Diarrheal Disease - USAID

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Diarrheal Disease - USAID

ImplementingDiarrheal DiseaseControl ProgramsThe PRITECH Experience

Edited by Karen White and Eileen Hanlon

Management Sciences for HealthAcademy for Educational Development

1993

PRITECH (fechnologies for Primary HealthCare), sponsoredby the U.S. Agencyfor International Development, is a consortium of experienced, internationally known organizations led by Management Sciences fer Health. Subcontractorsinclude the Academy for Educational Development, the Johns HopkinsUniversity School of Hygiene and Public Health, the Program for AppropriateTechnology in Health, the Centre for Development and Population Activities,and Creative Associates International. PRITECH assists developing countriesto implement national diarrheal disease control programs and related activities, often as part of integrated programs of maternal and child health.

This document was funded by the Agency for International Development undercontract #DPE-5969-Z-00-7064-00, project #936-5969.

This book represents the opinions of the authors and does not represent A.I.D.policies or opinions.

This publication may be reproduced ifcredit is properly given. Suggested citation: K. White and E. Hanlon (eds.), "Implementing Diarrheal Disease ControlPrograms: The PRITECH Experience," M.1nagement Sciences for HealthPRITECH Project, Arlington, VA, 1993.ISBN 0-913723-30-4

Design by: Gerald Quinn

Production by: Cesar Caminero, Communications Development, Inc.

Printed on recycled paper.

ii

CONTENTS

Introduction: The PRITECH Experienceby Glenn O. Patterson and FRITECH staff .. ~ 1

Is the PRITfCI Field Mechanism a Model for the Future?A View from the Fieldby Robin Waite Steinwand 9

The Complexity of Health Communications 35

The Ciclopc Innovations in Rural Communication:Reaching the Unreachable Villages in Mexicoby Selene Alvarez L and Peter L Spain 37

zambian Popular Theater Dramatizes Diarrhea Treatmentand Preventionby Paul J. Freund and Benedict Phiri 43

Collaborating for Effective Health Communicationin Cameroonby Robin Waite Steinwand and Hugh Waters 51

Posters, Flyers, and Flipcharts:Usc of Health Education Materials in the Sahelby Elizabeth Herman and Suzanne Prysor-Jones 67

"We Couldn't Have Asked for More!"Lessons Learned in Information Disseminationby Karen White and lisa Dipko 79

Training and the OJIality of Care 95

Integrating Diarrhea Control Traininginto Nursing School Curricula in the Sahelby Suzanne Prysor-Jones 97

Successful Diarrheal Disease Training:Lessons from Cameroonby Robin Waite Steinwand and Ndeso Sylvester Atanga 107

linking Training and Performance: An Evaluationof Diarrhea Case Management Training in the Philippinesby Lawrence J. Casazza and Scott Endsley 123

iii

0IWns of the Ugandan National Diarrhea Training Unit:Steps in the Processby Lawrence J. Casazza 131

Cholera Control Activities in Guyanaand the Role of Training Workshopsby David A. Sack. and C. James Hospcdalcs 149

Improving ORS Supply and Distribution in the Philippinesby David Alt 161

Tapping the Potential of the Private Sector 177

Enlisting the Commercial Sector in Public Healthby Camille Saadc 179

Mobilizing the Private Sector for Public Health in IndollCliaby Lucia Fcrraz-Tabor 193

The Commercialization of ORSin zambia: Problems, Progress, and Prospectsby Paul J. Freund 207

The PRITECH-PROCOSI Collaboration:Working with a PVO Consortium in Boliviaby Ana Maria Aguilar and Peter L. Spain 217

Collaborating with Nongovcmmental Organizationsin Kenyaby Karm E. Blyth 227

iv

INTRODUCTION: THE PRITECH EXPERIENCE

The development of an inexpensive, safe, and effec- Glenn o. Patterson is

tive oral rehydration solution (ORS) revolutionized the tht Projcrl Dircrlor.

management of diarrhea in developing countries. Thissimple technology greatly expanded access to life-savingtherapy for cholera and other dehydrating diarrheas. Itformed the basis for the establishment of diarrheal dis-ease control (COD) programs in more than 100 develop-ing countries throughout the world.

The development of ORS, however, was only thebeg.... Jling of the story. To reach its life-saving potential,O1"S had to be imported or manufactured, packaged,financed, and distnbuted. Health workers had to betrained and supervised in the use of ORS. National policies had to be developed and negotiated. The populationhad to be alerted to the availability of ORS throughappropriate communication channels. Other aspects ofdiarrhea case management-such as the initial homemanagement of diarrhea, indications for referral to ahealth facility, effective feeding recommendations, theappropriate use of antibiotics, and the management ofcomplications-had to be defined. Systems had to be created to manage these tasks, to address problems, and tomonitor and evaluate progress. These activities comprisethe essence of the PRITECH experience.

The PRITECH experience thus refers to a ten-yeareffort to initiate, develop, and support diarrheal diseasecontrol efforts in countries suffering high rates of diarrheal morbidity and mortality. The lessuns learnedinclude successes and failures, challenges and obstacles.The relevance of these lessons extends far beyond the fieldof COD. It is hoped that by documenting them, this volume will facilitate a variety of other disease controlefforts.

Wheit IS PRITECH?

A.LO. initiated the five-year PRITECH (Technologiesfor Primary Health Care) Project in 1983 as a means ofimplementing oral rehydration therapy, one of its twinengines for improving child survival in developing countries (the other engine being immunizations). PRITECH II,the second five-year project, ran from 1988 to 1993. TheOffice of Health in ALO.'s Bureau for Research and

INTRODUCTION: THE PRITECH EXPERIENCE 1

Dcvdopment financed part of the $36 million bu ..~ d forPRITEOI ll. USAID field missions financed the n ....nainingshare through buy-ins for country-specific programs.

During the life of the project, PRITECH operatedtwenty-seven country and regional programs in Africa,Asia, and Latin America. Typically, PRlTECH organized aproject design team that worked with the local USAIDmission and the public health authorities in the countryto plan a multi-year program of assistance. The assistance usually included development or refinement of anational plan of action, implementation of a trainingprogram, initiation of communication activities. financing and coordination of consultant services, and supportofoperations re5edI'Ch. During the second halfof the project, PRlTECH also provided considerable technical inputto help parastatal companies produce ORS and to encourage local commercial production. Resident representatives worked directly with national COD teams to implement country programs. PRITECH also establishedregional offices in Senegal and Cameroon to provide additional support to country programs in the Sahel and inEastern and Southern Africa. Another regional office wasestablished in Honduras to facilitate activities in CentralAmerica.

The project was carried out under the leadership ofManagement Sciences for Health in collaboration withthe Academy for i.ducational Development, the JohnsHopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health,the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health, theCentre for Development and Population Activities, andCreative Associates International. In all of its work,PRITECH has collaborated closely with the World HealthOrganization, UNICEF, and other public and privatedonors, at both the headquarters level and within individual countries.

Lpssons Lei.1rnecl

Some of the many lessons learned from ten years ofimplementing diarrheal disease control programs aredocumented in this volume. The opening paper discusses the country representative as a mechanism for building capacity within countries and for implementing programs. The first group of papers describes a variety ofmethods, some unconventional, for communicatingmessages about the prevention and home management

2 INTRODUCTION: THE PRITECH EXPERIENCE

of diarrhea. It also includes a dcsaiption of PRITECH'scxtrcmdypopular information dissemination effort. Thesecond section describes a series of prcscrvice and inscrvice programs to train health workers to provide effective case management of diarrhea. Collaboration withnongovernmental organizations and commcrciaJ. companies is the subject of the last section and rcprcscnts thearea in which PRITECH bas done the most innovativework.

These papers, most of which dcscn'bc individualcountry experiences, capture only a fraction of thelessons learned through the PRITECH experience. A number of more gcncrallessons emerge from the combined.experience of the twenty-three country programs:

Systematic training is effective in changing healthworker behavior.

