When the West Turned South: Making Home Lands in Revolutionary Sonora

Transcript of When the West Turned South: Making Home Lands in Revolutionary Sonora

Western Historical Quarterly 45 (autumn 2014): 299–319. Copyright © 2014, Western History association

When the West turned South: making Home Lands in Revolutionary Sonora

andrew Offenburger

This article connects the lives of an American schoolteacher and a young Yaqui girl in Sonora during the Mexican Revolution. It uses the “home lands” frame-work, first articulated by Virginia Scharff and Carolyn Brucken, to show how settlement and resistance operated through family structures and the making of itinerant home places.

Este artículo conecta las vidas de una maestra norteamericana con una niña yaqui en Sonora durante la Revolución Mexicana. El artículo se basa en la idea de “home lands,” propuesta por Virginia Scharff y Carolyn Brucken, para analizar cómo el asentamiento y la resistencia operaron a través de redes familiares y la formación de hogares transitorios.

two people—an american woman and a young Yaqui girl—awoke to the realities of the mexican Revolution under very different circum-stances. the first, twenty-year-old marjorie Van meter, sat at a piano in her schoolhouse in Empalme, Sonora, in February 1913. Iowa-born Van meter had recently followed her older brother to Empalme to work for the Southern Pacific of mexico Railroad—he as head of its accounting bureau, she to educate the children of its american employees. although fears of nearby revolutionary activity preoccupied her, she maintained order through school

andrew Offenburger earned his PhD in history from Yale university and is currently the David J. Weber Postdoctoral Fellow at Southern methodist university’s Clements Center for Southwest Studies. He thanks John mack Faragher, Gilbert Joseph, Glenda Gilmore, Robert Harms, and Ned Blackhawk for their guidance. this article would not have been possible with-out the assistance of Juan Silverio Jaime León and Kirstin Erickson. Research support was pro-vided by the Howard R. Lamar Center for the Study of Frontiers and Borders and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery and abolition at Yale, a Richard E. Greenleaf Visiting Library Scholar award at the university of New mexico, and a Newberry Consortium in american Indian Studies Graduate Student Fellowship.

300 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

lessons and chord progressions. Van meter set parables to music to re-create a sense of american childhood for her students. Practicing for the next day’s lessons, she “beat the piano,” and her chords gave shape to an otherwise unfamiliar world, hundreds of miles south of the border. the melodies of her songs dissipated in the desert, but sounds of a dif-ferent sort pierced her ears and made her stomach drop with fear. “I nearly had heart fail-ure,” she wrote to her mother. “I was playing merrily and all of a sudden heard some Vivas out side the school house. Got on a chair and looked over the transom before I ventured out. Never did find out what it was about. thought for a minute I was captured sure.”1

thirty miles to the southeast, political instability had also infringed upon the life of young Ricarda León Flores. a few years before, on the eve of the revolution, a group of Yaqui leaders arrived near her home in Belem. Five-year-old León Flores knew nothing of the larger forces that had shaped her early childhood: warfare, campaigns of ethnic cleansing, and her parents’ prior deportation to central mexico. She only knew what her senses revealed to her: the bountiful fields of squash, beans, corn, and watermelon; the rhythm of the deer dancer at sacred ceremonies; the smell of burning mesquite transforming into charcoal; the sweetness of pitahaya, or dragon fruit; and the rumble of the train passing over recently built tracks. But the arrival of the lead-ers brought a new reality to León Flores’s family and a message to the Yaqui, or Yoeme, pueblos. Seven of the eight pueblos had rejected former President Francisco madero’s appeal to revolt against newly elected Porfirio Díaz. anticipating renewed hostilities, many families fled to the sacred Bacatete mountains.

If Van meter could have seen into the Bacatetes from her piano bench, she might have noted León Flores and her mother walking the winding paths between the moun-tain strongholds and the pueblos. Despite their geographical proximity, Van meter and León Flores never met. Van meter lived in Sonora for only six months before return-ing to Iowa while León Flores grew up in a world shaped by migration, finding her way and making her home in the pueblos. their lives could not have been more different. Yet by connecting these two figures now—one hundred years later—historians can learn much about social disruption, families, and resistance in revolutionary Sonora. Reconstructed through Van meter’s letters and León Flores’s recorded oral histories, among other sources, the lives of these two women provide a new perspective of the revolutionary borderlands. their experiences show how everyday men, women, and children dealt with the consequences of larger political and economic forces and how families crafted home places in contested zones.2

1 marjorie Van meter to mother, 22 February 1913, marjorie Van meter Letters, 1912–1916, Center for Southwest Research, university of New mexico (hereafter mVmL).

2 León Flores’s testimonios were recorded in Yaqui between 1986 and 1987 by her grandson, Juan Silverio Jaime León, who later translated them into Spanish, organized them chronologi-cally, and published them as Juan Silverio Jaime León, ed., Testimonios de Una Mujer Yaqui (n.p., 1998). In a portion of the testimonios, León Flores uses the voice of her mother to recount mem-ories from León Flores’s childhood. Jaime León provided supplemental information to the pub-lished Testimonios in an oral history interview (see footnote 55 for more information) and in

Andrew Offenburger 301

these women lived at the end of the era between 1848 and 1910, when the american West turned south to mexico and brought with it all the ripe and rotten fruits cultivated by manifest Destiny. Studies that have acknowledged this turn most often explore the economic and political links between the two countries, emphasizing the transformations effected by u.S. economic expansion.3 this southern flow consti-tuted what mexican historian Francisco R. almada called a “peaceful invasion” and the creation of a “semi-colonial economic order.” 4 underlying these arguments is the assumption that strong ties between u.S. capitalists and mexican markets destabilized mexican society in unique ways and that u.S. imperialism significantly fomented rebel-lion. In such works, the emphasis on economics and elites contributes to a top-heavy borderlands historiography.5 While offering valuable interpretations to explain why a railroad in Sonora would hire an american schoolteacher or why Yaqui families fled to the mountains around 1910, such macro histories divulge little about how these women and families shaped their own experiences within the revolution.

Studies on gender and families between 1890 and the 1930s, and their central-ity to redefining the mexican nation, can get closer to León Flores and Van meter. Several works have examined the role of female rebels and soldaderas (women serving as unofficial commissaries for soldiers in the field) who participated in rebellion and revolution and, in so doing, repositioned themselves within social hierarchies.6 Paul

personal correspondence with the author. all interviews, archives, and testimonios were trans-lated by the author.

3 John mason Hart noted, “u.S. elites sought to extend their interests into mexico by employing the strategies that were so successful for them in the american West.” Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War (Berkeley, 2002), 2. John mason Hart, Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution (Berkeley, 1987); Gastón García Cantú, Las invasiones norteamericanas en México (n.p., mX, 1971); William G. Robbins, Colony & Empire: The Capitalist Transformation of the American West (Lawrence, 1994); David m. Pletcher, Rails, Mines, & Progress: Seven American Promoters in Mexico, 1867–1911 (Ithaca, 1958); David m. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Trade and Investment: American Economic Expansion in the Hemisphere, 1865–1900 (Columbia, mO, 1998), 77–113; and Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898 (Ithaca, 1967).

