"We Honor the House": Lived Heritage, Memory, and Ambiguity at the Cathlapotle Plankhouse

Transcript of "We Honor the House": Lived Heritage, Memory, and Ambiguity at the Cathlapotle Plankhouse

"We Honor the House": Lived Heritage, Memory, and Ambiguityat the Cathlapotle Plankhouse

Jon Daehnke

Wicazo Sa Review, Volume 28, Number 1, Spring 2013, pp. 38-64 (Article)

Published by University of Minnesota PressDOI: 10.1353/wic.2013.0002

For additional information about this article

Access provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz (29 May 2013 14:17 GMT)

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/wic/summary/v028/28.1.daehnke.html

38

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

“we Honor the House”Lived heritage, Memory, and Ambiguity at the Cathlapotle plankhouse

J o n D a e h n k e

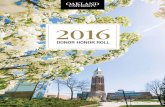

On March 29, 2005, the Cathlapotle Plankhouse constructed within the boundaries of the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) opened its doors to the public for the first time (Figure 1). The date of the grand opening was not accidental; on this date 199 years prior Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery landed their dugout canoes on the banks of the Chinookan town of Cathlapotle and visited with its inhabitants for approximately two hours. The grand opening ceremony was designed to not only celebrate and capitalize on this historic event, but also to publicly celebrate the partnership between the Chinook Nation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) archaeologists and staff, and a variety of financial supporters who made the construction of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse a reality. Additionally, volunteers had offered thousands of hours of labor to the project and the plankhouse would not have been built without their efforts. The important role that volunteers played in bringing this project to fruition was also rec-ognized during the grand opening.1

The Cathlapotle Plankhouse serves as a place of memory de-signed to provide a physical link to the Indigenous populations that once thrived in the area where the plankhouse now sits. It is also, how-ever, a place where competing visions about the past, the role and value of cultural resource stewardship, and the ownership and control of heritage come directly into focus. Further, it is the place where these

39

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

varied visions of heritage took on their most public face, especially within the context of Lewis and Clark bicentennial celebrations. The plankhouse has become a place of cultural reclamation for the Chinook Nation, a site where they hold nonpublic (and also public) tribal events, share songs and dances, and practice the protocols that are so central to who they are: a place where heritage is lived. But the plankhouse sits on lands owned and controlled by the government of the United States, and as a result the legacies and continuing manifestations of

Figure. 1. Top: Cathlapotle plankhouse located on the Ridgefield national Wildlife Refuge. Bottom: plankhouse grand opening, March 29, 2005. Author’s photographs.

40

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

colonialism are an ever- present reality that the Chinook Nation con-fronts in their use of the plankhouse and in their efforts to control their own heritage. The Cathlapotle Plankhouse is, therefore, an ambiguous monument where the legacies of both a rich tribal history and colonial-ism intersect, and where efforts to reclaim culture are hindered by lack of tribal control. The goal of this essay is to trace the development of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse as a place of memory and explore the issues that led to the battles over its use, identity, and value as a monument to heritage.

My discussion about the construction and use of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse as a place of heritage is certainly informed by a large body of scholarship on “memory.”2 It is Edward Casey’s work on the central-ity of place and its connection to memory, however, that provides the central framework. Casey argues that there are four major forms of human memory: individual memory, in which the individual person is a unique rememberer; collective memory, where different people recall the same event, each in their own way; social memory, which are memories held in common due to a group connection; and public memory, which is memory that occurs out in the open.3 While each type of human memory plays a role in shaping the other three, social memory and public memory seem most useful in understanding the issues and con-troversies surrounding the Cathlapotle Plankhouse. Casey argues that social memory has the following characteristics:

This is the memory held in common by those who are affiliated either by kinship ties, by geographical prox-imity in neighborhoods, cities, and other regions, or by engagement in a common project. In other words, it is memory shared by those who are already related to each other, whether by way of family or friendship or civic acquaintance or just an alliance between people for a spe-cific purpose. . . . Crucial here is that social memories are not necessarily public: families can harbor memories that are known only to themselves; such privacy is often itself prized as such, providing that intimacy and bonding that are so important to the maintenance of family life.4

Casey notes that “sharing memories” does not mean that members of the group have identical memories, or even the same experience of memory. What it does mean, however, is that (1) these members have had the same history (even if this is via the proxy of another family member); (2) there is a common place where that history was enacted and experienced; and (3) there is an ability to bring the “history- in- that- place” into words or other suitable means of communication and expression.5

41

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

Social memory contributes to public memory, but there are fun-damental differences between the two forms:

To begin with, by saying “public” we mean to contrast such memory with anything that takes place privately— that is to say, offstage, in the idios cosmos of one’s home or club, or indeed just by oneself (whether physically sequestered or not). “Public” signifies out in the open, in the koinos cosmos where discussion with others is possible— whether on the basis of chance encounters or planned meetings— but also where one is exposed and vulnerable, where one’s limita-tions and fallibilities are all too apparent. In this open realm, wherever it may be— in town halls, public parks, or city streets— public memory serves as an encircling horizon.6

Social and public memory often come into contact at places like the Cathlapotle Plankhouse, and Casey notes that a “medley of voices” can be heard at these sites.7 Often, however, the “medley of voices” also contains the tensions that underlie competing visions of memory, and differing views on what constitutes heritage. As will be shown in the following pages, this is certainly the case at the Cathlapotle Plankhouse.

m e t H o D o l o g I C a l n o t e

Some of the information in this essay comes from interviews with a number of individuals directly involved with the development of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse. Scott Aikin (formerly of the USFWS), Kenneth Ames (Portland State University), Mike Iyall (Cowlitz Tribe), Gary Johnson (Chinook Nation), Anan Raymond (USFWS), and Sam Robinson (Chinook Nation) were interviewed as part of this project. While all have institutional attachments, their words reflect their personal opin-ions and insights rather than serving as official statements of their re-spective institutions. In addition to these interviews I also attended numerous heritage events at the Cathlapotle Plankhouse. This in-cluded both nonpublic Chinook Nation celebrations at the Cathlapotle Plankhouse, as well as public Lewis and Clark celebrations at the same spot. In fact, my attachments to the Cathlapotle Plankhouse are both active and multiple, including conducting archaeological research within the boundaries of the Ridgefield NWR, serving as an archae-ologist for the USFWS, and developing public education and outreach materials for the plankhouse.8 Therefore, I am not a disinterested, neu-tral party, but rather someone with direct interest in and long connec-tions to the Cathlapotle Plankhouse. This essay should be read with that status in mind.