The diarrhea case management approach has established. new standards for the treatment ofsick. children inhealth facilities. Health workers no longer respond to amother's complaint ofdiarrhea with a prescription alone,nordo they recommend withholdir~food and fluids during diarrhea. Although health facility surveys show thatpcrfonnancc is far from ideal, taking a history and conducting a physical exam is now the norm throughout theworld.

COD programs are effective In reducing deaths dueto dehydration.

Prior to the introduction ofORS, health facilities wereoften inundated with children requiring intravenoustherapy for diarrhea-induced dehydration. Now, severely dehydrated children arc rarely SCC11. This is probablybecause caregivers arc administering fluids and seekinghdp early in the course of the illness.

Continued feeding during diarrhea and nutritioncounseUng are critical components of diarrheacase management.

Cardully conducted studies have conclusivdyshown that continued feeding during diarrhea not onlycauses no hano, but is actually therapeutic in decreasingthe severity and duration of the diarrhea. In many settings, the prevalence of malnutrition among childrenpresenting to health facilities with diarrhea is very high.

INTRODUCTION: THE PRlTECH EXPERIENCE 3

4

These facts emphasize the importance of nutritionassessment and counseling during these encounters.

The commcrdal private sector can be a valuableally in ina-easing the availability of OKS and inspreading case management messages.

Although public programs have increased the availability of DRS in health facilities, a large untapped market of other consumers still exists worldwide-a marketthat is ripe for increased corporate action. The commercial private sector can complement COO efforts by making DRS a common household item. PRITECH hasacquired substantial experience in enlisting the marketing strengths of the private sector in DRS pr<,duction andsales and in promoting preventive measU1'es such ashandwashing and breastfeeding.

Operations research can be effectively integratedinto COO program activities.

When provided with technical assistance with studydesign and with analysis, national COO programs areboth interested in and able to conduct studies to answerimportant prograIIllnatic questions. Operations researchsupported by PRITECH includes studies of the distribution and use of health education materials, research todevelop culturally appropriate feeding recommendationsfor children with diarrhea, evaluations of the effectiveness of training, investigations into the etiology ofdysentery, and aSSf:ssments of caregivers' performancein preparing sugar-salt solution.

Enthusiastic and committed individuals make adifference in the success of COO efforts.

Many of the successes of the PRITECH Project can beattributed to the commitment of individuals: the diarrhea treatment unit director who created a model training and outreach program, the dynamic program manager who effectively elicited and coordinated supportfrom a varidy of funding agencies, the respected university professor who mobilized support of pediatricians inhis country. An important goal of any disease controleffort must be to identify, nurture, and support theseenthusiastic individuals.

INTRODUCTION: THE PRITECH EXPERIENCE

Although COD programs have made great strides inthe fidds of training, communications, marketing, management, and research, the tasks that lie ahead are at leastas t:haIlcnging as those completed. The PRITECH cxpcriC11CC has idmtified a number of issues that will be keyduring the next tm years of COD efforts.

More effective strategies for encouraging swtamed behavior change among caregivers andhealth workers must be implemented.

Awarmcss of and knowledge about appropriate casemanagcmmt practices are not sufficient to achieve sustained behavior change. Health care workers and caregivers must perceive that these new practices arc of personal benefit to them, and an advantage over eurrmtpractices. COD programs must therefore pay increasedattmtion to understanding what m.:>tivatcs caregiversand health care workers, to presenting recommendedpractices in ways that appeal to their needs, and to supporting and reinforcing desired changes.

CDD programs must compete with other diseasecontrol initiatives in an atmosphere of dwindlingresources.

Although childhood diarrheal deaths have bem drastically reduced, it is estimated that 3 millionchildren continue to die annually from diarrheal diseases. Gains thathave been achieved will be lost if support is withdrawn.In order to maintain interest and funding, programsmust systematically demonstrate their effectivmess andpursue ways of integrating activities with other programs.

Cholera control efforts must be channeled throughnational COD programs In ways that support andstrengthen ongoing COD efforts.

Although more childrm die from non-cholera diarrhea in one day than die ofcholera in one year, there is afCc1J' that the rcsurgmce of cholera in Africa and theAmericas will distract attention and funds from CODprograms. Cholera control committees have been created outside of the national COD programs, often withhigher political status, and sometimes without the participation of the COD program personnel. When appro-

INTRODUCTION: THE PRlTECH EXPERIENCE 5

6

priate, COD programs should usc the higher profile ofthecholera program to upgrade their own programs and tobroadm their contacts inside and outside the ministry ofhealth. I.ikcwisc, cholera control efforts should takeadvantage ofexisting channels and mechanisms for CODtraining and communications, while at the same timestrcngthming COD programs.

Integration and decentralization should not bepursued as goals in themselves, but evaluated asstrategies for achieving public health objectives.

Many ministries ofhealth and donors have expressedinterest in integrating COD programs with other programs such as those for the control of measles, malaria,nutrition, and acute respiratory infections. Althoughthere is clearly a good rationale for doing so, integrationitself will not solve chronic problems of suboptimaltraining, inadequate budgets, poor supervision, and difficult logistics. Before large investments arc put intorevising training materials and reorganizing ministries,some key issues regarding integration must be addressed:What precisely is meant by "integration"? What is thebest mixture of child survival programs to be integrated? Is integrated training efficient and effective? Whichprogram components are most amenable to integration?At which levels of the health system does integrationwork?

Similarly, donors and national COD programs havesought to extend the reach ofCOD efforts through dccmtralization of COD program activities to regional or dis.:.triet levels. PRITECH cxpcrimce suggests that, for dccmtralization to promote the achievement of public healthgoals, the following requirements must be met: 1)involvemmt of peripheral COD staff in the developmmtand dissemination of the national COD policy; 2) institutionalized mechanisms for communication betweendiffermt levels and well-defined assigned responsibilities;3) a carefully planned strategy to decentralize trainingand ensure supervision; 4) standardized policies andtools; 5) availability of sufficient resources to the locallevel; and 6) continued and regular supervision by central staff to provide leadership and consistency.

INTRODUCTION: THE PRlTECH EXPEIUENCE

Collaboration with other actors and -allies'" mustbe pursued to expand the reach of the public sector.

These collaborators might include traditional healers, nongovernm.mtal organizations, schools, and com"mcrcial companies.

Service delivery must be adapted to meet the needsof urban populations and other high-risk groups.

Urban slums, refugee camps, and war-stricken areasall contain childrm at high risk for diarrheal diseases.There is still much to learn about effectively reachinghigh-risk populations in a sustainable way. How can aCOD program communicate with households about oralrehydration therapy? How can programs reduce the burdm of disease in overcrowded areas whm governmentresources for mviromnmtal improvements are limitedand populations are growing at an exponential rate?

Oear and comprehensive protocols for the management of dysentery and persistent diarrheamust be implemented.

As programs to promote the availability and usc ofORS achieve success, the number of children dying fromdiarrhea-induced dehydration has dramaticallydecreased. Deaths from other causes of diarrhea-relatedmortality-specifically dysentery and persistent diarrhea-have not been proportionately reduced. Therefore,in some areas, dysentery and persistent diarrhea accountfor roughly 30 to SO percent of diarrhea-associateddeaths in children under age five. Reducing these deathswill be an important challenge for COD programs incoming years.

INTRODUCTION: THE PIU'l'ECH EXPERIENCE 7

IS THE PRITECH COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVEMECHANISM A MODEL FOR THE FUTURE?A VIEW FROM THE FIELD

Minutes from the 1992 meeting of the TechnicalAdvisory Group on diarrheal disease control call attention to the enonnous success of &e country representative mechanism in the PRITEOi Project. (The group ischaired by AI.O.'s Office of Health with representativesfrom UNICEF, the World Bank, the World Health Organization, several universities, and nongovcmmentalorganizations who work in child survival.) The firstpoint listed on which the advisory group reached consensus refers to this success:

PRITECH's use of long-term advisors in developingcountries has been remarkably effective in tenns ofsuccessful program implementation and cost-cffcctivcness. The advisors have developed relationshipswith the local ministries of health, coordinateddonor resources in the COO field, and helped toestablish national health policy. Despite the heavyadministrative burden of establishing and sustaining such long-term programs, the approach meritscontinuation.

