a case study of color-customised lipstick choices - DiVA Portal

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of a case study of color-customised lipstick choices - DiVA Portal

IN DEGREE PROJECT INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY,SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS

, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN 2020

Exploring Choices: a case study of color-customised lipstick choices

VINCENT GIARDINA

KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGYSCHOOL OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE

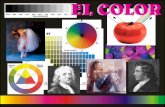

Abstract Product personalization is rising and with it, new choice architectures are required. It offers a new medium for identity expression, especially in the make-up case. Regarding the interactions involved, the research and industry explored the efficient choice. The current research dug into how to bring the development of individual taste and creativity through choice architectures, in case study of personalised lipsticks. Moreover, the makeup wearer is now savvy and creative, which calls for an alternative path. The subject has been explored through the lens of design probes which led to the prototyping of two experimental user interfaces. As a catalyst for personal expression, 3 considerations have been tested: the wearer as ambassador, the wearer as a creator, and the effect of the surprise. The exploration within the interaction brings users out of the boundaries of their style. Additionally, the dissociation of the color picking and vivid trying out, coupled with the effect of surprise and letting the participants mirroring themselves with other wearers, contributed to this effect.

Sammanfattning Produktanpassning ökar och med det krävs nya val-arkitekturer. Produktanpassning erbjuder ett nytt medium för identitetsuttryck, särskilt vid fall inom smink-industrin. När det gäller de interaktioner som ingår, undersökte forskningen och industrin det effektiva valet. Den nuvarande forskningen undersökte hur man kan få utvecklingen av individuell smak och kreativitet genom val-arkitekturer i fallstudien. Dessutom är smink-bäraren nu kunnig och kreativ, vilket kräver en alternativ väg. Ämnet har utforskats genom linsen av design-prober som ledde till två prototyper i form av experimentella användargränssnitt. Som katalysator för personligt uttryck har tre överväganden testats: smink-bäraren som ambassadör, smink-bäraren som skapare och effekten av överraskningen. Utforskningen inom interaktionen leder ut användare från de gränser de vanligtvis har i sin still. Dessutom bidrog dissociationen av färg-plockningen och livligt att prova till denna effekt, tillsammans med effekten av överraskning och att låta deltagarna spegla sig med andra smink-bärare.

Exploring Choices: a case study of color-customisedlipstick choices

Vincent [email protected]

KTH Royal Institute of TechnologyStockholm, Sweden

ABSTRACTProduct personalization is rising and with it, new choice ar-chitectures are required. It o�ers a new medium for identityexpression, especially in the make-up case. Regarding theinteractions involved, the research and industry explored thee�cient choice. The current research dug into how to bringthe development of individual taste and creativity throughchoice architectures, in the lipstick case study. Moreover, themakeup wearer is now savvy and creative, which calls foran alternative path. The subject has been explored throughthe lens of design probes which led to the prototyping oftwo experimental user interfaces. As a catalyst for personalexpression, 3 considerations have been tested: the weareras ambassador, the wearer as a creator, and the e�ect of thesurprise. The exploration within the interaction brings usersout of the boundaries of their style. Additionally, the dissoci-ation of the color picking and vivid trying out, coupled withthe e�ect of surprise and letting the participants mirroringthemselves with other wearers, contributed to this e�ect.

KEYWORDSdesign probes, explorative design, self-expression, make up

1 INTRODUCTIONEven though personalized services have existed for centuries,the new mediums o�ered by digital experience democratizedthem [1]. It allowed the consumer to take control of what isdelivered to them and let them explore the content and prod-uct in their way. The rise of personalization is transformingsoon into the norm. So much that studies mention that non-personalized experience could result in losing customers inthe future[8].

The cosmetics world follows this trend and releases moreand more personalized products through an interactive pro-cess [5], especially thanks to AI and AR. From the consumerperspective, we can see a way to reshape mass consumptioninto a bespoke experience. If turned into the right direction,the personalized product creates stronger emotions betweenconsumers and products [2], which can lead to consumingless but better.We can see here the opportunity to have a more human

experience. “We are switching from personalization by one,

the designer, to personalization by many, the consumers”[20]. It is the occasion to represent the consumer and a newway of identity expression. A personalized product can meana more sustainable economy as it is driven by demand. Addi-tionally, the consumer is ready to put energy into looking forthe product which de�nes themselves and de�nes the perfectmatch [23]. Thus, that also means a stronger attachment tothe purchase and less fast consumption.On the other side of the coin, the implementation of per-

sonalized experience can be subject to ethical issues. Therecommendation systems became the summit of ultra per-sonalization and come with all the ethical issues related tothe �lter bubble [11]. They have an advantage in terms ofshort term satisfaction and user experience. At the same time,they are also polarizer by design, giving a �ltered versionof the reality and then fostering intolerance to propositionsthat could challenge belief and habit created [11]. Appliedto the makeup use case, where the identity expression iskey, these technologies could format the choices, leadingto ethical issues in the same way as the one mentioned bySara Eriksson et al. [13]. In her essay [1], Rosen perfectlydescribes the risks related to the current application tech-nology which took the opposite direction of mass cultureleading to what she called “egocasting”. It means that thesenew services created a form of taste-jail around a user whichbecame the servant of their preferences. In this context, thesurprise and the discoverability of alternative styles are madedi�cult. Above all, it narrows the form of expression ratherthan enriching individual creativity. Thus, the question ofthe choice architecture (how choices are presented to theusers) is the heart of the question.In the same way as fashion [6], the makeup is a complex

language which particularly allows expression of identityand creativity. A more personal makeup can reshape the waywe express ourselves by opening a way to truly represen-tative styles. Compared to regular products, personalizedones need to have their own choice architecture [24], andpersonalized cosmetics needs to help the wearer to representthemselves. Here, the proposition is not to provide anotherrecommender system as it is necessary to avoid egocasting,nor to �nd the one and perfect match. This research aimsto provide a more human and natural way of building a

cosmetic product while promoting the plurality of identi-ties and self-empowerment by design. Keeping this in mind,the question of this master thesis became: What are ap-propriate alternative choice architectures to supportself-expression through make-up?This research is part of an internship in a young cos-

metic company developing a solution for building color-customized lipsticks. Thus, the context of the use of the re-sult of this research is constrained by the use case of onlinelipstick customization (desktop or mobile).

