winter 2004-05 - The Archaeological Conservancy

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of winter 2004-05 - The Archaeological Conservancy

7 525274 91765

44>

american archaeologyamerican archaeologyWINTER 2004-05

THE CONSERVANCY TURNS 25 • PREHISTORIC MUSIC • A PASSPORT TO THE PAST

a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 8 No. 4

7 525274 91765

44>

$3

.95

A Tale ofConflictIn Texas

A Tale ofConflictIn Texas

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/18/04 1:49 PM Page C1

archaeological toursled by noted scholars

superb itineraries, unsurpassed service

For the past 30 years, Archaeological Tours has been arranging specialized tours for a discriminating clientele.Our tours feature distinguished scholars who stress the historical, anthropological and archaeological aspects of the areas visited. We offer a unique opportunity for tour participants to see and understand historically important and culturally significant areas of the world.

Professor John Henderson in Tikal

MAYA SUPERPOWERSThis tour examines the ferocious political strugglesbetween the Maya superpowers in the Late Classicalperiod. At the heart of these struggles was a bitterantagonism between Tikal in Guatemala and Calakmulin Mexico. New roads will allow us to visit these ancientcities, as well as Lamanai, the large archaeologicalproject at Caracol in Belize, Copan and Edzna andKohunlich in Mexico. The tour also provides opportunitiesto experience the still-pristine tropical forest in the MayaBiosphere Reserves. Our adventure ends in Campeche, aUNESCO World Heritage Site.MARCH 5 – 21, 2005 17 DAYSLed by Prof. Jeffrey Blomster, George Washington U.

NOVEMBER 11 – 27, 2005 Led by Prof. John Henderson, Cornell University

GREAT MUSEUMS: Byzantine to BaroqueAs we travel from Assisi to Venice, this spectacular tourwill offer a unique opportunity to trace the developmentof art and history out of antiquity toward modernity inboth the Eastern and Western Christian worlds.The tourbegins with four days in Assisi, including a day trip tomedieval Cortona. It then continues to Arezzo, Paduaand Ravenna, where we will see churches adorned withsome of the richest mosaics in Europe. Our tour endswith three glorious days in Venice. Throughout we willexperience the sources of visual inspiration for athousand years of art while sampling the food and drinkthat have enhanced the Italian world since it was thecenter of the Roman Republic and Empire.MARCH 2 – 13, 2005 12 DAYSLed by Prof. Ori Z. Soltes, Georgetown University

ANCIENT EGYPTSpecially Designed for Grandparents and Their

Grandchildren

While traveling to the major sites with our scholar,grandparents will be sharing the irreplaceableexperience of discovery with their grandchildren.Highlights of the tour include a five-day Nile cruise, theGreat Pyramids and Sphinx, the Egyptian Museum,Cairo’s Islamic monuments and bazaars, camel ridesand many other exciting events. Our fun-filled days willalso include special events shared with English-speaking Egyptian children and their grandparents.MARCH 9 – 20, 2005 12 DAYSLed by Prof. Lanny Bell, Brown University

MALTA, SARDINIA & CORSICAThis unusual tour will explore the ancient civilizationsof these three islands.Tour highlights include immensemegalithic temples on Malta, Sardinia’s uniquenuraghes, and the mysterious cult sites on Corsica, aswell as the ancient remains of the Phoenicians,Romans, Greeks and Crusader knights. The islands’wild and beautiful settings and their wonderful cuisineswill enhance our touring of these archaeological sites.MAY 4 – 21, 2005 18 DAYSLed by Dr. Mattanyah Zohar, Hebrew University

SILK ROAD OF CHINAThis exotic tour traces the fabled Silk Road from Xian toKashgar and includes remote Kuqa, famed for the KizilThousand Buddha Caves, Ürümqi, and the fascinatingSunday bazaar at Kashgar. We will explore the caravanoasis of Turfan, Dunhuang’s spectacular grottoes ofsculpture and murals, the Ta’er Tibetan monastery,Buddhist caves at Binglingsi, the extraordinaryarchaeological sites around Xian and Lanzhou’sexcellent museum, ending in Beijing.MAY 4 – 25, 2005 22 DAYSLed by Prof. James Millward, Georgetown University

CHINA’S SACRED LANDSCAPESwith an Optional Yangtze River Cruise

This very special new tour brings us into the China ofpast ages, its walled cities, vibrant temples andmountain scenery. Visiting three regions, each distinct incharacter and landscape, touring includes the ancienttemples of Wutaishan and Datong, the Buddhist grottoesat Yungang and Tianlongshan, as well as Mount Tai inShandong, which offers China’s most sacred peaks andthe enduring shrines to Confucius. Lastly, Hangzhou, longa premier spot of beauty, offers us rolling hills, waterwaysand peaceful temples and pagodas. The tour ends withShanghai’s exceptional new museum.MAY 15 – JUNE 4, 2005 21 DAYSLed by Prof. Robert Thorp, Washington University

TUNISIABased in Tunis for four days, we will spend a day atPhoenician Carthage, and visit Roman Dougga, ThuburboMajus and the unique underground Numidian capital atBulla Regia. We will tour one of the largest Roman sites inTunisia at Sbeitla, the Islamic monuments in Kairouan andTunisia’s major Byzantine sites. We will spend two daysexploring oases in the Sahara Desert plus Berbertroglodyte villages and exotic bazaars.MAY 20 – JUNE 5, 2005 17 DAYSLed by Prof. Pedar Foss, DePauw University

EASTERN TURKEYRemote and unspoiled Eastern Turkey is one of the mostinteresting areas of the country. Our tour features Antakya(Antioch), Harran, Nemrut Dag, the Armenian andUrartian sites around Lake Van, the Armenian churches ofAni, the Black Sea coast and the Hittite sites of Altintepe,Karatepe, Alaca Höyük and Hattusa — ending in Ankara.MAY 29 – JUNE 17, 2005 20 DAYSLed by Dr. Mattanyah Zohar, Hebrew University

ETRUSCAN ITALYExamining the art and culture of the Etruscan people, wewill visit the great Etruscan collections in Rome, Florenceand Bologna and explore the medieval hill towns ofPerugia, Cortona and Orvieto. Our touring will encompassEtruscan necropolises and cities, including Volterra,Marzabotto, Chiusi, Sovana, Cerveteri and Tarquinia.Throughout our tour we will dine on regional specialtiesand enjoy the tranquil settings of these fascinating sites.JUNE 11 – 25, 2005 15 DAYSLed by Prof. Larissa Bonfante, New York University

CYPRUS, CRETE & SANTORINIThis popular tour examines the maritime civilizationslinking pre- and ancient Greek and Roman cultures withthe East. After a seven-day tour of Cyprus and a five-day exploration of Minoan Crete, we sail to Santorini tovisit Thera and the excavations at Akrotiri.The tour endsin Athens, from which we visit the fascinating ancientcities Mycenae and Tiryns.MAY 22 – JUNE 9, 2005 19 DAYSLed by Prof. Robert Stieglitz, Rutgers University

SICILY & SOUTHERN ITALYTouring includes the Byzantine and Norman monumentsof Palermo, the Roman Villa in Casale, unique for its 37rooms floored with exquisite mosaics, Phoenician Motyaand classical Segesta, Selinunte, Agrigento andSiracusa — plus, on the mainland, Paestum, Pompeii,Herculaneum and the incredible "Bronzes of Riace."MAY 28 – JUNE 13, 2005 17 DAYSLed by Dr. Robert Bianchi, Archaeologist

IRELANDOur new tour explores Ireland’s fascinating prehistoricand early Christian sites. Our touring will span thousandsof years as we study Neolithic and Bronze Agemonuments and artifacts, Celtic defensive systems andstone forts. Some of the tour highlights include prehistoricNewgrange and Knowth, the dramatic dry-stone fort, DunAenghus, on the Aran Island of Inishmore, the Ring ofKerry, fascinating Ogham Stones, the enigmatic carvedfigures on White Island and the museums in Dublin andBelfast. Traditional music and dance performances andspecial lectures by local archaeologists and historians willenhance this exciting tour.JUNE 30 – JULY 16, 2004 17 DAYSLed by Dr. Mattanyah Zohar, Hebrew University

PERUOur in-depth tour studies the vast Inca Empire that oncereached from Chile to Colombia. Touring begins withLima’s museums and includes visits to the Moche tombsof Sipan, Trujillo, the adobe city of Chan Chan and othercoastal sites, plus a flight over the Nazca Lines. Additionalhighlights include Caral, a newly excavated city believedto be 5,000 years old, a four-day visit to Cuzco and thesacred Urubamba Valley and two days at Machu Picchu.AUGUST 5 – 21, 2005 17 DAYSLed by Prof. Daniel H. Sandweiss, University of Maine

ADDITIONAL TOURSLibya, Egypt, Japan, Ethiopia, Maritime Turkey, Jordan,Mali, Prehistoric Caves of Spain & France...and more.