4 Francisco R. almada, Resumen de historia del estado de Chihuahua (mexico City, 1955), 337.5 Daniel Lewis’s examination of the Southern Pacific of mexico suggests that railroad

executives were duped by high rhetoric and hopeless expectations. Iron Horse Imperialism: The Southern Pacific of Mexico, 1880–1951 (tucson, 2007). For more on u.S. capital expansion into the mexican North, see miguel tinker Salas, In the Shadow of the Eagles: Sonora and the Transformation of the Border during the Porfiriato (Berkeley, 1997) and mark Wasserman, Capitalists, Caciques, and Revolution: The Native Elite and Foreign Enterprise in Chihuahua, Mexico, 1854–1911 (Chapel Hill, 1984).

6 Elizabeth Salas estimates that women and children made up about a third of nineteenth-century folk armies. “the Soldadera in the mexican Revolution: War and men’s Illusions,” in Women of the Mexican Countryside, 1850–1990, ed. Heather Fowler-Salamini and mary Kay Vaughan (tucson, 1994), 93–105. For more on women in the revolution, see Jocelyn Olcott, mary Kay Vaughan, and Gabriela Cano, eds., Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico (Durham, 2006).

302 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

Vanderwood’s history of peasant unrest in northwestern mexico and the emergence of the Yaqui healer Santa teresa de Cábora connect women to revolt.7 mary Kay Vaughan’s analysis of rural education policy suggests that administrators in the 1930s “envisioned a modernization of patriarchy” that “sought to remake the family . . . in the interests of nation-building and development.”8 anthropologist Kirstin C. Erickson’s discussion of Yaqui “homelands and homeplaces” makes a strong argument that situates the fam-ily home at the core of Yoeme ethnic identity.9 Yet as much as these studies assist in understanding gender and family dynamics during the revolutionary era, they cannot fully bridge the gaps of class, race, and nation that divided these women—an american middle-class schoolteacher and an indigenous peasant girl. there are very real reasons why these two never met in their lives or in current historiographies.

the stories of Van meter and León Flores can be connected, though, by employing the “home lands” model, articulated by Virginia Scharff and Carolyn Brucken, to see how the revolutionary borderlands were “created both in tension and in tandem with the making and defending and reclaiming of home places.”10 By defining home expan-sively, such a framework provides two distinct advantages. First, it can accommodate interpretations of both place and process, of home and “home making.” this allows for women like León Flores to participate in the same historical narrative as someone like Van meter without either woman being cordoned off behind a moniker of settler or indigenous. Second, as Scharff and Brucken note, the home lands model does not confine women and families to domestic roles. It repositions both at the center of west-ern history.11 While Scharff and Brucken do not elaborate on their framework, their

7 Officials worried about adherents who “went to teresa for cures [but] were returning with rifles and other weapons.” Paul Vanderwood, The Power of God Against the Guns of Government: Religious Upheaval in Mexico at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century (Stanford, 1998), 229.

8 mary Kay Vaughan, Cultural Politics in Revolution: Teachers, Peasants, and Schools in Mexico, 1930–1940 (tucson, 1997), 11.

9 Kirstin C. Erickson notes that the home “is the site in which women’s gender and Yaqui identity are most strongly conjoined.” Yaqui Homeland and Homeplace: The Everyday Production of Ethnic Identity (tucson, 2008), 112, 73–135.

10 Virginia Scharff and Carolyn Brucken, eds., Home Lands: How Women Made the West (Berkeley, 2010), 2. although Scharff and Brucken do not locate their work within a broader his-toriography, it is worth noting that they draw upon a deep tradition of women, family, and com-munity studies published before the tide of new western history. these past works, however, priv-ilege a settler’s perspective. Home Lands implicitly reorients these studies and accommodates a multivocal past. Scharff and Brucken thus codify a more nuanced perspective of women and fam-ilies evident in newer works such as Sylvia Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870 (Norman, 1983); Sarah Deutsch, No Separate Refuge: Culture, Class, and Gender on an Anglo-Hispanic Frontier in the American Southwest, 1880–1940 (Oxford, uK, 1987); ann Laura Stoler, Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History (Durham, 2006); and anne F. Hyde, Empires, Nations, & Families: A History of the North American West, 1800–1860 (Lincoln, 2011).

11 Looking at homes and their creation—as both places and processes—gives historians the flexibility of a borderlands model while avoiding the arcane entanglements between Frederick

Andrew Offenburger 303

model has the potential to be a unifying theory and to level the historiographical field by avoiding the specializations that fragment the discipline at present.12

a home lands reading of this borderlands history, through the experiences of Van meter and León Flores, helps to connect women and families who developed the frontier with those in peasant resistance. the result highlights how families acted as agents of state formation and capitalist development as well as conduits of resistance, both indigenous and revolutionary. the role of women and families in making home lands thus exposes a new front—a home front—in studying western expansion and resistance.

as Van meter traveled south from tucson in mid-December 1912, she looked for signs to affirm her expectations of a wonderful Sonoran adventure. (See figure 1.) On

Jackson turner and Herbert Eugene Bolton. It is essentially a borderlands framework that shirks the burden of borders and forges ties with postcolonial historiographies. this widened field of vision connects with ann Laura Stoler’s analysis of power and domestic relations in the Dutch East Indies or with timothy Burke’s study of “Jeanes teachers” in colonial Zimbabwe. Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Berkeley, 2002) and Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women: Commodification, Consumption, and Cleanliness in Modern Zimbabwe (Durham, 1996).

12 One must be careful to avoid three potential weaknesses of this model: heteronormative bias, the inability to explain greed and corruption, and the term’s resonance with “homelands,” an altogether different and skewed conception of history infamous in post-1948 South africa and elsewhere. my thanks to Virginia Scharff, fellow panelists, and audience members at the 2012 WHa conference in Denver. Our discussions on the potential and the limits of the home lands model informed this article.

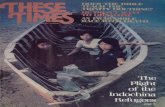

Figure 1. marjorie Van meter, 1913, Howard Van meter Pictorial Collection, 1905–1914. Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, university of New mexico.

