Ursula: The Life and Times of an Aristocratic Girl in Santiago, 1666-1678

Warfare & Society book 2006, Vandkilde, H: “Warfare and Gender according to Homer: An Archaeology...

Transcript of Warfare & Society book 2006, Vandkilde, H: “Warfare and Gender according to Homer: An Archaeology...

The constitution of Homeric society is the mainfocus of this article, which in particular highlightsaspect of gender, warfare, and materiality. The under-lying expectation is that such a study may ultimate-ly lead to a better understanding of the social worldof the illiterate Bronze Age north of the Alps. Asocial study of Homer1 can, it may be argued, formthe basis of a contextually based comparison withBronze Age societies in temperate Europe, using theprinciple of relational analogy (Wylie 1985; Ravn1993). However, such a comparative enterprise isnot the immediate objective of the present study,which merely aims at calling attention to the exis-tence of such a potential. The issue of ideology,which is important in Homer’s epics as well as incurrent archaeology, will receive a few theoreticalcomments at the end of the article.

The Research Council project ‘War and Society.Archaeological and Social-Anthropological Perspectives’has put me on the track of past war heroes, martialideologies and, not least, military societies or warriorbands. Evidently the warrior role has a strong influ-ence on our understanding of European prehistory(Vandkilde and Bertelsen 2000; Vandkilde 2003).When we speak of war and warriors we are not onlyspeaking of social organisation, ideology, prestigeand power, but also to a great degree of gender.

More or less exclusive men’s clubs, encompassedby the German term Männerbünde, exist in manysocieties, often with a strong martial strain (Mallory1989: 110f; Ehrenreich 1997: 117ff; Vandkilde chap-ter 26). To be a warrior is therefore a demonstrationof a specific male identity, which, of course, cannotbe assessed without including other gender identi-ties: all in all, the specific social context cannot beignored.

It is central to the discussion undertaken that thewarrior identity can only be understood in its socialcontext against the background of other social iden-tities and confronted with the current warrior ideal.The Dutch scholar Hans van Wees (1992; 1997) hasthoroughly studied the Iliad and the Odyssey in asocial perspective, primarily the relationship betweenstatus rivalry, war and social hierarchy. Van Wees hasindeed been a source of inspiration, particularly inthe sense that the epics are considered a meaningfulentity. I have, however, extended van Wees’ maintheme and added new themes and approaches espe-cially as regards material culture, gender identities,and the warrior retinue. In particular, material cul-ture cannot be ignored, forming as it does the fore-most source material in archaeology in addition tobeing a powerful silent discourse in any society, pastor present. Inspiration has also come from studies

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 477

Warfare and Gender According to Homer.

An Archaeology of an Aristocratic Warrior Culture

H E L L E V A N D K I L D E /34

by Moses Finley (1972), Ian Morris (1987), and OttoSteen Due (1999a; 1999b). It may be added that theapproach to Homer in the present study is archaeo-logical in the sense that that it focuses upon rele-vant themes in the discipline’s discourse and in thatit attempts to uncover ‘layer by layer’ levels of socialpractice in Homeric society (cf. Foucault 1985).

In the following attention is upon the Homericepics, especially the Iliad, as a structured entity, butI do think that the archaeological value of the twointerconnected stories has been widely underesti-mated. To use the Homeric epics as a supplement tothe archaeological sources has long been faut passé,although there are brave exceptions (Frankensteinand Rowlands 1978; Rowlands 1980). The rejectioncan – in the case of Northern and Central Europe –be blamed on the geographical distance but also onthe fact that the Iliad and the Odyssey are the writtenfinal products of a century-long oral epic tradition,in the same way as for example, the Beowulf-epic ofthe Early Medieval Period. In a chronological-his-torical sense, the epics do not therefore comprise anentity, as they incorporate elements and situationsfrom different eras. It can nevertheless be argued thatthe epics are relevant to the study of the EuropeanBronze Age. This is partly because the historical focalpoint of the epics is around 1200-900 BC, the so-called ‘Dark Ages’, although with distinct Mycenaeanelements (see Page 1959; Finley 1972; 1973: 29; alsothe discussion in Morris 1987: 44ff; Morris andPowell 1997), partly because the epics are a logicallyreasoned, thoroughly elaborated whole, describing aspecific society over a period of 20-30 years.

The epics may then, to a certain extent, be sourcematerial for the illiterate European Bronze Age, butthey mainly emerge as a meaningful and completewhole, describing ideal and real features of a specificaristocratic society (cf. van Wees 1992). The epicsare valuable as a relevant analogy, which can lead usto reflect on the social dimension in mute archaeo-logical material.

Homer as an analogous social context

Opinions have differed within Greek Bronze Age andearly Iron-Age archaeology, but after a long periodof rejection, Homer has again been accepted and isused as a supplementary text to archaeology (seeMorris 1987: 22ff; Morris and Powell 1997).

The epics contain antiquated features in language

and content, which directly refer to the character-istic Late Bronze Age material culture and politicalstructure of the Aegean area. Certain types ofweapons, especially boar’s tusk helmets (Fig. 1.) andthe tower or figure-eight-shaped shields, as tall as aman (The Iliad X: 261-271; IV: 404-405), for example,clearly belong to the Late Bronze Ages (Lorimer 1950:133ff, 212ff; Page 1959: 218ff; Snodgrass 1964;Bloedow 1999). The same goes for the landscape ofpower, with the well-known cities and palaces likePylos, Knossos, Tiryns, Mycenae and Orchomenos(Page 1959: 218ff; Chadwick 1976: 180ff; van Wees1992: 262; Bennet 1997).

The grouping of warriors around the most out-standing heroes, the individualising hero worship ofthe warrior company, its asymmetrical constructionand its internal rivalry belong to the Late BronzeAge and/or early Iron Age, since this form of mili-tary organisation differs distinctively from warfarein later Greek periods. In the Archaic and Classicalperiods, the military hoplite-system was a regulararmy with anonymous soldiers and a communalexpression, which is in harmony with the collectiveideology of the city-states (Runciman 1999: 732f).

However, the attitude towards death, the descrip-tion of burial rituals and the social organisation inthe epics is not really in keeping with the evidencefrom the Linear B texts and the archaeology the LateBronze Age (Dickinson 1994: 81). It is more in accor-dance with the post-Mycenaean Period’s simplerhierarchy and varying burial rituals, which shiftbetween inhumation and cremation in ceramic con-tainers (see Finley 1972: 51ff; Morris 1987: 18ff, 46,53, 178; van Wees 1992: 1ff, 262).

Despite discussions about the historical referencepoint of the individual parts of the epics, and despiteuncertainties about the exact time of writing,2 it isoften forgotten that the Homeric epics, with theirmaximum dispersion between 1700 BC and 500 BC(cf. Bennet 1997: 531), are the only writings from theEuropean Bronze Age seen as a geographic whole3.Precisely that fact makes the epics suitable to bebrought into interaction with archaeological sources,but caution obviously should increase with geograph-ical distance. However, the epics may be considered– in terms of time, place and subject – a more obviouschoice than the ethnographic observations andanalogies often used in archaeology.