2 BACKGROUND2.1 Choice overloadWe can consider personalization as choosing within an in�-nite of options. Whereof the biggest challenge of personal-ized service is to propose something unique without over-whelming users. The paradox of choice, highlighted in thework of Schwartz [22], exposed the inherent issues of thechoice overload: through to regrets, escalation of expecta-tion, or self-blame. Also, more choices means more interest at�rst glance but lower engagement and worst decision quality[18]. A high number of options can at the same time have apositive e�ect in favor of individuality [9]. In this sense, ahigh number of options can be seen as powerful if providedin the right format. A meta-analysis on the choice overload[21] emphasized it by highlighting the choice overload thepreconditions: lack of familiarity, no prior preferences, noobvious dominant option.

2.2 Current choice architecturesThe research in the area of choice-making is rich especiallyin the domain of behavioral economics. Sustain and Thalerin 2003 [24] argue a framework for applying their vision ofdecision making: the libertarian paternalism. It proposes tokeep the freedom to choose while pushing to what is consid-ered, by the choice architect, as a good choice. This researchis a good frame for understanding human mechanism biasesin decision making. It is also a vision of the choice decisionwhich is representative of the current research state of theart providing a way to frame the choice: the research is fo-cused on preferential choices. Diverse approaches have beendeveloped to answer to speci�c use cases of choice overload[10]. In the behavioral economic research, we can �nd thatthe easiest decision is no decision; for the makeup customer,the act of taking a decision is probably what brings the mostvalue to it.

In the �eld of HCI, the subject has been explored [19]to adapt these tools to technologies but still in the samephilosophy. Research has been made in even more radicaland paternalist fashion [7] to guide decisions in the �eld isthrough persuasive technologies. It explored the solutions

for driving choice towards a speci�c goal using interaction,it is a form of persuasion that we can literally oppose choicesupport. Within these forms of guided choices, we can often�nd the recommender system.

More recent research, in the domain of HCI [14] provides anew frame oriented on non-preferential choices and support-ing the choices. That research compiles ideas from the exist-ing state of the art and de�nes a framework. It explores deci-sion making processes from the individual perspective: socialin�uence, attributes, experience, policies, consequences, ortrial and errors. While it de�nes how to design choice archi-tectures in order to support these choices. Here there is stillno consideration for the ethics of identity expression, andthe question of taste itself is not the main focus. It is abouttechnical guidelines for HCI.

In the literature, the choice is closely attached to the notionof identity. Either that the choices aim to be assimilated to acommunity or di�erentiate within it [12]. The make-up canbe social language in the sense that it is a way to expressourselves. Thus it should be considered as such and choosinglipstick becomes closely related to who we are or whom wewant to become. The cosmetics industry and fashion arefollowing each other quite closely. We can �nd some patternsevoked by Crane [6] in the current cosmetic industry. Themake-up in the same way as apparel can be considered as amedium where styles and fads can be distinguished. The redlipstick is �xed and socially anchored, almost a statement.While the bright orange lips never became a strong signi�er.

2.3 Industrial innovationThe custom lipsticks experience already exists under theformat of pop-up stores (The Bite Lip Lab and Etude ColorFactory). The process of de�ning color is made in collabo-ration with a mixologist which is present in order to sup-port the choice through discussion and followed an iterativecolor trial process augmented the use of di�erent textiles formatching with the lips.

The interactive experiencemade online lipstick vivid thanksto AR. We can �nd digital products that let wearers try outthousands of colors (Sephora Virtual Artist or MakeUp Plus,by Meitu), and more recently big marketplaces like Amazonand Facebook joined. The challenge is then quite close to theone of de�ning colors. They let customers go through cate-gories de�ned by hue in order to narrow down the options.This method is e�cient for whom knows precisely whatto wear or what to buy, but it doesn’t bring the wearer toexplore the choice as it is quickly narrowed. The quantity ofchoice displayed at once is such that going through di�erenthues and quick exploration is made di�cult.A more advanced and personal solution is L’Oréal Perso

which lets the lipstick wearer de�ne the color themselves athome with a physical device. In input the user preselects 3

color cartridges and then uses a mobile application with AR,to de�ne the perfect shades out of the colors. The productis here guiding the user, breaking the choice into a 2 stepprocess.The industry innovation re�ects the academic research,

it is focused on similar choice architectures and values thesame measure: the choice e�ciency.

2.4 Study justificationIn the current research landscape on choices, the way indi-viduality in�uences choice is not well represented. Rationaland preferential choices are well explored as well as how tomake a choice easier or to push towards a speci�c one. There-fore, the identity and the way we build taste are not directlycorrelated with the method used. In the �eld of HCI, the topicis also quite young as the �rst main research on support-ing choice [14] appeared lately. The personalization revolu-tion means dealing with unlimited choices, non-preferentialchoices, and direct feedback. It requires to rethink the choicearchitectures and develop alternative methods for exploringthem. On the other side of the interface, the consumer ismakeup-savvy and creative, while the services are still de-signed for guiding towards speci�c choices, or mainstreamchoices. Designing for users as experts, even as creators,needs an alternative path. Here, the question of identity andcreation is displayed in the middle of the project.