42

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

P l a n K H o U s e s I n t H e P a s t

a n D P R e s e n t

Before turning specifically to the Cathlapotle Plankhouse, it is useful to provide some context on the general importance of plankhouses in the Pacific Northwest both historically and in the present day.9 Plankhouses have been— and continue to be— a focal point for archaeological stud-ies in the Pacific Northwest. Interest in plankhouses as analytical units for archaeological studies grew dramatically during the late 1960s and early 1970s, largely as a consequence of an increasing focus on the ori-gins of “social complexity” on the Northwest Coast in particular and in “hunter- gatherers” in general during this period.10 But ethnographic interest in plankhouses started much earlier, undoubtedly due in part to the physical and aesthetic qualities of these often massive and richly decorated structures. Many of these plankhouses were quite large, and often ornately carved and painted, and therefore were the most prominent cultural feature on the landscape. Due to this visibility and artistry, plankhouses garnered the attention of the earliest European visitors to the Pacific Northwest, and Euro- American descriptions and drawings of plankhouses exist from as early as 1778 and last well into the nineteenth century.11

While early ethnographic attention to plankhouses often cen-tered on their form and construction, colonial government agents and priests tended to focus on the social relationships attached to plank-houses. This shift in focus had devastating consequences for Indigenous communities. Priests and agents often viewed the houses as immoral and actively encouraged Native populations to leave the large houses and establish smaller, single- family homes.12 They felt that the large multifamily structure of the houses— where traditional practices and values were enacted on an everyday basis— challenged the authority of the church and government and made it much more difficult to convert and control Native populations. In some cases, large cedar plankhouses were burned to the ground by order of white officials.13 As a result of this direct attack on a fundamental component of Indigenous social structure and identity, Native populations viewed the maintenance of a large, multifamily house as “an active form of resistance to the Catholic church, and the physically imposing structure of house- based dwell-ing was an important element in that resistance.”14 Over time, however, policies of assimilation and cultural genocide took their toll, and the large multifamily houses became a thing of the past.

Plankhouses, however, have made a recent re- appearance. In the last two decades numerous Northwest tribal nations have built com-munity plankhouses that serve as centers for tribal events and cultural ceremonies. For instance, in 2009 the Suquamish Tribe of Washington State opened a 6,200- square- foot longhouse on tribal lands, where

43

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

they hosted the 2009 Tribal Journeys canoe gathering of Northwest na-tions. The longhouse serves not only as a spot for tribal gatherings, but also as a source of pride and a reminder of what tribes have had to endure and just how far they have come.15 Plankhouses have also been constructed on college campuses, such as the “House of Welcome” Longhouse Education and Cultural Center at Evergreen State College (it was the first of its kind in the United States) and the Many Nations Longhouse at the University of Oregon.

Whether located in tribal communities or on college campuses, these modern plankhouses serve as culturally appropriate places of gathering and ceremony. Typically, these modern plankhouses are not designed to serve as sites of historical re- construction, but rather as places for cultural revitalization and cultural continuity. This con-tinuity is achieved through practice of appropriate protocol, and the plankhouse serves as the place where that protocol is remembered. The centrality of large plankhouses to Northwest Coast tribal identity and cultural revitalization is why the Cathlapotle Plankhouse is so impor-tant, and why it is not just another building. It is a site for community gathering and the reaffirmation of identity, a point of view stressed by Sam Robinson, vice- chair of the Chinook Nation, when he states that the central value of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse is that it is the place “where the Chinook are.”16 But unlike other modern plankhouses built on tribal lands, the Cathlapotle Plankhouse sits on federal lands, is under the purview of the federal government, and is designed to ful-fill heritage responsibilities for a larger group than just the Chinook Nation. As a result, it is a site of ambiguity.

D e v e l o P I n g t H e C a t H l a P o t l e

P l a n K H o U s e

The idea of building a Chinookan- style plankhouse within the bound-aries of the Ridgefield NWR developed in the early stages of the Cathlapotle Archaeological Program. The Cathlapotle Archaeological Program (CAP) is a partnership between the USFWS, Portland State University, and the Chinook Nation. The CAP was developed to fa-cilitate research and archaeological excavation at Cathlapotle, a large Native American village located within the floodplain of the Columbia River and on federal lands. In addition to being one of the few villages within the Portland Basin that hasn’t been destroyed by development, Cathlapotle was also considered important because it was one of the villages visited by Lewis and Clark.17 By 1995 the CAP was formally codified by a memorandum of agreement, and over the course of six field seasons the remains of at least six plankhouses, as well as thou-sands of artifacts, were recovered and cataloged.18

Kenneth Ames, an anthropologist at Portland State University

44

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

and principal investigator for the CAP, and USFWS regional archae-ologist Anan Raymond discussed the possibility of building a “re- construction” of a plankhouse shortly after excavations at the site had commenced. During the course of the excavations it became readily apparent that Cathlapotle represented an important archaeological site, but this tended to be lost on the general public, primarily due to the “featureless” nature of the archaeological footprint. There were also concerns about directing the public to a space that was relatively in-accessible on the refuge, and whether this might also lead to looting of the site. The solution to this was the construction of a plankhouse on the grounds of the refuge but away from the exact location of the site. This “re- constructed” plankhouse would provide visitors with the sense of scale and grandeur of these large structures that a visit to the archaeological excavations could not. This idea, however, was tabled as excavations proceeded and the management of the day- to- day opera-tions of the project took precedence. Additionally, there was no readily apparent source for funding such a venture at the time, and the idea was pushed to the background.19

A couple of years into the project, however, the idea of building a plankhouse at the Ridgefield NWR was again brought up. A driv-ing force behind the re- emergence of the idea was the upcoming Lewis and Clark bicentennial that would be in full swing during 2005 and 2006. It was assumed that this bicentennial would draw numerous visi-tors to the Portland area and to the Ridgefield NWR in particular, and the USFWS argued that a plankhouse on refuge grounds would serve as an excellent project for the Lewis and Clark bicentennial, and more importantly that there was the potential for funding due to the large amount of monies attached to the bicentennial events.