304 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

board the train her older brother introduced her to executives, workers, the mayor of Empalme, and the head of the city council. However enthused, Van meter could not blind herself to unsettling sights such as the hundred soldiers boarding the train at the international border and the barbed wire fence surrounding her destination. She chose to focus on the positive, describing her new schoolhouse as a “peach” and “the cutest bungalow.” Over her six-month stay, Van meter would teach creative arts—drawing, watercolor painting, and rug designing—in addition to Spanish, a language she had never studied. Van meter took private lessons upon her arrival and began teaching six weeks later. “It sure is laughable,” she confessed. “Chinese sounds just about as easy.” In her classroom, Van meter asked her american students to speak in Spanish and another student, of mixed national heritage, to respond in English. “I didn’t know I was supposed to be a linguist,” she remarked. the pragmatics of frontier teaching trumped any vocational requirements.13

Van meter found herself thrust into a multicultural, multiracial borderland shaped by a long history of u.S. investment. after the u.S.-mexican War (1846–1848), Sonora had come under an intensified gringo gaze. the u.S. acquisition of half the territory of its southern neighbor could not appease all expansionists, who continued calling for “all mexico!” Fortune hunters and filibusterers began to eye the recently acquired lands and those farther south.14 By the 1860s, some americans sought to justify expansionist ideol-ogy within the rubric of benevolent conquest. “It will only be when we shall have thus taken possession of mexico,” wrote one texas Ranger, “that an end will be put to civil warfare within her borders, and her degraded population become elevated into prosperous, intelligent, and peace-loving citizens.”15 Of course, these calls for conquest all but disap-peared with the outbreak of the u.S. Civil War and the French intervention in mexico (1862–1866). But soon thereafter, writers again pushed for southern expansion in chari-table terms. Such logic persisted years later—reinvigorated by the mexican Revolution, in fact—when many u.S. elites supported annexation.

throughout this era, mexico became a logical extension of the american West. minerals and markets south of the border glittered in american minds. the port of Guaymas grew as a direct result of eastern and California investments.16 Historians and

13 Van meter to mother, 1 February 1913; 22 December 1912; and 3 February 1913, all mVmL.14 John D. P. Fuller, Movement for the Acquisition of All Mexico, 1846–1848 (Baltimore, 1936)

and Hubert Howe Bancroft, The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, Vol. 16, History of the North Mexican States and Texas (San Francisco, 1889), 673.

15 James Box, Capt. James Box’s Adventures and Explorations in New and Old Mexico. . . . (n.p., 1861), 13–4, 16. Such ideology continued well after the Civil War. Radical Reconstruction on the Basis of One Sovereign Republic. . . . (Sacramento, 1867), 8.

16 Sylvester mowry, Arizona and Sonora: The Geography, History, and Resources of the Silver Region of North America (New York, 1864). this is not to imply that american capital alone made Guaymas, nor, for that matter, Sonora. For the longer sweep of Sonoran history, which places u.S. economic expansion in context, see Cynthia Radding de murrieta, ed., Historia General de Sonora, Vol. 4, Sonora Moderno: 1880–1929 (Hermosillo, mX, 1985) and tinker Salas, Shadow of the Eagles.

Andrew Offenburger 305

travelers described transformations taking place in Sonora. One recalled, “Every steamer from San Francisco lands at mazatlan and Guaymas from 100 to 200 passengers, many of whom, disappointed in more northern regions, desire to establish themselves in the rich mineral fields of the south.” 17 Emphasizing the similarities between industries and environ-ments on both sides of the border laid the foundation for a southern extension of western dreams. California seemed a natural analogy for the mexican north, given its vast mineral wealth, environmental continuities, and ties between Guaymas and San Francisco. “the State of Sonora . . . belongs to the Southwest,” wrote one visitor in the 1890s.18 Walter S. Logan, president of the Sonora and Sinaloa Irrigation Company (SSIC), which sought to develop Yaqui lands, claimed in the 1890s that “Old ‘Forty-Niners’ will remember the California market in the times before the war. Sonora is the California of mexico, and history repeats itself.” Railroad executives and investors banked on his assertion that the locomotive would “work the same magical change” that it did in the West. Expansionists in the Southwest believed in the natural progression of the West’s southern turn and argued that “the american will find in mexico infinitely more pleasant and hopeful conditions than the american of forty years ago found in Kansas and Nebraska.”19 By the close of the nineteenth century, development of the “copper borderlands” appeared to verify the exorbitant promises made by u.S. capitalists.20 Historians have largely followed boosters’

17 J. Ross Browne, Adventures in the Apache Country: A Tour through Arizona and Sonora. . . . (New York, 1869), 173.

18 Edwards Roberts, With the Invader: Glimpses of the Southwest (San Francisco, 1895), 138, 122. For more on the parallels between Baja California and California, see Charles Nordhoff, Peninsular California: Some Account of the Climate, Soil, Productions, and Present Condition. . . . (New York, 1888), 6, 62. Contemporaries of Nordhoff also argued that Baja California shared more with the united States than with mexico. John F. Janes, “Lower California: a New Empire,” San Pedro Shipping Gazette, 22 December 1883, in The Filibusters of 1890: The Captain John F. Janes and Lower California Newspaper Reports and the Walter G. Smith Manuscript, ed. anna marie Hager (Los angeles, 1968), 23.

19 Walter S. Logan, Yaqui Land Convertible Stock (n.p., 1894), 3–4; William G. Le Duc, Report of a Trip of Observation over the Proposed Line of the American & Mexican Pacific Railway. . . . (Washington, DC, 1883), 4; alex D. anderson, The American and Mexican Pacific Railway, or, Transcontinental Short Line (Washington, DC, 1883), 10; and mexican Central Railway Company, Facts and Figures About Mexico and Her Great Railroad, The Mexican Central (mexico City, 1897), 8.

20 William C. Greene’s Consolidated Copper Company at Cananea exemplified the prom-ise—and the peril—of unrestrained investment in Sonora and the labor tensions that would unsettle the region after the strike at Cananea in 1906. For more on Cananea within a tradition of failed dreams in the borderlands, see Samuel truett, Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (New Haven, 2006). For more on race and labor in the arizona borderlands, see Katherine Benton-Cohen, Borderline Americans: Racial Division and Labor War in the Arizona Borderlands (Cambridge, ma, 2009). For a discussion on how u.S. development changed the natural and social geography of Sonora, see maría Patricia Vega amaya, “una indigación historiográfica sobre la presencia norteamericana y el curso geográfico de la revolución en Sonora, 1890–1915. . . .,” in De los márgenes al centro: Sonora en la independencia y la revolu-ción; cambios y continuidades, ed. Ignacio almada Bay and José marcos medina Bustos (Hermosillo, mX, 2011), 353–86.

306 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

lead, tracing investments in mexico while disregarding the vulnerable position of most americans south of the border.

marjorie Van meter represented this tenuous position as she re-created an american schoolhouse experience, teaching in a town financed by the railroads in a bungalow sur-rounded by a picket fence and behind barbed wire. (See figure 2.) Despite her isolation, she continued to enjoy some comforts of home sent by her family: american magazines, homemade dresses, and even a box of fudge. She explored nearby Guaymas with fellow americans to buy what lace she could afford on her modest budget of $80 per month. She declined invitations to dances, thinking she could not compete with the “Spanish girls’ Parisian evening gowns.” Van meter wrote she would give anything for linen dresses: “about the only thing they wear here after February is white linen and I haven’t a dud. . . . I’m not going to make a cent down here I can see that.”21 In defiance of her financial straits, though, Van meter maintained a moderate social life among her peers.