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 1:27 PM Page C2

american archaeology

american archaeology 1

a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 8 No. 4

COVER FEATURE20 LIFE UNDER SIEGE

BY ELAINE ROBBINSThe difficult tale of near constant conflict

is being told by the investigation of an 18th-century Spanish presidio in Texas.

12 MAKING PREHISTORIC MUSICBY JOANNE SHEEHY HOOVERResearch indicates that the Anasazi played an amazing variety of instruments, and that music played an important role in their culture.

27 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF PRESERVATIONBY KATHLEEN BRYANTThe Archaeological Conservancy has saved numerous sites since its modest beginnings.

33 RESISTING REMOVALBY CLIFF TERRY The federal government removed many Native Americans from their lands in the early 19th century. But some NativeAmericans resisted removal. Archaeologist Mark Schurr is discovering how they did it.

39 A PASSPORT TO THE PASTBY SUSAN G. HAUSERThroughout the country, volunteers are taking part in archaeological investigations as a result of the Forest Service’s Passport in Time program.

44 new acquisitionA SITE WITH UNUSUAL POTTERYBy preserving the Cary site, the Conservancy will allowresearchers the opportunity to examine its curious ceramics.

45 new acquisitionGALISTEO BASIN SITES DONATED TO THE CONSERVANCYNorthern New Mexico sites may have been part of an extensiveprehistoric network.

46 new acquisitionCHANGING NOTIONS OF MOUND BUILDINGThe Hedgepeth Mounds have contributed to a betterunderstanding of this ancient tradition.

47 new acquisitionWHAT BECAME OF THE MONONGAHELA?The Squirrel Hill site in western Pennsylvania could answerquestions regarding the fate of this culture.

48 point acquisitionMAJOR 16TH-CENTURY IROQUOIS VILLAGE PRESERVEDThe Conservancy acquires the Eaton site in western New York.

winter 2004-05

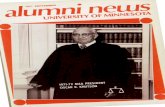

COVER: Though conflict was routine at Presidio San Sabá, the huge crack in the fort's northwest bastion is due to shoddy reconstruction work.Photograph by Timothy Murray

VIC

KI

MA

RIE

SIN

GE

RC

HA

RL

OT

TE

HIL

L C

OB

B

2 Lay of the Land

3 Letters

5 Events

7 In the NewsBooks Banned at NPS Stores • DNAFrom 65,000-Year-Old HairSequenced • Remarkable Mesa VerdeWater Management

50 Field Notes

52 Reviews

54 Expeditions

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:29 PM Page 1

MARK MICHEL, President

2 winter • 2004-05

Lay of the Land

ment and Jay’s was in business. Weknew we would be unsuccessful if wesought a solution based on govern-ment control of private property.What we needed was an American so-lution that worked within the contextof our experience. The answer wasobvious. If we acquired title to the pri-vately owned sites, we could protectthem. Everyone understands that.

After 25 years, we have nowcompleted almost 300 acquisitionprojects—purchases, bargain sales,bequests, and donations. More sitesare being protected by the many landtrusts around the country, but we re-main the only one that seeks andprotects archaeological sites. One by

DA

RR

EN

PO

OR

EIt seems like only yesterday that in-ventor/businessman Jay Last and I,with the support of many others,

got together to form The Archaeolog-ical Conservancy. We were growingmore alarmed by the day at the rapiddestruction of significant archaeolog-ical sites all around the country. Themore we investigated, the morealarmed we became. In the Missis-sippi Valley the main problem was bigagriculture with its big machines. Onthe East and West coasts it was urbansprawl that was paving over our her-itage. Everywhere it seemed therewere looters willing to destroy thepast for quick profit.

My background was in govern-

A Practical Solution to a Vexing Problem

one we are protecting this rich her-itage. In the years to come we expectto pick up the pace and protect evenmore. Thanks to the help of our loyalsupporters, the past 25 years havebeen challenging and rewarding. I ex-pect the next 25 to be even more so.

Archaeology learning adventures for all ages!Excavation andTravel programs in the Southwest and the world beyond.Cliff Dwellings & Rock Art:Hiking in Colorado’s Ute BackcountryAn in-depth exploration in Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park,in the shadow of Mesa Verde.April 24–30, 2005

Chaco Canyon & the Keresan WorldExplore one of the most influential sites in Southwestern history.May 15–21, 2005

Adult Research ProgramWeek-long summer dig programs

Mesa Verde Black-on-White Pottery WorkshopCreate your own replica vessel using tools and techniques of the ancients.June 19–25, 2005

For information and reservations or for a Free 2005 program catalog 1-800-422-8975/www.crowcanyon.org

AmA CCAC’s programs and admission practices are open to applicants of any race, color, nationality, or ethnic origin. CST 2059347-50

Near Mesa Verde in Southwestern CO

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:39 PM Page 2

Editor’s CornerIn the late 1700s, the southern end ofLake Michigan was populated by a num-ber of Native American communities. Dur-ing the early to mid-1800s the Potawatomitribe was subjected to the federal govern-ment’s “civilization” policy, which was de-signed to assimilate Native Americans intoEuro-American society.

By the 1820s the governmentdeemed its policy a failure in the East, andit opted to, by one means or another, re-locate the Potawatomi west of the Missis-sippi. This decision was promulgated bythe Chicago Treaty of 1833. By 1837, themajority of the Potawatomi were removedfrom the southern Lake Michigan area ei-ther voluntarily or forcibly.

It’s commonly thought that contactwith Euro-Americans, which resulted inassimilation or removal, led to the declineof Native culture. But recent evidence in-dicates some of these Native Americansmaintained their culture while selectivelyadopting Euro-American customs. One ofour feature articles, “Resisting Removal,”tells how adopting these customs proved,in at least a few cases, to be an effectiveway to thwart the government’s efforts torelocate them.

Historian Ben Secunda calls this prac-tice “adaptive resistance.” He believes thatthe Pokagan band, a Potawatomi groupthat resisted removal, resorted to adap-tive resistance in order to convince thegovernment that they, the Pokagan, wereindeed “civilized” and therefore should beallowed to remain on their land.

Through his investigations, archaeol-ogist Mark Schurr is revealing the variousstrategies, ranging from living in cabins topracticing Catholicism, that defined adap-tive resistance.

Letters

american archaeology 3

Sending Letters to American ArchaeologyAmerican Archaeology welcomesyour letters. Write to us at

5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 902, Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517, orsend us e-mail at [email protected]. We reserve the right to edit and publish letters

in the magazine’s Letters department as space permits. Please include your name, address andtelephone number wit all correspondence, including e-mail messages.

STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT, AND CIRCULATION Publication Title: American Archaeology. 2. PublicationNo.: 1093-8400. 3. Date of Filing: September 30, 2004. 4. Issue Frequency: Quarterly. 5. No. of Issues Published Annually: 4. 6. AnnualSubscription Price: $25.00. 7. Complete Mailing Address of Known Office of Publication: The Archaeological Conservancy, 5301 Central AvenueNE, Suite 902, Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517. 8. Complete Mailing Address of Headquarters or General Business Office of Publisher: same asNo. 7. 9. Names and Mailing Addresses of Publisher, Editor, and Managing Editor: Publisher—Mark Michel, address same as No. 7. Editor—Michael Bawaya, address same as No. 7. Managing Editor—N/A. 10. Owner: The Archaeological Conservancy, address same as No. 7. 11.Known Bondholders, Mortgagees, and Other Security Holders Owning or Holding 1 Percent or More of Total Amount of Bonds, Mortgages, orOther Securities: None. 12. Tax Status: Has Not Changed During Preceding 12 Months. 13. Publication Title: American Archaeology. 14. IssueDate for Circulation Data Below: Spring 2004. 15. Extent and Nature of Circulation: Average Number of Copies Each Issue During Preceding 12Months: (A) Total No. Copies (net press run): 32,475; (B) Paid and/or Requested Circulation: (1) Paid/Requested Outside-County MailSubscriptions Stated on Form 3541 (Include advertiser’s proof copies and exchange copies): 19,944; (2) Paid In-County Subscriptions (Includeadvertiser’s proof copies and exchange copies): 0; (3) Sales Through Dealers and Carriers, Street Vendors, Counter Sales, and Other Non-USPSPaid Distribution: 4,804; (4) Other Classes Mailed Through the USPS: 900. (C) Total Paid and/or Requested Circulation (Sum of 15B (1), (2), (3),and (4)): 25,648; (D) Free Distribution by Mail (Samples, complimentary, and other free): (1) Outside-County as Stated on Form 3541: 0; (2) In-County as Stated on Form 3541: 0; (3) Other Classes Mailed Through the USPS: 70; (E) Free Distribution Outside the Mail (Carriers or othermeans): 685; (F) Total Free Distribution (Sum of 15D and 15E): 755; (G) Total Distribution (Sum of 15C and 15F): 26,403; (H) Copies notDistributed: 6,073; (I) Total (Sum of 15G and 15H): 32,475. Percent Paid and/or Requested Circulation (15C/15G x 100): 97.14%. 15. Extentand Nature of Circulation: Number Copies of Single Issue Published Nearest to Filing Date: (A) Total No. Copies (net press run): 32,600; (B) Paidand/or Requested Circulation: (1) Paid/Requested Outside-County Mail Subscriptions Stated on Form 3541 (Include advertiser’s proof copiesand exchange copies): 19,216; (2) Paid In-County Subscriptions (Include advertiser’s proof copies and exchange copies): 0; (3) Sales ThroughDealers and Carriers, Street Vendors, Counter Sales, and Other Non-USPS Paid Distribution: 4,127; (4) Other Classes Mailed Through the USPS:1,470. (C) Total Paid and/or Requested Circulation (Sum of 15B (1), (2), (3), and (4)):24,813; (D) Free Distribution by Mail (Samples, compli-mentary, and other free): (1) Outside-County as Stated on Form 3541: 0; (2) In-County as Stated on Form 3541: 0; (3) Other Classes MailedThrough the USPS: 45; (E) Free Distribution Outside the Mail (Carriers or other means): 1,200; (F) Total Free Distribution (Sum of 15D and 15E):1,245; (G) Total Distribution (Sum of 15C and 15F): 26,058; (H) Copies not Distributed: 6,542; (I) Total (Sum of 15G and 15H): 32,600. PercentPaid and/or Requested Circulation (15C/15G x 100): 95.22%. 16. This Statement of Ownership will be printed in the Winter 2004 issue of thispublication. 17. I certify that all information furnished on this form is true and complete. Michael Bawaya, Editor.