The idea of building the plankhouse was supported by the Chinook Nation, despite their ambivalence (and at times hostility) to-ward the Lewis and Clark bicentennial. Like most tribal nations along the Lewis and Clark trail, the Chinook Nation was concerned about their representation in the Lewis and Clark story, the undue weight given to a temporally brief expedition rather than the generations of occupation by Native peoples, and an accurate portrayal of the dev-astation that this expedition ultimately represents. They also noted the irony that Chinookan peoples helped Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery to survive their winter at the coast during 1805–6 yet re-mained federally unrecognized today.20 Despite these concerns, the Chinook Nation recognized the opportunities that the bicentennial offered. They also realized that although the plankhouse would be at-tached to the bicentennial in its formative stages, it would outlast the event and serve as a constant reminder of the presence of Chinookan peoples along the Columbia River.21 James Clifford argues that for Indigenous populations, who have a history of being marginalized and

45

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

made to disappear physically and ideologically by colonial institutions, the ability to say “We exist” publicly is a powerful political act, and the Chinook Nation felt that the Cathlapotle Plankhouse provided a place where they could say “We exist” to both the general population at pub-lic Lewis and Clark events, and to other Northwest Coast tribal nations at events like the Winter Gathering.22

The process moved forward from there as Anan Raymond and honorary Chief Cliff Schneider of the Chinook Nation attended Lewis and Clark events to pitch the idea. Meanwhile, Virginia Parks— an education and public outreach specialist working for the Region 1 Cultural Resources Team of the USFWS— searched for additional grants. An initial grant was acquired from the Hugh and Jane Ferguson Foundation, a foundation that supports nonprofit organizations dedi-cated to the preservation of nature and education of cultural heri-tage. Shortly thereafter the project also received monies from a Clark County, Washington, hotel tax fund, designed to support projects that would stimulate tourism into the area. With these early funding sources, an idea that Raymond initially referred to as a “fantasy” took its first steps toward reality.23

“ w e a l m o s t l o s t t H e m ,

o R l o s t e a C H o t H e R ” : t e n s I o n s I n

b U I l D I n g a P l a C e o f m e m o R y

Once it became apparent that funding opportunities made construc-tion of the plankhouse financially viable, the next step in the process was to create a body that would oversee the project and initiate ar-chitectural design. Issues of authenticity were a central component of the discussion from the beginning. Anan Raymond and Ken Ames envisioned a historically accurate re- construction; while the plank-house would not be an exact replica of the plankhouses that stood at Cathlapotle, it would at least be very similar based on what was known from historical accounts and the archaeological record.24 In essence, an authentic plankhouse for Raymond and Ames would be one that pro-vided visitors to the refuge a relatively accurate picture of what plank-houses and Chinookan material culture would have looked like roughly two hundred years ago.

The Chinook Nation was also concerned with authenticity, al-though their interests in authenticity were less related to direct cor-relation with the archaeological record and more to constructing a house with “social integrity.”25 For the Chinook Nation, social in-tegrity is achieved only if they guide the design and construction of the plankhouse and all ideas are run through the Chinook Nation’s Culture Committee. In addition to tribal control, the plankhouse can be authentic only if it is “representative of the ancestors.”26 This does

46

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

not, however, mean that the plankhouse must look exactly like plank-houses looked when the ancestors were living in them, but rather that all the appropriate protocols are conducted during its construction and that the house be maintained and brought to life by continued use of Chinookan people. It is protocol and lived heritage that is key to hon-oring the ancestors, not the material form of the building.

At an early stage in the design of the building the Chinook Nation’s Culture Committee expressed concern about the feasibility of constructing an authentic plankhouse in the modern world. Greg Robinson, a Chinook Nation citizen who served as project coordina-tor for the Cathlapotle Plankhouse endeavor, noted that “modern codes create a tangled web of modifications to aboriginal structures, making it virtually impossible to build a pure plankhouse.”27 Of specific con-cern were the ramifications of modern codes to a large structure with open fires and small traditional oval doors, both of which were impor-tant to protocols associated with the plankhouse. Tom Melanson, who was the manager of the Ridgefield Wildlife Refuge at that time, sug-gested that compliance with the codes would not be an issue due to the location of the project on federal lands, and eventually the Chinook Nation Culture Committee was convinced. Melanson, however, was incorrect in his assessment of the applicability of modern building codes to the Cathlapotle Plankhouse, and in the view of many members of the Chinook Nation what “ensued over the course of the next few years is a textbook example of a longstanding legacy of the government promising one thing, and delivering another.”28

Three primary issues came to the forefront: the safety of open fires resulting air quality issues, accessible doorways, and the use of volunteer labor to construct the building. The first compromise that the Chinook Nation made to building integrity centered on the issue of accessible doorways. Traditional Chinookan plankhouse doorways are relatively small and oval in shape. Such doorways, however, do not meet the standards of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Additionally, the doorways are located a few feet off the ground, and would be impossible for any wheelchair traffic. Greg Robinson, how-ever, noted that “in the past, we simply would have carried our disabled people into the houses, but such simplicity has no place in the world of code application.”29 The Chinook Culture Committee decided, how-ever, that an ADA door would serve disabled members of the commu-nity and they therefore agreed to change the design of the building to incorporate both a wheelchair accessible doorway and an interior ramp (Figure 2). Lighted exit signs were also installed over the door-ways, with the exception of the traditional doorway, which was to have a “This Is Not an Exit” sign placed above it. The Chinook Nation con-sidered this sign above a traditional door as a great insult.30 Fortunately, USFWS officials decided that this sign was not necessary.

47

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

A second issue that arose was the involvement of volunteer per-sonnel in constructing the building. Volunteers, most of whom came from the surrounding communities, were an integral component of the project. More than 100 volunteers participated and together they logged over 3,500 hours of labor. During organized “work parties,” vol-unteers gathered to help with the fabrication of the wall planks, notch and shape upright beams, and paint the ridgepole. Nearly all the wood materials in the house were fabricated by volunteers.31 When it came time for the actual erection of the structure, however, safety engineers

Figure 2. Top left: Traditional door at the Cathlapotle plankhouse. Top right: ADA door next to the traditional door. Bottom: ADA- required wheelchair ramp. Author’s photographs.

48

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

with the USFWS determined that volunteer labor could not be used and that this portion of the project would need to be handled by pro-fessional contractors. Many members of the Chinook Nation, however, saw this as another moment of broken promises and a threat to the in-tegrity of the building. In their view, these volunteers had given a gift to the tribe in the form of labor, and to banish them at this critical junc-ture of the project was a breach of protocol.