Robin Waite Steinwand was theCameroon CountryRqnsmtativc.

L•

BdC!\fjIOllllcl , ..

Long-tenn technical advisors, or cvuntry representatives, are not unique to the PRITECH Project nor arethey the sole answer to increasing the success of development assistance projects. Also, the maintenance of afull-time representative of a single project in-countryentails a considerable cost. Nevertheless, the PRITEOiProject has demonstrated considerable success in the useofresident technical advisors (country representatives) toaid the development of strong national control of diarrheal disease programs.

This paper, written from the perspective of a formercountry representative, looks at the evolution of thecountry representative role. It also identifies the characteristics that have contrib,"ted to the success of thismodel. The paper's purpose is to encourage discussionand consideration of the model for Oeler assistance projects of its kind.

• COUNTRYREPRESENTATlVE MECHANISM

!"revfo'~CJ Pa~e BlaDk9

10

HlsTORICAL CONTEXT

When the PRITECH Project was conccivtd, there wasno intent to place long-term staff in the fidel. Oral rehydration therapy was a proven technology, and it waswiddy believed that countries would require only shortterm consultants from the United States and abroad toimplement programs to promote oral rehydration. Someof the earliest project support was to national CDD programs in the Sahd, where a regional office fidded shortterm consultants in response to country requests. A needwas soon identified, however, to have individuals incountry who could assist the national COD programwith day-to-day follow-up ofplanned activities. Inkeeping with project philosophy to avoid costly in-countryadvisors and a budget that did not include funds for longterm advisors, and to minimize the compensation gapbetween national program staffs and expatriate technical advisors, the first country representatives wererecruited locally for organizational rather than technicalskills. In short, these representatives cost the project lessthan high-profile health professionals and were backedup with strong technical support from a growing regional office.

The success of the Sahd mood brought an increasing realization that money invested in a full-time presence reaped program rewards worth replicating. As thePRITEOI Project expanded into other countries andregions of the world, representatives were identified andhired (mostly locally) with more public health and program management expertise than before, sometimesbecause of availability in-country, sometimes by specific country request. Soon the range of skills and skill levels of the representatives was as varied as the countriesin which they worked. Country programs with full-timetechnical assistance generally progressed more quickly,and funding expanded to permit this important enhancement to the project.

THE PRITECH MANAGEMENT MODEL

Discussion of the PRITEOI country representativemust include the framework within which a representative operates. As a centrally-funded A.I.D. project,PRITECH has a Washington, D.C.-based headquarterswith administrative as well as technical staff. Together

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

with regional staffs in Africa and Central America, theyoversee and support country representatives in Africa,Asia, and Central and South America.

Sustained programs-national COD programs thatreceive substantiallong-tcrm support from PRITECHhave country representatives. Intermittent programsreceive only sporadic assistance, sometimes as a first steptoward a fully sustained program. They have no representative and thus are not discussed here.

All country representatives with the PRITECH Projectreceive strong technical and administrative backup fromregional and headquarters staff, but depending on theregion and the particular needs of the country program,there are different management structures for their support. In general, these can be divided into two categories,described below.

COUNTRY REPREsENTATIVEWITH REGIONAL OFFICE SUPERVISION

Two regional offices in Africa support country programs: the Sahel Regional Office, and the Central, Eastand Southern Africa Office. A third, in Central America,handles primarily region-wide programs.

Sahel Regional OfficeThis regional management mood has been quite suc

cessful in meeting the needs of the country programs. Itincludes a regional technical support office with its ownbudget and has representatives in most operational countries. Key characteristics are:• The regional staff consists of senior managers and

technical specialists recruited mostly from within theregion, which strengthens local resources andstrengthens PRITECH's relationships with countries.

• Routine, frequent country visits are budgeted and programmed. Trouble-shooting visits can occur as needed; short trips for specific needs are more feasible.(Travd of technical staff from headquarters reql:.ireslonger trips, planned carefully in advance.)

• Regular staff dcvdopmcnt, such as participation inWorld Health Organization (WHO) orientation ortraining courses, is programmed into a regional budget and plans.

• The regional staffcan facilitate good cross-fertilizationamong countries through visits of country rcpresen-

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 11

tatives and their colleagues to other countries in theregion and sharing of problems and solutions byregional staffwith countries in similar circumstances.

• The region draws on a pool of regular consultants tosupplement skills of regional staff when needed.

Central, East, and Southern AfricaUntil recently, only a few of the sustained country

programs have had representatives, while most countryprograms were intermittent programs, supported byvisits as deemed necessary from a regional programmanager. Since there has been only one person in theregional office, countries have depended on a combination ofheadquarters staff, the regional person and a bankof outside consultants for technical support.

Country Representative with no Regional OfficeFor the most part, country programs in this catego

ry have been larger countries in South Asia and Africawith greater in-country technical resources. Their country representatives have been more senior and more technically expert in diarrheal disease control. They tend tobe more autonomous, receiving some technical support,but primarily administrative and financial support fromheadquarters.

St l('lHjtlls of the COlillt ry Rl'prt~Sl\llt(ltlVC!Ml~chlllW)1ll

PRITECH's country representatives have been successful for a number of reasons, some of which are characteristic of long-term advisors in general. Bilateralhealth projects and private voluntary organizations havefor years used a full-time project representative in-country. With the right combination ofpersonalities, this person can greatl} facilitate communications among partiesinvolved in the project area, act as a catalyst, and provideimportant continuity often lacking whea relying solelyon short-term technical assistance.

Some qualities particular to the PRITECH countryrepresentative mechanism, though perhaps not unique,have largely contributed to making this mechanism anoutstanding success of the PRITECH Project. Theseinclude flexibility in funding, strong technical support,an emphasis on building relationships and sustainability, and a mandate to facilitate donor coordination. (Seegeneric position description in Box 1.)

12 THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

13

THE REPRESENTATIVE AS CATALYST

Full-time presence in countryNot enough C"'ClIl be said of the value of having a pro

ject,representative in place who can build a relationshipof trust with the country program staff, whose role it isto gently nudge policymakerc; to concentrate on CODissues and to follow thrm..:c;h with plans. Although diarrhea is usually among the top priority diseases in a country, a well thought-out action plan may become derailedwhile ministry of health officials deal with other press-

Box 1. Position Description

Title: Country representative

Reports to: Senior program manager

Overall responsibilities:The country representative manages, lmder the direction of the senior program manager, PRITECH's resources for canying out "sustained" countryprograms. The country representative coordinates with lISAID and otherdonors that support the program. The country representative reports to thePRITECH Project director about the progress of the country program.

Specific responsibilities:• Assists the national COO program manager to implement the national plan,providing staff assistance to help organize and administer program activities.• Manage PRITECH activities in accordance with the PRITECH program planand the annual implementation plan. Prepare drafts of the implementationplan and subsequent revisions.• Administer PRITECH funds in accordance with AI.O.'s contract requirements and the contractor's financial management procedures.• Identify program implementation problems and bring them to the attention of the senior program manager and PRITECH Project director.• Prepare regular reports as indicated by PRITECH, including periodic fieldnotes addressed to the PRITECH Project director.• Coordinate with other donors that support the Imtional COD program, andkeep PRITECH's spon'lor (usually lISAIO, or perhaps UNICEF) informedabout the status of program activities.• Facilitate the work of PRITECH consultants, including preparation ofscopesof work and arranging administrative support.

Qpalifications:• Experience working in the country, preferably with health services programs.• Fluency in the language used by the government.• Strong rrumagerial, organizational, and administrative skills.• Training or work experience as an expert in a technical area of COO desirable.• Social science research skills will be important where PRITECH responsibilities include operations research and surveys.

