USAID DAIRY COMPETITIVENESS PROJECT QUARTERLY ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of USAID DAIRY COMPETITIVENESS PROJECT QUARTERLY ...

UUSSAAIIDD DDAAIIRRYY CCOOMMPPEETTIITTIIVVEENNEESSSS PPRROOJJEECCTT

QUARTERLY REPORT

October 2008 - December 2008

USAID CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Submitted to

Fina Kayisanabo CTO USAID/Rwanda

Submitted by

Land O’Lakes, Inc. P.O. Box 64281

St. Paul, MN 55164-0281

January 2009

© Copyright 2009 by Land O’Lakes, Inc. All rights reserved.

USAID DAIRY SECTOR COMPETITIVENESS PROJECT

USAID CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

QUARTERLY REPORT

OCTOBER 1 – DECEMBER 31, 2008

Name of Project: USAID Dairy Sector Competitiveness Project

Regions: Nyagatare and Nyabisindu areas

Dates of project: November 15, 2007 – November 14, 2012

Total estimated federal funding: $ 4,999,995

Contact in Regional Office: Joe Carvalho Land O'Lakes/Kenya phone: +254-20-3748685 fax: +254-20-3745056 e-mail: [email protected] Contact in Rwanda: Roger Steinkamp Kigali, Rwanda Phone: +250 0533 6048 e-mail: [email protected] Contact in the U.S.: Edna Ogwangi

Land O'Lakes/Shoreview, MN phone: 651-494-5131 fax: 651-494-5144 e-mail: [email protected]

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. PROJECT OVERVIEW ...................................................................................... 1 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................. 2 3. NARRATIVE ........................................................................................................ 4

3.1 General Project Environment …………………………………………………….............4 3.2 Strategic Objective 1:

Dairy sector stakeholders directing improved sector competitiveness…………………5

3.3 Strategic Objective 2: Rwandan Milk and Dairy Products Competitive in East African Market……….…. 8

3.4 Strategic Objective 3: PLWHAs, OVCs and CHHs engaged in dairy related IGAs………………………..….12

3.5 Strategic Objective 4: Dairy Producers in Nyagatare region aware of HIV/AIDs prevention practices...…21

3.6 Summary Tables from work plan ……………………………………………………….. 22 4. UPCOMING ACTIVITIES ............................................................................... 28

Attachment A: Acronyms ……………………………………………………………. 29

Attachment B: Kiosk Consumer Survey Summary ......................................………...32 Attachment C: Recommendations on Milk Quality…………………………..……. 29

Attachment D: Milk Pricing Incentives and Processing ....…………………..……. 38

Attachment E: Potential Use of Milk by Processors ..........…………………..……. 54

Attachment F: potential dairy IGA for PLWHA Assn …………….…………….... 57

Attachment G: Zero Grazing Summary for 3-cow herd ..……………………...…. 61

Attachment H: Evaluation of IGA potential in cow dairying .……………………. 63

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 1 Land O’Lakes, Inc

1. PROJECT OVERVIEW The Land O’Lakes consortium is committed to successful project implementation and achievement of its strategic goal to expand dairy sector-related economic opportunities and improve well-being in rural areas by increasing the competitiveness of the Rwanda dairy sector. To achieve this goal, Land O’Lakes shall target increasing the efficient and profitable flow of quality milk and dairy products and related inputs and services through the dairy value chain and will integrate people living with HIV\AIDs (PLWHA) and orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) into dairy-related income-generating activities. As a result, the Rwandan dairy industry will be better able to compete in local and export markets, and vulnerable populations will have increased access to economic opportunities. Land O’Lakes has carefully chosen an array of partners and collaborators to assist in this program. Proposed sub recipients are:

CHF International, a U.S.-based organization, having worked in more than 100 countries worldwide to be a catalyst for long-lasting positive change in low- and moderate- income communities around the world, is currently implementing the Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization Program (CHAMP) in Rwanda, a four-year, 40-million dollar USAID/PEPFAR-funded program focused on HIV/AIDS prevention.

J.E. Austin Associates, Inc., a U.S.-based consulting firm, has been recognized as an industry leader in private sector development, value chains and competitiveness in sub-Saharan Africa, including Rwanda.

ABS-TCM Ltd, a U.S. technical services firm, has been recognized as an organization that provides private, market-linked dairy genetics services, delivery systems and dairy-oriented BDS strategies that have been developed by ABS TCM in Kenya (and WWS in Uganda and Kenya) and are highly appropriate to and promising for the Rwandan dairy sector. Land O’Lakes’ strategy for promoting growth and reducing poverty in Rwanda is to utilize a market-driven, value-chain, low-subsidy approach to dairy sector development, placing greater emphasis on the development of local partners (private, public and NGO) to provide technical services, build the capacity of local BDS providers and consultants, and strengthen/expand markets for productivity-enhancing inputs and services. The sustainability of the UDC program will come through the development of these local partners to the point where they can continue to provide key services and inputs required to further increase dairy sector competitiveness, reduce poverty and improve the well-being of communities and vulnerable groups. Sustainability will also be enhanced through the development of sustainable businesses and business linkages all along the value chain. By the end of the project, the services of Land O’Lakes and consortium partners will no longer be required as dairy farmers, cooperatives, dairy processors and commercial input and service providers assisted by the project will be engaged in profitable enterprises and can access and afford business, financial and technical services from local providers. The Dairy Industry Competitiveness Task Force, made up of public and private sector stakeholders, shall continue to as a vehicle and forum for policy dialogue and advocacy.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 2 Land O’Lakes, Inc

2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The USAID Dairy Competitiveness project has moved beyond talking about milk quality and IGAs to moving down the road map toward improving the milk supply and developing IGAs within PLWHA associations. This, in turn, has inspired Ministries to undertake new studies to help formulate new policies. This summary only touches on the main points. The narrative and attachments describe the progress in greater detail.

Milk quality and pricing issues reviewed and recommendations made to ameliorate the milk supply. Three veterans of the dairy industry assessed and laid out a road map to improve the milk supply. The veteran, former head of Minnesota’s Dairy Division, laid out a path with critical control points, affordable tests and potential personnel from the sectors to carry out plant and farm inspections. This will involve a major shift of the current inspection paradigm. The major obstacle is lack of personnel to carry out inspections on the thousands of small businesses and farms. The path will involves RBS, RARDA and local sector inspectors and veterinarians. Discussions will be started in January. The other two veterans from Land O’Lakes (a former vice president and a plant manager) tackled the related issues of milk pricing and processing potential. They helped advance the argument for differentiating milk price based on quality factors. Most commercial processors and some kiosk owners are now convinced but need an independent lab capable of furnishing unbiased, reliable test results. All agree the basis for differentiation of milk prices hinges on establishing a national laboratory. And the secret to product development hinges on an improved milk supply. To this end, the project is working with NGOs to find funding and training programs for lab operators. To date, an alliance of NGOs and private sector companies have applied for a half million dollars in funding from the DGA program matched by private and government investment. HIDA (capacity building agency of the government) is offering to finance two young people to the states for interning in US labs. The project is assisting them to find hosts. Once milk can be tested regularly, dairies will be able to develop streams of different quality milk and convert it to the most appropriate products. The current milk supply precludes export because of COMESA standards. Dairy operators have shifted from their initial disbelief to believing they can improve their current products by improving the milk supply.