Why Not a Bureau of Antiquities?Pursuant to the article“Budget ShortfallsThreaten Archaeology”in the Fall issue, theproblem was looming onthe horizon about the same timefederal and some state deficits weremade public a few years ago. Underthese circumstances it always seemsthat historical and archaeologicalpreservation must go on the wane.

This opens a window of oppor-tunity for vandals and looters, andscariest of all, the ventures of bigbusiness with schemes to bulldozeand develop large tracts of land forprofit.

The upshot of this becomes ev-ident in colleges where archaeologyis on the curriculum. It’s dismaying

that professors nowneed political skillsin order to obtainfunding/grants forsurveys, excava-

tions, salvage, lab work, cre-ation of computer-generated slidepresentations, etc. Then come theusual responsibilities—press con-ferences, scholarly meetings/dis-courses, and of course, teaching inthe classroom plus in the field.

Our government has a Bureauof Indian Affairs (a division of theDepartment of the Interior), butno Bureau of Antiquities. Some na-tions do. A debate on the pros andcons of this idea would be worth-while to any of us preservationists.

Daniel F. Drzewiecki

Toledo, Ohio

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 1:30 PM Page 3

American Archaeology (ISSN 1093-8400) is published quarterly by The Archaeological Conservancy, 5301 Central Avenue NE,Suite 902, Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517. Title registered U.S. Pat. and TM Office, © 2004 by TAC. Printed in the UnitedStates. Periodicals postage paid Albuquerque, NM, and additional mailing offices. Single copies are $3.95. A one-year mem-bership to the Conservancy is $25 and includes receipt of American Archaeology. Of the member’s dues, $6 is designated fora one-year magazine subscription. READERS: For new memberships, renewals, or change of address, write to The Archaeo-logical Conservancy, 5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 902, Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517, or call (505) 266-1540. For changesof address, include old and new addresses. Articles are published for educational purposes and do not necessarily reflect theviews of the Conservancy, its editorial board, or American Archaeology. Article proposals and artwork should be addressed tothe editor. No responsibility assumed for unsolicited material. All articles receive expert review. POSTMASTER: Send addresschanges to American Archaeology, The Archaeological Conservancy, 5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 902, Albuquerque, NM87108-1517; (505) 266-1540. All rights reserved.

American Archaeology does not accept advertising from dealers in archaeological artifacts or antiquities.

5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 902Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517 • (505) 266-1540www.americanarchaeology.org

Board o f D i rectorsVincas Steponaitis, North Carolina, CHAIRMAN

Cecil F. Antone, Arizona • Carol Condie, New Mexico

Janet Creighton, Washington • Janet EtsHokin, Illinois

Jerry EtsHokin, Illinois • W. James Judge, Colorado

Jay T. Last, California • Dorinda Oliver, New York

Rosamond Stanton, Montana • Dee Ann Story, Texas

Stewart L. Udall, New Mexico • Gordon Wilson, New Mexico

Regiona l Of f ices and D i rectorsJim Walker, Vice President, Southwest Region (505) 266-1540

5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 902 • Albuquerque, New Mexico 87108Tamara Stewart, Projects Coordinator • Steve Koczan, Site-Management Coordinator

Amy Espinoza-Ar, Field Representative

Paul Gardner, Vice President, Midwest Region (614) 267-11003620 N. High St. #207 • Columbus, Ohio 43214

Joe Navari, Field Representative

Alan Gruber, Vice President, Southeast Region (770) 975-43445997 Cedar Crest Road • Acworth, Georgia 30101

Jessica Crawford, Delta Field Representative

Gene Hurych, Western Region (916) 399-11931 Shoal Court #67 • Sacramento, California 95831

Andy Stout, Eastern Region, (301) 682-6359 717 N. Market St. • Frederick, MD 21701

Conser vancy Sta f fMark Michel, President • Tione Joseph, Business Manager

Lorna Thickett, Membership Director • Sarah Tiberi, Special Projects Director

Shelley Smith, Membership Assistant • Valerie Long, Administrative Assistant

Yvonne Woolfolk, Administrative Assistant

american archaeology ®

PUBLISHER: Mark MichelEDITOR: Michael Bawaya (505) 266-9668, [email protected]

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Tamara StewartART DIRECTOR: Vicki Marie Singer, [email protected]

Editorial Advisor y BoardScott Anfinson, Minnesota Historic Preservation

Ernie Boszhardt, Mississippi Valley Archaeological Center • Darrell Creel, University of Texas

Jonathan Damp, Zuni Cultural Resources • Richard Daugherty, Washington State University

Linda Derry, Alabama Historical Commission • Mark Esarey, Cahokia Mounds State Park

Kristen Gremillion, Ohio State University • Richard Jenkins, California Dept. of Forestry

Trinkle Jones, National Park Service • Linda Mayro, Pima County, Arizona

Jeff Mitchem, Arkansas Archaeological Survey • Douglas Perrelli, SUNY-Buffalo

Janet Rafferty, Mississippi State University • Judyth Reed, Bureau of Land Management

Ann Rogers, Oregon State University • Joe Saunders, University of Louisiana-Monroe

Donna Seifert, John Milner Associates • Art Spiess, Maine Historic Preservation

Richard Woodbury, University of Massachusetts • Don Wyckoff, University of Oklahoma

National Advertising OfficeMarcia Ulibarri, Advertising Representative

5301 Central Ave. NE, Suite 902, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87108;(505) 344-6018; Fax (505) 345-3430; [email protected]

he Archaeological Conservancy is the only national non-profit organization that identifies, ac-quires, and preserves the most

significant archaeological sites in theUnited States. Since its beginning in1980, the Conservancy has preservedmore than 295 sites across the nation,ranging in age from the earliest habita-tion sites in North America to a 19th-century frontier army post. We arebuilding a national system of archaeo-logical preserves to ensure the survivalof our irreplaceable cultural heritage.

Why Save Archaeological Sites? Theancient people of North America left vir-tually no written records of their cul-tures. Clues that might someday solvethe mysteries of prehistoric America arestill missing, and when a ruin is de-stroyed by looters, or leveled for a shop-ping center, precious information is lost.By permanently preserving endangeredruins, we make sure they will be here forfuture generations to study and enjoy.

How We Raise Funds: Funds for the Conservancy come from membershipdues, individual contributions, corpora-tions, and foundations. Gifts and be-quests of money, land, and securities arefully tax deductible under section 501(c)(3)of the Internal Revenue Code. Plannedgiving provides donors with substantialtax deductions and a variety of benefici-ary possibilities. For more information,call Mark Michel at (505) 266-1540.

The Role of the Magazine: AmericanArchaeology is the only popular maga-zine devoted to presenting the rich di-versity of archaeology in the Americas.The purpose of the magazine is to helpreaders appreciate and understand thearchaeological wonders available tothem, and to raise their awareness of thedestruction of our cultural heritage. Bysharing new discoveries, research, andactivities in an enjoyable and informa-tive way, we hope we can make learningabout ancient America as exciting as it is essential.