Perhaps the greatest challenge was the use of fires within the plankhouse. In traditional Chinookan fashion the building was con-structed with large hearth boxes running down the central axis. The hearth boxes were the heart of the structure and were used for cook-ing, warmth, and light. The hearth was also a community center, where people gathered to eat, socialize, and tell stories, especially during the long, dark, rainy winters of the Pacific Northwest. Fires had initially been allowed in the Cathlapotle Plankhouse and were lit and kept burning during the grand opening ceremonies (Figure 3). Safety en-gineers from the USFWS, however, soon prohibited the use of fires within the plankhouse. Their concerns were twofold: first, they wor-ried about plankhouse visitors accidentally falling into the hearth pits and fires, and second, they were worried about meeting Environmental Protection Act (EPA) air quality standards due to the levels of smoke in a “confined” structure. For both safety and legal reasons the burning of fires within the plankhouse was prohibited until these concerns could be addressed to the satisfaction of safety engineers.

The prohibitions on open fires did not sit well with the Chinook Nation. They felt that they had been given assurances from other USFWS employees that fires would not be an issue and were dismayed that now “the safety and engineering branch of the FWS began to emerge as players in the developing direction of the plankhouse.”32 For them it was also not simply a question of aesthetics, light, and warmth. As Sam Robinson notes, “That’s the life of the house, you know, is fire. And you have got to have that fire to really bring that house to life.”33 Fires were an essential part of ceremonial protocol, including the use of fires to stretch drums for songs. The prohibition against fires would dramatically hinder what the Chinook saw as the primary value of the structure: a place where they could enact cultural revival through the performance of appropriate cultural practice.

Anan Raymond was also concerned and upset that safety and en-gineering professionals emerged as players in plankhouse construction at a relatively late stage in the process. He stated that initially he did not expect that fires in the plankhouse would be a significant or in-surmountable problem, primarily due to the historic and educational nature of the structure. He also admits, however, that this assumption was a bit naïve:

49

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

The conception and creation of the plankhouse was, at least initially, an organic thing, created by people who had no experience in building buildings on a national wildlife refuge. In hindsight we were naïve. But, at the same time we were concerned and upset that as the prospect of erect-ing and finishing this house was near we learned from the engineering/safety office of the USFWS that burning a fire or fires inside this building was not a simple proposi-tion. And in retrospect it’s clear that we probably should have been able to anticipate this. . . . It’s a commonsense thing when you think about it, the USFWS is a big federal agency and a big federal bureaucracy, and the idea of hav-ing a big structure with a large open fire inside it and a lot of people, a lot of members of the general public standing around kicking sticks into the fire, well, it’s something that doesn’t come easy. We didn’t plan for that.34

To answer questions surrounding EPA air standards, USFWS personnel undertook a number of experiments to test air quality within the plankhouse. The plankhouse was built in traditional Chinookan style, with a smoke hole in the roof above the fire and gaps in the wall planks to encourage draw and circulation. The initial experiment

Figure 3. Fires burning at the plankhouse grand opening. The drums near the fire are being tuned by the heat, as the skin is tightened across the drum frame. Author’s photograph.

50

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

demonstrated that the air quality within the plankhouse met EPA stan-dards even when the fires were burning. Engineering personnel were concerned, however, that the initial test was conducted under non-standard conditions (there were only a few people in the building at the time) and that air circulation and quality could change if there were more individuals in the plankhouse. A second test was conducted, this time with more than eighty people in the plankhouse, and again air quality met EPA standards. Engineers then suggested that the weather could play a role in air circulation and that experiments would need to be conducted under differing weather conditions. Alternatively, they suggested that fans (which the Chinook Nation stated would be un-sightly and noisy) could be installed in the plankhouse smoke holes to ensure that smoke would be drawn from the fires. These fans proved to make no difference for air quality, and were ultimately removed from the plankhouse.

What the tests really demonstrated was that the most efficient evacuation of smoke from the structure came from simply leaving it alone. Gary Johnson, former tribal chair of the Chinook Nation, was certainly not surprised that the knowledge of hundreds of generations of ancestors had created structures that worked well. He also joked about all the safety issues, and stated that “our ancestors lived for a long time and I don’t think they suffered any from not having an exit sign, or worried about falling in the fire.”35 USFWS safety engineers remained unsatisfied, however, and were not willing to accept this knowledge of generations, despite the results from the air quality experiments. The is-sues surrounding the ADA and EPA were serious, however, and resulted in the resignation of some members of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse proj-ect steering committee. The Chinook Nation also nearly pulled out of the project entirely, and Anan Raymond states that “it was definitely painful at times . . . we almost lost them, or lost each other.”36

Tensions surrounding the use of fires inside the house came to a head during one of the public Lewis and Clark events at the refuge. On November 5, 1805, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery first sighted the village of Cathlapotle as they headed downriver. While they did not stop at the village on their downriver trip, they were met on the water by village residents who came out to speak and trade with them. The bicentennial of this event was re- enacted on November 5, 2005, by citizens of the Chinook Nation and members of one of the Lewis and Clark re- enactment groups re- tracing the voyage (Figure 4). It was a cold and rainy November day, miserable in the way that only a cold, rainy, Washington November day can be. The re- enactment of the “first meeting” was to be followed by ceremonies and a feast in the plankhouse. But since fires were not allowed in the plankhouse by USFWS safety engineers, spectators and participants in the event, who had just spent more than an hour outside in the rain, entered a cold and

51

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

damp building. It was not a comfortable experience, and in fact even potentially dangerous as there were fears that some participants might become hypothermic. This was a source of frustration and anger for the Chinook Nation:

The biggest problem we have with that is that they don’t allow fire in there. And it was that November where we did the re- enactment with the Lewis and Clark people and

Figure 4. Re-enactment of the Lewis and Clark/Cathlapotle “first meeting,” november, 2005. Author’s photographs.

52

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

we came back and our elders were freezing and the drums were soft and we were soaked and there was no fire. . . . And on that day we put our foot down and said we will not have any tribal/public events at that plankhouse until you resolve the fire issue.37

The “fire issue” is still not resolved. Although the Chinook Nation builds fires in the plankhouse during its nonpublic tribal events (to the chagrin of some employees of the USFWS), “no fires allowed” remains the official policy during public events.