The Competitiveness Task Force (CTF) moves to the next level. Working groups established within the CTF have been engaged in discussions on milk quality. As the project has shared data collected on milk throughout the dairy chain, some farmers participated in a trial to prove quality milk could be produced on rustic farms. The results came back with <300,000 CFU/ml if total bacteria. Now processors are talking about it, whereas a few months ago they largely dismissed these basic quality standards. The CTF found a new ally in the Minister of Finance who was contacted by the CEO of Tri-star holding company soliciting his support for a “National Dairy Initiative” using the CTF started by Land O’Lakes as the foundation. The ultimate goal will be to develop a National Dairy Board. The CTF held its last meeting of 2008 focusing on getting information out on a host of studies conducted over the past year and some that are in progress. This again, generated a lot of discussion and the project is in the process of collecting their final reports and archiving them on a CD or web for all to share.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 3 Land O’Lakes, Inc

Work with PLWHA associations. All three partners (CHF, ABSTCM and Land O’Lakes) have been active with PLWHA associations this past quarter. Land O’Lakes brought in two specialists, one in agribusiness management and the other in coop development, to work with the CHF and ABSTCM teams. They developed a prototype dairy IGA consisting of a 3-cow dairy that would cash flow. They did this while meeting with each of the 20 PLWHA associations with subsequent farm visits. Five associations were identified as having the greatest potential to develop IGAs with another five for the second phase. They laid out a series of steps to follow to launch the IGAs. CHF/CHAMP has hired Cooperative Support Officers (CFOs) and is developing their capacity to offer support to PLWHA associations as they transition from associations to coops. Several workshops were held this quarter and the CFOs are in place. They participated along with the ABSTCM team in the Land O’Lakes IGA assessment. ABSTCM launched a series of workshops for trainers from PLWHA associations, sectors and districts on a host of topics ranging from cattle management to record keeping. Several workshops were also conducted at the association level. The top order of business for next quarter will be for all partners to focus on helping PLWHAs set up IGAs.

Kiosk Consumer survey completed. Over 1800 consumers were surveyed in kiosks throughout the three districts of Kigali City to develop a profile of people that account for 90% of milk sales in Kigali. The three main products are raw, boiled and fermented milk. It describes a varied and vibrant market that is able to efficiently distribute milk within 24 hours of milk to consumers. It has opened the door to larger discussions on how best to regulate this sector and help it grow rather than regulate it out of existence.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 4 Land O’Lakes, Inc

3. NARRATIVE

3.1. General Project Environment The project environment continues to evolve. Surveys and studies have captured the imagination of both the government and industry stakeholders. Experts brought in by Land O’Lakes confirmed that improving the milk supply is the key to developing the industry and conversely, without it, little can be done in terms of exports or new products. The 48 hour milk market (milk kiosks) is starting to be recognized as the most significant part of the value chain, accounting for over 90% of sales. This carries many consequences for regulatory agencies that up to now had basically closed them upon inspection rather than develop appropriate inspection procedures. This sector provides safe, low-cost dairy products to a sector of population that cannot afford processed products. The Eastern Dairy Plant in Nyagatare has finally opened its doors and taken a few tentative steps in processing fresh pasteurized milk. However, concern is growing among processors that they may be dealing with shallow market because of price. What is becoming clear is that this is not a simple question of developing a new market but accurately reading the market that actually exists. Processors and to a lesser degree kiosk owners are becoming concerned with the quality of their milk supply. They are becoming willing to invest in and use a national lab, and once that is started, to develop a new milk pricing scheme based on quality and components. The RBS and RARDA are starting rethink their inspection procedures to accommodate realistic and affordable on farm and kiosk inspections. The project is in the center of these discussions that were initiated as result of new data generated by the project. The project is also finding traction in the PLWHA associations after giving up the upper reaches of the dairy chain to EADD in Nyagatare and Gatsibo. As this situation continues to evolve, the project should be on the lookout for expanding the program to other milk sheds. Gicumbi has consistently participated in the task force and is one of the largest milk sheds in Rwanda, after Nyagatare and Gisenyi, according to a recent CAPMER study. A concept paper was submitted to USAID to increase activities subsequent spending over a 3 ½ year period as opposed to five. If that is accepted, it should reflect this new environment in its IRs and activities. The SOs would stay constant.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 5 Land O’Lakes, Inc

3.2. Strategic Objective 1: Dairy sector stakeholders directing improved sector competitiveness Studies and consultancies: UDCP has changed the perception of the dairy industry through the series of surveys it conducted. In addition, a host of value chain studies have been conducted by CAPMER, MINAGRI, and EADD. To date, the project has surveyed: 745 milk samples taken throughout the dairy value chain 1549 milk vendors (informal market) 1200 farmers in Nyagatare and Gatsibo districts 1837 consumers in milk kiosks The data gathered is being shared with other institutions conducting studies and has found its way into the national dialogue on industry issues. The milk kiosk consumer survey in the “informal milk market” was conducted by Dr. Lucie Steinkamp this quarter. Excerpts from the 52 page report are included in Attachment B. Milk kiosks are fairly new in Rwanda: they developed after the war, with the reconstitution and development of the dairy herds starting mid to end 1990's. These kiosks fulfill two functions:

• provide a fast daily distribution of the milk coming from farms and milk collection centers in the surroundings of Kigali and up country comprising over 90% of the milk supply of the capital city;

• serve milk in individual servings at lunchtime (especially for the fermented milk) and along the business day to the workers in Kigali.

Forty three kiosks were selected from the UDCP database in the three districts of Kigali City. In general, most kiosks sell boiled milk and fermented milk, often consumed on the spot, but not all sell raw milk. Some of the more interesting observations include:

• The milk kiosk plays a critical role in milk distribution to households in Kigali o 90% of take-out sales of milk are less than 8 liters presumably for households o Women tend to be the buyers of small quantities whereas men buy in larger quantities,

presumably for resale. o Prices ranged from 130 – 350 RWF/liter, indicating significant price differentiation

taking place presumably on quality (organoleptic). • Milk bars (kiosks selling boiled and fermented milk in individual portions of .5 liters) represent

a value added product. A sophisticated system of distribution is in place. • Only 12% of kiosk customers buy packaged, pasteurized milk from supermarkets that sells at

double the price. • 79% of kiosk customers do not own a refrigerator and purchase fresh milk daily. • Lack of money is the most frequently cited reason for not purchasing milk at certain times of the

month, not availability. • Income level (disposable income) appears to be the most significant factor determining whether

customers purchase processed dairy products such as cheese, butter, powder milk, set yogurt or ice cream.

This survey has major implications on the domestic market, breaking some of the popular myths of the dairy market in Rwanda. First, 90% of the milk flows through this market. Processed products will have a very difficult time competing since fixed costs double the price of the product and place it out of range of most consumers. Closing the kiosks in order to force more milk through processing plants is commonly proposed. This will not necessarily make the milk supply safer and more importantly, place

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 6 Land O’Lakes, Inc

milk out of range of the majority of most consumers. The processed products market will more likely grow more as a function of the economy and expendable income than a function of new products and advertising. Second, the “informal sector” should be given the respect that is due. Kiosk owners appear to be rather independent and vary greatly in business objectives. Some own farms, and the kiosk is an outlet for their own milk. Others are wholesalers. Some have milk bars. And so on. The one common fate they will all certainly face is pressure for inspection. If they organize, they can be part of the process. There is little capacity to inspect the kiosks at the moment. However, sectors have personnel that follow the businesses. With a bit of training, they could become an arm of either RBS or RARDA. Finally, attention should be given to improve hygiene and practices in the kiosks, and to improve their products. This will be the focus of the project over the coming months. Milk Quality Monitoring Consultancy In the wake of new information on milk quality and observations on the inconsistency of inspection generated by the project, Dr. William Coleman, former head of Dairy Division for the State of Minnesota (14 years) was brought in to confirm findings and make recommendations for future action to improve the milk supply. This included the state inspection service. He was instrumental in the development of enforceable and affordable standards in Minnesota. Excerpts from his report are included in Attachment C. Dr. Coleman literally walked through the value chain and defined what each stakeholder could do at each stage to maintain milk quality. He identified the following critical control points and tests along the dairy value and chain and suggests who should be responsible.

