A Case for Two Vorlagen Behind the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab)

Transcript of A Case for Two Vorlagen Behind the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab)

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents ..................................................................................... v Abbreviations .......................................................................................... vii Introduction .............................................................................................. 1

Shani Tzoref and Ian Young

Eulogy for Alan Crown ........................................................................... 9 David Freedman

Part 1. Qumran Scholarship: Now and Then .................................... 15 Qumran Communities— Past and Present ............................... 17

Shani Tzoref

Part 2. Textual Transmission of the Hebrew Bible........................... 57 The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Dead Sea Scrolls. The

Proximity of the Pre-Samaritan Qumran Scrolls to the SP .... 59 Emanuel Tov

“Loose” Language in 1QIsaa ....................................................... 89 Ian Young

The Contrast Between the Qumran and Masada Biblical Scrolls in the Light of New Data. ............................................ 113 Ian Young

Part 3. Reception of Scripture in the Dead Sea Scrolls .................. 121 A Case for Two Vorlagen Behind the Habakkuk

Commentary (1QpHab) ............................................................. 123 Stephen Llewelyn, Stephanie Ng, Gareth Wearne and

Alexandra Wrathall

“Holy Ones” and “(Holy) People” in Daniel and 1QM ....... 151 Anne Gardner

What has Qohelet to do with Qumran? .................................. 185 Martin A. Shields

4QTestimonia (4Q175) and the Epistle of Jude..................... 203 John A. Davies

vi KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

Plant Symbolism and the Dreams of Noah and Abram in the Genesis Apocryphon ............................................................ 217 Marianne Dacy

Part 4. Community and the Dead Sea Scrolls .................................. 233 What Did the “Teacher” Know?: Owls and Roosters in

the Qumran Barnyard ................................................................. 235 Albert I. Baumgarten

Exclusion and Ethics: Contrasting Covenant Communities in 1QS 5:1–7:25 and 1 Cor 5:1–6:11 ........................................ 259 Brad Bitner

Eschatology and Sexuality in the So-Called Sectarian Documents from Qumran ......................................................... 303 William Loader

Part 5. The Temple and the Dead Sea Scrolls ................................. 317 A Temple Built of Words: Exploring Concepts of the Divine in the Damascus Document ......................................... 319

Dionysia A. van Beek

4Q174 and the Epistle to the Hebrews.................................... 333 Philip Church

The Temple Scroll: “The Day of Blessing” or “The Day of Creation”? Insights on Shekinah and Sabbath ......................... 361

Antoinette Collins

List of Contributors ............................................................................. 375

123

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN BEHIND THE HABAKKUK

COMMENTARY (1QPHAB)

Stephen Llewelyn, Stephanie Ng, Gareth Wearne and Alexandra Wrathall

1. INTRODUCTION

Moshe Bernstein1 asks the provocative question whether our understanding of the Qumran documents would be different if they had been discovered in a different order. As he observes:

Too much weight is placed on 1QpHab as a model, on the

existence of two kinds of pesharim (i.e., “continuous” and

“thematic”), and on the need for pesharim to behave rather

monolithically.2

The problem in sequencing of evidence is not one of which the historian is unaware; for the order in which evidence is adduced defines the questions we ask of the next piece of evidence; a hypothesis constructed on available evidence requires testing in light of emerging evidence. Bernstein, of course, directs his question to the use of introductory formulae in the pesharim and

1 Moshe J. Bernstein, “The Introductory Formulas for Citations and

Re-citations of Biblical Verses in the Qumran Pesharim: Observations on

a Pesher Technique,” DSD 1 (1994): 30–33. Unless otherwise indicated,

all translations of ancient texts are our own. 2 Bernstein, “The Introductory Formulas,” 63.

124 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

regrets the skewing of analysis by the earlier publication of 1QpHab. The present analysis will avoid the criticism by consciously focusing only on the scribe of 1QpHab without postulating a more general scribal practice behind the pesharim as a whole.

2. DESCRIPTION

The Commentary on Habakkuk possesses unique textual and physical features. Spanning 13 columns, the text is written on ruled parchment and suffers deterioration along the base of the entire scroll and across the first two columns. Written in distinct Herodian script, the text is legible, interspaced with vacats, 11 crosses (we discount the mark at 1QpHab 9:16 as too uncertain) and a single ’aleph located in col. 2. The same scribe has written the first twelve columns of 1QpHab and 11QTb (11Q20).3 A change in scribal hand occurs in 1QpHab 12:13. It is at this point that textual features such as vacats and crosses cease.

Comprised of two separate pieces of parchment, the two halves of the scroll are linked at the borders of cols. 7 and 8. The pieces of parchment have right and left margins and lines are ruled. In the second parchment the lines are ruled to the top of the page indicating that it was cut to be joined to the first piece. The left margin appears to operate only as a guide, as sentences occasionally continue a letter or two into the margin. The end of the scroll is indicated at col. 13, which finishes half way down the column, leaving a ruled space at the base. Furthermore, there is surviving parchment attached to the end of the scroll indicating a blank col. 14.

Upon initial observation, it is not immediately clear whether both parchment pieces consisted of 17 written lines. Extensive deterioration across the base of the manuscript makes identifying

3 So Florentino García Martínez, Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, and Adam S.

van der Woude, Qumran Cave 11.II: (11Q2–18, 11Q20–31) (DJD 23;

Oxford: Clarendon, 1997), 364, and Emanuel Tov, Scribal Practices and

Approaches Reflected in the Texts Found in the Judean Desert (Leiden: Brill,

2004), 23.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 125

the exact number of ruled lines difficult. As well, a comparison between columns 7 and 8 shows that the lines do not exactly match up due to the difference in width of the first lines in each parchment. Yet calculation of the space required for the lemma at the base of col. 7 (col. 8 begins with פשרו) indicates that both pieces of parchment were written on 17 lines. Bilhah Nitzan4 makes a similar calculation based on the space needed at the end of col. 12 to contain two verses of Habakkuk. Additionally, a distinct lack of cramping in the handwriting as the scribe moves from col. 1 through 7 further suggests that the scribe was not concerned to try to fit the work onto the first piece of parchment.