Anan Raymond argues that one of the driving forces behind the types of difficulties encountered during the course of the plankhouse project stems from the organic nature of large bureaucracies like the USFWS. The project developed within the minds of a few individuals, and all the early stages of planning occurred within a relatively com-fortable and confined body of people. But as the process grew the dy-namics changed:

It was an organic process that began with lower level staff people and members of the Chinook Tribe. As the plank-house project grew . . . it worked its way up the chains of the agency. . . . By then it worked its way up the bureau-cracy and the people who really had the authority in the agency and can effect that . . . they came back and said, “Wait a minute here, not so fast.”38

The result was that the ground rules and visions for the plankhouse that were initially established among a small group changed along the way. The Chinook Nation viewed this change as yet another example of continued colonialism as the federal government promised one thing but delivered another.39 Anan Raymond understands the tribe’s concern and notes that “the tribe felt like the rules had been changed mid- stream . . . and I suppose that is exactly correct, that is what did happen.”40

“ a t e m P l e t o s o m e b o D y e l s e ’ s g o D

o n t H e a l t a R o f m y C H U R C H ” :

C o w l I t z e x - / I n C l U s I o n

Fires, air- quality, and ADA doors were not the only controversies sur-rounding the Cathlapotle Plankhouse. Before the plankhouse had been constructed the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Longview, Washington, had contested the designa-tion of the Cathlapotle archaeological site as the remnants of a Chinook Village, arguing instead that the village was Cowlitz or at the very mini-mum not directly associated with the modern- day Chinook Nation.41

53

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

The Cowlitz Tribe’s claim to the site of Cathlapotle sparked a difficult and often emotional struggle over the sites of heritage located within the boundaries of the Ridgefield refuge, and this included the develop-ment, interpretation, and control of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse.

In the wake of federal recognition in 2002, the Cowlitz Tribe insisted that their voice be heard at the refuge and this included par-ticipation in the planning, construction and interpretation of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse. Their primary concern was that the USFWS was presenting the plankhouse as an exclusively “Chinookan” structure and that the Chinook Nation was given full control over the use of the plankhouse. Additionally, they noted that plans for the plankhouse did not include any acknowledgment or memory of a Cowlitz presence in the area.42 They threatened to block funding for the plankhouse unless they were recognized as full partners in the project.

The Washington Department of Transportation (DOT) had awarded the USFWS a $220,000 grant to assist in building the plank-house. The Cowlitz Tribe protested this award, arguing that there were questions about cultural affiliation and that they were not being al-lowed to participate. They were able to convince an advisory commit-tee of the Washington DOT that the grant needed to be placed on hold until the issue could be resolved. This put the Cathlapotle Plankhouse Project on hiatus and Chinook citizen Greg Robinson, the project co-ordinator, was temporarily laid off.43 Also at risk were matching funds through the Meyer Memorial Trust and M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. Anan Raymond was not willing to accede to the Cowlitz Tribe or diminish the Chinook Nation’s primacy in the plankhouse. Some USFWS employees felt that the actions of the Cowlitz Tribe made them feel like they were being “strong- armed.”44 Mike Iyall, former Director of Natural and Cultural Resources for the Cowlitz Tribe, viewed it dif-ferently, however, suggesting that the Cowlitz Tribe simply wanted to be recognized and included, and stated that the lack of inclusion of other tribal organizations at the plankhouse is viewed as an abrogation of sovereignty:

I think that for us it seemed to be a them- or- us choice. For instance, today the Chinook Nation is given control of the interior of the plankhouse. We can’t access it. We were told that the interior of the plankhouse belongs to the Chinook tribe by Fish and Wildlife Service people. I mean, how does that make you welcome? You know, it doesn’t . . . to me the presence of the plankhouse, the way it’s cur-rently signed and marked by the Fish and Wildlife Service is— it’s a temple to somebody else’s god on the altar of my church. That’s the way I see the plankhouse. It’s not an asset to us. We’ve been excluded from it, we’ve been made

54

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

to feel like outsiders around it. I had worked to try and find inclusion for us and everybody else that would have used the plankhouses in the area. I’ve had no success. When you hear the term Chinookan, they never used the names of any of the other tribes of the area. For us, the plank-house itself is— somebody used the phrase earlier this year “putting your thumb in their eye.” Well, to us the presence of that plankhouse is a discomfort because it’s a place where we are forced out of, denied recognition to, and, you know, for that reason it’s just a source of frustration.45

For Iyall the position that the USFWS took regarding the plankhouse demonstrated that “they would rather throw away a quarter of a million dollars than let us be involved.”46

Citizens of the Chinook Nation were not happy about the Cowlitz’s claims regarding Cathlapotle, and especially their desire to consult on the construction of a Chinookan- style plankhouse. They also felt that federal archaeologists seemed too eager to simply appease the Cowlitz and their wishes, a position that was not lost on USFWS archaeologist Anan Raymond:

They were disillusioned that the agency was yielding to what appeared to be unreasonable demands or state-ments or positions by the Cowlitz Tribe. They were dis-illusioned, one, because it violated the consensus under-standing of history and culture, and two, because it sort of violated the long- standing relationship that we had with them. And I think they were objecting also, from a po-litical perspective, in that Cathlapotle and the plankhouse represented a bit of a toehold that the Chinook tribe has in expressing their culture in the Vancouver area. And to somehow lose this by the federal government yielding to a shouting federally recognized Cowlitz Tribe would just be the ultimate indignity.47

Although the Chinook Nation had been a consulting party since the inception of the Cathlapotle Archaeological Program, they threatened to pull out of the project entirely if the Cowlitz were included as a con-sulting party on the plankhouse.

A series of meetings and negotiations between the USFWS, the Chinook Nation, and the Cowlitz Tribe followed, although the Chinook Nation declined to participate directly in any meetings in which the Cowlitz Tribe was present. Negotiations between the Chinook Nation and the USFWS proceeded within the framework of a fourteen- year partnership, which proved invaluable as trust and solid friendships had

55

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

been built during this period. Negotiations with the Cowlitz Tribe, however, proved more difficult as there were no previous relationships on which to build. The meetings between the USFWS and the Cowlitz Tribe stalled. The inclusion of David Nicandri, a neutral third party from the Washington State Historical Society, and Scott Aikin, tribal liaison for the USFWS, introduced a sense of stability and calm to the negotiation process, and negotiations soon moved forward.

