When Foreign Trade Collapsed... Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914 - 1924

Transcript of When Foreign Trade Collapsed... Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914 - 1924

When Foreign Trade CollapsedEconomic Crises in Finland and Sweden,

1914 - 1924

by Timo Myllyntaus and Eerik Tarnaala

Starting Points

Small countries tend to float with the tide like wooden chips in the rough sea:they surge up with the upswings of the world economy and fall down with theslumps. Their business cycles closely follow international cycles, whereas bigeconomies have better opportunities to counterbalance external effects andjust rock on the waves like big ships during the storm. According to this argument, the reason for the differences between small and big countries lies intheir dissimilar dependence on foreign economies. On the one hand, smallcountries can seldom obtain all basic raw materials and energy sources withintheir borders. In contrast, big countries are generally more self-sufficient inthese respects. On the other hand, small countries, especially in Europe, aremore active traders than big ones. Exports and imports often contribute morethan half the GDP in small countries but less than half in many big countries.1

The above hypothesis, that small, open economies are more tightly anchored to international business cycles and development trends than bigcountries, is, however, not universally accepted among economists and economic historians. During the past two decades, it has been frequently challenged, for example in the Nordic debate. It has been argued that despite avery large foreign trade, economic development in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden has been “decisively determined by internal factors.’ Criticsquestion the significance of supply-led growth, while they. emphasise demandimpulses from the home market. They consider that a large foreign trade is

Fritz Hodne, “Countiy Size and Export Specialization: The Case of Denmark andNorway in the Modern Era’, Cross-Count,- Co,npoiisons of Industrialisation in SmallCountries 1870-1940. Attitudes, Otganisational Patterns, Technology, Productivity, Ed.Olle Krantz, Occasional Paper in Economic Histoiy no 2, (Ume: UmeA University,1995), p. 68.1 Fritz Hodne has analysed this debate in his publications, e.g. “Export-led Growthor Export Specialization?,” Scandinavian Economic Histo,y Review, vol. 42 (1994) no3, pp. 296-310.

24 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

just a consequence - not a cause — of a thriving and growing national economy.

What happens to small countries with vigorous foreign trade when majordisturbances unexpectedly intervene? How quickly can they adapt to the newsituation and substitute internal factors (raw materials, machinery, markets)for the lacking external ones? These complex questions can hardly be answered by general replies. Examining the topic on the basis of historical experience is more appropriate. Therefore, we chose Finland and Sweden forour case study in order to examine the economic performance of two smallcountries during World War I. In this article, we consider the hypothesis thatin a small country the degree of dependence on external factors and internalflexibility is revealed during a major crisis in foreign trade.

In addition to examining their dependence on foreign trade, we also aimto analyse the severity and character of the economic crises in the two Nordiccountries and its affect on the various sectors of the economy and the mainpopulation groups? Our third aim is to survey the governments’ measures toovercome the crisis that — as the contemporaries claimed — was unexpectedand the worst for two generations. Finally, our fourth objective is to evaluatethe lessons of the wartime crisis, i.e. what changes did the crisis bring to Finnish and Swedish economic policy in the long run.

The Basic Facts of Prewar Finland and Sweden

When the Great War broke out in 1914, Finland and Sweden were politicallyin a completely different situation. Sweden was an old, independent kingdomfollowing — at least formally — a neutral foreign policy. From 1809 on, Finland had been an autonomous Grand Duchy under the reign of the Russiantsar; it had no foreign policy at all. Because Russia became a belligerentcountry on the side of the allied nations, Finland had to follow the lines of thetsarist foreign and military policy. Since the Grand Duchy had no army of itsown, Finns were not mobilised in military service. In contrast, Russian troopsin Finland were increased from 30,000 to more than 120,000 soldiers to prevent a possible landing of the German army.’

While the Russian governor-general Frans Seyn declared martial law inFinland in late July 1914, Sweden remained neutral and continued its trade

Maui Närhi, “Venhlaiset joukot Suomessa autonomian aikana, VenäläisetSuomessa 1809-1917, Historiallinen arkisto 83, (Helsinki: Finnish Historical Society1984), pp. 161-180.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 25

with both the central powers and the allied countries. By closing the BalticSea in the south, Germany aimed to blockade Russian and Finnish trade withthe western allies, of which Britain was the most prominent market for Finnish exports. The war had therefore an immediate and marked impact on theFinnish economy.

Prior to World War 1, both Sweden and Finland had been active tradingcountries that exported similar bulky industrial goods and basic agriculturalproducts. Both also had large territories (Finland 378,000 km2 and Sweden439,000 km2), although by population (3.0 million and 5.6 million respectivelyin 1913) they were small countries. Another common feature was that thecountries possessed similar and not very versatile natural resources, such astimber and hydropower, whose quantities were, however, considerable byEuropean standards. Sweden differed from Finland in that it had some coaldeposits and much richer deposits of iron and copper ore.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, manufacturing was growing strongly onboth sides of the Gulf of Bothnia. Despite various differences, resemblingfeatures were conspicuous. For instance, saw milling was their biggest industry. The two forested countries were among the five largest exporters of sawntimber and had Britain as their primary customer.1

In both countries, pulping and paper production were also importantwood-processing industries. Sweden was more focused on pulping and it exported its production to Western Europe. Prewar Finland preferred to refineits pulp further into newsprint and paper, and 80 per cent of these productswere exported to Russia. Exporting sawn timber to Britain and the rest ofWestern Europe and newsprint and wrapping paper to the East, Finland wasmore specialised in wood-processing than Sweden.

In contrast, Sweden had a much larger metallurgical industry and a moreadvanced engineering industry, both of which also exported a great deal oftheir output. The Finnish metallurgical industry was obsolete and shrinkinginto a home-market industry, while engineering workshops were supplyingtheir goods only to local and Russian customers. In addition, mining andquarrying were more significant in Sweden due to its more abundant natural

1 K-G. Hagstrom, ‘Bidrag till en internationell trävarustatitisk,” Ko,nme,riella Meddelanden vol. (1923) no 17, pp. 667-682; Timo Myllyntaus, Finnish Industry in Tiunsition, 1885-1920, Responding to Technological Challenges (Tammisaari: The Museum ofTechnology 1989), pp. 11-26.

Timo Myllyntaus & Ecrik Tamaala

endowments. Although one promising copper mine at Outokumpu had justbeen opened, mining was in general decline in Finland.’

Except for dairying, both the Finnish and Swedish foodstuff industries aswell as the textile industries were predominantly serving the home market.Nevertheless, these industries were among the largest manufacturingbranches in both countries. In contrast, the chemical industry in Sweden wasrapidly growing and export-oriented, whereas its Finnish counterpart wassmall and import substituting.

On the eve of World War I, Finland and Sweden were semi-industrialisedcountries, where industries were based on such indigenous natural resourcesas timber, hydropower and iron ore. In 1910, manufacturing, handicrafts andbuilding construction employed 10 per cent of the workforce in Finland and32 per cent in Sweden, which was not only more industrialised but also had astronger and more versatile industrial structure than its eastern neighbour.’

Both countries had traditionally had Britain as their main trading partneroutside the Nordic countries. On the eve of World War I, the significance ofGermany as a major trading partner had been increasing notably, especiallyas a supplier of machinery to the Nordic countries.

At the turn of the century, Finland and Sweden together with Belgium, theNetherlands, Denmark and Switzerland belonged to the countries whoseexports accounted for a fairly high proportion of GDP. In 1913, the proportion was about 25 per cent for Finland and 21 per cent for Sweden. The corresponding percentages for big countries, such as Germany and Britain, weresubstantially smaller.

On the eve of Word War I, agriculture and forestry was still the dominantsector in both Finland and Sweden. In 1910, the primary sector employed 70per cent and 49 per cent of the labour force, respectively. Both countries weredeliberately developing their dairy production, and each was able to exportannually more than ten thousand tons of butter, mainly to Britain and otherWestern European countries. In the prewar years, harvests in both countries

‘ Timo Myllyntaus, Technological Change in Finland and Jan Hult, “Technology inSweden,” Technology and Indust,y, A Nordic Heritage, Eds. Jan Hult and BengtNystrom, (Canton, MA: Science Histoiy Publications 1992), pp. 41-48, 83-88.

In Finland, industry at the time accounted for 13% of the total employment. Y.Aberg, Produkrion och produktivitet i Sverige 1861-1 965 (Uppsala, 1969), p. 17; RiittaHjerppe, The Finnish Economy, 1860-1985. Growth and Structural Change (Helsinki:Bank of Finland 1989), pp. 62-64, App. hA.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 27

were normal. As it happened, by July 1914 Finland had stocked more grainthan usual at that time of the year.