Critical control points for raw milk quality testing Location Test(s) Agency Farm Temperature (bulk tank), water quality RARDA/Sector Vets Transporter Temperature RARDA/RBS Collection Center Segregation or rejection screening tests

(Resazurin, alcohol, lactometer, starch, temp, antibiotics, sediment, somatic cell count)

RARDA oversight/ MCC conducting tests

Receiving plants (processors)

Verification of screening tests as needed (as in MCC) Sampling for payment (bacteria, somatic cell and components)

RBS oversight/ Plants screen/ Independent lab for testing

Shops and vendors Routine screening sampling and payment (temp, lactometer, etc. as needed by vendor)

RBS oversight/ sector inspector for sampling/ independent lab for testing

He stated that the precursor and foundation of an effective inspection regime is an independent, high volume laboratory at least capable of testing for bacteria, somatic cells and components. As cited above, the current screening tests may capture reject level milk, but is not adequate to improve the quality to levels needed for manufacturing practice.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 7 Land O’Lakes, Inc

One potential practice that could be employed in areas where it is virtually impossible to deliver milk in a timely manner to a point of sale or cooling center is the use of lactoperoxidase to preserve raw milk. When treated within 2 hours of milking, this system can hold bacteria in check for 8-12 hours, depending on the temperature. The two disadvantages are encouraging minimal hygienic practices on the farm and exclusion of treated milk from international trade. Some thought should be given before adapting this method wholesale. These recommendations are being discussed with RBS and RARDA to develop a workable inspection system. Dividing the inspection between agencies and bringing in sector level people is a new concept that may require some time since three ministries are involved. This is a good road map for the milk quality initiative of the project.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 8 Land O’Lakes, Inc

3.3. Strategic Objective 2: Rwandan Milk and Dairy Products Competitive in East African Market

Land O’Lakes brought in two consultants as team to work on milk pricing and potential competitive advantage brought about by an improved milk supply. In the case of the Rwanda, improved milk quality is not just a question of offering better products on the market but goes to the fundamental question of whether it is feasible to use the milk for manufacturing. Paul Christ, retired Vice President of Land O’Lakes, was in charge of milk pricing policy and a dairy economist for over 30 years. Dave Peters, a 20 year veteran in plant management, developed a pricing scheme in the Land O’Lakes plant in Poland that improved milk quality on small farms in a rustic environment. In the short time they were here, they were able to propose some solutions for milk pricing and potential uses for the existing milk supply. Perhaps most importantly, they advanced the argument for price differentiation among key industry officials. Excerpts of their reports and presentations are found in Attachments D and E. Three fundamental observations formed the base for their recommendations.

The quality of milk in Rwanda will not improve unless there are incentives to do so. At present, the only incentive to sell quality milk is the fear of rejection. Even this is not adequate, as a milk seller can find alternative outlets for bad milk.

Incentives for improving the quality of milk can take the form of reward or punishment. Reward could take the form of a price premium for quality milk and public recognition of good quality performance. Punishment could take the form of a price discount for lower quality milk or prohibition from selling milk in the market.

The practice of paying for milk by volume (Rwf per liter) only reflects part of the economic value of milk. It does not reflect variation in the nutritional content of milk from different sources, nor does it reflect the potential difference in yields of manufactured dairy products.

The following recommendations were made related to developing a milk pricing system. (Greater detail in Attachment D)

Establish an independent central laboratory to perform quality and composition tests on milk from all sources in Rwanda. (forming the basis for pricing milk)

Set up a milk sampling system for determining milk quality and composition at each level where a financial transaction takes place, or milk from one source is commingled with milk from other sources.

Organize one or more dairy industry associations. Possible associations include commercial milk processors, milk collection centers and/or dairy farmer cooperators and dairy kiosk operators.

Adopt a milk classification system that differentiates milk by quality. Reject substandard milk. Pay a premium for high quality milk and impose a penalty of poor quality milk. Adopt a milk quality recognition program. Stop paying for milk by volume, and start paying for milk solids.

After a walk-about of the value chain, the following key observations were made at the farm and MCC level. (More details in Attachment D and E).

It is possible to collect and transport milk from small farmers and have milk < 300,000 bacteria Clean potable water is a must (or water boiled or treated with chlorine). Containers with tight fitting lids are a must. Bulk tanks must be used as designed. Collection stations must be properly designed. Most farmers are too far from the plant or collection station to participate in a collection and

distribution system based on 2 hr delivery and 2 hr cooling.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 9 Land O’Lakes, Inc

A lactoperoxidase system of milk preservation should be at least considered for a single processor with milk from small farmers.

After visiting existing dairy plants and milk vendors and reviewing existing documents the following observations were made on the milk market (Attachment D):

The estimated 2008 production of 170 million L is divided between the rural market (76%) and the urban market (24%). The rural market is home consumption and sales to village neighbors, while urban markets are primarily retail consumers and home consumption in the cities. Kigali is the largest city with 1 million residents and consumes over half of the urban-marketed milk and most of the imported products. The rest goes to the other large cities.

The average per capita consumption of dairy products in Rwanda was estimated in 2007 at 15.9 L/yr

per person. The urban market was higher at 21.0 L / yr per person versus 14.6 L in the rural areas. Milk consumption is nearly always higher in cities where upper and middle class citizens have access to more variety and safer dairy products.

Of the current 120,000 L per day that is coming to the urban markets, only 6000 L goes through the

three processing plants. The balance of 114,000 L is processed at milk kiosks using kitchen-type boiling and pasteurizing techniques. 62% is then cooled in on-premise bulk cooling tanks to 4C and sold either by the glass in the retail area, or sold for home consumption to walkup buyers with their own containers or 1.0L plastic bags. The milk is almost always boiled again at home; and then consumed right away by children, or made into cheese or yogurt.

The milk kiosks are well entrenched in the urban market and provide a generally safe and regular

supply of pasteurized milk into urban homes at a very reasonable price – less than half the cost of milk in half liter gable-top cartons from the processing plants. Secondly, they provide 500 ml of fermented milk or pasteurized milk by the glass that is consumed on premise, primarily for breakfast and lunch at 250 RWF. The peak consumption is between 11 AM and 2 PM when thousands of workers (office and retail clerks, taxi drivers, construction workers, etc.) buy the milk plus a doughnut for 350 RWF. This is a healthy and reasonably priced breakfast or lunch.

Over 1500 kiosks exist in Kigali alone. Many are in need of better equipment, clean water and

refrigerated storage. At least 20% need to improve or face closure in order to guarantee food safety to the public. However, this is simply a matter of licensing, training and regular inspection.

In no way should the government close all of these kiosks to force the milk through the plants. The

milk quality is so poor that the product would not run through the plate HTST equipment without constant plugging. The shelf life would be no more than 2-3 days with much of the product being returned from retailers for spoilage. It is better to have this milk boiled at the kiosks and consumed the same day (or in the worst case the next day). Even safer than pasteurized milk is the fermented milk that has a low pH to combat the growth of any bacteria that may contaminate the product after boiling. As the milk quality improves and people have more spendable income, they will gradually purchase more products produced in the processing plants because of longer shelf lives and more convenient packaging.

Once the milk supply starts to improve, there will be a period where milk should be sorted by

processors and made into a variety of dairy products. First class milk (<300,000 /ml) should be used for UHT milk, premium yogurt and cheeses. Second class milk will be used for most everyday products – cream, butter, milk bars, hard cheeses (like Gouda and Edam), and pasteurized milk and

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 10 Land O’Lakes, Inc

yogurts. Finally, 3rd class milk could be used for pizza cheeses, fresh cheese as an ingredient for processed cheese and fermented milk products.