3 METHODThe challenge here is not to �nd the most e�cient patternfor in�nite choices. Solutions already exist, rather it is tounderstand the way we build taste and how to let thembe expressed through the process of decision making. Theproject adopted research through the design approach [26].It aims to generate new knowledge out of the realization of adesign. The output becomes itself the result of the research.Here, the approach has been led through inspiration-baseddesign research supported by prototype testing. This requiresthinking of alternative designs and search for more creativetechniques. The research is framed by the speci�c use case ofthe lipstick choices, the aim of understanding of the wearersand de�ning a choice architecture.The plan applied in the thesis following 3 steps: a �eld

study to ground the �eld, followed by design probes (develop-ment, testing, and analysis) for sympathizing and exploringideas, and �nally a prototype (design, coding, and testing)to apply the results. It has been necessary to go as far inthe research in order to apply a prototype that comes fromdesign probes.

3.1 Field studyThe �eld study aimed to get familiar with the universe of thecosmetics, prepare for further research, and �nd inspiration

through the data collected and the people encountered. Ittook the format of 4 contextual inquiries, 11 interviews ofshop advisors (so-called makeup artists), and a�cionados. Itwas supported by observations and in parallel of watchingvideos on the topic. The contextual inquiries were performedusing the think-aloud method, all 4 have been performed ina physical shop. The observations were performed under 2formats. The �rst one aimed to understand how make-upartists provide advices. The second type of observation wasfocused on observing the behavior of the customer in theshopwithout any interactionwith them. The interviewswereperformed both in cosmetic shops in the area of Stockholmfor the makeup artist with a duration of 15 min on averageand through a phone call for the a�cionados from 10 to 30min, all living either in Stockholm or Paris and aged from 23to 29 years old. All of the interviews have been made usingdirect note-taking. The process of the interview followed ahalf structured interview exploring: choice processes, choicein�uences, qualities of a great lipstick. The analysis of thisdata was following a thematic analysis and a clustering ofthe topic which emerge out of the data.

3.2 Design probesDesign probes [15] are the major part of this research. Theysoon became a relevant method for exploring new directions.The question here is complex and probably does not haveone single answer that can be summarized within a thesis.Approaching it in a purely engineering way would not leadto alternative or meaningful results. The design probes aim todesign for pleasure more than for utility [17]. They provideclues and pieces of life leading to inspire the early phasesof the design process. In the current case, the design probesaimed to: get inspirational results for building an alternativedesign, get very personal insight, and build a point of viewfor a way to express a personal value.

3.2.1 Participants. The screening process took 2 stepswherecreative pro�les were targeted. The screening has been madethrough the Instagram account of the hosting company. A�rst pre-selection has been made among the 480 follow-ers of the brand based on the sharing artistic practice onthe social network (make-up, painting, photo, poems). It re-sulted in 22 potential participants. A questionnaire has beensent to understand the participant better, and evaluate theircommitment. The �nal selection has been made accordingto self-consciousness, singular/artistic personality, diversitywithin the group (interest, lifestyle, skin-tone), and commit-ment/ability to perform the research. Finally, 5 participantswere selected, female aged from 21 to 26 years old.

3.2.2 Artefacts. In total, 5 di�erent design probes have beencrafted for each participant. They aimed to explore the vari-ous questions within a common frame (�gure 1). They have

been designed following the frame drawn by Wallace et al[25] putting design in the heart of the probes.

Figure 1: Exploratory topics

3.2.3 Analysis. Scienti�cally analyzing the probes is not toappropriate approach to it [4, 17], rather they were used asclues and perspectives on the life of the participants. The de-sign probes provided insights that are analyzed through dif-ferent perspectives to generate concepts. Along the process,di�erent methods have been developed to �ip the results andexplore from di�erent prisms. Four in-depth personas havebeen generated out of these results and a story out of it wasmade. These stories leaned on the frame of �gure 1. It builtempathy but also connected the dots within the diversity ofdata collected. It even became a way to communicate withthe participants. The analysis has been made through cluespicking, were probe by probe and participant by participant,the data released was analyzed and later clustered to discoverpatterns. In parallel to it, a process of idea generation alreadystarted, fed by the data of the probes.

3.3 Prototype3.3.1 Design and development. Several ideas have been ex-plored and also quickly implemented to be tested. The in-sights generated through the design probe method were usedfor both understanding the participants and generating ideas.It aimed to get impregnated by the design probes, and fromthat try to de�ne which lipstick would �t the participants asa way to think like them. Following 7 concepts of user in-terface were developed and evaluated depending on a set ofrequirements: engagement, fun, self-expression promotion,ownership creation, personality re�ection, ability to exper-iment (try out and leave), choice freedom, repeatability. Inparallel 3 choice architectures extracted from these conceptshave been evaluated on a participant. In the end, 2 proto-types ideas have been selected for the correlation establishedwith the design probes and the extent to which they madesense. From them, the prototypes were implemented usingHTML, CSS, and React, to be tested.

3.3.2 Testing. For testing, 8 lipstick wearers have been in-vited. They used to wear lipsticks color from red/purple tored/orange or nude colors and are aged from 24 to 34. They

live in the area of Paris, New York City, Stockholm, and areoriginated from di�erent countries: Spain, India, USA, Nepal,Ivory Coast, Madagascar, Algeria. All participants tested bothprototypes. The task asked to build the color for a lipstickthey would like to wear. The �rst step is explorative wherethey preselect up to 5 colors. For a second time, they try outthe lipstick and customize it, �nally name their new lipstick.The testing has been made fully remotely and has been

screen recorded for analysis. Participants were introducedto the task with an introductory note, and the host answeredpotential doubts. The participant performed the task fora �rst prototype (selected in random order). It was thenfollowed by a semi-structured interview. The latter prototypewas then tested and again a semi-structured interview wentafter. Finally, a self-assessment of the skin-tone made by theparticipant on the von luschan scale.

3.3.3 Analysis. The analysis has been focused on the semi-structured interview to explore the e�ect of both prototypes.It has been coupled with observations on the behavior ofthe participant within the UI and natural reactions. As sup-port, quantitative data has been extracted from controlledobservations and color choices.