How to Say Hello: By mail:The Archaeological Conservancy, 5301 Central Avenue NE, Suite 902, Albuquerque, NM 87108-1517; by phone: (505) 266-1540; by e-mail: [email protected]; or visit our Web site: www.americanarchaeology.org

WELCOME TO THE ARCHAEOLOGIC AL

CONSERVANC Y!

t

4 winter • 2004-05

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 1:53 PM Page 4

Events

american archaeology 5

Museum exhibits • Tours • Festivals

Meetings • Education • Conferences

� NEW EXHIBITSMuseum of Indian Arts & CultureSanta Fe, N.M.—The traveling exhibition“Roads to the Past: Fifty Years of High-way Archaeology in New Mexico” cele-brates the history of highway archaeol-ogy. New Mexico initiated the nation’sfirst highway archaeology program in1954 when the Museum of New Mexico,the New Mexico Department of Trans-portation, and the Federal Highway Ad-ministration began a historic collabora-tion to document, study, and protectarchaeological sites within highwayright-of-ways across the state. The pro-gram became the model for similar pub-licly funded programs in other states,and the collaboration resulted in thedocumentation of over 10,000 years ofNew Mexico prehistory and history.(505) 476-1250, www.roadstothepast.org(Through January 2, 2005, then travelingto New Mexico State University in LasCruces January 15–March 15)

Canadian Museum of CivilizationGatineau, Quebec, Canada—“The Black-foot Way of Life: Nitsitapiisinni” tells thestory of the Blackfoot People from theirown perspective. Created by the Glen-bow Museum in Calgary, the exhibition

AM

ER

ICA

N M

US

EU

M O

F N

AT

UR

AL

HIS

TO

RY

ME

XIC

AN

FIN

E A

RT

S C

EN

TE

R M

US

EU

M

explores fundamental belief systems,traditional stories, sacred places,dances, and ceremonies throughvideos, soundtracks, and more than140 objects. The exhibit also examinesrelationships with governments andthe importance of ensuring the survivalof the Blackfoot legacy. 1-800-555-5621,www.civilization.ca (Through February13, 2005)

Guggenheim MuseumNew York, N.Y.—The spectacular newexhibition “The Aztec Empire” exam-ines the extraordinary civilization ofthe Aztecs through more than 440works drawn from public and privatecollections, including archaeologicalfinds of the last decade never beforeseen outside of Mexico. Organized bythe Guggenheim in collaboration withthe Consejo Nacional Para la Cultura yLas Artes and the Instituto Nacional deAntropología e Historia of Mexico, theexhibit is the most comprehensive sur-vey of the art and culture of the Aztecsever assembled, and the first major ex-hibition devoted to the subject in theU.S. in more than 20 years. (212) 423-3500, www.guggenheim.org (ThroughFebruary 13, 2005)

American Museum of Natural HistoryNew York, N.Y.—“Totems toTurquoise: Native NorthAmerican Jewelry Arts of theNorthwest and Southwest” is alandmark new exhibition ofmore than 500 examples ofstunning historic andcontemporary Native Americanjewelry and artifacts. The exhibitcelebrates the beauty, power,and symbolism of Native jewelryarts and includes more than100 objects from the museum’sextensive collection of NativeAmerican artifacts such astotem sculptures, masks, andphotographs and videos ofNorthwest and Southwestrituals that are stronglyconnected to cosmologicalbeliefs. (212) 769-5100,www.amnh.org (Through July2005)

Mexican Fine Arts Center MuseumChicago, Ill.—The extraordinary exhibition “Treasures of Ancient Veracruz: Magia de la risa y el juego” features 60 archaeological artifacts from Veracruz, the cradle of Mesoamericancivilization. Among the collection is a four-ton,3,000-year-old colossal stone Olmec head. All of the exhibit’s ancient figures demonstrate the fundamental human need to play. (312) 738-1503, www.mfacmchicago.org (Through February 6, 2005)

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:31 PM Page 5

Events

6 winter • 2004-05

Orlando Museum of ArtOrlando, Fla.—Due to popular de-mand, the museum is extending “An-cestors of the Incas: The Majesty ofAncient Peru, Selections and Giftsfrom the Dr. and Mrs. Solomon D.Klotz Collection.” Never before ex-hibited, the collection includesmore than 210 objects made by an-cient cultures of the Central Andesregion, including the Chavín, Nazca,Moche, Chimú, Huari, and Inca, be-tween 1400 B.C. and A.D. 1530. High-lights from the exhibit include ce-ramic portraits of Moche rulers, goldand silver royal vessels, delicate in-laid wooden boxes, colorful textiles,and stunning jewelry. (407) 896-4231,www.OMArt.org (Through June 2005)

North Dakota Heritage Center Bismarck, N. Dak.—“‘This GrandScene’...North Dakota from thePalette and Pen of George Catlin” of-fers five original paintings by GeorgeCatlin on loan from the SmithsonianAmerican Art Museum in Washing-ton, D.C. The quotation is fromCatlin’s notes and refers to the ex-hibit’s signature image, “Big Bend onthe Upper Missouri, 1900 MilesAbove St. Louis.” Catlin (1796–1872)painted this magnificent landscapeduring his 1832 journey up the Mis-souri River at a point southwest ofpresent-day New Town, NorthDakota. The Blue Buttes looming inthe background can be seen todayfrom the same perspective. (701)328-2666, www.DiscoverND.com/hist.(Through September 2005)

� CONFERENCES,LECTURES & FESTIVALSCelebrating Culture Sundays Winter ProgramThrough April 16, Alaska Native Heritage Cen-ter, Anchorage, Alaska. Watch Alaska Nativedances, learn about traditional art and lan-guage, listen to storytellers, and explore newexhibits and village sites. Themes vary eachweek. (800) 315-6608, www.alaskanative.net

15th Annual World Championship Hoop Dance Contest

February 5–6, Heard Museum, Phoenix, Ariz.Top Native hoop dancers from the UnitedStates and Canada compete for cash prizesand the World Champion title. (602) 251-0255,www.heard.org

Trail of the Lost Tribes Archaeology Speaker SeriesMonthly beginning February 12 at various loca-tions in Florida. The theme of this year’s seriesis “Stories Buried in the Ground: How Archae-ology Strengthens Florida’s Communities.” TheTrail of the Lost Tribes is a Florida non-profitnetwork of three heritage tour operators and21 public sites that promote a greater apprecia-tion of the ancient cultures of Florida. The se-ries is free and open to the public. ContactMarty Ardren at (941) 456-6128, [email protected] for the series schedule.

Arizona Archaeology & Heritage Awareness Month

March 1–31 at numerous locations throughoutthe state. Events, activities, demonstrations,exhibits, lectures, and tours provide informa-tion about Arizona’s archaeological, historical,and cultural resources. This year’s theme is“Respect Heritage.” Contact Ann Howard at(602) 542-7138, [email protected],www.azstateparks.com

PO

RT

LA

ND

AR

T M

US

EU

CO

LO

RA

DO

HIS

TO

RY

MU

SE

UM

Portland Art MuseumPortland, Ore.—The firstmajor museum exhibition tofocus specifically on the artand culture of the NativeAmericans who lived alongthe Columbia River from themouth of the Snake River tothe Pacific Ocean, “People ofthe River: Native Arts of theOregon Territory” includesstone sculpture, beadwork,and basketry. The exhibitionis drawn from the collectionsof the Portland Art Museum,the Smithsonian Institution,and the National Museum ofthe American Indian, as wellas from private collections. (503) 226-2811,www.portlandartmuseum.org(January 22–May 29, 2005)

Colorado History MuseumDenver, Colo.—“Ancient Voices: Stories ofColorado’s Distant Past” represents the firstphase of a new 6,500-square-foot AmericanIndian exhibition that explores the complexcultures of Colorado’s earliest inhabitants. Thesecond phase to follow in 2006 will examinehow these cultures changed as a result ofcontact with Europeans, among other influences.(303) 866-3682, www.coloradohistory.org(Opens January 28, 2005)

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:32 PM Page 6

american archaeology 7

The Pecos Conference, themajor group of Southwesternarchaeologists, has con-

demned the exclusion of selectedbooks from National Park Servicebookstores. At the annual meeting inBluff, Utah, on August 14, scholarscomplained about the exclusion ofbooks from Mesa Verde National Parkand Petroglyph National Monument.“This form of censorship is detrimen-tal to the dissemination of knowledgeand adversely impacts both (archaeo-logical) professionals and the inter-ested public,” stated the Conference’sresolution. “Interested readers areprohibited from reading examples ofthe best professional research.”

Most of the criticism was directedat Mesa Verde National Park, whichhas perhaps the busiest American ar-chaeology bookstore in the country.Mesa Verde bans books that identifythe ancient inhabitants of Mesa Verdeas “Anasazi,” including such popularworks as The Anasazi of Mesa Verde

and the Four Corners by William M.Ferguson and Understanding the

Anasazi of Mesa Verde and Hoven-

weep by David Grant Noble. Accord-ing to reliable sources at the park, Su-perintendent Larry T. Weise orderedthe books banned because of con-cerns expressed by some Pueblo peo-ple. Weise did not respond to numer-ous requests for comment.