It is suggested that one central plant could be used to make cheese and deal with all whey related

issues. All the dairy plants that can sort milk could jointly own it. The cheese could then be returned to the processor shareholders to be marketed under a number of brand names in the urban market or for export. Inyange is considering closing the old plant when the new plant opened. The plant has the basic processing equipment already and refrigerated storage areas for ripening. Only cheese vats and brining equipment need to be added to make cheese.

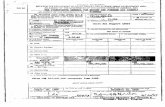

The following slide illustrates how milk could be utilized according to quality.

[1] Dairy Sector Competitiveness

Program

2 million ml – 10 million/ml< 1 million/ml

Sort milk by quality

<300,000/ml

UHT milk

Yogurt

Specialty cheeses

Edam

Gouda

Pizza Topping

Fermented milk

Milk bars

Yogurt

Past. milks

Hard cheeses Processedcheese

The three veteran consultants confirmed that improving the quality of the milk supply is a prerequisite for further development of processed products. Although the solutions are relatively simple, they all agreed it is an enormous undertaking to change habits that have taken root. The project has been active dialoguing with manufacturers and kiosk owners to develop a new pricing system and it is bearing fruit. The CEO of Tri-Star (the holding company behind the largest dairy in Rwanda) has become convinced this is a national priority and has taken the issue to the Minister of Finance who, in turn, has as agreed to lend his good offices to support a “National Dairy Initiative” based on the Competitive Task Force founded by the project. In addition, the USAID mission lent its support to developing a national dairy testing lab through the DGA program. The project is working with NGOs to apply for $500,000 to establish the lab. In the process private and government funds are being leveraged in approximately equal amount for the lab.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 11 Land O’Lakes, Inc

The project now has a relatively well defined road map for developing the industry. The work plan needs to be revisited in light of this information and adjustments made. The Competitiveness Task Force (CTF) The final meeting of the CTF focused on ferreting out studies conducted in the dairy value chain this past year. Most studies were behind schedule, but the final agenda included the following:

Activity Responsible/Presenter Main conclusions from Dairy Competitiveness Working Groups Meetings

Mrs. Consolée MUKAMURIGO

Preliminary results of Dairy sector related Studies conducted by CAPMER (domestic market, transportation, collection centers, potential for additional pasteurization units, UHT milk processing)

Mr. John NDIKUWERA (CAPMER)

Key findings of studies conducted by Land O’Lakes

Roger Steinkamp, Paul Christ, Dave Peters and Lucie Steinkamp

Key findings of study conducted by Send a Cow Rwanda (viability of one cow dairies)

Brian Legg

Key findings of study conducted by OTF Rwanda (export potential)

OTF Presenter

Key findings presentation of study conducted by the Eastern African Dairy Development Project in Rwanda (value chain overview)

Emmanuel MUNYANDINDA and NDAVI Muia

Presentation of the 4th ESADA Conference held in Nairobi(August 6-8 /08)

Gloriose (MINAGRI/PADEBEL)

As the final reports become available, UDC is planning to collect them and disseminate a CD with stakeholders. In addition, reports can be uploaded to the websites and/or linked to host organizations if they are already up. At the end of the meeting, volunteers were solicited to form a working group to establish the National Dairy Board, the current rendition of the National Dairy Initiative. With the Ministry of Finance backing the initiative, there is a greater chance of significant involvement of MINAGRI and MINICOM. In addition kiosk owners and milk haulers are now considered key players due to discussions held with the project.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 12 Land O’Lakes, Inc

Strategic Objective 3: PLWHAs, OVCs and CHHs engaged in dairy related IGAs Gene Kunst and Ariong Abbey were brought in this quarter to enhance efforts to get dairy related IGAs identified and started among the 20 most viable PLWHA associations previously identified. Gene comes from agribusiness management program at Riverland Community College with experience in several countries dealing with business start-ups and management. Ariong, a Ugandan, brings his knowledge of and experience in cooperative development in many countries beside Uganda. CHF continued building capacity of Cooperative Support Officers, recently hired and placed at the district level. And ABS launched a broad based training program in cattle management, inviting volunteers from all 20 PLWHA associations and, in many cases, sectors and/or districts. Dairy related IGAs: (Attachments F-H) The two consultants in collaboration with CHF and ABS field staff visited each of the 20 PLWHA associations meeting with members and visiting individual farms. CHF/CHAMP introduced the Land O’Lakes consultants to the local authorities in Gatsibo and Nyagatare to explain the purpose of the consultants work. During the course of interviews, the following picture emerged on the minimum requirement for a bankable IGA based on milk cows.

The Model Dairy Unit• 3 cows in a zero graze facility• 2 cross bred cows & 1 exotic cow • Facility will cost 385,800• Cows will cost 2,000,000• Equipment 70,000• Operating Costs

– Breeding 5,000– Vaccination 1,200– Insects and worming 1,000– Total 7,200

Total Investment 2,469,200 RF

Repayment Capacity?

• Milk Income– 7,700 liters of milk @ 140/L = 1,078,000/ year

• Milk income = 2,953/day• Commitments to loan= 2,344/day

– (2,000,000 @16% for 36 months)• Commitments to annual costs = 20/day• What is reasonable?

– I would like to see 2,930/day of income

Attachment G compares the typical traditional breed with “improved” breeds vs. the 3 cow model developed. In addition, they noted the following:

• Critical needs for a dairy to generate income were identified as Infrastructure, Water, Knowledge, Leadership, Innovation, Access to money and Cattle breeds with the capacity to milk >10 L/day.

• 3 cows zero graze model dairy unit with requiring RWF 2.7m/= investment • 16% average membership in associations ready for the model identified • Need for cost effective appropriate technologies

By the end of their consultancies they outlined the following next steps (details in Attachment F):

1. Organize and conduct educational sessions aimed at making the association membership appreciate and understand the 3 cow model unit at the association level. Concurrently, on farm statistical data should be collected from members who are already engaged in livestock/dairy activities relating to number of cattle, ages, breeds, State of Kraal, milk production etc. This

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 13 Land O’Lakes, Inc

information will be crucial at the financing stage to determine who qualifies and to what extent. CHAMP/CHF should be positioned to conduct the initial sessions and ABS to provide close support in obtaining on farm data.

2. Form a “sectoral committee” of all members engaged in livestock/dairy activities from within the

association(s). This committee will be the nucleus to form a cooperative in line with the Government directive on cooperatives. Other members who are not yet engaged in this activity and even those outside the association should be free to register into the cooperative. The cooperative will thus emerge from within the association.

Training in basic cooperative development principles, values and benefits, democratic governance, transparent management of shareholder resources and farm record keeping should be conducted. CHAMP/CHF district level cooperative development officers and/or sub-contracted Community Service Organizations will deliver this training.

3. The implementing partners should follow up with the relevant financial institutions/schemes. The

following financial alternatives were identified;

Of the two financial institutions considered, Banque Populaire Du Rwanda S.A. (BPR) was identified as the most suitable in terms of flexibility, reach and loan conditions. Their Security guarantee funds scheme was found to be particularly appropriate. The loan interest at 13% is perhaps the best bargain and its guarantee funds attract up to 7% interest. The development organization enters into an MOU with the Bank. The Bank separately loans the client finances and recovers it. The advantage is that repaid funds will be available to other clients.

There are existing guarantee facilities for various schemes in some financial institutions. It would be helpful to explore them and zero down on those found appropriate for funding.

The individual and group guarantee loans options should also be discussed with the Bank with a view to getting those target clients with tangible collateral to access these facilities

There are some farmers who are keeping substantial herds of traditional Ankole cattle. Some of them are interested in converting part of their herds to cross breeds and/or exotic cattle. It would therefore be prudent to identify these farmers and also encourage others start up the zero grazing units. Conversion is currently four (4) Ankole cows to one (1) cross bred heifer.

Where possible and funds permitting, some grants maybe given.