3. PAST INTERPRETATIONS

Before starting there are a number of considerations that will bear on our discussion. First, it is important to distinguish between the scribal practices of the author, the copying scribe(s) and the reader(s). Vacats and the use of paleo-Hebrew script for the tetragrammaton are clearly scribal, though it is not always clear whether these derive from the author or his copyist(s). On the other hand, the use of the cross and the paragraphing siglum may derive from the scribe or the reader.5 Second, 1QpHab is only extant in one copy, but it does not follow from this that it is an autograph. Indeed, other pesharim are extant in multiple copies or versions (i.e., five of Isaiah and perhaps two of Hosea, with 4QpIsaa and 4QpIsac also overlapping in passages from chapter 10) so it is not out of the question that multiple versions of the Habakkuk pesher were in circulation. Indications that 1QpHab is a copy are: (a) the changed hand at 1QpHab 12:13; (b) the alleged mistaken copying of a scribal sign, e.g., ’aleph for cross (1QpHab 2:5);6 and (c) the instance of haplography (1QpHab 7:1).7 Third,

4 Bilhah Nitzan, Pesher Habakkuk A Scroll From the Wilderness of Judaea

(1QpHab) (Hebrew; Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1986), 1–2. 5 Tov, Scribal Practices, 179, argues that most of the scribal marks are

probably inserted not by the writer (original scribe) but either by

subsequent scribes or readers. 6 Tov, Scribal Practices, 28, 209–10 and 258. The difficulty with this

hypothesis with regard to the ’aleph is that (a) the scribe did not recognize

126 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

scribal practices may not be used consistently, either by intent or mistake, and even if used consistently, the scribal policy may not appear obvious or logical to us. That said, it is reasonable to assume the greatest degree of scribal consistency in texts copied by the same individual. In other words, one expects some consistency in scribal choices between 1QpHab and 11QTb (11Q20) as both have the same scribe.

3.1. The Crosses

Eleven or twelve crosses appear in the text of 1QpHab—the number depends on how one reads the fragmentary end of 1QpHab 9:16; eight or nine are in pesher sections and three in lines with a scriptural citation or lemma (1QpHab 3:14; 6:12; 9:13). Their interpretation is problematic.8 Emanuel Tov observes of the

the mark in his Vorlage, though elsewhere he correctly uses the practice;

and (b) it assumes that at this point the Vorlage had the same line division,

a feature that is problematic given that column dimensions varied and

were not standardised. See Tov, Scribal Practices, 29. 7 H. Gregory Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses: Pesher Manuscripts and

their Significance for Reading Practices at Qumran,” DSD 7 (2000): 40,

and Gregory L. Doudna, 4Q Pesher Nahum: A Critical Edition (JSPSup 35;

Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 43–44, adduce a number of

factors to suggest that the scribes were copying and not composing and

with this we would agree. 8 It is interesting to note the similarity between the “crosses” of

1QpHab and the shape of the paleo-Hebrew tav. In the Hebrew

Scriptures the paleo-Hebrew tav is used in several contexts as an

identifying mark (Job 31:35; Ezek 9:4, 6, note also the occurrence of the

verb תוה in the piel in 1 Sam 21:14). This raises the interesting possibility

that the crosses have some special semiotic significance relating to the

archaic tav. However, as this significance is necessarily derived either from

the cross’ relationship to something within the text or external to it, there

is no a priori way to determine its meaning. That being said, one intriguing

possibility does present itself in relation to the singular use of the ’aleph in

2:5. That is, it may be that the scribe initially intended to mark his text

with an ’aleph, but later changed his method in favor of the paleo-Hebrew

tav in order to alleviate any potential confusion, i.e., with the marker being

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 127

marginal scribal marks: “These signs probably direct attention to certain details in the text or to certain pericopes, but they may also refer to the reading by the Qumran covenanters of certain passages, especially in the case of 1QIsaa.”9 In other words, the marks might draw the attention of the reader to issues and/or to passages of sectarian interest. The cross is one such sign that can “draw attention to certain words, lines, sections, or issues to the left of the sign.”10 But Tov does not extend this interpretation to the crosses in 1QpHab11 which he views as line fillers indicating that “the space at the end of the line was not to be taken as a section marker.”12 He gives the same explanation for the two crosses on the left hand margin of 11QTb (11Q20) and perhaps 4Q252 I 4.13 The reason for differentiating the crosses in 1QpHab

accidentally read as part of the text. Nonetheless, until such time as

further information comes to light this suggestion must remain

speculative. See further Charlotte Hempel, “Sources and Redaction in the

Dead Sea Scrolls: The Growth of Ancient Texts,” in Rediscovering the Dead

Sea Scrolls. An Assessment of Old and New Approaches and Methods (ed. Maxine

L. Grossman; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010), 167–168, for the use of

paleo-Hebrew letters in the margins of 1QS 5:1 (waw), 8:1 (zayin and

unknown character) and 9:3 (zayin and samekh). Here also their

significance remains something of a mystery, though it is suggested by

Hempel that they may indicate the juncture of texts (5:1) or perhaps an

important passage (8:1 and 9:3). In anticipation of our own hypothesis

adduced below we merely note the occurrences of these scribal signs at

the top or near the top of three columns 9 Tov, Scribal Practices, 206, 265–66. Besides 1QIsaa Tov argues that the

cross designates matters of special interest in documents following the

Qumran scribal practice in 4QCatena A (4Q177), and 4QInstrc (4Q417)

as well. 10 Tov, Scribal Practices, 208. 11 1QpHab shares the use of the cross as a line filler with two other

mss, 4QCommGen A (4Q252) and 11QTb (11Q20). The latter ms is said

to be by the hand of the same scribe, cf. fn 3. 12 Tov, Scribal Practices, 209. 13 So García Martínez et al., DJD 23:364: “The X may indicate that the

sentence continues, and that the blank space at the end of the line is not a

vacat.” Tov, Scribal Practices, 265, expresses some doubt over the reading of

128 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

and 11QTb from other such scribal marks is that the crosses in these two MSS appear not to the right but to the left of the text. If so, it is not the sign itself that is determinative of its function but its position in relation to the text.14

It is interesting to observe a slight definitional difference between Tov and Snyder, the latter insisting that the crosses are not those of “true line fillers” but rather a visual cue to the “textual performance.” Continuing his theory that the text possesses indicators of performance, Snyder instead considers the crosses to function as “line joiners”, a symbol of continued reading. The crosses supposedly function as an indicator to the reader that there should be no break in his reading.15 Whether one chooses to view the cross from the perspective of writing (Tov) or reading (Snyder), the interpretation remains problematic on a number of fronts:

the cross in 4Q252. In 11QTb (11Q20) the two crosses strangely occur in

adjacent columns and at the same line number (4:9 and 5:9) which would

make them presumably at the same distance down the page. See below for

an interpretation of this feature. 14 There is only one sign in 1QpHab that functions like the cross in

other mss and that is the stroke to the right of 4:12. See Tov, Scribal

Practices, 209. In 1QpHab indications of paragraphs are usually associated

with an open or closed section break (ibid., 264). 15 Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses,” 42–43. Snyder comments on the

harsh penalties given to the misreading of the Torah in the Qumran

community, and insists that the signs are textual indicators to prevent

misreading. Cf. “Perhaps the reader, or at least some readers, were

similarly unable to take in more than one or two words at a time” (ibid.,

43) and “Perhaps the language in question was familiar enough that it

would not have caused a reader to stumble” (ibid., 44). Furthermore,

Snyder suggests that the crosses may also function as a “reader beware”

symbol, indicating a complicated sentence, and to distinguish one

sentence from another (ibid., 44). Yet there are few examples that support

this theory, with many of the sentences surrounding the crosses appearing

no more challenging or complicated that sentences that do not end with a

cross. Additionally, if the presence of the crosses was to support the

reading of the text, why is the practice not more extensively attested?