The use of the word “Anasazi” todescribe the ancient Puebloan peo-ple of the Four Corners has becomecontroversial in recent years becauseof its Navajo origins, and Mesa Verdeand other parks are replacing it with“Ancestral Puebloan.” Both Navajosand Puebloans have claimed to be

descendants of the Anasazi in orderto control human remains from MesaVerde and influence the archaeologi-cal work on related sites, many ofwhich are on Navajo lands. Accord-ing to Mary A. Willie, a linguist at theUniversity of Arizona and a Navajo,Anasazi is “a conglomerate of twoseparate words meaning ‘non-Navajo’and ‘ancestor.’” A reasonable transla-tion of Anasazi would thus be“Puebloan ancestors,” ironically con-firming the Puebloans’ claim.

At Petroglyph National Monu-ment in Albuquerque, park officialshave barred books that contain pho-tographs of petroglyphs to whichPueblo people object, includinghuman figures, masks, and four-pointed stars. They also object tothe term “rock art,” because “it con-notes leisure time activity,” according

to Diane Souder, supervisory parkranger. Books that interpret themeaning of specific rock art symbolsare also unwanted at the park book-store. “It’s a terrible infringement onintellectual freedom,” according toPolly Schaafsma, whose classic rockart studies, Rock Art in New Mexico

and Warrior, Shield, and Star, areamong the scholarly tomes bannedfrom the park.

Because of the economic powerof the park bookstores, publishers inthe Southwest are struggling to con-form, but their efforts are hamperedby ambivalent policies. A spokesmanfor one of the biggest publishers in theregion said, “I’m not quite sure whatthe park superintendents are tryingto achieve, but I know I had better notsend them a book with “Anasazi” onthe cover.” —Mark Michel

Books Banned atNational Parks’BookstoresScholars accuse the parks of censorship.

VIC

KI

MA

RIE

SIN

GE

R These books are some of

the well-respected volumes

banned at Mesa Verde National Park

and Petroglyph National Monument.

NEWSin the

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:33 PM Page 7

8 winter • 2004-05

NEWSin the

Attention, Teotihuacán ShoppersWal-Mart opens a store near famous prehistoric ruins.

Bodega Aurrera, a division of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. opened itsstore near Teotihuacán despite

protests and a lawsuit. The store isvery near the 2,000-year-old ruins ofTeotihuacán, one of Mexico’s most fa-mous archaeological sites.

Though a number of Mexicans,from local merchants to artists, haveprotested the encroachment of big-box commerce on their cultural treas-ure, Wal-Mart officials said the storeposed no threat to the ruins and is infact welcomed by many people inthe community. According to WalfredCastro, manager of communicationsfor Bodega Aurrera, around 7 a.m. onNovember 4, the day the storeopened, there were roughly 300 peo-ple waiting to shop. He said therewere only a few people protesting.

According to earlier reports, alawsuit was filed with the federal At-torney General’s office to prevent thestore from opening. There were alsoallegations that an altar that was un-covered during the construction ofthe store’s parking lot was damaged.

“I know there are some lawsuits,but I don’t know who filed them,”said Alejandro Martinez Muriel, thedirector of archaeology for the Na-tional Institute of Anthropology andHistory (INAH). “Nothing was dam-aged during construction,” he added.

Martinez Muriel described theconstruction of the store as “more apolitical problem” than an archaeo-logical problem. He said the store ismore than a mile away from the ruinsin a commercial area that includes ahotel, auto dealership, and other

businesses. INAH reviewed the ar-chaeological and architectural impli-cations of the construction projectand found them to be satisfactoryand that no laws have been violated.

At one point, INAH stopped con-struction for four days to assess thepossible threat to buried archaeologi-cal resources. Martinez Muriel saidINAH conducted a ground-penetrat-ing radar survey, dug approximately120 test units, and extensively exca-vated three areas, one of which waswhere the altar was discovered. Dur-ing this time they found no further ev-idence of archaeological resources.Once construction resumed, INAHhad archaeologists on the site moni-toring the work. Martinez Muriel saidthe altar was documented and care-

fully reburied where it was found. Thearea is now covered with grass and isno longer part of the parking lot.

Wal-Mart officials said they werenot familiar with any lawsuits thatwere filed concerning the store.“They couldn’t sue our company be-cause everything was legal,” Castrosaid. The governor of the State ofMexico and the International Councilon Monuments and Sites, an organi-zation based in Paris, also reviewedthe plans for the store.

“It’s going to be a Mexican-typestore employing Mexican people,”said Bill Wertz, a Wal-Mart spokesper-son. He said the store would employabout 150 people. Wal-Mart is thelargest private employer in Mexico.

—Michael Bawaya

The opening of a Wal-Mart store near the magnificent ruins of Teotihuacán has created controversy.

MA

RK

MIC

HE

L

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:33 PM Page 8

american archaeology 9

NEWSin the

A team of researchers recentlysequenced mitochondrial DNAfrom 12 hair samples, the old-

est of which is at least 65,000 yearsold. This achievement could playan important role in informing ar-chaeologists about the peopling ofthe New World.

The researchers, led by TomGilbert of the University of Arizona,sequenced shafts of hair from bison,as well as horses and humans. Ra-diocarbon dating of the bison hairsamples indicated they are roughly65,000 years old. Gilbert said thesesamples could actually be older, asradiocarbon testing can’t determinedates beyond this age. The humanhairs, which are thought to be sev-eral hundred years old, are theyoungest of the samples.

The research shows “how farback you can push DNA evidence,”said archaeologist Robson Bonnich-sen, the director of the Center forthe Study of the First Americans atTexas A&M University. Several yearsago Bonnichsen sequenced anddated hair samples from an 11,000-year-old sheep. “Hair is the artifactthat humans produce most of intheir lifetimes,” he added, explainingthat people shed a lot of hair. “It’s anenormously interesting material forarchaeology.” Ancient DNA analysisof hair could inform researchersabout the movement of peoplethrough time and space. Hair, Bon-nichsen said, can yield informationabout race, gender, and even diet.

Hair strands are sometimesfound at ancient sites, but they were

DNA From 65,000-Year-Old Hair SequencedThe analysis of ancient bison hair has important implications for archaeological research.

Anew obsidian hydration dating technique was recentlyused in the analysis of artifacts made of obsidian, a vol-canic glass, from the Hopewell site and Mound City in

central Ohio. Using secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS)to measure the amount of water, a team of researchers, led byarchaeologist Christopher Stevenson of the Virginia Depart-ment of Historic Resources, concluded that artifacts fromthese sites are approximately 1,400 to 2,200 years old. Thesedates were corroborated by recent radiocarbon testing of as-sociated materials.

Obsidian hydration has been used to date obsidian arti-facts for many years. When an artifact is fashioned from rawobsidian, the outer layers are chipped away, exposing the newsurface to the air. Once the new surface is exposed, water be-gins to diffuse into the glass from the air, or from the soil inthe case of buried material. By measuring the extent of thisdiffusion, an estimate of the age of the artifact can be made.

The traditional approach is to take a thin cross-section ofthe artifact and measure the thickness of the hydrated layerwith an optical microscope. The SIMS technique uses an ionbeam to drill a tiny hole in the artifact that allows researchersto more accurately measure the hydrated layer.

Hopewell Artifacts Dated By New TechniqueImprovement could mean more accurate obsidian artifact dating.

thought to be of little analyticalvalue because they contain tinyamounts of DNA. “Right now, every-one is using bone and tooth,”Gilbert said, referring to the type ofremains that are most often ana-lyzed for DNA.

Extracting DNA from bone andtooth requires drilling a small holein them, which damages the sam-ple. “It’s much less destructive tak-ing a small hair sample,” he said.“We’re literally using a single hairshaft,” and that shaft is less than aninch long.

Though DNA analysis is prom-ising, it’s limited by the numberand quality of the samples. DNA is achemical that degrades, especiallyin warm conditions.

—Michael Bawaya

“It’s clear it’s a better way to go than the old way,”Steven Novak, a member of the research team, said ofthe SIMS technique. “As time goes on it will be usedmore and more.” —Michael Bawaya

Researcher Steve Novak operates an ion mass spectrometry device.

BIL

L H

AR

RIN

GT

ON

/EV

AN

S E

AS

T

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/17/04 2:33 PM Page 9

10 winter • 2004-05

NEWSin the

T his fall, the American Society of Civil Engineersdesignated the four prehistoric reservoirs atMesa Verde National Park in southwestern Col-

orado as Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks inrecognition of their remarkable engineering. Investiga-tions of the Mesa Verde water management features bymultidisciplinary teams of researchers have identifiedfour large reservoirs, feeder and irrigation ditches,check dam systems, terraces, and stone alignmentsthat were built and used between A.D. 750 and 1180 byinhabitants of the valley and mesa-top dwellings.

“The Ancestral Puebloans that populated the river-less mesa top conquered the impossible by creating awater system to sustain their domestic and agriculturalneeds,” said Patricia Galloway, president of the AmericanSociety of Civil Engineers. “They are truly civil engineer-ing pioneers.”