When the Great War broke out, the upswing of the Finnish and Swedisheconomies was coming to an end, although various industries had set production records in 1913. There was nearly full employment in the both countries,the public fmance was on a sound basis and the amount of foreign debt wasvery reasonable. In 1913, Finland had a balance of trade deficit of 20 per cent,which was, however, covered by income from tourism, maintenance paymentsby the Russian army located in the Grand Duchy, and foreign debts? In sum,the economic situation was at least satisfactory when the war broke out although neither Finland nor Sweden was prepared for the consequences ofprolonged hostilities.

Production and Employment During the War

In autumn 1914, just after the outbreak of the war, economic activity in Finland and Sweden slowed down. Prices rose and orders were postponed. Consequently, some factories fired part of their workforce. However, by early1915 output revived in most industries although some structural changes tookplace. Sweden took full advantage of its neutral position; and its factories soonbegan to receive orders from both sides of the war-participating countries.The exports of metals and engineering products rose the most, coming in 1915to as much as 35% higher than in 1913. Russia’s proportion of these exportsgrew the fastest, from 13% in 1913 to 24% in 1916. In 1915-1917 the outputof mining, metallurgy and engineering was clearly higher than in 1913. Thesituation was similar in most other Swedish industries. Germany needed continuously growing amounts of foodstuffs, metals and pulp, and in exchangeSweden received machinery, chemical products and, above all, coal.5 The totalindustrial output in Sweden increased during 1915-1916. Depressed activity inbuilding construction kept the output of the stone, porcelain and glass industry under the prewar level until the early 1920s.

2 Erkki Pihkala, Finland’s Foreign Trade 1860-1917, (Helsinki: Bank of Finland1969), p. 45.

Anders Ostlind, Svensk sa,nhdllsekono,ni 1914-1922, Med sa,skild hänsyn till industn, banker och penningvàsen, (Stockholm 1945), p. 857.

Ibid.,p.234.Jan Kuuse, Foreign Trade and the Breakthrough of the Engineering Industry in

Sweden, 1890-1920,” Scandinavian Economic Histomy Review, vol. 25 (1977) no 1, pp. 1-12.

Thno Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

Insufficient foreign demand and transport difficulties prevented Swedishsawmills and the other woodworking industries from matching their prewaroutput, except in 1916.6 In addition, diplomatic frictions hampered the exportsof those products. Sweden, nevertheless, based its trade policy on the assumption that the rules of prewar international law would be respected, andneutral countries would therefore have the right to uninterrupted free trade.Its neutrality was, however, under suspicion among the Allies. Its extensivetrade with the Wilhelmian Reich and its government’s unofficial sympathiestowards the Germans were especially damaging to its trade with Britain, Dueto the fact that European countries were not able to supply Sweden with various commodities, such as grain, it made serious efforts to import them fromNorth and South America. However, from 1916 on, the British navy, followingits government’s policy, impeded this trade.

Beginning in autumn 1914 the German navy, in turn, managed to controlthe key routes in the Baltic Sea and block the access of Finnish ships to theNorth Sea. This blockade dealt a serious blow to Finnish foreign trade. Thesawmill industry, which had exported more than 90 per cent of its output toWestern Europe, suffered the most. The mills attempted to continue theiroperation by exporting more to Russia and sawing into their stocks. Nevertheless, their total output fell from 892,800 standards in 1913 to 362,100 standardsin 1916 and further to 193,300 standards in 1918. Employment in the sawmillsdecreased from 28,500 to 10,400 workers between 1913 and 1918.

At first, butter exports continued from Finland to England through theScandinavian peninsula. Due to many difficulties, the volume of butter exportsdecreased, and finally Sweden forbade the transit trade of Finnish butterthrough its territory. Increase in the exports of butter, milk, cream and cheeseto St. Petersburg compensated only partly for the fall in the trade with theWestern countries. Between 1913 and 1917, total butter exports fell by 85 percent. The exports of some minor items declined to a much less extent. Forexample, shipments of wooden spools to Britain through Sweden and Norwaycontinued up to 1916 nearly on the prewar level.8

6 Ostlind, op. cit, pp. 854-855.Timo Myllyntaus, Karl-Erik Michelsen and Timo Herranen, Teknologinen muutos

Suomen teollisuudessa 1885-1920, (Tammisaari: The Finnish Society of Sciences andLetters 1986), pp. 244-246; Myllyntaus,1989, op. cit., pp. 11-26, 78-79.8 Pihkala 1969, op. cit., pp. 92-93; J. Karhu, Sota-ajan taloudellinen elämä Suomessa,(Helsinki 1917), pp. 66-68; Pekka Ruuskanen, Koivikoista maailmanmarkkinoille.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 29

Thn blockade did not hit pulping and paper making as severely, becausebefore the war those industries had shipped only 20 per cent of their exportsto the West through the Baltic Sea. The demand for Finnish paper, especiallynewsprint, increased in Russia, which led to records in paper output and exports in 1916. However, in relation to the 1913 levels, the total output of thepulp and paper industries dropped in 1917 and 1918 by 24% and 57%, respectively.9

Despite unprecedented problems in both Finnish and Swedish industry in1914-1916, one can hardly regard these setbacks as catastrophic, althoughrestructuring may be too mild an expression for the changes. However, thesituation drastically worsened in Finland in 1917, and the change can be noticed even if overall output figures, such as in Table 1, do not reveal big differences between industries. During the first war years, the Russian statesupported employment in Finland. In January 1917, about 42,000 Finns wereworking in factories producing war materials for the Russian army, another30,000 men were employed in the construction of military fortifications and afew thousand were engaged in the maintenance of 125,000 Russian soldiers invarious parts of Finland.’0After the February Revolution in Russia, the orders of war materials diminished substantially and the construction of fortifications was discontinued.’1

A wave of strikes ensued and soon, in late April 1917, most factory workers and railwaymen had achieved the main goal of their industrial action, theeight-hour workday. After the snow had melted in May, farm hands and timber floaters also went on strike. Strikes demanding primarily shorter workingdays and higher wages became increasingly political in autumn 1917. Due tothe general strike in November, nearly half a million working days or 1.6% ofthe annual workdays were lost; however, under pressure, the Finnish Parliament legislated the general eight-hour working day. Nevertheless, politicaltension did not abate. In autumn 1917 Finland was simultaneously hit by un

Suonien rullateollisuus vuosina 1873-1972, Studia Historica Jyväskylaensia 45,(Jyvaskylh, 1992), pp. 411-418.

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF) L4:33-40 Handel [Foreign Trade] 1913-1920(Helsinki: Statistical Centre 1914-1922); H. Boissaux, Les bois de Finlande, (Paris,1926); Myllyntaus et al., 1986., op. cit., p. 256; Myllyntaus, 1989, pp. 27-44.10 Matti Nhrhi, op. cit., pp. 16 1-180.

Tinio Herranen and Timo Myllyntaus, Effects of the First World War on theEngineering Industries of Estonia and Finland,” Scandinavian Economic History Review, vol. 32 (1984) no 3, pp. 121-142.

30 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

employment, strikes, soaring inflation and hunger. One and a half monthsafter the Parliament had proclaimed Finland an independent state on December 6, the situation turned even worse: the Civil War broke out, hundreds offactories were closed and 3.3 million working days — more than 10% of theannual work input — was lost. In 1918 the industrial output accounted onlyfor 46% of the prewar level.

Statistics on the changes in the industrial production of wartime Swedenare ambiguous; according to the older data, a considerable decline occurred in1918, but the latest research claims that there was no wartime decline at all inthe Swedish industrial output, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Industrial Output and Gross Domestic Product in Finland andSweden, 1914-1924 (Indices with the base year 1913=100)

Industrial output GDPFinland* Sweden Sweden Finland Sweden

Lindahi SchOn#1 2

95 97 99 96 991915 92 104 108 91 991916 102 109 119 92 981917 74 91 111 77 861918 46 76 100 67 851919 68 84 101 81 891920 89 96 104 91 951921 89 75 87 94 911922 106 87 97 103 1001923 125 96 108 111 1051924 128 109 121 114 108

* Including manufacturing, handicraft and public utilities# Including mining, manufacturing and handicraft

Sources: Riitta Hjerppe, Finland’s Historical National Accounts 1860-1994, (Jyvaskyla:University of Jyvaskyla 1996), pp. 91-96, 127-129; Erik Lindahi, National Income ofSweden 1861-1930, (Stockholm 1937); Angus Maddison, Monitoring the World Econolny, 1820-1992. (Paris: OECD 1995), pp. 194-197; Lennart Schön, Industri ochhaniverk 1800-1980, (Lund 1988), pp. 301-310.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 31

In contrast, signs of a downturn were evident in Finland. The GDPgradually deteriorated after the beginning of the war, whereas in Sweden thedepression began only after the stagnation of 1914-1916. The crisis of 1917-1921 was worse in Finland than in its closest western neighbour. Nevertheless,its economy revived earlier and more briskly than the Swedish economy.