4. Presently, animal management is very poor at farm level. Dairy cattle management should therefore be a top priority... The approach and methodology of training on these skills should be community oriented and as practical as possible. Training sessions should be conducted at association venues and one model pilot demonstration farm established (by improving a fairly good existing one) in each association. ABS and/or CSO’s will provide technical training ...

5. A mini-milk collection centre (MCC) with a cooling capacity of up to 500 liters would ideally be

set up to absorb the increased milk production from the cooperative. However, funding not permitting, the cooperative will require a very reliable transport system to collect and haul milk from farms and sprint it fresh to the nearest UDAMACO MCC. Land O’Lakes should conduct an investment costs, cost-benefit and break-even analysis for these two scenarios- the MCC and transport system.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 14 Land O’Lakes, Inc

6. ABS should identify and build the capacity of struggling small shop owners within the locality to stock and sell input supplies such as veterinary drugs, salt licks, sprayers etc. in instances where they are in short supply or are too distant to the target clients.

The UDC partners will meet as soon as everyone returns to follow-on with these activities.

Capacity building:

Cooperative Support Officers (CSOs) Basic cooperative development: (CHF/CHAMP) The 2 CSOs hired by CHAMP in the previous quarter to support the 20 PLWHA associations targeted in the 2 districts participated in two Training of Trainers workshops The curriculum is based on adult experiential learning and will aid the support officers to build the capacity of the 20 associations to function as vibrant institutions that will promote enterprise development for their members; The main objectives of this training were:

• To orient the CSOs in CHAMP strategies and objectives, particularly the Economic Opportunities Strategy.

• To build the capacity of the CSOs to be able to effectively facilitate the process of cooperative transformation and development.

The curriculum consisted of the following modules;

1. Organisation development 2. Introduction to business planning 3. Governance and Bye Laws 4. The Importance of group roles and responsibilities 5. Financial Management 6. Goal setting 7. Communications 8. Operational Planning

It is expected that in the next quarter the CSOs will roll out the training process for the 20 Association in Nyagatare and Gatsibo.

Finance and market literacy training (CHF/CHAMP) The objectives of the training were:

To build the capacity of CSOs to train and mentor CHAMP supported cooperatives to identify and effectively respond to viable market opportunities.

Introduce participants to basics finance To enhance the understanding of trainees on conditions and eligibility criteria for cooperatives to

access to credit. Sharing of experiences among Cooperatives Support Officers.

The Modules of this curriculum include

1. Marketing Basics 2. Enterprise Spirit 3. Participatory tools for enterprise selection and Planning 4. Market Opportunity Identification

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 15 Land O’Lakes, Inc

5. Enterprise Selection 6. Enterprise Planning and Development 7. Financial Management

Sixteen CSOs participated in both trainings including two CSOs from Gatsibo and Nyagatare districts. The CSOs will begin building the capacity of the 20 associations to identify and develop market linkages for dairy related Income generating activities. Training of Trainers Cattle Management Course (ABSTCM) In collaboration with CHF/CHAMP, ABSTCM organized two, three-day training courses for 55 trainers in November. They included 26 trainers from 13 associations in Nyagatare district, 15 trainers from 7 associations in Gatsibo district and 14 representatives from 7 sectors, in which the 20 associations are located, in Nyagatare and Gatsibo districts were trained Training materials were prepared and the notes translated into Kinyarwanda. These notes are still being edited and will be bound into a training manual. The topics covered included

breed selection, feeding for improved milk production, legume and pasture development and role in NRM, milking hygiene and milk quality, animal handling and handling facilities, disease control, reproductive management including heat detection, milk marketing, records, use of manure for biogas.

In addition, practicals on body condition scoring and dairy characteristics were conducted at Umutara Polytechnic University dairy. The participants then visited the ISAR legume and pasture plots where they were exposed to the range of legume and pasture varieties available and how they can be established and managed. Other practicals included determining dosage rates; administering antibiotics, anthelmintics and acaricides; and restraining cattle. This was possible through the MOU that ABSTCM has with ISAR. When the Gatsibo group was trained, the Director of the ISAR Nyagatare Station attended the session and assured the participants that his Station would be willing to assist them in a variety of ways including sourcing materials for pasture development. The Gatsibo group visited the UDAMACO dairy plant and the biogas unit in Rwempasha. The Nyagatare group could not visit these places because on the day of the intended visit there was a political demonstration in Nyagatare; as a consequence, all shops and institutions had to be closed. The CDLS (District HIV and AIDS Coordination Organization) director opened and closed the training course for Nyagatare on behalf of the Nyagatare District Office while the RRP+ president for Gatsibo opened and closed the training course for the Gatsibo group on behalf of the Gatsibo District Office. The CHF CSO addressed the Nyagatare participants. Training was largely conducted and facilitated by the ABS team; other resource persons were from ISAR, Umutara University, ABS EADDP, UDAMACO (for Gatsibo group only), and RRP+. The UDAMACO manager spoke on milk marketing, the role of UDAMACO, and how interested farmers could join UDAMACO. He encouraged the participants to join the primary cooperatives of UDAMACO across the two districts of Nyagatare and Gatsibo.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 16 Land O’Lakes, Inc

At the end of the training, each participant was given 1 kg each of the legumes Mucuna pruriens (Mucuna) and Lablab purpureus (Lablab) seed. From subsequent visits, we observed that some of the participants have already planted the seeds. Follow-on courses are being planned for March 2009.

Visit to ISAR legume and grass plots with trainers from PLWHA associations in Nyagatare district.

Training on loading a syringe and calculation of dose rates

Practical on restraining cattle using the halter method

Milk technique and milk hygiene training with PLWHA associations

in Gatsibo and representatives from Sector offices in Gatsibo and Nyagatare districts

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 17 Land O’Lakes, Inc

Training at Association level One day training sessions were held at the association/community (clusters of associations) level on cattle management at Abamaranashavu Association in Rwempasha in collaboration with CHF/CHAMP. Similar courses were conducted at 2 other associations in Nyagatare district. The topics covered were more specific to the areas of interest of each association or clusters of associations. However, across associations, feeding of cattle, disease control, reproductive management and record keeping were covered. Theory was covered in the morning and in the afternoon practicals on, among other topics, administration of antibiotics, anthelmintics and acaricides were demonstrated. Each participant was given a handful of each of Mucuna and Lablab legumes.

Other activities conducted in the field:

Farm visits for pregnancy diagnosis and general improvement of cattle management (ABSTCM) The ABSTCM team visited 9 herds in 5 associations (5 Sectors), Abatonibimana (Rukomo Sector), Abamaranashavu (Rwimiyaga), Ihumure (Musheri), Inziranziza (Rwimiyaga), Rengerubuzima (Matimba), and Dukundane (Karangazi) for pregnancy diagnosis and assessment of reproductive and other problems. During 2 of the visits, we teamed-up with Umutara Veterinary Faculty members and students. These associations have been linked to the Umutara University Veterinary Faculty ambulatory service. The herds were assessed for pregnancy, body condition, disease control, milk production, calving interval, breeding method and dominant breeds. The data will continue being collected until all the associations are visited and as many herds as possible are visited. The emerging pattern is that most of herds do not keep records, for example, most did not know the exact dates when their cows had last calved. However, most could remember the month of calving. All the herds visited had Friesians and Friesian crosses. They use bulls for breeding while 1 herd had tried synchronization of oestrus and AI on 1 cow but the cow did not conceive. Pregnancy rate across the herds examined was less than 30% with close to 30% of these pregnant cows having been bought pregnant. The calving interval in pregnant cows was about 600 days. Few of the farmers and their herdsmen knew the correct signs of heat and interval between observed heats of 5 months were not uncommon. In general, most of the herds had cows with a body condition score of less than 3 (1-5 scale) and there were cases of cows in late pregnancy with a body condition score of less than 3 which would predispose them to peri-parturient disorders including retained placenta and metritis. Some cows were still not pregnant more than a year after calving. All the

Training at Abamaranashavu Association, Rwimiyaga

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 18 Land O’Lakes, Inc

herds did not have a disease control or herd health program. Most of the herds do not have restraining facilities; this has limited our herd visits to those with restraining or cattle handling facilities. It was apparent that the farmers managed their herds as they managed the indigenous Ankole cattle. The milk production for the Friesian and Friesian crosses ranged from 4 to 10 liters per day. It is clear that if milk production has to increase the farmers should improve the pregnancy rates in their herds and improve the general herd management, for example, feeding, disease control, record keeping and heat detection. The training program that has been initiated would help but there is need to link the farmers to an extension service. However, some farmers were using local veterinary workers but this service was not readily available, for example in Musheli and Matimba. Promotion of pregnancy diagnosis would assist farmers to be aware of the pregnancy status of their cows. Most of the farmers were disappointed to learn that a cow they thought was pregnant was not. The assumption was that once the cow had been bred she would then be pregnant. Failure to detect heat would also worsen the problem as the farmer would presume the cow pregnant when she does not show heat.