Outside the secure american enclave in Empalme, tensions mounted.22 Violence flared on occasion in the area between the Bacatete mountains and the nearby Yaqui

21 Van meter to mother, 10 may 1913 and Van meter to mother and tony, [25 December 1912?], both mVmL.

22 the revolution affected Sonora in unique ways but was part of a broader movement to effect agrarian reform. For the most definitive work linking peasant revolts in the varied regions of the country to a nationwide struggle, see alan Knight, The Mexican Revolution, 2 vols. (Cambridge, uK, 1986). Works linking the revolution with international affairs and reform movements, apart from those already cited, include John tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico: Social Bases of Agrarian Violence, 1750–1940 (Princeton, 1986) and Friedrich Katz, The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution (Chicago, 1981).

Figure 2. marjorie Van meter’s schoolhouse gave order amid chaos, 1912–1913, Howard Van meter Pictorial Collection, 1905–1914. Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, university of New mexico.

Andrew Offenburger 307

Valley. Locals had warned Van meter that the Yaqui Indians caused all of Sonora’s troubles. “Nobody knows what their fuss is,” she wrote. It was “just like the early days in the states. they murder for the fun of it. they don’t [go] after the americans. It’s the mexicans they want.”23 Van meter’s comments reveal her position within the orbit of american capital, interpreting local circumstances through a biased perspective of the western past. Van meter brought more than her beliefs and prejudices to the borderlands; teaching involved imparting her own experiences to her students. She served as a small but critical component in the reproduction of u.S. culture south of the border by maintaining ties to a shared home land. Her residence in this american bubble made her naive—if not vulnerable—to local developments, a truth exposed by her ignorance of the Yaquis’ “fuss” and the world beyond barbed wire.

She knew little of the longer history of her surroundings. For more than a cen-tury, the northern states of mexico (including the later u.S. Southwest) remained isolated outposts caught between competing peoples: Spanish, mexican, French, Comanche, apache, and american.24 the inaccessibility of these lands began to change as the Santa Fe trade blossomed in the 1830s and 1840s, but homesteads remained distant and detached from imperial metropoles. In this region, as Laura m. Shelton has shown, families adhered to a strict code of gender relations that regu-lated female chastity and patriarchal respect, thus distinguishing civilized Spanish and mexican settlers from the unrestricted barbarism of indigenous practices (polyg-amy and sexual licentiousness).25 Van meter sensed the intricacies of these cultural cues, yet they remained entirely foreign to her. Her comments on the evening attire of “Spanish girls” and frequent remarks about her weight revealed a timid outsider unfamiliar with established gender codes beyond Empalme. although unsure of her place within Sonoran circles, she had the luxury of living almost entirely within her own american sphere. through her instruction in English and in american prac-tices and childhood songs, Van meter furthered a corporate u.S. civilizing mission in Sonora. She embodied an “empire of innocence,” to use Patricia Nelson Limerick’s memorable phrasing.26

23 Van meter to mother, 14 December 1912, mVmL.24 For more on the Spanish and mexican empires, see David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier

in North America (New Haven, 1994) and David J. Weber, The Mexican Frontier, 1821–1846: The American Southwest Under Mexico (albuquerque, 1982). Recent works have contributed nuanced histories of competing peoples in the borderlands. For more on the confluence of Native american and European imperial struggles, see Brian DeLay, War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War (New Haven, 2006); Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven, 2008); Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge, ma, 2008); and Karl Jacoby, Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History (New York, 2008).

25 Laura m. Shelton, For Tranquility and Order: Family and Community on Mexico’s Northern Frontier, 1800–1850 (tucson, 2010), 3.

26 Patricia Nelson Limerick investigates the “innocence” of anglo settlers in the american West in The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York, 1987), 35–54.

308 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

Van meter’s comments on the Yaquis acknowledged a complexity that challenged the neatness of rectilinear streets and picket fences. the Yoemem, descendants of uto-aztecan peoples, had called the Yaqui River Valley home for centuries.27 Ever since their first encounter with Jesuit missionaries on Spain’s northwestern frontier, they had defended their tribal sovereignty in a remarkably effective dual strategy of resistance and cooperation.28 their religion, incorporating Catholic ideology and indigenous practices, and their celebration of the eight sacred pueblos—a Jesuit introduction—attest to the Yoeme ability to adopt, adapt, develop, and refine their self-identity through centuries of colonization and attempted conquest. Between 1876 and 1900, their resistance to Porfirio Díaz’s positivist ideology of progreso embarrassed the administration, which intensified campaigns of extermination and ethnic cleans-ing. as a result of this persecution, by the early 1900s, authors began to romanticize Yaqui ferocity (and impending extinction) in newspaper reports, borderlands memoirs, western literature, and dime novels.29 the Yaqui, wrote one visitor—note the singu-lar classification—“is disappearing in a lake of blood and when he is submerged the last dread war-whoop will shriek his requiem. It will never again be heard upon the earth.”30 Statements like this appeared more frequently in publications as the u.S. capitalist drive strengthened south of the border. Extinction narratives attempted to explain, if not exculpate, the effects of colonization in the borderlands. they repeated a centuries-old western refrain.

27 Edward Spicer’s three volumes on Yaqui culture and history established a strong founda-tion for the development of recent Yaqui historiography. Potam: A Yaqui Village in Sonora (Chicago, 1954); The Yaquis: A Cultural History (tucson, 1980); and People of Pascua (tucson, 1988). For a general history of the Yoemem and the Yaqui Valley, see Evelyn Hu-DeHart, Missionaries, Miners, and Indians: History of Spanish Contact with the Yaqui Indians of Northwestern New Spain, 1533–1830 (tucson, 1981); Evelyn Hu-DeHart, Yaqui Resistance and Survival: The Struggle for Land and Autonomy, 1821–1910 (madison, 1984); and Claudio Dabdoub, Historia de el valle del yaqui (n.p., mX, 1964).

28 this is not to be confused with the false distinction between pacíficos (pacified Yaquis) and broncos (rebels) identified by contemporary officials. Hu-DeHart, Yaqui Resistance and Survival, 123 and José Velasco toro, Los Yaquis: Historia de una active resistencia (n.p., mX, 1988). a fascinating case study of acculturation and resistance can be found in José Luis moctezuma Zamarrón’s analysis of linguistic persistence in Zamarrón, De Pascolas y Venados: Adaptación, cambio y persistencia de las lenguas yaqui y mayo frente al español (n.p., mX, 2001).