The tangible result of the negotiation was a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the USFWS and the Cowlitz Tribe. This document codified the relationship between the two parties and created a protocol for future cooperation. The MOU stated that the USFWS would “recognize that the Cowlitz are entitled to equal par-ticipation in the development, planning, and production of educational and interpretive materials relevant to the presence of the Cowlitz Indians in the area of the refuge” and stipulated that representatives of the Cowlitz Tribe would be included on the cultural interpretation and education steering committee of the refuge.48 The MOU also stated that the term “Chinook” would not be used to describe the residents of Cathlapotle and the terms “Cathlapotle Nation” or “Cathlapotle Chinookans” would be used instead. This was an important point for Mike Iyall and the Cowlitz Tribe, who feel that the use of the term “Chinook” falsely creates in the mind of the public a direct link be-tween the people of Cathlapotle and the modern- day Chinook Nation without addressing the historical complexities of identity within the region.49 The MOU also made clear, however, that the inclusion of the Cowlitz in the project was not exclusive to the involvement of other interested tribes, and that the technical aspects of the plankhouse con-struction would continue to be guided by Kenneth Ames in consulta-tion with the Chinook Nation.50

An MOU between the USFWS and the Chinook Nation was also instituted. This agreement noted that other interested tribes could be involved in the planning and operation of interpretive and educational materials for the cultural resources of the refuge. Most important, how-ever, the MOU clearly stated that the Chinook Nation “is the principal organization that exclusively embodies and perpetuates the traditional and modern culture of the Chinookans of the greater lower Columbia River, including the Cathlapotle Chinookans who historically lived on what is now the Refuge.”51

Although the MOUs managed to advance the process of build-ing the plankhouse, no one was entirely satisfied with the results. Mike Iyall argued that the USFWS continued to ignore the government- to- government relationship that is required due to their recognized status and failed to consistently involve them in consultation. Iyall also believed that a pro–Chinook Nation bias was present in USFWS publications and that archaeologists were not doing enough to inform

56

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

the public of a Cowlitz history in the region. He also stated that all he and the Cowlitz Tribe asked for was inclusion on the plankhouse project, that it serve as a regional plankhouse for all the tribes, and that “the official name of the people that lived at the plankhouse be what Lewis and Clark called them, ‘the Cathlapotle Nation.’”52 Instead he claimed that the Chinook Nation retained control of the plank-house, that Cowlitz inclusion with the educational material “never happened,” and that many people associated with the plankhouse weren’t aware of the terms of the MOU and treated the Cowlitz like threatening out siders when they came to the plankhouse, “so . . . even-tually you don’t go back.”53

Citizens of the Chinook Nation were also unsatisfied. Despite the re- affirmation of their voice as a consulting party, many Chinook saw any questioning of their role at Cathlapotle as part of a larger con-tinued attack on their sovereignty and a reflection of their lack of feder-ally recognized status. Former tribal chair Gary Johnson and current vice- chair Sam Robinson both note that there was certainly some dis-pleasure that members of the Cowlitz Tribe sit on the educational com-mittee for the refuge, and they feel that the Cowlitz should not have a voice on educational materials concerning what they strongly believe is Chinookan territory.54 Tensions over the plankhouse have lessened in recent years, however, and the Cowlitz Tribe attends tribal events at the Cathlapotle Plankhouse, such as the Winter Gathering. Additionally, Gary Johnson wants it to be very clear that “these problems certainly should not be portrayed as one tribe pitted against another, because the problem developed with the U.S. government.”55 In this sense the tensions at the plankhouse reflect the long- term entanglements created by colonialism, the devastation of disease and displacement along the Columbia River, and the struggles that both the Chinook Nation and Cowlitz Tribe have faced in asserting their sovereignty and identity.

“ w e H o n o R t H e H o U s e ” : t e n s I o n s I n

s o C I a l a n D P U b l I C m e m o R y

What the Cathlapotle Plankhouse represents as a place, in part, is a clash between social and public forms of memory that were described earlier in this essay. The Chinook Nation certainly sees a public memory value to the plankhouse. In many ways Chinookan populations of the Portland Basin were erased from public memory. Devastation of dis-ease, policies of assimilation, and theft of land led to a silencing of their presence in this region. And when they were remembered it was usu-ally in the context of an extinct or removed group of people. Part of the goal of the plankhouse, then, is to serve as a reminder of the former presence of Chinookan people in the region and an opportunity to ex-press that Chinookan people are still there.

57

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

But discussions with tribal members suggests that for the Chinook Nation the most relevant purpose of the plankhouse is to serve as a place for social memory, and a place where they can exercise their cul-ture as they see fit and practice their culture in private. In this sense, the plankhouse serves as a place for revitalization of cultural practice and insurance of cultural continuity. This purpose for and value of the plankhouse is demonstrated clearly in events like the Chinook Nation Winter Gathering, a tribally controlled nonpublic event where the Chinook invite other Pacific Northwest tribes to share their songs and dances, and where these other tribal nations recognize and reify the place of the Chinook (despite their lack of federal recognition). In this event protocol is central, ancestors are honored through song, dances, and feasts, and the presence of the federal government fades into the background. It is because of events like this that the Chinook Nation tends not to call the Cathlapotle Plankhouse a “re- construction.” Rather than representing a long- gone snapshot in history, the plankhouse is a place for gathering and an embodiment of cultural practices and proto-cols that continue to exist, and in fact ensure cultural survival into the future. It represents a place of lived heritage.

The value of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse for Chinookan social memory is hindered, however, by its role as a place of public memory. For instance, the USFWS views the primary function of the plankhouse as a place where the agency can engage the visitor on the natural and cul-tural history of Ridgefield NWR and the immediate surroundings.56 The plankhouse serves as a monument to federal cultural resource steward-ship and education: it is fundamentally a public resource. Further, while the plankhouse was designed to outlive the Lewis and Clark bicentennial event, which served as the impetus for the project, there is little question that the Cathlapotle Plankhouse and village will remain tethered to Lewis and Clark in the minds of visitors and local residents. The plankhouse is a public monument inextricably associated with Lewis and Clark, and signs and paintings throughout the town of Ridgefield help to perpetuate this connection (Figure 5). As a result, the stories of Chinookan legacies in the Portland Basin remain juxtaposed with an American master nar-rative of expedition and progress: a two- hour visit by Lewis and Clark on a March afternoon in 1806 garners equal attention to generations of Chinookan occupation on the landscape prior to Euro- American contact. And while some members of the Chinook Nation continue to speak at public events at the plankhouse, they often feel pressure to cater their message to present a more benign story. As Chinook Nation citi-zen Sam Robinson notes, “Where in [speaking about] Lewis and Clark you never want to exclude anybody or step on anyone’s toes . . . it seems like every time I talk . . . I get that feeling that sometimes the Fish and Wildlife people are kind of cringing that I might say something that goes up against what they’re trying to do.”57

58

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

Many citizens of the Chinook Nation are also concerned about control of access to the plankhouse and the transition of private social memory into a place of public memory. As part of the MOU drawn up between the USFWS and the Chinook Nation, the tribe does have some control over who accesses the plankhouse and what events can occur there.58 This authority is limited, however, and ultimate con-trol of access resides with the USFWS. Of additional concern is the appropriation by the wider public of cultural knowledge held by the group. For instance, the carvings and paintings in the plankhouse were designed by Tony Johnson, a Chinook artist, and are based on traditional Chinookan designs (Figure 6). These designs, however, are now owned by the USFWS, as well as being widely accessible for photography and reproduction by the public. This raises intellectual property concerns and the realization that this work possibly repre-sents more than just public art. The Chinook Nation addressed these concerns in part by leaving some of the more culturally significant and powerful designs out of the plankhouse.59 Still, there remains the con-cern that Chinookan culture will be appropriated, or at the very least that the Chinookan designs at the plankhouse will become divorced from the Chinookan peoples living today.