Assembling an ultrasonic scanner for use in pregnancy diagnosis

Pregnancy diagnosis of cattle of a member in Musheri

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 19 Land O’Lakes, Inc

Field trials on use of the feed additives Bovine One and First Arrival (ABSTCM) Farmers that have been recording milk production have been given Bovine One for testing. They had been left to record milk production for the response to Bovine One to be detected. Bovine One is a microbial and enzyme mixture that has the potential to increase milk production. The First Arrival that is claimed to increase growth rate and the health of calves has not yet been tested because of the difficulty of getting a batch of suitable calves that can allow for unbiased comparisons.

Biogas generator trials (ABSTCM)

ABSTCM held a meeting with Mr. Gerard Hendriksen, Technical Advisor, of the Biogas development program of the Rwanda Ministry of Infrastructure (MINFRA) concerning possible collaboration in biogas work. The MINFRA biogas program is installing the masonry permanent type of biogas units (6 m3 capacity) at a cost of around Rwf 450 000 (USD 800) to the beneficiary but a subsidy of Rwf 200 000 is paid by the MINIFRA. The MINFRA biogas program has agreed to extend their program to Nyagatare and Gatsibo through our program provided there are at least 10 interested clients to ensure economies of scale. The program has also offered to train 2 or 3 of service providers or members from our associations in the construction of the masonry type of biogas units. The ABSTCM team visited Kibungo where MINIFRA has a contractor who has been installing the masonry type biogas units. The units are made from local stones and other materials; only cement has to be imported. The units are capable of producing enough gas for cooking and lighting. MINIFRA is also demonstrating the Chinese fiberglass biogas generators but the generators may not be competitive at a landing cost of Rwf 850 000. MINIFRA also led us to the Kentank biogas unit which was said to have been tested in Kenya. It turned out that the biogas tank had not been tested. As a result, the ABSTCM Nairobi Office began testing the tanks. Our team was also given a Kentank biogas unit from Aquasan, Rwanda, to test. After installing the tank, gas production was very good but the tank cracked within 24 hours of fully loading the digester. The ABSTCM team in Nairobi also noted a similar weakness on the tanks they tested. The manufacturer is redesigning the tank to correct this weakness and others; ABSTCM has been promised a donation of the redesigned tanks for re-testing. Aquasan also has water harvesting tanks and equipment and is interested in supplying these tanks and equipment at negotiated rates. This is likely to be a good offer for members that are interested in collecting potable water. Aquasan can also provide advice on technologies for the production of potable water. This would help association members in their endeavor to produce clean milk.

The demonstration biogas units that were reported to have been producing low gas output eventually produced very high gas output; erstwhile, they were unable to produce high gas output because of a high carbon to nitrogen ratio. The ideal ratio ranges from 20:1 to 30:1. The ratio for the dung from cattle in the project area was estimated to be 40:1 to 50:1. The ratio of nitrogen was increased through the addition of urea, initially, 2 kg for the 2 m3 canvas type digester. The urea was mixed with 8 kg of corn meal to provide easily fermentable carbohydrates. Subsequently and after the visits to Kibungo, it was noted that the urea could be replaced by cattle urine. The urine can be mixed with dung at a ratio of 1:1 (w/w). This option is feasible if a farmer has a zero grazing unit with a furrow and receptacle for the collection of urine. The different biogas models have been publicized to all the PLWHA members at training courses and meetings. There is interest but some members claim that the cost of installing biogas is too high for them.

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 20 Land O’Lakes, Inc

Develop and promote opportunities for cooperatives to competitively link into markets. (CHF/CHAMP) In line with market linkages, CHF/CHAMP staffs with the Land O’Lakes consultants opened discussions with UDAMACO to assess the potential for market linkage between UDAMACO and CHAMP supported cooperatives. UDAMACO has a certain number of MCCs mostly in Nyagatare but few in Gastibo district and is willing to integrate CHAMP supported cooperatives in their milk selling system.

Identify financial institutions to provide finance support to CHAMP assisted cooperatives CHF/CHAMP organized meetings with Finance institutions (Banque Populaire de Nyagatare and Duterimbere MFI) to explore the existing finance opportunities, conditions and eligibility criteria to access to those opportunities. Both banks showed interest to work with assoc/cooperative members to provide loans for purchase of animals and other related dairy equipment. Together with CHF Microfinance technical support staff from Nairobi, CHF/CHAMP evaluated the Guarantee Fund (GF) proposal and additional information collected by Aquadev, both in terms of fit with the CHAMP-assisted cooperatives’ needs and Aquadev’s role in supporting the GF. To continue assessing the potential of integrating CHAMP assisted cooperatives into existing finance program, CHF/CHAMP held discussion with different finance providers such as Banque Rwandaise de Development(BRD), National Bank(BNR), Rural Sector Support Project(RSSP). A number of existing facilities to aid small scale resource producer’s especially agricultural producers exist in most of these institutions. CHF/CHAMP will work with the cooperatives to ensure that they meet the eligibility criteria in terms of their organizational and managerial capacity.

Other issues and events... Collaboration with EADDP partners including TNS, ABSTCM and ICRAF. The anticipated collaboration has been difficult to achieve because of divergent interests of our project and those of the EADDP. However, ABSTCM in EADDP conducted the training on milk hygiene and quality training in the courses on cattle management offered to trainers from PLWHA associations in Nyagatare and Gatsibo. A meeting was held with ICRAF to explore market opportunities for PLWHA associations producing legume tree seedlings as an income generating activity. ICRAF has left the sourcing of markets to the farmers. TNS presented its study at the CTF meeting. The ABSTCM team attended a meeting on harmonization of AI services, RARDA, ERAGIC and EADDP representatives were present. AI services will be available to all farmers at the same rates across institutions (projects, private, government etc.) – our association members can also benefit from this service. Linkages have been established with the AI Department at RARDA. ABSTCM has arranged for RARDA officers to visit Kenya for study tours and attendance of courses on genetic improvement of cattle. The RARDA director of the AI program has agreed to assist members in our associations through provision of AI services and training in collaboration with our team. ABSTCM team participated in the launch of the Oestrus Synchronization and AI program of EADDP. RARDA is providing the synchronization drugs that could also benefit the members in our associations who can afford to pay for AI services. The AI service will include the cost of the first and repeat inseminations, pregnancy diagnosis and uplifting of calving records for the creation of a national data base at RARDA. The total cost for these services has been set at Rwf 5000 (USD 9).

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report October-December 2008 21 Land O’Lakes, Inc

3.4. Strategic Objective 4: Dairy Producers in Nyagatare region aware of HIV/AIDs prevention practices In the last quarter, the BCC unit organized a national level training of trainers for 22 people (5 of which intervene in Ngagatare and Gatsibo), on HIV/AIDS prevention, VCT and PMTCT.

