna of Austria, for instance, received in 1566porcelam from India sent to her by Catherine. See SOUSA VITERBO, O theatro na corte de D. Fihppe II, Archive Histörico Portugues (1903),pp.5-11.13) The term "Indian" was a generic one m the sixteenth Century and m contemporary European inventories was often used to denote any objectthat stemmed from the East. Very rarely were countries of origin specified in these inventories. However, in Catherine of Austria's inventoriesthe provenance of objects was consistently differentiated and recorded (i. e. Ceylon, China, India). See LACH, op. cit., pp. 46-55.w) For a general discussion of Austnan and Spanish Habsburg patronage and collecting see LHOTSKY, op. cit.; H. TREVOR-ROPER, Princes andArtists. Patronage and ideology at four Habsburg courts 1517-1633, New York, 1974; W. L. EISLER, The Impact of Charles V upon the VisualArts, Ph. D diss., Pennsylvanma State University, 1983; M. MORÄN and F. CHECA, El Coleccionismo en Espana. De la cämara de maravillasa la galena de pinturas, Madrid, 1985, and Las Colecciones del Rey. Pmtura y Escultura. IV Centenano del Monasterio de El Escorial, Madrid,1986.

15) LACH, op. cit., 1970, p. 23; N. HORCAJO, Carlos I y los amuletos de turquesas, Goya 138 (1977), pp. 350-353; SCHEICHER, op. cit.,pp. 186—188; EISLER, op. cit., pp. 125-177, and MORÄN and CHECA, op. cit., pp. 41-53. Both Lach and Scheicher concur that Charles V's interestin Asian and American curiosities extended in so far äs these objects glorified the Habsburg dynasty. Eisler posits a counter argument, whileMoran and Checa argue that Charles V founded a true exotica collection later expanded by Philip II, who conscientiously amassed a numberof eastern objects.For a hsting of the American items in Charles V's 1561 inventory see Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des AllerhöchstenKaiserhauses, 12,1891, reg. no. 8455, and VICENTE DE CADENAS Y VICENT. Hacienda de Carlos V al Fallecer en Yuste, Hidalguia, 1985. It shouldbe remembered that despite Charles V collecting some curiosities, Catherine of Austria had already been amassing these sorts of objects inlarge quantities since the mid- to late 1530's, if not earlier.") EISLER, op. cit., p. 159, credits Catherine's brother, Ferdinand I, äs being the first Habsburg to demonstrate a true interest in colonialartefacts. However, Catherine's position äs an oriental collector should be re-evaluated. It appears from a Corpo Chronolögico document(Archive Nacional de Torre do Tombo, Lisbon) dated September 6,1563 that Ferdinand was aware of Catherine of Austria's access to Indianobjects and tned to obtain ten pieces of amber through her agent in Antwerp, who in turn wrote Catherine, inquiring if she could get betterpieces for him in Lisbon. See JORDAN, op. cit., Part Two: Appendix 6: cat. 7.") Manuel I made daily outings riding his elephants, recalling the triumphal parades of the military generals of Rome. See DAMIÄO DE Gols,Chronica do felicissimo rei Dom Emanuel, reprint Coimbra, 1949, 2, p. 84, and LACH, op. cit., pp. 135-136.ls) LACH, op. cit., pp. 149—150. For more on the symbohsm of the elephant in art see W. HECKSCHER, Bernini's Elephant and Obelisk, ArtBulletin 29 (1947), pp. 155—182. Catherine of Austria built a royal pantheon in the San Jerömmos Monastery in Belem between 1570 and 1572.She commissioned the tombs to rest upon marble elephant caryatids; emblems in this case of Christian virtue.

A CRYSTAL ELEPHANT PROM THE KUNSTKAMMF.R OF CATIIERINE OF AUSTRIA 125

of Indian rock crystal19. Catherine's 1550-54 inventory also listed another crystal saltcellar in the shape of a dogwith a boat on his back20. The same inventory described Indian crystal spoons with rubics worked in "Ceylonese"style21. In 1570 Catherine purchased a large quantity of crystal vessels, cups and Utensils encrusted with rubies andemeralds from India22.