Finnish data on the output and foreign trade presented in Table 1 and 2provide a clear impression that the wartime crisis affected the foreign trademuch more heavily than the agricultural and industrial output or the totalGDP. Finnish exports fell more severely than imports during the war, butafter a deep trough in 1918, the exports began to revive and in 1922 they surpassed their prewar volume. Although for nine years (1914-1922) the annualvolume of imports remained on average below the prewar level by a third, theFinnish GDP decreased only by one eighth (12%). Obviously the Finnisheconomy had a capacity to resist the impact of trade blockade and other external effects of the crisis.

According to the available data for the years 1913-1924, imports slumpedin Sweden only for two years, 1917-1918. In contrast, Swedish exports surpassed the prewar level only in 1915-1916, and afterwards they remained 19-33 per cent below the volume of 1913. It was significant that the terms of tradefor Sweden stayed at least on the prewar level except in 1918. Therefore, highexport prices partly compensated for the fall in the shipped quantities.

Another interesting feature is that the wartime crisis affected the homemarket and export industries more than imports and the volume of householdconsumption. At the lowest point in 1918, Swedish households were able toconsume 80 per cent of the prewar level, whereas the corresponding indexfigure for the output of the main Swedish consumption industries was merely60.12 Therefore one might argue that external disturbances affected production more than consumption in Sweden. However, various population groupsencountered the consequences of the war in different ways, and the averagefigures might reflect the individual experiences of citizens rather poorly.

12 Ostlirid , op. cit., pp. 209, 439.

32 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tamaala

TABLE 2. Foreign Trade and Terms of Trade in Finland and Sweden, 1914 -

1924 (Indices with the base year 1913 = 100)

[ Volume of exports Volume of imports Terms of tradeFinland jwedezjI Finland Sweden Finland ] Sweden

1914 68 89 73 91 97 1021915 47 138 72 116 82 981916 48 134 85 102 112 1131917 29 76 48 52 77 1181918 11 65 13 55 56 911919 51 67 66 128 57 991920 77 76 58 158 78 1111921 72 59 51 98 87 1291922 102 81 68 114 97 1161923 108 80 93 107 1171924 124 96 99 98 113

Sources: Gunnar Fridlizius, “Sweden’s Exports 1850-1960,’ Economy and Histoiy vol. 6(1963) no 1, 89-91; Riitta Hjerppe, Finland’s Historical National Accounts 1860-1994,(iyvaskyla: University of Jyväskyla 1996); Angus Maddison, Phases of Capitalist Development, (New York: Oxford University Press 1982); Erkki Pihkala, Suomen ulkomaankauppa 1860-1917, (Helsinki: Bank of Finland 1969); Helkki Oksanen - ErkkiPthkala, Suomen ulkomaankauppa 191 7-1949, (Helsinki: Bank of Finland 1975); Anders Ostlind, Svensk samhällsekonomi 1914-1922, (Stockholm 1945).

Food Supply: Shortages, Rationing and Social Unrest

As cheap grain from other continents started to flood the European marketsfrom the late 19th century onwards, Swedish and Finnish farmers reacted bybeginning to concentrate on the more profitable animal husbandry. By 1914the inflow of cheap foreign grain had distorted the structure of agriculture, atleast concerning the countries’ self-sufficiency of foodstuffs. Before the war,Finland imported 60% of the bread cereals it consumed, and Sweden roughly30%.13 Despite the evident need, neither of the two countries succeeded in

13 Heikki Rantatupa, Elinta,vikehuolto ja -saannöstely Suomessa vuosina 1914-1921,(Jyvaskyla 1979), p. 35; Carl Mannerfelt, “Livsmedelspolitik och livsmedelforsorjning1914-1922, Bidrag till Sveriges Ekonomiska och soda/a historia under och efter vãrldskriget, Ed. Eli F. Heckscher, (Stockholm 1926), p. 46.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 33

increasing its production during the war. In Finland, the weather was normaland the crops were therefore stable, being mediocre at best compared withthe prewar level, in the first war years, the total agricultural output accountedfor approximately 95% of the production in 1913, the lowest point being 89%in 1918.14

The development in Sweden was altogether more complicated. Afready in1916 the crop was modest, and the following year Sweden faced its worst cropfailure since 1867. The harvest of bread cereals amounted to only 60% of theaverage for the years 1911-1915. Bad weather was the primary cause of thefailure, but lack of fertilisers had its effects as well.’5 On the top of this, thecultivation of bread cereals had decreased in Sweden because animal husbandry had become more profitable due to price policies and the lucrativeGerman trade. During the first wartime years, dairy products and meat playedan important role in the trade between Sweden and Germany, and thereforethe government issued few export or price restrictions on them. This encouraged the farmers to expand livestock production at the expense of bread cereal cultivation, and thus Sweden’s level of self-sufficiency actually deteriorated during the war.16 In comparison, the state of the Finnish agriculture wasmore stable. Being less developed, it was less dependent on foreign fertilisers,machinery and fuels, but also less productive.17 Secondly, the price development of vegetable products compared with that of animal products was moresymmetric, thus no great structural changes occurred in the agricultural output.

As a result, bread grain imports were needed in both countries throughoutthe war. Sweden imported grain from America, and Finland from Russia.Sufficient amounts were obtained until the winter of 1916/17, when the tightening the trade relations with Britain and Germany’s unrestricted submarinecampaign cut off Swedish foreign trade, whereas internal problems in Russia

14 Leo Harmaja, Maailmansodan vaikutus Suomen taloudelliseen kehitykseen,(Helsinki 1940), pp. 25-26; Riitta Hjerppe, Finland’s Historical National Accounts,(Jyvaskylä 1996), p. 125.15 Mannerfelt, op. cit., pp. 54-55; Arthur Montgomery, Svensk och intemationellekonomi 1913-1939, (Malmö 1954), pp. 123-124; Edelgard Lohmeyer, Die schwedischeLebensrnittelpolitik im Kriege, Nordische Studien IV, (Greifswald 1922), pp. 42-61.16 Mannerfelt, op. cit., pp. 60-61; Nystrom, op. cit., pp. 34-37.17 Harmaja 1940, op. cit., pp. 60-65.

34 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

gradually diminished deliveries to Finland.’8 For the last two wartime yearsand even thereafter, both the Finnish and Swedish governments made growingefforts to purchase enough bread cereals from abroad. Nevertheless, as Table3 shows, these efforts fell far short. A drastic change of policy was inevitableto ensure a rational use and impartial distribution of existing supplies.

TABLE 3. The Harvests and Imports of Cereals in Finland and Sweden,1913 -1919

Sweden Finland

Imports Harvest* Imports Harvest*

tons index tons index tons index tons index

1913 514 042 100 3 033 000 100 437 198 100 758 805 1001914 387 159 75 2 238 000 74 300 075 69 725 572 961915 602128 117 2814000 93 359339 82 816405 1081916 354483 69 2742000 90 412791 94 744780 981917 151049 29 2028000 67 47618 11 653640 861918 111705 22 2231000 74 10693 2 654108 861919 258 460 50 2 714 000 89 241 146 55 676 593 89

*Wheat lye, barley, oats, mixed grain, peas and beans.

Sources: Historisk statistik for Sveiige (Stockholm 1960); OSF IA: 33-39, Foreign TradeStatistics 1913-1919, (Helsinki 1914-1921); Suomen galoushistoria 3, Compiled byKaarina Vattula, (Helsinki 1983).

In addition to the principles laid down by the foreign trade policy, theSwedish food policy during the first wartime years consisted almost solely ofprice regulation. Unlike in many other European countries at the time, officialmaximum prices were not even issued before 1916. Through various agreements with millers’ and bakers’ associations and the monopoly of cereal im

18 From the outbreak of the war, Britain with its naval superiority attempted to interdict supplies to Germany, whereas the German navy were able to control the tradein the Baltic Sea and at the beginning of 1917, the Wilhemian Reich extended its U-boat attacks against the merchant ships of the neutral states. Edward L. Killham, TheNordic Way, A Path to Baltic Equilibrium (Washington, DC: Compass Press, 1993), pp.41-46.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 35

ports, the Swedish government managed to keep the price level of vegetablefoodstuffs reasonably low. The restrictions on animal foodstuffs were lessstrict, and so their prices rose continuously.