Rwanda Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 2008 22 Land O’Lakes, Inc

22

3.5. Summary tables The following tables summarize progress to date on the work plan.

Strategic Objective 1: Dairy sector stakeholders directing improved sector competitiveness

Intermediate Result 1.1: CTF addresses critical competitiveness issues indicated in the Competitiveness StudyIR Objective Activity Indicator Verification Schedule Current Status

1.1.1.1. Milk quality audit conducted at farmer, bulking point, processor/retail levels. (mini grant). RBS, RARDA, UDAMACO, associations, milk haulers as key partners analyze results

1 annual milk quality audit carried out in collaboration with RBS, RARDA and local government

Report on Milk quality audit describing total bacteria counts, somatic cell counts and composition at three points in the value chain

1518 milk vendors surveyed in the City of Kigali 745 milk samples analyzed along the dairy value chain 1200 farmers surveyed in Gatsibo and Nyagatare

1.1.1.2. Milk market survey to estimate potential and current demand of processed and raw milk in Rwanda. Including consumer preferences and purchasing power, by demographics (mini grant)

1 – domestic market survey Domestic market report CAPMER and EADD conducted studies 1800 consumers surveyed in kiosks

1.1.1.3. Best practices for maintaining milk quality from cow to consumer assessed and tested for improving and maintaining milk quality. (mini grant(s))

1 best practice study completed for farmers, MCCs, milk haulers, processors and retailers

List of recommended practices for each group

Farmer working group volunteers tested milk at the farm level using basic hygienic practices to prove it could be done. (Results from farm survey indicated the problem started on the farms.) EADD will be producing a quality milk manual for farmers.

1.1.1. Key studies conducted with active participation of stakeholders directly concerned with the study and in concert with the EADD project and GOR agencies.

1.1.1.4. Regional import/export dairy market study conducted to determine comparative competitive advantages in the region. (mini grant)

1 completed regional market study Regional dairy market report

June 08/ September 09

CAPMER will include this as part of their study. Milk survey results indicate current milk supply does not meet COMESA standards, precluding export

Intermediate Result 1.2: CTF proposes policy reform 1.2.1. CTF or subgroups

advocate policy reforms to key decision makers

1.2.1.1. CTF forms working group(s) to formulate policy recommendations on key issues identified in studies dairy industry

2 policy areas endorsed by key stakeholders affected by the policy

Report/white papers presented August 08 + Transfer of ownership of the task force is underway. The idea spread to three ministries and several organizations. The Minister of Finance is now coordinating the national dairy initiative that should lead to a national dairy board.

Rwanda Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 2008 23 Land O’Lakes, Inc

23

IR Objective Activity Indicator Verification Schedule Current Status

Intermediate Result 1.3: RARDA and/or RBS takes leadership role in support to dairy sector

1.3.1.1. RARDA participates in annual milk audit collecting and analyzing samples for bacteria, somatic cell, and components in collaboration with stakeholders.

Milk audit conducted on 250 samples from retailers, MCCs, and farms

Records and summary of audit results

July 08

.

1.3.1. RBS and/or RARDA develops quality testing framework in concert with CTF to monitor milk quality from the farm through MCCs, processing plants and retail outlets.

1.3.1.2. Continuous monitoring regime set up for retailers, processors and MCCs on a cost effective basis.

Regular testing of milk supply for clients (frequency TBD by clients )

Price list for tests established with list of clients

August 08 +

Expert in milk monitoring and enforcement made recommendations in November. Neither RARDA nor RBS has the human resources to adequately inspect the entire dairy chain. Discussions are underway to resolve this problem by involving sector level people in the inspection process.

1.3.2.1. Assess and address competencies of inspectors and/or plant technicians to conduct retail, processor, MCC and farm inspections.

Assessment of competencies and training needed.

Progress Reports July + 08

1.3.2.2. Study tour(s)/training course conducted in-house or at regional testing facilities.

2 workshops and/or study tours conducted

Certificates of completion of training

July – August 08

1.3.2. Increase capacity of the inspection, lab and standard department of RBS and/or RARDA

1.3.2.3. Conduct supplemental training of inspectors as needed to monitor milk supplies.

Numbers (TBD) of inspectors trained to carry out inspection regime

Workshop reports August + 08

Once a system is agreed upon, RBS and/or RARDA can develop a program for District/sector level inspectors.

Intermediate Result 1.4: Increased investment in the dairy sector

1.4.1. Increased investment in the dairy value chain in Rwanda

1.4.1.1. CTF identifies critical areas for investment in equipment and capital

Phase One - $1 million Report on investment in the dairy sector

Continuous through first two years

New funding is being sought for a national laboratory in combination with a DGA grant.

Rwanda Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 2008 24 Land O’Lakes, Inc

24

Strategic Objective 2: Rwandan Milk and Dairy Products Competitive in East African Market

Intermediate Result 2.1: Increase the volume of milk marketed from pilot MCCs that meets COMESA raw milk standards IR Objective Activity Indicator Verification Schedule Current Status

2.1.1. Improve the quality of milk delivered to MCCs and dairy plants/retailers in collaboration with EADD

2.1.1.1. Conduct study to identify and test best practices that have measurable impact on milk quality including bacteria and somatic cell counts

20% improvement in bacteria counts and SCC of milk delivered to MCC toward meeting COMESA standards

Test results from RBS or MCC September 08 +

Results of milk quality indicated substandard milk being used. That explains the quality issue commonly found in products. Three experts were brought in to develop a road map that includes appropriate tests, control points, and pricing schemes to encourage production of quality milk.

2.1.2. Increase milk sales from 2 pilot MCC centers by volume

2.1.2.1. Collaborate with milk haulers and dairy plants to increase sales through existing MCCs in collaboration with UDAMACO, and EADD especially during peak production season (November – May)

Increase daily sales of milk from MCCs to include all saleable milk produced (no saleable milk turned away at the centers)

MCC sales records July – May 09 Agreement reached with EADD and UDAMACO on two sites. One MCC has already started conversion to washable milk cans.

2.1.3.1. One processor and/or retailers agrees to price milk based on quality tests that lead to meeting COMESA standards

1 processor and group of retailers agree to offer price differentials based on quality measures

Price list and standards for payment

December 08

2.1.3.2. 2 pilot MCCs and/or groups of milk suppliers pilot quality driven incentive payments

2 pilot MCCs/supplier groups identified and baseline established

2.1.3. 2 Pilot MCCs and/or milk supplier groups adopt milk pricing that rewards milk meeting COMESA standards (in close collaboration with EADD and UDAMACO)

2.1.3.3. Set of improvements to make to improve milk quality in collaboration with UDAMACO and EADD

20% average improvement in each test not meeting COMESA standards over the baseline established in an annual milk audit

Test results procurement records from processor Also the annual milk audit

September 08 – June 09

Processors all recognize the problem and appear ready to attempt a new pricing structure once affordable testing is available. MCCs will most likely follow the lead of their clients but are unlikely to change their structure unilaterally.

Intermediate Result 2.2: Determine optimum utilization of processing capacities in cooperating plants 2.2.1. Determine constraints

to increased utilization of current plant capacity unique to each plant or product

2.2.1.1. At least two dairy plants develop a production schedule based on a local and/or regional market survey for products in which they have a competitive advantage

2 plants operating at optimum production levels as determined by the study

Production/sales records September + 08

Issues introduced to plant managers. There is a growing concern not only for a quality milk supply but also there is some evidence of a shallow domestic market. Evidence is mounting that the market for processed products commonly produced in the west are a niche market. More emphasis should be given to support of the traditional market.