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 129

i. Tov’s interpretation of the crosses as line fillers is based on a scribal practice in later-dated legal documents from Nahal Hever which do not conform to Qumran scribal practice.16 Further, when Tov states: “Writing of symbols and letters as line-fillers, especially in the papyri of Nahal Hever, in order to create a straight left edge to the column,”17 he seems to confuse their effect (justified left margin) with their function (to eliminate later tampering with the agreement). However, the comparison with the legal texts is informative, if only in a negative way; for it alerts us to the regularity of the use of the cross as a line filler where there is a blank at the end of a line. This is not the case with 1QpHab. The irregular usage in the pesher argues against its interpretation as a line filler.

ii. As observed by the editors, the use of the crosses is not consistently applied even within the same column, nor 11QTb (11Q20).

iii. The use of the cross at 1QpHab 3:14 where the blank properly stands before the פשרו (assuming the reading is correct) argues against the interpretation. Doudna18 argues that this is a scribal mistake but his whole argument for the occurrence of crosses is premised on the assumption that they are used as line fillers, a premise which we find difficult to accept.

iv. The cross can stand in the text where the scribe or reader should not expect a sense break or pause. Its presence is redundant. The best examples are found at 1QpHab 10:3 and 12:2, where את is followed by a cross separating it from the direct object that it marks. But cf. also 1QpHab 4:11 and 8:1. Snyder19 observes the problem in his theory

16 Tov, Scribal Practices, 209. Snyder refers to the crosses found in the

legal documents pap 5/6Hev 44 and 45 as true line fillers. Here, the

function of the crosses is to ensure that later edits and comments are not

made to legal documents. 17 Tov, Scribal Practices, 108. 18 Doudna, 4Q Pesher Nahum, 238–40. 19 Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses,” 45.

130 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

with 1QpHab 10:3 and 12:2, but appeals to the incompetence of the ancient reader to explain it.

3.2. The Vacats

The employment of paragraphing in modern texts functions as the visual cue of a larger sense unit by grouping one or more sentences under a governing idea or concept. The sentence may be the minimal unit of meaning but such units of meaning are themselves organized by the paragraph. Thought is thereby organised and structured. In the Qumran texts vacats appear to carry the same function, as Tov observes: “in Qumran texts of all types, this system of sense division was the rule rather than the exception.”20 This might all be well and good for the division of many Qumran texts into larger sense units, but it is not the case for 1QpHab. Here there is something odd in the way divisions are made. The text is a continuous commentary that divides the text of Hab 1–2 into smaller sections or lemmata, each of variable length, and then offers an interpretation on each. The structure is thus: lemma, interpretation, lemma, interpretation, lemma, interpretation, etc. The sense units are clear enough and one would reasonably expect paragraphing to occur in either of two ways, namely, (a) after each lemma and each interpretation, or (b) after each lemma and its interpretation.21 However, what we find is each lemma divided, either by a vacat or by the end of a line, from its interpretation but itself directly appended to the interpretation of the previous lemma up until 1QpHab 12:7 when all paragraphing ceases. In other

20 Tov, Scribal Practices, 143. 21 The second type of paragraphing is irregularly followed by the

scribe of 4QpPsa. Doudna, 4Q Pesher Nahum, 240–43, suggests a

mechanical use of vacats for every second pesher-lemma transition but

finds 5 exceptions which he terms “mistakes.” Snyder, “Naughts and

Crosses,” 36, adds 4QpIsaa to the pesharim that mark the pesher-lemma

transition, in this case by an open line. The first type of paragraphing is

occasionally found in 4QpNah where according to Doudna’s analysis

every lemma-pesher transition gets a short vacat and every third pesher-

lemma transition gets a long vacat (ibid. 243–50). But again there are

exceptions.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 131

words, the interpretation of the previous lemma and the following lemma form one unit of division. This is not a sense division at all!

How does one explain this? Snyder’s theory regarding the vacats focuses heavily on the “performance” and “score” of the text where the scribe purportedly establishes gaps to render the text “more suitable for performance purposes.”22 As he observes: “What is the function of this space? Obviously, in nearly all cases, it marks a semantic division in the text. Beyond this, however, it also prompts a corresponding ‘mark’ of some kind in the oral text produced by the reader.”23 Unfortunately, there are no prior or additional indicators to suggest that oral delivery required visual cues. One also asks why the pesher-lemma transitions were not marked. Bernstein notes that with continuous pesharim there is perhaps no need for an introductory formula for a citation from the prophetic base text.24 Can this observation be extended in some way to explain the lack of a division before each lemma? Unfortunately to do so would be to confuse “sense division” with “introductory formula.” The fact that no introductory formula is needed bears little on the question of why the conspicuous pesher-lemma semantic division has been omitted.

Tov observes: “It is probably safer to assume that the scribes often directed their attention to the type of relation between the unit they had just copied and that they were about to copy, without forming an opinion on the adjacent units.”25 He further speaks of the “context relevance of the spacing” in the pesharim.26 This may

22 Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses,” 40. 23 Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses,” 38. 24 Bernstein, “The Introductory Formulas,” 34, 66–68. The same may

not be the case when a quotation from another biblical book is cited or

when the pesher is not continuous or thematic. Unfortunately little

regularity is found across the pesharim. 25 Tov, Scribal Practices, 144. For a description of significance of type of

section breaks see especially 145–49. 26 Tov, Scribal Practices, 149, 152. Previously Tov had spoken of the

divisions being “impressionistic” and “ad hoc” as the scribes were not

“actively involved in content analysis” (ibid., 144) but it is unclear whether

this applies to the divisions in the pesharim.

132 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

well explain why a break may occur between the lemma and its interpretation, but it does little to explain why the same sort of sense division fails to occur when the interpretation ends and the next lemma is cited. Surely the scribe would have felt this transition as significant as the transition from lemma to interpretation. Moreover, it is somewhat odd to have transitions between the lemma and its interpretation doubly marked, first by an open or closed section and, second, by a heading indicated by פשר, whereas the more important transition between the interpretation of the previous lemma and the new lemma is not marked at all.