29 Dean Harris, By Path and Trail (Chicago, 1908), 1, 6, 8, 57. as a corollary to this, Yaqui representations in western fiction and other cultural productions began to emphasize indigenous resistance through a rhetoric that highlighted their ferocity and through the tropes of silence, secrecy, and the native gaze. Yaqui Indians soon began to make appearances in western novels, and southwestern lore and legend codified their renowned ferocity. Prentiss Ingraham, Buffalo Bill Among the Man-Eaters; Or, The Mystery of Tiburon Island (New York, 1908); Prentiss Ingraham, Buffalo Bill’s Totem, or the Mystic Symbol of the Yaouis [sic] (London, 1908); Cave of the Skulls, or, the Secret Hoard of the Yaquis (London, 1908); J. Frank Dobie, Apache Gold & Yaqui Silver (Boston, 1939), 157, 154–5; and Dane Coolidge, Yaqui Drums: An Authentic Western Novel (New York, 1940), 69.

30 Harris, By Path and Trail, 1.

Figure 3. Ricarda León Flores (seated) with her first cousin manuela, ca. 1925. Illustration in Juan Silverio Jaime León, Testimonios de Una Mujer Yaqui (n.p., 1998), 77.

310 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

In opposition to these narrative patterns, the Yaquis quite effectively maintained their claims to ancestral lands. thousands of Yoemem fought for sovereignty in what became the Yaqui diaspora, an informal network of social clusters extending from the henequen plantations of Yucatán to the Valle Nacional in central mexico to Sonora, arizona, and California. at the same time Van meter created a new home for her students and herself in Empalme, young Ricarda León Flores traversed the diaspora in the nearby Yaqui pueblo of Belem with her family, creating itinerant home places of a different sort. they did so to withstand mounting pressures on their lands, height-ened by the presence of the railroad and innocent imperialists like Van meter and her associates.

León Flores’s birth in 1905 thrust her into a life of migration, and she carried gen-erations of resistance within her. (See figure 3.) Her parents had survived the mazocoba massacre five years earlier, deportation to the Valle Nacional, indentured servitude, and a three-year return migration.31 During the early revolutionary years, her family rees-tablished a home between Belem and the tribal stronghold in the Bacatete mountains, enduring the most intense era of persecution in Yaqui history. “this my mother never forgot, as if running through her blood, from such courage and anger,” León Flores recalled, and then paraphrased her mother: “ ‘the yoris have always treated us like this,’ she would say. ‘Ever since arriving to these lands, you see, they sent us to other lands, they have whipped us, they have hung and executed us and still they do not defeat us, because we have stronger beliefs than they.’ ”32

Leading a life marked by migration forced the León Flores family to create home places on the move and in inhospitable regions: slave quarters in the Valle Nacional and hidden enclaves in the Yaqui Valley and the sierras of the Bacatetes. there young Ricarda found her home and her education: “Our school was how to defend ourselves, how to shoot a gun, how to climb peaks. that is what our elders taught us. For us it

31 I use “indentured servitude” here because it more aptly describes the experiences of León Flores, but the conditions of the Yaquis—and certainly their labor on the henequen plantations in Yucatán—were described as slavery by contemporary observers and labor activists such as John Kenneth turner, Barbarous Mexico (Chicago, 1911). Raquel Padilla Ramos looks into the accusa-tions of slavery—real or perceived—and does not find conclusive evidence of bodies for sale. She believes that current evidence in Yaqui oral histories relating to slavery comes from a feedback loop originating in turner’s writings. Regardless, Yaquis today are convinced the experiences of their ancestors constituted slavery. In some ways, it is a moot point, as slavery is less noteworthy historically than the explicit extermination campaigns and deportations that characterized the excesses of the Porfiriato. Progreso y libertad: Los yaquis en la víspera de la repatriación (Hermosillo, mX, 2006) and “Los Partes Fragmentados: Narrativas de la Guerra y la Deportación Yaquis,” (PhD diss., universitat Hamburg, 2009). For the Yaqui role within larger historical dynamics, see Gilbert m. Joseph, Revolution from Without: Yucatán, Mexico, and the United States, 1880–1924 (Durham, 1988) and Sterling Evans, Bound in Twine: The History and Ecology of the Henequen-Wheat Complex for Mexico and the American and Canadian Plains, 1880–1950 (College Station, 2007).

32 Jaime León, ed., Testimonios, 8. León Flores says the Yaquis have stronger razones than do yoris, which I interpret as “beliefs,” but “reasons” or “rights [to the land]” may come closer to her intended meaning.

Andrew Offenburger 311

was nice, because we were not yet aware of the danger.” Baptized in the mountains, León Flores and her mother spent the year between 1909 and 1910 in the shelter of the renowned rebel leader José maría Sibalaume. In her testimonios, León Flores recalled the importance of Sibalaume’s “kitchen,” or the open eating area beneath a shady ramada. there “we helped the rest of the women,” she remembered her mother saying. the area “was used for serving visitors or for the news scout who arrived every day to notify us of news from the detachments, the general [Sibalaume] was informed of everything that happened, below in the pueblos, the movements of the federales, everything.”33 the migrant kitchen functioned in two overlapping ways: Yaqui women served sustenance while men learned of the latest military developments.34

mobility and women’s home places influenced León Flores’s childhood just as it sustained Yaqui strategies of resistance. She and her family cultivated fields in Belem both before and after the revolution. the produce fed her immediate family and sup-ported her absent brother, Juan, who moved among Yaqui rebels in the Bacatetes. Fighting alongside Sibalaume, Juan seldom saw his sister despite his frequent trips to the valley. under the cover of night, he and other emissaries participated in cor-rería, or taking food and provisions from haciendas.35 Such activities—what officials called “depredations”—sustained the tribe through times of great suffering. the Yaquis ideologically justified rustling horses, killing cattle for meat, stripping settlers of their clothes, and stealing hundreds of bushels of produce. Such encounters only tended to turn violent when settlers resisted.36 By the middle of 1912, for example, thefts on local haciendas rose to more than one per day, even at a time of ongoing talks with peace commissioners. the attacks on local ranches intensified throughout the early years of the revolution and destabilized the region. municipalities around the Bacatete mountains complained of lawlessness. Ranch workers refused to har-vest the fields. townsfolk requested guns and other protection from their local and state governments. many farmers—mexican, american, and others—threatened to leave the valley.37

33 Ibid., 29, 21.34 the creation of home places in the Bacatetes inevitably differed from established Yaqui

homes in the pueblos. Recent studies have shed light on the roles of women within the Yaqui home, what Erickson identifies as the “kernel of Yaqui Society.” Yaqui Homeland, 97. On space, gender, and the home, see maritere Zayas, “tres mujeres curanderas yoremes” and Óscar Sánchez, “Comer y cocinar: naturaleza y cultura,” both in Símbolos del desierto, ed. maría Eugenia Olavarría (n.p., mX, 1992), 103–22, 123–44.

35 Jaime León, ed., Testimonios, 22.36 this statement only applies for the early months of the revolution, when tentative peace

agreements were reached. With the eventual failure of Francisco madero’s peace commissions, politically motivated violence against settlers increased.