3.4 EthicsEvery participant signed a consent form informing themabout the usage of the personal information they providedin the frame of the research and the usage of it, limited tothe context of the project. For privacy, the name of partici-pants has been replaced with Greek goddess names for thedesign probes, and Roman goddess names for the prototypetesting. Finally, the research aims to �nd an alternative wayto recommend choice to users to avoid �lter bubbling. It alsoaims to develop self-expression. The output of this researchcould be used to solve the ethical issues related to the formsof egocasting.

4 FIELD STUDY FINDINGSThe emergence of content online about cosmetics has madeconsumers very knowledgeable. That is the common com-ment coming from the makeup artists. The customer can beaware of various topics: composition, usage, or new releases.The internet communities have led to the spread of tricks likecombining multiple lipsticks at the same time to create a newcolor for instance. “Makeup related videos are the main topicthat I follow YouTube” according to an a�cionado. Indeedaccording to a study performed by Google [3], YouTube be-came the �rst source of exploration on the topic of makeup,in front of search engines. The make-up artists themselvesmentioned YouTube as a learning resource.The choices of lipsticks are driven by multiple parame-

ters. There is a big part of in�uences coming from personal

attributes: mood, skin-tone, makeup personality. The latter,as part of the decision, has been highlighted on the overallunderstanding of the participant where some were more con-servative and did not try new colors at all. One participanthighlighted wearing always to same lipstick of the samebrand and found an equivalent when her favorite productwas not produced anymore. For some other lipstick wearers,lipstick is an instrument of their makeup orchestra. Impor-tant to mention that the makeup personality did not alwaysdirectly re�ect the trait of the personality of the wearer; anextravagant speaker does not always wear extravagant lip-stick. External attributes play an important role too: trends,occasions, seasons. An interviewee mentioned even that thenew products of brands she follows are more interestingfor her. Also, the fashion legacy has been mentioned sev-eral times: “buy a lipstick I don’t have”, “according to mystyle” in other words, her wardrobe. The sources of in�u-ences mentioned by the interviewees are various as well:social networks (Instagram, YouTube), people in the street,friends. People close to them can play a role in the processof decision making: “I always send a picture of the lipstickto my sister or a friend before buying”. Another intervieweeexplained how she started wearing more colorful lipsticksas she discovered the blue lipstick on the lips of her friend.Interesting �ndings were observing that young customerscame to shop mostly in a group while older shoppers werelonelier in front of the display.

The reasons for wearing lipstick depends a lot on the indi-vidual. It can enhance a style or physical attribute: matchingwith a style, to “complete an out�t” or highlight a facialfeature. For others, it improves a mood (con�dence, feelingspecial) “It makes me feel more powerful” expressed an inter-viewee and another who mentioned that a good lipstick canbe a di�erentiator in a party. Finally, it can be worn for rep-resenting something: being festive, self-care. A participantexplains that she wears lipsticks only for unique occasions,looking “dressy”. At some points, the reason is less obviousand the habit becomes the reason for some wearer “I don’tfeel comfortable without lipstick” or even “never I could goout without wearing makeup”.The o�er in terms of diversity is huge through brand,

colors, composition. Even though, the main issue in the cur-rent system is related to the diversity of products in store:not having enough options (for darker skin-tone or missingproducts).

A consequent part of lipstick wearers know exactly whatto buy or will stick to the same cosmetic product according tomakeup artists. Another part as a more indecisive approachand come to be advised by the makeup artist or just try outnew things. For these, the shop advisors are following, ingeneral, the same manner. Asking about what the customerwants, tries to "get the glow” or “feel what the client wishes”,

then they propose according to it and the physical trait ofthe wearer, and �nally an iterative pick and try process fol-lows. There is a third common pro�le: the "explorer". Thiscustomer tries out products, experiments and rarely buysthe same product twice, the one coming using stores as ashowcase or exploration area. Makeup artists de�ned themas follows: “they come to shop to be inspired for later onordering online”.

5 DESIGN PROBESIn total, 5 design probes have been developed for each par-ticipant. They are designed to be easy to understand and toperform. An instruction notice was attached to each one ofthem for further information.

5.1 Design and Development ProcessThe �rst batch of 60 ideas was generated. They have beenthought around random topics and then clustered aroundmain topics: make-up perception, fashion jail (�delity toone single style), make-up �ction, self-perception, make-upvision, the concept of perception, habits, and routines. Fromthis batch 11 have been selected following the criteria ofrelevance, fun, and feasibility. A low �delity version of the 5probes has been crafted for 2 raw testings using the think-aloud technique to get how the participant interacts withthe probe and elicit the biggest issues. A second version hasbeen tested with a medium-�delity version of the probes totest if the participant understands well what is asked. Thethird version was released and tested with to �nal graphicdesign, packaging, and tone.

5.2 Artefacts5.2.1 Tabloid. The tabloid is a magazine designed for gos-siping. It is built from the images of a real British tabloidmagazine, Heat. It contains empty spaces dedicated to stylecritics. This design probe aims to learn more about how par-ticipants perceive and see others. In other words, they talkabout fashion codes and fashion stumbles they perceive.

Figure 2: Tabloid double page and cover

5.2.2 Inspiration box. The inspiration box is a mobile ap-plication that aims to explore the source of in�uences ofthe participants. It has been designed following the familiarwireframing of the photo camera applications. The numberof pictures has been limited to 26 for improving the qualityof the pictures. The pictures are automatically uploaded to

a server and are not visible anymore for the participants toavoid regrets. The choice to use a digital medium insteadof a physical disposable camera has been motivated by thebudget of the research and ecological reasons. The projecthas been open-sourced 1.

5.2.3 Provocative jigsaw puzzles. The provocative jigsawsare sets of puzzles to be completed and answered. Once done,the participant discovers a self-introspective question thathas to be answered by writing on it. This format aims tostimulate both creativity and con�dence by providing a feel-ing of accomplishment by giving the feeling of performing apiece of art. In order to stimulate imagination but also makethe jigsaw easier to complete, photos were picked for theFoam museum website and printed behind the question.

