What did Isaac Write for Constance?

Transcript of What did Isaac Write for Constance?

What Did Isaac Write for Constance?Author(s): DAVID J. BURNSource: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Winter 2003), pp. 45-72Published by: University of California PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2003.20.1.45 .

Accessed: 25/03/2014 10:52

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to TheJournal of Musicology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journal of Musicology 20/1 (2003) 45–72. ISSN 0277-9269, electronic ISSN 1533-8347s © 2003 bythe Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Send requests for permission to reprintto: Rights and Permissions, University of California Press, Journals Division, 2000 Center Street, Suite303, Berkeley, CA 94704-1223.

45

What Did Isaac Write forConstance?

DAVID J . BURN

At the turn of the 16th century, the city ofConstance was among the most musically ambitious in the Empire.1Under the direction of the deeply artistically interested bishop Hugovon Hohenlandenberg (bishop from 1496–1528), the city was kept upto date with the most advanced musical and liturgical trends. In partic-ular the city’s cathedral was engaged, from the beginning of Hohenlan-denberg’s reign, with the creation of an élite choral institution en-dowed with a worthy musical repertory.2 The high value placed on theproduction of new musical works is clear from the surviving archivaldocuments which chart the matters considered at the weekly chapter

This article draws on research carried out for the author’s doc-toral thesis, “The Mass-Proper Cycles of Henricus Isaac: Genesis,Transmission, and Authenticity” (Oxford Univ., 2002). I grate-fully acknowledge the financial support of the Arts and Humani-ties Research Board, without which this work would not havebeen possible. I am also deeply indebted to my doctoral supervi-sor, Professor Reinhard Strohm, for his unstinting support dur-ing this project, as well as to Christian Meyer, Suzie Clark, JürgenHeidrich, and Martin Staehelin, all of whom offered invaluablecomments at various stages in this work’s development.

1 The most important work on the musical life of Constance is that of ManfredSchuler; see “Die Konstanzer Domkantorei um 1500,” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 21(1964): 23–44; “Der Personalstatus der Konstanzer Domkantorei um 1500,” Archiv fürMusikwissenschaft 21 (1964): 255–86; “Zur liturgischen Musikpraxis am Konstanzer Domum 1500,” in Heinrich Isaac und Paul Hofhaimer im Umfeld von Kaiser Maximilian I.: Berichtüber die vom 1. bis 5. Juli 1992 in Innsbruck abgehaltene Fachtagung, ed. Walter Salmen (Inns-bruck: Helbling, 1997), 71–80; and the entries for “Konstanz” in The New Grove Dictionaryof Music and Musicians, 2nd ed. (New York: Grove’s Dictionaries, 2001) and Die Musik inGeschichte und Gegenwart, 2nd ed., ed. Ludwig Finscher (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1994– ).

2 Schuler, “Die Konstanzer Domkantorei,” 39–40.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

meetings: The employment contract of Sebastian Virdung in 1507specifically mentions composing among his duties; later, Sixt Dietrichwas subject to similar conditions, given time during the day specificallyfor composing, and even allowed to pay his debts with new music.3

The activities of Emperor Maximilian I’s court composer, HeinrichIsaac, in Constance only add further, and even more extraordinary, tes-timony to the ambition of the authorities. Belonging as he did to Maxi-milian, Isaac could never be employed long-term in the city. Rather, it is clear from both surviving archival documents and the composer’s ac-tual output that he undertook commissioned works on more than oneoccasion. Isaac cannot be presumed to have had any connections withConstance prior to entering Imperial employment in 1496. However,evidence that he was not only known in that city, but had also carriedout compositional tasks at the behest of musicians active there withinthe decade following this, is provided by the Fridolin Sicher organ tab-lature, where his motet Sub tuum praesidium is headed with the words‘Hainricus Isaac. Ex petitione Magistri Martini Vogelmayer Organistaetunc temporis Constancie.’4 If the testimony is to be believed—andthere seems no reason for doubt—Vogelmayer’s death in 1505 placesthat year as a terminus ante quem. The same manuscript contains anotherwork by Isaac, the responsory Quae est ista, for which Constantine connections are obliquely alluded to by Glarean:

. . . Quae est ista, quod in diocaesi Constantiensi frequens canitur. Sedin formula Hypohrygii, ad quam Henrico Isaac quatuor vocibus con-flatum memini me videre, si nomen non mentiatur authorem.

(. . . Quae est ista, which is often sung in the diocese of Constance.But in the hypophrygian mode, of which I remember seeing a four-voice setting by Heinrich Isaac, if the name of the author is not false.)5

Glarean’s suggestion is supported by the appearance of Quae est ista inthe Fridolin Sicher tablature, which was produced in Constance. Anorigin different from that of Isaac’s other responsory settings, which

3 Schuler, “Die Konstanzer Domkantorei,” 30; “Der Personalstatus,” 260, 262; “Zurliturgischen Musikpraxis,” 73.

4 SGallS 530. This and all subsequent manuscript references use the sigla abbrevia-tions from Herbert Kellman, et al., Census-Catalogue of Manuscript Sources of Polyphonic Mu-sic, 1400–1550 (Stuttgart: American Institute of Musicology, 1979–88).

5 Dodecachordon, ed. and trans. Clement A. Miller (Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1965), 1: 187; Martin Staehelin, Die Messen Heinrich Isaacs, 3 vols. (Bern-Stuttgart: Paul Haupt, 1977), 2: 109. Despite Glarean’s hesitancy, no one has questionedthe work’s authenticity, because the sources unanimously name Isaac as its author. SeeMartin Just, “Studien zu Isaacs Motetten,” 2 vols (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Tübingen, 1960), 1:60, 215; Emma Kempson, “The Motets of Henricus Isaac (c. 1450–1517): Transmission,Structure, and Function,” 2 vols. (Ph.D. diss., King’s College, London, 1998), 1: 131–36.

46

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

were mainly for the Imperial court, is suggested by the piece’s widersource situation: this motet is the only one of Isaac’s responsory settingsto be preserved outside of central-European sources. It appears also inthe Florentine manuscript FlorBN II.I.232.6 Martin Just dates the motetto ca. 1500.7

Opportunities for Isaac to have been physically present in Constanceprior to the limit-date suggested by Sub tuum praesidium are not difficultto find, although incontrovertible proof is lacking. He may have stayedthere as part of Maximilian’s entourage during one or more of the lat-ter’s visits to the city in 1503, 1505, or even as early as 1499. The last ofthese dates has not previously been considered due to the belief, helduntil recently, that Isaac had at that time been loaned to Frederick theWise, and was therefore in Torgau. Jürgen Heidrich has now shownthat this was not the case.8 Isaac could thus have been acquainted withConstance and its musicians from almost the beginning of his Habs-burg years. The composer is documented in Florence on 25 September1499, but he could have travelled there directly from Constance, as heis thought to have done in 1509.

Constance Cathedral’s Request to Isaac for Mass-propers

These details give the backdrop to Isaac’s most spectacular and im-portant association with Constance, which resulted in his composing asubstantial body of mass-proper cycles for the city’s cathedral. It is withthis project, later published under the title of Choralis Constantinus, thatthe rest of this article is concerned.

Sometime around the beginning of 1507 Isaac returned to Con-stance in order to be at hand for the Imperial Diet, or Reichstag, thatthe city was to host between April and July of that year. If Reichstagswere often lavish affairs, the Constance one of 1507 promised to beparticularly brilliant as Maximilian prepared to fulfil his longstandingambition of being crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome by the Pope(he was only later to know that he would have to settle for having theceremony performed in Trent by a Papal legate in February 1508).Isaac wrote two motets specifically for the occasion: the bipartite Sanctispiritus assit nobis gratia/Imperii proceres, and the imposing six-voice Virgo

47

6 On this source, see Anthony Cummings, “A Florentine Sacred Repertory from the Medici Restoration (Manuscript II.I.232 [olim Magl. XIX.58; Gaddi 1113] of the Bib-lioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence): Bibliography and History,” Acta Musicologica 55(1983): 267–332.