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

14

ing health issues, throwing off activities scheduledmonths in advance. Likewise, ministries of health areoften short on support personnel and well-planned activities can fail to happen for lack of follow-up on small butimportant details. There is no substitute for a person whocan help to follow through with small details that requiretime and energy and an understanding of the issues.

Country representatives help the COO team wheremost needed, from the mundane to the highly technical.Their role is not highly defined, so they have been able torespond to changing nat~onal needs in a very timelymanner. This flexibility has !;;o:atly enhanced the level oftrust that develops between the representative and hostcountry officials.

The country representative has also provided important program continuity at times of major personnelchanges within a ministry of health. As an outsider, theTl'Presentative has been able to serve as a bridge betweenthe old and new appointees, with less vulnerability tosuspicions and tensions that often accompany majorshakeups than the host country program staff. This hasbeen true in Cameroon, zambia, Pakistan, Mali, andNiger, among others.

Funding flexibilityPerhaps more than any other characteristic, the abil

ity to disburse funds in a flexible manner has enhancedthe representatives' effectiveness, credibility, and trust.Unlike many project representatives, PRITECH representatives can use country program funds to support localcosts at short notice, if necessary.

This mechanism has given country representatives acertain influence over program direction that donorswith fixed budget line items seldom have. Likewise, therepresentative is able to support creative directions of theministry of health that might otherwise get lost in thefunding process; to advance funds for crucial activitiesbudgeted by major donors when their funds were late inarriving; and to recognize and respond to immediateunforeseen needs of the program. A full-time representative is well-placed to judge the most appropriatemoments to use funds to support real program needs andwhen to hold off and let program managers work outsolutions of their own. All PRITECH financial support, ofcourse, must be within the budget allocations and coun-

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

try program strategy and annual workplan approved byPRrrECH headquarters and the A.LD. project officer.

Local recruitment 8r.'d familiarity with countryWhat began out ofbudgetary necessity has proved a

source of great wealth to the PRITECH Project. Mostcountry representatives have been recruited locally.While previous in-country experience is neither a prerequisite to nor a guarantee of success in that country,local recruitment can result in identifying a country representative who has already established professionalcredIbility with the ministry of health and other healthpoHcyrnakers and donors. This also allows the ministryof health to participate more fully in the selection anddecisionmaking process. This selection process overallhas produced a diverse international group of countryrepresentatives--a rich mixture of skills and nationalities. The representative fOWld in-country may be animpartial outsider, able to avoid involvement in ministrypolitics, yet known to key players through past experience with other projects in-country. Ironically, the mostly expatriate COWltry representatives have often been saidto provide Ucontinuity" to ministries of health in whichstaffing and structural changes are frequent.

The country representative in zambia, for example,has been called a unational treasure" for his longstandingrole in health planning. Before joining PRITECH, heworked with the National University of zambia for fiveyears and helped establish a national community healthresearch unit and national primary health care development committees. As the new government in Z..mbia hasembarked on major health policy reforms, the representative has helped to shape those reforms. His intimateunderstanding of the new policy directions has greatlyenhanced his ability to act as a spokesman in Washington, D.C., for these changes, which is all the more usefulfor a COWltry program whose A.LD. support is entirelyfrom central funds.

With previous knowledge of the country and a flexible role, the PRlTECH representative has been able toadapt the PRITECH COO agenda to facilitate achievementof overall program objectives in the light of changinghost-COWltry conditions and personnel.

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 15

16

In-c:ounby support of short-term technical assistance

Th~ presence of a country represmtative has madean mormous difference in the effectivmess of short-termconsultants to the COO programs. The representative isin a position to recognize early and respond to ministryof health needs for outside technical assistance. The representative can help ministry staff to better define thetype ofassistance they need, and provides a link to available resources through the network of contacts with theregional and home offictS as well as with the multinational donors. Similarly, the country represmtative canassist th~ ministry with adequate preparation for a consultant, and can oversee and help assure follow-up to thevisit. The country representative can also help the ministry to assure appropriate representation of host country nationals on technical assistance and evaluationteams. This further strmgthms the possibility of appropriate follow-up when the Itexperts" have gone home.

PRITECH generally uses its own regional or headquarters staff, plus a core of familiar consultants, forshort-term technical assistance. These are people withwhom country represmtatives have easy contact so thatquestions about follow-up or further information needscan be communicated. Very often, the same consultant(s) return several times to the same country.Through this system, the needs of the host country aremore readily met and their confidence in the consultanthas been successfully established.

Support from PRITECHlWasbingtonThe ability of the PRITECH country represmtatives

to provide a broad range of support to national COO programs has bem made possible by the very strong network of technical support as well as financial and administrative back-up which the project offers. PRITECH'stechnical experts work in concert with WHO's COO andAcute Respiratory Infection Programme staff in Geneva;oftm PRITECH works under the auspices of WHO whmimplementing activities in countries. It is this in-housesupport, backed by the technical weight and guidelinesof WHO, which has so enhanced the representatives'credibility.

THE COUNTRY REPRESErlrATIVE MECHANISM

Tedmical expertiseCmmtry representatives are buttressed technically

by a strong network of experts in many areas of diarrheal disease management. The project has in-housetechnical expertise in diarrhea case managemmt, communications and training, operations research, supervision and evaluation, breastfeeding, project managemmt,and private sector oral rehydration salt production andmarketing: A broader range of specialists can be accessedthrough PRITEOI's subcontractors. Through regularsupervision and support visits, a regional technical officer or headquarters staff assigned to the country program can help the cmmtry represmtative and nationalCOO team to assess progress or specific program needs.When there is a difficult decision to make or an unpopular judgmmt on use of funds, this outside person canintervene rather than hinder the representative's relationship with colleagues in-country.

Visits by technical support people (from headquarters, the Sahel Regional Office, or PRITECH's consultantbank) are programmed according to the country program's needs and plans. Because these people work withmany country programs, they facilitate sharing of experiences and program materials across countries.

The PRITECH Information Cmter located at headquarters provides an excellmt resource, sharing the latest technical information as well as infonnation aboutother country programs and materials produced. Theexistence of an in-house infonnation collection and dissemination center not only lessens tum-around time oninformation requests by representatives for the countryprogram, but also provides the represmtatives withappropriate technical material for activities related totreatment providers, }X>licymakers, and oral rehydrationsalt producers. Scientific papers and the timely technicalreviews in the Technical Literature Update on Diarrhea canhelp convince doubting physicians of the benefits of oralrehydration therapy. In countries where up-to-dateinformation is hard to find, the ability to present pertinent documents or to put potential collaborators onPRrrECH's mailing list for technical publications heightens the representative's credIbility on COD substantially.When the Indonesian country representative wanted toconvince a multinational corporation to promote soapfor handwashing to prevmt diarrhea, for instance, sheused sup}x>rting research from the Infonnation Center.

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 17

]

18

Fidd notes and other communicationsCmmtry representatives keep regional and head

quarters staff abreast of country program activities andplans through standardized documentation of programexperiences (monthly field notes) as well as telephonecontact when needed. Both are two-way communications. Response to the field notes from headquarters hasplayed an invaluable part in supporting the work of thecountry reprcsmtatives and improving the ability offieldstaff and technical support staff to communicate. Individual members of the technical or administrative teamsread and respond to issues raised with which they canhelp. When the Cameroon representative wrote in herfield notes of initial plans to develop a local mothers'pamphlet on oral rehydration therapy, for instance, theTcchnical Unit immediately sent out samples of othersfrom around the world. Less formal telephone communications with a supervisor provide technical feedback,moral support, and the opportunity to discuss programoptions and issues as needed by the country representative.

Field notes arc copied to COO program managers andUSAIO missions, in addition to PRITECH staff, to document agreements on program plans.