Figure 3: Photography of a completed jigsaw puzzle

5.2.4 Collage. The collage aims to let the participant dreamabout diverse out�ts from the wedding of their best friendto the interview for a dreamed job. On 4 canvases, the partic-ipant cut and paste out�t elements coming from a collectionof pieces of clothing crawled from online websites. The bigsize of the choice (650 items ordered by type of clothing)aimed to balance the bias related to the style crawling. The�rst phase of testing led to learn that some participants arenot comfortable with drawing out�ts and a digital versionwould reduce the engagement compared to a manual exer-cise.

5.2.5 Diary. The last exercise is at the boundaries of thespectrum of the design probes [4]. The diary is a booklet ofsmall exercises. It aims to gather pieces of information aboutthe participant values to have a baseline in which exploresthe life of testers. It contains various exercises such as wishlist letter for Santa Claus, map of the perfect day, or whatmakes your mood today. Every booklet is personalized beingprinted with the picture and name of the participant on thecover (�gure 4) and graphic design has been done with ahandmade style.

5.3 CommunicationThe strength of the design probes remains in the relationshipthe research can create with the participants [16]: giving isreceiving. Given the size of the sample, it has been possibleand necessary to create it. The tone has been made friendly1https://github.com/giardiv/disposable-camera

and emoji-enriched in the direct messages sent on Insta-gram. An individual call aimed to create the �rst contact,know them better, and softly break down the wall of thescreen. The visual tone of the graphic design used a colorpalette invoking sweetness. Drawings and paintings madethe probes less formal. The font used is Formula (foundryPangram) chosen for its versatility and character, and Promptwhich reminds the familiar style of the hosting company.

Figure 4: Cover ofa diary

In the instruction notices, particu-lar attention has beenmade tomaketheir reading enjoyable and engag-ing: references to pop culture, jokes,and fun facts. The design probeswere not called exercises but games.Each pack included a personal note.The diary and instructions men-tioned the participant’s name. A�ower was added on top of the box,as a way to tell the participant howwe care about them.

6 DESIGN PROBE FINDINGSOverall participants have completed the probes except forAphrodite who did only the Jigsaw due to a misunderstand-ing. Thus, most of the following results will represent theresults of 4 participants. Additionally, Athena and Demetrafaced issues with the tabloid because of its form which didnot represent their values.Styles are unique, in�uenced and plural. There are clear

trends both in their own style (Athena has a big crush on jeanfabric) and between participants (tendency to favor oversizedclothes). Their style seems to be de�ned between the sum ofthe trends they faced and their personal interpretation. Eventhough the styles are appropriated by each one, they are plu-ral for all. Interestingly, they de�ned their style through anantithesis: Athena de�ned her dream style “adventurous andcalm”, “classic but still kind of casual” for Hera, or Demetrade�ning her style “simple yet fashionable”, “business casual”for Artemis. Unique occasion pushed them to the boundariesof their style.

The story matters. The fashion codes are mixing betweeneach other so much that the words of the fashion languageevolved into having a more super�cial meaning. “Punk isnot dead” commented Athena next to her jean jacket ona black out�t, even though her values, she would wear agolden feather clip on another out�t. The choices are thenmade on the image more than the deep tenor behind it. Allparticipants have evoked a story behind clothing but alwayscame from the super�cial aspects of the object or the brandbehind it.A common frame exists. Even the most tolerant partici-

pant expressed some no-go styles. It can come from a form

Figure 5: Artemis’s collages

of fashion legacy or simply the code we integrated. In theprobes, there is a form of fashion determinism where thebackground of the wearer de�nes their style. The wearerseems relatively conscious of their style even having fashionstrategies that are the rules that shape a taste. The dreamedstyle is not the current style: everyone talks about having adi�erent style.The incarnation of the style is key to develop new ones.

The �rst fashion crush seems to be very in�uential on thestyle of every participant. On the question about the storybehind your �rst fashion crush, Artemis evoked a YouTubechannel of a Korean lifestyle artist. Their style is quite similartoday. When Athena argues about Michael Jackson’s style, itreminds her style again. In the case Aphrodite: the ’perfect-ish’ style is related to her Barbie crush. On this question,no one gave a clothing item as an answer. The style has tobe incarnated by someone or a �ctional character that theycan mirror to and the brands understood it. The approachof current brands for spreading products is mainly madethrough this system of ambassador, so-called égérie2. Wecan �nd these icons in advertisements, product placing, oreven more recently on Instagram. The current inspirationfor having a new style often comes from someone we knowaround us. This inspiration is the mirror of a future selfwhere the wearer appropriates the style by adapting it toherself and then be on her turn the icon of a new style, herown.Everyone is an égérie. The �aws are accepted and they

can even be a strength. Aphrodite is representative of it as-suming her scar and even using it a di�erentiator. Everyparticipants mentioned that �aws should be accepted. Deme-tra mentioned that she would like to look like Marzia (ItalianYouTuber) and her videos are about a casual life that couldbe hers. The favorite show of Artemis is not about peoplehaving fancy life neither, but again literally a life that shecould live and similar to her dreams. The new égérie is nota star, but a neighbor. The rise of natural make-up or nude,the success of the strategy of Glossier promoting the people,are the symbols of this more human and relatable world.The most �agrant evidence that everyone is an égérie is theInstagram pro�le which is so often populated of pictures ofits owner.

2ambassador of an idea, muse and advisor

7 PROTOTYPEThe output of the design probes: personas and insights, havebeen a precious input for building the prototypes. Theirconnection is articulated in the section 7.2.

7.1 ImplementationThe implementation of the ideas took the form of 2 pro-totypes following 2 di�erent explorative approaches. Theformer lets the wearer explore the invisible, going through ahidden map of colors. It took the form of a blank page openedon a desktop where the cursor is the probe and a colored diskin center is the color indicator. Here, the spectrum of coloris fully accessible and let the tester go as deep as needed inthe shades.