While earlier researchers recognized the large de-pression on Chapin Mesa, formerly known as MummyLake, as a prehistoric reservoir, later investigators pro-posed that the feature may have served as a dancearena or other type of group assembly feature. Ken-neth Wright of Wright Paleohydrological Institute andhis colleagues recently conducted extensive multidisci-plinary investigations of this and other water controlfeatures on the mesa, substantiating the feature’s func-tion as a reservoir and putting to rest the long-standingdebate. As a result, the feature has been renamed FarView Reservoir.

Morefield Reservoir, the largest and oldest of thefour Mesa Verde reservoirs, was also thought to be a cer-emonial dance platform or ancient terrace remnant untilWright’s research proved different. “Although the fea-tures had been studied during the 1960s and 1970s,there was not scientific agreement on their original func-tion because there was no identifiable proven water sup-ply to furnish water for storage,” said Wright. “As a result,

Prehistoric Reservoirs Designated Civil Engineering Landmark Research sheds light on Mesa Verde water management systems.

in 1996 I sought and received a permit to excavate the reser-voir. Once the reservoir trench was opened, there was no fur-ther doubt that it was a water storage facility.”

Morefield Reservoir was built as early as A.D. 750 andheld up to 120,000 gallons of water. The spoil from centuriesof routine dredging of the reservoir formed a mound 16 feettall and 200 feet in diameter. Fifty years later, a similar reser-voir was built in Prater Canyon. It was discovered followingthe Bircher Fire in 2000. From A.D. 950 to 1100, Far View andSagebrush reservoirs provided water for the Mesa Verdepeple when their population was at its peak. “The AncestralPuebloans knew more about water harvesting than modernengineers,” said Wright. “They collected and stored waterwhere modern engineers would say there was none.”

—Tamara Stewart

KE

NN

ET

H W

RIG

HT

The Morefield Reservoir mound of Mesa Verde was trenched in 1997. The

trench exposed the centuries of sediment deposition that contained

potsherds and tools of the Pueblo I and II periods.

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/23/04 11:15 AM Page 10

Tracking PrehistoricHuman Migrationin MesoamericaStrontium isotope analysis provides a tool for researchers.

NEWSin the

american archaeology 11

Researchers are learning aboutprehistoric human migrationin Mesoamerica by using stron-

tium isotope analysis. Researchersfrom the University of Florida andRutgers University recently publishedthe results of strontium isotope analy-sis at 216 sites throughout the Mayaregion in the Journal of Archaeologi-

cal Science. Their study representsthe first attempt to assemble a com-prehensive strontium isotope data-base in the Maya region.

Strontium isotope ratios can bemeasured in the ground from whichhumans obtained food and water.Strontium is a metallic element that’sabsorbed into bones and teeth.Analysis of teeth is especially reveal-ing, as the intake of strontium frombirth to about age four forms a den-tal signature that remains unchangedthrough life. By matching the stron-tium ratios found in an individual’steeth with those of a geographicarea, researchers can identify the in-dividual’s birthplace.

Two strontium isotopes, strontium87 and 86, are relatively abundant, andtheir ratios vary slightly across theMaya region. Because the two isotopeshave different masses, their ratio ingeological, biological, or water sam-ples can be precisely measured.

The researchers sought to deter-mine whether the sources of dietarystrontium in humans do indeed re-flect the strontium ratios of exposedbedrock, and to see if the ranges ofratio values are sufficiently distinctamong the principal Maya geocul-tural areas to infer past migration.

“We discovered that the stron-

VIC

KI

MA

RIE

SIN

GE

R

tium isotopic signature of plants andwater in each subregion of the Mayaarea generally reflected the ratio inthe local soils and rock, and that theratios for different subregions couldoften be distinguished,” said MarkBrenner, one of the researchers. “Wewere not surprised to find a latitudi-nal change in strontium ratio pro-ceeding from the north coast of Yu-catan to the southern lowlands ofPetén, Guatemala, because surfacelimestone in the north is geologicallyyoung, whereas exposed limestonein the south is much older.”

“Future studies can use the stron-tium isotope approach to test whetherancient leaders were locals or out-siders, and can be used to evaluatewhether mass migrations may have oc-curred in response to inferred climatechanges, environmental disasters, or

social upheavals,” Brenner said.Strontium analysis of skeletal re-

mains excavated at Teotihucán in theValley of Mexico was done by T. Dou-glas Price of the University of Wiscon-sin and several colleagues, revealingthat immigrants probably played alarge role in sustaining the massivecity’s rapid growth. Based on archi-tecture, artifacts, and burial patterns,two residential areas within the cityappear to be distinctive ethnic com-pounds. Indeed, individuals buriedwithin those areas exhibit large varia-tions in strontium isotope ratios oftooth enamel, but little differenceamong bone samples, indicating thata number of the individuals migratedto the city after childhood. The tech-nique has been applied to the Ameri-can Southwest and Europe as well.

—Tamara Stewart

Tourists view the ruins of Chichén Itzá from the top of the pyramid El Castillo. Strontium isotope

analysis could help researchers determine how Maya cities like Chichén Itzá were populated.

AA Win 04-05 pg C1-12 11/23/04 2:14 AM Page 11

12 winter • 2004-05

The world of the Anasazi has been a major researcharea for archaeologists of the Southwest, who haveexamined the nature and evolution of these prehis-toric people from many angles. Emily Brown, a Na-tional Park Service archaeologist stationed in Santa

Fe, New Mexico, is taking a fresh approach to theAnasazi: she is studying the instruments that were usedto make music.

Music would seem the most evanescent of sources,vanishing as soon as it is produced. If a thousand yearsfrom now, a cache of Jimi Hendrix guitars or the remains ofYo Yo Ma’s cello were uncovered, what would archaeolo-gists infer? Would they see the instruments simply as a toolfor entertainment? Or would they be able to trace the po-litical and social impact of Hendrix and his guitars within anemergent counter-culture in the Vietnam War period? Orthe social and cultural influences across half the world asYo Yo Ma combined his cello with instruments and musi-cians from lands along the ancient Silk Road?

For Brown, combining archaeology and music was analmost inevitable life path. Her bachelor’s degree is a dou-ble major in music and anthropology, and her master’sand doctorate degrees are in archaeology. She classifiesherself as an archaeomusicologist, a subdiscipline so re-cent that the term is unfamiliar even to many within thefield. As David Hurst Thomas, curator of anthropology atNew York’s American Museum of Natural History, com-mented, “It’s certainly not a term that’s on the lips ofevery archaeologist.” Brown finds music a natural gatewayinto the world of the past, pointing out that no society hasever been found that did not have music. Instruments area primary source of music, which she views as a frequentcomponent of ritual, which in turn was used for social andpolitical ends.

She has studied 1,300 Anasazi instruments from thegreater Four Corners area where the Anasazi once lived.The time period of her research goes from A.D. 200, thefirst period from which Brown was able to find instru-

CH

AR

LO

TT

E H

ILL

CO

BB

An archaeologist believes

that music played an

important role in Anasazi

culture. In addition to shedding

light on the Anasazi, her

research could pioneer a new

method of examining the past.By Joanne Sheehy Hoover

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:50 PM Page 12

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AM

NH

, C

AT

. #

H/1

25

57

american archaeology 13

ments, to 1540, when the Spanish first entered the region.The majority of these instruments are found in museumcollections on the East Coast and in the Southwest, andsome are in National Park Service collections. Thoughthe items from more recent excavations havebetter documentation, she found thatthose recovered from earlier excava-tions and now housed at the Smith-sonian in Washington, D.C., theAmerican Museum of Natural His-tory in New York, and the twoPeabody Museums in Bostonhad the more unusual instru-ments.

What she discovered is a sur-prising range and variety of bothmaterials used and the kind ofsounds that could be produced.Falling into the basic percussion andwind categories, the instruments yield asonic picture that in its own way is asvaried as the modern orchestral worldof strings, winds, and percussion. Ar-chaeologist Stephen Lekson, an author-ity on the Anasazi culture, was surprisedby the great number of instrumentsthat Brown studied.

“I’m not aware of anyone who’s done a comprehen-

sive study like this before,” said Lekson, who first heard ofBrown’s work through a paper she delivered this pastsummer at the Pecos Conference, an annual event that fo-

cuses on Southwest archaeology. “You can learn a lot bylooking at these kind of artifacts. There’s

enough of them, they’re distributed acrossenough space and enough time that you

can wind up saying some pretty inter-esting things.” Her research, he noted,examines “classes of evidence thatwe didn’t customarily or convention-ally consider.”