37 By the end of 1912, more than three hundred residents near San Javier petitioned for immediate protection from the government, given the destruction by the Yaquis of the towns of San marcial and San José de Pimas and the haciendas La Cuesta, agua Caliente, Noria de Pesqueira, Ojo de agua, Noria de Elias, La Palma, Palos altos, “and several others, all located to

312 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

although Yaquis proved resilient, they barely survived amid dire circumstances. In the Bacatetes, they sometimes lived with one water source and perished from malaria and other diseases, with “ten to twelve deaths a day being taken as a matter of course.”38 they made little attempt at cultivation in the mountains, relying on correría for provi-sions. Everything “indicated a very temporary sojourn,” said a rare visitor to the moun-tains, “as if they were just camping for a while, though generation after generation was born and raised at the same spot, which was and is the only home the Yaqui Indian ever knew.”39 these observations underscore the connections between rebelling Yaquis in the mountains with cultivators in the valley. Strong familial alliances—such as the bond between León Flores and her brother—united the various groups together in resis-tance. ancestral homelands provided material support for the mountain strongholds, the main source of power, to ensure the continuation of Yaqui life in the valley. much like soldaderas alongside men in the battlefields, women’s work in the valley enabled the Yoemem to survive the first years of revolution. By early 1913, when Victoriano Huerta led a coup and ousted Francisco madero, León Flores and her mother had established a renewed sense of normalcy in Belem pueblo. the peace would not last long for them, nor for Sonora.

In Empalme, Van meter’s piano chords lingered among the mesquite and cholla on the very day of madero’s assassination. a cry of “Viva!” startled her. “I could hardly teach school yesterday for watching the soldiers,” she later wrote. “they go right past the school-house to get to the barracks. they were filing past all day.” Constitutionalist revolutionaries—in favor of progressive social reform but against the brutality of Huerta’s coup—disrupted train service to the united States. By 21 march 1913, Van meter’s sense of home became unsettled. In addition to political updates sent home to her fam-ily, she commented on changes in her daily life. “Eggs have given out and we have to eat mex[ican] butter which is awful,” she wrote. She stopped frequenting her dining hall, called “mamasitas,” because of overcrowding by soldiers. the regional militarization also disrupted school lessons. In spite of any growing anxiety, Van meter tried to maintain some stability. She attended a baseball game between offshore american sailors and the Empalme team. She bought a French parasol. She continued her own Spanish lessons.40

the escalating rebellion soon shattered any newfound normalcy. On 14 april the general superintendent of the Southern Pacific Railroad of mexico distributed

the northeast of the Bacatete.” W. C. Laughlin et al. to gobernador, 6 November 1912, tomo 2784, ramo Oficialía mayor, archivo General del Estado de Sonora, Hermosillo (hereafter aGES).

38 General B. J. Viljoen, “tribe at War for a Century,” Los Angeles Times, 13 February 1916. Viljoen served as peace commissioner to the Yaquis under President madero from 1911 to 1912. While I question Viljoen’s estimates of the number of daily fatalities, his observation that disease acutely affected Yaqui rebels in the sierras is an important detail that often goes unexplored. Correspondence between Viljoen and José maria maytorena, January and February 1912, tomo 2782, aGES.

39 Viljoen, “tribe at War for a Century.”40 Van meter to mother, 2 and 21 march 1913, both mVmL.

Andrew Offenburger 313

a letter instructing all americans to seek shelter in parked railcars near El morrito Beach, between Empalme and Guaymas. (See figure 4.) Van meter moved into a Pullman car with five adults, five children, an african american porter, and a Chinese cook. theirs was but one car in a string of forty-five stationed near the beach, a makeshift refugee camp for americans. the cramped quarters challenged her sense of privacy, but Van meter enjoyed her new home. the personal attention flattered her. She felt as if she lived in “quite the city,” right on the beach. “I prob-ably never will live in such [a] state again,” she wrote. But three weeks of Pullman living—and an entire month without teaching—quickly sapped Van meter’s sense of adventure. She wrote of the 100-degree heat in her railcar, described some com-patriots as “snobbish,” and noted with false intrigue the “nice little flock of cock roaches in my bed.” Van meter tired of always “having to live with a suitcase in one hand and a gun in the other. . . . Living in one car with five bawling kids completely ruined my disposition.” 41

Van meter’s camp replicated the american form of homemaking in the bor-derlands, in which gender divided the social roles. men guarded the railcars and constructed makeshift walkways while women performed limited household duties. and race determined status. White americans needed protection from revolution-aries as well as from unemployment. When the company’s lack of operations led to downsizing, Van meter noted, it “fired all [the] mex[ican] boys in the office.” 42 the african american porter and the Chinese cook were identified only by their

41 Van meter to mother, 18 april 1913; 5 June 1913; and 5 may 1913, all mVmL.42 Van meter to mother, 5 may 1913.

Figure 4. americans at El morrito, 1913, Howard Van meter Pictorial Collection, 1905–1914. Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, university of New mexico.

314 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

duties. Van meter and the americans living on El morrito Beach lost the comforts of home but not the complications of culture.43

Battles erupted, fought in clusters throughout the country and near Sonoran beaches. In early may 1913, the federal battleships General Guerrero and Morelos entered the bay near Guaymas along with the merchant ship General Pesqueira and its 1,500 soldiers. they shelled Guaymas and Empalme and eventually took the port—the only federal stronghold in a resolutely Constitutionalist state. Van meter witnessed the approach of the battleship and the incipient fighting. From her vantage point several kilometers away she saw a flash from the boat’s artillery followed by “the boom of the gun and then away over in the hills the puff of white smoke where the shell had exploded.” the ship fired past the american refugees to target Constitutionalist rebels further inland. Both government and rebel officials avoided involving the americans, now protected by two additional u.S. warships in the harbor. Like her fellow citizens watching the revolution from rooftops in San Diego and El Paso, Van meter rather enjoyed the spectacle and felt secure as a voyeur. “We sat down on the Beach last night and watched the Glacier and the California [ships] talk with ‘flashers,’ ” she wrote. “It certainly was pretty.” 44

through the window of her immobile railcar Van meter also witnessed the revo-lution’s human migrations. Sympathetic to the plight of the soldaderas, she wrote that she felt “sorry for the wives of the soldiers. When the mex[ican] Soldiers march they take their wives and all their house hold goods with them and the women have to carry all that.” (See figure 5.) In the nameless faces that passed before her railcar window, Van meter unwittingly saw the migratory future that would shape León Flores’s life in the 1920s and beyond. Exasperated by the discomfort of her beachside resort—not a paradise but a last resort—and threatened by escalating violence, Van meter decided to return to Belle Plaine, in her native Iowa.45 While Van meter returned unscathed by her Sonoran experience, León Flores’s journey had just begun.