It may be conjectured that the Vienna elephant ongmated from Cathenne's collection, taken to Spam by Joannaof Austria when she returned there in May 1554, after the untimely death of her spouse, Prince John of Brazil. Theelephant does not appear in a 1573 inventory of her collection of relics, portraits and Kunstkammer objects in theDescalzas Reales Convent m Madrid23. Joanna of Austria may possibly have presented it to Rudolf II during hisSpanish residency between 1564 and 1571, explaining its later appearance in the imperial collections24. If not, whenpart of Joanna's collection was sold in 1573, the elephant may have been purchased by Rudolfs ambassador inMadrid, Hans Christopher Khevenhüller25. Unfortunately, neither Rudolf IFs 1619 or 1621 Prague inventoriesof "Indian" objects mention this piece26. Interestingly, the present weight of the Vienna saltcellar, if the missinglid and eyes were extant today, would approximate that of the elephant purchased by Catherine of Austria anddecorated by Lopez. Despite the probabihty that the Vienna elephant had formerly belonged to Catherine ofAustria, this proposed Portuguese provenance must remain open until further documentation is found.

APPENDIX

Arquivo Nacional do Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, CORPO CHRONOLÖGICO I, mac.o 85, doc. 56, September 30,1550:

Alvara da Ramha D. Cathanna em que mandou aos contadores de sua caza levar em conta e despeza a AlvaroLopez seu thezoureiro 33$810 rs que despendeu por seu mandado em compra e guarnigäo de hum alifante decristal que mandou comprar e guarnicer de ouro fino a Francisco Lopez Ourives.

Contadores da mmha casa mando vos leveis em conta e dcspesa a Alvaro Lopez meu thezoureiro tnnta e tresmil oytocentos e dez rs [reais] que despendeo per meu mandado em compra e guarnic,äo de hun alifante de cristalque mandey comprar e guarnecer douro fino a francisco lopez ourives pella maneyra abaixo declarada

De compra do alifante de cristal tres mil e seiscentos rsDe o afinarem e polirem e concertarem no que foy necesario dous mil e iiij centos rsPer a guarnigäo delle vinte e cinquo cruzados e meyo douro a Rezäo de quatrocentos e vimte rs por cruzado

que valen dez mill setecentos e dez rsDe feytio que pagou ao dito ourivez dezaseis mill rs

") Archive Nacional de Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, Corpo Chronolögico II, maco 243, doc. 59, and JORDAN, op. cit., Part Two: Appendix 5:cats. 38 and 73.2°) Archive Nacional de Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, N. A. 794, fol. 314, item 5: E bum cacborinho do dito xpal[cristal] con hua barco em ribadele e con sua tapadorcinho.21) Archive Nacional de Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, N. A. 794, fol. 73r.22) JORDAN, op. cit., Part Three.23) C. PEREZ PASTOR, Inventarios de los bienes que quedaron por fin y muerte de Dona Juana, Prmcesa de Portugal, Infanta de Castilla, 1573,Memorias de la Real Academia Espanola IX (Madrid, 1914), pp. 315-353.24) Other gifts given by Joanna were discussed in a letter dated Octobcr 4,1564 from Adam von Dietrichstein to Maximilian II, informing himthat Joanna of Austria had presented the Austrian Archdukes, Ernest and Rudolf, with rings set with rubies, each worth 1,000 ducats. SeeJahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 13,1892, reg. 8656, p. XXIX: die Prinzessin von Portugal habeden Erzherzogen Rudolf und Ernst jedem einen Ring zum gescbenk gemacht, darinnen ain schonen rubin und ier durchlauchtpett schaft danngeschnitten, gar sauber gefast; ist ain jeder ob tausent dukhaten gar wol wert.2') Khevenhüller was ambassador to Spain from 1572-1606 and in this interim acted äs an agent for Rudolf II making important purchases ofgems, exotic and unusual goods from the Orient and paintmgs. See LHOTSKY, op. cit., pp. 277-78.26) H. ZIMMERMAN, Das Inventar der Prager Schatz- und Kunstkammer vom 6. Dezember 1621, Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungendes Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 25, 1905, 2, pp. XIII-IXXV; R. BAUER and H. HAUPT, Das Kunstkammerinventar Kaiser Rudolfs II.1607-1611, Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien, 72, 1976, pp. VII-191; R. DISTELBERGER, The Habsburg Collections inVienna during the Seventeenth Century, The Origin of Museums. The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe,Oxford, 1985, pp. 39^16, and R. DISTELBERGER, Die Kunstkammerstücke, Kunst und Kultur am Hofe Rudolfs II., Prag um 1600, Freren, 1988,pp. 437-573.