Building on the four-partmethodology for the analysis ofmusical instruments developed byDale Olsen, an ethnomusicologist at

Florida State University, Brown firstmeasured the instruments, noted any

features of form or decoration, andchecked museum records or otherpublications for information. Setting upa computer database, she developed ty-pologies and noted where and whenthe instruments were used. The secondstep dealt with iconology. She exam-ined anything depicted on the objectsthemselves as well as musicians por-

trayed in rock art, kiva murals, and on pottery. The rock

This fragment of a decorated wooden flute was found in the ruin of Pueblo Bonito at Chaco Canyon in northwest New Mexico. It was in a room that was

thought to be used for storage of ceremonial items. With its flared end, it is similar to flutes used by the Hopi.

Rattles made by stringing hoofs together and attaching a wooden handle were first used at least as early as A.D. 500, and they were played by members of

Zuni Pueblo as late as the 1890s. Found in 1895, this object is in good condition. Sinew, yucca, and human hair were among the materials used to make it.

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

NP

S /

WA

CC

CA

T.

#C

AC

H8

11

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AM

NH

, C

AT

. #

H/4

56

2

Great care was taken in the decoration of this

gourd rattle from Canyon de Chelly in northeast

Arizona. The design was created by painstakingly

peeling back the outer skin of the gourd to

expose the lighter color underneath.

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 3:01 PM Page 13

MA

XW

EL

L M

US

EU

M

14 winter • 2004-05

art, for example, included a number of male flute playerswho were engaged in copulation with female figures, sug-gesting a connection between music and fertility.

The third and fourth steps involved researching his-torical and ethnographic sources. These included Spanishaccounts of Puebloan music that also yielded informationon the places, such as plazas and kivas, where ritual per-formances took place. Then she added a fifth step of ana-lyzing the material in archaeological terms: looking at dis-tribution, provenience, and contextual information foreach site. Architectural features of a site were of particularinterest since they might offer clues about where and howthe instruments were used.

She did not actually play any of the instruments. “Cu-rators would frown on the hot, moist air and vibrationsgoing into objects in their care,” said Brown in referenceto the wind instruments she studied. But she found that agreat deal of sound information was gained simply by gen-tly examining them, turning over small bells, for example,or handling a kiva bell made out of a resonant volcanicrock called phonolite.

Her inventory conjures up a vivid sound world that in-cludes flutes and whistles made of wood, reed, and a widevariety of bones from birds like turkey, Canada geese,whistling swans, and eagles, and animals like fox and bob-cat. Bells ranged from the small copper and clay variety tothe larger kiva bells. Rattles were divided up into twobroad categories—tinklers and rattlers. Tinklers referredto objects that could be strung on a string, like seashells,

walnut shells, pieces of petrified wood, or hooves. Rattlersreferred to cases with things inside to shake, like gourdswith dried seeds and leather cases stretched aroundwooden frames filled with seeds or small stones. She alsostudied delicate, small-scale rattles made of cocoons and

Clay bells such as this one are rarely found at sites other than Pecos

Pueblo (where this bell was found), near Santa Fe, and Awatovi, a Hopi site

near the Hopi Mesas in northwestern Arizona. However, they are fairly

common at these two sites.

An examination of this

walnut rattle reveals the

ingenuity of its maker.

Each yucca cord was

carefully twined, then

threaded through a native

Arizona walnut shell. The

ends were then bound

together in such a way as

to make a handle. There

are many rattles made by

suspending hoofs or other

objects in a similar way,

but Brown found only two

walnut rattles in the

collections she researched.

Both came from Canyon

de Chelly.

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

NP

S /

W

AC

C C

AT

. #

CA

CH

81

1

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:51 PM Page 14

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AM

NH

CA

T.

#2

9.1

/23

19

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AS

M,

CA

T.

# 1

59

91

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AS

M,

CA

T.

# G

P 4

24

3

american archaeology 15

the tube-shaped nests of trapdoor spiders that could befilled with little seeds. Rasps, two pieces of wood or bone,one with a serrated edge, which yielded a percussivesound when rubbed together, were also examined.

Curiously, her inventory does not include drums,which are ubiquitous in Pueblo culture today. Are they theas yet unseen sound elephant that some feel must havebeen there? Brown answered the question with more ques-tions. “Is there a long tradition and we archaeologists justaren’t seeing it? Or are they really a much more modern in-vention or introduction, and, if so, how did that happen?”

Apart from foot drums, the term given to trenchesfound in kivas that were covered with a board that wasdanced on, no drums have ever been found in the prehis-toric Southwest. Brown has checked various sources inthe archaeological record including rock art. She hasfound many images of the little flute player popularlyknown as Kokopelli, and depictions of people carrying rat-tles and wearing shell tinklers, but she has never found animage of a drum.

Having documented and classified this large body ofinstruments, Brown then applied that data to questions ofauthority and leadership among the Anasazi. Would the in-struments and the settings in which they were used yieldpossible connections between music and ritual, politicaland social life?

The earliest instruments, wood and reed flutes of theBasketmaker period (A.D. 400–700), were few in numberand most of them came from small village sites in north-eastern Arizona. The sites contained rock art depictingflute players with shamanic characteristics like flying orwobbly legs. She concluded that a few shamans within thesociety probably used the instruments.

Brown found less than a dozen instruments dating tothe Pueblo I period (A.D. 700–900). These instrumentswere found primarily in the Mesa Verde region in south-western Colorado. It was a period when people were set-tling down, becoming more agricultural, and it marked thefirst appearance of foot drums. Brown theorized that inthe process of settling down, questions of land tenure andaccess to resources would arise and that it might be usefulto have connections to the land in your mythology and rit-uals, of which dancing was a part. In the 1980s archaeolo-gist Richard Wilshusen interpreted foot drums as repre-senting sipapus, the holes where Pueblo ancestorsemerged into this world according to the origin myth.There is also ethnographic evidence that dancing on thefoot drums was viewed as a way of communicating withthe underworld.

The Pueblo II period (A.D. 900–1150) marks a fluores-cence of Anasazi culture, epitomized by the civilization atChaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico. Designated aUNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, Chaco containsmany spectacular sites, some with vast plazas and greatkivas. According to archaeological interpretations, Anasazi

Complete turtle shells, like the one used to make this rattle, are rare finds

for archaeologists due to their fragility. Deer or antelope hoofs were strung

along the shell’s exterior to create sound.

The handle of this unique basketry ladle is hollow and contains small

pebbles or seeds that make a rattling noise when it is moved.

Based on depictions in kiva murals, archaeologists know shell tinklers such

as these were sewn onto clothing. The shells made a pleasing sound at the

slightest movement of the wearer.

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:52 PM Page 15

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AN

MH

, C

AT

. #

29

.0/8

23

7M

ES

A V

ER

DE

NA

TIO

NA

L P

AR

K C

AT

. #

5M

V1

45

2

16 winter • 2004-05

social organization and relationships became more com-plicated, a development that Brown finds reflected in a flu-orescence of new instruments. Their sonic power or visualappeal led her to theorize that they were used for publicritual spectacle as well as in the kivas.

Some, like conch shell trumpets and small copperbells and shell tinklers imported on trade routes from Mex-ico, were valued items. Based on the volume of modernshell trumpets played by Tibetans, Pacific Islanders, andother cultures, Brown surmises the shell trumpets couldhave sent loud waves of sound across the plazas, while thecopper bells, sometimes found attached to beads, and shelltinklers were eye-catching musical additions to costumes.

There were also elaborate versions of earlier instru-ments, notably the wooden flutes. At Chaco they are dec-orated with paint and carving instead of feathers like someof the Basketmaker flutes, and one example was morethan three feet long. They were visually arresting, both intheir size and their decorations, such as carved animalsand painted geometric designs, though their pitcheswould have been low and relatively quiet.

Brown also theorizes that these flutes could have beenused to enrich the spectacle and also to invoke the past andthus add the weight of tradition to the Chaco rituals. Footdrums, which the Anasazi continued to use, could haveserved a similar purpose.

Brown noted that the Chaco burials in which instru-ments were found contained more grave goods than anyother burials uncovered in the Southwest. They included“thousands and thousands of pieces of turquoise, lots ofpottery, and carved wood staffs that modern Hopi recog-nize as being ritual objects,” she said. Brown posits a closecorrelation between the people buried with so many lux-ury and ritual items and the music, which might have beeneither for secular or ritual performance. “Chaco was a lotabout spectacle,” explained Brown. “It’s the people at thetop who are putting these things on and they have eitherthe power or the means to. And that’s what these [instru-ments] are being used for.”

Early in the Pueblo III period (A.D. 1150–1300) Chaco

The rectangular, stone-lined vault visible in the floor of this ceremonial chamber once had a covering of wooden planks, which made for a foot drum.

Researchers studying the Southwestern Pueblo peoples early in the 20th century watched them dance on similar “drums” in ceremonies meant to communicate

with their ancestors. Brown was surprised to discover that these are the only kinds of drums archaeologists have discovered in the Southwest so far.

The hollow in the bottom of this mug held small pellets of clay that made it

rattle when someone drank from it.