PROMOTION AND FACILITATIONOF COMMUNICATIONS

Communications within the Ministry of HealthWith a primary task to strengthen program man

agement, the country representative frequently encourages and helps colleagues to recognize the importance ofteamwork. As an outsider, usually based in a ministryofhealth office, the country representative can more easily make the first attempt to bring another branch intothe COD planning process. The national COD coordinator may be too junior within the ministry hierarchy totake the initiative to link up other services with the CODprogram or for other reasons may not have pursued theadvantages of integrated programming. Country representatives have quite successfully helped COD programsto extend their planning sphere to include offices ofhealth mucation, maternal and child health, research andplanning, and nutrition.

In the Sahel countries, for example, PRITECH has frequently helped bring COD program managers to work

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

with staff of the health education unit; health educationstaff receive training in materials production which thmbenefits all programs.

Communications between the Ministry of Healthand USAID

The PRITEOI representative is oftm based in theministry of health complex, but since PRITECH isfinanced byAI.D., the rcpresmtative is perceived as having some of the authority ofan A.I.D. employee. At thesame time, he or she is seen as having a very detailedunderstanding of ministry programs and problems.Much morc than chiefs of bilateral assistance projects,the country representative is perceived as a helpful broker for the interests of the host government ministry andAI.D. The ministry of health has a representative theycan trust to interpret their programming directions andrequests for assistance and who, with perhaps years ofexperience in country, has developed an intimate understanding of ministry policies IUld goals.

likewise, USAID, whose health sector is increasingly understaffed due to budgetary constraints, can turn tosomeone who works closely with the ministry and is fluent in the national language, and who, being bound byUS government rcguIations for management of funds,can help to interpret those regulations to ministry officiaIs. The representative is also in a good position to findappropriate opportunities to remind ministry officials oftheir commitments to the donors. At the same time, thercprcscntative, through regular written reports and frequent informal visits to USAID, serves as a CDD technical advisor to USAID.

In Pakistan, for instance, where the COD programwas heavily funded by USAID, the PRITECH representative played a crucial role in facilitating communicationsby organizing meetings and providing the governmentand USAID with regular memos and briefings onPRITEOI's and each others' activities. She also promotedand facilitated visits to health centers and project sites byUSAID and by visiting dignitaries such as a US Congressional delegation arrd commcrciaI sector representatives.

Communications with USAlD and A.I.D./WashlngtonCompared to projects with only short-term techni

cal assistance, the PRrrECH country representative greatly reduces the management burdm on AI.D. The repre-

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 19

20

sentative helps the national program staff keep theUSAID mission abreast of project issue; as they arise.When short-tmn technical assistance is needed, thecmmtry representative lays the groundwork and assuresfollow up. In Washington, the PRITECH central officebandies nCCtSsary arrangements, usually for its own inhouse staffor frequently used consultants.

Through country technical support visits and country representative communications, the PRITECH regional and headquarters staffs maintain an in-depth understanding ofpolicy directions and program activities. TheAI.D. project officer for the PRITECH Project in Washington meets frequently with headquarters staff, supplementing the program information received fromAI.D.'s country misf.ion. In this way, PRITECH's centraloffice and the AI.D. project officer remain abreast of project activities and can actively promote the project andalert their colleagues at WHO and UNICEF headquartersabout emerging problems in countries that need coordinated action. By extension, the national COO programhas a strong international forum for publidzing its programs and its needs. Ukewise, notable successes can bequickly communicated.

Communications among donorsThe generic job description for a PRITECH country

representative specifies that the representative will fadlitate the coordination of donor activities in COD. Manybroader health projects overlap with COD activities, so inpractice country repK$entatives have fadlitated information sharing for man}! primary health care activities.The perception of the PRITECH representative as moreneutral than someof the major donors enhances the ability to initiate coordination. When the country representative has been in country for some time, personal relationships allow himlher to talk about issues that maynot be discussed in official meetings. 'fllis may help to initiate coordination that was lacking or to diffuse misunderstandings early on. Also, in many countries, thenational COD coordinator is required by ministry ofhealth protocol to follow the hierarchy in order to makecontactwith donor agendes. Through informal contacts,the representative isable to keep donors abreast of important ministry activities in COD and thereby decrease thepossibility of misunderstandings as well as keep COD inthe donors' minds between the important formal min-

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

istry contacts. This infonnal network has bem especially important in cmmtries where no fonnal COD coordinating lxxfy has been established.

The country representative uses this coordinationrole to mobilize donor support for the COD programbefore fonnal negotiations begin or for special needswithin a budget period. In several countries PRITECH hassuccessfully garnered the involvement of the private sector in the national COD program. The country representative can more easily approach the private commercialsector and smooth over any fear that discussions withgavcmment will lead to increased regulation of theirbusiness.

In one country, the country representative becameaware through infonnal discussions that a major donorplanned to circumvent communications with the ministry on its five-year funding plan. The representativewas able to apply subtle outside pressure to reintroducerealistic ministry participation in the process.

Coordination with other A.J.D. projectsThe anmtry representative has frequently hdped

USAIDand the ministryofhealth to coordinate COD activities with other AI.D centrally-funded projects, many ofwhich have no full-time representation in country.

It is inherent to the PRmCH rp.presentative's role tohelp the COD program coordinate with bilateral healthprojects to insure integration into global primary healthcare.

Although the country representative mood has successfullyenhanced the PRrrECH Project's ability to support national COD programs around the world, a fewkey issues have recurred throughout the life of the project which bear analysis here. As increasingly projectsengage full-time technical assistance, it is hoped that thelessons of the PRrrECH Project will help other projectsmake informed decisions.

STRONO PREsENCE VERSUS THE RIsKOF DEPENDENCY

The primary goals of PRlTECH's country representatives have been to help bolster the COO program in its

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 21

22

initial stages and to help the ministry of health to develop the managerial capacity to sustain the program in thelong term. In itself this implies a dilemma, since longterm donor and ministry commitment to the programmay depend heavily on early success.

The country representative has been an importantfactor in keeping the COD program on target, often helping with unforeseen necessities common to a young program. While the need may have arisen as a result ofinadequate planning, a good representative can effectivelydistinguish between immediate, unforeseen needs andthose that should be better planned pr can wait forplanned funds to come through. With time, managerialskills are strengthened so that fewer and fewer situationsrequire quick-fix funding or intervention. The representative, having established credibility and the trust ofministry personnel, can more readily take a hard line onfunding when necessary. Nevertheless, the dangeralways exists that the representative will become tooinvolved, too interested in immediate results to standback and allow program personnel to confront managerial decisions. Ifso, the project risks creating a dependency on the representative's timely interventions. The flexibility so important to the representative and newprogram's success can, if misapplied, hinder the program's long-term sustainability.

Country representatives must dedicate themselves tofostering good managerial habits such as long- andshort-term planning and regular meetings with interested parties. They must daily assess and make judgmentsas to the amount of involvement to take, never usurpingthe host country staff's ownership ofboth program successes and disappointments. The goal is to move gradually from a role of active collaborator to outside technical advisor as the program becomes more firmly plantedin the ministl1' priorities and budget.

RECOMMENl)ATIONS

Both recrui~ent and supervision of country representatives m~~ stress the importance of building sustainability over the rteed to achieve quickprogram growth and success.

It is incumbent on the project, once a representativeis hired to assure slhe does not lose sight of the ultimategoal-a sustainable COD program with strong manage-

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

mmt and only sporadic outside assistance. This is anongoing process from orimtation through supervisionand performance reviews.• RLcruitmmt. Selection of a country represmtative

should favor an individual who can maintain theproper pcrspcctive and balance over more technicalqualifications. Good judgmmt, maturity, sensitivity,and humility should figure prominently among applicant qualifications.

• Orientation. A solid orimtation for every employeeshouldclearly emphasize the project's position on sustainability. This might include case studies of difficultsituations encountered by past representatives.