As a result, the lower income groups were forced to change the structureof their consumption towards vegetable foodstuffs. General rationing becamea necessity as importation grew more difficult. The Swedish government introduced a rationing card system for sugar as early as in October 1916 andone for bread followed in January 1917. Gradually during 1917 rationing cardsfor grain, peas, coffee, flour and butter were issued, and also a card for diverse items. Imports, exports and price regulation remained important in thefood policy, but the main functions were now rationing and distribution.’9

In Finland, maximum prices for foodstuffs were introduced quickly afterthe outbreak of the war. However according to the Russian policy, theseprices were set regionally by the governors, which, due to the different pricelevels, led to widespread speculation. As transport restrictions for foodstuffsdid little to improve the situation, the Finnish government issued nationalmaximum prices in 1916, first for sugar and then for meat, cereal and dairyproducts. At first, the regulation system seemed to work appropriately, but asimports from Russia started to stagnate, while the demand for cereals andother foodstuffs rose, discontent with the food policy grew. For some productsthe official prices had to be set to correspond with the market prices just tokeep the commodity available, as for others the market prices increased to thepoint that the products disappeared into the black market altogether. As imports from Russia ceased, a general rationing had to be adopted in Finland,too. Rationing cards for sugar were issued afready in December 1916, andbread tickets during the summer of 1917. Cities and other densely populatedareas adopted cards for meat and dairy products during the spring.20

As Finland used the Swedish system as an example for organising its ownrationing, both countries faced many similar problems during the last waryears. Firstly, the collecting and distribution of domestic crops proved difficult. In the initial phase, the Swedish government had estimated the breadgrain crop of 1916 to be 200,000 tons bigger than it was finally in the reportsgiven by the farmers. Consequently, the daily rations were reduced from 250grams to 200 grams per person in February 1917 - one month after the intro

19 Mannerfelt, op. cii., pp. 60-61; Ostlind, op. cit., p. 213.20 Rantatupa, op. cit., pp. 26-84.

36 Timo Myllyntaus & Rerik Tamaala

duction of the rationing system. As the situation worsened, further reductionswere made in April 1917 and early 191.8. 21

Finland faced similar problems, and the rations were decreased numeroustimes, the lowest point being less than 100 g per day in the summer of 1918?In both countries the population was divided into self-sufficient and ‘card-households. The self-sufficient producers were allowed to keep a certainportion of the crop for personal consumption and as seed grain. At the beginning of the rationing, the ratio of producer and card-households’ was 1:1in both countries, but the proportion of card-holders grew constantly as thewar went on.23 In both countries rural people were better off than city-dwellers, since in the countryside food could be bought directly from the producers. The rationing was organised by regional rationing committees, whichwere in charge of collecting and distributing of the area’s own cereals and oftransporting any surplus production. With fairly free hands the committeesoften held on jealously to the region’s own cereals; consequently, cities wereleft to manage with what little could be had. The official card rations could besomewhat deceiving, since in the cities at times there was so little bread thatthe actual rations distributed fell short of the official ones. Buying from theblack market was one option, at least for the well-to-do, another was to travelto the countryside to buy food.24

In both countries the rationing of bread and bread grain constituted thebackbone of the whole system. On the official markets, other foodstuffs wereavailable more irregularly, if at all. It has been said that bread and potatoeskept the lower income groups alive through the crisis. Therefore, when shortages in these commodities coincided with other factors, social unrest occurredin both Finland and Sweden. In Sweden, demonstrations and riots broke outduring the spring of 1917. The newly introduced rationing system had its difficulties and more importantly the potato crop had failed in the previousautumn. The prices of potatoes had increased hardly at all during the firstwartime years, and now they nearly trebled between June 1916 and April1917. In spring 1917 the rations of bread was cut and potatoes disappearedfrom the legal market. However, the black market svarta bOrsen, had no difficulties to supply foodstuffs for well-off citizens. Hunger was, therefore, a

21 Mannerfelt, op. cit., pp. 101, 113; Nystrom, op. cit., pp. 47-48.Rantatupa, op. cit., p. 243.

23 Mannerfelt, op. cit., p. 103; Rantatupa, op. cit., p. 78.24 Pertti Haapala, Kun yhteiskunta hajosi. Suomi 1914-1920 (Helsinki: Edita 1995),pp. 208-212.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 37

problem of the poor, who could not pay high prises demanded by illegaltradesmen. Rumours that farmers, lacking fodder, fed potatoes and rye totheir hvestock added to the bitterness, The scarcity of food coincided with thefeeling of political and social injustice felt by the working classes. The socialdemocrats launched the demand for the eight-hour working day and the genera! and equal right to vote in the parliamentary elections. The political leftaw the conservative government led by Hjalmar Hammarskjöld both as anobstacle to the advance of democracy and equal political rights, and throughits export-oriented trade policy as the main cause of the food shortage andhigh prices.26 The significance of the Swedish foodstuffs exports were alsoemphasised by a contemporary German observer. He claimed that the Swedish foodstuffs shortage did not attribute so much to the British blockade as to“hungry German tradesmen’ who seized from Sweden “everything that wasnot fastened with rivets or nails.”27

Hunger demonstrations occurred all over southern and central easternSweden, especially in smaller cities which due to weak transport connectionswere poorly supplied. According to a study of newspaper accounts by HansNystrom, a total of 146 hunger demonstrations of different kinds (includingmeetings, marches and riots) were reported between the beginning of Apriland mid-May 1917. Well over 300,000 demonstrators, many of them women,took part. The demonstrations were concentrated in the industrial areas, andoften a strike was connected to the demonstration. In some cases, direct action was taken by the demonstrators. The workers in some districts confiscated stored foodstuffs and distributed them, or conducted searches for concealed potatoes and grains. Even in Stockholm both left-wing and right-wingparamilitary civil guards armed with pistols were formed, while radical juniorseamen and female demonstrators were confronted with armed police and

BjUrn Elmbrant, “Hungermarschen i Adalen 1917,” Meddelande frô.n atheta,rörelsens arkiv och bibliotek (1979) no 9, pp. 6-29.26 Sune Garpenby, Hungempproret I Väster.’ik 191Z Narfolket tog ,nakten och revolutionsfackla tdndes over v&t land, (Västervik: Ekblads 1967) pp. 1-7; Ingvar Funk,“Hungerrorelsen i Vhstervik 1917,” A,cboken, Notiser fnin arbetamas kulturhistoriskasällskap, vol. 43 (1969), pp. 3-45.27 Moreover, in summer 1917 German U-boats sank three Swedish ships full of grainsoon after they had left English ports where the British navy had held them for somemonths. Johannes Paul, Die schwedishe Politik in: Weltk,ieg, Mitteilungen aus demNordischen Institut der Unjversität Grejfswald no 3 (Greifswald 1921), pp. 16-18.

38 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

soldiers in the city centre.28 In the background of the political unrest, therewere the current Russian revolution, the split of the Swedish social democraticparty in three fractions and then in two parties. Unfortunately, Swedish historiography provides blurred analyses on the events of the year 1917. Somehistorians claim that “in spring 1917, Sweden was on the brink of a civil war,”whereas others state that people did not - at least in Stockholm - sufferedfrom hunger and regard political disturbances only as minor and scatteredlocal incidents.29

As mentioned, the wave of hectic protests lasted until the middle of May1917.° Gradually the political tension eased and the situation calmed down.The Hammarskjöld government was forced to resign already in March. External and internal pressures were slightly mitigated by nominating the university chancellor Carl Swartz as the prime minister. Moreover with the coming of summer, the food situation improved somewhat. In October, after theelection of the second chamber, liberal Nils Eden became the prime ministerand gave four of the ten ministry portfolios to social democrats. Eden’s government (1917 -1920) was pledged to neutrality in its foreign policy andamendments in its internal policy: it aimed to improve food supply and prepare political reforms, such as the universal suffrage and the eight-hourworking day.31

In Sweden, the winter 1917/18 turned out to be even more difficult thanthe previous one, but oddly no riots worth mentioning occurred. With the cropfailure of 1917 and the imports still low, the rationing and restrictions werefurther tightened. However, by then the new Nils Eden’s government, hadalready started negotiations with the Allied Powers, which brought new hopeof receiving imports in the near future.