7 Just, “Studien,” 1: 215.8 Jürgen Heidrich, “Heinrich Isaac in Torgau?,” in Heinrich Isaac und Paul Hofhaimer,

155–68.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

prudentissima.9 Both provide direct insight into the spectacular natureof the event.

It is known that Isaac remained in Constance following the close ofthe Reichstag from the fact that Machiavelli recorded having met himthere in November of the same year.10 Moreover, Isaac was not aloneamong the members of Maximilian’s establishment to have been left in the city; Georg Slatkonia, director of the Imperial choir and bishopof Pedena (later, first bishop of Vienna and Imperial Councillor), wasalso there. He and Isaac may have been expecting a summons fromMaximilian to attend the Imperial coronation, but were left waiting be-cause Maximilian’s plans were thwarted. Whatever the case, both menwere still in Constance in April 1508, when the cathedral chapter de-cided to approach Isaac with a request for some music, entrusting thenegotiations with the composer to Slatkonia:11

[1508] Ex parte componiste capelle Regiae maiestatis.

Die xiiii aprilis, uff anzaigen dominorum decani Randegk et Clingen-berg des erbietens rectoris capelle Regiae Maiestatis [=Slatkonia] Istconcludiert, mit demselben und dem ysaac componisten zureden, ober etlich officia In summis festivitatibus zesingen in ringem sold, com-poniren und schriben lassen welt pro choro ecclesie Constantiensisund so verr das in erlidenlichem gelt der fabric sin möcht, söhlsmachen zelassen—et ad hoc deputati sunt [. . .] domini praescripti.

(1508. Concerning the chapel composer of His Majesty the King.April 14, at the notice of the lords Dean Randeck and Lord Clingen-berg, and of the request of the rector cappelle of the king [GeorgSlatkonia], it is concluded, to speak with the same, and with Isaac the composer, to see if he will, for a little money, compose and havecopied some offices for the highest feasts, for the choir of Constancecathedral, as far as that should be affordable from the Fabric’s money, to let this be made—and to this are the aforementioned lordsentrusted.)12

48

9 See Staehelin, Die Messen, 2: 64–66; Just, “Studien,” 1: 66; Kempson, “The Motets,”1: 220–42, 262–67, 315–16.

10 Letter of 17 January 1508. Text and literature cited in Staehelin, Die Messen, 2:66–67.

11 The idea for the commission may have been born during the chapter’s tradi-tional Ash Wednesday meal, on 8 March 1508, at which Slatkonia was a guest. See MartinBente, Neue Wege der Quellenkritik und die Biographie Ludwig Senfls: Ein Beitrag zur Musik-geschichte der Reformationszeitalters (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1968), 275–76.

12 Constance, Domprotokolle 3366. The document was first brought to light byOtto zur Nedden and published in his article “Zur Musikgeschichte von Konstanz um1500,” Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft 12 (1929/30): 449–58, 455; see also Staehelin, DieMessen, 2: 67; Manfred Schuler, “Zur Überlieferung des Choralis Constantinus von Hein-rich Isaac,” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 36 (1979): 68–76 and 146–54. I am grateful toReinhard Strohm for help in translating this and subsequent documents.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

Isaac must have received the proposal and its conditions well, for thenext document referring to the project, dating from a year and amonth after the commission, on 18 May 1509, records that music hadbeen sent and was to be looked after by the master of the choirboys:

1509 Ex parte cantus figurativi per ysaac pro fabrica composti.

Die 18 Mai ist capitulariter concludiret und daruff bevohlen dem Johanness praeceptori der knaben per iuramentum sölh gesang zuversorgen und nichts daruß schriben zelassen.

(1509 Regarding the polyphony composed by Isaac for the cathedral.—It is concluded by the chapter on May 18, and thereupon ordered,to entrust, under oath, Johannes, the master of the boys, with the careof these songs, and not allow any of them to be copied.)13

A further entry in the chapter records from November 29 of the sameyear is the last in that series to mention Isaac’s music. It states that thepieces are to be submitted for testing, and that Isaac is to be paid:

1509 Exparte Cancionalis per ysaac transmissi.—

Die 29 Novembris Ist capitulariter concludiret daz die Senger sölhcancional oder gesang besehen und ubersingen söllen und so verre sydieselben gantz und gerecht finden So söllen procuratores fabriceden ysaac, den Schriber und den botten lutt des zugesandten zedelserlich entrichten etc. angesehen, dz man Im sölhs zemachen bevohlenund verdingt hat.

(1509 Regarding the songs sent by Isaac.—It is concluded by thechapter on November 29 that the singers should check and try outthis cancional or song, and in so far as they find them complete andcorrect, so should the guardians of the Fabric pay Isaac, the copyist,and the messenger according to the papers sent honestly, etc., giventhe fact that one has employed him to make these songs.)14

One final document in the story is undoubtedly the most impor-tant: the series of three prints issued by Hieronymous Formschneiderin 1550 and 1555, entitled Choralis Constantinus and containing themusic Isaac offered to the authorities at Constance in fulfillment oftheir request. The first volume, CCI, (1550) contains 47 cycles for Sundays throughout the year, prefaced with a setting of the “Aspergesme,” to be sung at the beginning of each mass. The Sundays begin withTrinity Sunday and continue through 23 Sundays after Pentecost be-fore arriving at Advent, the traditional start of the liturgical year. There

49

13 Constance, Domprotokolle 3664. See Bente, Neue Wege, 276–77; Staehelin, DieMessen, 2: 68–69.

14 Constance, Domprotokolle 3809. Further references as in previous note.

49

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

are then settings for four Sundays in Advent. After these comes theSunday in the octave of Epiphany, those that follow it, those that leadup to and occupy Lent, and those that follow Easter. Easter Sunday it-self is not included, nor is Pentecost (these are found in CCII). CCI’sunusual arrangement, not beginning with Advent but in the middle ofthe church year, may have been a printer’s mistake.15 CCII (1555) con-tains 25 proper-cycles for high feasts, both of fixed calendar date, suchas Christmas, as well as moveable, such as Easter and Pentecost. Themajor Marian feasts are included, but so too are those of saints of signif-icance to Constance (St. Conrad, St. Geberhard, St. Pelagius). CCIII(also 1555) is structured in four sections: 1) Propers for the Commonof Saints; 2) Marian proper-cycles; 3) Proper-cycles, under the headingof “seorsum de sanctis,” setting feasts of the same type as those found inCCII; and 4) Mass ordinaries. The repertory of the first group, CCIII/1–6, is organized by type (Apostles, Martyrs, Confessors, Virgins, etc.).Within each type-grouping, each proper-genre is provided with a varietyof settings of different chants, which can be extracted as appropriateand compiled together to make cycles of the music that are requiredfor specific days. A group of five tracts, which may be drawn upon forCommon of Saints days that occur during Lent, falls between CCIII/6and CCIII/7. The second repertory group, the Marian cycles, com-prises CCIII/7–9. The “seorsum de sanctis” (meaning “separate” or“apart”) comprises the remaining proper-cycles in the volume. In-cluded in the “seorsum” are settings both of days of a similar ranking tothose of CCII but for which no setting was provided in the earlier vol-ume, as well as alternatives for a number of days that were previouslycovered. Five mass ordinaries close the volume. All the proper-settingsin CCIII differ musically from those of CCI and CCII in that they placetheir chant-derived cantus firmi in the bass voice, not the discantus.

Despite the fact that the quantity of surviving evidence relating tothe circumstances under which the Choralis was composed is signifi-cantly greater than is usually the case with 16th-century music, there isstill much which the scholar must deduce, hypothesize, or admit as nowunknowable.