Figure 6: Mobile Screenshots: exploration, de�nition, nam-ing

The latter lets the wearer explore their physical environ-ment, getting inspired by what is reachable from the lens oftheir phone camera. It took the form of a mobile web pagewhere the probe is the camera of the device. In a way, it alsomakes the invisible visible by pushing the user to �nd thehidden colors, literally play with the shades of objects, andpotentially highlight the style legacy of the wearer. At thesame time, we can imagine that the color spectrum becameconstraints to one of the environments.

Figure 7: Mobile Screenshots: exploration, de�nition, nam-ing

Through the process of exploration, both prototypes letthe testers discover pictures of people wearing lipsticks in theclose range of hue or brightness (exploration). The wearerpicks a color and then customizes the color for their tonewhile visualizing the color on a picture of them (de�nition).Finally, the wearer takes to publish the picture with the colorand becomes in their turn an égérie of their new lipstick

(naming). For more details and vivid experience, videos of 2prototype testing are available for desktop 3 and mobile 4.

7.2 Vision behind implementationThe prototypes aim to di�erentiate from the existing choicearchitectures in the way they promote exploration of newcolors. To support the exploration andmatch with the wearerpro�les, the 3 following catalysts (extracted from the designprobe insights) have been included in the prototype.

Figure 8: Environ-ment explorer

7.2.1 Wearer as an égérie. The de-sign probes highlighted how wear-ers are inspired and inspire. Lead-ing choices through inspiration is away to reproduce the existing pro-cess of building a crush while let-ting trends emerge within the com-munity of wearer. The wearer candirectly mirror themselves in thestyle of another wearer. The diver-sity of style cannot be representedat once but here clusters of style canbe found and also brings value fromtheir intersection. The styles cometo the users by exploring a virtualor physical environment. Instead offollowing the same color, the prototype lets the customerbuild their own taste and explore the boundaries of theirstyle. Here, the current style of the comfort zone and thewillingness to explore can merge using the bene�ts of self-mirroring.

7.2.2 Wearer as a creator. The wearer is now makeup savvyand creates their own styles. The act of building aims tocreate the appropriation of the lipstick that could even benamed like its creator. As the color becomes the gift from theauthor, the customer deserves to be identi�ed by the brand.A�xing a name on the color is a way to create even strongerappropriation of the color. Without naming it, the color doesnot exist. When the customer �nds a color associated withsomeone, a name is associated with it mirroring again thepossibility to leave a trace of themselves there. The color canbe directly adopted but also as long as the color is updated,it becomes custom and then the property of its author. Also,as a user creator, experimentation is necessary. The userinterface aimed to encourage trials through the explorationof what they don’t know: the hidden map or the hiddenhues in an environment. That is also why the most commoncolors of lipstick (from orange to purple by red) have beendisplayed on the borders of the map. Furthermore, the design

3https://youtu.be/St9jzf5Jkoc4https://youtu.be/PPzi3ZrvfoI

probes insights highlighted the role of models in the creationprocess. The pictures displayed aimed to be an inspirationalgallery where the wearer becomes a muse for the currentcreative builder.

Figure 9: Screen-shot of thecustomization

7.2.3 Surprise e�ect. In order tobreak the taste-jail of the wearer,the prototype aimed to trigger thefeeling of surprise towards alterna-tive colors. The steps of picking col-ors and visualizing the lipstick onthe lips of the user have been vol-untarily separated. The wearer canonly try the lipstick after pickingone or few colors and not as a jux-taposition of the color. It aimed tobreak the association of color forlipstick and foster the selection ofwhat a user considers as a nice color.We can be in love with color by it-self but under the form of a product, the color is not anymorean interest even before testing it. Fashion codes and legacyare so deeply anchored in our selection process that we canbecome blind to other styles that could actually please us.That is where the concept of thoughtful gift become valuable:it forces the receiver to perceive the product di�erently andto give it a chance. Here the point of view matters.

8 PROTOTYPE FINDINGS8.1 Overall experienceBoth prototypes have been adopted in a di�erent way in the�rst part. During the �rst phase when the participant facedthe hidden map a lot of confusion was perceived and evenexpressed orally, but once they played around with the cur-sor, the system got quickly understood and then a positiveemotion was expressed. During this moment of realization,participants mentioned feeling "curious", "having fun", orhaving a "playful" experience. Then, a new phase of explo-ration started but with the rules in mind where participantsdid a lot of back and forth exploration of color areas, up to 22for Vesta. Almost all of them pre-selected the maximum ofcolors: 5. The adoption was much faster for the environmentexplorer as it is a pretty straight forward UI. It was even con-sidered as too "brutal" to be directly introduced to the camera.Here participants had 2 reactions: either a strong interestmoved around to get an interesting color or stayed on theirchair and dealt with what was around them. This momentof the test was considered as frustrating for 3 participantswho did not �nd the color expected, exciting for 3, and the 2others did not express a particular expression except for fun.The rest of the experiment was pretty similar in terms of UIand also in the experience felt. When the picture of them

was released wearing the lipstick, the participants expressedsurprise. It followed with a moment of focus where the �nalcolor was de�ned and here again the color was experimenteda lot by every participant.

8.2 Color hunting

Figure 10: Final color selected by the participant

According to �gure 10, only 2 participants stayed in theircomfort zone for picking a lipstick: Dianna and Flora. Con-sidering a signi�cant shift out of the hue comfort zone as adi�erence of hue over 8 percent in the HSL scale, 7 out ofthe 16 color pickings explored a new hue. Within these 7outliers of the comfort spectrum of the participant, 5 havebeen picked through the environment exploration. In prac-tice, participants explored very diverse areas of the hiddenmap and spent time on all of them. Even if they picked whatthey considered a classic color, almost all of them tried non-conventional colors for them. In the sets of preselected colors,the hue diversity is higher than the one represented in the�nal results �gure 10. On average, on 4.7 colors picked, 1.94were out of the familiar color spectrum. An interesting re-sult was the harmony of the preselected colors where Florapicked only pale colors, Venus only dark. Additionally, theharmony was accentuated by an environment which hasalready a de�ned color palette like the garden in which Vestawas. The behavior of participants has led to interesting re-sults as well. Vesta was searching for a kind of orange on aplant pot and while looking for color around her she got theidea of trying out a color white as the wall behind her. Dianawanted to try out the red from the Nepal �ag, the countryshe is from. For a few others, they tried a color out of theirclothes for trying to have a match.