Finally, as a place of public memory the Cathlapotle Plankhouse is somewhat “displaced” as a center for Chinookan social memory. It is a monument that sits on lands that were once densely populated by Chinookan- speaking peoples. These lands, however, are now public and the property of the U.S. government. Further, control and access to the plankhouse must be mediated through the bureaucracy of a colonial

Figure 5. Sign in Ridgefield, Washington, emphasizing the connection be-tween Cathlapotle and the Lewis and Clark expedition. Author’s photograph.

59

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

institution. For the Chinook Nation the ultimate goal is to construct a plankhouse on their own lands, where they exclusively control the design, construction, access, and interpretation of their own culture: a properly placed site for social memory. This was, in fact, one of the primary reasons Greg Robinson agreed to become part of the project: “One of the reasons I became involved was to learn the process of constructing a plankhouse, so that in the future, when we were ready, the tribe could construct a similar plankhouse on our own land near the mouth of the river.”60

Figure 6. “Ancestor” carving in the Cathlapotle plankhouse designed by Tony Johnson, Chinook nation citizen and artist. Author’s photograph.

60

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

Sam Robinson hopes that once the Chinook Nation is restored as a federally recognized tribe that they will have the resources to con-struct a number of plankhouses at the mouth of the Columbia River, all located on tribal land, and under complete control of the tribe.61 But despite these hopes for the future, Robinson asserts that the value and importance of the Cathlapotle Plankhouse should not be dismissed, and that its presence on the refuge does not preclude the house from being a place of Chinook heritage:

The plankhouse today is totally respected by the tribe . . . we honor the house, we honor our ancestors in the house, the house has a life because we do have tribal events, we do have fires. We bring that place to life in our Winter Gathering or our canoe family meetings and so forth. We’re pretty proud of that plankhouse, you know, very, very proud of the plankhouse. We invite other tribes in to show off the plankhouse. You know, at our Winter Gathering there were over eleven different nations in the plankhouse. . . . It would be nice to get rid of some of those exit signs and so forth, but I think we kind of ignore all of that when we’re in there and we really get going and we’re sharing songs and dance and so forth. So, there is a strong connection to that plankhouse. A very, very strong con-nection to that plankhouse. . . . If we build another house somewhere else it’s going to be a little bit different, but we’ll always respect that house because it does have life. Our ancestors have been in that house, you know. We’re not going to dump the plankhouse for another site. It’s just that the federal government can make it tough on you to exist as much as you want to there.62

For now, however, due to its displacement the current plankhouse stands as an ambiguous monument, and for the Chinook Nation it represents, in a single place, both the legacies of a rich heritage and a reminder of continued colonialism.

A u t h o r B i o g r A p h y

Jon Daehnke is a visiting assistant professor in American studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His research focuses on cultural heritage law, public representations of heritage and memory, and critical approaches to landscape. He is working on a manuscript that explores the dynamic and contested nature of Indigenous iden-tity, federal recognition, and tangible and intangible heritage on the Columbia River.

61

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

N o t e s

1 A “Volunteer Appreciation Gala and Preview” open only to vol-unteers, Chinook Nation tribal members, and USFWS staff was held a few days prior on March 26. The public grand opening event, however, also recognized the im-portant role of volunteers in the project.

2 See Craig E. Barton, ed., Sites of Memory: Perspectives on Architecture and Race (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001); John Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patrio-tism in the Twentieth Century (Prince-ton: Princeton University Press, 1992); Paul Connerton, How Socie-ties Remember (Cambridge: Cam-bridge University Press, 1989); Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, trans. Lewis A. Coser (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991); Ed-ward T. Linenthal, The Unfinished Bombing: Oklahoma City in American Memory (Oxford: Oxford Uni-versity Press, 2001); Kendall R. Phillips, ed., Framing Public Memory (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2004); Patricia Rubertone, ed., Archaeologies of Placemaking: Monuments, Memories, and Engagement in Native North America (Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press, 2008).

3 Edward S. Casey, “Public Memory in Place and Time,” in Phillips, Framing Public Memory, 20–26.

4 Ibid., 21–22.

5 Ibid., 22.

6 Ibid., 25.

7 Ibid.

8 Jon Daehnke, Cathlapotle . . . Catch-ing Time’s Secrets (Sherwood, Ore.: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2005).

9 While many Northwest Coast archaeologists tend to use the term “plankhouse,” many Native American/First Nations groups prefer the term “longhouse.” See D. Ann Trieu Gahr, Elizabeth A. Sobel, and Kenneth Ames, “Intro-duction,” in Household Archaeology on the Northwest Coast, ed. Eliza-beth A. Sobel, D. Ann Trieu Gahr, and Kenneth Ames (Ann Arbor, Mich.: International Monographs in Prehistory, 2006), 5. I pri-marily use the term “plankhouse” in this essay for two reasons: the official name of the Ridgefield NWR house is the “Cathlapotle Plankhouse,” and citizens of the Chinook Nation typically refer to it as a plankhouse rather than a longhouse.

10 Trieu Gahr, Sobel, and Ames, “Introduction,” 3.

11 See J. C. Beaglehole, ed., The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press/The Hakluyt Society, 1955); Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1968); Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedi-tion: Volume 5 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988); Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: Volume 6 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990); Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: Volume 7 (Lincoln: Uni-versity of Nebraska Press, 1991); James G. Swan, The Northwest Coast; Or, Three Years Residence in Washing-ton Territory (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972).

12 Yvonne Marshall, “Transforma-tions of Nuu- chah- nulth Houses,” in Beyond Kinship: Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies, ed. Rosemary A. Joyce and Susan D. Gillespie (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 88.