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:52 PM Page 16

MA

XW

EL

L M

US

EU

M

american archaeology 17

and its outliers were abandoned due to an apparent ex-tended drought. The disruption is reflected in the instru-ments. Wooden flutes disappear altogether and shell trum-pets and copper bells vanish from Chaco and places whereChacoan influence spread. Brown theorizes that since theseinstruments had been significant components of ritual spec-tacle at Chaco, their absence points to a rejection of theChacoan ideology. In her view, “Whatever rituals and ideol-ogy were in place at Chaco ultimately didn’t meet people’sneeds during the great drought.”

Commenting on these assumptions, Lekson noted,“I, and many archaeologists, consider Chaco to be a majorturning point in Pueblo history, and if that’s reflected inmusic and the way music is produced—that’s very in-triguing.”

By A.D. 1400 the Anasazi had regrouped along the Rio

Grande Valley, western New Mexico, and eastern Arizona,where their modern Pueblo descendants live. Brown theo-rizes that a surge in the number and types of instrumentsand the expanded variety of materials from which theywere made reflect the rise of a new ideology. Rasps, claybells, kiva bells, eagle bone flutes, and certain kinds of rat-tles and whistles appear for the first time. Some instru-ments, like rattles and tinklers, would have been easy tomake and play. Others, like eagle bone flutes, were moredifficult to play or construct, or the materials they weremade from were hard to obtain. Elaborate kiva murals withpeople carrying instruments offered additional indicationsof an efflorescence of ceremony.

Brown also noted architectural differences betweenthe Pueblo IV pueblos and those from previous times, par-ticularly a shift in the kivas, which overall are much re-

Mimbres vessels are known for their detailed depictions of humans, animals, and otherworldly creatures. This drawing (left) based on a Mimbres vessel shows

a man swinging a decorated triangular object that is probably a bullroarer. Bullroarers (right) were a relatively late invention for the Anasazi. A string was

placed through this instrument’s hole and it was swung to make sounds.

The Anasazi made bone whistles and flutes. Bone flutes, such as the one shown at the top of the photograph, were not particularly common until A.D. 1250.

Most of them were made from the wing bones of eagles. The smaller whistles were made from the bones of fowl ranging from eagles to turkeys. Brown found

more bone whistles than any other type of instrument.

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AM

NH

, C

AT

. #

29

.0/2

47

8

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:53 PM Page 17

MA

XW

EL

L M

US

EU

M

18 winter • 2004-05

duced in number. Whereas before communities werecomposed of roomblocks that were near, and thereforeseemed to be associated with, both great and small kivas,there are now big, rectangular plazas surrounded by largeroomblocks that don’t appear to be associated with kivas.It was an arrangement where certain very public dancestook place in the large plazas and a tradition of secrecysurrounded the most sacred knowledge of rituals per-formed in kivas.

Brown theorizes that community leaders used kiva fra-ternities with specialized ritual knowledge, including use ofcertain instruments, as a means of organizing and knittingtogether these large communities. In her view, these lead-

ers “acquired and maintained their personal, social, andpolitical power by keeping their sacred knowledge very se-cret and by having, for example, only certain people beable to play these eagle bone flutes. Whereas some of theseother rattles and things that are pretty easy to make andplay—many more people could use them in the publicdances in the plazas.”

Brown’s work has not yet, in her words, been “broad-cast too widely.” Few archaeologists, she added, “feelcomfortable dealing with the subject matter of music justbecause they don’t know much about it.” She views hertheoretical connections between music, ritual, and socialand political leadership as her most significant contribu-

(Left) Conch shells are used for trumpets in many parts of the world. The Anasazi’s version of this instrument was unusual in that they added mouthpieces

to the ends. What the shell trumpets lacked in melodic variety, they made up for in volume. The sound likely echoed off the stone walls of Pueblo Bonito

at Chaco Canyon, where this trumpet was found. (Right) This is the mouthpiece of a shell trumpet that has been decorated with a mosaic of turquoise.

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

AM

NH

CA

T.

# H

/12

78

7

EM

ILY

BR

OW

N /

CA

SA

GR

AN

DE

RU

INS

NA

TIO

NA

L M

ON

UM

EN

T /

WA

CC

CA

T.

#C

AC

H8

11

Rasps such as these were played by scraping a stick across the ridges carved into the bones. Rasps were usually made from the shoulder blades of deer and

antelope, like the large one at the top of this photograph, but they were also made from ribs and long bones. Brown examined one made from the leg of a dog.

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:54 PM Page 18

ME

SA

VE

RD

E N

AT

ION

AL

PA

RK

CA

T.

#6

83

5

american archaeology 19

tion to the field of archaeomusicology. Though the fieldemerged in the mid-1980s, most of the studies, she ex-plained, were done in Europe, with little in the Americasother than some research on the Incas, Aztec, and Mayacultures and a few other groups. “Apart from empires orcultures that have some sort of written record that youcan relate this stuff to, it’s been viewed as a dicier propo-sition. People haven’t come up with a theory that linksthe performance or experience of music in the past toanything else, so that’s what I’ve tried to do.”

Though disagreements may arise with Brown’sanalysis, she is clearly expanding the archaeological tool-box. The scope and thoroughness of her research hasproduced a body of new data for the field and helpedput the infant discipline she champions on solid ground.

“To have somebody who has a feel for archaeology,literally from the ground up, a feel for musicology theway she does as a performance musician—I can’t imag-ine that’s happened before. The third component isher expertise with the museum collections because shedid come and study our collection here in New York,”said Thomas. “I really think she’s blazing new groundhere.”

“Certainly no one has done anything like this proj-ect in the U.S. or, as far as I know, anywhere else ei-ther,” said Nan Rothschild, a Columbia University ar-chaeologist who knows Brown’s work. “It provides anew dimension to the archaeological understanding ofthe prehispanic Southwest.”

Brown also hopes that her work will benefit thepublic at large. She foresees that her research couldflesh out displays of prehistoric instruments in placeslike visitor centers and give a more vivid sense of

Anasazi life. She would like to break through the si-lence of the past, make its music come alive in theimagination. Or, as Shakespeare put it, give to “airynothing a local habitation and a name.”

JOANNE SHEEHY HOOVER has been a music lecturer for the SmithsonianAssociates and a music critic for The Washington Post and the AlbuquerqueJournal.

Brown measures a bone whistle with a pair of calipers.

JE

FF

BR

OW

N

These hoof rattles could be tied around the ankles of a dancer. This pair, which was found together, is on display at Mesa Verde National Park.

Instruments p12-19 11/17/04 2:54 PM Page 19

VIC

KI

MA

RIE

SIN

GE

R

20 winter • 2004-05

Abreeze riffles the emerald sur-face of the San Sabá River inMenard,Texas, a small town ofshuttered Main Street store-fronts and roadside cafes.

Roughly 250 years ago the Spaniardscame here to pursue their contradictorygoals of bringing guns and God to thefrontier. Evidence of that conflicted mis-sion is turning up on a golf course on theoutskirts of town, where Texas Tech Uni-versity archaeologists Tamra Walter andGrant Hall are excavating Real Presidiode San Sabá, the largest Spanish-erafrontier fort in Texas.They hope to dis-cover how 100 Spanish soldiers and theirwives and children—a total of 300 to 600people—survived here at the northern-most edge of the Texas frontier. Confined

Life Under

Siege

to a stone fort about the size of a base-ball field, they formed “a lonely island ina sea of Indian hostility,” according tohistorian Robert S. Weddle, author ofThe San Sabá Mission.

The Spanish had already been in Texasfor 50 years by the time the presidio wasfounded in 1757 along with Mission SantaCruz de San Sabá, the mission it wascharged with protecting. But this far-flungoutpost was 100 miles—a five to seven-day journey—from the established net-work of Spanish missions in San Antonio.“The mission was the primary reason forthem being down in this country,” saidHall. “There was a group of Franciscanpriests who for a long time had beenwanting to Christianize the Lipan Apachewho lived in this area of central Texas.”

San Saba p20-26 11/17/04 3:10 PM Page 20

american archaeology 21

While some Spaniards had wanted tobuild the mission 70 miles to the east,where gold and silver had been found inthe Llano Uplift, in the end the priestswon out.

Like the best-laid plans, though, theSpaniards’ dreams of converting theApache quickly gave way to a harsher re-ality.The Lipan Apache feigned interest inthe mission but never really took thepriests’ outreach efforts seriously. Mean-while, the Apaches’ many enemies—in-cluding the Comanche and other north-ern tribes the Spanish called Norteños—so resented the Spaniards’ friendship withthe Apache that they formed their own al-liance.Ten months after the mission wasestablished, a force of 2,000 Norteños at-

tacked, killing eight Spaniards and burningthe mission to the ground.The survivorsfled to the presidio, where they desper-ately held on for 10 to 12 years.

“Because of the nearly constant In-dian threat, the people were basicallyconfined to this area for all that time,”said Hall, pointing to the presidio com-pound. “And so they left a tremendousarchaeological signature out here.”