8.3 Égérie inspirationThe participants, overall, felt proud of their choice whenasked and agreed for sharing a picture of them as égérie, butthere was no real feeling of becoming an ambassador of thebrand for them even though the story was built around. They

did not feel being the creator of the color and sharing thepicture with the public meant to be a hidden dot in the end.Still, the pictures of other égérie had a direct impact on thedecision. Seeing the picture of someone wearing the lipsticksometimes discouraged them to try it but also some othertime it was a direct mirroring. The skin tone was an impor-tant element of comparison here where it allowed them tosee the e�ect of color. No direct crush on color has been no-ticed but participants discovered new tones and attract theirinterest according to the comment expressed while exploringpro�les. Finally, the participants used the inspiration picturesas a reference in di�erent ways: Fortuna and Minerva didnot pay attention to the inspiration for taking a decisionand their preselected colors are relatively classical. They ex-plained having something precise of in mind. Flora and Vestachecked many more pictures (12 and 20 respectively) whileboth of them were in an explorative mood.

8.4 Surprise e�ectObservations had led to notice surprise in both oral languageand facial expression. The surprise appeared earlier than ex-pected when the participant discovered a color of the lipsof someone in the inspiration pictures, 6 of the participantscommented with surprise at least one picture. Flora espe-cially liked it as "you don’t know what will appear". Thesurprise driven by the second part of the prototype was notas strong as expected but realized interesting results. For the6 participants who expressed surprise orally, it was due tosee themselves with a new lipstick directly, but none of themgot a direct crush. Though, the visualization of it made itvivid and made the choice more e�cient.

9 DISCUSSIONThe design probes lead to know the participant more gen-uinely, and it was noticeable especially through the contrastof personality between the direct interaction with them andwho they are through the result of their probes. Their imple-mentation gave a very personal perspective which also wasa limit. Still, the prototypes bene�t from this input whichdirected them towards an experimental form. The idea be-hind this method was motivated by the wish of designingfor the humans met through the probes and not for a groupof users. It was a necessary approach to think alternativelyto the recommendation system which frames user’s free-dom. It would have been interesting to test it on the sameparticipants but trying with di�erent ones made the out-put more relevant to be exported and applied to anothercase. Finally, the model of the exploratory topics (�gure 1)helped to create a story around the important amount ofdata coming from the probes. Looking backward, it was anecessary framework to be in the skin of the participants.Still, it is important to emphasize the di�erences of context

between the experiment and buying a lipstick in store. Achoice of lipstick is not limited to the single attribute of itscolor but a set of others like the texture, the lip coverage, orthe brand identity. Considering that, this experiment spot-lighted mostly the alternative choices but did not prove ade�nitive choice. About the participants, the experiment hasbeen led on groups of women mostly under 27 years old. Theresearch re�ects the fact that it is a moment of life wherethe style is mature and open. Even though the initial planaimed to reach the “creative” wearer, the result has proventhat every wearer experiment to an extent. The explorativechoice architecture disrupted the way wearer choose colorsand thus proposed an alternative that takes distance withthe egocasting as it led to the discoverability of new colors.Where the interface mentioned by Rosen [1] is letting theuser follow a preference, the current ones pushed to the ex-treme opposite in some cases which could raise the questionof the legitimacy of the choice if the choice would have beenfor a purchased lipstick. Still, choice satisfaction has beenassessed as good. We can support the diversity of choicebecause of the format under which color choices have beenshown. It rede�ned the scale as the most popular colors dis-played on the border or even the color of the environmentwhich has a more reasonable amount of red. According toJuno, in the shop, there are so many classic shades of red thatdi�erent colors look extraordinary. But also, the dissociationbetween picking color and trying it out on a picture was inthe end not only the source of a surprise but also exploration.The exploratory phase led the wearer to pick the color thatthey consider nice without always directly associating it toa future lipstick. Once on the lips, it was the occasion to trysomething new. The positive results in terms of diversity ofhue proved that they considered wearing this new color. Fi-nally, switching towards considering the user as a creator bygiving full freedom was appreciated heterogeneously, whichis a limit regarding the experience. The choice paternalismevoked by Thaler [27], meaning that the choice architecthas to lead towards a good choice, is probably avoidable buttrying to let the user �nd what represents them is not alwaysthe most enjoyable experience.

9.1 LimitationsThe color spectrum able to be done on the screenwas limitingthe choices for participants who wanted to play with moreparameters than the hue and luminance. Additionally, thecolor blend on the lips was not as realist as wished. It usedsimple transparency at 45% which is the equivalent of amedium coverage lipstick. Not being able to deliver a lipstickas a reward and materialization of their choice, made theexperiment less vivid. It would have led to more concreteand realist choices, on top of more engagement.

9.2 Future workThe current work explores the makeup world but it espe-cially focused the lipsticks towards the end of it for testingconcretely. Applying the current approach to other makeupproducts could worth the interest and contrast with the cur-rent results. Even though the appropriation by the wearerhas led to the use of lipstick as a creative medium, it staysmostly limited to the color and its attributes. A few partici-pants mentioned that they would like to try it for eye shadowor for eyeliner designs. The AR comes with new possibilities,the new directions to be explored worth rethinking the ser-vices. Another interesting direction that this project couldhave is its application out of the frame of the study case.Respecting the diversity of application and their constraints,the current work could evolve towards a frame that supportsthe explorative choice architectures, for personalization orchoice which requires personal taste expression. Finally, theframe of the 4 exploratory topics was interesting supportand was applied as a versatile tool during the �rst part of thethesis. The test and development of this tool when applied toother cases can lead to an interesting method to emphasizewith the participant of design probes.