• Supervision and personnel evaluation. Because there isoftm a fine line betwcm sustainability and programachievement, frequent contacts by supervisory personnel from the region and headquarters are necessaryto give the representative an outside clear perspective.Regular perfonnance reviews should include the developmmt of annual workplans, which have the representative address the issue of sustainability versusdependency.

The donor (OSMD) and pro;ect supervisors mustacknowledge that good proj«t management andsustainabllity will not be achieved overnight.

They must not value immediate results to the detriment of consensus-building and the creation of broadnational support for the program.

ExPATRIATE VERSUS HOST COUNTRY NATIONALREPREsENTATIVE

Without a doubt, anyone involved in internationalhealth has debated this issue for years and PRITECH is noexception. PRITECH has chosen to hire primarily expatriates already living in the country of service. There aresome cxceptions-cxpatriates hired from outside thecooperating country and host country or cooperatingcountry nationals. Flexibility has been a key factor, taking into account the wishes ofministry ofhealth officialsas well as availability of appropriat.-: candidates in country. In many cases, PRITECH has bem fortunate to findan individual living in the country and looking for workwho has public health and management experience inother countries as well.

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 23

24

The advantages of an expatriate are many. Slhearrives as an impartial outsider, with no political attachment in country. Not duty bound to a local patronagesystem, the expatriate can spend less time denying favorsand can more easily make unpopular decisions. Someonewho has had previous experience with the US govcmment budgetary process can talk more easily with donorsand the USAID mission. If the person has in-countryexperience, he may have established professional credibility with local officials and have a greater understanding of the politics of business in that country. With abasic familiarity of the culture, a locally hired expatriatealso tends to realize more readily the limitations of hisknowledge of the culture. In a large multicultural country, a country national from one region of the countrymay have difficulty admitting to gaps in knowledge ofother regions.

On the other hand, country nationals bring a heightened sensitivity to process to thejob. Keenly aware of thecultural norms and fluent in one or several of the locallanguages, they can involve the right people and understand how not to offend others. However, the compensation package of a country national representative raises myriad problems. If compensated as otherrepresentatives, particularly in a country with few private voluntary organizations and generally low wages,their work can be blocked by abundant jealousy amongless well-paid ministry counterparts. Compensation at alevel commensurate with other nationals but differentfrom representatives in other countries can lead to strainwith the project.

One argument for hiring country nationals as project technical advisors is the need to build local resources.PRITECH has attempted a different approach, in the SahelRegional Office, which has been very successful. Most ofthe staff of the regional office is from the region. Theirknowledge of the region enhances their work and working relationships as technical support people, withoutmany of the hindrances of working in a managerial andadvisory role in their own country. As regional staff,they can avoid the issue of nongovernmental organization salary versus ministry of health salary levels.

Ideally, a conscientious expatriate representative willseek the national COD staff's technical knowledge anddepth of understanding of the problems to complementhis own understanding and perspective. As the program

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHAMSM

gains strength, it should be far easier for an expatriateadvisor to work himself out of a job than for someonefrom the country who is more emotionally attached. Theexpatriate representative can achieve little, however,without dedicated colleagues-national counterparts.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In general, an expatriate can assume the role ofoutside technical consultant (country representative role) with more success and fewer problemsthan a country national.

If an expatriate can be identified who has alreadyestablished professional cred1bility in country, this hasadditional benefits for the project. If a project plans notto hire country nationals as representatives, this shouldbe stated policy with a clear justification.

A project should have a well-defined and publicized recruitment and hiring policy.

Such a policy details all aspects of the compensationpackage and which categories of individuals have accessto them (country nationals, third country nationals, andUS nationals hired locally, and so on).

Encourage the hiring of local talent and expertise.Local personnel should be recruited when hiring a

representative for a nearby country with a new program, and to staff regional offices and as regular consultants whenever possible.

DECENTRALIZATION VERSUS STRONG TECHNICALAND ADMINISTRATIVE OVERSIGHT

The PRITECH Project is relatively decentralized. Itscountry representatives exercise a great deal of latitudein making judgments about the technical content of theproject, in developing relationships with the ministry ofhealth and other partners, and in defining project direction based on ministry programming needs. This latitude, or flexibility, has contributed to more responsiveproject assistance.

Ironically, effective decentralization is possible onlythrough strong technical and administrative supportfrom the central staff to the representative, their decisionmaker in the field. Frustration ofcentral or field staff

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 25

26

has sometimes resulted from lapses in the central systemof support to the field or in communications to and fromthe field.

Some key elements of the support system wereimplemented only as the proj"'d: grew, sometimes aftercostly errors had demonstrated a clear need for them. Forexample, improved financial orientation is gainingmomentum because country representatives not welltrained in accounting would submit confusing financialrecords or make transactions requiring much time andfield visits to correct. For better technical orientation, inthe second phase of the project, new country representatives began participating in a WHO course on COD, giving representatives an early familiarity with the technical jargon and policy directions of ministry of healthpersonnel.

Other components of the central support system,such as headquarters to field communications, startedout on firm footing, but have fluctuated over the life ofthe project. Headquarters staff provided excellent andtimely feedback on all field notes until staff changes andother issues at the central level usurped important timefor this task. Feedback became sporadic and the countryrepresentatives more isolated.

As discussed earlier, the technical resources availableto PRITECH representatives greatly extend both the depthand breadth of technical expertise they bring to theIl..1tiOnal COD program. However, as the project hasgroiVD, it has become increasingly difficult to schedule avisit by the appropriate centrally located technical personat the time most needed. PRITECH's Sahel Regional Office,with its own cadre of specialists, has demonstrated theability to respond more expediently to the country programs that it serves. Because of the lack of funding, thishas not been repIicated for other regions that are geographically far from headquarters.

The project has also experienced occasional difficultiesamong its tiers (headquarters, region, country representative). For example, technical staff who have the advantage of stronger technical skills and a multinational perspective may question a national policy decision whichdoes not seem to concur with international guidelines,though the country representative may defend it as a wellthought-out exception to the guidelines. The regionaloffice may insist on being the conduit for all official communications between headquarters and the country rep-

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

•

rescntative, though this can add significant delays if theregional supervisor bas a heavy travel schedule.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Every effort should be made to provide strong central support necessary to enhance and maintaineffective decentralization.

All support-strong technical backup, financial, andadministrative support, and good field to headquarterscommunications-should be with the primary goal ofassuring the full participation of country program staffin the successful development of their COD programs.

Strong technical backup:• Standardize technical orientation for all new country

representatives to include preservice technical briefingsby central staffand early participation in a WHO CODcourse.

• Provide strong support to representatives by technicalresource people (1) in response to needs expressed bythe country program; and (2) through informationupdates distributed to keep the field abreast of currentinternational policy directions. To facilitate the bestuse of technical resources, country representativesshould receive a directory of technical resource peopleand areas of specialization.

• The Sahel Regional Office model for technical supporthas been very effective. To the extent other regions andprojects could benefit, resources should be committedto replicate this experience.

• Information requests must be responded to quickly.PRITECH's Information C~nter has institutionalizedthe capability of rapid and thorough response to allinformation needs related to COD, as well as documentation and sharing of country program experiences. This model or a centralized variation for several projects in a similar field, merits furtherimplemmtation.

Financial and administrative support:All new country representatives should receive rig

orous orientation on contract and A.I.D regulations,company policies, and project financial managementfrom the outset, with early follow-up visits as necessary.It is especially important that a country representative

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 27

28

whose job it is to advise the ministry of health on program management have a sound command of financialand reporting requirements for the project.

QocumentatioD and good communications:• Standardize field reports and provide rapid construc

tive response to monthly reports. Docummtation ofproject experiences is one of the greatest missing elemmts in good projects, but timely feedback is probably the greatest incmtive for field staff to devote timeto documenting those experiences. Field reports shouldhave a standardized format, streamlined so as to posethe least burdm to people whose primary role is providing on-site technical support.