Intermediate Result 2.3: Increase in volume and/or value of processed dairy products sold2.3.1.1. Describe customer profiles,

demographics and preferences for processed dairy products

2.3.1. Determine the potential domestic market for processed dairy products.

2.2.1.1. Assess market potential for each product based on competitive advantage and consumer profiles and preferences, combined with demographics. (consultant/mini-grant)

5% increase in total volume and value of processed dairy products according to market potential processing capacity indicated by the study.

Sales records July – September 09

Data emerging from the Kigali survey indicates a vibrant distribution system in what was once considered “informal” Kiosk owners are being approached to form a coop or association.

Rwanda Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 2008 25 Land O’Lakes, Inc

25

Intermediate Result 2.4: New dairy products test marketed

IR Objective Activity Indicator Verification Schedule Current Status 2.4.1.1. Conduct feasibility study for UHT,

powder milk, cheese and other dairy products for production for the local and/or regional markets. (mini-grant(s) to local institution or processor for new product feasibility study)

Feasibility study completed 1 new product introduced to the Rwandan and/or regional market within a year

- Study

- Gross sales on domestic and/or export markets

CAPMER Study to be completed in December 08 New product(s) introduced in

2.4.1. Minimum of one new Rwandan produced dairy product entering the market

2.4.1.2. Recommendations made on potential for new product(s) to management of respective firms.

CAPMER initiated study initiated to provide insights into new products. UDC will add recommendations matching products to milk quality. PROMACO in Nairobi is interested in setting up an outlet in Kigali, providing new cultures and equipment. UDC is facilitating and encouraging the move.

Rwanda Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 2008 26 Land O’Lakes, Inc

26

Strategic Objective 3: PLWHAs, OVCs and CHHs engaged in dairy related income generating activities

Intermediate Result 3.1: Increase in volume of milk sold by producer association with 20% or more PLWHA membership IR Objective Activity Indicator Verification Schedule Current Status

3.1.1. Increase in number of associations or PLWHA/ OVCs/CHHs delivering milk to MCCs or direct to retailers or processors.

3.1.1.1. Improve capacity to produce quality milk on the farm in collaboration with EADD

20% increase in liters of milk sold by PLWHA associations to MCCs or retailers over baseline

Reports at the milk collection centers + records from associations

April 09 Experts set out a road map for 5 + 5 associations that have potential for developing viable dairy IGAs.

Intermediate Result 3.2: Increase in household incomes for PLWHAs, CHHs from dairy-related income generating activities 3.2.1.1. Inventory resources of current PLWHA

associations and potential for providing product and/or services. Identify local leaders and deficiencies of current service providers.

62 PLWHA associations leaders that have been interviewed to identify current services

Baseline questionnaires + report June Completed

3.2.1. Increase involvement of PLWHA, OVC, their caregivers and associations in the dairy industry 3.2.1.2. Identify specific areas of intervention

and elaborate a work plan based on baseline findings.

1 work plan elaborated Work plan June 08 District coop development coordinators hired by CHAMP that will work closely with assns/coops Consultants evaluated the potential for IGAs in the 20 associations and ranked them according to potential. Model dairy IGA developed to kick off the program.

3.2.1.3. Determine issues confronting female headed households, PLWHA and OVCs participating in the dairy industry.

160 female headed household, PLWHAs and OVC participating in dairy related activities and associations/ cooperatives

Reports disaggregated by gender April 09

3.2.2.1. Assess which MFIs can handle funds for animals or other economic activities in associations

2 local MFIs identified to collaborate with associations

Reports June 08 Completed

3.2.2.2. Build a credit process to channel the money for cows and activities through MFIs and link to associations

160 dairy IGA (projects) funded by local 2 local MFIs

Report of activities and/or MoUs signed

April 09 Products under negotiation with MFIs, Bank Populaire and Duterimbere new models formulated by consultants

3.2.2. Increase in number of PLWHA/OVC associations or members receiving financing, BDS and/or marketing assistance services in collaboration/ coordination with EADD activities in Nyagatare/Gatsibo zone.

3.2.2.3. link associations with EADD workshop and/or provide supplemental training in BDS or marketing

20 PLWHA/OVC associations participating in workshops sponsored either by EADD or UDC

Association survey June – September 09

Agreement reached with EADD to include association members in their activities when feasible.

3.2.3.1. Mobilize women to participate in dairy production through community meetings

8 community meetings held to raise women awareness for dairy projects

Reports July 08

3.2.3. Increased number of women participating in dairy sector activities

3.2.3.2. develop action plan to address issues by associations

12 Work Plans developed by women to related to dairy activities

Work plans August 08

In meetings held with associations the majority of participants were women headed households.

Intermediate Result 3.3: PLWHAs utilizing new dairy production technologies 3.3.1. Provide tech support to

farmers to improve animal husbandry in association with EADD

3.3.1.1. Collaborate with EADD to encourage participation in workshops on proven animal husbandry techniques

8 workshops provided Workshop report plus material (brochures, curricula, etc.),

Sept 08 ABS conducted over 6 workshops with other scheduled on cattle management, AI, record keeping, animal health practices, etc.

3.3.2 best NRM practices identified and prioritized in association with EADD and disseminated through workshops

3.3.2.1. workshops conducted in collaboration with EADD to PLWHA/OVC associations and UDAMACO cooperatives

10 groups/associations applying one or more of these practices (zero grazing, tree planting, IPM, biogas, etc.)

reports May 09 2 biogas demonstration units set up on PLWHA farms, plus other models being tested. Other themes are being planned with target associations.

Rwanda Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 2008 27 Land O’Lakes, Inc

27

Intermediate Result 3.4: PLWHAs and OVCs acquire dairy-related employment

3.4.1. Increased revenues among families of PLWHA/OVC as a result of dairy related activities.

3.4.2.1. ID economic opportunities related to dairy in the Nyagatare/Gatsibo area in collaboration with EADD.

160 association members generating income from dairy related activities

Association reports/survey April 09 Process started with community meetings and will continue as IGA plan is implemented.

Strategic Objective 4: Dairy Producers in Nyagatare region aware of HIV/AIDs prevention practices

Intermediate Result 4.1: MCCs implement member-producer education programIR Objective Activity Indicator Verification Schedule Current Status

4.1.1. Information disseminated on HIV/AIDS 4.1.1.1. IEC materials (brochures, leaflets,

etc.) distributed to community members in promotion of HIV/AIDS prevention

17 MCCs participate in promoting HIV/AIDS related messages

Reports June – September 08

CHAMP distributed awareness raising material focusing on the key messages of AB and beyond AB to 17 Milk Collection Centers under UDAMACO. In all these messages targeted at least 3000 people. BCC organized a national level training of trainers for 22 people (5 of which intervene in Nyagatare and Gatsibo), on HIV/AIDS prevention, VCT and PMTCT

Intermediate Result 4.2: MCC member-farmers aware of key prevention practices 4.2.1. Distribute educational

materials to the community using MCC members and/or PLWHA association members. Also placement of radio announcements reaching the population

4.2.1.1. Raise awareness of community members on HIV/AIDS prevention, care and treatment, using RPO’s Community Health Workers, with special focus on HIV prevention among women and teenagers working through MCCs and associations

3000 community members receive information

IEC materials distributed KAP surveys among MCC members

June – September 08

(see above)

USAID Dairy Competitiveness Project CA# 696-A-00-08-00016-00

Quarterly Report April-June 200828 28 Land O’Lakes, Inc

4. UPCOMING ACTIVITIES

Activity Projected Timeline Follow on for national dairy initiative January + Develop inspection program with RBS/RARDA January - February Assist NGOs find funding and training for national lab Continuous Promote/start dairy IGAs in 5 high potential PLWHA associations Continuous Follow-on workshops in cattle management and related subjects Continuous Monitor feeding trials of direct fed microbials and enzymes for dairy diets (Bovine One) to explore potential for improvement of milk production.

Continuous

Visit herds for pregnancy diagnosis and documentation of production and management levels. Continuous