28 Ola Larsmo, “Svenska egalitarismen,” Ord och Bud (1995) no 1, pp. 1-5; SigurdKiockare, Svenska revolutionen 1917-18, (Tiden 1967).29 Sigurd Kiockare, “PA randen till inbOrdeskrig — Sverige 1917,” Meddelande frdnarbeta,rörelsens arkiv och bibliotek (1979) no 9, pp. 2-5; Yvonne Hirdman, Magfrtigan:Mat som mil och medel, Stockholm 1870-1920 (Kristianstad 1983), pp. 247-275.30 A new wave of political unrest took place in autumn 1917 and the Swedishauthorities were warned about “revolutionary attitudes in the army and navy.Nystrom, op. cit., pp. 10-17; Griffiths, op. cit., pp. 89-91.31 Ibid., pp. 46-55; Garpenby 1967, bc. cit., pp. 1-7; Ulf Olsson, “IndustrilandetSverige,” Avenryret Sveige. En ekonomisk och social histo,ia, Ed. Birgitta Furuhagen etal., (Stockholm 1993), pp. 73-76; Tony Griffiths, Scandinavia, (Kent Town: WakefieldPress 1991), p. 89.

Economic crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 39

Social unrest also occurred in Finland when the deterioration of the foodsituation was exacerbated by social and political tensions. Freed from theRussian strike prohibitions Finland faced a large strike wave in the spring of1917, after the February Revolution in the tsarist Empire. Later in the year,unemployment was aggravated by the ending of Russia’s war supply orders.When the social democrats lost their majority in parliament in the Octoberelection and the internal disagreements of the social democratic party becamecritical, the political tension increased further. As in Sweden, the rationingsystem had problems since its beginning. In contrast to Sweden, in Finland itwas butter, a product that had been unavailable for a long time, that triggeredthe first riots in Turku, Helsinki and another cities. In August angry mobslooted warehouses where butter was stored for export. Russian troops wereneeded to calm these spontaneous riots, but the worst was yet to come.32

Imports having ceased altogether, even bread became scarce as theautumn 1917 went on. Milk and meat had already been scarce for almost twoyears, but the bread shortage was a completely new phenomenon. Alongsideand connected to the growing tension between the working class and the political right, the food shortage played a significant role in triggering the Finnish Civil War. The hostilities between the two armed guards, the leftist‘Reds’ and the rightist ‘Whites’ began in late January 1918 when blood wasfrozen in the gutters of Helsinki.”33 A full scale warfare at short notice waspossible in Finland because both sides obtained — not only Browning pistolsas in Sweden — but also thousands of rifles, other weaponry and ammunitionfrom the disbanding Russian army. Earlier the ‘White’ guards had been declared as the armed forces of the new bourgeois government. The front lineran west to east through the south-western part of Finland, which is the economical and agricultural core of the country. The government troops held thenorthern part, and the revolting ‘Reds’ controlled the southern districts. During the war, both the ‘Red’ and the ‘White’ sides had trouble supplying of thearmy and the civilians. With previous network of regional supply committeeswas maintained on both sides, but in addition the armies had the right to confiscate supplies directly from the producers. Card rations were reduced on

32 Pentti Virrankoski, Suornen taloushistoria kaskikaudesra atorniaikaan, (Keuruu:Otava 1975), pp. 187-188.Griffiths, op. cit., p. 77.

40 Tinzo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

both sides of the frontier and finally even grain seed was used for consumption.34

With the aid of German military intervention, the ‘Whites’ finally defeatedthe ‘Reds’ in May 1918. In the war and its aftermath, thousands of lives —

according to some estimates 16,500-17,500 — were lost in military operations,terror attacks and executions. In addition, the 11,800-12,500 ‘Red’ prisoners ofwar who died in prison camps after the Civil War constituted the grimmestindicator of the catastrophic food situation in Finland. Though apparentlycasualties of various diseases are also included in this figure, it was reportedthat starvation was not an unusual cause of death. Officially, amounts according to the general card rations were distributed to the prisoners, but in realitythe supplying of the camps was harshly neglected.35 The causal connectionbetween the food shortage of the winter 1917-1918 and the outbreak of theCivil War has been widely discussed in Finnish research, and some historianseven regard the hunger crisis as the main reason for the conflict.36 After theCivil War, the food and agricultural policy was revised with a stress on increasing domestic production of bread cereals. However, the measures cametoo late to affect the crop of 1918.

During the last wartime months, the Swedish and Finnish governmentsstrained to reach agreements with foreign countries to obtain vital imports. Ithad become evident that neither could manage much longer without any imports. After surviving the hard winter, Sweden agreed with Britain in thesummer and the first cereal shipments were received in August 1918. Finland’s situation was more difficult, because in return for military aid duringthe Civil War the victorious ‘Whites’ had bound their country in close relations with Germany. During the summer of 1918 Finland received small andinadequate amounts of cereals and other foodstuffs from Germany, which wassuffering from a severe food shortage itself. The Finnish rationing system was

Rantatupa, op. cit., pp. 117-139; Haapala, op. cit, pp. 212-215.u Jaakko Paavolainen, Punainen terrori. Poliittiset väkivaltaisuudet Suomessa I,(Helsinki: Tamnu 1966); Jaakko Paaavolainen, Valkoinen tetrori. Poliittiset väkivaltaisuudet Suomessa II, (Helsinki: Tammi 1967); Veikko Huttunen, Taysivalrainenkansakunta 1 91 7-1939, Kansakunnan historia vol. 6, (Porvoo: WSOY 1968), pp. 202-203, 219-226; Haapala, op. cit., pp. 215, 241-243.36 See for example an article by Viljo Rasila, Kehitys ja sen tulokset, Suomen taloushistoria 2, Eds. Jorma Ahvenainen, Erkki Pihkala and Viljo Rasila, (Helsinki:Tammi 1982), pp. 154-167.

Rantatupa, op. cit., pp. 87-145.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 41

now far better organised than it had been the year before. Cereals, meat anddairy products were scarce, but the distribution was better planned and manysubstitute products were introduced. Nevertheless, the situation was critical inthe autumn. Famine would have hit in the spring 1919 if no imports had beenreceived before that The armistice in November 1918 did not bring instantrelief. By sea Finland was inaccessible before the spring thaw, and the Allieshad still some political matters to consider in connection with the RussianBolsheviks. During the winter, the Allies included Finland in their aid programme, and fmally in February 1919 it was considered a neutral country andentitled to receive their food deliveries. Due to organisational difficulties andthe danger of mine fields in the Baltic Sea, some cities still faced some short-term shortages during the spring, but on the whole, a famine was avoided.38

Sweden abolished all restrictions and rationing laws concerning foodstuffsas quickly as possible. The last item to be freed from rationing was bread inAugust 1919. Finland, however, retained the restrictions much longer thanfrom the standpoint of the consumers. The Finnish government wanted tocontrol the national debt and the value of the Finnish markka. Therefore, thewhole foreign trade, foodstuffs included, was kept under strict control. Finally,cereals and sugar were freed from restrictions in the beginning of 1921.

Plunge in Fuel Imports: The First Energy Crises

Before industrialisation, Finland and Sweden were in a fortunate position dueto exceptionally abundant indigenous energy resources. In respect to thestanding stock of forests in Europe, only Russia surpassed them. Their hydropower resources were also significant and their peat reserves were enough tomeet their energy needs for several hundreds years. Prior to World War I,peat was, nevertheless, used negligibly as an energy source. With firewood andhydropower, Finland especially was able to attain a fairly high rate of self-sufficiency. Sweden, in turn, relied more on indigenous hydroelectric powerand imported fuels. In 1913, the self-sufficiency rate of the total Finnish energy supply was about 92 per cent, whereas in Sweden, the rate was approximately 57 per cent. Correspondingly, Finland could cover about 90 per cent ofits fuel needs by indigenous fuels and Sweden only 40 per cent.

38 Mannerfelt, op. cit., p. 118; Rantatupa, op. cit., pp. 218-222.Mannerfek, op. cit., p. 120; Rantatupa, op. cit., pp. 232-235.

40 Erik Blomqvist, Sveriges enemgifomorjning, Andra upplagan, (Stockholm 1957), pp.86-88.

42 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaola

The use of coal had increased quite rapidly in both countries from theearly 1890s. Coal was used mainly in railway locomotives, steamships, gas-works, ironworks and some other industries, such as sugar factories, and insome quantities for space heating. Oil was mainly consumed for lighting. Theconsumption of stationary petroleum engines and motor traffic was then fairlysmall. Electrification was in progress. Practically all town centres in bothcountries had been electrified by July 1914. At that time, about a tenth of therural households in Sweden had been wired for electricity; by 1920 electrification had progressed rapidly to the point that every third household in thecountryside were supplied with electric power. In Finland, rural electrificationwas, in contrast, just beginning. In addition, the strategy of electrification wasat the time changing from thermal power plants to hydropower plants. Also,in this respect, Sweden was ahead of Finland. For example, in 1909 it hadopened a large state-owned hydroelectric power plant at Trollhättan and thekingdom generated almost twelve times more hydroelectricity than its easternneighbour.41

Despite high self-sufficiency, the Great War caused the first energy crisis -

in the modern sense - both in Finland and Sweden. During the decades preceding the war, mostly due to quick industrialisation, both countries had become more dependent on imported fuels than had been expected. As importation became more difficult, the crucial question of the crisis emerged: howmuch of the demand could be covered by indigenous energy sources and howeffectively this could be organised.