4. TOWARDS AN EXPLANATION

There is an important methodological consideration that needs to be stated at the outset. We seek here to account for features in the visual display of the text. It is assumed that the crosses and vacats have a semiotic or symbolic function, a visual cue to which we wish to assign significance and meaning. It is therefore not enough just to list all occurrences of the sign and then seek to offer a classification principle that makes sense of the usage. We must also look at counter-examples, instances where one might have expected the sign to be employed, but it is not. The organising principle must be rigorous enough to explain both occurrence and non-occurrence of the sign. That said, one must also take account of the possibility of human error, and, as any student of these scribal habits knows, this is an assumption often resorted to in order to explain anomalies. It follows that the most robust principle is the one that produces the least number of anomalies.

In the case of 1QpHab it is assumed that the scribe is making a copy of the text. Further, there is good reason to assume that in the process he is inserting vacats that were lacking in his Vorlage. The assumption is justified by what appears to be a reversion to the format of the original from 1QpHab 12:7 and continued by the second scribe. It is further supported by the vacat at 1QpHab 3:7. Tov notes the correction of פשר to פשו at 1QpHab 3:7 by the “superimposing of a very wide waw on the resh.”27 It appears that

27 Tov, Scribal Practices, 229.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 133

the scribe has misread his Vorlage and inserted the vacat before what he assumed was an occurrence of פשר. The vacat would not have stood in the original, which after all is in the midst of a citation from Habakkuk. As an aside, it makes more sense if this correction was made at a later reading of the text, as one would assume that if the correction was made at the time of copying, the scribe would realise that the space before the correction was no longer meaningful and fill it with the correction. We are left with the impression that the scribe is somewhat incompetent.28 The correction may have been made by a later scribe/reader, perhaps even the scribe who inserted the tetragrammaton. Cf. also 11QTb (11Q20) where the corrections are made by a different hand.29

The question arises as to whether the dilemma of the crosses might be solved by the hypothesis of two Vorlagen. Hartmut Stegemann had suggested that the crosses marked the end of a column in an earlier Vorlage.30 The evidence of 11QTb (11Q20)

28 On the imprecision of 1QpHab see Tov, Scribal Practices, 267:

“A telling example of such imprecision is visible in pesharim such as

1QpHab in which the biblical text is not well represented (imprecision,

mistakes, contextual adaptations), but it is still made the base for sectarian

exegesis. Among other things, some of the interpretations in 1QpHab are

based on readings different from the biblical text in the lemma.” It is

unclear whether all imprecision is to be put down to the copyist, his

Vorlage or both. 29 García Martínez et al., DJD 23:364. 30 The idea is acknowledged as a personal communication by Hanan

Eshel, “The Two Historical Layers of Pesher Habakkuk,” in Northern

Lights on the Dead Sea Scrolls (ed. Anders Klostergaard Petersen et al;

Leiden: Brill, 2009), 108–09. Stegemann’s hypothesis assumes that the

extant copy of 1QpHab is third-hand; the first copyist marked the column

ends of the autograph in his copy with crosses and the second copyist at

first misunderstood the cross as an ’aleph (col. 2) but later realized his

error reverting to crosses. But he also at times realized that the crosses

were just scribal marks and so just omitted them. The hypothesis is

problematic on a number of fronts: (a) it fails to explain the occasions

when crosses stand close together in the same column; (b) it assumes a

rather perfunctory scribal habit, sometimes retaining and sometimes

134 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

might suggest as much, as the two crosses occur at the same line number in adjacent columns, i.e., at 11QTb (11Q20) 4:9 and 5:9, the underlying assumption being that the Vorlage and its copy consisted of the same number of lines in their columns. The problem with 1QpHab is that in cols. 3, 4, 6 and 9 there are two crosses in each. While this may not present a problem as the two crosses separate in the later columns (e.g., the crosses in col. 9 are separated by eleven intervening lines), it is most certainly a problem in cols. 3 and 4 where the crosses are only separated by one and two lines respectively. But it is here that the hypothesis of two Vorlagen proves useful, if it is assumed that the first cross in each of these columns marked the column end (or equally column beginning) in one Vorlage and the second the column end in the second. Presumably the mark facilitated in some fashion the comparison of the copy with its Vorlage either for subsequent scribal checking of the copy or because the Vorlage was a master/authoritative copy and continued to be consulted.

5. A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN

A number of indications for the use of more than one source in 1QpHab have been cited. They include:

5.1. The Double Use of Pesher (Column 2)

There is a double use of pesher at 1QpHab 2:1 and 5 under the one lemma. Snyder in commenting on the vacat before the second פשר at 1QpHab 2:5 observes: “On this occasion, it might indicate that a scribe is copying from more than one manuscript, or perhaps, copying from a manuscript with a marginal addition that needed to be inserted into the text.”31 It should also be noted that the second pesher is introduced by וכן which alerts the hearer to a second

omitting crosses; and (c) it assumes that the end of lines in first and

second copies fall at the same point in the text. Eshel uses the theory to

argue two redactions with additions being made in cols. 2:10–4:13, and

cols. 5:12–6:12 after 63 BCE. 31 Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses,” 39–40.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 135

interpretation and that א occurs, like the crosses, in the margin of 1QpHab 2:5 against the second pesher.

There are certain differences between the two pesharim: i. The first pesher looks back to the community’s past.

It recounts the failure of the traitors to trust the teacher of righteousness and to trust the covenant of God. The form of the verbs is perfect. The second pesher refers to a future time, the last of days. It talks about what is going to occur and uses the imperfect.

ii. The teacher appears to figure in both pesharim, though in the first he is the bearer of the words from God’s mouth, whereas in the second he is the interpreter of the words of the prophets. More importantly in the first pesher the figure is called “the teacher of righteousness,” whereas in the second he is just known as “the priest.”

A good case can be made that the double pesher has used two distinct interpretations that did not arise concurrently. Instead of merging his sources, the scribe gives the two interpretations in full, perhaps because the length and complexity of the passages made conflation unwieldy.

5.2. Requotation Formulae and Irregular Vacats

The requotation formulae 1) כיא הוא אשר אמרQpHab 3:2, 13–14; 5:6) or ואשר אמר (1QpHab 6:2; 7:3; 9:2–3; 10:1–2; 12:6) are used 8 times in 1QpHab and may reflect the supplementing of one source with another.32 There are also two occasions where a

32 The requotation formula changes from ואה אשר אמר אמר to כיא

from col. 6. The former indicates by its use of the logical ואשר

conjunction כיא that the citation is offered as justification for what has

preceded; in other words, the biblical text is cited as a “proof-text,” as it

were. The latter formula, on the other hand, as Nitzan, Pesher Habakkuk,

8–9, notes, facilitates the placing of the interpretation after the citation.