Smaller matters include the practicalities of Isaac’s working conditionsand presentation of the music to its commissioners. It has been gener-ally agreed that the dates of the second and third Constance chapterrecords are closely tied to delivery dates of the music. The chapter met

50

15 Gerhard-Rudolf Pätzig, “Liturgische Grundlagen und handschriftliche Über-lieferung von Heinrich Isaacs ‘Choralis Constantinus’,” 2 vols. (Ph.D. diss., Univ. ofTübingen, 1956), 1: 6n2, 84–85. It is possible, however, that the arrangement was delib-erate, and reflects the Trinity cycle’s membership of the Constance commission music.See below.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

weekly, so the matters they discussed on any one occasion arose in thesix days since their previous meeting. On this basis, Manfred Schulerasserted that Isaac fulfilled the commission in two parts, with a first de-livery arriving sometime in the week prior to 18 May 1509, and a sec-ond sometime in the week prior to November 29.16 Although theseconclusions seem reasonable, a close reading of the documents doesnot permit events to be so firmly pinned down. The only secure factsare that some of Isaac’s music must have been in the chapter’s posses-sion by 18 May 1509, and that the final settling of accounts planned on November 29 must indicate the latest concluding date of the proj-ect. The number of deliveries, and when they were made, remains unclear. External circumstances suggest that Isaac finished the worksooner than Schuler supposed. There is no information on Isaac’swhereabouts between his commissioning in 1508 and May 1509, bywhich date some music had been composed, so Isaac could have re-mained in Constance during these months and presented his music tothe chapter in person.17 After this, however, it would have been difficultfor Isaac to work steadily on the project: By 7 August 1509, he was inFlorence and may have joined Maximilian in his travels around Italyand the southern Tyrol for the rest of the year.18 The November recordstates only that the songs should be tested and Isaac paid. It is possiblethat it was prompted only by the arrival of Isaac’s bill. No figure is givenfor what Isaac was finally paid for his services.

More important, and central to the present discussion, is deducingwhat music Isaac provided in fulfillment of the Constance commission.From the Constance documents, there are no more detailed descrip-tions of what the music consisted of beyond the “etlich officia in sum-mis festivitatibus” mentioned in the original commission. The publica-tion of the Choralis Constantinus print shows in spectacular fashion thatIsaac did indeed compose a significant body of music for Constancecathedral, yet the peculiar history behind the transmission of the printraises as many issues as it solves.

The Make-Up of Isaac’s Constance Commission: Existing Theories

In consisting of cycles for the proper of the mass, the contents ofthe Choralis prints can clearly be equated with the commission’s requestfor “officia.” Yet it is also clear that not every piece in the prints was des-tined for Constance. Indeed, that the prints contain music for (at least)two institutions, and are thus composite in nature, is not controversial.

51

16 Schuler, “Zur Überlieferung,” 68–69n2.17 See Bente, Neue Wege, 276.18 See Bente, Neue Wege, 276–77; Staehelin, Die Messen, 2: 68.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

It is suggested by two points evident from any examination of theprints’ contents. First, not every feast that receives a setting in the printscan be considered to rank among the “highest feasts” specified in thecommission document. The prints provide music for many more daysthan those allowed even by a broad interpretation of Constance’s re-quest. Secondly, and more critically, both the second and third parts ofthe Choralis offer settings of six feasts: John the Baptist, Peter and Paul,the Visitation of Mary, Mary Magdalen, Assumption, and the Nativity ofMary.19 Multiple provision would seem redundant in the context of thecommission, and in fact, a comparison between the twin settings sug-gests that the members of each pair were intended for different liturgi-cal rites. The texts and chants prescribed for each movement of the respective settings are not always identical (e.g. the CCII cycle for theVisitation sets the alleluia “Magnificat anima mea,” while that of CCIIIsets the alleluia “In Maria benignitas per saecula commendatur”).20

Once it is settled that the print is composite, a much more complexissue arises: How does it divide? Which parts were for Constance, andwhich for elsewhere? For whom were the other parts destined? Scholarsover the past fifty years have addressed these questions in a variety ofways.

It was Werner Heinz in his 1952 dissertation who first proposedthat the Constance commission music and the contents of CCII wereidentical.21 Heinz made his suggestion on stylistic and logical grounds.But, as the full development of this possibility was not the principal aimof his research, he left conclusive demonstration of the matter to Gerhard-Rudolf Pätzig, of whose work he was not unaware. In 1956,Pätzig supported the theory that CCII may be equated with the Constancecommission through liturgical and source analysis.22 Pätzig’s methodwas to compare the liturgical items set in the Choralis cycles to servicebooks from Constance and from the Imperial orbit of Isaac’s employer,Maximilian. Using the printed 1505 Constance missal,23 the manu-script missal of Bishop Hohenlandenberg (which differs in some re-spects from the 1505 print),24 and the printed 1511 Graduale Pataviense,25

52

19 The Assumption services, CCII/5 and CCIII/7, are only apparently paired. Theassignment in CCIII is a printer’s mistake. The service is correctly assigned in the “Opusmusicum”; see Pätzig, “Liturgische Grundlagen,” 2: 133.

20 A full comparison is given in Pätzig, “Liturgische Grundlagen,” 1: 28–29.21 See Werner Heinz, “Isaacs und Senfls Propriums-Kompositionen in Hand-

schriften der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek München” (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Berlin, 1952).22 Pätzig, “Liturgische Grundlagen.”23 Missale Constantiense (Augsburg: Erhard Radolt, 1505).24 Erzbischöfliches Ordinariat, Freiberg im Br.25 The Graduale Pataviense (GP) is now available in facsimile, ed. Christian Väterlein,

Das Erbe deutscher Musik 87 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1982).

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

which was also used in the diocese of Vienna, Pätzig was able to ascer-tain that only the items in CCII matched the Constantine rite. Further-more, Pätzig concluded that the remaining volumes of the Choralis, CCIand CCIII, contained music originally composed for the Imperial court.The latter finding was supported through analysis of the source situa-tion: A significant part of CCI and CCIII may be found in manuscriptsources predating the print, in five choirbooks originating from theMunich court in the 1520s. The manuscripts are now housed in theBayerische Staatsbibliothek. Portions of CCIII are found in MunBS35–38. Near-identical title pages in two of these four books show thatthey form a set, entitled “Opus musicum.” They are dated 1531. Seven-teen of the 47 cycles of CCI are in MunBS 39.26 All this music appearsto have been transmitted to Munich from the Imperial court via Lud-wig Senfl, who took up a post there after the Imperial chapel choir wasdisbanded by Maximilian’s successor Charles V. The Imperial, ratherthan Constantine, origin of CCI is supported through additional con-cordances, albeit with variant readings, in a manuscript from the Saxoncourt of Frederick the Wise (manuscript WeimB A).27

CCII, on the other hand, has almost no sources for any of its musicprior to the print. This very absence suggested to Pätzig that his pro-posal was correct, because it may have been the result of the successfulimplementation of the copying ban stated in the Constance chapterrecords.28 Pätzig noted, nonetheless, that some cycles for which an ori-gin at the Imperial court was supported by the sources (i.e. they werepresent in the Bavarian choirbooks) did not entirely agree in their chosen texts with those prescribed by the Graduale Pataviense. From thishe hypothesized that the Imperial court used a special and distinct

53

26 The most comprehensive study of these and other choirbooks in the BavarianState Library is Bente, Neue Wege. His claim that the fascicles that make up these choir-books originated, in part, from the Imperial chapel was recently and compellingly chal-lenged by Birgit Lodes, who showed that these books were most likely produced in Munich in the 1520s (“Ludwig Senfl and the Munich Choirbooks,” paper read at theJahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Musikforschung, Würzburg, October 2001). I am ex-tremely grateful to Dr. Lodes for providing me with a copy of this paper. The source situa-tion of the Choralis print as a whole is complex. See Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,”55–122.

27 See, most recently, Jürgen Heidrich, Die deutschen Chorbücher aus der HofkapelleFriedrichs des Weisen: Ein Beitrag zur mitteldeutschen geistlichen Musikpraxis um 1500 (Baden-Baden: V. Koerner, 1993); Kathryn Duffy, “The Jena Choirbooks: Music and Liturgy atthe Castle Church in Wittenberg under Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony,” 5 vols.(Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Chicago, 1995); also Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 160–87, 269–83.