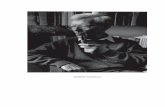

Before the war, Finland had imported coal mainly from England. In 1913the imports of coal and coke rose to almost 600,000 tons. The war affectedimports immediately and already in 1914 they were only 39% of the level in1913, decreasing to an average of 2% in 1915-1916, and rising only to less than6% in 1918-1919, as shown in Figure 1.42 Because the German navy hadblocked the trade routes from the west, Finland had to purchase all of itsfossil fuels from Russia. The small amounts of coal and coke imported fromRussia were primarily reserved for the factories producing war materials. Formost other factories as well as for space heating and locomotives, firewoodwas used as a substitute. This quickly led to a firewood shortage and as the

41 Statistisk översikt av det svenska naringslivets utveckling âren 1870-1915, StatistiskaMeddelanden, Series AIII:1, (Stockholm, 1919), pp. 35-36; Timo Myllyntaus, Electnfying Finland, The Transfer of a New Technology into a Late Industtialising Economy,(London: Macmillan 1991), pp. 247-253.42 OSFIA:33-40 [Foreign Trade] 1913-1 920, op. cit.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 19144924 43

160

80

60

40

20

0

FIGURE 1. Imports of Fossil Fuels to Finland and Sweden, 1913-1924

140

120

—: 100

1913 1915 1917 1919 1921 1923

Sources: Komme,iella meddelanden 10/1920 pp 544-552, OSF IA: 33-44 Foreign Trade(Helsinki, 1914-1926); SveHges officiella statistik. Handel 1913-1924, (Stockholm, 1914-1925).

demand for billets grew, their prices also rose. In major cities, their priceswent up quicker than other prices and quadrupled between 1913 and July1917. Only from autumn 1917 to 1920, the prices of billets rose somewhatslower than the cost of living in general43.On the whole, the coal shortageexperienced from the very beginning of the war had little effect, since theenergy systems in industry, the transport and space heating were fairly easilyconverted to use firewood as a substitute. In contrast, urban gasworks in Helsinki, Turku and Vilpuri encountered the most serious difficulties, becausetheir technical equipment was not so easily convertible.

In Finland, the beginning of the war had no dramatic impact on the supplyof liquid fuels, which had been imported from Russia even before the war and

‘ Annuaire statistique de Finlande 1921, (Helsinki: Bureau central de statistique deFinlande, 1921).

Myllyntaus, 1991, op. cit., pp. 72-74.

44 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tamaala

were still obtained in sufficient amounts during the first wartime years. In1914-1917 the imports of liquid fuels on average remained at a level corresponding to 80 per cent of the imports in 1913. In 1918 they suddenly sank to

Despite these figures, the reduced imports of petrol and paraffm oil,together with distribution problems and price increases, led to a lighting crisislong before the collapse in 1918. Rumours of shortages led to hoarding andspeculation, which worsened the situation further. The lighting crisis affectedmostly the countryside where the paraffm oil lamp was still the most commonilluminant. A sudden drop in imports of liquid fuels after the Russian OctoberRevolution threatened to darken the rural areas and consequently more thana half of all households. In 1918 the price of paraffin oil experienced a steeperincrease than any other necessity. By May it had completely disappeared fromlegal trade. Substitutes were difficult to find. The domestic production ofcandles was not large enough to satisfy the demand, and their prices were veryhigh. The Finnish government made some efforts to make carbide and turpentine lamps and their fuels more easily available, but these procedurescame too late and were effective only when the real crisis was already over.The government measures to solve the problem were in vain, since already in1919 the lamp oil imports rose higher than they had been in 1913.

At the outbreak of the war, Sweden was far more dependent on importedcoal than Finland. In 1913 Sweden imported 5.4 million tons of coal, nearly 10times the amount of the Finnish coal imports the same year. Indigenous coalaccounted for 6.5% of the consumption in 1913, and the ratio stayed approximately the same until 1917. Before the war 90% of the coal imported intoSweden came from England, and less than 10% from Germany. Unlike Finland, Sweden managed to keep up its coal imports during the first wartimeyears and in 1916 imports even rose 15% higher than they had been in 1913.One result of the war was that the balance of import volumes between theprewar trading partners changed. Because Sweden obtained ever diminishingamounts of coal from England, which needed it for the war effort, closer connections were made with German suppliers. In 1916 73% of the averagemonthly coal imports came from Germany. As imported fuels were available,Sweden saw no reason for rationing them. Furthermore, the country obviously

OSFL4:33-40, op. cit.‘ Myllyntaus, 1991, op. cit., pp. 74-78.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 45

had some coal stored, since in 1914 and 1915 the quantities consumed surpassed those imported.47

At first Germany’s trade blockade and submarine attacks against ships ofueutral states, which started in the beginning of 1917, threatened to paralyseSwedish industry. By March 1917 the monthly imports of coal had sunk to amere 15% of the monthly average of the preceding year. The Swedish government fearing that the coal imports would cease altogether, began a massive project to purchase enough firewood to supply the factories and transportfhdiities with substitute fuel, The fuel commission, organised for the purpose,made calculations on the amounts of firewood needed, assuming that all imports would cease and industrial production would not decrease. As it turnedout, imports began to increase gradually at the end of the summer of 1917, thebulk still coming from Germany. Although the quantities obtained weresmaller than during the preceding years, still in 1918 the imports rose to morethan 50% of the level in 1913. Despite this, the fuel commission proceededwith the firewood plan. Between the summer of 1917 and the summer of 1918,the government purchased 20 million m3 of firewood, of which it succeeded inselling only 6.5 miffion m3 to factories and individual consumers during thesame time period. Apparently, the wood was not dry enough, and more importantly, it was expensive. Organising and storing the purchases had beencostly, and furthermore the government policy was to sell cheaper to the individual consumers and more expensively to the industries. Thus, the industriesbought the wood they needed from less expensive sources. Right after thewar, the government was fmally forced to sell at a low price the huge amountsof wood it had stored.

The situation was somewhat similar with liquid fuels. Because importswere obtained fairly easily until the end of 1916, no large-scale rationing orstoring was required. At the beginning of 1917, when foreign trade began tostagnate, a nation-wide inventory of mineral oils was conducted. According tothis inventory, the country’s lamp oil supplies would cover two months ofnormal consumption, and twice that long, if rationed. As in Finland, the government took action to obtain substitutes. However as far as carbide, the mainsubstitute, was concerned, some of it had to be saved for the production ofequally vital fertilisers. The lighting crisis struck the Swedish countryside during the winter of 1917-1918, so to avoid an even worse’ shortage the next win

‘ Komme,riel1a ineddelanden 10/1929, (Stockholm 1929), pp. 544-552.48 Montgomery, op. cit., pp.129-131.

46 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tamaala

ter, the government made considerable efforts to increase the production ofcarbide during 1918. Nevertheless, Sweden was on the brink of another severelighting crisis when the importation of foreign lamp oils resumed in December 1918.

Viewing the complete energy situation in Finland and Sweden during thewar, many similar tendencies can be pointed out. Firstly, the seemingly dramatic changes in the imports of coal did not cause any severe crises after all.The Finnish coal imports dropped to a mere fraction of the prewar level, andyet there was no corresponding decrease in the volume of industrial production. Apparently, the industries adapted fairly easily to the use of substitutefuels, and furthermore, in Finland the use of coal was not as widespread as itwas in Sweden. As for Sweden, the reduction of imports in 1917 did not leadto as many hardships as the government had estimated. The Swedish wereable to keep their coal imports at roughly 50% of the prewar level, whichproved sufficient, since substitute wood fuel was available. In retrospect, thegovernment’s firewood purchasing programme seems a clear overreaction tothe situation, but it must be kept in mind that at the time there was no certainty how long the coal imports would continue.50

Secondly, the lighting oil shortage was of a more general nature, since ittouched directly most of the population. Like the food shortage, the fear ofcold, dark homes had a strong psychological effect. The reaction to the firstenergy crisis was similar in both countries. As foreign fuels grew scarce andexpensive, electricity became ever more attractive. Its relative price was decreasing and it could not vanish from the official markets to be sold at illicitprices. Due to the short-term nature of the crisis in both Finland and Sweden,electrification could not have offered an instant solution, although somepoorly built and uneconomical utilities were constructed in haste. However,on the whole the crisis of the World War I showed the benefits of vast electrification and thus affected future energy policies in both countries.51

Inflation, Gold Standard and Other Monetary Issues

Despite many, especially historical similarities, monetary development inFinland and Sweden in the period 1914-1924 was quite contrasting. Various

‘ Olof Edström, “Industrien och dess reglering 1914-1923,” Bidrag till Sverigesekonomiska och social hisroria, Ed. Eli F. Heckscher, (Stockholm 1926), pp. 175-195.