Bernstein, “The Introductory Formulas,” 52, 61, 67, further observes that

it can be resumptive, picking up the flow of the interpretation after an

interruption of some sort and thus refocusing the interpretation back onto

the original text. The variation in formulae thus functions as a sequencing

136 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

requotation is not accompanied with the formula, i.e., 1QpHab 4:13, 6:5. Of particular interest among requotations with or without formulae are those instances where the requotation is followed by its own interpretation, i.e., 1QpHab 4:13–14; 6:2–3, 5–6; 7:3–4; 9:3–4; 10:2–3; 12:6–7.33 Clearly, requotations entail a second interpretation for the passage differing only from the double pesher discussed above by the repetition of the lemma or part thereof.

To these examples may be added the use of irregular vacats at 1QpHab 5:11; 8:3; 9:7 and 12:5–6, two of which coincide with the requotation formula. Snyder34 sees these as perhaps “comments added to the original interpretation” and considers them “parenthetical remarks.” Indeed they are that in terms of their content, but this does little to explain the use of the vacat before them. Other features need also to be observed:

i. The text after the vacats is introduced by a form of Of the former at 1QpHab 5:11 it .(1x) כי or (3x) אשרis used as the relative pronoun (“who”), at 7:3 the relative pronoun is prefixed with the vav to form a citation formula (ואשר אמר – “and that which he said”), and at 1QpHab 12:6 it is prefixed by kaf to form a comparative conjunction, i.e., “just as.” The one instance of כי (1QpHab 9:7) functions as a logical conjunction offering an explanation, i.e., “for.” All four instances thus allow further information to be added;

device. But the question still stands: why change the placement of the

interpretation and thus the requotation formula? George J. Brooke,

Exegesis at Qumran, 4QFlorilegium in its Jewish Context (JSOTSup 29;

Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1985), 136–37, believes that

requotation is placed in a subordinate position to the main textual citation.

This might seem a logical inference, but is it the case in 1QpHab where

the requotation can be given the same divisional indicator, namely, the

citation is followed by a blank and פשר? The scribe treats it no differently

from the treatment he gives the larger citation. 33 A number of requotations (1QpHab 3:2, 13–14; 9:7–9) move

directly into the next lemma and will not be considered here. 34 Snyder, “Naughts and Crosses,” 41.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 137

ii. In one instance (1QpHab 7:3) the blank precedes a requotation formula and in another (1QpHab 12:3) in close proximity with it.

It is our contention that the irregular vacats was one way in which the scribe marked the insertion of material from a second version of the pesher. In other words, the scribe of 1QpHab may have had two Vorlagen before him and, as occasion required, moved from one to the other and marked the transfer with a vacat.

5.3. Different Versions of the Prophet

The quotations of Hab 1:17 (1QpHab 1:8–9) and 2:16 (1QpHab 11:8–11), it is argued, indicate that the scribe was familiar with another version of the text than that of the MT. Due to the agreement with Greek versions Lim35 postulates that the scribe had open in front of him two versions of the prophet, one in Hebrew and the other in Greek. This seems an unnecessary assumption given that the assumed error arises in the reading or hearing of the Hebrew text itself (חרבו for חרמו in the MT at Hab 1:17 and הרעל for הערל in the MT at Hab 2:16). An alternate solution is that the scribe was working either from two Hebrew versions either of the prophet and/or his pesharim.

To the above consideration we would add observations on two further pesharim and their use of אשר in 1QpHab 5:5 and 12:5 and 9. Both Karl Elliger and Bilhah Nitzan discuss them under either a discussion of the nota relationis or a section treating how expansions in interpretation are structured.36

35 Timothy H. Lim, “The Qumran Scrolls, Multilingualism, and

Biblical Interpretation,” in Religion in the Dead Sea Scrolls (ed. John J. Collins

and Robert A. Kugler; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 70–71. 36 Karl Elliger, Studien zum Habakuk-Kommentar vom Totem Meer

(Tübingen: Mohr–Siebeck, 1953), 87–88, and Nitzan, Pesher Habakkuk,

85–89.

138 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

5.4. Awkward Anaphora and a Different Interpretation in the Requotation (Column 5)

It is noteworthy that the scribe reads מוכיחו (hiphil participle with added pronominal suffix) instead of hiphil infinitive without suffix as in the MT. Whereas the MT of Habakkuk speaks of God’s making “him” for judgement and for reproof, i.e., “he” was to be the object of judgement and reproof, the pesherist has understood that God has appointed “him” for judge and as reprover of another. The object of that reproof is now the third person singular pronominal suffix on מוכיח. It will also be noted that the use of the pronominal suffix with מוכיח (v.1) and of the noun in construct with תוכחה (v.10) indicates an objective genitive, and it will be argued that this is also the case at v.4.37 The pesher of v.3–5 makes clear who the two persons indicated by the third person pronouns are. It is God’s chosen one (the first “him”) through whom God will judge his people (the second “him”). We translate: “the interpretation of the matter: God will not destroy his people by the hand of the nations, but by the hand of his chosen one38 God will give judgement of all the nations and in the reproof of them (the nations) all the evil of his people will be declared guilty.”

37 Note also the grammatically suspect reading of the MT at Hab 2:1

(1QpHab 6:14) is consistent with this stated use of the objective genitive. 38 The term בחירו (his chosen one) has been viewed as written

defectively for בחיריו (his chosen ones) with reference made to a similar

defective spelling in the next line (5:5 מצוותו) and the use of the plural

noun at 10:13 and perhaps again at 9:12 (spelt defectively, as here, but

can be construed as a singular referring to the teacher). The result is בחירו

that the pronominal suffix in (5:4) תוכחתם and the relative pronoun אשר

(5:5) are seen to find their antecedent in these chosen ones. But the

construction is problematic: (a) the more immediate and natural

antecedents are “all the nations” and “the evil among his people,”

respectively; (b) one must construe the pronominal suffix in תוכחתם as a

subjective genitive which it is not otherwise; and (c) the point of reference

in the text of Habakkuk refers to a singular מוכיח. See also William H.

Brownlee, “The Jerusalem Habakkuk Scroll,” BASOR 112 (1948): 1–18,

cf. p.17 n.34.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 139

The above understanding of the passage makes good sense to this point and unlike most translations does not require any complicated anaphora. But the reason for the complication is the problem presented by the use of אשר and its clause in 1QpHab 5:5. According to the understanding of the preceding lines the clause does not make sense. We translate: “who kept his commands in their hardship for that is what it says ‘more pure of eyes than to behold evil’ (vacat). Its interpretation: they did not fornicate after their eyes in the time of evil.” The problem is the antecedent of “who kept” (1 אשר שמרוQpHab 5:5); as argued above and in the footnote, it more naturally refers to “all the evil of his people.”39 To make sense of the clause one would need to insert the negative, i.e., “who did not keep his commands...” But to insert the negative makes the recitation and its interpretation inconsistent, for the recitation refers back to those who keep his commands and identifies them as those “who do not fornicate after their eyes.”