28 A document transcribed in Schuler, “Der Personalstatus,” 264, records that in1510 the chapter forbade Thomas Krebs from copying motets and “other special songs.”This may have referred to Isaac’s commission. Only one other institution may have hadcopies of Isaac’s commission in his lifetime—the Imperial court—however, there is no evidence to support this hypothesis.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

rite.29 It is to be noted that Pätzig’s conclusions are not based on obser-vations drawn from the music, such as analysis of the specific forms ofthe chant melodies Isaac employed, but only from relating the Choralisand the service books in terms of their texts. Support from chantmelodies was, and remains, difficult because of a lack of chant sourcesfrom Constance, and because it is unclear what factors governed a com-poser’s choice of chant form.30

Pätzig’s conclusions are important. The assignment of the greaterpart of the Choralis music to the Imperial chapel is not only significantin itself but also brings the Constance commission into sharper focus.In light of subsequent research, it appears that Constance was inter-ested in acquiring a body of polyphonic propers for its cathedral pre-cisely in imitation of the Imperial court, which may have been involvedin a polyphonic mass-proper project since the late 1490s.31 Indeed,Maximilian may even have employed Isaac specifically to fulfill this gargantuan compositional task.

Following on from Heinz and Pätzig, the next major scholar to address Choralis-related issues was Martin Bente. He proposed a sig-nificant revision of their division hypothesis.32 Bente’s work was not expressly focused on the Choralis, but on the 16th-century choirbookshoused at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, among which, as mentionedabove, number several extremely important sources for the Choralis. Asnone of Bente’s sources included any piece from CCII, he left Pätzig’sconclusions for that volume untouched. Also not discussed were con-clusions regarding the origins of CCI. However, his analysis of the sourcesof CCIII led him to attribute a significant part of that volume to Con-stance. Bente’s reassignments all concern pieces from the Common ofSaints (CCIII/1–6 and tracts). His hypothesis was drawn from thesource situation. Every movement in the Marian cycles (CCIII/7–9)and the “seorsum de sanctis” (CCIII/10–25) has a concordance in the“Opus musicum” manuscripts (MunBS 35–38). Their presence in theBavarian manuscripts assures them an Imperial origin. This accounts

54

29 Some later scholars have seen this as contrived (see e.g. Bente, Neue Wege, 131).For more recent observations on the many problems of matching the Choralis to any par-ticular rite, see David Crawford, “Printed Liturgical Books in Isaac’s Circle,” in HeinrichIsaac und Paul Hofhaimer, 57–70, esp. 60–61.

30 See Theodore Karp, “Some Chant Models for Isaac’s Choralis Constantinus,” in Be-yond the Moon: Festschrift Luther Dittmer, ed. Bryan Gillingham and Paul Merkley (Ottawa:Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1990), 322–49; “The Chant Background to Isaac’s ChoralisConstantinus,” in International Musicological Society Study Group Cantus Planus: Papers Read atthe 7th Meeting, Sopron, Hungary, 1995, ed. László Dobszay (Budapest: Hungarian Acad-emy of Sciences, 1998), 337–41.

31 According to Heidrich’s dating of the important Isaac manuscript WeimB A (Diedeutschen Chorbücher, 198–251).

32 See Bente, Neue Wege, 117–39.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

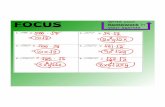

for 50 pieces of the 132 that make up CCIII. Of the remaining 82pieces, 31 have concordances in a set of part-books with Munich con-nections, probably produced in the 1530s, and now in the Öster-reichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna (VienNB 18745).33 The final51 pieces have no pre-print source. It was to these 51 pieces that Benteattributed a Constance origin (see Fig. 1). Statistically, this is highly sig-nificant: The 51 pieces comprise 40 percent of CCIII and increase thesize of the Constance commission by 50 percent.

Just as Bente provided a previously absent detailed picture for thecreation of CCIII, Manfred Schuler aimed to unravel the transmissionof the Constance commission from its original owners to the printingpress, a particularly complex task in the face of almost total silencefrom the sources.34 No discussion of Isaac’s work for Constance canavoid citing Schuler’s foundational research in disclosing likely paths bywhich the music traveled, yet Schuler did not aim to tackle the previ-ously advanced divisions of the collection beyond clarifying the positionof the cycle for Trinity Sunday. The latter cycle is found in CCI ratherthan CCII, but in all likelihood belonged to the Constance commission.Constance would certainly have wanted a setting for this day. Why thiscycle was placed in volume 1, despite the fact that other Sundays thatalso rank as high feasts (Easter and Pentecost) were included in volume2, is unclear. However, its membership in the commission music, ratherthan in the Imperial cycles that form the remainder of the Sunday seriesin CCI, may perhaps be indicated by the fact that CCI opens with this cy-cle (following the “Asperges me”), and not with the more conventionalfirst Sunday in Advent.35 This point aside, Schuler focused his attentionon the historical narrative behind how the music—whatever it may havebeen—was transmitted, rather than on what precisely this repertorywas. In showing that a number of pieces later found in CCII seem tohave been transmitted directly from Constance into other manuscripts,his findings supported Pätzig’s.36 He remains noncommittal aboutBente’s additions, mentioning the proposal, but avoiding discussion.37

55

33 Actually, only 30 pieces are concordant; Bente mistakenly claimed the VienNBsetting of the communion, Laetabitur iustus, to be identical with that in CCIII; see below.On the scribes and dating of the VienNB 18745 partbooks, see Bente, Neue Wege, 119–22;Martin Staehelin, “Aus ‘Lukas Wagenrieders’ Werkstatt: Ein unbekanntes Lieder-Manuskript des frühen 16. Jahrhunderts in Zürich,” in Quellenstudien zur Musik der Renais-sance I: Formen und Probleme der Überlieferung mehrstimmiger Musik im Zeitalter Josquins Desprez,ed. Ludwig Finscher, Wolfenbütteler Forschungen 6 (Munich: Kraus International,1981), 71–96.

34 See Schuler, “Zur Überlieferung.”35 Pätzig considered the overall organization of the volume the result of a printer’s

error. See n15, above.36 See “Zur Überlieferung,” 147 and 150.37 See “Zur Überlieferung,” 69, and “Zur liturgischen Musikpraxis,” 79n27.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

Finally, and most recently, Helmut Hell challenged all previous the-ories regarding the division of the Choralis by proposing that the secondvolume of the print may have been compiled from a mixture of Im-perial and Constantine repertory.38 Hell was led to his conclusions notthrough a concern with Constance, but rather with the curious lacunathat exists if the current divisions of the Choralis print are to be be-lieved: If all of CCII was for Constance, where are the settings Isaacmade for these same days at the Imperial court? They do not surviveunder his name in any extant source, yet the composer must surelyhave provided Maximilian with music for these days. They are the mostimportant in the church’s calendar, and it would be extraordinary ifmiddle- or low-ranking Sundays were endowed with polyphony, whileChristmas, Easter, and so forth were not.39 Hell went on to suggest thatthe Choralis print was compiled not via the mediation of any of the insti-tutions that were the recipients of Isaac’s music (and hence not via anyextant sources), but from Isaac’s “Nachlaß.” From this putative collec-tion, which could have contained Isaac’s high feast settings for both Con-stance and the Imperial court, the compilers of the print would havebeen free to pick and choose between the settings that they liked most.Hell suggested stylistic analysis as a method of deciding which parts ofCCII may have belonged to the Imperial chapel and which to Constance.He leaves his proposal aside at that point and pursues it no further.

56

38 See Helmut Hell, “Senfls Hand in den Chorbüchern der Bayerischen Staatsbib-liothek,” Augsburger Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft 4 (1987): 65–137.

39 Hell, “Senfls Hand,” 87–88.

figure 1. Genesis of CCIII (Bente)

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

The Division of the Choralis Reassessed

Given such a diversity of opinion, a reassessment of the division ofthe Choralis is clearly in order. If it is true that general literature trans-mits Pätzig’s conclusions, that is not due to the later theories havingbeen critically engaged then dismissed, but rather due to their havingpassed unnoticed. The following discussion aims to address the validityof each of the revisions proposed since Pätzig’s initial division for thefirst time. It is simplest to approach the theories in reverse order.