With the struggle between Constitutionalists and federales in Sonora, the political instability that challenged state officials proved beneficial to the Yoemem.46

43 Landmark works in western history have explored, explicitly or otherwise, the persistence of cultural beliefs along routes of human migration. John mack Faragher, Women and Men on the Overland Trail (New Haven, 1979); Elliott West, The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado (Lawrence, 1998); and Virginia Scharff, Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age (albuquerque, 1992).

44 Francisco R. almada, La revolución en el estado de Sonora (Hermosillo, mX, 1990), 94 and Van meter to mother, 5 and 21 may 1913, both mVmL. For more on the spectacle of the revolu-tion, see David Dorado Romo, Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez, 1893–1923 (El Paso, 2005).

45 Van meter to Louise, 7 may 1913 and Van meter to mother, 5 June 1913, both mVmL. my description of Belle Plaine as Van meter’s “native Iowa” only underscores the similarities between home lands in the making of the american West and in the borderlands after 1880.

46 Huerta’s coup against madero divided the nation, compelling the Sonoran government not to recognize the Huerta administration. merchants and hacendados (landowners) felt the

Andrew Offenburger 315

Revolutionary factions diverted attention away from the capitalist development of the valley, and León Flores and her mother lived peacefully for several years. Her edu-cation may have come from the open air of mountaintops, but her development as a woman followed the closed strictures of Yaqui gender relations. In her early teens, León Flores’s family arranged her marriage despite her objection. “I felt horrible,” she said. “I didn’t know if I should cry or scream, run or get lost, but that was the agree-ment my family made and I had to accept it.” She wed Francisco Buitimea matuz on 24 June 1918 in Vícam pueblo. In the first months of marriage she felt like a slave in her own home, but daily life over the next eight years assuaged such feelings, or perhaps numbed her to them. She grew closer to her husband and became accustomed to the routine of life in Vícam. In 1927, however, the federal government renewed hostili-ties against the Yaquis, prompting families to flee to the Bacatetes yet again. When her husband proposed moving to the sierras, a pregnant León Flores felt relieved. the opportunity to move back to the mountains appealed to her and caused old feel-ings to resurface. Her structured life in the valley suddenly paled in comparison to a

short-term effects most acutely through economic instability. the long-term effects of renewed upheaval eventually forced Yaqui leaders to align themselves with varied factions vying for power. Of the major revolutionary fighters, the Yaquis most forcefully supported Álvaro Obregón, a peas-ant who grew up eighty kilometers south of the Yaqui home lands in mayo country and had made a name for himself fighting in the Sonoran north. Obregón, like his predecessors, recognized the value of Yaqui support. He courted officials, promising to recognize indigenous lands upon mili-tary triumph. For more on the Yaquis and revolutionary factions, see ana Luz Ramírez Zavala, La participación de los Yaquis en la Revolución, 1913–1920 (Hermosillo, mX, 2012), 33–115.

Figure 5. Itinerant Yaquis on their home lands near Empalme, ca. 1913, Howard Van meter Pictorial Collection, 1905–1914. Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, university of New mexico.

316 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

migratory one. the thought of it, she said, “inspired me to keep living and to fight to see my first child born.” 47

the couple fled around 1927 with four other families to places León Flores remem-bered from her childhood. She visited her abandoned home, “and there remained only rubble and ashes of the house we once had. Soldiers had burned it during the last cam-paign against the Yaquis.” 48 For months the young couple became accustomed to the natural beauty of the sierras, which enveloped them in the dual worlds of Yaqui cos-mology: the spheres of human life and nature.49 But when messengers warned of active battles nearby, she and her husband moved yet again. this time, men separated from women: the former went to war and the latter to shelter. as her husband marched away, León Flores turned and saw him “waving his hat [goodbye] without knowing that he would never see me again. He was lost from my life forever.” the goodbye pained León Flores, and soon, “in plain view of the peaks and chased by soldiers,” she walked to Bejoribampo and gave birth to a baby boy.50 Like her mother, León Flores experienced childbirth beyond the bounds of her home.

Soon after, she and other women were caught by a unit of soldiers and deported to mexico City to support the federal army—the Yaqui 22nd Battalion—as soldad-eras. although deportation wrought havoc on Yaqui lives, captives also made what they could of their surroundings. In mexico City, for example, León Flores lived with her brother, Juan, and his godfather, a highly ranked Yaqui general. their mother, sent from Sonora, joined the siblings. León Flores and her mother readjusted to living away from home. they enjoyed excursions on Sundays to cosmopolitan destinations like the floating gardens of Xochimilco, the presidential palace of Chapultepec, the renowned alameda boardwalk, and the national cathedral. Even in the midst of revolution, León Flores and her family could carve out a home place of their own.51

Over the next twenty years, León Flores married twice more, gave birth to four more children (after losing her firstborn), and resettled in the Yaqui pueblos. Beyond political instability, two influences shaped the lives of Yaqui women in the revolution-ary years. First, the effects of social disruption tore at the fabric of Yoeme households. León Flores’s father disappeared from her life (after her baptism in the Bacatetes) for reasons unexplained to her. She lost her first husband before her deportation to mexico City and her second husband never returned from his military tours to live with her in Sonora. (Both, she later learned, had lived and created families elsewhere.)52 It is easy to

47 Jaime León, ed., Testimonios, 44–5.48 Ibid., 45.49 the Sonoran environment forms a sacred part of Yaqui religious and spiritual belief. the

most visible component of this life/nature amalgamation is the deer dancer, the iconic image of Yaqui culture. For more on religious beliefs as practiced in Sonora, see Spicer, Yaquis.

50 Jaime León, ed., Testimonios, 46, 47.51 Ibid., 50–2.52 Only years later did she learn that her first husband had moved to work at a

Andrew Offenburger 317

find fault with the men, but the uncertainties of social disruption also influenced their ability to adapt to migration, deportation, or military conscription. anthropologist Jane Holden Kelley suggests that the “fact that individuals, especially men, were so inter-changeable in fulfilling basic family roles contributed markedly to the preservation of family cores.” to adjust to such unexplained absence and loss, León Flores developed an ability to simply cut ties and continue. Kelley, in a study of four other Yaqui women’s life histories, refers to this trait of emotional detachment that pervades Yaqui society as an outgrowth of resistance generations deep.53

a second influence—the Yaqui compadrazco, or godparent system—enabled León Flores’s survival and is a prominent theme in her testimonios. Introduced by the Jesuits in the seventeenth century, the Yaqui compadrazco contributed in unique ways to Yoeme ethnic identity.54 León Flores’s godparents appear at critical points throughout her life, enabling her migration to Sibalaume’s stronghold, her family’s reunion in mexico City, and her migration back to Sonora—not to mention the everyday contacts that guided her social life in the pueblos. In a culture where religious ritualism governed daily interactions, and where persecution had caused repeated migration, the compadrazco functioned where blood relatives failed. It is revealing how frequently the testimonios of León Flores alternated between using padrino (godfather) and padre (father) when referring to her brother’s godfather, for example. at minimum, the system of godpar-ents and other indirect kinships helped to maintain links with families dispersed over a vast geographical area during a time of intense persecution. For a people struggling against annihilation, the compadrazco proved invaluable.