We thus find that two sections make sense by themselves but when joined a problem arises. It appears that two pesharim have been joined and that אשר in 1QpHab 5:5 formed the point of juncture. For Nitzan40 the problematic אשר is used to join two different and contradictory pesharim, one interpreting Hab 1:12b (טהור עינים מראות ברע) and the other Hab 1:13a ,(למוכיחו יסדתו)

39 Nitzan, Pesher Habakkuk, 165, concedes the awkwardness to the

clause, observing that the expression does not refer to the “evil of his

people” though its position within the pesher would suggest otherwise.

The tension is not resolved but the problematic clause is interpreted

retrospectively in the light of the following requotation, namely, טהור

ברע מראות יםעינ . Maurya P. Horgan, Pesharim: Qumran Interpretations of the

Biblical Books (CBQMS 8; Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of

America, 1979), 32, also concedes the awkwardness of the text and offers

two possible solutions, one relying on the plural reading of בחיריו in 5:4

and the other on a scribal error that relocated the אשר clause from

following immediately after עמו in 5:3. 40 Nitzan, Pesher Habakkuk, 88.

140 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

without any topical nexus between them.41 In other words, אשר functions as a conjunction (מלת הזיקה) and the lack of clarity arising from this is explained by the loss of a requotation preceding the second pesher. The scribe has thus rephrased a text that read:

ואשר אמר טהור עינים מראות ברע

והבט אל עמל לוא תוכל

פשרו על בחירו

אשר שמרו מצוותו בצר למו

ולוא זנו אחר עיניהם בקץ הרשעה

The reason for the rephrasing is conjectured by Nitzan in terms of a desire to maintain a certain “structural tempo.” An equally plausible explanation can be found in the hypothesis that 1QpHab 5:5–8 has been added from a second Vorlage which offered an interpretation of “purer of eyes than to behold evil” that referred to the obedient community who did not fornicate after their eyes. In other words, the אשר is the relic of פשרו אשר in the second Vorlage. The scribe, however, as he proceeded to copy the second interpretation, realized the problem caused by אשר and so was forced to add the requotation after citing the pesher.

5.5. A Different Requotation (Column 12)

The citations of Hab 2:17 at 1QpHab 11:17–12:1—“[For the violation of Lebanon will cover you, and destruction of animals] will appal you, owing to blood of man and violence (against) land, city and all the inhabitants in it”—and its requotation at 1QpHab 12:6-7—“owing to blood of city and the violence (against) land”—

41 It will also be noted that the first pesher has a future focus

(imperfect verbs) on the judgment of wicked whereas the second looks to

the past actions (perfect verbs) of the obedience at a time of difficulty for

them. Elliger, Studien zum Habakuk-Kommentar, 88, 181, avoids the problem

at 5:5 by translating אשר and its dependent clause by insofern sie seine Gebote

gehalten haben, als sie in der Bedrängnis waren.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 141

with both afforded a pesher each.42 The first pesher finds a reference to the Wicked Priest by the identification of Lebanon as “the Council of the Community” and the animals as “the simple of Judah.” In the second pesher “man” is dropped and “city” inserted in its place. In so doing, the word order between “land” and “city” also changes which in turn requires the omission of the expression “and all the inhabitants in it (i.e., presumably the city).”43 With those changes in hand the requotation is interpreted by extending the list of identifications. The “city” is Jerusalem “in which the Wicked Priest commits his deeds of abomination” and “land” is “the cities of Judah which he plundered.” The question arises as to whether the requotation introduces a variant textual tradition and its interpretation, or whether the pesherist himself has abbreviated and rearranged the text for the purpose of interpretation. Though there can be no sure decision in the matter, the fact that the words are introduced by a citation formula weighs in favour of textual variation which in turn then alleviates the need to assume that a fairly cavalier attitude to the transmission of the prophetic word was adopted by the sectarians. In other words, a case can be made that the scribe is following another version of Habakkuk and perhaps therefore a different commentary as well.

A number of other points of interest should be noted with regard to the lemma, its requotation and their interpretations at 1QpHab 11:17–12:10.

i. The introduction to the pesher in 1QpHab 12:2 breaks with the scribe’s custom in that the usual formulaic omits פשר הדבר אשר or פשרו על <TOPIC> אשר The pesher that follows the formula is then .אשר

42 Doudna, 4Q Pesher Nahum, 67–68, argues against Timothy H. Lim,

Holy Scripture in the Qumran Commentaries and Pauline Letters (Oxford:

Clarendon, 1997), 69–109, contending instead that the scribe is not

deliberately introducing exegetical variants but rearranging or abbreviating

the words. But such an argument ignores the introduction of the passage

by a citation formula and assumes a fairly cavalier attitude to the

transmission of a prophetic text. 43 Cf. Doudna, 4Q Pesher Nahum, 67–68, and Lim, Holy Scripture, 69–

109.

142 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

connected with its TOPIC no longer with the relative pronoun (אשר) but with an infinitive which breaks with the usual scribal habit.

ii. The formulaic introduction to the pesher in 1QpHab 12:7 also breaks with the scribe’s custom in that פשרו is neither preceded by a vacat nor followed by על or It is also at this point in the commentary that the .אשרscribe appears to drop his customary insertion of the vacat before פשר, cf. 1QpHab 12:12.

iii. The requotation formula at 1QpHab 13:6 is preceded by an irregular vacat (end of 1QpHab 12:5) followed by the parenthetical remark “just as he had devised to destroy the poor” (beginning of 1QpHab 12:6).

iv. The clause (אשר ישופטנו אל לכלה—“whom God will sentence to destruction”) immediately preceding the irregular vacat (end of 1QpHab 12:5) is awkward in its use of anaphora; the pronominal suffix in ישופטנו and its relative pronoun אשר must reach back across the more immediate antecedents and beyond the logical conjunction כיא to find their referent in the Wicked Priest of 1QpHab 12:2. As Elliger observes: “das אשר sich über zwei Zwischensätze hinweg so weit zurückbezieht auf die in der Einleitungsformel xii.2 genannte Person, daß es den Anschluß fast verloren hat.”44 This awkwardness combined with the

44 Elliger, Studien zum Habakuk-Kommentar, 88, 220. אשר is translated

by insofern at both 1QpHab 12:5 and 12:9. Cf. also William H. Brownlee,

The Midrash Pesher of Habakkuk (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1979), 205.