Hell’s primary observation concerning the one-time existence ofImperial high feast cycles is pertinent, and it is a pity that he does notdetail specifically which works in CCII he believes to have belonged tothis series. In the event, transmissional and liturgical evidence speaksseriously against an Imperial origin for almost all of CCII’s cycles.

Hell’s theory is enabled by suggesting that all of Isaac’s mass prop-ers, both Constantine and Imperial, were transmitted to the printersthrough Isaac’s “Nachlaß.” There is no surviving concrete evidence tosupport this view. Admittedly, from the point of view of sheer practical-ity it seems reasonable to suppose that Isaac kept copies of at least someof his music to show to prospective patrons or to rework if time wasshort. Also, there is a curious chronological coincidence between thedeath of Isaac’s widow, Bartolomea, in 1534 and the preparation of themodels for the print, which seem to have been almost complete by ca.1537, despite the fact that the prints themselves would not appear until1550 and 1555. Yet the parts of the print that do have sources refutethe “Nachlaß” theory and suggest more obvious lines of transmissionfor the more problematic parts. Bente showed that much of CCI andCCIII came via Munich. This does not rule a “Nachlaß” out of the pic-ture, but it does mean that the theory cannot be accepted in isolation.The “Nachlaß” theory must also coexist with the lines of transmissiondirect from Constance that were revealed by Schuler.40 Schuler showedthat the cathedral lost certain key members of its music establishmentfollowing the exile of the chapter in 1528. Four Choralis concordancesare owed to copies of Isaac’s commission owned by these musicians:CCII/1, 2, and 3 in Georg Rhau, Officiorum (ut vocant) de Nativitate . . .Tomus primus,41 and CCII/6 in StuttL 32 and ZürZ 169.42 A transmis-sion direct from Constance for the Choralis itself thus has some evi-dence to support it, in contrast to the “Nachlaß” theory. Although thelatter cannot be dismissed outright, it is weak compared to the other

57

40 Schuler, “Zur Überlieferung.”41 Nuremberg, 1545; RISM 15455. Georg Rhau, Musikdrucke aus den Jahren 1538–

1545 in praktischer Neuausgabe XII, ed. Frank Krautwurst (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1999).42 Schuler, “Zur Überlieferung,” 147 and 150.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

possibilities. Whatever transmission theory is believed, Schuler’s resultsshow that four CCII cycles were not Imperial. Liturgical and other evi-dence supports Schuler and rules out an Imperial origin for nearlythree-quarters of CCII’s remainder.

Pätzig showed that, liturgically, CCI and CCIII do not accord withthe Constance rite, while CCII does.43 As his unstated assumption is“Constance until proven otherwise,” he does not pursue the question ofwhether agreement with the Constance rite means disagreement withthe Imperial one. However, a comparison between the GP and CCII reveals 13 cases of such conflict, with CCII siding with Constance ineach instance (CCII/2, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 23, and 24).These cycles must thus be ruled out of consideration as Imperial highfeasts. In all but one of the remaining nine cycles, both the Constanceand Imperial liturgies are identical. CCII/12, 14, and 18 can be dis-missed: They must also be from Constance, because the same days re-ceive secure Imperial settings in CCIII.

It is with just six cycles left for consideration (CCII/4, 8, 9, 21, 22,and 25) that evidence becomes thin. Unless one doubts the sincerity ofthe print in containing the complete Constance commission some-where within its covers—and its title and transmisson evidence suggestone should not—there is room to suspect an Imperial origin only withthe St. Martin service, CCII/22. While the other five cycles all have thehighest ranking, and Isaac must have provided settings in his commis-sion music, the St. Martin cycle is of duplex rank.44 Moreover, this cyclesetting contains the only example in CCII of a conflict with the Con-stance rite: The communion sets “Beatus servus,” the chant prescribedby the GP, and not “Domine quinque talenta,” which Constance wouldhave required.45 Settling the matter by stylistic analysis, as Hell suggests,is not easy. His claim simply that the Constance set must be “kom-positorisch fortschrittlicher” is untenable,46 for before tackling the far-from-obvious task of deciding which musical parameters are to be con-sidered and what features are to be classed as more developed, it mustbe assumed that Isaac’s style ran down a single track affected only bythe passage of time. Witnesses from within Isaac’s lifetime tell us thatsuch an assumption cannot stand when they single out his ability to

58

43 There is one exception, to which Pätzig does not draw attention. See below.44 Pätzig, “Liturgische Grundlagen,” 233–34. Isaac did include other duplex feasts

in the commission, but their presence cannot be presumed a priori.45 See GP, fol. 139; Pätzig, “Liturgische Grundlagen,” 247. Both communions be-

long to the Common of Confessors.46 Hell, “Senfls Hand,” 89.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

compose in different idioms as required.47 Isaac’s surviving music itselftestifies equally to this stylistic diversity.48 Any assessment of Isaac’sproper-style must take into account the particular institutional needsand expectations, the specific genre concerned, the class of feast, thetextual meaning, the cantus firmus, and sheer compositional whim.Given the current state of research, and the number of unknown fac-tors, it is not possible to make a case strong enough to convincinglyrule out an origin at either of the two possible institutions solely on stylistic grounds. The problem with trying to use chant-forms for thiswas mentioned above.

This still leaves the problem that sparked Hell’s proposal, that ofImperial high feasts. Several possibilities are available without callingon CCII. It is likely that Imperial celebrations of these feasts involvedIsaac’s known output of six-voice introits (Hell asserts that the Imperialhigh feast cycles would have been four-voice works, though there is noreason to assume this).49 It is true that the six-voice introits would nothave been sufficient on their own. Isaac’s proper-cycles for less impor-tant days from ca. 1500 include the alleluia and communion, so set-tings of these, along with sequences, would probably have been neededby that time at high feasts as well. Fragments of this repertory may per-haps be found in cycles surviving anonymously, but which may havebeen by Isaac, and bypassed in the production of the print.50 They mayalso have really been lost.

If the most radical proposal of Hell’s must be rejected, Bente’s addition of 51 movements from CCIII to the Constance repertory isequally problematic, but in different ways. It was detailed above howBente’s suggestion arose from sources and transmission, taking all thepieces found in the two preprint sources for CCIII to be Imperial andassigning the remainder, with no prior concordances, to Constance. Alook at the evidence for this theory shows that the basis on which it isfounded is not secure. Moreover, a fresh examination of the sources allows an alternative model for the genesis of CCIII to be advanced in its place. The argument hinges on showing that sources other than

5959

47 See the letter that forms the focus of Bonnie Blackburn, “Lorenzo de’Medici, aLost Isaac Manuscript, and the Venetian Ambassador,” Musica Franca: Essays in Honor ofFrank A. D’Accone, ed. Irene Alm, Alyson McLamore, and Colleen Reardon (Stuyvesant,NY: Pendragon Press, 1996), 19–44.

48 This is most obvious in Isaac’s secular music in different national styles.49 See Reinhard Strohm’s suggestion, in Strohm and Emma Kempson, “Isaac, Hen-

ricus,” New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed.50 Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 156–60, 175–81, 269–83, proposes that the

Christmas and Epiphany cycles in the manuscript WeimB A are Isaac’s.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

VienNB 18745, but not of Constance origin, played a role in transmit-ting the Common of Saints. The following paragraphs will present thearguments in favor of the existence of these sources.

While there can be no question that the “Opus musicum” played avital role in the transmission of its music to the print models, that it didthis in conjunction with VienNB 18745 itself remains questionable.The VienNB 18745 partbooks were written ca. 1533–35, a fact difficult,though admittedly not impossible, to reconcile with print models thatwere fully produced by ca. 1537. The partbooks were produced in, orin close proximity to, the Munich court chapel. However, they wouldhave had little opportunity to be used in that establishment, if that wasever intended at all, for they were rapidly incorporated into the Fuggerlibrary in Augsburg. Bente’s implicit supposition is that the entire Mu-nich Common of Saints repertory is preserved in VienNB 18745, yetthere are no grounds for believing this. On the contrary, there are goodreasons to suppose that the print models drew on exactly the samesources as VienNB 18745 rather than on VienNB itself, that these com-mon sources had a significantly larger repertory than that preserved inVienNB 18745, including all 51 movements to which Bente attributeda Constance origin, and that all stem from Munich.