Erik Lindahi, National Income of Sweden, 1861-1930 (Stockholm, 1937).51 Myllyntaus 1991, op. cit., pp. 76-78.

Economic C,ises in Finland and Sweden, 19144924 47

economic, political and societal phenomena had a strong impact on monetary

issues, in which the general state of the countries was crystallised,In the prewar years, the monetary system in both countries was on a sound

basis. The Swedish, Riksbank, one of the oldest central banks, has been astate-owned bank from the very beginning, but still it cannot be regarded as a

bank of the central government. By the late 19th century, Riksbank had quite

uniquely become the Diet’s bank, i.e. entirely controlled by Parliament. Theintroduction of the gold standard in 1873 and the inclusion of this standard in

the Swedish Constitution finally brought order into the Swedish monetary

system. At the same time, the Swedish krona was joined to the Scandinavian

Monetary Union with the Danish crown. Two years later, the Norwegian

crown also entered the Union. All three crowns had an identical value, 1/2480of one kilogram of pure gold. The Union made crowns practically a commoncurrency in Scandinavia. Both gold currency and token money were legal tender in all three countries.52

While nineteenth-century Sweden was aligning its monetary system withthose of its neighbours, Finland was struggling to establish its own, independent system. The Bank of Finland, the central bank of the autonomous GrandDuchy controlled by the Finnish Diet, was established in the former capital,Turku (Abo) in 1811. At the time, both Russian and Swedish bank notes werelegal tender in the country. In the 1840s, the Russian rouble completely replaced the Swedish currency. In 1860 Finland established its own monetarysystem, and the value of its basic monetary unit, the silver markka was aquarter of the rouble’s value. In 1877/78 when markka was moved from thesilver standard to the gold standard and given the same value as the Frenchfranc, its dependence on the value of the Russian rouble ceased. Russia didnot adopt the gold standard until 1893.

In the prewar years, the central banks of both Finland and Sweden had aquite independent position in monetary and fmancial policy. Due to the goldstandard, the internal value of the national currency remained fairly stableand foreign exchanges could fluctuate only within narrow limits. The centralbanks only occasionally granted loans to the central governments. The outbreak of the Great War shocked monetary markets in both countries. The

52 Eli F. Heckscher, Kurt Bergendal, Wilhelm Keilhau, Einar Cohn, ThorsteinThosteinsson, Sweden, Norway, Denmwlc and Iceland in the World War, (New Haven:Yale University Press 1930), pp. 129-169.

Heimer Bjorkqvist, Guldrnyntfotens inforande I Finland dren 1877-1878, Publications series. B:13 (Helsingfors: Bank of Finland 1953), pp. 82-84, 212-249.

Tinzo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

first reactions in Sweden were more chaotic than in Finland. The Swedishprivate banks were closed for a short time, whereas the stock exchange interrupted its operations from the outbreak of war to November 1914. in August,the Riksbank; which called its gold reserves ‘the fmancial backbone of thecountry’, made bank notes inconvertible upon gold and prohibited gold exports. When both Denmark and Norway followed suit by making similar decisions a few days later, the Scandinavian Monetary Union began its gradualdisintegration. The introduction of paper money, however, caused no markeddevaluation of the Swedish crown.

The outbreak of the war upset the Finns, too. The public, fearing for thesafety of its money, rushed to withdraw its bank deposits, and bank notes werepresented at the Bank of Finland for redemption in gold. The first anxietycaused no lasting injury to the Finnish fmancial and credit institutions. Withina few weeks, the public queued to redeposit its savings, and the gold reservesof the Bank of Finland reached a new high point.

As early as 27 July 1914, Russia prohibited the conversion of bank notesinto gold. Within a fortnight, Germany and France made a similar decisionand banned gold exports. Even before the war, Italy had retreated from thatoption and during the war Britain made the option increasingly difficult forthe public.54 Being an exception was not Finland’s intention. The Finns proposed to suspend the gold payments. However, due to disagreements with theFinnish institutions, the Russian authorities decided to continue the gold standard of the Finnish markka up to April 1915. The procedure concerning thetransition to paper money violated the independence of the Finnish Parliament, the Bank of Finland and the Finnish government, because these institutions could not determine the exchange rate of the rouble to the Finnishmarkka according to the rates in the international markets. Consequently, theRussian government decided that the Finnish public institutions were obligedto exchange roubles at rates fixed nearly to its par value. In this way the Russian administration bound the markka to the rouble up to 1917. The markeddeterioration of the exchange rates for the paper rouble also triggered thedevaluation of the Finnish markka. At the same time, some earlier decisionsaiming to russit’ Finland came in force into their full severity. For example, in

Gerd Hardach, The Fi,st World War 1914-1918, The Pelican History of WorldEconomy in the Twentieth Century, (Harmondsworth: Pelican 1987), p. 140.

Leo Harmaja, Effects of the War on Economic and Social Life in Finland, Economic and Social History of the World War, (New Haven: Yale University Press 1933),pp. 44-45.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 49

the 1890s the Russian authorities had decided that the rouble was legal tender

in payments for public Finnish services, such as a post and customs offices,

railways etc. During the gold standard, that decision did not cause significant

economic losses to the Grand Duchy, although it was a political nuisance for

the Finns. After April 1915, however, payments in overvalued paper roublesdamaged the balance of the Finnish state budget.

At the same time when the internal and external value of the Finnishmarkka began to fall steeply, the Swedish krona was moving in an oppositedirection, In 1915 the Swedish krona appreciated in relation to almost all foreign currencies, and acquired the position of a currency that stood highest, ascompared with parity among those quoted in Stockholm’.56As a consequence,

the gold standard was nominally re-established in 1916. The main reason for

this was the excess of Swedish exports compared with imports. In 1915 anoutstanding war boom started. Swedish industry worked at full capacity tomeet increasing foreign demand. Sweden exported manufactured goods toboth sides: iron, steel, pulp and foodstuffs to Germany, machinery to Russia,and sawn timber, pulp and paper to Britain.

Unparalleled success in exports caused unprecedented economic problemsto the Swedish economy. The tremendous influx of gold and foreign currencies in payment for the Swedish exports caused the internal value of the crownto sink. In addition, the prewar laws obliged the Central Bank and the Mint toaccept imported gold and mint it into Swedish gold coins, if required. With anew law of February 1916, these institutions were released from this obligation. “The embargo upon gold, consequently, was not a prohibition of importbut only an exemption of the Riksbank and the Royal Mint from the duty ofintroducing imported gold into the Swedish monetary system.”57 In spring1916, Denmark and Norway also gave up free minting and closed theirboundaries to gold. These decisions meant additional steps towards the liquidation of the Scandinavian Monetary Union. The introduction of the goldembargo, did not, however, prevent the fall in the internal value of the Swedishkrona.

Despite inflation, the war boom continued in the Swedish economy. In1916 the industrial output grew by 9% compared to the 1913 level, and thisresult was not matched again until 1925.58 In 1916, grain production experi

56 Heckscher et a!. 1930, op. cit., p. 170.Heckscher et at. 1930, op. cit., p. 190.According to Lindahl’s index, see Table 1.

50 Tirno Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

enced a setback, whereas animal husbandry and dairy production succeeded

somewhat better.59

FIGURE 2. Wholesale Price indices and Exchange Rates to U.S. Dollar in

Finland and Sweden, 19134924 (The base year 1913 = 100)

1300 —

1200 T1NLAND, WPI1100 — - SWEDEN, WPI

1Io::;SiE:=1913 1915 1917 1919 1921 1923

The Swedish index by Karl Amark and G. Silverstolpe

Sources: Riitta Hjerppe, Finland’s National Accounts 1860-1996, (Jyvaskyla 1996);Erkki Pthkala, Finland’s Foiign Trade 1860-1917, (Helsinki: Bank of Finland 1969),46; Statistisk &xbok for Sverige 1924, (Stockholm 1925); Jaakko Autio: Valuuttaku,ssitSuo,nessa 1864-1991, Suomen Pankin keskustelualoitteita 1/92, (Helsinki 1991); Statistisk âisbok for Sverige 1924, op. cit.; Komme,iella meddelanden 1925, op. cit.