• Response to field notes is essmtial and should not besubject to other pressures on headquarters staff.Important clemmts of cmtral feedback to reportsinclude: (1) acknowledgment of communicationswithin short interval; (2) positive nature of response;(3) sharing of experiences (programming dilemmasand solutions); and (4) rapid response by technicalunit and information center to information needsexpressed in reports.

• Field notes (from country represmtative to headquarters) should be copied to all interested parties (CODprogram staff, the USAID health officer, the countryrepresentative's supervisor). The goal is candid reporting that can serve further discussion on programdevelopment. Issues requiring discretionary treatmentshould be handled separately.

• Both country representatives and supervisory staffshould assure that there is adequate communicationon program direction and issues through regularsupervisory visits and informal telephone or other

.communications.

COST OF LONG-TERM COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVES

The introduction to this paper refers to a quote fromthe 1992 Technical Advisory Group report that "the useof long-term advisors...has been remarkably effective interms of successful program implemmtation and costeffectiveness." [emphasis added] There is substantial evidence that the country representatives have been generally effective. But their cost has varied considerably overthe life of the project and no systematic cost-benefit

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

analysis of long-term country representatives versus aseries ofshort-term consultants has been conducted. Projects and those who fund them clearly must consider thetrade-offs.

Early in the project, country representatives werehired locally and received few of the benefits contained intheAI.D. Handbook for Contractors. Roughly, the average annual cost for a single country representative on atwo-year contract was less than $50,000 during the firstphase of the project. Today country representatives havea diversity of technical backgrounds (including physicians) and receive the standard benefits package allowedby A.I.D. Exact figures were not available, but someA.I.D. projects budget $200,000 to $275,000 a year tocover a family of four at the high end of the salary scale.

In addition, any consideration of the cost of a resident technical advisor must factor in the expense of thesupport network that so enhances hislher work. Theproject paid an average of $370,000 a year over a sevenyear period for staff salaries and benefits of the SahelRegional Office ($600,000 in a year when full benefitswere in effect), an office that supports five to six countries (four with country representatives). Nevertheless,the existence of technical support in the region allows forless costly and more timely consultancies to the individual programs. (An average one-month consultancy fromthe United States costs $15-20,000, allowing for perdiem, travel, salary, and other expenses.)

On top of the substantial cost to the project of a resident representative, the full benefits package presents thecompany managing the project with an administrativeburden, requiring yet more support staff to oversee itsproper implementation. The growing diversity of overseas staff adds another layer of complexity. Box 2 showsthe number of administrative details that must beaddressed prior to placing a staff member in the field.

Do the significant advantages of full-time countryrepresentatives outweigh the heavy financial cost andmanagement burden of maintaining and supportingthem in the field? The benefits package is the same appliedto all US government employees or US contractors overseas; salary and benefits packages for private voluntaryorganizations, corporations, and international organizations differ almost on a par with their diverse philosophies and fiscal situations. Originally developed to luretechnical experts overseas and to compensate them for

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 29

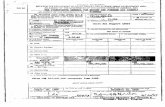

Box2. Employment checklist

10Name CouDtry

UJl.c:wz. 'J1Ibd ClIlUI&IJ CoqIIntIDgCllIUIdrJor..sdla& DatJaaal DallaaalAD....,..

Job .....IICbi Y Y YJobsmtiJIg y y yRNllme y y yA.LD. toDD 1420 Y Y YRafelmllldid(1IDI1 CIDdldate CIDIJ) Y Y YA.LD. pmJlCt ame.r IppravaJa:

Jobdl.;.~ y Y YIIUnltlw traval Y yt ytarK, tam. aDd DIgOtlatkms Y Y YT"~ Y Y YOdmtauaa traftl y yt yt

A.LD. amtrac:tiDg amCi IppronIa:IDmalaJur y Y YFldenlllWdlDum l ·1117watnr Y Y Y

TeDDl at IaigDIDeDt Ippmed Y y Y ~,

IIeDe1lt8 pIaD eDrl:lllmeat Y Y YDINc\ depoIIIt IUtborlzatlaD Y ya yaAmmll pelfonDlDl» ClbjllCttv. Y Y YPJogram UalDlDg Y Y Y

0......""""'"A.LD.~ ame.r IppravaJa:

TrIVIIID aDd froID pelt Y Y YBduCllUaDal travel:

TQ aDd froID us IdIool y Y N/ATQ aDd froID IIdIool outaldlt us y y N/A

RUtrlVll y y N/AHome1M.travel Y Y N/A

UD. CDIItraetlDgamCi IpprovU:Saluy1Dcr...r y y yHIred outaIde US Y Y YSblppIDg trom outIIde US Y Y YStorage OUUIde US Y Y Y8111pDcttlpa:allnltit1taDaJIIidIUS Y y y8111pDcttl~nltit1taDQ1lIIdeUS y y y110m tbID 2 WHU orieDtItJDD or tralDlDg Y Y Y

USAID IDIaIaD ClClIICUmDCM:Pemoa Y Y YIDmalaJur N y4 y4PIJIDIDt In US doUm N Y YTrIVIIID poal' y y yNumber ctwolt mumper"'__Number ctwolt ell,.per"'__Are IppllaDcea pmvtdltd?Colt ct UvIDg quutersLilt ct recognized boUd.,.III -=tIOOl bcXId mquirld?AJIowIDcM:

Pole dlfrerenUal N Y N/APole N y N/ASlJppleIMbtIl paR N y N/ATemporIrJ IodgIDg N y N/A

30 THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

AppIlaDce 8DowIDceUviIlg qIWtEs H y NlAEdncadoD H y NlAEdncadoDaJ travel:

To III1d flam US ICbool H Y N/ATo III1d flam scbool outside US Y Y N/A

lWltmve1 H Y N/AHomeJeave H Y N/ASeparate mabtteneDce N y N/ADaDgerpay H y yAa:ess to US Embassy b8a1th room H Y N/A

Medlcal uamlnatlonsPrlHnlgmnent

Employee Y Y YDependent(s) y Y N

Post-uslgnmentEmployee y H NDependent(s) y H N

ImmuDizRtinns~

Employee y y y~s) Y Y N

Depmment of State medlcal c:le8mDces:Employee y y NDependent(s) Y Y N

Medlcal records:Employee y yl ylDependllDt(s) Y yl yl

DefflD8ltoBased AsslstaDce 1DsurBDce:Employee y yts y6Dependent(s) Y y2 y2

Medev8c 1DsurBDce:Employee y y ylDependent(s) y Y yl

PemoDal vehIcJe iDsuraDce:Employee y y yDependent(s) Y Y Y

TowlBt or buliDess visas:Employee y y NDependent(s) Y Y N

ResideDt visas:Employee y y NDependent(s) Y Y N

BlIDk IICCOUDts:usbllDk' y y NLocalbank' y y N

Emergency locator IDformatioD:lmpIoyeel y Y YDependent(s) Y Y Y

IDd1vIduallDfonnatlon:Date anivtng at postNumber of pounds In storaqeNumber of pounds to be shipped:

SurfaceAir

Notel:1. If traveIlng to lIIIOther country under A.lD. funds.2. Ifpaid tbrough US b8nJL3. If more than 10 percent or If after less than ODe year.4. Ccmcur tbat amount Is not In ezcess of feder8l compensation or preval1lDQ waqe.6. UDIea (8) person Is pe1d In Joc::al cuuency, (b) b1aDket waiver Is In effect, and (e) Joc::al workers'

CllJIII)8IIDtion poUcy Is obtained.8. For lIe1d representative only.

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM 31

32

dangerous or hardship living situations, distance fromhome and family, higher cost of living, and so forth,some parts of the package may no longer be relevant ornecessary in the 1990s to attract appropriate personnel.

To change the remuneration system for one projectwould achieve little and hurt that project. If the argument is accepted that the country representative mechanism can significantly enhance program success andshould be replicated, then in the face of shrinking aidfunding it will be incumbent on donors and contractorsto review and revise the system across the board.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Long-term technical advisors (country representatives) can be an important component of successfuldevelopment assistance and should be budgeted intomajor project proposals similar to the PRITECH Project.