Horgan, Pesharim, 51–52, recognizes the problem caused by the distant

antecedent and accordingly interprets the אשר clause in terms of levels or

stages of interpretation. The original pesher had read “The interpretation of

the passage concerns the Wicked Priest … whom God will sentence to

complete destruction because he plotted to destroy completely the poor

ones,” but this interpretation has now been interrupted by later

explanatory comment. There does not appear to be any attempt to relate

the problematic אשר clause here in col. 12 to the parallel phenomenon

observed in col. 5.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 143

irregularity in the formulaic introduction noted already in point 1) begs the question as to whether our clause was at some time more closely associated with the pesher formula in 1QpHab 12:2, for example, to read—“the interpretation of the word concerns the Wicked Priest whom God will sentence to destruction.”45

v. The identity of the cattle (plural) in 1QpHab 12:4 with the “the simple one(s?) of Judah doing torah” requires a little interpretational manoeuvring to make the singular participle agree with the preceding nouns.46 Given that there is no allegorical identification of אדם in the pesher, it might be suggested that “the one doing torah” once qualified the now lost identification. In other words, the naming of the next topic (i.e., אדם)

45 Nitzan, Pesher Habakkuk, 88–89 and 194–95, notes that the scribe

departs from his usual custom by the insertion of parenthetical material in

lines 3–5. The subject matter of the pesher is introduced (i.e., the wicked

priest, 1QpHab 12:2) to which is then added the insight concerning his

punishment (1QpHab 12:2–3). In speaking of the punishment the scribe

has introduced “the poor” and now felt the need to explain how he was

able to identify them from the prophet’s words (1QpHab 12:3–5). After

offering his explanation the scribe again returns to the subject matter of

the pesher, i.e., the wicked priest, and uses אשר, his usual linking

expression, to resume his interpretation (אשר ישופטנו אל לכלה). In other

words, the identification of the poor is a parenthetical insertion which is

framed by the pesher at large. Nitzan’s argument (see also p.38 on its use

to add an issue not addressed in the interpreted text of the prophet)

explains the order in which the interpretations appear but does not

explain the use of אשר itself as a conjunction (מלת הזיקה) used to join a

.משפט טפל46 Brownlee, “Further Correction of the Translation of the Habakkuk

Scroll,” BASOR 116 (1949): 14–16, cf. p.16, notes the awkwardness of the

singular עושה and suggests it be amended to a construct plural עושי. It will

be noted that this construct plural of the participle is found at 1QpHab

7:11 and 8:1. A similarly awkward but reversed (singular noun identified

with plural noun) identification is found at 1QpHab 12:9.

144 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

and its allegorical identification may have been omitted with the result that the topic of cattle and its allegorical interpretation in the plural (i.e., the simple ones of Judah) are now associated with what remains of the description of the allegorical identity of אדם, i.e., the one doing torah. If accepted, significance attaches to the participial expression which now underlines the different natures and rewards of the Wicked Priest (the TOPIC of the interpretation) whom God will sentence to destruction and the man who does torah. There may also be an allusion in the use of אדם to the Adam who rejected torah and the adam who does torah, an association on which Paul also appears to draw (Rom 5:14–15 and 1 Cor 15:45).

vi. Both the relative clause in 1QpHab 12:5 with its dependent כאשר clause and the requotation formula with its reworded lemma break the listing of the allegorical identities. No requotation formula would have been needed had the listing just proceeded as follows: “for Lebanon is the council of the community, the cattle are the simple of Judah, the town is Jerusalem and the violence of the land the cities of Judah.” A case can be made that the interposing of new material from a separate source caused the omissions referred to under v (i.e., the interpretation of the cattle and the reference to אדם) and raised the need to refocus the interpretation of the original lemma by the requotation of part of the lemma.

vii. Not only do the citations differ but the interpretation of their referents also changes focus from the community (a metaphorical interpretation) to the nation (a more literal interpretation). The same phrase that is being interpreted here occurs twice in Habakkuk, namely, at Hab 2:8 and 2:17. The earlier lemma and its pesher (1QpHab 9:7–12) are introduced by an irregular vacat (1QpHab 9:7) which appears to redirect the TOPIC away from the last priests of Jerusalem with its future focus to the Kittim and presumably to the punishment they will exact. However, as the citation of the lemma continues the focus changes to the past, and

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 145

the Wicked Priest and his crimes against the teacher. Again like the interpretation of Lebanon and cattle at 1QpHab 12:3–6, the concern is the community and the wrongs done to it and its leader. But unlike the later interpretation the judgement is not considered as future. There is no attempt in 1QpHab 9:9–12 to allegorize each of the nouns in the lemma as occurs in 12, but it is significant that the expressions מדמי אדם and יושבי בה appear to prompt this earlier interpret-ation. In other words, the interpretation in column 9 takes its prompt from אדם, a term that is altogether missing from the later interpretation of the phrase in column 12.

viii. There is rhetorical repetition with noted repetition in theme and word that is largely subsumed in the structure of the interpretation as it now stands.

לשלם לו את גמלו אשר גמל על אביונים

ישופטנו אל לכלה כאשר זמם לכלות אביונים

אשר גזל הון אביונים

It is the third instance that breaks the structure somewhat by the omission of the judgement theme. In turn this causes the relative clause to be positioned awkwardly without an immediate antecedent and grammatically unconnected with the interpretational identification which precedes it.47

47 See Shemaryahu Talmon, “Notes on the Habakkuk Scroll,” VT 1

(1951): 37, who accounts for the awkwardness of the relative pronoun

(12:9) by the omission of a pronominal suffix to הון in the relative clause

which referred back to “cities of Judah.” The explanation does not resolve

the difficulty of the clause in that it leaves אביונים hanging. Eduard Lohse,

Die Texte aus Qumran (Munich: Kösel, 1986), 243 reads the relative as

“where,” thus assuming an ellipsis of משם from the relative clause.

Brownlee, “Further Light on Habakkuk,” BASOR 114 (1949): 9–10, at

p.10, translates the relative as the causal conjunction “because.”

146 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

An explanation for the above difficulties is not hard to find, if one hypothesises that the scribe has sought at this point to combine two different pesharim on the same verse, one pesher listing the allegorical identities of Lebanon, cattle, man, city and land and the other speaking of the Wicked Priest and his judgement.48 As in the discussion of col. 5 above, אשר in 1QpHab 12:5 is a relic of a פשר...אשר construction that remains after the combination of diverse pesharim.

In fine, it is argued that whereas in col. 2 the scribe used two pesharim, each preceded by a vacat, in cols. 5 and 12 the practice was changed as he sought to interweave the two pesharim into one continuous interpretation with the relative pronoun/particle forming the point of connection as a relic of the פשר...אשר construction. Irregular vacats are also to be associated with the presence of two Vorlagen and indicate that one source has been supplemented with the text from the other. However, as the scribe has consciously decided to employ vacats to indicate the move from lemma to interpretation and not otherwise except for his error at 1QpHab 3:7 and the four irregular vacats, our explanation for the latter, as it now stands, is inadequate. A possible answer is to be found in the double pesher at 1QpHab 2:1 and 5. In the second of the pesharim the scribe has moved from one Vorlage to the other and his use of the vacat before the move has suggested itself to him as an adequate marker for future use. In what follows it is argued that the irregular vacats mark not only a change of Vorlage but also a change in the Vorlage whose text was to be preferred. In other words, the scribe copied from one Vorlage at a time supplementing it from the other but on occasion swapped the Vorlagen around.