Two items of evidence support the idea that both VienNB 18745and the print models share a common source rather than a direct dependency. First, it was unnoticed by Bente that one proper-item in VienNB 18745 is not identical to the treatment found in the Choralis:51

the communion “Laetabitur iustus” in VienNB 18745 for feasts “de unomartyre infra pasce” does not concord with CCIII/4, Comm. 1, but re-mains an unicum of the Vienna source and must be classed amongIsaac’s individual proper-items.52 The mismatch of these two piecesdoes not directly contradict Bente’s scheme, as it could be claimed thatthe Choralis version had a Constance origin and that of VienNB 18745was simply omitted. Nonetheless, it is a first clue that the partbooks andprint might not be neatly related.

The second item of evidence against VienNB 18745 being a directsource for the Choralis print models arises obliquely from a comparisonof the published version of CCIII with two important documents in itstransmission: 1) a comprehensive manuscript copy of the print models,from ca. 1538 (manuscript BerlDS 40024); and 2) a detailed list of the music collection of Pfalzgraf Ottheinrich, dating from 1544 (the

60

51 See Bente, Neue Wege, 142.52 The piece is transcribed in Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 2: 19–22.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

“Heidelberg” Inventory).53 Only two pieces from the whole Commonof Saints section are missing from the Berlin manuscript copy: CCIII/3,All. 9 and the second “Audi filia” tract.54 Bente considers the alleluia, apiece by Senfl taken from the “Opus musicum,” to be the final additionto the print model, placed there after BerlDS 40024 was produced. Heremains silent about the tract, however, because it is found in VienNB18745.55 He assumes its presence in the print models and tacitly attrib-utes its lack in BerlDS 40024 to the compiler of that manuscript. Yetthere is evidence to suggest that the tract was indeed not in the sourcefrom which BerlDS 40024 was copied: Both the tract and the alleluiawere still absent from another copy of the print models described inthe “Heidelberg” Inventory.56 The book that the inventory cites doesnot survive, but a comprehensive description is given of a manuscriptcontaining the CCIII Common of Saints. The alleluia is clearly notlisted, and it is reasonable to assume that the one “Audi filia” tract isthe same as that in BerlDS 40024 rather than that found in VienNB18745.57 To piece the implications of this together: The Senfl alleluia isclearly a late addition to the print models, made sometime in the early1540s. It was drawn from the “Opus musicum” and probably involvedthe print’s compilers having contact with Munich to collect it. The sec-ond “Audi filia” tract in all likelihood came via the same route, at thesame time. This piece is the same “Audi filia” tract found in VienNB18745, but probably did not come directly from those partbooks be-cause they had by that time entered the Fugger library in Augsburg. AsVienNB 18745 was compiled from sources within the Bavarian chapel,it follows that this tract was added to the print models from the samesource that VienNB 18745 used. Given the existence of such a source,there is no reason why it should not have been used to begin with: VienNB 18745 is granted a privileged position solely through survival.

What may be said of this common source? To begin with, there islittle doubt that what is preserved in VienNB 18745 is drawn from the

61

53 On BerlDS 40024, see Gerhard-Rudolf Pätzig, “Das Chorbuch Mus. Ms. 40024der Deutschen Staatsbibliothek Berlin: Eine wichtige Quelle zum Schaffen Isaacs aus derHand Leonard Pämingers,” in Festschrift Walter Gerstenberg zum 60. Geburtstag: Im Namenseiner Schuler, ed. Georg von Dadelsen and Andreas Holschneider (Wolfenbüttel-Zürich:Möseler, 1964), 122–42; Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 110–15.

54 Pätzig, “Das Chorbuch,” 123n5, inaccurately notes that BerlDS 40024 is missingone further piece in addition to CCIII/3, All. 9 and the second “Audi filia” tract. Thisthird piece is given in Pätzig’s incipit list.

55 See Bente, Neue Wege, 122n3.56 On the “Heidelberg” Inventory, see Jutta Lambrecht, Das ‘Heidelberger Kapellinven-

tar’ von 1544 (Codex Pal. Germ. 318): Edition und Kommentar, 2 vols. (Heidelberg: Heidel-berg Univ., 1987); Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 115–18.

57 See Lambrecht, Das ‘Heidelberg’ Kapellinventar, 1: 182–91.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

Bavarian court chapel repertory (as Bente himself concluded). Thusthe common source with the print should also be located there. Thismakes sense when taken in relation to the transmission of CCI and theCCIII “seorsum.” These parts of the print were transmitted via Munich,and the compilers of the print models certainly had access to that insti-tution’s repertory. At issue is whether this common source containedonly the same repertory as VieNB 18745, or whether it was larger.There are at least five reasons for believing that the latter was the case.

First, VienNB 18745 offers slimmed-down and easily manageableCommon of Saints cycles. At most only two alternatives are given foreach proper-genre within each type of cycle (Virgins, Confessors, Apos-tles, etc.), and usually there is no choice at all. From a practical, liturgi-cal perspective this would not satisfy basic requirements. Seven piecesin VienNB 18745 are concordant with the “Opus musicum” manu-scripts. The “Opus musicum” preserves the original intended arrange-ment of the movements, while VienNB 18745 clearly recompiled thepieces, drawn from a large repertory, into new, smaller cycles (see Fig.2). If the relatively stable propers of the “Opus musicum” could be sub-ject to such drastic and selective reordering, there is a possibility thatthe remainder of the VienNB 18745 cycles resulted from analogousprocedures.

Second, the central mass-proper sources of the Bavarian courtchapel, the “Opus musicum” manuscripts themselves, do not containevery item required, but were supplemented with additional itemsdrawn from a Common of Saints “pool.” For instance, the feast of theDivision of the Apostles ( July 16) is covered in the “Opus musicum”only with a sequence. The introit “Mihi autem,” alleluia “Non voselegistis,” and communion “Ego vos elegi” were drawn from the Com-mon of Apostles and were shared by many other services.58 The “Opusmusicum” contains settings of none of these necessary supplements. Vi-enNB 18745 shows that two, the introit and the alleluia, were availablein the Munich Common of Saints repertory. The communion “Ego voselegi,” however, would be lacking if VienNB 18745 represented all thatwas at hand. A setting of this item is included in CCIII. Bente assignedthe latter a provenance in Constance, yet it is much more likely that itand other such necessary items were drawn from a Munich Common ofSaints pool much larger than that of VienNB 18745.

Third, the “Heidelberg” Inventory proves that the Munich Commonof Saints repertory is not fully represented in surviving manuscripts. Theinventory records an extensive five-voice Commons collection by Senfl,which does not survive. It also records three six-voice introits by Isaac

62

58 Chants as prescribed by the GP.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

for Apostles, Martyrs, and Confessors along with the rest of his knownproper-items for those forces in book “V,” fol. 7v.59 The “Heidelberg”book “V” was clearly copied from a surviving Munich manuscript,MunBS 31, yet the six-part music for the Common is not found in thatsource, nor is it extant anywhere else. This implies that items for theCommon were kept separately. Comparison with another large collec-tion of liturgical music, the Jena choirbooks, shows that Common itemsdid sometimes have a distinct manner of storage: While other mass-propers were arranged by date and assignment, the Common was pre-served by genre.60 The Choralis employed a similar arrangement, as do

63

59 See Lambrecht, Das ‘Heidelberg’ Kapellinventar, 1: 50.60 See Karl-Erich Roediger, Die Geistlichen Musikhandschriften der Universitätsbibliothek

Jena, 2 vols. ( Jena, 1935; repr. Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1985); Duffy, “The Jena Choir-books,” 6–7.

figure 2. Relationship between the “Opus musicum” and VienNB18745

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

some chant books, including the GP. This distinct storage manner ex-plains the absence of Common items in the “Opus musicum.” The Munich Common pool may have been kept unbound. Examination ofpage deterioration patterns in the Munich choirbooks shows that manywere used for some time as individual folio-manuscripts before beingbound together.61 It would clearly be much more convenient to leavemultipurpose Commons items out of the binding process. This may ex-plain why Munich sources for it have vanished.