A.I.D. should consider convening representatives ofgroups working in development overseas to study inearnest and propose a revised standard benefits packagethat better reflects circumstances today (availability ofpersonnel, Iiving conditions and requirements, ease oftravel, and so forth).

A revised package should place less strain on overallproject funds and allow for the widespread use of country representatives in future projects.

A project should have written criteria for determining eligibility for each part of the benefit package.

These standards should reflect the overall development philosophy of the funding organizations and thediverse make-up ofcurrent technical staff. Job applicantsshould be informed of the criteria before being hired.

THE COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVE MECHANISM

THE CO:MPLEXITY OF HEALTH COMMUNICATIONS

~municators used to think that communica

tion was a one-way street, deserted but for them.. was the buDet theory of communication,

w en communicators were confident that if the messagewent out (whether spokm or written or broadcast), theaudiCllCe would hear the message, understand it, and adupon it. When oral rehydration salts were being introduced into the developing world in the carly 1980s, therewas still a good deal of this innocent confidcncc-that themiraculous effects oforal rehydration saltswould instantly convince people to seck it out and usc it for every caseof diarrhea. This is a simplification, but only a slight one.

But an innovation is rarely played out on a blank.slate. Rather, an innovation usually involves the introduction of a new produd or technology into a well-trodmarketplace. Just because oral rehydration was new didnot mean that people had not been dealing with diarrheabefore. Indeed, there existed well-cntrcnched diarrheathcrapics-both traditional and Westcrn-that peoplewere already using, for reasons that made sense to them.

Thus, people do not do things without reason. Whilehealth messages try to get people to change their behavior, people already have good reasons for doing whatthey are doing. To get them to change, we need to givethem better reasons. We need to make change rewarding, remembering that the status quo is already rewarding to some degree.

The following papers show that the communicationprocess is a marvdously VIbrant affair. PRITECH's experience in health communications has extended acrossmany countries, addressed many audiences, and usedmany methods. The papers in this section demonstratethe importance of the following dements in a healthcommunication intervention.

USE OF ALTERNATIVE CHANNELS

Most national programs for the control of diarrhealdisease have relied on traditional information and communication channels of the ministry of health system to distribute their educational materials. As the Cameroon andSahd papers show, however, public health workers arc notusing or distributing materials to the best advantage.

THE COMPLEXITY OF HEALTH COMMUNICATIONS

Previous Paqe DIal tl,.

35

36

In addition, many people do not usc governmenthealth centers. In response to these problems, PRITECHfound alternative ways to distribute educational matcriaIsto mothers. These channels included the usc ofvillagemarkets in ruraI Mexico, usc of popular theater in peri-urbanareas in Zambia, and the use of nongovernmental groupsto distribute health education materials in Cameroon.

PARTICIPATION

Not only is participatory learning a good theoreticalapproach, people like it. People like to have their own cultural forms used, like the Zambian popular theater or theMexican lottery games, and people like to choose from aselection of information that they can use, as they dofrom information products offered by the PRITECH andORANA information centers. People also like to be listened to and be taken seriously, a fact that must be considered in any successful implementation effort.

TARGETING SPECIFIC AUDIENCES

Addressing health education interventions to smaller,homogeneous groups is often more manageable and moresuccessful. The messages and materials can be developedto suit the needs of a target group. And communities athigher risk of diarrheal disease can be reached directly, tohelp encourage better care among families that are mostlikely to experience the illness. For example, the Ciclopegroup worked in rural Mexican villages where many parents do not have access to health care services. And thepopular theater groups of zambia traveled through periurban areas, which other health programs had neglected.

REsEARCH AND MONITORING

listening is a basic communication skill, and in thepublic health communication setting, listening is done in asystematic way, called research. Research is simply systematic listening, and is the first step in the communicationprocess. The studies from the Sahel and Cameroon demonstrate the value of and need for research and evaluation.

The days of one-way communication streets probably never really existed. Today's effective communicatorknows that the work is more interesting than that, andleads to so many more opportunities.

THE COMPLEXITY OF HEALTH COMMUNICATIONS

THE ClCLOPE INNOVATIONSIN RURAL COMMUNICATION:REACHING THE UNREACHABLE VILLAGES IN MEXICO

Nobody knows how many small villages there are inMexico, but there are tens of thousands of hamlets withfewer than SOO inhabitants scattered throughout thecountry. For the national health secretary, trying to provide health services broadly and equitably, these manytiny settlements offer unique challenges. People in vill!\ges are at particularly high risk for disease, due to theirisolation, their lack of education, their limited diets, theirlack of access to services, and often their lack of Spanishfluency. And for women, who care for children whenthey are sick, all these disadvantages are compounded bygender. The health secretary, responsible for the world'slargest city as well as thouSands of small towns, has toseek creative solutions to the needs of th~e numerousbut far-flung rural peoples.

In January 1990, the Mexican health secretary askedPRITECH to help him to do just that. PRITECH had beenworking with the national diarrheal disease control program for several years by then, training Ministry ofHealth staff, in a cascade design intended to reach out torural areas. However, all the constraints that make ruralpeople high-risk in the first place had been conspiring todilute training efforts as information diffused from themain towns. To reach beyond these constraints,PRITECH had to come up with a fresh strategy, a truerural communication strategy.

PRITECH enlisted a local consulting group, the Ciclope group. Ciclope had done research with rural indigenous people, specifically in terms of their diarrheal treatment practices, and had developed training strategies towork with them. With a unique track record in medicaland anthropological research among indigenous people,Ciclope enjoyed entree to those communities.

COllsll<lll1ls to ORT Proll1otIon in Rlirdl Ar('ilS

For this first effort, Ciclope focused on two states,Hidalgo and Veracruz, for eight months through December 1991. The infant mortality rate due to diarrhealdehydration remains high in both Hidalgo and Veracruz.In Hidalgo, for 1984, the rate was 647 cases per 100,000

THE CICLOPE INNOVATIONS IN RURAL COMMUNICATION

Sdmc Alvarez L. isdirector of the CiclopcGroup, and Pder L.Spain was a PRITECHSenior Program 0ffi-cer.

37

38

childrm under age one and 689 cases per 100,000 children ages one to five years old.1 For Veracruz, in 1987,the rate of deaths due to diarrhea was 340 deaths per100,000 children under age one and 49 deaths per100,000 children ages one to five.1

In both states, these deaths occur mainly among therural population. Peasants and indigenous peoples of themost distant and scattered communities are the groupsthat contribute most to these infant-mortality rates. Inan analysis of infant and preschool mortality done on the1980 population census, Ciclope had earlier determinedwhich municipalities had the highest infant and childmortality rates in Hidalgo and Veracruz. Moreover, inHidalgo, death records were studied in the civil registriesof a sample of those municipalities identified by the Ciclope analysis of the 1980 census. Records that mentioneddehydration as a primary cause of death for childrenunder five were cross-tabulated with the communitieswhere those deaths occurred. What Ciclope had foundwas this: the number of deaths from dehydrationincreased in direct relation with the distance of the communities from the municipal center (county seat) wherethe civil registries are located.3

Ciclope conducted the same analysis for Veracruz.There, Ciclope found that the majority of the deaths werein areas where seasonal agriculture is practiced, areaswhere there is mainly an indigenous population.· ForVeracruz, however, the health secretariat had determinedthat the areas just outside the principal cities were theareas of greatest diarrheal incidence.'

Most of these deaths are preventable with oral rehydration therapy (ORT). But, in these regions, ORT promotion is hindered by lack of pcrsonnd, lack of access,lack of health-system infrastructure, and the low educationallevd of this population.' Another important consideration for ORT promotion in Hidalgo and Veracruz isthat ORT use is very low in both states, according to anational study done by the federal health secretariat. InHidalgo, 14 percent of diarrhea cases were treated withORT, while in Veracruz the figure was 4 percenU