48 Further confirmation of ellipsis in the use of אשר is found in 12:9.

In this instance we have a short requotation (“violent of land”) followed

by its identification with the cities of Judah. Then אשר joins a further

interpretative comment which is not coordinated or related to what has

preceded it, i.e., גזל הון אביונים.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 147

6. CONCLUSION

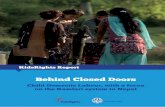

Does the hypothesis that the scribe has used two Vorlagen offer a better explanation for the distribution of crosses in 1QpHab? The question is difficult to answer for we cannot assume either (a) scribal consistency in the deployment of crosses; (b) the use of only one source at a time; (c) a consistent marking of changes between sources; or (d) a distinct thematic content for each source. But the distribution of crosses does appear significant. Leaving aside the ambiguous use of ’aleph in col. 2 and the uncertain reading at 9:16, there are 11 crosses distributed in a manner that is statistically significant, for they are located either in lines 1–4 or lines 11–14. In other words, the central band (lines 5–10) consisting of 6 lines displays no cross. Unfortunately, as the last lines in each column are lost, we are uncertain what was there and must confine conjecture to the evidence at hand.

The aim of what follows is not to prove the hypothesis but to show that a reasonable explanation for the scribal features can be offered under the assumption of two Vorlagen. On the assumption that the crosses marked column ends in the two Vorlagen, we mark the crosses in the table below as belonging to either Vorlage A (Xa) or B (Xb). Also for the purpose of the argument, it is assumed that the irregular vacats mark a change between which of the Vorlagen the scribe is preferring from time to time and which he chooses to use to supplement it.49 The change between Vorlagen is marked by clear (Vorlage B to be designed B) and lighter grey (Vorlage A to be designated A) shading in the table. The darker grey shading

49 There are two other assumptions that need to be noted. They are

that: (a) 1QpHab followed the written dimensions of its Vorlagen (i.e.,

column width and number of lines per column were similar). It seems

reasonable to assume that a scribe in selecting and ruling a parchment

consciously followed the dimensions of the texts to be copied. After all it

allowed him to know the size of the document to prepare; and (b) as the

scribe moved from one Vorlage to the next he copied the text of that with

occasional supplements from the other Vorlage until the next change as

marked by the irregular vacat. In other words the scribe is only copying

one Vorlage at a time but noting the ends of the columns of each in his

copy. This is the easiest way of merging two approximately similar texts.

148 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

indicates the lost bottom of the manuscript. So constructed, an interesting result emerges from the table. The ends of the columns in A in cols. 3–6 are approximately equidistant from each other. Col. 5 does not contain a cross but the end of the column in A may have fallen at a point where a change between Vorlagen occurred and been omitted. In this respect we note the occurrence of the irregular vacat at 1QpHab 5:11. It is also observed that the ends of the columns in B in cols. 3 and 4 are equidistant, but that no cross appears equidistant in col. 5; it is perhaps pushed forward to col. 6:4, a full seven lines after it was to be expected. Alternatively, a cross may have stood in the lost lines at the end of col. 5 in B. If an explanation were to be sought for this shifting forward of the cross, either to the lost lines at the end of col. 5 or to col. 6:4, it might be explained by the insertion of additional material from one source (A) into the other (B) between 4:14 to 5:10. One can find this material in the requotations and commentary at 4:13–16 and 5:6–8. Assuming the longer shift forward to 1QpHab 6:4, and a possible change of Vorlagen at the irregular vacat in col. 7 (i.e., 1QpHab 7:3) with an effective loss of a column end, we find that the column ends in B are roughly equidistant across cols. 6–10 and 12. Indeed, and this is significant, the column ends are exactly equidistant when B is itself being followed without any additions from A (1QpHab 3:14 and 4:14 then 8:1 and 9:1). Even so, col. 11 lacks a cross for the end of the column in B, but under our hypothesis it might be suggested that this was an accidental omission as the scribe was preferring A at this time.50 Other explanations might also be offered; for example, that the scribe omitted it having finished the quotation of his lemma (Hab 2:15) up against the left margin, or that the cross might have stood in the lost portion at the end of col. 10. One also notes under this hypothesis that at 1QpHab 9:13 the end of the column in A is again indicated on the occasion when the scribe again returns to follow and preference that Vorlage. Interestingly, though the column ends in B shift forward, this is not the case with the column end of A as indicated by the cross at 1QpHab 9:13. From

50 This may also explain the loss of the cross for the end of Vorlage B

at the top of col. 7.

A CASE FOR TWO VORLAGEN 149

this it would follow that apart from 1QpHab cols. 4:15 to 5:10 the length of lemma and pesher may not have differed much between the two Vorlagen.

Distribution of Crosses and Irregular Vacats

Clear shading = B; lighter grey shading = A; Xa = cross in A; Xb = cross in B; vac = irregular vacat; m.2 = change of scribe

Line Num-ber

Column Number

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1 Xb Xb

2 Xb

3 vac Xb

4 Xb

א 5

6 vac

7 vac

8

9

10

11 Xa vac

12 Xa Xa

13 Xa m.2

14 Xb Xb

15

16

17

The advantage of the hypothesis of two Vorlagen and changes between the copying of them is that it (a) explains the two crosses in cols. 3, 4 and 9; (b) gives a felicitous explanation for the regularity of crosses between adjacent columns, especially with regard to Xb both in cols. 3 and 4 and in cols. 8 and 9 under the hypothesis that Vorlage B is being preferred at this point; and (c)

150 KETER SHEM TOV: COLLECTED ESSAYS

accounts for the distribution of crosses in the bands of lines 11–14 (cols. 3–6 and 9) and of lines 1–4 (cols. 6–10 and 12). Under any hypothesis some explanation needs to be given for this phenomenon. The weaknesses of the hypothesis are that: (a) in cols. 1 and 2, as far as we can tell, the scribe does not mark the column endings of his Vorlagen; and (b) from col. 7 on, though with the exception of col. 9, the scribe appears to omit the marking of column endings for A. Can we assume scribal inconsistency, e.g., that the scribe after col. 6 decided not to mark the end of A when following the other Vorlage and that even when following A he decided to continue to mark the end of B? There seems no reason why not, as under any hypothesis it appears a necessity.