126 ANNEMARIE JORDAN GSCHWEND: A CRYSTAL ELEPHANT PROM THE KUNSTKAMMER

De hua caixa com seus fechos de prata mill e cem res que fazem em soma os ditos xxxiij mil biij centos [e] x rs[reais] que Ihe levareis em conta per este mandado com conhecimento em forma de dona mecia dandrade minhacamareira feito por seu escnväo e asinado per ambos em que declare o peso do dito ahfante e o feitio delle e queIhe he carregado em receyta e que no assemto delle fica posta verba que ouve o dito ourivez em voz pagamentodo dito feytio/antomo daguiar o fez en Lixboa o derradeiro dia de setembro de mil bL [qumhentos e cmquenta]/pero fernandez o fiz escrever

RaynhaRecebeo francisco lopez ourivez do thezoureiro alvaro lopez os trynta e tres mill oytocentos e dez rs contheudos

neste alvara em lix a vüj dotubro 1550francisco lopez diogo martms

Recebeo dona mecia dandrade ama da princesa de castela que deus tem e camareira da Rainha Nosso Senhorado thezoureiro alvaro lopez o elifante de xpal goarnecido douro contheuda e da maniera que neste mandado sedeclara que pesou ouro e xpal todo juntamente hum marco e tres oncas e duas oytavas e meia o quäl elifante ficacarregado em Receita sobre a dita camareira comopesoe sinaes del per mim diogo martins escriväo de seu carreguoe he por verdade Ihe passey conhecimento em forma em que a dita camareira assmou em hsboa a 8 doutubro debei"dona mecia dandrade diogo martins

TranslationPatent-letter of Queen Catherine of Austria in which she ordered her comptrollers to take into account the

expenses made by her treasurer, Alvaro Lopes, for the amount of 33,810 reais spent by her Orders for the purchaseand decoration of a crystal elephant which she bought and ordered to decorate in fine gold from the goldsmith,Francisco Lopez

Comptrollers of my house I command you to take into account and expense the amount of 33,810 reais spentupon my Orders by my treasurer alvaro lopez for the purchase and ornamentation of a crystal elephant which Ibought and ordered decorated with fine gold from the goldsmith francisco lopez in the manner declared below:

the purchase of a crystal elephant 3,600 reaisfor the necessary buffing, polishing and repair 2,400 reaisfor its decoration 25 and a half cruzados of gold in the value of 420 reais per cruzado for the total value of

10,710 reaisfor the work which was paid the goldsmith 16,000 reaisfor a box with silver clasps 1,100 reais which make the total of 33,810 reais to be taken into account with this

mandate with a receipt signed by dona mecia dandrade my maid of honor written by her scribe and countersignedby both in which the weight of the said elephant and the said work is declared, accounted for [in the wardrobeinventory], and that next to this item entry it should be noted that the said goldsmith received payment for thesaid work/executed by antonio daguiar in Lisbon the last day of September 1550/written by pero fernandez

Queenfrancisco lopez goldsmith received from the treasurer alvaro lopez the 33,810 reais contained in this patent-

letter in lisbon the 8 of october 1550francisco lopez diogo martins

dona mecia dandrade nurse of the princess of castile whom God has and maid of honor of the Queen Our Ladyreceived from the treasurer alvaro lopez the described crystal elephant decorated with gold and in the manner inwhich it is declared in this mandate which weighed with gold and crystal one marco and three ounces and twoeighths and a half[.] the said elephant remains in receipt of the said maid of honor with the said weight anddescription written by me diogo martins her scribe and it is the truth that I wrote this receipt signed by the saidmaid of honor in lisbon 8 october 1550dona mecia dandrade diogo martins