The Homeric epics can therefore – on a complete-ly general level, and with the above reservations in

478 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E

mind – be regarded as an alternative way in to theilliterate Bronze Age societies north of the Alps. Farmore important, however, is the fact that the epicshave an internal logic that makes them useful forcomparative purposes. Mind you, this logical struc-ture reflects on the societies that created them. Inour source-criticism, we must recognize that theepics are an ideological construction made by andfor a male-dominated social élite. In the epics thereare social groupings whose points of view areoppressed or disregarded. Above all, the conditionsof the lower classes are out of focus, and they haveno voice. Women are only rarely the centre of atten-tion, and it can be argued that the point of view isprimarily male. This special perspective of the epicscan, at least partly, explain their more recent popu-larity; from Antiquity to the Middle Ages and upto the present, the two epics have been diligentlyused in reproductive strategies of the social élite, inthe cultivation of a violent masculine identity as awar hero, and to legitimate men's authority overwomen.

Basically, the epics, especially the Iliad, are aboutmen and war (Due 1999b); ‘the world’ according toa male warrior élite. This imbalance or distortion mayespecially cause problems of interpretation if youwant to use Homer as a source for specific historicalconditions. This report, on the other hand, viewsthe Homeric epics as an analysable context with avalue in themselves; as a closed social context witha complexity of real and ideal ingredients. An analy-sis of these various ingredients – at times full of con-trasts – can give new insight, although the narrowlyelitist, male-dominated point of view that the nar-rator holds must naturally be taken into considera-tion and kept in mind in the evaluation of the inter-pretations. Despite these reservations as to sources, Ithink that it is possible to form a fairly exact impres-sion of social practice, including class relations andideals, identities and gender dominance. In otherwords, the Homeric epics can be used as an archae-ological ‘manual’ on heroes, war and society, precise-ly because they comprise complete social contextswith many layers of meaning: something whicharchaeology does not exactly lack, but which is moredifficult, and especially more demanding, to recon-struct. This is in keeping with recent Homer research(van Wees 1992: 262; Morris 1987: 22ff, 44ff, 53,90f, 196ff with references) which agrees that theepics deliver a coherent, meaningful picture of anaristocratic society. Even the structural contrasts thatalso characterise the epics make sense when they areseen on the basis of the social contexts in whichthey are found.

The Iliad and the Odyssey can be understoodagainst the background of three different contexts.The first is the epics in themselves, i.e., the aristo-cratic society that the poet describes, and which con-stitute a frame for the actors’ thoughts, stories andactions. That is the context on which the followinganalysis is based. The second is that of the societywhich created, recreated and developed the epicsthrough verbal recital, mainly in the period betweenthe 13th and 9th century BC,4 the Late Mycenaeanand post-Mycenaean periods. The third is that ofthe society which had the epics ‘frozen’ by writingthem down, probably around 700 BC or later, i.e.the period when the Greek city-state took form.

The two epics can, with their explicit ideals regard-ing, for example, gender, status, political leadership,war, trade and gifts, be explained with reference totheir social potential in the user-societies, which are

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 479

F I G . 1 : Head of a warrior wearing a boar’s tusk helmet;lid of small ivory box (pyxis) dating to c. 1400 BC.Mycenae, chamber tomb 27 (after Borchhardt 1972).

the second and third contexts. The societies whichused the epics were aware of their historical back-ground, and they used history actively and strategi-cally. In the post-Mycenaean Period, the epics repre-sented respectable aristocratic ideals from a gloriousbut not so-distant past – perhaps in contrast to achaotic present. In the early Greek city-state, theepics offered a common identity through glorifica-tion of a heroic past, thus making them suitable tolegitimise a new type of state society, the polis(Morris 1987; van Wees 1992). The glorification of aheroic past, but with a material expression, is alsosubstantiated in Archaic times by the hero cult,which took place in front of the monumental gravesof the Bronze Age (Whitley 1995). However, theepics also legitimise asymmetry and action on otherlevels, especially men’s authority over women, andwar as a means of attaining prestige in society. Thefollowing analysis concentrates on the first of thesethree contexts, i.e., the epics as a logically structuredwhole.

Ideology and social organisation in Homeric society

The ideals of the epics do not always correspond toreality; there are both large and small deviations ina number of areas. Put simply, unrealistic elementsinspired by the ideology of society are introducedinto the story (van Wees 1992: 153). The epics arecontradictory in places, especially the way that idealsof equality are contradicted by a hierarchical reality.

Homeric social stratification as a distinctly bi-partite pyramid, with a ruling class of aristocrats atthe top, is well documented5 (Finley 1972: 61ff).Thus there are two distinct classes: the people andthe aristocracy (Iliad II: 365f), added to which wereslaves, often prisoners of war. The boundaries can-not be overstepped, since class affiliation is deter-mined by birth (Morris 1987: 94ff). The relationshipbetween the lower and upper classes is not ideolog-ically coloured, probably because the allocation ofpower between those who dominate and those whosubject themselves is undisputed. The ideology hasfree play, but only in the upper part of the pyramid.

The poet uses an inordinate amount of space indescribing the personal qualities of the individualheroes and the advantages and disadvantages oftheir activities, and in so doing indicating theirsocial position in the group of heroes. The aristo-

cratic warriors seem almost obsessed with their needfor performance. Thus they constantly compete forsocial status on- and off the battlefield; therefore thenickname ‘status warriors’ (van Wees 1992; alsoFinley 1972: 132ff). In this way, the epics create animpression of an egalitarian state amongst the aris-tocrats, in which social status and authority dependon personal qualities, strength, influence, and suc-cess in war (van Wees 1992). This focus on individ-ual performance is, however, misleading, becausefame and success have no real influence on thesocial order.

If we look beneath the surface, it is evident thatthe aristocracy itself is subordinate to a strict hierar-chical structure, where kinship, inheritance, politi-cal power and wealth are determining factors. Thearistocracy divides into a ruling élite of kings andprinces, and a non-ruling élite. Power and socialposition are inherited in certain families accordingto the principle of male primogeniture. Each aristo-crat takes his position in the social hierarchy of aris-tocrats, defined in relation to the local dynasty, andthe kings themselves are placed in a superior hier-archy in relation to the Dynasty of Pelopides ofMycenae (see below) and in relation to measurableproperty such as wealth, slaves and the size and geo-graphical position of the kingdom. Thus the aristo-crats form their own hierarchy, in which allegianceand contracts of service, for example of a militarynature between ruler and subordinates (vassals) onseveral levels, seal power relations, as in a feudalsociety (see Finley 1972: 109ff).