Fourth, BerlDS 40024 attributes three communions to composersother than Isaac: CCIII/2 Comm. 1 is said to be by “G. Schach,” CCIII/2Comm. 2 by Slatkonia, and CCIII/3 Comm. 1 by “Georg Block.” Whilethe piece attributed to “Schach” is present in VienNB 18745, the othertwo are not. There is no good reason not to take these attributions seriously, for there are other pieces in the Choralis print known to be by composers other than Isaac.62 However, if these attributions are be-lieved, then they must indicate an origin for at least some pieces in theCCIII Common of Saints beyond either VienNB 18745 (the pieces by“Block” and Slatkonia are not in this source) and the Constance com-mission (which contained music only by Isaac). While the identity of“Block” remains mysterious, Slatkonia is well known and was the Imper-ial chapel master in Isaac’s time. Its most obvious transmission pathwould be via Munich. This again points to the print compilers drawingon a larger Munich repertory than that present in VienNB 18745.

The fifth item of evidence pointing to the transmission of all of theCCIII Common of Saints from a large Munich pool comes from exam-ining the music of the print’s settings itself. Bente does not considermusical features. The most basic difference between the high feasts ofCCII and all the settings in CCIII, including those Bente proposed forhis Constance Common of Saints, is that the former set their cantusfirmi in the discant, while the latter place them in the bass. The distinc-tion cannot be one of status, for the “Opus musicum” presents settingsof some high feasts with the cantus firmus in the bass. Precisely whatmotivated the difference is unclear, but stylistically it brings the wholeCommon of Saints into close alignment with the Imperial settings ofthe “Opus musicum”/CCIII “seorsum” rather than with the Constancecommission.63

Vocal scoring also differs between the Common of Saints and theCCII. The latter frequently uses both reduced and expanded groups,

64

61 See Lodes, “Ludwig Senfl.”62 See Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 105.63 The CCI Imperial propers set the chant in the discantus; Isaac’s settings with

the cantus firmus in the bass seem to date from later in his career; see Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,” 55–68.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

ranging from two to six parts. CCIII, both in the Common of Saints andin its other propers, is almost entirely in three or four parts. A duet oc-curs on only one occasion (CCIII/18, Sequ.), as does a scoring of morethan four parts (CCIII/3, Int. 3. “Iusti epulentur”).64 The latter in factprovides further evidence of the heterogeneous nature of the Commonof Saints. The introit is an entirely five-part work.65 It seems to havebeen originally composed in this scoring rather than adapted from afour-part setting.66 If it were an adaptation, it should be possible to re-move one of the parts yet still maintain an acceptable musical structure.This is not so: The bassus is the primary cantus firmus-bearing voice,with the discantus playing an important role in dialogue with it; thethree inner parts, the altus, tenor, and vagans, all have essential contra-puntal roles at some point in the piece, either preventing structuralfourths or providing cadential movement. A five-part mass-proper wouldbe unique in Isaac’s output. The text and occasion to which the introitis assigned—a regular introit for the Common of Martyrs—does notseem to merit special treatment. Nor, beyond its scoring, is the music at all elaborate. If this piece had been offered in a Constance Commonof Saints as Bente suggested, it would have stood out as very strange,just as it does within the Choralis. The “Heidelberg” Inventory offers asurprising explanation for the piece: that it is not by Isaac at all, butSenfl, the only surviving member of an extensive, no-longer-extant five-voice Common of Saints series. The series is mentioned twice in the In-ventory, once in choirbook format, and once as partbooks (see Fig. 3).Senfl’s set must have come from Munich, which is also known to havesupplied much of the other music recorded in the “Heidelberg” Inven-tory. Given, on the one hand, Munich’s central role in transmitting theChoralis, and the proven presence in CCIII of other music by Senfl aswell as by others (Slatkonia, “Schach” and “Block”), and, on the otherhand, the complete absence of any other five-part propers from Isaac,an attribution of CCIII/3, Int. 3 to Senfl does not seem unreasonable.As an introit “de martyribus,” the CCIII piece could be part of either ofthe two apparently complete services listed in the partbooks “a” orequally the isolated introit of book “CC.”

Unfortunately, it is difficult to add further arguments for or againstthis proposal at a stylistic level. Although special procedures can be de-termined to have been used only by one of the composers, none occurs

65

64 Heinrich Isaac, Choralis Constantinus III, ed. Louise E. Cuyler (Ann Arbor: Univ.of Michigan Press, 1950), 397, 99–101.

65 For further on this and the following, see Burn, “The Mass-Proper Cycles,”102–4, 255–64.

66 Heinz supposes the work to be adapted, but there is no evidence to support this;see “Isaacs und Senfls Propriums-Kompositionen,” 57.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

in this piece.67 When “Iusti epulentur” goes beyond the relatively largestylistic territory that was shared by both Isaac and Senfl, its proceduresare unusual for both. For example, both composers regularly structurepieces around a dialog of cantus firmus phrases passed between themain chant-bearing voice (the bassus) and another part. This is whathappens in “Iusti epulentur.” However, both Isaac and Senfl almost al-ways choose the tenor as the second member of the dialog pair, while“Iusti epulentur” uses the discantus.

66

67 For example, the use of unusual mensuration signs, setting the cantus firmus inodd note-values, e.g. 5 or 7 beats, and the addition of ostinato motifs are found in Isaac,but not Senfl.

figure 3. Comparison of the “Heidelberg” Inventory, fol. 9v–10 andfol. 79v–80

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

Whether “Iusti epulentur” is accepted as Senfl’s or not, its scoringis unusual and speaks against a Constance Common of Saints. This andthe other arguments mean that Bente’s proposal should ulitmately berejected. With that, we are led back to Pätzig’s original findings for theorigins of the Choralis propers. There are not currently any grounds forchallenging his conclusions. Yet there may still be a final chapter to thestory. A part of the Constance commission may hide in the Choralis in aplace no one has yet thought to look: the mass-ordinaries which closeCCIII.

A Constance Ordinary?

If it has always been supposed that the commission’s “etlich officia”is to be understood solely to refer to proper-items, a great deal of evi-dence speaks to the contrary. First, a narrow definition of the crucialword “officium” as solely denoting mass-propers is not supported bycontemporary usage. Johannes Tinctoris’s Terminorum musicae diffinito-rium gives the word a primary meaning much wider than that now attached to it in the Constance commission document. For the defini-tion, the reader is referred to elsewhere in the dictionary:

Officium idem est quod missa secundum hispalos.(Officium is the same as mass, according to the Spaniards.)68

Turning to the definition for “Missa” to which one is directed, one findsa description of the mass-ordinary, as indeed would be expected. Tinc-toris clarifies the cross-reference by mentioning, as part of the definition,that some use “Officium” as a synonym:

Missa est cantus magnus cui verba Kyrie, Et in terra, Patrem, Sanctus,et Agnus, et interdum caeterae partes a pluribus canendae supponun-tur, quae ab aliis officium dicitur.

(The mass is a large composition for which the texts Kyrie, Et in terra,Patrem, Sanctus, and Agnus, and sometimes other parts, are set forsinging by several voices. It is called the Office by some.)69

Tinctoris’s definition of “officium” is borne out by examination of theappearance of the term in other sources, both liturgical books andmanuscripts of polyphonic music. It is simply another word for “mass,”

67

68 Johannes Tinctoris, Dictionary of Musical Terms: An English translation of Terminorummusicae diffinitorium together with the Latin text, ed. and trans. Carl Parrish (London: FreePress of Glencoe, 1963), 46–47; 89n74, observes that this usage was not confined to theIberian peninsula, even if it was primarily there that it was customary.