62

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

N o t e s

13 See Noel Purser, “Bringing Back the Canoe: A Suquamish Story,” Tribal Canoe Journeys, August 2009, 8–9; Derek Sheppard, “New Longhouse Opens for Suquamish Tribe,” Seattle Times, March 11, 2009, accessed March 15, 2009, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/ html/localnews/2008842398_ apwasuquamishlonghouse .html?syndication=rss.

14 Marshall, “Transformations of Nuu- chah- nulth Houses,” 88.

15 Sheppard, New Longhouse Opens for Suquamish Tribe.”

16 Sam Robinson, interview by author, August 18, 2009.

17 Moulton, Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: Volume 7, 26–31.

18 K. M. Ames, C. M. Smith, W. L. Cornett, E. A. Sobel, S. C. Hamilton, J. Wolf, and D. Raetz, Archaeological Investigations at 45CL1 Cathlapotle (1991–1996), Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge, Clark County, Washington: A Preliminary Report (Sherwood, Ore.: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Cultural Re-source Series Number 13, 1999).

19 Anan Raymond, interview by author, March 6, 2007.

20 On January 3, 2001, U.S. As-sistant Secretary of the Interior Kevin Gover signed documents granting the Chinook Nation formal recognition. In July 2002 the Assistant Secretary of the Interior under the new George W. Bush administration, Neal McCaleb, notified the Chinook Nation that they had failed to meet three of the seven criteria required for federal recogni-tion. Chinook recognition was rescinded. See Jon Daehnke, “A ‘Strange Multiplicity’ of Voices: Heritage Stewardship, Contested Sites, and Colonial Legacies on the Columbia River,” Journal of Social Archaeology 7 (2007). The

federal acknowledgment process is fraught with complexity and ambiguity, and the seven criteria that tribal nations must meet place strong emphasis on dem-onstrations of continued tribal continuity and identity. Notions of “identity,” however, are often stereotypical, and continuity can be difficult to demonstrate, especially due to the devastating toll of post- contact disease and long- standing policies of assimila-tion. See discussions in Bruce G. Miller, Invisible Indigenes: The Politics of Nonrecognition (Lincoln: Uni-versity of Nebraska Press, 2003); Mark E. Miller, Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004). Washington state repre-sentative Brian Baird introduced the Chinook Nation Restoration Act (HR 6689) to the U.S. House of Representatives in July 2008, during the 110th Congress. The bill was reintroduced in the 111th Congress (HR 3084), but is cur-rently stalled.

21 Sam Robinson, interview by author, August 27, 2008.

22 James Clifford, “Looking Several Ways: Anthropology and Native Heritage in Alaska,” Current Anthro-pology 45 (2004): 9.

23 Raymond interview.

24 Ibid.

25 Gary Johnson, interview by author, September 5, 2006.

26 Robinson interview, 2008.

27 Greg Robinson, “The Cathlapotle Plankhouse Project: A Bittersweet Victory,” Chinook Tillicums: The Voice of the Chinook Tribe, Fall 2004, 1.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid., 3.

63

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

N o t e s

31 Raymond interview.

32 Robinson, “Cathlapotle Plank-house Project,” 3.

33 Robinson interview, 2008.

34 Raymond interview.

35 Johnson interview.

36 Raymond interview.

37 Robinson interview, 2008.

38 Raymond interview.

39 Robinson, “Cathlapotle Plank-house Project,” 1.

40 Raymond interview.

41 See Daehnke, “A ‘Strange Multi-plicity’ of Voices”; and Daehnke, “Utilization of Space and the Politics of Place: Tidy Footprints, Changing Pathways, Persistent Places, and Contested Memory in the Portland Basin” (PhD diss., University of California, Berke-ley, 2007).

42 Mike Iyall, interview by author, July 25, 2006.

43 See Dean Baker, “Cowlitz Want Role in Plank House,” Vancouver Columbian, February 18, 2004; Foster Church, “Plank House Work to Resume: Grants Will Allow Construction to Begin Again on the Cathlapotle House After Protests by the Cowlitz Tribe Stopped Work,” The Orego-nian, March 3, 2004.

44 Scott Aikin, interview by author, July 14, 2006.

45 Iyall interview.

46 Ibid.

47 Anan Raymond, interview by author, January 9, 2006.

48 “Memorandum of Understanding Between the U.S. Fish and Wild-life Service and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe,” copy of the MOU

filed at the USFWS Cultural Re-sources Team Office, Sherwood, Oregon.

49 Delineating tribal identity in the Pacific Northwest can be particu-larly complex, both pre- and post- contact. Prior to contact the larg-est political unit of organization was typically the village, rather than broader regional organiza-tion. Additionally, villages were often polylingual, with high levels of intermarriage between com-munities. As a result, individuals had a number of interconnections within and across villages and a multiplicity of identities. See Yvonne Hajda, “Regional Social Organization in the Greater Lower Columbia, 1792–1830” (PhD diss., University of Wash-ington, 1984). Colonial actors, including government agents and ethnographers, struggled with this complexity of identity and at-tempted to impose their own sim-plified views of tribal boundaries (most often based on language) to suit their own administrative purposes. For an excellent discus-sion of the issue slightly upriver from Cathlapotle, see Andrew H. Fisher, Shadow Tribe: The Making of Columbia River Indian Identity (Se-attle: University of Washington Press, 2010). In part, the Cowlitz Tribe argued that the USFWS, by presenting Cathlapotle as a “Chinook” village, was not recog-nizing the multiplicity and com-plexity of tribal identity along the Columbia River. For further dis-cussion see Daehnke, “A ‘Strange Multiplicity’ of Voices.”

50 “Memorandum of Understanding Between the U.S. Fish and Wild-life Service and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe.”

51 Ibid.

52 Iyall interview.

53 Ibid.

64

Sp

RI

ng

2

01

3

W

IC

AZ

O

SA

R

EV

IE

W

N o t e s

54 Johnson interview; Robinson interview, 2008.

55 Johnson interview.

56 Raymond interview, 2007.

57 Sam Robinson, interview by author, July 25, 2010.

58 “Memorandum of Understanding Between the U.S. Fish and Wild-

life Service and the Chinook Indian Tribe.”

59 Aikin interview.

60 Robinson, “Cathlapotle Plank-house Project,” 3.

61 Robinson interviews, 2008, 2009, 2010.

62 Robinson interview, 2008.