Personal ability is good to have, but not a require-ment, and there is a limit as to how far individualscan advance through the system purely on the basisof determination, ability and bravery on the battle-field. First-class war heroes exist both among kingsand their aristocratic companions, but this statusactually seems unimportant. Although competencein war is appreciated, it does not change the essen-tial point, which is that hierarchy is predetermined.For example, Agamemnon has a supreme hereditarystatus in the hierarchy of princes, with given privi-leges and obligations which are not dependent onpersonal capability (Finley 1972: 87), and actually,his personal accomplishments on the battlefieldare quite moderate. Besides, he is described as ‘firstamong equals’, which, all things considered, is anidealistic description, since he single-handedly andarbitrarily distributes honours and the spoils of war.

480 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E

However, Agamemnon can assume an egalitarian,paternalistic, image precisely because he is the kingof the most powerful state, namely Mycenae, with‘many isles and all of Argos’ (Iliad II: 108). It is with-out doubt a strategic choice of tone and expression.

The Iliad bears witness to the existence of a cen-tralised structure, in which the ruler of Mycenae –although to an unknown extent – exercises authorityover other political units (see Page 1959: Maps I-IIIp. 121ff). This authority is sealed through gifts andservices (Iliad II: 254f; IX: 129ff; XXIII: 296f). AndHomer does describe Agamemnon with the suffixwanax, which, in contrast to the more common wordfor king, basileus, has the significance of paramountruler – a post which is symbolised by a specialsceptre, and sanctioned by the gods (see Iliad II:100-108). Thus Agamemnon must necessarily be‘king over men’ while the other princes bear moreneutral labels. For example, Achilles is ‘the fast run-ner’, Odysseus is ‘clever’ and ‘brave’, Diomedes is‘good at war cries’ and Nestor ‘the old Gereniancharioteer’. This is a reflection of the actual powerrelations, which are clearly revealed when Achilles,for example, is thoroughly put in his place byOdysseus; ‘Though thou be valiant, and a goddessbare thee, yet he (Agamemnon) is the mightier, see-ing he is king of more’ (Iliad I: 280-81).

Ideology comes in as a manipulative elementamongst the aristocrats where, as mentioned, anideal of equality flourishes. The background for thiscontrast between an ideal of equality and an actualhierarchical structure amongst the aristocracy can ofcourse be debated, but two possibilities, which donot exclude each other, must be mentioned. Poweris never permanent and unchangeable. It may there-fore be the ruler of Mycenae who forces a ‘false con-sciousness’ on the elite in order to retain power. Onthe other hand, the aristocrats could have assumedthe ideal of equality as a part of their self-image as aclass and as a part of a strategy in which they seepower relations as partly unclear. Basically, it givesthem more freedom of action; an incentive to com-pete on and off the battlefield. The use of the prince-ly appellation ‘first amongst equals’ can therefore beread either with emphasis on the ‘first’ or on the‘equals’, depending on the person’s position in thehierarchy of aristocrats and depending on the strate-gy the individual aristocratic warrior adopts.

Material culture and society in Homer

In Homer, material culture reflects to a greater degreethe social hierarchy than the ideology of equality.Palaces, castles, spectacular gifts and drinking equip-ment, magnificent weapons and stately burial ritualsare reserved for the aristocracy, and luxurious pres-entation of material goods increases concurrentlywith the position in the hierarchy of society. Asmentioned, the hierarchy also saturates the upperclasses of aristocrats, and also here the materialculture follows along. In the so-called catalogue ofships ‘the well built citadel of Mycenae’ provides byfar the strongest force, and can present the best andwealthiest war material:

... of these was the son of Atreus, lord Agamemnon, captain of

an hundred ships. With him followed most warriors by far and

goodliest; and among them he himself did on his gleaming

bronze, a king all-glorious, and was pre-eminent among all the

warriors, for that he was noblest, and led warriors far the most

in number. (Iliad II: 575ff: also XI: 15ff)

It is a huge demonstration of power and social status.It is also a clear demonstration of violent potential –not only to the Trojan enemy but to a great degreealso to the allied princes of the Achaean army. Inexactly the same style, Agamemnon offers Achillesgreat fortunes and privileges to forget his anger andreturn to the ranks of the fighters (Iliad IX: 120ff).No other king could afford to be that generous.

Burial rituals and personal equipment follow thehierarchy to a large extent, whereby the ruling élitepresents itself in the best equipment and receivesthe stateliest funerals. For example, in the Odyssey(XXIV: 32) we are told that the whole Achaean armywould have co-operated in the construction of agrave mound for Agamemnon, which forms a con-trast to the more moderate funerals of common aris-tocrats in the epics. It is, however, important tonotice that the great hero Patrocles receives a funer-al worthy of a king (Iliad XIII). But Patrocles is not aking, but a common aristocrat, and besides fosterbrother to the king of the Myrmidons, Achilles.Through a stately funeral, ending with the construc-tion of a monumental mound, and followed bygrandiose burial games in Patrocles’ honour, a farhigher social status is reflected than his position inthe social hierarchy and his fame as a war hero canjustify. The ideology of equality and free competi-tion is expressed here when the material world –

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 481

especially weaponry and burial rituals – supports theidea of personal achievement and fame as a source ofpower and influence. Weapons and burial rituals areactively used in the constant status rivalry amongstthe heroes; but the reality is that both high and lowsocial positions are controlled by other, less easilymanipulated mechanisms than the ability to wagewar. Neither Patrocles’ heroic deeds on the battlefieldor the, to say the least, conspicuous burial perform-ance changes his social position in the hierarchy;roughly speaking, society is ideologically reproduced.

But there is more to it: when Achilles arranges astate burial for Patrocles, he also questions the exist-ing power relations. This material display may wellbe in accordance with the ideology or, if you like,with the latitude for social rivalry allowed by thesocial system. But the whole séance has a more pro-found meaning, which can be readily understood byeveryone in Homeric society: even power is nego-tiable; power is never unchangeable! Social identi-ties, existing – or, as here, under construction – arecommunicated through material culture. Materialculture has obviously tangible practical and socialfunctions as well as more abstract symbolic meaningsattached to the social organisation, ideology andhistory of society (Vandkilde 2000: 21ff).

Certain material things can have legends and sto-ries attached. This is illustrated by the story aboutthe boar’s tusk helmet (Fig. 1), which Odysseus putson before he and Diomedes leave for a nightly spyingexpedition:

And Meriones gave to Odysseus a bow and a quiver and a

sword, and about his head he set a helm wrought of hide, and

with many a tight-stretched thong was it made stiff within,

while on the outside the white teeth of a boar of gleaming

tusks were set thick, to and fro, well and cunningly, and on

the inside was fixed with a lining of felt. This helmet

Autolycos on a time stole out of Eleon when he had broken

into the stout-built house of Amyntor, son of Ormenus; and

he gave it to Amphidamas of Cythera to take to Scadeia, and

Amphidamas gave it to Molos as a guest-gift, but he gave it to

his own son Meriones to wear; and now, being set thereon, it

covered the head of Odysseus. (Iliad X: 260-71)

It is truly a helmet with soul and personality thatOdysseus puts on his head. The expedition into theenemy camp means that a new story can be addedto the helmet's cultural identity, which is thereforeconstantly changing. The story of the helmet shows

how things can be bearers of history and memory,which are thus transferred in time and space. Thehelmet and its symbolic goods become a part ofOdysseus’ personality and social identity as a warhero in that situation.

The Homeric world is a highly hierarchical society,which becomes a natural state through materialmeans. As a whole, the material culture follows thesteps of the hierarchy but reflects to a certain degreethe ideology of the upper classes. The war heroes andother people in the poems consciously or uncon-sciously use material culture in strategies and actionswhich maintain and create social identity. In addi-tion, we can see how the material culture so to speakinfluences the actors recursively. Material visibility,not least bodily appearance, is effective in itself,although within already designated limits.

War and aristocratic warriors in Homeric Society

In the epics, war and violence are closely connectedto status rivalry (van Wees 1992). Moses Finley(1972: 131) expresses it this way: ‘Warrior and heroare synonyms, and the main theme of a warriorculture is constructed on two notes – prowess andhonour. The one is the hero’s essential attribute, theother his essential aim.’ War is officially waged todefend insulted honour, to gain the respect of friendsand enemies, and to achieve fame. But, really, war isinstead waged in order to confirm power and as ameans of enrichment and expansion of territory.Wealth is a goal, which ideally is achieved throughgift-giving, trade and exchange, but actually moreoften reached through war and raiding expeditions(van Wees 1992: 101).

The significance of the status rivalry expressed induels between the heroes on the battlefield is nodoubt highly exaggerated in the poems, again as aconsequence of ideological distortion. The Homericsociety is a warrior culture, in which war and violenceare important structuring elements. It is the fineheroic duels that attract attention, because throughthem the warrior ideal can be reproduced almostinfinitely, and the ugly face of war, which is also apart of it all, tends to be hidden. Attacks, piracy, andpillaging are clearly a very substantial part of thewar actions, and at the same time an economicnecessity both before and after Troy. For example,Odysseus reports on a predatory attack in this way:

482 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E

From Ilium the wind bore me and brought me to the Cicones,

to Ismarus. There I sacked the city and slew the men; and

from the city we took their wives and much treasure, and

divided it among us, that so far as lay in me no man might go

defrauded of an equal share. (Odyssey IX: 39-42)

Homer gives the classic institution of war heroes aprominent place in society; in war and peace. A war-rior band can be defined as a more or less exclusiveclub of specialised warriors. Ethno-historically, theinstitutionalised warrior band divides itself into threecategories, with different recruiting, leadership andinternal structure (Vandkilde chapter 26): first, war-rior institutions in which access is regulated throughage (age grade), second, warrior institutions in whichaccess is regulated through personal qualities (inde-pendent companionship), and third, warrior insti-tutions in which access is regulated through dis-tinctions of rank (dependent companionship). TheHomeric warrior institution belongs among the lasttwo categories, mostly the last category (cf. vanWees 1997: 670). It is a company of warriors, an eliteteam of aristocratic warriors who accompany a warleader of high descent. Such a band of warriors ismentioned in several places but most comprehen-sively in the catalogue of ships (Iliad II: 494ff). Thusthe warriors of Myrmidon accompany Achilles, withhis foster brother Patrocles as second in command.Nestor's following of warriors is probably the samearistocrats who, at home in the palace in Pylos, sitin the place of honour at the high table duringTelemachos’ visit (Odyssey III: 469-574). The follow-ing of warriors surrounding Odysseus also accompa-nies him on his way home from Troy to Ithaca. TheCretan warriors are led by their king, Idomeneus, etc.

Not surprisingly, here too, the ideal differs fromreality. Personal qualities seem definitive for therecruiting of the company of warriors, for internalstatus differentiation, and for such an importantissue as leadership; in particular, martial ability mustconstantly be proven on the battlefield. Nevertheless,wealth, birth and political position are the mostimportant criteria for the composition of the groupof warriors. Men of the people are apparentlyexcluded from the company. Each king is the bornleader of a permanent, dependent following of aris-tocratic warriors, and in that context, honour,respect, achievements and fame are less important.Furthermore, the size of the company of warriorsdepends on the position of its leader in the superior

political hierarchy; thus Agamemnon’s following isby far the largest. In addition there is a superiorcompany: Agamemnon has surrounding him –besides a company of noble warriors from his ownkingdom –a sworn guard of princely warriors, name-ly the other Achaean kings.

Actually, this structure calls to mind theGermanic retinue (Gefolgschaft, hird) in the 5thcentury AD. In the first centuries AD, the militaryalliance of warriors is gradually developed by theGermanic tribes from a loosely knit, independentband of warriors, built around mutual respect, pres-tige, and martial abilities to a dependent, hierarchicsystem of aristocratic warriors who are bound byoath to a powerful royal family, i.e. a system ofretainers (cf. Steuer 1982: 55ff; Hedeager 1990: 184ff;Jørgensen 1999: 156ff). First and foremost, however,the Homeric military institutions of aristocrats makeus think of the Late Bronze Age military system inthe Aegean area as it can be roughly reconstructedfrom the Linear B texts. We are now a few centuriesearlier than the focal point of Homer’s epics, butthe connection seems evident despite interpretativedifficulties.

The clay tablets from the Pylos palace fromaround 1200 BC contain information about a seriesof offices in the Pylian state administration (Page1959: 183ff; Chadwick 1976: 71ff; Bennet 1997):Wanax is thus the highest and most lucrative post,probably the king himself. Besides the wanax, thereis another important post, the lawagetas, which couldbe intended for the heir to the throne, or maybe theking himself in another role. The actual word means‘leader of the people’ but as ‘the people’ in Homeroften refers to the warriors, the best translation isperhaps army leader or ‘leader of the warriors’. Inaddition, there is a third category, the so-called heque-tai which, directly translated, means companions.Here we are probably being introduced to the com-pany of warriors who in later interpretations are theking’s drinking companions and close attendants inwar and peace. The hequetai of the tablets are oftennamed with their father’s name as well as their own,and this careful use of the patronymic indicates anespecially high social position. The clay tablets fromKnossos from around 1400 BC (Page 1959; Chadwick1976; Bennet 1997, op. cit.) tell us that hequetai hadthe right to keep slaves, wore distinctive garmentsand drove special chariots, which, of course, sup-ports their interpretation as warrior aristocrats with

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 483

a close connection to the king or his deputy com-mander.

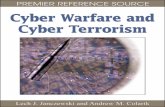

The walls in the secondary megaron in the south-west wing of the Pylos palace were decorated withwarrior scenes, both battles between infantrymen andprocessions with warriors and chariots (Fig. 2). Whilethe primary megaron was most likely the king’sreception hall, with the warrior scenes in mind, it isnatural to assume that the secondary megaron wasthe seat of the commander, lawagetas (Davis andBennett 1999: 117f), and his attendants, the hequetai.

Male institutions of warriors exist in many con-temporary and historical societies where they can bemore or less bounded and more or less exclusive intheir recruitment. An interesting aspect is the built-in contrast on two levels in these warrior institu-tions: first of all, it is an exclusive club, which almostby definition excludes women and children, but inmany cases also men of non-aristocratic descent.Although the military club thus comprises a poten-tially oppressive extension of power, there are oftenwell-defined obligations based on the well being ofsociety; including religious, political and defensivefunctions. Second, war is a more or less importantpart of the activities of the association. A martialappearance, in which a masculine expression isintensified through spectacular weaponry, often mis-represents, to some degree, a life which also includespeace. The Homeric military institution of warriorsalso has such contrasting features. In Homer, the mil-

itary institution occupies above all, a male domain,which is in sharp contrast to a female domain basedon a stereotyped feminine ideal.

Odysseus and Penelope: gender in Homer

In Homer’s society, women have no access to thecompany of warriors and regardless of their positionin the social hierarchy, men and women live in sep-arate worlds. Men’s actions and feelings are moreclosely connected to those of other men than tothose of women, whether their wives or other womenin or outside the household (Finley 1972: 148).

Within the aristocracy there are two genderideals, a masculine and a feminine. These genderideals are represented in Homer by King Odysseusand his wife Queen Penelope, who both live up tothe ideal in an exemplary manner in everythingthat they do. Whereas Odysseus is the cosmopolitanwarrior who fights his own and others’ battles,Penelope stays at home and guards the family andits properties. Significantly, the Homeric word kre-demnon means both city wall and the marriage veilof a woman (Morris 1987: 192). In a way, Penelopeis a heroine, defined on the basis of specific femalevalues and certain moral codes. The division oflabour between the two main characters is explainedin the Odyssey, where Penelope relates a conversa-tion with her husband shortly before his departureto Troy. Odysseus says:

484 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E

F I G . 2 : Restored wall paintings with warrior processions and fighting scenes in the second megaron (Hall 64) of thepalace of Pylos in Messenia. It was destroyed around 1200 BC. The megaron may well have been the seat of lawagetas,the leader of the warriors and the hequetai, the following of warriors – as discernible in the Linear B texts (afterBorchhardt 1972).

Therefore I do not know whether the god will bring me back,

or whether I shall be cut off there in the land of Troy: so let

all here be your care. Be mindful of my father and my mother

in the halls even as you are now, or yet more, while I am far

away. (Odyssey XVIII: 265-68)

The Homeric epics are more or less one long idolisa-tion of the heroic man. Not many verses are dedi-cated to the lives and world of women, which, how-ever, are clearly present as a necessary contrast.While the warrior hero is the ideal for male aristo-crats, the female aristocrat finds her ideal in a nar-row gender identity as a peaceful, caring person wholooks after the home during the frequent absencesof her husband. Early European written sources thusdocument the presence of what you could call sym-metric gender ideals, in which a violent, extroverted,masculine cosmopolitan is contrasted with a peace-ful feminine counterpart in the domestic sphere.This ideal is surprisingly similar to certain genderstereotypes in our own world, and it is kept alive inthe same way by separate gender domains, wherewomen and men to a great extent do what cultureexpects.

In Homeric society, the war hero cannot existwithout his female counterpart, who gets her iden-tity from oikos, the Homeric word for the domesticdomain. The war hero even rejects any connectionto oikos, which stands for peace, and therefore life.In a way, the war hero denies life, achieving hisidentity through violence and death. However, heexists qua his opposite – the peaceful, home-fixatedwoman. Thus men and women ideally each ruletheir world:6

Masculine FeminineInternational domain Private domain – oikosAdventure StabilityWar PeaceChange ReproductionDeath LifeLion7 Human being

In Homeric society, too, gender ideals are kept aliveby social practice in that area, at the same time asthey help to maintain a certain image of society.And as a rule, concepts of gender are very close tothe reality of the actors. The gender ideal – Odysseus-Penelope – has its roots deep in the real world, inwhich women typically are from Venus and men

from Mars, to use a modern expression. The Trojanwomen stay inside the palace or stoically watchtheir men on the battlefield from towers and wallsof the citadel8 (e.g., Iliad III). Neither do the wives,women servants and female slaves of the Achaeanheroes move outside oikos, by which is meant thepalace at home and the camp by the beach. Womenservants and female slaves are typically booty ofwar, captured during raiding expeditions during theperiod leading up to the siege of Troy. The ideals androles of the aristocracy spread downwards in society,in that ordinary women typically work as servantsin the palaces, while men’s jobs are out in the coun-tryside, even though not primarily in battle. Thereis, however, a clear division of labour according togender, originating in and interacting with the con-trasting male and female ideals. The image of twogender domains is supported by material culture,which in the epics gives a ‘true’ picture, with mag-nificent weapons for men and more peaceful thingsfor women.

The female role is the most constant, but thereare interesting deviations which far from fit theideal: dangerous women with special abilities and adisturbing power over men, such as Helena, Calypso,Circe and Cassandra. There are also goddesses whocan join in the turmoil of the battle, apparently with-out surprising anyone; especially the virgin warriorsPallas Athena and Artemis, but also the more femi-nine of the species, like Aphrodite, Iris, and Hera.The world of the gods is definitely not a simplereflection of the world of humans.

Amongst the men, there are several examples ofwarriors who cannot quite live up to the ideal of awar hero, and they are exposed to public ridicule.Magnificent, terrifying weapons cannot change thefact that the beautiful Prince Paris is not made forthe horrors of war and the role of hero. Helen mockshim and incites him to fight (Iliad III: 42), since herhonour, too, is at stake. The woman in the role as theone who is ultimately responsible for the honour ofthe family and therefore must incite to revenge andwar (without participating herself) is found in manytribal societies, such as Polynesian chiefdoms,Arabic Bedouin tribes, Scottish Highland clans andvillage communities in the Balkans and in Greece.The province of Mani at the southernmost point ofPeloponnese is, like Crete, known for its warriorculture, vendettas, and endemic war on a family-and clan level. Women’s attitude towards war and

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 485

violence in Mani can be expressed thus: ‘If I were aman, you would see bloody revenge!’ (Ambatsis andAmbatsis 2000: 21, my translation from Swedish).Women in Homer and in these tribal societies there-fore not only aid in creating and recreating war andviolence as legitimate means to achieve certain goals,but also certain standards concerning what womenand men can do.

Separate gender domains – as they exist in manycultures – in themselves tell us nothing about rela-tions of dominance, namely because their exactcontent and the relationship between them are cul-turally specific. In Homer, however, there is notonly a gender asymmetry in the sense that the maledomain takes up a disproportionately large amountof space in the story, but also in the sense that menhave distinct authority over women. Women in theAchaean camp have no say at all; they are objectswho can be moved around and given away in thesame way as material things (e.g., Iliad I: 183f, 345ff;IX: 128f). After marriage the aristocratic womenhave acquired a certain authority – if nowhere else,then within their own household. In the royal house-hold of the Phaiakians (Odyssey VIII) Queen Areteclearly has a certain influence, but it is King Alcinouswho has the final word (see Finley 1972: 103).

Unmarried women of high descent are, however,completely reified, as they fill the role of servicesand gifts for the sealing of alliances. With no moreado, Agamemnon offers the difficult, sulky Achillesimportant members of his household, who are obvi-ously his private property:

Three daughters I have in my well-built hall Chysóthemis,

Laodíke, and Ifiánassa. Of these let him lead to the house of

Peleus which one he will, without gifts of wooing, and I will

furthermore give a dower full rich, such as no man ever yet

gave with his daughter. (Iliad IX: 144-48)

But another facet of the Homeric dominance pat-tern in the area of gender is of course that womenthemselves contribute to a great degree to the sys-tem by doing exactly what culture expects.

Homeric society

In the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, thenarrator gives the audience an insight into a martialculture, which is described from the social élite’spoint of view. After that, the story is primarily about

men and war. Access to the resources of society ishierarchical, and family, inheritance, power, andwealth structure the social hierarchy.

The ideology of society introduces certain unreal-istic elements, especially in how an ideology ofequality reigns amongst the aristocracy. We are giventhe impression that personal qualities, especially mar-tial ability, give access to social position and power,but for much of the time, the hierarchy amongst thearistocracy is a foregone conclusion. The ideology ofequality is probably one of denial, which is cleverlymanipulated by the high king, but at the same timeit is a part of the aristocratic lifestyle and self-imageamongst ‘equals’, because it gives a certain freedomof action and can be used to question power. It iswith this background in mind that the constantstatus-rivalry between the heroes should be under-stood.

In principle, material culture supports the hierar-chy by directly reflecting it, but is also used in socialstrategies which attempt to shift the balance ofpower. Certain things have special stories and mem-ories of the past attached, and these symbolic qual-ities reflect on the user and become a part of his per-sonality. Things and personal belongings create andrecreate different types of social identity, althoughwithin fixed limits.

The Homeric society can best be summarised asan aristocratic warrior culture in which war is animportant part of social reproduction, both on anideological and a socio-economic level. War isdescribed with strong ideological undertones, andreality is misrepresented, in that status-charged duelsare given excessive space and attention. A stereo-typical warrior ideal, which again confirms a certaintype of male identity, is thus reproduced, while theless flattering side – namely looting, piracy and pil-laging of foreign settlements – is an ideologically sup-pressed, but economically necessary, part of society.

The classic male institution of warriors is animportant part of society’s social organisation, actingon two political levels: partly as a company of fol-lowers for individual princes, partly as a superiorfollowing of princes for the paramount king. Thewhole system of followers is strongly asymmetric inits structure. It is implicit in the nature of the systemthat it excludes women, children, and certain groupsof men, and that it misrepresents a reality which isalso peaceful. This is because there are also peacefulmoments at home and away, and because the warrior

486 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E

groups also take part in peaceful activities, such asthose of a religious or sporting nature. However, wartakes up a lot of space in Homeric society, anddoubtless contributes to society’s being held fast inmonotonous and very limited ideas of, and stan-dards for, what men and women can do.

Thus two contrasting gender ideals face eachother, based on separate, but existentially dependantgender domains. The male aristocrat is portrayed asa martial adventurer and cosmopolitan, while thefemale aristocrat is described as peaceful and domes-tic in everything she does. There is, however, a clearasymmetry, as men exercise authority over women;actually, women are reified. There is a great degree ofaccordance between ideals and reality in the genderarea, indicating that power in this case is not con-tested. To a very large extent, Homer’s men andwomen act – like ourselves – in accordance with thestereotypes of culture, also in fields where, strictlyspeaking, they need not. Thus society and its cul-turally determined ideas of gender roles are appar-ently reproduced with no opposition, and theserepetitive patterns are legitimated through differenttypes of cultural consumption, including personalappearance and material culture.

From Homer to archaeology

Homer’s epics demonstrate a significant point forarchaeology, namely that ‘things’, especially equip-ment for war, can have extraordinary value becauseof the tales they have attracted during their lifecycle. By utilising such a memorable object, the actoris enriched by the attached history, simultaneouslyensuring a continuation of the tales. It is reassuringto see that in this particular elitist setting materialculture really makes culture material, not only byreproducing the hierarchical social order, but also –though to a more limited extent – by being utilisedin strategies that question the same order. Throughtheir visibility material things are in themselvespowerful by influencing in turn the actions andthoughts of human actors. However, archaeology cangain further assistance from Homer’s epics.

Considered as a narrative – note the parallel tothe Homeric epics – the burial finds of the illiterateBronze Age societies in temperate Europe, almostregardless of time and place, mainly tell of the socialélite. It is difficult to separate ideal from reality inthe archaeological burial material, and often it is

not possible to do so from the graves alone, whichmust be seen as presentations of gender, war andsociety. Certain aspects can possibly be misrepre-sented consciously or unconsciously, actually in thesame way and for the same reasons as they were byHomer. War can be more than status rivalry, andpeace can also be a part of the image. Likewise, genderideals can seem clearer than everyday gender identi-ties, and monumental graves can be an attempt tolegitimise hierarchies which are not generallyaccepted. It is, of course, best to include other archae-ological sources into a ‘complete’ context, whereverthis is possible. To examine structures of durationand change over a long period of time is also a wayof evaluating ideals compared to realities in the illit-erate past.

Warfare, male companionship, overt materialand immaterial rivalry, and opposing gender idealsand identities are perhaps universal components ofelitist culture, whereas the constitution of powerbetween coercion and persuasion and betweencooperation and resistance varies from case to case.The archaeologically most interesting thing aboutHomeric society is the way its various constituentsare wholly integrated: how it is virtually impossibleto understand one element of social practice with-out considering other elements, and how socialorganisation and ideology exhibit various levels ofagreement and disagreement depending on theextent to which power is questioned, i.e. whether ornot power is in need of being legitimised. It is, forinstance, easy from a superficial reading of the textto assume that society is based on the outcome ofovert status rivalry rather than on other less manip-ulative mechanisms, or that warfare is predominant-ly enacted as honourable sporting duals betweenaristocratic champions. Only a more in-depth analy-sis reveals that violent and cruel acts of warfare areequally important constituents of society.

My main point is here that superficial interpreta-tions of for instance Bronze Age burials would leadto similar mistakes.

Concluding reflections on ideology and action

Ideology has played a key role in much recentarchaeology and furthermore intersects inevitablywith the issue of warfare and warriors. The concept ofideology is therefore discussed briefly as a concluding

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 487

remark to the issue of Homer and archaeology andparticularly in relation to the interplay of socialaction and structure highlighted by modern sociol-ogy. A central problem is most clearly revealed whenlooking at the constitution of Homeric society.Roughly analogous to the situation in the earliestScandinavian Bronze Age Homer’s epics portray asociety in which significant social fields related tokingship, politics and alliance, subsistence andexchange, and indeed warfare, are affected by a dis-cord between what might be termed an egalitarianideology and an institutionalised hierarchy. The egal-itarian ideology could, alternatively, be regarded asa structural residual from a previous social order, stillbeing active in certain situations of power enact-ment and therefore part of the social system as such.

The disharmony in Homer’s epics between, onthe one hand, actions and discourses of an egalitar-ian nature and, on the other hand, actions and dis-courses in tight accordance with a fairly rigid socialhierarchy bring forth the difficult discussion of theposition of ideology in society. Homer, in other words,highlights the impossible choice between ideologyand reality. The general relationship between burialand society has evoked much discussion in morerecent archaeology due to the high proportion in thisdiscipline of sources to ritual practices, even result-ing in a major research field labelled ‘archaeology ofdeath’ (see Tarlow 1999, 1ff for a recent survey). Thepositions have tended to follow paradigmatic shifts.

Much post-processual archaeology has notablyhad a strong idealist tone in that ideology is believedto direct the social world, as opposed to a generallyearlier materialist attitude that ideology and religionmerely reflect the current mode of production. Thequestion has been whether the burial record reflectssocial structure or ideology, but it is not unusual tofind expressions that mix these two terms such as‘ideological reproduction of social structure’ (e.g.,Sørensen 2000: 85). The implies that we are suppos-edly not dealing with real social structure, but withideology, or an ideologically distorted version ofsocial structure – even cases of ‘false consciousness’.It also illustrates the ambiguity of the whole matter.In Bourdieu’s work a similar division is re-found inwhat he calls a double reality between what peoplesay and what they actually do – a recurring theme inhis studies of the Algerian Kabyle (e.g. Bourdieu1998: 92ff). The entire discussion about the ‘doubletruth’ as one between saying and doing – between

discourse and action – is definitely difficult to trans-fer directly to archaeology, not least because of thematerial and fragmentary nature of the sources.Bourdieu, in contrast to Giddens, emphasises theideological component of social structure probablybecause of his schooling in ethnographic fieldwork.

The structurationist approach possibly offers akey to the solution of this problem, namely its basicassumption of a double existence of structure andagency. Ideology, says Giddens, cannot be concep-tualised independently of action, structure and dis-course, and refers only to circumstances of asymme-tries in the systems of domination, notably whensectional interests are being signified and legit-imised (Giddens 1984: 33). Structuration theory isweakly developed at this point, but it may followthat action can be more or less loaded with ideolog-ical thinking. It may prove useful, and this makessense also in the Homeric context presented above,to distinguish roughly between two types of action:a habitual, culture-bound, and almost objectivekind of action, which is accepted and carried out as‘the way things should be done’ without question-ing as opposed to a strategic, political and ideologi-cal kind of action, which is constantly negotiatedand which continuously questions the social condi-tions of action9. Both kinds of action are of coursesignified, for example through material culture, buttheir meaning is different.

Some funerary activities in prehistory obviouslypossess an ideological tone rooted in strategic think-ing, whereas other funerary activities appear muchmore habitual and culture-bound, and this is alsovalid for activities in other domains; ritual, domesticor otherwise. Strategic, political and ideologically-influenced action and interaction seem especiallyfrequent during shifts in systems of domination –thus agreeing with Giddens’ second dictum aboutthe nature of ideology. Both types of action are,however, socially embedded in that that they aresimultaneously preconditioned by, and produce,social structure. Homer highlights this point, whichin the study of the longue durées and conjuncturesof prehistory gains a long-term perspective. What wecan see in European prehistory is, in fact, time-spacepatterns of human action – more often continuousand reproductive than changeable and strategic, butno matter how much or little motivated all thesepractices involve past, present and future socialstructures.

488 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E

Acknowledgement

An early draft of this paper was translated intoEnglish by Patricia Lunddal, Faculty of Arts atAarhus University.

N O T E S

1 For quotes I have used A.T. Murray’s translations of the

Odyssey (revised edition 1995) and the Iliad (1946). I

have, however, consulted Otto Steen Due’s new transla-

tion of the Iliad into Danish (1999a; 1999b), and I have

assessed the Greek text myself. Murray’s translation of the

Homeric laoì has been changed from ‘people’ to ‘warriors’,

since Homer uses laós-laoì with this meaning, synony-

mous with the aristocratic upper class of society. Likewise

in the passage with the boar’s tusk helmet, I have made

small corrections to Murray’s original translation. This is

in keeping with Due’s new translations as well as Wilster’s

(1979a; 1979b) old translations of the poems into Danish.

2 The historical position of Homeric society is much debated.

My view is close to Moses Finley’s, namely that Homeric

society has its basis in 10th-9th century Greece after the

fall of the complex Mycenaean state societies but prior to

the formation of the early Greek polis in the 8th century

BC. This is an intermediate phase, which seems to have

features in common with the chiefdom type of society

described in ethnography and social anthropology. The

poems were probably written down late in the 8th century

BC, in connection with or after the invention of the

alphabet (Morris 1987: 23f). However, 6th century BC

Athens of the age of Peisistratos is also a possibility (see

Finley 1972: 44ff).

3 Except the Linear A and B tablets, which are administra-

tive lists of a redistributive political economy. The tablets

completely lack the overriding character of the epics.

4 Some elements can, however, only be explained by assum-

ing that the epics must preserve a memory of much earli-

er occurrences. The tower-shaped shields for instance go

out of date after the Shaft Grave Period. Perhaps a contin-

uous oral epic tradition existed, even dating back to early

Mycenaean times of the 17th and 16th centuries BC.

5 Kurt Raaflaub (1997) has recently argued for the preva-

lence of a more egalitarian structure in the society of the

poems. This is in contrast to Moses Finley’s more elitist

view, which is more in line with my own readings of the

epics, especially the Iliad.

6 Michael Shanks (1993: 97) finds similar binary opposi-

tions on a proto-Corinthian perfume bottle.

7 The lion is often used as a synonym of the war hero; e.g.,

Hector is a lion (Bloedow 1999).

8 Later Classical vase paintings show an advanced situation

in which the citadel of Troy is being attacked: here the

women no longer act passively, but defend themselves

with kitchen implements (Lise Hannestad, personal com-

munication). It also shows that function is dependent on

context, and is a very mobile quality in material things.

9 I have discussed this classification of action with Torsten

B I B L I O G R A P H Y

• Ambatsis, I. and Ambatsis, J. 2000. ‘Vore jag karl skulle du

få se på hämnd! Om blodshämnd och fostbrödralag i

Grekland’. Medusa, 3, pp. 19-28.

• Bennet, J. 1997. ‘Homer and the Bronze Age’. In: I. Morris

and B. Powell (eds.): A New Companion to Homer. Leiden,

New York and Köln: Brill. pp. 511-33.

• Bloedow, E.F. 1999. ‘“Hector is a lion”: New light on war-

fare in the Aegean Bronze Age from the Homeric Simele’.

In: R. Laffineur (ed.): Polemos. Le ontexte guerrier en Égée à

l'age du Bronze. Actes de la 7e Rencontres egéenne interna-

tionale Université de Liège, 14-17 avril 1998. Université de

Liège. Université de Liège, Liège and University of Texas,

Austin, pp. 285-293.

• Borchhardt, J. 1972. Homerische Helme. Helmformen der

Ägäis in ihren Beziehungen zu orientalischen und europäischen

Helmen in der Bronze- und frühen Eisenzeit. Mainz am Rhein:

Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

• Bourdieu, P. 1998 (1994). Practical Reason. On the Theory of

Action. Cambridge: Polity Press.

• Chadwick, J. 1976. The Mycenaean World. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

• Davis, J.L. and Bennet, J. 1999. ‘Making Mycenaeans: war-

fare, territorial expansion, and representations of the

Other in the Pylian Kingdom’. In: R. Laffineur (ed.):

Polemos. Le contexte guerrier en Égée à l'age du bronze. Actes

de la 7e Rencontres egéenne internationale Université de Liège,

14-17 avril 1998. Université de Liège. Université de Liège,

Liège and University of Texas, Austin, pp. 105-118.

• Dickinson, O. 1994. The Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

• Due, O.S. 1999a. Homers Iliade på dansk. Copenhagen:

Gyldendal.

• Due, O.S. 1999b. ‘Iliaden - krig og digt’. Sfinx, 22(3),

pp. 129-33.

• Ehrenreich, B. 1997. Blood Rites. Origins and History of the

Passions of War. New York: Metropolitan Books.

W A R F A R E A N D G E N D E R A C C O R D I N G T O H O M E R . 489

• Finley, M.I. 1972. The World of Odysseus. London: Pelican.

• Finley, M.I. 1973. The Ancient Economy. London: Chatto

and Windus.

• Foucault, M. 1985. The Archaeology of Knowledge. London:

Tavistock Publications.

• Frankenstein, S. and Rowlands, M. 1978. ‘The internal

structure and regional context of Early Iron Age Society in

South-West Germany’. Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology,

London, 15, pp 73-112.

• Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the

Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

• Hedeager, L. 1990. Danmarks Jernalder. Mellem Stamme og

Stat. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

• Jørgensen, A.N. 1999. Waffen und Gräber. Typologische und

chronologische Studien zu skandinavischen Waffengräbern

520/530 bis 900 n.Chr. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige

Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

• Lorimer, H.L. 1950. Homer and the Monuments. London:

Macmillan & Co. LTD.

• Mallory, J. 1989. In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Language,

Archaeology and Myth. London: Thames and Hodson.

• Morris, I. 1987. Burial and Ancient Society. The Rise of the

Greek City-state. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

• Morris, I. and Powell, B. (eds.) 1997. A New Companion to

Homer. Leiden, New York and Köln: Brill.

• Murray, A.T. 1946. The Iliad. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard

University Press.

• Murray, A.T. 1995. The Odyssey. Revised edition. Cambridge

(Mass.): Harvard University Press.

• Page, D.L. 1959. History and the Homeric Iliad. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

• Raaflaub, K.A. 1997. ‘Homeric society’. In: I. Morris and

B. Powell (eds.): A New Companion to Homer. Leiden, New

York and Köln: Brill. pp. 624-48.

• Ravn, M. 1993. ‘Analogy in Danish Prehistoric studies’.

Norwegian Archaeological Review, 26(2), pp. 59-90.

• Rowlands, M. 1980. ‘Kinship, alliance and exchange in

the European Bronze Age’. In: J. Barrett and R.J. Bradley

(eds.): Settlement and Society in the British Later Bronze Age.

(British Archaeological Reports, 83). Oxford: British

Archaeological Reports, pp. 15-55.

• Runciman, W.G. 1999. ‘Greek Hoplites, warrior culture,

and indirect bias’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute (N.S.), 4, pp. 731-51.

• Shanks, M. 1993. ‘Style and the design of a perfume jar

from an Archaic Greek city state’. Journal of European

Archaeology, 1(1), pp. 77-106.

• Snodgrass, A.M. 1964. Early Greek Armour and Weapons.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

• Steuer, H. 1982. Frühgeschichtlichen Sozialstrukturen in

Mitteleuropa. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

• Sørensen, M.L.S. 2000. Gender Archaeology. Cambridge:

Polity Press.

• Tarlow, S. 1999. Bereavement and Commemoration. An

Archaeology of Mortality. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell

Publishers Ltd.

• Vandkilde, H. 2000. ‘Material culture and Scandinavian

archaeology: A review of the concepts of form, function,

and context’. In: D. Olausson and H. Vandkilde (eds.):

Form, Function and Context. Material culture studies in

Scandinavian archaeology. (Acta Archaeologica Lundensia.

Series in 8.o. 31). Lund: Almqvist and Wiksell

International, pp. 3-49.

• Vandkilde, H. 2003. ‘Commemorative tales: archaeological

responses to modern myth, politics, and war’. World

Archaeology, 35(1). pp. 126-44.

• Vandkilde, H. and Bertelsen K.B. 2000. ‘Krig og samfund

i et arkæologisk og socialantropologisk perspektiv’. In:

O. Høiris, H.J. Madsen, T. Madsen and J. Vellev (eds.):

Menneskelivets Mangfoldighed. Arkæologisk og Antropologisk

Forskning på Moesgård. Moesgårds Jubilæumsskrift. Aarhus:

Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter. pp.115-26.

• Wees, H. van 1992. Statuswarriors. Warfare in Homer and

History. Amsterdam: J.C. Greben Publishers.

• Wees, H. van 1997. ‘Homeric Warfare’. In: I. Morris and

B. Powel (eds.): A New Companion to Homer. Leiden, New

York and Köln: Brill, pp.668-93.

• Whitley, J. 1995. ‘Tomb cult and hero cult. The uses of

the past in Archaic Greece’. I: N. Spencer (ed.): Time,

Tradition and Society in Greek Archaeology. Bridging the

‘Great Divide’. London and New York: Routledge.

• Wilster, C. 1979a (1836). Homers Iliade (oversat til dansk).

Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanums Forlag.

• Wilster, C. 1979b (1837). Homers Odyssee (oversat til

dansk). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanums Forlag.

• Wylie, A. 1985. ‘The reaction against analogy’. Advances

of Archaeological Method and Theory, 8, pp. 63-111.

490 . W A R F A R E , W E A P O N E R Y A N D M A T E R I A L C U L T U R E