León Flores and her family survived the darkest moments of Yaqui history because of their persistence and adaptability. Indeed, during the Porfiriato, in the early years of the revolution, and in campaigns against the Yaquis in the 1920s, officials explicitly tar-geted family structures. Speaking on the mass deportations after the Battle of mazocoba, León Flores’s grandson said, “there they separated the Yaquis.” the government “did

remote hacienda after fighting federales in the sierras. In her testimonios, she offers no reasons nor ventures any guess why he did not return. Her second husband stayed behind in central mexico before marrying another woman. He then left her and tried to return to León Flores, who had remarried a third and final time.

53 Rosalio moisés, Jane Holden Kelley, and William Curry Holden, The Tall Candle: The Personal Chronicle of a Yaqui Indian (Lincoln, 1971), xlii and Jane Holden Kelley, Yaqui Women: Contemporary Life Histories (Lincoln, 1978), 35–6. Kelley hypothesizes that these shallow emo-tional bonds developed in response to the widespread social persecution between 1880 and 1920. While she does not claim to prove this theory, the experiences of León Flores—and the women in Kelley’s study—support such an interpretation. For example, León Flores’s mother revealed that her missing father resided in another part of the state, living with another woman and their family. León Flores notes a fleeting sadness in her mother’s voice, until she changes subjects—reins in her emotions—to talk about revolutionary developments. In this, as with other stories of loss and abandonment, protracted grief appears to have been a luxury ill afforded during the years of persecution.

54 Erickson, drawing on Spicer, discusses the unique aspects of Yaqui compadrazco in con-temporary society. Yaqui Homeland, 116–9.

318 autumN 2014 Western Historical Quarterly

not want complete families, really, united families. to separate them was the most effective way to break the traditional power structures.”55 as a result of intense perse-cution, the Yoeme family responded through the creation of itinerant home places as much as it relied upon “emotional shallowness” and compadrazco. thus, the family itself became a site of resistance against state aggression and capitalist development. León Flores’s ability to adapt to dire circumstances—like her mother, like the Yaqui family writ large—ensured her survival in migration and in exile. She was ultimately able to return to Sonora to live the rest of her life in the pueblos with her children and grandchildren. León Flores spent her later years taking on larger roles in Yaqui religious celebrations and sharing her oral histories with close family members. today she is buried beneath an unlabeled white cross amid hundreds in Belem (now com-monly called Pitahaya). Her memory is carried by those who tell her stories and in the publication of her testimonios.

after leaving Sonora, Van meter spent the rest of her life in Iowa in relative anonymity. She lived in Vinton, thirty miles from her parents, where she worked as a stenographer at a law firm. She never married, never had children, and passed away in 1947. a small, square stone marks her grave in Oak Hill Cemetery in Belle Plaine. traces of her life exist only in census documents, brief mentions in local newspapers, and an archival repository at a state-funded university.56

although categories of nationality, class, and culture separated the experiences of these two women, their shared experience of making home lands amid revolutionary chaos offers a way to understand why and how individuals and families responded to larger historical forces and how they shaped their own lives and influenced regional developments. Van meter and León Flores each created an itinerant home place in order to adapt to social disruption and dislocation. Each lived in a new land and accommo-dated changing relations between family members and surrogate relatives. Both led ad hoc lives as women adjusting to male absence. and both worked within their culture’s

55 Juan Silverio Jaime León, interview with author, 25 June 2012, Ciudad Obregón, Sonora. Evelyn Hu-DeHart also notes that the deportations had the purpose of “drying up the social base of support” to undercut rebel activities. “Peasant Rebellion in the Northwest: the Yaqui Indians of Sonora, 1740–1976,” in Riot, Rebellion, and Revolution: Rural Social Conflict in Mexico, ed. Friedrich Katz (Princeton, 1988), 165. my interview with Jaime León was one of a dozen oral his-tory interviews I conducted in Sonora in June 2012. I obtained permission to conduct interviews from authorities in several of the pueblos, although current political in-fighting made obtaining permission from all authorities impossible. When participants agreed, I recorded the interviews and took portrait photographs. Copies of these materials will be deposited with the Yaqui museum in Cócorit and also distributed among the participants themselves. my thanks to Kirstin Erickson for her generosity in helping establish contacts in Pótam pueblo. For other pub-lished accounts of oral histories about the Porfiriato and early revolution, see alejandro aguilar Zeleny, ed., Tres procesos de lucha por la sobrevivencia de la tribu yaqui: Testimonios (n.p., 1994) and Raquel Padilla Ramos, Los irredentos parias: Los yaquis, Madero y Pino Súarez en las elecciones de Yucatán, 1911 (n.p., 2011).

56 thanks to mitch malcolm, president of the Belle Plaine Historical Board, for his efforts in searching for archival traces of the Van meters.

Andrew Offenburger 319

system of gendered roles and expectations: Van meter as a teacher who remained self-conscious of her spinsterhood and body image; León Flores as a child, wife, and mother who courageously—almost with nonchalance—dealt with loss.

the home lands model offers an opportunity for comparison by calling attention to these similarities, but the differences are equally instructive. Each woman’s location within her culture becomes all the more pronounced. Van meter’s railcar on El morrito replicated nationalist and racial hierarchies while battleships launched shells around her privileged bubble. a Chinese cook made meals in the open-air pit; an african american porter attended to the needs of all. Van meter’s complaints of the heat, the tarantu-las, the cockroaches, and the bawling kids appear trivial when viewed alongside León Flores’s struggles. as a result, Van meter’s discomforts belie her privileged position. they merely convey the smooth rails of empire upon which she traveled. although she faced real dangers by her mere presence in Sonora, Van meter easily carried her burdens and propagated the empire of innocence that was her Sonoran adventure. Her privileged position—and that of other american and mexican “settler” women—becomes even clearer by juxtaposing the railcar at El morrito with the ramadas of the Bacatetes or past homes burned to ashes. after all, Van meter chose to teach in Empalme; she just as easily decided to end her stay.

Whereas extended kin networks figured less prominently in marjorie Van meter’s experiences, they sustained life in the home lands of Ricarda León Flores. State offi-cials since the late Porfiriato had targeted Yaqui families, and in response, the Yoemem adapted. Women and families supported military operations in Sibalaume’s kitchen, where meals and military information crisscrossed daily. Individual Yaqui families sur-vived by the fields they harvested, the correría they relied upon, the compadrazco alli-ances they made, the emotional bonds they guarded, and the homes they created in migration. making home lands enabled both Van meter and León Flores to reconstruct their lives amid revolutionary Sonora, a process that also exposed the values and the relations that shaped their past.