69 Dictionary, ed. Parrish, 40–41.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

and makes no distinction between proper and ordinary. It may denoteeither, or both combined together into plenary masses. It was in this latter sense that it was used in the manuscript BerlS 40021 (ca. 1485–1500) and in the titles of two important collections issued by GeorgRhau later in the century: the Officia Paschalia de Resurrectione et Ascen-sione Domini (RISM 153914) and Officiorum (ut vocant) de nativitate, circum-cisione, epiphania Domini et purificatione &c. tomus primus (RISM 15455).

The Choralis sources, Isaac’s mass-ordinary production in general,and the liturgy itself tell us that the mass-proper and the mass-ordinarycoexisted as a larger integral unit. While 15th- and 16th-century manu-scripts often contained only ordinaries, the preservation of mass-propersin isolation is rarely the case. Ordinaries are present, for instance, in allof the Choralis sources mentioned above: WeimB A closes with at leastfour (with a possible fifth in the heavily damaged closing pages), MunBS39 contains one (appropriate to all its propers), the “Opus musicum”ends with four, VienNB 18745 presents no less than seven, and clearlythe Choralis print itself was considered incomplete without an adequateprovision of ordinary items to go with the rest. That Isaac, too, wantedto ensure that his propers had ample counterparts is reflected in his extraordinary cultivation of the alternatim mass, apparently to the ex-clusion of other mass-ordinary types, in his first ten years at Vienna. Although this mass-type was, internationally speaking, a marginal phe-nomenon, with few aspirations in comparison to the normal cantus-firmus mass at time Isaac arrived in Vienna, its foundation in plainsongin exactly the same way as mass-propers must have strongly appealed tohim. The proposal that the sections of these masses were interleavedwith organ polyphony is not certain, and they work equally well in alter-nation with chant. Still, a combination with Hofhaimer’s improvisationswould have provided a spectacularly immediate demonstration of cooperation between the two most brilliant members of the Imperialchapel.70 Taken as a whole, the alternatim masses show a thorough andsystematic exploration of an overall scheme. They group into the fol-lowing sets according to type and scoring (see Fig. 4). The existence ofthe three-voice Missa Ferialis is testified to by the “Heidelberg” Inven-tory (loose item no. 145, fol. 98v). Staehelin has suggested that it maybe identical to that found in MunBS 19.71 It is unclear whether five-and six-voice treatments for those not provided with them once existed

68

70 See William Mahrt, “The Missae ad organum of Heinrich Isaac” (Ph.D. diss., Stan-ford Univ., 1969); “Alternatim Performance in Heinrich Isaac’s Masses,” Abstracts of PapersRead at the 36th Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society, Toronto, 1970, 40.

71 See Lambrecht, Das ‘Heidelberger’ Kapellinventar, 1: 232; Staehelin, Die Messen, 1:46–50.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

and have since been lost. Such special vocal groups would presumablynot have been warranted for ferial masses, nor would three-voice set-tings of the other, more important, ordinaries.

All this strongly suggests that the delivery of a proper-series alonewould have been only a half-fulfillment of what the Constance chapterhad asked Isaac to do. A prestigious set of music for high-feast propersmust surely have demanded ordinaries worthy to accompany them. Anexamination of the sources lends tangible support to this speculation. Atransmission to CCIII via Munich, like so much of the other Choralisrepertory, might be presumed for the ordinaries, yet this is supportedin only four of the five cases. The late MunBS 47 (ca. 1550), apparentlythe end-product of a chain of in-house copies from which the earlierlinks do not survive, contains only the CCIII masses for Confessors,Apostles, Martyrs, and the Missa solemnis.72 The only other non-print-model dependent source for the CCIII ordinaries, VienNB 18745, againcontains concordances only for these same four masses. VienNB 18745must have acquired these four ordinaries and the remaining three fromthe same predecessor to MunBS 47 that was used in the transmission tothe CCIII print model. The preservation of these four alternatim massesexclusively in Munich sources, along with almost all of Isaac’s others,gives them an origin in the Imperial court, as it did with the propers ofCCI and CCIII. The lack of credos in VienNB 18745, MunBS 47, and

69

72 See Bente, Neue Wege, 180–81.

figure 4. Types and scorings in Isaac’s chant-based mass-ordinaries

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

70

presumably also its antecedants, was conventional. These movementswere drawn, according to need, from a separate Credo collection(MunBS 53), although none of the ones inserted into the masses in theCCIII print was drawn either from there or from any other survivingsource.

The CCIII Missa Paschalis, however, has a different and distinctsource situation. While 19 of the 21 alternatim ordinaries are found onlyin Munich sources, the Missa Paschalis is one of only two that are not.The other is also a Missa paschalis, for six voices, preserved only insources with a provenance from Torgau and two of the NetherlandsCourt Complex (“Alamire”) manuscripts. This suggests a special statusfor paschal masses. The unexpected absence of the CCIII Missa Paschalisin Munich sources could initially be accounted for in a variety of ways.However, its presence in another source, ZürZ 169, is suggestive. ZürZ169 also contains a part of CCII, which Schuler has shown was transmit-ted to it from Constance, via Sixt Dietrich, without relation to Vienna,Munich, or the print.73 Although the ZürZ 169 copy omits the Sanctusand Agnus Dei, it includes the Credo with this mass. In so doing, thesource is unique in providing the only prepublication source for anyCCIII Credo, suggesting the grouping was stable in a way different fromthe Imperial/Munich masses. It seems to be no coincidence that, of themost complete group of Isaac’s alternatim masses in four parts, it wasonly the Missa Paschalis that received attention twice: once, as preservedin VienNB 18745, for the Imperial court, and once, as contained inCCIII, for Constance. With this as the final piece in the argument, anew model for the transmission of CCIII may now be proposed (seeFig. 5).

Conclusion

Although the arguments put forward in this article are at times in-tricate, the conclusions are straightforward: So far as the mass-propersare concerned, no newer proposal seriously challenges Pätzig’s originalconclusion that the 25 cycles of CCII (and the Trinity Sunday service ofCCI) be viewed as the music Isaac composed for Constance cathedralin 1508–9. Within CCII, only the St. Martin service (CCII/22) leavesroom for doubt. With CCI and CCIII, sources, transmission, and liturgyall speak to an Imperial origin. However, it is also likely that Isaac’sConstance music contained (chant-based) settings of the mass-ordinary,

73 See Schuler, “Zür Überlieferung,” 150. He makes no mention of the ordinary.The ZürZ version of the Gloria is in five voices, rather than the four given in CCIII. Theadaptation was perhaps the work of the source’s scribe, Clement Hör. Staehelin, DieMessen, 3: 109, states that the extra voice was not by Isaac.

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

burn

71

and that the CCIII Missa Paschalis was also part of the commission mu-sic. The arguments necessary to lead to these conclusions brought withthem a new model for the transmission of CCIII in particular. The pres-ent article does not, of course, even touch on many of the mysteriesposed by the Choralis. It is hoped, however, that in clarifying one of itsbasic issues, research into these other areas may be undertaken with asecure foundation.

Kyoto City University of Arts

ABSTRACT

It has long been known that Henricus Isaac (ca. 1450–1517) wrotemass-propers for Constance cathedral. These are preserved in hisposthumously printed, three-volume collection entitled Choralis Con-stantinus. Yet the first generation of postwar Isaac researchers showedthat the Choralis contains music not only for Constance but for the Im-perial court as well. Since then several theories have been advanced

figure 5. Genesis of CCIII (New Model)

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

the journal of musicology

regarding the intended recipients of parts of the Choralis repertory. Thepresent paper assesses these conflicting theories. It concludes that with one small possible alteration, the original division advanced byGerhard Pätzig can stand, and that more recent proposals are not compelling. In addition, the new suggestion that Constance cathedralwould have expected not only mass-propers in their commission butalso mass-ordinaries is put forward, and a specific ordinary-settingwhich could have served this role is identified. The evaluation of theconflicting theories for how the Choralis divides leads, in the process, toa new model for the transmission of CCIII.

72

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.57 on Tue, 25 Mar 2014 10:52:37 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions