Visitors' perceptions of the use of cable cars and lifts in Wulingyuan

Transcript of Visitors' perceptions of the use of cable cars and lifts in Wulingyuan

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by:On: 21 September 2009Access details: Access Details: Free AccessPublisher RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Sustainable TourismPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t794297833

Visitors' perceptions of the use of cable cars and lifts in Wulingyuan WorldHeritage Site, ChinaC. Z. Zhang a; H. G. Xu a; B. T. Su b; C. Ryan c

a Centre of Tourism Planning and Research, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China b Department ofUrban Planning and Design, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, SAR, People's Republic of China c

The Department of Tourism and Hospitality Management, The University of Waikato Management School,Hamilton, New Zealand

First Published:September2009

To cite this Article Zhang, C. Z., Xu, H. G., Su, B. T. and Ryan, C.(2009)'Visitors' perceptions of the use of cable cars and lifts inWulingyuan World Heritage Site, China',Journal of Sustainable Tourism,17:5,551 — 566

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09669580902780745

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669580902780745

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Journal of Sustainable TourismVol. 17, No. 5, September 2009, 551–566

Visitors’ perceptions of the use of cable cars and lifts in WulingyuanWorld Heritage Site, China

C.Z. Zhanga, H.G. Xua, B.T. Sub and C. Ryanc∗

aCentre of Tourism Planning and Research, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China;bDepartment of Urban Planning and Design, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR,People’s Republic of China; cThe Department of Tourism and Hospitality Management, TheUniversity of Waikato Management School, Hamilton, New Zealand

(Received 14 April 2008; final version received 13 January 2009)

This paper examines perceptions and attitudes towards the use of cable cars with specificreference to Wulingyuan World Heritage Site in China. A total of 45 respondents wereinterviewed using open-ended questioning and semi-structured interviews. Thematicanalysis suggests six motives for the use of the lift: (1) tight schedules generated bytravel agents and tour operators, (2) lack of physical strength to walk to the summit,(3) group membership influences, (4) the saving of time, (5) lack of information aboutalternative approaches and (6) novelty of the lift. However, when questioned aboutsources of satisfaction, respondents tended to refer to other aspects of their visit. Thisraises questions of managerial significance, as in the past the construction of such liftsand cableways has been based on a premise of enhancing visitors’ satisfaction withtheir visit, and this perceived advantage has been seen as outweighing possible adverseenvironmental impacts

Keywords: China; national parks; environment; cable cars; visitor satisfaction

Introduction

This paper is divided into the following sections. First, it briefly reviews the cases made forand against the use of cable cars, scenic railways and lifts in areas of outstanding naturalbeauty, with special reference to China. Second, it describes developments at Wulingyuan.Third, it briefly reviews a literature about measuring satisfaction, personal construct theoryand thematic analysis. The paper then introduces themes discerned from interviews with45 respondents at Wulingyuan, and subsequently provides supporting evidence for thosethemes. The paper also argues that sources of satisfaction are primarily derived from sitefeatures other than the lift, and thus discusses the findings in terms of claims made thatyet more lifts, cableways or scenic railways are required to generate higher levels of visitorsatisfaction. The data are derived from two sources. The first, as noted above, relates toon-site interviews, and the second was derived from comments made by visitors that relateto Wulingyuan found on a popular Chinese travel web page.

The use of cable cars, scenic railways and lifts in Chinese national parks

There are many issues in the management of natural and heritage sites that are generally wellunderstood in Western countries, yet which can become more complex within a Chinese

∗Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

ISSN 0966-9582 print / ISSN 1747-7646 onlineC© 2009 Taylor & FrancisDOI: 10.1080/09669580902780745http://www.informaworld.com

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

552 C.Z. Zhang et al.

setting. One such issue is the construction of cable cars as a mass transport system inChina’s national parks. The use of cable cars, scenic railways and lifts is, of course, notunique to China. For example, Simmons (2005, p. 145) draws attention to the narrow gaugerail systems of the European Alps and their initial role in the transport of materials for theconstruction of facilities for an emergent tourism industry and its need for accommodation,and the subsequent use of these facilities since the 1950s as a “self-conscious tourist scene”.Indeed, in North Wales a symbiotic relationship exists between rail transport, past industrialneeds (for construction, mining and the slate industry), heritage and contemporary tourismwhere the ride becomes both a means of sightseeing and a tourist experience in its own right(e.g. Morgan, 2002) as evidenced by the Snowdon Mountain Railway and the Festiniog–Welsh Highland Railway. This is not a unique example. Halsall (2001) specifically drawsattention to rail trips as a means of framing the tourist gaze in a context of heritage tourismin the Netherlands, while Hall (1999) has discussed transport as a gatekeeper to culturalcontact.

Transportation systems thus form a nexus between differing aspects of the tourismsystem. They are not simply transport systems for the movement of people and goods, butare an experience of movement offering changing scenery, can frame landscapes throughunintentional or intentional sight selection and, depending upon mode of transport, createa potential heritage product. Yet as Hall (1999) argues, there are issues of equality andexternalities associated with transportation systems. The issues of equality can be clearlyfound, and one such example is the role of transport in taking visitors to a communitywhile offering no compensation to that community for the intrusion impacts that result.Sai, Ryan, He and Gu (2009) provide one such Chinese example with reference to the HolyTaoist Mountain at Qiyun where no concessions are made to a low-income community bya private sector developer who has constructed a cable car used by tourists to reach thevillage. Local children thus face a three-hour walk to and from school, while visitors cancover the distance in but a fraction of the time. Ease and nature of access also change thenature of the visitor experience. One obvious potential factor is that easier access may leadto greater crowding at the site.

In China a past lack of, and at times a less than rigorous application of, planning rulesand guidelines has led to an emergent debate about the role of cable cars, lifts and scenic railsystems in national parks. As with any controversial issue, there are two sides. Supporters ofcable cars argue that they have advantages over alternative rail and road systems. They areseen as less intrusive on local geography, of being less adversely affected by weather, requirelittle space and do not discharge waste water, gases or waste solids. They offer less noisepollution, are relatively safe, easy to operate and can effectively transport large numbers ofpeople while offering scenic views. They can be less costly to build than alternative modesof transport, are less costly to run and maintain and thus offer better financial returns. Theyconsume less energy per passenger carried and can be a tourist attraction in their own right,thereby helping to enhance the visitor experience (Jiang, 2000; Sofield & Li, 2003). Thus,a commentator such as Xie (2000) argues that cableways should be recognised for theirmerits in promoting the development of mountainous scenic spots and be employed as aneffective means in the sustainable development of mountain scenic areas used for tourism.

A contrary view exists, and Hou, Wu and Xie (2000), when considering the use ofcableways in Taishan built in 1980, point to the blasting of small parts of the mountain inthe construction of the cable car system. The consequence, it is argued, is adverse impacts onthe topography of the mountain and a loss of natural beauty and flora with adverse impactson fauna. They argue that the ease of taking large numbers of visitors to the summit has ledto over-commercialisation, a newly urbanised setting in what should be a place of natural

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 553

Figure 1. The One-Hundred Dragon Lift.

beauty, and hence environmental degradation. Additionally, the very ease of ascent robstourists of the pleasure of climbing the mountain while the time spent appreciating thenatural setting becomes both foreshortened and different in nature. Additionally, touristrevenue per tourist is less in Tai’an than would otherwise be the case, and it is arguedthat the only real beneficiaries are the cableway operators (Hou et al., 2000). Xie (2000) isanother critic who maintains sightseeing cable cars cause irreversible damage to topography,vegetation, ecology and the beauty of scenic areas, including World Heritage Sites. He tooargues that they change the nature of the visitor experience, and contends that they shouldnot be built in World Heritage Sites, but outside of the designated areas. Xie (2000) continuesto argue that tourist needs should not be blindly met at the expense of the heritage itself.

In the absence of empirical evidence as to tourist perceptions of cable cars, and theireffects, proposals for their construction continue to be made, and equally controversyfollows such propositions. Past and current projects include those at Taishan, HuangshanEmei Shan, Wudang Shan and elsewhere. Since 1992, when Wulingyuan was designateda World Natural Heritage Site, the local government has successively built two cableways,one railway and one elevator, for sightseeing (see Figure 1). There are now proposals fora further cableway motivated by a wish to better meet the needs of tourists. The questionarises, what are those needs, and how do visitors perceive existing cable cars?

The Wulingyuan cable cars and lifts

Wulingyuan is located in the Wuling Mountain Range in the administrative area ofZhangjiajie City in the northwest of Hunan Province. Covering an area of 397 squarekilometres, the zone includes Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, Tianzishan Scenic Area,

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

554 C.Z. Zhang et al.

Suoxiyu Natural Reserve Area and Yangjiajie Scenic Zone – these areas account for 264square kilometres. Possessing a subtropical monsoon climate its annual mean temperatureis 13.4◦C, thereby avoiding scorching heat in summer and severe cold in winter. Its majortopographical features are its quartz sandstone peaks, which have given rise to soubriquetssuch as “scaled-up pots and scaled-down heaven”. A full description of the eco-system isprovided by Fu (2003).

In 1982 Zhangjiajie Forest Farm, as it was initially known, was designated as China’sfirst National Forest Park, after which it was sequentially designated as a National Parkby the State Council, listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, and then classifiedas an AAAAA scenic spot by the National Tourism Bureau, a National Geological Parkby the Ministry of Land and Resources and then again by UNESCO, as a World Geo-logical Park (Zhong, Deng, & Xiang, 2008). One result has been a growing number ofvisitors, from 83,700 in 1982 to over 2.2 million in 2006, making it one of China’s mostpopular heritage destinations. Figure 2 demonstrates the growth in visitor numbers. In anattempt to improve the flow of visitors by reducing the time required to reach the summit,in 1990 the site management sought investment for a cable car. As a result, in 1996, theHuangshizhai and Tianzishan Cableways were constructed and soon became one of thelargest sources of tax revenue for local government, thereby predisposing that governmentto favour more similar projects. In 1998 a sightseeing railway line was built, earning thedisapproval of UNESCO on grounds of over-urbanisation and degradation of the authen-ticity and integrity of the heritage. Central government became involved, and after a visitby the then prime minster, Rongji Zhu, the demolition of the railway was ordered. How-ever, even while this was being undertaken, another new tourist transportation project wasinitiated, namely the One-Hundred Dragon Lift (see Figure 1). Situated right at the centreof Wulingyuan Heritage Site, the lift was built into the side of the mountain and is able totake passengers to the top of the mountain within 1 minute and 58 seconds. The projectwas accompanied by controversy, but construction was completed in August 2003, and itquickly became another major source of taxation revenue for the local government. Indeed,its very success in attracting visitors has recently led to a proposal for yet another cablewayproject, with a view of easing pressure on the scenic area and so further enhancing touristsatisfaction.

Figure 2. Visitor numbers to Wulingyuan World Heritage Site over 1982–2007. Source: WulingyuanTourism Bureau.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 555

Literature review

Within the academic tourism literature generated by Western scholars, the subject oftourist satisfaction occupies a position within the mainstream. Generally, confirmation–disconfirmation models have held the centre ground, that is, following Pizam, Neumannand Reichel (1978), satisfaction is measured by a comparison between pre-travel expec-tations and evaluations of experiences at the destination. This approach was reinforcedby the Service Quality (ServQual) Scale (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1988) and itssubsequent derivatives such as the Service Performance (ServPerf) Scale (Cronin & Taylor,1992, 1994) and the Holiday Satisfaction (HolSat) Scale (Tribe & Snaith, 1998). An-other common approach is that of the Importance-Performance Analysis Model (Fishbein,Martilla, & James, 1977). These various models have been subjected to a range of criticisms.Ryan (1999) has suggested that ServQual and its derivatives are poorly applied to tourismsituations and fail to recognise the role of the tourist as an “actor” in prolonged serviceexperiences whereby cognitive dissonance can easily play a role. That is, if a componentof the visitor experience fails to meet expectations, the tourist may well attach lower levelsof importance to that component and thus still enjoy high levels of overall satisfaction.Given the time-constrained and multi-faceted nature of many holidays, many tourists maysimply seek to achieve a goal of holiday satisfaction by adapting behaviours different tothose initially anticipated (e.g. Elliot & Devine, 1994; Ryan, 2002). Other technical criti-cisms also apply, and in 1994 Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry responded to these, but inways that made the practical application of the original scale more problematic. Oh (2001)has similarly pointed out problems with applications of importance-performance models,although arguably the model is more psychologically stable given the stability of “impor-tance” as a psychological concept, at least over the intermediate term. Ryan and Huyton(2002) in a study of visitor perceptions of Australian aboriginal product questioned whetherimportance and performance/evaluation were independent variables, again implying thattourists are themselves an important variable in the creation of satisfaction. That touristsare not passive players in the creation of tourist experiences has long been recognised. Forexample, Yiannakis and Gibson (1992) and Gibson and Yiannakis (2002) have elucidatedthe roles that can be adopted by tourists and the changes in role adopted over an individual’slife stage.

Recently, it has become increasingly recognised that satisfaction may well be place- andtime-specific (Haber & Lerner, 1999), that roles played and satisfactions derived may alsobe dependent upon the company kept (Trauer & Ryan, 2005) and that satisfaction derivedmay be part of a longer term relationship with place and/or activity through theories ofinvolvement (McIntyre, 1989) and repeat purchase or consumer loyalty (Chioveanu, 2008).Macintosh (2003) has introduced the importance of trust in the relationship of satisfactionand perceived quality, while the critical incident literature also has an important role to playwhen considering service quality (Bitner, Booms, & Tetrault, 1990).

Many of these studies are supported by empirical data derived from quantitative mea-sures, and herein may lie a potential problem. In reviewing a tradition of Western post-positivistic research, Ryan, Gu and Zhang (2008, p. 327) write, “It has become increasinglyclear to us in our own past research and in the reviewing of the chapters . . . that simplytransferring concepts from western academic literature to inform research in China is, atleast for the present, not wholly appropriate”. They advance several reasons for this thatinclude cultural differences, differences in forms of tourism planning, concepts of the har-monious society and a scientific approach, the dismantling of statism, the emphasis onsocialist markets with a Chinese perspective and the importance of relationship-building.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

556 C.Z. Zhang et al.

Additionally, while differences in value systems may exist across nationalities, simi-larly subsystems of value difference can exist between different users of sites and theirperceptions of place. For example, with reference to understandings of natural places,Higham (1998) draws distinctions between four understandings of “wilderness” – thesebeing “wilderness of pristine ecology”, “phenomenal wilderness”, “legal wilderness” and“perceptual wilderness”. The very fact that the terminology is itself value-laden reflectsboth conceptual difficulties of definition and the different understandings, experiences andinterpretations of any given location that may be attributed to that place by different people.In short, place is as much a construction of meaning as a geological entity.

The research

If these arguments are valid, they reinforce a need to return to more basic forms of researchthat involve direct questioning of tourists at their site, and asking for their views withoutreference to a questionnaire that may imply a researcher-led perspective of attitudinal di-mensions. On the other hand, the criticism often made of qualitative research is that it doesnot permit generalisation, but one potential response to this lies in personal construct the-ory. While recognising that individuals filter experiences and make sense of them throughtheir own neural networks formed by socialisation and experience, Allport (1961, 1968)argued that people are able to communicate successfully through shared languages andunderstandings. Without these shared meanings, communication would simply not be pos-sible. These meanings often revolve around a comparatively minimal number of attitudinaldimensions, and thus he devised means of questioning that could elicit those dimensions.However, it was subsequently argued by Bowler and Warburton (1986) that a commonalityof dimensions is also revealed through repetitive patterns. For example, if a given numberof people are asked about what makes a location attractive as a holiday destination, and alarge proportion mention warm, sunny weather, then it can be concluded that this aspect ofclimate represents at least a salient component within the formation of attitudes. Salienceitself is not necessarily a measure of importance, and indeed commentators such as Legoand Shaw (1992) and Ryan (1995) comment on the need for distinctions between salience,importance and determinance. Given these caveats, the current researchers felt there wassufficient legitimacy in simply asking respondents at Wulingyuan why they used the lift,and what they thought of it.

A sample of 45 respondents were interviewed over a period of three days betweenthe hours of 8.00 to 10.00 am, which was the peak period for cable car use by departingtourists who had stayed the previous night at an accommodation on the summit. The samplewas selected by the researchers standing at the end of the queue of those waiting for thelift to descend to the ground. Every fifth or sixth person joining the queue was asked ifthey would mind answering a series of questions relating to three main themes, namely(1) why did you take the cable car/lift? (2) what gave you satisfaction during your visitto Wulingyuan? and (3) what caused you dissatisfaction during your visit to Wulingyuan?If a respondent did not wish to participate, then the next fifth or sixth person joining thequeue was approached. In total 120 people were approached, and of these, 45 providedanswers for each question asked. Of the remaining 75 potential respondents, just over halfdid not wish to participate, and the remainder fell into two more or less equal groups. Thefirst comprised those who simply wished to make complaints about the length of queue,treatment by staff, accommodation, tour group arrangements, travel agent promises and amix of other miscellaneous items. While such responses represent data that were recorded,such data were not used in the analysis. However, cross-checking between these comments

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 557

and those of the 45 respondents who fully answered the questions reveals little differencein potential sources of dissatisfaction. The remainder of the 75 simply failed to answer allof the questions. Reasons for failure were primarily the queue moving on and interruptionsfrom family members. When the lift arrived, quite significant shifts in the queue couldoccur.

Interviewing ended after 45 respondents because high levels of repetition in the an-swers were becoming evident – a phenomenon consistent with personal construct theory.Additional secondary data to help assess the importance (as distinct from salience) thatmight be attributed to elicited comments involved an inspection of online tourism forums.The main one was www.ctrip.com. A search conducted on this site using the terms suchas “destination guidance+Hunan Province+Zhangjiajie+destination comments” obtained“diary” comments. This search covered the period of 1 January 2004 to 1 July 2007. All thecomments were transferred to Word files, duly “cleaned” by the authors to ensure relevanceand validity for the research topic – that is, for example, personal comments about friendsand other items thought irrelevant were deleted. In total, this left 137 diary entries forcontent analysis.

These data were recorded and supplemented by notes and observations collected fromthe site. The first three authors then undertook an independent thematic analysis prior toa comparison of interpretations. Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 77) argue that while thematicanalysis is a “poorly demarcated and rarely acknowledged, yet widely used qualitativetechnique”, it can generate detailed insights, especially when carried out in a rigorousmanner. One means of ensuring that this is the case is to ensure that more than oneresearcher is involved, and that cross-checking of categories and text is undertaken initiallyindependently and then through consensual approaches to apparent discrepancies. This wasundertaken in this instance.

The results

Six major themes were identified in the text derived from the 45 interviews. The themeswere:

(1) Tight schedules organised by tour operators and travel agents. It was found that about70% of the cableway passengers used the cableway and/or lift because of this reason.Often the comments were based on statements such as “the travel schedule is too tight”or “If we don’t agree to take the cableway, the travel agent will cancel this stop”. Sometour guides allegedly provided false information, saying that “this cableway/lift is theonly way up the hill”. According to local park and tourism management staff, 90%of the tourists visiting Wulingyuan are in tour groups organised by travel agents. It isobvious that the decisions are influenced by profit-driven agents often preferring thecableways/lifts in order to obtain commissions from the operators.

(2) Doubts about physical ability. It is suggested that three possible scenarios generatethis theme. First, many tourists do not intend to exert themselves too much, and theyexpect to have a relaxed and easy trip. Second, while some may be willing to walk, theyare concerned about the summer heat and/or think that climbing is too much for thembecause they have been travelling for several days and are beginning to feel tired. Thethird reason relates to the perceived lack of time because of (1) above.

(3) Group cohesiveness. As noted above, the majority of tourists to Wulingyuan are pack-aged tourists and they are susceptible to the influence of the group. Interviews revealthat some tourists initially intended to walk up the mountain, but when the tour guides

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

558 C.Z. Zhang et al.

solicited opinions, they changed their minds because “80% of the people want to rideon the cableway” or “I have the strength and want to walk, but my colleagues do notagree”. Under such circumstances, they feel they have little choice but to take the cablecar or lift.

(4) Saves time to create more value for money. The interviews show that some touristschoose the cableway because walking up the mountain takes more time, which translatesinto either or both an opportunity or monetary cost for each tourist. The interviewsindicate that some tourists are motivated by a wish to see as much as is possible, andthus they do not wish to stay too long at any one place. Cableways make this possiblebecause they can see the heights, take in the view, do so cost- and time-efficiently, andthen progress to another location.

(5) Asymmetry of information. Quite simply tourists do not know about alternative meansof getting to the summit, or the information is withheld from them.

(6) Novelty and curiosity. It was found that some tourists ride the cableway or take the liftout of curiosity because the rides are novel. These were found to be specifically trueof the One-Hundred Dragon Lift because of its high profile gained during the debatein the media as to whether to demolish or retain it. Additionally, the lift is marketed asholding three world records. It has thus become an attraction in itself.

Table 1 summarises the data and some of the comments supporting the themes. Thesethemes were also supported by data derived from a previous study undertaken by Li (2004),which are summarised in Table 2. Li’s (2004) study might be said to reinforce themes ofsaving effort and time, convenience and comfort, and a means of viewing the scenery.Given this, the question arises, to what extent do these advantages add to the degrees ofsatisfaction gained from visiting Wulingyuan, or are they simply secondary sources ofsatisfaction? Questioning respondents about the lift and the cable car elicited two broadcategories of comments. The first, the positive, related to the views obtained from the cablecar/lift, while the speed of the lift was also favourably commented upon. Against that, therewere many more negative than positive comments. The complaints mainly fell into threecategories, namely “waiting in line for too long”, “unreasonable management of children’stickets” and “poor staff attitudes” (see Table 3 for indicative comments).

The second mode of questioning sought to establish an overall context of the sourcesof satisfaction with the visit, thereby more clearly establishing the framework within whichissues pertaining to the lift and cable car could be established. As indicated above, and in anattempt to avoid a researcher-led agenda, an open-ended question was put to the respondentsabout their trip to Wulingyuan as to what gave cause to be satisfied or dissatisfied. Themajor cause of satisfaction with the trip was the scenery. This was variously described as“beautiful”, “magnificent” and “breath-taking” with additional allusions to literature andpoetry. All of the respondents made references of this kind, and there is little doubt thatWulingyuan merits its official categorisations as an area of natural beauty and heritage. Onthe negative side, there was an almost equally unanimous criticism of the local vendors andthose associated with the supply of services at the site. Overcharging, poor quality serviceand the itinerary organised by travel agents were among the subjects specifically noted forcriticism. The time spent in queues for the lifts was another commonly commented item.These criticisms are summarised with indicative comments in Table 4.

One common criticism made of qualitative research based on small samples is that thevery nature of the sample may inhibit any generalisation of results. At least two reasonslie behind such criticisms. First, the very small numbers involved raise issues about howrepresentative might the sample be of the target population. Second, by the very nature of

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 559

Table 1. Reasons for cableway/lift riding.

Reasons Details

Taking thecableway/lift

Arranged or persuaded by tourguides

We are arranged to take cableway by the travelagent.

The travel agent would cancel this stop iftourists don’t agree to take the cableway.

The schedule designed by the travel agent istoo tight for walking.

The tour guide said the lift is the only way up.Doubts about physical ability Too tired to climb up for two days in a row.

It’s easy and quick to ride on the cablewaycompared to walking.

It’s physically too challenging for me.I’m already exhausted from yesterday’s

climbing.It’s too hot.

Group cohesiveness Eighty percent of the teammates want to takethe cableway, and we should stay together.

I’m strong and I want to climb, but most of theothers don’t want to.

Saves time to create more valuefor money

It takes too long to walk up. And I’ll have tospend the night on top, which will cost memore, and my trip will be prolonged.

If time permits, I’ll walk. If it doesn’t, I’ll haveto take the cableway.

Asymmetry of information Don’t know if there is any road or trail.I’m afraid I’ll lose my way.

Novelty The cableway is interesting, and I’d like toexperience it.

I’ve climbed the mountain before, so I’ll takethe cableway this time.

No other choices Now we have only two choices, walking all theway up or taking the lift straight to the peak.It would be better if we could get to themid-level by car, then start walk to the peak.There is just too few transport meansavailable here.

Walking Enough time Two hours of walking is acceptable.I’ll walk if time permits.

Physical strength By walking, I can enjoy the beautiful scenerywhile exercising.

Walking either uphill or downhill isacceptable, but not both.

Source: Current study.

the technique, bias might arise whereby the more articulate are giving priority over the lessarticulate. On the other hand, as described in the literature review, personal construct theorywould lead one to argue that the same comments would be found in other sources. To assesswhether this was the case, the first three researchers scanned a series of online tourism fo-rums where people comment on the nature of trips taken in China. These sources included fo-rums such as Ctrip (www.ctrip.com). Again the text was extracted and subjected to thematicanalysis. In this instance, the sample comprised 137 “diaries”. The results are summarised inTable 5. As expected, scenic quality was the most important factor for satisfying tourists.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

560 C.Z. Zhang et al.

Table 2. Reasons for the selection of cable cars or lift inWulingyuan.

Reasons %

Only means of travel available 2.6Requires less effort 48.1Time saving 55.3Comfortable 44.4Fashionable 14.7Appreciate the scenery from a different angle 33.5Arrangement of the travel agent 13.9

Source: Li (2004).

Table 3. Tourists’ evaluation of the cable car/lift in Wulingyuan.

Category Evaluation

Positive Beautiful scenery from the cableway/lift.Very quick to get to the top.

Negative Have to wait for a long time in line for the cableway/lift.Waited too long in line. This severely spoiled my desire to continue the trip.The staff here are not nice.It took a long time for our tour guide to buy the tickets for the cableway/lift because of

the inefficiency of the ticket office.It is tough for old people, due to the long time in line and the poor environment in the

queuing area.Children taller than 1.2m have to present a student card to buy a discounted student

ticket, but they should know better and that not every primary school student inChina has the card in the first place.

Source: Current study.

Table 4. Factors impinging on overall satisfaction.

Category Factor Comments of tourists

Factors enhancing satisfaction Scenic beauty The scenery is splendid.Factors undermining

satisfactionIntegrity of small business

operatorsThose vendors are not being

honest.Service quality Waiting time is too long.

The schedule set by the travelagent is inconsiderate. We’re nothaving enough sleep and thefood is terrible.

The managers are not nice.Service quality is poor.Children have to buy full tickets

for not having a student card.Prices The entrance ticket is too

expensive.

Source: Current study.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 561

Table 5. Analysis of comments about Wulingyuan derived from online forums.

Category Factor Comments

Satisfactory Scenic quality The scenery is indeed magnificent. It’s like heaven onearth.

The folk songs are beautiful, very impressive.Unsatisfactory Business ethics of

small businessoperators

You can be ripped off anytime, anywhere. This is a rarecase among all the scenic areas.

The shopping area is like a den of thieves.You can even be ripped off in the temple.

Friendliness of localpeople

I’m impressed by how unfriendly the local people arerather than how beautiful the scenery is.

I lost my cell phone on one of the buses, which gaveme a very bad impression about the local people.

Service quality It’s hard for you to see a smile on the faces of theservice people. You’d feel that you are beingmistreated. And the locals are very arrogant.

It’s good that there are many tour guides. But some arevery rude to you when you don’t hire them.

The security guy gave the cold shoulder to people whocomplained about the long line in front of thecableway station and even swore at them.

My tour guide had a bad attitude, but not “a cleartongue”.

Waiting time I spent half of my time there waiting in line.We intended to see the sun rose, but it had risen before

the coach came to pick us up.Integrated service

packageHot water and air conditioning in the hotel were only

available after 19:00. What’s worse is that the hotwater lasted for only 2 hours, and the air conditionerwas out of service after midnight.

Environmentalmanagement

Many creeks are dry and filled with pebbles andweeds. Seems that they are not doing a good job intaking care of the environment.

Equal treatment The locals are nicer to Koreans. They even help themto cut in lines or save places in the queues.

There are too many Korean words on the menuswithout Chinese translation. We feel that we arebeing discriminated against.

Source: Current study.

Most commentators reinforced a perception that the scenery at Wulingyuan is “wonderful”and “well worth the money and effort” made in travelling to the site. Only a small minorityfelt that the scenery failed to match that shown in commercials. Additionally, for a smallminority other aspects were found more appealing. For example, one tourist commentedthat it was the folk songs of Wulingyuan that impressed him the most. Other reasons thatcaused satisfaction related to social motives, such as being able to share the scenery withothers close to them.

Tourist dissatisfaction was again mainly caused by factors related to service and man-agement. According to the comments, tourists are dissatisfied with the lack of businessethics shown by the small business operators, the unfriendliness of local people, poor ser-vice attitudes, the long time spent waiting in line for the rides, unequal treatment, poorlyintegrated services, poor environmental management and so on. In short, the findings are

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

562 C.Z. Zhang et al.

consistent with those noted in the primary data collection. The comments made about thespecial attention being provided to the Korean market also independently confirms theobservations made by Zhong et al. (2008) with reference to the importance of the Koreanmarket and the specific targeting of that market by the Park authorities. Additionally, Zhonget al. also comment about the ability of the local communities to absorb larger numbers oftourists, and it is this that might be adversely affecting the interaction with visitors.

Discussion

The study shows that the cableway/lift can meet the needs of tourists on three levels. Thefirst is their need to save time, energy and experience something new. The second refersto the needs created by peer pressure and feelings of group cohesiveness. The third is theimposed need to adhere to schedules determined by tour guides and travel agents, a needreinforced by the asymmetry of information where many tourists have not been able toaccess alternative sources of information and hence routes that may be open to them.

The main source of satisfaction lies in Wulingyuan’s scenic quality, but this is compro-mised by the perceived unethical conduct of small business operators, poor service quality,unfriendly local people and long hours of waiting in line to get on the cableway/lift. Whilethe cableway and lift can facilitate tourists’ movement, they do not necessarily contributeto their overall satisfaction. Instead, their inadequacies directly cause dissatisfaction. Thisfinding is open to several different but related interpretations. These include, but are notlimited to, the following:

(1) A need to construct a further lift or cableway as a means of reducing the queuing times.(2) A need to revisit the management plan.(3) Overall satisfaction can be enhanced by better service and management practices.(4) A need might exist for the installation of a quota system, or a need to reduce visitor

numbers, perhaps by yet further increasing prices while enhancing “value for money”through better services.

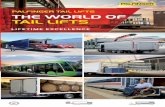

Each of these points are now considered in turn with reference to Figure 3. Figure 3illustrates the condition of a group-based market with schedules run for the benefit of touragencies and tour guides. The establishment of a new cableway system or similar will reducequeuing times, ease tour-scheduling concerns and perhaps create more retail opportunities.Additionally, growing numbers of visitors may initially lead to yet more congestion – allof which also adds to greater profit in the short term for the private sector companies but,ceteris paribus, such congestion will lead to a demand for new cable cars that will requiremore investment. However, by overcoming bottlenecks in the transfer of visitors, the cablecar companies, tour agencies and local government will obtain additional revenue fromsales, profits and taxation. The alternative is to fail to build a cableway system on groundsof limiting further damage to the local environment, but to sustain sales and tax revenuesthrough higher prices – with those prices being supported by a promise of less congestionand better management practices to address the complaints noted in the results. This impliesa shift from a price-sensitive market to one that is a more price-value aware market.

This clearly identifies a current problem in the Chinese domestic tourism market that hasbeen commented upon by different authors. For example, Zhang (2006) notes how attemptsto meet growing demand have led to a “tragedy of the commons” whereby such attemptssimply change the nature of the site and the experience with both becoming degraded. Inpart this reflects a possible immaturity within the Chinese tourism industry, but as noted by

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 563

Guide seeking for benefit

Promote for group touristsMore cable cars to save

time for purchase

Congestion in cable car Higher profit For cable car

New cable or similar transportation

Stakeholder cooperation

Appeal for more cablecars with the excuse ofmeeting the needs of

vistors

Group-based market

Limited cable car

Limited world nature heritage Increase the price of

entrance fee

Fail to build cableway

Tourists are not price-sensitive

Imm

ature condition for new m

arket

Figure 3. Consequences of cable/lift construction.

Gu and Ryan (2008b), Chinese tourism is driven by parameters that include tolerance ofhigher numbers due to population size, governmental policies directed by a need to maintainincome generation to lift millions from poverty, different perspectives on human–naturerelationships (see also Li & Sofield, 2008; Sofield & Li, 1998a, 1998b) and strong profitmotive within a still relatively young private sector that places economic gain above otherissues incorporated in concepts of corporate social responsibility. While Buckley, Cater,Zhong and Tian (2008) identify shengtai luyou as a Chinese conceptualisation akin to “eco-tourism”, the reality of much national park planning in China is that it is particularistic withdivided responsibilities between many different organisations. Thus, a World Heritage Sitesuch as Wulinyuan can be administered by different bodies including the National ForestryMinistry, National Construction Ministry and the National Tourism Administration withdiffering plans also being administered by lower provincial and municipal governments.An example of this is provided in the case of Qufu by Ma, Si and Zhang (2008), while Lai,Li and Feng (2006) also criticise plan formation and implementation, noting significantdivisions between them in the case of the 2001–2020 Guniujiang Guanyintang RegionalTourism Development Master Plan.

With reference to the issues of satisfaction noted above, it does appear that overallsatisfaction is severely compromised by poor service quality and management skills. It alsoappears that the results of this study are consistent with Motivation-Hygiene Theory de-scribed by Gu and Ryan (2008a) with reference to Chinese hotels, and which is based uponthe earlier work of Herzburg, Mauser and Synderman (1959). Simply put, some factors maynot provide positive satisfaction, but dissatisfaction results from their absence, such as shortqueues and information brochures. The improvement of service and management skills mayeliminate dissatisfaction, and perhaps create a series of positive critical incidents (Bitneret al., 1990). Currently, from the above evidence, poor service appears to be producing

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

564 C.Z. Zhang et al.

negative critical incidents. Cableway and lifts can act as motivators to induce more satis-faction if properly operated, but evidence exists in this study that in many instances thenegative experiences undermine the potentially positive due to poor service, overcrowdingand too tight a schedule.

Conclusions

It is suggested that this case is not unique within the Chinese setting, and may have widerimplications for many developing economies where tourism is primarily being driven byeconomic needs. The argument that tourist needs are primary is often justified by referenceto job and income creation in areas that are not conducive to other forms of economicactivity, and yet where there is a wish to offset a drift away from rural areas into urbanconurbations. As noted by Zhang (2006), current practice in China potentially denies longerterm success while degrading local environments. The problems are evident from the studyand observation of the site, while the solutions require changes in thinking and practice thatcan often seem difficult to achieve. However, there does exist past evidence of progress.For example, in 2001 hotels that had been constructed at the top of the mountain weredemolished, and small scale accommodation in local people’s homes is now beginningagain after being prohibited in the early years of the first decade of the current century.This is being licensed and is consistent with the development of cultural tourism basedon the minority peoples who live in the area, namely the Tu, Miao and Bai ethnic groups.Zhong et al. (2008) provide evidence of some of the wider problems of this region andthe corrective measures being undertaken, while Gu and Ryan (2008b) draw attention tothe changing rhetoric of the National People’s Congress of March 2008 and the growingemphasis upon good environmental practices supported by an increasing intolerance ofpast corrupt practices and the institution of tight monitoring procedures. China, in short, isa country in transition, and that is as true of its tourism industry and practices as of otherparts of its socio-economic–political system.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the National Science Foundation ofChina for supporting the research (project serial number: 70503007). They would also liketo thank students and officials who facilitated the research, the referees and additionallyBernard Lane, co-editor of this journal, for his insightful comments.

Notes on contributor/sC.Z. (Taylor) Zhang is an Assistant Professor at Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou.

Xu Honggang is a Professor of Tourism at Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou.

Dr B.T. Su holds a research post at the University of Hong Kong’s Department of Urban Planningand Design.

Chris Ryan is Professor of Tourism at the University of Waikato and editor of Tourism Management.

ReferencesAllport, G. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.Allport, G. (1968). The person in psychology: Selected essays. Boston: Beacon Press.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

Journal of Sustainable Tourism 565

Bitner, M.J., Booms, B.H., & Tetreault, M.S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favourableand unfavourable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(January), 71–84.

Bowler, I., & Warburton, P. (1986). An experiment in the analysis of cognitive images of the environ-ment: The case of water resources in Leicestershire. Leicester University Geography Department,Occasional Paper no. 14.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research inPsychology, 3, 77–101.

Buckley, R., Cater, C., Zhong, L., & Tian, C. (2008). Shengtai luyou: Cross-cultural comparison inecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(4), 945–968.

Chioveanu, I. (2008). Advertising, brand loyalty and pricing. Games and Economic Behavior, 64(1),68–80.

Cronin, J.J. Jr., & Taylor, S.A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension.Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68.

Cronin, J., & Taylor, S. (1994). SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL: Reconciling performance-basedand perceptions-minus-expectations measurement of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 58,125–131.

Elliot, A.J., & Devine, P.G. (1994). On the motivational nature of cognitive dissonance: Disso-nance as psychological discomfort. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 382–394.

Fishbein, M., Martilla, J.A., & James, J.C. (1977). Importance-performance analysis. Journal ofMarketing, 41, 77–79.

Fu Yan. (2003). Conservation for the landscape ecological diversity in Wulingyuan scenic area ofChina. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 15(2), 284–288.

Gibson, H., & Yiannakis, A. (2002). Tourist roles: Needs and the lifecourse. Annals of TourismResearch, 29(2), 358–383.

Gu, H., & Ryan, C. (2008a). Chinese clientele at Chinese hotels – Preferences and satisfaction.International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(3), 337–345.

Gu, H., & Ryan, C. (2008b). Hongcun and Xidi: Rural townships’ Experiences of Tourism. In C.Ryan & H. Gu (Eds.), Tourism in China: Destinations, cultures and communities (pp 259–267).New York: Routledge.

Haber, S., & Lerner, M. (1999). Correlates of tourism satisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(1),197–200.

Hall, D.R. (1999). Conceptualising tourism transport: Inequality and externality issues. Journal ofTransport Geography, 7(3), 181–188.

Halsall, D.A. (2001). Railway heritage and the tourist gaze: Stoomtram Hoorn-Medemblik. Journalof Transport Geography, 9, 151–160.

Herzburg, F., Mauser, B., & Synderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley.Higham, J. (1998). Sustaining the physical and social dimensions of wilderness tourism: The percep-

tual approach to wilderness management in New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 6(1),26–51.

Hou, R.Z., Wu, L.Y., & Xie, N.G. (2000). Protect Mount Tai, detach the cableway. Chinese Garden,(5), 9–11 (in Chinese).

Jiang, N. (2000). The legitimacy of cableways in tourist resorts. Tourism Tribune, (6), 61–63.Lai, K., Li, Y., & Feng, X. (2006). Gap between tourism planning and implementation: A case of

China. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1171–1180.Lego, R., & Shaw, R. (1992). Convergent validity in tourism research: An empirical analysis. Tourism

Management, 13(4), 387–393.Li, F.M.S., & Sofield, T.H.B. (2008). Huangshan (Yellow Mountain), China: The meaning of har-

monious relationships. In C. Ryan & H. Gu (Eds.), Tourism in China: Destinations: Culture,communities and planning (pp. 157–167). New York: Routledge.

Li, X.L. (2004). A study on the passengers of modern means of transport in tourist resorts: Casestudy of cableway and lift in Wulingyuan. Urban Planning Forum, (2), 72–76 (in Chinese).

Ma, A., Si, L., & Zhang, H. (2008). The evolution of cultural tourism: The example of Qufu, thebirthplace of Confucius. In C. Ryan & H. Gu (Eds.), Tourism in China: Destinations: Culture,communities and planning (pp. 182–196). New York: Routledge.

Macintosh, G. (2003). Building trust and satisfaction in travel counselor/client relationships. Journalof Travel and Tourism Marketing, 12(4), 59–74.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009

566 C.Z. Zhang et al.

McIntyre, N. (1989). The personal meaning of participation: Enduring involvement. Journal of LeisureResearch, 21(2), 357–359.

Morgan, D. (2002). The role of umbrella organizations in the development of heritage railways. JapanRailway and Transport Review, 32(September), 35–37.

Oh, H. (2001). Revisiting importance-performance analysis. Tourism Management, 22(6), 617–627.Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison

standard in measuring service quality: Implications for further research. Journal of Marketing,58(January), 111–24.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuringconsumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64, 12–40.

Pizam, A., Neumann, Y., & Reichel, A. (1978). Dimensions of tourist satisfaction with a destinationarea. Annals of Tourism Research, (5), 314–322.

Ryan, C. (1995). Researching tourist satisfaction. London: Routledge.Ryan, C. (1999). From the psychometrics of SERVQUAL to sex – Measurements of tourist satisfac-

tion. In A. Pizam & Y. Mansfeld (Eds.), Consumer behavior in travel & tourism (pp. 267–286).Binghamtom, NY: Haworth Press.

Ryan, C. (2002). The tourist experience. London: Continuum.Ryan, C., Gu, H., & Zhang, W. (2008). The context of Chinese tourism – An overview and implications

for research. In C. Ryan & H. Gu (Eds.), Tourism in China: Destinations: Culture, communitiesand planning (pp. 327–336). New York: Routledge.

Ryan, C., & Huyton, J. (2002). Tourists and aboriginal people. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3),631–647.

Sai, H.S.J, Ryan, C., He, Y., & Gu, H. (2009). Issues of Taoist tourism – The example of Mt Qiyun.Paper submitted to UNESCO-ICCROM Asian Academy for Heritage Management Conference,Macao. Institute for Tourism, Macau SAR.

Simmons, I.G. (2005). The mountains of Northern Europe: Towards an environmental history for thelast ten thousand years. In D.B.A. Thompson, M.F. Price, & C.A. Galbraith (Eds.), Mountainsof Northern Europe: Conservation, management, people and nature (pp. 141–150). London:Stationery Office Books.

Sofield, T.H.B., & Li, F.M.S. (1998a). China: Tourism development and cultural policies. Annals ofTourism Research, 25(2), 323–353.

Sofield, T.H.B., & Li, F.M.S. (1998b). Tourism development and cultural policies in China. Annals ofTourism Research, 25(2), 362–392.

Sofield, T.H.B., & Li, F.M.S. (2003). Processes in formulating an ecotourism policy for naturereserves in yunnan province, China. In D. A. Fennell & R.K. Dowling (Eds.), Ecotourism Policyand Planning (pp. 141–153). Wallingford: CAB International.

Trauer, B., & Ryan, C. (2005). Destination image, romance and place experience – An application ofintimacy theory in tourism. Tourism Management, 26(4), 481–492.

Tribe, J., & Snaith, T. (1998). From SERVQUAL to HOLSAT: Holiday satisfaction in Varadero, Cuba.Tourism Management, 19(1), 25–34.

Xie, C.F. (2000). Thinking about cableways in the scenic spots of China. Journal of South AnhuiIndustry Institute, (1), 21–15 (in Chinese).

Xie, N.G. (2000). The threats of cableways to World Heritage Sites. Tourism Tribune, (6), 57–60 (inChinese).

Yiannakis, H., & Gibson, H. (1992). Roles tourists play. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(2), 287–303.Zhang, C.Z. (2006). Tourism and heritage protection: An empirical study from the perspective of the

government management, p. 212. Beijing: China Tourism Press (in Chinese).Zhong, L., Deng, J., & Xiang, B. (2008). Zhangjiajie National Park: Evolution and the destination

life cycle. Tourism Management, 29(5), 841–856.

Downloaded At: 01:47 21 September 2009