Due to the German blockade of the Baltic Sea during 1914-1917, Finlandtraded only with Russia, Sweden and Norway. The deficit of exports causedimbalances in the monetary system, too. In 1916, Finnish paper mills achieved

a record in exports of paper to Russia, and shipyards and engineering work

shops exported ships, weapons and other military equipment. These exportswere paid for in paper roubles, which unfortunately suffered from rapid inflation. The influx of weak roubles dragged downwards both the internal and

Heckscher eta!. 1930, op. cit., p. 200.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 51

external value of the Finnish markka. After Finland abandoned the gold stan

dard in 1915 inflation was clearly faster than in Sweden, as shown in Figure 2.Inflation became a major economic and social problem in wartime Fin

land, and such it remained even after political independence was achieved in

December 1917 and markka was disconnected from its forced exchange rate

to the rouble. In the late 1910s, no western country - not even Germany -

experienced such rapid inflation as Finland.60 When inflation slowed down in

1921, the nominal price level was almost 12 times higher than before the war.

Such an enormous deterioration in the internal value of the markka meant a

considerable redistribution of wealth and income. People with bank deposits

or cash in their possession lost a great deal of their capital, whereas debtors

benefited from depreciating money. Workers found that their standard of

living was decreasing when prices rose more rapidly than their wages. Civil

servants suffered most severely, as in real terms, their salaries first fell andthen were hardly increased at all for many years. Compared to the other employees, the high civil servants experienced the greatest drop in their wartime

living standards and some of them found that the purchasing power of theirincome had nearly halved. A plenty of high ranking officials did not find anyother way out but cut their costs, fire some of their personal servants and inextreme cases, move to smaller and less expensive dwellings.

However, economic instability did not lead to widespread unemploymentbefore 1917, although thousands of Finns had to change their jobs and eventheir occupation, leaving, for example, jobs as sawmill workers to becomeconstruction workers at the military fortifications.

In early 1917, the war boom ended in Sweden and the economic situationturned worse in Finland as well. Compared with all the currencies exchangedin Stockholm in April 1917, the Swedish krona was the most highly valued inrelation to the former gold parity, and it remained at a premium up to thearmistice in November 1918, when it began to lose its strength in proportionto the U.S. dollar, British sterling and French franc.6’ In contrast, since theoutbreak of the war the Finnish markka had steadily weakened compared withthe U.S. dollar. By 1918 it had lost about 60 per cent of its prewar value andits depreciation accelerated enormously between 1918 and 1921, as indicatedin Figure 2.

60 Between 1 January 1914 and 1 October 1917, the Russian wholesale index soaredfrom 100 to 1171. Pthkala 1969, op. cit., p. 46.61 Ostlind, op. cit., pp. 23-24.

52 Tinio Myllyntaus & Eerik Tarnaala

In 1917 sharp cuts in foreign trade constituted one of the major economicchanges in the Swedish economy. In the beginning of that year, Germanystarted unrestricted submarine warfare against Sweden and other neutralcountries. The Allies’ embargo on trade with Germany also hit the suppliesfor Sweden harder than at any time before or after. After the FebruaryRevolution in 1917, Russia ceased its orders of weaponry and machinery fromboth Finland and Sweden. Nevertheless, the drop in Swedish imports was evenmore marked than in exports. In terms of the total value, the Swedish importsaccounted for roughly half (56%) of its exports. Still, the excess of exports inthe early war years led to an influx of capital with a value of 760 millioncrowns, which was a huge sum for a blockaded country.62

From 1917 to the early 1920s, shortages of imported goods, such as foodstuffs, fossil fuels and raw materials, stimulated inflation in both Finland andSweden. At the same time, unemployment increased and living standards fell.In 1917 - 1918 both countries were facing the bottom of the wartime crisis.The Swedish krona which had been so highly valued up to late 1918, began tolose its external value, while its internal value was weakening at an accelerating rate. Inflation in Sweden was even higher than in some belligerent countries. For example, the Swedish wholesale price index (1913 = 100) rose to 370by the last quarter of 1918; in Britain the corresponding figure was 235.63

There was a certain imbalance between the internal and external value of theSwedish currency. The Swedish krona lost as much as two thirds of its internalpurchasing power although it had no difficulty in maintaining its parity inrelation to gold.

Due to the Civil War of four months in 1918, the Finnish economy was inchaos for a whole year. Foreign trade had fallen to an extremely low level,because the new ‘White’ government had trade relations only to Germany,Sweden and Norway, and those three countries were able to supply merely asmall fraction of the goods the Finns needed. Continuing devaluation of theFinnish markka reflected the distrust of foreign countries of the survival of thenew republic, which also suffered from exceptional inflation. Both the rebelling ‘Reds’ and the ruling ‘Whites’ had fmanced their war efforts by printingbank notes. When the government’s note printing press was in the hands ofthe ‘Reds’, 100 million markkas were illegally printed, whereas the ‘Whites’

62 Heckscher e. al., 1930, op. cit., p. 219.63 Ibid.,p.223.

Economic Crises in Finland and Sweden, 1914-1924 53

spent 300 miffion markkas for ‘the restoration of general order.M The end of

the Civil War in May 1918 did not relieve the economic problems of Finland.

The Allied Powers still kept it under a blockade because there were German

troops in the country and Finland continued its close relations to the Germangovernment. After the armistice in autumn 1918, the blockade was lifted. In

the following spring when the Baltic Sea was freed from ice and the ports

opened, ships carrying food aid from the Allied arrived. At the same time,

Finnish foreign trade began again through the Danish Straits.

Public Finance

Compared with the belligerents, both the Grand Duchy of Finland and the

Kingdom of Sweden had the advantage that they neither had to fmance an

army in combat nor participate in the military operations. Finland avoidedparticipating in any war on the side of Russia. Still in 1909-1913 it had to pay a

sum amounting about 6 per cent of its annual state budget to the Russiantreasury for military protection. Even though its expenditures in nominal

terms slightly increased during the war to 1916, the percentage of the GrandDuchy’s military payments gradually declined and fmally in 1917, it droppednearly to zero. After gaining independence and the Civil War, Finland built upits own army, at which time its military expenditures accounted for 13 per cent

of the total government expendituresPFrom 1809 onward, the Finnish state finance had been separated from

those of Russian. Consequently, the revenues collected in Finland were spentin the Grand Duchy except some transfers to the Russian treasury for militaryand transport services. During 1914-1917, the Finnish state fmance was inbalance, despite the substantial effects of inflation on revenues and expenditures. Nevertheless, the structure of the revenues changed. In the prewar period, customs duties constituted the main revenue. While imports fell after theoutbreak of the war, import duties decreased. The Finnish government, however, continued to collect revenues from its forests and land properties and

excises for beverages and luxury goods. The net revenues from the State railways also remained small during the first war years, although the wartimegovernment had introduced a 25% surcharge on the prices of train tickets.Some other new taxes were collected as well. Furthermore, direct taxesformed rather an insignificant source of state revenue up to 1916, when a

64 Harmaja 1933, op. cit., pp. 100; Harmaja 1940, op. cit., p. 290.65 Harmaja 1933, op. cii., pp. 97-103; Harmaja 1940, op. cii., pp. 283-297.

54 Timo Myllyntaus & Eerik Tamaala

progressive tax for high earnings was launched. Beginning in the followinyear, direct taxes became the main source of the state revenues and in 192the whole system of income and wealth taxes was reformed in order to guaiantee sufficient state finances to cover the increasing expenditures. Whe,foreign trade was normalised in the 1920s, the state revenues again becambased on the customs duties.66

The structure of the state expenditures remained fairly stable up to 191(Soon after that year, the costs of the State Railways doubled. The expenditures of the Ministry of Justice also quadrupled because the costs of priso:maintenance increased enormously owing to the higher food prices anddrastic rise in the number of prisoners after suppressing the Rebellion i:1918.

In the first war years, the national debt did not substantially increaseFrom 1917, the pronounced deficit in the Finnish state finances had to bcovered with foreign loans, and for some time the financial situation was critical. Political independence increased the obligations of the State that togethewith inflation caused a substantial rise in outlays. Due to political and economic turmoil, the government could not increase its revenues, and thineighbour of unstable Russia, the nascent republic faced serious problems iiapplying for loans from abroad.

Despite some internal political unrest, neutral Sweden avoided the CiviWar that engulfed Finland and managed to preserve its neutrality and refralifrom military conflicts with belligerents. Nor were the Swedish state finance:shaken by large and expensive societal reforms. Although some structurachanges took place, during the war the Swedish state budget was kept in balance. When the war ended, Sweden was fmancially stronger than before itoutbreak: during the prewar period, Sweden had been a debtor in the foreigifinancial markets but after the armistice it took on a new role as a creditoination.

Divergent Roads in the Postwar Years