10 CONCLUSIONThis thesis aimed to explore alternatives to the current solu-tion in the choice architecture landscape. Academic researchand industrial innovation focused on e�ciency while herethe lens of the personal representation has been explored.The gap in the research landscape leads to explore alter-natives. The design probes motivated the proposition thatexplorative user interfaces can be a way to express and ex-plore personality. To support this exploration, 3 catalystshave been applied: incarnate lipsticks through the picture ofa wearer, consider the user as a creator by letting them buildthe color and name it, invoke surprise by dissociating colorpicking to the vivid experience of trying it out. On top of that,2 di�erent explorative approaches have been implemented.The participants explored new directions which is also justi-�ed by the dissociation of picking and trying, coupled withthe e�ect of surprise.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSFirst of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. MadelineBalaam, for her generosity during my thesis. She providedthe support which guided me through the project and con-tributed to building my vision of interaction design towardsthe right direction. Also, I would like to thank every singleparticipant for their engagement. As well, Yanitza Harris forher logistic help during the implementation. Finally, thankmy hosting company team for the time they dedicated to myproject.

REFERENCES[1] [n. d.]. The Age of Egocasting. https://www.thenewatlantis.com/

publications/the-age-of-egocasting[2] [n. d.]. Emotional bonding with personalised products: Journal of

Engineering Design: Vol 20, No 5. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09544820802698550

[3] [n. d.]. How beauty brands can reach fans with YouTube. https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/advertising-channels/video/beauty-videos-on-youtube/

[4] [n. d.]. How HCI interprets the probes | Proceedings of the SIGCHIConference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1240624.1240789

[5] [n. d.]. How Technology Will Change Beauty After Covid-19 | BritishVogue. https://www.vogue.co.uk/beauty/article/tech-changing-beauty-forever

[6] [n. d.]. Identities Through Fashion: A Multidisciplinary Approach:Ana Marta González: Berg Publishers. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/identities-through-fashion-9780857850584/

[7] [n. d.]. Persuasive technology: using computers to change what wethink and do: Ubiquity: Vol 2002, No December. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/764008.763957

[8] 2015. The Deloitte Consumer Review: Made-to-order: The rise of masspersonalisation.

[9] Chris Anderson. [n. d.]. Long Tail : Why the Future of Business IsSelling Less of More. ([n. d.]), 282.

[10] Tibor Besedeš and Sudipta Sarangi. [n. d.]. Reducing Choice Overloadwithout Reducing Choices. ([n. d.]), 31.

[11] Engin Bozdag and Jeroen van den Hoven. 2015. Breaking the �lterbubble: democracy and design. Ethics and Information Technology 17,4 (Dec. 2015), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-015-9380-y

[12] Cindy Chan, Jonah Berger, and Leaf Van Boven. 2012. Identi�able butNot Identical: Combining Social Identity and Uniqueness Motives inChoice. Journal of Consumer Research 39, 3 (2012), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1086/664804

[13] Sara Eriksson, Kristina Höök, Richard Shusterman, Dag Svanes, CarlUnander-Scharin, and Åsa Unander-Scharin. 2020. Ethics inMovement:Shaping and Being Shaped in Human-Drone Interaction. In Proceedingsof the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems(CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, Honolulu, HI, USA,1–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376678

[14] Cena Federica, Gabrielli Silvia, Gena Cristina, Jameson Anthony, Rei-necke Katharina, Berendt Bettina, and Vernero Fabiana. 2014. ChoiceArchitecture for Human-Computer Interaction.

[15] Bill Gaver. 2020. The Presence Project, Second Edition | The MIT Press.https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/presence-project-second-edition

[16] Bill Gaver, Tony Dunne, and Elena Pacenti. 1999. Design: Culturalprobes. Interactions 6, 1 (Jan. 1999), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/291224.291235

[17] William W. Gaver, Andrew Boucher, Sarah Pennington, and BrendanWalker. 2004. Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty. interactions11, 5 (Sept. 2004), 53. https://doi.org/10.1145/1015530.1015555

[18] Sheena S. Iyengar andMark R. Lepper. 2000. When choice is demotivat-ing: Can one desire toomuch of a good thing? Journal of Personality andSocial Psychology 79, 6 (2000), 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.995

[19] Eric J. Johnson, Suzanne B. Shu, Benedict G. C. Dellaert, Craig Fox,Daniel G. Goldstein, Gerald Häubl, Richard P. Larrick, John W. Payne,Ellen Peters, David Schkade, Brian Wansink, and Elke U. Weber. 2012.Beyond nudges: Tools of a choice architecture. Marketing Letters 23, 2(June 2012), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-012-9186-1

[20] Iryna Kuksa, Tom Fisher, and Tom Fisher. 2017. Design for Personalisa-tion. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315576633

[21] Benjamin Scheibehenne, Rainer Greifeneder, and Peter M. Todd. 2010.Can There Ever Be Too Many Options? A Meta-Analytic Review ofChoice Overload. Journal of Consumer Research 37, 3 (Oct. 2010),409–425. https://doi.org/10.1086/651235

[22] Barry Schwartz. [n. d.]. The Paradox of Choice. ([n. d.]), 282.[23] David Searls. 2012. The Intention Economy.[24] Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions

About Health, Wealth and Happiness.[25] Jayne Wallace, John McCarthy, Peter C. Wright, and Patrick Olivier.

2013. Making design probes work. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Con-ference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’13. ACM Press,Paris, France, 3441. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466473

[26] John Zimmerman, Jodi Forlizzi, and Shelley Evenson. 2007. Researchthrough design as a method for interaction design research in HCI. InProceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in ComputingSystems - CHI ’07. ACM Press, San Jose, California, USA, 493–502.https://doi.org/10.1145/1240624.1240704